Abstract

Background:

Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension are a pressing public health problem. The contribution of environmental pollutants including PFAS have not been explored, even though certain PFAS are higher in Black population and have been associated with hypertension.

Objectives:

We examined the extent to which racial/ethnic disparities in incident hypertension are explained by racial/ethnic differences in serum PFAS concentrations.

Methods:

We included 1,058 hypertension-free midlife women with serum PFAS concentrations in 1999–2000 from the multi-racial/ethnic Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation with approximately annual follow-up visits through 2017. Causal mediation analysis was conducted using accelerated failure time models. Quantile-based g-computation was used to evaluate the joint effects of PFAS mixtures.

Results:

During 11,722 person-years of follow-up, 470 participants developed incident hypertension (40.1 cases per 1000 person-years). Black participants had higher risks of developing hypertension (relative survival: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.45–0.76) compared with White participants, which suggests racial/ethnic disparities in the timing of hypertension onset. The percent of this difference in timing that was mediated by PFAS was 8.2% (95% CI: 0.7–15.3) for PFOS, 6.9% (95% CI: 0.2–13.8) for EtFOSAA, 12.7% (95% CI: 1.4–22.6) for MeFOSAA, and 19.1% (95% CI: 4.2, 29.0) for PFAS mixtures. The percentage of the disparities in hypertension between Black versus White women that could have been eliminated if everyone’s PFAS concentrations were dropped to the 10th percentiles observed in this population was 10.2% (95% CI: 0.9–18.6) for PFOS, 7.5% (95% CI: 0.2–14.9) for EtFOSAA, and 17.5% (95% CI: 2.1–29.8) for MeFOSAA.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest differences in PFAS exposure may be an unrecognized modifiable risk factor that partially accounts for racial/ethnic disparities in timing of hypertension onset among midlife women. The study calls for public policies aimed at reducing PFAS exposures that could contribute to reductions in racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension.

Keywords: Racial/ethnic disparities, Hypertension, Midlife women, Mediation analysis, Environmental health disparities

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is an epidemic in the United States that disproportionately affects specific population groups (Menke et al., 2015; Mills et al., 2016): The prevalence of hypertension in the Black population is among the highest in the U.S., with a prevalence of 42% of Black males and 46% of Black females aged 20 years and older, as compared with Whites (31% for males and 30% for females), Asians (29% for males and 27% for females) and Hispanics (27% for males and 32% for females) (Whelton et al., 2018). Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension are associated with poorer hypertension control (Al Kibria, 2019; Whelton et al., 2018), greater severity of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Cheng et al., 2014), higher rates of hospitalizations and greater medical expenditures (Zhang et al., 2017). Causes of racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence are multifactorial, with socioeconomic factors such as reduced insurance coverage and less access to healthcare being primary determinants of risk (Gu et al., 2017). While causal determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension have been well studied, exposure to environmental pollutants, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), have been underexamined. Assessment of the role of PFAS in hypertension risk is important, as exposure to such pollutants are potentially modifiable risk factors for hypertension.

PFAS are a family of more than 4,000 synthetic chemicals that are often known as “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down in the environment (ATSDR, 2021). More than 200 million people in the United States are exposed to PFAS through contaminated drinking water (Andrews and Naidenko, 2020), which has been linked to industrial sites, military fire training areas and wastewater treatment plants (Hu et al. 2016). Other important sources of PFAS exposure including diet and indoor environments. Due to the near ubiquitous exposure, nearly all Americans have detectable concentrations of PFAS in their blood (CDC, 2021). A few studies have demonstrated associations between higher PFAS and blood pressure elevation and the development of hypertension (Bao et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2020; Min et al., 2012; Pitter et al., 2020). Several studies have documented racial/ethnic differences in PFAS exposure levels. Specifically, studies of midlife women find that Black women have higher exposures to certain PFAS compared to other racial/ethnic groups (Boronow et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2020; Kato et al., 2015, 2011b; Park et al., 2019b). While drivers of racial/ethnic differences in PFAS exposure have not been well examined, differences could be due to residential racial segregation since living in areas served by PFAS-contaminated water supply is associated with higher serum levels of some PFAS (Boronow et al., 2019). Given the elevated levels of certain PFAS compounds in Black communities observed in some studies as well as the importance of PFAS in hypertension, it is important to explore the potential mediating role of PFAS exposure in explaining racial disparities in hypertension.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate the mediating role of individual PFAS in the causal pathways from race/ethnicity to hypertension using data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a well-characterized, multi-site, multi-racial/ethnic cohort of midlife women. Racial/ethnic difference in the prevalence, incidence and timing of hypertension have been documented in SWAN (Harlow et al., 2022; Kelley-Hedgepeth et al., 2008) as have racial/ethnic differences in PFAS exposures (Ding et al., 2020; Park et al., 2019b). Notably, Black women in SWAN, on average, have around 5 years earlier onset of hypertension than White women (Reeves et al., 2022). Prior research also suggests the assessment of environmental mixtures in a mediation model by reducing the mixtures to a single mediator (Bellavia et al., 2019; Rana et al., 2021). Thus, we also conducted a secondary analysis to evaluate the mediating role of PFAS mixtures.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study population

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) recruited participants aged 42 to 52 years from 1996 to 1997 in seven sites across the United States (Santoro et al., 2011). Eligibility criteria included presence of an intact uterus who were not pregnant and had had at least one menstrual period and were not taking hormone medications within the prior three months. Race/ethnicity was based on participant self-identification. Investigators recruited Black women from Boston, MA, Chicago, IL, Pittsburgh, PA, and southeast MI, Hispanic women from Newark, NJ, Chinese women from Oakland, CA, and Japanese women from Los Angeles, CA and White women at all seven sites. The SWAN Multi-Pollutant Study (SWAN MPS) enrolled a subsample of 1,400 participants using repository biospecimens-collected at the SWAN visit 03 (the SWAN MPS baseline, 1999–2000) to assess multiple environmental pollutants in White, Black, Chinese, and Japanese women (Ding et al., 2020; Park et al., 2019a; Wang et al., 2019a). Hispanic women were not included due to a lack of biological samples at the Newark site. Of the 1,400 SWAN MPS participants with available PFAS measurements, the current analysis excluded women with missing information on hypertension (n=18), those who had prevalent hypertension (n=306) at the SWAN MPS baseline, and those with missing values for other covariates (n=18), yielding a final analytic sample of 1,058 women followed from 1999 to 2017.

The research protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at each of the collaborating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at each visit.

Serum PFAS measurement

Serum samples were analyzed at the Division of Laboratory Sciences, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The analytic methods used to estimate serum PFAS concentrations has been described previously (Kato et al., 2011a). In brief, an online solid phase extraction-high performance liquid chromatography-isotope dilution-tandem mass spectrometry were developed for quantification of perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), linear perfluorooctane sulfonate (n-PFOS), sum of branched isomers of PFOS (Sm-PFOS), linear perfluorooctanoate (n-PFOA), sum of branched PFOA (Sb-PFOA), perfluorononanoate (PFNA), perfluorodecanoate (PFDA), perfluoroundecanoate (PFUnDA), perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDoDA), and 2-(N-ethyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetate (EtFOSAA), and 2-(N-methyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetate (MeFOSAA) in 0.1 mL of serum. The coefficient of variation of low- and high-quality controls ranged from 6% to 12%, depending on the analyte. The limit of detection (LOD) was 0.1 ng/mL for all the analytes. Detection frequencies, medians (interquartile ranges, IQR), geometric means (geometric standard deviation), and ranges are listed in Table S1. Sb-PFOA (%>LOD: 17.1%), PFDA (%>LOD: 41.3%), PFUnDA (%>LOD: 32.9%), and PFDoDA (%>LOD: 3.7%) were not included in statistical analyses due to low detection frequencies. N-PFOS, Sm-PFOS, n-PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA, EtFOSAA and MeFOSAA were detected in >97% serum samples and thus were included in further analyses. Concentrations below the LODs were substituted with (Hornung and Reed, 1990). Total PFOS (PFOS) was computed as the sum of n-PFOS and Sm-PFOS.

Hypertension ascertainment

A standard mercury sphygmomanometer was used to record systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at the approximately annual visits . Blood pressure was measured according to a standardized protocol, with readings taken on the right arm after 5 min in the seated position. Three readings were taken with a minimum two-minute rest period between measures. The average of two sequential blood pressure values was employed in these analyses. Hypertension was defined as SBP≥140 mmHg or DBP≥90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications, in accordance with the definitions used in the sixth and seventh reports of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Treatment and Control of High Blood Pressure (JNC-6, JNC-7) (Carey et al., 1985; Chobanian et al., 2003).

Covariates

Given careful review of the literature for important variables associated with both PFOS exposure and hypertension risk (Ding et al., 2022; Park et al., 2019b; Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2000), we selected a comprehensive set of confounders. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics assessed at baseline included age (in years), self-defined race (Black, Chinese, Japanese, White), study site (Southeast Michigan, Boston, Pittsburgh, Oakland, Los Angeles), education (high school or less, some college, college degree or higher), and difficulty paying for basics (very hard, somewhat hard, not hard at all). Lifestyle risk factors collected at the MPS baseline included cigarette smoking (current, former, or never) (Ferris, 1978), secondhand smoking (0, 1–4, ≥5 person-hours) (Coghlin et al., 1989), total calorie intake (in kcal) (Block et al., 1986), alcohol intake (<1 drink/month, >1 drink/month, and ≤1/week, >1 drink/week) (Block et al., 1986), and body mass index (BMI). BMI (kg/m2) was calculated using measured height and weight. Physical activity was assessed in various domains, including sports/exercise, household/caregiving, and daily routine, with a score ranging from 3 to 15 (15 indicating the highest level of activity) (Sternfeld et al., 1999). Menopausal status was categorized into surgical postmenopause, natural postmenopause, late perimenopause, early perimenopause, premenopause, or unknown due to hormone therapy (HT) using bleeding patterns and information about HT use (Sowers et al., 2007).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine participant characteristics at the MPS baseline in the total population and by racial/ethnic groups. Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were implemented to compare differences in race/ethnicity for categorical variables; analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous variables. Serum concentrations of PFAS were log-transformed with base 2 to ensure normality.

The principal interest of the study was to assess the extent to which PFAS could account for racial/ethnic disparities in incident hypertension. The conceptual model is shown in Figure S1. Causal mediation analysis was conducted to examine the mediating role of PFAS on racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension. These associations were estimated using accelerated failure time (AFT) models with a Weibull distribution (Gelfand et al., 2016; VanderWeele, 2011). The Weibull distribution was selected by comparing Akaike information criterion (AIC) values. The outcome AFT model initially took the following general form:

Where T is time to hypertension, Race represents racial/ethnic groups (including Black or Asian participants compared with White participants), PFAS represents log2-transformed serum concentrations of PFAS, Race × PFAS is the interaction term between race/ethnicity and log2-transformed serum concentrations of PFAS Covariate, are baseline confounders, σ describes the Weibull distribution scale and shape parameters, and ε symbolizes the errors which are independently and identically distributed.

The racial/ethnic disparity was calculated and expressed as relative survival and interpreted as a ratio of time to develop hypertension comparing Black or Asian participants to White. If the relative survival equals to 1, then there is a null association between race/ethnicity and incident hypertension; if the relative survival is less than 1, Black or Asian race/ethnicity compared with White is associated with shorter time to the development of hypertension; and if the relative survival is greater than 1, Black or Asian race/ethnicity is associated with the longer time to the development of hypertension. We then fit a linear regression model for the mediator, log2-transformed PFAS concentrations

Direct effects are equal to (VanderWeele and Robinson, 2014),

and mediated effects equal to (VanderWeele and Robinson, 2014),

Assuming G(0) is a random draw of PFAS concentrations in the White population and G(1) is a random draw of PFAS concentrations in the Black population, Race = 1 represents the Black population and Race = 0 stands for the White population. Similar formula can be derived for the Asian population. The direct effects obtained for race/ethnicity not through PFAS can be interpreted as the disparity in incident hypertension that would remain for participants if the PFAS distributions of the Black population were set equal to those of the White population, assuming we have controlled for sufficient variables such that the associations between PFAS and hypertension actually reflects the effects of PFAS on hypertension. The mediated effects can be interpreted as how much of racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension is due to racial/ethnic differences in serum PFAS concentrations. Note that the assumptions required here for identification are much weaker than those for natural direct and natural indirect effects because it is nearly impossible to capture the effects of physical phenotype, parental physical phenotype, genetic background, and culture context, all of which are associated with race/ethnicity (VanderWeele and Robinson, 2014).

Given the presence of exposure-mediator interactions, we also calculated the controlled direct effects and the percentage of the racial/ethnic disparities in incident hypertension that could potentially be eliminated by intervening to set PFAS concentrations to the 10th percentiles of exposure in the SWAN MPS study population (Valeri and VanderWeele, 2013; Vanderweele, 2013). The controlled direct effects are disparity in incident hypertension that would remain for participants if the PFAS concentrations are fixed to a specific level, in this case, the 10th percentiles in the study population. The percentage eliminated is a more policy-relevant measure, which captures the extent to which racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension could be eliminated by intervening on serum PFAS concentrations.

To evaluate the overall mediating effects of PFAS mixtures on incident hypertension, we constructed an integrative index health risk of exposure to multiple chemicals in epidemiological research (Park et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019b, 2018). The underlying idea behind the index is to build a risk score as a weighted sum of the chemical concentrations from the simultaneous assessment of multiple chemicals. Weights are determined by the magnitudes of the associations between chemicals and health outcomes of interest from the same regression model. To achieve this goal, we first used quantile g-computation to evaluate the associations between multipollutant PFAS and incident hypertension (Keil et al., 2020). Weights represented the association between each PFAS and incident hypertension per one quantile increase in PFAS concentrations. Quantile g-computation was implemented using the “qgcomp” package in R statistical computing environment. An index was then computed as a weighted sum of all seven PFAS by , where (j = 1, …, P) is the log-transformed concentrations of the jth PFAS for the ith subject; is the beta coefficients for the jth selected PFAS. As a final step, direct and mediated effects were estimated under the framework of causal mediation analysis, similar to individual PFAS. We also considered interactions between race/ethnicity and the index and calculated the racial/ethnic disparities in the development of hypertension that could be eliminated by fixing all PFAS concentrations simultaneously their 10th percentiles in our study population

Sensitivity analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to confirm the robustness of our findings. PFAS are artificial chemicals believed to contribute to obesity (Ding et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2018), thus, we additionally adjusted for BMI at the MPS baseline to exclude the possibility of confounding. Second, we evaluated percent mediated risk assuming no exposure-mediator interactions to assess the additional impact of those interactions. Finally, in addition to standard approaches for causal mediation analysis, we also considered more general approaches in health disparity research i.e., counterfactual disparity measures, or the disparity that would remain in the Black or Asian population assuming the same distribution of PFAS concentrations as the White population (Naimi et al., 2016). We calculated the percent of reduction in racial/ethnic disparities in the development of hypertension when setting the same distributions of PFAS across racial/ethnic groups. This method assumes no exposure-mediator interaction and thus interaction between race/ethnicity and PFAS were not included in the analysis. The definition of hypertension was based on SBP≥140 mmHg or DBP≥90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications, in accordance with the widely accepted definitions used in the seventh report of the JNC-7. We have also conducted sensitivity analysis using guideline per ACC/AHA 2017 recommendations (Whelton et al., 2018), i.e., stage 1 hypertension defined as blood pressure at or above 130/80 mmHg and stage 2 hypertension as blood pressure 140/90 mmHg.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows the median (IQR) or frequency of participant characteristics and each mediator in the total population and by racial/ethnic group. The study sample included 577 (54.6%) White, 161 (15.2%) Black, and 320 (30.2%) Asian. The median age of participants was 49.2 years at the MPS baseline (1999–2000). The median follow-up was 5.9 years for 470 participants with incident hypertension, and 16.2 years for 588 participants without hypertension cases. The majority of the study population had college education or higher (53.3%), did not have difficulty paying for basics (70.2%), were never smokers (64.4%), were not exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (62.2%), did not drink alcohol (50.8%), and were pre- or early perimenopausal (72.2%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and blood pressure in midlife women in the total population and by race/ethnicity from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Multi-Pollutant Study (n=1,058).

| Total (n=1,058) |

By racial/ethnic groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n=577) |

Black (n=161) |

Asian (n=320) |

|||

| Characteristics | Median (IQR) or N (%) | Median (IQR) or N (%) | Median (IQR) or N (%) | Median (IQR) or N (%) | P valuea |

| Age, year | 49.2 (47.2, 51.3) | 48.9 (47.1, 51.3) | 48.7 (47.0, 50.8) | 49.7 (47.5, 51.4) | 0.02 |

| Education | <0.0001 | ||||

| ≤High school | 177 (16.7%) | 60 (10.4%) | 51 (32.1%) | 66 (20.6%) | |

| High school | 317 (30.0%) | 168 (29.2%) | 58 (36.5%) | 91 (28.4%) | |

| College | 273 (25.8%) | 146 (25.4%) | 27 (17.0%) | 100 (31.3%) | |

| Post-college | 291 (27.5%) | 205 (35.0%) | 23 (14.4%) | 63 (19.7%) | |

| Difficulty paying for basics | <0.0001 | ||||

| Very hard | 58 (5.5%) | 22 (3.8%) | 24 (15.2%) | 12 (3.8%) | |

| Somewhat hard | 257 (24.3%) | 136 (23.7%) | 50 (31.7%) | 71 (22.2%) | |

| Not hard at all | 753 (70.2%) | 417 (72.5%) | 84 (53.1%) | 237 (74.0%) | |

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Never smoked | 681 (64.4 %) | 335 (58.1%) | 94 (58.4%) | 252 (78.8%) | |

| Past smoker | 278 (26.3%) | 190 (32.9%) | 39 (24.2%) | 49 (15.3%) | |

| Current smoker | 99 (9.4%) | 52 (9.0%) | 28 (17.4%) | 19 (5.9%) | |

| Environmental tobacco smoke | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0 person-hrs | 658 (62.2%) | 351 (60.8%) | 68 (42.2%) | 239 (74.7%) | |

| 1–4 person-hrs | 238 (22.5%) | 146 (25.3%) | 39 (24.2%) | 53 (16.6%) | |

| ≥5 person-hrs | 162 (15.3%) | 80 (13.9%) | 54 (33.6%) | 28 (8.7%) | |

| Alcohol intake | <0.0001 | ||||

| None/Low use | 538 (50.8%) | 215 (37.3%) | 106 (65.8%) | 217 (67.8%) | |

| Moderate use | 257 (24.3%) | 169 (29.3%) | 32 (19.9%) | 56 (17.5%) | |

| High use | 263 (24.9%) | 193 (33.4%) | 23 (14.3%) | 47 (14.7%) | |

| Physical activity score | 8.0 (6.7, 9.1) | 8.2 (7.0, 9.4) | 7.5 (6.5, 8.8) | 7.7 (6.6, 8.9) | <0.0001 |

| Menopausal status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Surgical postmenopause | 30 (2.8%) | 12 (2.1%) | 11 (6.8%) | 7 (2.2%) | |

| Natural postmenopause | 114 (10.8%) | 64 (11.1%) | 12 (7.5%) | 38 (11.9%) | |

| Late perimenopause | 78 (7.4%) | 36 (6.2%) | 15 (9.3%) | 27 (8.4%) | |

| Early perimenopause | 548 (51.8%) | 276 (47.8%) | 82 (50.9%) | 190 (59.4%) | |

| Premenopause | 138 (13.0%) | 84 (14.6%) | 20 (12.4%) | 34 (10.6%) | |

| Unknown with hormone therapy | 150 (14.2%) | 105 (18.2%) | 21 (13.0%) | 24 (7.5%) | |

| Total calorie intake, kcal | 1694 (1352, 2161) | 1667 (1336, 2071) | 1797 (1384, 2349) | 1739 (1383, 2200) | 0.06 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.1 (22.1, 29.9) | 25.8 (22.4, 30.7) | 30.7 (25.9, 34.4) | 22.7 (20.8, 25.0) | <0.0001 |

| PFAS concentrations, ng/mL | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | P valuea |

| PFOS | 24.1 (17.3, 34.8) | 24.2 (17.3, 35.6) | 31.9 (20.9, 48.6) | 21.8 (15.7, 29.0) | <0.0001 |

| n-PFOS | 17.2 (12.2, 24.1) | 16.6 (12.1, 24.0) | 22.7 (15.4, 34.8) | 15.9 (11.7, 21.0) | <0.0001 |

| Sm-PFOS | 7.1 (4.6, 10.7) | 7.6 (5.2, 11.6) | 8.2 (5.5, 13.5) | 5.5 (3.8, 8.2) | <0.0001 |

| n-PFOA | 4.1 (2.8, 5.9) | 4.5 (3.3, 6.1) | 4.2 (2.9, 6.4) | 3.2 (2.2, 4.5) | <0.0001 |

| PFHxS | 1.5 (1.0, 2.4) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.8) | 1.7 (1.1, 3.1) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) | <0.0001 |

| PFNA | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | <0.0001 |

| EtFOSAA | 1.2 (0.6, 2.2) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.2) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.5) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.6) | <0.0001 |

| MeFOSAA | 1.4 (0.9, 2.3) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.3) | 2.0 (1.3, 3.0) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | <0.0001 |

Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were conducted for categorical variables. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were conducted for continuous variables.

Participant characteristics differed significantly by racial/ethnic groups. Black participants were less likely to have a college education or higher (31.4%), compared with White (60.4%) and Asian (51.0%) (P<0.0001). Furthermore, Black participants were more likely to have difficulty paying for basics (P<0.0001), be current smokers (P<0.0001), be exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (P<0.0001) and have had a hysterectomy or oophorectomy (P<0.0001) than White and Asian women. Black and Asian participants tended to report no or low alcohol use (P<0.0001), and low intensity of physical activity (P<0.0001). Asian participants had the lowest BMI among racial/ethnic groups (P<0.0001).

Serum concentrations of PFOS, n-PFOS, Sm-PFOS, EtFOSAA and MeFOSAA were significantly higher among Black participants compared with other racial/ethnic groups (P<0.0001, Table 1). Serum concentrations of n-PFOA were higher among White participants, intermediate among Black, and lowest among Asian participants (P<0.0001). Asian women had lower concentrations of PFHxS compared to White and Black women (P<0.0001). Asian and Black participants had higher concentrations of PFNA than White participants (P<0.0001).

Mediating effects of individual PFAS

Table 2 shows the total effects, direct effects, and mediated effects of individual PFAS on racial/ethnic disparities in incident hypertension, after adjusting for age, study site, education, difficulty paying for basics, smoking status, environmental tobacco smoke, alcohol intake, menopausal status, physical activity, and total calorie intake at the MPS baseline. Black participants had significantly higher risks of developing hypertension (relative survival: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.45, 0.76) compared to White participants. The direct effects of Black versus White race/ethnicity on time to hypertension were significant in each PFAS model. The mediated effects through PFAS were significant for PFOS, n-PFOS, and two precursors (i.e., EtFOSAA and MeFOSAA). Specifically, the direct-effect of Black versus White race/ethnicity was 0.62 (95% CI: 0.47, 0.82) and the mediated-effect for PFOS was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.89, 1.00). From these data, 8.2% (95% CI: 0.7, 15.3) of the racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension would be explained if PFOS distributions in the Black and White populations were equivalent. Similarly, the percent mediated by n-PFOS was 10.0% (95% CI: 0.3, 17.8), EtFOSAA was 6.9% (95% CI: 0.2, 13.8) , and MeFOSAA was 12.7% (95% CI: 1.4, 22.6). By contrast, no significant mediation was observed for n-PFOA (percent mediated: −3.2%, 95% CI: −10.0, 2.6), PFNA (percent mediated: 2.0%, 95% CI: −3.2, 6.5), or PFHxS (percent mediated: −0.3%, 95% CI: −3.3, 2.4).

Table 2.

Relative survival (95% confidence interval, 95% CI) in incident hypertension comparing Black women with White women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation.a

| Total effect | Direct effect | Mediated effect | Percent mediated | Controlled direct effectb | Percent eliminated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Relative survival (95% CI) | Relative survival (95% CI) | Relative survival (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | Relative survival (95% CI) | % (95% CI) |

| PFOS | 0.58 (0.45, 0.76) | 0.62 (0.47, 0.82) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.00) | 8.2 (0.7, 15.3) | 0.67 (0.46, 0.99) | 10.2 (0.9, 18.6) |

| n-PFOS | 0.58 (0.45, 0.77) | 0.63 (0.47, 0.83) | 0.93 (0.87, 1.00) | 10.0 (0.3, 17.8) | 0.69 (0.48. 1.00) | 12.7 (0.4, 22.1) |

| Sm-PFOS | 0.58 (0.45, 0.77) | 0.61 (0.46, 0.79) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.01) | 4.8 (−2.2, 10.7) | 0.67 (0.46, 0.97) | 6.3 (0.3, 13.6) |

| n-PFOA | 0.58 (0.45, 0.76) | 0.59 (0.45, 0.76) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | −3.2 (−10.0, 2.6) | 0.69 (0.47, 1.01) | −5.0 (−16.5, 4.0) |

| PFNA | 0.59 (0.45, 0.78) | 0.60 (0.46, 0.78) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 2.0 (−3.2, 6.5) | 0.69 (0.48, 1.00) | 2.9 (−4.9, 9.5) |

| PFHxS | 0.59 (0.45, 0.76) | 0.59 (0.45, 0.76) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | −0.3 (−3.3, 2.4) | 0.63 (0.44, 0.91) | −0.4 (−4.0, 2.9) |

| EtFOSAA | 0.58 (0.45, 0.76) | 0.61 (0.47, 0.80) | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | 6.9 (0.2, 13.8) | 0.63 (0.44, 0.92) | 7.5 (0.2, 14.9) |

| MeFOSAA | 0.58 (0.45, 0.76) | 0.64 (0.48, 0.86) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) | 12.7 (1.4, 22.6) | 0.73 (0.47, 1.12) | 17.5 (2.1, 29.8) |

Models were adjusted for age, study site, education, difficulty paying for basics, smoking status, environmental tobacco smoke, alcohol intake, menopausal status, physical activity, and total calorie intake at the MPS baseline.

Controlled direct effect assesses the effect of race/ethnicity on incident hypertension with PFAS concentrations fixed to the 10th percentiles, which is 12.6 ng/mL for PFOS, 8.9 ng/mL for n-PFOS, 3.2 ng/mL for Sm-PFOS, 2.0 for n-PFOA, 0.3 ng/mL for PFNA, 0.6 ng/mL for PFHxS, 0.4 ng/mL for EtFOSAA, and 0.6 ng/mL for MeFOSAA.

Given the significant interactions between race/ethnicity and PFAS on time to hypertension, we ran models fixing each PFAS at the concentration at the 10th percentile of exposure. In these models the controlled direct effects represent the racial/ethnic disparities in time to hypertension that would remain in the SWAN MPS study population. In these models, the percent of racial/ethnic disparities eliminated was significant for PFOS (10.2%, 95% CI: 0.9, 18.6), n-PFOS (12.7%, 95% CI: 0.4, 22.1), Sm-PFOS (6.3%, 95% CI: 0.3, 13.6), EtFOSAA (7.5%, 95% CI: 0.2, 14.9), and MeFOSAA (17.5%, 95% CI: 2.1, 29.8).

The total effects, direct effects, and mediated effects of racial/ethnicity on time to hypertension comparing Asian with White participants are displayed in Table 3. Asian participants did not have higher risks of earlier onset of hypertension, with the relative survival of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.63, 1.11) and in the mediation analysis neither the direct nor the mediated effects were significant.

Table 3.

Relative survival (95% confidence interval, 95% CI) in incident hypertension comparing Asian women with White women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation.a

| Total effect | Direct effect | Mediated effect | Percent mediated | Controlled direct effectb | Percent eliminated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Relative survival (95% CI) | Relative survival (95% CI) | Relative survival (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | Relative survival (95% CI) | % (95% CI) |

| PFOS | 0.84 (0.63, 1.11) | 0.81 (0.61,1.07) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | −15.9 (−58.7, 7.7) | 0.84 (0.58, 1.20) | −19.6 (−40.2, 9.1) |

| n-PFOS | 0.84 (0.63, 1.11) | 0.83 (0.63, 1.09) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | −5.6 (−24.8, 8.1) | 0.86 (0.60, 1.25) | −7.5 (−35.4, 10.4) |

| Sm-PFOS | 0.84 (0.63, 1.10) | 0.79 (0.60, 1.05) | 1.05 (0.95, 1.16) | −25.2 (−161.5, 14.9) | 0.78 (0.54, 1.11) | −22.8 (−131.9, 13.9) |

| n-PFOA | 0.84 (0.63, 1.11) | 0.86 (0.64, 1.15) | 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) | 10.5 (−35.3, 52.9) | 0.71 (0.50, 1.00) | 4.5 (−16.4, 18.2) |

| PFNA | 0.84 (0.63, 1.11) | 0.85 (0.64, 1.12) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) | −4.5 (−258.4, 36.0) | 0.81 (0.57, 1.16) | −3.5 (−128.4, 30.5) |

| PFHxS | 0.85 (0.64, 1.13) | 0.87 (0.64, 1.18) | 0.98 (0.91, 1.05) | 12.3 (−38.1, 58.7) | 0.82 (0.59, 1.15) | 8.6 (−32.8, 8.6) |

| EtFOSAA | 0.84 (0.63, 1.11) | 0.80 (0.60, 1.06) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.10) | −10.4 (−61.8, 14.9) | 0.73 (0.51, 1.05) | −6.9 (−35.4, 10.7) |

| MeFOSAA | 0.84 (0.63, 1.11) | 0.82 (0.62, 1.08) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | −4.9 (−38.4, 14.7) | 0.73 (0.51, 1.05) | −3.0 (−20.4, 9.5) |

Models were adjusted for age, study site, education, difficulty paying for basics, smoking status, environmental tobacco smoke, alcohol intake, menopausal status, physical activity, and total calorie intake at the MPS baseline.

Controlled direct effect assesses the effect of race/ethnicity on incident hypertension with PFAS concentrations fixed to the 10th percentiles, which is 12.6 ng/mL for PFOS, 8.9 ng/mL for n-PFOS, 3.2 ng/mL for Sm-PFOS, 2.0 for n-PFOA, 0.3 ng/mL for PFNA, 0.6 ng/mL for PFHxS, 0.4 ng/mL for EtFOSAA, and 0.6 ng/mL for MeFOSAA.

Sensitivity analyses further adjusting for BMI at the MPS baseline did not change our study results (Tables S2–S3). Ignoring interactions between race/ethnicity and PFAS, yielded a lower but significant percent of mediation of 5.0% (95% CI: 0.2, 9.3) for PFOS, 5.7% (95% CI: 0.4, 10.1) for n-PFOS, 5.7% (95% CI: 0.1, 10.2) for EtFOSAA, and 6.0% (95% CI: 0.6, 11.1) for MeFOSAA for racial/ethnic differences in time to hypertension comparing Black versus White participants (Table S4), but not for Asian compared to White participants (Table S5). Results of the counterfactual models did not change the overall conclusions of this study (Tables S6–S7). Similar results were observed when defining hypertension as blood pressure at or greater than 130/80 mmHg (Table S8).

Mediating effects of PFAS mixtures

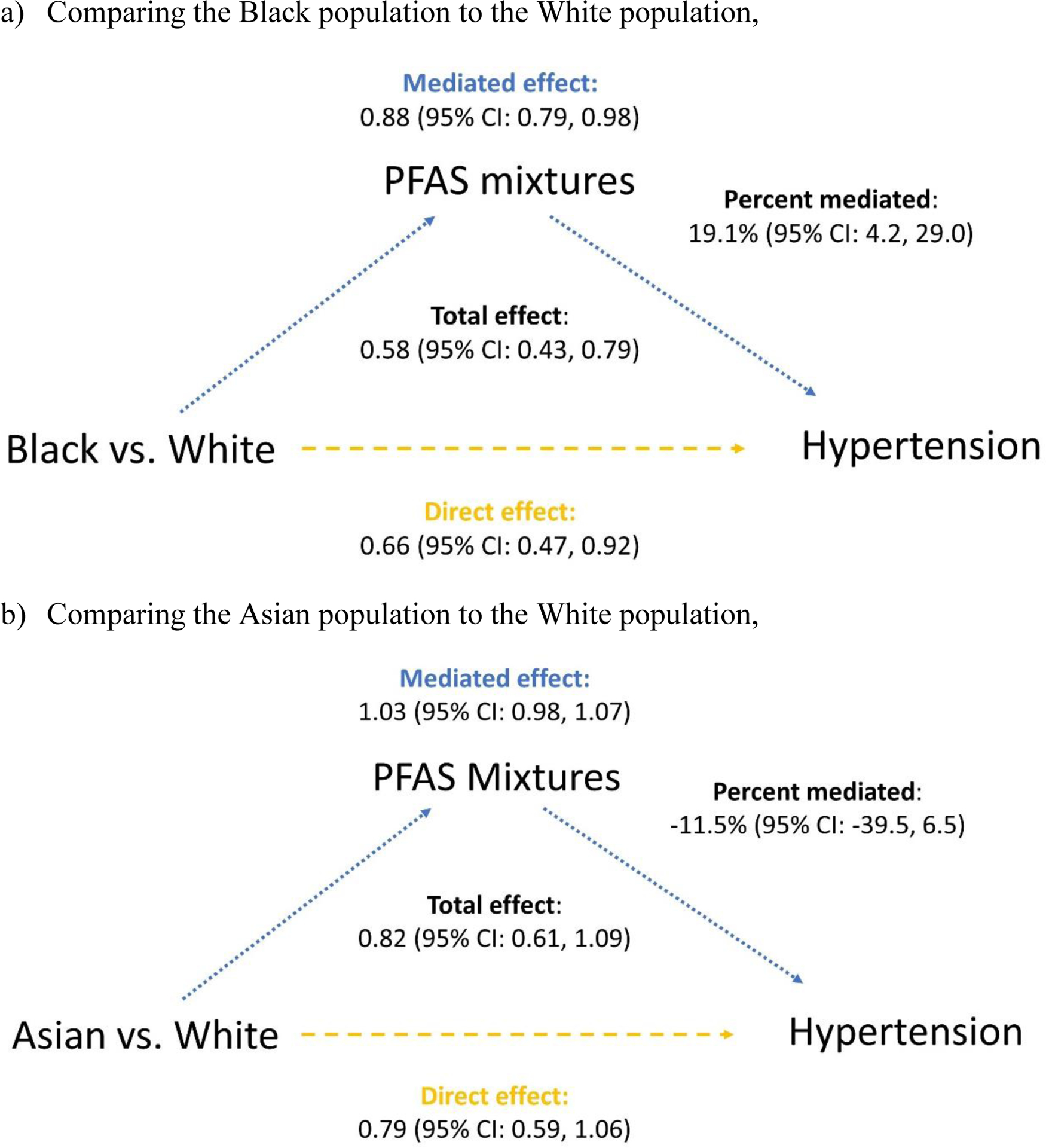

For PFAS mixtures, the quantile g-computation estimated β coefficients for all PFAS, as shown in Table S9, including n-PFOS (β=0.071), Sm-PFOS (β=0.011), EtFOSAA (β=0.058), MeFOSAA (β=0.086), n-PFOA (β=−0.003), PFNA (β=−0.001), and PFHxS (β=−0.071). These β coefficients were then incorporated as the weights into the construction of quantile g-computation estimator. The direct and mediated effects of racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension comparing Black with White participants were statistically significant (Figure 1). The direct effect had a relative survival of 0.66 (95% CI: 0.47, 0.92), which means the differences of 34% shorter time to hypertension that would remain if we were able to set the PFAS distributions in the Black population equal to that of the White population. The mediated effect was 0.88% (95% CI: 0.79, 0.98), which resulted in percent mediated of 19.1% (95% CI: 4.2, 29.0). In other words, 19.1% of the racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension could be explained by PFAS mixtures. With an interaction between race/ethnicity and PFAS mixtures, the percent eliminated was 22.3% (95% CI: 5.1, 33.2) if intervening overall PFAS concentrations to the 10th percentiles in our study population simultaneously. No significant mediation by PFAS mixtures was observed for differences in the development of hypertension comparing Asian with White participants.

Figure 1.

Mediation effects of PFAS mixtures on racial/ethnic disparities in incident hypertension, a) comparing the Black population with the White population: the controlled direct effect was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.46, 1.00) and percent eliminated was 22.3% (95% CI: 5.1, 33.2); b) comparing the Asian population with the White population: the controlled direct effect was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.53, 1.09) and percent eliminated was −9.2% (95% CI: −30.3, 5.4). Models were adjusted for age, study site, education, difficulty paying for basics, smoking status, environmental tobacco smoke, alcohol intake, menopausal status, physical activity, and total calorie intake at the MPS baseline.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that has examined the mediating role of PFAS exposure in racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension incidence. In this prospective cohort, PFAS were associated with significant and clinically meaningful race/ethnic differences in time to hypertension. A causal mediation analysis revealed that PFOS, and two precursors (EtFOSAA and MeFOSAA) explained around 7–10% of the differences observed in the time to onset of hypertension in Black compared to White participants. Using multipollutant approaches, we found PFAS mixtures could explain 19.1% of the Black-White disparities in hypertension. These findings emphasize the potential role of PFAS, a modifiable exposure, as an underlying cause of racial/ethnic disparities in timing of hypertension onset among midlife women.

Based on the more policy-relevant measure, i.e., percent eliminated, we calculated that if PFAS concentrations were reduced to the 10th percentile levels observed in SWAN MPS, 6–17% of the racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension could be eliminated. The interaction terms between race/ethnicity and PFAS in mediation analysis enable us to calculate the more policy-relevant measure, i.e., percent eliminated. We observed that by simultaneously reducing overall PFAS concentrations to the 10th percentiles in our study population, 22.3% of racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension could be eliminated. These findings suggest that interventions seeking to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension should consider strategies that facilitates effective reduction of potentially harmful environmental contaminants and exposure pathways.

PFAS are ubiquitously detected in the general population and in the environment. The voluntary phase-out of PFOA and PFOS by industries and regulatory bodies since 2000 in the United States (USEPA, 2003), has resulted in population-wide reduction in exposure to legacy compounds (Ding et al., 2020; Kato et al., 2015). However, PFAS are still widespread drinking water contaminants because they are mobile in groundwater, as well as persistent and bioaccumulative in the environment (Andrews and Naidenko, 2020; Post et al., 2017). Racial/ethnic differences in PFAS exposure have been documented in US adults: Black people tend to have higher concentrations of PFOS and their precursors EtFOSAA and MeFOSAA, while White women tended to have higher concentrations of PFOA (Boronow et al., 2019; Calafat et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2020). These differences may be due to living near areas contaminated with PFAS exposure such as airports and industrial areas (Hu et al., 2016). This exposure disparity reflects the ongoing marginalization of the Black community in the United States which often lives in more environmentally vulnerable areas, reflecting decades of structural racism. Future work needs more efforts to confirm our findings of the mediating role of PFAS in racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension. The observed results demonstrates an urgent need to develop PFAS guideline levels and standards to reduce Black-White disparities in exposure.

There is information available about PFAS levels in different brands of bottled water. Studies have found that some bottled water brands contain detectable levels of PFAS, although the levels vary widely depending on the brand and the specific type of PFAS (Chow et al., 2021). The Environmental Working Group (EWG) has tested several popular bottled water brands and found that some contained levels of PFAS that exceeded the EPA’s health advisory limit. There may be differences in bottled water consumption by race/ethnicity, although research in this area is limited. Bottled water could potentially be associated with higher exposure to PFAS in the population if the water contains detectable levels of PFAS. However, it’s important to note that many other sources of PFAS exposure exist, such as contaminated drinking water, food packaging, and household products. Individuals can reduce their exposure to PFAS by drinking filtered tap water or using a home water filtration system that is certified to remove PFAS, and by avoiding products that contain PFAS whenever possible.

As we have demonstrated, the unequal distributions of PFAS exposure across racial/ethnic groups can result in disparities in health outcomes. The elimination of health disparities, which is closely linked to social, economic, or environmental disadvantages, is one of the leading objectives of Health People 2030 in the United States (U.S. DHHS, 2021). Previous studies have explored neighborhood characteristics, built environment, air pollution, and exposure to heavy metals on obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and self-reported health, respectively (Piccolo et al., 2015; Rana et al., 2021; Sharifi et al., 2016; Song et al., 2020). Understanding the environmental causes that may amplify or moderate such disparities is central to achieving this objective, as environmental exposures possess social and economic attributes that are rooted in racial/ethnic differences in health outcomes.

Three cross-sectional studies have reported significant positive associations of specific PFAS with prevalent hypertension and elevated blood pressure (Bao et al., 2017; Min et al., 2012; Pitter et al., 2020). A previous study in SWAN MPS also found significant associations of PFOS, n-PFOA, EtFOSAA, and MeFOSAA with incident hypertension (Ding et al., 2021). These findings are supported by toxicological evidence. PFAS share structural similarity to fatty acids and can activate multiple nuclear receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) (Bjork et al., 2011; Hines et al., 2009). The ability of PFAS to interfere with PPARs have been put forward as an explanation for PFAS-induced cardiovascular disturbances since PPARs, especially PPARα is abundantly expressed in tissues with a high capacity for mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, such as the heart (Barger and Kelly, 2000; Gilde et al., 2003). In addition to the impact on nuclear receptors, PFAS exposure may also induce oxidative stress and cause endothelial dysfunction (Ceriello, 2008; Qian et al., 2010).

Certain products may contain PFAS that could contribute to higher levels of exposure in the Black population compared to the white population. For example, PFAS have been detected in some hair products, which are used to straighten and soften hair. PFAS have also been found in some food packaging and other consumer products, which may be more commonly used by the black community. However, this study does not provide data to explore the potential sources of PFAS. Based on previous findings, to reduce exposure, individuals can take steps such as avoiding products that contain PFAS or using them less frequently, reading labels carefully, and choosing safer alternatives when possible. Additionally, advocating for better regulation and transparency around the use of PFAS in consumer products can help protect public health.

This study has several strengths. This is the first study that applied a causal mediation framework to consider PFAS as a mediator to racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension. The longitudinal nature of SWAN makes it suitable for mediation analysis and causal inferences. The large, diverse group of community-based midlife women also enables exploration of racial/ethnic disparities in the development hypertension.

This study also has important limitation. First, 22% of the SWAN MPS had hypertension at baseline and were excluded from this analysis. Reeves et al. have previously demonstrated that left censoring is significant source of selection bias in the SWAN cohort and is differential by race/ethnicity (Reeves et al., 2022). We also acknowledged that the exclusion of women with prior hypertension could have led to a selection bias. The exclusion of women with prior hypertension may have disproportionately excluded Black women, who were more likely to develop hypertension at earlier ages. This could lead to an underestimation of the association between PFAS exposure and incident hypertension among Black women. With consideration of potential selection bias, our previous study show similar results with and without inverse probability weighting in the analysis (Ding et al., 2021). Furthermore, water is the main source of PFAS exposure and that marginalized communities, often composed of racially and ethnically minoritized people, are more likely to have lead-contaminated water. Residual confounding is possible (e.g., lead exposure). Thus, the study’s findings should be interpreted with caution, and the potential impact of unmeasured confounding factors on the observed association should be considered in the future research. Moreover, we calculated percent of elimination in racial/ethnic disparities by setting PFAS concentrations to the 10th percentiles. Because PFAS concentrations were measured at the MPS baseline (1999–2000), the 10th percentiles of PFAS concentrations, especially PFOA and PFOS, reflect peak exposure to PFAS and are now higher than the general population. Therefore, it could be hypothesized that the percent of racial/ethnic disparities eliminated by intervening on PFAS in today’s population might be correspondingly larger. Also, this cohort only included midlife Black, White, and Asian women, thus it is unknown whether these findings are applicable to men or to women in other life stages, including women of reproductive age, or other race/ethnicities. We were not able to include Hispanic women due to lack of biologic samples from Hispanic women in SWAN. Additionally, the study was conducted among women residing in Southeast Michigan, Boston, Pittsburgh, Oakland, and Los Angeles, which may not be representative of other populations in the United States. As a result, the study findings may not be generalizable to other populations with different geographic characteristics. Future research should confirm our findings in these other population groups. Finally, the study population was restricted to those who had an intact uterus. Women who received hysterectomy were not included, which could disproportionally impact those at younger ages or being Black. While the current study did not address the potential biases introduced by the inclusion criteria in SWAN, it is essential to recognize the potential impact on results and the need to address this limitation in future research.

CONCLUSIONS

Using data from the SWAN MPS, we have identified large, significant racial/ethnic disparities in the timing of hypertension onset, with 19.1% of the observed 42% earlier time to hypertension onset in midlife Black women compared to White women potentially mediated by environmental exposure to PFAS. By reducing the overall PFAS concentrations to the 10th percentiles, we could also eliminate the racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension by 22.3%. The magnitude of the observed mediation by PFAS was similar to and even greater than the level of mediation by other known risk factors such as BMI in the SWAN MPS population, suggesting that PFAS may play an important role in racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension.

Besides their theoretical importance, these findings have implications for public health policy, and support the importance of intervention efforts to reduce PFAS in drinking water as drinking water is one of the major sources of PFAS exposure (Sunderland et al., 2019). Currently no federal drinking water standards exist for PFAS in the U.S. despite widespread drinking water contamination and ubiquitous population-wide exposure. In 2016, the U.S. EPA released a non-enforceable lifetime health advisory for PFOA and PFOS at 70 parts per trillion (ppt), separately or combined(USEPA, 2016). Several U.S. states have adopted or proposed their own health-based drinking water guideline levels (Interstate Technology Regulatory Council, 2017) that range from 13 to 1000 ppt. Discrepancies in PFAS drinking water guidelines between the U.S. EPA and the states that adopted stricter guidelines Additional research focused on risk assessment for PFAS exposure for different drinking water consumption scenarios is urgently needed to provide evidence required to set PFAS drinking water guidelines.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

PFAS exposure may account for racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension incidence.

Certain PFAS could explain 7–10% of the Black-White disparities in hypertension.

PFAS mixtures could explain 19.1% of the Black-White disparities in hypertension.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061; U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). The study was supported by the SWAN Repository (U01AG017719).

This study was also supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) R01-ES026578, R01-ES026964, R01-ES031065 and P30-ES017885, and by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) grant T42-OH008455.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor - Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 - present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994-2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA - Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 - present; Robert Neer, PI 1994 - 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL - Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 - present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994 - 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser - Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles - Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY - Carol Derby, PI 2011 - present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010 - 2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004 - 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry - New Jersey Medical School, Newark - Gerson Weiss, PI 1994 - 2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA - Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD - Chhanda Dutta 2016- present; Winifred Rossi 2012-2016; Sherry Sherman 1994 - 2012; Marcia Ory 1994 - 2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD - Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor - Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

CDC Laboratory: Division of Laboratory Sciences, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

SWAN Repository: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor - Siobán Harlow 2013 - Present; Dan McConnell 2011 - 2013; MaryFran Sowers 2000 - 2011.

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA - Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012 - present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 - 2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995 - 2001.

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair

Chris Gallagher, Former Chair

We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EtFOSAA

2-(N-ethyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetate

- HT

hormone therapy

- MeFOSAA

2-(N-methyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetate

- N-PFOA

linear perfluorooctanoate

- N-PFOS

linear perfluorooctane sulfonate

- PFAS

per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances

- PFHxS

perfluorohexane sulfonate

- PFNA

perfluorononanoate

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- Sm-PFOS

sum of branched isomers of perfluorooctane sulfonate

- SWAN

Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation

- SWAN MPS

SWAN Multi-Pollutant Study

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- Al Kibria GM, 2019. Racial/ethnic disparities in prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension among US adults following application of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline. Prev. Med. Reports 14, 100850. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews DQ, Naidenko OV, 2020. Population-Wide Exposure to Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances from Drinking Water in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 7, 931–936. 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00713 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR, 2021. Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls. [PubMed]

- Bao WW, Qian Z, Geiger SD, Liu E, Liu Y, Wang SQ, Lawrence WR, Yang BY, Hu LW, Zeng XW, Dong GH, 2017. Gender-specific associations between serum isomers of perfluoroalkyl substances and blood pressure among Chinese: Isomers of C8 Health Project in China. Sci. Total Environ 607–608, 1304–1312. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger PM, Kelly DP, 2000. PPAR signaling in the control of cardiac energy metabolism. Trends Cardiovasc. Med 10.1016/S1050-1738(00)00077-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavia A, James-Todd T, Williams PL, 2019. Approaches for incorporating environmental mixtures as mediators in mediation analysis. Environ. Int 123, 368–374. 10.1016/J.ENVINT.2018.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JA, Butenhoff JL, Wallace KB, 2011. Multiplicity of nuclear receptor activation by PFOA and PFOS in primary human and rodent hepatocytes. Toxicology 288, 8–17. 10.1016/j.tox.2011.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L, 1986. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am. J. Epidemiol 124, 453–469. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boronow KE, Brody JG, Schaider LA, Peaslee GF, Havas L, Cohn BA, 2019. Serum concentrations of PFASs and exposure-related behaviors in African American and non-Hispanic white women. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019 292 29, 206–217. 10.1038/s41370-018-0109-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Wong L-Y, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL, 2007. Polyfluoroalkyl Chemicals in the U.S. Population: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 and Comparisons with NHANES 1999–2000. Environ. Health Perspect 115, 1596–1602. 10.1289/ehp.10598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RM, Cutler J, Friedewald W, Gant N, Hulley S, Iacono J, Maxwell M, McNellis D, Payne G, Shapiro A, Weiss S, 1985. The 1984 report of the joint national committee on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure. Nurse Pract. 10, 9–33. 10.1097/00006205-198507000-000033974955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2021. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. [PubMed]

- Ceriello A, 2008. Possible Role of Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Hypertension. 10.2337/dc08-s245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, Shah AM, Gupta DK, Skali H, Ni H, Rosamond WD, Heiss G, Folsom AR, Coresh J, Solomon SD, 2014. Temporal trends in the population attributable risk for cardiovascular disease: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circulation 130, 820–828. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ, 2003. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report. J. Am. Med. Assoc 289, 2560–2572. 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow SJ, Ojeda N, Jacangelo JG, Schwab KJ, 2021. Detection of ultrashort-chain and other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in U.S. bottled water. Water Res. 201, 117292. 10.1016/J.WATRES.2021.117292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghlin J, Hammond SK, Gann PH, 1989. Development of epidemiologic tools for measuring environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Am. J. Epidemiol 130, 696–704. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N, Harlow SD, Batterman S, Mukherjee B, Park SK, 2020. Longitudinal trends in perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances among multiethnic midlife women from 1999 to 2011: The Study of Women′s Health Across the Nation. Environ. Int 135. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM, Harlow SD, Park SK, 2022. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Incident Hypertension in Multi-Racial/Ethnic Women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Hypertension 79, 1876–1886. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM, Harlow SD, Park SK, 2021. Associations of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Incident Hypertension in Multi-Racial/Ethnic Women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ferris BG, 1978. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society). Am. Rev. Respir. Dis 118, 1–120. 10.1164/arrd.1978.118.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand LA, MacKinnon DP, DeRubeis RJ, Baraldi AN, 2016. Mediation analysis with survival outcomes: Accelerated failure time vs. proportional hazards models. Front. Psychol 7. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilde AJ, Van der Lee KAJM, Willemsen PHM, Chinetti G, Van der Leij FR, Van der Vusse GJ, Staels B, Van Bilsen M, 2003. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α and PPARβ/δ, but not PPARγ, modulate the expression of genes involved in cardiac lipid metabolism. Circ. Res 92, 518–524. 10.1161/01.RES.0000060700.55247.7C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu A, Yue Y, Desai RP, Argulian E, 2017. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Antihypertensive Medication Use and Blood Pressure Control Among US Adults With Hypertension: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003 to 2012. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 10. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow SD, Burnett-Bowie S-AM, Greendale GA, Avis NE, Reeves AN, Richards TR, Lewis TT, 2022. Disparities in Reproductive Aging and Midlife Health between Black and White women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Women’s midlife Heal. 8. 10.1186/S40695-022-00073-Y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines EP, White SS, Stanko JP, Gibbs-Flournoy EA, Lau C, Fenton SE, 2009. Phenotypic dichotomy following developmental exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in female CD-1 mice: Low doses induce elevated serum leptin and insulin, and overweight in mid-life. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 304, 97–105. 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung RW, Reed LD, 1990. Estimation of Average Concentration in the Presence of Nondetectable Values. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg 5, 46–51. 10.1080/1047322X.1990.10389587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XC, Andrews DQ, Lindstrom AB, Bruton TA, Schaider LA, Grandjean P, Lohmann R, Carignan CC, Blum A, Balan SA, Higgins CP, Sunderland EM, 2016. Detection of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in U.S. Drinking Water Linked to Industrial Sites, Military Fire Training Areas, and Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 3, 344–350. 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interstate Technology Regulatory Council, 2017. PFAS Fact Sheets [WWW Document]. URL https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/fact-sheets/ (accessed 8.7.18).

- Kato K, Basden BJ, Needham LL, Calafat AM, 2011a. Improved selectivity for the analysis of maternal serum and cord serum for polyfluoroalkyl chemicals. J. Chromatogr. A 1218, 2133–2137. 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Wong LY, Jia LT, Kuklenyik Z, Calafat AM, 2011b. Trends in exposure to polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: 1999–2008. Environ. Sci. Technol 45, 8037–8045. 10.1021/es1043613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Ye X, Calafat AM, 2015. PFASs in the General Population. Humana Press, Cham, pp. 51–76. 10.1007/978-3-319-15518-0_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keil AP, Buckley JP, O’Brien KM, Ferguson KK, Zhao S, White AJ, 2020. A quantile-based g-computation approach to addressing the effects of exposure mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect 128. 10.1289/EHP5838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Hedgepeth A, Lloyd-Jones DM, Colvin A, Matthews KA, Johnston J, Sowers MFR, Sternfeld B, Pasternak RC, Chae CU, 2008. Ethnic Differences in C-Reactive Protein Concentrations. Clin. Chem 54, 1027–1037. 10.1373/CLINCHEM.2007.098996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PID, Cardenas A, Hauser R, Gold DR, Kleinman KP, Hivert MF, Calafat AM, Webster TF, Horton ES, Oken E, 2020. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and blood pressure in pre-diabetic adults—cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. Environ. Int 137, 105573. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Dhana K, Furtado JD, Rood J, Zong G, Liang L, Qi L, Bray GA, DeJonge L, Coull B, Grandjean P, Sun Q, 2018. Perfluoroalkyl substances and changes in body weight and resting metabolic rate in response to weight-loss diets: A prospective study. PLoS Med. 15. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC, 2015. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 314, 1021–1029. 10.1001/JAMA.2015.10029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, Chen J, He J, 2016. Global Disparities of Hypertension Prevalence and Control: A Systematic Analysis of Population-Based Studies From 90 Countries. Circulation 134, 441–450. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min JY, Lee KJ, Park JB, Min KB, 2012. Perfluorooctanoic acid exposure is associated with elevated homocysteine and hypertension in US adults. Occup. Environ. Med 69, 658–662. 10.1136/oemed-2011-100288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi AI, Schnitzer ME, Moodie EEM, Bodnar LM, 2016. Mediation Analysis for Health Disparities Research. Am. J. Epidemiol 184, 315–324. 10.1093/AJE/KWV329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, Peng Q, Ding N, Mukherjee B, Halow S, 2019a. Distributions and determinants of per- and polyfluoroakyl substances ( PFASs ) in midlife women : Evidence of racial / ethnic residential segregation of PFAS exposure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Park SK, Peng Q, Ding N, Mukherjee B, Harlow SD, 2019b. Determinants of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in midlife women: Evidence of racial/ethnic and geographic differences in PFAS exposure. Environ. Res 175, 186–199. 10.1016/j.envres.2019.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, Zhao Z, Mukherjee B, 2017. Construction of environmental risk score beyond standard linear models using machine learning methods: application to metal mixtures, oxidative stress and cardiovascular disease in NHANES. Environ. Heal 16, 102. 10.1186/s12940-017-0310-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo RS, Duncan DT, Pearce N, McKinlay JB, 2015. The role of neighborhood characteristics in racial/ethnic disparities in type 2 diabetes: results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Soc. Sci. Med 130, 79–90. 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2015.01.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitter G, Zare Jeddi M, Barbieri G, Gion M, Fabricio ASC, Daprà F, Russo F, Fletcher T, Canova C, 2020. Perfluoroalkyl substances are associated with elevated blood pressure and hypertension in highly exposed young adults. Environ. Heal. 2020 191 19, 1–11. 10.1186/S12940-020-00656-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post GB, Gleason JA, Cooper KR, 2017. Key scientific issues in developing drinking water guidelines for perfluoroalkyl acids: Contaminants of emerging concern. PLoS Biol. 15, e2002855. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2002855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Ducatman A, Ward R, Leonard S, Bukowski V, Guo NL, Shi X, Vallyathan V, Castranova V, 2010. Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in human microvascular endothelial cells: Role in endothelial permeability. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. - Part A Curr Issues 73, 819–836. 10.1080/15287391003689317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana J, Renzetti S, Islam R, Donev M, Hu K, Oulhote Y, 2021. Mediation Effect of Metal Mixtures in the Association Between Socioeconomic Status and Self-rated Health Among US Adults: A Weighted Quantile Sum Mediation Approach. Expo. Heal 1–13. 10.1007/S12403-021-00439-Z/TABLES/5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves AN, Elliott MR, Lewis TT, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Herman WH, Harlow SD, 2022. Racial Differences in Cardio-Metabolic Disease Onset in a Cohort of Midlife Aging: The Role of Systematic Exclusion.

- Santoro N, Taylor ES, Sutton-Tyrrell K, 2011. The SWAN Song: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation’s Recurring Themes. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am 38, 417–423. 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi M, Sequist TD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Melly SJ, Duncan DT, Horan CM, Smith RL, Marshall R, Taveras EM, 2016. The role of neighborhood characteristics and the built environment in understanding racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 91, 103–109. 10.1016/J.YPMED.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Smith GS, Adar SD, Post WS, Guallar E, Navas-Acien A, Kaufman JD, Jones MR, 2020. Ambient air pollution as a mediator in the pathway linking race/ethnicity to blood pressure elevation: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ. Res 180. 10.1016/J.ENVRES.2019.108776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers MF, Tomey K, Jannausch M, Eyvazzadeh A, Nan B, Randolph J, 2007. Physical functioning and menopause states. Obstet. Gynecol 110, 1290. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000290693.78106.9A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternfeld B, Ainsworth BE, Quesenberry CP, 1999. Physical activity patterns in a diverse population of women. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 28, 313–323. 10.1006/pmed.1998.0470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland EM, Hu XC, Dassuncao C, Tokranov AK, Wagner CC, Allen JG, 2019. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 10.1038/s41370-018-0094-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. DHHS, 2021. Healthy People 2030 [WWW Document]. URL https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/healthy-people-2030-framework (accessed 12.18.21).

- USEPA, 2016. Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA).

- USEPA, 2003. Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Fluorinated Telomers; Request for Comment, Solicitation of Interested Parties for Enforceable Consent Agreement Development, and Notice of Public Meeting.

- Valeri L, VanderWeele TJ, 2013. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol. Methods 18, 137. 10.1037/A0031034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderweele TJ, 2013. Policy-relevant proportions for direct effects. Epidemiology 24, 175. 10.1097/EDE.0B013E3182781410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ, 2011. Causal mediation analysis with survival data. Epidemiology. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821db37e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR, 2014. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology 25, 473–484. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Mukherjee B, Batterman S, Harlow SD, Park SK, 2019a. Urinary metals and metal mixtures in midlife women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 222, 778–789. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Mukherjee B, Park SK, 2019b. Does Information on Blood Heavy Metals Improve Cardiovascular Mortality Prediction? J. Am. Heart Assoc 8, e013571. 10.1161/JAHA.119.013571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Mukherjee B, Park SK, 2018. Associations of cumulative exposure to heavy metal mixtures with obesity and its comorbidities among U.S. adults in NHANES 2003–2014. Environ. Int 121, 683–694. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassertheil-Smoller S, Anderson G, Psaty BM, Black HR, Manson JA, Wong N, Francis J, Grimm R, Kotchen T, Langer R, Lasser N, 2000. Hypertension and Its Treatment in Postmenopausal Women. Hypertension 36, 780–789. 10.1161/01.HYP.36.5.780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA, Williamson JD, Wright JT, Levine GN, O’Gara PT, Halperin JL, Past I, Al SM, Beckman JA, Birtcher KK, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Cigarroa JE, Curtis LH, Deswal A, Fleisher LA, Gentile F, Goldberger ZD, Hlatky MA, Ikonomidis J, Joglar JA, Mauri L, Pressler SJ, Riegel B, Wijeysundera DN, Walsh MN, Jacobovitz S, Oetgen WJ, Elma MA, Scholtz A, Sheehan KA, Abdullah AR, Tahir N, Warner JJ, Brown N, Robertson RM, Whitman GR, Hundley J, 2018. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 71, E13–E115. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065/-/DC2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Wang G, Zhang P, Fang J, Ayala C, 2017. Medical Expenditures Associated With Hypertension in the U.S., 2000–2013. Am. J. Prev. Med 53, S164–S171. 10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2017.05.014/ATTACHMENT/59D8E23B-3E94-4D4B-AE15-FFC74854A383/MMC1.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.