Abstract

Introduction:

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a genetic neuro-cutaneous disorder commonly associated with motor and cognitive symptoms that greatly impact quality of life. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) can quantify motor cortex physiology, reflecting the basis for impaired motor function as well as, possibly, clues for mechanisms of effective treatment. We hypothesized that children with NF1 have impaired motor function and altered motor cortex physiology compared to typically developing (TD) controls and children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Methods:

Children with NF1 aged 8–17 years (n=21) were compared to children aged 8–12 years with ADHD (n=59) and TD controls (n=88). Motor development was assessed using the Physical and Neurological Examination for Subtle Signs (PANESS) scale. The balance of inhibition and excitation in motor cortex was assessed using the TMS measures short interval cortical inhibition (SICI) and intracortical facilitation (ICF). Measures were compared by diagnosis and tested using bivariate correlations and regression for association with clinical characteristics.

Results:

In NF1, ADHD severity scores were intermediate between the ADHD and TD cohorts, but total PANESS scores were markedly elevated (worse) compared to both (p <0.001). Motor cortex ICF (excitatory) was significantly lower in NF1 compared to TD and ADHD (p <0.001), but SICI (inhibitory) did not differ. However, in NF1, better PANESS scores correlated with lower SICI ratios (more inhibition; ρ = 0.62, p = 0.003) and lower ICF ratios (less excitation; ρ = 0.38, p = 0.06).

Conclusion:

TMS-evoked SICI and ICF may reflect processes underlying abnormal motor function in children with NF1.

Keywords: Neurofibromatosis, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, Pediatric Neurology, motor development, biomarker

INTRODUCTION

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder with an estimated prevalence ranging from 1:2000 to 1:3000 births.1,2 NF1 is caused by a mutation in the NF1 gene,3 a tumor suppressor gene which produces the protein neurofibromin. NF1 is well known for its core diagnostic features, including café-au-lait macules, plexiform neurofibromas, and bone deformities.4 Neurologic manifestations commonly affecting childhood function and adult outcomes include learning disabilities, behavioral problems, and impaired executive function.5–8 In addition, children with NF1 often show significant impairments in coordination, speed, steadiness, balance, and/or gait.9–13 These deficits can impact function in a classroom setting14 and hinder participation in school, sports, and peer groups, thereby negatively impacting social and emotional development,15 quality of life, and psychological adjustment.16

Although both cognitive and motor impairments in NF1 negatively influence quality of life,14,15 rigorous studies targeting these symptoms in children, to date, have been limited. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of methylphenidate showed short-term improvement in ADHD symptoms.17 Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of lovastatin and simvastatin failed to demonstrate significant cognitive improvement.18,19 Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors’ cognitive effects have only been evaluated open-label.20 As is the case for many similar conditions, barriers to progress include reliance on subjective rating scales and the influence of motivation on performance. To track responsiveness to treatments more precisely, objective and robust biomarkers may be useful.21

The motor system provides an opportunity to identify indicators of clinical trial efficacy through quantitative assessments of both function and physiology. The developmental status of the motor control can be rated using the Physical and Neurological Examination for Subtle Signs (PANESS). The PANESS provides information on the maturation of the movement control system in childhood, capturing subtle abnormalities in motor control that are more common in children with developmental disorders.22 The physiology of the motor system can be evaluated using Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) paradigms that provide quantitative information regarding excitatory and inhibitory motor cortex physiology. Limited prior TMS studies in small adult NF1 cohorts have yielded some conflicting results.23–25 A study including 10 NF1 participants ages 9 to 53 years suggested a reduction in long interval cortical inhibition, which indexes GABA-B function.26

The aim of the current study was to explore whether PANESS scores and TMS measures might be appropriate measures of motor system function in NF1 to use as biomarkers for pediatric clinical trials. We evaluated children and adolescents with NF1 and compared these measures to data, collected using the same techniques, in typically developing children (TD) as well as children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). We compared motor physiology (resting motor threshold - RMT, short interval cortical inhibition – SICI, intracortical facilitation - ICF), motor function (PANESS scores and subscores) and behavioral symptoms (ADHD-RS scores and subscores) between NF1 youth and typically developing controls. In addition, we compared these findings to a cohort of children with ADHD to clarify whether some findings might be ADHD-related or distinct in NF1.

METHODS

Recruitment and phenotyping

Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians and assent from children and adolescents. The study was approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

NF1 – We recruited children with NF1, aged between 8–17 years old, from the NF1/RASopathies Program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center through in-clinic advertisements from 2012 to 2022. We recruited children who met NIH diagnostic criteria for NF1 and who, on review of medical records, had some evidence of difficulties with behavior or learning.27 To be included in the study, children needed to be otherwise generally medically healthy based on assessment of the clinical study team and be right-handed. ADHD or mild anxiety were allowed. Exclusion criteria included presence of a major psychiatric illness, based on medical record review and clinical psychological assessments, and full-scale IQ < 70 on the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (KBIT2).28 The DuPaul ADHD Rating Scale-IV (ADHD-RS) was used to assess ADHD symptoms.29 Use of mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors was exclusionary. Participants prescribed psychotropic medications were allowed but had to be stable for at least 30 days before entering. Only participants who agreed to undergo TMS testing were included in this analysis.

Comparison populations – ADHD and Typically Developing (TD) Controls Children ages 8–13 with ADHD and TD were selected from concurrent studies of motor development and motor physiology in childhood, recruited via community advertisements.30,31 Inclusion/exclusion criteria were the same as outlined above for NF1 participants with regard to other medical illness, cognitive status, handedness, and TMS safety.32,33 All participants underwent structured diagnostic interview using the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents or the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, K-SADS.34,35 Parents completed the ADHD-RS.29 TD children were free of any developmental or psychiatric diagnoses.

Motor Skill Assessment

Motor function was assessed via PANESS,22 using the same set of experienced raters for all participants. This test is composed of subscores that evaluate timed movements, lateral preference, motor overflow and persistence, dysrhythmia, coordination, gait, and balance, providing total and subscores for comparison.

Motor Cortex Physiology

Standard pre-TMS safety screening and methods were used.36 Detailed descriptions of all pediatric TMS procedures have been published previously.37 In brief, participants were seated in a comfortable chair with arms supported. Single- and paired-pulse TMS was administered using a Magstim 200 stimulator (Magstim Company, New York, NY) connected through a BiStim module to a round 90 mm coil placed tangential to the skull with its center near the vertex at the optimal position for producing a motor evoked potential (MEP) in the right first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscle. Electromyography (EMG) was recorded with surface electrodes, amplified, and filtered (100/1,000 Hz) (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) before being digitized at 2 kHz and stored for analysis using Signal software and a Micro1401 interface (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). For single-pulse and paired-pulse studies, all individual tracings were analyzed blinded and off-line.

For motor physiology, resting motor threshold (RMT) was evaluated and defined using conventional criteria.37,38 Thresholds indicate the ease of eliciting a motor evoked potential (MEP) – higher thresholds indicate a higher energy requirement. Paired pulse measures compare the MEP amplitude evoked by a single suprathreshold test pulse to the MEP amplitude evoked when the test pulse is preceded by a subthreshold conditioning pulse. The first, conditioning pulse activates interneurons which can have net inhibitory or excitatory effects such that the second, test pulse-evoked amplitude will be smaller or larger, on average, than the single-pulse evoked MEP.39 Thus, paired pulse studies quantify a balance, affected by various neurological conditions, of inhibitory and excitatory interneuronal inputs into motor cortex.40,41 Short interval cortical inhibition (SICI), the most common paired pulse measure, indexes the GABA-A inhibitory system.42 Intracortical facilitation (ICF) indexes excitatory inputs mediated by the glutamatergic system.43 We measured SICI and ICF together using standard methods.37,44 In brief, there were 60 trials, with an intertrial interval of 6 (+/−10%) seconds. There were 20 trials each under one of 3 conditions in randomized order: 1) single (test) pulses; 2) SICI: paired pulses (condition/test) at an inhibitory 3-ms interval; and 3) ICF: paired pulses (condition/test) at an excitatory 10-ms interval. The test pulse intensity was set above RMT at an intensity that yielded MEP amplitudes of 0.5–1.5 mV, usually 20% above RMT. The conditioning pulse intensity was set at 60% RMT. Trials with > 50 uV (peak to peak) artifact during 100 ms prior to TMS pulses were removed. SICI was calculated as the ratio of the mean of twenty 3-ms paired pulses to 20 single pulses; ICF was calculated as the ratio of 10-ms paired pulse to single pulses. For SICI and ICF, ratios < 1.0 indicate more inhibition and > 1.0 indicate more facilitation.

Statistical analyses

The primary objective was to determine whether motor function (PANESS) or motor physiology (TMS-RMT/SICI/ICF) differs in youth with NF1 compared to typically developing (TD) controls, as a means of exploring the potential of any of these measures to function as a biomarker in clinical trials targeting motor or cognitive function in NF1. However, given that children with NF1 often have ADHD, and differences in motor function and motor physiology have previously been identified in ADHD,37 an additional ADHD comparison group was included to help clarify whether any differences might be more specific to NF1. As there were no prior published studies with TMS data in children with NF1, no sample size calculation was performed prior to the study. Thus, for these primary analyses, the dependent variables were motor function (the total PANESS score) and motor physiology (RMT, SICI, and ICF) and the independent variable was diagnosis. The analysis approach was to test for a diagnosis effect first, followed, if appropriate, by post-hoc testing to determine whether the NF1 cohort differed from either TD or ADHD controls. All motor, physiological, and clinical data were assessed for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Diagnosis group comparisons were performed using Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; for comparisons of NF1 with each group, adjusted p-values were calculated using Holm’s post-hoc analysis. If Levene’s Test of Homogeneity of Variance was violated, the one-way Welch’s ANOVA (different variances) was conducted, and adjusted p-values were obtained using Games-Howell post-hoc testing. Post-hoc analysis is a statistical test done after ANOVA to determine if statistical differences exist between specific groups present in the ANOVA. If Shapiro-Wilk test for Normality was violated, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA (non-parametric) was conducted, and pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn test, and adjusted p-values to correct for multiple comparisons were obtained using the Holm’s method.

We anticipated that these measures of motor function and motor physiology might correlate with one another,37 but that any correlations might differ by diagnosis. Spearman rank coefficient was used to determine associations between motor physiology, motor function, and clinical characteristics (ADHD severity), stratified by diagnosis. To control for type I errors, we implemented the Holm procedure, to calculate adjusted p-values from the correlation matrix of demographics, motor function, motor physiology, and ADHD severity. There were differences in age and sex mix in the groups, and we were also interested in exploring sex effects in this study. Therefore, as a secondary approach, the same diagnosis analyses were repeated with a linear regression including sex and age. Least square means estimates for diagnostic effects were then generated for males and females.

We performed all statistical analyses and generated all plots with R, version 4.1.0.45–47 Analysis code and deidentified data sets are available upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

Demographics

The study sample included 21 subjects with NF1, 59 with ADHD, and 88 typically developing controls. The proportion of males to females was 3:2. The NF1 group had an average age 12.7 years compared to 10.5 and 10.8 for ADHD and TD control groups, respectively. Other demographic information is provided in Table 1. Although some group differences in demographics were present, only age is likely to have biased the results, and this is addressed in the regression and correlation analyses.

Table 1.

NF1 Neurofibromatosis type I. ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. TD Typically developing control children.

| Characteristic | N | Overall n = 1681 | NF1 n = 211 | ADHD n = 591 | TD n = 881 | p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Gender | 168 | 0.2 | ||||

| Female | 67 (40%) | 5 (24%) | 23 (39%) | 39 (44%) | ||

| Male | 101 (60%) | 16 (76%) | 36 (61%) | 49 (56%) | ||

| Race | 168 | 0.02 | ||||

| Asian | 5 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (5.7%) | ||

| Biracial | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.1%) | ||

| Black or African American | 29 (17%) | 1 (4.8%) | 7 (12%) | 21 (24%) | ||

| More Than One Race | 4 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (5.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Unknown or Not Reported | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| White | 127 (76%) | 19 (90%) | 48 (81%) | 60 (68%) | ||

| Ethnicity | 167 | <0.001 | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 6 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (10%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 160 (96%) | 19 (95%) | 53 (90%) | 88 (100%) | ||

| Unknown or Not Reported | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Age | 168 | 10.93 (1.81) | 12.75 (2.72) | 10.47 (1.53) | 10.80 (1.43) | 0.001 |

mean (sd) for continuous; n (%) for categorical

Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; p value is for 3-diagnostic-group comparison

Motor Function, Physiology, and ADHD severity

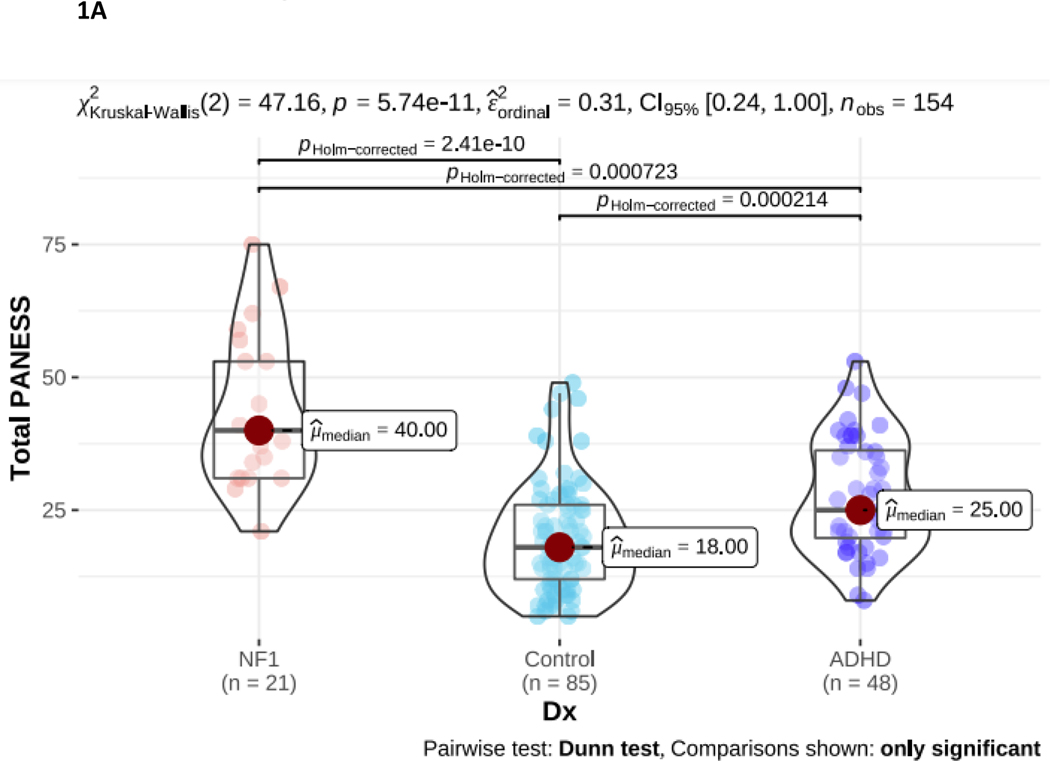

Clinical and motor system measures are shown in Table 2. Total PANESS scores differed significantly between groups (p < 0.001). Post-hoc comparisons show NF1 children had significantly greater total PANESS scores compared to both TD and ADHD (Figure 1A). This indicates that, despite having an older average age, the NF1 group had worse motor function than both comparison groups. Further, all PANESS subscores differed significantly between NF1 and TD, indicating pervasive problems across all motor domains. Between NF1 and ADHD, subscores for gait and station and timed tasks subscores differed significantly, with higher (worse) subscores observed in NF1. Gait/station and movement speed thus differentiate the NF1 cohort the most from both comparison groups.

Table 2.

NF1 Neurofibromatosis type I. ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. TD Typically developing control children. PANESS Physical and Neurological Examination of Subtle Signs. RMT Resting Motor Threshold. SICI Short interval cortical inhibition. ICF Intracortical facilitation. MSO Maximal Stimulator Output. ADHD-RS ADHD-rating scale. For PANESS, higher numbers indicate worse motor function. For RMT, higher numbers indicate more energy is required to evoke a response. SICI and ICF ratios are calculated as paired pulse TMS-evoked motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes over single pulse TMS-evoked MEP amplitudes. For SICI, a 1.0 ratio indicates no inhibition. Lower ratios, closer to 0, indicate more inhibition (more SICI). For ICF, a 1.0 ratio indicates no facilitation/excitation. Higher ratios > 1.0 indicate more facilitation (more ICF); ratios < 1.0 indicate negative facilitation. For ADHD-RS, higher rating scale scores indicate worse symptoms.

| Characteristic | n | ADHD n = 591 | TD n = 881 | NF1 n = 211 | p-value2 | Post-hoc NF1 vs TD3 | Post-hoc NF1 vs ADHD3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| PANESS | |||||||

| Total | 154 | 28 (11) | 19 (10) | 43 (14) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Right Overflow | 155 | 5 (3) | 3 (3) | 6 (4) | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.30 |

| Left Overflow | 155 | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 6 (4) | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.30 |

| Total Overflow | 155 | 11 (6) | 7 (6) | 13 (7) | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.30 |

| Gait and Stations | 155 | 7 (5) | 5 (4) | 14 (7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Timed Tasks | 155 | 20 (8) | 14 (7) | 29 (10) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Motor Cortex | |||||||

| RMT (%MSO) | 164 | 67 (17) | 65 (13) | 59 (11) | 0.20 | 0.086 | 0.094 |

| AMT (%MSO) | 160 | 43 (12) | 43 (10) | 44 (9) | 0.70 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| SICI ratio | 151 | 0.63 (0.24) | 0.46 (0.21) | 0.53 (0.26) | <0.001 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| ICF ratio | 151 | 1.14 (0.28) | 1.06 (0.32) | 0.84 (0.31) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ADHD-RS | |||||||

| Total Score | 147 | 34 (11) | 9 (8) | 25 (15) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| Inattentive Subscale | 147 | 19 (5) | 5 (4) | 15 (7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.06 |

| Hyperactive/Impulsive Subscale | 147 | 15 (7) | 4 (4) | 10 (8) | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.02 |

mean (sd) for continuous;

Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test;

Wilcoxon rank sum test;

Wilcoxon rank sum exact test

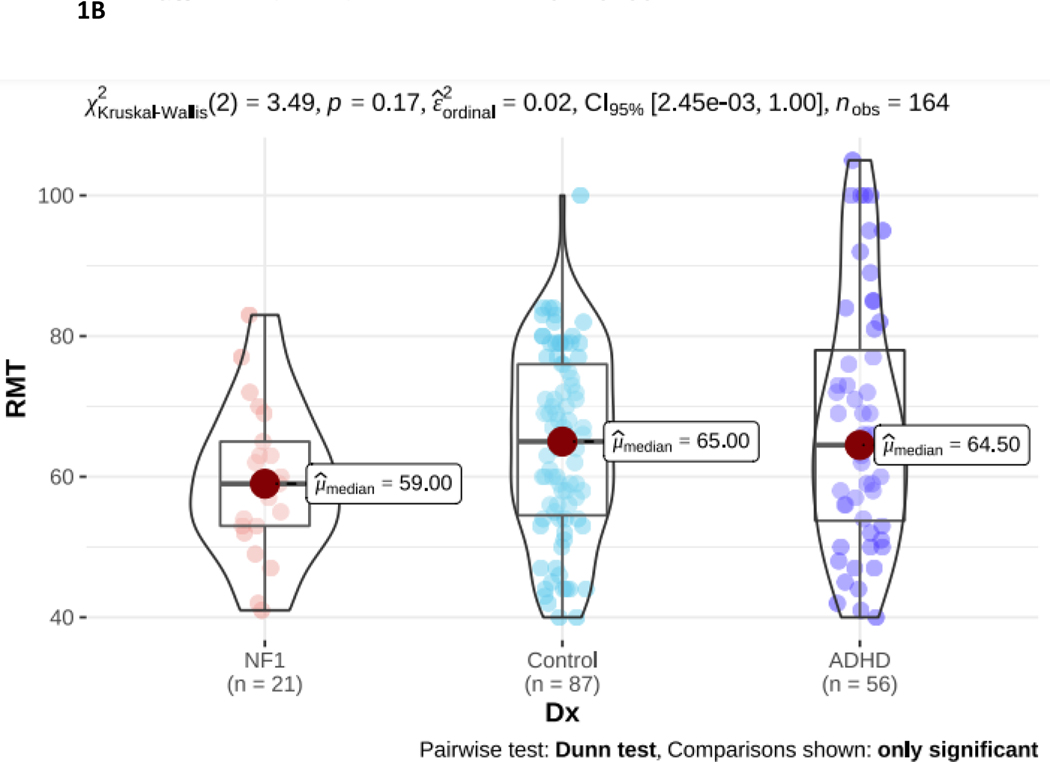

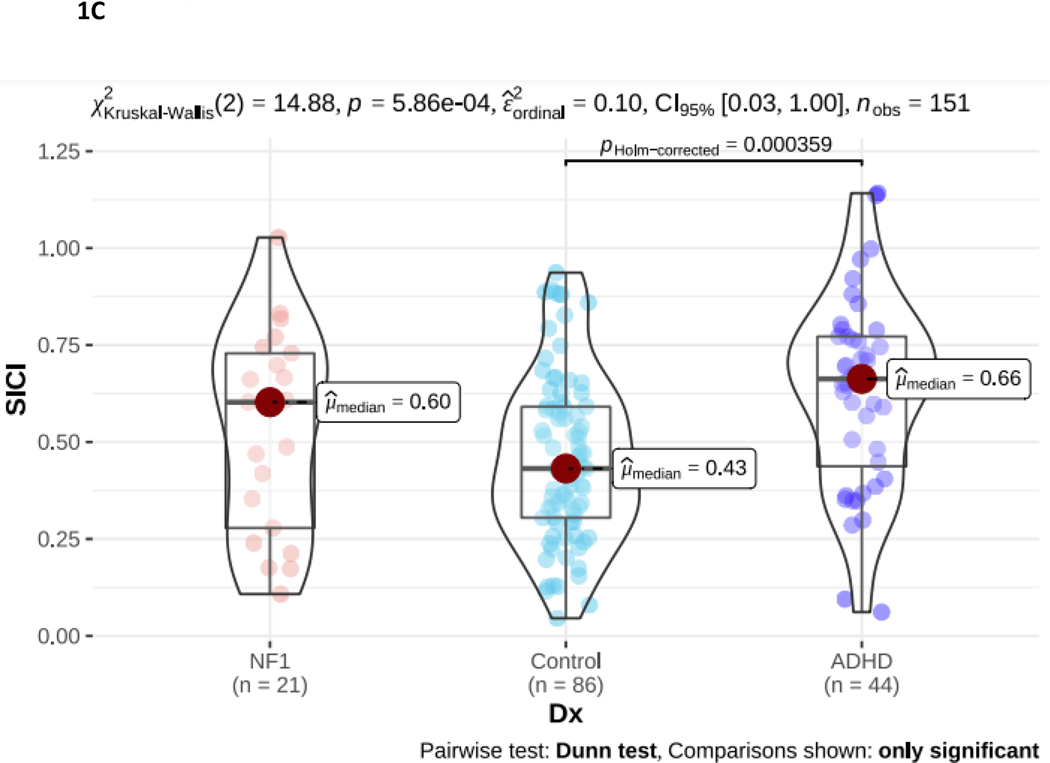

Figure 1.

NF1 Neurofibromatosis type I. ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. 1A. PANESS Physical and Neurological Examination of Subtle Signs. Higher numbers indicate worse motor function: NF1 > ADHD > TD. 1B. RMT Resting Motor Threshold. Higher numbers indicate more energy, as a percentage of maximum stimulator output, is required to evoke a response. There is no diagnostic group difference. 1C. SICI Short interval cortical inhibition. SICI is calculated as the 3-ms paired pulse TMS-evoked motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes over the single pulse TMS-evoked MEP amplitudes. For SICI, a 1.0 ratio indicates no inhibition. Lower ratios, closer to 0, indicate more inhibition (more SICI). In NF1, SICI did not differ from TD controls or from ADHD. 1D. ICF Intracortical facilitation. ICF ratios are calculated as the 10-ms paired pulse TMS-evoked motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes over the single pulse TMS-evoked MEP amplitudes. For ICF, a 1.0 ratio indicates no facilitation/excitation. Higher ratios > 1.0 indicate more facilitation (more ICF); ratios < 1.0 indicate negative facilitation. In NF1, ICF was significantly lower than both other groups.

The resting motor threshold (RMT; Figure 1B) was lowest in NF1 compared to ADHD and TD controls. However, these differences were not significant and likely relate to the older age of the NF1 cohort (as RMT decreases from childhood to adulthood). Both paired pulse measures differed significantly in NF1. There was also a significant between-group difference in SICI (p < 0.001; Figure 1C). However, post-hoc analysis indicates this is driven by reduced SICI (higher ratios) in the ADHD group. The NF1 group SICI overlapped with the ADHD and TD groups and did not differ significantly from either. Intracortical facilitation (ICF) ratio was 0.84 in NF1 compared to 1.06 TDC and 1.14 in ADHD (p < 0.001; Figure 1D), indicating that, on average, there is net negative facilitation in the NF1 cohort.

ADHD-RS differed significantly between groups (p < 0.001), and NF1 differed significantly from both groups. Severity of ADHD in NF1 was intermediate between the ADHD and TD cohorts in the total ADHD score as well as in the hyperactive/impulsive and inattentive subscores.

Regression analysis: diagnostic group effects, accounting for age and sex

PANESS scores and TMS measures, adjusted for age and sex, are shown in Table 3. Including age and sex in the regressions did not change the results of the prior analysis by diagnosis. In NF1, PANESS scores were still significantly elevated (worse) and ICF ratios were lower compared to both other groups. As expected, RMT is significantly influenced by age. A sex effect on PANESS was highly significant, with lower (better) scores for girls across all diagnostic groups.

Table 3.

NF1 Neurofibromatosis type I. ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. TDC Typically developing control children. PANESS Physical and Neurological Examination of Subtle Signs. RMT Resting Motor Threshold. SICI Short interval cortical inhibition. ICF Intracortical facilitation. MSO Maximal Stimulator Output. For PANESS, higher numbers indicate worse motor function. For RMT, higher numbers indicate more energy is required to evoke a response. SICI and ICF ratios are calculated as paired pulse TMS-evoked motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes over single pulse TMS-evoked MEP amplitudes. For SICI, a 1.0 ratio indicates no inhibition. Lower ratios, closer to 0, indicate more inhibition (more SICI). For ICF, a 1.0 ratio indicates no facilitation/excitation. Higher ratios > 1.0 indicate more facilitation (more ICF); ratios < 1.0 indicate negative facilitation. The measures are the dependent variables in the regression. The Dx F statistic and p value is for the regression model. The post hoc comparisons of interest are for NF1 vs ADHD and NF1 vs TD controls. Demographic analysis shows, for all participants, sex influenced PANESS scores (worse in males) and age influenced RMT (lower in older children, as expected).

| Measure | NF1 | ADHD | TDC | Dx Statistic | Post-hoc | Demographic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sex | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | F | p | vs ADHD | vs TDC | Age p | Sex p | |

| PANESS | male | 47.0 | 2.47 | 29 | 1.68 | 21.2 | 1.37 | 50.5 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.86 | 0.007 |

| female | 42.3 | 2.81 | 24.2 | 1.84 | 16.5 | 1.5 | |||||||

| RMT (% MSO) | male | 68.2 | 3.47 | 66.7 | 2.16 | 64.9 | 1.81 | 0.516 | 0.69 | NS | NS | <0.0001 | 0.38 |

| female | 66.3 | 3.04 | 64.8 | 1.92 | 63.1 | 1.67 | |||||||

| SICI ratio | male | 0.53 | 0.061 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 8.32 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.75 | 0.087 | 0.20 |

| female | 0.48 | 0.053 | 0.61 | 0.039 | 0.44 | 0.03 | |||||||

| ICF ratio | male | 0.85 | 0.083 | 1.15 | 0.055 | 1.07 | 0.045 | 6.08 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.87 |

| female | 0.84 | 0.073 | 1.14 | 0.052 | 1.06 | 0.04 | |||||||

Correlational Analyses

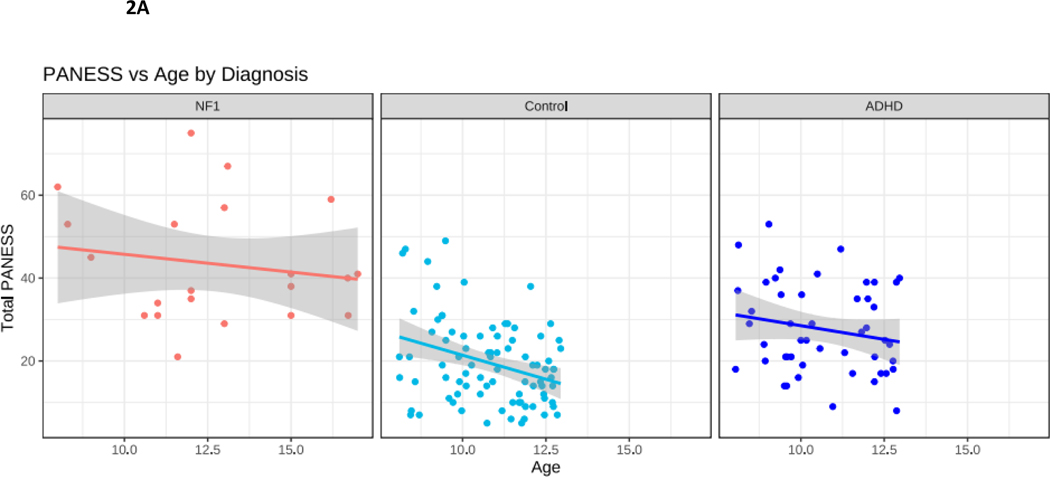

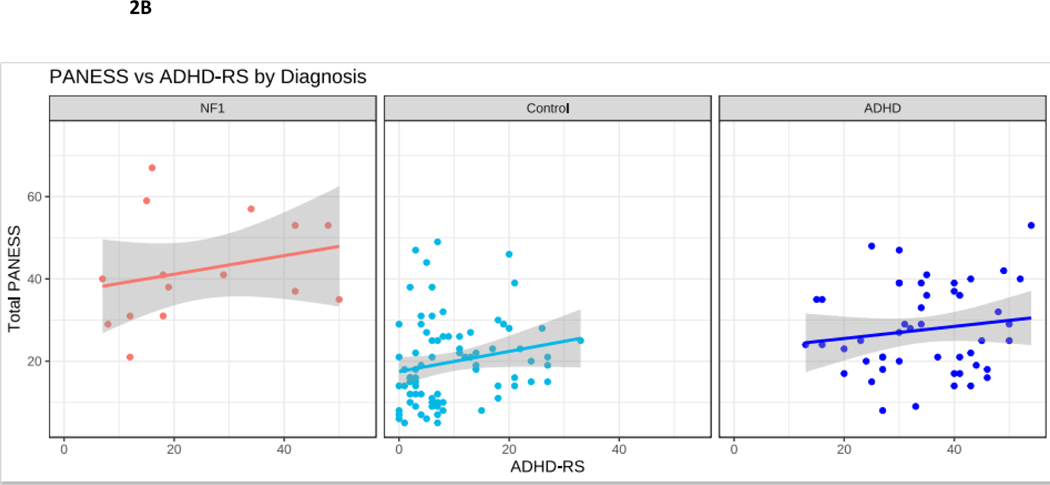

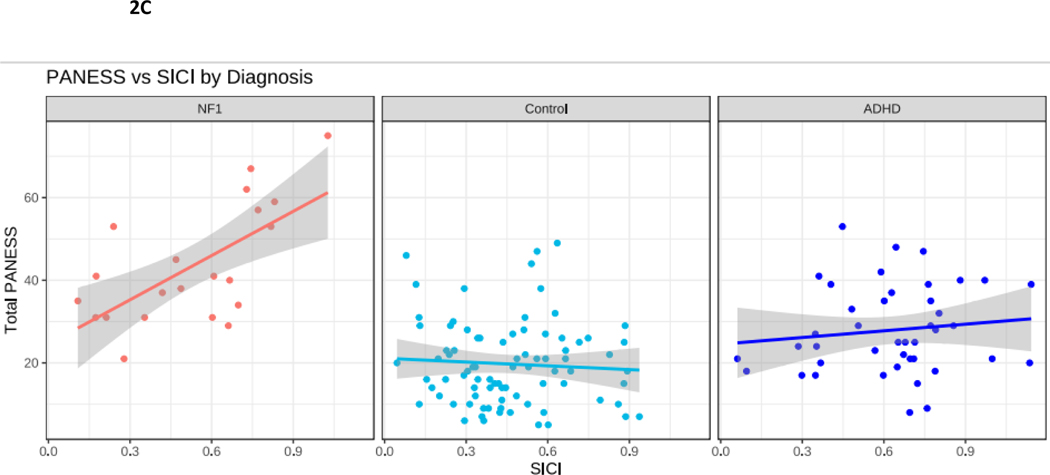

Correlational findings are presented in Table 4 and Figure 2. In TD children, motor skills improve with age. As expected, in our TD cohort, improved motor performance (lower total PANESS scores) was observed with increasing age (p = 0.01). To explore whether the trajectory of motor skill acquisition with age might differ in NF1, we performed correlations between PANESS scores and age. In youth with NF1, despite the relatively large spread of ages of participants (8-to-17 years), there was no association between older age and improved motor skills. In children with ADHD, there was also no correlation with age and PANESS (Figure 2A). Within NF1, PANESS scores did not correlate with ADHD ratings (Figure 2B).

Table 4.

NF1 Neurofibromatosis type I. ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. TD Typically developing control children. PANESS Physical and Neurological Examination of Subtle Signs. ADHD-RS ADHD Rating Scale. SICI Short interval cortical inhibition. ICF Intracortical facilitation. For PANESS and ADHD-RS, higher numbers indicate worse function/symptoms. SICI and ICF ratios are calculated as paired pulse TMS-evoked motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes over single pulse TMS-evoked MEP amplitudes. For SICI, a 1.0 ratio indicates no inhibition. Lower ratios, closer to 0, indicate more inhibition (more SICI). For ICF, a 1.0 ratio indicates no facilitation/excitation. Higher ratios > 1.0 indicate more facilitation (more ICF); ratios < 1.0 indicate negative facilitation. See also Figure 2.

| Correlation | N | Spearman (ρ) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PANESS vs Age | |||

| NF1 | 21 | −0.16 | NS |

| TD Control | 85 | −0.33 | 0.01 |

| ADHD | 48 | −0.19 | NS |

| PANESS vs ADHD-RS | |||

| NF1 | 15 | 0.29 | NS |

| TD Control | 78 | 0.27 | 0.02 |

| ADHD | 48 | 0.13 | NS |

| PANESS vs SICI | |||

| NF1 | 21 | 0.65 | 0.003 |

| TD Control | 83 | −0.07 | NS |

| ADHD | 42 | 0.12 | NS |

| PANESS vs ICF | |||

| NF1 | 21 | 0.38 | 0.06 |

| TD Control | 83 | −0.15 | 0.10 |

| ADHD | 42 | −0.06 | NS |

| SICI vs ICF | |||

| NF1 | 21 | 0.55 | 0.01 |

| TD Control | 86 | 0.06 | NS |

| ADHD | 44 | 0.01 | NS |

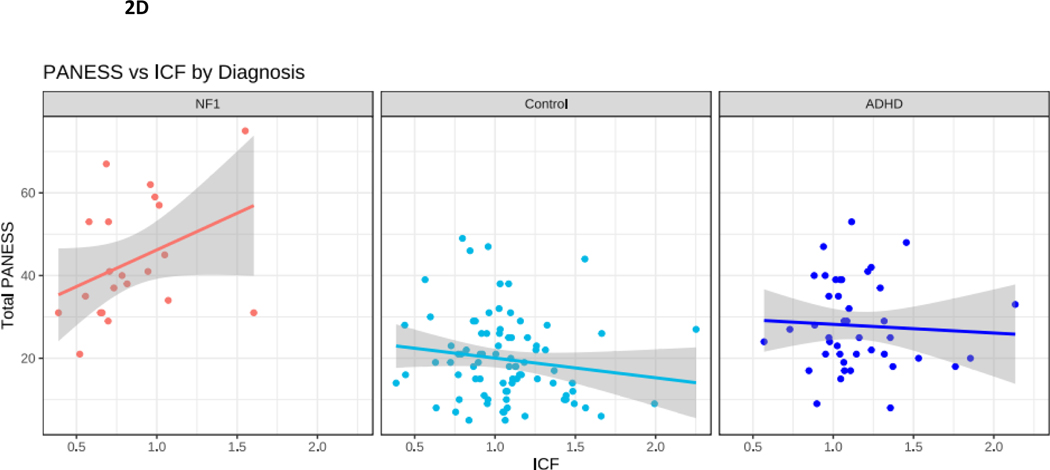

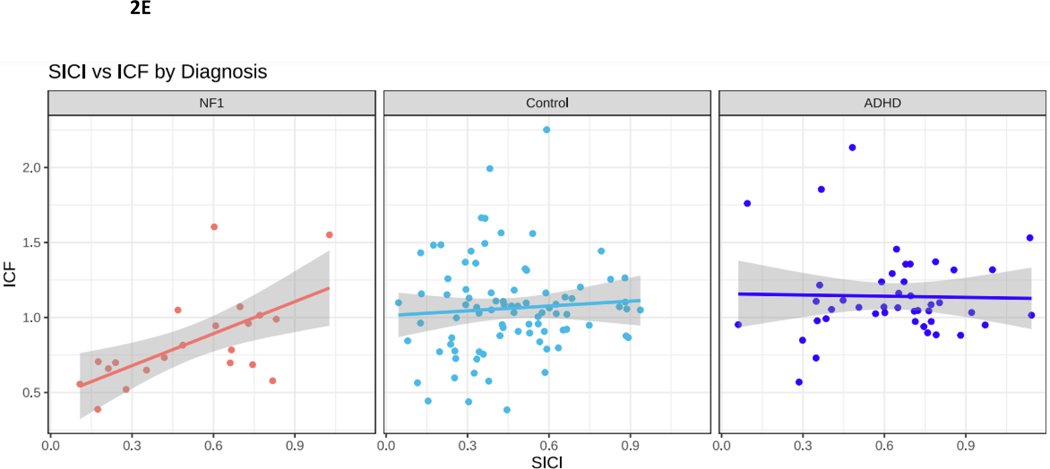

Figure 2.

NF1 Neurofibromatosis type I. Control typically developing children. ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. 2A. PANESS Physical and Neurological Examination of Subtle Signs. Higher numbers indicate worse motor function. In NF1, motor function does not improve with age, as it does in TD children. 2B. In NF1, ADHD-RS scores do not correlate with PANESS. 2C. SICI Short interval cortical inhibition. SICI is calculated as the 3-ms paired pulse TMS-evoked motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes over the single pulse TMS-evoked MEP amplitudes. For SICI, a 1.0 ratio indicates no inhibition. Lower ratios, closer to 0, indicate more inhibition (more SICI). In NF1, higher SICI ratios (less inhibition) correlate robustly with higher PANESS scores (worse motor function) (r = 0.65, p = 0.003). 2D. ICF Intracortical facilitation. ICF ratios are calculated as the 10-ms paired pulse TMS-evoked motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes over the single pulse TMS-evoked MEP amplitudes. For ICF, a 1.0 ratio indicates no facilitation/excitation. Higher ratios > 1.0 indicate more facilitation (more ICF); ratios < 1.0 indicate negative facilitation. In NF1, children with higher ICF ratios (more facilitation) tend to have higher PANESS scores (worse motor function) (r = 0.38; p = 0.06). 2E. In NF1, higher SICI ratios (less inhibition) correlate with higher ICF ratios (more facilitation) (r = 0.55; p = 0.01).

To explore whether deficits in motor function in NF1 are linked to differences in physiological measures in motor cortex, we performed correlations between total PANESS scores and the paired pulse TMS measures of motor physiology SICI and ICF. In individuals with NF1, there was a robust positive correlation between higher (worse) PANESS scores and increased SICI ratios (worse motor function, less inhibition; p = 0.003) (Figure 2C). Evaluating these PANESS findings further revealed correlations between less SICI (increased SICI ratio, less motor inhibition), and worse subscale scores for overflow movements (ρ = 0.48; p = 0.04) and timed tasks (ρ = 0.70; p < 0.001); but not gait and station (ρ = 0.18; p = 0.47). In other words, children with NF1 whose SICI ratios were more similar to those of ADHD children had worse motor function. In individuals with NF1, there was also a non-significant association between higher (worse) PANESS scores and higher ICF ratios (worse motor function, more facilitation; p = 0.06) (Figure 2D). Since, as a group, children with NF1 had lower ICF ratios, this means that children with NF1 whose ICF ratios were most similar to controls had poorer motor function. Evaluating these PANESS findings further revealed correlations between more ICF and worse subscale scores for timed tasks (ρ = 0.52; p = 0.02) but not overflow movements (ρ = 0.14; p = 0.55) or gaits and stations (ρ = −0.12; p = 0.61). Thus, in youth with NF1, motor function deficits are associated with both reduced SICI and relatively increased ICF, but the ICF findings appear to be driven mainly by speed of fine motor tasks.

Finally, as SICI and ICF are believed to index distinct populations of interneurons with inhibitory and excitatory input into motor cortex, we evaluated their correlations within each diagnosis, to determine whether motor cortex inhibition and excitation are linked or distinct (Figure 2E). In ADHD and TD these measures were not correlated. However, in youth with NF1, less facilitation was associated with more inhibition.

DISCUSSION

This study identified significantly worse motor development, indexed by higher PANESS scores, in youth ages 8 to 17 years with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) compared to typically developing (TD) controls and compared to children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Moreover, although ADHD scores (symptoms) were higher in NF1 than in TD controls, ADHD symptoms do not fully account for observed differences in maturation of motor function, since the NF1 group had both less severe ADHD symptoms and more severe motor impairment than the ADHD group. These results are consistent with a recent study showing that ADHD symptoms may not mediate deficits in motor skills in youth with NF113 and support the hypothesis that in NF1 a distinct pathophysiology contributes to motor deficits. Three novel findings in children with NF1 in this study are 1) markedly reduced Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)-evoked intracortical facilitation (ICF); 2) correlations between TMS measures and PANESS scores; and 3) correlations between SICI and ICF measures. ICF is believed to reflect cortical excitatory, glutamatergic neurotransmission. SICI is believed to reflect cortical inhibitory, GABAergic neurotransmission. Taken together, these results suggest that disturbances in the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission in motor cortex may contribute to the substantial motor impairments in youth with NF1.

Motor function

Early onset impaired motor function in NF1 has been demonstrated in multiple studies.10–12,48 The present study corroborates those findings, with worse function across all PANESS subscales. The relevance of impaired motor function to higher-level cognitive/ emotional difficulties in NF1 has also been suggested. For example, a comprehensive assessment of motor function in 46 youth ages 7 to 17 years with NF1 found modest, significant correlations between poor balance and perceptual reasoning and working memory.49 Recently, a study using the Motor Assessment Battery for Children (M-ABC) in a cohort of 30 8-to-12-year-old children with NF1 showed worse ball and balance skills compared to 31 children with ADHD (there was no control group). However, within NF1, the presence of ADHD did not predict worse scores. The authors concluded that motor deficits in NF1 vs. ADHD might have different pathophysiological mechanisms.13 Similarly, a study using the M-ABC in 69 children with NF1 ages 4 to 15 years reported that 40% of scores were in the clinically impaired (<6%ile) range for manual dexterity, ball skills, and balance.15 While these studies are informative, neither explored pathophysiological mechanisms. In contrast to the M-ABC, PANESS assessments we used also include motor overflow and impersistence, which may be more tightly linked to ADHD.37

Motor physiology - inhibition

Measurements of motor cortex physiology can probe and quantify capacity in multiple inhibitory and excitatory systems. Short interval cortical inhibition (SICI) is a widely studied measure believed to reflect GABA-A receptor capacity in inhibitory interneurons in motor cortex.50,51 Reduced SICI (higher ratios) has been reported in multiple studies of children51,52 and adults53 with ADHD, Parkinson disease,54 and dementia.55 In our study, the NF1 group mean SICI ratio was intermediate between the group means for ADHD (higher SICI ratio = less inhibition) and TD controls (lower SICI ratio = more inhibition), paralleling the location of group means for ADHD clinical symptoms (ADHD > NF1 > TD). Notably, the SICI findings corroborate correlational studies linking greater ADHD symptoms to less SICI.37 In NF1, children with more SICI had better PANESS scores – i.e. more mature motor development. This was notable particularly in faster performance of timed tasks and better suppression of motor overflow. This correlation suggests that youth with NF1 who have greater levels of SICI may have better motor function.

The basis for these SICI/PANESS findings may involve dysregulation of cortical networks responsive to the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. In children, we previously reported that more motor cortex GABA, measured with magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), correlated with less SICI (higher ratios).51 The possibility that more GABA/less SICI indexes worse motor or behavioral function in children with NF1 is broadly consistent with findings in several animal models implicating excess GABA in the pathophysiology of NF1-related impairments.56,57 For example, one study reported that mutated neurofibromin (Nf1) in inhibitory interneurons modulates excess GABA release which in turn impairs learning.58 Related learning deficits in these Nf1 heterozygous mutants could be reversed by GABA antagonists, i.e. lowering GABA.57

It is worth noting here that, while TMS studies in youth with NF1 have not been published previously, several studies have reported SICI in adults with NF1, with inconsistent results.23–25,59 An additional conundrum at present is that, while NF1 animal models implicate a pathophysiological role for excess GABA, the opposite has been supported by a pilot study using MRS to measure cortical GABA in motor cortex children.60 Further, it is not clear, at least in adults, to what extent SICI will be sensitive to treatment. An exploratory, multi-modal TMS and magnetic resonance spectroscopy study in adults with NF1 showed no effect of lovastatin on SICI, ICF, or cortical concentrations of GABA and Glutamate (Glx).61

Motor physiology - excitation

ICF is a measure believed to reflect glutamatergic as well as to a lesser degree GABAergic capacity in interneurons in motor cortex.62 ICF is reduced among children with autism who also have ADHD63 and is also reduced in various dementias, correlating with severity.64 In the present study, youth with NF1 had significantly lower ICF ratios (less motor cortex excitation) than the TD cohort. However, paradoxically and in contrast to the findings in dementia, our data suggest that better (less impaired) motor function might be associated with lower (farther from normal) ICF. In other words, while youth with NF1 as a group had less ICF, individuals with NF1 whose ICF ratios were the lowest had, relative to other NF1 patients, better motor function. In NF1 participants, lower ICF ratios also correlated with lower SICI ratios. Thus, we speculate that low ICF, or possibly a synchronicity between ICF and SICI, may be linked to better motor function, possibly as a protective or compensatory phenomenon. Measurements of GABA and Glutamate in motor cortex using magnetic resonance spectroscopy might help to clarify this. An intriguing implication is that pharmacological interventions that modulate glutamate and GABA and that decrease SICI and/or ICF ratios might improve motor function in NF1.

Our findings differ somewhat from two small prior studies of NF1, which did not show ICF reductions.26,59 Differences in participant age, motor skill phenotype, and TMS technique might have contributed to this discrepancy.

Limitations

An obvious limitation of this study is sample size. All findings in this paper should be replicated in a larger sample of youth with NF1. A second caveat is that the data for the two comparator groups were collected in other studies. This analysis compared NF1 motor function and physiology data to contemporaneously collected, published30,31 data from children with ADHD and TDC. The same research team conducted the PANESS and TMS data collection in all 3 cohorts, and TMS data was analyzed blinded to results of PANESS and behavioral studies. Thus, we do not think this study design introduced any systematic bias. A third significant limitation of this study is the older age in the NF1 group compared to the ADHD and TD group, although this should have biased PANESS scores to be lower in NF1, the opposite of what we found. Finally, this NF1 cohort was a convenience-sample recruited from an NF1 specialty clinic. Recruitment efforts targeted youth with concerns about motor or cognitive abilities. Thus, although we screened out potential participants with low IQ scores, our sample may nonetheless be biased toward youth with more motor or behavioral impairment. Future studies may benefit from evaluating a broader sample in terms of both demographics and neurobehavioral function.

Conclusion

Impaired motor function remains a large contributor to morbidity in patients with NF1. Further characterization of motor function and motor physiology measures using PANESS and TMS should be considered as potential quantitative markers and indicators of pathophysiology and treatment responses in children with NF1. These may provide some benefit as biomarkers in treatment development.

Highlights.

Patients with NF1 have a high degree of motor impairment, particularly in timed tasks.

Motor cortex ICF was significantly lower in NF1 compared to TD and ADHD.

PANESS scores and SICI ratios were strongly correlated in NF1.

Patients with NF1 had worse motor impairment than ADHD group despite lower ADHD scores.

TMS should be considered as quantitative markers for indicators of treatment responses.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the Department of Defense DOD W81XWH2010139, CCHMC Translational Research Initiative/ Neurofibromatosis Center Pilot Award Program, R01 NS096207, T35 DK060444, and the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine summer research program, R01 MH095014. Our funding sources were not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. The research team is grateful for the time committed from the participants and their families.

Footnotes

Dr. Donald Gilbert reports a relationship with U.S. National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program that includes: paid expert testimony. Dr. Donald Gilbert reports a relationship with Applied Therapeutics Inc that includes: consulting or advisory. Dr. Donald Gilbert reports a relationship with Advanced Medicine and Telemedicine Diagnosis Centre that includes: consulting or advisory. Dr. Donald Gilbert reports a relationship with National Institutes of Health that includes: funding grants. Dr. Brittany Simpson reports a relationship with AstraZeneca that includes: funding grants. Book Royalties from Elsevier and Wolters Kluwer- Dr. Donald Gilbert.

Clinical Trial Site Investigator for Emalex, EryDel, PTC Therapeutics- Dr. Donald Gilbert

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DAS. Von Recklinghausen Neurofibromatosis. Brain 1988;111(6):1355–1381, DOI: 10.1093/brain/111.6.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uusitalo E, Leppävirta J, Koffert A, et al. Incidence and mortality of neurofibromatosis: a total population study in Finland. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135(3):904–906, DOI: 10.1038/jid.2014.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballester R, Marchuk D, Boguski M, et al. The NF1 locus encodes a protein functionally related to mammalian GAP and yeast IRA proteins. Cell 1990;63(4):851–859, DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legius E, Messiaen L, Wolkenstein P, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 and Legius syndrome: an international consensus recommendation. Genetics in Medicine 2021;23(8):1506–1513, DOI: 10.1038/s41436-021-01170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine TM, Materek A, Abel J, O’Donnell M, Cutting LE. Cognitive Profile of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Seminars in pediatric neurology 2006;13(1):8–20, DOI: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.North K, Hyman S, Barton B. Cognitive deficits in neurofibromatosis 1. Journal of child neurology 2002;17(8):605–612, DOI: 10.1177/088307380201700811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehtonen A, Howie E, Trump D, Huson SM. Behaviour in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: cognition, executive function, attention, emotion, and social competence: Review. Developmental medicine and child neurology 2013;55(2):111–125, DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson BA, Macwilliams BA, Carey JC, Viskochil DH, D’Astous JL, Stevenson DA. Motor Proficiency in Children With Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Pediatric Physical Therapy 2010;22(4):344–348, DOI: 10.1097/pep.0b013e3181f9dbc8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore BD, Slopis JM, Schomer D, Jackson EF, Levy BM. Neuropsychological significance of areas of high signal intensity on brain MRIs of children with neurofibromatosis. Neurology 1996;46(6):1660–1668, DOI: 10.1212/WNL.46.6.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldmann R, Denecke J, Grenzebach M, Schuierer G, Weglage J. Neurofibromatosis type 1: Motor and cognitive function and T2-weighted MRI hyperintensities. Neurology 2003;61(12):1725–1728, DOI: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000098881.95854.5F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.North K, Joy P, Yuille D, et al. Specific learning disability in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: significance of MRI abnormalities. Neurology 1994;44(5):878–883, DOI: 10.1212/wnl.44.5.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman CA, Waber DP, Bassett N, Urion DK, Korf BR. Neurobehavioral profiles of children with neurofibromatosis 1 referred for learning disabilities are sex-specific. Am J Med Genet 1996;67(2):127–132, DOI:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas-Lude K, Heimgartner M, Winter S, Mautner VF, Krageloh-Mann I, Lidzba K. Motor dysfunction in NF1: Mediated by attention deficit or inherent to the disorder? Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2018;22(1):164–169, DOI: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krab LC, Aarsen FK, De Goede-Bolder A, et al. Impact of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 on School Performance. Journal of child neurology 2008;23(9):1002–1010, DOI: 10.1177/0883073808316366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rietman AB, Oostenbrink R, Bongers S, et al. Motor problems in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Neurodev Disord 2017;9:19, DOI: 10.1186/s11689-017-9198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graf A, Landolt MA, Mori AC, Boltshauser E. Quality of life and psychological adjustment in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr 2006;149(3):348–353, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lion-François L, Gueyffier F, Mercier C, et al. The effect of methylphenidate on neurofibromatosis type 1: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:142, DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payne JM, Barton B, Ullrich NJ, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled study of lovastatin in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology 2016;87(24):2575–2584, DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000003435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Vaart T, Plasschaert E, Rietman AB, et al. Simvastatin for cognitive deficits and behavioural problems in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1-SIMCODA): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2013;12(11):1076–1083, DOI: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh KS, Wolters PL, Widemann BC, et al. Impact of MEK Inhibitor Therapy on Neurocognitive Functioning in NF1. Neurology Genetics 2021;7(5):e616, DOI: 10.1212/nxg.0000000000000616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahin M, Jones SR, Sweeney JA, et al. Discovering translational biomarkers in neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, DOI: 10.1038/d41573-018-00010-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denckla MB. Revised Neurological Examination for Subtle Signs (1985). Psychopharmacol Bull 1985;21(4):773–800, DOI: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castricum J, Tulen JHM, Taal W, Ottenhoff MJ, Kushner SA, Elgersma Y. Motor cortical excitability and plasticity in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin Neurophysiol 2020;131(11):2673–2681, DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimerman M, Wessel MJ, Timmermann JE, et al. Impairment of Procedural Learning and Motor Intracortical Inhibition in Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Patients. EBioMedicine 2015;2(10):1430–1437, DOI: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mainberger F, Jung NH, Zenker M, et al. Lovastatin improves impaired synaptic plasticity and phasic alertness in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. BMC Neurol 2013;13:131, DOI: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacroix A, Proteau-Lemieux M, Côté S, et al. Multimodal assessment of the GABA system in patients with fragile-X syndrome and neurofibromatosis of type 1. Neurobiology of Disease 2022;174:105881, DOI: 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Legius E, Messiaen L, Wolkenstein P, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 and Legius syndrome: an international consensus recommendation. Genet Med 2021;23(8):1506–1513, DOI: 10.1038/s41436-021-01170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children 4th ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation Vol 25: Guilford Press New York; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert D, Wu S, Horn P, Pedapati E, Mostofsky S. Reduced motor cortex modulation during response inhibition task correlates with worse performance more severe clinical and motor impairment in children with ADHD. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation 2019;12(2):417, DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.12.351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu SW, Gilbert DL, Shahana N, Huddleston DA, Mostofsky SH. Transcranial magnetic stimulation measures in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr. Neurol 2012;47(3):177–185, DOI: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong YH, Wu SW, Pedapati EV, et al. Safety and tolerability of theta burst stimulation vs. single and paired pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation: a comparative study of 165 pediatric subjects. Front Hum Neurosci 2015;9:29, DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossi S, Antal A, Bestmann S, et al. Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. Clin. Neurophysiol 2021;132(1):269–306, DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reich W. Diagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39(1):59–66, DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Perepletchikova F, Brent D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL 2013, DSM-5). Western Psychiatric Institute and Yale University 2013, DOI: [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossi S, Antal A, Bestmann S, et al. Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. Clin Neurophysiol 2021;132(1):269–306, DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert DL, Isaacs KM, Augusta M, Macneil LK, Mostofsky SH. Motor cortex inhibition: a marker of ADHD behavior and motor development in children. Neurology 2011;76(7):615–621, DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820c2ebd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mills KR, Nithi KA. Corticomotor threshold to magnetic stimulation: Normal values and repeatability. Muscle & nerve 1997;20(5):570–576, DOI: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, et al. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol 1993;471:501–519, DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridding MC, Sheean G, Rothwell JC, Inzelberg R, Kujirai T. Changes in the balance between motor cortical excitation and inhibition in focal, task specific dystonia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 1995;59(5):493–498, DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mimura Y, Nishida H, Nakajima S, et al. Neurophysiological biomarkers using transcranial magnetic stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020, DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Lazzaro V, Pilato F, Dileone M, et al. GABAA receptor subtype specific enhancement of inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol 2006;575(Pt 3):721–726, DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liepert J, Schwenkreis P, Tegenthoff M, Malin JP. The glutamate antagonist riluzole suppresses intracortical facilitation. Journal of Neural Transmission - General Section 1997;104(11–12):1207–1214, DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, et al. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol 1993;471:501–519, DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patil I. Visualizations with statistical details: The’ggstatsplot’approach. Journal of Open Source Software 2021;6(61):3167, DOI: [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patil I. statsExpressions: R package for tidy dataframes and expressions with statistical details. Journal of Open Source Software 2021;6(61):3236, DOI: [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sjoberg DD, Whiting K, Curry M, Lavery JA, Larmarange J. Reproducible Summary Tables with the gtsummary Package. R Journal 2021;13(1), DOI: [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lorenzo J, Barton B, Acosta MT, North K. Mental, motor, and language development of toddlers with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr 2011;158(4):660–665, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Champion JA, Rose KJ, Payne JM, Burns J, North KN. Relationship between cognitive dysfunction, gait, and motor impairment in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014;56(5):468–474, DOI: 10.1111/dmcn.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothwell JC, Day BL, Thompson PD, Kujirai T. Short latency intracortical inhibition: one of the most popular tools in human motor neurophysiology. J Physiol 2009;587(Pt 1):11–12, DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.162461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris AD, Gilbert DL, Horn PS, et al. Relationship between GABA levels and task-dependent cortical excitability in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin. Neurophysiol 2021;132(5):1163–1172, DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2021.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moll GH, Heinrich H, Trott G-E, Wirth S, Bock N, Rothenberger A. Children With Comorbid Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder and Tic Disorder: Evidence for Additive Inhibitory Deficits Within the Motor System. Ann Neurol 2001;49(3):393–396, DOI: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eichhammer P, Laufkotter R, Langguth B, Frank E, Hajak G. Cortical Excitability in patients with adult ADHD. Pharmacopsychiatry 2003;36(DOI: 10.1055/s-2003-825315), DOI: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ni Z, Bahl N, Gunraj CA, Mazzella F, Chen R. Increased motor cortical facilitation and decreased inhibition in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2013;80(19):1746–1753, DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182919029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benussi A, Grassi M, Palluzzi F, et al. Classification Accuracy of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for the Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Dementias. Ann Neurol 2020;87(3):394–404, DOI: 10.1002/ana.25677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Costa RM, Federov NB, Kogan JH, et al. Mechanism for the learning deficits in a mouse model of neurofibromatosis type 1. Nature 2002;415(6871):526–530, DOI: 10.1038/nature711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cui Y, Costa RM, Murphy GG, et al. Neurofibromin regulation of ERK signaling modulates GABA release and learning. Cell 2008;135(3):549–560, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goncalves J, Violante IR, Sereno J, et al. Testing the excitation/inhibition imbalance hypothesis in a mouse model of the autism spectrum disorder: in vivo neurospectroscopy and molecular evidence for regional phenotypes. Mol Autism 2017;8:47, DOI: 10.1186/s13229-017-0166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Germanidis EI, Schulz R, Quandt F, Mautner VF, Gerloff C, Timmermann JE. Intact procedural learning and motor intracortical inhibition in adult neurofibromatosis type 1 gene carriers. Clinical Neurophysiology 2021;132(9):2037–2045, DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2021.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ribeiro MJ, Violante IR, Bernardino I, Edden RA, Castelo-Branco M. Abnormal relationship between GABA, neurophysiology and impulsive behavior in neurofibromatosis type 1. Cortex 2015;64:194–208, DOI: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernardino I, Dionísio A, Castelo-Branco M. Modulation of Cortical Inhibition by Lovastatin in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. 2022, DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paulus W, Classen J, Cohen LG, et al. State of the art: Pharmacologic effects on cortical excitability measures tested by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Stimul 2008;1(3):151–163, DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pedapati EV, Mooney LN, Wu SW, et al. Motor cortex facilitation: a marker of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder co-occurrence in autism spectrum disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2019;9(1):298, DOI: 10.1038/s41398-019-0614-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benussi A, Dell’Era V, Cantoni V, et al. TMS for staging and predicting functional decline in frontotemporal dementia. Brain Stimul 2020;13(2):386–392, DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2019.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]