Abstract

Quantum mechanical second order Møller–Plesset (MP2) perturbation theory and density functional theory (DFT) Becke, 3-parameter, Lee-Yang-Parr (B3LYP) and Minnesota 2006 local functional (M06L) calculations were performed to optimize structure of nirmatrelvir and compute the Merz-Kollman electrostatic potential (MK ESP), natural population analysis (NPA), Hirshfeld, charge model 5 (CM5), and mulliken partial charges. The mulliken partial charge distribution of nirmatrelvir exhibits a poor correlation with the MK ESP charges in MP2, B3LYP, and M06L calculations respectively. The NPA, Hirshfeld, and CM5 partial charge scheme of nirmatrelvir indicate a reasonable correlation with MK ESP charge assignments in B3LYP and M06L calculations. The above correlations were not improved by the inclusion of implicit solvation model. The MK ESP and CM5 partial charges show a strong correlation between the results of MP2 and two DFT methods. The three optimized structures present a certain degree of differences from the crystal bioactive conformation of nirmatrelvir, suggesting the nirmatrelvir-enzyme complex is formed in the induced-fit model. The Reactivity of warhead electrophilic nitrile is justified by the relatively weaker strength of π bonds in the MP2 calculations. The nirmatrelvir hydrogen bond acceptors consistently show strong delocalization of lone pair electrons in three calculations, whereas hydrogen bond donors are found to have high polarization on the heavy nitrogen atoms in MP2 computations. This work helps to parametrize the force field of nirmatrelvir and improve accuracy of molecular docking and rational inhibitor design.

Keywords: Second order Møller–Plesset (MP2) perturbation theory, Nirmatrelvir, Electrostatic potential (ESP), NPA theory (NPA), and Mulliken

Introduction

The devastating COVID-19 pandemic stems from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Combined with vaccines, antiviral drugs present a pivotal role of medical efforts to attacking the worldwide disease resulted from COVID-19 [1]. One of the most attractive target proteins for COVID-19 drug is the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro, also named 3-Chymotrypsin like protease (3CLpro)). This cysteine protease mainly involves in the essential proteolysis at eleven Leu-Gln-Ser-Ala-Gly sites of polyproteins encoded by the SARS-C-V-2 viral genome [2,3], and the resultant smaller nonstructural polypeptides are critical for viral replication and encapsulation of SARS-CoV-2 [4]. The SARS -CoV-2 Mpro exists as a homodimer and each protomer monomer consists of three domains I, II, and III [5], [6], [7], [8]. The domain I and II feature six antiparallel beta sheets respectively and host the catalytic active site in cleft between the two domains, whereas the helical domain III account for the dimerization between the protomer monomers [9]. While the active cavity of Mpro is typically partitioned into four subsites, substrates named P1, P2, P3, and P4. Mpro active site presents a Cys145-His catalytic dyad, whereas the Mpro protease substrates feature the presence of a glutamine at P1 and hydrophobic residues at P2 of polyprotein substrate according the Schechter-Berger nomenclature [10]. The rational design of nirmatrelvir aimed at competitive binding to the P1 and P2 subsites [11]. For the side chain amide of glutamine can easily make cyclized linkage, the more stable cyclized pyrrolidine is used as the mimetic of glutamine. It is indicated that P3 and P4 make relatively smaller free energy contribution to the protein-ligan interaction in the QM/MM simulation [12]. Nirmatrelvir belongs to type of covalent peptidomimetic inhibitor drug for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro discovered by Pfizer. The SARS-CoV-2 main inhibitor nirmatrelvir or PF-07321332 has been developed to combat COVID-19 [11,13]. Nirmatrelvir maintained the potency against all the 14 naturally occuring main protease polymorphism [14]. The drug molecule exhibits excellent oral bioavailability, antiviral activity against pan-human coronavirus variants, high electivity, and in vivo safety. Understanding ligand-protein interaction may aid in optimization of drug candidates for fighting COVID-19 disease. The binding mode and affinity had been studied using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. Scoring functions serve as the major barriers for avoiding false screening in molecular docking, and accurate ligand partial charge are required for ligand desolvation and polar interaction in the scoring function parameters [21,22]. Ligand parametrization including atomic partial charges needs to be precisely illustrated in molecular dynamics simulation [22,23]. The machine learning approach for partial charge scheme is independent of structural conformation which is how ESP atomic partial charges are assigned [24]. The Martin et all performed benchmark six population analyses (Mulliken, NPA, AIM, CHELP, Merz-Kollman and RESP) for water molecule using variety of basis sets and four quantum mechanical models (Hartree-Fock, B3LYP, MP2, and QCISD), and indicated MK ESP charge scheme cannot describe charge distribution properly for the systems with large number of atoms buried in the molecular geometry [25]. Marenich et al found that the Hirshfeld or Charge Model 5 (CM5) population offered more appropriate descriptions of chemical properties for molecules with a significant amount of atoms encapsulated inside the molecular structures [26]. Accurate charge distribution for nirmatrelvir is vital for molecular docking and rational drug design, but high level MP2 calculations of nirmatrelvir was not done yet because of its size of 67 atoms. Both empirical and heuristic models were used to derive the general Amber Force Filed (GAFF) for organic molecules [27]. Semiempirical AM1 computation was performed to parametrize force field for nirmatrelvir in the work by Xiong et al. [18]. Ngo et al applied B3LYP/6-31G** calculation to prepare partial charges for nirmatrelvir in the MD and QM/MM simulation [28]. We carry out MP2/6-311+G* calculation of nirmatrelvir and NBO analysis is performed to evaluate the reactivity of warhead nitrile, hydrogen bond donor and acceptor group of nirmatrelvir. Results of this work may facilitate molecular docking and development of antiviral drugs for SARS CoV-2 virus.

Method

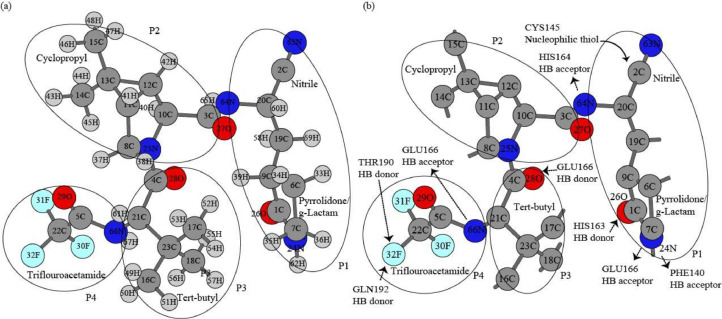

The experimental nirmatrelvir geometry was extracted from the Protein Data Bank (PDB code: 7U28). Hydrogen atoms were added to nirmatrelvir using Gaussview6 package. The structure was optimized and the electrostatic potential partial charge in Merz-Singh-Kollman (MK) scheme, natural population analysis (NPA) charge, mulliken partial charge, Hirshfeld, and extension of Hirshfeld or charge model 5 (CM5) partial charge were computed with Second Order Møller–Plesset (MP2) /6-311+G*, Density Functional Theory (DFT) M06L/6-311+G*, and DFT B3LYP/6-311+G* method implemented in Gaussiion-16 program [29]. NPA (NPA) analysis was also performed to calculate polarization coefficient, λ values for NPA hybrid NPA occupancies for the most polar nitrile bond [30]. The correlation analyses were made between partial charge scheme and chemistry models for 67 atoms of whole nirmatrelvir molecule. The detailed numerical differences were examined for a subset of 11 atoms (C2, N63, N24, H62, N64, H65, N66, H67, O26, O28, and F32) which are directly involved in the inhibitor-Mpro complex. The structure of nirmatrelvir was mapped out and all atoms labeled numerically in the pharmacophore model following Schechter-Berger system in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

a. Schechter-Berger scheme of nirmatrelvir with hydrogen in the pharmacophore model; b. Schechter-Berger scheme of nirmatrelvir for heavy atoms the pharmacophore model showing hydrogen bond donor and acceptor amino acids in the nirmatrelvir-Mpro lambda complex (PDB code: 7U28).

Results

Effect of different population analyses on the charge distribution

The correlations of NPA and mulliken partial charge with ESP partial charges are prepared for 67 atoms of the whole nirmatrelvir molecule calculated using MP2/6-311+G*, M06L/6-311+G*, and B3LYP/6-311+G* methods respectively in Fig. 2 . The partial charges are compared between two pairs of charge schemes for the major interacting atoms of nirmatrelvir-Mpro and the differences are listed in Tables 1 and 2 . The ESP atomic partial charges represent the common implementation of the electrostatic potential fitting strategy. The MK ESP, charge derived from electrostatic potential (CHELP) ESP, and charge derived from electrostatic potential gradient (CHELPG) ESP charges can describe accurately ESP surrounding molecular van der Waals surface defined by a given number of points. The NPA charges are computed under natural atomic orbitals (NPAs). Teixeira et al found that only NPA and atoms in molecules (AIM) can provide charges with correct signs for all systems studied [31]. Our results of MP2 simulation in Fig. 1a indicate that NPA partial charges exhibit a reasonable correlation with those of MK ESP scheme with a correlation coefficient R2 of 0.7562, but the very low correlation factor of 0.1455 implies that mulliken charges correlate poorly with MK ESP charges in MP2 calculation. There are 67 atoms in nirmatrelvir molecule, so DFT calculations of electronic properties are more affordable than that of MP2 method. Fig. 2b manifests the certain extent of correlations between NPA charges and MK ESP charge distributions in the DFT M06L computations with a correlation factor R2 of 0.7404, whereas the correlation coefficient R2 of 0.1338 indicates the irrelevance between the trends of mulliken charges and MK ESP population analysis. The standard DFT B3LYP model also yields a relatively larger correlation factor of 0.7425 suggesting higher degree of association between the patterns of NPA and MK ESP charges, and the smaller correlation coefficient R2 of 0.2465 showing a poor correlation between mulliken and MK ESP charge assignment of nirmatrelvir molecule. The inclusion of solvation model to M06L calculation seems cause not much influence the fact that the correlation factor R2 of 0.7416 still means somewhat correlation between NPA charge and MK ESP and the correlation coefficient R2 of 0.1715 reflects little correlation between mulliken and MK ESP charge scheme in the M06L method coupled with implicit water solvation, Overall, it is true that certain degree of correlations occur between NPA and MK ESP population analyses indicated with a correlation coefficient R2 around 0.7 in all MP2, M06L, B3LYP, and M06L couple to solvation model. On the other hand, there are no apparent correlations between mulliken and MK ESP charge distributions for all MP2, M06L, B3LYP, and M06L with solvation model.

Fig. 2.

Effects of different quantum mechanical methods and solvation model. a. Correlation between NPA and mulliken with MK ESP charge in MP2 Calculation; b. Correlation between NPA and mulliken with MK ESP charge in M06L Calculation; c. Correlation between NPA and mulliken with MK ESP charge in B3LYP Calculation; d. Correlation between NPA and mulliken with MK ESP charge in M06L calculation including solvation effect.

Table 1.

Comparison of the NPA partial charges with MK ESP partial charges calculated using MP2/6-311+G*.

| Atom | MP2 ESP q | MP2 NPA q | Delta q | Pharmacophore | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F32 | -0.2715 | -0.3800 | 0.1085 | P4 | HB acceptor |

| O28 | -0.6781 | -0.7728 | 0.0947 | P2 | HB acceptor |

| O26 | -0.6328 | -0.7224 | 0.0896 | P1 | HB acceptor |

| N24 | -0.6475 | -0.7185 | 0.0710 | P1 | HB donor |

| H65 | 0.4212 | 0.4014 | 0.0198 | P1 | HB donor |

| H62 | 0.3758 | 0.3938 | -0.0180 | P1 | HB donor |

| H67 | 0.3643 | 0.4263 | -0.0620 | P4 | HB donor |

| N63 | -0.4458 | -0.3642 | -0.0816 | P1 | Covalent |

| N66 | -0.8078 | -0.6930 | -0.1148 | P4 | HB donor |

| N64 | -0.8502 | -0.7017 | -0.1485 | P1 | HB donor |

| C2 | 0.1647 | 0.3321 | -0.1674 | P1 | Covalent |

Table 2.

Comparison of ESP partial charges q (a.u.) for the 11 heavy atoms of nirmatrelvir computed using M06L6-311+G* and B3LYP6-311+G* methods with those calculated with MP2/6-311+G*method.

| Atom | q MP2 | q M06L | q B3LYP | Δq (MP2-M06L) | % | Δq (MP2-B3LYP) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H62 | 0.3758 | 0.3493 | 0.3505 | 0.0264 | 7 | 0.0253 | 7 | |

| H67 | 0.3643 | 0.3381 | 0.3437 | 0.0262 | 7 | 0.0206 | 6 | |

| H65 | 0.4212 | 0.3966 | 0.3991 | 0.0246 | 6 | 0.0221 | 5 | |

| N63 | -0.4458 | -0.4477 | -0.4542 | 0.0019 | 0 | 0.0085 | -2 | |

| F32 | -0.2715 | -0.2177 | -0.2318 | -0.0538 | 20 | -0.0398 | 15 | |

| C2 | 0.1647 | 0.2318 | 0.2452 | -0.0672 | -41 | -0.0806 | -49 | |

| O26 | -0.6328 | -0.5450 | -0.5676 | -0.0877 | 14 | -0.0652 | 10 | |

| O28 | -0.6781 | -0.5892 | -0.6260 | -0.0888 | 13 | -0.0521 | 8 | |

| N24 | -0.6475 | -0.5442 | -0.5565 | -0.1033 | 16 | -0.0910 | 14 | |

| N66 | -0.8078 | -0.7041 | -0.7135 | -0.1037 | 13 | -0.0942 | 12 | |

| N64 | -0.8502 | -0.7297 | -0.7430 | -0.1205 | 14 | -0.1072 | 13 | |

Particularly, the N25 on the P2 has the largest difference of 0.3905 a.u between MK ESP and NPA partial charge which are -0.2085 a.u. and -0.5990 a.u. respectively. The difference 0f -0.0060 a.u. between the two charge schemes represent the smallest numeric values for C15 of P2 among the 11 major interacting atoms of nirmatrelvir, the partial charges being -0.4801 a.u and -0.4741 a.u. mulliken partial charge can be quickly computed directly using the density matrix for electronic wavefunction, but it can hardly reproduce the dipole moment and ESP partial charge. Since the density matrix or the linear combination of the atomic orbitals are applied for charge calculation, the resultant partial charges are very sensitive to the size of basis sets. The most accurate mulliken can be obtained by using a complete basis set. Alternatively, accurate partial charges can be generated using the density derived from electrostatic potential or natural population analysis. The mulliken partial charge scheme may significantly underestimate the ionicity of strong electrolytes. Nirmatrelvir suppresses SARS-CoV-2 Mpro by a reversible covalent linkage to the nucleophilic cysteine thiolate residue using C2 of electrophilic nitrile warhead [32]. The MK ESP scheme ad NPA method assign 0.1647 a.u. and 0.3321 a.u. for C2 respectively, implying a difference -0.1647 a.u. between the two population analysis methods.

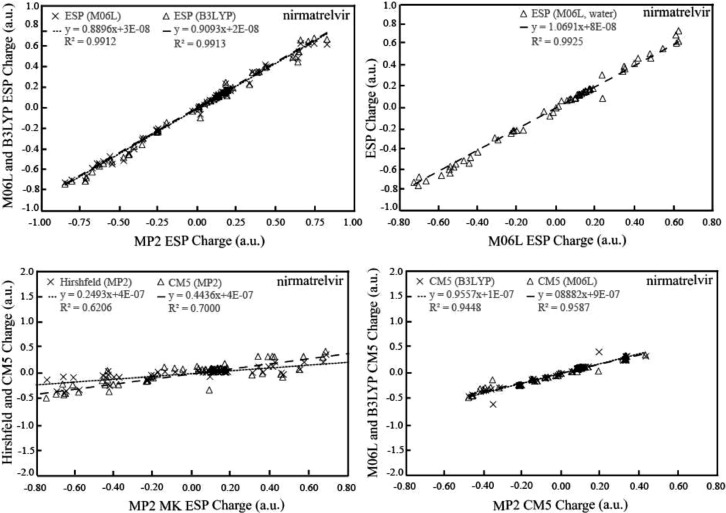

Impact of uses of quantum mechanical methods on MK ESP and CM5 charge distributions

The correlation curves between the charges (including MK ESP and CM5) of MP2 and two DFT methods were prepared in Fig. 3 . The MK ESP charges were compared in Table 2 for the 11 atoms directly involved enzyme-inhibitor interactions such as the warhead electrophile nitrile, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors. The correlation curves between bond angles of MP2 and other geometries were described in Fig. 4 . The major dihedral angles were listed in Table 3 . Our results show that the MKESP charges correlate very well between MP2 and two DFT methods M06L and B3LYP, the correlation factor R2 values being 0.9912 and 0.9913 respectively. This is also the case for the comparison between MK ESP charge between two DFT models M06L and B3LYP with correlation coefficient R2 of 0.9925. Overall, the MK ESP partial charge distributions are very closely related.

Fig. 3.

Effects of different quantum mechanical methods on the MK ESP charge distribution. a. Correlation between MK ESP charges of DFT and those of MP2 Calculation; b. Correlation between MK ESP charges between DFT methods M06L and B3LYP Calculation; c. Correlation between the partial charges MK ESP and CM5 of MP2 Calculation; d. Correlation between CM5 charges between the two DFT methods M06L and B3LYP Calculations.

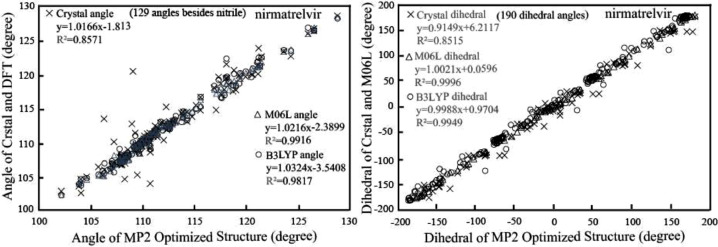

Fig. 4.

Effects of different quantum mechanical methods on geometry parameters. a. Correlations of bond angles between the MP2 structure and other geometries; b. Correlation of dihedral angles between the MP2 structure and other geometries.

Table 3.

Comparison of dihedral angles among crystal and optimized structures.

| Dihedral | Crystal (degree) | MP2 (degree) | M06L (degree) | B3LYP (degree) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6-C7-N24-C1 | -15.08 | -23.38 | -25.05 | -25.54 |

| C9-C1-N24-C7 | -6.60 | 6.89 | 4.62 | 3.90 |

| C2-C20-N64-C3 | -125.91 | -139.53 | -137.29 | -119.04 |

| N25-C4-C21-N66 | 121.38 | 122.98 | 121.44 | 129.35 |

| N66-C5-C22-F32 | 83.72 | 106.28 | 111.80 | 116.46 |

The Hirshfeld and its extension CM5 partial charges are indicated to be able to reflect properly the experimental chemical properties of compounds with a large amount of atoms buried in their overall geometries [26]. Fig. 3c shows the correlation R2 value of 0.6206 between the Hirshfeld and MK ESP partial charge of MP2 calculations, and the correlation parameter R2 is 0.7000 for the correlation between CM5 and MK ESP charge distribution from MP2 computation. These results suggest that moderate correlations occur between the Hirshfeld systems and MK ESP charge scheme. Fig. 3d indicates a square of correlation coefficient R2 of 0.9448 for the correlation CM5 charges between B3LYP and MP2 computations, whereas the similar extent of correlation with a R2 of 0.9587 is displayed for the CM5 charges between M06L and MP2 calculations. The above high degrees of correlations propose that the CM5 charge distributions are not heavily method dependent.

Even if strong correlations occur between each charge distribution pairs of MP2, M06L, and B3LYP calculation results, the differences between the individual MK ESP charges of MP2 and DFT methods cannot be ignored completely. The comparison made in Table 2 indicates the N64 in the vicinity of nitrile in nirmatrelvir highlights the most significantly different of MK ESP charges between MP2 and DFT calculations, which are -0.8502, -0.7297, -0.7430 a.u. respectively for MP2, M06L, and B3LYP calculations. The differences between MP2 charge and two DFT results are 0.1205 a.u. (14%) between MP2 and M06L, 0.1072 a.u. (13%) between MP2 and B3LYP calculations. The MK ESP partial charges for N63 are essentially the same in all MP2, M06L, and B3LYP calculations. The differences between MK ESP charges of C2 between MP2 and the two DFT calculations presents the relatively high percentage -41% between MP2 and M06L calculations and -49% between MP2 and B3LYP calculations, but the numerical values 0.1647 a.u., 0.2318 a.u., and 0.2452 a.u. seem acceptable for MP2, M06L, and B3LYP calculations.

The MK ESP atomic partial charges inherently conformation dependent [24]. The conformation parameter bond angles and dihedral angles are examined for the crystal and optimized structures. The correlation curves in Fig. 4 indicate there are relatively strong correlations occurring between bond parameters of MP2 and DFT optimized structures. The correlation factor is 0.9916 for the correlation curves between the bond angles of M06L and MP2 calculations, and the B3LYP calculated bond angles correlate to those from MP2 computation with a correlation coefficient 0.9817. Similarly, the comparison between dihedral angles of M06L and MP2 calculations presents a correlation factor of 0.9996, whereas the B3LYP calculated dihedral angles correlate to those of MP2 simulations. In contrast, conformal parameters of crystal structure of nirmatrelvir differ slightly significantly from those MP2 optimized geometry. The bond angles of crystal structure nirmatrelvir provide a lower correlation factor of 0.8571 in the correlation curve with those structural parameters form MP2 calculations, and dihedral angles of nirmatrelvir crystal structure correlate to the corresponding structural parameter of MP2 minimized geometry with a correlation factor of 0.8515. In other words, the nirmatrelvir molecule undergoes a certain degree of conformal transformation upon binding to Mpro. On the other hand, Mpro is characteristically evolved into having an uncommon catalytic Cys145. Being different from most chymotrypsin-like enzymes, Serine, and Cysteine hydrolases, Mpro holds a Cys-His dyad but not the typical Ser-His-Asp or Cys-His-Glu triad [33]. More importantly, the unique Cys-His dyad is buried in in the catalytic active cavity in the cleft between domain I and II [34], which suggests the Cys-His dyad should need to switch to form covalent bond with nitrile of nirmatrelvir. Thus, our analyses propose the nirmatrelvir-Mpro binding may feature the induced fit model by Koshland et al.

The pyrrolidone is designed to offers rigidity rather than flexibility of preferred glutamine by Mpro, leading to less conformational changes when forming Mpro-substrate complex [35]. Our results in Table 3 show two major dihedrals C6-C7-N24-C1 and C9-C-1-N24-C7 of the pyrrolidone moiety do not fluctuate significantly in all the four structures. The C6-C7-N24-C1 for MP2, M06L, and B3LYP optimized structure are 23.38°, 25.05 °, and 25.54° respectively, being roughly 10° larger than the 15.08° of the complex crystal structure. This is also true for the other dihedral C9-C1-N24-C7 of pyrrolidone which are 6.89°, 4.62°, 3.9°, the MP2, M06L, B3LYP simulated geometries respectively by themselves and -6.60° for the MP2, M06L, B3LYP simulated geometries, and inhibitor-enzyme complex crystal by themselves. This proposes the minor adjustments of nirmatrelvir conformational plasticity upon binding to active cavity of Mpro featuring the induced fit model. The C2-C20-N64-C3 dihedral angles are -125.91°, -139.53°, 137.29°, and -119.04° respectively for crystal, MP2, M06L, and B3LYP minimized structures, and the minor difference between crystal and optimized structure reflects the effect of covalent bond formation between nitrile of nirmatrelvir and CYS145 of Mpro. The N25-C4-C21-N66 dihedral angles share the closest numerical values 121.38° to 129.35°, showing the relative orientation of P4 trifluoroacetamide and P3 tert-butyl stays the same because of steric hindrance. The formation of hydrogen bonds between F32 and THR190 and GLN192 lead the biggest change of around 30° for dihedral angle N66-C5-C22-F32 between the 83.72° of complex crystal structure and 106.28° to 111.80° for enzyme free optimized geometries.

NPA analysis of reactivity of nirmatrelvir

The NBO polarization coefficients, hybridization λ, bond energies levels, and electron lone pair delocalization were calculated and listed for the atoms directly involved enzyme-inhibitor interactions such as the warhead electrophile nitrile, hydrogen bond donor and acceptors in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 . It is established that nirmatrelvir P1 can make a covalent bond with C145, part of the catalytic dyad CYS145 and HIS164 [12]. There are two proton transfers occurring in the mechanism. The first proton migration from C145 to H164 provides a nucleophile negatively charged C145 thiol, which attacks the electrophile nitrile carbon of nirmatrelvir to form a S-C thioimidate. The second proton transfer illustrates the water-aided proton migration from H164 to nitrogen atom N63 of the nitrile group on nirmatrelvir [36]. Our results in Table 3 suggest that the relatively high energies -0.47556 and -0.47536 Hartrees of two pi bonds account for the reactivity of electrophilic warhead nitriles. In contrast, the σ bond of the nitrile is found to be very stable with a very low energy level of -1.34464 Hartrees.

Table 4.

NPA bond polarization coefficients, λ of hybridization spλ, and bond energies using MP2/6-311+G*.

| C2-N63 (Hartrees) | C2 cA | Hybrid | N63 cA | Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ bond (-1.34464) | 0.6539 | sp1.10 | 0.7566 | sp1.13 |

| π bond (-0.47556) | 0.6601 | p1.00 | 0.7512 | p1.00 |

| π bond (-0.47536) | 0.6688 | p1.00 | 0.7434 | p1.00 |

Table 5.

NPA bond polarization coefficient cA, λ of hybridization spλ, and bond energies of HB acceptors using MP2/6-311+G*.

| HB acceptor (Hartrees) | cA | Hybrid | cA | Hybrid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N24-H62 (-0.87399) | 0.8377 | sp2.60 | 0.5461 | s | |

| N64-H65 (-0.88649) | 0.8386 | sp2.79 | 0.5448 | s | |

| N66-H67 (-0.90027) | 0.8460 | sp2.78 | 0.5331 | s |

Table 6.

Delocalization of lone pairs for hydrogen bond acceptors O26 and F32 with unoccupied non-Lewis antibonding and Rydberg orbitals calculated using MP2/6-311+G*.

| Lone pair (Hartree) | Antibonding (BD*) or Rydberg (RY*) | E(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| O26-LP113 (-0.92961) | RY* C1-133 | 22.48 |

| BD* C1-C9 | 2.75 | |

| O26-LP114 (-0.41585) | BD* C1-N24 | 33.05 |

| BD* C1-C9 | 25.12 | |

| O28-LP117 (-0.96411) | RY* C1-184 | 21.27 |

| BD* C4-C21 | 2.28 | |

| O28-LP118 (-0.45250) | BD* C4-C21 | 22.70 |

| BD* C4-N24 | 27.59 | |

| F32-LP127 (-1.46603) | RY* C22-491 | 6.88 |

| RY* C22-492 | 2.29 | |

| F32-LP128 (-0.69947) | BD* C5-C22 | 7.34 |

| BD* C22-F30 | 5.24 | |

| F32-LP129 (-0.69627) | BD* C22-F30 | 13.17 |

| BD* C22-F31 | 12.81 |

In addition to most reactive nitrile, nirmatrelvir P1 also contributes two hydrogen bond acceptors N24 and N64, and one hydrogen bond acceptor O26. An extensive hydrophobic interaction occurs between nirmatrelvir P2 cyclopropyl moiety and backbone of H164. The hydrophobic P3 tert-butyl makes partial interaction with Mpro and has solvent exposure. The P4 trifluoro-acetyl moiety also evolves to the S4 pocket and makes hydrogen bonds with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of E166 and T190 [37]. Table 4 shows that the polarization coefficients for three hydrogen bond donors are 0.8377, 0.8386, and 0.8460 respectively for N24, N64, and N66. The squares of the composition coefficients 0.83992, 0.83862, and 0.86402 gave the corresponding localization 70.18%, 70.32%, and 70.58% on N24, N64, and N66 respectively. The high polarity of N24-H61, N64-H65, and N66-H67 manifests the strong tendency for forming hydrogen bonds between them and two amino acids HIS 164 and GLU166.

Three atoms O26, O28, and F32 of nirmatrelvir make hydrogen bonds as hydrogen bond donors with HIS163, GLU166, GLN192, and THR192 respectively. There are two lone pairs for O26 and O28 besides the double bond ketone, and F32 has three lone pairs of electrons in addition to the F32-C22 bond. The 2nd-order perturbation theory analysis of Fock matrix was performed to interactions between occupied Lewis-type NBOs and unoccupied non-Lewis NBOs. These interactions result in occupancy transfer from the of the exact Lewis localized NBOs to the non-Lewis orbitals and account for the delocalization corrections to zeroth-order natural structure in NBO basis. The NBO theory does not have formalisms illustrating resonance structures, but the delocalization concept helps to highlight the minor deviations form exact Lewis structures [38]. The delocalization of lone pairs likely implies strong tendencies to form hydrogen bond in the enzyme-inhibitor interactions. The two strongest interactions are listed for the lone electron pairs for the two hydrogen bond acceptors O26, O28, and F32 in Table 5. Our results in Table 5 show the lone pair LP113 (at energy level of -0.92961 Hartrees) can interact with the non-Lewis Rydberg orbital RY* C1-133 and antibonding orbital C1-C9 with the interaction forces of 22.48 and 2.75 kcal/mol respectively, and the other lone pair LP114 at energy level of -0.41858 Hartrees shows slightly stronger interactions 33.05 and 25.12 kcal/mol respectively with antibonding orbitals C1-C9 and C1-N24. Since the two lone electron pairs of O26 can transfer partially into above non-Lewis Rydberg and antibonding orbitals in the isolated nirmatrelvir molecule, it is reasonable to justify the formation of hydrogen bond by O26 with HIS163 in the enzyme-inhibitor crystal structure. Similar delocalization occurs for the lone electrons LP117 (-0.96411 Hartrees) and LP118 (0.45250 Hartrees) of O28. It is likely that LP118 (-0.45250 Hartrees) can make hydrogen bond with GLU166 since it shows strong interactions of 22.70 kcal/mol and 27.59 kcal/mol with C4-C21 and C4-N24 antibonding orbitals respectively. On the other hand, the slightly lower interaction energies associated with the delocalization of three lone electron pairs of F32 can explain the existence of hydrogen bonds between F32 and two amino acids THR190 and GLN192 in the enzyme-substrate crystal structure.

Conclusion

Our MP2, M06L, B3LYP calculations confirm that low degrees of correlations occur between the mulliken partial charge distribution and MK ESP charges in in all three chemistry models, but there are certain extents of correlations between NPA partial charge and MK ESP charge in all computations. Inclusion of solvation correlations show on effects on the above trends. Similar moderate correlations also exist between the Hirshfeld systems and MK ESP charge populations. The MK ESP and CM5 partial charges consistently correlate to each other between MP2 and two DFT methods. The three optimized structures exhibit high similarities, and they deviate slightly from the crystal active conformation of nirmatrelvir. The high energy level π bond highlights the high reactivity of the warhead electrophilic nitrile in MP2 calculation results. The strong polarity of hydrogen bond donors nirmatrelvir indicates their strong tendency to form hydrogen bonds in the nirmatrelvir-Mpro complex. The role of hydrogen bond acceptors is supported by the significant lone pair delocalization in MP2 NBO analysis. These results may aid in parametrization of nirmatrelvir in molecular docking and rational drug development.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuemin Liu: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rulong Ma: . Huajun Fan: . Bruce R. Johnson: . James M. Briggs: .

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135871.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Kozlov M. Nature. (England. 2022;601:496. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-00112-8. in. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu F., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pillaiyar T., Manickam M., Namasivayam V., Hayashi Y., Jung S.H. An Overview of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL Protease Inhibitors: Peptidomimetics and Small Molecule Chemotherapy. J Med Chem. 2016;59:6595–6628. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee T.W., et al. Crystal structures of the main peptidase from the SARS coronavirus inhibited by a substrate-like aza-peptide epoxide. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:1137–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang H., et al. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13190–13195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L., et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin Z., et al. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science. 2003;300:1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rut W., et al. SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors and activity-based probes for patient-sample imaging. Nat Chem Biol. 2021;17:222–228. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-00689-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owen D.R., et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science. 2021;374:1586–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.abl4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos-Guzmán C.A., Ruiz-Pernía J.J., Tuñón I. Computational simulations on the binding and reactivity of a nitrile inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Chem Commun (Camb) 2021;57:9096–9099. doi: 10.1039/d1cc03953a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Couzin-Frankel J. Antiviral pills could change pandemic's course. Science. 2021;374:799–800. doi: 10.1126/science.acx9605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.G. D. Noske et al., Structural basis of nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir activity against naturally occurring polymorphisms of the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Ahmad B., Batool M., Ain Q.U., Kim M.S., Choi S. Exploring the Binding Mechanism of PF-07321332 SARS-CoV-2 Protease Inhibitor through Molecular Dynamics and Binding Free Energy Simulations. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22179124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang J., et al. Site mapping and small molecule blind docking reveal a possible target site on the SARS-CoV-2 main protease dimer interface. Comput Biol Chem. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2020.107372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu W.S., et al. Screening potential FDA-approved inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 major protease 3CL(pro) through high-throughput virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:6258–6272. doi: 10.18632/aging.202703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong D., Zhao X., Luo S., Zhang J.Z.H., Duan L. Molecular Mechanism of the Non-Covalent Orally Targeted SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitor S-217622 and Computational Assessment of Its Effectiveness against Mainstream Variants. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2022;13:8893–8901. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c02428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyndall J.D.A. S-217622, a 3CL Protease Inhibitor and Clinical Candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2022;65:6496–6498. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayek-Orduz Y., et al. Novel covalent and non-covalent complex-based pharmacophore models of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) elucidated by microsecond MD simulations. Scientific Reports. 2022;12:14030. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenk R., Vetter S.W., Boyce S.E., Goodin D.B., Shoichet B.K. Probing molecular docking in a charged model binding site. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:1449–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho A.E., Guallar V., Berne B.J., Friesner R. Importance of accurate charges in molecular docking: quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) approach. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:915–931. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodda L.S., Cabeza de Vaca I., Tirado-Rives J., Jorgensen W.L. LigParGen web server: an automatic OPLS-AA parameter generator for organic ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W331–w336. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bleiziffer P., Schaller K., Riniker S. Machine Learning of Partial Charges Derived from High-Quality Quantum-Mechanical Calculations. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2018;58:579–590. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin F., Zipse H. Charge distribution in the water molecule—A comparison of methods. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2005;26:97–105. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marenich A.V., Jerome S.V., Cramer C.J., Truhlar D.G. Charge Model 5: An Extension of Hirshfeld Population Analysis for the Accurate Description of Molecular Interactions in Gaseous and Condensed Phases. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2012;8:527–541. doi: 10.1021/ct200866d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J., Wolf R.M., Caldwell J.W., Kollman P.A., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ngo S.T., Nguyen T.H., Tung N.T., Mai B.K. Insights into the binding and covalent inhibition mechanism of PF-07321332 to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. RSC Advances. 2022;12:3729–3737. doi: 10.1039/d1ra08752e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.M. J. Frisch et al. (Wallingford, CT, 2016).

- 30.Foster J.P., Weinhold F. Natural hybrid orbitals. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1980;102:7211–7218. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teixeira F., Mosquera R., Melo A., Freire C., Cordeiro M.N.D.S. Charge distribution in Mn(salen) complexes. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 2014;114:525–533. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brewitz L., et al. Alkyne Derivatives of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors Including Nirmatrelvir Inhibit by Reacting Covalently with the Nucleophilic Cysteine. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2023;66:2663–2680. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorbalenya A.E., Snijder E.J. Viral cysteine proteinases. Perspect Drug Discov Des. 1996;6:64–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02174046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kneller D.W., et al. Structural plasticity of SARS-CoV-2 3CL Mpro active site cavity revealed by room temperature X-ray crystallography. Nature Communications. 2020;11:3202. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16954-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan J., et al. 3C protease of enterovirus 68: structure-based design of Michael acceptor inhibitors and their broad-spectrum antiviral effects against picornaviruses. J Virol. 2013;87:4339–4351. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01123-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pavan M., Bolcato G., Bassani D., Sturlese M., Moro S. Supervised Molecular Dynamics (SuMD) Insights into the mechanism of action of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor PF-07321332. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2021;36:1646–1650. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2021.1954919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joyce R.P., Hu V.W., Wang J. The history, mechanism, and perspectives of nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332): an orally bioavailable main protease inhibitor used in combination with ritonavir to reduce COVID-19-related hospitalizations. Med Chem Res. 2022;31:1637–1646. doi: 10.1007/s00044-022-02951-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carpenter J.E., Weinhold F. Analysis of the geometry of the hydroxymethyl radical by the “different hybrids for different spins” natural bond orbital procedure. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM. 1988;169:41–62. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.