Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare pulmonary vascular disorder, wherein mean systemic arterial pressure (mPAP) becomes abnormally high because of aberrant changes in various proliferative and inflammatory signaling pathways of pulmonary arterial cells. Currently used anti-PAH drugs chiefly target the vasodilatory and vasoconstrictive pathways. However, an imbalance between bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II (BMPRII) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) pathways is also implicated in PAH predisposition and pathogenesis. Compared to currently used PAH drugs, various biologics have shown promise as PAH therapeutics that elicit their therapeutic actions akin to endogenous proteins. Biologics that have thus far been explored as PAH therapeutics include monoclonal antibodies, recombinant proteins, engineered cells, and nucleic acids. Because of their similarity with naturally occurring proteins and high binding affinity, biologics are more potent and effective and produce fewer side effects when compared with small molecule drugs. However, biologics also suffer from the limitations of producing immunogenic adverse effects. This review describes various emerging and promising biologics targeting the proliferative/apoptotic and vasodilatory pathways involved in PAH pathogenesis. Here, we have discussed sotatercept, a TGF-β ligand trap, which is reported to reverse vascular remodeling and reduce PVR with an improved 6-minute walk distance (6-MWDT). We also elaborated on other biologics including BMP9 ligand and anti-gremlin1 antibody, anti-OPG antibody, and getagozumab monoclonal antibody and cell-based therapies. Overall, recent literature suggests that biologics hold excellent promise as a safe and effective alternative to currently used PAH therapeutics.

Keywords: Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), biologics, monoclonal antibody, ligand trap, sotatercept, BMPRII, TGF-β, activin, GDF

Introduction

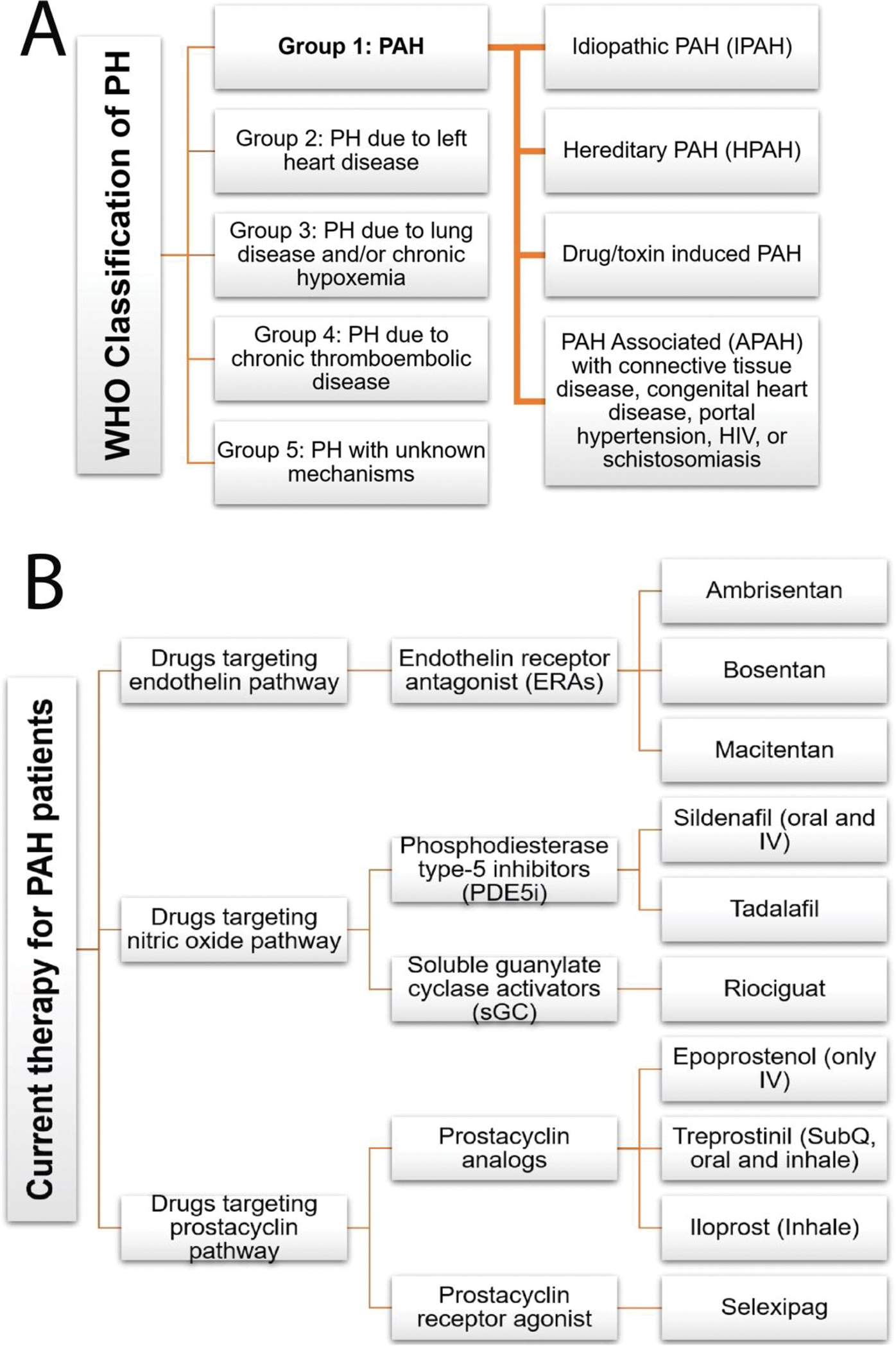

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a disorder of varying etiology, which may develop from coexisting cardiopulmonary diseases such as left-sided heart disease, thromboembolic pulmonary obstruction, lung disease, or vascular remodeling and eventual malfunction of the pulmonary vascular bed. World Health Organization categorized pulmonary hypertensive diseases into five groups, called WHO Groups (Figure 1A). WHO Group 1 disease is called pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), which results from endothelial dysfunction of pulmonary arteries or arterioles. The other 4 groups are called pulmonary hypertension, termed PH only [1].

Figure 1:

(A) Clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. (B) FDA approved small molecule drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension.

PAH (WHO Group 1 PH) is characterized by an increase in the mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) to ≥25 mmHg at rest [2]. In PAH, elevated blood pressure usually stems from reduction of pulmonary arterial lumen diameter due to endothelial dysfunction. The endothelial dysfunction involves complex vascular remodeling, including a combination of pulmonary blood vessel constrictive and hyperproliferative states, and may be triggered by multiple factors such as genetic predispositions, oxidative stress, hypoxia, toxin, aberrant immunological response, or sex hormone imbalance [3,4]. Thus, PAH is categorized into various subtypes: idiopathic (IPAH), familial (hereditary; HPAH), drug-induced PAH, and PAH associated with connective tissue disease. In PAH, all three layers of the vascular wall undergo proliferation, adversely affecting the vascular tone, elasticity, lumen diameter, and endothelial cell function and thus causing an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and mPAP. Numerous signaling pathways are dysregulated in PAH, leading to hyperproliferation of the vessel wall, development of plexiform lesions, and vascular injury. Major signaling pathways that are involved in PAH include cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation [5,6]. Because of the narrowing pulmonary arteries, the heart must work hard to move blood through the pulmonary artery, which causes compensatory right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH). If left untreated, the condition progresses to decompensatory heart failure and death. At the initial stage of this disease, the patient usually does not experience any symptoms, perhaps due to higher capacitance of the pulmonary circulation and lower arterial pressure than the systemic circulation. When the vascular remodeling continues to deteriorate, clinical symptoms are manifested due to decreased cardiac output. Thus, the symptoms of PAH are rather ambiguous that include shortness of breath, fatigue, and syncope with exertion, which makes diagnosis of PAH challenging.

Most FDA-approved PAH-specific therapeutics are small molecule drug that targets pulmonary vasoconstrictory and vasodilatory signaling pathways including prostacyclin analogs, endothelin receptor antagonists, nitric oxide (NO)-cGMP (cyclic guanosine monophosphate) enhancers, or calcium channel blockers (Figure 1B). The endothelial cells are the primary source of endogenous prostacyclin and prostaglandin that produce antithrombic and vasodilatory effects. These cells show reduced secretion of endogenous prostacyclin and prostaglandin in severe type of pulmonary hypertension and thus use of various synthetic prostacyclin analogs is the mainstay for the treatment of PAH. However, these agents have a relatively short half-life that requires continuous intravenous injections or multiple dosing a day. Moreover, these drugs reduce systemic blood pressure, a major side effect of currently used vasodilator-based PAH drugs [7]. Nitric Oxide (NO) is also an important endogenous signaling molecule that regulates vascular tone and maintains pulmonary circulation. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) produces and releases NO from endothelial cells. NO activates soluble guanylate cyclase and produces cGMP. The cGMP second messenger activates protein kinase G, which relaxes vascular smooth muscle. Phosphodiesterase enzyme-5 (PDE-5) breaks this cGMP and terminates the NO-mediated vasorelaxation. PDE-5 is specific for cGMP and present in the lung vascular smooth muscle cells. PAH pathology impairs the balance of NO production and upregulates PDE-5 activity. Thus, PDE-5 inhibitors are now available for the treatment of PAH. The effect of direct exogenous NO administration is transient and requires continuous inhalation, which often causes formation of methemoglobin [8,9].

Current treatment algorithms for newly diagnosed IPAH suggest upfront combination oral therapy. The guideline evolved from the AMBITION clinical trial data that suggest that tadalafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, and ambrisentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, improve exercise tolerance and slow down disease progression [10–12]. However, the AMBITION study with combination therapy did not show the survival benefits over monotherapy. An analysis of COMPERA registry data of European patients from 2010 –2019 showed that most patients still receive monotherapy, and the improvement in 3-year survival rate is not statistically significant [13]. The TRITON study’s results did not find any significant difference between the efficacy of triple combination therapy (oral prostacyclin agonist-selexipag, macitentan, and tadalafil) over dual combination therapy [14]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control clinical trial showed that combination therapy reduced clinical worsening and mortality. Still, there are conflicting reports regarding the benefits of various treatment approaches [15]. The pulmonary arterial lesions in connective tissue disease-associated PAH (CTD-PAH such as scleroderma, lupus, and systemic sclerosis) are virtually indistinguishable from those in IPAH. The CTD-PAH patients are thus treated with the same algorithm as that for IPAH. Moreover, due to additional comorbidities, CTD-PAH patients often received immunosuppressants as adjunctive therapy [16].

Many molecular signaling pathways largely remain unexplored with small-molecule drugs. Even with combination therapies, patients may remain unresponsive to therapy, show poor prognosis, suffer from major side effects, and ultimately, they are left with no treatment options [17]. As such, there is a need for new and more effective pharmacologic agents targeting proliferative, apoptotic, and immunomodulatory pathways and thus reestablish the homeostasis between cell proliferation and apoptosis and reverse pulmonary vascular remodeling.

Biologics have emerged as a new hope for the cure of many diseases including PAH. Biologics encompasses a diverse material of biological origins such as cells, and cell extracts; proteins, such as monoclonal antibodies, fusion proteins, recombinant proteins, growth factors, enzymes, peptides, miRNA, and siRNA. Therapeutically, biologics offer several benefits over small molecule drugs such as precision and specificity in targeting, higher binding affinity, and long circulation half-life. These benefits are translated into more effective therapy with reduced off-target effects, less frequent dosing, and improved patient compliance. However, biologics may also cause undesirable immunological reactions in some patients [18–20].

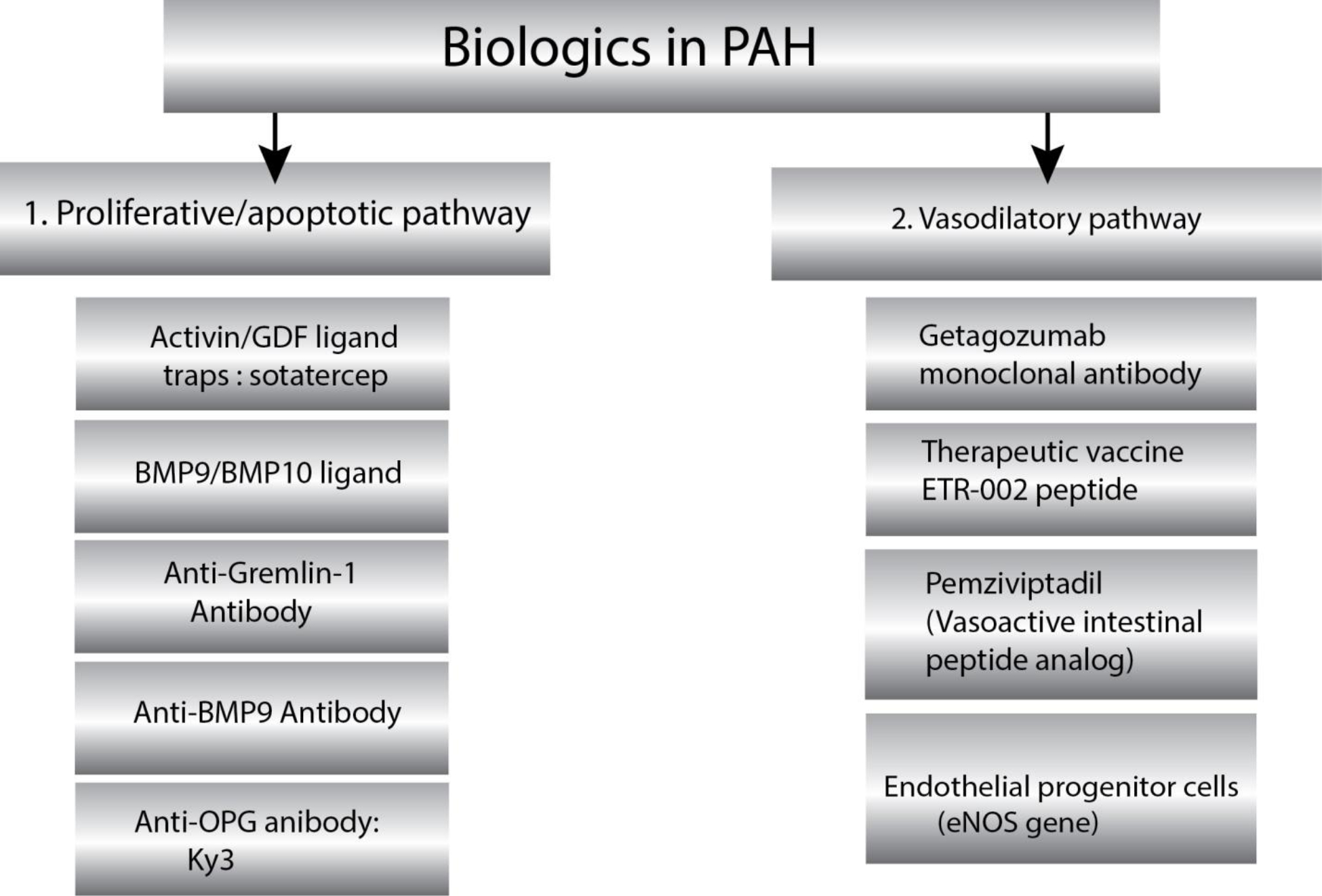

In this review, we have discussed the rationale and provided evidence in support of novel investigational biological drugs that have shown promise in animal models and preliminary human studies. Based on the therapeutic target, we have divided biologics that are explored for PAH into two major groups: (i) biologics targeting proliferative/apoptotic pathway, and (ii) biologics targeting vasodilatory pathway (Figure 2A). We further categorized emerging biologics into three groups based on their timeline of translational feasibility: (i) most promising, (ii) pipeline and (iii) hypothetical (Figure 2B). We also summarized the pharmacology of PAH biologics and their clinical trial status in Table 1.

Figure 2:

(A) Novel biologics targeting two dominant pathways implicated in pulmonary arterial hypertension. PAH pathophysiology involves multifactorial etiology that causes maladaptive pulmonary vascular remodeling and vasoconstriction. Small molecule drugs currently target only vasoconstricting pathways, which relieve symptoms. The underlying dysregulated immune modulation, vascular proliferation, and reduced apoptosis remained untargeted. Emerging biologics targeting two major PAH pathophysiologic pathways could improve pulmonary hemodynamics and ameliorates right ventricular hypertrophy.

Figure 2:

(B) Classification of emerging biologics based on preclinical and clinical studies.

Table 1:

Summary of Emerging Biologics for PAH (WHO Group 1 PH)

| Biologics | Mechanism of Action | Pharmacological effects | Side Effects | Clinical trial status | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sotatercept | Works as an activin/GDF ligand trap to reduce Smad2/3 growth promoting signaling | Inhibits proliferation of PASMCs and ECs; reduces PVR in preclinical and clinical studies. | Leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia. | Phase 2 and phase 3 | 35,40,41,42,51 |

| BMP 9 ligand | Selectively binds to BMPR II/ALK1 receptor complex and upregulates BMPR2 expression. | Improves pulmonary hemodynamics; reduces pulmonary arterial pressure and right ventricle mass in PAH animal model. | Osteogenicity through tissue calcification. | N/A | 59,60,61 |

| Anti-gremlin 1 | Inhibits gremlin-1, restores BMPII activity and upregulates Smad 1/5/8 signaling mostly in PAECs. | Ameliorates remodeling of pulmonary vasculature and right ventricle hypertrophy in preclinical models | No known side effects | N/A | 62,63 |

| Anti-osteoprotegerin (OPG) antibody | By inhibiting to OPG-Fas, anti-OPG antibody downregulates intracellular kinase signaling (phosphorylation of ERK1/2, CDK4/5) and thus inhibits cellular survival, migration, and proliferation. | Arrest proliferation, migration, and inflammation in animal models of PAH. | No known side effects. | N/A | 76,77 |

| Getagozumab monoclonal antibody | Selectively antagonizes human ETA with a high binding affinity and thus prevent pulmonary vasoconstriction and proliferation. | Reduces mPAP, RVSP, pulmonary arterial wall thickness and RVH in preclinical studies. | No known side effects | Phase 1b | 79 |

| Therapeutic vaccine (ETR-002 peptide) | ETR-002 is a ten amino acids peptide based on the ECL2 sequence of ETA, which generates anti–ETR-002 antibody in PAH animal model. | Reduces RVSP, ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis in PAH animal models. | No known side effects. | N/A | 80,81,82 |

| VIP analog (Pemziviptadil) | Selectively binds VPAC2 receptor to regulate vascular tone. | Reduces mean pulmonary arterial pressure, total pulmonary resistance and improved the 6-MWDT in a Phase 1 pilot study. | No significant side effects. | Phase 1 | 94,95 |

| EPC based eNOS gene therapy | Cell-based introduction of eNOS gene (gene therapy) produces target protein in vivo. | Decreases pulmonary resistance, improves functional class and 6-MWDT in clinical trials. | No known side effects. | Phase 1 | 96,97,98 |

TGF-β/BMP proliferative/apoptotic signaling pathway in PAH

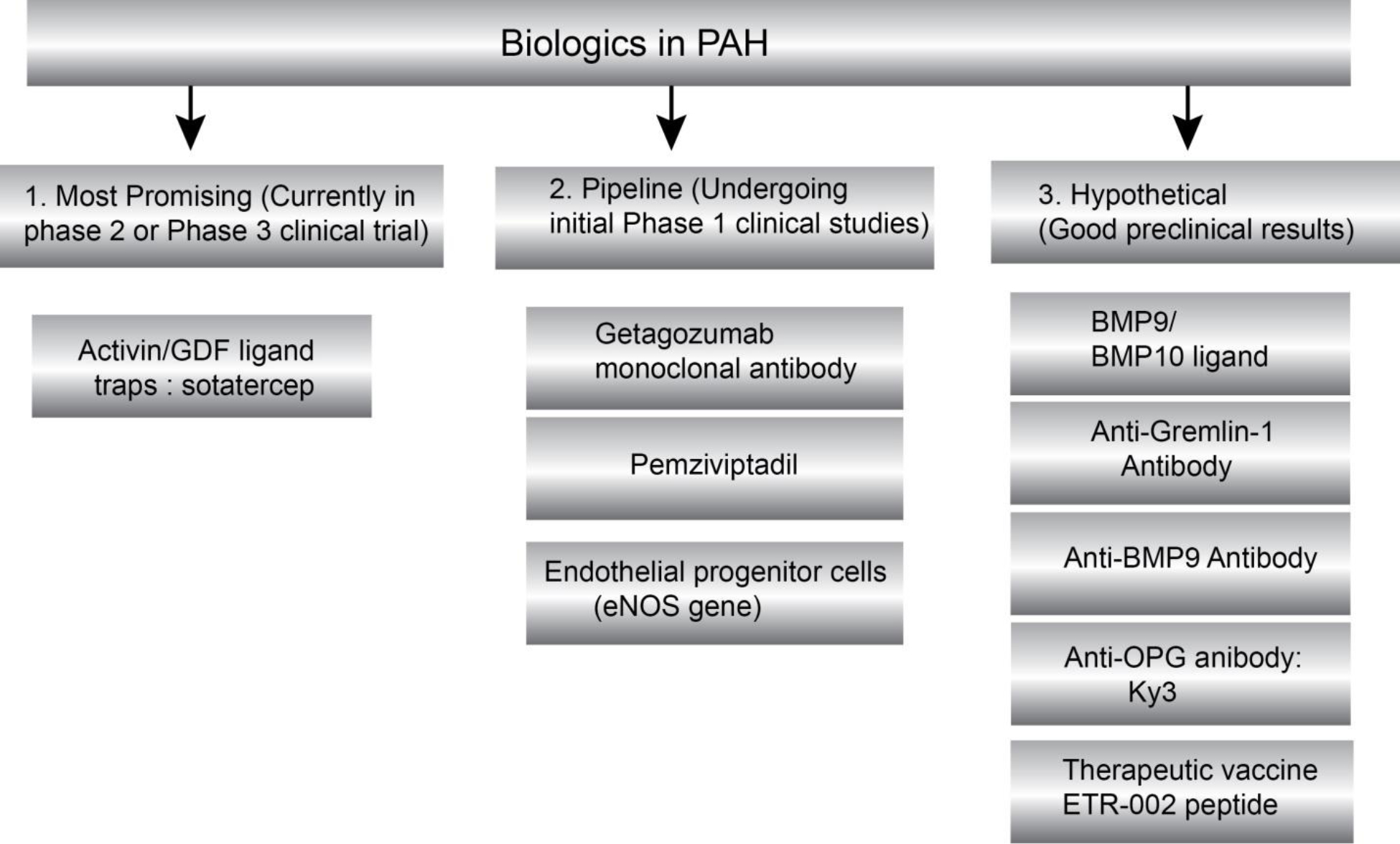

Both TGF-β and the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), two major subfamilies implicated in PAH, act via kinase-linked receptors with a serine/threonine kinase domain on the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane. There are two types of receptor serine/threonine kinases: type I and type II, which are structurally similar homodimers. TGF-β superfamily ligands such as activins, growth differentiation factors (GDF8, GDF11) [21] and BMP bind and activate a characteristic combination of type I and type II receptor dimers, bringing the kinase domains together by forming heterotetramer. GDF8 and GDF11 increase muscle mass and activate muscle fibroblast and fibrosis [22–24]. In the canonical pathway, binding of ligand to the constitutively active type II receptor phosphorylates a glycine-serine rich (GS) region of type I receptors, such as activin receptor-like kinases (ALKs). The activated type I receptor (ALK) directly binds and phosphorylates latent transcription regulators (Smad family proteins). Activated Smad proteins translocate into the nucleus and regulate the gene transcription [25–27].

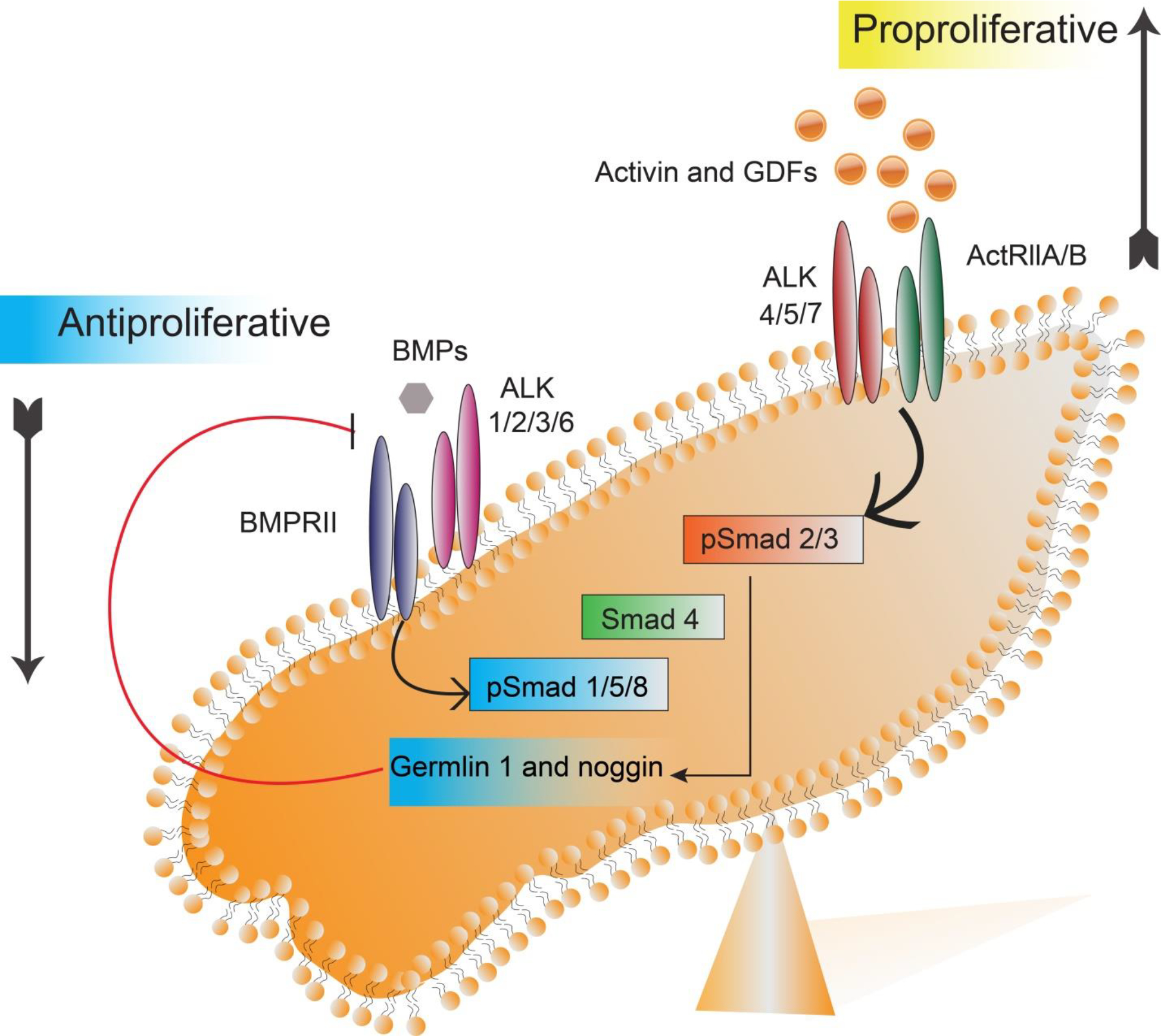

BMP ligands activate BMP receptors (type II receptors), which phosphorylate type I receptors (ALK 1/2/3/6). Activated type I receptor (ALK 1/2/3/6) phosphorylates and activates Smad1, Smad5, or Smad8. Similarly, activin ligands and growth differentiation factor ligands (GDF8, GDF11) bind to type II receptors such as activin receptor type II (e.g., ActRIIA) that phosphorylate type I receptor (ALK 4/5/7). Activated type I receptor (ALK 4/5/7) phosphorylates Smad 2 or Smad 3. Depending on the activated signaling pathway, these receptor-activated Smads (R-Smads) bind to Smad 4, called co-Smad, and thus form a complex before migrating into the nucleus. This complex controls transcription of specific target genes associated with other regulators (Figure 3). Because the regulator proteins vary depending on the cell type and state of the cell, expression of genes also vary [28–30]. For example, different combinations of regulatory Smad proteins can promote or inhibit the proliferation of vascular cells, which occurs through activation of a different set of genes. In pulmonary blood vessels, activated Smad 2/3 signaling (e.g., by activin, GDF8, GDF11 ligands) promotes proliferation of smooth muscle and endothelial cells. But activated Smad 1/5/8 signaling (e.g., by BMP ligands) inhibits their proliferation. The two opposing signaling pathways remain in equilibrium in healthy individuals [31,32].

Figure 3:

Two counter-regulatory pathways control gene transcriptions that determine the fate of pulmonary vascular modeling. Activin pathway promotes pulmonary vascular cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, whereas BMP pathways encourage cell apoptosis and inhibit proliferation and differentiation. In a healthy individual, the activin and BMP pathway are well balanced. Abbreviations: BMPs (Bone Morphogenetic Proteins), BMPRII (Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor II), GDFs (Growth Differentiation Factors), ALK (Activin receptor-Like Kinase), ActRIIA/IIB (Activin Receptor type IIA/IIB), Smad (an acronym from the fusion of Caenorhabditis elegans Sma genes and the Drosophila Mad, Mothers against decapentaplegic), GTF (general transcription factor).

Mutations in BMP receptor type II (BMPR II) are more common in heritable/familial PAH than in patients with IPAH. A deficient BMP9-BMPRII-ALK1-Smad 1/5/8 signaling pathway is a characteristic feature of familial PAH. In addition to BMPR II mutations, ALK1, GDF2/BMP9, Smad 4, and ENG (endoglin) genes may mutate, as observed in PAH patients with a family history of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) [33,34]. Paradoxically, IPAH also demonstrates reduced BMP signaling, suggesting that correction of BMPRII signaling pathway may bring about therapeutic benefits. Downregulation or reduced activity of the BMPR-II–Smad 1/5/8 pathway in the pulmonary vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells triggers an imbalance between pro-proliferative and antiproliferative function. This imbalance leads to the overactivity of activin ligands, such as activin A, GDF8, and GDF11, which activate the activin receptor type IIA (ActRIIA)–Smad 2/3 pathway. Activated Smad 2/3 promotes gene expression of two proteins: gremlin 1 and noggin. Gremlin 1 and noggin are natural BMP antagonists that further reduce BMP–Smad 1/5/8 signaling, and the process continues as a cycle. The cumulative effect of reduced anti-proliferative signaling shifts the balance toward pro-proliferative activin–Smad 2/3 signaling, which leads to pulmonary vascular remodeling [35,36].

Apart from upregulating the proliferative pathways that leads to PAH, deficiency in BMPRII pathway is also involved in endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT), which induces hyperactive TGF-β signaling resulting in PAH [37]. BMPRII silenced human lung microvascular vascular endothelial cells (HLMVECs) have been found to impair endothelial barrier function in vitro and in conjunction of the activation of p38MAPK and heightened inflammation may trigger PAH [38,39].

Biologics for PAH

1. Monoclonal antibody targeting TGF-β signaling pathway

Both in vitro and in vivo studies showed that restoring the balance between activin/GDF signaling and BMP signaling reverses pulmonary vascular remodeling. Several biologics such as activin/GDF ligand traps, BMP9 recombinant proteins, and anti-BMP9 and anti-gremlin antibodies showed promising results in preclinical studies, which we will discuss in this section below.

1.1. Activin/GDF ligand traps:

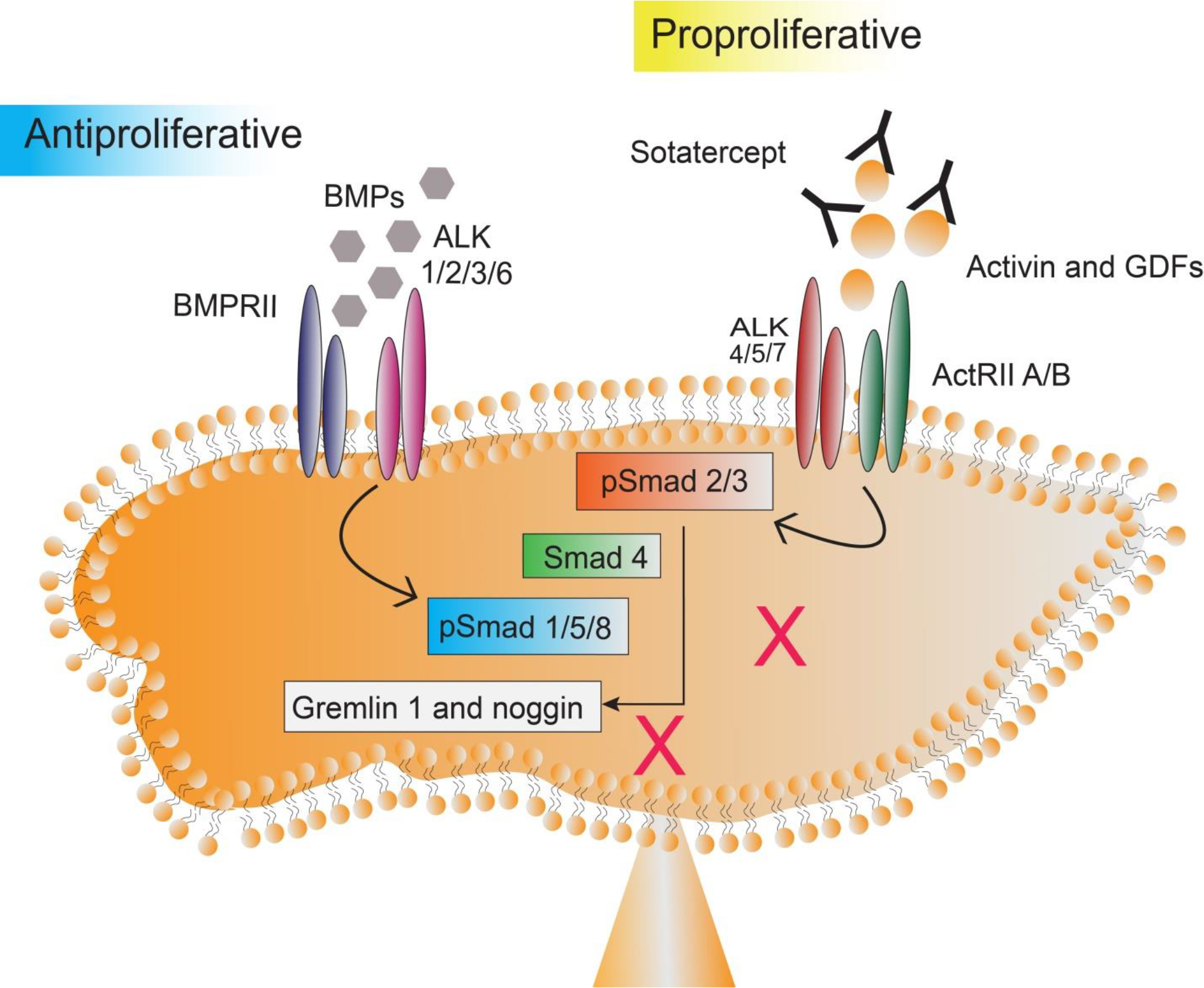

Acceleron Pharma developed a novel fusion protein monoclonal antibody called sotatercept, an activin/GDF ligand trap that binds to ligands in the TGF-β superfamily, such as activin A and B, GDF8 and GDF11. By sequestering excess ligands, sotatercept reduces Smad 2/3 growth-promoting signaling, restoring the balance at the Smad 1/5/9 growth-inhibiting signaling pathway level (Figure 4A and 4B). The net effect is reflected as a significant reduction in the proliferation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells [35,40,41]. The FDA granted orphan drug designation and breakthrough therapy status for use of sotatercept in PAH.

Figure 4:

(A) Excessive levels of activin and GDF ligand binding to ActRIIA/B receptor overstimulate the activin pathway. Reduced BMP ligand activity of the BMP pathway is responsible for maladaptive pulmonary arterial remodeling.

Figure 4:

(B) Sotatercept monoclonal antibody intercepts activin and GDF ligands before receptor binding and helps downregulation of the activin pathway at the level of the existing BMP pathway. Thus, sotatercept establishes a balance between activin and BMP signaling.

1.1. (a) Antibody Characteristics:

Sotatercept is a fusion protein comprising of the extracellular domain of TGF-β receptor type II-A (ActRIIA) linked to the human IgG1 Fc domain (ActRIIA-Fc). It neutralizes a range of TGF-β ligands before binding to the receptor and thus inhibits signaling through the receptor. Sotatercept binds to activins A and B, GDF8 and GDF11, and BMPs (BMP6, BMP7) with affinities reflecting the binding profile of native ActRIIA. Sotatercept exhibits reduced binding affinity for BMP9 ligand and does not interfere with the BMP9 signaling through ActRIIA [42]. A sotatercept analog, called RAP 011, has been developed through the fusion of the extracellular domain of human ActRIIA attached to murine IgG2a-Fc domain instead of a human domain. RAP 011 showed cardioprotective effect in experimental animal models by reducing RVH and pressure overload [43]. A similar analog called luspatercept contains a modified extracellular domain of activin receptor type IIB (ActRIIB) attached to the Fc domain of human IgG1 (modified ActRIIB-Fc). Luspatercept binds to GDF8, GDF11, and activin B with a higher affinity and to activin A with a reduced binding affinity [44–46].

Both Sotatercept and luspatercept were developed to increase bone mineral density in malignant bone disease or osteoporosis but were found to increase red blood cells in early human studies [47]. Luspatercept is now repurposed for anemia because of its excellent ligand selectivity and improved clinical efficacy in raising red blood cell counts and hemoglobin concentrations [48–50]. Recently, the FDA approved luspatercept for the treatment of anemia in myelodysplastic syndrome.

1.1. (b) Preclinical Studies:

In pulmonary blood vessels of IPAH and HPAH patients, levels of activin A and GDF 8/11 ligands are reported to increase. In PAH-derived endothelial cells, these ligands preferentially stimulate Smad 2/3 signaling, activate Smad 1/5/9 signaling, and cause enhanced proliferation with reduced apoptosis. Application of sotatercept blocks activin- and GDF ligand-activated Smad 2/3 signaling and Smad 1/5/9 signaling but does not interfere with BMP9- activated Smad 1/5/9 signaling. In monocrotaline (MCT)-induced rat model of PAH, prophylactic administration of sotatercept reduced mPAP and arterial remodeling without affecting systemic arterial pressure. However, in the same PAH model, prophylactic therapy with sildenafil failed to reverse pulmonary vascular remodeling. In another study, administration of sotatercept four weeks after the development of MCT-induced PAH model showed similar therapeutic benefits. In SU5416-hypoxia (Su-Hx)-induced rat model of PAH, prophylactic and therapeutic administration of sotatercept normalized mPAP and vessel wall thickness without affecting systemic arterial pressure, suggesting that this agent is unlikely to produce hypotension [36].

1.1. (c) Clinical Studies:

In Phase 2 placebo-controlled, multicenter, randomized clinical trial (PULSAR), sotatercept treatment showed encouraging therapeutic benefits in PAH patients. One hundred six patients, who were on a standard of care therapy, received subcutaneous injections of either a placebo, sotatercept 0.3 mg/kg, or sotatercept 0.7 mg/kg every 21 days for a period of 24 weeks. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was used as the primary clinical endpoint and 6-MWDT and amino-terminal brain natriuretic propeptide (BNP) were used as secondary clinical endpoint. Both 0.3 mg/kg and 0.7 mg/kg doses of sotatercept significantly reduced PVR compared to placebo. Sotatercept also improved the secondary endpoint such as an increase in the 6-MWDT and reduction in BNP. Increased hemoglobin concentration and thrombocytopenia were the most reported adverse effects [35]. In PULSAR open-label extension study, administration of sotatercept at 0.3 or 0.7 mg/Kg in conjunction with approved drug therapy displayed long-term safety and efficacy (18–24 months). The most common adverse effects were leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. A few patients (10%) developed mild telangiectasias after 1.5 years of sotatercept therapy [51]. Sotatercept is now undergoing multiple Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials such as HYPERION, ZENITH, and SOTERIA [52].

Sotatercept pharmacokinetics was studied on anemic postmenopausal healthy women at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg, 0.3 mg/kg, and 1 mg/kg. The subcutaneous dose was administered every 28 days for four weeks. One-compartment model analysis showed that sotatercept follows first-order absorption and elimination, with a dose-dependent increase in the area under the curve (AUC). The constant value of half-life and clearance indicates linear first-order elimination. The long half-life of sotatercept, approximately 23 days, suggests that the drug can be administered at a reduced frequency [53].

1.2. BMP9 ligand and anti-gremlin 1 antibody versus anti-BMP9 antibody in PAH treatment: the BMP paradox

The genetic defect in BMPRII and the downregulation of this pathway play a major role in the pathogenetic mechanisms of IPAH. However, even two decades after the discovery of genetic defects in BMPRII gene, no drug targeting this pathway has yet been approved. Further, recent studies showed conflicting data whether the stimulation or inhibition of the BMP pathway would produce therapeutic benefits in PAH. Here, we have summarized recent observations concerning BMP ligands and their therapeutic potential as biologics for PAH.

1.2. (a) BMP9 ligand for potential therapeutic intervention in PAH:

The normal function of the BMP9/BMP10 ligand-mediated BMPRII/ALK1 signaling pathway plays an important role in maintaining the internal diameter of the pulmonary artery and vascular integrity [54,55]. BMP9, synthesized by the liver, circulates in the plasma and selectively binds to the BMPRII/ALK1 receptor complex with a higher affinity than other ALKs. For example, BMP2 and BMP4 have a higher affinity for ALK3 and BMP14/GDF5 has higher affinity for ALK6 than other ALKs [56,57]. Disruption of this standard signaling mechanism due to receptor malfunctions or low circulating levels of BMP9 or BMP10 promotes hyperproliferation and thickening of the endothelium, leading to the development of PAH. A recent study suggests that liver cirrhosis patients with portal hypertension have low levels of circulating BMP9 that predisposes them to PAH [58]. So, BMP9 protein could be an effective therapeutic approach.

Recombinant BMP9 protein is reported to selectively stimulate BMPRII/ALK1 receptor complex and reverse pulmonary hemodynamics to a healthy state [59]. Of the various BMP ligands, BMP9 and BMP10 ligands showed a higher affinity for the BMPRII-ALK1 complex (e.g., BMP9 1 ng/ml vs for BMP2, BMP4 or BMP6 50–200 ng/ml required to stimulate the BMPRII) [60]. A comparative study using BMP9, BMP2 and BMP6 showed a prominent downstream effect in the BMPRII signaling by BMP9 stimulation compared with the latter two ligands. The study showed that BMP9 upregulates BMPRII expression irrespective of the presence of genetic mutation in PAH. BMP9 administration reversed PAH in both MCT and SuHx models, whereas it restored BMPRII levels and its downstream signaling molecules close to that of normal level in an MCT model. In SuHx model, mPAP, right ventricle (RV) weight and levels of muscularization in pulmonary arterioles were restored to the healthy state. This study suggests that BMP9 ligand can be a potential therapeutic agent for PAH [59]. Exogenous BMP ligands may activate other BMP receptors in a dose-dependent manner leading to potential side effects. For instance, a high dose of BMP9 (≥ 5 ng/ml) may cause tissue calcification due to the activation of ALK1 and ALK2 in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. In contrast, a low dose of BMP9 (0.5 ng/ml) activates only ALK1 without any observed tissue calcification. Interestingly BMP10 is less osteogenic than BMP9, indicating a safer alternative for PAH treatment [61].

1.2. (b) Anti-gremlin-1 antibody as a potential therapy in PAH:

Gremlin-1, a natural secretory protein, is primarily produced by the endothelial cells in the lung. Alveolar hypoxia triggers gremlin-1 overexpression that promotes pulmonary arterial endothelial cell (PAECs) lesions. Indeed, increased gremlin-1 expression is observed in hypoxic PAH patients. Patients with pulmonary hypertension due to heart disease (WHO Group 2 PH) also showed an elevated level of gremlin-1. Congenital heart disease-associated PAH patients (WHO Group 1 PH) usually experience systemic-to-pulmonary shunt, leading to increased shear stress and intraluminal mechanical stretch on PAECs. This pressure overload increases gremlin 1 expression in the lungs in a time-dependent manner. Additionally, the mechanical stretch raises the gremlin 1 level in the distal PAECs [62].

In chronic Su-Hx mouse models for PAH, prophylactic and therapeutic use of anti-gremlin-1 antibody ameliorated remodeling of pulmonary vasculature and RVH [63]. The preventive and therapeutic benefit of the anti-gremlin-1 antibody makes it a potential candidate for further study for PAH treatment.

1.2. (c) Anti-BMP9 antibody as a therapeutic candidate for PAH:

Instead of using of BMP9 ligand for PAH therapy [64], anti-BMP9 antibody can also be used for PAH, which is known as BMP paradox. With more than 20 BMP ligands, five type I receptors, and four type II receptors, the mode of action of the BMP ligands and receptors is very complex [59,64]. Using chronic hypoxia-induced PAH models, Ly Tu et al. showed that the administration of an anti-BMP9 antibody in C57BL/6 mice or loss of BMP9 in Bmp9 knockout mice largely prevented the development of PAH. Anti-BMP9 antibody decreases the generation of a potent vasoconstrictor, endothelin-1, but increases the concentrations of two potent vasodilators, adrenomedullin and apelin. Apart from using the anti-BMP9 antibody, this group also validated the therapeutic benefit of an extracellular ligand-binding domain of the ALK1 receptor as a soluble ligand trap for BMP9 and BMP10 in both MCT and Su-Hx rat models of PAH. BMP9/BMP10 ligand trap significantly reduced elevated mPAP in rats, proliferation of pulmonary vascular cells and infiltration of inflammatory cells [65]. However, this study that used an anti-BMP9 antibody as a possible therapy for PAH suffers from a number of limitations. For instance, Morrel et al. noted that Tu et al. did not examine the effect of BMP9 or BMP10 ligands on Bmp9 knockout mice. In PAH patients, stimulation of BMP9/BMPRII/ALK1 signaling improves pulmonary hemodynamics. Mutation or interruption in this signaling axis might create hemorrhagic telangiectasia-like conditions such as dilated thin-walled capillaries and vessels. Thus, it is unsurprising that a mouse deficient in BMP9 or using an anti-BMP9 antibody showed pulmonary arterial vasodilation in chronic hypoxic conditions. The study reported by Ly Tu et al. did not show that the anti-BMP9 antibody reversed pulmonary hemodynamic [66]. Thus, Morrel et al. suggested that BMP inhibition as a therapeutic intervention in PAH would cause more harm than good. In response to this concern, Ly Tu et al. indicated that a thorough study might untangle this complex paradox of the BMP9/BMPRII/ALK1 axis in PAH [67].

We believe that BMP inhibition is unlikely to be an effective therapeutic strategy for PAH. Rather, BMP analogs such as BMP9 ligand would be a viable and superior strategy. Because pulmonary endothelium is disrupted in PAH, ligands that would selectively target this structure could be therapeutically superior. To this end, BMP9 has been shown promise over other BMPs such as BMP2, 4 or 6, wherein BMP9 was able to stimulate pulmonary endothelium at a very low dose compared to other BMPs (1 ng/ml for BMP9 vs. 50–200 ng/ml for other BMPs) [68,69]. Indeed, BMP9 ligand could reverse advanced vascular endothelium in Su/Hx models that closely resemble human PAH.

1.3. Anti-osteoprotegerin (OPG) antibody in the treatment of PAH

Recently, Arnold et al. reported an elevated level of OPG expression in SuHx- and MCT-induced PAH in mice and rats, respectively. A human anti-OPG antibody (the Ky3 antibody) is used to target OPG, which reverses PAH progression by improving pulmonary hemodynamics and pulmonary vascular remodeling. The efficacy of Ky3 in improving pulmonary hemodynamics is equivalent to that of currently used small molecule drugs. Furthermore, combining Ky3 with the approved standard of care, such as sildenafil or bosentan, causes major reduction in blood vessel remodeling when compared with sildenafil or bosentan alone [70].

1.3. (a) Role of OPG in PAH pathogenesis:

OPG, a secretory glycoprotein, is also known as tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 11B and osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor [71–73]. In its monomeric form, the molecular weight of OPG is 60-kDa, which is expressed in the lungs and heart, and other tissues. OPG acts as a ligand trap and competitively inhibits the binding of receptor activator of NF-κB (RNAK) to RNAK ligand and the binding of TRAIL ligand (tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) to death receptors. Thus, OPG prevents apoptosis and promotes proliferation in different dells. In PAH, OPG is upregulated in vascular cells by different ligands and cytokines, including BMPs and IL-1 [74,75].

Downregulation of the BMPRII pathway and upregulation of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1 are reported to upregulate OPG, linking major pathological pathways of PAH with OPG. Thus, multiple pathways appear to converge on a common signaling hub via OPG, upregulation of which causes vascular cell proliferation and leading to PAH [74]. A recent study reported the role of Fas as a receptor of OPG wherein OPG-Fas interaction, via activation of downstream protein signaling molecules, can promote proliferation and migration of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). Fas neutralization reduced OPG-induced PASMC migration and proliferation in vitro. This study proposed that OPG-Fas induction of intracellular kinase signaling such as phosphorylation of ERK1/2, CDK4/5 was responsible for activating genes associated with PAH and thus promoting cell survival, migration, and proliferation. Thus, abnormal proliferation of vascular cells promotes narrowing of arteries in the lungs, a major cause of elevated mPAP in PAH [70]. Daile Jia et al. showed that mice lacking OPG do not fully develop PAH, as evidenced by reduced proliferation of PASMCs and ECs when challenged with SU5416–hypoxia. However, PAH pathologies worsened when OPG was delivered using lentiviral vectors [75], as shown by increased remodeling of vascular cells.

1.3. (b) The promise of anti-OPG antibody Ky3 in PAH:

OPG plays an important role in the pathogenesis of PAH by enhancing the growth and migration of PASMCs. An elevated level of this protein has been observed in the lungs of PAH subjects. Fas acts as a receptor of OPG, where OPG-Fas interaction activates intracellular kinase signaling such as phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and CDK4/5 that activate genes promoting proliferation and migration of PASMCs. Fas neutralization significantly reduces OPG-induced PASMC migration and proliferation in vitro [76]. Lawrie et al. investigated the role of OPG and its mode of downstream signaling in PASMCs. Mice lacking OPG gene developed a mild form of the disease when challenged with SuHx. In consistent with this observation, there was an improvement in PAH pathology when Ky3 antibody was administered in SuHx or monocrotaline-challenged rats. This makes Ky3, an anti-OPG antibody, a potential biologic for PAH treatment. The Lawrie group demonstrated that Fas worked as the receptor for OPG. Upon activation of Fas receptor-OPG ligand, genes and proteins were activated downstream in the signaling process. This study suggests that genes responsible for PAH development upregulated Caveolin-1 (CAV1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFA) and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), and NFκB. Upon treatment with antibodies against both Fas and OPG, improvements were observed in all hallmarks of PAH pathologies including cell proliferation, migration, and inflammation. Amelioration of PAH pathologies occurred due to the inhibition of the same genes activated by OPG-Fas signaling. This led us to believe Ky3 antibody can be a new biologic for the treatment PAH. Anti-OPG treatment did not exhibit any deleterious effect on the bone turnover [77]. However, future clinical trials can establish whether the use of Ky3 antibody is a viable option for PAH therapy.

2.1. Biologics targeting endothelin receptor type A in pulmonary arterial hypertension

Endothelin-1 (ET-1), an endogenous peptide with vasoconstrictive property, is secreted from vascular ECs. This peptide is produced in the lung epithelium, kidney, and colon. ET-1 is synthesized via two pathways: (i) constitutive and (ii) regulatory. The constitutive pathway continuously secretes ET-1 and maintains the vascular tone. The regulatory pathway releases ET-1 in response to external stimuli such as hypoxia, shear stress, and excessive TGF signaling via the ALK5/Smad 3 pathway. Patients with PAH also express a high level of ET-1, which preferentially acts through endothelin receptor A (ETA), triggering pulmonary vasoconstriction and proliferation. Thus, ET-1/ETA receptor signaling is an important therapeutic target for PAH. ET-1 may also interact with endothelial ETB receptors in an autocrine manner and thus offset the constrictive effects by releasing vasodilators such as nitric oxide [78].

Several small-molecule endothelin receptor antagonists are already available as anti-PAH drugs that include bosentan, macitentan, and ambrisentan. These drugs, although are in clinical use for more than a decade, suffer from several shortcomings such as short half-life, non-selective blocking of ETA versus ETB by bosentan and macitentan, in addition to adverse effects such as anemia and elevated liver enzymes. The following section summarizes two investigational biologics that selectively antagonize ETA receptors: getagozumab, a monoclonal antibody and ETR-002 peptide, a therapeutic vaccine.

2.1. (a) Getagozumab monoclonal antibody:

Gmax Biopharma developed this murine antibody by hybridoma technology and then humanized it as IgG4 isotype. Getagozumab selectively antagonizes human ETA with a high binding affinity (Kd = 8.7 nM). In the hypoxia-induced cynomolgus monkey model of PAH, a single dose of intravenous getagozumab, when given at a 5 mg/kg dose, reduced pulmonary arterial pressure. When the dose was increased to 15 mg/kg twice per week for six weeks, the drug reduced the rise of the right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) by 54% compared to the control group of MCT-induced PAH monkey model. Further, pulmonary arterial wall thickness and RVH index, known as Fulton’s index, declined by 47.8% and 38.7%, respectively when compared with those in MCT induced monkey model of PAH. This reduction in RVSP was statistically significant when compared with animal treated with 1 mg/kg ambrisentan. Acute and chronic toxicity studies in cynomolgus monkeys confirmed the drug’s safety with a no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) at 750 mg/kg for a single-dose toxicity and a NOAEL of 250 mg/kg for a 4-week safety study. When the dose was translated to humans, getagozumab was well tolerated up to 1000 mg as a single dose. The pharmacokinetic study showed that the antibody has a half-life of ~ 23 days. Currently, this antibody is undergoing a Phase 1b trial at different sites in the US and China (NCT04505137) [79].

2.1. (b) Therapeutic vaccine (ETR-002 peptide):

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) receptor type A (ETA) is a G protein-coupled receptor. Binding of ET-1 to ETA receptor’s extracellular loop 2 (ECL2) activates the receptor and thus triggering a downstream signaling cascade [80]. Dai et al. designed a linear epitope of ten amino acids peptide (ETR- 002) based on the ECL2 sequence of human ETA. ETR-002 peptide was covalently conjugated with a Qβbacteriophage virus-like particle to develop it into a vaccine (termed ETRQβ-002). The vaccine produced enough anti–ETR-002 antibody titer upon subcutaneous injection in MCT-induced rats (1:100,000 to 1:150,000). The ETRQβ-002 vaccine and the purified monoclonal antibody (mAb) against ETR-002 effectively reduced RVSP, RVH and myocardial fibrosis in MCT-induced PAH rats and in Sugen/hypoxia-induced mice. No immune-mediated injury was observed in vaccinated animals [81,82].

2.2. Biologics targeting Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) signaling for PAH

The vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) is a vasodilatory chemical messenger that is expressed in various organs including nervous systems, blood vessels, immune cells, and lung tissues. In the lungs, VIP relaxes pulmonary vascular smooth muscle [83,84], neutralizes pulmonary vasoconstrictor endothelin, inhibits PASMC proliferation [85,86], and produces anti-inflammatory actions [87]. VIP acts through G-protein coupled receptors, VPAC1 and VPAC2, regulate the vascular tone [88]. VIP null (VIP −/−) mice developed spontaneous PAH, suggesting its role in PAH pathogenesis [89]. Patients with PAH show reduced lung and serum VIP levels and upregulated VPAC1 and VPAC2, suggesting that targeting VIP might be a clever approach for PAH therapy. In VIP deficient mice, VIP treatment improved pulmonary vascular remodeling, RVH, and lung inflammation [90,91]. VIP is also reported to reverse MCT-induced PAH in rats, such as lowering of RVSP and RVH. Compared to bosentan, VIP was more effective in ameliorating PAH symptoms and when used in combination with bosentan, VIP elicited a synergistic effect in improving pulmonary hemodynamics [92].

Despite these promising results, VIP (aviptadil) has a plasma half-life of one minute and binds nonspecifically to VPAC1 and VPAC2 receptors. Further, systemic administration of VIP is associated with side effects such as severe diarrhea [93].

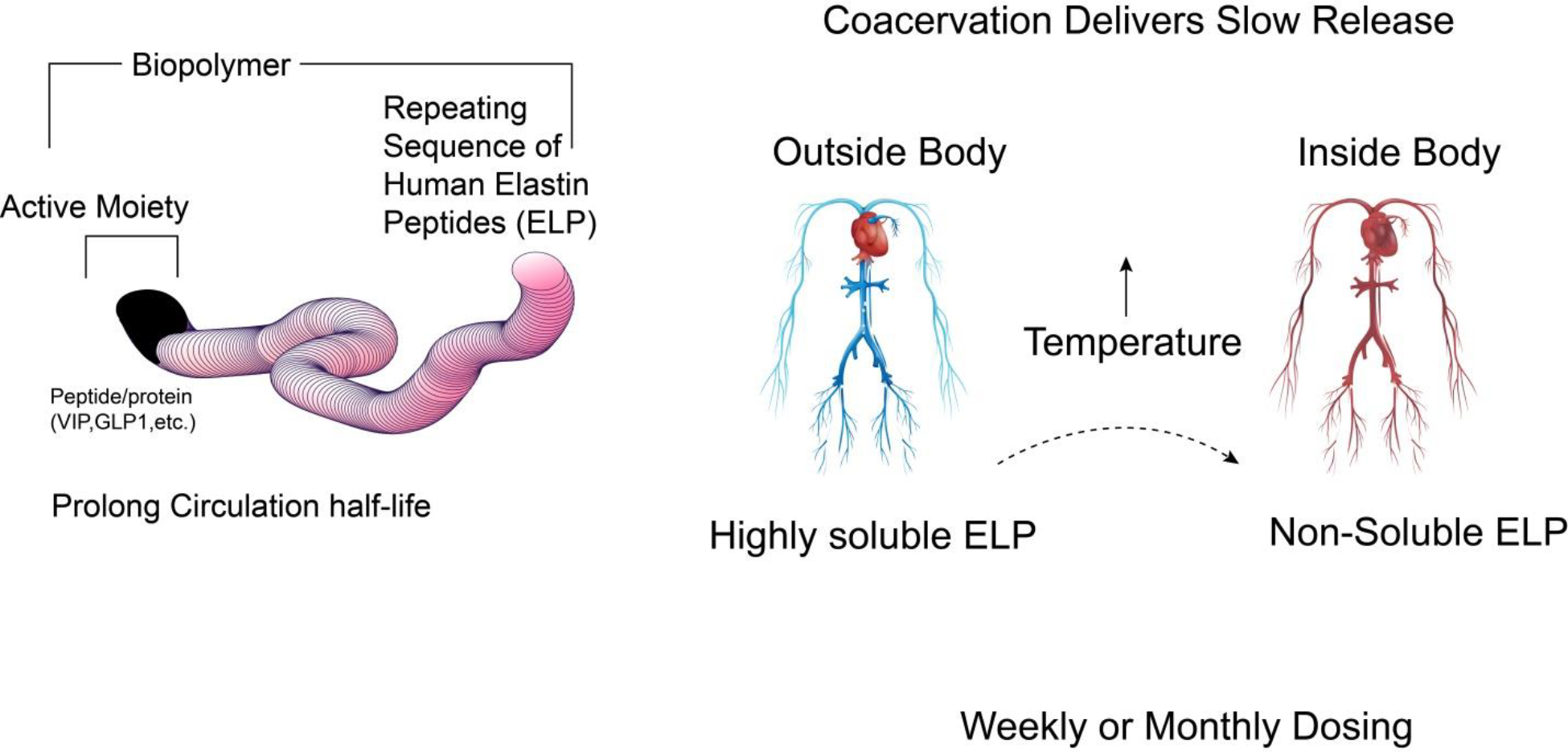

PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals developed an investigational VIP analog (pemziviptadil) with a longer half-life (60 hours) that preferentially binds to VPAC2. Pemziviptadil was developed by genetically fusing VIP to a human elastin peptide sequence mimicking a biopolymer. Upon delivery, the biopolymer VIP solution undergoes coacervation at body temperature and thereby separates the biopolymer solution into two immiscible liquid phases leading to a slow release of VIP (Figure 5). Pemziviptadil was tested in PAH patients in an open-label, multi-dose Phase 1 pilot study. The PAH patients were implanted with the CardioMEMS™ HF System, which monitors pulmonary arterial pressure through a sensor. In this study, three PAH patients received a subcutaneous injection every week for eight weeks. Pemziviptadil was well tolerated with no significant adverse effects. It reduced mPAP, PVR and improved 6-MWT after 18 months of therapy [94,95]. Currently, the Phase 2 clinical trial of this analog is suspended due to COVID-19-related drug supply and manufacturing issues (NCT03556020, NCT03795428).

Figure 5:

A sustained release vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) analog -Pemziviptadil. Pemziviptadil is a long-circulating (60 hours in humans) VIP biopolymer for treating PAH, addressing the limitation of short-acting natural VIP (1 minute in humans).

3. Cell-based therapy in PAH:

Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) have the potential to ameliorate vascular lesions, drive angiogenesis and eventually improve endothelial dysfunctions [96]. EPCs have been investigated in both preclinical and clinical settings. In preclinical studies, cell-based introduction of eNOS gene prevented the development of PAH in MCT model [97]. In a Phase 1 trial (PHACeT; NCT00469027), EPC based eNOS gene therapy reduced pulmonary arterial resistance along with major improvements in functional class, 6-MWDT and quality of life. Currently, another clinical trial is underway (SAPPHIRE; NCT03001414) that used repeated and incrementally increased dosing of eNOS introduced EPCs for assessing the safety and efficacy of this cell-based therapy in PAH [96,98].

4. Repurposing Biologics in PAH:

Due to slow pace of drug discovery and development and the high cost for the development of new drugs, various FDA-approved drugs have been proposed to be repurposed for the treatment PAH. Drug repurposing that have been successful for the treatment of PAH include epoprostenol, a prostaglandin analog, calcium channel blockers, sildenafil and tadalafil, two PDE-5 inhibitors. The biologics that can possibly be repurposed for the treatment of PAH include anakinra, a monoclonal antibody as IL-1 receptor antagonist; rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody; and etanercept, a fusion protein targeting tumor necrosis factor [99,100]. However, etanercept has not yet undergone for any clinical testing. Further, tocilizumab, a monoclonal antibody that works as IL-6 receptor antagonist, although did not improve PAH features in Phase 2 clinical trial, has shown modest improvement in PVR in a subgroup of patients with connective tissue disease (CTD) [101].

Conclusion:

Since the discovery of the first mutation in the BMPRII gene in 2000, several hundred mutations have been identified in BMPRII gene alone that are implicated in the genesis of PAH. However, mutations in BMPRII and several other genes, including ALK1 and ENG, exhibit an incomplete penetrance of PAH phenotypes that genetics alone cannot explain. Indeed, nongenetic alteration such as epigenetics is involved in many cellular signaling pathways including growth, proliferative and inflammatory pathways. In PAH, the balance between proliferative and anti-proliferative regulatory mechanisms such as apoptosis is impaired which leads to the development of the disease. Thus, there is reason to believe that PAH can no longer be defined only by the traditional vascular tone imbalance phenomenon, but its cancer-like aberrant growth and proliferative mechanisms should also be considered. Biologics, including antibodies, fusion proteins, and related natural or engineered biomolecules hold promise to be superior alternative to the existing therapy that mainly targets the vasodilatory-vasoconstrictive pathways. Indeed, by targeting different growth, apoptotic and immunomodulatory pathways, biologics may emerge as add-on therapy with improved safety profiles and better therapeutic efficacy. Both preclinical or clinical studies suggest that biologics can target vasodilatory, proliferative, and apoptotic pathways that are the major pathological basis for PAHs. Sotatercept and a monoclonal antibody against OPG (Ky3) target the aberrant growth phenomenon in PAH. We have delineated the role of BMP paradox by describing relative efficacies of BMP analog or anti-BMP antibodies for the treatment of PAH. Thus, given their complexity and involvement of many ligands and receptors, the BMP pathways warrant further elucidation in PAH research. In regulating the vasodilatory pathways, a vaccine targeting the ETA receptor, a peptide analog targeting vasoactive intestinal peptide, and a monoclonal antibody, getagozumab, targeting the ETA receptors showed promise in the PAH rodent model (Table-1).

However, some drugs targeting the pathological pathways of PAH, although showed great potential in preclinical studies, failed to show therapeutic benefit in PAH patients. For example, IL-6 was reported to cause PAH by promoting proliferation of PAECs and PASMCs [102] and IL-6 blockade to ameliorate PAH in rodent models [103,104]. IL-6-blocking monoclonal antibody tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antagonist, although showed efficacy in a PAH patient with mixed connective tissue disease [105], did not show therapeutic benefit in Phase 2 open-label clinical trial [106]. The trial showed that despite an increase in IL-6 level in PAH patients with connective tissue disease, IL-6 level was not directly linked to PVR or heart failure, indicating PVR is not the best clinical endpoint for evaluating the efficacy of IL-6-targeted therapies. Similarly, Rho-kinase-mediated vasoconstriction is known to be responsible for generating PAH in rat models [107] and inhaled Rho-kinase inhibitors were able to work as a powerful vasodilator in rat PH models [108], reversing vasoconstriction. Fasudil, a Rho kinase inhibitor, although showed encouraging data in rodent models of PAH, was not effective in clinical trials, even when an extended-release formulation was used [109].

Data generated in animal models often cannot be reproduced in humans and thus translational feasibility remains a major challenge. Although animal models are important tools for studying PAH pathophysiology and efficacy of anti-PAH drugs, none of them accurately mimic human PAH disease. Using human PAH cells/tissues in the “lab on a chip” model or developing a “lung on a chip model” may close the gap between preclinical and clinical data [110,111]. Further, in preclinical PAH studies, clinically relevant endpoints are rarely used. For instance, preclinical studies that last for 3 to 4 weeks are inadequate to determine long-term efficacy, toxicity, or survival benefits. Furthermore, the functional capacity of the treated animal, cardiac output, and status of RV functions are rarely studied. Thus, it is important to note that preclinical therapy improves RV function and cardiac output and decreases mPAP or pulmonary vascular remodeling. In a rare disease like PAH, clinical studies often enroll patients with varied underlying etiologies that may influence the study outcomes. Selecting accurate patient cohorts with defined pathophysiology is likely to address the limitations associated with clinical trials for PAH. Defined molecular phenotypes may allow clinical trials in specific subgroups of patients with a higher probability of therapeutically relevant outcomes. For example, patients with BMPRII mutations may be good candidates for a therapy that enhances downstream BMPRII signaling. However, very stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria may lead to a small sample size, raising questions about the statistical validity of the study [112,113].

Moreover, regulatory authorities may impose additional layers of barriers that impede the clinical translation of biologics. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) follow specific laws and guidelines for regulatory approval of biologics. Sometimes these laws and policies take time to untangle and place undue pressure on regulatory affairs, especially in explaining why a biologic is placed under one regulation rather than another [114].

Biologics’ chemistry, manufacturing, and control (CMC) are complicated, expensive, and time-consuming processes. It takes more resources to operate, has more demanding and costly quality control release and stability tests, and has many batches and testing records for quality assurance (QA) to review, which takes QA longer to release each product batch [115]. Unlike chemical drugs, minor changes in the structure of biologics can significantly impact the molecule’s efficacy and safety. Thus, biologics must be tested for extensive physicochemical characteristics using an array of analytical methods. Since Biologics are made from a variety of natural resources, they are also prone to microbial contamination. Thus, proper manufacturing control must be in place to prevent microbial contamination and adequate inactivation/removal methods in case microbial contamination occurs [116].

In short, biologics have excellent prospects that, along with existing PAH therapies, may galvanize a major shift in the therapeutic modality of PAH by improving the patient’s quality of life and survival. A carefully designed preclinical and clinical studies with appropriate selection of clinical endpoints should be in place for successful clinical translation of PAH therapeutics. Many of these barriers can be overcome via collaboration between academic and drug development establishments.

Acknowledgments:

This study is supported in parts by a fund from NIH 1R01HL144590–01 (to F.A.), NIH R42HL151045 (to F.A.) and Cardiovascular Medical Research and Education Funds (to F.A). D.S. is supported in part by a fund from the DOD (W81XWH-20–1-0702).

References

- 1.Hye T, Dwivedi P, Li W, et al. Newer insights into the pathobiological and pharmacological basis of the sex disparity in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2021. Jun 1;320(6):L1025–L1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2022. Aug 30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemnes AR, Humbert M. Pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension: understanding the roads less travelled. Eur Respir Rev. 2017. Dec 31;26(146). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommer N, Ghofrani HA, Pak O, et al. Current and future treatments of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2021. Jan;178(1):6–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemnes AR, Humbert M. Pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension: understanding the roads less travelled. European Respiratory Review. 2017;26(146):170093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voelkel NF, Gomez-Arroyo J, Abbate A, et al. Pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension and right ventricular failure. European Respiratory Journal. 2012;40(6):1555–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prostacyclins Olschewski H. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;218:177–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockrill BA, Waxman AB. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;218:229–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abman SH. Inhaled nitric oxide for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;218:257–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galiè N, Barberà JA, Frost AE, et al. Initial Use of Ambrisentan plus Tadalafil in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015. Aug 27;373(9):834–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuwana M, Blair C, Takahashi T, et al. Initial combination therapy of ambrisentan and tadalafil in connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (CTD-PAH) in the modified intention-to-treat population of the AMBITION study: post hoc analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. May;79(5):626–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cascino TM, McLaughlin VV. Upfront Combination Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Time to Be More Ambitious than AMBITION. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021. Oct 1;204(7):756–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoeper MM, Pausch C, Grünig E, et al. Temporal trends in pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the COMPERA registry. Eur Respir J. 2022. Jun;59(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin KM, Sitbon O, Doelberg M, et al. Three- Versus Two-Drug Therapy for Patients With Newly Diagnosed Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;78(14):1393–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitre T, Su J, Cui S, et al. Medications for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2022. Sep 30;31(165). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanatta E, Polito P, Famoso G, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in connective tissue disorders: Pathophysiology and treatment. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2019. Feb;244(2):120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galiè N, Channick RN, Frantz RP, et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. European Respiratory Journal. 2019;53(1):1801889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldo BA. Approved Biologics Used for Therapy and Their Adverse Effects. Safety of Biologics Therapy: Monoclonal Antibodies, Cytokines, Fusion Proteins, Hormones, Enzymes, Coagulation Proteins, Vaccines, Botulinum Toxins. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boehncke W-H, Radeke HH. Introduction: Definition and Classification of Biologics. In: Boehncke W-H, Radeke HH, editors. Biologics in General Medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2007. p. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owens SM. Monoclonal Antibodies. In: Montoya ID, editor. Biologics to Treat Substance Use Disorders: Vaccines, Monoclonal Antibodies, and Enzymes. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker RG, Czepnik M, Goebel EJ, et al. Structural basis for potency differences between GDF8 and GDF11. BMC Biology. 2017 2017/March/03;15(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baglieri J, Bertoni C. Chapter 10 - Genetic and Cell-Mediated Therapies for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. In: Laurence J, Franklin M, editors. Translating Gene Therapy to the Clinic. Boston: Academic Press; 2015. p. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker RG, Poggioli T, Katsimpardi L, et al. Biochemistry and Biology of GDF11 and Myostatin: Similarities, Differences, and Questions for Future Investigation. Circ Res. 2016. Apr 1;118(7):1125–41; discussion 1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frohlich J, Vinciguerra M. Candidate rejuvenating factor GDF11 and tissue fibrosis: friend or foe? Geroscience. 2020. Dec;42(6):1475–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guignabert C, Humbert M. Targeting transforming growth factor-beta receptors in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2021. Feb;57(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassoun PM. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;385(25):2361–2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmierer B, Hill CS. TGFβ–SMAD signal transduction: molecular specificity and functional flexibility. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007 2007/December/01;8(12):970–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massagué J TGFβ signalling in context. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012 2012/October/01;13(10):616–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill CS. Transcriptional Control by the SMADs. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016. Oct 3;8(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyazawa K, Miyazono K. Regulation of TGF-β Family Signaling by Inhibitory Smads. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017. Mar 1;9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rol N, Kurakula KB, Happe C, et al. TGF-beta and BMPR2 Signaling in PAH: Two Black Sheep in One Family. Int J Mol Sci. 2018. Aug 31;19(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tielemans B, Delcroix M, Belge C, et al. TGFβ and BMPRII signalling pathways in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Drug Discov Today. 2019. Mar;24(3):703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyle MA, Fenstad ER, McGoon MD, et al. Pulmonary Hypertension in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Chest. 2016. Feb;149(2):362–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trembath RC, Thomson JR, Machado RD, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic features of pulmonary hypertension in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 2001. Aug 2;345(5):325–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humbert M, McLaughlin V, Gibbs JSR, et al. Sotatercept for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021. Apr 1;384(13):1204–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yung LM, Yang P, Joshi S, et al. ACTRIIA-Fc rebalances activin/GDF versus BMP signaling in pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 2020. May 13;12(543). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiepen C, Jatzlau J, Hildebrandt S, et al. BMPR2 acts as a gatekeeper to protect endothelial cells from increased TGFβ responses and altered cell mechanics. PLoS Biol. 2019. Dec;17(12):e3000557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tielemans B, Stoian L, Gijsbers R, et al. Cytokines trigger disruption of endothelium barrier function and p38 MAP kinase activation in BMPR2-silenced human lung microvascular endothelial cells. Pulm Circ. 2019. Oct-Dec;9(4):2045894019883607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton VJ, Ciuclan LI, Holmes AM, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor II regulates pulmonary artery endothelial cell barrier function. Blood. 2011. Jan 6;117(1):333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Ruiz I Sotatercept therapy for PAH. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021. Jun;18(6):386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang P, Bocobo GA, Yu PB. Sotatercept for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021. Jul 1;385(1):92–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aykul S, Martinez-Hackert E. Transforming Growth Factor-β Family Ligands Can Function as Antagonists by Competing for Type II Receptor Binding. J Biol Chem. 2016. May 13;291(20):10792–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joshi SR, Liu J, Bloom T, et al. Sotatercept analog suppresses inflammation to reverse experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. Scientific Reports. 2022 2022/May/12;12(1):7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verma A, Suragani RN, Aluri S, et al. Biological basis for efficacy of activin receptor ligand traps in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Invest. 2020. Feb 3;130(2):582–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Komrokji RS. Activin Receptor II Ligand Traps: New Treatment Paradigm for Low-Risk MDS. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2019. Aug;14(4):346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sako D, Grinberg AV, Liu J, et al. Characterization of the ligand binding functionality of the extracellular domain of activin receptor type IIb. J Biol Chem. 2010. Jul 2;285(27):21037–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cappellini MD, Porter J, Origa R, et al. Sotatercept, a novel transforming growth factor beta ligand trap, improves anemia in beta-thalassemia: a phase II, open-label, dose-finding study. Haematologica. 2019. Mar;104(3):477–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pilo F, Angelucci E. Luspatercept to treat beta-thalassemia. Drugs Today (Barc). 2020. Jul;56(7):447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farrukh F, Chetram D, Al-Kali A, et al. Real-world experience with luspatercept and predictors of response in myelodysplastic syndromes with ring sideroblasts. Am J Hematol. 2022. Mar 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan O, Komrokji RS. Luspatercept in the treatment of lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Future Oncol. 2021. Apr;17(12):1473–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Humbert M, McLaughlin V, Gibbs JSR, et al. Sotatercept for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: PULSAR open-label extension. European Respiratory Journal. 2022:2201347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Preston IR, Badesch D, Ghofrani HA, et al. Abstract 10188: Sotatercept Phase 3 Program Design and Rationale: A Novel Treatment for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circulation. 2021;144(Suppl_1):A10188–A10188. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sherman ML, Borgstein NG, Mook L, et al. Multiple-dose, safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of sotatercept (ActRIIA-IgG1), a novel erythropoietic agent, in healthy postmenopausal women. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013. Nov;53(11):1121–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.David L, Mallet C, Mazerbourg S, et al. Identification of BMP9 and BMP10 as functional activators of the orphan activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) in endothelial cells. Blood. 2007. Mar 1;109(5):1953–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Upton PD, Davies RJ, Trembath RC, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and activin type II receptors balance BMP9 signals mediated by activin receptor-like kinase-1 in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2009. Jun 5;284(23):15794–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li W, Salmon RM, Jiang H, et al. Regulation of the ALK1 ligands, BMP9 and BMP10. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016. Aug 15;44(4):1135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salmon RM, Guo J, Wood JH, et al. Molecular basis of ALK1-mediated signalling by BMP9/BMP10 and their prodomain-bound forms. Nature Communications. 2020 2020/April/01;11(1):1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nikolic I, Yung LM, Yang P, et al. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 9 Is a Mechanistic Biomarker of Portopulmonary Hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019. Apr 1;199(7):891–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Long L, Ormiston ML, Yang X, et al. Selective enhancement of endothelial BMPR-II with BMP9 reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Med. 2015. Jul;21(7):777–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Long L, Ormiston ML, Yang X, et al. Selective enhancement of endothelial BMPR-II with BMP9 reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nature Medicine. 2015 2015/July/01;21(7):777–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ormiston ML, Upton PD, Li W, et al. The promise of recombinant BMP ligands and other approaches targeting BMPR-II in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2015;2015(4):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meng L, Teng X, Liu Y, et al. Vital Roles of Gremlin-1 in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Induced by Systemic-to-Pulmonary Shunts. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020. Aug 4;9(15):e016586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ciuclan L, Sheppard K, Dong L, et al. Treatment with anti-gremlin 1 antibody ameliorates chronic hypoxia/SU5416-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice. Am J Pathol. 2013. Nov;183(5):1461–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ormiston ML, Godoy RS, Chaudhary KR, et al. The Janus Faces of Bone Morphogenetic Protein 9 in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circ Res. 2019. Mar 15;124(6):822–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tu L, Desroches-Castan A, Mallet C, et al. Selective BMP-9 Inhibition Partially Protects Against Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ Res. 2019. Mar 15;124(6):846–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morrell NW, Upton PD, Li W, et al. Letter by Morrell et al Regarding Article, “Selective BMP-9 Inhibition Partially Protects Against Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension”. Circ Res. 2019. Apr 26;124(9):e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guignabert C, Tu L, Feige JJ, et al. Response by Guignabert et al to Letter Regarding Article, “Selective BMP-9 Inhibition Partially Protects Against Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension”. Circ Res. 2019. Apr 26;124(9):e82–e83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Long L, Ormiston ML, Yang X, et al. Selective enhancement of endothelial BMPR-II with BMP9 reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Med. 2015. Jul;21(7):777–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Valdimarsdottir G, Goumans MJ, Rosendahl A, et al. Stimulation of Id1 expression by bone morphogenetic protein is sufficient and necessary for bone morphogenetic protein-induced activation of endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002. Oct 22;106(17):2263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arnold ND, Pickworth JA, West LE, et al. A therapeutic antibody targeting osteoprotegerin attenuates severe experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Commun. 2019. Nov 15;10(1):5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luan X, Lu Q, Jiang Y, et al. Crystal structure of human RANKL complexed with its decoy receptor osteoprotegerin. J Immunol. 2012. Jul 1;189(1):245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Emery JG, McDonnell P, Burke MB, et al. Osteoprotegerin is a receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. J Biol Chem. 1998. Jun 5;273(23):14363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsuda E, Goto M, Mochizuki S, et al. Isolation of a novel cytokine from human fibroblasts that specifically inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997. May 8;234(1):137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lawrie A, Waterman E, Southwood M, et al. Evidence of a role for osteoprotegerin in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Pathol. 2008. Jan;172(1):256–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jia D, Zhu Q, Liu H, et al. Osteoprotegerin Disruption Attenuates HySu-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Through Integrin alphavbeta3/FAK/AKT Pathway Suppression. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017. Feb;10(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arnold ND, Pickworth JA, West LE, et al. A therapeutic antibody targeting osteoprotegerin attenuates severe experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nature Communications. 2019 2019/November/15;10(1):5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lawrie1 NDA A, Pickworth1 JA, West1 LE, Papworth2 J, Germaschewski3 V, Thompson1 AAR, Francis SE The Anti-Osteoprotegerin (OPG) Antibody Ky3 Attenuates OPG-Fas Mediated Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation, Migration and Pro-Inflammatory Signalling In Vitro and In Vivo. American Thoracic Society International Conference Abstracts ATS Journals; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maguire JJ, Davenport AP. Endothelin receptors and their antagonists. Semin Nephrol. 2015. Mar;35(2):125–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang C, Wang X, Zhang H, et al. Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibody Antagonizing Endothelin Receptor A for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019. Jul;370(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Davenport AP, Hyndman KA, Dhaun N, et al. Endothelin. Pharmacological reviews. 2016;68(2):357–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dai Y, Chen X, Song X, et al. Immunotherapy of Endothelin-1 Receptor Type A for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019. May 28;73(20):2567–2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dai Y, Qiu Z, Ma W, et al. Long-Term Effect of a Vaccine Targeting Endothelin-1 Receptor Type A in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:683436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stenmark KR, Rabinovitch M. Emerging therapies for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010. Mar;11(2 Suppl):S85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saga T, Said SI. Vasoactive intestinal peptide relaxes isolated strips of human bronchus, pulmonary artery, and lung parenchyma. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1984;97:304–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maruno K, Absood A, Said SI. VIP inhibits basal and histamine-stimulated proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1995. Jun;268(6 Pt 1):L1047–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Petkov V, Mosgoeller W, Ziesche R, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide as a new drug for treatment of primary pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003. May;111(9):1339–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Said SI, Dickman KG. Pathways of inflammation and cell death in the lung: modulation by vasoactive intestinal peptide. Regul Pept. 2000. Sep 25;93(1–3):21–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Montani D, Chaumais MC, Guignabert C, et al. Targeted therapies in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pharmacol Ther. 2014. Feb;141(2):172–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Said SI, Hamidi SA, Dickman KG, et al. Moderate pulmonary arterial hypertension in male mice lacking the vasoactive intestinal peptide gene. Circulation. 2007. Mar 13;115(10):1260–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Said SI. The vasoactive intestinal peptide gene is a key modulator of pulmonary vascular remodeling and inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008. Nov;1144:148–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Szema AM, Hamidi SA, Lyubsky S, et al. Mice lacking the VIP gene show airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation, partially reversible by VIP. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006. Nov;291(5):L880–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hamidi SA, Lin RZ, Szema AM, et al. VIP and endothelin receptor antagonist: An effective combination against experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respiratory Research. 2011 2011/December/01;12(1):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mathioudakis A, Chatzimavridou-Grigoriadou V, Evangelopoulou E, et al. Vasoactive intestinal Peptide inhaled agonists: potential role in respiratory therapeutics. Hippokratia. 2013. Jan;17(1):12–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sumita Paul M MPH, FACC1, Raymond L Benza MD, FACC2, Murali Chakinala MD3, Priscilla Correa4 MD, Kalyan Ghosh1 PhD, John Lee1 MD, PhD, and James White5 MD. Safety, Tolerability, and Changes in Six-Minute Walk Test After Open-Label Subcutaneous PB1046, A Sustained-Release Analogue for Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP), in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) 2021. Available from: https://phasebio.com/wp-content/uploads/7c6186b77b2c-2021_PVRI_Poster.pdf

- 95.Steve T Yeh BLY, Lynne Georgopoulos, Sue Arnold, Robert L Hamlin and Carlos L del Rio. Novel Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide-ELP Fusion Protein VPAC-Agonists Trigger Sustained Pulmonary Artery Vaso-Relaxation in Rats with Acute Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Spiekerkoetter E, Kawut SM, de Jesus Perez VA. New and Emerging Therapies for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Annu Rev Med. 2019. Jan 27;70:45–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhao YD, Courtman DW, Deng Y, et al. Rescue of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension using bone marrow-derived endothelial-like progenitor cells: efficacy of combined cell and eNOS gene therapy in established disease. Circ Res. 2005. Mar 4;96(4):442–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sitbon O, Gomberg-Maitland M, Granton J, et al. Clinical trial design and new therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019. Jan;53(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grinnan D, Trankle C, Andruska A, et al. Drug repositioning in pulmonary arterial hypertension: challenges and opportunities. Pulm Circ. 2019. Jan-Mar;9(1):2045894019832226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Prins KW, Thenappan T, Weir EK, et al. Repurposing Medications for Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: What’s Old Is New Again. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019 2019/January/08;8(1):e011343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Toshner M, Church AC, Harlow L, et al. Transform-UK: A Phase 2 Trial of Tocilizumab in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. D108. GOOD VIBRATIONS: NOVEL TREATMENT APPROACHES IN PULMONARY HYPERTENSION. American Thoracic Society International Conference Abstracts: American Thoracic Society; 2018. p. A7804–A7804. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Steiner MK, Syrkina OL, Kolliputi N, et al. Interleukin-6 overexpression induces pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2009. Jan 30;104(2):236–44, 28p following 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tamura Y, Phan C, Tu L, et al. Ectopic upregulation of membrane-bound IL6R drives vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2018. May 1;128(5):1956–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lavine K Blocking IL-6 signaling deflates pulmonary arterial hypertension. Science Translational Medicine. 2018. May/23;10:eaat8534. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Furuya Y, Satoh T, Kuwana M. Interleukin-6 as a potential therapeutic target for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Rheumatol. 2010;2010:720305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Toshner M, Church C, Harbaum L, et al. Mendelian randomisation and experimental medicine approaches to interleukin-6 as a drug target in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2022. Mar;59(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Oka M, Homma N, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, et al. Rho kinase-mediated vasoconstriction is important in severe occlusive pulmonary arterial hypertension in rats. Circ Res. 2007. Mar 30;100(6):923–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nagaoka T, Fagan KA, Gebb SA, et al. Inhaled Rho kinase inhibitors are potent and selective vasodilators in rat pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. Mar 1;171(5):494–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fukumoto Y, Yamada N, Matsubara H, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial with a rho-kinase inhibitor in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ J. 2013;77(10):2619–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ahsan F Microfluidic device for recapitulating PAH-afflicted pulmonary artery: design, fabrication, and on-chip cell culture. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sarkar T, Nguyen T, Moinuddin SM, et al. A Protocol for Fabrication and on-Chip Cell Culture to Recreate PAH-Afflicted Pulmonary Artery on a Microfluidic Device. Micromachines. 2022;13(9):1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sutendra G, Michelakis ED. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: challenges in translational research and a vision for change. Sci Transl Med. 2013. Oct 23;5(208):208sr5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Toshner M, Rothman A. IL-6 in pulmonary hypertension: why novel is not always best. Eur Respir J. 2020. Apr;55(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Geigert J Complexity of Biologics CMC Regulation. The Challenge of CMC Regulatory Compliance for Biopharmaceuticals: Springer; 2019. p. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Geigert J Biologics are not chemical drugs. The Challenge of CMC Regulatory Compliance for Biopharmaceuticals and Other Biologics: Springer; 2013. p. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Geigert J Challenge of adventitious agent control. The Challenge of CMC Regulatory Compliance for Biopharmaceuticals and Other Biologics: Springer; 2013. p. 59–104. [Google Scholar]