Abstract

Objective

A behavioral medicine approach, incorporating a biopsychosocial view and behavior change techniques, is recommended in physical therapy for the management of musculoskeletal pain. However, little is known about physical therapists’ actual practice behavior regarding the behavioral medicine approach. The aim of this study was to examine how physical therapists in primary health care judge their own practice behavior of a behavioral medicine approach in the assessment and treatment of patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain versus how they practice a behavioral medicine approach as observed by independent experts in video recordings of patient consultations.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted. Video recordings of 23 physical therapists’ clinical behavior in 139 patient consultations were observed by independent experts and compared with the physical therapists’ self-reported practice behavior, using a protocol including 24 clinical behaviors. The difference between observed and self-reported clinical behaviors was analyzed with a Chi-square test and a Fisher exact test.

Results

The behavioral medicine approach was, in general, practiced to a small extent and half of the self-reported clinical behaviors were overestimated when compared with the observed behaviors. According to the observations, the physical perspective dominated in assessment and treatment, the functional behavioral analysis was never performed, and the mean number of behavior change techniques used was 0.7.

Conclusion

There was a discrepancy between how physical therapists perceived the extent to which they practiced a behavioral medicine approach in their clinical behavior compared with what the independent researchers observed in the video recordings.

Impact

This study demonstrates the importance of using observations instead of using self-reports when evaluating professionals’ clinical behavior. The results also suggest that—to ensure that physical therapy integrates the biopsychosocial model of health—physical therapists need to increase their focus on psychosocial factors in clinical practice.

Keywords: Behavior, Biopsychosocial, Clinical Practice, Observation, Physical Therapy, Self-Report

Introduction

Traditionally, physical therapists have a biomedical approach in patient assessment and treatment. However, there is evidence for beneficial effects such as reduced disability and pain when a biopsychosocial approach is used for patients with musculoskeletal pain.1–4 There is also evidence for increased exercise participation if specific behavior change techniques such as goalsetting, graded tasks, and self-monitoring are used.5,6 A behavioral medicine approach, incorporating a biopsychosocial view and the use of behavior change techniques in physical therapy, is therefore recommended to be implemented for the management of musculoskeletal pain.7,8

Behavioral medicine is based on a biopsychosocial model of health and integrates health-related behavioral, psychosocial, and biomedical knowledge to health promotion, assessment, and treatment.9 In physical therapy, for the management of musculoskeletal pain, psychosocial factors refer to patient’s beliefs about the nature of pain, fear, pain catastrophizing, self-efficacy, social interactions, and contextual factors that influence behavioral responses.7 The biomedical factors refer to the patient’s physical conditions and anatomical dysfunctions. The physical therapist assessment needs to screen for potential obstacles for performing daily activities within the biopsychosocial spectra by asking about the patient’s thoughts and emotions, and social and contextual obstacles, and in treatment the identified obstacles need to be addressed. The treatment goal is to improve the patients’ functionality in the presence of pain.3 A functional behavioral analysis, derived from operant learning theory and social cognitive theory, is a method used to determine biomedical, psychological, and contextual factors of importance for goal attainment.10 In a functional behavioral analysis, the pain problem is defined in behavioral terms, and the functional relationships between biopsychosocial factors are identified and discussed with the patient.11–13 To support patients’ behavior change, behavior change techniques are used such as goalsetting, graded tasks, self-monitoring, problem solving, and feedback on behavior.5,6,14,15 Yet, research shows that the implementation of the behavioral medicine approach in clinical practice is challenging.16–19

Research shows that physical therapists currently have positive attitudes toward a psychosocial approach in physical therapy.16–19 However, the confidence and necessary skills for addressing a psychosocial approach seem to be lacking.16,18–21 Despite training in the behavioral medicine approach, only changes in physical therapists’ knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes occur22–24 and temporary changes in their clinical practice.25 In studies investigating physical therapists practice of a behavioral medicine approach in physical therapy, practice behavior is often measured indirectly as “perceived use”16–18,21,22 or underreported.26 The few studies that objectively measured the physical therapists’ actual practice behavior indicate that the biomedical approach still dominates in clinical practice.11,27,28 However, the results are based on a small number of observed patient consultations and mostly initial consultations.

Thus, little is known about the physical therapists’ actual practice behavior regarding the behavioral medicine approach. Therefore, there is still a need to investigate which parts of the behavioral medicine approach that physical therapists nowadays use in clinical practice and which parts that need to be implemented more. The aim of this study was therefore to examine how physical therapists in primary health care judge their own practice behavior of a behavioral medicine approach in the assessment and treatment of patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain, with how they practice a behavioral medicine approach as observed by independent experts in video recordings of actual patient consultations.

Methods

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement for cohort studies was used to report this study.29

Design

A prospective cohort study was conducted.

Participants and Settings

All physical therapists working in primary health care in 3 regions of similar sizes located in the middle of Sweden were asked to participate in a study to implement behavioral medicine in clinical practice. Twenty-four physical therapists working at 14 different primary health care units showed interest and were included in the study. One of the physical therapists changed workplace and was therefore excluded before the study began. The characteristics of the physical therapists are described in Table 1. Most of the physical therapists (19/23) had previous training concerning the behavioral medicine approach, such as motivational interviewing or university courses in behavioral medicine for physical therapists. The physical therapists were offered active or passive support to learn the behavioral medicine approach. A clinical behavior change was identified immediately after the period of active learning support, but the changes were not maintained at follow-ups. Since there were no significant differences regarding the extent to which the physical therapists in the 2 groups practiced the behavior medicine approach at baseline according to the observations, and the support had no impact on the physical therapists’ clinical behaviors at follow-ups for any of the groups,25 the groups were combined into 1 in this study. Participation was voluntary, and all participants gave written informed consent after receiving oral and written information. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr 2015/385).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Physical Therapists Participants (N = 23)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex, reported as male (M) or female (F) | M = 8, F = 15 |

| Age, y, median (minimum–maximum) | 37 (23–63) |

| Years of work as a physical therapist, median (minimum–maximum) | 8 (0.5–30) |

| Years of work in primary health care, median (minimum–maximum) | 3 (0.5–19) |

Data Collection

To collect data concerning the physical therapists’ clinical behavior, the physical therapists’ behavioral medicine–related clinical behaviors were investigated via observation and self-report. Patient consultations were video recorded by 2 researchers. To obtain as accurate a description as possible of the behavioral medicine–related content of the patient consultations, several patient consultations (both initial consultations and follow-up consultations) per physical therapist were video recorded. Data were collected during 12 months in 2016 to 2017 as part of an implementation study described elsewhere.25 Data collected at baseline and at follow-ups were included since the learning support had no effect on the physical therapists’ clinical behaviors at follow-ups as previously mentioned.25 Observations performed before and after the learning support therefore did not need to be separated in this study. The video recordings were observed and reviewed by 3 independent experts using an observation protocol. The experts were blinded to initial/follow-up consultations. The observation protocol was study specific and consisted of 58 observable clinical behaviors assessed as present/not present. In this study, several of these observable behaviors have been merged (for example “encouraging self-monitoring of target behavior” consisted of 5 clinical behaviors that have been merged into 1) to 24 observable clinical behaviors forming the basis for the results in this study in relation to 4 main areas: Focusing behaviors of importance for performing activities in daily life; biopsychosocial focus in assessment and treatment; individual functional behavioral analysis; and behavior change techniques applied to physical therapy (see Suppl. Appendix 1 for details). The experts only noticed what was observed and made no suggestions of how the physical therapists should have acted. The content of the patient consultations was also self-reported by the physical therapists in a protocol identical to the observation protocol used by the experts. All data in the protocols were deidentified. Intrarater reliability for the observation protocol was evaluated on 4 observers and analyzed with the Cohen κ. The results showed substantial agreement; the κ value for the 7 components ranged between 0.6 and 0.9. The highest agreement between the first and second observations was found for goal setting (κ = 0.9), and the lowest agreement was found for assessment of target behavior (κ = 0.6).

Data Analyses

Data regarding the extent to which each clinical behavior were present in the video recordings or self-reported by the physical therapists were presented as a number and a percentage. The difference between observed and self-reported clinical behaviors was analyzed with a χ2 test, a Fisher exact test when n < 5, and a paired t test. The significance level was set at P ≤ .05. The magnitude of the differences analyzed with a χ2 square test was analyzed with phi coefficient, where ϕ = 0.10 represented a small effect, ϕ = 0.30 represented a moderate effect, and ϕ = 0.50 represented a large effect. The magnitude of the differences analyzed with paired t test was analyzed with the Cohen d, where d = 0.20 represented a small effect, d = 0.50 represented a moderate effect, and d = 0.80 represented a large effect.30 IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 28 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), was used for all analyses.

Role of the Funding Source

The funder played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Results

Twenty-three physical therapists participated, and 139 patient consultations were video recorded and self-rated. Each physical therapist contributed a median of 6 video-recorded patient consultations (minimum–maximum = 2–8); 70 recordings were initial consultations, and 69 recordings were follow-ups.

Focusing Behaviors of Importance for Performing Activities in Daily Life

The results showed that discussions about activities in daily life that the patients had difficulties performing due to pain, was observed and self-reported in a majority of the patient consultations (Tab. 2). Any further assessment or follow-up of the target behavior (ie, asking or observing a prioritized target behavior), or applied skills acquisition of these daily activities (ie, encouraging practice of merged basic skills to form more complex behaviors in daily life situations) was observed in only a fraction of the patient consultations but self-reported to a higher extent (Tab. 2). Significant differences between observed and self-reported clinical behaviors were identified related to 3 of 4 clinical behaviors, and the magnitudes of the differences were small (Tab. 2).

Table 2.

Observed and Self-Reported Patient Consultations That Included Physical Therapists’ Clinical Behaviors Focusing on Activities in Daily Life

| Clinical Behavior | No. (%) | Difference (χ 21) (N = 278) | P | Magnitude (ϕ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Self-Reported | ||||

| Discussing activities in daily life that the patient had difficulties performing due to pain | 108 (77.7) | 106 (76.3) | 0.08 | .78 | 0.02 |

| Assessment of target behavior (asking, observing) | 12 (8.6) | 61 (43.9) | 44.60 | <.001 | 0.04 |

| Applied skills acquisition (basic skills that are merged and practiced to form more complex behaviors in everyday life situations) | 13 (9.4) | 26 (18.7) | 5.04 | .03 | 0.14 |

| Follow-up of the target behavior (asking, observing) | 11 (7.9) | 32 (23.0) | 12.13 | <.001 | 0.21 |

The Biopsychosocial Focus in Assessment and Treatment

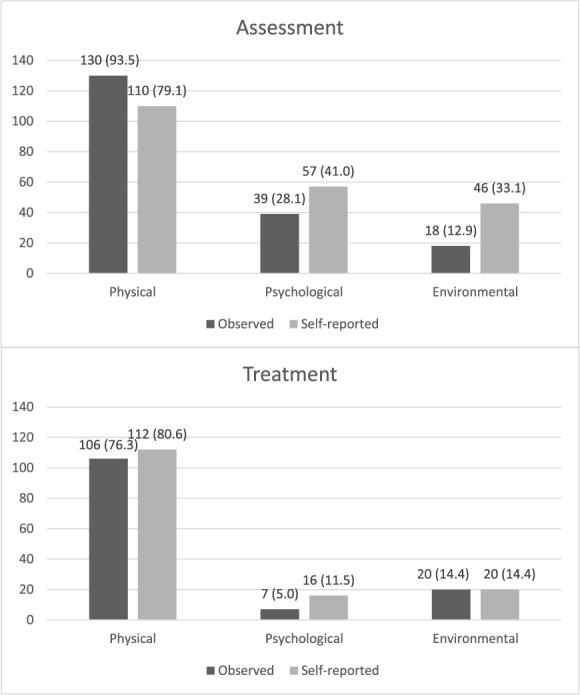

The physical perspective was the most common in both assessment and treatment (Figure). Significant differences between observed and self-reported clinical behaviors were identified related to 4 of 6 clinical behaviors and the magnitudes of the differences were small (Tab. 3). A discussion between the patient and the physical therapist of a reasonable dosage of the exercises was observed in 62 (44.6%) of the patient consultations and self-reported in 70 (50.4%) of the patient consultations. No significant difference was found between the numbers of observed and self-reported clinical behaviors related to the discussion about dosage (χ21 = 0.92 [N = 278]; P = .34; ϕ = 0.06).

Figure.

Numbers and percentages (in parentheses) of observed and self-reported patient consultations (N = 139) that included physical, psychological, and environmental perspectives in assessment and treatment.

Table 3.

Observed and Self-Reported Clinical Behaviors Related to Biopsychosocial Factors in Assessment and Treatment

| Clinical Behavior | Difference (χ 2 1 ) (N = 278) | P | Magnitude (ϕ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | |||

| Physical | 13.15 | <.001 | 0.22 |

| Psychological | 5.72 | .02 | 0.14 |

| Environmental | 15.91 | <.001 | 0.24 |

| Treatment | |||

| Physical | 0.77 | .38 | 0.05 |

| Psychological | 3.84 | .05 | 0.12 |

| Environmental | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

Individual Functional Behavioral Analysis

A complete individual functional behavioral analysis including physical, psychological, and environmental factors was never performed. In 13 (9.4%) of the observations, factors of importance for the pain-related behavioral problem were discussed with the patient. However, in these cases, the analysis involved only physical factors rather than the relationship among physical, psychological, and environmental factors (Tab. 4). Significant differences between observed and self-reported clinical behaviors related to individual functional behavioral analysis were identified, and the magnitudes of the differences were moderate (Tab. 4).

Table 4.

Observed and Self-Reported Patient Consultations That Included Physical Therapists’ Clinical Behaviors Related to Individual Functional Behavioral Analysis (FBA)

| Clinical Behavior | No. (%) | Difference (χ 2 1 ) (N = 278) | P | Magnitude (ϕ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Self-Reported | ||||

| FBA involving physical factors | 10 (7.2) | 54 (38.8) | 40.66 | <.001 | 0.38 |

| FBA involving psychological factors | 1 (0.7) | 31 (22.3) | 33.04 | <.001 | 0.35 |

| FBA involving environmental factors | 2 (1.4) | 29 (20.9) | 26.47 | <.001 | 0.31 |

Behavior Change Techniques Applied to Physical Therapists

Behavior change techniques were used for different extents in the patient consultations (Tab. 5). Ten clinical behaviors were in focus which could be traced to 8 behavior change techniques. No significant differences between observed and self-reported clinical behaviors were identified for most techniques except for 1 part of problem solving and goal setting. The magnitudes of these differences were small (Tab. 5).

Table 5.

Observed and Self-Reported Patient Consultations That Included Different Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs)

| BCT | Application to Physical Therapy | No. (%) | Difference (χ 21) (N = 278) | P | Magnitude (ϕ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Self-Reported | |||||

| Social reward | External reinforcement by the physical therapist | 25 (18.0) | 30 (21.6) | 0.81 | .37 | 0.05 |

| Prompts/cues | Encouraging the use of reminders | 24 (17.3) | 31 (22.3) | 1.11 | .29 | 0.06 |

| Problem solving | Encouraging problem solving of barriers for exercise | 14 (10.1) | 11 (7.9) | 0.40 | .53 | 0.04 |

| Discussing relapse prevention | 4 (2.9) | 17 (12.2) | 8.81 | <.01 | 0.18 | |

| Self-monitoring of behavior | Encouraging and/or follow-up self-monitoring of exercise | 11 (7.9) | 6 (4.3) | 1.57 | .21 | 0.08 |

| Encouraging and/or follow-up regarding self-monitoring of target behavior | 8 (5.8) | 13 (9.4) | 1.25 | .26 | 0.07 | |

| Goal setting (outcome) | Discussing a specific and measurable goal | 8 (5.8) | 24 (17.3) | 9.04 | <.01 | 0.18 |

| Self-reward | Encouraging self-reinforcement | 3 (2.2) | 6 (4.3) | 1.03 | .31 | 0.06 |

| Generalization of target behavior | Encouraging generalization of target behavior or skills | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.4) | 0.20 | .65 | 0.03 |

| Reward approximation | Using shaping of rewards | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.2) | 1.02 | .31 | 0.06 |

According to the observations, the physical therapists applied a mean of 0.7 of the 10 clinical behaviors per patient consultation (minimum–maximum = 0–6; SD = 1.1). The mean self-reported application of these clinical behaviors was 1.1 per patient consultation (minimum–maximum = 0–5; SD = 1.2). There was a significant difference between the numbers of observed and self-reported clinical behaviors per patient consultation, and the magnitude was small (t138 = 3.12; P < .01; 2-tailed; d = 0.26). The physical therapists could alternate between 10 observed clinical behaviors related to behavior change techniques in focus during these patient consultations. When observed, they alternated a mean of 2.35 (minimum–maximum = 0–9; SD = 2.2) of the 10 observed clinical behaviors. The mean self-reported alternation of the same clinical behaviors was 3.52 (minimum–maximum = 0–9; SD = 2.0). There was a significant difference between observed and self-reported alternations of clinical behaviors related to behavior change techniques, and the magnitude was moderate (t22 = 2.13; P = .04; 2-tailed; d = 0.45).

Discussion

According to the results, the physical therapists only practiced the behavioral medicine approach to a small extent in actual patient consultations and there is an obvious small to moderate difference between observed and self-reported practice behavior. So, physical therapists perceive themselves using the behavioral medicine approach to a larger extent than what can be observed in the actual patient consultations. Even though the behavioral medicine approach is beneficial for increasing patient’s health,1–4 that is of little importance if the physical therapists do not use the behavioral medicine approach in their clinical practice.

The biopsychosocial model was first proposed in 1977.31 Since then, the model has been progressively adopted in health care and today the World Physiotherapy organization32 declare that physical therapists are focusing on physical, psychological, emotional, and social wellbeing when helping people. This declaration of physical therapy correlates with the description of physical therapy made by the Swedish professional association for physical therapy.33 However, if physical therapists would really practice a biopsychosocial approach, the physical, psychological, and environmental perspectives in assessment and treatment should be much higher than shown in the observations made by the independent researchers of the practice behavior in this study. Yet the physical therapists perceive their practice behavior to be much more biopsychosocial orientated than could be observed. There seems to be a clear discrepancy between what physical therapist perceive they do compared with what can be observed.

Although a biopsychosocial approach has been recommended for several years or even decades, the physical perspective still dominates among the physical therapists in the current study. According to previous research, physical therapists managing patients with musculoskeletal pain self-report that they routinely assess psychosocial factors overall, but rarely explicit assess psychological factors using for example questionnaires.34,35 It is possible that the discrepancy between observed and self-reported assessment of psychosocial factors in this study is caused by the physical therapists use of intuition and interpretation of psychosocial factors when interviewing patients. However, this can only apply to a minority of the cases since the psychosocial factors were also missing in the functional behavioral analysis and the treatment. A question worth considering is why physical therapists are very specific regarding assessment and treatment when focusing on physical factors, but more general regarding assessment and treatment when focusing on psychosocial factors? A possible explanation seems to be that physical therapists do not feel confident in managing psychosocial factors17,36 and need more training to do so.8,17,19,20 Time pressure also contributes to physical therapists having greater reliance on faster interpretation,37 which probably affects their efforts to assess psychosocial factors.

A functional behavioral analysis needs to include a pain problem defined in behavioral terms (eg, difficulties in coping with administrative computer work due to pain) and a discussion with the patient about the relationships of biopsychosocial factors of importance for the target behavior.11,13 No analysis met that requirement in our study. Only a few physical therapists analyzed a pain problem defined in behavioral terms, but then usually from a physical perspective. According to our results, the physical perspective dominated in the assessment, and the psychosocial perspectives were often missing. Thus, there were no target behavior or psychosocial factors to analyze. It is possible that the physical therapists in this study equate a functional behavioral analysis with a general pain analysis focusing on the biomedical causes of the pain. The discrepancy between observed and self-reported practice of the functional behavioral analysis could thus be explained by ignorance of the concept itself. An assessment of the physical therapists’ knowledge of the behavioral medicine approach could have contributed with important information and is recommended for future studies.

When using the behavioral medicine approach, behaviors of importance for performing activities in daily life should be in focus. According to the results, it seems that the physical therapists ask about how daily activities are affected by the pain, but they do not focus on a target behavior that can be assessed and treated in more detail. This general approach can contribute to the difficulties of performing an individual functional behavioral analysis and setting specific behavior goals. According to the observations, the physical therapists’ attempts to apply the behavioral medicine approach seem rather tentative. This general approach to the patients’ pain problem and the assessment of psychosocial factors could be a sign of the uncertainty and lack of the confidence and necessary skills for addressing a psychosocial approach.16,18–21

The mean number of behavior change techniques used by the physical therapists per patient consultation was 0.7. They alternated a mean of 2.35 different techniques. These are relatively few techniques used compared with other studies. Other studies reported a higher number of behavior change techniques used, varying from 3.5 to 11.5, depending on which group the physical therapists belonged to (intervention or control).5,6,14,38 Obviously, it is important to remember that there is a difference between what physical therapists do when they follow a protocol in a controlled trial, and what they do in actual patient consultations, as in the present study. Ideally, the use of behavior change techniques should be tailored to the patient based on the functional behavioral analysis39. This means that a physical therapist must be able to master several different behavior change techniques to be able to choose the most suitable for the patient in question. Thus, the amount of techniques used and the variation in use should be a measure of tailoring the treatment to the patient. Our results could be interpreted as that the physical therapists did not tailor the support for behavior change to the patient but used approximately the same techniques for all patients.

Awareness of own practice is a determinant for implementation40 that is really highlighted in these results. The results in the current study show a discrepancy between the observed and the self-reported practice of the behavioral medicine approach. Studies have reported increased knowledge of the behavioral medicine approach and changes in attitudes as results of implementation efforts,22–24 but the physical therapists’ awareness of their own practice in relation to the behavioral medicine approach is, to our knowledge, never evaluated. If the physical therapist think that they are using the behavioral medicine approach even though they are not, it will affect the motivation and the possibilities for the physical therapist to change behavior. Why is there a difference between the observed and the self-reported practice of the behavioral medicine approach? It is possible that the self-reported practice rather reflects the physical therapists’ attitudes, intentions, and wishes than their actual practice behavior. Studies have shown that physical therapists’ attitudes to the behavioral medicine approach are positive.25 However, there seems to be a gap between the intentions and what the physical therapists actually do during patient consultations.

Behavior change is a complex process that takes time.41 The process seems to start by changes in beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge.22–24 Even though the behavioral medicine approach only was practiced to a small extent by the physical therapists in our study, the stages in a behavior change process could have been highlighted by evaluating the physical therapists’ behavioral medicine knowledge. For deeper understanding of practice behavior and the behavior change process, we recommend future researcher to evaluate both attitudes, beliefs and knowledge, and practice behavior.

The physical therapists included in this study represent a selected sample of physical therapists that were interested in behavioral medicine and most of them were previously to some extent already educated in behavioral medicine. They received additional training during the original study25 in accordance with current research about the importance of skills training,8,19,20,22,36 active learning strategies including feedback on performance, mentored patient interactions and peer coaching,42,43 and the use of video recordings as a basis for feedback.44 Still their clinical practice included so little behavioral medicine according to the observations. The physical therapists’ practice behavior can therefore be considered comparable to physical therapists who have not received any additional training in behavioral medicine, because the training did not contribute to maintained practice behavior change. The result of this study raises many thoughts of why the implementation of the behavioral medicine approach was not more successful. However, the scope of this paper is to compare how physical therapists judge their own practice behavior, with observed practice behavior during actual patient consultations. This study only describes the physical therapists’ clinical practice. The discussion about the implementation of the behavioral medicine approach is not the scope of this paper and is already presented elsewhere.25,45 Still, it seems like the behavioral medicine approach is an extremely complicated intervention to implement in clinical practice, and we need to continue researching how best to support its implementation.

Strengths and Limitations

The greatest strength in this study is the fact that the data about the physical therapists’ clinical behavior are not only self-reported but also collected by observations of clinical behavior in a large number of actual patient consultations. Observation is considered a valid method for assessing performance.46 The patient consultations were video recorded to facilitate the observations. By allowing to review the consultations repeatedly, the video recordings enabled the observers to capture behaviors that occur simultaneously.43 The use of multiple observers increased the statistical power, but a limitation is that only intrarater reliability for the observation protocol was evaluated. The observers were blinded to initial and follow-up consultations to control for the observer expectancy effect. The observation protocol only evaluated the physical therapists’ clinical behavior as present/not present, without any qualitative interpretation of the performance. The broad criteria for “present” (Suppl. Appendix 1) generated a generous assessment of the presence of the behavioral medicine–related clinical behaviors in question. There may thus be room for improvement in identifying the behavioral medicine–related clinical behaviors in future studies. It could be of interest to further categorize the psychological factors in future studies, to clarify what kind of factors (eg, fear, pain catastrophizing, self-efficacy) are assessed most frequently.

When studying physical therapists’ clinical behavior, the results are often based on self-reported data.16–18,22–24 A limitation with self-reported data is the social desirability response bias and the respondent’s ability to properly remember what happened.44 To ensure the physical therapists’ memory, they were instructed to fill in the self-report during the same day as the actual patient consultation. It is also possible that part of the discrepancy between the observed and self-reported data is because of different understanding of the meaning of the components in the behavioral medicine approach, such as the functional behavioral analysis.

The results in the current study show that the behavioral approach was only used to a small extent in patient consultations and show a significant discrepancy between the observed and the self-reported practice of the behavioral medicine approach in half of the clinical behaviors in focus. In almost all these discrepancies, the self-reported behaviors were overestimated. Thus, the self-reported behavior gave an impression of a wider practice of the behavioral medicine approach than could actually be observed by the independent experts. This highlights the importance of examining clinical behavior with observations and not only self-reports.

Conclusions

The behavioral medicine approach was in general practiced to a small extent, and there was a discrepancy between how physical therapists perceived the extent to which they practiced a behavioral medicine approach in their clinical practice behavior compared with what the independent researchers observed in the video recordings. The self-reported practice was in general higher than the observed practice. There is no unambiguous answer as to why there was a difference between the observed and self-reported practice of the behavioral medicine approach or why the integration of a behavioral medicine approach in physical therapy was generally so low. One explanation of the difference can be that the self-reported practice seems to rather reflect the physical therapists’ intentions than their actual practice behavior.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Johanna Fritz, School of Health, Care and Social Welfare, Mälardalen University, Västerås, Sweden.

Thomas Overmeer, School of Health, Care and Social Welfare, Mälardalen University, Västerås, Sweden.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: J. Fritz, T. Overmeer

Data collection: J. Fritz, T. Overmeer

Data analysis: J. Fritz, T. Overmeer

Project management: J. Fritz, T. Overmeer

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): J. Fritz, T. Overmeer

Acknowledgment

The assistance provided by Maria Sandborgh with data collection is greatly appreciated.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Uppsala, Sweden, Dnr 2015/385.

Funding

This work was supported by AFA Insurance, Sweden (grant no. 12169).

Data Availability

The data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Hall A, Richmond H, Copsey B et al. Physiotherapist-delivered cognitive-behavioural interventions are effective for low back pain, but can they be replicated in clinical practice? A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Richmond H, Hall AM, Copsey B et al. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioural treatment for non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134192. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Pract. 2019;19:224–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:Cd007407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eisele A, Schagg D, Krämer LV, Bengel J, Göhner W. Behaviour change techniques applied in interventions to enhance physical activity adherence in patients with chronic musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meade LB, Bearne LM, Sweeney LH, Alageel SH, Godfrey EL. Behaviour change techniques associated with adherence to prescribed exercise in patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain: systematic review. Br J Health Psychol. 2019;24:10–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Main CJ, George SZ. Psychologically informed practice for management of low back pain: future directions in practice and research. Phys Ther. 2011;91:820–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foster NE, Delitto A. Embedding psychosocial perspectives within clinical management of low back pain: integration of psychosocially informed management principles into physical therapist practice—challenges and opportunities. Phys Ther. 2011;91:790–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. International Society of Behavioural Medicine . ISBM Charter [Web page]. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.isbm.info/about-isbm/charter.

- 10. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Emilson C, Åsenlöf P, Pettersson S et al. Physical therapists’ assessments, analyses and use of behavior change techniques in initial consultations on musculoskeletal pain: direct observations in primary health care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haynes SN, Leisen MB, Blaine DD. Design of individualized behavioral treatment programs using functional analytic clinical case models. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:334–348. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Åsenlöf P, Denison E, Lindberg P. Individually tailored treatment targeting motor behavior, cognition, and disability: 2 experimental single-case studies of patients with recurrent and persistent musculoskeletal pain in primary health care. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1061–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bishop FL, Fenge-Davies AL, Kirby S, Geraghty AWA. Context effects and behaviour change techniques in randomised trials: a systematic review using the example of trials to increase adherence to physical activity in musculoskeletal pain. Psychol Health. 2015;30:104–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Driver C, Kean B, Oprescu F, Lovell GP. Knowledge, behaviors, attitudes and beliefs of physiotherapists towards the use of psychological interventions in physiotherapy practice: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:2237–2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Driver C, Lovell GP, Oprescu F. Physiotherapists’ views, perceived knowledge, and reported use of psychosocial strategies in practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37:135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gray H, Howe T. Physiotherapists’ assessment and management of psychosocial factors (yellow and blue flags) in individuals with back pain. Phys Ther Rev. 2013;18:379–394. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sanders T, Foster N, Bishop A, Ong BN. Biopsychosocial care and the physiotherapy encounter: physiotherapists' accounts of back pain consultations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Synnott A, O’keeffe M, Bunzli S et al. Physiotherapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2015;61:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alexanders J, Anderson A, Henderson S. Musculoskeletal physiotherapists’ use of psychological interventions: a systematic review of therapists’ perceptions and practice. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Overmeer T, Boersma K, Main CJ, Linton SJ. Do physical therapists change their beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, skills and behaviour after a biopsychosocially orientated university course? J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:724–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sandborgh M, Åsenlöf P, Lindberg P, Denison E. Implementing behavioural medicine in physiotherapy treatment. Part II: adherence to treatment protocol. Adv Physiother. 2010;12:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stevenson K, Lewis M, Hay E. Does physiotherapy management of low back pain change as a result of an evidence-based educational programme? J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fritz J, Wallin L, Soderlund A, Almqvist L, Sandborgh M. Implementation of a behavioral medicine approach in physiotherapy: impact and sustainability. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42:3467–3474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simpson P, Holopainen R, Schütze R et al. Training of physical therapists to deliver individualized biopsychosocial interventions to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: a scoping review. Phys Ther. 2021;101:pzab188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Demmelmaier I, Denison E, Lindberg P, Åsenlöf P. Physiotherapists' telephone consultations regarding back pain: a method to analyze screening of risk factors. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010;26:468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Green AJ, Jackson DA, Klaber Moffett JA. An observational study of physiotherapists’ use of cognitive-behavioural principles in the management of patients with back pain and neck pain. Physiotherapy. 2008;94:306–313. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13:S31–S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Field A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock 'n' Roll. 4th ed. Los Angeles London: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Physiotherapy . What is Physiotherapy? [Web page]. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://world.physio/resources/what-is-physiotherapy.

- 33. Fysioterapeuterna . Fysioterapi. Profession och vetenskap. 2019. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.fysioterapeuterna.se/globalassets/professionsutveckling/om-professionen/fysioterapi-webb-navigering-20190220.pdf.

- 34. Man I, Kumar S, Jones M, Edwards I. An exploration of psychosocial practice within private practice musculoskeletal physiotherapy: a cross-sectional survey. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019;43:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hallegraeff J, Van Zweden L, Oostendorp RAB, van Trijffel E. Psychological assessments by manual physiotherapists in the Netherlands in patients with non-specific low back pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2021;29:310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fritz J, Söderbäck M, Söderlund A, Sandborgh M. The complexity of integrating a behavioral medicine approach into physiotherapy clinical practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35:1182–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Langridge N, Roberts L, Pope C. The clinical reasoning processes of extended scope physiotherapists assessing patients with low back pain. Man Ther. 2015;20:745–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28:690–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lally P, van Jaarsveld CHM, Potts HWW, Wardle J. How are habits formed: modelling habit formation in the real world. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2010;40:998–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leahy E, Chipchase L, Calo M, Blackstock FC. Which learning activities enhance physical therapist practice? Part 2: systematic review of qualitative studies and thematic synthesis. Phys Ther. 2020;100:1484–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leahy E, Chipchase L, Calo M, Blackstock FC. Which learning activities enhance physical therapist practice? Part 1: systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative studies. Phys Ther. 2020;100:1469–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Asan O, Montague E. Using video-based observation research methods in primary care health encounters to evaluate complex interactions. J Innov Health Inform. 2014;21:161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fritz J, Wallin L, Söderlund A, Almqvist L, Sandborgh M. Implementation of a behavioural medicine approach in physiotherapy: a process evaluation of facilitation methods. Implement Sci. 2019;14:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abernethy M. Self-reports and observer reports as data generation methods: an assessment of issues of both methods. Univers J Psychol. 2015;3:22–27. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.