Abstract

The article examines how nonprofit organization staff navigate organizational mission as they encounter complex systems problems outside their area of expertise, focusing on environmental organizations encountering homelessness in river watersheds. Drawing on surveys from seventy-three individuals from forty-three organizations and interviews with seventeen nonprofit staff, I find that staff who demonstrate systems thinking are more likely to describe integrating complex systems problems into their mission and activities in meaningful ways. Not interacting with systems issues due to lack of skill is most often explained with language of mission adherence and avoiding mission drift.

Keywords: Systems thinking, Mission drift, Homelessness, Environment, Organizational mission

Introduction

Many challenging global problems are complex systems problems (Meadows, 2008, Miller & Page, 2007, Renger, 2022, Stroh, 2015, Zellner & Campbell, 2015). In many contexts, change makers in nonprofit organizations will find problems they are committed to addressing that are inextricably linked to other problems with which they have limited experience. Experts on complex systems like Stroh (2015) recommend using systems thinking to reveal underlying causes of chronic, complex problems and identify high-impact interventions. Effectively solving complex problems requires a breadth of knowledge, activity, and divergent thinking that exhausts all possibilities (Chevallier, 2016). Yet nonprofit experts emphasize the role of mission in nonprofit organizations (e.g., Berlan, 2018, Kirk et al., 2010, Min et al., 2019, Sanders, 2015, Skaggs, 2020, Sloan, 2021, Young et al., 2009), and risks of mission creep or drift (e.g., Beaton, 2021; Grimes et al., 2019; Jones, 2007; Ma et al., 2017) when one deviates from specialist knowledge and singularity of focus and action. As nonprofit organizations grapple with complex systems problems, should they be cautioned against straying from their organizational mission? Or does considering complex systems problems (e.g., Meadows, 2008; Miller & Page, 2007; Stroh, 2015, Zellner & Campbell, 2015) and engaging in systems thinking (Stroh, 2015) and effective complex problem solving (Chevallier, 2016) require broadening and shifting mission?

I examine how nonprofit organization staff navigate organizational mission as they encounter complex systems problems outside their area of expertise, focusing on environmental organizations encountering homelessness in river watersheds (Flanigan & Welsh, 2020). Homelessness is an urgent humanitarian crisis facing the US state of California (USICH, 2021) and is also recognized as a complex systems problem (Stroh, 2015, Flanigan & Welsh, 2020). Homelessness also poses serious environmental challenges. In California, many nonprofit organizations devote substantial effort mitigating the environmental impact of homelessness encampments (IEW, 2019; SDRPF, 2019, 2021), because in addition to sleeping in shelters or on the streets, many people experiencing homelessness stay along rivers, creeks, and canyons in California’s cities (Flanigan & Welsh, 2020, Verbyla et al., 2021). Using interview data with staff of nonprofit organizations working in water resources, land management, biodiversity preservation and environmental education, complemented with survey data and participant observation, I explore how environmental nonprofit organizations encountering homelessness navigate the tension between original mission focus and systems thinking, how organizations’ engagement with systems thinking correlates with their mission-related activities and thinking, and how these findings may be relevant for other nonprofit organizations facing complex systems problems.

Theoretical Overview

Considering Complex Systems Problems: Theories, Concepts, and Applications

Systems thinker Donella Meadows (2008) describes a system as “an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something” (p.11); she asserts that a system must, by definition, have a function or purpose. Renger (2022) gives the example of a clock as a complex system made up of many moving interdependent parts. At what point a system becomes complex is, as Miller & Page (2007) note, “an open question and one that can engender endless debate,” (p.5). Stroh (2015) reminds us that a system’s purpose may not be the one we would like it to accomplish—especially when thinking of social systems—which makes it all the more frustrating that systems are often stable and hard to change. With this in mind, Stroh (2015) defines systems thinking—which he considers both a set of principles and a collection of analytic tools—as the capacity to understand interconnections within systems in a way that allows one to accomplish a desired purpose. A benefit of systems thinking is that as individuals better comprehend the purpose a system achieves, they can then seek to change it.

A key feature of complex systems studies is that a system is not merely the sum of its parts (Miller & Page, 2007). Linear thinking biases decision makers toward believing polices that achieve short-term success can also achieve longer term success; that improving parts of a system will improve the whole; and that many concurrent independent initiatives, pursued with enough enthusiasm, will garner results (Stroh, 2015). As an example, in the arena of homelessness in many US cities we see funding for emergency shelters, police outreach teams, and Narcan distribution (a remedy to counteract drug overdose), but much less long-term investment in affordable housing or eviction prevention. In contrast, complex systems thinking understands that many quick fixes have unintended consequences; that improving the system requires improving relationships among the parts; and that focusing on a few critical sustained interventions is likely to produce larger systems change (Stroh, 2015). In the research context relevant to this study, research shows that both policing of people experiencing homelessness and public health clean-ups after disease outbreaks among people experiencing homelessness push people into riverbeds away from services (Flanigan & Welsh, 2020), increasing environmental consequences (Verbyla et al., 2021) and human vulnerability (Flanigan & Welsh, 2020, Verbyla et al., 2021).

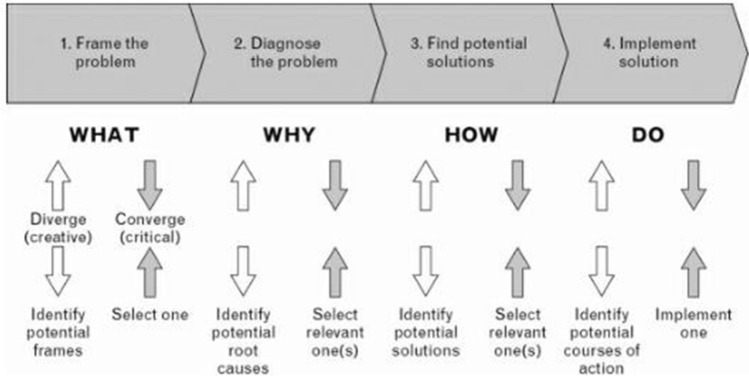

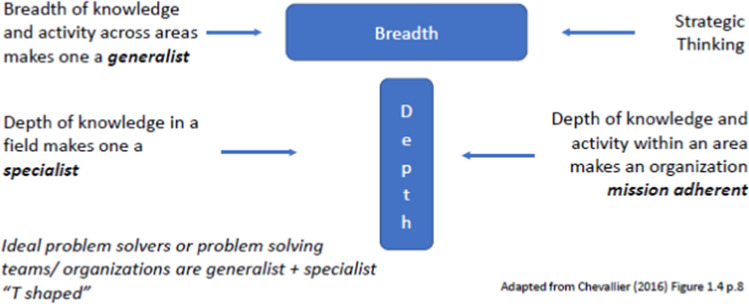

Stroh (2015) explains that while conventional, linear thinking may work for simple problems, it is not well suited to address complex, enduring social and environmental problems like homelessness, which we sometimes call wicked problems (Kettl, 2006; Rittel & Webber, 1973; Zellner & Campbell, 2015). Rittel & Webber (1973) call nearly all social policy problems wicked problems not because they are malevolent, but because they are difficult to describe conclusively or solve optimally, and it proves nearly impossible to agree upon underlying assumptions of equity and public good. Conceptually wicked problems overlap well with what Chevallier (2016) calls complex, ill-defined, nonimmediate (CIDNI) problems. CIDNI problems involve varied, dynamic, interdependent, and/or unclear obstacles; no fixed conditions or pathways to resolution; and one has days, weeks or longer to find and implement a solution. “CIDNI problems include ensuring environmental sustainability, reducing extreme poverty and hunger, achieving universal primary education, and all the other United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals,” Chevallier (2016) states (p.6). Complex systems thinking requires approaches that embrace both the breadth of generalist knowledge required for strategic thinking, and the depth of knowledge required of a specialist (Chevallier, 2016). This sort of problem solving requires both divergent thinking that identifies a multitude of options, and convergent thinking that focuses on a clear course of action (Chevallier, 2016, see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chevallier’s Figure “Effective complex problem solving requires alternating divergent and convergent thinking”

Nonprofit Organizations and Mission Drift

Mission holds a sacred space in the nonprofit sector, with scholars differentiating between the mission-driven nature of nonprofit organizations vis-à-vis businesses or the state (Frumkin, 2002; Salamon, 2003), and Sanders (2015) calling the tension between mission and market “a key feature of what it means to be nonprofit-like,” (p.218). Nonprofit organizations are accountable for abiding by their mission of enhancing specific values while also attending to market-like conditions as they offer services (Lim et al., 2021). Nonprofit organizations are cautioned against mission drift and mission creep (Beaton, 2021; Grimes et al., 2019; Jones, 2007; Ma et al., 2017), but simultaneously understand they must adapt to their environments. Terms like mission drift, mission creep, and mission displacement are used to describe an unwelcome or unintended movement from an organization’s original, core purpose (Berlan, 2018; Grimes et al., 2019). However, mission drift is difficult to define or even perceive because missions are socially constructed and individually understood (Berlan, 2018), making the desirability of mission change personal and subjective (Beaton, 2021), and internally conceptions of the mission and an organization’s activities are often conflicting or misaligned (Berlan, 2018; Lim et al., 2021).

As nonprofits more frequently encounter complex systems problems, they will face questions about whether shifts in practice are effective organizational adaptation or undesirable mission drift. When embedded in dynamic external environments, Lim et al. (2021) theorize that effective nonprofit leaders can engage in meaning making deriving from ongoing interactions between the leader's social construction of the organization and their social embeddedness in the environment. Lim et al.’s (2021) work suggests that effective leaders may be able to construct mission meaning for their organization out of the dynamic environments in which they are embedded.

Organizational Adaptation and Change

One reason organizational adaptation and change are challenging is because organizations are made up of individuals moving through a current of problems they must solve, considering solutions largely predetermined by whatever expertise they already possess. Members of organizations operate with a sense of their own and others’ expertise, thus solving group problems in predictable ways (Jeong & Brower, 2008). While predictability and known knowledge sets make organizations efficient, this makes adaptation difficult as organizations may prefer investing in existing routines rather than creating new ones. Except for the youngest organizations, change can be disruptive and difficult (Ginsberg & Buchholtz, 1990). Organizations sufficiently invested in learning can overcome inertia and successfully adapt, though the process may be costly and painful (Chen, 2013). Organizations in increasingly complex environments like those posed by complex systems problems benefit from an enhanced capacity to learn; cultures of learning and reflection; and structures that promote collective problem solving and cognitive reframing (Bess et al., 2010. Some organizations are less equipped to engage in learning, however (Bess et al., 2010), and may be less prepared to encounter complex systems problems.

Leadership is critically important in change processes, particularly investment in collaboration, dialogue, and diversity (Santora et al., 1999). Exercising leadership in meaning-making is key. Lim et al. (2021) argue meaning-making can be learned as an executive competency and proves useful when mission or services are in flux. Employee empowerment and ownership in change also is also crucial in successful organization adaptation (Lamm & Gordon, 2010). Relationships with the local community are an important tool of adaptation (Kimberlin, Schwartz & 2011), including bridging structures with the public (Bess et al., 2010). However, Jeong and Brower (2008) caution that the successful work of managers cannot be captured by “simplistic management tools” (p. 247) and instead is characterized by sensemaking that is improvisational and individually specific. Adaptation to complex and fluid problems cannot be prescribed with management formulas, but requires training that emphasizes team learning, real-life scenarios, and dilemmas characterized by uncertainty and ambiguity (Jeong & Brower, 2008).

As the environmental organizations in this study encounter homelessness, they engage in decision making about if and how to develop interventions related to the wicked complex systems problem of homelessness in watersheds. These organizations decide whether to adapt their activities to address this issue, facing substantial uncertainty and ambiguity in a field where they have little expertise. Some organizations learn, partner, adapt their mission, and/or consider if adaptation is a problematic deviation from their organization’s original mission.

Methodology

This article draws on data from targeted surveys of river-focused environmental organizations in the US state of California and qualitative interviews conducted on Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic. These data were complemented with over one hundred hours of participant observation conducted with a river-oriented environmental organization in southern California from 2019 through 2022.

Research Context

Homelessness is an urgent humanitarian crisis and hot political topic in the US state of California (e.g., Resnikoff, 2021). Homelessness also impacts the environmental; some environmental organizations in California find over ninety percent of their cleanup work involves removing debris from homelessness encampments from riverbeds and canyons (e.g., SDRPF, 2019). People experiencing homelessness live near urban waterways for several reasons, some of which are driven by existing service systems (Flanigan & Welsh, 2020). As a result, the staff of riparian protection nonprofits—often biologists, conservationists, and ecologists—find themselves on the front lines of one the most complex social and economic challenges in the state though they are trained in an entirely different arena.

Survey Methodology

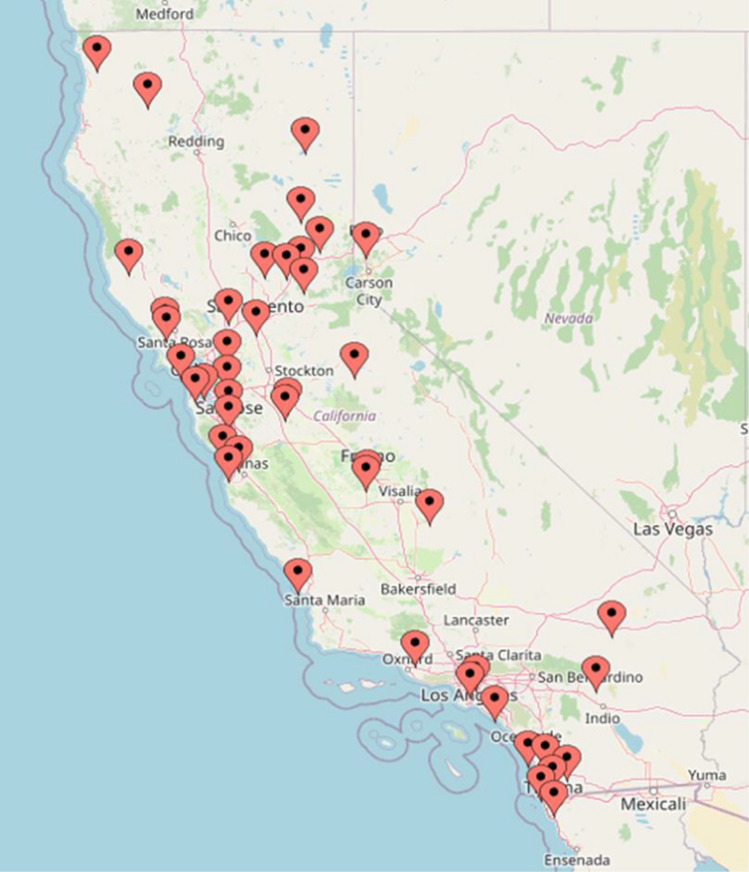

River-focused environmental organizations in California were selected for the sample from the database Guidestar, using a purposive sampling strategy based on likelihood that an organization conducted field activities in physical locations where staff will encounter individuals experiencing homelessness. The author assessed this based on prior experience with the river-dwelling homeless community and 100-plus hours of participant observation with a riparian nonprofit organization. Organizations met Guidestar sort feature characteristics in Table 1. Websites then were reviewed to confirm each organization appeared to conduct fieldwork in locations where people experiencing homelessness may reside. Using Qualtrics, web-based surveys were distributed to 80 organizations and were completed by 73 individuals from 43 organizations engaged in activities to protect rivers (see Table 2) across California (see Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Categories of organizations considered for survey in Guidestar database

| Environment > | Water resources > | Oceans and coastal waters |

| Rivers and lakes | ||

| Water conservation | ||

| Wetlands | ||

| Land resources > | All except tundra | |

| Biodiversity | ||

| Environmental education |

Table 2.

Response to the question: what type of work does the organization do? Please select all that apply

| Percent of total respondents (n = 73) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Advocacy | 52.05% | 38 |

| Education | 76.71% | 56 |

| Legal defense | 9.59% | 7 |

| Nature beautification (e.g., trash and litter cleanup) | 64.38% | 47 |

| Nature Restoration/ Preservation | 82.19% | 60 |

| Research | 36.99% | 27 |

| Service provision | 10.96% | 8 |

| Wildlife care and/or preservation | 20.55% | 15 |

| Other | 17.81% | 13 |

Fig. 2.

Geographic distribution of service areas of survey respondents in US State of California *Because multiple organizations may serve the same watershed, and watersheds may cover multiple cities or counties, the number of location points is not equal to the organizations represented in the survey responses. Staff from one organization in Baja California Norte (Mexico) and one organization in Nevada, whose river watersheds cross into California, also responded as the survey was forwarded among colleagues

Characteristics of Environmental Organizations Represented by Survey Respondents

Staff report frequently encountering homelessness (see Table 3) in a variety of ways (see Table 4). Nearly sixty percent encounter issues of homelessness regularly, and nearly thirty-five percent occasionally encounter issues of homelessness. Selection bias may have played a role since the survey topic was clear and staff rarely encountering homelessness may have chosen not to participate. However, survey respondents appear largely representative of the population of organizations working in this field based on characteristics easily assessed in Guidestar.

Table 3.

Response to the Question: Does your organization (and/or your staff and volunteers) ever encounter issues of homelessness?

| Percent of respondents (n = 67) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, we regularly encounter issues related to homelessness | 59.70% | 40 |

| On occasion we encounter issues related to homelessness, but not very often | 34.33% | 23 |

| No, we do not encounter issues related to homelessness in our work | 5.97% | 4 |

| Unsure | 0.00% | 0 |

Table 4.

Response to the Question: In what ways have your organization or staff/volunteers encountered issues of homelessness? Please select all that apply

| Percent of respondents (n = 64) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| We come across encampments and/or individuals experiencing homelessness while providing services (such as during clean ups, education, nature preservation or restoration) | 87.50% | 56 |

| We clean trash and litter from encampments | 60.94% | 39 |

| We provide service referrals to people experiencing homelessness (for example, tell people where they can go for assistance) | 20.31% | 13 |

| We provide services or other support (e.g., food, water, clothing) to people experiencing homelessness | 6.25% | 4 |

| We engage in education or advocacy on issues of homelessness | 20.31% | 13 |

| Other: | 23.44% | 15 |

| Not applicable; my organization does not encounter issues of homelessness | 1.56% | 1 |

Staff commonly report encountering encampments or unhoused individuals during cleanup events, nature presentations, or restoration activities (over 87% of respondents, see Table 4). Over sixty percent reported cleaning trash and litter from encampments. Over twenty percent provide service referrals, and over twenty percent engage in education and advocacy on issues related to homelessness. Over six percent provide direct services or other support to people experiencing homelessness. In qualitative comments, three individuals mentioned actively partnering with social service agencies to provide services.

As Table 5 shows, most staff (fifty-five percent) indicated homelessness had influenced the work of their organization for five or more years, and over fifty-seven percent are unsurprised by the relevance of homelessness to their work (see Table 6). Still, twenty-three percent describe homelessness as a newer influence on their organization (five years or less, see Table 5), and over thirty-seven percent were surprised that homelessness is relevant to their work (see Table 6). Those staff familiar with homelessness in watersheds commented that the problem has increased substantially in recent years.

Table 5.

Response to the question: Is homelessness a newer influence on the work of your organization and staff/ volunteers, or is it an issue you have encountered for quite some time?

| Percent of respondents (n = 60) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| My organization has been involved with issues of homelessness since its founding | 16.67% | 10 |

| My organization has been involved with issues of homelessness for 5 or more years | 38.33% | 23 |

| My organization has been involved with issues of homelessness for 2–5 years | 10.00% | 6 |

| Homelessness is a relatively new influence on the work of my organization (e.g., less than 2 years) | 13.33% | 8 |

| Unsure | 20.00% | 12 |

| Not applicable- issues of homelessness are not relevant to my organization's work | 1.67% | 1 |

Table 6.

Response to the question: Prior to your service with this organization, were issues of homelessness something you knew would be relevant to your work?

| Percent of respondents (n = 61) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| No | 37.70% | 23 |

| Yes, my interactions with homelessness are as I expected | 31.15% | 19 |

| Yes, but it is MORE than I expected | 24.59% | 15 |

| Yes, but it is LESS than I expected | 1.64% | 1 |

| Not applicable- issues of homelessness are not relevant to my organization's work | 4.92% | 3 |

Most staff (almost seventy-five percent) acknowledged they did not have past education or training to prepare them to work with issues of homelessness (see Table 7.) In contrast, staff were highly trained in the areas of expertise required for the core environmental aspects of their work. Table 8 lists the areas of educational specialization of survey respondents. The portrait painted by the survey results is of a workforce that is aware of the influence of homelessness on the work environment, but comparatively untrained to deal with a social problem that is considered challenging even by the best prepared public health and social work professionals.

Table 7.

Response to the question: Do you as an individual have past education or training that prepared you for working with issues of homelessness?

| Percent of respondents (n = 55) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 20.00% | 11 |

| No | 74.55% | 41 |

| Unsure | 5.45% | 3 |

Table 8.

Areas of Educational Specialization of Survey Respondents

| Biology | |

|---|---|

| Fire Management | Forestry and Earth Sciences |

| Business | Geography |

| Conservation and Resource Studies | Geomorphology |

| Ecology | Green Building and Renewable Energy |

| Education | Land Rehabilitation Science |

| Engineering | Marketing Communications |

| Environmental and Systematic Biology | Natural Resource Management |

| Environmental Chemistry | Physics |

| Environmental Engineering | Regional Development |

| Environmental Geography | Stream and Wetland Restoration |

| Environmental Law | Water Quality Monitoring |

| Environmental Management | Wildlife Biology |

| Environmental Policy | Wildlife Management |

| Environmental Science | |

| Environmental Studies |

*Similar specializations were condensed, and duplicates were removed

Over half of respondents worked at a management level or above (see Table 9). A quarter indicated the organization had made no changes in response to the influence of homelessness on the organization’s work (see Table 10). Many respondents reported at least some changes, most commonly new rules and protocols (reported by just over thirty-seven percent of respondents). This was followed by new or different partnerships with organizations (reported by over thirty-four percent of respondents), such as homelessness outreach organizations. Respondents also mention new training (usually related to COVID) and new types of communications with constituents and donors (each reported by nearly nineteen percent of respondents, see Table 10).

Table 9.

Response to the question: What best describes your role in the organization? Select all that apply

| Percent of respondents (n = 73) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Executive Director | 13.70% | 10 |

| Board member | 9.59% | 7 |

| Program Director/ Other management-level staff | 31.51% | 23 |

| Program staff | 34.25% | 25 |

| Fundraising/ Development | 2.74% | 2 |

| Financial Officer/Budgeting | 2.74% | 2 |

| Marketing/ Communications | 5.48% | 4 |

| Human Resources/ Training | 1.37% | 1 |

| Advocacy | 8.22% | 6 |

| Administrative | 1.37% | 1 |

| Intern | 0.00% | 0 |

| Other: | 9.59% | 7 |

Table 10.

Response to the question: To your knowledge, what changes has your organization made in response to the influence of homelessness on your work?

| Percent of respondents (n = 64) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| We have not made any changes related to the influence of homelessness | 25.00% | 16 |

| New programming or services | 17.19% | 11 |

| New or additional hiring or volunteer recruitment priorities | 10.94% | 7 |

| New training | 18.75% | 12 |

| New types of communication with constituents and donors | 18.75% | 12 |

| New types of fundraising | 9.38% | 6 |

| New or different partnerships with other organizations | 34.38% | 22 |

| Other: | 14.06% | 9 |

| Unsure | 9.38% | 6 |

| Not applicable- issues of homelessness are not relevant to my organization's work | 0.00% | 0 |

| New rules/ protocols | 37.50% | 24 |

Interestingly, staff offered mixed responses on whether their donors and constituents were aware of the impacts of homelessness on the work of their organization and their staff. Almost a third indicated all or many of their donors were aware of the impact of homelessness on their work (see Table 11). Yet almost forty-two percent indicated few if any donors or constituents were aware of the impacts of homelessness on the organization’s work. A full twenty percent were unsure (see Table 11). When asked if homelessness has impacted their organization’s mission, most individuals replied no (nearly forty-four percent). However, almost half (forty-nine percent) replied yes or maybe, and seven percent were unsure (see Table 12).

Table 11.

Response to the question: Thinking about members or donors to your organization, how much awareness do you think those individuals have about the impacts of homelessness on your organization and staff?

| Percent of respondents (n = 55) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| MOST/ALL members and donors are aware | 5.45% | 3 |

| MANY members and donors are aware | 27.27% | 15 |

| A FEW members and donors are aware | 21.82% | 12 |

| Most members and donors are NOT aware | 20.00% | 11 |

| Unsure | 25.45% | 14 |

| Not applicable- issues of homelessness are not relevant to my organization's work | 0.00% | 0 |

Table 12.

Response to the Question: Has the issue of homelessness impacted your organization’s mission?

| Percent of respondents (n = 55) | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 34.55% | 19 |

| Maybe | 14.55% | 8 |

| No | 43.64% | 24 |

| Unsure | 7.27% | 4 |

Interview Methodology

The survey concluded with a question asking if the person completing the survey would be willing to participate in an interview. Seventeen staff volunteered to be interviewed as part of the research. Semi-structured interviews were conducted ranging from 25 to 75 min in length and averaging 46 min in length. The interview protocol, approved as exempt by the university’s Institutional Review Board, posed questions about if and how organizations interact with issues of homelessness; ways organizations may have adapted to the issue of homelessness; if and how homelessness may have impacted individual staff; and if and how homelessness has influenced organizational mission, relationships, and long-term goals. The research team interviewed all individuals who expressed a willingness to be interviewed and theoretical saturation was achieved (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), indicating additional data no longer generates new ideas (Charmaz, 2006).

Data Analysis

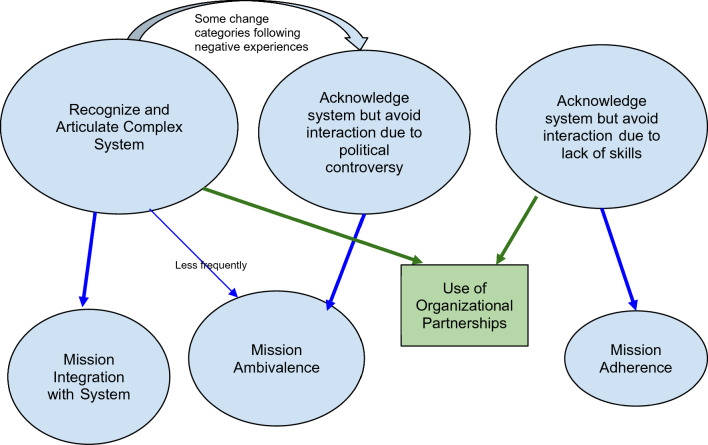

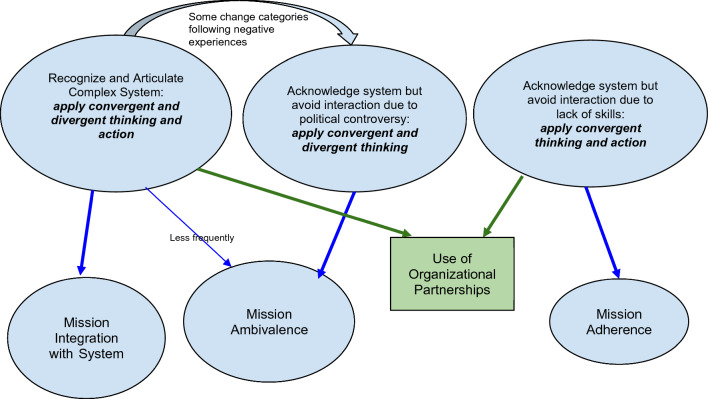

The data were coded manually using thematic analysis, which involves analyzing, identifying, and presenting patterned meaning or themes within a dataset (Boyatzis, 1998; Braun & Clarke, 2006). The analysis primarily took an applied thematic approach (Guest et al., 2012a), which is an inductive approach that analyzes themes in an applied manner within common sources of qualitative data—in this case interview transcripts, qualitative survey comments, and field notes—to represent experiences of research participants (Guest et al., 2012b). The process involved reading, re-reading, and then, memoing regarding patterns in the data (Birks et al., 2008); based on these emerging patterns as well as key themes in the nonprofit literature, the team established a set of inductive and deductive codes. The research team defined and revised these codes iteratively through group discussion and applied codes to sections of transcribed text (Guest et al., 2012b), using Excel to organize and later categorize important patterns across the data (Ose, 2016). As an example, the interview protocol did ask questions regarding mission and partnerships, and these were coded deductively; however, themes such as political controversy with donors, complex problems, and systems thinking emerged inductively. Relationships among themes were determined by iterative attempts to construct a thematic diagram that arranged participants’ descriptions of their organization’s mission-related behavior based on the extent to which they articulated a systems perspective on homelessness in watersheds (see Fig. 3), and multiple rounds of analytic writing and editing (Attride-Stirling, 2001).

Fig. 3.

Relationships between organization staff members’ systems perspectives and mission perspectives

Analysis of Interview Data: Complex Systems Problems and Systems Thinking

Interviews provide deeper understanding of how staff of environmental organizations engage with the complex systems problem of homelessness and its impact on the natural environment. Qualitative data offer a more nuanced understanding of how staff articulate and engage with complex systems, and how that impacts their relationship to their organizational mission and activities.

Recognizing and Articulating Complex Systems

Several interviewees recognized and articulated that as environmentalists encountering homelessness in natural environments, they were encountering complex systems problems. As one participant observed,

“(Homelessness in riverbeds has) just made it apparent how you just can't separate all the ills of our society; they just like mush together. You just can't separate any thread out. My boss always says, “The task that impedes your task is your task.” And that's how we've started to think about this issue. Not that people experiencing homelessness are just impediments to our task, but like clearly, we can't look away…On a macro scale, yes, it has changed how I think about the interconnectedness of our problems, basically. I am interested in figuring out how to do work that is at the root. I sort of thought land conservation was at the root, was really getting to the root of the problem, but it's like, “No, it might go even further down.””

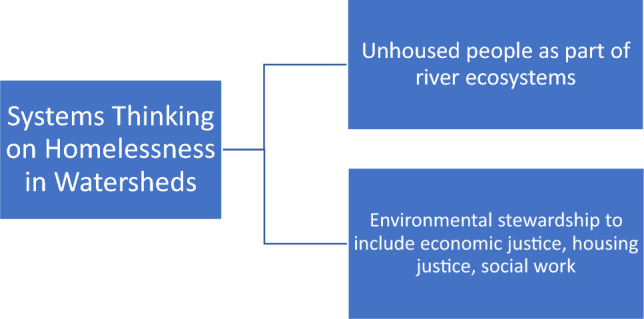

Participants articulating a systems perspective of homelessness in watersheds did so in two broad ways (see Fig. 4). Some positioned people experiencing homelessness as part of the ecosystem. One interviewee described a railroad map from the early twentieth century labeling the watershed where he works, currently occupied by many homeless encampments, as “Hobo Jungle.” “It's been used by homeless folks as a place to live for over one hundred years,” he explained. A fisheries biologist described plans to educate homeless riverbed residents about which fish absorbed fewer toxins and therefore, were safer to eat, because he and his colleagues often saw people fishing when conducting water sampling. Other participants spoke of teaching riverbed residents about edible plants to forage, or ways to avoid harming certain habitats near their encampments. An ecologist contextualized homeless residents in terms of his field of ecological science.

“We think nature is the nonexistence of humans being there, you know. Just nature, there's no humans there. But in reality, humans are a huge component of the system, and we have people living in the river canyon. It's the human component, it's part of it. So you have to figure out, what do we do with that? …So definitely the human component is always, like, humans are part of our ecosystem.”

Fig. 4.

Systems thinking on homelessness in watersheds as conceptualized by some interviewees

Other participants incorporated the economy, environment, housing, and social policy as a system that must be addressed to reduce the underlying need for individuals to live in riverbeds. As one interviewee described,

“We have a partnership council, and that's made up of a bunch of science people, the water quality, engineering people and you know people like landscape architects and also a lot of environmental organizations…But the master plan does include the goal of helping to increase affordable housing options, and we need the mental health organizations, hospitals and the shelters…”

As a participant summarized,

“The more we ignore the effects of homelessness, the more we're very partial in our work that we're experiencing. You know there's needles and trash and human feces in the river, and that's bad for all of the things that we're focused on.”

Acknowledging Systems but Avoiding Interaction due to Perceived Skills Limitations

Another subset of participants acknowledged they encountered complex systems problems in their work, but believed their organization did not have the skillset to engage effectively with the issue, and thus, decided not to engage. One staff explains,

“We decided we're not a social services organization, we don't know the right way. We're still learning. We need another organization whose mission is specifically dealing with this problem.”

Another organization with limited engagement with the homeless community hesitated to publicize their work for fear of public relations complications or greater stigmatization for the homeless community. A participant explains,

“For homeless awareness, we do not get engaged with that issue. I have seen that there's not even a concern. As for publicizing our work around homelessness, we just leave it alone. We take care of the problem that we know to take care of, which is to effectively remove pollution from the environment. I don't think it would be effective for us to in any way get involved publicly. We wouldn't want to get involved in a public discussion that creates more stigma.”

Many comments are easily read as having a clear focus on one’s mission. Interviewees focus on their skillset and the distinct mission and goals of their organization, which are not tied to the complex systems problem that is impacting their organization’s work environment.

Acknowledging Systems and Supplementing Skill Limitations with Partnerships or Staffing

Other staff developed partnerships to help supplement skills for interacting with the homeless community. Some partnerships were simple and not aimed at long-term solutions; for example, seeking law enforcement assistance in advance of clean-ups. Some staff described handing out food, water, supplies, or lists of resources offered by local partners.

“In the list of services that we provide to people that we encounter living on our properties, some of them are kind of faith-based options, so Catholic Charities gives out meals, they have showers, things like that.”

Other staff described more substantial partnerships aimed at longer-term and sustainable solutions. These included developing partnerships with social workers and social services agencies, local homeless shelters, and fire and rescue in case of health emergencies.

“Continuing to also work with our social workers has been helpful. That at least seems to feel better than going in and saying, “Hey you need to move your camp within three days or I'm going to move your stuff.””

In some cases, organizations actively partnered with social workers who conduct fieldwork multiple times a week. One organization worked with a social worker who had housed multiple individuals.

“Finding a partnership was really difficult because you know (the riverbed) is not super easily accessible, it can feel a little bit, almost dangerous I guess for people who are not familiar with the terrain…Once we had a willing partner organization it was a full six months before we started having outreach workers out in the river with us consistently…Then it was more time before we got (outreach worker), who on this grant we had gotten became our official riverbed outreach worker.”

Acknowledging Systems but Avoiding Interaction due to Political Controversy

Homelessness is very controversial in California (e.g., Resnikoff, 2021), and some interviewees were aware they encountered complex systems issues but avoided interacting with homelessness due to this controversy. They feared interaction might have negative implications for public relations, constituent or volunteer relations, and donor relations. Not all agreed; some organizations were public in their messaging about outreach to people experiencing homelessness and had cohorts of volunteers interested in helping the homeless community. Still, for some organizations, explicitly engaging with the issue of homelessness was perceived as risky. One participant described the general public’s lack of interest and compassion for the issue of homelessness.

“We should think about what the root causes of homelessness are and support things that will address those, and also treat people who don't have housing as people and not just call the cops on them. And I don't think that's a conversation people (speaking of her organization’s constituents) really wanted to have.”

Another participant described similar perspectives from his organization’s volunteers.

“The way that people feel about encampments and homeless people along the creek who are volunteers with the organization, is like they just want them out.”

Yet another participant explained how past programming to collect waste from homeless encampments had resulted in backlash and loss of funding.

“When you're dealing with homelessness there's a really sharp contrast between whether people want you to fund that, I mean it's a really delicate issue… (and when our trash collection program from homeless encampments became public), that shut down a lot, a lot of funding sources.”

For these staff, the political controversy associated with homelessness meant their organizations must exercise caution or avoid engagement altogether.

The Influence of Complex Systems on Mission Adherence, Mission Ambivalence, and Mission Integration

There were clear patterns in the ways that staff described their engagement with complex systems and then, described the relationship between homelessness and their organizational mission (see Fig. 3). Staff’s engagement with the complex systems problem of homelessness in watersheds correlates with staff’s relationship to their organizational mission and their engagement in interorganizational partnerships.

Integrating Homeless Communities into Mission

Data indicate that when staff clearly articulated a systems perspective on homelessness in watersheds as described in the previous section, they more often reported integrating issues of homelessness into their mission and activities. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the clear and compelling ways in which these staff described an intersection of human and ecological needs. Staff made statements like, “We're really striving hard to be pro human and pro river, a balance. Being river advocates and honoring the dignity of people suffering,” and “Working in homeless camps is pretty congruent with river cleanups.”

Other staff described concrete methods of integrating homelessness into the operations of their organizations. One participant described efforts to integrate expertise regarding homelessness into the organization’s board.

“We've recruited board members, specifically with backgrounds in homeless services and other awareness. We've talked about bringing someone on our board who has experienced homelessness.”

Another participant discussed how ending homelessness has become central to the organization’s mission, and how metrics for success now include encampment reduction alongside water quality and invasive species removal.

“We believe that trying to end homelessness is central to having a clean and healthy river. Like it just is, both from a water quality standpoint, for recreation, for safety, all of those things have always been kind of central to our mission. I think it's more that it's new that we see ourselves as setting metrics for reducing encampments, whereas before we saw ourselves as setting metrics for reducing trash. So I think that has changed a little bit, because we see ourselves now as being able to influence those encampments.”

Mission Ambivalence

The situation for organizations that recognize and articulate complex systems (see Fig. 3) is not entirely rosy. Staff sometimes describe experiencing mission ambivalence due to resource constraints that make it challenging to focus on their core mission while also addressing homelessness. One staff describes the challenges of meeting the organization’s core mission of habitat preservation while also engaging in homelessness management.

“Oftentimes my colleagues and I get into these conversations about mission drift as a conservation organization. Is it really our responsibility or our goal to be providing services or accommodation for these folks? Are we carrying out our mission of preserving wildlife habitat by spending a ton of time working with the homeless community? And in many circumstances, we can't carry out our mission on these river properties without addressing the homeless problem. But at the same time that's not really our goal as an organization, so many times it's more of a reaction than strategic planning.”

Other staff worry that homelessness may be pulling them away from their key goals.

“Protecting the water resources has always been our mission and bringing homelessness into that, you know, we've had to. But we don't want them to, you know, keep us away from the objective, which is really to create a connection to the water resource and to protect it and to get people out on it.”

During interviews, one could sense participants’ internal debate regarding whether homelessness was indeed part of the organization’s mission. This participant describes homelessness management goals while simultaneously maintaining homelessness has not influenced the organization’s mission. Such experiences might account for the “maybe” and “unsure” responses in Table 12.

“With our approach to homelessness management, are we hitting our goals? Are we carrying out successful habitat restoration projects in the midst of homelessness? Are we doing enough? So I don't think homelessness has influenced our mission, but it's regularly coming up in our management approach, though.”

Another group of staff expressed mission ambivalence: those who had previously engaged with issues of homelessness and suffered negative political consequences, and those who had a clear sense that the issue was too politically sensitive among their constituents or donor base and chose not to engage with the issue. Some staff described creating trash collection programs for riverbed residents that they intentionally did not publicize for fear of negative backlash from their own constituents. They believed this work helped the river ecosystem, but would be perceived as “enabling” the homeless community to remain in the riverbed. Despite recognizing and articulating a complex systems perspective, these staff expressed ambivalence about their mission and activities for political reasons.

Mission Adherence

A final group of staff avoided interacting with issues of homelessness due to perceived limitation to their skills and usually couched this lack of interaction in the classic nonprofit management language of mission adherence and avoiding mission drift. These staff clearly and repeatedly spoke of a clear focus on their own skillset. For example, one staff mentions not addressing homelessness due to their organization’s focus on environmental science.

“Since I was here, I mean it's been an issue (speaking about homelessness), it's been something that's there, but it's never been something that we're like “Oh!”, because, again, we're focused in, we focus a lot more on environmental science.”

A second staff mentions their organization’s mission stability is due to their organization’s focus on water resources.

“I think it (our mission) has remained stable over time because really at the heart of it it's just about protecting the water resource.”

Table 2 showing us the types of work organizations do and Table 8 showing staff’s educational specializations remind us that nearly all interviewees could make similar points about focus and expertise. The interesting finding from the data analysis is a clear pattern among staff based on whether staff articulated complex systems perspectives on the issue of homelessness in riverbeds in nuanced ways (see Fig. 3). Those who presented nuanced and articulate systems perspectives—those who had perhaps examined and put more thought into the system—were more likely to describe that their organization had integrated the complex systems issue of homelessness into its mission and activities, or were more likely to report their organization was undergoing an internal debate or ambivalence around their mission. Those who did not engage deeply with the systems issue could fail to do so while remaining confident they were engaging in appropriate nonprofit practice: adhering to their mission and avoiding mission drift or mission creep.

Discussion: Impacts of Systems Thinking on Nonprofit Mission

Following an inductive analysis of interview data, descriptions of complex system thinking by staff of environmental organizations encountering homelessness nearly perfectly correlated with their viewpoints on their organizations’ missions. These correlations can be predicted by the literature on complex systems thinking and complex problem solving. As Chevallier (2016) explains, complex problem-solving knowledge involves breadth of generalist knowledge and depth of specialist knowledge. Adapting his work in Fig. 5, I note that normally we ask nonprofit organizations for only one of these things: high specialization and mission adherence. Notably, the participants in this study also have highly specialized knowledge sets that are quite distinct from the complex systems problem with which they are interacting (see Table 8). It is perhaps logical that those participants who reported the least involvement in complex systems thinking were the most mission adherent, as the problem-solving knowledge in which they are best versed, depth, is precisely suited for that.

Fig. 5.

Applying Chevallier’s effective complex problem-solving knowledge framework to organizational mission

As discussed earlier, clear mission focus has value. However, referring to his figure (p.8) that I adapted in Fig. 5, Chevallier (2016) notes, a “drawback of focusing solely on the vertical bar of the T is that it limits innovation as we fall prey to the “not invented here” syndrome,” (p. 6). When encountering complex systems problems, in this study some staff demonstrate a willingness to develop a breadth of knowledge and activities that correspond to the horizontal bar of the T in Fig. 5. However, are our most mission adherent organizations—those demonstrating only a depth of knowledge and activities along the vertical bar of the T—falling into a “not addressed here” or “not our mission” syndrome? This narrow focus usually is rewarded in nonprofit management, but is it the way we should go about solving complex systems problems?

Chevallier (2016) and I dare say other systems thinkers like Meadows (2008) and Stroh (2015) would say no. Chevallier reminds us that solving complex problems effectively involves integrating both divergent and convergent thinking (see Fig. 1), convergent thinking often being the realm of the “specialist.” In Fig. 6, I apply the knowledge Chevallier presents in Fig. 1 to my own findings, with an adaptation of Fig. 3. Mission-driven organizations certainly can engage in both divergent and convergent thinking, but in my findings, individuals who espoused a mission focus also emphasized strategies and activities that most align with convergent thinking and action (see Fig. 6). Convergent thinking and action also happen to align conveniently with conventional nonprofit management thinking on mission focus and not succumbing to mission drift. Therefore, it is easy to couch these approaches as mission adherent and, indeed, they are. A second set of organizations rests in the middle, ambivalent about mission due to past negative experiences or anticipated negative experiences of political controversy, or being in a place of still negotiating mission while considering the complex problem. These actors apply convergent and divergent thinking, but do not engage in (or no longer engage in) divergent action (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Relationships between Organization Staff Members’ Complex Problem-Solving Perspectives and Mission Perspectives

At the other end of the spectrum is a set of organizations applying both convergent and divergent thinking and action. These are the types of strategies that the complex systems thinking literature suggests that may be most effective at addressing complex systems problems. These actions may appear to be mission drift to the outside observer, but likely are essential to addressing complex systems problems. These organizations have integrated systems problems into their mission or are in the process of doing so (see Fig. 6). Those who have integrated the complex systems problem into their mission use partnerships in addition to applying both convergent and divergent thinking and action. It remains to be seen through future research, but literature suggests these types of organizations may be most successful at helping address societies’ complex systems problems.

Conclusion

A constant, persistent mission may be difficult for an organization to maintain amid an ever-changing society facing complex systems problems. In this study, some organizations were in a state of flux as they dealt with complex systems problems, replying with statements such as, “I think our mission is in the process of being impacted now.” In a dynamic context, the mission of an organization will shift in response to rapid change, making organizations susceptible to mission drift. The question we need to pose to ourselves, however, is if this shift is in fact negative. As nonprofit organizations more frequently encounter complex systems problems in their work, are their changing practices to meet these challenges examples of mission drift, or innovative organizational adaptation? Can the world’s most complex systems problems—society’s wicked problems—be solved without what we have traditionally termed mission drift? The complex systems problems literature suggests that the answer to that question is no. When we do not engage with systems issues and instead confidently adhere to our missions, should we praise ourselves for proper nonprofit management, or are we letting ourselves off the hook?

The qualitative data in this study show clear patterns among staff: perspectives on organizational mission varied according to the extent to which staff articulated a systems perspective on complex problems. Those staff who clearly and sophisticatedly articulated complex systems perspectives on the issue of homelessness in riverbeds in nuanced ways were more likely to describe that their organization had integrated the complex systems issue into their mission and activities, or were more likely to report their organization was undergoing an internal debate or ambivalence around their mission. These organizations applied convergent and divergent thinking. Those who acknowledged a systems issue in a brief and basic manner described their mission in the classic nonprofit management language of mission adherence and demonstrated only convergent thinking (see Fig. 6). An important direction for future research is to examine whether the relationship found here between systems perspectives and mission-related behavior is evident when considering other types of organizations interacting with other types of complex systems problems. Given the prevalence of complex systems problems in our world and the nimbleness and capacity of nonprofit actors to address these problems, pursuing this question this is a worthwhile line of research and I call upon colleagues to join in this work.

It is reasonable to assume that those staff who presented more nuanced and articulated systems perspectives had perhaps reflected upon more greatly, put more thought into, or perhaps engaged in more organizational learning regarding the system (Bess et al., 2010). This is not a question I pursued in this study, but it is an interesting and important topic for future research. It will be important to find ways to enable organizations to take innovative, problem-solving steps and partner in nontraditional ways to address complex problems without fear. In this sample, some organizations that had a systems perspective were nonetheless hesitant to address homelessness in creative ways due to fear of blowback from their constituents. If nontraditional partner organizations—in this case, riparian organizations—see the bigger picture but are hesitant to incorporate social issues with political undertones into their mission out of fear of losing financial support from powerful donors, we move no closer to addressing our most complex problems. Funding for organizations appears to be a major factor in their fear of adapting to complex problems and could instead be used as a lever to encourage adaptation and innovative partnerships. Further research on innovative funding and partnership arrangements in complex systems problems is needed and has the potential for great impact.

Finally, nonprofit organizations certainly can be mission driven, strategic thinking, and flexible. The individuals in my sample whose organizations had integrated homelessness issues into their missions were no less mission driven than their mission-adherent colleagues—their missions only had evolved. They certainly considered their organizations no less successful. As Lim et al. (2021) note, effective nonprofit leaders engage in meaning making based on their social embeddedness in the environment, and I trust they can construct mission meaning for their organization from a complex systems problem in the environment. I believe organizations can achieve an appropriate depth and breadth of knowledge and skill (Fig. 5) through recruitment, with the optimal balance varying based on organization and issue area. Mission-driven organizations and complex problem-solving organizations are not mutually exclusive, and organizations with a strong mission can work strategically to balance divergent and convergent strategies.

Acknowledgements

Utmost thanks to the residents of the San Diego River riverbed who have kindly welcomed the research team into their homes as we have conducted fieldwork for this project, sometimes generously offering food, water, and other resources from their own modest supplies. Many thanks to the San Diego River Park Foundation and the intrepid Morgan Henderson, Shane Conta, and Rachel Downing for being our guides, and to Sarah Hutmacher for her thoughtful perspectives. My gratitude and respect go to our interview and survey participants for their time and for their commitment to our rivers, canyons, and other natural spaces. The author would like to thank my current and former students Tobias Burack, Paola Díaz de Regules MA/MPA, Jazmin Luna, Sarah Verdusco Singh MPA, and Jessica Williamson for their assistance on this research project. Thanks to members of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Associations and the International Society for Third Sector Research for feedback on prior versions of portions of this work, and also to very helpful reviewers from Voluntas. This research was supported in part by a San Diego State University Division of Research and Innovation RSCA Assigned Time Award.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

I do not have any potential conflicts of interest of which I am aware related to this research or its publication.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed by San Diego State University’s Institutional Review Board and was approved as exempt because the interview protocol asked questions about the organization.

Human and animal rights

Rather than about human subjects themselves. Nonetheless, the author and the research team, all of whom have CITI Human Subject certification.

Informed consent

Informed interview participants of the university’s determination but still obtained informed consent before performing interviews.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research. 2001;1(3):385–405. doi: 10.1177/146879410100100307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton E. Institutional leadership: Maintaining mission integrity in the era of managerialism. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2021 doi: 10.1002/nml.21460,32(1),55-77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R, Savani S. Surviving mission drift: How charities can turn dependence on government contract funding to their own advantage. Nonprofit Management & Leadership. 2011;22(2):217–231. doi: 10.1002/nml.20050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berlan D. Understanding nonprofit missions as dynamic and interpretative conceptions. Nonprofit Management & Leadership. 2018;28(3):413–422. doi: 10.1002/nml.21295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bess K, Perkins D, McCown D. Testing a measure of organizational learning capacity and readiness for transformational change in human services. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2010;39(1):35–49. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2011.530164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks M, Chapman Y, Francis K. Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2008;13(1):68–75. doi: 10.1177/1744987107081254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis R. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis SAGE Publications.

- Chen C. Revisiting organizational age, inertia, and adaptability: Developing and testing a multi-stage model in the nonprofit sector. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 2013;27(2):251–272. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-10-2012-0166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier A. Strategic Thinking in Complex Problem Solving. Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan S, Welsh M. Unmet needs of individuals experiencing homelessness near San Diego waterways: The roles of displacement and overburdened service systems. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration. 2020;43(2):105–130. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin P. On being nonprofit: A conceptual and policy primer. Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg A, Buchholtz A. Converting to for-profit status: Corporate responsiveness to radical change. Academy of Management Journal. 1990;33(3):445–477. doi: 10.2307/256576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes M, Williams T, Zhao E. Anchors aweigh: The sources, variety, and challenges of mission drift. Academy of Management Review. 2019 doi: 10.5465/amr.2017.0254,44(4),819-845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012a). Chapter 2: Planning and preparing the analysis. In Applied Thematic Analysis (pp. 21–48). SAGE.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012b). Chapter 3: themes and codes. In Applied Thematic Analysis (pp. 49–78). SAGE.

- Inland Empire Waterkeepers (2019). Solving Homelessness in the Watershed Conference.

- Jeong HS, Brower RS. Extending the present understanding of organizational sensemaking: Three stages and three contexts. Administration & Society. 2008;40(3):223–252. doi: 10.1177/0095399707313446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. The multiple sources of mission drift. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2007;36(2):299–307. doi: 10.1177/0899764007300385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kettl DF. Is the worst yet to come? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2006;604(1):273–287. doi: 10.1177/0002716205285981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberlin S, Schwartz S, Austin M. Growth and resilience of pioneering nonprofit human service organizations: A cross-case analysis of organizational histories. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 2011;8(1–2):4–28. doi: 10.1080/15433710903272820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk G, Nolan S. Nonprofit mission statement focus and financial performance. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2010 doi: 10.1002/nml.20006,20(4),473-490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm E, Gordon J. Empowerment, predisposition to resist change, and support for organizational change. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 2010;17(4):426–437. doi: 10.1177/1548051809355595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Brower RS, Berlan DG. Interpretive leadership skill in meaning-making by nonprofit leaders. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2021;32(2):307–328. doi: 10.1002/nml.21477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Jing Y, Han J. Predicting mission alignment and preventing mission drift: How revenue sources matter? SSRN Electronic Journal. 2017 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2915677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows D. Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Page S. Complex adaptive systems: An introduction to computational models of social life. Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Min N, Shen R, Berlan D, Lee K. How organizational identity affects hospital performance: Comparing predictive power of mission statements and sector affiliation. Public Performance & Management Review. 2019 doi: 10.1080/15309576.2019.1684958,1-26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ose SO. Using excel and word to structure qualitative data. Journal of Applied Social Science. 2016;10(2):147–162. doi: 10.1177/1936724416664948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renger, R. (2022). System Evaluation Theory: A Blueprint for Practitioners Evaluating Complex Interventions Operating and Functioning as Systems. Information Age Publishing.

- Resnikoff, N. (2021). It’s Hard to Have Faith in a State that Can’t Even House its People. New York Times, July 26, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/26/opinion/homelessness-california.html. Accessed October 18, 2021.

- Rittel HWJ, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences. 1973;4:155–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salamon LM. The resilient sector: The state of nonprofit America. Brookings Institution Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- San Diego River Park Foundation (SDRPF) (2019). “Geodata for a Healthy San Diego River”. Public presentation February 2019.

- San Diego River Park Foundation (SDRPF) (2021). “Behind the Scenes of Working Toward a Trash-Free River with Data Collection.” Public Communication.

- Sanders M. Being nonprofit-like in a market economy: Understanding the mission-market tension in nonprofit organizing. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2015;44(2):205–222. doi: 10.1177/0899764013508606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santora J, Seaton W, Sarros J. Changing times: Entrepreneurial leadership in a community-based nonprofit organization. The Journal of Leadership Studies. 1999;6(3/4):101–109. doi: 10.1177/107179199900600308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs R. A networked infrastructure of cultural equity? Social Identities in the Missions of Local Arts Agencies, The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 2020 doi: 10.1080/10632921.2020.1845890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan M. Transacting business and transforming communities: The mission statements of community foundations around the globe. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2021;50(2):262–282. doi: 10.1177/0899764020948617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroh D. Systems thinking for social change. Chelsea Green Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (2021). California Homelessness Statistics. https://www.usich.gov/homelessness-statistics/ca/ (Accessed October 18, 2021)

- Verbyla M, Calderon J, Flanigan S, Garcia M, Gersberg M, Kinoshita A, Mladenov N, Pinongcos F, Welsh M. An assessment of ambient water quality and challenges with access to water and sanitation services for individuals experiencing homelessness in riverine encampments. Environmental Engineering Science. 2021;38(5):389–401. doi: 10.1089/ees.2020.0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D, Jung T, Aranson R. Mission-market tensions and nonprofit pricing. The American Review of Public Administration. 2009;40(2):153–169. doi: 10.1177/0275074009335411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zellner M, Campbell S. Planning for deep-rooted problems: What can we learn from aligning complex systems and wicked problems? Planning Theory & Practice. 2015;16(4):457–478. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2015.1084360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]