Abstract

Background:

Screening using low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) is a more effective approach and has the potential to detect lung cancer more accurately. We aimed to conduct a meta-analysis to estimate the accuracy of population-based screening studies primarily assessing baseline LDCT screening for lung cancer.

Methods:

MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica Database, and Web of Science were searched for articles published up to April 10, 2022. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the data of true positives, false-positives, false negatives, and true negatives in the screening test were extracted. Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 was used to evaluate the quality of the literature. A bivariate random effects model was used to estimate pooled sensitivity and specificity. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated by using hierarchical summary receiver-operating characteristics analysis. Heterogeneity between studies was measured using the Higgins I2 statistic, and publication bias was evaluated using a Deeks’ funnel plot and linear regression test.

Results:

A total of 49 studies with 157,762 individuals were identified for the final qualitative synthesis; most of them were from Europe and America (38 studies), ten were from Asia, and one was from Oceania. The recruitment period was 1992 to 2018, and most of the subjects were 40 to 75 years old. The analysis showed that the AUC of lung cancer screening by LDCT was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96–0.99), and the overall sensitivity and specificity were 0.97 (95% CI: 0.94–0.98) and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82–0.91), respectively. The funnel plot and test results showed that there was no significant publication bias among the included studies.

Conclusions:

Baseline LDCT has high sensitivity and specificity as a screening technique for lung cancer. However, long-term follow-up of the whole study population (including those with a negative baseline screening result) should be performed to enhance the accuracy of LDCT screening.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Low-dose computed tomography, Screening, Sensitivity, Specificity, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Lung cancer resulted in the largest number of deaths and the second largest number of new cases around the world in 2020.[1] According to the Globocan 2020 released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the number of new cases and deaths due to lung cancer worldwide in 2020 were approximately 2.21 million and 1.80 million, respectively, accounting for 11.4% and 18.0% of all cancer cases and deaths, respectively.[1] Survival is highly dependent on early diagnosis; therefore, an effective screening program for the early detection of lung cancer could have a significant role in reducing this high mortality rate.[2]

Previous clinical trials have found that screening methods, such as chest radiology and sputum cytology, do not provide a mortality advantage over standard practice.[3] In the early 1990s, low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) was introduced as a potential screening tool. High-quality images could be produced at much lower dose levels than with standard computed tomography (CT). The use of LDCT for lung cancer screening has now been shown to be an effective screening modality that can reduce mortality from lung cancer.[4,5] Therefore, LDCT can now be considered an acceptable form of early lung cancer screening.[6] Subsequently, more lung cancer screening studies with LDCT have been performed. However, to our knowledge, no meta-analysis has evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of LDCT testing for lung cancer.

Therefore, the present meta-analysis aimed to estimate the accuracy of population-based screening studies primarily assessing baseline LDCT screening for lung cancer. Our study will objectively and accurately evaluate the screening effect of LDCT for lung cancer and provide a reasonable reference basis for the selection of lung cancer screening technology in the future.

Methods

Literature search strategies

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-Diagnostic Test Accuracy Statement.[7] Themes of “lung neoplasms” “mass screening” “early detection of cancer” and “tomography, X-ray computed” were used as Medical Subject Headings subject terms and “lung neoplasm” “pulmonary neoplasm” “bronchopulmonary neoplasm” “bronchial neoplasm” “lung cancer” “pulmonary cancer” “bronchopulmonary cancer” “broncho-pulmonary cancer” “bronchial cancer” “lung carcinoma” “pulmonary carcinoma” “bronchopulmonary carcinoma” “bronchial carcinoma” “bronchogenic carcinoma” “lung blastoma” “pulmonary blastoma” “bronchopulmonary blastoma” “broncho-pulmonary blastoma” “bronchial blastoma” “lung tumor” “pulmonary tumor” “bronchopulmonary tumor” “broncho-pulmonary tumor” “bronchial tumor” “screen” “test” “testing” “detection” “computed tomography” “LDCT” “CT” “low-dose computed tomography” “sensitivity” “specificity” “negative rate” “positive rate” “predictive value” “diagnostic accuracy”, and “diagnostic performance” as free words in English language were used in combination to search. The retrieved databases included MEDLINE (via PubMed), Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), and Web of Science. The date of the literature was specified up to April 10, 2022. In addition, references to relevant systematic reviews and studies were manually searched as a supplement to the electronic search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The literature included in this study met the following criteria: (1) prospective or retrospective studies evaluating patients in the context of screening; (2) LDCT as a screening method; (3) clear diagnostic criteria for lung cancer (biopsy, surgery, or follow-up results); and (4) number of cases for which true positives, false-positives, false negatives, and true negatives could be extracted or calculated.

The literature excluded in this study was mainly due to the following reasons: cellular or animal studies; studies on accuracy of computer-aided diagnostic techniques; reviews and case reports; sample sizes <200; necessary data could not be extracted or calculated directly from the original article; or studies with smaller sample sizes when subjects overlapped.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two authors (FNY and YW) according to a predefined data collection form, and in case of inconsistency, a third senior researcher (LWG) made the judgment. The extracted data consisted of four parts: (1) literature characteristics, including first author and year of publication; (2) screening protocol information, including study site, study design, period of recruitment, project name, sample size, age and sex of study subjects, positive definition, and gold standard; (3) study result information, including the number of true-positive, false-positive, false-negative, and true-negative cases. In the case of incomplete data in the 2-by-2 contingency table, data were obtained by contacting the authors or were extrapolated from indicators, such as sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value as reported in the literature.

Quality assessment

In this study, two authors (YX and JD) independently reviewed each study for the bias assessment and applicability using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. QUADAS-2 includes four domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing, with a total of 18 signaling questions.[8] The risk of bias was assigned as high, low, or unclear for each domain. Studies with at least one domain at high risk of bias or with all four domains at unclear risk were assigned an overall assessment of “at risk” of bias.

Statistical analysis

A 2-by-2 contingency table was constructed. Pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), and area under the curve (AUC) of hierarchical summary receiver-operating characteristics (HSROC) were calculated. The pooled summary of sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, and AUC was estimated based on the bivariate random effects meta-analysis. The summary DOR was computed using the Mantel–Haenszel method. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Higgins I2 statistic, with I2 >50% indicating the presence of heterogeneity.[9] When there was substantial heterogeneity in diagnostic accuracy across studies, we investigated a threshold effect by (1) visual assessment of coupled forest plots of sensitivity and specificity, and (2) a Spearman correlation coefficient between the sensitivity and false-positive rate (correlation coefficient >0.60 indicated a threshold effect).[10] We also visually assessed the differences between the 95% confidence region and the 95% prediction region in the HSROC curve to examine the presence of heterogeneity between studies.[11] Subgroup analyses for sensitivity, specificity, AUC, PLR, NLR, and DOR were subsequently carried out according to the geographical areas of the study origin, study design, year of publication, number of patients, population, multicenter or not, and positive definition. Deeks’ funnel plot was generated to test for publication bias, with statistical significance being assessed based on Deeks’ asymmetry test.

The statistical analyses were performed using STATA SE version 15.1 for Windows (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Systematic review and study characteristics

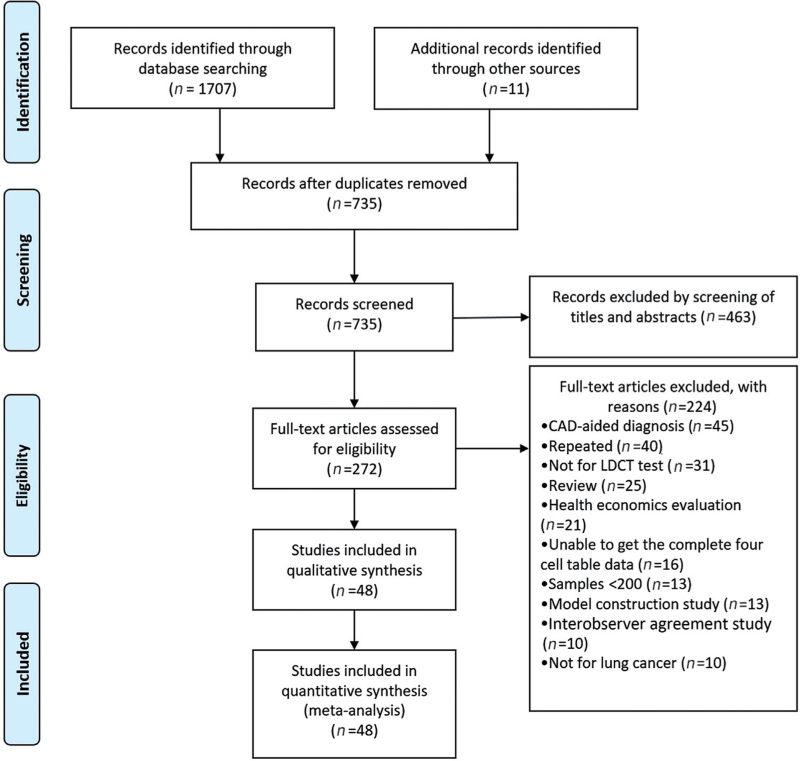

A total of 1707 relevant papers were searched in MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), and Web of Science by the search formula, and 11 papers were added by manual search. Only 735 papers remained after duplicates were removed. With reference to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the literature was initially screened, and 463 papers were eliminated by reading the titles and abstracts. Then, the remaining papers were read in full, 224 papers were excluded, and 48 papers[4,12–58] were finally included. The literature screening process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the systematic literature search for studies of baseline low-dose CT lung cancer screening. CAD: Computer-aided diagnostic techniques; CT: Computed tomography; LDCT: Low-dose computed tomography.

Two separate studies were reported in one paper,[20] so a total of 49 studies were included in this meta-analysis. Of these, 22 studies were conducted in Europe, 15 in North America, ten in Asia, one in South America, and one in Oceania. The years of publication of the included studies were 2001 to 2021 and the years of recruitment/screened were 1992 to 2018, with the earliest screening program from the USA[12] and the most recent screening program from China.[56] The scan parameters ranged from 100 to 140 kVp for tube voltage and 15 to 250 mAs for tube current. Of these, 14 studies (28.6%) used 140 kVp and 15 to 75 mAs, 7 (14.3%) used 120 kVp and <40 mAs, 7 (14.3%) used 120 kVp and ≥40 mAs, 6 (12.2%) achieved an effective radiation dose <2 mSv, 5 (10.2%) used 100 to 140 kVp and 20 to 100 mAs according to subject body weight and the other 10 (20.4%) did not provide scan parameters. A total of 157,762 cases were included in the study, with a sample size ranging from 224 to 26,722 cases in each study, of which 18.4% (9/49) had a study sample size ≥5000. Subjects were screened at the starting and ending ages of 40 years and 96 years, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

Studies included in the meta-analysis and their characteristics.

| Author | Year | Country | Project name | Total number of participants screened (baseline) | Male (%) | Age (years)∗ | Positive definition |

| Aberle et al[4] | 2011 | USA | NLST | 26,722 | 59 | 55–74 | Lung-RADS ≥3 |

| Henschke et al[12] | 2001 | USA | ELCAP | 1000 | 54 | ≥60 | NCN |

| Sone et al[13] | 2001 | Japan | Shinshu | 5483 | 44 | 64 (40–74) | Non-cancerous lung lesion, non-cancerous but suspicious lung lesion, suspicion of lung cancer, indeterminate small lung nodule (<3 mm), and extrathoracic abnormality |

| Diederich et al[14] | 2002 | Germany | Münster | 817 | 72 | 53 (40–78) | NCN ≥10 mm |

| Nawa et al[15] | 2002 | Japan | Hitachi | 7956 | 79 | 55–59 | NCN ≥8 mm |

| Sobue et al[16] | 2002 | Japan | ACLA | 1611 | 88 | 40–79 | Nodule ≥5 mm |

| Swensen et al[17] | 2002 | USA | Mayo | 1520 | 52 | 59 (50–85) | NCN |

| Pastorino et al[18] | 2003 | Italy | Milan | 1035 | 71 | 58 (50–84) | NCN ≥5 mm |

| Gohagan et al[19] | 2004 | USA | LSS | 1586 | 58 | 55–74 | NCN ≥3 mm, focal parenchymal opacification and endobronchial lesions |

| Henschke et al[20] | 2004 | USA | ELCAPs I and II | 2968 | NA | ≥40 | Solid or part-solid NCN ≥5 mm or non-solid NCN ≥8 mm |

| Henschke et al[20] | 2004 | USA | ELCAPs I and II | 4538 | NA | ≥40 | Solid or part-solid NCN ≥5 mm or non-solid NCN ≥8 mm |

| MacRedmond et al[21] | 2004 | Ireland | PALCAD | 449 | 50 | 56† | NCN ≥10 mm |

| Bastarrika et al[22] | 2005 | Spain | Pamplona | 911 | 74 | 55 (≥40) | One to six NCN, or more than six nodules with the largest one ≥5 mm |

| Chong et al[23] | 2005 | Korea | Seoul | 6406 | 86 | 46–85 | NCN |

| Novello et al[24] | 2005 | Italy | Turin | 519 | 74 | 59 (54–79) | NCN ≥5 mm |

| Blanchon et al[25] | 2007 | France | Depiscan | 336 | 71 | 56 (47–75) | NCN ≥5 mm |

| Infante et al[26] | 2008 | Italy | DANTE | 1276 | 100 | 65 (60–74) | NCN ≥6 mm |

| Toyoda et al[27] | 2008 | Japan | Osaka | 4689 | 59 | ≥40 | Diagnosed with the need for further clinical examination |

| Veronesi et al[28] | 2008 | Italy | COSMOS | 5201 | 66 | 57 (50–84) | NCN ≥5 mm |

| Wilson et al[29] | 2008 | USA | PLuSS | 3642 | 51 | 59 (50–79) | NCN ≥4 mm |

| Lopes Pegna et al[30] | 2009 | Italy | ITALUNG | 1406 | 64 | 55–69 | NCN ≥5 mm or a non-solid nodule ≥10 mm or the presence of a part-solid nodule |

| Pedersen et al[31] | 2009 | Denmark | DLCST | 2052 | 55 | 49–74 | NCN ≥5 mm |

| van Klaveren et al[32] | 2009 | Netherlands and Belgium | NELSON | 7557 | 84 | 59 ± 6 | NCN ≥10 mm |

| Croswell et al[33] | 2010 | USA | PLCOS | 1610 | 58 | 55–74 | NCN >3 mm |

| Menezes et al[34] | 2010 | Canada | Toronto study | 3352 | 46 | 60 (50–83) | NCN ≥5 mm or non-solid nodule ≥8 mm |

| Becker et al[35] | 2012 | Germany | LUSI | 2029 | 50 | 50–69 | NCN ≥5 mm |

| Pastorino et al[36] | 2012 | Italy | MILD | 2303 | 69 | 58 (≥49) | NCN ≥60 mm3 |

| Rzyman et al[37] | 2013 | Poland | Pilot Pomeranian Lung Cancer Screening Program | 8649 | NA | 50–75 | NCN ≥10 mm or NCN <10 mm with typical radiological findings |

| Sozzi et al[38] | 2014 | Italy | MILD | 643 | NA | ≥50 | NCN ≥5 mm |

| Crucitti et al[39] | 2015 | Italy | Unrespiro per la vita | 1500 | 62 | 62† (≥55) | NCN ≥4 mm |

| Milch et al[40] | 2015 | USA | New York | 320 | 54 | 64 (55–74) | Lung-RADS ≥3 |

| Sanchez-Salcedo et al[41] | 2015 | Spain | P-IELCAP | 3061 | 73 | 55 (49–62) | Emphysema |

| dos Santos et al[42] | 2016 | Brazil | BRELT1 | 790 | 50 | 61.9 ± 4.6 | NCN >4 mm |

| Field et al[43] | 2016 | UK | UKLS | 1994 | 75 | 67 (50–75) | NCN ≥3 mm |

| Ritchie et al[44] | 2016 | Canada | PanCan | 828 | NA | 50–75 | Lung-RADS ≥3/NCN ≥4 mm |

| Jacobs et al[45] | 2017 | USA | Gundersen Health System | 680 | 55 | 64 (55–77) | Lung-RADS ≥3 |

| Marshall et al[46] | 2017 | Australia | QLCSS | 256 | 67 | 65 (60–74) | Lung-RADS ≥3/NCN ≥4 mm |

| Hsu et al[47] | 2018 | China | Taiwan | 1978 | 55 | 57 (40–80) | Lung-RADS ≥3/NCN ≥4 mm |

| Meier–Schroers et al[48] | 2018 | Germany | Bonn | 224 | NA | 59 (50–70) | Lung-RADS ≥3 |

| Bhandari et al[49] | 2019 | USA | Kentucky | 4500 | 46 | 62 | Lung-RADS ≥3 |

| Crosbie et al[50] | 2019 | UK | LHC | 1384 | NA | 65† | Solid nodule ≥8 mm with a risk of malignancy ≥10% or any other finding concerning for malignancy requiring immediate assessment |

| Fan et al[51] | 2019 | China | Shanghai | 14,506 | 60 | 53 (35–96) | NCN |

| Kaminetzky et al[52] | 2019 | USA | ACR accredited lung cancer screening program | 1181 | 48 | 64 ± 16 | Lung-RADS ≥3 |

| Spiro et al[53] | 2019 | UK | LungSEARCH | 239 | 52 | 63 | NCN ≥9 mm |

| Tremblay et al[54] | 2019 | Canada | Alberta | 775 | 50 | 63† | Lung-RADS ≥3 |

| Leleu et al[55] | 2020 | France | French prospective study | 949 | NA | 55–74 | NCN >10 mm |

| Wei et al[56] | 2020 | China | LungSPRC | 2006 | 60 | 40–74 | Solid or part-solid nodules ≥5 mm, or non-solid nodules ≥8 mm, or airway lesion, nodules and masses suspicious for lung cancer |

| Wu et al[57] | 2021 | China | BUILT study | 1502 | 44 | 57 (51–64) | NCN ≥2 mm |

| Wang et al[58] | 2021 | China | Shandong | 10,823 | 54 | ≥40 | Lung-RADS ≥4 |

Data are presented as median (range), range, median, mean ± standard deviation.

Mean. ACLA: Anti Lung Cancer Association; BRELT1: First Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial; BUILT: Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation; COSMOS: Continuous Observation of Smoking Subjects; DANTE: Detection And screening of early lung cancer with Novel imaging TEchnology and molecular assays; DLCST: Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial; ELCAP: Early Lung Cancer Action Project; ITALUNG: Italian Lung Trial; LHC: Lung health check; LSS: Lung screening study; Lung-RADS: Lung CT screening reporting and data system; LungSPRC: Lung Cancer Screening Program in Rural China; LUSI: Lung Cancer Screening Intervention Trial; MILD: Multicentric Italian Lung Detection; NA: Not available; NCN: Non-calcified nodule; NLST: National Lung Screening Trial; PALCAD: ProActive Lung Cancer Detection; PanCan: Pan-Canadian Early Detection of Lung Cancer Study; P-IELCAP: Pamplona International Early Lung Cancer Detection Program; PLCOS: Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; PLuSS: Pittsburgh Lung Screening Study; QLCSS: Queensland Lung Cancer Screening Study; UKLS: UK Lung Cancer Screening.

Quality assessment

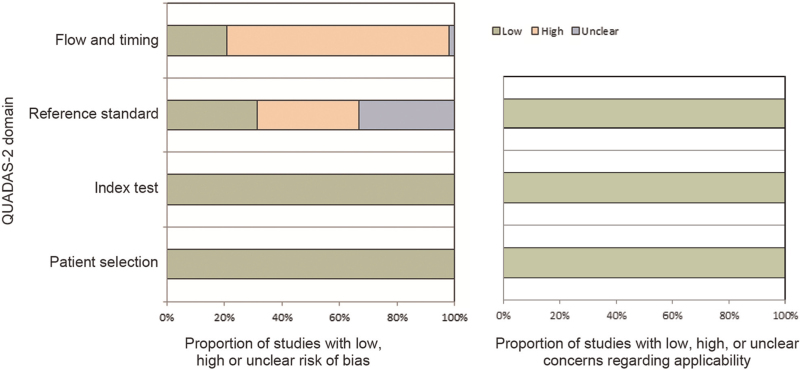

The results of quality assessments using the QUADAS-2 tool are summarized in Figure 2. With regard to patient selection and index tests, all studies had a low risk for bias. In the domain of bias in the reference standard, 17 studies were scored as “high risk” and 16 studies were scored as “unclear risk” because of no/unclear explanation of the blinding results of the index test. With regard to bias in the patient flow and timing, 37 studies were scored as “high risk” and one study was scored as “unclear risk”, mainly because not all patients received the reference standard. With regard to applicability, all included studies were scored “low” in the three domains.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph by the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies version. QUADAS-2: Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2.

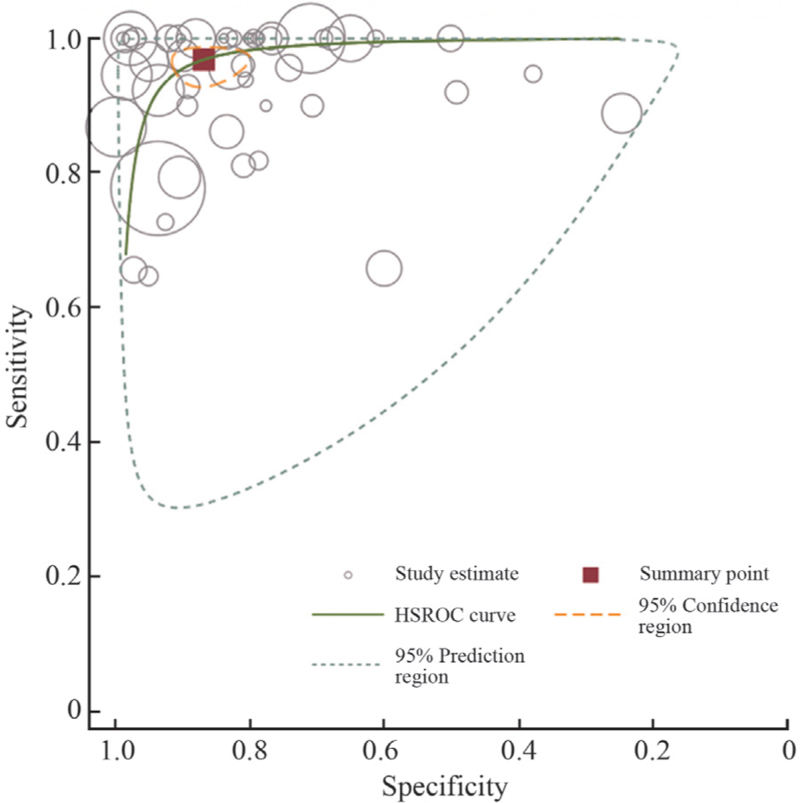

Threshold effect test

Figure 3 shows the HSROC curve illustrating the pooled AUC estimates derived from a bivariate random-effects model analysis. The distribution of sensitivity and specificity did not show a “shoulder shape,” and the HSROC curve was symmetrical about the opposite diagonal, suggesting that there was no diagnostic threshold effect among the included studies. The correlation between sensitivity and 1-specificity was tested, and the Spearman coefficient was −0.09 (P = 0.563 > 0.05), suggesting that sensitivity and specificity were independent, further confirming that there was no diagnostic threshold effect between the two variables.

Figure 3.

HSROC curves of LDCT for lung cancer diagnosis. HSROC: Hierarchical summary receiver-operating characteristics; LDCT: Low-dose computed tomography.

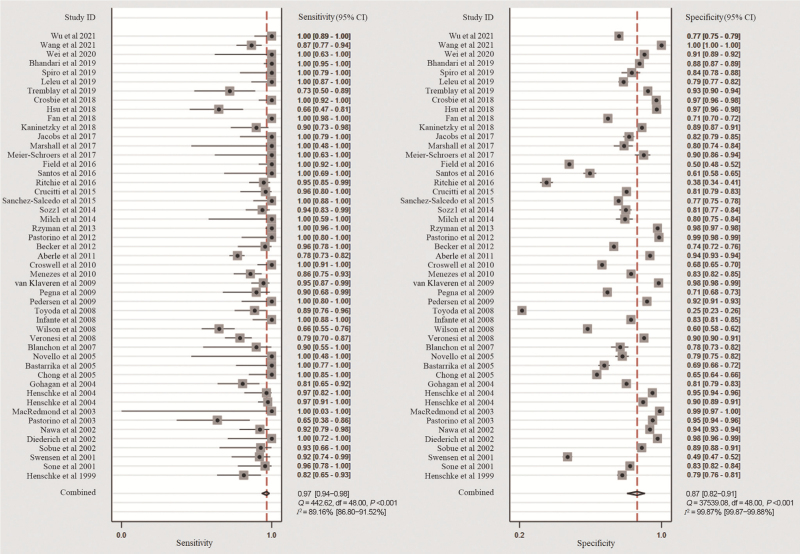

Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy

A bivariate random-effects model was used to quantify the diagnostic accuracy. The overall sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC were 0.97 (95% CI: 0.94–0.98), 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82–0.91), 7.30 (95% CI: 5.20–10.30), 0.04 (95% CI: 0.02–0.07), 197 (95% CI: 93–415), and 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96–0.99), respectively. The results of the Higgins I2 statistic [Figure 4] suggested that there was a large heterogeneity in both sensitivity (I2 = 89.16%) and specificity (I2 = 99.87%).

Figure 4.

Coupled forest plots of the pooled sensitivity and specificity.

Subgroup analysis

To further explore the causes of study heterogeneity, we divided the participants into subgroups according to the geographical areas of the study origin, study design, year of publication, number of patients, population, multicenter or not, and positive definition. As shown in Table 2, the results of the subgroup analysis showed a slight increase in pooled sensitivity (0.99) and specificity (0.90) in Europe but a slight decrease in North America (sensitivity = 0.93 and specificity = 0.82). Stratified analysis by positive definition showed that sensitivity was the highest with the detection of non-calcified nodules (NCNs) (0.99), which showed the lowest specificity (0.67). As the definition of positivity changes (NCN diameter increases), there is a tendency for sensitivity to decrease and specificity to increase. Subgroup analysis showed that the results did not change significantly with the study origin, study design, year, scanning parameters, sample size, population and number of participating centers. In short, the estimated heterogeneity for the included studies decreased to some degree but was not eliminated.

Table 2.

Results of subgroup analyses for diagnostic accuracy.

| Heterogeneity test | |||||||||

| Variables | Studies, n | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | PLR | NLR | DOR | P for Q test | I2 (%) |

| Overall | 49 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 7.3 | 0.04 | 197 | <0.001 | 100 |

| Region | |||||||||

| Asia | 10 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 8.5 | 0.04 | 217 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Europe | 22 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.99 | 9.5 | 0.02 | 595 | <0.001 | 98 |

| North America | 15 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.94 | 5.1 | 0.09 | 56 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Study design | |||||||||

| RCT | 13 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 5.3 | 0.05 | 119 | <0.001 | 94 |

| Prospective cohort | 32 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 8.3 | 0.04 | 191 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Year | |||||||||

| 1999–2005 | 14 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 7.8 | 0.07 | 110 | <0.001 | 93 |

| 2006–2010 | 10 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 4.7 | 0.10 | 49 | <0.001 | 98 |

| 2011–2015 | 8 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 9.4 | 0.02 | 436 | <0.001 | 98 |

| 2016–2021 | 17 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 7.9 | 0.01 | 1094 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Scan parameters | |||||||||

| 140 kVp, 15–75 mAs | 14 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 8.2 | 0.06 | 143 | <0.001 | 99 |

| 120 kVp, <40 mAs | 7 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 20.9 | 0.06 | 334 | 0.004 | 79 |

| 120 kVp, ≥40 mAs | 7 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 7.8 | 0.01 | 573 | <0.001 | 93 |

| 100–140 kVp, 20–100 mAs | 5 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 5.1 | 0.06 | 90 | 0.500 | 100 |

| Number of patients | |||||||||

| <5000 | 40 | 0.97 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 6.1 | 0.04 | 166 | <0.001 | 99 |

| ≥5000 | 9 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 17.0 | 0.04 | 477 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Population | |||||||||

| High-risk | 41 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 6.7 | 0.04 | 160 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Normal | 8 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 11.5 | 0.02 | 591 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Multicenter | |||||||||

| No | 25 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 8.5 | 0.06 | 137 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Yes | 24 | 0.98 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 6.2 | 0.02 | 301 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Positive definition | |||||||||

| Lung-RADS ≥3 | 9 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 6.8 | 0.06 | 122 | <0.001 | 98 |

| NCN | 4 | 0.99 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 3.0 | 0.02 | 149 | <0.001 | 89 |

| NCN ≥4 mm | 7 | 0.95 | 0.64 | 0.89 | 2.7 | 0.07 | 36 | <0.001 | 96 |

| NCN ≥5 mm | 9 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 6.5 | 0.09 | 70 | <0.001 | 95 |

| NCN ≥10 mm | 4 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 47.2 | 0.02 | 2536 | 0.097 | 39 |

AUC: Area under the curve; CT: Computed tomography; DOR: Diagnostic odds ratio; Lung-RADS: Lung CT screening reporting and data system; NCN: Non-calcified nodule; NLR: Negative likelihood ratio; PLR: Positive likelihood ratio; RCT: Randomized controlled trial.

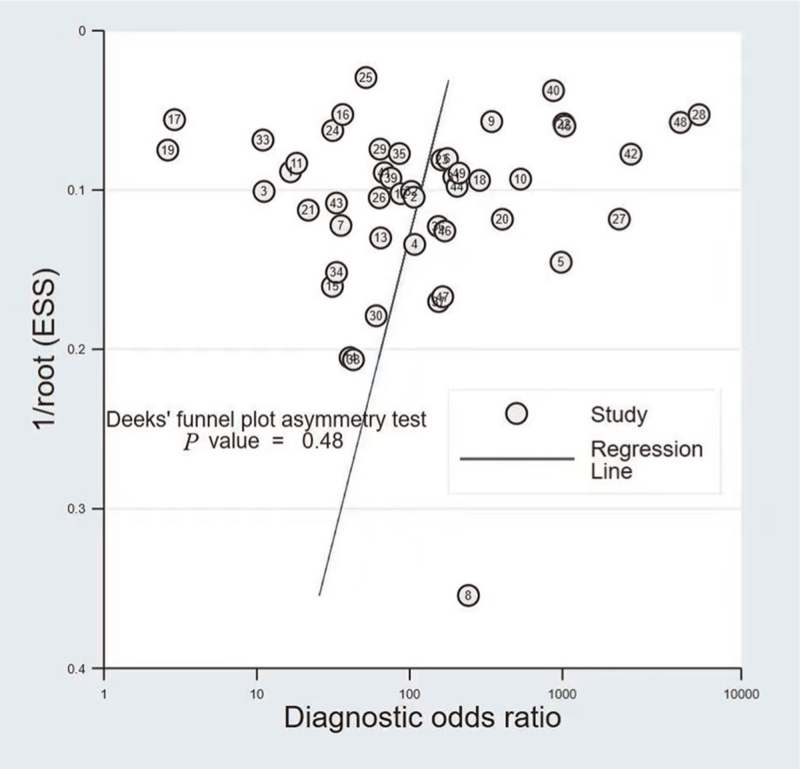

Publication bias

Weighted linear regression was used to test the symmetry of the funnel plot, with DOR as the dependent variable, 1/square root of the effective sample size (root [ESS]) as the independent variable and weight as the ESS [Figure 5]. The slope of the regression line was calculated to be −6.02 (P = 0.485 > 0.05) and the difference was not statistically significant, indicating that there was no publication bias among the included studies.

Figure 5.

Deeks’ funnel plot. ESS: Effective sample size.

Discussion

Before this study, there were several meta-analyses of lung cancer screening by LDCT.[2,59,60] Different from our study, these meta-analyses focus on the efficacy of LDCT screening, such as lung cancer incidence, lung cancer mortality, and all-cause mortality. Although some of these meta-analyses have addressed the question of accuracy in subanalyses, they only described it and did not pool the results. This systematic review investigated the diagnostic performance of LDCT for lung cancer screening. Pooled effect estimates from the included studies demonstrated high accuracy of LDCT screening and robust study results with an overall sensitivity of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.94–0.98), overall specificity of 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82–0.91), and AUC of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96–0.99).

The age and population of the screened subjects are important factors affecting the accuracy of LDCT screening. Among lung cancer screening guidelines, most recommend 50 years or 55 years of age as the starting age and 74 years as the upper age limit for lung cancer screening, although some guidelines recommend screening up to 77 years or 80 years of age.[61–65] For the studies included in this meta-analysis, the screening age range was 40 to 96 years old, and six of them chose the age range recommended by the guidelines. The benefit of lung cancer screening increases with the increasing risk of lung cancer in the screening population. According to the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) data, the number of lung cancer screening cases needed for each case of lung cancer death reduction in high-risk populations was significantly lower than that in low-risk populations. Among all the people who avoided dying of lung cancer due to screening, 88.0% were at high risk of lung cancer.[66] Therefore, across the lung cancer screening guidelines or consensuses published by countries around the world, lung cancer screening in high-risk populations is recommended.[61–64] Of the studies included in this meta-analysis, 83.7% (41/49) were conducted in high-risk populations.

Similar to our results, a systematic review showed that the sensitivity of LDCT for lung cancer screening ranged from 59.0% to 100.0%, and the specificity of LDCT ranged from 26.4% to 99.7%.[2] An important reason for the relatively large difference in sensitivity and specificity is the difference in the definition of positivity. Whether the screening is positive determines whether further diagnostic tests and invasive tests are needed. If the definition of positive screening is broad, it may lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment.[67] However, if the definition is conservative, lung cancer may be missed. The NLST defines nodules >4 mm as screening positive to obtain a false-positive rate of 96.4%.[4] In a randomized controlled trial on lung cancer screening in China, the nodule determination criteria using those of the NLST study were found to have good sensitivity and specificity (98.1% and 78.2%) but a false-positive rate of 93.7% (753/804).[68] Gierda et al[69] compared lung cancer misses and false-positives with different nodule classification criteria based on NLST data. The results showed that, although the nodule classification criteria of 5, 6, 7, and 8 mm missed 1.5%, 2.7%, 6.5%, and 9.9% of cases, respectively, the number of false-positives was reduced by 14.2%, 35.5%, 52.7%, and 64.8%, respectively. In our study, the sensitivity and specificity with the nodule classification criteria of 4, 5, and 10 mm were 0.95 and 0.64, 0.92 and 0.86, and 0.98 and 0.98, respectively. The false-positive rates were 95.7%, 89.4%, and 62.5%, respectively.

The present study has several strengths. First, in contrast to published systematic reviews of LDCT screening,[2,59,60] the present analysis is one of the first systematic reviews investigating the diagnostic performance of LDCT for lung cancer screening. Second, we applied rigorous inclusion/exclusion criteria and advanced meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Finally, subgroup analyses for sensitivity, specificity, AUC, PLR, NLR, and DOR stratified by the geographical areas of the study origin, study design, year of publication, number of patients, population, multicenter or not, and positive definition were conducted. Thus, the effect of potential confounders was minimized. In addition, no publication bias was observed in our analyses, indicating that our results are robust.

However, the meta-analysis has several limitations. First, false negative rates have not been generally well reported among the published studies, resulting in a possible overestimation of our findings (especially sensitivity). Second, substantial study heterogeneity was observed. To solve this issue, we examined the threshold effect between sensitivity and specificity using a coupled forest plot and Spearman correlation coefficient and performed subgroup analyses. Of course, we were not fully able to explain the heterogeneity. Including more prospective studies with a larger study population might help to validate the present conclusions with relatively less heterogeneity. Finally, in our study, the included studies were restricted to those published in English, which might introduce language bias as well.

In conclusion, the present study summarizes the accuracy data of LDCT for lung cancer screening worldwide, which provides basic data for policy-makers in developing prospective lung cancer screening programs on the one hand and helps the subjects weigh the advantages and disadvantages of screening more scientifically on the other hand. The evaluation of the accuracy of the scientific design of lung cancer screening technology is still very limited; therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of low-cost primary screening technology and protocols with a rigorous scientific design will be an important next step.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 212300410261). The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Guo L, Yu Y, Yang F, Gao W, Wang Y, Xiao Y, Du J, Tian J, Yang H. Accuracy of baseline low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin Med J 2023;136:1047–1056. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002353

Lanwei Guo and Yue Yu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021; 71:209–249.. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonas DE, Reuland DS, Reddy SM, Nagle M, Clark SD, Weber RP, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2021; 325:971–987.. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontana RS, Sanderson DR, Woolner LB, Taylor WF, Miller WE, Muhm JR. Lung cancer screening: the Mayo program. J Occup Med 1986; 28:746–750.. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198608000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:395–409.. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Heuvelmans MA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:503–513.. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naidich DP, Marshall CH, Gribbin C, Arams RS, McCauley DI. Low-dose CT of the lungs: preliminary observations. Radiology 1990; 175:729–731.. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM, Clifford T, et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA 2018; 319:388–396.. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155:529–536.. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327:557–560.. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devillé WL, Buntinx F, Bouter LM, Montori VM, de Vet HC, van der Windt DA, et al. Conducting systematic reviews of diagnostic studies: didactic guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol 2002; 2:9.doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J, Kim KW, Choi SH, Huh J, Park SH. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating diagnostic test accuracy: a practical review for clinical researchers-part II. Statistical methods of meta-analysis. Korean J Radiol 2015; 16:1188–1196.. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.6.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henschke CI, Naidich DP, Yankelevitz DF, McGuinness G, McCauley DI, Smith JP, et al. Early lung cancer action project: initial findings on repeat screenings. Cancer 2001; 92:153–159.. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010701)92:1<153::AID-CNCR1303>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sone S, Li F, Yang ZG, Honda T, Maruyama Y, Takashima S, et al. Results of three-year mass screening programme for lung cancer using mobile low-dose spiral computed tomography scanner. Br J Cancer 2001; 84:25–32.. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diederich S, Wormanns D, Semik M, Thomas M, Lenzen H, Roos N, et al. Screening for early lung cancer with low-dose spiral CT: prevalence in 817 asymptomatic smokers. Radiology 2002; 222:773–781.. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2223010490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nawa T, Nakagawa T, Kusano S, Kawasaki Y, Sugawara Y, Nakata H. Lung cancer screening using low-dose spiral CT: results of baseline and 1-year follow-up studies. Chest 2002; 122:15–20.. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobue T, Moriyama N, Kaneko M, Kusumoto M, Kobayashi T, Tsuchiya R, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose helical computed tomography: anti-lung cancer association project. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20:911–920.. doi: 10.1200/jco.2002.20.4.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Sloan JA, Midthun DE, Hartman TE, Sykes AM, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose spiral computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:508–513.. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.2107006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pastorino U, Bellomi M, Landoni C, De Fiori E, Arnaldi P, Picchio M, et al. Early lung-cancer detection with spiral CT and positron emission tomography in heavy smokers: 2-year results. Lancet 2003; 362:593–597.. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gohagan J, Marcus P, Fagerstrom R, Pinsky P, Kramer B, Prorok P. Baseline findings of a randomized feasibility trial of lung cancer screening with spiral CT scan vs chest radiograph: The Lung Screening Study of the National Cancer Institute. Chest 2004; 126:114–121.. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Smith JP, Libby D, Pasmantier M, McCauley D, et al. CT screening for lung cancer assessing a regimen's diagnostic performance. Clin Imaging 2004; 28:317–321.. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacRedmond R, Logan PM, Lee M, Kenny D, Foley C, Costello RW. Screening for lung cancer using low dose CT scanning. Thorax 2004; 59:237–241.. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.008821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastarrika G, García-Velloso MJ, Lozano MD, Montes U, Torre W, Spiteri N, et al. Early lung cancer detection using spiral computed tomography and positron emission tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171:1378–1383.. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1479OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong S, Lee KS, Chung MJ, Kim TS, Kim H, Kwon OJ, et al. Lung cancer screening with low-dose helical CT in Korea: experiences at the samsung medical center. J Korean Med Sci 2005; 20:402–408.. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.3.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novello S, Fava C, Borasio P, Dogliotti L, Cortese G, Crida B, et al. Three-year findings of an early lung cancer detection feasibility study with low-dose spiral computed tomography in heavy smokers. Ann Oncol 2005; 16:1662–1666.. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanchon T, Bréchot JM, Grenier PA, Ferretti GR, Lemarié E, Milleron B, et al. Baseline results of the Depiscan study: a French randomized pilot trial of lung cancer screening comparing low dose CT scan (LDCT) and chest X-ray (CXR). Lung Cancer 2007; 58:50–58.. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Infante M, Lutman FR, Cavuto S, Brambilla G, Chiesa G, Passera E, et al. Lung cancer screening with spiral CT: baseline results of the randomized DANTE trial. Lung Cancer 2008; 59:355–363.. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toyoda Y, Nakayama T, Kusunoki Y, Iso H, Suzuki T. Sensitivity and specificity of lung cancer screening using chest low-dose computed tomography. Br J Cancer 2008; 98:1602–1607.. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veronesi G, Bellomi M, Mulshine JL, Pelosi G, Scanagatta P, Paganelli G, et al. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography: a non-invasive diagnostic protocol for baseline lung nodules. Lung Cancer 2008; 61:340–349.. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson DO, Weissfeld JL, Fuhrman CR, Fisher SN, Balogh P, Landreneau RJ, et al. The Pittsburgh Lung Screening Study (PLuSS): outcomes within 3 years of a first computed tomography scan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 178:956–961.. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-336OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopes Pegna A, Picozzi G, Mascalchi M, Maria Carozzi F, Carrozzi L, Comin C, et al. Design, recruitment and baseline results of the ITALUNG trial for lung cancer screening with low-dose CT. Lung Cancer 2009; 64:34–40.. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen JH, Ashraf H, Dirksen A, Bach K, Hansen H, Toennesen P, et al. The Danish randomized lung cancer CT screening trial - overall design and results of the prevalence round. J Thorac Oncol 2009; 4:608–614.. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a0d98f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Klaveren RJ, Oudkerk M, Prokop M, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Vernhout R, et al. Management of lung nodules detected by volume CT scanning. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2221–2229.. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Croswell JM, Baker SG, Marcus PM, Clapp JD, Kramer BS. Cumulative incidence of false-positive test results in lung cancer screening: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152:505–512., W176–180. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menezes RJ, Roberts HC, Paul NS, McGregor M, Chung TB, Patsios D, et al. Lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography in at-risk individuals: the Toronto experience. Lung Cancer 2010; 67:177–183.. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker N, Motsch E, Gross ML, Eigentopf A, Heussel CP, Dienemann H, et al. Randomized study on early detection of lung cancer with MSCT in Germany: study design and results of the first screening round. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2012; 138:1475–1486.. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pastorino U, Rossi M, Rosato V, Marchianò A, Sverzellati N, Morosi C, et al. Annual or biennial CT screening versus observation in heavy smokers: 5-year results of the MILD trial. Eur J Cancer Prev 2012; 21:308–315.. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328351e1b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rzyman W, Jelitto-Gorska M, Dziedzic R, Biadacz I, Ksiazek J, Chwirot P, et al. Diagnostic work-up and surgery in participants of the Gdansk lung cancer screening programme: the incidence of surgery for non-malignant conditions. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013; 17:969–973.. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sozzi G, Boeri M, Rossi M, Verri C, Suatoni P, Bravi F, et al. Clinical utility of a plasma-based miRNA signature classifier within computed tomography lung cancer screening: a correlative MILD trial study. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32:768–773.. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.50.4357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crucitti P, Gallo IF, Santoro G, Mangiameli G. Lung cancer screening with low dose CT: experience at Campus Bio-Medico of Rome on 1500 patients. Minerva Chir 2015; 70:393–399.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milch H, Kaminetzky M, Pak P, Godelman A, Shmukler A, Koenigsberg TC, et al. Computed tomography screening for lung cancer: preliminary results in a diverse urban population. J Thorac Imaging 2015; 30:157–163.. doi: 10.1097/rti.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Salcedo P, Wilson DO, de-Torres JP, Weissfeld JL, Berto J, Campo A, et al. Improving selection criteria for lung cancer screening. The potential role of emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191:924–931.. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1848OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.dos Santos RS, Franceschini JP, Chate RC, Ghefter MC, Kay F, Trajano AL, et al. Do current lung cancer screening guidelines apply for populations with high prevalence of granulomatous disease? Results from the First Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT1). Ann Thorac Surg 2016; 101:481–486.. discussion487-488. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Field JK, Duffy SW, Baldwin DR, Whynes DK, Devaraj A, Brain KE, et al. UK lung cancer RCT pilot screening trial: baseline findings from the screening arm provide evidence for the potential implementation of lung cancer screening. Thorax 2016; 71:161–170.. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritchie AJ, Sanghera C, Jacobs C, Zhang W, Mayo J, Schmidt H, et al. Computer vision tool and technician as first reader of lung cancer screening CT scans. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11:709–717.. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobs CD, Jafari ME. Early results of lung cancer screening and radiation dose assessment by low-dose CT at a Community Hospital. Clin Lung Cancer 2017; 18:e327–e331.. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marshall HM, Zhao H, Bowman RV, Passmore LH, McCaul EM, Yang IA, et al. The effect of different radiological models on diagnostic accuracy and lung cancer screening performance. Thorax 2017; 72:1147–1150.. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsu HT, Tang EK, Wu MT, Wu CC, Liang CH, Chen CS, et al. Modified lung-RADS improves performance of screening LDCT in a population with high prevalence of non-smoking-related lung cancer. Acad Radiol 2018; 25:1240–1251.. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meier-Schroers M, Homsi R, Skowasch D, Buermann J, Zipfel M, Schild HH, et al. Lung cancer screening with MRI: results of the first screening round. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2018; 144:117–125.. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhandari S, Tripathi P, Pham D, Pinkston C, Kloecker G. Performance of community-based lung cancer screening program in a histoplasma endemic region. Lung Cancer 2019; 136:102–104.. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crosbie PA, Balata H, Evison M, Atack M, Bayliss-Brideaux V, Colligan D, et al. Implementing lung cancer screening: baseline results from a community-based ‘Lung Health Check’ pilot in deprived areas of Manchester. Thorax 2019; 74:405–409.. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan L, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Li Q, Yang W, Wang S, et al. Lung cancer screening with low-dose CT: baseline screening results in Shanghai. Acad Radiol 2019; 26:1283–1291.. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaminetzky M, Milch HS, Shmukler A, Kessler A, Peng R, Mardakhaev E, et al. Effectiveness of lung-RADS in reducing false-positive results in a diverse, underserved, urban lung cancer screening cohort. J Am Coll Radiol 2019; 16 (4 Pt A):419–426.. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spiro SG, Shah PL, Rintoul RC, George J, Janes S, Callister M, et al. Sequential screening for lung cancer in a high-risk group: randomised controlled trial: LungSEARCH: a randomised controlled trial of surveillance using sputum and imaging for the EARly detection of lung cancer in a high-risk group. Eur Respir J 2019; 54:1900581.doi: 10.1183/13993003.00581-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tremblay A, Taghizadeh N, MacGregor JH, Armstrong G, Bristow MS, Guo LLQ, et al. Application of lung-screening reporting and data system versus pan-canadian early detection of lung cancer nodule risk calculation in the alberta lung cancer screening study. J Am Coll Radiol 2019; 16:1425–1432.. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leleu O, Basille D, Auquier M, Clarot C, Hoguet E, Pétigny V, et al. Lung cancer screening by low-dose CT scan: baseline results of a French prospective study. Clin Lung Cancer 2020; 21:145–152.. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei MN, Su Z, Wang JN, Gonzalez Mendez MJ, Yu XY, Liang H, et al. Performance of lung cancer screening with low-dose CT in Gejiu, Yunnan: a population-based, screening cohort study. Thorac Cancer 2020; 11:1224–1232.. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu CW, Ku YT, Huang CY, Hsieh PC, Lim KE, Tzeng IS, et al. The BUILT study: a single-center 5-year experience of lung cancer screening in Taiwan. Int J Med Sci 2021; 18:3861–3869.. doi: 10.7150/ijms.64648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang YZ, Lv YB, Li GY, Zhang DQ, Gao Z, Gai QZ. Value of low-dose spiral CT combined with circulating miR-200b and miR-200c examinations for lung cancer screening in physical examination population. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021; 25:6123–6130.. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202110_26890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoffman RM, Atallah RP, Struble RD, Badgett RG. Lung cancer screening with low-dose CT: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35:3015–3025.. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05951-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sadate A, Occean BV, Beregi JP, Hamard A, Addala T, de Forges H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the impact of lung cancer screening by low-dose computed tomography. Eur J Cancer 2020; 134:107–114.. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He J, Li N, Chen WQ, Wu N, Shen HB, Jiang Y, et al. China guideline for the screening and early detection of lung cancer (2021, Beijing) (in Chinese). Chin J Oncol 2021; 43:243–268.. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20210119-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moyer VA. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:330–338.. doi: 10.7326/m13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for lung cancer. CMAJ 2016; 188:425–432.. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Field JK, Smith RA, Aberle DR, Oudkerk M, Baldwin DR, Yankelevitz D, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer computed tomography screening workshop 2011 report. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7:10–19.. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823c58ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ritzwoller DP, Meza R, Carroll NM, Blum-Barnett E, Burnett-Hartman AN, Greenlee RT, et al. Evaluation of population-level changes associated with the 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force lung cancer screening recommendations in community-based health care systems. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2128176.doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kovalchik SA, Tammemagi M, Berg CD, Caporaso NE, Riley TL, Korch M, et al. Targeting of low-dose CT screening according to the risk of lung-cancer death. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:245–254.. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mazzone PJ, Lam L. Evaluating the patient with a pulmonary nodule: a review. JAMA 2022; 327:264–273.. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang W, Qian F, Teng J, Wang H, Manegold C, Pilz LR, et al. Community-based lung cancer screening with low-dose CT in China: results of the baseline screening. Lung Cancer 2018; 117:20–26.. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gierada DS, Pinsky P, Nath H, Chiles C, Duan F, Aberle DR. Projected outcomes using different nodule sizes to define a positive CT lung cancer screening examination. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106:dju284.doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]