ABSTRACT

Optimal patient care is directed by clinical practice guidelines, with emphasis on shared decision-making. However, guidelines—and interventions to support their implementation—often do not reflect the needs of ethnic minorities, who experience inequities in chronic kidney disease (CKD) prevalence and outcomes. This review aims to describe what interventions exist to promote decision-making, self-management and/or health literacy for ethnic-minority people living with CKD, describe intervention development and/or adaptation processes, and explore the impact on patient outcomes. Six databases were searched (MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Scopus, EMBASE, CINAHL, InformitOnline) and two reviewers independently extracted study data and assessed risk of bias. Twelve studies (n = 291 participants), conducted in six countries and targeting nine distinct ethnic-minority groups, were included. Intervention strategies consisted of: (i) face-to-face education/skills training (three studies, n = 160), (ii) patient education materials (two studies, n = unspecified), (iii) Cultural Health Liaison Officer (six studies, n = 106) or (iv) increasing access to healthcare (three studies, n = 25). There was limited description of cultural targeting/tailoring. Where written information was translated into languages other than English, the approach was exact translation without other cultural adaptation. Few studies reported on community-based research approaches, intervention adaptations requiring limited or no literacy (e.g. infographics; photographs and interviews with local community members) and the inclusion of Cultural Health Liaison Officer as part of intervention design. No community-based interventions were evaluated for their impact on clinical or psychosocial outcomes. All interventions conducted in the hospital settings reported favourable outcomes (e.g. reduction in blood pressure) compared with routine care but were limited by methodological issues.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, CKD, decision-making, ethnic minority, self-management

INTRODUCTION

Kidney disease is a global public health problem that affects more than 750 million people worldwide [1]. In many settings, rates of kidney disease and the provision of care are impacted by sociocultural factors, leading to significant disparities in disease burden, even in developed countries [2]. For example, it has long been recognized that chronic kidney disease (CKD) is more common in racial/ethnic-minority groups in the USA [3–5], UK, Australia and New Zealand [6, 7]. Furthermore, in countries where national surveillance data are available, there is evidence of an increased burden of CKD in indigenous populations [8]. Ethnic-minority groups also experience higher rates of progression of CKD and poorer outcomes [9]. To address this disparity, there have been calls for ‘innovative initiatives’ that target individuals at greatest risk of CKD to ensure they receive appropriate and timely intervention across the spectrum of the disease—from preventive efforts to curb development of CKD, to screening for kidney disease among persons at high risk, to accessing care and treatment for kidney failure [10]. This appeal necessarily includes targeted and tailored education efforts directed toward ethnic-minority populations to support informed decision-making, health literacy and self-management.

It is widely acknowledged that the long-term management of CKD presumes a high level of patient involvement in both decision-making and implementation of care. To this end, a shared approach to decision-making is recommended by both the Renal Physicians Association and the American Society of Nephrology [11]. Health literacy includes both the situational factors and the person skills that allow an individual to obtain, understand and utilize health information [12]. These skills are then used in tandem with patient communication so that healthcare professionals and patients can collaborate to select tests, treatments or management options based on both evidence-based medicine and a patient's values and preferences [13]. As such, there are a growing number of interventions to promote shared decision-making (such as patient decision aids [14, 15], and educational [16] and self-management programs), and build health literacy skills (such as supporting patients in interpreting complex health information, communicating values and preferences, and making decisions based on available information) for people living with chronic conditions including CKD. Previous research has indicated ethnic-minority patients are eager to participate in decisions that affect their health [17]. However, little is known about whether and how interventions have been targeted or tailored to different cultural and language groups.

The aim of this study was therefore to conduct a systematic review of the literature to:

identify interventions that have been developed or adapted to support ethnic-minority patients living with Stage 1 to 5 CKD or undergoing dialysis to improve their health literacy and/or participate in decision-making and self-management;

describe the development process of such interventions; and

explore the impact of these interventions on patient outcomes for ethnic-minority patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protocol and registration

A protocol for this systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42019145482). The review was conducted in accordance with best practice methodology [18] and is reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [19].

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported an intervention designed for ethnic-minority people living with CKD or described an existing intervention adapted for ethnic-minority CKD patients, and the intervention addressed health literacy, shared-decision making or self-management as either the aim of the intervention, or as an outcome measure.

Interventions that were previously published in other non-ethnic-minority populations and re-trialled in ethnic-minority populations were not eligible for inclusion unless there was specific adaptation to an ethnic-minority audience. Published studies of any design were eligible for inclusion, including observational cohorts and case reports. Interventions with kidney transplantation as the primary focus were not eligible for inclusion. Our rationale for excluding transplantation was that kidney transplantation is a complex, multi-factorial and one-off decision point that requires high health literacy, communication and shared decision-making skills [20]. The foundation of these skills should hence be established earlier in the CKD trajectory.

Information sources and search strategy

A comprehensive two-step search strategy was used to identify relevant studies, developed by four members of the research team (R.K., D.M.M., S.Z., A.C.W.) in consultation with a health information specialist librarian. Full-text language articles were identified and obtained through electronic searches of the following databases: MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Scopus, EMBASE, CINAHL and InformitOnline, in June 2021. The search strategy combined synonyms of the terms ‘Chronic Kidney Disease’, ‘ethnic-minority’ and ‘intervention or strategy’. The initial search strategy was formed using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) with free text terms (Appendix 1).

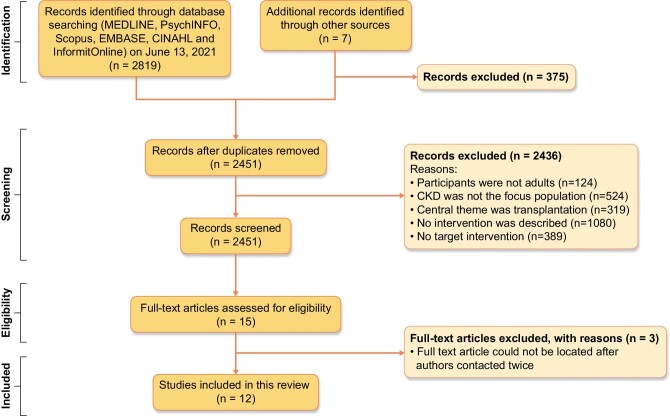

We decided a priori, and informed by prior work [21], not to include the specific intervention focus as a search term (i.e. intervention that addresses health literacy, education, shared-decision making, patient motivation, patient–provider communication, self-management) to minimize the risk of missing relevant articles that use various and somewhat inconsistent synonyms of these concepts. Search results were screened for relevance by title and abstract (R.K., S.Z.). Reference lists of included studies were also searched for other relevant citations, which were reviewed in full-text if the title or abstract suggested they may be eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

PRISMA diagram showing identification of published studies for inclusion in review.

Study selection

The full text of selected studies was reviewed to confirm eligibility, with disagreements resolved by consensus between all members of the research team. Where full texts could not be obtained, corresponding authors were contacted for access to full-text articles.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

An electronic data extraction spreadsheet was iteratively developed and piloted by three authors (R.K., D.M.M., S.Z.). The data extracted included basic information about the study (author, year of publication), study details (country, study design), population characteristics (sample size, age, sex, ethnicity, language, CKD stage and literacy), type of intervention (format, language, setting), information relevant to the development of the study (adapted from an existing published study or novel intervention, the development process) and whether the intervention was evaluated for improvement in primary and secondary outcome measures. Data were then extracted into evidence tables independently by two authors (R.K., S.Z.) and areas of conflict resolved through whole–research team discussion. Randomized control parallel or crossover trials and feasibility studies were critically appraised using the Joanna Briggs Institute Appraisal Tool, whilst narrative summaries of intervention development and case reports were appraised using the Meta Quality Appraisal Tool [22, 23]. Two raters independently critically appraised articles using the relevant checklists (R.K., J.I.) and any discrepancies were resolved through whole-team discussion.

Summary measures and synthesis of results

This review reconciled the heterogeneity of intervention designs through a narrative synthesis of the interventions identified, their development process, and their primary and secondary outcome measures. Articles were analysed with reference to the three aims of this review: first with reference to the overarching themes (decision-making, health literacy, self-management strategies) addressed in each intervention, second, by their description of intervention development process and cultural adaptation, and finally articles were compared by their methodological rigor and quantitative evaluation.

RESULTS

Study selection

Some 2826 articles were identified from the database and reference list searches. After title, abstract and full-text screening, 2814 articles were excluded, resulting in 12 studies that were included in this systematic review (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Of 12 studies included in the final review, there was one randomized controlled parallel trial (RCT) [24], one randomized crossover trial [25] and two feasibility studies for RCTs [26, 27]. Two studies included a qualitative evaluation of an intervention [28, 29]. Four articles were narrative summaries of intervention development [29–32], and the remaining two articles were case reports [33, 34]. The majority of studies (n = 7) did not report the baseline characteristics of participants. In studies where this was reported, male and female participants were included and the median age ranged from 58 to 75 years [24–27].

Studies included in this review were developed in Australia (n = 4) [26, 28, 31, 32], the USA (n = 3) [25, 27, 34], South Africa (n = 1) [30], New Zealand (n = 1) [24], Canada (n = 1) [29] and the UK (n = 1) [33] (Table 1). Five studies were conducted in hospitals [25–27, 30, 34], four in community-based settings [28, 29, 31, 32], and two in a combination of both [24, 33]. The studies addressed nine distinct ethnic-minority groups: Latinx and African Americans; Greek, Italian, Vietnamese and Aboriginal Australians; British Asians; Maori New Zealanders; and First Nations Canadians. All studies except one specified a language and ethnic background of target participants; Verseput and Piccoli [30] targeted all culturally diverse, non-English-speaking South Africans. Five studies focused on developing interventions for First Nations Peoples and were conducted in Australia, New Zealand and Canada [24, 28, 29, 31, 32]. Of the three studies published in the USA, two had a sample population of English-speaking African Americans [25, 27].

Table 1:

Existing interventions and their development process.

| Study demographics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | Language/ethnicity | Sample size [n (% male)] | Age (years)a | CKD stage | Setting | Intervention description | Development and/or cultural adaptation process |

| Williams (2012) | Australia | Greek-, Italian- or Vietnamese-speaking patients | 29 (63) | Mean: 74 | 2–4 | Nephrology outpatient clinics at a public, tertiary, metropolitan hospital | Intervention to increase medication compliance over 3 months, consisting of: - Individualized medication review by nurse - 20-min educational presentation - Fortnightly motivational interviewing |

Adapted from Williams et al. (2010) |

| Previous literature review and pilot interventions are described in Williams et al. (2010) | ||||||||

| For current study, presentation was translated into community languages and modified for cultural sensitivity. Hospital interpreters and translators were used for face-to-face or phone interactions | ||||||||

| Themes: SDM, HL (education), self-management strategies | ||||||||

| Tracey (2013) | Australia | Aboriginal Australians | b | b | 1–5 | Community based in the remote Goldfields region of Western Australia | Clinical nurse manager, (educator, community nurse) and AHW provided collaborative care to Indigenous CKD patients in remote settings | Novel intervention Nursing team collaborated with AHW to design culturally appropriate patient education materials and training for staff on Aboriginal culture and sensitivity. Priority areas of the community health service were determined in partnership with state-wide care providers and via community consultation. The study aimed to improve the patient journey |

| Themes: HL (education, access to healthcare) | ||||||||

| Barrett (2015) | Australia | Aboriginal Australians | b | b | 1–4 | Community nephrology clinics in a rural town (Kempsey, NSW, Australia) | Development of a new CKD outreach clinic with a nurse practitioner–led team that includes AHWs, chronic disease nurses and GPs. Clinic aimed to identify undiagnosed CKD patients, treat their underlying conditions and provide them with access to healthcare from nurses and doctors | Novel interventionThe article did not justify the intervention design. There was no discussion of how this intervention is culturally sensitive and safe for a vulnerable population group |

| Themes: HL (access to healthcare) | ||||||||

| Conway (2018) | Australia | Aboriginal Australians | 25 | b | 5 | Rural and remote communities in South Australia | Semi-structured interviews with 15 dialysis patients and 10 staff across 9 sites services by a dialysis busThemes: HL (access to healthcare) | Novel interventionLiterature review highlighted that leaving Aboriginal country or homeland caused feelings of grief and loss and financial burden for Indigenous Australians. Semi-structured ‘yarning’ style interviews were conducted |

| Paterson (2010) | Canada | Aboriginal Canadians | b | b | 5 | Community based in Elsipogtog First Nation, Canada | Newly diagnosed patients commencing haemodialysis provided with toolkit containing: - Five 20-min DVDs - Written manual - Calendar diary Themes: SDM, HL (education, access to healthcare) self- management strategies |

Novel intervention This study utilized a community-based research approach. First, a review of relevant literature was conducted. Then, a Community Advisory Committee was formed. This committee conducted individual interviews with key stakeholders, discussed results, synthesized key themes from interviews, and determined the educational content of the toolkit through an iterative process |

| Hotu (2010) | New Zealand | Maori and Pacific Islanders | 65 (54) | Range: 47–75 | 1–4 | Recruited through hospital diabetes/renal care clinics and primary care practices | Utilisation of a Maori and Tongan healthcare assistant, who:- Visited patients - Measured BP - Checked compliance with medication - Provided transport to pharmacy, pathology laboratory and/or local doctorThemes: HL (access to healthcare) |

Novel interventionAimed to provide collaborative, community-based care to Maori/Pacific patients. Conducted an initial literature review that concluded that Maori/Pacific patients may have higher BP, lower family income and more language barriers compared with non-Maori/Pacific CKD patients. The study did not describe any cultural targeting or tailoring beyond employing a Maori and Tongan healthcare assist to provide community care for the intervention group |

| Verseput and Piccoli (2017) | South Africa | Non-English-speaking patients | b | b | 1–5 | Renal unit of a hospital | Pictorial visual aid for renal diet education for newly diagnosed CKD patientsThemes: HL (education), self- management strategies | Novel interventionDiscussed key points of nutrition education for new CKD patients and created a novel visual aid using pictures and analogies to describe concepts (e.g. kidney as a sieve). Tested for feasibility and adapted accordingly (e.g. men did not understand concept of sieve so changed to a car filter) |

| Akhtar (2014) | UK | Urdu- and Punjabi-speaking South Asian Brits | b | b | b | Hospital visits and community outreach | Design of a novel role: CHLO who speaks English, Urdu and Punjabi and has ‘greater sensitivity to the holistic needs of patients’. The CHLO would discuss and explain issues, answer questions, clarify misconceptions and to assist in decision makingThemes: HL (education, access to healthcare) | Novel interventionThe article does not discuss how the CHLO role was designed, whether it was modified from an existing role or any literature relevant to the role |

| Beechem (1995) | USA | Spanish-speaking Mexican-American | 1 (0) | b | 5 | Hospital and hospice | Provision of health services in both English and Spanish through social worker coordinating culturally competent care– Designing a treatment plan for the patient, staff and family to followThemes: self- management strategies, HL (access to healthcare) | Novel interventionThe Spanish-speaking social worker was able to explain the patient's condition and progression in Spanish. This social worker designed a treatment plan for the patient, staff and family to follow that was based upon both best-clinical practice as advised by the healthcare team, but also validated the patient's desire for a ‘Cuarandero’ (a natural healer). The social-worker assisted the patient's family adapt Mexican food recipes to be dialysis friendly and facilitated end-of-life hospice care |

| Song (2009) | USA | English speaking African-Americans | 58 dyads (48) | Mean: 58 | 5 | 6 outpatient dialysis clinics | Patient and surrogate decision-maker dyads have a 1-h interview and training with an experienced nurse interventionist. Used training manuals, role playing and skill demonstration to teach competency in five main areasThemes: HL (education) | Adapted from Song (2005)No description of development processEach intervention session was recorded and monitored for content and process fidelity (consistent content and consistent communication skills used) |

| Park (2014) | USA | English speaking African-American veterans | 15 (100) | Range: 51–66 | 3 | Medical research centre | Decrease BP in hypertensive CKD patients through 14 min of mindfulness meditation (intervention), or 14 min of BP education (control) during two separate random-order visitsThemes: self-management strategies | Adapted from Bauer-Wu et al. (2008)Utilized a guided meditation tape previously designed by a co-investigator [43]. This tape was initially designed for oncology patients, and there was no adaptation for this study's population |

| Cervantes (2019) | USA | English- or Spanish-speaking Latinos | 40 (50) | Mean: 56 | 5 | Inpatient and outpatient dialysis centres | An English and Spanish speaking Latina patient navigator visits patients five times to discuss Advance Care Planning, care coordination, dietary support and mental health supportThemes: education, self-management strategies | Novel interventionPrevious research by same authors indicated the needs and preferences of Latinx CKD patients. An advisory panel (patient and caregiver stakeholders) provided guidance on the content and delivery of the patient navigator intervention |

aAs reported by the study authors.

bUnspecified.

AHW, Aboriginal healthcare workers; BP, blood pressure; CHLO, Cultural Health Liaison Officer; GP, general practitioner; HL, health literacy; SDM, shared decision-making.

Stages of CKD varied across all 11 studies [35]. Two studies [30, 31] included participants from all CKD stages [Stage 1 (early disease) to Stage 5 (requiring dialysis)], with an additional two studies including pre-dialysis CKD. Four studies focused on dialysis participants only, emphasizing the great treatment burden, which requires a high level of patient education and health literacy, dietary modification and access to healthcare services [27–30]. One study [33] did not specify which stage of CKD their intervention aimed to address.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisals for each of the individual studies are shown in Table 2. All interventions included in this review were limited by small sample size (range, n = 1–65).

Table 2:

Quality appraisal and impact of interventions on patient outcomes.

| Impact of interventions on patient outcomes, and quality appraisal of studies using the Joanna Briggs Appraisal Tool | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (country) | Study design | Control | Risk of bias: Joanna Briggs Critical Appraisal | Primary outcome measure | Conclusions | Random sequence generation | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias |

| Williams (2012) | Feasibility study for double-site, single-blinded longitudinal RCT Randomization: stratified by ethnicity, then randomized by age and gender using a purpose-built randomization sequence computer program |

Routine care of outpatient clinics and primary care | • Did not report if groups had similar characteristics at baseline • Unclear whether outcomes were measured in a reliable way (did not include number of raters, training or raters or inter/intra-rater reliability) • Did not provide quantitative data of results (only qualitative summary sentences) |

Medication self-efficacy and adherence | No significant difference in medication self-efficacy, medication adherence, general wellbeing, healthcare utilization and routine clinical laboratory surrogate measures at each data collection time point |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hotu (2010) | RCT Randomization: unspecified |

Routine family doctor and/or renal/diabetes hospital clinical care | • Did not specify method of randomization | Changes in office BP (systolic and diastolic) | Community care patients had a significantly greater reduction in systolic BP at 12 months when compared with the control group |

|

|

|

|

|

| Song (2009) | Feasibility study for a RCT Randomization: permuted block randomization using sequential, opaque, numbered envelopes |

Routine care of a once-only session with a social worker urging patients to complete an Advanced Care Directive | • Overall rigorous study design: described method of randomization and loss to follow-up | Feasibility: attrition rates comparison between intervention/control arm, and the median and mean minutes for the nurse to complete the intervention Acceptability: Patient–Clinician Interaction Index scores at baseline, 1 week and 3 months |

Feasibility: attrition was similar between both groups Acceptability: quality of communication scores of both patients and surrogates were higher in the intervention group at all time points |

|

|

|

|

|

| Park (2014) | Randomized crossover study Randomization: unspecified |

Audio-recorded BP education | • Did not specify method of randomization, or if there was the loss of any study participants to follow-up | Changes in BP (systolic, diastolic, mean arterial pressure), heart rate and muscle sympathetic nerve activity | There was a significantly lower systolic, diastolic, mean arterial pressure and heart rate in the intervention group compared with controls. There was a significantly greater reduction in MSNA in the intervention group compared with the control intervention. There was no difference in respiratory rate between groups |

|

|

|

|

|

| Quality appraisal of studies using meta quality appraisal tool | |||||

| Study | Study design | Relevancy | Reliability | Validity | Applicability |

| Akhtar (2014) | Narrative description of intervention development and implementation process | Use of a cultural and health improvement officer for South Asian patients in Bradford, UK | • The aim of the intervention is not clearly outlined • Clearly defined role of the cultural health officer • No reporting of the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the participants eligible to work with the health officer • Did not cite ethics approval |

There is comprehensive discussion of the role of the health officer rationalized by the unique health needs of the South Asian CKD population There is no statistical analysis of impact of the intervention. There are two anecdotal case studies of the impact of a health officer on patient care |

The role of the healthcare officer is comprehensively defined and encompasses not only CKD management, but also holistic wellbeing, immigration and social services |

| Barrett (2015) | Narrative description of intervention development and implementation process | Provision of community nephrology clinics at an Aboriginal Medical Service in rural NSW, Australia | • Clearly states aims • No reporting of inclusion/exclusion criteria or pre-intervention rates of CKD • Methods of identifying undiagnosed CKD patients clearly described • No statistical analysis of data • Did not cite ethics approval |

Methodology for identifying CKD patients appropriate to aim Methodology addressing secondary aims of community awareness, education programs and management plans insufficiently described Potential sampling bias in methodology as CKD was only tested for in those with specific risk factors |

The study highlights the role of upstream chronic health disease in CKD development. Methods of identifying new CKD patients were appropriate to a vulnerable and geographically difficult to access high health needs population There was insufficient description of how or why the aims, methodology or interventions of this study are culturally targeted and tailored to the Durri Aboriginal people |

| Paterson (2010) | Narrative case report of intervention development process | Co-design of a health resources toolkit for Elsipogtog First Nation's people living with CKD | • Clearly states aims • Methods of intervention development, including cultural targeting and tailoring well characterized • No pre- and post-test measures of success of the intervention • Study approved by an ethics board |

Comprehensive description of the methodology of intervention description, from stakeholder interviews, identifying key themes and the creation and implementation of the educational resource The methodology is appropriate for the aims There is no evaluation of the impact of the intervention on patient clinical and/or psychosocial outcomes |

Recognized governing principles of Community Based Participatory Research Formed ethical partnerships with local communities, including creating a Memorandum of Understanding Thorough description of the intervention creation that recognizes both cultural targeting and tailoring. Considers accessibility and practical aspects of implementation during intervention design |

| Tracey (2013) | Narrative description of intervention development and implementation process | Nursing-managed kidney disease program in rural Aboriginal communities in Western Australia | • Clearly states aims • No reporting of inclusion/exclusion criteria of participants, or of their baseline demographics • There is description of the program structure, but no justification of the cultural appropriateness, targeting and tailoring of intervention development • Did not cite ethics approval |

There is comprehensive justification of how the intervention methodology overcomes the practical barriers of providing greater access to care There may be some reporting bias. There are some descriptive statistics of pre- and post-intervention measures, but not for all of the primary aims. It is unclear the number of people the intervention was trialled in, which may limit external validity |

The intervention forms partnerships with multiple levels of allied health, government and other organisations The intervention has not been tested for acceptability to the local Indigenous Australian population |

| Verseput and Piccoli (2017) | Narrative description of intervention development process | A visual aid educational tool teaching renal diet principles for illiterate or non-English-speaking South Africans | • Clearly states aims • No reporting of inclusion/exclusion criteria or pre-intervention knowledge of renal diet • Methods of intervention development were well described, including rationale for the content and format • No statistical analysis of data • Did not cite ethics approval |

Comprehensive description of the methodology of intervention description, including an iterative design process influenced by patient feedback There may be sampling bias and a limited external validity as it is unclear of who (age, gender, demographics) the intervention was trialled in |

This intervention comprehensively justified the content and format of education. There was some tailoring to different genders after feedback from consumers |

| Conway (2018) | Narrative description of intervention development process and qualitative evaluation | A South Australian Mobile Dialysis Truck, which visits remote communities for one to two week periods to improve access to dialysis for remote Indigenous Australian communities | • Clearly states aim • Cites ethics approval • Minimal description of participant recruitment process • No description of exclusion criteria • Methods for qualitative interviews clearly described • Provides qualitative evaluation of intervention |

There may be sampling bias and a limited external validity as the study does not report the baseline demographics of participants The methodology is appropriate for the aims There is qualitative (but no quantitative) evaluation of the impact of intervention on patient quality of life and satisfaction with service provision |

There is comprehensive description of how an iterative interview schedule was created and adapted to the cultural concept of ‘yarning’. The qualitative evaluation of intervention, including participant priority-setting of outcome measures, may be useful for future studies |

| Beecham (1995) | Narrative description of a case report | A social worker provides a case report of the cultural accommodations made for a young, Mexican-American patient living with CKD | • Does not clearly state aims of social work intervention • Does not cite ethics approval • Narrative description of the strategies employed to engage a culturally diverse patient • Provides some patient qualitative feedback |

There is a small sample size of one person, lending to sampling bias and limited external validity The demographics of the participant, apart from cultural background, are not reported There is minimal qualitative, and no quantitative evaluation of the impact of intervention on the patient's care |

The case report promotes patient autonomy, participation in decision-making and promotes the co-existence of both Western and traditional Mexican Cuarandero's role in health and wellbeing |

| Cervantes (2019) | Single-arm prospective study | A peer navigator program for Latinx patients on haemodialysis, providing assistance with advance care planning, care coordination, and counseling about the importance of diet and mental health | • Clearly states objectives • Cites ethics approval • Reports inclusion and exclusion criteria • Baseline demographics of participants are reported • There are some descriptive statistics of impact of intervention on patient reported quality of life |

There is some description of how themes were delineated, and the training peer navigators received There is minimal attrition bias. The study used validated questionnaires and scales. There is some reporting of descriptive statistics of impact of the intervention on patient reported outcomes. There is no reporting of pre- and post-test measures |

The intervention justified format and content of the peer navigator program. The combination of quantitative (descriptive statistics) and qualitative (patient feedback) evaluation may be useful in further understanding acceptability and feasibility of the interventionF |

BP, blood pressure; MSNA, muscle sympathetic nerve activity.

Four interventions were evaluated for their impact on quantitative primary and secondary outcome measures using Joanna Briggs Critical Appraisal Tool [24–27]. Of these four studies, none could blind to participants or personnel due to the different nature of interventions. Two studies specified their method of randomization [26, 27]. Two studies had unclear risk of bias related to loss to follow-up.

The remaining seven studies were examined using the MetaQAT Critical Appraisal Tool, which examines the relevancy, reliability, validity and applicability of study findings. These studies were lower-quality evidence such as case reports, reflecting the overall dearth of high-quality, rigorous methodology in this area. None of these studies used pre- and post-test measures to determine the impact of intervention on patients’ outcomes.

Interventions

The interventions addressed one or more of three core themes of shared decision-making across a variety of CKD decision points, health literacy (including access to health information and services) and/or self-management skills. The format of interventions consisted of: (i) face-to-face education/skills training, such as training in medication management or shared decision-making, (ii) take-home patient education materials such as DVDs, brochures or infographic aids, (iii) inclusion of a Cultural Health Liaison Officer or similar in the multi-disciplinary healthcare team, who shares the same language and cultural group as the target ethnic-minority patient or (iv) service restructuring to increase access to care for those in rural or remote locations, either through a mobile dialysis bus or nursing-led clinics. Two studies used a dual modality of a cultural health liaison officer and nursing-led clinics in remote areas [31, 32].

Shared decision-making interventions addressed decision points such as the choice to take a medication or organizing end-of-life care. Self-management skills included medication reviews and education sessions, telephone motivational interviewing and guided mindfulness meditation sessions. Health literacy interventions promoted patient access to and understanding of care through infographic aids, audio-visual resources tailored for a low-literacy, non-English-speaking audience or key coordinators (a Cultural Health Liaison Officer, a Healthcare Assistant or a nursing-led model of care). Most studies addressed more than one of these themes, illustrating both the complexity of adapting to living with a chronic, high-burden condition, and the diverse requirements of different cultural groups.

Intervention development process

Three of the studies included in this review implemented interventions that had been adapted for an ethnic-minority CKD population from an existing published intervention [25–27]. These interventions had been previously trialled in other chronic disease or CKD patient cohorts [36, 37]. The remaining eight studies included uniquely designed interventions for ethnic-minority CKD patients.

The most common method for adaption of interventions to an ethnic-minority audience were through language translation. Verseput and Piccoli [30] attempted to cater to multiple ethnic-minority groups in their diverse, multi-lingual South African population by designing an infographic patient education aid that required no literacy. They utilized an iterative process in the intervention design that included initially identifying the failures of common diet education tools in the South African context (the ‘food pyramid’ often misinterpreted as the ‘best is at the very top’), then implementing an alternative design or metaphor. For instance, the analogy of a kidney as a ‘sieve’ was poorly understood by male participants and was thereafter adapted to a ‘clogged car oil filter’ [30].

When written information was translated into languages other than English, the approach was usually word-for-word translation, without other cultural adaptation. One study ‘modified original health jargon for cultural sensitivity’ but provided no specific explanation of this [26]. One study conducted extensive qualitative interviews with their patient population to create a unique patient education resource that included the traditional language of Mik'maq with English translations, a shorter DVD length, featured photographs and interviews with local First Nations Canadians, and included low-literacy and vision-impairment adaptations [29]. Other studies utilized a Cultural Healthcare Worker of the same ethnic-minority background as the patient population [24, 31–34]. These are health workers and cultural support personnel that typically share the same cultural, language and/or ethnic background as the patients they serve. Their role may include, but not be limited to: translation at healthcare appointments of medical information to a patient's first language, cultural adaption of health information (including addressing misconceptions and concerns), assisting patients to adapt health information to their lifestyle (e.g. suggesting renal-friendly diet adaptations of popular cultural dishes), liaising with a patient's family to further include them in decision-making and to make patients feel more at ease in healthcare settings. However, none of these studies discussed the training these workers received or strategies they employed to better engage with their ethnic-minority patients.

Studies trialled in First Nations Peoples more explicitly linked their historical, cultural, socio-economic and political discrimination to adverse health outcomes, and tailored their intervention design with these factors in mind. For instance, Paterson et al. [29] acknowledged Canadian Indigenous Elsipogtog collectivist attitudes to healthcare decisions and therefore included Elders, family members and current dialysis patients in their research group. Their community-based research approach enabled these members to play an active role in the development of the study concept, as well as partake in research activities. These community members hand-delivered invitations, conducted interviews and delineated major themes for the patient resources. As a result, themes such as ‘storytelling as a benefit’, which are absent from mainstream CKD resources, emerged as important, and were made more prominent in the audio-visual resources. Importantly, Paterson et al. [29] was the only study to recognize cultural tailoring, acknowledging that ‘one Aboriginal person is not the same as the next’ and therefore included multiple methods to explain similar health concepts.

Impact of interventions on patient outcomes

Whilst community, out-of-hospital based interventions were mostly targeted and tailored to an ethnic-minority audience, none was evaluated for their impact on patients’ clinical and psychosocial outcomes. In contrast, all four interventions conducted in hospital settings quantitatively evaluated their impact on primary and secondary outcomes [24–27]. Whilst these studies represented a higher quality of evidence, there were still methodological issues in their design and evaluation (Table 2). Overall, these four evaluated studies found that their intervention groups experienced more favourable outcomes (e.g. reduction in blood pressure) compared with routine care. The exception to this was the study by Williams et al. [26], which found no differences in medicine self-administration, adherence or general wellbeing between the control group and intervention group which received a medication review and motivational interviewing at every time point. This study experienced high attrition rates, which reduced the sample size greatly and decreased the power of the study [26].

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified few interventions that have been developed or adapted to support ethnic-minority patients living with CKD to participate in decision-making, or improve their health literacy or self-management skills. There was limited explicit cultural targeting and tailoring beyond language translation to adapt interventions to an ethnic-minority audience and inadequate descriptions of the development process for novel interventions. Very few of the included articles explored the impact of their intervention on patients’ clinical and psychosocial outcomes, making it difficult to comment on the efficacy of culturally tailored interventions. The overall paucity of studies reflects that tailored CKD interventions remain a relatively emerging field without the highest quality of evidence as standard yet. Although studies of poor methodological rigor (including small sample sizes and insufficient evaluation) provide some insights into the development process of culturally safe interventions, our review highlights a persisting gap in the literature and an ongoing need for interventions designed to assist ethnic-minority patients navigate a complex, high-burden disease process.

The broader literature on culturally adapted interventions indicates that many have been created to assist ethnic-minority patients living with cardiovascular disease [38], diabetes [39] or to participate in national cancer screening programs [40]. In comparison, this systematic review is the first to examine interventions to assist ethnic-minority patients with CKD. The findings of this review echo the existing literature of ethnic-minority healthcare in other chronic diseases, whereby the most common intervention strategies are the use of interpreters and Cultural Health Workers, and less commonly the design of tailored patient education materials [41]. Most written interventions have focused on translation of text, rather than cultural adaptation, suggesting that Haffner's 1992 sentiments that ‘translation is not enough’ remain relevant today [42]. Indeed, healthcare for ethnic-minority patients should not only be bilingual, but also bicultural, requiring more than just mechanical translation between English and other languages. Future interventions could potentially learn from studies conducted in Indigenous or First Nations Peoples, which tended to be more explicit in forming ethical partnerships in community-based research, with developed interventions reflecting cultural targeting and tailoring far beyond simple translation.

Although the available evidence was limited, the studies included valuable insights into the development process of culturally safe, evidence-based, consumer-designed interventions. From these existing studies, core strengths and opportunities for improvement can be delineated, and this knowledge capitalized on in the development of future interventions. Most importantly, there is a need to form ethical partnerships with communities to ensure that interventions are co-designed to include cultural views and realities and to support meaningful implementation and data collection. Our review also highlights the need for greater transparency in terms of the reporting of intervention development and cultural adaptation processes. Complete published descriptions of intervention adaption and cultural tailoring processes will better enable researchers to replicate and build on research findings and implement similar adaptation strategies for their own populations.

Strengths and limitations

This review closely examines studies for an underserved population of ethnic-minority patients living with CKD. Strengths include no limits on cultural groups included, a broad search strategy (no intervention-specific search terms, which increased the scope of available literature and decreased the likelihood of missing relevant articles) and quality assessment by two independent evaluators. However, our search strategy included only published studies, potentially introducing publication bias. Further, CKD is often the result of relevant upstream chronic disease processes (such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus) that require similar, transferable skills of health literacy, medication/dietary self-management and shared decision-making. We did not assess the impact of interventions published in non-ethnic minority populations which were re-trialled in ethnic-minority populations. Therefore, we are unable to comment on whether these interventions may be generalizable to ethnic minorities. Also, importantly, it is possible that many interventions and patient information materials are translated and adapted without evaluation or publication as a study. As this review did not explore the grey literature, these would not be captured in our data. Finally, interventions targeting transplantation as a decision-point were excluded as this decision-point is often a late-stage decision in the CKD disease trajectory, and requires highly specialized, specific skills and information. Ethnic-minority patients experience disparities in waitlist time, overall transplantation rates and long-term post-transplantation outcomes [20], and thus, this remains an important gap in the literature that should be addressed by future studies.

CONCLUSION

Few interventions exist that have been developed or adapted to support ethnic-minority patients living with CKD to improve their health literacy and participate in decision-making and self-management. Of the few existing interventions, there is inadequate description of the development process and the process of cultural adaptation. This limits the replicability of this work. Furthermore, there is also insufficient evaluation of the impact of these interventions on patient-reported, clinical and psychosocial outcomes. Moving forward, there is a need to prioritize intervention co-design and collaboration with ethnic-minority consumers. Future studies should also explicitly justify the nature of their cultural adaptation and undergo rigorous evaluation of the impact on patient and clinical outcomes. Such work is necessary to begin to redress the enormous inequities in CKD.

APPENDIX 1: SEARCH STRATEGY

| # | Search Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp Renal Insufficiency, Chronic/ |

| 2 | (chronic kidney adj4 (insufficienc* or failure* or disease*)).tw. |

| 3 | (chronic renal adj4 (insufficienc* or failure* or disease*)).tw. |

| 4 | (renal disease adj4 endstage).tw. |

| 5 | CKF.tw. |

| 6 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 |

| 7 | Culturally Competent Care/ |

| 8 | Cultural diversity/ |

| 9 | Transcultural Nursing/ |

| 10 | exp communication barriers/ |

| 11 | Healthcare Disparities/ |

| 12 | exp Ethnic Groups/ |

| 13 | Minority Groups/ |

| 14 | (multicultural or multilingual or transcultural or cross?cultural or multiracial).tw. |

| 15 | (divers* adj4 (cultur* or linguistic or ethnic*)).tw. |

| 16 | refugee*.tw. |

| 17 | (group* adj4 (minorit* or religio* or racial)).tw. |

| 18 | (CLD or CALD or ESL or NESB).tw. |

| 19 | ((culturally competent or culturally informed) adj4 (care or caring or strateg* or intervention* or therap* or communication* or healthcare)).tw. |

| 20 | 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 |

| 21 | 6 and 20 |

| 22 | limit 21 to “all adult (19 plus years)” |

Contributor Information

Roshana Kanagaratnam, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Stephanie Zwi, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia; The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney Health Literacy Lab, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Angela C Webster, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Centre for Transplant and Renal Research, Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia; NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Jennifer Isautier, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Kelly Lambert, Discipline of Nutrition and Dietetics, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health, School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia; Illawarra Health and Medical Research Institute, Wollongong.

Heather L Shepherd, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Science, School of Psychology, Centre for Medical Psychology and Evidence-based Decision-making (CeMPED), Sydney, NSW, Australia; The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Susan Wakil School of Nursing, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Kirsten McCaffery, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia; The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney Health Literacy Lab, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Kamal Sud, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Nepean Clinical School, NSW, Australia; Department of Renal Medicine, Nepean Hospital, NSW, Australia.

Danielle Marie Muscat, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia; The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Public Health, Sydney Health Literacy Lab, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Research idea and study design: D.M.M. and A.C.W.; data acquisition: R.K. and S.Z.; data analysis/interpretation: R.K., S.Z. and J.I.; editorial advice, supervision and mentorship: D.M.M., K.L., A.C.W., H.L.S., K.M. and K.S. Each author contributed important intellectual content during the manuscript drafting and revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy and integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1. Global , regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet North Am Ed 2016;388:1603–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crews DC, Hall YN. Social disadvantage: perpetual origin of kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2015;22:4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Easterling RE. Racial factors in the incidence and causation of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). ASAIO J 1977;23:28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rostand SG, Kirk KA, Rutsky EAet al. Racial differences in the incidence of treatment for end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med 1982;306:1276–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferguson R, Grim CE, Opgenorth TJ. The epidemiology of end-state renal disease: the six-year South-Central Los Angeles experience, 1980-85. Am J Public Health 1987;77:864–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McDonald SP, Russ GR, Kerr PGet al. ESRD in Australia and New Zealand at the end of the millennium: a report from the ANZDATA registry. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;40:1122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McDonald SP, Russ GR. Current incidence, treatment patterns and outcome of end-stage renal disease among indigenous groups in Australia and New Zealand. Nephrology 2003;8:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease: Australian facts: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Cat. No. CKD 5). Canberra: AIHW, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hounkpatin HO, Fraser SDS, Honney Ret al. Ethnic minority disparities in progression and mortality of pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease: a systematic scoping review. BMC Nephrol 2020;21:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Norris KC, Agodoa LY. Unraveling the racial disparities associated with kidney disease1. Kidney Int 2005;68:914–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galla JH. Clinical practice guideline on shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis. The Renal Physicians Association and the American Society of Nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000;11:1340–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam Jet al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012;12:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muscat DM, Shepherd HL, Nutbeam Det al. Health literacy and shared decision-making: exploring the relationship to enable meaningful patient engagement in healthcare. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36:521–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patzer RE, Basu M, Larsen CPet al. IChoose kidney: a clinical decision aid for kidney transplantation versus dialysis treatment. Transplantation 2016;100:630–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ameling JM, Auguste P, Ephraim PLet al. Development of a decision aid to inform patients’ and families’ renal replacement therapy selection decisions. BMC Med Inf Decis Making 2012;12:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghahramani N. Potential impact of peer mentoring on treatment choice in patients with chronic kidney disease: a review. Arch Iran Med 2015;18:239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muscat DM, Kanagaratnam R, Shepherd HLet al. Beyond dialysis decisions: a qualitative exploration of decision-making among culturally and linguistically diverse adults with chronic kidney disease on haemodialysis. BMC Nephrol 2018;19:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler Jet al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff Jet al. The PRISMA Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grubbs V, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJet al. Health literacy and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Campbell Z, Stevenson J, McCaffery Ket al. Interventions for improving health literacy in people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moola S, Munn Z, Sears Ket al. Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): the Joanna Briggs Institute's approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:163–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E. JBI's systematic reviews: data extraction and synthesis. Am J Nurs 2014;114:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hotu C, Bagg W, Collins Jet al. A community-based model of care improves blood pressure control and delays progression of proteinuria, left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction in Maori and Pacific patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:3260–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park J, Lyles RH, Bauer-Wu S. Mindfulness meditation lowers muscle sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in African-American males with chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2014;307:R93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williams A, Manias E, Liew Det al. Working with CALD groups: testing the feasibility of an intervention to improve medication selfmanagement in people with kidney disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ren Soc Australas J 2012;8:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song M, Ward SE, Happ MBet al. Randomized controlled trial of SPIRIT: an effective approach to preparing African-American dialysis patients and families for end of life. Res Nurs Health 2009;32:260–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Conway J, Lawn S, Crail Set al. Indigenous patient experiences of returning to country: a qualitative evaluation on the Country Health SA Dialysis bus. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paterson BL, Sock LA, LeBlanc Det al. Ripples in the water: a toolkit for Aboriginal people on hemodialysis. CANNT J 2010;20:20–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Verseput C, Piccoli GB. Eating like a rainbow: the development of a visual aid for nutritional treatment of CKD patients. A South African project. Nutrients 2017;9:435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tracey K, Cossich T, Bennett PNet al. A nurse-managed kidney disease program in regional and remote Australia. Ren Soc Australas J 2013;9:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barrett E, Salem L, Wilson Set al. Chronic kidney disease in an Aboriginal population: a nurse practitioner-led approach to management. Aust J Rural Health 2015;23:318–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akhtar T, Hipkiss V, Stoves J. Improving the quality of communication and service provision for renal patients of South Asian origin: the contribution of a cultural and health improvement officer. J Ren Care 2014;40:41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Beechem MH. Maria: developing a culturally-sensitive treatment plan in pre-hospice south Texas. Hosp J 1995;10:19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2013;1:1–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Song MK, Kirchhoff KT, Douglas Jet al. A randomized, controlled trial to improve advance care planning among patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Med Care 2005;43:1049–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Williams AF, Manias E, Walker RG. The devil is in the detail - a multifactorial intervention to reduce blood pressure in co-existing diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a single blind, randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Muncan B. Cardiovascular disease in racial/ethnic minority populations: illness burden and overview of community-based interventions. Public Health Rev 2018;39:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Joo JY, Liu MF. Experience of culturally-tailored diabetes interventions for ethnic minorities: a qualitative systematic review. Clin Nurs Res 2021;30:253–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chan DNS, So WKW. A systematic review of the factors influencing ethnic minority women's cervical cancer screening behavior: from intrapersonal to policy level. Cancer Nurs 2017;40:E1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Henderson S, Kendall E, See L. The effectiveness of culturally appropriate interventions to manage or prevent chronic disease in culturally and linguistically diverse communities: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community 2011;19:225–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haffner SM, Gruber KK, Aldrete G Jret al. Increased lipoprotein(a) concentrations in chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 1992;3:1156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bauer-Wu S, Sullivan AM, Rosenbaum Eet al. Facing the challenges of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with mindfulness meditation: a pilot study. Integr Cancer Ther 2008;7:62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]