Abstract

Nursing students are part of the future health labor force; thus, knowing their knowledge and participation in tobacco control is of importance. Multicentre cross-sectional study conducted to assess nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and training in tobacco dependence and treatment at 15 nursing schools in Catalonia. We employed a self-administered questionnaire. 4,381 students participated. Few respondents (21.1%) knew how to assess smokers’ nicotine dependence, and less than half (41.4%) knew about the smoking cessation therapies. Most (80%) had been educated on the health risks of smoking, 50% about the reasons why people smoke and, one third on how to provide cessation aid. Students in the last years of training were more likely to have received these two contents. Nursing students lack sufficient knowledge to assess and treat tobacco dependence and are rarely trained in such subjects. Nursing curricula in tobacco dependence and treatment should be strengthened to tackle the first preventable cause of disease worldwide.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking, addiction, knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, nursing, students

BACKGROUND

Tobacco use is a significant public health hazard, responsible for nearly 6 million deaths worldwide annually (WHO, 2017). Tobacco control policies have proven to be effective in reducing tobacco-attributable morbidity and mortality (Holford, Jeon, Moolgavkar, & Levy, 2014), in which treating tobacco dependence should be incorporated (Lemmens, Oenema, Knut, & Brug, 2008). While progress has been made in reducing smoking prevalence in the general population, tobacco use remains high among people with a mental disorder (Guydish et al., 2016) who smoke at rates approximately twice that of adults without mental disorders ((CDC), 2013).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called on health professionals to be role models by not using tobacco products and promoting a tobacco-free culture (Iniciative, 2005). Nurses, as the largest group in the health care workforce, are well-placed to promote health in a variety of settings that offer opportunities to provide tobacco control interventions (Duaso, Bakhshi, Mujika, Purssell, & While, 2017; L. Sarna et al., 2009). However, despite the historical roots of nursing in public health and health promotion (Barker & Buchanan-Barker, 2011; Mcallister, 2010), nurses’ contribution to tobacco control is insufficient (Duaso et al., 2017; L. Sarna & Bialous, 2005) and rates of helping smokers to quit suboptimal (Rice, Heath, Livingstone-Banks, & Hartmann-Boyce, 2017) even in psychiatric settings (Alexandra P Metse, Wiggers, Wye, & Bowman, 2018) where more than half of patients smoke (Ballbe et al., 2016; A P Metse et al., 2017).

Reasons for nurses’ modest contribution to promoting tobacco cessation include their own tobacco use (Duaso et al., 2017), lack of time in promoting healthy behaviors, and lack of training in how to support smokers to quit (Katz et al., 2016; Ratschen, Britton, Doody, Leonardi-Bee, & McNeill, 2009). International studies have shown that nurses receive little training in practical delivery of smoking cessation interventions (L. Sarna, Bialous, Ong, Wells, & Kotlerman, 2012; Warren, Jones, Chauvin, Peruga, & Group, 2008), which is one of the main factors that prevents nurses from intervening with patients who smoke (Sreeramareddy, Ramakrishnareddy, Rahman, & Mir, 2018).

To deliver smoking cessation interventions effectively, nurses should be trained during their professional education (L. Sarna, Bialous, Barbeau, & McLellan, 2006; L. P. Sarna et al., 2014). Studies in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (USA) have explored how training on tobacco use, dependence, and treatment is provided in the nursing curricula (B. Richards et al., 2014; Warren, Sinha, Lee, Lea, & Jones, 2009) and highlight knowledge gaps in practical contents required to deliver smoking cessation services (Rigotti et al., 2009).

In Spain, 29% of adults (> 15 years old) are smokers (Commission, 2015), and the prevalence of tobacco use among nurses (Duaso et al., 2017; C Martinez et al., 2016) and nursing students (Fernandez, Martin, Molina, & De Luis, 2010; Ordas et al., 2015) is similar to that in the general population of their same age and sex (25.4% among nurses and 18.2 to 28.8% among nursing students). However, little is known about nursing students’ attitudes toward their own role in tobacco control, their knowledge in a range of tobacco-related topics, and what training is received on this topic during their nursing education has received scant attention in Spain. Therefore, it is important to examine whether nursing students are receiving and acquiring adequate knowledge and skills to deliver tobacco cessation interventions in a country in which still one in four adults smoke.

The aim of this study was to examine Spanish nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and training in tobacco-related issues, including dependence and treatment, during their undergraduate education.

METHOD

Design and participants

The tobacco-related consumption, knowledge, and education among nursing students’ study” (ECTEC) is a large cross-sectional multicentre study conducted in fifteen University Nursing Schools in Catalonia (Spain). The study was designed with the purpose of responding to several research aims, including the characterization of tobacco, e-cigarettes, and cannabis use published before (Martinez et al., 2019). In brief, the participants of the ECTEC Study were first to fourth-year nursing students enrolled in a nursing school in Catalonia from October 2015 to June 2016 (2015–2016 academic year). Overall, 7,660 nursing students were enrolled during that time period (aggregated data provided by each university). Inclusion criteria were: (1) to be ≥ 18 years old, (2) to be registered in the core subject class in which the study data were collected, (3) to attend this class the day of the data collection, and (4) to provide written informed consent to participate in the study.

Instrument and Variables

As part of the large ECTEC study, an anonymous self-administered paper version questionnaire was designed based on the Global Health Professional Survey (GHPS) to explore knowledge, attitudes and training in tobacco-related issues (Warren et al., 2011). The questionnaire (available upon request) included 62 questions and was piloted in one of the universities to test its reliability and acceptability (Martinez et al., 2017).

For this study, the main dependent variables were tobacco-related knowledge, attitudes, and training received in nursing school.

Knowledge about tobacco-related issues referred to epidemiological data (e.g., prevalence of tobacco consumption, mortality and morbidity worldwide and in Spain), health effects, and tobacco dependence and treatment. Statements were formulated to assess student knowledge in these areas, with response codes of “true” or “false”.

Attitudes towards smoking included student’s opinion on whether nurses and nursing students should be role models and not smoke, whether health professionals should be trained to ask and record smoking status, advice smokers to quit, and help patients quit. A 5-points Likert scale (“totally agree”, “agree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “disagree”, “totally disagree”) was used to collect this information. For this study, the first two responses were combined into “agree,” and the remaining were combined as “disagree.”

Regarding training, participants were asked if they had received education and/or training in various tobacco-related areas such as epidemiological data, health effects, morbidity, and, tobacco dependence and treatment interventions. The possible response options were: “yes”, “no”, “do not know / do not answer”. We combined “no” and “do not know / do not answer” to mean “no” for this study.

The main independent variables explored were sex, year of school (first, second, third, fourth), and smoking status. Respondents were classified as current smokers (smokes either daily/every day or occasionally/not every day), former smokers (used to smoke but abstinent for six months or longer) and never smokers (never smoked ≥100 cigarettes in their life (Husten, 2009).

Procedure

We contacted the Deans of each Nursing School to request permission to conduct the survey, and the appointment of a contact person to act as a liaison in each center. All fifteen schools agreed to participate. The fieldwork consisted of several visits to each of the centers to reach all the courses.

In each of the selected classrooms, all students were orally informed about the main objectives of the study by one of the researchers, and a participant information sheet was provided. All participants gave written informed consent before completing the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, average time to complete the survey was 15 minutes, and no incentives were provided to respondents.

Data analysis

For the extraction of data, all the paper-based questionnaires were digitized and processed with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and Intelligent Character Recognition (ICR) Kofax© technology. We computed frequencies and percentages for all the dependent variables. For this study, we grouped year of education in two categories 1st and 2nd year students and 3rd and 4th. To test differences in independent variables (sex, year of education, and smoking status) we used Chi-square tests. In addition, we performed adjusted multilevel logistic regression analysis, with fixed effects, for each dependent variable to provide adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and their 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) with the nursing school as the 2nd level of aggregation. Statistical significance was established at p≤ 0.01. The analyses were performed using SPSS© 21.0 for Windows©.

RESULTS

Participation and demographic data of the participants

The final sample was composed of 4,381 students, that represent the 57.2% of students enrolled in the academic year 2015–2016 (4,381/7,660). Nevertheless, the 98.5% (4,381/4,447) of students who were at class at the time of the survey agreed to participate. With regard to participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, 83.9% were women, 58.2% were in their 1st or 2nd year of school, 29.7% were smokers, 57.2% never smokers and, 13.1% former smokers.

Participants’ knowledge in tobacco-related topics

Most participants (98%) responded that tobacco use is an addiction and 98.3% responded that secondhand smoke is a health hazard for non-smokers. However, only 35.8% knew that tobacco consumption rates were decreasing in Spain at the time of the study. Students in the 3rd or 4th years of training knew more of this epidemiologic trend than those in 1st or 2nd year (Figure 1). About 77.5% knew that tobacco-related mortality is decreasing in Spain and 66.4% knew that cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of tobacco-related morbidity. In both cases, students from the last years of nursing education knew more of these trends than those in the first years (Table 1). Only 21.1% of participants knew that the Fageström test is not used to assess smokers’ motivation to quit and 41.4% affirmed that hypnosis is not an effective quitting method; students from the last years of schooling (3rd and 4th) were more likely to know these concepts (aOR=1.18; 95%CI= 1.04–1.33) than first year students (Figure 1). In addition, 59.4% of participants knew that nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is not recommended to smokers who smoke less than five cigarettes per day, with students from the last education years having greater odds of knowing this than those in the first years group (aOR= 1.63; 95%CI= 1.43–1.85).

Figure 1. Sociodemographic factors associated with knowledge acquired about several tobacco-related issues (aOR and 95% CI).

Note: Multi-level models are adjusted by gender, year of school and smoking status

References categories (Women- Ref= Men); (3+4 years – Ref= 1+2 years); (Former Smoker- Ref= Smoker); (Never Smoker- Ref= Smoker)

Table 1.

Knowledge acquired about tobacco-related content (epidemiology, cessation, etc) by gender, school years and smoking status

| Overall | Gender |

School years |

Smoking status |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | 1+2 | 3+4 | Smoker | Former | Never | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Statements | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Tobacco use is an addiction | 4.252 | 98.0 | 691 | 98.0 | 3,594 | 98.0 | 2,406 | 97.8 | 1,732 | 98.3 | 1,255 | 97.4 | 551 | 97.2 | 2,446 | 98.5 |

| The prevalence of tobacco use is decreasing in the last years in Spain | 1,552 | 35.8 | 277 | 39.3 | 1,286 | 35.1 | 833 | 33.9 | 688 | 39.0 | 469 | 36.4 | 226 | 39.9 | 857 | 34.5 |

| Tobacco-related mortality is decreasing in the last years in Spain | 3,361 | 77.5 | 524 | 74.3 | 2,865 | 78.1 | 1,858 | 75.5 | 1,413 | 80.2 | 973 | 75.5 | 447 | 78.8 | 1,941 | 78.1 |

| Cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of tobacco-related morbidity in Spain | 2,883 | 66.4 | 487 | 69.1 | 2,417 | 65.9 | 1,514 | 61.5 | 1,290 | 73.2 | 931 | 72.3 | 413 | 72.8 | 1,539 | 62.0 |

| Secondhand smoke is a hazard for non-smokers | 4,267 | 98.3 | 687 | 97.4 | 3,614 | 98.5 | 2,419 | 98.3 | 1,735 | 98.5 | 1,262 | 98.0 | 556 | 98.1 | 2,449 | 98.6 |

| Among pregnant women who smoke, it should be recommended to smoke a maximum of five cigarettes per day when they have anxiety | 2,883 | 66.4 | 507 | 71.9 | 2,394 | 65.3 | 1,667 | 67.8 | 1,136 | 64.5 | 753 | 58.5 | 347 | 61.2 | 1,783 | 71.8 |

| Fageström test does not assess smokers’ motivation to quit | 917 | 21.1 | 155 | 22.0 | 766 | 20.9 | 547 | 22.2 | 346 | 19.6 | 272 | 21.1 | 124 | 21.9 | 521 | 21.0 |

| Hypnosis has not been proved to be effective quit smoking | 1,796 | 41.4 | 302 | 42.8 | 1,509 | 41.1 | 985 | 40.0 | 770 | 43.7 | 506 | 39.3 | 218 | 38.4 | 1,072 | 43.2 |

| Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of sudden infant death | 3,739 | 86.2 | 593 | 84.1 | 3,177 | 86.6 | 2,077 | 84.4 | 1,574 | 89.3 | 1,091 | 84.7 | 482 | 85.0 | 2,166 | 87.2 |

| Passive smoking causes lung cancer in non-smokers | 3,284 | 75.7 | 577 | 81.8 | 2,729 | 74.4 | 1,778 | 72.3 | 1,411 | 80.1 | 972 | 75.5 | 448 | 79.0 | 1,864 | 75.0 |

| Guidelines do not recommend NRT to smokers of less than five cigarettes a day | 2,577 | 59.4 | 389 | 55.2 | 2,200 | 60.0 | 1,349 | 54.8 | 1,163 | 66.0 | 740 | 57.5 | 337 | 59.4 | 1,500 | 60.4 |

All the statements of this table are true, and frequencies and percentages correspond to participants who answered correctly to the true/false questions

NRT= Nicotine Replacement Therapy

Participants’ attitudes towards tobacco control

While 63.1% of participants considered that health professionals should lead by the example and not smoke, only 45.1% thought that nursing students should have the same exemplary role. In both cases, never and former smokers were more likely to express higher support for these two statements than smokers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants’ attitudes towards health professionals’ and health organizations’ role in tobacco control by gender, school years and smoking status

| Overall | Gender |

School years |

Smoking status |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | 1+2 | 3+4 | Smoker | Former | Never | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Attitudes | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Health professionals should be an example and not smoke | 2,727 | 63.1 | 432 | 61.9 | 2,321 | 63.4 | 1.576 | 64.3 | 1.089 | 61.9 | 585 | 45.7 | 364 | 64.2 | 1.778 | 71.7 |

| Nursing students should be an example and not smoke | 1,951 | 45.1 | 307 | 44.0 | 1,661 | 45.4 | 1,102 | 45.0 | 811 | 46.2 | 365 | 28.4 | 272 | 48.0 | 1,314 | 53.2 |

| Health professionals should be trained to help patients quit smoking | 4,121 | 95.9 | 652 | 93.5 | 3,497 | 96.2 | 2,316 | 95.1 | 1,692 | 96.7 | 1,193 | 93.7 | 539 | 95.4 | 2,389 | 97.1 |

| Health professionals should routinely ask and record tobacco use of their patients in the medical record | 3,608 | 83.5 | 572 | 82.2 | 3,062 | 83.7 | 1,995 | 81.4 | 1,519 | 86.7 | 1,004 | 78.4 | 483 | 85.3 | 2,121 | 85.8 |

| Health professionals should routinely advice their smoker patients to quit smoking | 3,458 | 80.3 | 549 | 78.7 | 2,939 | 80.6 | 1,957 | 80.0 | 1,406 | 80.3 | 971 | 75.9 | 468 | 83.0 | 2,019 | 81.9 |

| The possibilities that a smoker quits increase when advised by a health professional | 2,427 | 56.3 | 442 | 63.5 | 2,001 | 54.8 | 1,294 | 52.9 | 1,056 | 60.3 | 704 | 55.2 | 326 | 57.7 | 1,397 | 56.5 |

| A health professional who smoke is less likely to advise their patients to quit | 1,313 | 30.4 | 224 | 32.1 | 1,096 | 30.0 | 721 | 29.5 | 549 | 31.3 | 314 | 24.6 | 172 | 30.6 | 827 | 33.4 |

| The National Health System should fund effective treatments to quit smoking | 2,996 | 69.4 | 476 | 68.4 | 2,545 | 69.7 | 1,682 | 68.8 | 1,241 | 70.8 | 953 | 74.6 | 392 | 69.6 | 1,651 | 66.7 |

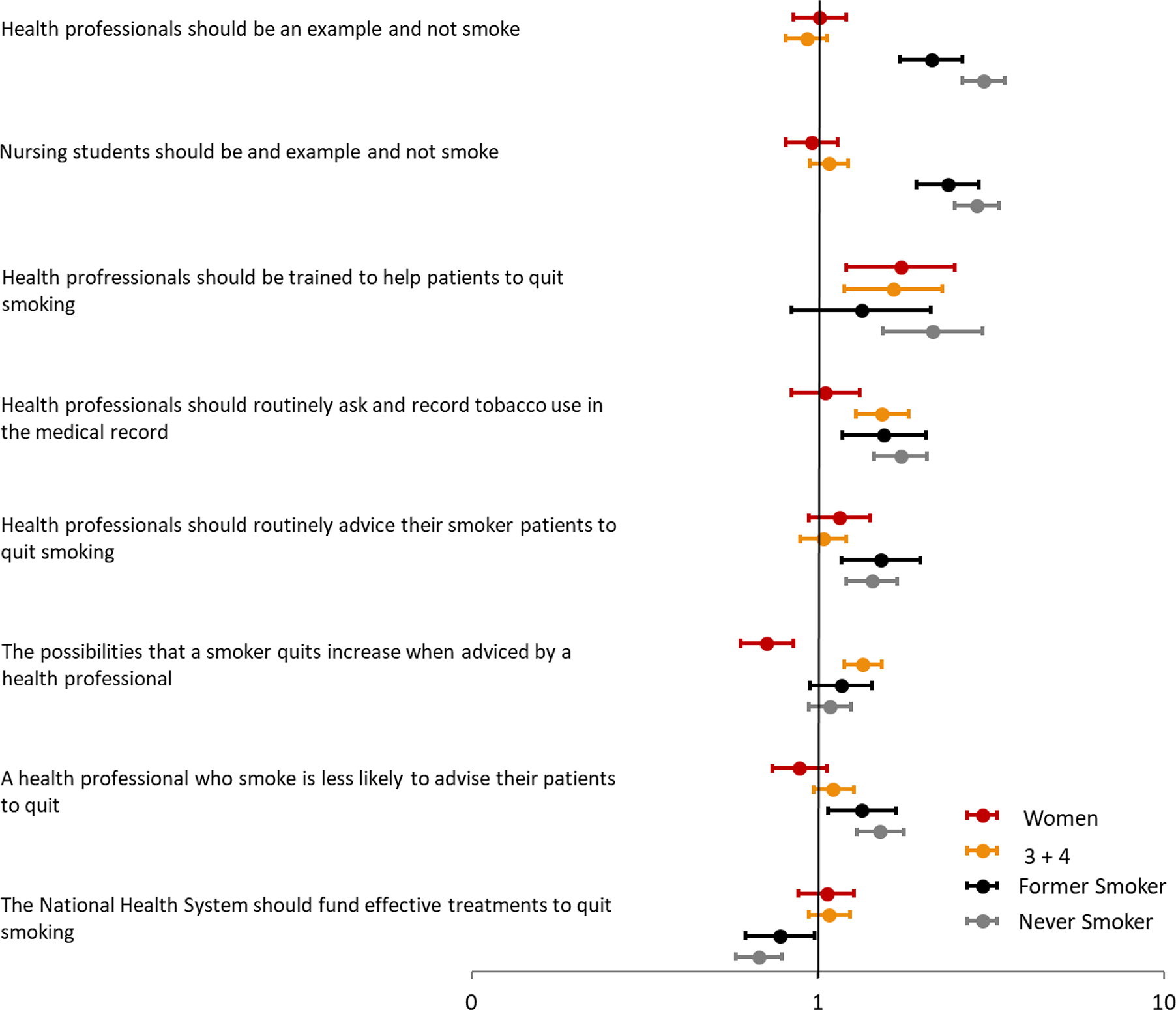

The majority of students (95.9%) believed that health professionals should be trained to help smokers quit, but women (aOR=1.74; 95%CI= 1.21–2.49) and those in the last years of education (aOR=1.65; 95%CI= 1.19–2.29) and never smokers were more likely to have this opinion (aOR=2.14; 95%CI= 1.54–2.99)., Only 56.3% believed that smokers are more likely to quit when advised by a health professional. 30.4% of participants thought that health professionals who smoke are less likely to advise their patients to quit, and compared to smokers, never smokers (aOR=1.51; 95%CI= 1.30–1.77) and former smokers (aOR=1.34; 95%CI= 1.07–1.68) were more likely to have this opinion (Figure 2). Finally, 69.4% of participants considered that the National Health System should fund effective treatments to quit smoking, with a lower support among former (aOR=0.78; 95%CI= 0.62–0.98) and never smokers (aOR=0.68; 95%CI= 0.58–0.79) compared to smokers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sociodemographic factors associated with participants’ attitudes towards health professionals’ and health organizations’ role in tobacco control (aOR and 95% CI).

Note: Multi-level models are adjusted by gender, year of school and smoking status

References categories (Women- Ref= Men); (3+4 years – Ref= 1+2 years); (Former Smoker- Ref= Smoker); (Never Smoker- Ref= Smoker)

Tobacco-related training received during nursing education

Most participants (86.9%) stated that they had been taught about the risks of smoking and the difference between active and passive smoking during their nursing education students from the last years of schooling (3rd and 4th) being more likely to have received this information (aOR=5.60; 95%CI= 4.33–7.23) than first year students (Figure 3).. However, less than half reported being informed about the reasons why people smoke; students from the last years had higher odds of having received this information (aOR= 3.89; 95%CI= 3.41–4.43). In addition, only 33.4% received training on how to help smokers quit, with the students from the last years having higher odds (aOR=7.86; 95%CI= 6.79–9.11) of receiving this training compared to those of the first years. In terms of how to support smokers quit, 60.5% were taught about the importance of giving educational materials, 65.3% about how to use NRT, and 30.9% about the use of other pharmacotherapies. This knowledge was higher among 3rd and 4th year students (see Table 3). Nevertheless, only 24.3% of participants affirmed to have the knowledge and skills required to help smokers quit. Students from the last years (3rd and 4th school years) were more likely (40.1%) to consider themselves capable of helping smokers to quit than students in the first years (1st and 2nd school years, 12.6%) (OR= 4.69; 95%CI= 4.02–5.48) (Figure 3). Generally, students from the last years of schooling reported having received more information about smoking consumption and smoking cessation content, this variable being the most significant predictor (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sociodemographic factors associated self-reported training received on tobacco-related contents during their Nursing Bachelor’s degree Program (aOR and 95% CI).

Note: Multi-level models are adjusted by gender, year of school and smoking status

References categories (Women- Ref= Men); (3+4 years – Ref= 1+2 years); (Former Smoker- Ref= Smoker); (Never Smoker- Ref= Smoker)

Table 3.

Participants’ self-reported training received on tobacco-related contents during their Nursing Bachelor Degree Program by gender, school years and smoking status

| Overall | Gender |

School years |

Smoking status |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | 1+2 | 3+4 | Smoker | Former | Never | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Training received | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Has somebody informed you about the risks of smoking in class, during a seminar or practicum session/class? | 3,563 | 82.5 | 586 | 83.5 | 3,007 | 82.4 | 1,800 | 73.6 | 1,665 | 94.8 | 1,040 | 81.4 | 472 | 84.0 | 2,051 | 82.8 |

|

Does somebody has explained you the difference between an active smoker and a passive smoker in class? |

3,762 | 86.9 | 622 | 88.4 | 3,173 | 86.7 | 1,979 | 80.6 | 1,684 | 95.8 | 1,134 | 88.5 | 492 | 87.1 | 2,136 | 86.1 |

|

Have you discussed the reasons why people smoke? |

2,114 | 49.1 | 375 | 53.6 | 1,756 | 48.2 | 867 | 35.5 | 1,185 | 67.7 | 600 | 46.9 | 283 | 50.8 | 1,231 | 49.8 |

|

Have you been taught about the importance of asking and recording tobacco use in the health record? |

2,821 | 65.3 | 434 | 61.8 | 2,405 | 65.9 | 1,286 | 52.6 | 1,452 | 82.7 | 821 | 64.1 | 390 | 69.1 | 1,610 | 65.1 |

|

Have you been trained on how to help smokers to quit? |

1,440 | 33.4 | 237 | 33.8 | 1,217 | 33.3 | 373 | 15.2 | 1,022 | 58.3 | 426 | 33.3 | 201 | 35.7 | 813 | 32.9 |

|

Have you been recommended to provide educational material to smokers in order to advise them about the benefits of quitting? |

2,605 | 60.5 | 415 | 59.3 | 2,217 | 60.9 | 1,121 | 45.9 | 1,416 | 80.8 | 761 | 59.6 | 346 | 61.3 | 1,498 | 60.7 |

|

Have you been taught on how to use NRT for helping smokers to quit? |

2,808 | 65.3 | 468 | 66.9 | 2,363 | 65.0 | 1,377 | 56.4 | 1,358 | 77.7 | 831 | 65.3 | 400 | 71.0 | 1,577 | 63.9 |

|

Have you been taught on to use pharmacological treatments to quit smoking besides NRT? |

1,322 | 30.9 | 235 | 33.8 | 1,099 | 30.4 | 609 | 25.0 | 668 | 38.6 | 463 | 36.4 | 181 | 32.6 | 678 | 27.6 |

| At present I have knowledge and enough skills to help a smoker to quit | 1,044 | 24.3 | 221 | 31.9 | 832 | 22.9 | 306 | 12.6 | 698 | 40.1 | 329 | 25.9 | 168 | 30.2 | 547 | 22.2 |

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study that comprehensively explores knowledge and attitudes towards tobacco in a high number of nursing schools in Spain (all nursing schools in Catalonia). A high percentage of nursing students knew about the risks of smoking; but did not know about the current trends in the tobacco epidemic nor have the necessary knowledge for assessing and treating tobacco dependence. Nursing students generally reported having been informed about the risks of smoking, but only one in three reported having been trained on how to help patients quit. These findings point out how tobacco-related competencies are scarcely taught and evaluated in nursing programs in Catalonia.

Our findings indicate that nursing students have a low attitude towards the role of nurses in tobacco control, especially if they are smokers. In this study, participants’ support towards this role of nurses and nursing students was lower than that reported by other studies (Chandrakumar & Adams, 2015; Sreeramareddy et al., 2018; Vitzthum et al., 2013). This difference may derive from the inclusion of all University Nursing Schools in Catalonia, yielding a more realistic picture of the situation than studies conducted in only one center. Nurses’ personal attitudes towards tobacco use influence their practices in advising and counselling smokers to quit (Duaso et al., 2017). It is known that college years are a critical time for developing tobacco use and building attitudes towards tobacco (Ye et al., 2017). Thus, encouraging college students to quit during their university education (Pardavila-Belio et al., 2015) is essential, especially if they are pursuing a health professional degree (Tavolacci, Delay, Grigioni, Déchelotte, & Ladner, 2018), as this may influence their future practice. Some undergraduate students start tobacco use and become nicotine-dependent during their college years (Freedman, Nelson, & Feldman, 2012). It is critical to offer college students the opportunity to quit, especially among nursing students who are at higher risk of becoming smokers when compared to students from other healthcare professions (Tavolacci et al., 2018). Prior research in Spain has shown that a nurse-led intervention addressed to college students was helpful in decreasing smoking rates (Cristina Martinez & Fernandez, 2015; Pardavila-Belio et al., 2015). Future research should be oriented to introduce smoking cessation programs among nursing students who smoke during school years.

The majority of participants knew about the harmful effects of smoking on health, which was similar to results reported by a study conducted in the UK (D. A. Richards & Borglin, 2011). However, participants were less informed about other tobacco-related contents, such as the current epidemiologic trends in tobacco use and information needed to assess and treat nicotine dependence. In this regard, although some studies have explored nursing students’ knowledge in tobacco-related content, there is no consensus about what tobacco-related competencies nurses should acquire during their nursing education (Ye et al., 2017). Ordás et al. explored nursing students’ knowledge about tobacco and exposure to secondhand smoke as a cause of disease (Ordas et al., 2015), but did not explore other contents. In our study, we have examined Spanish nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and training in several tobacco-related topics, from epidemiologic trends to evidence-based interventions; however, more research is needed to establish what concepts and skills nurses should learn during their training.

Last, our participants confirmed that they had received little training in tobacco cessation interventions. This finding aligns with those of previous studies (B. Richards et al., 2014; L. Sarna et al., 2009; Sreeramareddy et al., 2018). Our results show that students from the last years of schooling had received more training in smoking consumption and smoking cessation during their Nursing education, this variable being the most significant predictor of having received this academic content. In spite of this fact, there was a general lack of knowledge about how to assess and treat nicotine dependence. Up to now, smoking cessation is taught in broad courses such as health promotion (B. Richards et al., 2014), and nursing programs tend to focus on the health effects of smoking but neglect the practical aspects of how to assist smokers to quit (Petersen, Meyer, Sachs, Bialous, & Cataldo, 2017; Sreeramareddy et al., 2018). In addition, cessation skills are rarely tested in student examinations (Forman, Harris, Lorencatto, McEwen, & Duaso, 2017; B. Richards et al., 2014). The limited number of hours allocated to smoking cessation in nursing curricula may also reflect the low priority of this topic among nurses (Freedman et al., 2012; Ye et al., 2017). Training all healthcare workers to record smoking use and provide brief smoking cessation intervention may be an effective method to scaling up the use of smoking cessation guidelines (Carson et al., 2012) and counteract the tobacco epidemic. However, this material is usually only given in postgraduate short courses (Ye et al., 2017), ranging from 1 to 4 hours, and that cover several tobacco-related specific topics such as tobacco dependence, secondhand tobacco smoke, nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and tobacco cessation interventions (including motivational approaches, stages of change, etc.) (Ye et al., 2017). Efforts to include tobacco cessation in Nursing Schools curricula have been made in the USA (Petersen et al., 2017); however, there is not a consensus of what material should this curricula incorporate nor which competencies students should demonstrate at the end of their bachelor’s degree (Royal College of Physicians, 2018). In a study conducted in Canada, the majority of nursing teachers and professors lack specific smoking cessation training and background, and consequently their lectures include little content about this topic (Lepage, Dumas, & Saint-Pierre, 2015). In Spain, nursing curriculum guidelines state a commitment to health promotion, but there are not current guidelines on teaching smoking cessation (Ordas et al., 2015).

Strengths and Limitations

Due to the use of a cross-sectional design, we can report associations only, without the possibility of inferring causality. Nevertheless, this cross-sectional study is the baseline of a future cohort that will allow us to investigate tobacco-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among nursing students. In addition, some selection bias can be introduced due to only those students who attended the class in which we conducted the survey were invited to participate. However, participation from those that were at class accounted for 98.5% and we were able to survey 60% of all nursing students in Catalonia in 2015–2016. Moreover, this this study has other strengths, including that the questionnaire employed is based on the Global Health Professional Survey (GHPS) (Warren, Sinha, Lee, Lea, & Jones, 2011) and its big sample size, allowing the clustering and multilevel analysis models.

Conclusions

Nursing students lack sufficient knowledge about tobacco epidemic current and how to assess and treat tobacco dependence. This is mainly because they receive scarce training in these areas during their school years. In addition, nursing students show a low attitude towards their role in tobacco control, especially among smokers. These findings point out the need to strengthen tobacco-related education by incorporating more tobacco-related content in nursing curricula in an effort to boost the future contribution of nurses to tobacco control. There is a need to further investigate the most effective approaches to introducing tobacco-related content into overall education and specifically in mental health nursing education.

Implications

This study has implications for the practice of nurses in tobacco dependence and cessation treatment in all the specialties, but in particular for those who are working in mental and psychiatric settings. Besides the impending need to improve tobacco cessation training during the years of Nursing School, other practical suggestions to improve the contribution of nurses are: including smoking cessation as part of the nurse’s role; having well-established and updated smoking cessation protocols, clinical records, and pharmacological aids in place; and rewarding nurses for helping smokers to quit. This might even contribute to improving how nursing students are trained during their practicum as they would have both the supervision of lecturers and the support of experienced nurses in the clinical field.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for contributing to the study, and the Deans and faculty of the participating university schools in Catalonia to facilitate the fieldwork. We also want to thank a group of students from the International University of Catalonia - Caterina Boix, Elisabet Casellas, Montserrat Guinart, Laura Palau, Pol Roca, Mireia Sala - who contributed to conduct the field work. Finally, we want to thank Samantha Zylberman who assist us in the proof reading.

Funding Source

This study has been partially funded by the Consell de Col·legis de Infermeres i Infermers de Catalunya (grant CCIIC 2016). The Tobacco Control Unit is funded by the Government of Catalonia (Directorate of Research and Universities grant 2017SGR399). EF was supported by the Instituto Carlos III, Government of Spain, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) (INT16/00211 and INT17/00103). CM was supported by the Instituto Carlos III, Government of Spain, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) (INT17/00116) and the Catalan Government, PERIS (9015-586920/2017).

These funding sources had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Study procedures were approved by the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of ICO-IDIBELL (PR-173/16).

REFERENCES

- Ballbe M, Gual A, Nieva G, Salto E, Fernandez E, & Group T and M. H. W. (2016). Deconstructing myths, building alliances: a networking model to enhance tobacco control in hospital mental health settings. Gaceta Sanitaria, 30(5), 389–392. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.04.017 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker P, & Buchanan-Barker P (2011). Myth of mental health nursing and the challenge of recovery. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 20(5), 337–344. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson KV, Verbiest ME, Crone MR, Brinn MP, Esterman AJ, Assendelft WJ, & Smith BJ (2012). Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 5, CD000214. 10.1002/14651858.CD000214.pub2; 10.1002/14651858.CD000214.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre of Disease Control (CDC) C. for D. C. and P. (2013). Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness - United States, 2009–2011. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(5), 81–87. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23388551 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrakumar S, & Adams J (2015). Attitudes to smoking and smoking cessation among nurses. Nursing Standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987), 30(9), 36–40. 10.7748/ns.30.9.36.s44 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission E (2015). Attitudes of Europeans Towards Tobacco and Electronic Cigarettes.

- Duaso MJ, Bakhshi S, Mujika A, Purssell E, & While AE (2017). Nurses’ smoking habits and their professional smoking cessation practices. A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 67, 3–11. https://doi.org/S0020-7489(16)30202-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez D, Martin V, Molina AJ, & De Luis JM (2010). Smoking habits of students of nursing: a questionnaire survey (2004–2006). Nurse Education Today, 30(5), 480–484. 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.10.012 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman J, Harris JM, Lorencatto F, McEwen A, & Duaso MJ (2017). National Survey of Smoking and Smoking Cessation Education Within UK Midwifery School Curricula. Nicotine & Tobacco Research : Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 19(5), 591–596. 10.1093/ntr/ntw230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman KS, Nelson NM, & Feldman LL (2012). Smoking initiation among young adults in the United States and Canada, 1998–2010: a systematic review. Preventing Chronic Disease, 9(5), E05. 10.5888/pcd9.110037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Pagano A, Martinez C, Le T, Chun J, … Delucchi K (2016). An international systematic review of smoking prevalence in addiction treatment. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 111(2), 220–230. 10.1111/add.13099 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holford TR, Jeon J, Moolgavkar SH, & Levy DT (2014). Premature Deaths in the United States, 1964 – 2012. Jama, 311(2), 164–171. 10.1001/jama.2013.285112.Tobacco [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten CG (2009). How should we define light or intermittent smoking? Does it matter? Nicotine & Tobacco Research : Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 11(2), 111–121. 10.1093/ntr/ntp010 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniciative WHOTF (2005). The role of health professionals in tobacco control. (WHO, Ed.). Ginebra. Retrieved from http://www.who.int [Google Scholar]

- Katz DA, Stewart K, Paez M, Holman J, Adams SL, Vander Weg MW, … Ono S (2016). “Let Me Get You a Nicotine Patch”: Nurses’ Perceptions of Implementing Smoking Cessation Guidelines for Hospitalized Veterans. Military Medicine, 181(4), 373–382. 10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00101 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens V, Oenema A, Knut IK, & Brug J (2008). Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among adults: a systematic review of reviews. European Journal of Cancer Prevention : The Official Journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP), 17(6), 535–544. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage M, Dumas L, & Saint-Pierre C (2015). Teaching Smoking Cessation to Future Nurses: Quebec Educators’ Beliefs. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 37(3), 376–393. 10.1177/0193945913510629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C, Martinez-Sanchez JM, Anton L, Riccobene A, Fu M, Quiros N, … Network, C. G. of the H. (2016). Smoking prevalence in hospital workers: meta-analysis in 45 Catalan hospitals. Gaceta Sanitaria, 30(1), 55–58. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2015.08.006 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Cristina, & Fernandez E (2015). Commentary on Pardavila-Belio et al. (2015): Reporting on randomized control trials or giving details on how the cake was made--the list of ingredients and the implementation process. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 110(10), 1684–1685. 10.1111/add.13046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcallister M (2010). Solution focused nursing: A fitting model for mental health nurses working in a public health paradigm. Contemporary Nurse, 34(2), 149–157. 10.5172/conu.2010.34.2.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metse AP, Wiggers J, Wye P, Wolfenden L, Freund M, Clancy R, … Bowman JA (2017). Efficacy of a universal smoking cessation intervention initiated in inpatient psychiatry and continued post-discharge: A randomised controlled trial. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 51(4), 366–381. 10.1177/0004867417692424 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metse Alexandra P, Wiggers J, Wye P, & Bowman JA (2018). Patient receipt of smoking cessation care in four Australian acute psychiatric facilities. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(5), 1556–1563. 10.1111/inm.12459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordas B, Fernandez D, Ordonez C, Marques-Sanchez P, Alvarez MJ, Martinez S, & Pinto A (2015). Changes in use, knowledge, beliefs and attitudes relating to tobacco among nursing and physiotherapy students: a 10-year analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(10), 2326–2337. 10.1111/jan.12703 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardavila-Belio MI, García-Vivar C, Pimenta AM, Canga-Armayor A, Pueyo-Garrigues S, & Canga-Armayor N (2015). Intervention study for smoking cessation in Spanish college students: pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 110(10), 1676–1683. 10.1111/add.13009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AB, Meyer B, Sachs BL, Bialous SA, & Cataldo JK (2017). Preparing nurses to intervene in the tobacco epidemic: Developing a model for faculty development and curriculum redesign. Nurse Education in Practice, 25, 29–35. 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratschen E, Britton J, Doody GA, Leonardi-Bee J, & McNeill A (2009). Tobacco dependence, treatment and smoke-free policies: a survey of mental health professionals’ knowledge and attitudes. General Hospital Psychiatry, 31(6), 576–582. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.08.003 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice VH, Heath L, Livingstone-Banks J, & Hartmann-Boyce J (2017). Nursing interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10.1002/14651858.CD001188.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards B, McNeill A, Croghan E, Percival J, Ritchie D, & McEwen A (2014). Smoking cessation education and training in UK nursing schools: A national survey. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 4(8), 188–198. 10.5430/jnep.v4n8p188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards DA, & Borglin G (2011). Complex interventions and nursing: looking through a new lens at nursing research. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(5), 531–533. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.013 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Bitton A, Richards AE, Reyen M, Wassum K, & Raw M (2009). An international survey of training programs for treating tobacco dependence. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 104(2), 288–296. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02442.x; 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02442.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians. (2018). Hiding in plain sight: Treating tobacco dependency in the NHS.

- Sarna L, & Bialous S (2005). Tobacco control in the 21st century: a critical issue for the nursing profession. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 19(1), 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Bialous SA, Wells M, Kotlerman J, Wewers ME, & Froelicher ES (2009). Frequency of nurses’ smoking cessation interventions: report from a national survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(14), 2066–2077. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Bialous S, Barbeau E, & McLellan D (2006). Strategies to implement tobacco control policy and advocacy initiatives. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 18(1), 113–122, xiii. 10.1016/j.ccell.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Bialous S, Ong M, Wells M, & Kotlerman J (2012). Nurses’ treatment of tobacco dependence in hospitalized smokers in three states. Research in Nursing & Health, 35(3), 250–264. 10.1002/nur.21476 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna LP, Bialous SA, Kralikova E, Kmetova A, Felbrova V, Kulovana S, … Brook JK (2014). Impact of a smoking cessation educational program on nurses’ interventions. Journal of Nursing Scholarship : An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing / Sigma Theta Tau, 46(5), 314–321. 10.1111/jnu.12086 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramareddy CT, Ramakrishnareddy N, Rahman M, & Mir IA (2018). Prevalence of tobacco use and perceptions of student health professionals about cessation training: Results from Global Health Professions Students Survey. BMJ Open, 8(5). 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavolacci MP, Delay J, Grigioni S, Déchelotte P, & Ladner J (2018). Changes and specificities in health behaviors among healthcare students over an 8-year period. PLoS ONE, 13(3), 1–18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitzthum K, Koch F, Groneberg DA, Kusma B, Mache S, Marx P, … Pankow W (2013). Smoking behaviour and attitudes among German nursing students. Nurse Education in Practice, 13(5), 407–412. 10.1016/j.nepr.2012.12.002 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CW, Jones NR, Chauvin J, Peruga A, & Group GC (2008). Tobacco use and cessation counselling: cross-country. Data from the Global Health Professions Student Survey (GHPSS), 2005–7. Tobacco Control, 17(4), 238–247. 10.1136/tc.2007.023895 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CW, Sinha DN, Lee J, Lea V, & Jones NR (2009). Tobacco use, exposure to secondhand smoke, and training on cessation counseling among nursing students: cross-country data from the Global Health Professions Student Survey (GHPSS), 2005–2009. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(10), 2534–2549. 10.3390/ijerph6102534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CW, Sinha DN, Lee J, Lea V, & Jones NR (2011). Tobacco use, exposure to secondhand smoke, and cessation counseling among medical students: cross-country data from the Global Health Professions Student Survey (GHPSS), 2005–2008. BMC Public Health, 11, 72. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-72 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017). Monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies. World Health Organization. https://doi.org/Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Goldie C, Sharma T, John S, Bamford M, Smith PM, … Schultz AS (2017). Tobacco-nicotine education and training for health-care professional students and practitioners: a systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research : Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 10.1093/ntr/ntx072 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]