Abstract

This study examined the relationships between body image, personality, sex, body mass index, use of social networks, and income in undergraduate students. An online data collection was carried out with 398 students who answered a data questionnaire, the Situational Body Satisfaction Scale, and the Big Five Inventory-2. Correlational analyses indicated that Neuroticism was the most associated factor with body dissatisfaction. For the other personality factors, there were associations with body image and most of the dimensions of the Situational Scale, except for Agreeableness, which showed no relationship with body image. There were positive relationships between body image and lower body mass index, higher income, and lower use of social networks. In the network model, there were differences in the degree of association between the variables for men and women. The study points out clinically important variables for interventions with young people with body image distortion.

Keywords: Body dissatisfaction, Personality, Young adult, Assessment

Introduction

Body image (BI) is defined by the way each person processes and interprets sensory information about his or her own body in relation to its shape and the level of satisfaction with the represented image (Rodgers et al., 2020). This process of perception can lead to dissatisfaction with BI, referred to as the discrepancy between the actual representation of the body itself and its idealized form (Silva et al., 2019). BI is generally assessed in two ways: the level of general dissatisfaction with the body as a whole and dissatisfaction with its specific parts. However, as satisfaction with specific parts of the body may vary, it is recommended that studies on the subject include multidimensional instruments that capture different levels of satisfaction with BI (Thompson et al., 2018).

Dissatisfaction with BI can be considered a universal phenomenon, identified in both women and men with different sociodemographic and cultural characteristics (Rodgers et al., 2019). However, studies show higher levels of dissatisfaction with BI in women than in men (Alves et al., 2017; Medeiros et al., 2018; Petry & Pereira Júnior, 2019). Such studies indicate the need to consider differences between sexes in studies on BI.

BI has also been studied in relation to various clinical, social, and health outcomes (see, for example, Couto & Vasconcelos, 2020; Embacher et al., 2018; MacNeill et al., 2017; Tregunna & Wood, 2020; Zaccagni et al., 2020). Regarding socioeconomic variables, the relationships between BI and socioeconomic status are complex, and the results are not conclusive. Some studies identify higher income as associated with body dissatisfaction (Barreto et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2005), and others do not find an association when other factors are controlled (Cok, 1990; Quick et al., 2013).

One of the factors that considerably affects BI is body mass index (BMI). There is evidence of greater body dissatisfaction for overweight and obese individuals (Oliveira et al., 2020). Research also points out that body satisfaction can be influenced by the use of social networks. Studies in the area have been consistent in identifying a relationship between greater use of social networks and body dissatisfaction (Engeln et al., 2020; Rodgers et al., 2019, 2020). Possibly, content broadcast in these media encourages the comparison between BI and social expectations, especially in younger people. In addition, there is an association between a greater number of hours of media use and body dissatisfaction, which seems to affect both sexes (Santos & Gonçalves, 2020).

In the field of psychology, studies relating BI and personality have increased in recent years. Personality can be defined as a set of stable patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Zeigler -Hill & Shackelford, 2018). The internationally known Big Five Model of Personality (McCrae & Costa, 2008) has been the perspective most used in studies because it describes personality traits and factors, mainly from a psychometric point of view, and because of its universality and applicability in different linguistic and sociocultural contexts (Dong & Dumas, 2020; Soto & John, 2016). The Big Five Model assumes that personality has five distinct and independent dimensions: Neuroticism, Extroversion, Agreeableness, Openness, and Conscientiousness (McCrae & Costa, 2008). This model presents associations with different human experiences throughout the life cycle, including the perception of one’s own body, in addition to enabling evaluation at different stages of life and with specific audiences (Davis et al., 2020).

The systematic reviews by Allen and Robson (2020) and by Allen and Walter (2016) aimed to verify the relationship between personality factors and BI. Among the main relationships found, the high expression of Neuroticism showed a consistent association with negative BI, and the factors Conscientiousness and Extroversion showed a tendency towards a positive association with satisfaction with BI. However, there is greater divergence in the studies found in relation to the factors of Openness and Agreeableness and BI. In addition, the study samples had very diverse characteristics, and the relationships between personality facets and BI were not investigated (Allen et al., 2020).

In view of the above, the main objective of this study was to verify associations between satisfaction with BI and personality factors and facets in university students, both in a correlational way and through analysis by complex systems, using networks. Associations of BI with sex, BMI, income, and use of social networks were also verified. Finally, an objective was to verify a pattern of relationships between the variables associated with BI stratified by sex, from the perspective of networks.

Method

Research Design

This is a correlational study, as it assesses the relationship between body image satisfaction, personality dimensions, and other sociodemographic and habit variables. It is also a quantitative and cross-sectional study, since online data were collected in a single period (Breakwell et al., 2010).

Participants

The sample of participants in this research was non-probabilistic and accidental (Neuman, 2014), collected through the dissemination of the study on social networks. This type of sampling has less external validity because it is less representative of the population. By selecting participants who are available and thus most willing to respond, it may exclude people with different characteristics from the sample. For the present study, with an online data collection, people without internet access may be underrepresented (Neuman, 2014; Shaughnessy et al., 2012). However, given that the participants consist of college students and considering the sample size and access to participants from different regions of Brazil, it is believed that these biases are not a significant threat to the reliability of the results.

Instruments

Sociodemographic and Habits Questionnaire

The questionnaire contains sociodemographic variables and participants’ habits, such as age, sex, marital status, income, course, type of institution and region, time participants used social networks, and sought information about body care. Weight and height were collected to calculate the BMI.

Situational Scale of Body Satisfaction (ESSC) (Hirata & Pilati, 2010)

This scale assesses situational satisfaction with specific body parts. It consists of 23 items measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Exploratory factor analysis showed a structure with four factors: “lower parts” (internal consistency α = 0.72), “satisfaction with muscle” (internal consistency α = 0.82), “external parts” (internal consistency α = 0 0.65), and “satisfaction with fat” (internal consistency α = 0.82). All items had factor loadings varying between 0.32 and 0.82 with their respective dimensions. For the sample of the present study, the ESSC presented alphas equal to 0.89, 0.80, 0.69, and 0.63 for the dimensions of satisfaction with fat, muscles, lower parts, and external parts, respectively. Thus, the internal consistency indexes were satisfactory, with a borderline value for the muscles dimension and a little lower than expected for satisfaction with the external parts (considering the value of 0.70 as acceptable; Field, 2009).

Big Five Inventory-2 (Soto & John, 2017)

This instrument assesses personality factors in the Big Five Model, in addition to 15 specific facets. In this study, the version adapted for Brazil by Nelson Hauck Filho was used, with the authorization of the researcher. The version has 76 short items, with phrases describing common actions: “I am someone who …” (e.g., “is outgoing, sociable,” “tends to be quiet”). Respondents rate each item using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The study by Soto and John (2017) provided evidence of the reliability, internal structure, and validity of personality factors in the Big Five Inventory-2 (BFI-2) and facets. Internal consistency, assessed by Cronbach’s alpha, had an average of 0.86 for the factors, with a range of 0.81 to 0.90 between different samples. Alpha values for the facets ranged from 0.59 to 0.86. For the sample of the present study, the internal consistency of the major personality factors, estimated using Cronbach’s alpha, was also satisfactory: 0.93 for Neuroticism, 0.82 for Extroversion, 0.76 for Conscientiousness, 0.73 for Agreeableness, and 0.72 for Openness.

Procedures

Data Collection

Data collection took place online through the Survey Monkey platform between August 10 and December 15, 2020 (database is available from the corresponding author on request). The order of presentation of the instruments was the free and informed consent form, sociodemographic and habits questionnaire, ESSC, and BFI-2. The recruitment of university students was carried out through dissemination on social networks. Brief feedback on the results was offered and sent to the participants who requested it.

From 593 respondents, 195 participants were excluded because they had not fully completed at least one of the instruments. Comparing the participants who stayed with those who dropped out of the study, there were no significant differences between the average age (p = 0.54), nor between the proportion of female and male university students (p = 0.92).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM Statistical Software Package for Social Sciences, version 26, and JASP for IOS, version 0.14. Descriptive statistical analyses were applied to describe participant characteristics and instrument scores. The Mann–Whitney test was used to verify differences between two groups, and the non-normality of the data for all dimensions of the ESSC was verified by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (Field, 2009). The effect size of means with significant differences was calculated online (https://www.uccs.edu/lbecker/), using Pearson’s coefficient (r), considering for interpretation < 0.3 as a small effect size, 0.3 to ≤ 0.5 moderate, and > 0.5 large (Rice & Harris, 2005). Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used for correlational analyses.

The network analysis technique (Hevey, 2018) was used to investigate the relationships between body satisfaction, in its different dimensions, and the factors of personality, income, BMI, and use of social networks during the week and on weekends. The sample was divided by sex to plot the networks. The Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) was used to select the lambda of the regularization parameter of the networks. The EBIC uses a hyperparameter (y) to select sparse models (Chen & Chen, 2008). The results were interpreted according to the indicators of centrality of the variables in the networks, as follows: betweenness (those that most concentrate associations), closeness (those that have less distance from the other variables), strength (those that present the strongest correlations in the system), and expected influence (those with the greatest power to affect network relationships as a whole when they change) (Hevey, 2018).

Ethical Considerations

The project was submitted to and approved by the Ethics Committee in Research Involving Human Beings (CEPES - Federal University of São João del-Rei), under protocol number 4.137.502 (CAAE 31633720.9.0000.5151). Additionally, all participants willingly provided their free and informed consent.

Results

A total of 398 university students aged between 18 and 55 years old participated (M = 23.3; SD = 5.1); 74.4% declared themselves to be female (see Table 1). The women had a mean age of 23.4 years (SD = 5.7). Men had a mean age of 22.9 years (SD = 3.0). The BMI was classified as adequate/normal for 60.6% of the university students in the sample. Most participants lived in the southeastern region of the country, and 85.2% were single. Most had a family income between one and four minimum wages (60.4%), attended public educational institutions (73.1%), and studied psychology (32.4%) or engineering (35.6%). Most (57.5%) reported seeking information about body care. The average daily hours of use of social networks during the week was 5.18 (SD = 1.53) and on weekends 5.22 (SD = 1.61).

Table 1.

Characterization of the sample of participants

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Biological sex | ||

| Male | 102 | 25.6% |

| Female | 296 | 74.4% |

| Country region | ||

| North | 3 | 0.8% |

| North East | 5 | 1.3% |

| Midwest | 10 | 2.5% |

| Southeast | 339 | 85.2% |

| South | 41 | 10.3% |

| Course1 | ||

| Psychology | 129 | 32.4% |

| Engineering | 64 | 16.1% |

| Medicine | 48 | 12.1% |

| Law | 11 | 2.8% |

| Music | 10 | 2.5% |

| Veterinary medicine | 10 | 2.5% |

| Other | 126 | 31.6% |

| Type of institution | ||

| Public | 291 | 73.1% |

| Private | 107 | 26.9% |

| Family income | ||

| Less than 1 salary | 28 | 7.1% |

| Between 1 and 2 salaries | 90 | 22.6% |

| Between 2 and 3 salaries | 64 | 16.1% |

| Between 3 and 4 salaries | 58 | 14.6% |

| Between 4 and 5 salaries | 36 | 9.0% |

| Between 5 and 7 salaries | 36 | 9.0% |

| Between 7 and 10 salaries | 37 | 9.3% |

| Between 10 and 15 salaries | 24 | 6.0% |

| Above 15 salaries | 25 | 6.3% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 17 | 4.3% |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.3% |

| Separated | 1 | 0.3% |

| Stable or civil union | 9 | 2.3% |

| Single, living with partner | 25 | 6.3% |

| Single, never married | 345 | 86.7% |

| BMI classification | ||

| Underweight | 27 | 6.8% |

| Suitable weight | 241 | 60.6% |

| Overweight | 72 | 18.1% |

| Obese | 58 | 14.6% |

| Looking for information about body care? | ||

| Yes | 222 | 57.5% |

| No | 164 | 42.5% |

| Variables | Mean | Standard deviation |

| Participants age | 23.3 | 5.1 |

| Daily social media usage hours | 5.18 | 1.53 |

| Weekend social media usage hours | 5.22 | 1.61 |

1Courses with fewer than 10 participants were included in the “other” category

Table 2 presents the results of the comparisons between the mean scores of the participants by sex regarding BMI, personality dimensions, and satisfaction with BI. According to the results, female participants scored significantly higher on the Agreeableness and Conscientiousness factors than male university students, with a small effect size. For the Neuroticism factor, female students also had significantly higher means than male students, with a moderate effect size. On the other hand, men had significantly higher means of Openness than women, also with a small effect size. There was no significant difference between the sexes in relation to BMI, the Extroversion factor, and the dimensions external parts and muscle (ESSC). These results justify the decision to plot the networks by sex in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Description and comparison of the averages of the participants by sex in relation to BMI, personality factors, and dimensions of satisfaction with the body situation

| Sex | Statistical test and effect size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||||||

| M(DP) | MR | M(DP) | AR | u | P | r | |

| BMI | 24.24(5.41) | 196.46 | 24.14(4.27) | 208.32 | 14,196.0 | 0.396 | – |

| Extroversion | 3.15(0.68) | 197.29 | 3.23(0.63) | 205.91 | 14,444.5 | 0.514 | – |

| Agreeableness | 3.86(0.43) | 210.10 | 3.70(0.50) | 168.75 | 18,232.5 | 0.002 | 0.2 |

| Conscientiousness | 3.55(0.58) | 213.12 | 3.32(0.55) | 159.98 | 19,127.0 | < 0.001 | 0.2 |

| Openness | 3.56(0.62) | 187.34 | 3.82(0.60) | 234.77 | 11,498.0 | < 0.001 | 0.2 |

| Neuroticism | 3.34(0.74) | 214.82 | 2.95(0.74) | 155.03 | 19,632.0 | < 0.001 | 0.3 |

| Satisfaction with fat | 2.73(0.10) | 188.24 | 3.15(0.08) | 232.17 | 11,763.5 | < 0.001 | 0.9 |

| External parts | 3.34(0.88) | 192.91 | 3.53(0.92) | 218.62 | 13,145.5 | 0.051 | - |

| Satisfaction with muscles | 2.79(0.91) | 197.64 | 2.85(0.87) | 204.91 | 14,544.5 | 0.582 | - |

| Lower parts | 3.14(0.99) | 179.63 | 3.80(0.81) | 257.18 | 9213.0 | < 0.001 | 0.3 |

M mean, SD standard deviation, AR average of ranks, U Mann–Whitney statistical test, p statistical significance, r effect size considered small for values < 0.3, moderate for the range between 0.3 and ≤ 0.5, and large for > 0.5

The analysis of the relationship between the ESSC dimensions, the personality factors and facets, and the participants’ characteristics is presented in Table 3. The results indicated a moderate negative association between the Neuroticism factor and its facets with all dimensions of satisfaction with the body situation. This indicates that the greater the expression of Neuroticism, the lower the satisfaction tends to be with the dimensions of the body. The associations of this factor and its facets presented the strongest correlations with the dimensions of the ESSC.

Table 3.

Correlational analysis between the dimensions of the ESSC and the factors and facets of personality, BMI, and characteristics of the participants

| Satisfaction with fat | External parts | Satisfaction with muscles | Lower parts |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | –0.40** | –0.31** | –0.42** | –0.39** |

| Anxiety | –0.31** | –0.23** | –0.31** | –0.29** |

| Depression | –0.41** | –0.34** | –0.46** | –0.44** |

| Emotional instability | –0.32** | –0.28** | –0.32** | –0.29** |

| Extroversion | 0.09 | 0.15** | 0.16** | 0.16** |

| Sociability | –0.01 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Assertiveness | 0.06 | 0.10* | 0.08 | 0.13* |

| Energy level | 0.21** | 0.22** | 0.29** | 0.25** |

| Conscientiousness | 0.09 | 0.15** | 0.13** | 0.14** |

| Organization | 0.05 | 0.12* | 0.07 | 0.11* |

| Productivity | 0.14* | 0.16* | 0.17* | 0.19** |

| Responsibility | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Openness | 0.12* | 0.11* | 0.09 | 0.13* |

| Aesthetic sense | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Intellectual curiosity | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Creative imagination | 0.13* | 0.16* | 0.10* | 0.18** |

| Agreeableness | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | –0.03 |

| Compassion | –0.03 | 0.004 | –0.02 | –0.09 |

| Respect | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | –0.02 |

| Confidence | 0.10* | 0.05 | 0.12* | 0.05 |

| BMI | –0.53** | 0.04 | –0.36** | –0.25** |

| Family income | 0.12* | 0.11* | 0.09 | 0.13* |

| Social media during the week | –0.19** | –0.12** | –0.23** | –0.16** |

| Social media on weekends | –0.20** | –0.15** | –0.27** | –0.21** |

BMI body mass index; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001

The second personality factor that most correlated with body satisfaction was Extroversion. The factor was positively correlated with the satisfaction dimensions of muscles, external parts, and lower parts. Higher scores in the Assertiveness facet correlated with satisfaction with external and upper parts. The facet Energy Level was positively correlated with all dimensions of body satisfaction. This facet includes items that assess energy, enthusiasm, excitement, and propensity to be active.

Conscientiousness was also positively correlated with the dimensions of satisfaction with muscles, external parts, and lower parts of the ESSC. The Organization facet was positively correlated with satisfaction with external and upper parts, and the Productivity facet was positively correlated with all dimensions of body satisfaction. The Productivity facet includes items that assess commitment to work, other people, care in doing things, and responsible behavior.

Openness was positively correlated with all ESSC dimensions, except for muscle satisfaction. The only facet of this factor that was positively correlated with body satisfaction was Creative Imagination, which was associated with all dimensions of this construct. The Creative Imagination facet includes items that assess creativity in doing things and coming up with new ideas.

Agreeableness was the only factor that did not present a significant relationship with any of the dimensions of body satisfaction. For this factor, the facet Confidence was the only one that showed positive correlations of low magnitude with the satisfaction dimensions with fat and with muscles of the ESSC. This facet assesses the individual’s propensity to forgive, overlook faults, and believe in people’s kindness and good intentions.

BMI was negatively related to all dimensions of body satisfaction, with the exception of external parts. Family income showed a low-magnitude association with all dimensions of body satisfaction, with the exception of muscle satisfaction. Finally, more time spent on social media during the week and on weekends was negatively correlated with body satisfaction in all dimensions.

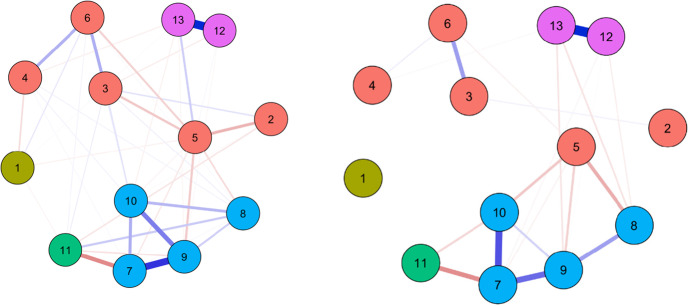

Figure 1 represents the network perspective of partial relationships between the variables of satisfaction with the body, personality, income, BMI, and use of social networks for males and females. The sparsity in the men’s network was high (0.731), and of the 78 possible relationships, 21 occurred. In the women’s network, which was visibly more connected, sparsity was lower (0.449), with 43 of the 78 possible relationships being established. Comparing the networks for the two sexes, a cluster of stronger associations is observed among Neuroticism, the dimensions of body satisfaction, and BMI for both. In addition, it is noteworthy that income had no relationship with other variables in the men’s network and practically null relationships with three personality factors and with the use of social networks for women. Thus, in a multivariate system, this variable had practically no influence.

Fig. 1.

Network of relationships for females (left) and males (right). Notes: (1) Income. Red cluster represents personality dimensions: (2) Agreeableness; (3) Conscientiousness; (4) openness; (5) Neuroticism; (6) Extroversion. Blue cluster represents dimensions of satisfaction with body image: (7) Satisfaction with body fat; (8) Satisfaction with external body parts; (9) Satisfaction with muscle; (10) Satisfaction with lower body parts. (11) Body mass index. Pink cluster represents frequency of social media use: (12) Weekday social media usage hours; (13) Weekend social media usage hours

Regarding the variables with greater betweenness, that is, those that connected to a greater number of others in the network, they included Neuroticism (1.967) and Extroversion (1.742) for men and Neuroticism (2.702), satisfaction with muscle (0.982), and Extroversion (0.767) for women. Regarding closeness, the variables that have the lowest distance from others in the network for university students are Neuroticism (2.151) and satisfaction with muscle (0.945). In the network of university students, there were no variables with greater closeness, an indicator that reinforces the high sparseness of the network. The variables with the highest strength scores, that is, which established the strongest associations in men’s social networks, were satisfaction with fat (1.794), satisfaction with muscle (1.136), satisfaction with the lower body (0.806), and use of social networks during the week (0.804). For women, stronger associations occurred for the variables of satisfaction with muscle (1.679), satisfaction with fat (1.332), satisfaction with lower parts (0.740), and Neuroticism (0.739). Finally, in the male university students’ network, the variables with the greatest expected influence, or greater ability to affect the network, were use of social networks during the week (1.204), satisfaction with muscles (1.101), use of social networks on weekends (0.971), and satisfaction with fat (0.931). For female students, the expected influence was greater for satisfaction with lower parts (1.224), satisfaction with muscles (1.062), use of social networks on weekends (0.979), and use of social networks during the week (0.797). These indices can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Network centrality indicators for females and males

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Betweenness | Closeness | Strength | Expected influence | Betweenness | Closeness | Strength | Influence expected |

| Income | − 0.667 | − 2.186 | − 1.720 | − 0.759 | − 0.962 | 0.000 | − 1.384 | − 0.437 |

| Agreeableness | − 0.667 | 0.092 | − 1.282 | − 1.018 | − 0.962 | 0.000 | − 1.296 | − 0.344 |

| Conscientiousness | − 0.667 | 0.454 | − 0.354 | − 0.036 | 0.165 | 0.000 | − 0.617 | 0.366 |

| Openness | 0.121 | − 0.751 | − 1.062 | − 0.230 | − 0.962 | 0.000 | − 1.230 | − 0.362 |

| Neuroticism | 2.702 | 2.151 | 0.739 | − 2.066 | 1.967 | 0.000 | 0.069 | − 1.958 |

| Extroversion | 0.767 | 0.252 | − 0.175 | 0.415 | 1.742 | 0.000 | − 0.494 | 0.288 |

| Satisfaction with fat | − 0.022 | 0.380 | 1.332 | 0.346 | 0.615 | 0.000 | 1.794 | 0.931 |

| External parts | − 0.667 | − 0.217 | − 0.307 | 0.447 | − 0.061 | 0.000 | 0.147 | − 0.648 |

| Satisfaction with muscles | 0.982 | 0.945 | 1.679 | 1.062 | 0.052 | 0.000 | 1.136 | 1.101 |

| Lower parts | − 0.667 | 0.177 | 0.740 | 1.224 | 0.165 | 0.000 | 0.806 | 0.443 |

| BMI | − 0.667 | − 0.325 | − 0.178 | − 1.162 | − 0.962 | 0.000 | − 0.315 | − 1.556 |

| Social media days of week | − 0.667 | − 0.658 | 0.039 | 0.797 | − 0.962 | 0.000 | 0.581 | 1.204 |

| Social media on weekends | 0.121 | − 0.315 | 0.550 | 0.979 | 0.165 | 0.000 | 0.804 | 0.971 |

BMI body mass index

Discussion

The main objective of this research was to evaluate the relationship between factors and facets of personality and satisfaction with BI in university students. In addition, relationships between BI and the use of media, BMI, and income were investigated, tracing profiles for a better understanding of the influence of the participants’ gender in these relationships. The objective of the study was achieved by demonstrating the specific association of personality factors with body satisfaction. Correlational analyses have advanced knowledge about BI-specific relationships with personality facets, as recommended by Allen and Robson (2020).

Regarding the relationships of the different dimensions of BI with personality, the results of the present study showed that the Neuroticism factor is strongly related to satisfaction with the body. The effect of the relationship is negative, indicating that the greater the expression of Neuroticism, the less body satisfaction with specific parts. High levels of Neuroticism indicate greater vulnerability, impulsivity, and anxious and depressed symptoms. This result is in agreement with other studies that investigated the relationship between these variables in the university population (Alcaraz-Ibáñez et al., 2019; Embacher et al., 2018; MacNeill et al., 2017; Tok et al., 2010). In addition to studies with university students, results with other populations also concluded this negative relationship between Neuroticism and BI (Allen & Robson, 2020; Allen & Walter, 2016). Furthermore, there was a relationship between all facets of Neuroticism and dissatisfaction with body dimensions in the present study, reinforcing the consistent findings of a relationship between these variables. These results, taken together, indicate that literature is unanimous on the existence of a relationship between Neuroticism and BI, regardless of the investigated population. Several studies allow the conclusion that the high expression of Neuroticism is related to different negative outcomes (Kroencke et al., 2020).

The Extroversion factor was positively correlated with three dimensions of body satisfaction in the present study: satisfaction with muscles, external parts, and lower parts. The association of the Extroversion factor with body satisfaction in university students finds divergent results in the literature, with studies that found a positive relationship between them (Alcaraz-Ibáñez et al., 2019; Tok et al., 2010) and studies that do not find a relationship (Embacher et al.., 2018; Soohinda et al., 2019). The divergence in these results may be explained by differences between the instruments used and other methodological variations in the studies. In addition, the Energy Level facet was positively correlated with all dimensions of body satisfaction. This facet assesses people’s energy and activity level, excitement, and enthusiasm (Soto & John, 2016), which may be associated with self-care practices and engagement in diverse activities, which may explain the association with body satisfaction.

The Conscientiousness factor was positively correlated with three dimensions of the ESSC: satisfaction with muscle, external parts, and lower parts. This result is in agreement with the literature with the same population, with other studies identifying the same relationship (Alcaraz-Ibáñez et al., 2019; MacNeill et al., 2017; Soohinda et al., 2019; Tok et al., 2010). Among the facets, it is highlighted that Productivity was correlated with all dimensions of body satisfaction in the present study. Productivity assesses a person’s propensity to engage in tasks that require persistence and reflect responsible behavior in the face of various aspects of life (Soto & John, 2016). The relationship of this facet with body satisfaction may reflect the tendency of individuals with higher Productivity scores to engage in self-care practices, such as physical exercise. The practice of physical exercises is associated with greater body satisfaction according to the meta-analysis by Hausenblas and Fallon (2006).

The Openness factor was positively associated with all ESSC dimensions, with the exception of muscle satisfaction; however, the correlations were of low magnitude. The association of the Openness factor and body satisfaction in university students finds different divergent conclusions in the literature, with studies that find a positive relationship between them (Alcaraz-Ibáñez et al., 2019; Tok et al., 2010) and studies without association (MacNeill et al., 2017; Soohinda et al., 2019), which again refers to possible methodological differences between the studies, especially the instruments. The facet Creative Imagination was the only one that was associated with all dimensions of the construct. It assesses an individual’s ability to be original and creative in ideas and in practice (Soto & John, 2016). One hypothesis for such a relationship is that this facet may reflect a greater level of openness to different types of BI, with a lower tendency to idealize a single body type.

Agreeableness was the only personality factor that did not present a significant relationship with the ESSC dimensions. The literature also presents conflicting results on the relationship between BI and this factor, with studies showing a positive association between the variables (MacNeill et al., 2017 [only for females]; Tok et al., 2010) and studies that did not find a significant association between them (Alcaraz-Ibáñez et al., 2019; Soohinda et al., 2019). It is also questioned whether the differences in the instruments used to assess the two constructs may be associated with differences in results. Only one facet of the Agreeableness factor, Confidence, showed positive correlations of low magnitude with the fat and muscle dimensions. One of the aspects evaluated by this facet is the tendency to overlook the defects of others (Soto & John, 2016). This may reflect a person’s greater tendency to tolerate more aspects of the body that do not conform to what he or she wants.

Regarding comparisons by sex, the results of the present study indicated that, in general, men have greater body satisfaction than women in the body fat, lower body, and external body dimensions. There are several studies in the literature that also found differences between men and women regarding BI, indicating greater dissatisfaction for females (Alves et al., 2017; Medeiros et al., 2018; Petry & Pereira Junior, 2019). This occurs both in studies with university students (Alves et al., 2017; Medeiros et al., 2018) and in the general population (Petry & Pereira Junior, 2019). A possible justification is the fact that there is an overvaluation of the BI for the female sex in social representations and in the media, which increases the unbridled search for the ideal body in women. Thus, this result indicates that when carrying out future studies on BI, it is important to consider the difference between the sexes, using group separation, mediation analysis by sex, or considering the equivalent proportion of men and women to compose the sample.

In view of these indications, in the present study, the multivariate network model was plotted separately by sex. In fact, the results indicated important differences, starting with the degree of association between the variables (sparsity), which was much stronger in the women’s network. This differentiated pattern of associations can be related to the specificities of each sex for both BI (Medeiros et al., 2018; Petry & Pereira Junior, 2019) and personality (McCrae & Costa, 2008). Neuroticism is one of the variables that can explain this difference, having a greater betweenness with other variables in the women’s network, which is a variable recognized for being associated with negative outcomes (Kroencke et al., 2020), such as worse subjective well-being (Lucas, 2018; Soto, 2019) and greater concern and rumination (Merino et al., 2016). In addition, muscle satisfaction and Extroversion were connected with many variables. Still, Neuroticism and muscle satisfaction established close relationships with others, evidencing the importance of these variables in the multivariate system. In view of this pattern of association, interventions with women in relation to BI may have promising results, given the degree of association, betweenness, and closeness between the variables. On the other hand, for men, there were no variables that were very close to the others, although Neuroticism and Extroversion were the variables that were most associated with others. The dimensions of satisfaction with fat, muscle, and lower body were strongly associated, indicating that even though it is important to assess BI by dimension, there is a more uniform trend towards satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the body. For men, interventions focusing on social media use and muscle satisfaction have greater potential to affect the other variables, most likely positively.

Regarding the relationship between media use and perception of BI, the results of bivariate analyses indicated a positive correlation between the number of hours spent on social networks during the week and on weekends, and a greater level of dissatisfaction with body image dimensions among participants in the ESSC. These results may reflect the fact that people with more contact with the imposition of the perfect body in the media have greater body dissatisfaction. Other studies in the literature pointed to a high influence of social networks on the perception of BI, in which both females and males were directly affected by the greater use of social networks (Nascimento et al., 2020; Rodgers et al., 2020; Santos & Gonçalves, 2020). This is possibly explained by the fact that social networks influence comparative behaviors related with dissatisfaction with one’s own body. Although as the analysis of the study is based on a correlational design, it is not possible to establish a causal relationship between the variables. In other words, it cannot be determined whether increased exposure to social networks leads to greater dissatisfaction with body image, or if individuals who are already dissatisfied with their body image are more inclined to engage with social networks in search of idealized images or ways to change their appearance. Thus, it is urgent to think of interventions that reduce the active search for ideal models of beauty in social networks, in the sense of promoting health and improving the relationship with the body.

In the network analysis, for men, the use of social networks during the week established strong associations with other variables. In addition, the use of social networks during the week and on weekends was among the variables with the greatest expected influence for both men and women. The expected influence refers to the greater capacity of the variable to affect the network; that is, they are variables that, when suffering effects, even if small, can affect the system as a whole. This result is relevant, as it suggests that changes in the use of social networks, whether in the quantity and, most likely, in the quality of content consumed, have the potential to change an entire system of relationships with BI. Clinical interventions can be thought of considering these results.

In this study, income showed low-magnitude correlations with three dimensions of body satisfaction in the bivariate analyses: fat, external parts, and lower parts. However, in the multivariate model of networks, this variable was not associated with the others, demonstrating that it does not exert great influence on the results. The relationship between income and BI is controversial in the literature, with findings about the relationship (Barreto et al., 2019) and no relationship between them (Cok, 1990). The prospective longitudinal study by Quick et al. (2013) helps to understand these results. Considering data separately for men and women, there were correlations between income and BI in the bivariate analyses, but not in the multivariate hierarchical linear regression model. Therefore, it is inferred that the effect of the interaction of income with other variables causes income to have lower explanatory power in multivariate models. Thus, other variables seem to have more influence on BI.

The present study presents relevant and unprecedented results about BI in the Brazilian context. The instruments used to assess the variables of interest enabled the precise operationalization of the object of study and allowed the assessment of constructs in a reliable and valid manner, as recommended by Thompson et al. (2018). The assessment of the relationship between personality facets and BI was not found in other studies investigated and provided an additional understanding on the subject. In addition, the investigations separated by sex clarify several points investigated in the literature. The study methodology followed replicable procedures involving a large sample of university students from different courses of public and private institutions and with income variability, with representatives from all Brazilian regions, giving greater robustness to the findings for the national context.

However, the study also has limitations. The main limitation involves the composition of the sample, with a great predominance of women (74.4%). It is known that sex influences both BI and personality, so future studies should invest in greater participation of men, who are usually a minority in almost all research on the subject (MacNeill et al., 2017; Soohinda et al., 2019). In addition, the selection of participants was based on convenience, which may have excluded university students with different results. Data collection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many university students were at increased risk of stress, anxiety, depression, and other psychological problems (Maia & Dias, 2020). These symptoms can affect college students’ relationship with their bodies (MacNeill et al., 2017). Due to the cross-sectional and correlational design of the study, including network analysis, it is not possible to determine the direction of the relationship between body image dissatisfaction and social network use. Thus, causation cannot be inferred, as there may have been other uncontrolled variables that influenced the results, as noted by Scully et al. (2023). Despite these limitations, the results of this research are promising, contributing to the advancement of the area in Brazil and providing guidelines and perspectives for future studies.

Finally, the findings of this study emphasize the importance of further research on the intricate and multifaceted topic of personality and body image dissatisfaction. Longitudinal studies are particularly encouraged to explore whether changes in personality over time are associated with changes in BI. To address these questions more effectively, future research could employ longitudinal designs while controlling for relevant variables. It would be valuable to investigate whether individual, interpersonal, health, and lifestyle factors (such as physical activity) can mediate or moderate the relationships between personality and BI.

Conclusion

This research found evidence of an association between dimensions of satisfaction with BI and personality factors and facets. Differences by sex were also found in the perception of BI, as well as the influence of the BMI and especially the use of social networks on the degree of satisfaction with the body. The results of this study are promising and may be of interest to researchers, but especially to health professionals working with young people who experience negative self-perceptions of the body. Considering these results, psychological and health interventions can promote psychoeducation regarding the quantity and quality of social media content for young people with poor BI.

It is known that social and media pressure for people to have an ideal body, considering a thin standard, can be associated with stress, depression, and poor self-esteem and affect the way people perceive BI, interacting with personality characteristics. The symptoms can affect college students’ relationship with their bodies bidirectionally. Stress, anxiety, and depression may worsen body image perception, or a distorted perception of body image may exacerbate these symptoms (MacNeill et al., 2017; Soares Filho et al., 2020). Similarly, body dissatisfaction and self-esteem are linked bidirectionally. Specifically, failure to attain cultural body ideals can lead to negative self-evaluation and increased vulnerability to environmental pressures over time in women with low self-esteem. Additionally, individuals with low self-esteem may experience increased vulnerability to environmental pressures over time due to negative self-evaluation resulting from not meeting cultural body ideals (Soohinda et al., 2019). Furthermore, the differences found by sex shed light on clinically important variables when working with young people with distorted BI.

Although promising, the results of this research are not fully conclusive given the complexity of the subject and the need for further reflection. Longitudinal studies are encouraged to determine whether changes in personality over time are related to varying perceptions of BI. Furthermore, future research may explore the potential moderating or mediating effects of individual, interpersonal, mental health symptoms, and lifestyle variables (such as physical activity) on the relationship between personality and BI.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed Consent

All participants included in this research have signed an Informed Consent Statement.

References

- Alcaraz-Ibáñez, M., Sicilia, A., & Paterna, A. (2019). Examining the associations between the Big Five personality traits and body self-conscious emotions. PsyCh Journal,9(3), 392–401. 10.1002/pchj.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M. S., & Robson, D. A. (2020). Personality and body dissatisfaction: An updated systematic review with meta-analysis. Body Image,33, 77–89. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Allen, M. S., & Walter, E. E. (2016). Personality and body image: A systematic review. Body Image,19, 79–88. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M. S., Robson, D. A., & Laborde, S. (2020). Normal variations in personality predict eating behavior, oral health, and partial syndrome bulimia nervosa in adolescent girls. Food Science & Nutrition,8(3), 1423–1432. 10.1002/fsn3.1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves, F. R., de Souza, E. A., de Paiva, C. D. S., & Teixeira, F. A. A. (2017). Dissatisfaction with body image and associated factors in university students. Cinergis,18(3), 204–209. 10.17058/cinergis.v18i3.9037 [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, J.T.T., Rendeiro, L.C., Nunes, A.R.M., Ramos, E.M.L.S., Ainett, W.S.O., Costa, V.V.L., & de Sá, N.N.B. (2019). Factors associated with dissatisfaction with body image in students of health courses in Belém-PA. Brazilian Journal of Obesity, Nutrition and Weight Loss, 13 (77), 120–128. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6987848. Accessed Aug 2021

- Breakwell, G. M., Hammond, S., Fife- Schaw, C., & Smith, J. A. (2010). Research Methods in Psychology (3rd ed.). Artmed. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., & Chen, Z. (2008). Extended Bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika,95(3), 759–771. 10.1093/BIOMET/ASN034 [Google Scholar]

- Cok, F. (1990). Body image satisfaction in Turkish adolescents. Adolescence,25(98), 409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto, A. C. C., & Vasconcelos, R. N. (2020). Eating disorders in adolescent girls: An analysis in the school environment. Brazilian Journal of Development,6(6), 37496–37504. 10.34117/bjdv6n6-326 [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L. L., Fowler, S. A., Best, L. A., & Both, L. E. (2020). The role of body image in the prediction of life satisfaction and flourishing in men and women. Journal of Happiness Studies,21(2), 505–524. 10.1007/s10902-019-00093-y [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y., & Dumas, D. (2020). Are personality measures valid for different populations? A systematic review of measurement invariance across cultures, gender, and age. Personality and Individual Differences,160, 109956. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.109956 [Google Scholar]

- Embacher, K. M., McGloin, R., & Atkin, D. (2018). Body dissatisfaction, neuroticism, and female sex as predictors of calorie-tracking app use amongst college students. Journal of American College Health,66(7), 608–616. 10.1080/07448481.2018.1431905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeln, R., Loach, R., Imundo, M. N., & Zola, A. (2020). Compared to Facebook, Instagram use causes more appearance comparison and lower body satisfaction in college women. Body Image,34, 38–45. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.04.007. 1740-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (2nd ed.). Artmed. [Google Scholar]

- Hausenblas, H. A., & Fallon, E. A. (2006). Exercise and body image: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Health,21(1), 33–47. 10.1080/14768320500105270 [Google Scholar]

- Hevey, D. (2018). Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine,6(1), 301–328. 10.1080/21642850.2018.1521283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata, E., & Pilati, R. (2010). Development and preliminary validation of the Situational Body Satisfaction Scale-ESSC. Psycho -USF,15(1), 1–11. 10.1590/S1413-82712010000100002 [Google Scholar]

- Kroencke, L., Geukes, K., Utesch, T., Kuper, N., & Back, M. D. (2020). Neuroticism and emotional risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research in Personality,89, 104038. 10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R. E. (2018). Exploring the associations between personality and subjective well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of Well-Being (pp. 257–271). DEF Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeill, L. P., Best, L. A., & Davis, L. L. (2017). The role of personality in body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Discrepancies between men and women. Journal of Eating Disorders,5(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s40337-017-0177-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia, B. R., & Dias, P. C. (2020). Anxiety, depression and stress in college students: The impact of COVID-19. Psychology Studies,37, 1–8. 10.1590/1982-0275202037e200067 [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2008). The five-factor theory of personality. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 159–181). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, T., Cunha, A., Lima, C. F. D., Ponte, V., Furtado, S., & Mendes, J. C. D. S. (2018). Positive body image in emerging adults: A study in a university context. In Proceedings of the 12th National Congress of Health Psychology, Lisboa, Portugal (pp. 813-821). ISPA-University Institute.

- Merino, H., Senra, C., & Ferreiro, F. (2016). Are worry and rumination specific pathways linking neuroticism and symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder and mixed anxiety-depressive disorder? PLoS ONE,11(5), e0156169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, L.D.S., Sousa, M.E., Medeiros, M.F., & Rezende, I.F.B. (2020). Body image and risks of eating disorders in university students. Science Magazine (In) Cena, 1 (11), 77 – 93. http://revistaadmmade.estacio.br/index.php/cienciaincenabahia/article/viewFile/8446/pdf8446. Accessed Aug 2021

- Neuman, W. L. (2014). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A. P. G., Fonseca, I. R., Almada, M. O. R. V., Acosta, R. J. L. T., Silva, M. M. D., Pereira, K. B., & Salomão, J. O. (2020). Eating disorders, body image and media influence in university students. Rev. sick _ UFPE online,14, 1–9. 10.5205/1981-8963.2020.245234 [Google Scholar]

- Petry, N.A., & Pereira Júnior, M. (2019). Evaluation of dissatisfaction with the body image of bodybuilders in a gym in São José-SC. Brazilian Journal of Sports Nutrition, 13 (78), 219 – 226. http://www.rbne.com.br/index.php/rbne/article/view/1323/877. Accessed Aug 2021

- Quick, V., Eisenberg, M. E., Bucchianeri, M. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in young adults: 10-year longitudinal findings. Emerging Adulthood,1(4), 271–282. 10.1177/2167696813485738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, M. E., & Harris, G. T. (2005). Comparing effect sizes in follow-up studies: ROC Area, Cohen’s d, and r. Law and Human Behavior,29(5), 615–620. 10.1007/s10979-005-6832-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, R. F., Kruger, L., Lowy, A. S., Long, S., & Richard, C. (2019). Getting Real about body image: A qualitative investigation of the usefulness of the Aerie Real campaign. Body Image,30, 127–134. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, R. F., Slater, A., Gordon, C. S., McLean, S. A., Jarman, H. K., & Paxton, S. J. (2020). A biopsychosocial model of social media use and body image concerns, disordered eating, and muscle-building behaviors among adolescent girls and boys. Journal Youth Adolescence,49(2), 399–409. 10.1007/s10964-019-01190-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M. S., & Gonçalves, V. O. (2020). Use of social networks, body image and media influence in academics of physical education courses. Itinerary Reflectionis,16(3), 1–18. 10.5216/rir.v16i3.58815 [Google Scholar]

- Scully, M., Swords, L., & Nixon, E. (2023). Social comparisons on social media: Online appearance-related activity and body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine,40(1), 31–42. 10.1017/ipm.2020.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaughnessy, J. J., Zechmeister, E. B., & Zechmeister, J. S. (2012). Metodologia de pesquisa em psicologia (9a ed.). AMGH Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L. P. R. D., Tucan, A. R. D. O., Rodrigues, E. L., Del Ré, P. V., Sanches, P. M. A., & Bresan, D. (2019). Body image dissatisfaction and associated factors: A study in young university students. Einstein,17(4), 1–7. 10.31744/einstein_journal/2019ao4642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares Filho, L. C., Batista, R. F. L., Cardoso, V. C., Simões, V. M. F., Santos, A. M., Coelho, S. J. D. D. A. C., & Silva, A. A. M. (2020). Body image dissatisfaction and symptoms of depression disorder in adolescents. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 54(1), 1–10. 10.1590/1414-431X202010397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Soohinda, G., Mishra, D., Sampath, H., & Dutta, S. (2019). Body dissatisfaction and its relation to Big Five personality factors and self-esteem in young adult college women in India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry,61(4), 400–404. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_367_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C. J. (2019). How replicable are links between personality traits and consequential life outcomes? The Life Outcomes of Personality Replication Project. Psychological Science,30, 711–727. 10.1177/0956797619831612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2016). The Next Big Five Inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,113(1), 117–143. 10.1037/pspp0000096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2017). Short and extra-short forms of the Big Five Inventory–2: The BFI-2-S and BFI-2-XS. Journal of Research in Personality,68, 69–81. 10.1016/j.jrp.2017.02.004 [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. K., Schaefer, L. M., & Dedrick, R. F. (2018). On the measurement of thin-ideal internalization: Implications for interpretation of risk factors and treatment outcome in eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders,51(4), 363–367. 10.1002/eat.22839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tok, S., Tatar, A., & Morali, S.L. (2010). Relationship between dimensions of the five-factor personality model, body image satisfaction and social physique anxiety in college students. Studia Psychologica, 52 (1), 59 – 67. https://www.studiapsychologica.com/uploads/TOK_01_vol.52_2010_pp.59-67.pdf. Accessed Aug 2021

- Tregunna, R. L., & Wood, D. (2020). Let’s talk about sex: A review of expectations, body image and sexual function in exstrophy. Journal of Clinical Urology,13(4), 309–315. 10.1177/2051415819892458 [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., Byrne, N. M., Kenardy, J. A., & Hills, A. P. (2005). Influences of ethnicity and socioeconomic status on the body dissatisfaction and eating behavior of Australian children and adolescents. Eating Behaviors,6(1), 23–33. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccagni, L., Rinaldo, N., Bramanti, B., Mongillo, J., & Gualdi-Russo, E. (2020). Body image perception and body composition: Assessment of perception inconsistency by a new index. Journal of Translational Medicine,18(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s12967-019-02201-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler-Hill, V., & Shackelford, T. K. (2018). The SAGE Handbook of Personality and Individual Differences: Origins of Personality and Individual Differences (Vol. 2). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Not applicable.