Abstract

Maintenance of adequate blood perfusion and oxygen delivery is essential for cerebral metabolism. Cerebral oximeters based on near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) have been used for noninvasive, continuous, real-time monitoring of cerebral oxygen saturation and management of cerebral oxygen adequacy perioperatively and intraoperatively in various clinical situations, such as cardiac surgery, anesthesia, and cerebral auto-regulation. In this study, a portable and modular cerebral tissue oximeter (BRS-1) was designed for real-time detection of regional oxygen saturation over the brain, finger, or other targeted body tissues, as well as for wireless cerebral oxygenation monitoring. The compact and lightweight design of the system makes it easy to use during ambulance transport, in an emergency cart, or in an intensive care unit. The system performance of the BRS-1 oximeter was evaluated and compared with two US FDA-cleared cerebral oximeters during a controlled hypoxia experiment. The results showed that the BRS-1 oximeter can be used for real-time detection of cerebral desaturation with an accuracy similar to the two commercial oximeters. More importantly, the BRS-1 oximeter is capable of capturing cerebral oxygen saturation wirelessly. The BRS-1 cerebral oximeter can provide valuable insights for clinicians for real-time monitoring of cerebral/tissue perfusion and management of patients in prehospital and perioperative periods.

Keywords: Cerebral oximeter, Near-infrared spectroscopy, Regional cerebral oxygen saturation

Introduction

Due to the high metabolic demand, limited capacity for energy storage, and low hypoxia tolerance of the brain, the real-time detection and management of regional oxygen saturation is critical for maintaining adequate blood perfusion and oxygen supply to the brain for metabolic demands (Willie et al. 2014). Cerebral ischemia may lead to structural and functional damage of the cerebral vasculature, and consequently may increase the risk of neurologic damage, including cognitive dysfunction and neurological complications. Clinicians and researchers have long sought reliable tools that allow real-time monitoring of the adequacy of cerebral or tissue perfusion and oxygen saturation.

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is an optical neuroimaging technique pioneered by Jobsis (1977), which is noninvasive, portable, cost-effective, ecological, user-friendly, continuous, and can be used for longitudinal real-time monitoring. The main physical principles of NIRS are as follows: (1) Near-infrared light can traverse head tissues because of the relative transparency of the human skull to the light in this optical window (650–950 nm). (2) Changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated (HbR) hemoglobin concentrations can be resolved because of different absorption characteristics of the two chromophores in the near-infrared spectrum (Ferrari and Quaresima 2012; Pinti 2018).

NIRS-based oximeters include conventional pulse oximeters and modern cerebral tissue oximeters. Pulse oximeters have been used for monitoring regional oxygen saturation in clinical applications for a number of years. However, pulse oximeters only provide peripheral arterial saturation (SpO2) and rely on the pulse sequence to conduct the measurement. The brain blood circulation is self-regulated and relatively independent of the general body blood circulation. Moreover, as one of the most energy demanding organs, the brain has a high oxygen extraction rate (Sudy et al. 2019). Thus, SpO2 cannot provide precise estimates of the regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) of the brain. A previous study found that cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) detection based on NIRS could reflect changes in oxygen desaturation earlier than a conventional pulse oximeter during periods of apnea during airway surgery (Tobias 2008).

Unlike noninvasive pulse oximeters, cerebral and tissue oximeters do not require a pulse sequence (Sandroni et al. 2019) but, rather, detect cerebral (rSO2) and tissue (StO2) oxygen saturation by a weighted average measurement of hemoglobin changes in venous, arterial, and capillary blood (Bevan 2015) in intracerebral and peripheral tissue. Commercial cerebral oximeters often assume a fixed ratio of either 70:30 or 75:25 for venous to arterial blood volume in the brain (Ghosh et al. 2012). Cerebral and tissue oximeters provide a contemporaneous evaluation of the balance between regional cerebral oxygen supply and demand. Owing to their unique advantages, NIRS-based oximeters have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for real-time noninvasive monitoring of cerebral (rSO2) and tissue (StO2) oxygen saturation in a wide range of clinical applications, such as cardiac surgery (Vranken et al. 2017), anesthesia (Badenes et al. 2016), neonatology (Pichler et al. 2019), cerebrovascular autoregulation (Chan and Aneman 2018), and muscle perfusion assessment (Scholkmann and Scherer-Vrana 2020). A study reported that rSO2 monitoring may provide early warning of adverse neurological outcomes in cardiac surgery (Steppan and Hogue 2014) and has the potential to reduce the risk of death from severe brain injury in preterm infants (Hansen et al. 2019). Intraoperative monitoring of rSO2 is helpful for guiding neuroanesthesia and predicting outcome in patients during endovascular treatment (Badenes et al. 2016). It was reported that rSO2 can be used as a valuable tool for detecting hypoxemia during hypobaric chamber training (Ottestad et al. 2018). The detection of rSO2 has unique advantages over other methods (e.g., transcranial doppler, jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation (SjvO2), multichannel EEG, etc.) (Bevan 2015) and may be able to serve as a useful clinical surrogate for cerebral blood perfusion during longitudinal bedside monitoring of cerebrovascular oxygenation.

To improve the applicability of this technique and to make it available for novel clinical researches and practice, a miniaturized portable cerebral tissue oximeter (BRS-1) was developed. The BRS-1 oximeter is designed for real-time continuous monitoring of regional cerebral (rSO2), tissue (StO2), and pulse (SpO2) oxygen saturation, simultaneously. More importantly, this oximeter is capable of capturing cerebral oxygen saturation wirelessly. The BRS-1 cerebral oximeter can provide useful insights for clinicians by monitoring cerebral/tissue oxygenation saturation and aid with the management of patients in various clinical applications, such as the perioperative period, ambulance transport, prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and prehospital monitoring.

Instrumentation

Overview

In this study, a portable, miniaturized and modular cerebral oximeter (BRS-1) was designed for real-time detection of changes in regional oxygen saturation in the brain, finger, or other targeted body tissue. The schematic diagram of the custom-designed oximeter (BRS-1) is shown in Fig. 1. The display unit of the cerebral oximeter (BRS-1) is 305 mm × 262 mm × 130 mm and weighs 2.8 kg. The connection module used for connecting the optical module is 144 mm × 104 mm × 27 mm and weighs 200 g. Figure 2 shows a picture of the BRS-1 cerebral oximeter. The central processing unit (Linux IM6XUL) is the core part of the cerebral oximeter. It is responsible for data display, data processing, data storage, and system control of the monitor. The central processing unit consists of several components and interfaces, including a display screen (12 inches), touch panel screen, start button, alarm lamp and horn, storage SD card, electricity and voltage detection module, and power access monitoring module. External interfaces include VGA video output, wired network, wireless WiFi, Bluetooth, USB interface, serial port, and RS485.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the cerebral oximeter (BRS-1)

Fig. 2.

Photograph of the BRS-1 oximeter. The oximeter consists of two cerebral sensor probes for measuring regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2), two tissue sensor probes for measuring tissue oxygen saturation (StO2), and one pulse sensor probe for measuring peripheral arterial saturation (SpO2). Moreover, the rSO2 can be monitored wirelessly by the WORTH band if the WORTH band is connected to the BRS-1 oximeter via Bluetooth

Optical module

The BRS-1 cerebral oximeter utilizes three wavelengths, 735 nm, 810 nm, and 850 nm, of light emitting diodes (LED) sources (SMT735/810/850) for time-multiplexing illumination. The average output power of the source is approximately 4 mW. Cerebral (rSO2), tissue (StO2) and pulse (SpO2) oxygen saturation can be measured simultaneously using our self-designed BRS-1 oximeter. The oximeter uses flexible disposable sensors with integrated NIRS sources and detectors that can be simultaneously arranged over different locations on the body. Specifically, two cerebral sensor probes can be arranged over each side of the forehead to measure cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2). This arrangement allows detection of the ischemia-susceptible cortical area at its border (Moody et al. 1990; Naidech et al. 2008). Two tissue sensor probes can be arranged on other body locations to monitor tissue oxygen saturation (StO2). Each sensor probe consists of one source and two detectors (silicon PIN photodiode). The two light detectors of the BRS-1 system are arranged 30 mm and 40 mm away from the light source, respectively. The sensor probe, which is made of a flexible, disposable, and adhesive medical material, is incorporated for stable and efficient optode-tissue coupling. Additionally, one channel can be used to measure peripheral arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2). The wavelengths of the sources used for SpO2 measurement are 660 nm and 905 nm. Importantly, the BRS-1 oximeter can also connect a custom-designed wearable wireless cerebral oximeter WORTH band (Si et al. 2021) through a Bluetooth module, so that the cerebral oxygen saturation can be monitored wirelessly.

Power supply and battery management

To integrate the power supply electronics with analog electronics for different voltage levels, the power supply system was designed rigorously to avoid electronic crosstalk. The power supply system of the BRS-1 cerebral oximeter includes an external power supply module and a rechargeable lithium battery (ICR18650-26) with a total capacity of 15,600 mAh, which is capable of working continuously for 5 h without recharging. The voltage of the lithium battery is stabilized to 5 V through a boost circuit. The central processing unit has a 5 V to 3.3 V voltage conversion module, which provides 3.3 V voltage to the system. Moreover, the oximeter can work through an external power supply and can charge the lithium battery at the same time. The rechargeable lithium battery is useful in case of power failure or during the patient transfer process. A 220 V to 5 V adapter module is used to provide 5 V power supply voltage for the central processing control board. Its low-power consumption design and efficient data acquisition sequence allows minimized heating and longer battery lifetime for long-term continuous monitoring.

Data display and storage

The BRS-1 cerebral oximeter can be operated by a touch panel. Moreover, the oxygen saturation data of the oximeter can be displayed on an external monitor at the same time, which is useful for several clinical applications such as perfusion and anesthesia. The oxygen saturation data can be saved to a USB memory device for further analysis and processing.

Algorithm

The algorithm of the BRS-1 cerebral oximeter is based on the modified Beer-Lambert law (MBLL) (Kocsis et al. 2006) and spatially resolved spectroscopy (SRS) technology (Suzuki et al. 1999; Mccormick et al. 1991; Ferrari et al. 2004; Kovacsova et al. 2018); these methodologies are commonly used in several commercial cerebral oximeters. The SRS technique is mainly based on changes in the optical intensity of light reflected from neighboring “shallow” and “deep” areas of the cerebral cortex. Combining two closely spaced detectors in SRS technology can make it possible to measure light attenuation as a function of source-detector separation and can inhibit the influences of extracerebrally reflected photons and inter-subject differences in photo-intracranial tissue coupling (Ghosh et al. 2012). More details about the algorithm can be found in our previous study (Si et al. 2021).

Experiments and results

Study design

Cerebral and somatic oxygen saturation validation experiment

Twelve subjects (eight males, age 20–30) were recruited for this experiment. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were right-handed, with no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. The experimental paradigm was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Neurosurgery of Beijing Tiantan Hospital and Xuanwu Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

The cerebral and somatic oxygen saturation validation experiment was conducted to evaluate the reliability and accuracy of the custom-designed BRS-1 oximeter and the FDA-cleared FORE-SIGHT oximeter in monitoring cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2), as well as tissue oxygen saturation (StO2) and pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) synchronously during a controlled hypoxia sequence. The protocol of this experiment was designed based on previous publications (Benni et al. 2018; Tomlin et al. 2017). During the experiment, the level of oxygen within the blood was gradually decreased in a controlled manner by altering the inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2) to achieve five pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) plateaus between 100 and 75%. Specifically, baseline (B, 100–97%, normal room air breathing) data were recorded before the onset of the hypoxia sequence. The four SpO2 platform levels were, in turn, platform1 (P1, 97–90%), platform2 (P2, 90–83%), platform3 (P3, 83–77%), and platform4 (P4, 77–70%); the experimental paradigm is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The experimental paradigm of the controlled hypoxia sequence for the validation experiment

During the controlled hypoxia experiment, pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) was detected using a commercially available finger pulse oximeter (YX301, Yuwell Medical Systems) on the index finger. Meanwhile, the sensor pads of the BRS-1 oximeter and the FORE-SIGHT oximeter were bilaterally placed on the left and right side of the forehead, and the wireless WORTH band was also arranged over the forehead for real-time synchronous cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) monitoring. The placements of the sensor pads of different oximeters were alternated by even or odd participant number. Tissue oxygen saturation (StO2) was also recorded synchronously by the BRS-1 oximeter and the FORE-SIGHT oximeter on the inner side of the forearm. Additionally, radial artery puncture and catheterization were conducted to invasively measure the blood gases during the controlled hypoxia experiment. Radial artery blood was sampled five times for each platform, yielding 25 blood samples in total. Blood gas analysis was performed using the GEM Premier 4000 system (Instrumentation Laboratory Co. USA). The participant’s tolerance of the experiment was continuously evaluated and, if necessary, the study was prematurely terminated at the participant’s request.

Comparison experiment between the BRS-1 and two FDA-cleared oximeters

Thirteen healthy participants (ten males, age 23–35) were recruited for this study. They all had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were right-handed, with no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. The experimental paradigm was approved by the ethics committee of the Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

This experiment was conducted to compare the consistency of cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) monitoring between the BRS-1 oximeter, the FORE-SIGHT (CAS Medical Systems, Branford, CT) oximeter, and the INVOS 5100 (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) oximeter. Specifically, for comparison, the sensor pads of two different oximeters (BRS-1 vs. FORE-SIGHT; BRS-1 vs. INVOS 5100) were symmetrically arranged on the left and right forehead for real-time synchronous rSO2 acquisition. First, the baseline (B, 100–97%, normal room air breathing) data were recorded before the onset of the hypoxia sequence. During the desaturation experiment, the level of oxygen within the blood was gradually changed in a controlled manner by alternating the inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2) to reduce the pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) to (77–70%). Finally, during the recovery period (R, 97–100%), cerebral oxygen saturation values were further acquired while breathing normal air when the desaturation period was finished; the experimental paradigm is shown in Fig. 4. The placements of the sensor pads were alternated by even or odd participant number. To minimize the inter- and intrasubject differences during the experiment, the sensors were consistently arranged 3 cm above the superciliary line with the long axis parallel to the intra-aural line (Gregory et al. 2015). The participant’s tolerance of the experiment was continuously evaluated and, if necessary, the study was prematurely terminated at the participant’s request. In this study, all of the participants successfully completed the experiments and reliable data were acquired from all of them.

Fig. 4.

The experimental paradigm of the controlled desaturation sequence for the comparison experiment

Data analysis

The data were analyzed on the MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA) 2019a platform. In this study, the results are represented as means ± standard error (SE), unless otherwise mentioned. Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS platform. T tests and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to characterize the differences between different variables. For the post hoc analysis, the Bonferroni algorithm was used. The Pearson correlation was conducted to investigate the correlation between the different conditions. The results were evaluated at a 95% confidence interval and a statistically significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Results of the validation experiment

To fully evaluate the system performance of the custom-designed BRS-1 oximeter, the reliability and accuracy of the custom-designed BRS-1 oximeter in measuring rSO2, StO2, and SpO2 were evaluated and compared with the FDA-cleared FORE-SIGHT oximeter and blood gas analyzer GEM Premier 4000 system.

As shown in Fig. 5, during the controlled hypoxia sequence for the validation experiment, the oxygen level within the blood was slowly reduced in a controlled manner by changing the inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2) to obtain five SpO2 plateaus between 100 and 75%. Specifically, these were baseline (B, 100–97%, normal room air breathing), platform1 (P1, 97–90%), platform2 (P2, 90–83%), platform3 (P3, 83–77%), platform4 (P4, 77–70%). Throughout the experiment, the arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) was invasively measured by a blood gas analyzer (GEM Premier 4000) as it decreased from 99.23 ± 0.18% to 75.59 ± 1.37%. The noninvasive measurement of the pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) measured by the YUWELL and the BRS-1 oximeters decreased from 99.33 ± 0.14% to 73.67 ± 0.87%, and from 98.67 ± 0.14 to 74.67 ± 1.07%, respectively. The ANOVA results showed that there were no significant differences in the group-averaged SpO2 between the BRS-1 oximeter and the YUWELL pulse oximeter as well as between the BRS-1 oximeter and the GEM Premier 4000 blood gas analyzer, F(2,897) = 0.914, p = 0.401.

Fig. 5.

Group-averaged results of the changes in different oxygen saturation values for the validation experiment

Correspondingly, the cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) measured by the FORE-SIGHT oximeter and the BRS-1 oximeter decreased from 73.75 ± 1.21% and 74.01 ± 1.07% to 57.58 ± 0.82% and 57.67 ± 0.97%, respectively. In addition, the rSO2 measured by WORTH band wireless oximeter changed from 74.25 ± 1.05% to 57.92 ± 0.96%. The ANOVA results showed that there were no significant differences in the group-averaged oxygen saturations between the BRS-1 oximeter, the FORE-SIGHT oximeter, and the WORTH band wireless oximeter, F(2,897) = 0.072, p = 0.93.

At the same time, the tissue oxygen saturation (StO2) recorded by the FORE-SIGHT oximeter and the BRS-1 oximeter dropped from 72.25 ± 1.17% and 71.58 ± 1.83% to 66.92 ± 0.71% and 67.67 ± 0.72%, respectively. The StO2 values of the BRS-1 oximeter were slightly higher than those of the FORE-SIGHT oximeter, but the difference was not statistically significant.

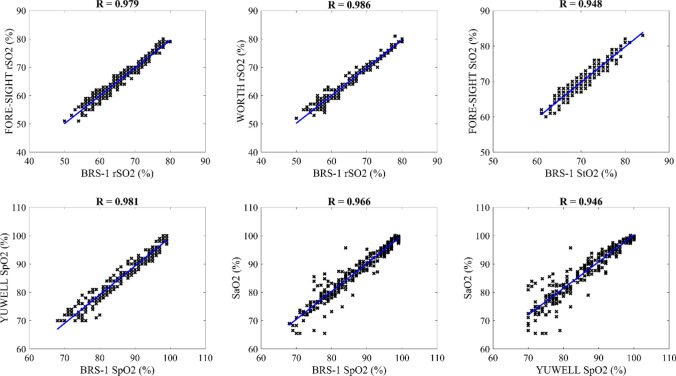

The correlation between different oxygen saturation indexes were also compared, as shown in Fig. 6. Specifically, the cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) values of the BRS-1 and FORE-SIGHT oximeters were significantly correlated with each other (R = 0.979, p < 0.01). The correlation of the rSO2 recordings between the BRS-1 and the wireless WORTH band was also statistically significant (R = 0.986, p < 0.01). Additionally, the tissue oxygen saturation (StO2) readings of the BRS-1 oximeter and the FORE-SIGHT oximeter were significantly correlated with each other (R = 0.948, p < 0.01). Moreover, the correlation values of the pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) between the different devices were consistently significant. Specifically, the correlation coefficient of the SpO2 values between the BRS-1 oximeter and the YUWELL pulse oximeter was 0.981 (p < 0.01). In addition, the arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) measured by the blood gas analyzer was significantly correlated with the SpO2 measured by the BRS-1 oximeter as well as by the YUWELL pulse oximeter, the correlation coefficients were 0.966 (p < 0.01) and 0.946 (p < 0.01), respectively.

Fig. 6.

Correlation results between different oxygen saturation indexes for the controlled hypoxia experiment

Results of the comparison experiment

The waveforms of the oxygen saturation during the controlled desaturation experiment are shown in Fig. 7. During the controlled desaturation experiment, the blood oxygen content was decreased gradually in a controlled manner by adjusting the inspired oxygen concentration to obtain arterial oxygen saturation (recorded by a finger pulse oximeter) plateaus between 100 and 75%. The performances of different oximeters were compared in two runs, that is BRS-1 vs. FORE-SIGHT and BRS-1 vs. INVOS 5100. The absolute values of rSO2 during the baseline period and the desaturation period for different oximeters were compared quantitatively. Additionally, the relative rates of change in rSO2 were further calculated to test the performance of the different devices.

Fig. 7.

Changes in cerebral oxygen saturation of a typical participant during the controlled desaturation experiment. The red, blue, cyan, and green lines indicate the rSO2 of the BRS-1 oximeter, the rSO2 of the FORE-SIGHT oximeter, the rSO2 of the INVOS 5100 oximeter, and the SpO2, respectively

With the continuous decrease in the inhaled oxygen concentration, the SpO2 decreased correspondingly from 96.2 ± 0.5 to 76.9 ± 0.5%. At the same time, the cerebral oxygen saturation measured by the BRS-1 and FORE-SIGHT oximeters fell from 73.2 ± 0.9 and 71.8 ± 0.7% to 58.6 ± 1.5 and 56.6 ± 0.7%, respectively. After the controlled hypoxia sequence, the participants were requested to breathe normal room air and the data were further acquired for five minutes. Note that once the inhalation of the low concentration oxygen was stopped, the SpO2 and rSO2 increased immediately. Specifically, the SpO2 returned to 98.0 ± 0.2%, which was slightly higher than the baseline level, but the difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, the rSO2 measured by the BRS-1 and the FORE-SIGHT oximeters also increased immediately and steeply to 71.4 ± 1.5% and 68.4 ± 2.7%, respectively. The difference in the absolute rSO2 between the recovery and baseline period was not statistically significant for either the BRS-1 or the FORE-SIGHT oximeters. Interestingly, the cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) measured by the BRS-1 oximeter and FORE-SIGHT oximeter returned to the baseline 15.4 ± 3.2 s, p < 0.05 and 11.5 ± 3.1 s, p < 0.05 earlier than the SpO2, respectively.

For the comparison between the BRS-1 and INVOS 5100C oximeters, when the SpO2 dropped from 96.8 ± 0.4 to 78.1 ± 0.5%, the corresponding cerebral rSO2 values decreased from 73.1 ± 0.9 and 74.1 ± 1.5% to 60.1 ± 1.5 and 54.2 ± 1.1% for the BRS-1 oximeter and the INVOS 5100 oximeter, respectively. The absolute rSO2 values of the BRS-1 were larger than those of the INVOS 5100 systems, but this time the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). When the low concentration oxygen was stopped, the SpO2 returned to 98.2 ± 0.2% while the rSO2 measured by the BRS-1 and INVOS 5100 increased to 73.0 ± 0.8% and 74.2 ± 1.6%, respectively. Note that the rSO2 measured by the BRS-1 oximeter and INVOS 5100 respectively returned to the baseline 20.1 ± 4.4 s, p < 0.05 and 16.4 ± 4.1 s, p < 0.05 earlier than the SpO2.

The correlation of the absolute rSO2 values during the controlled desaturation experiment were further calculated to compare the differences between different devices more comprehensively. The correlation results of the cerebral oxygen saturation during the controlled desaturation experiment for different cerebral oximeters are illustrated in Fig. 8. Specifically, there was a significant linear correlation between the rSO2 values of the BRS-1 and the FORE-SIGHT oximeters, the Pearson correlation coefficient (R) was 0.924 (p < 0.001). Similarly, the changes in rSO2 values between the BRS-1 and the INVOS 5100 oximeters were linearly correlated with each other, R = 0.857 (p < 0.001).

Fig. 8.

Correlation results of the cerebral oxygen saturation between different cerebral oximeters during the controlled desaturation experiment

Discussion

The human brain, which represents about 2% of body weight but consumes about 20% of body energy, has a high oxygen demand but low hypoxia tolerance (Andreone et al. 2015). The major goal in the hemodynamic management of the cerebrovascular circulation is to maintain adequate blood perfusion and oxygen delivery for metabolic needs (Moerman and Hert 2015). Continuous real-time monitoring of the adequacy of cerebral oxygenation could provide important clinical therapeutic information. NIRS-based oximeters can improve preoperative risk assessment and provide more comprehensive intraoperative monitoring of cerebral oxygenation in a wide range of clinical scenarios, such as cardiac surgery, anesthesia, and cerebrovascular autoregulation (Steppan and Hogue 2014).

Advantages of the BRS-1 cerebral oximeter

Pulse oximeters have been widely used in clinical applications for several years, but they only measure arterial blood oxygen saturation and require pulsations to conduct the measurement. The measurement of jugular venous oxygen saturation (SjvO2) has been used to detect cerebral oxygen saturation. However, the measurement is difficult to extend to several clinical applications because it is typically invasive (requiring placement of catheters into the jugular bulb). The insertion of catheters may induce both a technical challenge and a risk of infection. Moreover, the changes in SjvO2 cannot be monitored in real time and, thus, may miss the onset of an ischemic stroke. Cerebral oximeters, however, measure the cerebral oxygenation even in pulseless situations and reflect the balance of oxygen supply and demand at the targeted brain area and thereby the local cerebral metabolism. Monitoring cerebral oxygen saturation is useful for early detection of cerebral hypoperfusion and ischemia and, thereby, of preventing and reducing neurologic complications and cognitive dysfunction.

Owing to its unique advantages of noninvasiveness, portability, continuous monitoring and user-friendliness, NIRS-based cerebral oximeters have the potential to become valuable tools for monitoring the adequacy of cerebral oxygen saturation and providing useful information for clinicians to manage and optimize patient care in clinical situations. In 1991, McCormick et al., used a commercial cerebral oximeter (INVOS 2910, Somanetics, Troy, Mich.) to monitor regional cerebral oxygen saturation during transient cerebral hypoxia in the human brain (McCormick et al. 1991). Since then, several NIRS-based commercial cerebral oximeters have become available. A randomized, multi-center, multi-national clinical study used a NIRS-based INVOS 5100 (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to monitor cerebral regional oxygen saturation in preterm neonates during the immediate transition after birth. The results showed that rSO2 detection during immediate transition is feasible and helpful for managing cerebral oxygenation and improving the outcomes of preterm neonates (Pichler et al. 2019). The FORE-SIGHT (CAS Medical systems, Inc., Branford, CT) oximeter was used for real-time detection of cerebral oxygen saturation in children with congenital heart disease and chronic hypoxemia (Kussman et al. 2017). NIRO-200 NX (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.) was used for regional rSO2 detection and risk management in carotid artery stenting. The results showed that monitoring cerebral oxygen saturation is useful for detecting ischemic intolerance and cerebral hyperperfusion during carotid artery stenting (Terakado et al. 2019). Hori et al. used an ultrasound-tagged NIRS (UT-NIRS) system monitoring cerebral autoregulation in cardiac surgery patients. The results showed a statistically significant correlation in cerebral blood flow between the UT-NIRS system and transcranial Doppler (TCD) (Hori et al. 2015). However, these commercially available oximeters often consist of a control unit, several optodes, and connection fibers/wires for data transmission. Therefore, this kind of design can only be used as bedside monitors. There is still a lack of a wireless device that could expand cerebral oxygenation monitoring to tight spaces, such as emergency carts or an ambulance, or for use in sports science.

To improve the applicability and to expand into new fields of clinical research and practice, a miniaturized portable cerebral tissue oximeter (BRS-1) was developed. The BRS-1 oximeter allows non-invasive, continuous real-time monitoring of cerebral (rSO2), tissue (StO2), and pulse (SpO2) oxygen saturation simultaneously. Importantly, the BRS-1 system can be used not only for traditional uses but also for wireless monitoring. Owing to the unique advantages of the BRS-1 oximeter, it can be used for oxygenation monitoring in a wide variety of applications, such as investigating brain metabolism, managing cerebral oxygenation in emergency carts or intensive care units, assessing cerebral auto-regulation, and permitting studies of muscle tissue oxygenation for rehabilitation and sports science, etc.

System performance of the BRS-1 cerebral oximeter

The reliability and accuracy of the custom-designed BRS-1 oximeter

The reliability and accuracy of the custom-designed BRS-1 oximeter and the FDA-cleared FORE-SIGHT oximeter in monitoring of cerebral (rSO2), tissue (StO2) and pulse (SpO2) oxygen saturation simultaneously were compared during the controlled hypoxia sequence. The results showed that both the BRS-1 and the FORE-SIGHT oximeters revealed changes in rSO2 during the controlled hypoxia sequence. With a decrease in SpO2, the rSO2 and the StO2 decreased gradually. Note that the absolute values and rates of change of these three different oxygen saturation indexes (SpO2, rSO2, and StO2) differed from each other. Specifically, during the controlled hypoxia sequence, the range of the change in SpO2 was 99–74% while the ranges of the changes in rSO2 and StO2 were about 74–58% and 72–67%, respectively. The group-averaged percentage point reduction in SpO2 (about 25%) was larger than those of the rSO2 (about 16%) and StO2 (about 5%) during the controlled hypoxia sequence.

Additionally, the correlation results between the different oxygen saturation indexes were further compared quantitatively. The statistical results showed that the rSO2 and StO2 levels measured by the BRS-1 and FORE-SIGHT oximeters were significantly correlated, indicating that the BRS-1 oximeter can be used for noninvasive, real-time detection of rSO2 and StO2 with an accuracy comparable to those of the FORE-SIGHT oximeter. Importantly, the correlation coefficient between the SaO2 measure by the blood gas analyzer (GEM Premier 4000) and the SpO2 measured by the BRS-1 oximeter was statistically significant.

Comparison between the BRS-1 and two FDA-cleared oximeters

The system performance of the BRS-1 oximeter was further evaluated and compared with two FDA-cleared oximeters, FORE-SIGHT and INVOS 5100 by monitoring the changes in rSO2 using the desaturation experiment. Specifically, during the controlled desaturation sequence, the changes in rSO2 were detected in real time by the BRS-1 and the FORE-SIGHT/INVOS 5100 oximeters. All three oximeters showed significant decreases in rSO2 during the desaturation experiments. The magnitude of the absolute value of rSO2 and the correlation coefficients during the controlled hypoxia experiment were calculated to compare the performance between the three oximeters.

Throughout the entire controlled desaturation sequence, the absolute rSO2 values of different oximeters were compared quantitatively. Specifically, when the SpO2 decreased as a result of lowering the inspired oxygen concentration, the rSO2 measured by the BRS-1 oximeter and the FORE-SIGHT oximeter decreased correspondingly. A similar trend was also obtained when the BRS-1 oximeter was compared with the INVOS 5100 oximeter. Note that the reduction in SpO2 was significantly higher than that of rSO2 throughout the controlled hypoxia experiment. The reason may be the blood compensatory mechanism, in which, when hypoxia occurs, blood is preferentially supplied to the brain.

When the hypoxia sequence was stopped, the SpO2 and rSO2 increased immediately and steeply to the baseline level. It is noteworthy that the delay time for the rSO2 to return to the baseline for the BRS-1 and FORE-SIGHT was significantly shorter than that of the SpO2. A similar trend was also observed when the BRS-1 was compared with the INVOS 5100 oximeter. It has been reported that cerebral rSO2 routinely detects developing oxygen imbalances before they are detected by pulse oximeters. The physiological characteristics of cerebral rSO2 and the extraordinarily high oxygen consumption of the brain make it better suited for the early detection of developing hypoxemia than the pulse oximeter (Tobias 2008).

Additionally, the correlation coefficients of the rSO2 during the controlled desaturation sequence were further compared quantitatively between different oximeters. Specifically, the changes in absolute rSO2 between the BRS-1 and FORE-SIGHT oximeters were significantly correlated with each other. Similarly, the rSO2 measured by the BRS-1 and the INVOS 5100 oximeters were also highly consistent. The correlation coefficient of the BRS-1 vs. FORE-SIGHT was higher than that of the BRS-1 vs. INVOS 5100. One of the possible explanations is that the arterial versus venous contribution of tissue is set at 30/70 for both the FORE-SIGHT and BRS-1 systems but is set at 25/75 for the INVOS (Benni et al. 2018; Tomlin et al. 2017). Another possible reason is that the differences in optical module specification (such as, source-detector distances, light sources, detectors, light wavelengths, etc.) may also affect the results. The findings of the current study confirmed that the BRS-1 oximeter can be used for the real-time measurement of cerebral oxygen saturation with a performance that is similar to those of the two FDA-cleared commercial oximeters, the FORE-SIGHT and the INVOS 5100 oximeters.

Limitations

Limited sample size is one of the limitations in this study. We hope that further studies will be able to accumulate samples from multiple centers using different clinical applications. This will lead to further improvements in the technology, design, and performance of the BRS-1 oximeter. The lack of standardization of clinical NIRS-based oximeters and reliable validated reference rSO2 values remains a shortcoming when trying to compare different oximeters. Further investigation and technological progress are necessary to clarify these issues before such oximeters can be introduced more widely in clinical applications. Although there are some limitations, the miniaturized portable cerebral oximeter BRS-1 has the potential to become a valuable tool for monitoring and managing cerebral oxygenation in a variety of clinical applications.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 4214080), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31571003, U1636121, 82027802, and 82102220), the Key Programs of Science and Technology Commission Foundation of Beijing (Grant No. Z181100003818004), the R&D Program of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KM202011232008), the General projects of Scientific and technological Plan of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (Grant Nos. 1202080880, KM202010025023), and the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 61975017).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Juanning Si and Ming Li contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Ruquan Han, Email: ruquan.han@ccmu.edu.cn.

Xunming Ji, Email: jixm@ccmu.edu.cn.

Tianzi Jiang, Email: jiangtz@nlpr.ia.ac.cn.

References

- Andreone BJ, Lacoste B, Gu C. Neuronal and vascular interactions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:25–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-033835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenes R, García-Pérez ML, Bilotta F. Intraoperative monitoring of cerebral oximetry and depth of anaesthesia during neuroanesthesia procedures. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2016;29(5):576. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benni PB, et al. A validation method for near-infrared spectroscopy based tissue oximeters for cerebral and somatic tissue oxygen saturation measurements. J Clin Monit Comput. 2018;32(2):269–284. doi: 10.1007/s10877-017-0015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan PJW. Should cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy be standard of care in adult cardiac surgery? Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24(6):544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B, Aneman A. A prospective, observational study of cerebrovascular autoregulation and its association with delirium following cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(1):33–44. doi: 10.1111/anae.14457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M, Quaresima V. A brief review on the history of human functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) development and fields of application. Neuroimage. 2012;63(2):921–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M, Mottola L, Quaresima V. Principles, techniques, and limitations of near infrared spectroscopy. Can J Appl Physiol. 2004;29(4):463–487. doi: 10.1139/h04-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Elwell C, Smith M. Review article: cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy in adults: a work in progress. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(6):1373–1383. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31826dd6a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AJ, et al. Optimal placement of cerebral oximeter monitors to avoid the frontal sinus as determined by computed tomography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;30(1):127–133. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen ML, et al. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy monitoring versus treatment as usual for extremely preterm infants: a protocol for the SafeBoosC randomised clinical phase III trial. Trials. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori D, et al. Cerebral autoregulation monitoring with ultrasound-tagged near-infrared spectroscopy in cardiac surgery patients. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(5):1187–1193. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobsis FF. Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science. 1977;198(4323):1264–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.929199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis L, Herman P, Eke A. The modified Beer–Lambert law revisited. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51(5):N91–N98. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/5/N02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacsova Z, et al. Investigation of confounding factors in measuring tissue saturation with NIRS spatially resolved spectroscopy. In: Thews O, LaManna JC, Harrison DK, et al., editors. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. Cham: Springer; 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussman BD, et al. Cerebral oxygen saturation in children with congenital heart disease and chronic hypoxemia. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(1):234–240. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccormick PW, et al. Noninvasive cerebral optical spectroscopy for monitoring cerebral oxygen delivery and hemodynamics. Crit Care Med. 1991;19(1):89–97. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick PW, et al. Regional cerebrovascular oxygen saturation measured by optical spectroscopy in humans. Stroke. 1991;22(5):596–602. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.22.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerman A, Hert SD. Cerebral oximetry: the standard monitor of the future? Current Opin Anesthesiol. 2015;28(6):703. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody DM, Bell M, Challa VR. Features of the cerebral vascular pattern that predict vulnerability to perfusion or oxygenation deficiency: an anatomic study. AJNR. 1990;11(3):431–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidech AM, et al. Monitoring with the somanetics INVOS 5100C after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2008;9(3):326. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottestad W, Kåsin JI, Høiseth LØ. Arterial oxygen saturation, pulse oximetry, and cerebral and tissue oximetry in hypobaric hypoxia. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2018;89(12):1045–1049. doi: 10.3357/AMHP.5173.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichler G, et al. Cerebral regional tissue Oxygen Saturation to Guide Oxygen Delivery in preterm neonates during immediate transition after birth (COSGOD III): an investigator-initiated, randomized, multi-center, multi-national, clinical trial on additional cerebral tissue oxygen saturation monitoring combined with defined treatment guidelines versus standard monitoring and treatment as usual in premature infants during immediate transition: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):178–178. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3258-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinti P, et al. The present and future use of functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) for cognitive neuroscience. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1464(1):5–29. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandroni C, Parnia S, Nolan JP. Cerebral oximetry in cardiac arrest: a potential role but with limitations. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(6):904–906. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05572-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholkmann F, Scherer-Vrana A. Comparison of two NIRS tissue oximeters (Moxy and Nimo) for non-invasive assessment of muscle oxygenation and perfusion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1232:253–259. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-34461-0_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si J, et al. Wearable wireless real-time cerebral oximeter for measuring regional cerebral oxygen saturation. Sci China Inf Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11432-020-2995-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steppan J, Hogue CW. Cerebral and tissue oximetry. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2014;28(4):429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudy R, et al. Differences between central venous and cerebral tissue oxygen saturation in anaesthetised patients with diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19740. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56221-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, et al. Tissue oxygenation monitor using NIR spatially resolved spectroscopy. Proc SPIE. 1999;3597:582–592. doi: 10.1117/12.356862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terakado T, et al. Effectiveness of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRO-200NX, Pulse Mode) for risk management in carotid artery stenting. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:e425–e432. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias (2008) Cerebral oximetry monitoring with near infrared spectroscopy detects alterations in oxygenation before pulse oximetry. J Intensive Care Med 23(6):384–388 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tomlin KL, Neitenbach AM, Borg U. Detection of critical cerebral desaturation thresholds by three regional oximeters during hypoxia: a pilot study in healthy volunteers. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12871-016-0298-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranken NPA, et al. Cerebral oximetry and autoregulation during cardiopulmonary bypass: a review. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2017;49(3):182–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie CK, et al. Integrative regulation of human brain blood flow. J Physiol. 2014;592(5):841–859. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]