Abstract

Objectives:

To determine whether radiomics data can predict local tumor progression (LTP) following radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of colorectal cancer (CRC) lung metastases on the first revaluation chest CT.

Methods:

This case–control single-center retrospective study included 95 distinct lung metastases treated by RFA (in 39 patients, median age: 63.1 years) with a contrast-enhanced CT-scan performed 3 months after RFA. Forty-eight radiomics features (RFs) were extracted from the 3D-segmentation of the ablation zone. Several supervised machine-learning algorithms were trained in 10-fold cross-validation on reproducible RFs to predict LTP, with/without denoising CT-scans. An unsupervised classification based on reproducible RFs was built with k-means algorithm.

Results:

There were 20/95 (26.7%) relapses within a median delay of 10 months. The best model was a stepwise logistic regression on raw CT-scans. Its cross-validated performances were: AUROC = 0.72 (0.58–0.86), area under the Precision-Recall curve (AUPRC) = 0.44. Cross-validated balanced-accuracy, sensitivity and specificity were 0.59, 0.25 and 0.93, respectively, using p = 0.5 to dichotomize the model predicted probabilities (vs 0.71, 0.70 and 0.72, respectively using p = 0.188 according to Youden index). The unsupervised approach identified two clusters, which were not associated with LTP (p = 0.8211) but with the occurrence of per-RFA intra-alveolar hemorrhage, post-RFA cavitations and fistulizations (p = 0.0150).

Conclusion:

Predictive models using RFs from the post-RFA ablation zone on the first revaluation CT-scan of CRC lung metastases seemed moderately informative regarding the occurrence of LTP.

Advances in knowledge:

Radiomics approach on interventional radiology data is feasible. However, patterns of heterogeneity detected with RFs on early re-evaluation CT-scans seem biased by different healing processes following benign RFA complications.

Introduction

Local treatments for lung metastases of colorectal cancers (CRCs) are proposed for oligometastatic and more advanced stages, in patients with good response to systemic treatment. 1,2

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a percutaneous thermoablative technique that has shown good tolerance and local control rates, comparable to surgery. However, proof of complete ablation cannot be obtained with RFA because there is no surgical specimen. Consequently, radiological follow-up is necessary to detect local tumor progression (LTP) as soon as possible. Retrospective studies have shown that recurrences are generally detected between 7 and 10 months after RFA. 3–5

Prior studies have investigated potential biomarkers of LTP with moderate results. Abtin et al have suggested that an average contrast enhancement above 15 HU or an increase in contrast uptake higher than before RFA could be considered as local recurrence. 6,7 However, such characteristics can be seen at 3 months post-RFA due to the recovery of microcirculation. 7 With specificity of 62%, 18F-fluodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography CT (18F-FDG PET/CT) performed 3 months after RFA did not successfully predict local recurrence, mostly because of persistent local inflammation difficult to distinguish from residual disease. 8 In a pilot study, lung MRI performed 3 days after RFA suggested that the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) was significantly higher in patients with LTP. 9 However, the results have not been validated in a larger cohort.

Radiomics approaches consist in the extensive quantification of the imaging phenotype, through mathematical processing of medical imaging including shape and textural analyses of tumors imaged via any modality. Radiomics approaches have been shown to help improve the characterization of lung nodules. 10–12 Recently, radiomics analysis on CT-scan after stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) of lung tumors improved the detection of recurrence of non-small cell lung cancers within 3–5 months after treatment compared with classical radiological analysis. 13–15

Thus, we hypothesized that a radiomics analysis of the ablation zone on the first revaluation contrast-enhanced chest CT-scan (CT1) may capture distinct patterns that could correlate with residual disease and/or early LTP following RFA of CRC lung metastases.

Methods

Study design

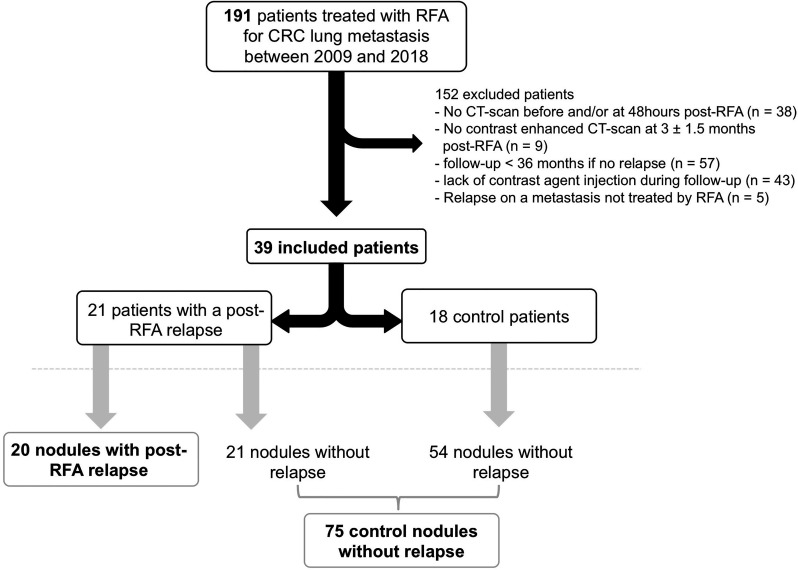

This single-center observational study was approved by our institutional review board. Informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature. We included all consecutive adult patients entered in our institutional imaging database between 2009 and 2018 if they met the following criteria: histologically proven CRC, at least one lung metastasis, treated with RFA after approval by the multidisciplinary board at our regional comprehensive cancer center, chest CT-scan with a contrast agent injection within 3 months before RFA available, RFA performed at our institution (Institut Bergonié, Bordeaux, France), chest CT-scan at 48 h post-RFA available, available CT1 with a contrast-agent injection within 1.5–4.5 months following RFA, clinical–radiological follow-up with CT-scans, and at least 36 months of follow-up in the absence of post-RFA LTP. Figure 1 shows the study flowchart. Radiological follow-up consisted in an early revaluation chest CT-scan at about 3 months, 6 months and then every 6 months.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study. CRC, colorectal cancer; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

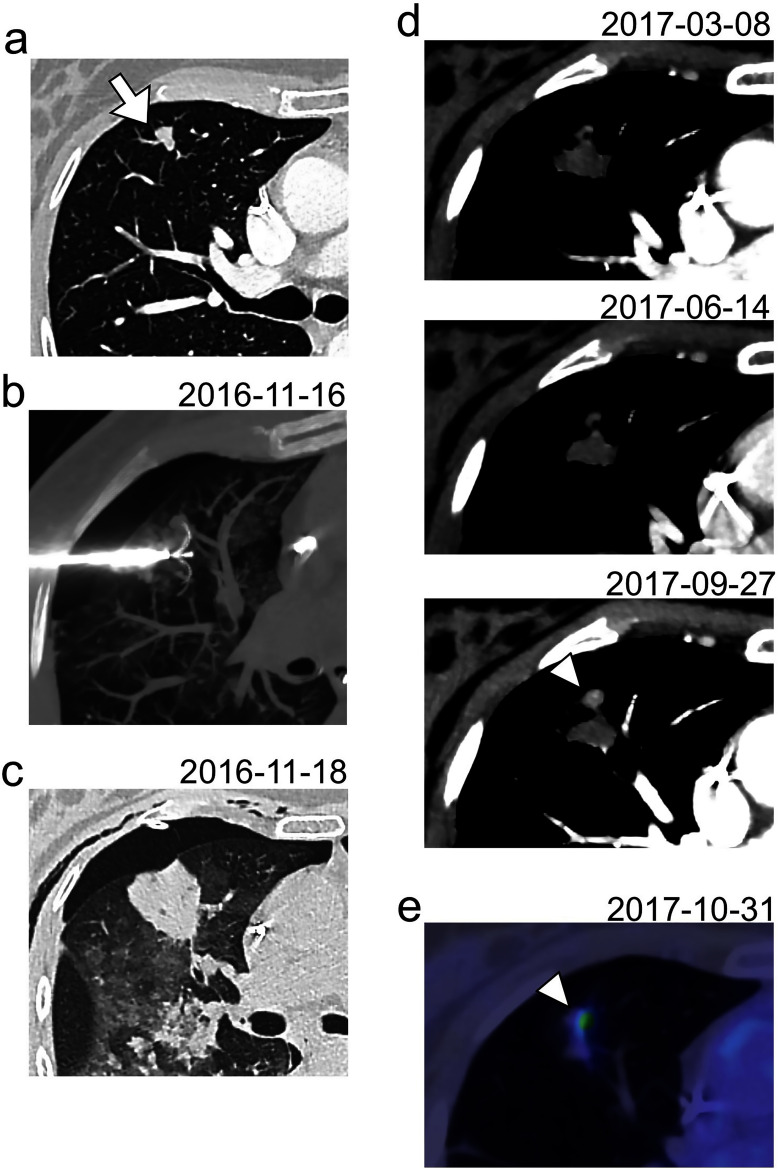

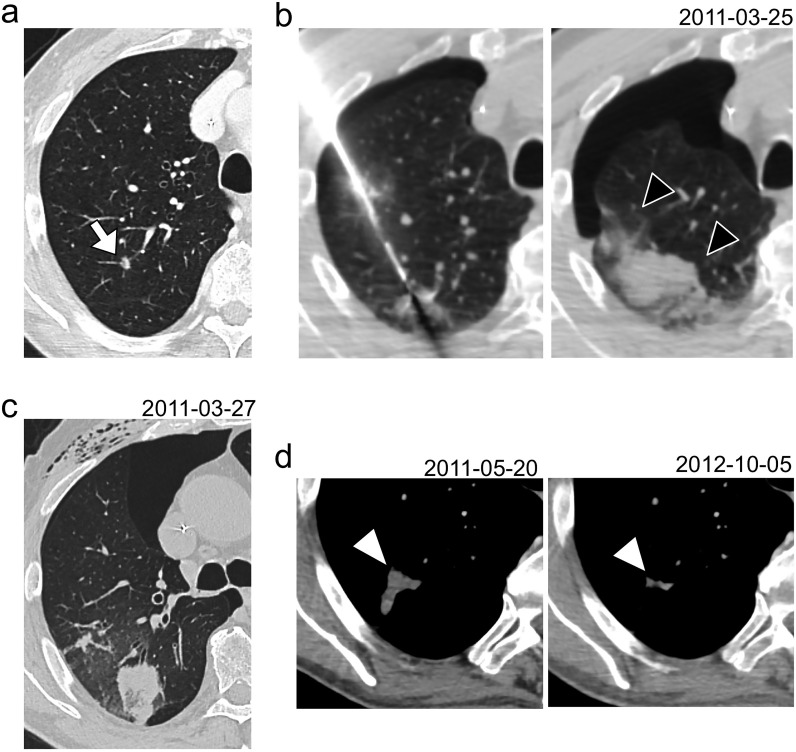

Post-RFA LTP was diagnosed as an unequivocal increase in size, nodular aspect and contrast enhancement of the ablation zone on continuous CT-scans (Figure 2). These LTPs were all reviewed in consensus by two radiologists blinded to clinical data: one fellow (R.M. with 4.5 years of experience in CT-scan, including 6 months in our cancer center) and one senior (A.C.). The differences (in months) between the dates of LTP in routine care and during the retrospective review were calculated.

Figure 2.

Diagnosis of a post-RFA LTP. (a) A lung metastasis of 10 mm was diagnosed in the anterior segment of the upper right lobe of a 56-year-old female, 3 years after the initial management of a pT4N1M1R0 colorectal cancer (white arrow). (b) A RFA was performed with an expandable electrode with a diameter array of 30 mm. The nodule was included within the early ablation zone on the early control CT-scan acquired 48 h after the procedure (c). A LTP was diagnosed 10 months later (white arrowhead) as a nodular enlargement with a contrast-enhancement at the anterior part of the ablation zone (d). This LTP was also confirmed with an 18F-fluodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (e). LTP, local tumor progression; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

We allowed the inclusion of patients with multiple nodules and analyzed each nodule individually. Thus, the following clinical data per nodule were reported: other lung metastases previously or concomitantly treated with RFA, systemic treatment, number of concomitant RFAs, and bilateral RFAs (in two sessions).

Radiofrequency ablation procedure

RFA procedures were performed percutaneously according to a standard procedure by three senior interventional radiologists (J.P., X.B., and V.C.) under general anesthesia. The radiofrequency electrodes were expandable (LeVeen CoAccess needle; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) or straight internally cooled-tip (Cool Tip; Medtronic).

Radiological analysis

The two radiologists reported in consensus the following data from the three CT-scans (pre-RFA CT-scan, the early control chest CT-scan at 48 h and the CT1): nodule initial longest diameter, RFA location, occurrence of immediate pneumothorax and/or at 48 h, significant intra-alveolar hemorrhage (IAH) during the procedure, bronchial or pleural fistulization at 48 h and/or on CT1, cavitation at the RFA site on CT1, and longest diameter and thickness of the ablation zone on CT1. Moreover, radiologists reported if new metastases were seen on CT1. Based on their reading, a new variable, named ‘complicated RFA’, was defined as positive if the RFA was complicated by IAH, or bronchial–pleural fistulization at 48 h or on CT1, or cavitation on CT1.

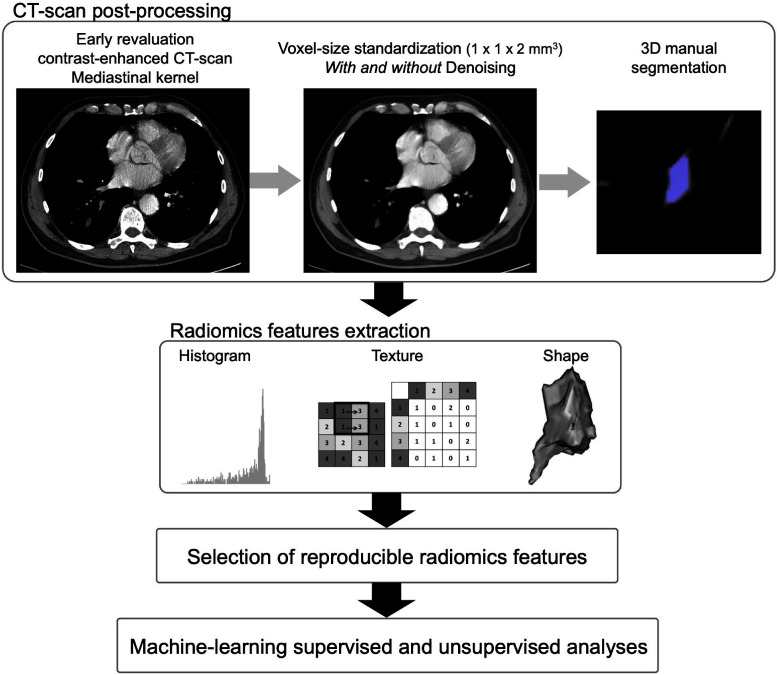

Radiomics processing (Figure 3)

First, we post-processed the CT-scans to homogenize the data set, which was achieved with R (v. 4.1.0, Vienna, Austria,) by using the “dcm2niir”, “ANTsR”, “ANTsRCore” and “extranstr” packages (Figure 3 16 ). CT scans were converted to the nifti format, which is an open source format that facilitates medical image operation. Voxel size was standardized to a common spatial resolution of 1 × 1 × 2 mm3 by using b-spline interpolator. B-spline was chosen because it has already contributed to encouraging results in prior sarcoma radiomics studies, provides good compromise between signal-to-noise ratio and computational time, and may be less prone to high-frequency attenuations than linear interpolation, as well as to blurring, shuffling, aliasing or edge halos that can be encountered with nearest neighbor interpolation. 17–22 CT scans were also slightly denoised for Gaussian noise by using a spatially adaptive filter, which provided two paired data sets: denoised (DN) and raw/not-denoised (NDN) in order to investigate if denoising would improve the predictive models. 23 The parameters of the denoising algorithms were consensually set to: shrinkFactor = 1, patch radius = 1 and search radius = 3, so they would preserve the texture of tissues according to the radiologists’ eyes.

Figure 3.

Radiomics pipeline. 3D, three-dimensional.

Second, ablation zones on DN CT1s were manually 3D-segmented by a radiologist (R.M.). A second senior radiologist (A.C.) validated all the volume-of-interests (VOIs). These VOIs were also propagated on the NDN CT1s. The segmentations were performed with LIFEx freeware (v. 7.0.0), which enabled the extraction of 48 radiomics features (RFs) quantifying the shape of the ablation zones (n = 3), histogram of the radiodensities within the ablation zone (n = 13) and its texture (from the gray-level co-occurrence matrix with a distance of 2 voxels [GLCM, n = 7], gray-level run length matrix [GLRLM, n = 11], neighborhood gray-level different matrix [NGLDM, n = 3], and gray-level zone length matrix [GLZLM, n = 11]). 24 Of note, RFs calculated in LIFEx conform the recommendations of the International Imaging Biomarker Standardization consortium. 25,26 After reviewing the histogram of densities of the ablation zone, the absolute binsize was set to 5 HU. Furthermore, 30 DN and 30 NDN CT1s were randomly selected, with a same proportion of LTP as in the whole population, and segmented twice according to same method in order to estimate the reproducibility of the RFs across multiple segmentations per intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with the following arguments: two-way mixed-effects model with average measures and absolute agreement. We only selected RFs with an ICC>0.85 for the analysis (n = 33/48 [69%] for the DN data set and 37/48 [77%] for the NDN data set). Supplementary Data 1 provides the list of all extracted RFs and their intersegmentation ICC for the DN and NDN data sets. Supplementary Data 2 and 3 shows the Bland–Altman plots for these two sets of reproducible RFs and the limits of agreements with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). 27 Details and mathematical formulas of the RFs can be found at https://www.lifexsoft.org/index.php/resources/19-texture/radiomic-features?filter_tag[0]=.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted with R (v. 4.1.0) using the “caret” package. 28 All tests were two-tailed. A p-value <0.05 was deemed significant.

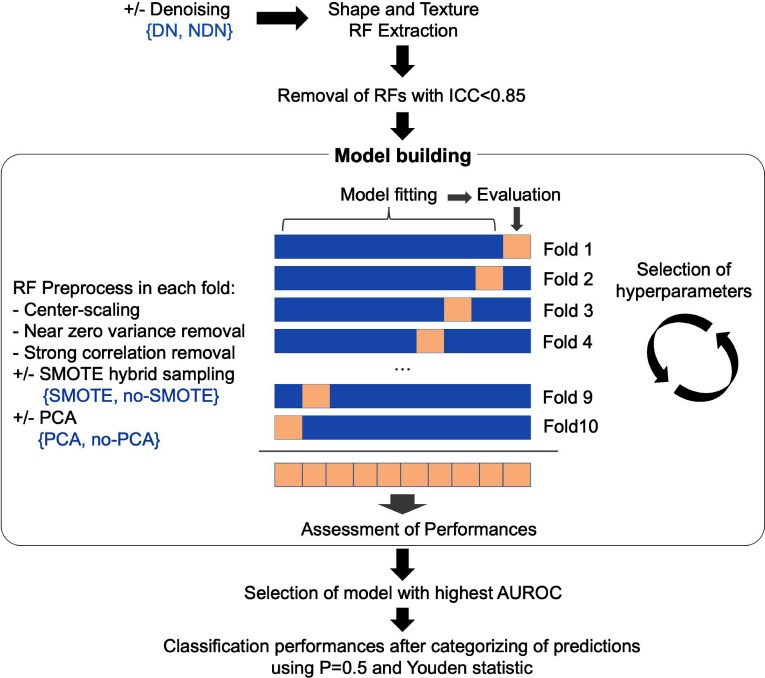

Supervised analysis. Four popular machine-learning algorithms for classification were used to develop models to predict local control at the RFA site based on the reproducible RFs from the DN and NDN data sets, namely: random forests, k-nearest neighbors (kNN), stepwise (backward-forward) logistic regression (StepLR) and radial support vector machine (SVM). 29–31 Brief explanations of the principle of each algorithm is given in Supplementary Data 4). Because of the small size of the cohort, we trained the models in 10-fold stratified cross-validation. 31 Moreover, due to the imbalance nature of the outcome, we developed the models with and without using the hybrid sampling method named synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE), which downsamples the majority class (i.e. no LTP) and synthesizes new data points in the minority class (i.e. occurrence of LTP). 32 It should be noted that the RFs were systematically pre-processed within the cross-validation steps as follows: they were centered and scaled, those with near zero-variance and high correlations (>0.9) were removed. The interest of using dimensionality reduction with principal component analysis (PCA) was also investigated. The hyperparameters of the algorithms were optimized by using exhaustive grid searches (Supplementary Data 4 also shows the tuning grids provided to each algorithm). The area under the ROC curve (AUROC), which was estimated on the unseen data of the cross-validation schemes, was defined as the main performance measure to identify the best model. Definitions for other performance measures (i.e. sensitivity [or recall], specificity, positive-predictive value [PPV, or precision], negative-predictive value [PPV], accuracy, balanced accuracy, Matthews correlation coefficient [MCC], area under the precision-recall curve [AUPRC], F-measure), which were estimated on the best models from the DN and NDN data sets, can be found in Table 1. 33 These measures were estimated using p = 0.5 or the Youden statistics to categorize the predictions in “no relapse” (prediction<P) and ‘local relapse (prediction≥P). 34

Table 1.

Summary of the metrics used to evaluate the performances of the classification models

| Name | Formula | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Proportion of the observations that were correctly classified by the algorithm. | |

| AUPRC* | - | Area Under the Precision (or PPV on y-axis) - Recall (or sensitivity on x-axis) Curve |

| AUROC | - | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve (i.e., true positive rate or sensitivity on x-axis, and false positive rate or 1 – specificity on y-axis). |

| Balanced accuracy* | ||

| F-measure* | ||

| MCC* | Matthews correlation coefficient | |

| NPV | Negative-predictive value | |

| PPV | Positive-predictive value (or precision) | |

| Sensitivity | True-positive rate (or recall) | |

| Specificity | True-negative rate |

FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

*: The performance metrics should be more appropriate for imbalanced data set.

Figure 4 represents the machine-learning pipeline and its tested options.

Figure 4.

Machine-learning pipeline. The algorithms used in the model building were the stepwise logistic regression, the random forests, the radial support vector machine and the k-nearest neighbors, which were trained in 10-fold cross-validation. The other options in the development of the best model to predict post-radiofrequency local relapse (in blue) were: the use of a DN algorithm during the CT-scan pre-processing or not (NDN), the use of SMOTE to artificially increase the under-represented group of patients with local relapse, and the use of PCA for dimensionality reduction during the RFs preprocessing. AUROC, area under the ROC curve; DN, denoising; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; PCA, principle component analysis; RF, radiomics feature; SMOTE, synthetic minority oversampling technique.

Unsupervised analysis. We applied the k-means clustering method (with 1000 iterations and 50 random seeds) on the reproducible center-scaled RFs coming from the DN and NDN data sets. 35 The number of clusters was determined as the one maximizing the average silhouette width. The associations between the resulting clusters and (i) LTP, and (ii) complicated RFA were tested with χ2 tests.

Results

Patient and radiofrequency ablation characteristics (Table 2)

Thirty-nine patients (median age: 63.1 years) with 95 lung metastases were treated during 67 distinct sessions. RFA was performed after chemotherapy in 52/95 (54.7%) cases (Table 2). Other metastases were diagnosed in liver and lymph nodes in 20/95 (21.1%) and 3/95 (3.2%) cases, respectively. The average size of the lung metastases treated with RFA was 9.3 ± 5.2 mm. Thirty-three out of the 95 (34.7%) nodules showed a central location (i.e. <3 cm to the mediastinum).

Table 2.

Initial characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at initial diagnosis (years) | 60.8 (35.6–78) | |

| Sex | ||

| Males | 17/39 (43.6) | |

| Females | 22/39 (56.4) | |

| Initial tumor location | ||

| Rectum | 14/39 (35.9) | |

| Sigmoid/left colon | 20/39 (51.3) | |

| Transverse or right colon | 3/39 (7.7) | |

| Caecum | 2/39 (5.1) | |

| Initial tumor mutation status | ||

| K-RAS mutation | 14/30 (46.7) | |

| None | 16/30 (53.3) | |

| Unknown | 9 | |

| Initial surgery | ||

| Yes | 39/39 (100) | |

| Initial chemotherapy | ||

| No | 5/37 (13.5) | |

| Neoadjuvant | 12/37 (32.4) | |

| Adjuvant | 14/37 (37.8) | |

| Neoadjuvant & adjuvant | 6/37 (16.2) | |

| Unknown | 2 | |

| Initial radiation therapy | ||

| No | 26/39 (66.7) | |

| Yes | 13/39 (33.3) | |

| Initial metastatic disease (M) | ||

| No | 23/38 (60.5) | |

| Yes | 15/38 (39.5) | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Lymphadenopathy at diagnosis (N) | ||

| No | 2/38 (5.3) | |

| Yes | 36/38 (94.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Initial tumor size (T) | ||

| T2 | 4/34 (11.8) | |

| T3 | 22/34 (64.7) | |

| T4 | 8/34 (23.5) | |

| Unknown | 5 | |

Data are number of patients with percentages in parentheses, except for age (given as median and range).

Regarding tolerance, 70/95 (73/7%) RFAs showed an immediate pneumothorax, which persisted at 48 h for 46/95 (48.4%) cases. No bronchial fistulization was to be deplored but one pleural fistulization was found at 48 h. A significant IAH was diagnosed in 26/95 (27.4%) of procedures. A cavitation was noticed for 6/95 (6.3%) cases on CT1. Thus, 31/95 (32.6%) complicated RFAs were identified.

In total, 20/95 (26.7%) LTP after RFA were diagnosed, at the third follow-up CT-scan on average (range: 1–8), which corresponded to a median delay of 10 months since RFA (range: 2.4–37). The median follow-up for non-relapsing RFA was 65 months (range: 36–127).

Supervised analysis

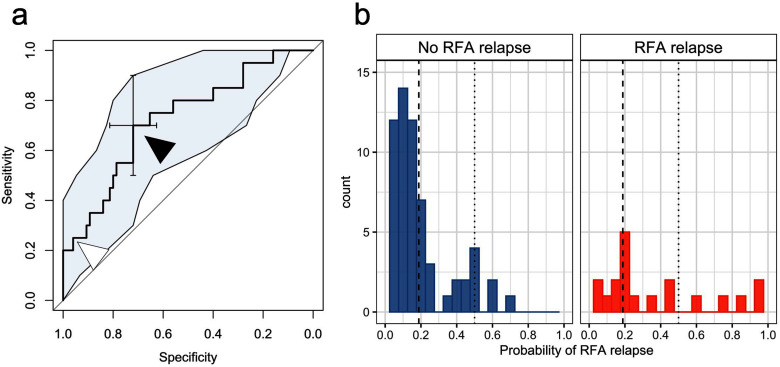

The characteristics of the best performing model were: StepLR algorithm trained on RFs from NDN CT1s, without using PCA or SMOTE. This model provided the highest AUROC and AUPRC in cross-validation, namely: 0.720 (95%CI = 0.597–0.852) and 0.440, respectively (Figure 5.a). The AUROC, AUPRC and balanced accuracy of the other models are given in Supplementary Data 5, which also includes the times needed to train each model and make a prediction.

Figure 5.

Results of the best supervised stepwise logistic regression model to predict a post-RFA LTP based on the radiomics features of the ablation zone at early revaluation CT1. This model provided a cross-validated probability for an LTP to each lung metastasis treated by RFA. (a) The cross-validated area under ROC curves was of 0.720. The optimal cut-off (for a probability of 0.188) is indicated with a black arrowhead. The standard cut-off. (0.5) is indicated with a white arrowhead. (b) Shows the distribution of the probabilities in the two groups of ablation zones (no RFA LTP vs RFA LTP). The dotted line indicates the standard cut-off of 0.5 (i.e. if the probability is >0.5, the nodule is likely to develop LTP), while the dashed line indicates an optimal cut-off of 0.188 (i.e. if the probability is >0.188, the nodule is likely to develop LTP). LTP, local tumor progression; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

The best model provided cross-validated probabilities of LTP for each lung metastasis (Figure 5.b). These probabilities were further dichotomized by using a cut-off of 0.5 and 0.188 according to the Youden method. The performances of this classifier using these two cut-offs are shown in Table 3. Its parameters are displayed in Table 4. After the RFs pre-processing (which excluded 18 correlated and/or near zero variance RFs), this model was trained on 20 RFs and selected 8 of them of which 4 were independent predictors of local relapse, namely: CONVENTIONAL_Skewness (p = 0.0012), HISTO_Energy (p = 0.0394), NGLDM_Busyness (p = 0.0012) and GLZLM_SZE (p = 0.0036).

Table 3.

Performances of the best model (stepwise logistic regression on the raw data set, without dimensionality reduction and without synthetic minority oversampling technique)

| Performance measures | Final model | |

|---|---|---|

| Standard cut-off (0.5) | Youden cut-off (0.188) | |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | 0.25 (0.11–0.47) | 0.70 (0.48–0.85) |

| Specificity | 0.93 (0.85–0.97) | 0.72 (0.61–0.81) |

| MCC | 0.24 | 0.36 |

| NPV | 0.82 (0.73–0.89) | 0.91 (0.80–0.95) |

| PPV (Precision) | 0.50 (0.24–0.76) | 0.40 (0.26–0.56) |

| Accuracy | 0.79 (0.69–0.87) | 0.72 (0.61–0.80) |

| Balanced accuracy | 0.59 | 0.71 |

| F-measure | 0.33 | 0.51 |

| True positive | 5 | 14 |

| False positive | 5 | 21 |

| True negative | 70 | 54 |

| False negative | 15 | 6 |

| AUROC | 0.720 (0.597–0.852) | |

| AUPRC | 0.440 | |

AUPRC, area under the precision-recall curve; AUROC, area under the ROC curve; MCC, Matthews correlation coefficient; NPV, negative-predictive value; PPV, positive-predictive value.

NOTE. Results are given with 95% confidence intervals where appropriate.

Table 4.

Coefficients of the best model (stepwise logistic regression on the raw data set, without dimensionality reduction and without synthetic minority oversampling technique)

| Coefficients | Estimate | Standard error | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONVENTIONAL_Skewness | −4.12 (-7.31 – -1.95) | 1.27 | 0.0012** |

| HISTO_Energy | −2.37 (-4.89 – -0.41) | 1.15 | 0.0394* |

| GLCM_Entropy_log2 | −0.73 (-1.71 – 0.21) | 0.48 | 0.12671 |

| GLRLM_SRLGE | −56.64 (-144.65 – -11.31) | 38.40 | 0.1401 |

| NGLDM_Busyness | 2.75 (1.31–4.68) | 0.85 | 0.0012** |

| GLZLM_SZE | 3.16 (1.32–5.70) | 1.08 | 0.0036** |

| GLZLM_SZLGE | 18.18 (4.24–46.12) | 12.12 | 0.1334 |

| GLZLM_LZLGE | −1.88 (-4.45 – -0.11) | 1.11 | 0.0885 |

| (Intercept) | −7.62 (-16.79 – -3.33) | 3.99 | 0.0560 |

NOTE. Estimate are given with 95% confidence interval.

* : p < 0.05, ** : p < 0.005, *** : p < 0.001. Significant results are highlighted in bold.

Unsupervised analysis

Regarding the k-means clustering, a largest silhouette width of 0.900 for the NDN data set (0.340 for the DN data set) was reached with two clusters (Supplementary Data 6). Therefore, two clustering classifications (named cluster-1-DN [or NDN] or cluster-2-DN [or NDN]) were attributed to each of the 95 observations. The most important radiomics features for the clusterings are ranked in Supplementary Data 7.

Regarding the 52 ablation zones classified in cluster-1-NDN, 10/52 (19.2%) showed LTP. 43 ablation zones belonged to cluster-2-NDN, of which 10 showed LTP (10/43 [23.3%]). No association was found between the NDN clustering classification and LTP (p = 0.8211).

Twenty-three out of the 52 (44.2%) ablation zones classified in cluster-1-NDN corresponded to complicated RFA vs 8/43 (18.6%) ablation zones in cluster-2-NDN, which led to a significant association between complicated RFA and the NDN clustering classification (p = 0.0150 Supplementary Data 8). Similar results were found with the denoised data set (no association with LTP [p = 0.9673] but with complicated RFA [p = 0.0179]). An example is given in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Example of a complicated RFA that was classified in cluster-1-DN and -NDN. Six months after the initial management of a pT4aN3M1R0 colorectal cancer, a 68-year-old male presented a lung metastasis of 9 mm in the upper right lobe (white arrow) (a). This metastasis was treated by RFA with an expandable electrode with a diameter array of 30 mm (b) but the procedure was complicated by the occurrence of segmental intra-alveolar hemorrhage during the removal of the electrode (black arrowheads)—as well as by a pneumothorax. The control CT-scan performed 48 h later showed a residual surrounding hemorrhage and a dense ablation zone (c) with few ground-glass opacity within the peripheral halo. (d) On early revaluation CT-scan (CT1), the post-RFA ablation zone was rather nodular and heterogeneous but it progressively decreased and retracted (e). Three and a half years after RFA, the patient did not show local tumor progression at the RFA location. DN, denoised; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

Discussion

In this study, we have used supervised and unsupervised machine-learning approaches on radiomics data of the ablation zone on CT1 to identify radiomics patterns correlating with incomplete RFA or early LTP. Although performing significantly better than a random model, our best supervised model demonstrated moderate diagnostic performances, even after optimizing the probability cut-off. Through non-supervised clustering, we explained these limited performances by the fact that radiomics data also captured inflammation and/or resumption of IAH, cavitation and fistulization occurring during and early after complicated procedures in addition to residual tumor and incomplete RFA.

Being able to detect residual disease following incomplete procedures would be helpful to personalize radiological follow-up and to complete treatment earlier. We trained four popular machine-learning algorithms for this classification task and found that the simplest one, StepLR, with the least complex imaging and RF pre-processing, provided the highest diagnostic performances. Indeed, denoising the CT-scans, even with a spatially adaptive filter and quality control performed by senior radiologists, seemed to reduce the information together with the noise reduction. 23 This finding does not mean that denoising should be systematically banned from radiomics analyses but that alternative denoising algorithms should be attempted and their outputs should be compared with those of raw data. 10 Furthermore, the final StepLR model did not select SMOTE and PCA pre-processing. SMOTE is a popular method to generate new synthetic samples for imbalanced data set, which generally outperformed under- and (random) oversampling, especially for high-dimensional data. 32 It should be noted that: (i) for some trained models, using PCA and SMOTE increased the performances (for instance for KNN, StepLR and SVM in the DN data set, and random forests in the NDN data set), and (ii) other advanced sampling techniques could have been investigated, such as SMOTE variants and adatative synthetic sampling approach—though it was not the aim of our study. 36 Class imbalance is also problematic in terms of performance evaluation. 33 To address this issue, we proposed various metrics that mostly converged towards the selection of the final StepLR model. Indeed, the AUPRC was also the highest (0.44) and higher than the AUPRC of a random model for our cohort (0.21); the balanced accuracy was the third highest among all the models (0.59 for standard cut-off and 0.72 for optimized cut-off). However, the final StepLR model was far from perfect. Indeed, using the standard cut-off provided 5 false positives and 15 false negatives, while using the optimized cut-off provided 21 false positives and 6 false negatives. On a translational point of view, these false positives would be at risk of undergoing useless additional RFA to complete the procedure and CT-scans for follow-up. Conversely, these false negatives would be at risk of insufficient follow-up and missing local relapse. Furthermore, these performances may be slightly overestimated because we did not use an external validation cohort to see how well the model would generalize (although these performances were estimated on the unseen observations during the cross-validation—which is less at risk of overfitting than no partitioning or unique training/testing partitioning). 31 Overall, on a clinical aspect, we believe that these current performances are too limited to enable decision-making. Nevertheless, as implementation of machine-learning and radiomics in interventional radiology is a growing field of research, we believe that our StepLR model could be used to benchmark future models. 37–41

The results of the unsupervised analysis could explain the intermediate performances. Indeed, clusters based on DN and NDN RFs were both significantly associated with complicated RFA. Thus, we hypothesize that RFs also captured the local inflammation, which appears proportional to post-RFA complications. Indeed, subacute and chronic phases after RFA (>10 days) consist in the resumption of the inner and intermediate necrotic zones and thickening of the peripheral rim. Histologically, this corresponds to granulation tissue with inflammatory cells and then to a fibrous scar that slowly decreases with the healing process. Bonichon et al were confronted with the same limit with 18F-FDG/PET-CT. 8 The authors found a high number of false positives and a low specificity at 3 months because this technique was not able to distinguish residual cancerous cells from inflammatory cells, both with 18F-FDG high avidity. Although methodologies were different, we found a lower rate of misclassification errors with CT1-based radiomics compared with 18F-FDG/PET-CT (21.1–28.4% vs 66%, respectively). Interestingly, similar performances were obtained with radiomics in the study by Mattonnen et al (AUROC = 0.70–0.73), but the authors investigated SBRT and primary lung cancers at distinct time points, and post-radiation lung injury is physiopathologically distinct from post-RFA lung healing. 15,42

The mixed results of our study also illustrate that radiomics does not systematically produce conclusive models despite a methodology trying to follow recommendations. 26,43,44 Additionally, our results, together with those of Bonichon et al and Mattonnen et al illustrate that using only early re-evaluation morphological or functional imaging is not enough due to co-occurrences of different phenomena with similar radiological aspects (i.e. residual tumor and incomplete procedures, and inflammation and healing processes). Future research directions could include the assessment of non-pulmonary metastatic diseases, clinical, radiological and radiomics features from the primitive tumor and lung metastases, and biological variables (for instance circulating tumor DNA).

Our study has limitations. First, we used a case–control retrospective cohort in order to reach a sufficient percentage of events but this study design did not enable estimation of the real prevalence of LTP, and consequently, negative- and positive-predictive values of the models. Second, we did not validate our models on an external test data set. To our knowledge, there is no multicenters database dedicated to interventional radiology imaging, although via either The Cancer Imaging Atlas or the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe task force, their development would be useful to standardize practice, data collection and more powerful collaborative studies. Third, our study population was relatively small in terms of patients but all were homogeneously treated and followed for at least 36 months in our center. Fourth, confirmatory biopsies were almost never performed on a routine basis for initial diagnosis or local recurrence diagnosis of the lung nodules, but those included appeared unequivocally and the pathological morphological changes in the ablation zones were validated by three radiologists (one during clinical practice and two during the second reading).

Conclusion

The intermediate performances of our best radiomics model (with AUROC = 0.72, AUPRC = 0.44, false-positive rate = 0.07–0.28 and false-negative rate = 0.30–0.75, depending on the cut-off for the predicted probabilities) currently limit the clinical interest of radiomics approach to predict LTP following RFA of lung metastases of CRC using early re-evaluation CT-scan. Similarly to conventional radiological analysis and 18F-FDG-PET/CT, the early patterns of heterogeneity detected with radiomics appeared biased and noised by different healing processes following benign complications of the RFA, indicating the need for enriching predictive models with additional pre- and post-RFA clinical, pathological and imaging.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Mrs Pippa McKelvie-Sebileau for medical writing services.

Conflicts of interest: J.P. has participated in workshops for Boston Scientific. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Amandine Crombé, Email: crombeamandine2@gmail.com.

Jean Palussière, Email: j.palussiere@bordeaux.unicancer.fr.

Vittorio Catena, Email: v.catena@bordeaux.unicancer.fr.

Maxime Cazayus, Email: m.cazayus@bordeaux.unicancer.fr.

Marianne Fonck, Email: m.fonck@bordeaux.unicancer.fr.

Dominique Béchade, Email: d.bechade@bordeaux.unicancer.fr.

Xavier Buy, Email: x.buy@bordeaux.unicancer.fr.

Romane Markich, Email: romane.markich@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fonck M, Perez J-T, Catena V, Becouarn Y, Cany L, Brudieux E, et al. Pulmonary thermal ablation enables long chemotherapy-free survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2018; 41: 1727–34. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-1939-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 1386–1422. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hiraki T, Sakurai J, Tsuda T, Gobara H, Sano Y, Mukai T, et al. Risk factors for local progression after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of lung tumors: evaluation based on a preliminary review of 342 tumors. Cancer 2006; 107: 2873–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson EM, Lees WR, Gillams AR. Early indicators of treatment success after percutaneous radiofrequency of pulmonary tumors. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2009; 32: 478–83. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9482-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palussière J, Marcet B, Descat E, Deschamps F, Rao P, Ravaud A, et al. Lung tumors treated with percutaneous radiofrequency ablation: computed tomography imaging follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2011; 34: 989–97. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-0048-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abtin FG, Eradat J, Gutierrez AJ, Lee C, Fishbein MC, Suh RD. Radiofrequency ablation of lung tumors: imaging features of the postablation zone. Radiographics 2012; 32: 947–69. doi: 10.1148/rg.324105181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suh RD, Wallace AB, Sheehan RE, Heinze SB, Goldin JG. Unresectable pulmonary malignancies: CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation -- preliminary results. Radiology 2003; 229: 821–29. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2293021756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonichon F, Palussière J, Godbert Y, Pulido M, Descat E, Devillers A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT for assessing response to radiofrequency ablation treatment in lung metastases: a multicentre prospective study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2013; 40: 1817–27. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2521-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okuma T, Matsuoka T, Yamamoto A, Hamamoto S, Nakamura K, Inoue Y. Assessment of early treatment response after CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of unresectable lung tumours by diffusion-weighted MRI: a pilot study. Br J Radiol 2009; 82: 989–94. doi: 10.1259/bjr/13217618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen C-H, Chang C-K, Tu C-Y, Liao W-C, Wu B-R, Chou K-T, et al. Radiomic features analysis in computed tomography images of lung nodule classification. PLoS One 2018; 13(): e0192002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferreira Junior JR, Koenigkam-Santos M, Cipriano FEG, Fabro AT, Azevedo-Marques P de. Radiomics-based features for pattern recognition of lung cancer histopathology and metastases. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2018; 159: 23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beig N, Khorrami M, Alilou M, Prasanna P, Braman N, Orooji M, et al. Perinodular and intranodular radiomic features on lung CT images distinguish adenocarcinomas from granulomas. Radiology 2019; 290: 783–92. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mattonen SA, Palma DA, Haasbeek CJA, Senan S, Ward AD. Early prediction of tumor recurrence based on CT texture changes after stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) for lung cancer. Med Phys 2014; 41(): 033502. doi: 10.1118/1.4866219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li Q, Kim J, Balagurunathan Y, Qi J, Liu Y, Latifi K, et al. CT imaging features associated with recurrence in non-small cell lung cancer patients after stereotactic body radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol 2017; 12(): 158. doi: 10.1186/s13014-017-0892-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mattonen SA, Palma DA, Johnson C, Louie AV, Landis M, Rodrigues G, et al. Detection of local cancer recurrence after stereotactic ablative radiation therapy for lung cancer: physician performance versus radiomic assessment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016; 94: 1121–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.12.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muschelli J, Gherman A, Fortin J-P, Avants B, Whitcher B, Clayden JD, et al. Neuroconductor: an R platform for medical imaging analysis. Biostatistics 2019; 20: 218–39. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxx068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crombé A, Périer C, Kind M, De Senneville BD, Le Loarer F, Italiano A, et al. T2 -based MRI delta-radiomics improve response prediction in soft-tissue sarcomas treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 50: 497–510. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crombé A, Le Loarer F, Sitbon M, Italiano A, Stoeckle E, Buy X, et al. Can radiomics improve the prediction of metastatic relapse of myxoid/round cell liposarcomas? Eur Radiol 2020; 30: 2413–24. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06562-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crombé A, Fadli D, Buy X, Italiano A, Saut O, Kind M. High-Grade soft-tissue sarcomas: can optimizing dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI postprocessing improve prognostic radiomics models? J Magn Reson Imaging 2020; 52: 282–97. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peeken JC, Spraker MB, Knebel C, Dapper H, Pfeiffer D, Devecka M, et al. Tumor grading of soft tissue sarcomas using MRI-based radiomics. EBioMedicine 2019; 48: 332–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thevenaz P, Blu T, Unser M. Image interpolation and resampling. Handb Med Imaging Process Anal Academic Press 2000; 393–420. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lehmann TM, Gönner C, Spitzer K. Survey: interpolation methods in medical image processing. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1999; 18: 1049–75. doi: 10.1109/42.816070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manjón JV, Coupé P, Martí-Bonmatí L, Collins DL, Robles M. Adaptive non-local means denoising of Mr images with spatially varying noise levels. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010; 31: 192–203. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nioche C, Orlhac F, Boughdad S, Reuzé S, Goya-Outi J, Robert C, et al. LIFEx: a freeware for radiomic feature calculation in multimodality imaging to accelerate advances in the characterization of tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res 2018; 78: 4786–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zwanenburg A, Vallières M, Abdalah MA, Aerts HJWL, Andrearczyk V, Apte A, et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology 2020; 295: 328–38. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vallières M, Zwanenburg A, Badic B, Cheze Le Rest C, Visvikis D, Hatt M. Responsible radiomics research for faster clinical translation. J Nucl Med 2018; 59: 189–93. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.200501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martin Bland J, Altman D. STATISTICAL methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The Lancet 1986; 327: 307–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuhn M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J Stat Softw 2008; 28: 1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v028.i05 27774042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Breiman L. Machine Learning 2001; 45: 5–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1010933404324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Samworth RJ. Optimal weighted nearest neighbour classifiers. Ann Statist 2012; 40: 2733–63. doi: 10.1214/12-AOS1049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuhn M, Johnson K. Applied Predictive Modeling. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6849-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Jair 2002; 16: 321–57. doi: 10.1613/jair.953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luque A, Carrasco A, Martín A, de las Heras A. The impact of class imbalance in classification performance metrics based on the binary confusion matrix. Pattern Recognition 2019; 91: 216–31. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2019.02.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. YOUDEN WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950; 3: 32–35. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hartigan JA, Wong MA. Algorithm as 136: a k-means clustering algorithm. Applied Statistics 1979; 28: 100. doi: 10.2307/2346830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amin A, Anwar S, Adnan A, Nawaz M, Howard N, Qadir J, et al. Comparing oversampling techniques to handle the class imbalance problem: a customer churn prediction case study. IEEE Access 2016; 4: 7940–57. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2016.2619719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Markich R, Palussière J, Catena V, Cazayus M, Fonck M, Bechade D, et al. Radiomics complements clinical, radiological, and technical features to assess local control of colorectal cancer lung metastases treated with radiofrequency ablation. Eur Radiol 2021; 31: 8302–14. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-07998-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wen L, Weng S, Yan C, Ye R, Zhu Y, Zhou L, et al. A radiomics nomogram for preoperative prediction of early recurrence of small hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection or radiofrequency ablation. Front Oncol 2021; 11: 657039. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.657039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Horvat N, Araujo-Filho J de AB, Assuncao-Jr AN, Machado FA de M, Sims JA, Rocha CCT, et al. Radiomic analysis of MRI to predict sustained complete response after radiofrequency ablation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma - a pilot study. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2021; 76: e2888. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2021/e2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Staal FCR, Taghavi M, van der Reijd DJ, Gomez FM, Imani F, Klompenhouwer EG, et al. Predicting local tumour progression after ablation for colorectal liver metastases: CT-based radiomics of the ablation zone. Eur J Radiol 2021; 141. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taghavi M, Staal F, Gomez Munoz F, Imani F, Meek DB, Simões R, et al. Ct-Based radiomics analysis before thermal ablation to predict local tumor progression for colorectal liver metastases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2021; 44: 913–20. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02735-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mattonen SA, Tetar S, Palma DA, Louie AV, Senan S, Ward AD. Imaging texture analysis for automated prediction of lung cancer recurrence after stereotactic radiotherapy. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2015; 2(): 041010. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.2.4.041010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, Peerlings J, de Jong EEC, van Timmeren J, et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017; 14: 749–62. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Buvat I, Orlhac F. The dark side of radiomics: on the paramount importance of publishing negative results. J Nucl Med 2019; 60: 1543–44. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.235325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.