Histiocytoses encompass a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by tissue infiltration of cells with morphological and phenotypic features of macrophages or dendritic cells, which have been reclassified into five groups: i) L group - Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH)/Erdheim Chester disease (ECD); ii) C group - cutaneous histiocytoses; iii) M group - malignant histiocytoses; iv) R group - Rosai-Dorfman disease and v) H group - hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).1 Histiocytoses rarely occur during acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treatment, potentially due to trans-differentiation2 or a common progenitor cell,3 and there is no standard treatment in this particular situation. We herein report a case of BRAF-mutated non-LCH arising during T-ALL therapy who responded to dabrafenib and chemotherapy combination.

Our patient was a 7-year-old boy diagnosed in March 2020 with central nervous system (CNS)-positive T-ALL harboring the onco genic STIL-TAL1 fusion. He initially presented with right facial nerve palsy and hyperleukocytosis with an initial white blood cell count at 205x109/L. He received fourdrug induction chemotherapy, achieved morphologic remission with positive end-induction minimal residual disease (MRD) by flow cytometry. He then received postinduction therapy according to Arm D of AALL0434 protocol,4 with a negative flow-based end-consolidation MRD. In October 2020, during delayed intensification (DI), he developed persistent thrombocytopenia refractory to corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulins. Extensive investigation for refractory thrombocytopenia came back negative. However, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed hypermetabolic focal lesions in the mediastinum, 5th right rib and right tibial tuberosity. In December 2020, 7 months from T-ALL diagnosis, biopsy of the rib lesion revealed proliferation of multinucleated giant cells with emperipolesis that were CD68+, CD163+, S100+, fascin+, lysozyme+ and BRAF+, suggestive of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD). Whole-transcriptome analysis of the rib lesion revealed a BRAF V600E mutation and the STIL-TAL1 fusion present at T-ALL diagnosis, suggesting a common clonal origin. Since RDD and T-ALL were clonally-related, leukemia treatment was prioritized and our patient pursued DI and maintenance therapy, including cranial irradiation. A follow-up PET scan in March 2021 showed histiocytosis progression despite ALL-based chemotherapy, which provided the rationale to introduce a BRAF inhibitor. Considering pre-existing transaminitis and thrombocytopenia, ALL maintenance chemotherapy was stopped and dabrafenib monotherapy at 5.25 mg/kg/day was initially started in April 2021, with a rapid metabolic response 1 month post-dabrafenib. In order to pursue T-ALL therapy, low-dose ALL maintenance chemotherapy was combined with dabrafenib in June 2021 and titrated based on patient’s tolerance (monthly vincristine 1.5 mg/m2/dose, prednisone 20 mg/m2/dose twice a day for 5 days every month, daily 6-mercaptopurine 20 mg/m2/dose, weekly methotrexate was omitted because of thrombocytopenia). Combination of dabrafenib and chemotherapy was well-tolerated. Unfortunately, the patient experienced an isolated CNS relapse in September 2021, 17 months from T-ALL diagnosis and 9 months from onset of histiocytosis. Dabrafenib was stopped at the time of relapse to begin ALL reinduction chemotherapy. Of note, thrombocytopenia <50x109/L without clinically active bleeding persisted from October 2020 to September 2021. PET scans prior to relapse showed progressive hypermetabolic uptake in the liver. A liver biopsy was inconclusive for etiology. Relapse was treated with intrathecal chemotherapy and daratumumab, to provide systemic therapy and potentially address his refractory thrombocytopenia,5 followed by two cycles of the NECTAR regimen.6 After a conditioning regimen with VP-16, anti-thymocyte globulin and total body irradiation, he proceeded to a matched-sibling donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in December 2021. At the time of this report, the patient is 7 months post-HSCT without evidence of T-ALL and histiocytosis.

Histiocytoses arising during ALL therapy are exceedingly rare, although they can also occur at diagnosis or following treatment completion. Our case is unique in several ways and expands the paradigm of molecularly-targeted therapies in histiocytic neoplasms. First, we report a rapid metabolic response in BRAF-mutated histiocytic lesions refractory to conventional chemotherapy after only 1 month of dabrafenib monotherapy. Donadieu et al.7 previously reported rapid response within 2 months of vemurafenib in children with BRAF V600E-mutated refractory LCH. Given the co-existence of clonally-related BRAF-mutated RDD and T-ALL, ALL-directed therapy was prioritized prior to histiocytosis treatment. However, since RDD lesions were refractory to conventional chemotherapy, we report the feasibility of combining dabrafenib and lowdose maintenance ALL therapy to treat both diseases simultaneously. Combination of dabrafenib and chemotherapy was well-tolerated, without worsening pre-existing hematologic and hepatic toxicities. Although this combination resulted in a significant metabolic response of RDD lesions, leukemia remission was not durable as patient experienced CNS relapse 3 months following combination therapy. Of note, Gaspari et al.8 also reported the safety and efficacity of vemurafenib combined with vinblastine/prednisone in a newborn with multisystem LCH. A literature review of children with co-diagnosis of histiocytosis (excluding H group disorders) during ALL treatment identified 30 cases. Median age at ALL diagnosis was 6 years old (range, 0.5-18 years) and median time between ALL diagnosis and histiocytosis onset was 7.5 months (range, 3-24 months). Most patients were boys. Leukemia immunophenotype included ten T-ALL. Histiocytic disorders arising during ALL treatment comprises LCH (47%), histiocytic sarcoma (23%), juvenile xanthogranuloma (13%), true histiocytic lymphoma (10%), ErdheimChester disease (ECD) (3%) and indeterminate (3%). Prognosis was poor with 19 deaths (12 related to histiocytosis). Twenty-one patients did not achieve remission of histiocytosis. ALL treatment alone in this context appeared ineffective (remission in 1/5 cases). Four children experienced ALL relapse following diagnosis of histiocytosis, with two dying of ALL progression. The clinical course of our patient is consistent with key findings summarized above. Although the morphologic appearance of our patient’s histiocytic lesions is highly suggestive of RDD, the BRAF V600E mutation is not characteristic of RDD, but rather represents a molecular hallmark of LCH and/or ECD.9 This morphologic/molecular discrepancy is reminiscent of mixed histiocytosis arising as part of malignant hemopathy associated with clonal hematopoiesis previously reported in adults with ECD.10,11 It remains unclear whether co-occurrence of histiocytosis confers a worse prognosis when associated with ALL or vice versa, although our literature review signals a high rate of histiocytosis-related mortality. Recent evidence of MAPK pathway activation in most histiocytic disorders paves the way for molecularly-targeted therapies in combination with conventional chemotherapy, as illustrated in this case, to treat leukemic and histiocytic entities concomitantly. This therapeutic combination strategy warrants further validation; however, prospective assessment of such strategy is unforeseeable due to the rarity of these pathologies. Therefore, our case provides a proofof-concept demonstrating safety of dabrafenib in combination with chemotherapy, and may represent an alternative therapeutic option for BRAF-mutated histiocytosis arising during ALL therapy, either as a definitive treatment or as a bridge to HSCT consolidation, given their poor outcome. Furthermore, since ALL maintenance chemotherapy is similar to LCH-based backbone, future prospective evaluation of BRAF inhibitor in combination with conventional chemotherapy for high-risk BRAF-mutated multisystemic LCH may be warranted.

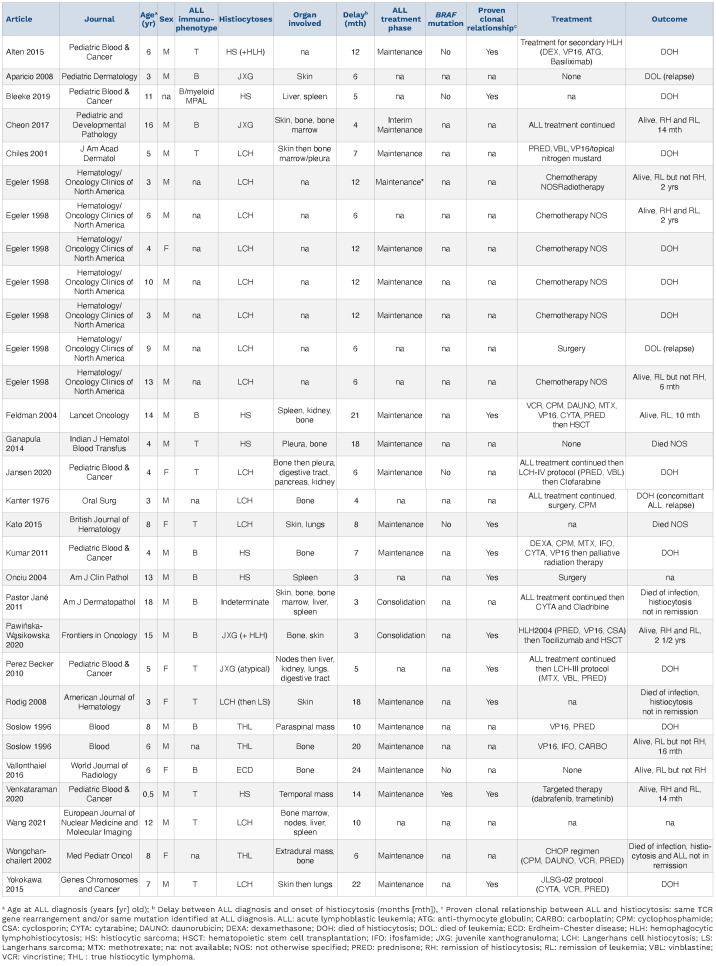

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and outcome of children with co-occurrence of histiocytic neoplasms during acute lymphoblastic leukemia therapy excluding H group disorders.

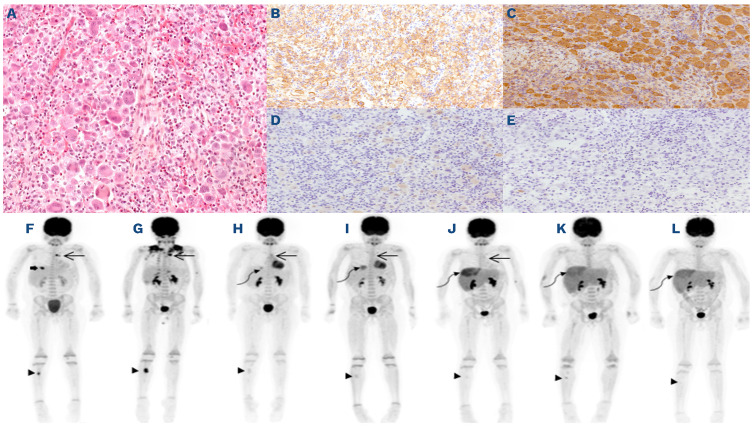

Figure 1.

Pathology of rib lesion and evolution of metabolic response over the course of therapy. (A) Rib lesion depicting predominant infiltration of large, multinucleated histiocytic cells with evidence of emperipolesis in the absence of necrosis or mitosis. The histiocytic cells are strongly positive for CD68 (not shown), (B) CD163, (C) Fascin, (D) weak and focal S100 staining and (E) negative for CD1a and CD207 (not shown). The following immunostains are negative: CD15, CD20, CD30, CD45, CD117, ALK, PAX5, EMA, HLA-DR, and MPO (not shown). Evolution of metabolic response by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) scans over the course of therapy. (F) At diagnosis of histiocytosis: mediastinal nodules (long arrow) SUVmax 4.2 and 8.2, right tibial diaphysis lesion (arrowhead) SUVmax 6.8 and 5th rib lesion (thick arrow) SUVmax 8.1; (G) post-rib biopsy and continuation of ALL therapy: progressive disease in the mediastinum SUVmax 10.1 and 12.4 and tibia SUVmax 11.5; (H) 1 month post-dabrafenib monotherapy: almost complete metabolic response in the mediastinum SUVmax 3.0 and right tibia SUVmax 1.5, new hepatic focus SUVmax 3.4 (curvilinear arrow) with remaining liver SUVmax 1.6 and liver size 14.5 cm CC; (I) 3 months post-dabrafenib and maintenance chemotherapy combination: complete metabolic response in the mediastinum and stable uptake in right tibia SUVmax 2.0. Progressive uptake of liver lesion SUVmax 4.3 with remaining liver SUVmax 2.0; (J) at isolated central nervous system relapse: no significant uptake in mediastinum or right tibia, progression in the uptake of liver lesion SUVmax 5.6 with diffuse hyperactivity of the remaining liver SUVmax 3.5; (K) after re-induction chemotherapy with nelarabine: no mediastinal lesion. Discrete uptake right tibia SUVmax 2.6. Persistent increased uptake in liver lesion SUVmax 4.0 and remaining liver SUVmax 3.2; (L) 100 days post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: no mediastinal or tibial lesions. Stable uptake in liver lesion SUVmax 4.0 and remaining liver SUVmax 3.0.

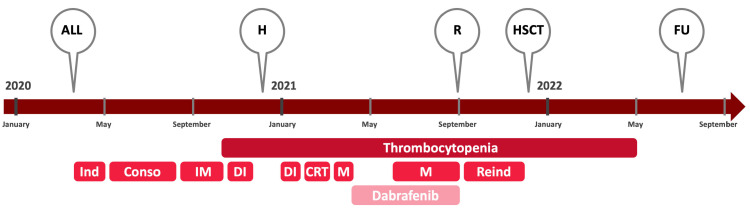

Figure 2.

Timeline illustrating different events and treatments of the case report. ALL: diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia; Conso: consolidation; CRT: cranial irradiation; DI: delayed intensification; FU: last follow-up; H: diagnosis of histiocytosis; HSCT: hematopoetic stem cell transplantation; Ind: induction; IM: interim maintenance; M: maintenance, R: relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia; Reind : reinduction.

References

- 1.Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127(22):2672-2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castro ECC, Blazquez C, Boyd J, et al. Clinicopathologic features of histiocytic lesions following ALL, with a review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2010;13(3):225-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleeke M, Johann P, Gröbner S, et al. GenomeDwide analysis of acute leukemia and clonally related histiocytic sarcoma in a series of three pediatric patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(2):e28074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunsmore KP, Winter SS, Devidas M, et al. Children’s Oncology Group AALL0434: a phase III randomized clinical trial testing nelarabine in newly diagnosed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(28):3282-3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Migdady Y, Ediriwickrema A, Jackson RP, et al. Successful treatment of thrombocytopenia with daratumumab after allogeneic transplant: a case report and literature review. Blood Adv. 2020;4(5):815-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitlock J, dalla Pozza L, Goldberg JM, et al. Nelarabine in combination with etoposide and cyclophosphamide is active in first relapse of childhood T-acute lymphocytic leukemia (T-ALL) and T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (T-LL). Blood. 2014;124(21):795-795. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donadieu J, Larabi IA, Tardieu M, et al. Vemurafenib for refractory multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: an international observational study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(31):2857-2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaspari S, Di Ruscio V, Stocchi F, Carta R, Becilli M, De Ioris MA. Case report: early association of vemurafenib to standard chemotherapy in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a newborn: taking a chance for a better outcome? Front Oncol. 2021;11:794498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116(11):1919-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papo M, Diamond EL, Cohen-Aubart F, et al. High prevalence of myeloid neoplasms in adults with non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2017;130(8):1007-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emile JF, Cohen-Aubart F, Collin M, et al. Histiocytosis. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):157-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]