Abstract

Purpose of Review

Neurosarcoidosis is a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis that is challenging to diagnose. Biopsy confirmation of granulomas is not sufficient, as other granulomatous diseases can present similarly. This review is intended to guide the clinician in identifying key conditions to exclude prior to concluding a diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis.

Recent Findings

Although new biomarkers are being studied, there are no reliable tests for neurosarcoidosis. Advances in serum testing and imaging have improved the diagnosis for key mimics of neurosarcoidosis in certain clinical scenarios, but biopsy remains an important method of differentiation.

Summary

Key mimics of neurosarcoidosis in all cases include infections (tuberculosis, fungal), autoimmune disease (vasculitis, IgG4-related disease), and lymphoma. As neurosarcoidosis can affect any part of the nervous system, patients should have a unique differential diagnosis tailored to their clinical presentation. Although biopsy can assist with excluding mimics, diagnosis is ultimately clinical.

Keywords: Neurosarcoidosis, Granuloma, Diagnosis, Mimics

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterized by the formation of granulomas, which may develop in any organ. Involvement of the nervous system, termed neurosarcoidosis, affects 5–10% of patients but may lead to potentially devastating outcomes [1••, 2••, 3–5]. Common presentations of neurosarcoidosis include cranial neuropathies, leptomeningeal disease, intraparenchymal lesions, and myelitis. However, initial presentations of stroke, seizure, cerebral vasculopathy, intracranial mass, hypopituitarism, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and encephalopathy have been reported [1••, 2••]. Establishing the diagnosis can be difficult due to the wide variety of clinical manifestations, the variability of coexistent systemic disease, and the challenges associated with obtaining a central nervous system (CNS) biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

In order to diagnose neurosarcoidosis based on current guidelines, the patient must have a compatible neurological clinical presentation and exclusion of other causes. Patients meeting these criteria can be classified as “possible” neurosarcoidosis [6•]. A biopsy revealing granulomatous inflammation is necessary for diagnosing definite (nervous system biopsy) and probable (biopsy of systemic site) neurosarcoidosis. Yet, this is not sufficient for diagnosis since many granulomatous diseases including infections, autoimmune conditions, and neoplastic disorders mimic sarcoidosis and initially respond to corticosteroid treatment. In patients with a known diagnosis of biopsy-proven systemic sarcoidosis, there is potential to overlook other etiologies when they develop cranial neuropathies or leptomeningeal disease suggestive of neurosarcoidosis. It is important to recognize these patients do not automatically meet criteria for “probable” neurosarcoidosis prior to consideration of mimics. Other diagnoses such as atypical infection and malignancy, particularly in light of treatment related complications, should be considered.

In this review, we will highlight notable clinical presentations of neurosarcoidosis and key mimics to consider. We will then discuss the role of diagnostic testing including serum and cerebrospinal fluid analysis, imaging, and biopsy in confirming the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis.

Differential Diagnosis and Mimics

Several diseases are known to mimic neurosarcoidosis both clinically and radiographically. Table 1 describes important conditions that mimic neurosarcoidosis in different clinical scenarios, comparing their shared and distinguishing features.

Table 1.

Distinguishing common mimics of neurosarcoidosis

| Shared CNS features | Shared systemic features | Distinguishing features | Diagnostic testing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis |

Predilection for the skull base (basilar meningitis) Leptomeningeal enhancement Cranial neuropathies Dural masses Steroid responsive initially |

Pulmonary disease Lymphadenopathy Ocular inflammation Constitutional symptoms Arthropathy |

TB is more likely to cause clinical meningitis, basilar exudates on neuroimaging, caseating granulomas on biopsy | CSF AFB smear, culture and PCR |

| Cryptococcus |

Leptomeningeal enhancement Cranial neuropathies Dural masses Steroid responsive initially |

Pulmonary disease Lymphadenopathy Ocular inflammation Constitutional symptoms |

Cryptococcus is more likely to cause clinical meningitis and hydrocephalus Pulmonary presentation may cause acute pneumonia or ARDS |

Serum cryptococcal antigen testing by LAF CSF culture |

| PACNS |

White matter lesions Leptomeningeal enhancement Vasculitis with noncaseating granulomas on biopsy Steroid responsive |

PACNS does not have systemic features |

PACNS does not have systemic features PACNS is more likely than neurosarcoidosis to cause CNS vasculitis |

CNS biopsy |

| GPA |

White matter lesions Steroid responsive Pachymeningeal enhancement Ocular inflammation |

Pulmonary disease Lymphadenopathy Ocular inflammation Sinusitis Constitutional symptoms Arthropathy |

GPA is more likely to cause diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, vasculitic skin rashes |

Biopsy of CNS or other systemic organ (skin, renal, lung) ANCA, anti-MPO, anti-PR3 |

| IgG4-RD |

Pachymeningeal enhancement Intraparenchymal mass Cranial neuropathies Steroid responsive |

Lymphadenopathy Ocular inflammation with or without pseudotumor Sinusitis Constitutional symptoms |

IgG4-RD is more likely to cause pancreatitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and kidney infiltration Vasculitis more frequently seen with IGG4-RD |

CNS biopsy, staining for IgG4 plasma cells, and looking for evidence of storiform fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis Serum IgG4 levels (nondiagnostic) |

| PCNSL |

Intracranial masses White matter lesions Cranial neuropathies Vasculitis Steroid responsive |

PCNSL does not have systemic features |

PCNSL does not have systemic features Steroid response wanes for PCNSL |

CNS biopsy, multiple may be required. CSF cytology and flow cytometry |

It is important to note that the term “meningitis” in the literature has multiple meanings. In our article, we will refer to clinical meningitis as a patient who presents with symptoms of fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, and nausea/vomiting. Although clinical meningitis, particularly the fever, is rarely seen in neurosarcoidosis, patients can present with headache and neurological symptoms along with radiographic findings of meningitis such as leptomeningeal enhancement [1••]. Neurosarcoidosis also causes chronic meningitis, in which cerebrospinal fluid findings of inflammation persist for over four weeks [1••, 2••, 7•, 8]. When acute clinical meningitis occurs in neurosarcoidosis, it presents similarly to other causes of acute aseptic meningitis which includes atypical infections, malignancies, and autoimmune diseases.

Infection

Essentially, all granulomatous infections can mimic neurosarcoidosis when they infiltrate into the central nervous system. These infections include atypical bacteria (mycobacterial, syphilis, Whipple’s disease, brucellosis, nocardiosis, actinomycosis), fungi (aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, and endemic mycoses), and parasites (toxoplasmosis, schistosomiasis, neurocysticercosis, toxocariasis) [9•, 10]. Many of these infections are rare, requiring a high index of suspicion to diagnose, but are important to exclude prior to initiating immunosuppressive therapies. A thorough exposure history and examination will guide diagnostic testing. Mycobacterial and fungal infections commonly mimic sarcoidosis and should be evaluated in all patients with suspected neurosarcoidosis.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an opportunistic chronic bacterial infection that commonly mimics pulmonary and systemic sarcoidosis and is a leading cause of death from infection worldwide [11]. CNS tuberculosis can present with cranial neuropathies, aseptic meningitis, transverse myelitis, or as masses in the spine or brain [12•]. Both CNS tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis have a predilection for the skull base and a preference to affect the leptomeninges. Neurosarcoidosis patients may have radiologic features of leptomeningeal enhancement without associated typical meningeal signs of fever with headache, nuchal rigidity, and nausea/vomiting. For example, patients may have isolated facial palsy with radiographic evidence of meningitis [13••]. In contrast, CNS tuberculosis typically presents with both radiographic and clinical meningitis. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies are similar, most frequently showing a lymphocytic pleocytosis with or without elevated protein and, in rare cases, a low glucose [14, 15]. The diagnosis of CNS tuberculosis is complex. As with other extrapulmonary tuberculosis presentations, tuberculin skin testing is often negative [16]. Acid fast bacillus (AFB) culture and smear on CSF and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based testing should be sent, but lack sufficient sensitivity, and repeat testing may be indicated [17, 18]. Newer studies show promise in the use of CSF lipoarabinomannan, a cell wall component for TB, or CSF interferon-release gamma assays [19, 20]. Biopsy is more likely to show caseating granulomas in TB as opposed to the noncaseating granulomas in sarcoidosis, but this is not a dependable way to distinguish the two, and culture remains the gold standard for diagnosis [21, 22].

Fungal infections cause granulomatous inflammation and mimic sarcoidosis, but rarely affect immunocompetent individuals. The infections that should be considered in individuals who do not clearly appear to be immunodeficient (particularly in the setting of uncontrolled diabetes) include cryptococcosis (C. gattii), aspergillosis (A. flavus), mucormycosis (Apophysomyces), and endemic mycoses such as coccidioidomycosis [23–26]. Cryptococcosis is the most common fungal meningitis [27, 28]. The most common neurologic presentation is clinical meningitis that may present with cranial neuropathy and hydrocephalus. Cranial nerve enhancement, leptomeningeal enhancement (often gyriform and nodular), nonenhancing mass lesions (cryptococcomas), and vascular abnormalities may be seen on imaging [29]. Lateral flow assay for serum cryptococcal antigen is a quick, affordable point of care test that is sensitive and specific for cryptococcal meningitis [30, 31]. Cerebrospinal fluid culture is the gold standard but may take up to two weeks for confirmatory testing.

Malignancy

CNS lymphoma encompasses both lymphoma originating in the CNS (primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL)) and lymphoma that has metastasized to the brain (secondary CNS lymphoma). Typical symptoms include focal neurological impairments, nonspecific neuropsychiatric or cognitive changes, and signs of increased intracranial pressure, the latter two of which are uncommon in neurosarcoidosis [1••] [32•, 33•]. PCNSL is usually supratentorial and commonly involves the optic tracts and basal ganglia [34], whereas in neurosarcoidosis, mass-like lesions are typically located at the skull base [35•].

Patients with secondary CNS lymphoma may have associated lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly. A lymph node biopsy is required to differentiate sarcoidosis from secondary CNS lymphoma as there are no serum tests to definitively differentiate the two. Excisional biopsy should be performed over needle aspiration or core biopsy because preservation of lymph node architecture is crucial for evaluating lymphoma. Cerebrospinal fluid cytology and cytometry have poor sensitivity for lymphoma, and a brain biopsy may be required to establish this diagnosis [36••]. CNS biopsy may miss the diagnosis, especially in patients who have been treated with steroids, and repeat biopsy may be warranted [37].

Autoimmune

Many systemic autoimmune diseases share features with and can mimic neurosarcoidosis when the CNS is involved.

Neurosarcoidosis and CNS vasculitis have considerable overlap, with shared neuroimaging features, common laboratory and cerebrospinal fluid results, and even the presence of granulomas on biopsy [38••]. Systemic sarcoidosis is known to cause variable vessel vasculitis rarely, and case reports have shared that neurosarcoidosis may present with CNS vasculitis [39, 40•].

Primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS) may present as white matter lesions and leptomeningeal enhancement [41]. Both diagnoses may also present as pachymeningitis, though less commonly [1••]. Biopsy in PACNS can reveal noncaseating granulomas [42]. A key difference is that PACNS does not have systemic manifestations. One study has demonstrated that involvement of the spinal cord, basilar meninges, or cranial nerves on imaging tends to favor a diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis over CNS vasculitis [38••].

ANCA vasculitis including limited granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) may present as hypertrophic pachymeningitis, with neurosarcoidosis and other systemic vasculitides on the differential [43]. These include polyarteritis nodosa, rheumatoid vasculitis, relapsing polychondritis, neuro-Behcet’s disease, and Cogan syndrome [44••, 45].

IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a systemic fibroinflammatory disease of unknown origin that can affect virtually any organ system and is often on the differential diagnosis for atypical presentations of systemic sarcoidosis. This condition presents insidiously and is associated with inflammatory pseudotumors mimicking cancer [46]. Patients with CNS involvement classically will have a finding of hypertrophic pachymeningitis or hypophysitis and diagnosis is elusive, often requiring a meningeal biopsy with special staining for IgG4 plasma cells [47••, 48, 49]. Lymphadenopathy, orbital inflammation, and sinus involvement are seen in both diseases, but IgG4-RD is more likely to affect the pancreas, salivary glands, and lacrimal glands which are some of its prominent features [50]. The presence of granulomas on biopsy excludes IgG4-RD except when found coincidentally with the typical features of dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, storiform-type fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis [51, 52•].

Clinical Features and Diagnostic Testing

Clinical Presentations of Neurosarcoidosis

About fifty percent of patients with neurosarcoidosis present with neurological symptoms prior to systemic involvement [1••]. In the other half, a review of systemic symptoms will help narrow the differential.

The most common systemic sites affected in patients with neurosarcoidosis are the pulmonary system, lymph nodes, eyes, and skin [1••]. All patients should receive chest imaging to look for bilateral hilar/mediastinal lymphadenopathy or upper lobe predominant interstitial lung disease (reticulonodular opacities) [53, 54]. However, many granulomatous diseases including tuberculosis, fungal infections, and berylliosis may present with identical pulmonary imaging findings since granulomatous deposition is more likely to occur in the apices due to impairment of lymphatics [55]. Ocular sarcoidosis is frequently an initial manifestation of sarcoidosis, and any part of the eye can be affected [56]. The most common features are uveitis, dry eyes, and conjunctival nodules [57]. Ocular inflammation can co-occur with optic neuritis, which we will discuss in the section on cranial nerve palsies. Finally, a wide variety of rashes can manifest, but the clinician should focus on looking for key patterns including erythema nodosum, lupus pernio, and a papulonodular rash affecting tattoos [58–60].

In the following sections, we will cover four prominent presentations of neurosarcoidosis including cranial nerve palsies, spinal involvement, meningeal involvement, and parenchymal involvement. In each section, we will cover the differential diagnosis and key distinguishing features.

Cranial Nerve Palsies

Peripheral facial palsy is most commonly caused by Bell’s palsy (idiopathic), Lyme disease, variants of Guillain–Barre syndrome, viral infections (HIV, EBV, CMV), and sarcoidosis. The facial nerve is the most commonly affected cranial nerve in sarcoidosis and may be the first manifestation [13••, 61]. Sarcoidosis can cause facial palsy through multiple mechanisms including meningeal inflammation, parotitis, spinal disease, stroke/vasculitis, or compression from intraparenchymal lesions. Though unilateral involvement is common, simultaneous or sequential bilateral involvement may occur [13••]. MRI is often normal, but when abnormal, the most common findings are facial nerve enhancement or leptomeningeal enhancement [13••]. When bilateral facial palsy is seen, Lyme disease should be excluded.

When facial palsy occurs with unilateral throat or neck pain and swelling, parotitis should be considered. Heerfordt-Waldenström syndrome which causes parotitis, facial palsy, fever, and ocular inflammation is pathognomonic for sarcoidosis [62–64]. Recent cases demonstrate that this can present with other findings of neurosarcoidosis such as with other cranial nerve palsies or with radiculopathy [64].

Neurosarcoidosis may also involve the optic nerve [1••]. Patients may present with a subtle, painless optic neuritis diagnosed incidentally on MRI or a slowly progressive optic neuropathy (ischemic rather than inflammatory) [65••]. Thirty percent of patients have bilateral disease, and 36% had concurrent eye inflammation, usually uveitis. Uveitis is also caused by infections (TB, candida, and varicella zoster virus most commonly) and other autoimmune diseases, most commonly inflammatory bowel disease and Behcet’s. Ocular lymphoma can masquerade as scleritis or uveitis [66]. Sarcoidosis can also cause orbital inflammation, presenting as a mass (pseudotumor) which mimics malignancy, lymphoproliferative diseases secondary to systemic connective tissue diseases, and IgG4-RD [67•].

Demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and infections such as tuberculosis can also cause both uveitis and optic neuritis simultaneously [68–71]. The presence of leptomeningeal enhancement, intraparenchymal masses, or linear enhancement affecting blood vessels adjacent to white matter lesions on MRI favors neurosarcoidosis over MS [72]. Optical coherence tomography can pick up subclinical retinal changes and may assist with differentiating sarcoidosis from infectious or other mimics [73, 74].

Neurosarcoidosis may cause cranial neuropathies via direct compression, meningeal irritation, or skull base inflammation [1••, 2••]. Tumors and infections causing cavernous sinus syndrome are the most common causes of multiple cranial neuropathies [75, 76•]. Other systemic autoimmune diseases including lupus, Sjogren’s syndrome, and vasculitis have been reported to cause multiple cranial neuropathies [77].

Recently, a CNS limited form of granulomatosis with polyangiitis has been described that can present with chronic sinusitis, otitis or mastoiditis, autoimmune hearing loss, and multiple cranial neuropathies with pachymeningitis on neuroimaging [78]. ANCA can be low titer or negative, leading to misdiagnosis [78]. MRI findings of a parapharyngeal epicenter and lack of necrosis favor GPA over infection, but there are no described distinguishing features from neurosarcoidosis [79•].

Spinal Involvement

Spinal sarcoidosis, sometimes referred to as sarcoid myelopathy, can cause significant disability. It usually presents with lower extremity weakness and paresthesias and more commonly co-occurs with brain involvement [80, 81]. Any segment of the spine can be affected, and imaging may show what appears to be an intramedullary mass, mimicking cancer [82]. The most common MRI finding is leptomeningeal enhancement [82, 83], and three radiographic patterns have been described: longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, short tumefactive myelitis, and spinal meningitis with extramedullary enhancement [84•].

Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) is defined by a spinal lesion extending across more than three vertebrae and is most commonly due to neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD). Distinguishing features between spinal sarcoidosis and NMOSD are subtle and may not be reliable [85, 86] in a study investigating differences between the two, female sex, history of concurrent optic neuritis, and systemic autoimmunity were more often seen with NMOSD [86]. However, these features commonly overlap with sarcoidosis. Symptoms of intractable hiccups, nausea, and vomiting suggest area postrema syndrome, a pathognomonic and unique manifestation of NMOSD [87]. Other important causes of LETM to consider are spinal infections such as tuberculosis, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis including lymphoma, toxic myelopathies, and idiopathic transverse myelitis.

Meningeal Involvement

Neurosarcoidosis most commonly affects the leptomeninges (pia and arachnoid mater). It has a predilection for the base of the skull but can occur throughout the brain or spinal cord [35•]. Headaches are common in patients with radiographic leptomeningeal inflammation, but the additional presence of fever and nuchal rigidity to suggest clinical meningitis is rarely seen [14]. In the brainstem, compression of exiting nerve roots may cause cranial neuropathies. The presence of cognitive or vision changes associated with headaches should raise suspicion for the rare but dangerous complication of obstructive hydrocephalus, which may require surgical intervention [32•]. Notably, myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-associated disease (MOGAD), characterized by anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies, should be considered for patients with leptomeningitis associated with optic neuritis or myelitis [88]. In contrast to neurosarcoidosis, MOGAD does not usually cause brainstem or cerebellar symptoms [89]. Similarly, autoimmune encephalitis (AE) must be on the differential for patients with leptomeningitis and CSF lymphocytic pleocytosis. Clinical features more often seen in AE such as seizures and subacute onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms localizing to the limbic system can help distinguish it from neurosarcoidosis. The brain MRI in AE may show bilateral medial temporal T2/FLAIR hyperintensities which would be unusual for neurosarcoidosis [90].

Sarcoidosis can also cause pachymeningitis (inflammation of the dura mater). Dural involvement may happen throughout the cranium where it can be diffuse or mass-like. Patients with pachymeningitis may experience seizures, progressive hearing loss, headaches, or cognitive dysfunction [91]. The differential diagnosis of pachymeningitis is broad and includes IgG4-related disease, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, dural-based metastases, and infections such as Lyme disease, tuberculosis, and syphilis [92, 93]. The most common cause of chronic, progressive pachymeningitis is idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis [94].

Parenchymal Involvement

Parenchymal involvement of neurosarcoidosis causes symptoms specific to the location involved. Multifocal lesions are more frequently observed than solitary lesions [91, 95]. In rare instances, a mass-like appearance is seen on imaging [96]. These lesions can mimic malignancy (primary, metastatic, or lymphoma) or infections (tuberculoma, cryptococcoma). Masses that lack enhancement or show central necrosis should prompt further evaluation for malignancy as these features would not be expected in neurosarcoidosis [97]. A mass lesion with open ring enhancement adjacent to gray matter is more typical for tumefactive demyelination as can be seen in the Marburg variant of MS [72]. In rare instances, neuroimaging may demonstrate multifocal lesions with an appearance that can mimic MS [98].

Serum Biomarkers

There are no serum markers that can definitively separate sarcoidosis from its mimics. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme is a marker of granulomatous inflammation, but lacks sufficient sensitivity and specificity [1••]. Recent studies show that serum soluble IL-2 receptor, which is a surrogate for T cell activation, could be a promising biomarker for sarcoidosis. One study showed a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 85%, but this may be confounded by a testing bias resulting in a higher pretest probability. Other autoimmune diseases can also increase the serum soluble IL-2 receptor [99].

The most useful serologic tests for diagnosing neurosarcoidosis may be tests to exclude other diseases such as mycobacterial and fungal cultures, cytology, and other targeted tests for infections and autoimmune diseases. It is possible that each manifestation of neurosarcoidosis will have its own unique serum biomarker profile. More research is needed to investigate these possibilities.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Studies

There are no cerebrospinal fluid tests that are diagnostic for neurosarcoidosis. Cerebrospinal fluid testing may reveal lymphocytic pleocytosis with elevation of protein and low glucose. Recent studies suggest that CD8 T cells may be predominant [100] in the cerebrospinal fluid. Other tests including IgG index, oligoclonal bands, and CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme levels may also be elevated in about 40–60% of patients [1••]. However, these are not specific nor sensitive for neurosarcoidosis [1••, 15, 101, 102]. New potential CSF biomarkers are being investigated, including soluble IL-2 receptor or CD4/CD8 T cell ratio [103]. Hopefully, better CSF biomarkers will be identified soon that can aid in diagnosis.

Role of Biopsy

Diagnostic criteria for neurosarcoidosis rely on biopsy to obtain a diagnosis of “probable” or “definite” neurosarcoidosis. The expected results of biopsy are noncaseating granulomas, but no other specific patterns exist that will help distinguish granulomas from sarcoidosis with other granulomatous diseases. Granulomas are organized clusters of inflammatory cells characterized by central core of T cells, macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and epithelioid cells surrounded by tissue. In sarcoidosis, they are thought to form in response to an unknown antigen, possibly by cross-reactivity, leading to infiltration into different areas of the body and consequent inflammatory damage [104]. Sarcoid granulomas are typically nonnecrotizing (noncaseating), in contrast to the caseating granulomas seen in tuberculosis and other infections [104]. When granulomas in sarcoidosis resolve either due to treatment or spontaneously, fibrosis may result [104, 105]. However, it is important to note that caseation cannot reliably be used to distinguish sarcoidosis from infections and that occasionally biopsy may not reveal granulomas. The CNS remains a difficult area for biopsy, and thus, investigation for another systemic site such as the skin, lymph node, or lung which are more accessible areas can be beneficial to establishing the presence of granulomas.

Neuroimaging Findings

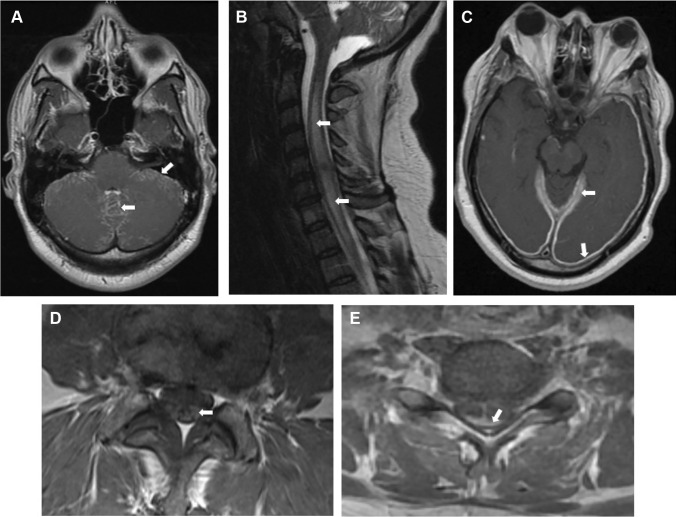

Imaging remains an essential tool in evaluation of sarcoidosis. However, as with systemic sarcoidosis, many of the imaging findings in neurosarcoidosis can be caused by its mimics (Table 2). In general, contrasted MRI is the preferred imaging modality for neurosarcoidosis as it can reveal enhancement corresponding with active inflammation. Figure 1 highlights several MRI findings seen in neurosarcoidosis.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis according to radiographic features

| Leptomeningeal enhancement | Extra-axial intracranial lesions | Transverse myelitis | Interstitial lung disease | Hilar/mediastinal lymphadenopathy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis |

+ + + Involvement of basal cisterns |

+ + + Tuberculoma |

+ Can cause LETM* |

+ + + |

+ + + More likely unilateral/asymmetric |

| Cryptococcus | + + + | – | + |

+ Associated with pulmonary nodules or pneumonia |

+ + + Rarely can present as isolated lymphadenopathy on chest imaging |

| PACNS | + + + | + |

+ Unlikely without concurrent brain involvement |

– | – |

| GPA |

+ More commonly causes pachymeningitis |

+ | + |

+ Associated with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

+ + + Rarely can present as isolated lymphadenopathy on chest imaging |

| IgG4-RD w/ CNS involvement |

+ More commonly causes pachymeningitis |

+ + + | + | + | + + + |

| PCNSL |

+ + + Isolated enhancement is rare, but enhancement with mass lesions is common |

+ + + |

+ Can cause LETM |

– Consider other lymphoma subtypes |

– Common in secondary CNS lymphoma |

“ + + + ” means that the radiographic finding is common for the corresponding disease. “ + ” means that the radiographic finding is seen, but rare, for the corresponding disease. And “–” means that the radiographic finding is either extremely rare or not seen

*LETM longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis

Fig. 1.

Selected MRI (T1 with contrast) imaging findings from patients with neurosarcoidosis. A Diffuse basilar leptomeningitis. B Longitudinally extensive myelitis in the cervical spine. C Pachymeningitis causing pachymeningeal enhancement. D Lumbar nerve roots showing enhancement. E Dorsal subpial leptomeningeal enhancement resulting in a “Trident Sign”

The contrasted T1 sequence is particularly useful for demonstrating leptomeningeal involvement, myelitis, or parenchymal lesions. The T2/FLAIR sequence is useful for identifying chronic lesions and for assessing the pattern and location of inflammatory damage. Since any region of the CNS can be affected, care should be taken when determining which sections to image. Dedicated imaging of the entire neuraxis (orbits, brain, and spine) may be necessary. Although nerve root involvement distinguishes neurosarcoidosis from other CNS diseases (e.g., MS and NMOSD), it can be seen in other inflammatory conditions such as Guillain–Barre syndrome [106].

Leptomeningeal involvement can occur in either the brain or spinal cord. The most common area of involvement in the cerebrum is the basilar leptomeninges affecting around 40% of patients [107, 108]. It may appear serpentine as it follows the sulci where it must be carefully distinguished from blood vessels which also appear hyperintense when filled with contrast. Care should also be taken to look at the noncontrasted T1 sequence to distinguish from other causes of T1 hyperintense signal in the leptomeninges such as methemoglobin (subarachnoid hemorrhage) or melanin from metastatic melanoma [109••]. A pathognomonic finding in the spinal cord is the “Trident Sign” with a characteristic dorsal subpial pattern of enhancement [110].

Involvement of dura mater, causing pachymeningitis, with thickening and contrast enhancement, can be seen on contrasted T1 imaging. Hydrocephalus can be seen in around 5–12% of cases and is visible on T2/FLAIR or T1 images [32•, 108].

For sarcoid vasculitis, computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is typical for initial diagnostic evaluation. If suspicion remains high despite inconclusive findings, digital subtraction angiography may be needed [111]. Sarcoid vasculitis is a variable vessel vasculitis (similar to Behcet’s) and, like most vasculitides, causes vessel narrowing on imaging and may lead to ischemic strokes [95, 112].

If neurosarcoidosis is presenting with parenchymal involvement, multiple intraparenchymal lesions are seen more frequently than solitary mass-like lesions [8]. These typically appear T2/FLAIR hyperintense and may contrast enhance on contrasted T1-weighted imaging [95]. Periventricular lesions, best seen on FLAIR, can appear demyelinating, but if there are other lesions in locations typical of demyelinating disease (juxtacortical, infratentorial) then comorbid MS should be considered [113].

Conclusions

Neurosarcoidosis can be a diagnostic challenge. Exclusion of mimics remains an important aspect of management, especially when patients do not respond appropriately to therapy. The diversity of manifestations in neurosarcoidosis is such that each patient may present with a unique set of findings that will dictate the relevant differential diagnosis for that individual. Important mimics that share systemic and neurologic features, laboratory workup, imaging findings, and biopsy results are infections (mycobacterial, fungal), lymphoma, autoimmune vasculitis (PACNS, GPA), and IgG4-RD. However, with thorough and thoughtful review of history, physical exam, and targeted testing, these may be differentiated from neurosarcoidosis.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available for subscribed members to this journal or members of the American Academy of Neurology.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Fritz D, van de Beek D, Brouwer MC. Clinical features, treatment and outcome in neurosarcoidosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2016;16(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0741-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.•• Barreras P, Stern BJ. Clinical features and diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis - review article. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;368:577871. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577871. This is the most recent, comprehensive review providing diagnostic algorithms for clinicians to use when evaluating patients with suspected neurosarcoidosis. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kidd DP. Neurosarcoidosis: clinical manifestations, investigation and treatment. Pract Neurol. 2020;20(3):199–212. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2019-002349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradshaw MJ, Pawate S, Koth LL, Cho TA, Gelfand JM. Neurosarcoidosis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(6). 10.1212/nxi.0000000000001084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, Rovaris M, Evanson J, Moseley IF, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis–diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999;92(2):103–117. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern BJ, Royal W, III, Gelfand JM, Clifford DB, Tavee J, Pawate S, et al. Definition and consensus diagnostic criteria for neurosarcoidosis: from the Neurosarcoidosis Consortium Consensus Group. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(12):1546–1553. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin KJ, Avila JD. Diagnostic approach to chronic meningitis. Neurol Clin. 2018;36(4):831–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowak DA, Widenka DC. Neurosarcoidosis: a review of its intracranial manifestation. J Neurol. 2001;248(5):363–372. doi: 10.1007/s004150170175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Challa S. Granulomatous diseases of the central nervous system: approach to diagnosis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2022;65(Supplement):S125–S134. doi: 10.4103/ijpm.ijpm_1067_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zumla A, James DG. Granulomatous infections: etiology and classification. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(1):146–158. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furin J, Cox H, Pai M. Tuberculosis Lancet. 2019;393(10181):1642–1656. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dian S, Ganiem AR, van Laarhoven A. Central nervous system tuberculosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2021;34(3):396–402. doi: 10.1097/wco.0000000000000920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nwebube CO, Bou GA, Castilho AJ, Hutto SK. Facial nerve palsy in neurosarcoidosis: clinical course, neuroinflammatory accompaniments, ancillary investigations, and response to treatment. J Neurol. 2022;269(10):5328–5336. doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos-Casals M, Pérez-Alvarez R, Kostov B, Gómez-de-la-Torre R, Feijoo-Massó C, Chara-Cervantes J, et al. Clinical characterization and outcomes of 85 patients with neurosarcoidosis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13735. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92967-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arun T, Pattison L, Palace J. Distinguishing neurosarcoidosis from multiple sclerosis based on CSF analysis: a retrospective study. Neurology. 2020;94(24):e2545–e2554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000009491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leonard JM. Central nervous system tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5(2). 10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0044-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Pehlivanoglu F, Yasar KK, Sengoz G. Tuberculous meningitis in adults: a review of 160 cases. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:169028. 10.1100/2012/169028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Pai M, Flores LL, Pai N, Hubbard A, Riley LW, Colford JM., Jr Diagnostic accuracy of nucleic acid amplification tests for tuberculous meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(10):633–643. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddiqi OK, Birbeck GL, Ghebremichael M, Mubanga E, Love S, Buback C, et al. Prospective cohort study on performance of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Xpert MTB/RIF, CSF lipoarabinomannan (LAM) lateral flow assay (LFA), and urine LAM LFA for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in Zambia. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57(8). 10.1128/jcm.00652-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Wen A, Leng EL, Liu SM, Zhou YL, Cao WF, Yao DY, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of interferon-gamma release assays for tuberculous meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:788692. 10.3389/fcimb.2022.788692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Abbasi F, Ozer M, Juneja K, Goksu SY, Mobarekah BJ, Whitman MS. Intracranial tuberculoma mimicking neurosarcoidosis: a clinical challenge. Infect Dis Rep. 2021;13(1):181–186. doi: 10.3390/idr13010020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarman PR. Meningeal granulomas: sarcoidosis or tuberculosis? Differentiation can be difficult Bmj. 1995;310(6978):517–520. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6978.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regmi BU, Pathak BD, Subedi RC, Dhakal B, Sapkota S, Joshi S, et al. Neuro-cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent individual with radiologically atypical findings: a case report and review of literature. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2023;2023(3):omad016. 10.1093/omcr/omad016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Krishnan S, Manavathu EK, Chandrasekar PH. Aspergillus flavus: an emerging non-fumigatus Aspergillus species of significance. Mycoses. 2009;52(3):206–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parikh SL, Venkatraman G, DelGaudio JM. Invasive fungal sinusitis: a 15-year review from a single institution. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18(2):75–81. doi: 10.1177/194589240401800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang R, Stokes W, Lemaire J, Johnson A, Conly J. A case report of Coccidioides posadasii meningoencephalitis in an immunocompetent host. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):722. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4329-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottfredsson M, Perfect JR. Fungal meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2000;20(3):307–322. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomes MZ, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Mucormycosis caused by unusual mucormycetes, non-Rhizopus, -Mucor, and -Lichtheimia species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(2):411–445. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00056-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S, Chen X, Zhang Z, Quan L, Kuang S, Luo X. MRI findings of cerebral cryptococcosis in immunocompetent patients. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55(1):52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2010.02229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams DA, Kiiza T, Kwizera R, Kiggundu R, Velamakanni S, Meya DB, et al. Evaluation of fingerstick cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay in HIV-infected persons: a diagnostic accuracy study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):464–467. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajasingham R, Wake RM, Beyene T, Katende A, Letang E, Boulware DR. Cryptococcal meningitis diagnostics and screening in the era of point-of-care laboratory testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57(1). 10.1128/jcm.01238-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Ten Dam L, van de Beek D, Brouwer MC. Clinical characteristics and outcome of hydrocephalus in neurosarcoidosis: a retrospective cohort study and review of the literature. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2727–2733. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10882-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grommes C, Rubenstein JL, DeAngelis LM, Ferreri AJM, Batchelor TT. Comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment of newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(3):296–305. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joshi A, Deshpande S, Bayaskar M. Primary CNS lymphoma in Immunocompetent patients: appearances on conventional and advanced imaging with review of literature. J Radiol Case Rep. 2022;16(7):1–17. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v16i7.4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlson ML, White JR, Jr, Espahbodi M, Haynes DS, Driscoll CL, Aksamit AJ, et al. Cranial base manifestations of neurosarcoidosis: a review of 305 patients. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(1):156–166. doi: 10.1097/mao.0000000000000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott BJ, Douglas VC, Tihan T, Rubenstein JL, Josephson SA. A systematic approach to the diagnosis of suspected central nervous system lymphoma. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(3):311–319. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feldman L, Li Y, Ontaneda D. Primary CNS lymphoma initially diagnosed as vasculitis. Neurol Clin Pract. 2020;10(1):84–88. doi: 10.1212/cpj.0000000000000693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.•• Saygin D, Jones S, Sundaram P, Calabrese LH, Messner W, Tavee JO, et al. Differentiation between neurosarcoidosis and primary central nervous system vasculitis based on demographic, cerebrospinal and imaging features. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38 Suppl 124(2):135–8. This resource will help the clinician differentiate PACNS from neurosarcoidosis. [PubMed]

- 39.Maekawa T, Goto Y, Aoki T, Hino A, Oka H, Yokoya S, et al. Acute central nervous system vasculitis as a manifestation of neurosarcoidosis: a case report and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16(2):410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boulouis G, de Boysson H, Zuber M, Guillevin L, Meary E, Costalat V, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: magnetic resonance imaging spectrum of parenchymal, meningeal, and vascular lesions at baseline. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1248–1255. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.116.016194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bajaj BK, Pandey S, Ramanujam B, Wadhwa A. Primary angiitis of central nervous system: the story of a great masquerader. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015;6(3):399–401. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.158781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Cai M, Lai N, Chen Z, Ding M. Central nervous system involvement in ANCA-associated vasculitis: what neurologists need to know. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1166. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.•• Kandemirli SG, Bathla G. Neuroimaging findings in rheumatologic disorders. J Neurol Sci. 2021;427:117531. 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117531. This resource will help the clinician exclude autoimmune mimics on neuroimaging. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Villa E, Sarquis T, de Grazia J, Núñez R, Alarcón P, Villegas R, et al. Rheumatoid meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(9):3201–3210. doi: 10.1111/ene.14904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maritati F, Peyronel F, Vaglio A. IgG4-related disease: a clinical perspective. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(Suppl 3):iii123-iii31. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez667. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.•• Saitakis G, Chwalisz BK. The neurology of IGG4-related disease. J Neurol Sci. 2021;424:117420. 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117420. This is the most updated review on CNS IgG4-RD, and will help the clinican exclude this mimic. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Woo PYM, Ng BCF, Wong JHM, Ng OKS, Chan TSK, Kwok NF, et al. The protean manifestations of central nervous system IgG4-related hypertrophic pachymeningitis: a report of two cases. Chin Neurosurg J. 2021;7(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s41016-021-00233-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amirbaigloo A, Esfahanian F, Mouodi M, Rakhshani N, Zeinalizadeh M. IgG4-related hypophysitis. Endocrine. 2021;73(2):270–291. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baptista B, Casian A, Gunawardena H, D'Cruz D, Rice CM. Neurological manifestations of IgG4-related disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2017;19(4):14. doi: 10.1007/s11940-017-0450-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, Yi EE, Sato Y, Yoshino T, et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(9):1181–1192. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wallace ZS, Naden RP, Chari S, Choi HK, Della-Torre E, Dicaire JF, et al. The 2019 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for IgG4-related disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(1):77–87. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller BH, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, McAdams HP, Fishback NF. Thoracic sarcoidosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1995;15(2):421–437. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.15.2.7761646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Armstrong P, Wilson AG, Dee P, Hansell DM. Imaging of diseases of the chest. vol Ed. 3. Mosby International Ltd; 2000.

- 55.Nemec SF, Bankier AA, Eisenberg RL. Upper lobe-predominant diseases of the lung. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(3):W222–W237. doi: 10.2214/ajr.12.8961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma SP, Rogers SL, Hall AJ, Hodgson L, Brennan J, Stawell RJ, et al. Sarcoidosis-related uveitis: clinical presentation, disease course, and rates of systemic disease progression after uveitis diagnosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;198:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(4):669–683. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Serup J. How to diagnose and classify tattoo complications in the clinic: a system of distinctive patterns. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:58–73. doi: 10.1159/000450780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Redissi A, Penmetsa GK, Litaiem N. Lupus pernio. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. [PubMed]

- 60.Popatia S, Wanat KA. Lupus pernio JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(4):446. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.6007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ibitoye RT, Wilkins A, Scolding NJ. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical approach to diagnosis and management. J Neurol. 2017;264(5):1023–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8336-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stern BJ, Krumholz A, Johns C, Scott P, Nissim J. Sarcoidosis and its neurological manifestations. Arch Neurol. 1985;42(9):909–917. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060080095022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.James DG, Sharma OP. Parotid gland sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Makimoto G, Kawakado K, Nakanishi M, Tamura T, Noda M, Makimoto S, et al. Heerfordt’s syndrome associated with trigeminal nerve palsy and reversed halo sign. Intern Med. 2021;60(11):1747–1752. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.6176-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.•• Kidd DP, Burton BJ, Graham EM, Plant GT. Optic neuropathy associated with systemic sarcoidosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016;3(5):e270. 10.1212/nxi.0000000000000270. This is the most updated and largest study on patients with optic neuropathy from sarcoidosis [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Rothova A, Ooijman F, Kerkhoff F, Van Der Lelij A, Lokhorst HM. Uveitis masquerade syndromes. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(2):386–399. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00499-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.• Ronquillo Y, Patel BC. Nonspecific orbital inflammation. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC. 2023. This resource provides a differential diagnosis for orbital pseudotumor.

- 68.Thouvenot E, Mura F, De Verdal M, Carlander B, Charif M, Schneider C, et al. Ipsilateral uveitis and optic neuritis in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int. 2012;2012:372361. 10.1155/2012/372361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Casselman P, Cassiman C, Casteels I, Schauwvlieghe PP. Insights into multiple sclerosis-associated uveitis: a scoping review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99(6):592–603. 10.1111/aos.14697. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Chan F, Riminton DS, Ramanathan S, Reddel SW, Hardy TA. Distinguishing CNS neurosarcoidosis from multiple sclerosis and an approach to “overlap” cases. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;369:577904. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577904. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Davis EJ, Rathinam SR, Okada AA, Tow SL, Petrushkin H, Graham EM, et al. Clinical spectrum of tuberculous optic neuropathy. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2012;2(4):183–189. doi: 10.1007/s12348-012-0079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Algahtani H, Shirah B, Alassiri A. Tumefactive demyelinating lesions: a comprehensive review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;14:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pichi F, Invernizzi A, Tucker WR, Munk MR. Optical coherence tomography diagnostic signs in posterior uveitis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020;75:100797. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.100797. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Eckstein C, Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Byraiah G, Seigo M, Stankiewicz A, et al. Detection of clinical and subclinical retinal abnormalities in neurosarcoidosis with optical coherence tomography. J Neurol. 2012;259(7):1390–1398. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keane JR. Multiple cranial nerve palsies: analysis of 979 cases. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(11):1714–1717. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.11.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mehta MM, Garg RK, Rizvi I, Verma R, Goel MM, Malhotra HS, et al. The multiple cranial nerve palsies: a prospective observational study. Neurol India. 2020;68(3):630–635. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.289003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perzyńska-Mazan J, Maślińska M, Gasik R. Neurological manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Reumatologia. 2018;56(2):99–105. doi: 10.5114/reum.2018.75521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yokoseki A, Saji E, Arakawa M, Kosaka T, Hokari M, Toyoshima Y, et al. Hypertrophic pachymeningitis: significance of myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 2):520–536. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.• Lee B, Bae YJ, Choi BS, Choi BY, Cho SJ, Kim H, et al. Radiologic differentiation between granulomatosis with polyangiitis and its mimics involving the skull base in humans using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(11). 10.3390/diagnostics11112162. This resource will guide the clinician evaluate the differential diagnosis of skull base inflammation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Park BJ, Ray E, Bathla G, Bruch LA, Streit JA, Cho TA, et al. Single center experience with isolated spinal cord neurosarcoidosis. World Neurosurg. 2021;156:e398–e407. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.09.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakushima K, Yabe I, Nakano F, Yoshida K, Tajima Y, Houzen H, et al. Clinical features of spinal cord sarcoidosis: analysis of 17 neurosarcoidosis patients. J Neurol. 2011;258(12):2163–2167. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sohn M, Culver DA, Judson MA, Scott TF, Tavee J, Nozaki K. Spinal cord neurosarcoidosis. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347(3):195–198. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182808781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Soni N, Bathla G, Pillenahalli MR. Imaging findings in spinal sarcoidosis: a report of 18 cases and review of the current literature. Neuroradiol J. 2019;32(1):17–28. doi: 10.1177/1971400918806634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.• Murphy OC, Salazar-Camelo A, Jimenez JA, Barreras P, Reyes MI, Garcia MA, et al. Clinical and MRI phenotypes of sarcoidosis-associated myelopathy. Neurology - Neuroimmunology Neuroinflammation. 2020;7(4):e722. 10.1212/nxi.0000000000000722. This is the most recent study on sarcoid myelopathy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Tobin WO, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27(3):279–289. doi: 10.1097/wco.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Flanagan EP, Kaufmann TJ, Krecke KN, Aksamit AJ, Pittock SJ, Keegan BM, et al. Discriminating long myelitis of neuromyelitis optica from sarcoidosis. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(3):437–447. doi: 10.1002/ana.24582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shosha E, Dubey D, Palace J, Nakashima I, Jacob A, Fujihara K, et al. Area postrema syndrome. Neurology. 2018;91(17):e1642. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Gombolay GY, Gadde JA. Aseptic meningitis and leptomeningeal enhancement associated with anti-MOG antibodies: a review. J Neuroimmunol. 2021;358:577653. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2021.577653. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Banwell B, Bennett JL, Marignier R, Kim HJ, Brilot F, Flanagan EP, et al. Diagnosis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: International MOGAD Panel proposed criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(3):268–282. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00431-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, Benseler S, Bien CG, Cellucci T, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. The Lancet Neurology. 2016;15(4):391–404. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(15)00401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kidd DP. Sarcoidosis of the central nervous system: clinical features, imaging, and CSF results. J Neurol. 2018;265(8):1906–1915. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-8928-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wallace ZS, Carruthers MN, Khosroshahi A, Carruthers R, Shinagare S, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, et al. IgG4-related disease and hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2013;92(4):206–216. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31829cce35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kupersmith MJ, Martin V, Heller G, Shah A, Mitnick HJ. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Neurology. 2004;62(5):686–694. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113748.53023.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mekinian A, Maisonobe L, Boukari L, Melenotte C, Terrier B, Ayrignac X, et al. Characteristics, outcome and treatments with cranial pachymeningitis: a multicenter French retrospective study of 60 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(30):e11413. 10.1097/MD.0000000000011413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Jachiet V, Lhote R, Rufat P, Pha M, Haroche J, Crozier S, et al. Clinical, imaging, and histological presentations and outcomes of stroke related to sarcoidosis. J Neurol. 2018;265(10):2333–2341. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Veres L, Utz JP, Houser OW. Sarcoidosis presenting as a central nervous system mass lesion. Chest. 1997;111(2):518–521. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.2.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shah R, Roberson GH, Cure JK. Correlation of MR imaging findings and clinical manifestations in neurosarcoidosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(5):953–961. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scott TF. Neurosarcoidosis mimicry of MS: clues from cases with CNS tissue diagnosis. J Neurol Sci. 2021;429:117621. 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117621. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 99.Eurelings LEM, Miedema JR, Dalm V, van Daele PLA, van Hagen PM, van Laar JAM, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor for diagnosing sarcoidosis in a population of patients suspected of sarcoidosis. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223897. 10.1371/journal.pone.0223897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Paley MA, Baker BJ, Dunham SR, Linskey N, Cantoni C, Lee K, et al. The CSF in neurosarcoidosis contains consistent clonal expansion of CD8 T cells, but not CD4 T cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;367:577860. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Khoury J, Wellik KE, Demaerschalk BM, Wingerchuk DM. Cerebrospinal fluid angiotensin-converting enzyme for diagnosis of central nervous system sarcoidosis. Neurologist. 2009;15(2):108–111. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31819bcf84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bridel C, Courvoisier DS, Vuilleumier N, Lalive PH. Cerebrospinal fluid angiotensin-converting enzyme for diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;285:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fujisawa M, Koga M, Sato R, Oishi M, Takeshita Y, Kanda T. Spinal cord sarcoidosis in Japan: utility of cerebrospinal fluid examination and nerve conduction study for diagnosis and prognosis prediction. J Neurol. 2022;269(9):4783–4790. doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11113-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Grunewald J, Grutters JC, Arkema EV, Saketkoo LA, Moller DR, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):45. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bonham CA, Strek ME, Patterson KC. From granuloma to fibrosis: sarcoidosis associated pulmonary fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016;22(5):484–491. doi: 10.1097/mcp.0000000000000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Deng P, Krasnozhen-Ratush O, William C, Howard J. Concurrent LETM and nerve root enhancement in spinal neurosarcoid: a case series. Mult Scler. 2018;24(14):1913–1916. doi: 10.1177/1352458518771518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bathla G, Singh AK, Policeni B, Agarwal A, Case B. Imaging of neurosarcoidosis: common, uncommon, and rare. Clin Radiol. 2016;71(1):96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ginat DT, Dhillon G, Almast J. Magnetic resonance imaging of neurosarcoidosis. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2011;1:15. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.76693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wahed LA, Cho TA. Imaging of central nervous system autoimmune, paraneoplastic, and neuro-rheumatologic disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2023;29(1):255–291. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000001244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zalewski NL, Krecke KN, Weinshenker BG, Aksamit AJ, Conway BL, McKeon A, et al. Central canal enhancement and the trident sign in spinal cord sarcoidosis. Neurology. 2016;87(7):743–744. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bathla G, Watal P, Gupta S, Nagpal P, Mohan S, Moritani T. Cerebrovascular manifestations of neurosarcoidosis: an underrecognized aspect of the imaging spectrum. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(7):1194–1200. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bathla G, Abdel-Wahed L, Agarwal A, Cho TA, Gupta S, Jones KA, et al. Vascular involvement in neurosarcoidosis: early experiences from intracranial vessel wall imaging. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(6):e1063. 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 113.Tyshkov C, Pawate S, Bradshaw MJ, Kimbrough DJ, Chitnis T, Gelfand JM, et al. Multiple sclerosis and sarcoidosis: a case for coexistence. Neurol Clin Pract. 2019;9(3):218–227. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available for subscribed members to this journal or members of the American Academy of Neurology.