Abstract

Context:

Despite the known importance of culturally tailored palliative care (PC), American Indian people (AIs) in the Great Plains lack access to such services. While clinicians caring for AIs in the Great Plains have long acknowledged major barriers to serious illness care, there is a paucity of literature describing specific factors influencing PC access and delivery for AI patients living on reservation land.

Objectives:

This study aimed to explore factors influencing PC access and delivery on reservation land in the Great Plains to inform the development culturally tailored PC services for AIs.

Methods:

Three authors recorded and transcribed interviews with 21 specialty and 17 primary clinicians. A data analysis team of 7 authors analyzed transcripts using conventional content analysis. The analysis team met over Zoom to engage in code negotiation, classify codes, and develop themes.

Results:

Qualitative analysis of interview data revealed four themes encompassing factors influencing palliative care delivery and access for Great Plains American Indians: healthcare system operations (e.g., hospice and home health availability, fragmented services), geography (e.g., weather, travel distances), workforce elements (e.g., care continuity, inadequate staffing, cultural familiarity), and historical trauma and racism.

Conclusion:

Our findings emphasize the importance of addressing the time and cost of travel for seriously ill patients, increasing home health and hospice availability on reservations, and improving trust in the medical system. Strengthening the AI medical workforce, increasing funding for the Indian Health Service, and transitioning the governance of reservation healthcare to Tribal entities may improve the trustworthiness of the medical system.

Keywords: American Indian, Alaska Native, Palliative Care, Hospice, Barriers, Facilitators, Qualitative Research

Introduction

The importance and benefits of palliative care (PC) for patients and caregivers experiencing serious illness are well understood.(1–10) Over the past twenty years, organizations including the United Nations and World Health Organization have increasingly recognized PC as a human right, with the latter describing PC as a “global ethical responsibility.”(11–15) As the field has gained increased recognition, the number of PC specialized clinicians in the United States has also increased, though this growth has not been equitable. (16, 17) For rural and other medically underserved populations, access to the specialty trained PC workforce remains insufficient.(18–21) To overcome this barrier, growing emphasis has been placed on developing primary PC services in which primary clinicians are trained to assess patients’ basic palliative needs and smoothly coordinate consultations with PC specialists when needs become increasingly complex.(22, 23)

Clinicians and researchers in PC have also highlighted the importance of culturally congruent care in recent years.(24–28) The most recent Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality PC stress the intimate connection between cultural considerations and high-quality PC. The introduction specifically notes that the newest edition adds key references highlighting culturally inclusive best practices. The new edition also marks the first time the word “rural” appears in the NCP’s guidelines.(29)

The tandem of inequitable access to and cultural congruency of PC is highly relevant to American Indian and Alaska Native people (AI/ANs), particularly AIs living in rural reservation communities.(29–32) Across many of these AI communities, individuals rely on their own resilience and the strength and resilience of family caregivers and cultural networks to live well in the face of health inequities.(33, 34)

In the Great Plains, approximately 116,00 AI/ANs live on reservation lands held for 18 different Tribal Nations and communities, though this number likely reflects an undercount.(35–37) Most in these communities receive primary care from the Indian Health Service (IHS). Prior studies describe numerous barriers faced by the IHS, largely due to insufficient funding.(38–40) For subspecialty care, including oncologic care, IHS clinics in the Great Plains refer patients to external medical centers, some of which are hundreds of miles from patients’ homes.

Throughout these communities, serious illness disparities are stark. Nearly all reservations are located within high-poverty, rural counties—areas with the greatest mortality disparities in the United States.(41, 42) Common serious illnesses include heart disease, cancer, severe diabetes, liver disease, and lung disease. Compared to the White population, AIs experience significantly higher rates of mortality from each, a trend reflected in other geographic regions.(43, 44) Despite the enormous and disparate burden of serious illness, AIs in the Great Plains do not have consistent access to specialty PC, let alone PC services that are culturally tailored.

While clinicians caring for AI/ANs have long acknowledged delivery barriers including resource limitations within the IHS and adverse social determinants, there is no literature describing specific factors influencing PC for AIs living on reservations in the Great Plains.(40, 45, 46) To inform the development of community-based, culturally tailored PC interventions for this patient population, we interviewed primary and specialty clinicians to explore factors influencing PC access and delivery on reservation land.

Methods

Design and Recruitment

We conducted a qualitative study of individuals working at five regional cancer centers (specialty clinicians) and three IHS service units (primary clinicians) in the Great Plains to explore factors influencing primary and specialty PC for AI/ANs living in reservation communities. To recruit clinicians, we used a stratified random sampling strategy that divided potential participants by discipline and facility type (cancer center or local service unit). Specific stratifications differed slightly between cancer centers and IHS facilities. Specialty clinicians were stratified by facility size (large vs. small), discipline (physician, advanced practice provider [APP], nurse, social worker, chaplain), and subspecialty (PC, Medical Oncology, Gynecologic/Surgical/Radiation Oncology, Support Services). Discipline stratifications for participants from IHS sites included medical leader (directorship level or above), physician/APP, nurse, and allied health professional (AHP). AHP disciplines included administrator, pharmacist, and behavioral health. We conducted interviews until no new themes arose in interview data. Thirty-eight participants comprised the final sample (Table 1). This study received Institutional Review Board and Tribal Review Board approvals prior to enrollment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Participant Characteristics | n |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Total Providers | 38 |

| Specialty Providers | 21 |

| Primary Providers | 17 |

| Specialty Provider Characteristics | |

| Site Type | |

| Large Site | 17 |

| Small Site | 4 |

| Discipline | |

| RN | 3 |

| Physician | 9 |

| APP | 3 |

| Chaplain | 4 |

| SW | 2 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 |

| Female | 7 |

| Subspecialty | |

| Medical Oncology | 7 |

| Gyn/Surg/Rad Oncology | 5 |

| Palliative Care | 3 |

| Support Services (SW and Chaplain) | 6 |

| Primary Provider Characteristics | |

| Discipline | |

| Physician/APP | 8 |

| RN | 3 |

| Leader | 2 |

| AHP (Pharmacist, Administrator, Behavioral Health Specialist) | 4 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 4 |

| Female | 13 |

| Site | |

| Service Unit A | 3 |

| Service Unit B | 5 |

| Service Unit C | 9 |

RN = Registered Nurse, APP = Advanced Practice Provider, AHP = Allied Health Professional, SW = Social Worker

Data Collection

We conducted 36 in-depth qualitative interviews (average length 45 minutes) with 38 participants using semi-structured interview guides (supplemental file 1) designed to elicit reflection on the experience of caring for seriously ill AI patients. The number of interviews does not align with the number of participants because we conducted one group interview with a team of three clinicians at that team’s request. We held interviews between November 2020 and September 2021. Three authors (AES, MR, BR) conducted interviews over Zoom and transcribed them verbatim using transcription software (Otter.ai).

Analysis

We then entered transcript data into a qualitative data management and analysis software (NVivo, QSR International). A qualitative analysis team of 7 authors (AES, BRD, TD, GJ, MS, SP, MR, MI, KA) analyzed an initial set of 18 transcripts using conventional content analysis.(47) Individuals on this team were mixed in professional background and discipline and included physician and nurse researchers well-versed in qualitative analytical methods, research coordinators, and public health professionals. Our team included enrolled members of Great Plains Tribal Nations. The interdisciplinarity of both the analysis team and stratified participant sample facilitated verification of our findings via data and investigator triangulation.(48)

Individuals on the analysis team read through transcripts to inductively establish codes. All 7 members met via Zoom to discuss discrepancies between individuals’ coding and engage in code negotiation to reach a consensus.(49) Each team member applied the consensus coding scheme across the remaining transcripts. The entire analysis team met via Zoom to classify codes into categories to identify patterns, themes, and subthemes. Through group discussions, we refined a final set of themes and subthemes upon which the entire team agreed.

Results

The team identified four broad themes encompassing factors influencing PC access and delivery: 1) healthcare system operations, 2) geography 3) workforce elements, and 4) historical trauma and racism. Themes are discussed in detail below. Themes, subthemes, and representative quotations are also included in Tables 2–5.

Table 2.

Subthemes and Representative Quotations of Theme 1: Healthcare System Operations

| Theme 1: Healthcare System Operations | |

|---|---|

| Subtheme | Representative Quotation |

| Hospice and Home Health Supply | I would say most of them want to pass away at home, on their land with their people... (12, PC SW) Just a generalized statement, but many of the Native Americans want to be back at home if they’re going to pass away. (17, SW) If there were home hospice on each reservation, it would be a dramatic service, a huge, huge, huge service to keep people from having to travel to [the City] to help manage these things. (7, Surg/Gyn/Rad-Onc Physician) I feel like we needed more of like a hospice or home health kind of facility for those individuals, because a lot of times they get transferred to [the Cities], and they end up passing away over there where they would rather have been closer to home and closer to family on the reservation. (24, IHS AHP) We’ve had quite a few people that say, ‘bring me back to [Service Unit Name].’ That, you know, as part of our treaty agreement, we are given the right be in our own home setting. And if I can’t be in my very own home with people that can take care of me, then put me in the hospital. And there have been patients that have been here for an extended period of time [at end of life]. (34, IHS AHP) |

| Fragmentation of services | We have a very fragmented referral care system that impacts patients with serious illness. (20, IHS Physician) |

| Coordination Between Health Systems | |

| A couple weeks ago a patient asked me to call and discuss her pain meds with her primary doctor and nobody would even answer at the clinic. (3, Med-Onc APP) But the thing with IHS is that you never really get to talk to the same physician. Doesn’t matter how many times you call, you’re probably going to get someone else. (2, Med-Onc APP) What we’ve been trying to do with the referring facilities is opening communications to be able to transition and coordinate that care better. (35, IHS Leader) | |

| Coordination with Family and Tiospaye (Extended Family/Community) | |

| Coordination of care amongst providers [is a need], as well as communication amongst family members. (18, PC Physician) Family presence is probably one of the big [patient needs at end-of-life]. I mean, it’s important to most of our patients, but particularly the Native population. And family is not immediate family, It’s extended family… And so they want that those people around them. (19, Chaplain) | |

| Families are important, their traditions are important--family, and how people are related. And however they say they’re related, they’re related, you know, they’re connected. Biological or not, you just don’t question that. (22, Chaplain) | |

| Systemic | Health Records System |

| Inefficiencies | The electronic health record doesn’t cross communicate with any other systems like EPIC, which is the most common medical record used in the rest of the state. (20, IHS Physician) It’s a complicated system. It’s not EPIC... And when you have a complicated system, sometimes the patients that need to help most kind of fall through the cracks. (31, IHS Physician) The EHR sucks so bad that nobody knows what’s going on off the chart. (38, IHS Leader) The whole system and electronic health record dating back to ‘96 is archaic and cumbersome… And the people that are doing primary care are overworked because of the computer system. And they don’t have the time to see a patient. (36, IHS Physician) |

| Medication Workflows | |

| There are certain rules for prescribing things like pain medication, that’s tough to get around. You have to pass a drug test, you have to fill out a form, you can only prescribe a certain amount of narcotic pain medication at a time. It’s something you can’t do in one visit. (31, IHS Physician) Sometimes with the controlled substances, we’re pretty strict on not filling medications too soon… With palliative care, it would be nice if maybe those restrictions, you could say that there isn’t a restriction for comfort care patients. (33, IHS AHP) | |

Table 5.

Subthemes and Representative Quotations of Theme 1: Healthcare System Operations

| Theme 4: Historical Trauma and Racism | Representative Quotations: |

| Psychosocial stress with dying is, I feel, in some instances exacerbated by feeling and knowing that you’re not getting the quality of care that you deserve—that the patient is seeking care from a healthcare institution that has sort of violated their rights or caused worsening historical trauma or is receiving care from people that are white people that are part of settler colonialism. People feel a lot of times like they’re receiving compromised medical care, and that can make it more difficult. (15, IHS Physician) The low trust in the health system is a major barrier to discussing end of life care planning… And so I think it’s a very difficult conversation to have in a place where the health system has genuinely failed the community for so long. (20, IHS Physician) So the barrier that I think is really significant for anyone hospitalized here is… the fact that they are plucked out of their community with nothing but the clothes on their back, and brought to this hospital, and plunked down in a culture that has historically traumatized, culturally cut off the importance of their own history and culture. (21, Chaplain) Remember, this is people that go to Walmart and white people stare at them. They go to a store, and people follow them because they think that they’re gonna steal something. (33, IHS AHP) |

Theme 1: Healthcare System Operations

Participants endorsed the importance of delivering serious illness care to AIs close to home and described several aspects of the healthcare system that influence PC access and delivery. Subthemes include: 1) home health and hospice availability, 2) fragmentation of services, and 3) systemic inefficiencies.

Hospice and Home Health Availability

Clinicians cited a lack of hospice and home health services for patients living on reservations as the most significant barrier to providing home-based care to the seriously ill. Only one of the three IHS sites included in this study had access to hospice services. IHS clinicians described using inpatient beds at IHS facilities without hospice designation or services so patients could experience the last weeks of life closer to home. Nearly all participants emphasized the need for additional hospice and/or home health services to adequately address the desires of patients to receive serious illness care, including end-of-life care, in their home environment.

If I had a magic wand, I’d want a couple things. Number one, I would definitely want a hospice for the individuals here… And then the second thing that I would want is if we could have home health services too, so we could support those families that want their loved ones at home. Because culturally, that’s a huge thing. People want to be home. –35, IHS Medical Leader

Fragmentation of Services

Participants described an environment in which patients receive health-related services from at least four entities: IHS, regional health systems (cancer centers), Tribal health programs, and family caregivers. Communication gaps, particularly during care transitions, impeded clinicians’ abilities to manage palliative needs. As such, participants discussed the importance of effective care coordination across these entities. Clinicians specifically emphasized the importance of 1) coordination between health systems and 2) coordination with family and tiospaye (extended family/community).

Coordination Between Health Systems

Clinicians across facilities explained that coordination between the IHS and regional health systems created challenges to providing PC services. Multiple oncology specialists stated that communication with IHS is an obstacle to coordinating follow-up and managing pain.

The testing and the treatments can be very cumbersome to try and set up [with IHS]; a lot of phone calls… – 14, Oncology RN

On the IHS side, participants described similar challenges. They identified staffing limitations and fragmented health record systems as specific barriers to integrating care across facilities and disciplines, including PC.

We may not get those records and the orders from those [specialist] doctors up there. They might say, ‘Oh, well, we want to run these tests.’ But the tests will often have to be drawn here. And we don’t even know what tests were ordered. – 31, IHS Physician

Coordination with Family and Tiospaye

Clinicians across facilities expressed admiration for the strength of their patients’ families. Participants remarked that large numbers of loved ones will take it upon themselves to support the needs of seriously ill patients on reservations. Thus, coordinating with family providing day-to-day care was seen as key to addressing the needs of seriously ill patients.

There’s usually tons of family support… Family and friends that are willing to pitch in and do the day-to-day care needs. [The challenge for families at home] is really the ability to manage if there’s a tube anywhere, if there’s dressing changes that need to happen… – 4, PC Physician

Participants also reiterated that family is not always defined strictly, citing the Lakota concept of tiospaye (extended family/community). Clinicians discussed the importance of coordinating care and managing decision-making with extended family while delicately monitoring for potential discordance among large groups of loved ones.

I often consider [goals of care conversations] to be a pretty massive undertaking. I think, oftentimes, there will be a lot of family involved… And the concept that comes up when I’ve talked to patients and the community about this is the concept of tiospaye, which is the extended family unit, which was the historical decision-making unit for Lakota communities. So, I expect it’s going to be a tiospaye level discussion unless I hear differently. – 20, IHS Physician

Systemic Inefficiencies

Participants described two main inefficiencies within the health system that impeded the delivery of PC services: complex health record systems and cumbersome medication workflows.

Health Record Systems

Complications and fragmentations within the electronic health record (EHR) systems make it difficult for IHS clinicians to gather medical histories, document goals of care, and communicate with specialists. IHS participants emphasized the negative downstream consequences of a poor EHR system.

The E-chart is very difficult… it’s not easy to track the [goals of care] conversation. And I would say that this is a major problem. These sorts of problems are not just annoying and logistically difficult, they also contribute to a fatigue that someone might experience when their team doesn’t know what they stated as their wish. – 15, IHS Physician

Medication Workflows

Participants at both IHS facilities and cancer centers shared difficulties regarding pain medication workflows. Clinicians pointed to cumbersome policies and regulations (e.g., limits on dosing, pain committee approvals) around opioid prescription as barriers to pain control.

I think pain management as an outpatient is really hard because there’s so many strict rules about chronic opioids… I think the cancer patients get swept in with a lot of the other chronic pain patients. – 28, IHS Physician

Theme 2: Geography

Interviewees stressed the challenge of getting patients to appointments is the greatest barrier to providing health services, including PC, to patients living on reservations. Long travel distances, limited transportation, and inclement weather prevent patients from receiving PC at both IHS service units and regional cancer centers. Geographical barriers are exacerbated by poverty experienced within reservation communities.

They have a lot more barriers than other patients in other rural areas. Again, transportation... a large majority of our patients don’t have vehicles. They don’t have the financial means to go in to stay in [City Name]… – 35, IHS Leader

Theme 3: Workforce Elements

Clinicians highlighted several factors related to the medical workforce as significant influencers of PC for reservation-dwelling patients. Specific elements include: 1) care continuity, 2) inadequate staffing, and 3) cultural familiarity.

Care Continuity

Across IHS sites, participants described how much of the workforce is composed of contracted personnel who, though highly talented, are often transient, limiting their ability to build strong relationships with patients and their subspecialty teams. In addition, high turnover makes it difficult to disseminate PC-related knowledge (e.g., how to track goals of care) through the primary workforce. Participants stressed that strengthening care continuity was the key workforce element to enabling high quality PC. Both primary and specialty clinicians shared examples of how the lack of continuity negatively influenced their ability to manage symptoms, coordinate care, and build trust.

It’s easiest, of course, if the same person is asking, ‘so the Zofran wasn’t working last week, and now we just switched to Compazine. Has that been working better?’ When I haven’t seen a patient before, and I’m trying to figure out what changes someone else made, it’s hard to figure out what those changes are, let alone get to the bottom of how that’s impacting the patient. So, continuity of care actually really impacts the ability to treat physical symptoms. –15, IHS Physician Inadequate Staffing

Participants working at IHS facilities agreed that an important facilitator of care for those living on reservations is the strength and talent of IHS clinicians; however, participants commonly cited staffing shortages as a barrier to the provision of primary PC.

We’re chronically understaffed and underfunded, and I can go on and on about all the things that we are not… I can’t say enough wonderful things about our staff, and they do a great job, but yeah, there are barriers. –35, IHS Leader

Primary clinicians discussed the need for increased IHS funding that would allow IHS to recruit more personnel and to offer salaries that incorporate incentives for living remotely. IHS participants emphasized how increased staffing would allow them to focus greater efforts on building new programs, including primary palliative and home-based care.

I think it might be possible, especially as some of these clinics get a little stronger in terms of their staffing and other factors, to then really focus on access to certain services… like primary palliative care. – 20, IHS Physician

Participants representing cancer centers stated the limited volume of PC specialists is a barrier for all patients, including those from reservations.

Cultural Familiarity

Interviewees emphasized having familiarity with cultural values and maintaining cultural humility are important to providing PC. Clinicians who were members of the specific Tribal Nations they served reiterated how their AI identity facilitated care, particularly at end-of-life. AI clinicians noted having roots in the community builds trust, which facilitates goals of care discussions.

I think just being from here, knowing families sometimes helps [advance care planning] because sometimes you know who may be the person in the family who is the sounding board and to try to pull them in to pull the rest in. — 25, IHS RN

Non-AI participants also stressed the importance of cultural familiarity in the delivery of serious illness care. Numerous clinicians discussed the importance of AI-led PC interventions and expressed a desire for increased training on AI culture.

Theme 4: Historical Trauma and Racism

Participants reported that historical trauma and broken treaties have created widespread mistrust of the medical establishment among AI patients. Clinicians, especially those representing the IHS, articulated that the medical system’s failure to deliver adequate care to AI/AN people has negatively influenced their own ability to build relationships and hold important discussions at end-of-life.

Relative to other places I’ve worked, there’s an understandable distrust of the entire medical profession. And it’s not hard to find out why.… It’s tough to have a discussion regarding end-of-life care if you’re a patient and you feel like the doctor doesn’t care about you. – 31, IHS Physician

Many clinicians remarked that trauma was not solely historical, noting that poor care continuity and ongoing racism exacerbated mistrust, and in turn, impeded the delivery of PC services.

There is a lot of concern of racism and stuff up in [the City]. A lot of patients literally would rather risk their lives and stay than be sent back up there and get the specialty care that they need. —28, IHS Physician

You have a people, a culture, that has been abused for generations. And then when they get to like somebody or develop trust with a doctor—kaboom, they’re gone. —38, IHS Leader

Discussion

Improving the delivery of PC to AI and rural populations should be a national priority. In this qualitative study of 38 primary and specialty clinicians in the Great Plains, we identified four themes affecting this delivery including health system operations, geography, workforce elements, and historical trauma and racism. Several of these themes are not unique to reservation communities in the Great Plains. Long travel distances, fragmented services, and workforce instability are common barriers to the delivery of PC for rural populations across North America, regardless of racial and ethnic demographics.(19, 24, 50–53) Our results extend this prior literature by emphasizing the importance of these factors in historically marginalized communities and illustrating the compounding effect of historical trauma and ongoing discrimination.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The results of this study may not be generalizable to the AI/AN population beyond the Great Plains. While the barriers facing this population would appear to affect a broad spectrum of AI/AN communities (rurality, historical trauma and racism, underfunding of IHS), conducting similar assessments with stakeholders in Tribal Nations throughout the US is a critical next step towards addressing inequities and cultural congruency of PC services across the country.

Additionally, this project focused on AI patients with cancer, but there are many other serious illnesses where PC is beneficial.(54–58) Future work could consider incorporating a broader range of subspecialist perspectives.

A third limitation is that this study only includes clinicians’ perspectives on factors influencing PC and does not necessarily represent those of other community stakeholders. Of note, this study was conducted in conjunction with a similar qualitative study examining factors influencing PC from the perspective of patients, caregivers, local leaders, and traditional healers in the same region.

Lastly, we were unable to recruit participants evenly across the 3 service units. Though we aimed to sample one leader, APP/doctor, nurse, and AHP from each primary site, we were only able to recruit three clinicians at one site and two leaders in total. Despite uneven sampling, primary clinicians across sites repeated similar narratives and thematic saturation was achieved.

General Discussion

Our findings have several important implications. First, our data suggest that the travel burden associated with reservation geography represents a significant barrier to PC for Great Plains AIs. PC models that reduce the time and cost of travel can facilitate greater access to PC for this population. While advances in telemedical platforms capable of connecting specialists to rural communities provide an important opportunity to reduce these travel burdens and improve culturally congruent PC access, (25, 59) internet connectivity is limited in homes across reservations.(60) Furthermore, many patients lack access to internet-enabled devices. For telemedical advances to benefit patients on reservations in the Great Plains, IHS facilities will require expanded telehealth infrastructure to better serve individuals who struggle with connectivity at home. Additionally, given the demand on PC specialists nationally, increasing PC access for AI/ANs in the Great Plains will need to become a national priority to ensure robust specialist staffing for telehealth.

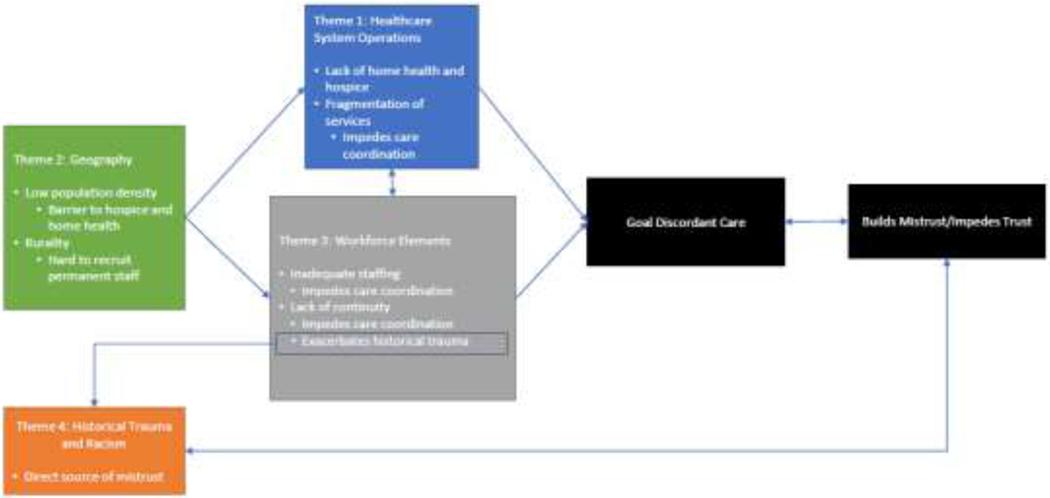

Second, our results suggest that effective PC delivery in these communities depends on addressing healthcare system mistrust. Most importantly, this requires improving the trustworthiness of the system by ensuring competent care and eliminating practices that raise concern about the healthcare system’s motives. Improving the system’s trustworthiness will require significant investments in the health care workforce so that all clinicians have access to ongoing cultural trainings as well as the electronic systems and tools necessary for patient-centered, integrated care. Though a recent and substantial increase in the IHS budget is an important step forward, translating this increased funding into improved care will require leadership committed to supporting innovation and front line engagement.(63) Restoring trust will require leaders to partner with Tribal Nations in these changes and to consider shared governance models or full Tribal governance of health care through the IHS Self-Governance Program.(64) Open dialogues that recognize the trauma US federal authorities and institutions have caused these populations and conversations that note the harms currently being perpetuated through systemic racism are needed to inform care such that services rectify rather than exacerbate these destructive forces.(65) Given that goal-concordant care enhances both patient/caregiver trust and the patient and clinician experience, improving the delivery of PC services should also contribute to retaining staff in the workforce and reducing healthcare system mistrust in these communities (Figure 1).(66, 67)

Figure 1.

Factors Influencing Palliative Care Impede the Formation of Trust

Finally, effective PC for reservation-dwelling patients in the Great Plains requires developing hospice and home health services. Dying on one’s own land in the presence of loved ones is of great cultural importance for AIs in the Great Plains. While many patients can rely on the strength of their tiospaye to address basic serious illness needs, dying comfortably at home is often not possible without an additional layer of home health and hospice services. Increased federal funding for the IHS may support development of these services; however, the standard hospice model will require adaptations for rural reservation settings. Increasing the capacity of IHS facilities for inpatient end-of-life care will be necessary to manage the needs of complex patients or individuals without a strong network of caregivers. One potential solution includes engaging local community health workers (CHWs) in the provision of PC. Partnering with CHWs who can conduct home visits and navigate families through a fragmented health system would help integrate care, reduce patient travel burdens, and bolster the AI/AN clinician workforce. While over a decade of research has shown that community members can play a key role in culturally tailored cancer navigation on Great Plains reservations(68, 69), recent studies from across the US indicate that collaborating with CHWs may be an effective way to provide culturally congruent palliative services beyond navigation (e.g., care planning, symptom assessment).(70–74) Additionally, having care delivered by members of a patient’s own community can increase trust.(75) Thus, formally engaging CHWs in PC represents a promising intervention to leverage the strengths of these remarkable communities.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Representative Quotations of Theme 2: Geography

| Theme 2: Geography | Representative Quotations |

| But, I mean, there’s not like palliative care in little towns across [State Name]. You have to come here for it. I think just transportation, distance is one of the hugest things. (16, Med-Onc APP) Where they’re at, the distance to a bigger facility, [is a barrier]. It’s a long, long ways, especially in the winter, to drive 200 miles to receive care... It really is a huge burden. (8, Med-Onc RN) Transportation is the biggest barrier, I would say, in [Reservation Name] in terms of managing some of these complex illnesses. A lot of people don’t have vehicles, a lot of people don’t have reliable access to borrowing vehicles. (29, IHS APP) You go up to [Reservation Name] in the winter, and it is bloody cold, and merciless, you know, cold wind. And when you’re chronically ill, it’s just hard. (37, IHS Physician) |

Table 4.

Subthemes and Representative Quotations of Theme 3: Workforce Elements

| Theme 3: Workforce Elements | |

|---|---|

| Subtheme | Representative Quotation |

| Care Continuity | I think the biggest problem is that there is no continuity of care, or very little… In IHS it’s probably 50% of the docs, the providers, are going to be locums tenens. (38, IHS Leader) When they’re on the reservation with IHS, they never see the same provider twice. And so when they go in with symptoms, and they get told to do this—well, they go in next time with the same symptoms, they get told something different. And it’s confusing and it’s just not consistent. (2, Med-Onc APP) I feel like we get different doctors and different people that are taking care of the person, and maybe one doctor’s like, ‘we’re gonna do this.’ And then the next doctor starts all kinds of other things that weren’t actually the plan. So sometimes I don’t think everybody’s on the same page. (32, IHS RN) And I think one of the things that kind of breeds mistrust here is lack of continuity, like not seeing the same person sequentially over time. (29, IHS APP) |

| Inadequate Staffing | I wish we had more resources. I wish we had more providers… we’re short on nurses, we are short on a lot of things. (31, IHS Physician) We have two public health nurses… And we only have 2 for 45,000 people. (33, IHS AHP) If we really wanted [PC] to see, say, every single stage four patient… I don’t think [PC specialists] would have the capacity to see every single patient. (9, Med-Onc Physician) |

| Increased IHS Funding → Increased Staffing → Facilitates PC Program Development | |

| You got to get more providers. Well, how do you get providers? You put money in... Nobody’s sticking around to start a program because of the chaos. There’s too much chaos and entropy to make a program run smooth. (36, IHS Physician) The other resource limitation that could probably be overcome to help with that would be if the IHS had more funding for care access and had enough providers that a provider could actually go and care for patients at home… I think it’s going to be hard to build strong programs in the hospitals if the hospital wards themselves are disrupted or understaffed. (20, IHS Physician) | |

| Cultural Familiarity | To have a culturally competent provider in their end-of-life care is paramount to appropriate care of life or end of life. (36, IHS Physician) When I meet with Native American patients, if I can talk a little bit about [my Native identity] and bring up those different family lines and names, people recognize them. And so there’s a lot of added trust, knowing that I am similar to them, even though I never lived on the reservation. (2, Med-Onc APP) Having sort of a Native first, or Native person led interventions and support, really feels critical to me… I imagine that we’d offer much stronger services if the people who were offering them were Lakota. (15, IHS Physician) I think what would help a lot and I would have appreciated is if I understood more of the Native American view on death and dying. (37, IHS Physician) |

Key Message.

This article describes a qualitative analysis of thirty-eight interviews conducted with primary and specialty clinicians caring for AIs in the Great Plains. Interviews were designed to explore factors influencing palliative care delivery and access for AIs living on reservation land. Healthcare system operations, geography, workforce elements, and historical trauma and racism were identified as themes representative of the major factors influencing palliative care access and delivery for AI patients living on reservation land.

Disclosures and Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Institutes of Health through funding from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA240080) and Cambia Health Foundation. The funders had no role in the design of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in writing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Editorial Comment Debra Parker Oliver, PhD, Associate Editor:

This important paper is appreciated as it provides important insight into a population whose needs and use of palliative care is not well known.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Alexander Soltoff, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Gray/Bigelow 7-740, Boston, MA 02114 USA.

Sara Purvis, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA USA.

Miranda Ravicz, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA USA.

Mary J. Isaacson, College of Nursing South Dakota State University, Rapid City, SD USA.

Tinka Duran, Community Health Prevention Programs, Great Plains Tribal Leaders Health Board, Rapid City, SD USA.

Gina Johnson, Community Health Prevention Programs, Great Plains Tribal Leaders Health Board, Rapid City, SD USA.

Michele Sargent, Walking Forward, Avera Research Institute, Avera Health, Rapid City, SD, USA.

J.R. LaPlante, American Indian Health Initiative, Avera Health, Sioux Falls, SD, USA.

Daniel Petereit, Walking Forward, Avera Research Institute, Avera Health, Rapid City, SD, USA.

Katrina Armstrong, Columbia Irving Medical Center, New York City, NY USA.

Bethany-Rose Daubman, Massachusetts General Hospital, Division of Palliative Care and Geriatric Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews [Internet] 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med 2008;11:180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:Cd007760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:Cd011129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Do specialist palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic literature review. Palliat Med 1998;12:317–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, et al. Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? Journal of pain and symptom management 2003;25:150–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:454–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabow M, Kvale E, Barbour L, et al. Moving upstream: a review of the evidence of the impact of outpatient palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1540–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, Rodin G, Tannock I. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. Jama 2008;299:1698–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.General Comment No. 14: The right to the highest attainable standard of health. In: Office of the High Commissioner for Human rights; Geneva, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2020. Available from: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ Accessed 1/19/2022,

- 13.Ezer T, Lohman D, de Luca GB. Palliative care and human rights: a decade of evolution in standards. Journal of pain and symptom management 2018;55:S163–S169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment throughout the life course. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy 2014;28:130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment throughout the life course. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2014;28:130–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Workforce Data and Reports. 2020. Available from: Available from http://aahpm.org/career/workforce-study#HPMphysicians. Accessed 1/19/2022,

- 17.America’s Care of Serious Illness: A State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation’s Hospitals. . In: New York, NY: Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlton M, Schlichting J, Chioreso C, Ward M, Vikas P. Challenges of Rural Cancer Care in the United States. Oncology (Williston Park) 2015;29:633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hospice Lynch S. and Palliative Care Access Issues in Rural Areas. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine® 2013;30:172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer DD, Winters CA. Palliative Care in Critical Rural Settings. Crit Care Nurse 2016;36:72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson CA, Pesut B, Bottorff JL, et al. Rural palliative care: a comprehensive review. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2009;12:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill. N Engl J Med 2015;373:747–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. Journal of palliative medicine 2011;14:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakitas M, Watts KA, Malone E, et al. Forging a New Frontier: Providing Palliative Care to People With Cancer in Rural and Remote Areas. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020;38:963–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elk R, Emanuel L, Hauser J, Bakitas M, Levkoff S. Developing and testing the feasibility of a culturally based tele-palliative care consult based on the cultural values and preferences of southern, rural African American and White community members: a program by and for the community. Health Equity 2020;4:52–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elk R, Gazaway S. Engaging Social Justice Methods to Create Palliative Care Programs That Reflect the Cultural Values of African American Patients with Serious Illness and Their Families: A Path Towards Health Equity. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 2021;49:222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Givler A, Bhatt H, Maani-Fogelman PA. The Importance Of Cultural Competence in Pain and Palliative Care. In: StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monette EM. Cultural Considerations in Palliative Care Provision: A Scoping Review of Canadian Literature. Palliat Med Rep 2021;2:146–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, Meier DE. National consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines. Journal of palliative medicine 2018;21:1684–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gebauer S, Knox Morley S, Haozous EA, et al. Palliative Care for American Indians and Alaska Natives: A Review of the Literature. J Palliat Med 2016;19:1331–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isaacson MJ, Lynch AR. Culturally Relevant Palliative and End-of-Life Care for U.S. Indigenous Populations: An Integrative Review. J Transcult Nurs 2018;29:180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jervis LL, Cox DW. END-OF-LIFE SERVICES IN TRIBAL COMMUNITIES. Innov Aging 2019;3:S667–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belcourt-Dittloff AE. Resiliency and risk in Native American communities: A culturally informed investigation, University of Montana, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oré CE, Teufel-Shone NI, Chico-Jarillo TM. American Indian and Alaska Native resilience along the life course and across generations: A literature review. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res 2016;23:134–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Census Bureau releases estimates of undercount and overcount in the 2010 Census. In: US Census Bureau, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lujan CC. American Indians and Alaska Natives count: The US Census Bureau’s efforts to enumerate the Native population. American Indian Quarterly 2014;38:319–341. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Community Profile. In: https://gptec.gptchb.org/data-and-statistics/data-products/: Great Plains Tribal Leader’s Health Board, 2016.

- 38.Artiga S, Ubri P, Foutz J. Medicaid and American Indians and Alaska Natives, Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warne D, Frizzell LB. American Indian health policy: historical trends and contemporary issues. Am J Public Health 2014;104 Suppl 3:S263–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cerasano HE. The Indian Health Service: Barriers to health care and strategies for improvement. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy 2017;24:421+. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Small area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE). 2021. Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/saipe/data.html. Accessed 1/26/2022,

- 42.Cosby AG, McDoom-Echebiri MM, James W, et al. Growth and Persistence of Place-Based Mortality in the United States: The Rural Mortality Penalty. Am J Public Health 2019;109:155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Espey DK, Jim MA, Cobb N, et al. Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health 2014;104 Suppl 3:S303–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Great Plains Area (GPA) Leading Causes of Death, 2005–2019. 2022. Available from: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/sarah.shewbrooks/viz/GPAMortalityDashboard/GPAMortality. Accessed 4/27/2022,

- 45.Cromer KJ, Wofford L, Wyant DK. Barriers to healthcare access facing American Indian and Alaska Natives in rural America. Journal of community health nursing 2019;36:165–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daley CM, Filippi M, James AS, et al. American Indian community leader and provider views of needs and barriers to mammography. J Community Health 2012;37:307–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research 2005;15:1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guion LA, Diehl DC, McDonald D. Triangulation: establishing the validity of qualitative studies: FCS6014/FY394, Rev. 8/2011. Edis 2011;2011:3-3. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. 2015.

- 50.Brundisini F, Giacomini M, DeJean D, et al. Chronic disease patients’ experiences with accessing health care in rural and remote areas: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2013;13:1–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keim-Malpass J, Mitchell EM, Blackhall L, DeGuzman PB. Evaluating Stakeholder-Identified Barriers in Accessing Palliative Care at an NCI-Designated Cancer Center with a Rural Catchment Area. J Palliat Med 2015;18:634–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soltoff AE, Isaacson MJ, Stoltenberg M, et al. Utilizing the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to Explore Palliative Care Program Implementation for American Indian and Alaska Natives throughout the United States. J Palliat Med 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Walsh J, Harrison JD, Young JM, et al. What are the current barriers to effective cancer care coordination? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bakitas M, Macmartin M, Trzepkowski K, et al. Palliative care consultations for heart failure patients: how many, when, and why? J Card Fail 2013;19:193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bekelman DB, Hutt E, Masoudi FA, Kutner JS, Rumsfeld JS. Defining the role of palliative care in older adults with heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2008;125:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kavalieratos D, Gelfman LP, Tycon LE, et al. Palliative Care in Heart Failure: Rationale, Evidence, and Future Priorities. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1919–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mounsey L, Ferres M, Eastman P. Palliative care for the patient without cancer. Aust J Gen Pract 2018;47:765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vermylen JH, Szmuilowicz E, Kalhan R. Palliative care in COPD: an unmet area for quality improvement. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:1543–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watts KA, Gazaway S, Malone E, et al. Community Tele-pal: A community-developed, culturally based palliative care tele-consult randomized controlled trial for African American and White Rural southern elders with a life-limiting illness. Trials 2020;21:672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Computer Martin M. and Internet Use in the United States: 2018. In: American Community Survey Reports: US Census Bureau, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mok E, Chiu PC. Nurse-patient relationships in palliative care. J Adv Nurs 2004;48:475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yedidia MJ. Transforming Doctor-Patient Relationships to Promote Patient-Centered Care: Lessons from Palliative Care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2007;33:40–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.IHS statement on allocation of final $367 million from CARES Act. In: https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/pressreleases/2020-press-releases/ihs-statement-on-allocation-of-final-367-million-from-cares-act/#:~:text=The%20Indian%20Health%20Service%20announced,respond%20to%20the%20coronavirus%20pandemic.: Indian Health Service, 2020.

- 64.Duran B, Oetzel J, Magarati M, et al. Toward Health Equity: A National Study of Promising Practices in Community-Based Participatory Research. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2019;13:337–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Benkert R, Peters RM, Clark R, Keves-Foster K. Effects of perceived racism, cultural mistrust and trust in providers on satisfaction with care. J Natl Med Assoc 2006;98:1532–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Comer AR, Hickman SE, Slaven JE, et al. Assessment of Discordance Between Surrogate Care Goals and Medical Treatment Provided to Older Adults With Serious Illness. JAMA Network Open 2020;3:e205179-e205179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving Goal-Concordant Care: A Conceptual Model and Approach to Measuring Serious Illness Communication and Its Impact. J Palliat Med 2018;21:S17–s27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krebs LU, Burhansstipanov L, Watanabe-Galloway S, et al. Navigation as an intervention to eliminate disparities in American Indian communities. Seminars in oncology nursing 2013;29:118–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petereit DG, Guadagnolo BA, Wong R, Coleman CN. Addressing Cancer Disparities Among American Indians through Innovative Technologies and Patient Navigation: The Walking Forward Experience. Front Oncol 2011;1:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Britt HR, JaKa MM, Fernstrom KM, et al. Quasi-Experimental Evaluation of LifeCourse on Utilization and Patient and Caregiver Quality of Life and Experience. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;36:408–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fischer SM, Kline DM, Min S-J, Okuyama-Sasaki S, Fink RM. Effect of Apoyo con Cariño (Support With Caring) Trial of a Patient Navigator Intervention to Improve Palliative Care Outcomes for Latino Adults With Advanced Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology 2018;4:1736–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patel MI, Sundaram V, Desai M, et al. Effect of a Lay Health Worker Intervention on Goals-of-Care Documentation and on Health Care Use, Costs, and Satisfaction Among Patients With Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology 2018;4:1359–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rocque GB, Pisu M, Jackson BE, et al. Resource Use and Medicare Costs During Lay Navigation for Geriatric Patients With Cancer. JAMA Oncology 2017;3:817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sedhom R, Nudotor R, Freund KM, et al. Can Community Health Workers Increase Palliative Care Use for African American Patients? A Pilot Study. JCO Oncol Pract 2021;17:e158–e167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sripad P, McClair TL, Casseus A, et al. Measuring client trust in community health workers: A multi-country validation study. J Glob Health 2021;11:07009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.