Abstract

Introduction

The number of people living with visual impairment is increasing. Visual impairment causes loss in quality of life and reduce self-care abilities. The burden of disease is heavy for people experiencing visual impairment and their relatives. The severity and progression of age-related eye diseases are dependent on the time of detection and treatment options, making timely access to healthcare critical in reducing visual impairment. General practice plays a key role in public health by managing preventive healthcare, diagnostics and treatment of chronic conditions. General practitioners (GPs) coordinate services from other healthcare professionals. More involvement of the primary sector could potentially be valuable in detecting visual impairment.

Methods

We apply the Medical Research Council framework for complex interventions to develop a primary care intervention with the GP as a key actor, aimed at identifying and coordinating care for patients with low vision. The development process will engage patients, relatives and relevant health professional stakeholders. We will pilot test the feasibility of the intervention in a real-world general practice setting. The intervention model will be developed through a participatory approach using qualitative and creative methods such as graphical facilitation. We aim to explore the potentials and limitations of general practice in relation to detection of preventable vision loss.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is obtained from local authority and the study meets the requirements from the Declaration of Helsinki. Dissemination is undertaken through research papers and to the broader public through podcasts and patient organisations.

Keywords: quality in health care, ophthalmology, glaucoma, primary care, qualitative research, public health

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Visual impairment and vision loss are important health problems, but the role of general practice in relation to detection of visual impairment remains unclear. Through the Medical Research Council framework for complex interventions, this study seeks to unfold the potentials and limitations of the general practitioners (GP’s) role concerning visual impairment and vision loss.

The study applies a participatory approach and explores the method of graphical facilitation to engage patients, relatives, GP’s and other health professionals in the development of the intervention.

The intervention will be tested in a real-world general practice setting in Denmark, which will ensure relevance and long-term acceptability of the intervention model.

Limitations include that the intervention is in the pilot phase and will need to be tested in a larger scale at a later stage before wider implementation can be initiated.

Introduction

It is estimated that 2.2 billion people have impaired vision, and of these, at least 1 billion people have a vision loss that could have been prevented or reduced by earlier detection or by access to treatment.1 The most common causes of moderate to severe visual impairment are uncorrected refractive errors, unoperated cataract, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy.2 Also in affluent welfare states such as Denmark—constituting the setting of this study—visual impairment is a problem.

The incidence of visual impairment increases with age, and due to the sociodemographical trajectory of an increasing elderly population, the prevalence of patients with visual impairment will increase.3 Timely access to healthcare has a major influence on the progression of eye conditions.1 2

The consequences of vision loss significantly affect the person’s quality of life,4–6 dependence7 and increases the risk of recurrent falls and fractures, which is a significant threat to mobility in old age.8–12 A YouGov poll showed that sight was by far the sensory function, people fear losing the most.13 Vision loss can result in worsened mental health,14 15 cognition16 17 and social functioning.4 Disease progression can be complicated by other chronic conditions18 and can complicate management of multimorbidity due to decreased self-care, ability to visit clinics and adherence to medication. Finally, vision loss can increase the risks of placement in nursing homes.19 20 Thus, visual impairment and loss has a great impact on the individual, their relatives,21 22 society in general and on the healthcare system.

General practice and visual impairment

General practitioners (GPs) handle preventive healthcare, diagnostics, treatment and care of chronic conditions as well as coordinate services from various healthcare professionals.23 In the Global North, the GPs handle the majority of all medical matters. A survey set in English general practice from 1998 concluded that eye problems, including undiagnosed glaucoma and AMD, were quite frequent among elderly patients consulting their GP.24 One study found that patients were more likely to have their eyes checked if their GP suggests it.25 In addition, an increased focus on eye health in at-risk populations in general practice is suggested to be more effective for early detection than broader screening programmes.26 27 However, a recent UK-based survey of GPs indicated that although up to 5% of the primary consultations were eye related, GPs ability to identify red flags was low.28 The literature points to a gap where, even though patients are in contact with their GP concerning symptoms related to their vision, an unidentified number of patients may suffer from unrecognised visual impairment that is not detected in general practice.

Collaboration across healthcare professions

Since vision problems are rarely detected in general practice, the need for research into how patients and health professionals collaborate to identify and manage visual impairment becomes a relevant matter. This is in line with a recent Cochrane review, which concludes that future research should look at optimised primary care-based vision screening interventions.29 Patients with visual impairment often have contacts with many different healthcare professionals.30 Therefore, it is important to incorporate collaboration across health professions and sectors in a GP intervention aimed at improving identification of patients with visual impairment.

Optometrists constitute an occupational group who may be the first line of contact for some patients who experience visual changes. Optometrists will in most cases operate independently without a formal collaboration with other health professionals such as GPs.31 Given the optometrists contact with the patients and level of equipment for measuring vision and evaluating the eye, they pose a potentially important resource when collaboration across healthcare professions is rethought and are therefore important to include in the study. Their commercial agenda may influence their work and this will be evaluated in the collaboration.32 33

Aim and objectives

In this study, we aim to develop a health intervention in a Danish general practice setting to improve the detection and care of visual impairment. The patient target group is middle-aged and older adults and their relatives, with GP’s constituting the primary professional target group. We define visual impairment broadly to be the patient experience of symptoms related to vision and findings identified by health professionals—such as reduced vision field—not yet experienced by the patient, but a serious threat to patient vision. Visual impairment is in this respect not connected to specific diagnoses, but as previously stated, we assume frequent eye diseases such as glaucoma and AMD will be well represented.

The overall aim of DETECT is thus to:

Develop an intervention in general practice aimed at identifying visual impairment among elderly patients with chronic conditions.

Test the feasibility of the intervention model in general practice with a focus on ensuring improved patient support and education.

Methods and analysis

The study will be conducted in Denmark and is thus inscribed in a Scandinavian health system with universal access to healthcare. The general health status in Denmark is relatively high, and as far as vision is concerned, the incidence of legal blindness has decreased along with improved treatment options.34 The average life expectancy has increased over the last 70 years, which is positive, but it also entails a rise in age-related sight-threatening eye diseases, such as glaucoma and AMD.35 Despite the decreasing incidence of legal blindness due to AMD, many patients are diagnosed late with irreversible vision loss. It seems relevant to diagnose eye diseases earlier and optimise the coordination of care. It is difficult to provide an exact number of people in Denmark who live with visual impairment. A national survey of health, quality of life and morbidity from 2007 shows that 3.8% of the population over 60 reported difficulties in reading a newspaper text,36 while the Danish Eye Association estimate that 50.000 people in Denmark above 60 years are blind or visually impaired37 (total population 60+: 1.554.54238).

In Denmark, the GP is the patient’s primary entry point to the healthcare system, and the GP treats 90% of all medical cases.23 All Danes are assigned to a default general practice, and as many as 80% consult their GP at least annually, with an increased frequency among patients aged 50 or older. People with chronic conditions are offered an annual health check at their GP. A Danish survey from 2019 showed that 82.4% of men and 86.7% of women had their vision measured at their GP within the last 3 years.39 However, these figures are from 2010 to 2017. In 2017, regulations regarding driving licenses were changed, resulting in vision being measured only every 15 years. This may result in a lower frequency of vision acuity measurements at the GP today, but from the 2017 figures we can assume that the practice of performing vision measurements during the annual consultation for older adults is a well-known procedure.

Ophthalmologists can diagnose, treat and carry out the necessary checks of, for example, glaucoma and atrophic AMD in the primary sector. If indicated, patients are referred to secondary care in the hospitals’ eye departments. Examples of referral indications may be neovascular AMD, proliferative diabetic retinopathy and medically uncontrollable glaucoma. At the hospitals, ophthalmologists work publicly funded and university hospital clinics have an obligation to do research within the field.

Consultations with the GP or ophthalmologist are tax financed and without an out-of-pocket fee to patients.40 41 Hospital-based eye clinics are also free of charge, but the patient must be referred by a primary sector ophthalmologist for treatment. In cases of acute vision loss or pain, patients can be seen directly in the emergency room and referred from there to the on-call ophthalmologist in the hospital eye department. Anyone can book an appointment with the ophthalmologist in the primary sector without a referral, but due to a low number of ophthalmologists compared with the increasing demand, it is often difficult to book a consultation within a reasonable time frame and geographical distance. On the other hand, the GP must be available to all patients inscribed in his/her practice and have an in-depth knowledge of the patient’s general health and condition. The GPs, therefore, seem to be in an ideal situation to identify visual impairment and coordinate the management.

It is estimated that around 2000 optometrists operate in Denmark (total population 5.8 million) and opticians shops can be found in most smaller cities, making it accessible even in rural areas to visit an optician shop.42 43 In most optician shops, it is free of charge to have vision tested. Many optometrists offer intraocular pressure measurements and fundus photographs as additional procedures for a fee. Optometrists are thus a professional stakeholder that we find interesting to explore further.

Study phases

We apply the Medical Research Council guidance on developing, testing and evaluating complex interventions.44 45 To operationalise the framework for complex interventions, we apply a temporal structure from the tradition of human-centred design to divide the project cycle into three main phases: (I) identify the problem, (II) develop the model and (III) test the feasibility of the model.46 Phase I+II focus on intervention development applying qualitative methods and phase III aims to first pilot test the intervention for feasibility and following implement it broader in a cohort study to measure effect.

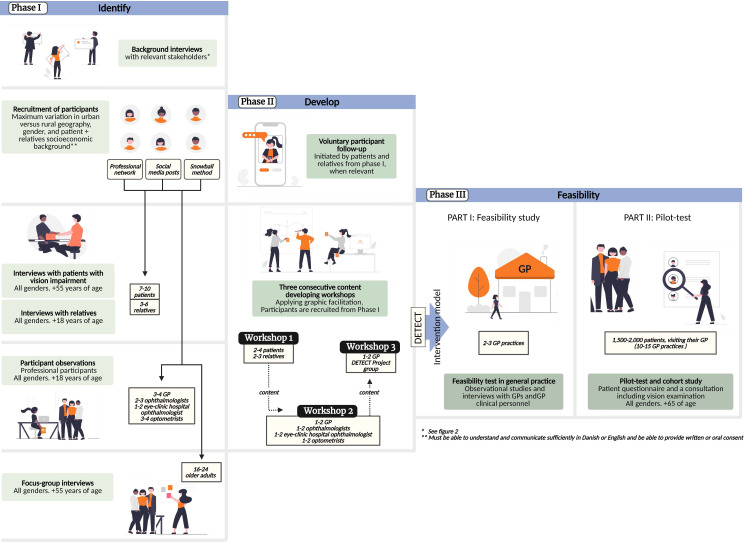

The intervention explores what patients, carers and professionals perceive as pivotal to improve regarding detection, navigating care and health services and support possibilities for people living with visual impairment. We are explicitly reflective on, how process and product are interwoven and to a very high extent dependent on the context it unfolds within.44 47 Following a structured and well-documented design process, we identify the changes made and insights produced (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

DETECT overall study design and participants engaged. Figure 1+2 were created with BioRender.com.

Phase I: identify—identifying key issues to address in the health intervention

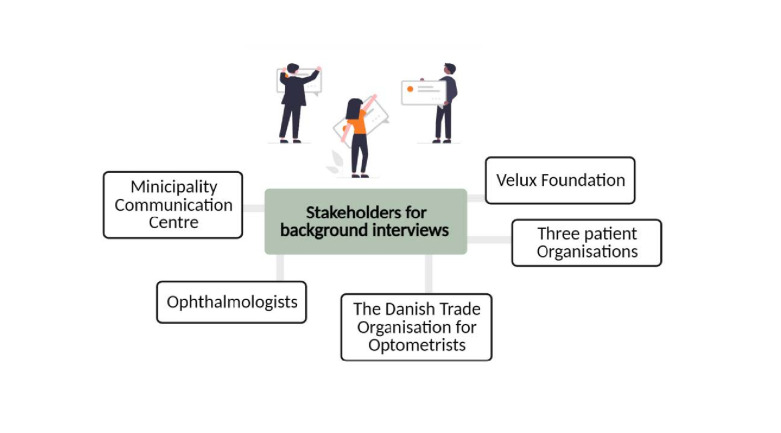

The aim of phase I is to explore the problem we are addressing. We will perform a literature search on detection of eye diseases in general practice and conduct background interviews with a broad selection of relevant stakeholders to help us map the current practice in detecting and diagnosing eye conditions across sectors in the healthcare system (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Stakeholders identified to participate in a background interview.

An essential element in human-centred design processes is to create understanding and empathy for the end-user48 49—in our case people living with visual impairment and their relatives. We aim to incorporate a wide spectrum of eye diagnoses and develop a model to identify and diagnose visual impairment that works from the onset of the patient’s early symptoms, such as stumbling over doorsteps, difficulties in reading, distorted vision or difficulties related to the transition from dark to light spaces and vice versa. The intervention aim of increased patient support also includes support of relatives, who carry a large part of the disease burden and may experience stress and depression due to their loved one’s visual impairment.50

Patient and public involvement in phase I

Patients, relatives and professionals will be involved by providing their perspectives in various stages of the study and codesign core elements of the model constituting the intervention. The patient engagement process is informed by a thorough report produced by the Danish Center for Social Science Research on older adults with visual impairment and vision loss.35 The report underlines the need for increased knowledge on how visual impairment affects patients’ every day life in all aspects. The experiences, needs, preferences, and values of patients and relatives will thus be explored.51 See figure 1 for an overview of the involvement of participants across the three project phases.

In phase I, we perform semistructured interviews with patients and relatives, preferably in their home to gain an insight in their experiences in the context in which they occur. Here, we focus on the patient journey from the time patients experience symptoms leading to a diagnosis and handling life afterwards with a diagnosis. After the interview, patients and relatives are encouraged to contact the researcher if they would like her/him to participate in, for example, a visit to the ophthalmologist or if they have further input or concerns at a later stage.

We will furthermore perform focus group interviews with older adults to investigate (1) the expectations to vision in old age and (2) which health professionals’ older adults identify as relevant when they experience vision changes. The focus group interviews supplement the interviews with patient and relative with a view to gain insight into the social norms and prominent attitudes towards visual impairment among older adults. The participants in the focus group interviews are asked to complete the validated Visual Function Questionnaire-25 to provide more individual knowledge about the participants own perception of their vision function.52

Through participant observations, we will generate knowledge on the everyday working environment and challenges that health professionals, private optometrists and communal workers navigate in concerning people with visual impairment.53

Phase II: develop—developing the intervention model

In phase II, we operationalise the insights from phase I. This will be done through three consecutive content-developing workshops using the creative method of graphic facilitation.54

Graphic facilitation is well suited when elaborating on ideas and problem-solving processes because it allows for a transparent process open to multiple agendas. The method can be relevant for redistributing power and expertise in a codesign activity and the physical product of the three content workshops will act as design principles for the intervention.55 56 CTS facilitates the workshops and we invite a graphic facilitator to analogue draw and write inputs from the participants on a wall-to-wall paper during the workshops. The graphical recordings from the three workshops constitute a collective overview of core elements to include in the intervention model (see description of specifics on the workshops below and figure 1 for details on participants). Choosing a visual method to engage participants could seem an unusual choice in a project focusing on visual impairment and vision loss. However, the participating patients are not blind. They live with a visual impairment, which poses a range of consequences and constraints in their every day life, but it does not prevent them from being able to participate in a graphical facilitated workshop. If needed, relevant aids will be provided—in example to enlarge the graphical recordings on a tablet

Flow of the three workshops: The graphic facilitator and project researchers develop a template for the workshops. Participants for the workshops are recruited among participants in phase I.

Workshop 1

In this workshop, the graphic facilitator engages patients and relatives to formulate a graphical recording on what is lacking in the identification, diagnosis and patient support concerning visual impairment.

Workshop 2

The focus for this workshop is to include perspectives from relevant health professionals in the design phase. The health professionals are asked to identify possibilities and barriers of an intervention concerning vision impairment in general practice, including a discussion on key eye examinations and measures that would be feasible in a general practice setting as well as to identify the most relevant eye diseases.

Workshop 3

Aims to synthesise the knowledge produced in the previous two workshops by formulating the specific activities, concrete consultation type and identify final intervention effect measurements. This also includes choosing the relevant guidelines for screening and diagnosing to apply in the intervention. Participants are GP’s and project researchers. Other stakeholders will be invited if relevant based on the insights from workshop 1+2.

Phase III: feasibility—feasibility test in general practice

Part 1: pilot test

The intervention model will be first be validated and adjusted accordingly by patient representatives and ophthalmologists. The model will then be tested in a general practice setting to establish face validity and adjust according to the experiences. The model must be clinically relevant and feasible for implementation in a clinical practice. Data production continues in this phase through observational studies and interviews with GPs to disseminate the experiences with the model in general practice and whether the model can be part of improved collaboration between health professionals.

Part 2: cohort study

Based on findings from the pilot test, we expand the intervention by including 10–15 GP practices in the Capital and Zeeland Region, Denmark to participate in testing the GP’s possibilities and barriers to detect visual impairment and vision loss. According to previous literature,36 we need to include 1500–2000 patients in general practice aged 65 or older to identify 150–200 with visual impairment. The practices will receive the developed intervention model and recruit in up to 18 months. Patients 65+ who consult their GP as part of an annual consultation for a chronic condition will be informed about the study in the waiting room and asked to complete a questionnaire based on the validated Visual functioning Questionnaire-25.52 The questionnaire measures the dimensions of self-reported vision-targeted health status that are most important to individuals who have chronic eye diseases. A dedicated staff or GP will examine the vision according to the guidelines formulated in the model. If visual impairment is detected, the patient will undergo further examinations assessed by an ophthalmologist.

The specifics of the examinations in general practice and at an ophthalmologist cannot be reported until the phases I+II have been completed, since these are to be developed in the codesign process. At present, we assume an ordinary vision test, visual fields and contrast vision as well as a function test could be included in the GP setting. We assume that measurement of the visual acuity, tonometry, macular and parapapillary optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans and fundus photographs could be part of the extended examinations at an ophthalmologist. An important outcome of phase II is thus detailed information on effect measurements, chosen guidelines and possibly a narrowed focus on specific eye diseases to address in the intervention. The results from the cohort study will function as a reference standard and allow us to study the prevalence of visual impairments as well as eye diseases and study predictor’s for visual impairment as well. Due to the Danish registers, it is possible to follow the cohort for a long period.57 This follow-up study is not part of the present project, but will be planned later.

Analysis

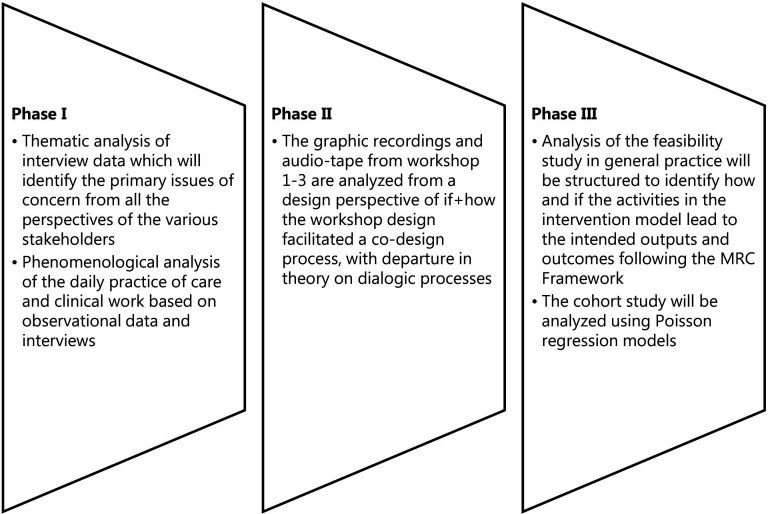

The analytical process will be carried out iteratively, which covers analytical steps taken between each of the three project phases to ensure appropriate adjustments in the design of the intervention model.58

All formal interviews from the study will be audio recorded and transcribed following a project guideline to ensure uniformity. The three phases will generate observations and informal talks, which will be documented through field notes and pictures. Details on the analytical steps are illustrated in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Analytical steps. MRC, Medical Research Council.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical issues will be a consideration at all levels of the study both when involving patients in the participatory design and during the cohort study. The study is registered in the records of research projects containing personal data at University of Copenhagen (J.nr: 514-0701/22-3000). It will be conducted according to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and general data protection regulations (GDPR). Ethical approval was waived by the Danish National Ethical Research Committee because no biomaterial is included in the study.

In data production, all participants will be asked to read and sign a consent form regarding their specific participation and kind of information, including how we will handle the information provided to us as, well as information on how to withdraw consent at a later stage. In the qualitative data production, we will produce photographical and graphical material, which requires further ethical reflections in terms of anonymisation.

The cohort study involves a risk of overdiagnostic practice due to the tests and screening involved.59 Any potential harms, overdiagnosis, labelling effect and consequences of receiving the intervention will be scrutinised during the study.60 Age-related visual impairment diagnoses including glaucoma and AMD meet the requirements for screening formulated by WHO.61

During the analysis, both benefits and harms of the intervention will be investigated and presented as results. Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals, preferably open-access. Patients, relatives and health professionals are invited in as coauthors where relevant. We will present our results in relevant fora nationally and internationally (conferences, annual meetings, etc). In addition, we will organise a symposium directed at stakeholders from health and social care sector and employers. The participants from the three content-developing workshops in phase II will be invited to participate in the symposia and share their experiences of being part of the research process. For communication to lay persons, we will produce a podcast on sensory loss in old age focused on vision and participate in the yearly Danish democracy and community festival ‘Folkemødet’, which has a specific focus on communicating public health science.

The proposed study is relevant for ensuring kind and empathic care62 63 with time to guide and comfort patients.64 This requires knowledge about how the patient experiences visual impairment as well as identification of the current challenges in the health services provided, which we aim to improve following the DETECT intervention. Specifically relevant in this study is the focus on general practice in relation to visual impairment, which is currently an understudied area.

Implications

Collectively, the output of intervention will help us understand, how to support and treat patients with impaired vision and to define an expedient role for general practice. In this respect, adding knowledge on the GP perspective will strengthen the feasibility of the intervention. The development of a codesigned intervention can have an important impact on the delivered quality in the diagnosis and management of patients with visual impairment in primary care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ann-Kathrin Lindahl Christiansen for making figure 1+2. We also wish to thank Professor Morten Dornoville de la Cour for contributing in discussions on clinical relevance and design of the cohort study.

Footnotes

Contributors: FBW, ABRJ, SR and CTS developed the original idea for the study. CTS wrote first draft of the protocol. CTS, ABRJ, SR, FBW, MHJ and OHM were primary in developing the methodological framework for the study. DB-H, KL and MK provided detailed information regarding clinical procedures and ophthalmological expertise. MHJ and FBW performed the initial literature search. All authors critically reviewed and revised the initial draft and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Velux Foundation, grant number: 869353.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World report on vision. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinmetz JD, Bourne RR, Briant PS, et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of Avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: an analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9:e144–60. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, et al. The burden of age-related macular degeneration: a value-based medicine analysis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2005;103:173–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Agecode Study Group, Hajek A, Brettschneider C, et al. Does visual impairment affect social ties in late life? findings of a multicenter prospective cohort study in Germany. J Nutr Health Aging 2017;21:692–8. 10.1007/s12603-016-0768-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamoureux E, Pesudovs K. Vision-specific quality-of-life research: a need to improve the quality. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:195–7. 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langelaan M, de Boer MR, van Nispen RMA, et al. Impact of visual impairment on quality of life: a comparison with quality of life in the general population and with other chronic conditions. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2007;14:119–26. 10.1080/09286580601139212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JC, Goldstein JE, Chan TL, et al. Characterizing functional complaints in patients seeking outpatient low-vision services in the United States. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1655–62. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swenor BK, Muñoz B, West SK. Does visual impairment affect mobility over time? the Salisbury eye evaluation study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:7683. 10.1167/iovs.13-12869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer MR, Pluijm SM, Lips P, et al. Different aspects of visual impairment as risk factors for falls and fractures in older men and women. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:1539–47. 10.1359/JBMR.040504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lord SR. Visual risk factors for falls in older people. Age Ageing 2006;35:ii42–5. 10.1093/ageing/afl085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crews JE, Chou C-F, Stevens JA, et al. Falls among persons Aged≥ 65 years with and without severe vision impairment—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:433–7. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6517a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng VL, Yu F, Lum F, et al. Risk of fractures following cataract surgery in Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA 2012;308:493–501. 10.1001/jama.2012.9014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen H. Of the five senses, a majority would Miss sight the most. 2018. Available: https://today.yougov.com/topics/health/articles-reports/2018/07/25/five-senses-majority-would-miss-sight-most

- 14.Kempen GIJM, Ballemans J, Ranchor AV, et al. The impact of low vision on activities of daily living, symptoms of depression, feelings of anxiety and social support in community-living older adults seeking vision rehabilitation services. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1405–11. 10.1007/s11136-011-0061-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rees G, Tee HW, Marella M, et al. Vision-specific distress and depressive symptoms in people with vision impairment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:2891–6. 10.1167/iovs.09-5080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin M, Gutierrez P, Stone K, et al. Vision impairment and combined vision and hearing impairment predict cognitive and functional decline among older women. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reyes-Ortiz CA, Kuo Y-F, DiNuzzo AR, et al. Near vision impairment predicts cognitive decline: data from the Hispanic established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:681–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53219.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep 2004;119:263–70. 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hajek A, Brettschneider C, Lange C, et al. Longitudinal predictors of Institutionalization in old age. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0144203. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Cumming RG, et al. Visual impairment and nursing home placement in older Australians: the blue mountains eye study. Ophthalmic Epidemiology 2003;10:3–13. 10.1076/opep.10.1.3.13773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanemoto T, Hikichi Y, Kikuchi N, et al. The impact of different anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment regimens on reducing burden for Caregivers and patients with wet age-related macular degeneration in a single-center real-world Japanese setting. PLoS One 2017;12:e0189035. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spooner KL, Mhlanga CT, Hong TH, et al. The burden of Neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a patient’s perspective. Clin Ophthalmol 2018;12:2483–91. 10.2147/OPTH.S185052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen KM, Andersen JS, Søndergaard J. General practice and primary health care in Denmark. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:S34–8. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reidy A, Minassian DC, Vafidis G, et al. Prevalence of serious eye disease and visual impairment in a North London population: population based, cross sectional study. BMJ 1998;316:1643–6. 10.1136/bmj.316.7145.1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ammary-Risch NJ, Huang SS. The primary care physician’s role in preventing vision loss and blindness in patients with diabetes. J Natl Med Assoc 2011;103:281–3. 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30288-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowe S, MacLean CH, Shekelle PG. Preventing visual loss from chronic eye disease in primary care: scientific review. JAMA 2004;291:1487–95. 10.1001/jama.291.12.1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein JD, Khawaja AP, Weizer JS. Glaucoma in adults—screening, diagnosis, and management: A review. JAMA 2021;325:164–74. 10.1001/jama.2020.21899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilduff C, Lois C. Red eyes and red-flags: improving ophthalmic assessment and referral in primary care. BMJ Qual Improv Report 2016;5:u211608. 10.1136/bmjquality.u211608.w4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke EL, Evans JR, Smeeth L, et al. Community screening for visual impairment in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;2018. 10.1002/14651858.CD001054.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harper RA, Gunn PJG, Spry PGD, et al. Care pathways for glaucoma detection and monitoring in the UK. Eye 2020;34:89–102. 10.1038/s41433-019-0667-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loughman J, Nolan J, Stack J, et al. Online AMD research study for Optometrists: Current practice in the Republic of Ireland and UK. Optometry in Practice 2011;12:135–44. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Townsend D, Reeves BC, Taylor J, et al. Health professionals’ and service users’ perspectives of shared care for monitoring wet age-related macular degeneration: a qualitative study alongside the echoes trial. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007400. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shickle D, Griffin M. Why don’t older adults in E Ngland go to have their eyes examined Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2014;34:38–45. 10.1111/opo.12100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Høeg TB, Ellervik C, Buch H, et al. Danish rural eye study: epidemiology of adult visual impairment. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2016;23:53–62. 10.3109/09286586.2015.1066396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anna Amilon, Maria Lomborg Røgeskov, Juliane Birkedal Poulsen, Anu Siren, Rikke Nøhr Brünner . Ældre MED Synstab (older adults with vision loss). VIVE, the Danish center for social research. 2021. Available: https://www.vive.dk/da/udgivelser/aeldre-med-synstab-15830/

- 36.Ekholm O, Kjøller M, Davidsen M, et al. Sundhed Og Sygelighed I Danmark & Udviklingen Siden 1987. 2007.

- 37.Øjenforeningen (the Danish eye Association magazine). n.d. Available: https://ojenforeningen.dk/

- 38.Danmarks Statistik (Danish Statistics) . Statistikbanken. n.d. Available: https://www.statistikbanken.dk/FOLK1AM

- 39.Sundhedsstyrelsen . Ældres Sundhed OG Trivsel. Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2019: 6–108. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krasnik A, Vallgårda S, Christiansen T, et al. Sundhedsvæsen Og Sundhedspolitik. Munksgaard Danmark 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wadmann S, Strandberg-Larsen M, Vrangbæk K. Coordination between primary and secondary Healthcare in Denmark and Sweden. Int J Integr Care 2009;9:e04. 10.5334/ijic.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Danish trade Organisation for Opticians. OM Optikerforeningen (about the Danish trade Organisation for Opticians). n.d. Available: https://www.optikerforeningen.dk/om-optikerforeningen/

- 43.Da Optikerne Blev Til Optometrister | Øjenforeningen (when Opticians became Optometrists | eye Association). n.d. Available: https://ojenforeningen.dk/artikler/optikerne-blev-til-optometrister

- 44.Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of medical research Council guidance. BMJ 2021;374:n2061. 10.1136/bmj.n2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemire S, Kwako A, Nielsen SB, et al. What is this thing called a mechanism? findings from a review of realist evaluations. New Directions for Evaluation 2020;2020:73–86. 10.1002/ev.20428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandholdt CT, Cunningham J, Westendorp RGJ, et al. Towards inclusive Healthcare delivery: potentials and challenges of human-centred design in health innovation processes to increase healthy aging. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:4551. 10.3390/ijerph17124551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Craig P, Di Ruggiero E, Frolich KL, et al. Taking account of context in population health intervention research: guidance for producers, users and Funders of research. 2018.

- 48.Bovaird T, Loeffler E. The role of Co-production for better health and wellbeing: why we need to change. In: Loeffler E, Power G, Bovaird T, et al., eds. Co-production of health and wellbeing in Scotland Governance International. Birmingham, UK, 2013: 20–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witteman HO, Dansokho SC, Colquhoun H, et al. User-centered design and the development of patient decision AIDS: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2015;4:11. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amilon A, Siren A. The link between vision impairment and depressive Symptomatology in late life: does having a partner matter Eur J Ageing 2022;19:521–32. 10.1007/s10433-021-00653-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: from Redesigning the system around the patient to Co-designing services with the patient. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2006;15:307–10. 10.1136/qshc.2005.016527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sørensen MS, Andersen S, Henningsen GO, et al. Danish version of visual function Questionnaire-25 and its use in age-related macular degeneration. Dan Med Bull 2011;58:A4290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spradley JP. Participant observation. USA: Waveland Press, 2016: 207. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandholdt CT, Srivarathan A, Kristiansen M, et al. Undertaking graphic Facilitation to enable participation in health promotion interventions in disadvantaged Neighbourhoods in Denmark. Health Promot Int 2022;37:ii48–ii47. 10.1093/heapro/daac034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Espiner D, Hartnett F. Innovation and graphic Facilitation. ANZSWJ 2016;28:44–53. 10.11157/anzswj-vol28iss4id298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hautopp H, Ørngreen R. A review of graphic Facilitation in organizational and educational contexts. Designs for Learning 2018;10:53–62. 10.16993/dfl.97 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The Danish health care system and Epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol 2019;11:563–91. 10.2147/CLEP.S179083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papoutsi C, Wherton J, Shaw S, et al. Putting the social back into Sociotechnical: case studies of Co-design in Digital health. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2021;28:284–93. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brodersen J, Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC. The benefits and harms of screening for cancer with a focus on breast screening. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2010;120:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonell C, Jamal F, Melendez-Torres GJ, et al. Dark logic’: Theorising the harmful consequences of public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:95–8. 10.1136/jech-2014-204671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.World Health Organization . Screening programmes: a short guide. increase effectiveness, maximize benefits and minimize harm. 2020.

- 62.Kristiansen M. The difference that kind and compassionate care makes. BMJ (Online) 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Montori VM. Turning away from industrial health care toward careful and kind care. Academic Medicine 2019;94:768–70. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pieterse AH, Stiggelbout AM, Montori VM. Shared decision making and the importance of time. JAMA 2019;322:25–6. 10.1001/jama.2019.3785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.