ABSTRACT

Bacteria employ multiple transcriptional regulators to orchestrate cellular responses to adapt to constantly varying environments. The bacterial biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) has been extensively described, and yet, the PAH-related transcriptional regulators remain elusive. In this report, we identified an FadR-type transcriptional regulator that controls phenanthrene biodegradation in Croceicoccus naphthovorans strain PQ-2. The expression of fadR in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 was induced by phenanthrene, and its deletion significantly impaired both the biodegradation of phenanthrene and the synthesis of acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs). In the fadR deletion strain, the biodegradation of phenanthrene could be recovered by supplying either AHLs or fatty acids. Notably, FadR simultaneously activated the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway and repressed the fatty acid degradation pathway. As intracellular AHLs are synthesized with fatty acids as substrates, boosting the fatty acid supply could enhance AHL synthesis. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that FadR in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 positively regulates PAH biodegradation by controlling the formation of AHLs, which is mediated by the metabolism of fatty acids.

IMPORTANCE Master transcriptional regulation of carbon catabolites is extremely important for the survival of bacteria that face changes in carbon sources. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) can be utilized as carbon sources by some bacteria. FadR is a well-known transcriptional regulator involved in fatty acid metabolism; however, the connection between FadR regulation and PAH utilization in bacteria remains unknown. This study revealed that a FadR-type regulator in Croceicoccus naphthovorans PQ-2 stimulated PAH biodegradation by controlling the biosynthesis of the acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals that belong to fatty acid-derived compounds. These results provide a unique perspective for understanding bacterial adaptation to PAH-containing environments.

KEYWORDS: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, FadR, fatty acids, acyl-homoserine lactones, Croceicoccus naphthovorans

INTRODUCTION

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), a class of persistent organic pollutants with two or more fused benzene rings, are widespread in the environment due to incomplete combustion and the pyrolysis of organic compounds (1). PAHs are well known to have carcinogenic, teratogenic, and mutagenic effects on human health (2). Therefore, the effective elimination and removal of PAHs from the environment is extremely important and has attracted extensive attention. The microbial biodegradation of persistent organic pollutants is known to have advantages in cleanness and lack of secondary pollution (3, 4). In bacteria, the biodegradation of PAHs is initialized via dihydroxylation, which is catalyzed by aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. The products are then degraded through the phthalate pathway or salicylic acid pathway, which is catalyzed by oxygenase, isomerase, aldoacetase, hydroxylase, and lyase. Finally, the products enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle for complete degradation (5). Although the PAH biodegradation pathways in bacteria have been clarified to an extent, the regulatory mechanisms underlying PAH biodegradation are still poorly understood.

Quorum sensing (QS), a cell-to-cell communication process, has been demonstrated to be involved in the regulation of PAH biodegradation (6–8). The LuxI/LuxR-type QS system is a common system in Gram-negative bacteria. The LuxI-type proteins synthesize acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs; QS signals) through linking acyl carrier protein (ACP)- or coenzyme A (CoA)-coupled fatty acids with S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) (9). The LuxR-type proteins are transcriptional factors that are responsible for sensing AHLs and subsequently modulating the gene expression (10–12). Notably, AHLs commonly bear saturated and/or unsaturated and, occasionally, oxygenated and/or hydroxylated acyl chains ranging in length from C8 to C18 that are derived from fatty acid metabolism (12–15). It has been suggested that fatty acids may play a role in PAH absorption by maintaining membrane fluidity (16, 17), but it remains unclear whether fatty acid metabolism affects PAH biodegradation.

The de novo biosynthesis of fatty acids is initiated with the condensation of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP, which is catalyzed by β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III (FabH) (18, 19). The intermediate metabolites then enter the fatty acid recycling pathway, which adds two carbon atoms each time (20). The FadR-type transcriptional factors, whose role has been extensively studied in Escherichia coli, are known to regulate fatty acid metabolism (21). As the largest subfamily of the GntR family transcriptional regulators, the FadR-type regulators are typically found to have a conserved N-terminal DNA-binding domain and nearly maximal divergence in the C-terminal effector-binding and oligomerization domain (22). FadR negatively regulates the expression of genes coding for proteins involved in fatty acid β-oxidation and transport (fad regulon) and positively regulates the enzymes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (fab regulon) (23). Notably, some studies have revealed that FadR is involved in a variety of physiological processes that could be important for bacteria to adapt to the environment. FadR in E. coli regulates the glyoxylate cycle via activating the transcriptional regulator IclR (24). DgoR, a FadR subfamily transcriptional regulator, acts as a repressor for d-galactose metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum (25). A GntR family transcriptional repressor in Bacillus subtilis sharing high sequence similarity with FadR in E. coli is believed to regulate gluconate metabolism (26). Another FadR-type regulator, LldR, was found to regulate l-lactate utilization in Corynebacterium (27). All of the evidence supports the idea that FadR plays an important regulatory role in the utilization of carbon sources. To date, the connection between FadR regulation and PAH utilization remains unclear.

Recently, we found that Croceicoccus naphthovorans strain PQ-2, a member of the family Erythrobacteraceae within the order Sphingomonadales, can utilize various PAHs, including phenanthrene, anthracene, fluoranthene, and pyrene. C. naphthovorans PQ-2 contains a plasmid (P1) that carries the necessary genetic information for PAH degradation (6). Our results showed that the LuxI/LuxR-type QS system of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 regulated phenanthrene biodegradation through controlling the PAH-degrading genes and increasing the cell surface hydrophobicity (6). Phenanthrene, with three fused benzene rings, is the smallest structural unit of carcinogenic PAHs (28). It is commonly used as a model compound for the investigation of PAH biodegradation (29, 30). In this study, a FadR-type regulator that positively regulates phenanthrene biodegradation by affecting the QS system in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 was identified. It was found that FadR activated fatty acid biosynthesis but inhibited fatty acid degradation, leading to changes in the production and profile of AHLs, which in turn regulated PAH biodegradation.

RESULTS

fadR expression is activated by phenanthrene.

In silico analyses suggested that the proteins putatively associated with the PAH biodegradation pathways in PQ-2 are encoded by the genes in two contiguous genomic regions flanked by transposase genes in plasmid P1 (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This pattern of gene organization is conserved in the Erythrobacteraceae family (for example, in Novosphingobium pentaromativorans US6-1 and Novosphingobium sp. strain HR1a) (31, 32). The genes encoding dioxygenases (AhdA1e and AhdA2e) involved in the first step of PAH biodegradation are located in the first putative transposon region (AB433_RS17940 to AB433_RS18020 [AB43 3_RS17940–RS18020]) (Table S1 and Fig. S1). In addition, the genes related to the degradation of salicylaldehyde and catechol are located in the second transposon region (flanked by transposase genes AB433_RS18030–RS18215) (Fig. S1). It is worth noting that the first putative transposon region also encodes the putative regulator AB433_RS17945, whose coding gene is directly adjacent to yrpB and cyp153A, which encode a putative nitronate monooxygenase and cytochrome P450, respectively. With an amino acid sequence similarity of 41.2%, the predicted structure of AB433_RS17945 is highly similar to the structure of FadR from E. coli (EcFadR) (Fig. S2). Accordingly, the protein encoded by AB433_RS17945 is named FadR in this study. Notably, the FadR protein in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 shares more than 90% identity in amino acid sequence with counterparts in some Sphingomonadales and Blastomonas species (17). In addition, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses showed that the C. naphthovorans fadR was cotranscribed with yrpB (Fig. 1A and 1B). The expression of yrpB and cyp153A in the wild-type (WT) and ΔfadR mutant strains (Table 1) in the nutrient-rich medium P5Y3 (6) was also tested by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR). The results showed that the transcription levels of both genes were significantly decreased in the ΔfadR strain (Fig. S3). These findings revealed that the FadR in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 could be involved in activating the expression of the yrpB and cyp153A genes.

FIG 1.

Phenanthrene induces the expression of fadR. (A) Location of the fadR and flanking genes in the P1 plasmid. Genes are drawn to scale. Three fragments, F1, F2, and F3, were amplified with gDNA and cDNA as templates. (B) The fadR gene is cotranscribed with the yrpB gene. C. naphthovorans PQ-2 was grown in P5Y3 medium to mid-log phase, and gDNA and cDNA were obtained as described in Materials and Methods. F1, F2, and F3 were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis. (C) Expression of the fadR gene was determined using RT-qPCR in the wild-type strain cultured in P5Y3 medium with 0, 100, or 200 mg/L phenanthrene. Cultures grown to mid-log phase were collected for analyses. Expression levels are presented as signal intensity ratios of the fadR gene to the 16S rRNA gene. (D) Activities of the fadR promoter in the wild-type strain of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 cultured in P5Y3 medium with 0, 100, or 200 mg/L phenanthrene were determined using a lacZ reporter system. Error bars show mean values ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. tumefaciens A136 (pCF218/pCF372) | Biosensor strain for medium-/long-chain AHLs | 33 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | Host strain for cloning | 34 |

| WM3064 | Donor strain for conjugation | 35 |

| C. naphthovorans strains | ||

| PQ-2 | Wild-type | 36 |

| ΔfadR mutant | Mutant of strain PQ-2 with fadR deletion | This study |

| ΔfadR1 mutant | Mutant of strain PQ-2 with fadR1 deletion | This study |

| ΔfadR2 mutant | Mutant of strain PQ-2 with fadR2 deletion | This study |

| ΔfabH mutant | Mutant of strain PQ-2 with fabH deletion | This study |

| ΔluxI mutant | Mutant of strain PQ-2 with luxI deletion | 6 |

| ΔfadR/PfadR mutant | pHGE-Ptac-fadR in ΔfadR background | This study |

| ΔfadR/PfabH mutant | pHGE-Ptac-fabH in ΔfadR background | This study |

| ΔfabH/PfabH mutant | pHGE-Ptac-fabH in ΔfabH background | This study |

| ΔluxI/PluxI mutant | pHGE-Ptac-luxI in ΔluxI background | This study |

| ΔluxI/PfadR mutant | pHGE-Ptac-fadR in ΔluxI background | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAK405 | Kmr, suicide vector for sphingomonads | 34 |

| pHGEI03 | Kmr, lacZ reporter vector | 37 |

| pHGE-Ptac | Kmr, IPTG-inducible Ptac expression vector | 35 |

| pHGEI03-PfadR | For measuring fadR promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PfadR1 | For measuring fadR1 promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PfadR2 | For measuring fadR2 promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PacpP1 | For measuring acpP1 promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PacpP2 | For measuring acpP2 promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PtraG | For measuring traG promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PfabH | For measuring fabH promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PfadD | For measuring fadD promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PahdA1e | For measuring ahdA1e promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PxylE | For measuring xylE promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PxylG | For measuring xylG promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PluxI | For measuring luxI promoter activity | This study |

| pHGEI03-PluxR | For measuring luxR promoter activity | This study |

| pHGE-Ptac-fadR | Inducible expression of fadR | This study |

| pHGE-Ptac-fabH | Inducible expression of fabH | This study |

| pHGE-Ptac-luxI | Inducible expression of luxI | This study |

To verify the involvement of fadR in the response to phenanthrene, a representative of PAHs, this work measured the transcription levels of fadR in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 cultivated in the nutrient-rich medium P5Y3 supplied with phenanthrene at different concentrations. The transcription levels of fadR in cells treated with 100 and 200 mg/L phenanthrene increased by 2- and 5-fold, respectively (Fig. 1C). To confirm this observation, this work assessed the activity of the fadR promoter with a lacZ reporter system. A fragment of approximately 500 bp located upstream from the coding sequence of fadR was amplified and placed in front of the promoterless lacZ gene within the multicopy plasmid pHGEI03 (37). The resulting vector was introduced into C. naphthovorans PQ-2. Cells grown with different concentrations of phenanthrene were collected at mid-log phase, and the promoter activity was examined by β-galactosidase assays. Consistently, the activity levels of the fadR promoter induced by 100 and 200 mg/L phenanthrene were approximately 1.5-fold and approximately 1.8-fold higher, respectively, than that of the control (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these data indicate that the expression of fadR can be induced by phenanthrene.

FadR positively regulates phenanthrene biodegradation.

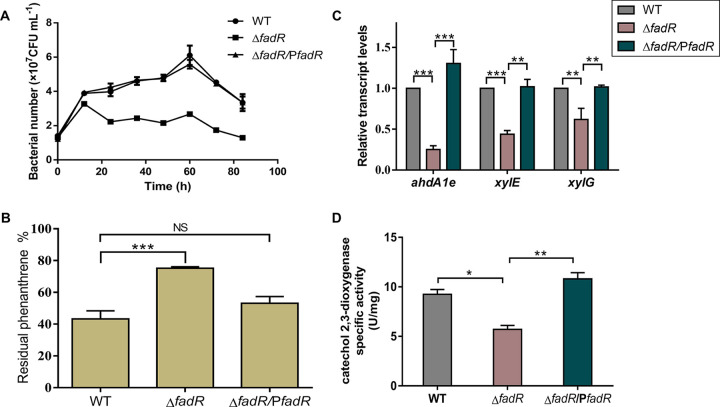

To explore the role of FadR in PAH biodegradation, this work constructed a fadR in-frame deletion strain (ΔfadR mutant) and determined its ability to degrade phenanthrene. In the nutrient-rich medium P5Y3 (6) and in defined medium with a nonaromatic carbon source (sucrose) as the sole carbon source, the growth of the ΔfadR strain was comparable to that of the WT (Fig. S4 and S5). However, in defined medium with phenanthrene as the sole carbon source, the growth of the ΔfadR strain was inhibited (Fig. 2A). In addition, the WT strain displayed a reddish-brown color due to the intermediate metabolites derived from phenanthrene consumption (Fig. S6). The residual phenanthrene was measured by using high-performance liquid chromatography. The fadR deletion significantly reduced the phenanthrene biodegradation, by approximately 50% (Fig. 2B). For genetic complementation, the expression of fadR was controlled by the IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible promoter Ptac (ΔfadR/PfadR strain) (35). In the presence of 0.2 mM IPTG, the residual phenanthrene concentration in the culture of the ΔfadR/PfadR strain was comparable to that of the WT, suggesting that the expression of fadR restored its PAH degradation ability (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

FadR activates phenanthrene biodegradation. (A) Growth curves of the relevant strains of C. naphthovorans PQ-2. WT, ΔfadR, and ΔfadR/PfadR strains were grown in minimal medium with 200 mg/L phenanthrene as the sole carbon source. (B) Percentages of residual phenanthrene in minimal medium that originally had 200 mg/L phenanthrene as the carbon source and was utilized by the relevant strains of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 for 84 h. (C) Impact of FadR on the expression of PAH-degrading genes. Relative transcription levels of ahdA1e, xylE, and xylG in the relevant strains of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 grown to mid-log phase (OD600 of approximately 0.5) in P5Y3 medium with 200 mg/L phenanthrene were measured using RT-qPCR. (D) Activities of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase in relevant strains of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 during growth. WT, wild type of C. naphthovorans PQ-2; ΔfadR, fadR deletion mutant; ΔfadR/PfadR, fadR-complemented ΔfadR strain. Error bars show mean values ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

Along with the fadR on the P1 plasmid, two fadR paralogs, namely, fadR1 and fadR2, in the chromosome of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 were also considered in this work. To test whether these two fadR paralogs were also involved in PAH biodegradation, the expression of the fadR genes in the WT strain cultured in P5Y3 medium supplemented with 100 or 200 mg/L phenanthrene was determined by using RT-qPCR. The results showed that the expression of fadR1 and fadR2 had a negligible response to the presence of phenanthrene (Fig. S7A). Mutant strains were also constructed, and the phenanthrene biodegradation was examined. It was found that the deletion of either fadR1 or fadR2 had a marginal effect on phenanthrene biodegradation (Fig. S7B).

To further determine whether the FadR from the P1 plasmid regulates the expression of the PAH-degrading genes, the transcription levels of three key genes involved in PAH biodegradation were analyzed in the nutrient-rich medium P5Y3 supplemented with 200 mg/L phenanthrene. These genes consist of ahdA1e, which encodes the α subunit of aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase, xylE, which encodes catechol 2,3-dioxygenase, and xylG, which encodes 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde dehydrogenase. The results showed that the transcription levels of these three genes decreased by 2- to 4-fold in the ΔfadR strain. This defect could be restored by expressing the fadR gene in trans (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the expression of traG (AB433_17710, encoding a conjugal transfer protein), located in the P1 plasmid but beyond the PAH biodegradation pathway, was not affected in the ΔfadR strain (Fig. S8). This work also determined the activities of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase in both the WT and ΔfadR strains. As expected, the enzyme activity in the ΔfadR strain was about 2 times lower than that in the WT (Fig. 2D). Based on these findings, it can be concluded that the FadR from the P1 plasmid positively regulates PAH biodegradation.

FadR affects the metabolism of fatty acids.

FadR has a dual role in regulating the metabolism of fatty acids in Gram-negative bacteria (20). FadR positively regulates the expression of the genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (for example, acpP and fabH) and negatively regulates the expression of the genes that participate in fatty acid β-oxidation (for example, fadD) (18). To determine whether FadR in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 is also involved in the metabolism of fatty acids, the transcription levels of acpP1, acpP2, fabH, and fadD were measured in the WT and ΔfadR strains. The results showed that fadR deletion decreased the expression of acpP1, acpP2, and fabH but increased the expression of fadD (Fig. 3A). The molecular profiles of fatty acids in the WT strain, the ΔfadR mutant strain, and a related complementary strain were measured using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The results showed that fadR deletion changed the profile of fatty acids (Table 2). Therefore, the FadR in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 also plays a dual regulatory role in the metabolism of fatty acids.

FIG 3.

Fatty acid metabolism affects the activity of promoters of genes involved in phenanthrene biodegradation. Activities of the promoters from acpP1, acpP2, fabH, and fadD strains in the wild-type and ΔfadR strain backgrounds were determined using a lacZ reporter system. Cells were cultured to mid-log phase in P5Y3 medium for analyses. Error bars show mean values ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

TABLE 2.

Fatty acid composition of C. naphthovorans strains

| Strain | Mean% ± SEM% |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C14:0 | C15:0 | C16:0 | C17:0 | C18:0 | C18:1 | |

| WTa | 3.41 ± 1.723 | 0.38 ± 0.023 | 51.22 ± 7.466 | 0.11 ± 0.083 | 1.698 ± 0.858 | 42.09 ± 0.412 |

| ΔfadR mutant | 9.60 ± 0.811 | 1.68 ± 0.008 | 50.80 ± 0.641 | 0.22 ± 0.010 | 0.261 ± 0.533 | 36.34 ± 0.190 |

| ΔfadR/PfadR mutantb | 2.95 ± 0.103 | 0.25 ± 0.008 | 52.85 ± 0.484 | 0.25 ± 0.200 | 1.159 ± 0.886 | 41.52 ± 0.308 |

WT, wild type.

Enzyme expression in the ΔfadR/PfadR strain was induced with 0.2 mM IPTG.

The FadR-regulated phenanthrene biodegradation is mediated by the AHL-type QS system.

It is well documented that the metabolism of fatty acids provides substrates for the synthesis of AHLs (38). Our previous study shows that the LuxI/LuxR-type QS system positively regulates PAH biodegradation in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 (6). Thus, it was speculated that FadR probably regulates phenanthrene biodegradation through affecting the QS system. To confirm this speculation, this work first examined the effect of FadR on AHL biosynthesis. The β-galactosidase activity was used to reflect the AHL concentration. Briefly, the supernatant of AHL producer C. naphthovorans PQ-2 was collected and added to the culture of the AHL sensor Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain A136, in which the β-galactosidase activity is positively correlated with the AHL concentration (15). The standard curve showed a dose dependence between the supernatant of PQ-2 and the β-galactosidase activity of A136 (Fig. S9). The measurements showed that fadR deletion resulted in an approximately 2-fold decrease in the extracellular level of AHLs, while the complementation of fadR in trans restored the level of AHLs (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the overexpression of fabH in the ΔfadR strain also partially restored the level of AHLs (Fig. 4A). Next, it was examined whether the AHL synthesis in the ΔfadR strain could be reversed by adding exogenous and endogenous fatty acids. C. naphthovorans PQ-2 can metabolize both butyrate (C4:0) and hexanoate (C6:0) (Fig. S10). As shown by the results in Fig. 4B, the addition of both butyrate and hexanoate increased the AHL biosynthesis. In addition, the AHL level in the culture supernatant increased with the expression of fabH, controlled by increasing the IPTG concentration (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that FadR-regulated fatty acid biosynthesis stimulates AHL accumulation.

FIG 4.

Fatty acid metabolism affects the biosynthesis of AHLs. (A) FadR positively controls the biosynthesis of AHLs. Strains were cultured in P5Y3 medium. The expression of fadR and fabH in the ΔfadR strain was induced by 0.2 mM IPTG. The ΔluxI strain was treated as the negative control. (B) Exogenous fatty acids promote the biosynthesis of AHLs. Fatty acids and sucrose were added to P5Y3 medium or not (NA, no addition). (C) Intracellular fatty acid accumulation from inducing the expression of fabH promotes the biosynthesis of AHLs. The expression of fabH in the ΔfabH strain was driven by IPTG. Cells were grown in P5Y3 medium to stationary phase. The supernatant was cultured with the biosensor strain A. tumefaciens A136 to mid-log phase, and the concentration of AHLs was determined based on the β-galactosidase activity (Miller units). Ptac, ΔfabH strain with an empty plasmid; Control, ΔfabH strain with an empty plasmid treated with 0.2 mM IPTG. (D) Effects of FadR and FabH on the profiles of AHLs. AHLs were extracted from cells harvested at stationary phase and identified using TLC. Hydroxylated C6-HSL (3-OH-C6-HSL) and hydroxylated C8-HSL (3-OH-C8-HSL) were the standard AHLs; dihydroxylated C8-HSL was the predicted AHL; S1, AHLs extracted from the wild type; S2, AHLs extracted from the ΔfadR strain; S3, AHLs extracted from the ΔfadR/PfadR strain; S4, AHLs extracted from the ΔfabH strain; S5, AHLs extracted from the ΔfabH/PfabH strain; WT, wild type of C. naphthovorans PQ-2; ΔfadR, fadR deletion mutant; ΔfadR/PfadR, fadR-complemented ΔfadR strain; ΔfabH, fabH deletion mutant; ΔfabH/PfabH, fabH-complemented ΔfabH strain. Error bars show mean values ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

Given that C. naphthovorans PQ-2 can produce more than one type of AHL (6), we wondered whether FadR also affects the composition of AHLs. To explore this possibility, the AHLs were extracted from C. naphthovorans PQ-2 and the profiles of the AHLs were identified using thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Two types of AHLs with similar concentrations were detected in the WT strain (Fig. 4D). The molecular formulas of these two signal molecules were C12H21NO4 with one hydroxyl group and C12H21NO5 with two hydroxyl groups (Fig. S11). The deletion of either fadR or fabH caused a substantial change in the ratio of the two signal molecules (C12H21NO4 and C12H21NO5) (Fig. 4D), which was reverted by complementing the corresponding gene in trans. Thus, FadR controls not only the content but also the molecular profile of AHLs.

Next, this work sought to determine whether the reduction of the phenanthrene biodegradation in the ΔfadR strain could be restored by intensifying the QS system. It is worth mentioning that the deletion of fadR also led to an approximately 50% reduction in the AHL content (Fig. 4A). According to the standard curve (Fig. S9), 3-OH-C8-HSL was added to the liquid cultures of ΔluxI and ΔfadR strains with final concentrations of 4 and 2 μg/mL, respectively, for equivalency to the level of the WT. The results showed that both the ΔluxI and ΔfadR strains regained the ability to degrade phenanthrene in the P5Y3 medium with 200 mg/L phenanthrene (Fig. 5A) and recovered their growth in phenanthrene-containing minimal medium (Fig. 5B). This work also examined the effect of the overexpression of fadR on phenanthrene biodegradation in the ΔluxI strain (the AHL-abolished strain). As shown by the results in Fig. 5C and 5D, the overexpression of fadR in the ΔluxI strain failed to restore its ability to degrade phenanthrene in P5Y3 medium with 200 mg/L phenanthrene or to recover the growth in phenanthrene-containing minimal medium. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that FadR-regulated phenanthrene degradation is mediated by the AHL-type QS system.

FIG 5.

Regulation of phenanthrene biodegradation by FadR relies on the QS system. (A) Exogenous AHLs accelerate phenanthrene biodegradation. Residual phenanthrene levels in cultures of the wild-type, ΔluxI, and ΔfadR strains in P5Y3 medium containing 200 mg/L phenanthrene with or without AHLs were measured. 3-OH-C8-HSL (one of the AHLs) at final concentrations of 4 μg/mL and 2 μg/mL was added for the ΔluxI and ΔfadR strains, respectively. (B) Growth curves of the wild type, ΔluxI, and ΔfadR strains grown in phenanthrene minimal medium with or without AHLs. 3-OH-C8-HSL (one of the AHLs) at final concentrations of 4 μg/mL and 2 μg/mL was added for the ΔluxI and ΔfadR strains, respectively. (C) Residual phenanthrene levels in cultures of the wild-type, ΔluxI, ΔluxI/PfadR, and ΔluxI/PluxI strains grown in P5Y3 medium containing 200 mg/L phenanthrene. (D) Growth curves of the wild-type, ΔluxI, ΔluxI/PfadR, and ΔluxI/PluxI strains grown in phenanthrene minimal medium. The expression of genes was induced by 0.2 mM IPTG. WT, wild type of C. naphthovorans PQ-2; ΔluxI, luxI (acyl-homoserine lactone synthase gene) deletion mutant; ΔfadR, fadR deletion mutant; ΔluxI/PfadR, fadR overexpression strain in the ΔluxI background; ΔluxI/PluxI, luxI-complemented ΔluxI strain. Error bars show mean values ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

FadR affects phenotypes associated with PAH biodegradation.

The loss of FadR decreased the AHL level (Fig. 4A), which might in turn affect the expression of luxI and luxR. To confirm this, this work measured the expression of luxI and luxR using a lacZ reporter system. The results showed that the expression of both luxI and luxR was reduced in the ΔfadR strain (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

FadR affects cell surface hydrophobicity and biofilm formation. (A) Impact of FadR on the expression of luxI and luxR. Promoter activities of luxI and luxR were determined using a lacZ reporter system. (B) Effect of FadR on cell surface hydrophobicity. The ΔfadR strain harboring an empty plasmid (ΔfadR/Ptac) was treated as the negative control. (C) Effect of FadR on biofilm formation. The ability to form biofilm was analyzed using crystal violet staining. The dyed biofilm has a maximum absorbance at 590 nm. WT, wild type of C. naphthovorans PQ-2; ΔluxI, luxI (acyl-homoserine lactone synthase gene) deletion mutant; ΔfadR, fadR deletion mutant; ΔluxI/PfadR, fadR overexpression strain in the ΔluxI background; ΔluxI/PluxI, luxI-complemented ΔluxI strain; ΔfadR/Ptac, ΔfadR strain harboring the empty plasmid. 3Error bars show mean values ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

Bacterial cell surface hydrophobicity and biofilm formation are closely related to the QS-mediated PAH biodegradation (6, 8). This work further tested the effects of FadR on cell surface hydrophobicity and biofilm formation. As shown by the results in Fig. 6B and C, both of these phenotypes were impaired by deleting fadR from the WT but restored by expressing fadR in trans. These results indicate that FadR modulates phenotypes associated with QS-regulated PAH biodegradation.

DISCUSSION

To date, the regulators involved in PAH biodegradation and their regulatory mechanisms remain elusive. Previous studies have shown that GntR family transcriptional factors can function as repressors in regulating the catabolism of aromatic compounds (39–41). In this study, it was elucidated that FadR, a GntR family regulator involved in the metabolism of fatty acids, positively regulated PAH biodegradation. This process was mediated by the AHL-type QS system in C. naphthovorans PQ-2.

The expression of fadR in C. naphthovorans PQ-2 can be induced by phenanthrene in the environment. As a result, FadR activates the pathway of fatty acid synthesis (FAS) and inhibits the pathway of fatty acid β-oxidation. The boosted fatty acid synthesis can increase the supply of substrate for AHL synthesis. Thus, the QS system of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 can be intensified, and this upregulates the expression of the genes involved in phenanthrene biodegradation. As a result, the utilization of phenanthrene in the environment will be accelerated (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Proposed model of FadR’s involvement in AHL biosynthesis and phenanthrene metabolism via regulation of fatty acid metabolism in C. naphthovorans PQ-2. FadR positively regulates the expression of genes coding for the enzymes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (fab regulon) but negatively regulates the expression of genes coding for the enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation (fad regulon). Fatty acid acyl-ACP is a precursor for the biosynthesis of AHLs. FadR stimulates the accumulation of AHLs and alters the AHL profile by activating fatty acid biosynthesis and repressing fatty acid β-oxidation. In turn, the activated QS system promotes the biodegradation of phenanthrene by activating the expression of relevant genes (for instance ahdA1e, xylE, and xylG). Blue arrows indicate gene clusters for phenanthrene degradation, red arrows indicate positive regulation, green T-bars present negative regulation, and dotted arrows present multistep reactions. FAS, fatty acid synthesis; QS, quorum sensing; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; OM, outer membrane; CM, cytoplasmic membrane.

The AHL-mediated QS system is widely conserved in Gram-negative bacteria. This system plays an important role in regulating aromatic compound degradation (6–8). For instance, the AHL-type QS system of P. aeruginosa positively regulates the catechol metacleavage pathway and accelerates aromatic degradation (8). The data obtained in this study also suggest that the AHL-mediated QS system of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 positively controls phenanthrene biodegradation. Because the supply of ACP- or coenzyme A-coupled fatty acids derived from fatty acid metabolism determines AHL biosynthesis (9, 42), the metabolism of fatty acids may be conservatively relevant to aromatic utilization in Gram-negative bacteria through affecting the AHL production and profile, highlighting the importance of fatty acid metabolism in maintaining cellular metabolism by regulating the carbon cycle.

Unlike many other bacteria that have only a single fadR, C. naphthovorans PQ-2 contains three fadR paralogs, one in the P1 plasmid and two others in the chromosome (fadR1 and fadR2). Notably, the FadR from the P1 plasmid positively determines phenanthrene biodegradation (Fig. 2), while the other two from the chromosome have a negligible effect on phenanthrene biodegradation (Fig. S7). These differentiated functions of the FadR proteins in phenanthrene biodegradation are probably attributed to their low amino acid sequence identities (29.2% for FadR versus FadR1, 31.1% for FadR versus FadR2, and 25.0% for FadR1 versus FadR2). The exploration of the function of the other two FadR paralogs is still in progress.

The members of the order Sphingomonadales are commonly found in soils and marine sediments polluted with PAHs, and they can degrade a wide range of PAHs (43). C. naphthovorans PQ-2 was isolated from a PAH-contaminated marine biofilm (6). This study characterized a GntR family regulator, FadR, involved in fatty acid metabolism, that positively regulated PAH biodegradation by mediating the AHL-type QS system in C. naphthovorans PQ-2. These findings support the speculation that the regulation of FadR-mediated fatty acid metabolism in carbon source utilization could be a survival strategy for Sphingomonadales to deal with PAH-containing environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli and A. tumefaciens strain A136 (pCF218/pCF372) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C and 30°C, respectively. C. naphthovorans strain PQ-2 was cultured in P5Y3 medium at 30°C (36). For the biodegradation assay, C. naphthovorans PQ-2 was cultivated at 30°C in marine minimal medium (6) supplemented with phenanthrene (200 mg/L) (6). Concentrations of 5 mg/mL of streptomycin and 50 μg/mL of rifampicin were added to medium for C. naphthovorans strains, 45 μg/mL of spectinomycin and 15 μg/mL of tetracycline were added to medium for A. tumefaciens A136, and 50 μg/mL of kanamycin (Km) and 0.3 mM DAP (2,6-diaminopimelic acid) were added to medium for E. coli strain WM3064.

In-frame deletion mutagenesis and genetic complementation.

Gene deletion mutants of C. naphthovorans PQ-2 were constructed by an rpsL-based tag-free gene deletion system (6, 36). Routinely, two fragments flanking the target gene were amplified using PCR with primers (Table S2, 5O/5I primers and 3I/3O primers) containing the restriction enzyme sites and linked together using fusion PCR based on a complementary overlap between the 5I primer and 3I primer. After digestion by two restriction enzymes designed on 5O/3O primers (Table S2, gene deletion), the released fused fragment was ligated with the same two-restriction-enzyme-digested suicide plasmid pAK405 by using T4 DNA ligase and transformed into E. coli WM3064. The resulting construct was transferred from E. coli into C. naphthovorans PQ-2 through conjugation. The transconjugants from the first homologous recombination event were selected on P5Y3 agar plates supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and verified by PCR using LF/SR primers and SF/LR primers in two reactions. Afterwards, the correct colonies were placed on P5Y3 agar plates supplemented with 5 mg/mL of streptomycin for selection of the transconjugants from the second homologous recombination event. The resulting colonies were restreaked on P5Y3 agar plates with 5 mg/mL of streptomycin or 50 μg/mL of kanamycin, if necessary. The kanamycin-sensitive colonies were then screened for deletion of the target gene through PCR using LF/LR primers. Finally, the deletion mutation was verified through DNA sequencing.

The mutant was genetically complemented using a broad-host-range plasmid, pHGE-Ptac (18). Routinely, the related gene was amplified using PCR with F/R primers (Table S2, control expression), digested using two restriction enzymes designed on F/R primers, and ligated with the same two-restriction-enzyme-digested, IPTG-inducible Ptac promoter. The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli WM3064, verified through DNA sequencing, and then transferred into the corresponding mutant through conjugation for phenotypic assay with IPTG.

Measurement of the residual phenanthrene.

The residual phenanthrene in medium was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (6, 44). Briefly, the sample was extracted with ethyl acetate and evaporated. Next, the extracts were dissolved in methanol, filtrated, and analyzed using HPLC. The column used for measurement was the InertsilODS-3 C18 column (4.6 by 250 mm with 5-μm particle size), and the mobile phase was methanol/water (80:20 [vol/vol]) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min using the Waters 2996 dual-wavelength detector at 254 nm.

Extraction and identification of AHLs.

The standard AHLs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical. The AHLs produced by C. naphthovorans strains were extracted from the culture supernatant with an equal volume of acidified ethyl acetate (45). Afterwards, the crude extracts were evaporated and dissolved into acidified ethyl acetate.

The separation of AHL extracts was performed on a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (TLC aluminum sheets, 20 cm by 20 cm, and silica gel 60 F254; Merck, Germany) using methanol-ultrapure water (60:40 [vol/vol]) as the mobile phase (46, 47). After chromatography and air drying, the TLC plate was covered with LB agar containing the reporter strain A. tumefaciens A136, which can detect medium- and long-chain AHLs. Then, X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) was spread on the plate and the AHL profile was analyzed after incubation at 30°C for 24 h.

The structure of AHLs was analyzed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) as described previously, with slight modifications (48). The crude AHL extracts were analyzed using an advanced benchtop tandem-quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX Triple TOF 5600+; Sciex Corp). The Agilent Extend C18 column (1.8 m, 2.1 by 50 mm) was used for chromatography, and the mobile phase consisted of solvent A (2 mM ammonium formate with 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). A gradient elution with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min was employed during the separation process. The effluent was ionized using electrospray ionization (ESI) and detected in the positive ion mode with the following conditions: ion source gas, 150 lb/in2; ion source gas, 250 lb/in2; curtain gas, 35 lb/in2; temperature, 550°C; ion spray voltage, +5,500 V. Selectivity was determined based on the tandem-MS (MS/MS) fragmentation of molecular [M+H]+ ions and relative intensity.

Analyses of AHL production.

In this study, the β-galactosidase activity was used to reflect the AHL concentration according to Miller’s method, with a slight modification (15). Simply, the sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 2 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected. Next, the AHL-containing supernatant was added to a culture of A. tumefaciens A136. Cells were grown in LB broth at 30°C to log phase. For measurement, cells were collected, washed twice, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The activity of β-galactosidase was determined by monitoring the color development at 420 nm using a Tecan Sunrise microplate and presented as Miller units.

Assay of the catechol 2,3-dioxygenase activity.

C. naphthovorans strains were cultivated in P5Y3 medium supplemented with 200 mg/L phenanthrene until reaching exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of approximately 0.6). Cells were harvested through centrifugation, washed, and resuspended with PBS. Cells were then broken through ultrasonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to obtain the supernatant for enzyme assay. Briefly, an enzyme reaction mixture containing 20 μL of catechol (50 mM), 960 μL of PBS (pH 7.5), and 20 μL of crude extract was prepared. The activity of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase was spectrophotometrically determined at 375 nm (OD375) according to the formation of 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde (2-HMS) (ε2-HMS = 36,000 M−1 · cm−1) at 30°C (49). The protein concentration of the crude extract was determined by the Bradford method (50). One unit of the catechol 2,3-dioxygenase activity was defined as the production of 2-HMS using 1 μg of crude enzyme extract in 1 h at 30°C.

Determination of the fadR operon.

Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) was employed to determine the organization of the fadR operon, as previously described (18). C. naphthovorans PQ-2 was grown in P5Y3 medium to mid-log phase. Total RNAs were extracted from cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and the RNAiso plus kit (TaKaRa). Forward and reverse (F/R) primers for RT-PCR are listed in Table S2. The cDNAs were obtained using a PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa) according to the product instructions and used as the template for PCR amplification. As a control, PCR with genomic DNA (gDNA) as the template was performed in parallel.

Analyses of the relative expression levels of genes.

RT-qPCR was performed to determine the expression levels of genes. Unless otherwise specified, cells were grown in P5Y3 medium with or without phenanthrene to mid-log phase. Total RNAs were extracted and reverse transcribed to obtain cDNAs for RT-qPCR, as described above. F/R primers for each gene for RT-qPCR are listed in Table S2. The relative abundance of each gene compared to that of the 16S rRNA gene was calculated based on the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method (6).

The expression levels of genes were also evaluated using plasmid pHGEI03 as a lacZ reporter system (51). Routinely, the fragment of approximately 500 bp containing the sequence upstream from the target gene was amplified with F/R primers (Table S2, lacZ reporter), digested using two restriction enzymes designed on F/R primers, and cloned into the two-restriction-enzyme-digested transcriptional-fusion vector pHGEI03 with a promoterless lacZ. The resultant construct was then verified through DNA sequencing and transferred into the corresponding C. naphthovorans PQ-2 strain through conjugation. Subsequently, cells were grown to mid-log phase, harvested through centrifugation at 4°C, and washed with PBS. Finally, the β-galactosidase activity was determined by monitoring the color development at 420 nm using a Synergy 2 Pro200 multidetection microplate reader (Tecan) and presented as Miller units.

Analyses of the cell surface hydrophobicity.

The cell surface hydrophobicity was measured as previously described (6) with some modifications. Briefly, the bacterial cultures were resuspended in PBS after incubation, and the OD600 values were recorded as OD0. Then, n-dodecane was added to extract the organic phase. The mixture was vortexed for 5 min, and phase separation allowed at room temperature. Subsequently, the OD600 was recorded as OD1. The values of cell surface hydrophobicity were calculated using the following equation: cell surface hydrophobicity (%) = [(OD0 − OD1)/OD0] × 100.

Assessment of the biofilm formation.

Biofilm formation was measured using crystal violet staining as previously described (6). The relevant strains were cultured in P5Y3 medium to early stationary phase (OD600 of approximately 0.8) at 30°C in 24-well flat-bottom polystyrene plates. The supernatant was removed, and the biofilm was washed twice with PBS. Afterwards, the adherent biofilm was stained with a 0.2% crystal violet solution for 10 min. After the removal of the excess dye with water, acetic acid (33%) was used to dissolve the crystal violet adhered to the biofilm. The absorbance of the crystal violet solution was measured at 590 nm.

Homology modeling and sequence alignment of FadR.

The amino acid sequences of EcFadR and FadR from C. naphthovorans were aligned through the UniProt Align online tool (https://www.uniprot.org/align). The software defined structure of FadR from C. naphthovorans was modeled by using the SWISS-MODEL online server (52). The predicted structure model of FadR was aligned with the structure of EcFadR by using PyMOL software (Fig. S2B).

Fatty acid composition analyses.

To determine fatty acid composition, cultures at mid-log phase grown in P5Y3 medium were collected through centrifugation and properly aliquoted. The fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were prepared by using trimethylsulfonium hydroxide (TMSH), the reaction mixture was dried under a stream of nitrogen, and the residual FAMEs were dissolved in 200 μL of ether/methanol (10:1 [vol/vol]) solution. Then, the FAMEs were identified by using gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) (Focus GC-DSQ II) on a capillary column (30 mm long by 0.25 mm in diameter). Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, and the column temperature was programmed to increase by 4°C/min from 140°C to 170°C and then by 3.5°C/min from 170°C to 240°C for 12.5 min (18).

Statistical analyses.

The data collected are displayed as the mean values ± standard errors of the means, and Student’s t test was performed for statistical significance. When the probability (P value) was less than 0.05, 0.01, or 0.001, the value was considered significantly (∗), very significantly (∗∗), or extremely significantly (∗∗∗) different, respectively. If the P value was larger than 0.05, the difference was not significant (NS). Unless otherwise indicated, the data presented for statistical analyses were obtained from triplicate experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2021YFA0909500), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grants number LY20C010002 and LQ22C010004), and the Scientific Research Project of the Education Department of Zhejiang Province of China (grant number Y202147033).

We declare that we have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Zhiliang Yu, Email: zlyu@zjut.edu.cn.

Ning-Yi Zhou, Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Qiu X, Wang W, Zhang L, Guo L, Xu P, Tang H. 2022. A thermophile Hydrogenibacillus sp. strain efficiently degrades environmental pollutants polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ Microbiol 24:436–450. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson SC, Jones KC. 1993. Bioremediation of soil contaminated with polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): a review. Environ Pollut 81:229–249. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(93)90206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu SH, Zeng GM, Niu QY, Liu Y, Zhou L, Jiang LH, Tan XF, Xu P, Zhang C, Cheng M. 2017. Bioremediation mechanisms of combined pollution of PAHs and heavy metals by bacteria and fungi: a mini review. Bioresour Technol 224:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crampon M, Bodilis J, Portet-Koltalo F. 2018. Linking initial soil bacterial diversity and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) degradation potential. J Hazard Mater 359:500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Shao Z. 2021. An intracellular sensing and signal transduction system that regulates the metabolism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in bacteria. mSystems 6:e00636-21. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00636-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu Z, Hu Z, Xu Q, Zhang M, Yuan N, Liu J, Meng Q, Yin J. 2020. The LuxI/LuxR-type quorum sensing system regulates degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons via two mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 21:5548. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangwani N, Kumari S, Das S. 2015. Involvement of quorum sensing genes in biofilm development and degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by a marine bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa N6P6. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:10283–10297. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6868-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yong YC, Zhong JJ. 2013. Regulation of aromatics biodegradation by rhl quorum sensing system through induction of catechol meta-cleavage pathway. Bioresour Technol 136:761–765. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Churchill ME, Chen L. 2011. Structural basis of acyl-homoserine lactone-dependent signaling. Chem Rev 111:68–85. doi: 10.1021/cr1000817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong SH, Frane ND, Christensen QH, Greenberg EP, Nagarajan R, Nair SK. 2017. Molecular basis for the substrate specificity of quorum signal synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:9092–9097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705400114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindemann A, Pessi G, Schaefer AL, Mattmann ME, Christensen QH, Kessler A, Hennecke H, Blackwell HE, Greenberg EP, Harwood CS. 2011. Isovaleryl-homoserine lactone, an unusual branched-chain quorum-sensing signal from the soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:16765–16770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114125108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickschat JS. 2010. Quorum sensing and bacterial biofilms. Nat Prod Rep 27:343–369. doi: 10.1039/b804469b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taghadosi R, Shakibaie MR, Masoumi S. 2015. Biochemical detection of N-acyl homoserine lactone from biofilm-forming uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infection samples. Rep Biochem Mol Biol 3:56–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziesche L, Bruns H, Dogs M, Wolter L, Mann F, Wagner-Döbler I, Brinkhoff T, Schulz S. 2015. Homoserine lactones, methyl oligohydroxybutyrates, and other extracellular metabolites of macroalgae-associated bacteria of the Roseobacter clade: identification and functions. Chembiochem 16:2094–2107. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefer AL, Greenberg EP, Oliver CM, Oda Y, Huang JJ, Bittan-Banin G, Peres CM, Schmidt S, Juhaszova K, Sufrin JR, Harwood CS. 2008. A new class of homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals. Nature 454:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nature07088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wick LY, Pelz O, Bernasconi SM, Andersen N, Harms H. 2003. Influence of the growth substrate on ester-linked phospho- and glycolipid fatty acids of PAH-degrading Mycobacterium sp. LB501T. Environ Microbiol 5:672–680. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyu Y, Zheng W, Zheng T, Tian Y. 2014. Biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by Novosphingobium pentaromativorans US6-1. PLoS One 9:e101438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng Q, Liang H, Gao H. 2018. Roles of multiple KASIII homologues of Shewanella oneidensis in initiation of fatty acid synthesis and in cerulenin resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1863:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taguchi F, Ogawa Y, Takeuchi K, Suzuki T, Toyoda K, Shiraishi T, Ichinose YA. 2006. A homologue of the 3-oxoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase III gene located in the glycosylation island of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci regulates virulence factors via N-acyl homoserine lactone and fatty acid synthesis. J Bacteriol 188:8376–8384. doi: 10.1128/JB.00763-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.My L, Ghandour Achkar N, Viala JP, Bouveret E. 2015. Reassessment of the genetic regulation of fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli: global positive control by the dual functional regulator FadR. J Bacteriol 197:1862–1872. doi: 10.1128/JB.00064-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan Z, Yoon JM, Nielsen DR, Shanks JV, Jarboe LR. 2016. Membrane engineering via trans-unsaturated fatty acids production improves Escherichia coli robustness and production of biorenewables. Metab Eng 35:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rigali S, Derouaux A, Giannotta F, Dusart J. 2002. Subdivision of the helix-turn-helix GntR family of bacterial regulators in the FadR, HutC, MocR, and YtrA subfamilies. J Biol Chem 277:12507–12515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henry MF, Cronan JE. 1991. Escherichia coli transcription factor that both activates fatty acid synthesis and represses fatty acid degradation. J Mol Biol 222:843–849. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90574-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gui L, Sunnarborg A, LaPorte DC. 1996. Regulated expression of a repressor protein: FadR activates iclR. J Bacteriol 178:4704–4709. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4704-4709.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arya G, Pal M, Sharma M, Singh B, Singh S, Agrawal V, Chaba R. 2021. Molecular insights into effector binding by DgoR, a GntR/FadR family transcriptional repressor of D-galactonate metabolism in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 115:591–609. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haydon DJ, Guest JR. 1991. A new family of bacterial regulatory proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett 79:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Georgi T, Engels V, Wendisch VF. 2008. Regulation of L-lactate utilization by the FadR-type regulator LldR of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Bacteriol 190:963–971. doi: 10.1128/JB.01147-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samanta SK, Singh OV, Jain RK. 2002. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: environmental pollution and bioremediation. Trends Biotechnol 20:243–248. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01943-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosal D, Ghosh S, Dutta TK, Ahn Y. 2016. Current state of knowledge in microbial degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): a review. Front Microbiol 7:1369. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muratova A, Pozdnyakova N, Makarov O, Baboshin M, Baskunov B, Myasoedova N, Golovleva L, Turkovskaya O. 2014. Degradation of phenanthrene by the rhizobacterium Ensifer meliloti. Biodegradation 25:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s10532-014-9699-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segura A, Udaondo Z, Molina L. 2021. PahT regulates carbon fluxes in Novosphingobium sp. HR1a and influences its survival in soil and rhizospheres. Environ Microbiol 23:2969–2991. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segura A, Hernández-Sánchez V, Marqués S, Molina L. 2017. Insights in the regulation of the degradation of PAHs in Novosphingobium sp. HR1a and utilization of this regulatory system as a tool for the detection of PAHs. Sci Total Environ 590–591:381–393. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLean RJ, Whiteley M, Stickler DJ, Fuqua WC. 1997. Evidence of autoinducer activity in naturally occurring biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Lett 154:259–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng Q, Sun Y, Gao H. 2018. Cytochromes c constitute a layer of protection against nitric oxide but not nitrite. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e01255-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01255-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Zeng Y, Feng H, Wu Y, Xu X. 2015. Croceicoccus naphthovorans sp. nov., a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons-degrading and acylhomoserine-lactone-producing bacterium isolated from marine biofilm, and emended description of the genus Croceicoccus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 65:1531–1536. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo Q, Dong Y, Chen H, Gao H. 2013. Mislocalization of Rieske protein PetA predominantly accounts for the aerobic growth defect of Tat mutants in Shewanella oneidensis. PLoS One 8:e62064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bi H, Christensen QH, Feng Y, Wang H, Cronan JE. 2012. The Burkholderia cenocepacia BDSF quorum sensing fatty acid is synthesized by a bifunctional crotonase homologue having both dehydratase and thioesterase activities. Mol Microbiol 83:840–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.07968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morawski B, Segura A, Ornston LN. 2000. Repression of Acinetobacter vanillate demethylase synthesis by VanR, a member of the GntR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiol Lett 187:65–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mouz S, Merlin C, Springael D, Toussaint A. 1999. A GntR-like negative regulator of the biphenyl degradation genes of the transposon Tn4371. Mol Gen Genet 262:790–799. doi: 10.1007/s004380051142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durante-Rodríguez G, Gómez-Álvarez H, Nogales J, Carmona M, Díaz E. 2017. One-component systems that regulate the expression of degradation pathways for aromatic compounds. In Krell T (ed), Cellular ecophysiology of microbe: hydrocarbon and lipid interactions. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20796-4_5-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziesche L, Rinkel J, Dickschat JS, Schulz S. 2018. Acyl-group specificity of AHL synthases involved in quorum-sensing in Roseobacter group bacteria. Beilstein J Org Chem 14:1309–1316. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.14.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Liu H, Dai J, Xu P, Tang H. 2022. Unveiling degradation mechanism of PAHs by a Sphingobium strain from a microbial consortium. mLife 1:287–302. doi: 10.1002/mlf2.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saravanabhavan G, Helferty A, Hodson PV, Brown RS. 2007. A multi-dimensional high performance liquid chromatographic method for fingerprinting polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their alkyl-homologs in the heavy gas oil fraction of Alaskan North Slope crude. J Chromatogr A 1156:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biswa P, Doble M. 2013. Production of acylated homoserine lactone by Gram-positive bacteria isolated from marine water. FEMS Microbiol Lett 343:34–41. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang M, Li S, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, Wu S, Zhang J, Hu Z, Ding M, Meng Q, Yin J, Yu Z. 2021. Stringent starvation protein A and LuxI/LuxR-type quorum sensing system constitute a mutual positive regulation loop in Pseudoalteromonas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 534:885–890. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu Z, Yu D, Mao Y, Zhang M, Ding M, Zhang J, Wu S, Qiu J, Yin J. 2019. Identification and characterization of a LuxI/R-type quorum sensing system in Pseudoalteromonas. Res Microbiol 170:243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Ding L, Li K, Schmieder W, Geng J, Xu K, Zhang Y, Ren H. 2017. Development of an extraction method and LC-MS analysis for N-acylated-L-homoserine lactones (AHLs) in wastewater treatment biofilms. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1041–1042:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klecka GM, Gibson DT. 1981. Inhibition of catechol 2, 3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida by 3-chlorocatecho. Appl Environ Microbiol 41:1159–1165. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.5.1159-1165.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bradford M. 1976. Protein reaction with dyes. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun Y, Meng Q, Zhang Y, Gao H. 2020. Derepression of bkd by the FadR loss dictates elevated production of BCFAs and isoleucine starvation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1865:158577. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.158577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, Heer FT, de Beer T, Rempfer C, Lorenza B, Lepore R, Schwede T. 2018. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download aem.00433-23-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.7 MB (765.3KB, pdf)