ABSTRACT

Modern microbial mats are potential analogues for Proterozoic ecosystems, yet only a few studies have characterized mats under low-oxygen conditions that are relevant to Proterozoic environments. Here, we use protein-stable isotope fingerprinting (P-SIF) to determine the protein carbon isotope (δ13C) values of autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic organisms in a benthic microbial mat from the low-oxygen Middle Island Sinkhole, Lake Huron, USA (MIS). We also measure the δ13C values of the sugar moieties of exopolysaccharides (EPS) within the mat to explore the relationships between cyanobacterial exudates and heterotrophic anabolic carbon uptake. Our results show that Cyanobacteria (autotrophs) are 13C-depleted, relative to sulfate-reducing bacteria (heterotrophs), and 13C-enriched, relative to sulfur oxidizing bacteria (autotrophs or mixotrophs). We also find that the pentose moieties of EPS are systematically enriched in 13C, relative to the hexose moieties of EPS. We hypothesize that these isotopic patterns reflect cyanobacterial metabolic pathways, particularly phosphoketolase, that are relatively more active in low-oxygen mat environments, rather than oxygenated mat environments. This results in isotopically more heterogeneous C sources in low-oxygen mats. While this might partially explain the isotopic variability observed in Proterozoic mat facies, further work is necessary to systematically characterize the isotopic fractionations that are associated with the synthesis of cyanobacterial exudates.

IMPORTANCE The δ13C compositions of heterotrophic microorganisms are dictated by the δ13C compositions of their organic carbon sources. In both modern and ancient photosynthetic microbial mats, photosynthetic exudates are the most likely source of organic carbon for heterotrophs. We measured the δ13C values of autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic bacteria as well as the δ13C value of the most abundant photosynthetic exudate (exopolysaccharide) in a modern analogue for a Proterozoic environment. Given these data, future studies will be better equipped to estimate the most likely carbon source for heterotrophs in both modern environments as well as in Proterozoic environments preserved in the rock record.

KEYWORDS: biogeochemistry, carbon stable isotope analysis, microbial mat, Middle Island Sinkhole, protein-stable isotope fingerprinting

INTRODUCTION

For the majority of life’s history on Earth, ecosystems were entirely microbial (1). Both ichnofossil evidence (2) and the presence of microbial textures in geologic features (2–6) suggest that microbial mats were widespread in the Proterozoic and early Paleozoic eras, even after the oldest reliably eukaryotic fossils appear in the rock record at 1.65 Ga (7). Using modern microbial mats as analogues, researchers have suggested that Proterozoic mat environments hosted the first origin of eukaryotes (8) and, specifically considering oxygenic cyanobacterial mats, sustained animal life in an otherwise low-oxygen environment (9). However, few studies on modern microbial mats include phototrophic mats in persistently low-O2 and/or sulfidic environments (10), which are the conditions that were likely widespread in coastal Proterozoic habitats (11, 12). To test evolutionary hypotheses invoking Proterozoic microbial mats, more research is necessary, specifically in low-O2 and/or sulfidic environments.

The submerged Middle Island Sinkhole (MIS) in Lake Huron, which is the focus of this study, has been previously identified as a potential analogue for benthic Proterozoic ecosystems (10, 13). Venting groundwater at the bottom of the MIS (23 m water depth) creates a stratified benthic layer with a lower temperature (7 to 9°C), lower concentrations of dissolved oxygen (0 to 2 mg L−1), and higher concentrations of dissolved sulfate (1,250 mg L−1) (13, 14) than those of the overlying lake water. Within cyanobacterial mats at MIS, organic carbon production is greater than oxygen production via oxygenic photosynthesis (OP), emphasizing the importance of anoxygenic photosynthesis (AP) and chemosynthesis as well as resulting in a net consumption of O2 within the benthic layer (13). Metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, and 16S rRNA profiles suggest that the mats are dominated by versatile cyanobacteria that are capable of OP, AP, and fermentation (13, 15). Additionally, the mats support an abundant and diverse set of Proteobacteria, including sulfate reducing bacteria (SRB) that are active during both night and day, including when the mat contains measurable dissolved oxygen from OP (10, 16).

Therefore, these Proterozoic analogue systems have intriguing patterns of sequential redox cycling. In a mat sampled from a different system (the “Main Spring” of the Frasassi cave outlet, Italy), (12) it was found that AP only occurred after sulfide was released via sulfate reduction by SRB, which itself only occurred after dissolved organic carbon was excreted via OP. In contrast to Lake Huron MIS, the dependence of both SRB and AP on the organic products excreted by OP made the Frasassi mat a net source of O2 (12). From these and similar studies, it appears that feedback between oxidizing and reducing chemical species may not have been the only factors determining whether cyanobacterial mats were net sources or sinks of O2 during the Proterozoic era, as has been previously suggested (e.g., [17]). In addition, it appears that the specific sequence of carbon transfer between organisms is important.

In modern ecosystems, networks of carbon transfer can be traced by adding 14C and/or 13C-labeled carbon sources to the surrounding environment (e.g., [18]), cultures of microbial isolates (e.g., [19, 20]), or incubations of environmental samples (e.g., [20]). For the modern analogue work to yield information that can be applied to the rock record, natural abundance carbon stable isotope compositions (δ13C) of preservable biomolecules are more appropriate. Typically, the δ13C values of ancient organic compounds are interpreted via comparisons to culture studies of modern microbial metabolism. For example, microbial biomass produced via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (reductive pentose phosphate) cycle using a Type I RuBisCO enzyme is depleted in 13C by 12 to 26‰, relative to dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), whereas biomass produced via the rTCA cycle is depleted by only 2 to 13‰ (21). In modern microbial mats, carbon transfer from autotrophs to heterotrophs occurs via the assimilation of metabolic intermediates that are excreted into the extracellular environment (e.g., [19, 22]). Since heterotrophic carbon assimilation does not fractionate organic carbon (23, 24), the δ13C value of heterotrophic biomass reflects the δ13C value of the specific organic compound assimilated. Depending on what is excreted by autotrophic metabolism, the heterotrophic biomass may be isotopically indistinguishable (e.g., exopolysaccharide [25]), relatively 13C-depleted (e.g., methane [26]), or relatively 13C-enriched (e.g., acetate, [23, 27]), relative to the autotrophic biomass. In theory, the δ13C composition of autotrophic and heterotrophic biomass, DIC, and excreted organic carbon compounds in modern microbial mats might follow a reproducible pattern, depending on the mode of carbon transfer in the mat. Characterizing these patterns in well-studied Proterozoic analogue systems may yield patterns that could be used to determine whether ancient microbial mat systems were likely sources or sinks of O2.

Previously, we used protein stable isotope fingerprinting (P-SIF) (28) to measure the δ13C values of whole proteins separated from an oxygenated, photosynthetic microbial mat in a terrestrial hydrothermal outflow channel in Yellowstone National Park (YNP), USA (25). The same proteins were also classified taxonomically via proteomics. Because the δ13C values of proteins are consistently offset from biomass δ13C values (23, 29), this approach yielded phylum-specific δ13C signatures for the primary autotroph and heterotrophic populations that were present in the mat at the time of sampling. The results indicated that Cyanobacteria and obligate heterotrophs, such as Actinobacteria, in this system have indistinguishable δ13C signatures. Concurrently, we measured the δ13C values for n-alkyl lipids as well as the monosaccharide moieties from exopolysaccharide (EPS). The glucose moieties in exopolysaccharide were equal in δ13C composition to both cyanobacterial and heterotrophic proteins, and the lipid pool was dominated by highly 13C-depleted fatty acids. From these data, we concluded that (i) producers and consumers in this system were sharing primary photosynthate as a common resource and (ii) Cyanobacteria were allocating most of their fixed carbon to exopolysaccharides. These results were consistent with those of prior studies on the fate of fixed carbon in microbial ecosystems within YNP which suggest that cyanobacterial glycogen is a key source of organic carbon to other mat-based organisms (e.g., [20]). However, it is unlikely that these results are applicable to benthic low-oxygen ecosystems with lower photon fluxes; under these conditions, Cyanobacteria are often light-limited and allocate a smaller portion of primary photosynthate to storage sugars (30).

For the present study, we hypothesized that Cyanobacteria in MIS microbial mats would allocate relatively less fixed carbon to exopolysaccharides than would Cyanobacteria in surface microbial mats, such as those of YNP. This may then imply that the resulting cyanobacterial exudates (i.e., heterotrophic anabolic carbon sources) should have variable δ13C compositions and should affect the signatures of heterotrophic consumers. To test this hypothesis, we measured the δ13C composition of mat exopolysaccharides and fatty acids as well as the protein δ13C values of autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic organisms in MIS.

RESULTS

Protein taxonomic identifications.

A P-SIF analysis was conducted on sample LH47. The SAX fractions 3 to 16 were chosen for further analysis using the integrated spectral absorbance of the reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) signal at 280 nm as well as criteria from prior work (28). 6% percent (43/672) of the RP-HPLC fractions contained identifiable peptide sequences, yielding 1,188 unique bacterial proteins (Table S1). Of these, 411 proteins were assigned to Cyanobacteria, 395 to Proteobacteria, 113 to Chloroflexi, 50 to Bacillariophyta, 16 to Bacteroidetes, 5 to Spirochaetes, 5 to Thermotogae, and all others (193 proteins) to phyla containing 4 or fewer unique protein hits or to unclassified sources (Table S2). The mean and median numbers of unique peptides that were used to classify each protein were 2.7 and 2, respectively.

Table 1 contains our estimates for the relative abundance of microbial groups, as determined via the summed integrated peak areas of peptides assigned to proteins. Mohr et al. (2014) calculated a ± 20% root-mean-square error for the P-SIF abundance estimates via the analysis of known mixtures of cultured organisms (Fig. S12 from [28]). Since our relative abundance estimates for Proteobacteria and Cyanobacteria overlap within error, we are unable to definitively say which of these two phyla dominated the microbial community at the time of sampling. As discussed for a previous P-SIF data set (25), label-free protein quantification methods are only semiquantitative (31). Furthermore, while Cyanobacteria and Proteobacteria have relatively similar median protein contents (43 and 48% dry weight, respectively; [32]), the filamentous Cyanobacteria present at MIS have significantly higher biomass contents than do the associated bacteria (e.g., Fig. 1 from [33]) As such, it is likely that we are underestimating the cyanobacterial abundance in particular by using this method. We can compare our estimated relative abundances to the relative abundances of 16S rRNA gene sequences in a flat-mat sample collected from the sample location in August of 2017 (the same month as our sampling): 16% Bacteroidetes, 29% Cyanobacteria, 42% Proteobacteria (28% Gammaproteobacteria, 9.9% Deltaproteobacteria, 1.3% Epsilonproteobacteria and other Proteobacteria), 4.4% Chloroflexi, 2.0% Spirochaetes, and 1.7% Verrucomicrobia, with the rest of the community being composed of unclassifiable bacteria and other phyla, each contributing <1% (34, 35). We recognize that the copy numbers of 16S rRNA genes in particular are variable among bacterial phyla (36). Nevertheless, these data broadly support our estimate for an ecosystem dominated by both Proteobacteria and Cyanobacteria as well as suggest a relatively large contribution of Bacteriodetes to the “Remainder” category.

TABLE 1.

Phylogenetic composition of sample LH47, as estimated by the summed integrated peak area of the peptides assigned to the proteins

| Phylum | Summed peak area of peptides | Abundance by peptide peak area (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanobacteria | 1.10 × 1010 | 29.1 |

| Proteobacteria | 1.75 × 1010 | 46.3 |

| Chloroflexi | 1.79 × 109 | 4.7 |

| Bacillariophyta | 7.39 × 108 | 2.0 |

| Bacteroidetes | 1.23 × 109 | 3.2 |

| Spirochaetes | 8.35 × 107 | 0.2 |

| Thermotogae | 1.45 × 108 | 0.4 |

| Acidobacteria | 5.87 × 106 | 0.0 |

| Chlorobi | 5.61 × 106 | 0.0 |

| Unclassified | 5.33 × 109 | 14.1 |

| Classes within Proteobacteria | ||

| Alpha | 1.93 × 108 | 1.1 |

| Beta | 6.39 × 107 | 0.4 |

| Delta | 1.15 × 1010 | 65.4 |

| Epsilon | 2.22 × 107 | 0.1 |

| Gamma | 4.82 × 109 | 27.5 |

| Other | 9.68 × 108 | 5.5 |

Protein carbon isotopic compositions.

20% (133/672) of the RP-HPLC fractions contained enough carbon for isotopic measurement. Of these, all but one had a standard deviation of <2.0‰ and were used in subsequent analyses. The average standard deviation of triplicate δ13C measurements for the protein fractions was 0.7‰ for the whole data set and 0.5‰ for the most abundant 50%, as determined using the IRMS peak area (Table S3). These values represent average measurement errors that are lower than the population standard deviation (1.6‰), indicating some degree of true variability among the protein δ13C values (Table S3). The resulting protein fraction δ13C values were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test, P = 0.014), with a mean of −24.6 ± 1.6‰ (Fig. 1; Table 2). The data show a moderately negative skew (skewness = −0.63), indicating a small but statistically significant contribution of isotopically more negative proteins (37).

FIG 1.

Histogram of δ13C values for all SAX fractions measured from sample LH47, separated into quartiles by decreasing IRMS peak area. The values are not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test, P < 0.01).

TABLE 2.

Summary of the δ13C values for the MIS microbial mat samples, with the average FA data weighted by the IRMS peak areaa

| Value | δ13C (‰)-LH47 | δ13C (‰)-LH22 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total organic carbon | −26.9 ± 0.0 | −28.0 ± 0.2 | −1.1 ± 0.2 |

| Weighted average fatty acid | −30.6 ± 0.7 | −31.6 ± 0.4 | −1.1 ± 0.8 |

| Average protein | −24.6 ± 1.6 | n.m. | |

| EPS glucose | n.m.; estimated −26.5 ± 1.7 | −27.6 ± 1.5 | |

| EPS xylose | n.m.; estimated −22.2 ± 1.4 | −23.3 ± 1.2 | |

| EPS arabinose | n.m.; estimated −22.8 ± 0.9 | −23.9 ± 0.3 |

n.m. = not measured. Empty cells in the “Difference” column indicate values for which we only had measurements from one sample.

6% (43/672) of the RP-HPLC fractions contained sufficient carbon for both estimates of phylogenetic abundance (Table S1) and isotopic measurement (Table S4). These fractions were used in subsequent linear regression analyses.

Estimates of protein δ13C values for microbial groups.

The microbial groups were defined in two different sets. The first set includes Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria, and all others that are grouped as “Remainder,” and the second set further subdivides the Proteobacteria into Deltaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria, with the other Proteobacteria being included in “Remainder.” Other taxonomic groups yielded too few assigned data points to resolve via mass-balance mixing approaches. The δ13C values of proteins originating from both sets of microbial groups were estimated via an abundance-weighted multiple linear regression and an unweighted multiple linear regression (Table 3; Fig. 2). When Proteobacteria are grouped as one phylum, the weighted protein estimates for Cyanobacteria and Proteobacteria are isotopically indistinguishable at −24.3 ± 0.4‰ and −24.4 ± 0.3, respectively. When Proteobacteria are separated into the two dominant classes, weighted protein estimates for Cyanobacteria (−24.0 ± 0.4‰) are isotopically more negative than are those for Deltaproteobacteria (−23.3 ± 0.6‰), but they are isotopically more positive than are Gammaproteobacteria (−26.2 ± 1.3‰). As noted above, we suspect that the estimated protein δ13C values for the “Remainder” group contain a relatively large contribution from Bacteriodetes, which is the primary non-SRB heterotroph at MIS.

TABLE 3.

Estimates of the δ13C values (‰) of proteins for the microbial groups from MIS mat sample LH47, as calculated from P-SIF data, using two different subsets of phylogenetic groups

| Microbial group (LH47 only) | Weighted linear regression | Unweighted linear regression |

|---|---|---|

| Proteobacteria grouped by Phylum | ||

| Cyanobacteria | −24.3 ± 0.4 | −25.0 ± 1.2 |

| Proteobacteria | −24.4 ± 0.3 | −24.4 ± 0.6 |

| Other | −23.2 ± 0.4 | −24.2 ± 0.8 |

| Proteobacteria Grouped by Class | ||

| Cyanobacteria | −24.0 ± 0.4 | −24.4 ± 1.1 |

| Gammaproteobacteria | −26.2 ± 1.3 | −27.5 ± 1.7 |

| Deltaproteobacteria | −23.3 ± 0.6 | −23.6 ± 0.8 |

| Other | −24.0 ± 0.3 | −24.1 ± 0.6 |

FIG 2.

A composite of MIS mat carbon isotopic data for sample LH47. The Deltaproteobacteria, Cyanobacteria & Remainder, and Gammaproteobacteria protein δ13C values are represented by dashed, dotted and dashed, and dotted lines, respectively. The δ13C values of individual FA are indicated by gray circles. The circle area corresponds to the abundance, relative to the n-C16:0 FA. The δ13C estimates for individual glucose (G), xylose (X), and arabinose (A) moieties from extracted EPS are indicated by white circles. The circle area corresponds to the abundance, relative to the glucose moieties. Monosaccharide δ13C estimates were generated by adding 1.1‰ to the LH22 data, based on the consistency in the FA δ13C patterns (Table 3). The shading and error bars represent ±1 SD from the mean.

Bulk, fatty acid, and sugar carbon isotope ratios.

The total organic carbon (TOC) values in LH47 and LH22 were −26.9 ± 0.0‰; and −28.0 ± 0.2‰, respectively (Table 2). Both values are within the error of the δ13C composition (−28.1 ± 1.1‰) of a cyanobacterial mat sample that was taken in the summer of 2007 by (38). The TOC value for LH47 is 2.3 ± 1.6‰ depleted in δ13C, relative to the average protein.

The δ13C value of DIC in the vent water above the mat was not measured at the time of sampling. Furthermore, Nold et al. (38) demonstrated that cyanobacterial mats at MIS utilize DIC from the groundwater instead of from the lake water. The same authors measured the groundwater DIC δ13C composition at −6.0‰ ± 0.2‰ in the summer of 2007 (34). Assuming a substrate DIC δ13C value of −6.0‰ for both samples, LH47 TOC is 20.9 ± 0.2‰ depleted in δ13C, relative to DIC, and LH22 is 22.0 ± 0.2‰ depleted in δ13C, relative to DIC.

Individual FAs n-C14:0, n-C15:0, n-C16:0; n-C16:1, n-C17:0, n-C17:1; and n-C18x were the only measurable FAs that were recovered in both LH22 and LH47 (Table 4). The δ13C values of these FAs ranged from 0.7 to 9.3‰ depleted in δ13C (LH47) to 1.2 to 6.3‰ depleted in δ13C (LH22), relative to TOC. Thus, the weighted average fatty acids (FA, weighted by IRMS peak area) are 3.7 ± 0.7‰ depleted (LH47) and 3.6 ± 0.4‰ depleted (LH22) in δ13C, relative to TOC (Table 2).

TABLE 4.

δ13C compositions of individual FAs extracted from LH47 and LH22 as well as the differences between the two sets of data

| FA | δ13C (‰)-LH47 | Abundance relative to 16:0-LH47 | δ13C (‰)-LH22 | Abundance relative to 16:0-LH22 | Difference δ13C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-C14:0 | −32.3 ± 1.6 | 0.24 | −34.0 ± 0.0 | 0.28 | −1.7 ± 1.6 |

| n-C15:0 | −28.1 ± 1.9 | 0.46 | −29.3 ± 0.6 | 0.82 | −1.3 ± 2.5 |

| n-C16:1 | −30.0 ± 0.2 | 1.10 | −31.9 ± 1.0 | 1.22 | −1.9 ± 1.2 |

| n-C16:0 | −31.2 ± 0.2 | 1.00 | −32.2 ± 0.1 | 1.00 | −0.9 ± 0.3 |

| n-C17:1 | −27.6 ± 1.2 | 0.53 | −29.2 ± 0.2 | 0.64 | −1.5 ± 1.4 |

| n-C17:0 | −33.1 ± 1.3 | 0.27 | −32.7 ± 0.0 | 0.39 | 0.4 ± 1.4 |

| n-C18:x | −36.2 ± 0.6 | 0.32 | −34.3 ± 0.2 | 0.45 | 1.9 ± 0.8 |

Only LH22 had sufficient sample remaining after the analyses with which to measure the δ13C values of the monosaccharide moieties that were extracted from the EPS. Three monosaccharide sugars were present in sufficient abundance for isotopic measurement: glucose (−27.6 ± 1.5‰), xylose (−23.3 ± 1.2‰), and arabinose (−23.9 ± 0.3‰) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

The δ13C values for the TOC and weighted average fatty acids are both offset by approximately 1.1‰ across the corresponding carbon pools in samples LH47 and LH22 (Table 2), and the individual fatty acids in the two samples (Table 4) are all offset within an error of 1.1‰. This indicates that in both samples, relative isotopic differences between major carbon pools (e.g., protein, lipid, and carbohydrate) are similar. As such, we can confidently assume that both the relative protein δ13C values that were estimated for the microbial groups (defined broadly [i.e., at the phylum or class level, rather than the species level]) and the relative sugar δ13C values that were extracted from the EPS are consistent for both samples, despite us having each of these measurement types for only one sample. When comparing between samples (e.g., LH22 sugars to LH47 proteins), we applied a ± 1.1‰ offset to the data.

DISCUSSION

Previous research at MIS has provided insight into the composition of the microbial community, its metabolic potential and activity, and the geochemical consequences of that activity (10, 12–16). Here, we further contextualize these observations by estimating the biomass δ13C values of key microbial groups in the MIS ecosystem: Cyanobacteria, sulfur reducing Deltaproteobacteria (SRB), and sulfur oxidizing Gammaproteobacteria (SOB). Via P-SIF, we estimate that SRB are 13C-enriched, relative to Cyanobacteria, whereas SOB are 13C-depleted. Below, we discuss possible anabolic carbon sources for each group of organisms as well as their potential isotopic contributions to the net microbial biomass.

MIS Cyanobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria fix inorganic carbon via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle.

Previously, MIS mats incubated with 14C-labeled bicarbonate under low-oxygen conditions were found to assimilate carbon via both anoxygenic photosynthesis and chemosynthesis in equal proportions, as well as via oxygenic photosynthesis when the sediments were suspended in oxygenated groundwater (13). Subsequently, metagenome-assembled genomes and metatranscriptomes for the dominant organisms at MIS suggested that photosynthetic Cyanobacteria and chemosynthetic Gammaproteobacteria are responsible for the bulk of inorganic carbon fixation via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB; reductive pentose phosphate) cycle (10). Cyanobacterial and gammaproteobacterial proteins in the LH47 sample are approximately 18 and 20‰ depleted in 13C, relative to the assumed DIC (−6‰), respectively. These values are within the reported ranges for both cultured Cyanobacteria fixing carbon via the CBB cycle and the in vitro fractionation for the proteobacterial RuBisCO enzyme (21), and they do not suggest DIC limitation, as has been seen for other mat systems in which the differences between the biomass and DIC δ13C values are relatively small (39, 40).

Potential isotopic implications of cyanobacterial EPS excretion and fermentation.

In microbial mats, heterotrophs and mixotrophs assimilate the metabolic by-products of autotrophic metabolism (41). Common sources of anabolic organic carbon in mats include storage sugars that are excreted extracellularly (EPS) (e.g., [20]), glycolate excreted during photorespiration (19), and the products of overnight fermentation of storage sugars (e.g., [18]). Previously, we conducted P-SIF on a subaerial, highly oxygenated cyanobacterial mat and measured the δ13C of the monosaccharide moieties of the EPS extracted from the same mat (25). We found that glucose, the only quantitatively important monosaccharide, was isotopically indistinguishable from both cyanobacterial and heterotrophic proteins. As such, we hypothesized that heterotrophic organisms in this oxygenated surface environment were assimilating cyanobacterial photosynthetic sugars (i.e., EPS).

In contrast, EPS extracted from MIS sample LH22 had three quantitatively important monosaccharides: glucose, xylose, and arabinose. Extracted glucose was approximately 4‰ depleted in 13C, relative to both xylose and arabinose (Fig. 3). Furthermore, after normalizing the samples to each other (1.1‰ offset correction; see Results), the glucose is depleted and the xylose and arabinose are enriched in 13C, relative to cyanobacterial proteins. Both the offset between pentose and hexose sugars (approximately 4‰) and the relative ordering (glucose < biomass < arabinose = xylose) agrees with prior δ13C measurements of cell-associated monosaccharide sugars from a cultured freshwater Cyanobacterium (42).

FIG 3.

Partial pathway for cyanobacterial glycogen synthesis and catabolism (orange shading) as well as the cyanobacterial phosphoketolase pathway (purple shading). Broken arrows represent reactions with confirmed or suspected carbon isotopic fractionation. Products that are excreted extracellularly are indicated by boxes. Enzymes are italicized. ackA, acetate kinase; xpk, phosphoketolase; RuBisCO, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase; GS, glycogen synthase; glucose-1-P, glucose-1-phosphate; glucose-6-P, glucose-6-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; Ru5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; RuBP, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate; Xu5P, xylulose-5-phosphate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; AcP, acetylphosphate.

We propose that the isotopic ordering in monosaccharide sugars that was observed in MIS and by (42) is due to carbon isotope fractionation during glycogen synthesis by Cyanobacteria (Fig. 3). To our knowledge, there is no direct in vitro or in vivo evidence for an isotope effect during the polymerization of internal sugars to glycogen. However, indirect evidence supporting this idea includes differences in the δ13C compositions of internal hexose monomers in Cyanobacteria (42, 43) as well as an observation on a natural cyanobacterial mat that EPS is relatively 13C-depleted, compared to TOC (44). We assume that cyanobacterial xylose is isotopically similar to internal glucose, since pentose sugars are derived from the decarboxylation of internal hexose sugars (Fig. 3) (45). If this assumption is correct, xylose and arabinose may be isotopically enriched, relative to EPS and external glucose, as they are derived from a pool of residual internal glucose that is isotopically enriched due to fractionation during glycogen synthesis.

Glycolate excreted during cyanobacterial photorespiration is another potential source of organic carbon for heterotrophic organisms in microbial mats (19). Since glycolate is derived from the RuBisCO substrate ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate, it should have the same δ13C composition as that of initial photosynthate (45). However, it is unlikely that glycolate is a quantitatively important source of organic carbon at MIS. Cyanobacteria possess a pathway to detoxify glycolate intracellularly and typically only excrete glycolate extracellularly under nitrogen limitation (46, 47). MIS sediment organic matter has a greater percentage of nitrogen than does average Lake Huron sediment (48), and evidence for transcriptionally active nitrogen-fixation genes in the MIS mat suggests that the microbial community can compensate during periods of low nitrogen availability (Grim et al., 2021). Furthermore, MIS is low-oxygen and has low light levels, which makes it unlikely that the oxygenase reaction of RuBisCO (i.e., photorespiration) is quantitatively important (49, 50).

A key implication of this internal 13C sorting is the likelihood that Cyanobacteria excrete 13C-enriched acetate that is produced by the phosphoketolase pathway. Cyanobacteria meet their maintenance energy requirements at night via either respiration (in oxic environments) or the fermentation of storage sugars (in anoxic environments) (51). Previously, it was thought that acetate-yielding cyanobacterial fermentation proceeded through the decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA (51). However, recent work (52, 53) has suggested that the primary route instead may be via C5 sugars. The transformation of 13C-enriched xylose via the phosphoketolase pathway would result in the nighttime excretion of 13C-enriched acetate (Fig. 3), primarily by fermenting Cyanobacteria.

Phosphoketolases are glycolytic enzymes that convert xylulose-5-phosphate and/or fructose-6-phosphate into acetyl-phosphate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and/or acetyl-phosphate and erythrose-4-phosphate. In Cyanobacteria, the genes encoding the enzymes are often found in genomic proximity with genes encoding acetate kinases (which convert acetyl-phosphate into acetate) (54). Experiments on the model Cyanobacteria Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 (53) and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (52) demonstrated that deleting the genes that encode the phosphoketolase enzyme reduced viability and prevented the excretion of acetate during both dark anaerobic conditions (Synechococcus) and dark aerobic conditions after they were grown heterotrophically (Synechocystis). Phosphoketolase genes are found in most cyanobacterial genomes, and their expression peaks at sunset (53). These lines of evidence suggest that some (if not most) Cyanobacteria meet their nighttime maintenance energy requirements via the phosphoketolase degradation of C5 sugars, rather than via the decarboxylation of pyruvate. A metagenome-assembled genome from MIS for Phormidium, which is the dominant cyanobacterial genus in sample LH22, contains both pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and acetate kinase genes, which were previously assumed to aid in nighttime fermentation via pyruvate (13). Alternatively, we propose here that the pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase in Phormidium may primarily be associated with another function, namely, either nitrogen fixation (55) or aerobic photomixotrophic growth (56, 57). To investigate whether cyanobacterial phosphoketolases are present at MIS, we conducted a BLAST search against the same metagenome as was used for P-SIF (IMG taxon object ID: 3300028549), using the protein sequence slr0453, which is a putative phosphoketolase from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (52). This search yielded 77 putative proteins with at least 50% shared amino acid identities to the query sequence, including 12 proteins assigned to scaffolds within cyanobacterial bins. Furthermore, 11 proteins (including 3 within cyanobacterial bins) shared at least 70% shared amino acid identities to the sequence slr0453, suggesting that cyanobacterial phosphoketolase enzymes may indeed be present in MIS. In summary, we propose that cyanobacterial exudates at MIS are represented by two end-members: relatively 13C-depleted glycogen from EPS and relatively 13C-enriched acetate from overnight fermentation via the phosphoketolase pathway. The LH47 sample was collected during the day, and, as such, we are assuming that carbon isotopic signatures from nighttime activities are reflected in both the polysaccharide pool and the microbial biomass on the following day. Future work exploring the isotopic consequences of cyanobacterial EPS production and fermentation would benefit from a sampling scheme in which multiple samples are collected over a diel cycle.

Gammaproteobacteria at MIS likely conduct more inorganic carbon fixation than is expected for freshwater species.

The dominant Gammaproteobacteria identified at MIS via the 16S rRNA abundances in August of 2017 represented the sulfur-oxidizing bacterial (SOB) genus Beggiatoa (10, 34). Freshwater Beggiatoa are typically heterotrophic or mixotrophic, despite them having a functional CBB cycle; they grow most readily in culture when supplied with acetate (58). Most, but not all, of the strains that have been described to date are incapable of growing in the laboratory with monosaccharide sugars as the sole carbon sources (59). Even when growing mixotrophically, it is expected that inorganic carbon fixation accounts for a relatively small proportion (<10%) of the total biomass production in freshwater Beggiatoa (58). However, Beggiatoa from the Isolated Sinkhole in Lake Huron are phylogenetically nested between marine and freshwater strains and are capable of H2-based lithoautotrophy, heterotrophy, and, possibly, mixotrophy (60). Based on this context, in addition to the detection of HCO3-fixation (13), the inconsistency between the measured δ13C compositions of gammaproteobacterial proteins, and the expected δ13C value of acetate excreted by Cyanobacteria (discussed above), we propose that SOB at MIS obtain a relatively larger proportion of their biomass carbon from inorganic carbon fixation than would be expected for freshwater Gammaproteobacteria that are growing with acetate as an anabolic carbon source. An alternative or additional explanation for the difference between the presumed acetate and SOB protein δ13C values may be that they assimilate EPS sugars in preference to acetate, given the similarity between the monosaccharide and gammaproteobacterial protein δ13C values. If Gammaproteobacteria in MIS are indeed assimilating acetate as an anabolic carbon source, then the acetate is from a source other than cyanobacterial excretion, the acetate is assimilated in relatively small proportions, or our hypothesis of relatively 13C enriched acetate (discussed above) is incorrect.

Sulfate-reducing bacteria at MIS might assimilate cyanobacterial acetate, whereas other heterotrophic bacteria likely assimilate EPS and/or the products of viral lysis.

Based on the similarity between the δ13C compositions of SRB proteins and xylose monomers, it appears likely that SRB are assimilating acetate generated by the cyanobacterial phosphoketolase pathway as their primary anabolic carbon source. Previously, it was reported that SRB from MIS expressed genes for the autotrophic Wood-Ljungdhal (acetyl-CoA) pathway that reduces CO2 with H2 as an electron donor and produces acetyl-CoA, which is then the primary metabolite for biomass synthesis (10, 61). However, SRB also are known to use the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway in reverse to assimilate acetate both for growth and for respiratory oxidation to CO2 (62). This suggests that the expression of Wood-Ljungdahl genes may have been detected, as the pathway is being used for acetate uptake. Furthermore, prior research on carbon isotopic fractionation during lithoautotrophic growth by SRB using the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (acetate-generating direction) suggests that the resulting biomass should be approximately 11‰ depleted in 13C, relative to substrate CO2 (63). Here, this would yield a biomass of approximately −17‰, which is approximately 6‰ more positive than the measured SRB proteins (−23.3‰). Furthermore, the relatively large differences (≥10‰) between the δ13C compositions of the n-C18:x FAs and the protein estimates for the taxonomic groups suggest that the n-C18:x FAs are derived from either Cyanobacteria or SRB (64, 65). Londry et al. (64) grew SRB under both autotrophic and mixotrophic (on acetate) conditions and found that the n-C18:x FAs from cultured SRB Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and Desulfobacterium autotrophicum were depleted in 13C by >10‰, relative to the biomass when grown on acetate. While the n-C18:x FAs are likely derived from both Cyanobacteria and SRB, the relatively depleted δ13C composition of these FAs supports the existence of a contribution from acetate-consuming SRB.

In the MIS, allochthonous planktonic carbon derived from isotopically distinct lake water DIC (+0.6‰ relative to −6.0‰ for groundwater) (38) is rapidly sedimented, resulting in sedimentary organic carbon that is relatively enriched in δ13C, compared to mat-derived organic carbon (38). Fermentation of this isotopically enriched planktonic carbon would likely create a pool of organic acids enriched in δ13C, relative to Cyanobacteria (23, 27), and the consumption of these sediment-derived organic acids by SRB might also explain why deltaproteobacterial proteins have more positive δ13C compositions than do cyanobacterial proteins. However, we assume that the majority of the organic carbon that is assimilated by SRB is derived from organic carbon production within the mat itself, given the tight metabolic coupling between organic carbon production and consumption in suspended mat samples (no sediment) and mat/sediment core incubations (13).

Although the proteins comprising the “Remainder” fraction could not be confidently assigned to any one taxonomic group, evidence from 16S rRNA analyses in the same location from August of 2017 suggest that Bacteroidetes comprise a relatively large (approximately 15%) proportion of the heterotrophic population (10, 34). The proteins in the “Remainder” fraction were isotopically indistinguishable from cyanobacterial proteins. Since heterotrophic metabolism does not impart significant 13C fractionation in bacteria (23, 24), we can infer that the anabolic carbon source for Bacteroidetes is similar in δ13C composition to the cyanobacterial biomass. Bacteroidetes are broadly known for their ability to degrade a variety of complex polysaccharides (66), making EPS their most likely source of organic carbon. If we assume that xylose, arabinose, and glucose comprise the majority of the EPS at MIS, the δ13C of the EPS, as calculated by the abundance-weighted (IRMS peak areas) average of the three monomers, is −24.5 ± 2.3‰. This value is indistinguishable from those of the cyanobacterial biomass and the “Remainder” biomass, potentially indicating that Bacteroidetes at MIS indiscriminately assimilate hydrolyzed EPS (i.e., all monosaccharide moieties) and/or the average products of total organic carbon from the viral lysis of Cyanobacteria (67).

The heterogeneous δ13C of photosynthetic exudates might have contributed to isotopic variability in ancient microbial mat facies.

The difference in δ13C composition between carbonate and syn-depositional organic matter (Δδ13C) has been remarkably consistent throughout the Phanerozoic era (68) The relatively variable amplitudes in Δδ13C from Precambrian facies has been interpreted as reflecting local rather than global δ13C signatures, specifically, a greater contribution by microbial mats (69–72). In contrast to our prior work on an oxygenated microbial mat (25), suspected autotrophic and heterotrophic organisms at MIS had heterogeneous biomass δ13C compositions, which we attribute to the heterogeneity in the δ13C compositions between different cyanobacterial exudates and the influence of chemoautotrophic metabolism. These studies encompass only two specific modern environments, and significantly more work is necessary before generalizing any observed trends. However, our work underscores the importance of considering local redox conditions when evaluating interspecies δ13C signatures in the rock record, whether it be via comparing the isotopic compositions of lipid biomarkers for distinct groups of organisms (72) or between individual microfossils (73–75). Decades of previous work on modern hypersaline microbial mats (e.g., [40]) and comparisons to the Proterozoic rock record (e.g., [76]) support the hypothesis that ancient redox conditions controlled the relative proportion of chemoautotrophic metabolism and therefore substantially influenced carbon isotopic discrimination by Precambrian microbial communities. We hypothesize that photosynthetic exudates with heterogeneous δ13C values might have acted as additional sources of isotopic variability in ancient microbial mat facies.

In a highly photic, oxygenated, and relatively nutrient-limited surface microbial mat from Yellowstone National Park (YNP), we found that EPS sugars were indistinguishable from cyanobacterial proteins, likely because Cyanobacteria in such environments allocate the majority of their initial photosynthate to glycogen that is extracellularly excreted (20, 25). If there is an isotopic fractionation during the polymerization of glycogen (the main component of cyanobacterial EPS), it is minimally expressed, as the majority of the initial substrate has been converted to product (77). Alternatively, Cyanobacteria in oxygenated environments might excrete large proportions of fixed carbon as glycolate due to the oxygenase reaction of RuBisCO (19) and the nitrogen requirements of the glycolate detoxification pathway (46, 47). However, glycolate is derived directly from cyanobacterial initial photosynthate. So, presumably, glycolate-based heterotrophy would also result in biomass that is isotopically indistinguishable from this source.

In short, in an oxygenated environment with a relatively high photon flux (e.g., YNP), we would predict that the biomass of Cyanobacteria, their net exudates, and, therefore, the total average composition of aerobic heterotrophic organisms, will all be isotopically homogenous. In contrast, MIS has a relatively lower photon flux, is low-oxygen, and is relatively higher in nutrients. As such, Cyanobacteria can presumably detoxify internal glycolate, and, due to the demands of diel redox fluctuation, may not allocate the majority of their initial photosynthate to EPS. Instead, Cyanobacteria at MIS may ferment a significant portion of their internal sugar, resulting in both (i) an expression of the suspected isotopic fractionation associated with glycogen synthesis, resulting in 13C-depleted EPS, relative to intracellular sugars, and (ii) 13C-enriched acetate derived from this relatively enriched internal pool. We suspect that at MIS, cyanobacterial exudates are isotopically heterogeneous as a direct consequence of nighttime anoxia. Future work to directly measure the δ13C compositions of cyanobacterial metabolites, including acetate and glycolate, that are produced under different environmental conditions would help test this hypothesis.

Conclusions.

In this work we determined the protein δ13C values of autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic organisms as well as the δ13C values of the sugar moieties of EPS, all from flat-mat samples from the Middle Island Sinkhole in Lake Huron, which is a low-oxygen Proterozoic analogue environment. Our results show that Cyanobacteria (autotrophs) are isotopically distinct from both sulfate reducing bacteria (heterotrophs) and sulfate oxidizing bacteria (autotrophs or mixotrophs) and that sugar moieties extracted from EPS are equally isotopically heterogeneous. We hypothesize that the observed δ13C patterns in proteins from different bacterial groups are due to isotopic heterogeneity in cyanobacterial exudates and that these patterns are common within benthic microbial mats that experience nighttime anoxia. Proterozoic microbial mat facies often show greater variability in δ13C values internally, compared to Phanerozoic facies, and this may be partially due to isotopically heterogeneous heterotrophic carbon sources, particularly cyanobacterial exudates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

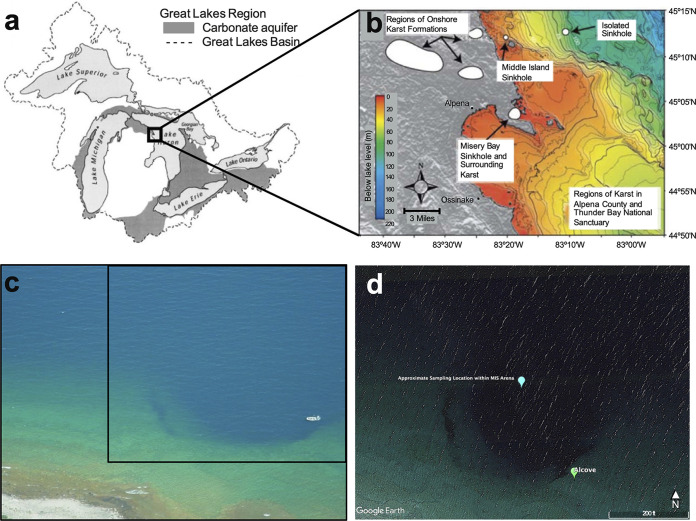

Two flat-mat samples were collected by scuba divers from the R/V Storm during the daytime on May 31st, 2017 (here LH22), and August 7th, 2017 (here LH47), from the same location within a 100 m2 area of the Middle Island Sinkhole arena (45.1984°N, 83.32721°W) by hand push core (Fig. 4). The cores were rapidly transferred to the surface and mats, which were located within the first 1.0 mm of the core surface and were not firmly attached to the sediment underneath (13, 78), and they were carefully peeled from the cohesive sediment and immediately placed on dry ice before being shipped to the laboratory. The groundwater layer overlying the sediment had a higher specific conductivity (1,856 μS cm−1), a lower temperature (10 to 12°C), and a lower dissolved oxygen (2.38 mg/L or 23% saturation) than did the surface of Lake Huron (205 μS cm−1, 19°C) (34). These physiochemical measurements are consistent with measurements from previous studies at MIS (14, 38, 79–81).

FIG 4.

An overview of our sampling location, modified from Biddanda et al. (14). (a) Map of the North American Laurentian Great Lakes Basin, showing regions of carbonate aquifers. (b) Regions of aboveground karst formations and submerged sinkholes within Lake Huron in the area of the black box in panel A (depth contours in meters, 0 to 150 m; modified from Coleman [2002] [96]). (c) Aerial photo of the Middle Island Sinkhole (MIS), with a nine-meter Boston Whaler boat on the right for scale. (d) The specific sampling location within the MIS for our study, in the area of the black box in panel C. “Alcove” represents the lighter carbonate platform seen in panel C.

Lipid extraction and identification.

Lipids were extracted from approximately 0.3 g (dry) of LH22 and 0.2 g (dry) of LH47 freeze-dried mat samples via a modified Bligh and Dyer procedure (82). The total lipid extracts were transesterified to generate fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs; 5% HCl/methanol [vol/vol], 70°C, 4 h). The reactions were stopped by the addition of ultrapure H2O, after which the organic phases were extracted into hexane/dichloromethane (4:1, vol/vol). The FAME derivatives of n-C16:0, n-C19:0, and n-C24:0 FA standards with known δ13C compositions (−29.5‰, −31.7‰, and −30.8‰, respectively) were prepared in parallel to correct for the 13C content of the derivatized carbon that was introduced during transesterification. The FAMEs were further separated from the derivatized extracts by elution over SiO2 gel, using the solvent program described in (83).

The FAMEs were identified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS; Agilent 6890N GC, 5973 MS equipped with a 30m DB-5MS column) by comparison to known patterns of relative retention times (83, 84) and by comparison of the fragment mass spectra to spectra from the National Institute of Standards and Technology Library (85). The injection, oven temperature programs, and gas flow rates were adopted from Close et al., 2014 (86).

Protein stable isotope fingerprinting.

Protein stable isotope fingerprinting was performed as previously described (28). Due to the relatively large sample requirements (multiple grams) for P-SIF, P-SIF was only performed on LH47. Proteins were extracted by placing 21.5 g of wet mat material and up to 8 mL of B-PER protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific) in two 50 mL Teflon tubes and sonicating using a 500-watt Qsonica ultrasonic processor that was equipped with a cup horn. The cup horn was filled with ice water, and the sonicator was set to 25 s on and 35 s off for a total of 5 min of sonication. The solids and cell material were removed via centrifugation at 16,000 × g. Proteins were precipitated from the supernatant in acetone and resuspended in 100 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 9) to yield a total soluble protein extract. This extract was further separated into 960 fractions on an Agilent 1100 series HPLC with a DAD detector and a fraction collector, using two orthogonal levels of chromatography. The first was done via strong anion exchange (SAX; Agilent PL-SAX column; 4.6 × 50 mm, 8 μm) (20 fractions), and the second was done via reverse phase (RP; Agilent Poroshell 300SB-C3 column, 2.1 × 75 mm, 5 μm; 48 fractions), using the solvent gradients described in (28). An aliquot of each final fraction was split into 96-well plates for isotope analysis (70%), and the remaining 30% was reserved for tryptic digestion, which was followed by peptide sequencing.

Protein taxonomic identification.

Plates for tryptic digestion were prepared as detailed in (28). Peptide samples were separated via nanoflow liquid chromatography on a capillary C18 column (Thermo Acclaim PepMap 100 Å, 2 μm particles, 50 μm I.D. × 50 cm length) using a water/acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid gradient (2 to 50% AcN over 180 min) at 90 nL/min, using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 LC system with nanoelectrospray ionization (Proxeon Nanospray Flex source). Mass spectra were collected on an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) that was operating in a data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, with one high resolution (120,000 m/Δm) MS1 parent ion full scan triggering 15 rapid-mode MS2 CID fragment ion scans of selected precursors. The proteomic mass spectra were matched to the peptide sequences using Sequest HT implemented in Proteome Discoverer 2.1. A combined metagenomic assembly of four metagenomes that were collected in 2016 from a Middle Island Sinkhole microbial mat were used as the search database. Those data are available via the Integrated Microbial Genomes database (IMG) (taxon object ID: 3300028549) and the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accession numbers (SRR21758066 to SRR21758069) under NCBI BioProject PRJNA72255. Proteomic mass spectral data are available via the Mass Spectrometry Interactive Virtual Environment (MassIVE) repository (massive.ucsd.edu) under accession MSV000090594. This methodology only targets Bacteria. The primer set that was used to generate the metagenomic databases targeted the bacterial 16S rRNA gene v4 region. As such, archaeal and eukaryal amplicon reads were routinely filtered out.

The label-free protein abundances in each well were estimated by summing the integrated MS1 peptide peak areas for the peptides that were assigned to specific proteins. Peptides mapping onto more than one protein were assigned to the protein with the most peptide evidence (87). The relative abundances of the phylogenetic groups in each well were determined by comparing the sum of all of the peptide peak areas for the proteins that were taxonomically assigned to a given phylogenetic group to the sum of all of the peptide peak areas for the proteins in a given well (28).

Sugar extraction and derivatization.

Due to sample limitations, EPS was only extracted from sample LH22. Briefly, 20 mL of 10% (wt/vol) NaCl was added to 10 g of wet homogenized microbial mat sample and vortexed using established methods (88). This solution was incubated at 40°C for 15 min, and this was followed by centrifugation at 8,200 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected, and the precipitant was reextracted with 20 mL of 10% NaCl two more times. After cooling in an ice bath, 100% ethanol was added to the supernatant to a final concentration of 70%. The EPS were precipitated at 4°C overnight and removed via centrifugation.

Extracted EPS were hydrolyzed into monomers using the method of (89) by vortexing with 1 mL of 12 M H2SO4 in a Teflon tube and then stirring at approximately 400 rpm for 2 h at room temperature. This was followed by dilution to 1 M and heating (85°C for 4.5 h). After cooling to room temperature, the solution was neutralized to pH 7 using BaCO3. Once neutralized, the solution was centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 5 min, after which the supernatant was collected, frozen, and lyophilized.

Lyophilized sugar monomers were derivatized immediately prior to isotope analysis, again using established protocols (89). Arabinose, xylose, glucose, and myo-inositol standards with known δ13C compositions (−11.7‰, −9.7‰, −11.1‰, and −14.4‰, respectively) were prepared in parallel to correct for the 13C content of the carbon that was introduced during the derivatization. Briefly, 1 mL of a methylboronic acid/pyridine (10 mg/mL) mixture was added to 5 mg of sample or to 1 mg of total glucose, arabinose, and xylose standards and was then heated at 60°C for 30 min. This was followed by the addition of 100 μL N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) and a further 5 min of heating. Because myo-inositol is insoluble in pyridine, 250 to 500 μg myo-inositol were instead dissolved in 1 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for derivatization. After the heating step, the myo-inositol standard mixture was cooled to room temperature before the addition of 1 mL of cyclohexane and 100 μL of BSTFA (90). All of the samples were dried under N2 and quantitatively dissolved in ethyl acetate prior to the isotope analysis.

Isotope ratio mass spectrometry.

To measure the δ13C value of the bulk TOC, triplicate freeze-dried microbial mat samples were placed in silver capsules (Costech) and acidified with 100 μL of 1N HCl to remove the dissolved inorganic carbon. The samples were dried at 50°C, enveloped in tin capsules (Costech), and analyzed on a Costech 4010 Elemental Analyzer that was connected to a Thermo Scientific Delta V IRMS.

FAME and derivatized sugar monomer δ13C compositions were analyzed via gas chromatography-isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GC-IRMS; ThermoScientific Delta V Advantage connected to a Trace GC Ultra via a GC Isolink interface). In both cases, 1 μL of sample was coinjected with 0.5 μL of internal standard (n-C32; 50 ng/μL). FAMEs were run on a 30 m × 0.25 mm HP-5MS column as previously described (86). Sugar monomers were run on a 30 m × 0.25 mm DB-1701 column. The samples were transferred onto the column using a programmable temperature vaporizer (PTV) inlet at an injection temperature of 70°C, and this was followed by 330°C for 4 min. The GC-IRMS oven temperature gradient was adopted from van Dongen et al. (2001) (89).

A stable carbon isotope analysis of the P-SIF protein fractions was conducted using spooling-wire microcombustion (SWiM)-IRMS (91–94). The SWiM-IRMS configuration used here is adapted from (91) and is detailed in (28). Fractions (96-well plate aliquots) were measured in triplicate. Only data from wells containing >0.56 nmol C/μL (approximately 350 mV peak amplitude, m/z 44) and with measurement standard deviations of <2‰ were retained (28).

Data analysis.

Protein phylogenetic data were grouped in two different sets. First, they were grouped by the most abundant phyla: Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria, and “Remainder,” which included all of the other annotated proteins. Given the relatively large proportion of Proteobacteria in LH47, we further subdivided the Proteobacteria into Deltaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and Remainder for the second set. The remaining data analysis is described in detail for the first set. The methods were identical for the second set, using two proteobacterial variables instead of one. The estimates of the δ13C compositions of the proteins for each group (δcyano, δproteo, and δrem, respectively) were calculated via multiple linear regression. Specifically, the δ13C value for a given well (δm) and the estimated fractional abundances (from the summed protein peak areas) were used in two overdetermined linear equations.

| (1) |

| (2) |

In these equations, δcyano, δproteo, and δrem are the unknowns, ∑Prot is the sum of the integrated peptide peak areas for the proteins that were taxonomically assigned to the subscripted group, σm is the precision for δm (± 1 SD), and i represents each individual plate well for which both the δm and peptide peak area values were measured (28).

Equation 1 represents an unweighted estimate. Equation 2 is weighted by the precision of the isotopic measurements for each well (95). Equations 1 and 2 were solved inversely for δcyano, δproteo, and δrem via singular value decomposition, using the built-in MATLAB SVD function (95). The precision for this method is reported as ± the square root of the error variance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We give thanks to Lichun Zhang for the management and maintenance of the biogeochemical proteomics facility at UChicago as well as to W. Mohr and S.J. Carter for their analytical advice. We thank the three anonymous reviewers whose comments improved the manuscript. The divers and crew of the R/V Storm NOAA as well as the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary provided critical dive support and assistance with the sampling and ship time. This work was supported by grants from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (to A.P.), a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (to A.C.G.), and the NSF grant EAR-1637066 (to G.J.D.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Ana C. Gonzalez-Nayeck, Email: gonzalezvaldes@g.harvard.edu.

John R. Spear, Colorado School of Mines

REFERENCES

- 1.Knoll AH, Nowak MA. 2017. The timetable of evolution. Sci Adv 3:e1603076. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1603076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarhan LG. 2018. The early Paleozoic development of bioturbation—evolutionary and geobiological consequences. Earth Sci Rev 178:177–207. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagadorn JW, Bottjer DJ. 1997. Wrinkle structures: microbially mediated sedimentary structures common in subtidal siliciclastic settings at the Proterozoic-Phanerozoic transition. Geol 25:1047–1050. doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gehling JG. 1999. Microbial mats in terminal Proterozoic siliciclastics; Ediacaran death masks. Palaios 14:40–57. doi: 10.2307/3515360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steiner M, Reitner J. 2001. Evidence of organic structures in Ediacara-type fossils and associated microbial mats. Geol 29:1119–1122. doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callow RHT, Brasier MD. 2009. Remarkable preservation of microbial mats in Neoproterozoic siliciclastic settings: implications for Ediacaran taphonomic models. Earth Sci Rev 96:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2009.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Javaux EJ. 2019. Challenges in evidencing the earliest traces of life. Nature 572:451–460. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López-García P, Moreira D. 2020. The syntrophy hypothesis for the origin of eukaryotes revisited. Nat Microbiol 5:655–667. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0710-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gingras M, Hagadorn JW, Seilacher A, Lalonde SV, Pecoits E, Petrash D, Konhauser KO. 2011. Possible evolution of mobile animals in association with microbial mats. Nature Geosci 4:372–375. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grim SL, Voorhies AA, Biddanda BA, Jain S, Nold SC, Green R, Dick GJ. 2021. Omics-inferred partitioning and expression of diverse biogeochemical functions in a low-O2 cyanobacterial mat community. mSystems 6:e0104221. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.01042-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanson TE, Luther GW, Findlay AJ, MacDonald DJ, Hess D. 2013. Phototrophic sulfide oxidation: environmental insights and a method for kinetic analysis. Front Microbiol 4:382. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klatt JM, Gomez-Saez GV, Meyer S, Ristova PP, Yilmaz P, Granitsiotis MS, Macalady JL, Lavik G, Polerecky L, Bühring SI. 2020. Versatile cyanobacteria control the timing and extent of sulfide production in a Proterozoic analog microbial mat. ISME J 14:3024–3037. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-0734-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voorhies AA, Biddanda BA, Kendall ST, Jain S, Marcus DN, Nold SC, Sheldon ND, Dick GJ. 2012. Cyanobacterial life at low O2: community genomics and function reveal metabolic versatility and extremely low diversity in a Great Lakes sinkhole mat. Geobiology 10:250–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2012.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biddanda BA, Nold SC, Ruberg SA, Kendall ST, Sanders TG, Gray JJ. 2009. Great Lakes sinkholes: a microbiogeochemical frontier. Eos Trans AGU 90:61–62. doi: 10.1029/2009EO080001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nold SC, Pangborn JB, Zajack HA, Kendall ST, Rediske RR, Biddanda BA. 2010. Benthic bacterial diversity in submerged sinkhole ecosystems. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:347–351. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01186-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medina MJ. 2017. Genomic and transcriptomic evidence for niche partitioning among sulfate-reducing bacteria in redox-stratified cyanobacterial mats of the Middle Island Sinkhole. University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston DT, Wolfe-Simon F, Pearson A, Knoll AH. 2009. Anoxygenic photosynthesis modulated Proterozoic oxygen and sustained Earth’s middle age. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:16925–16929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909248106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Meer M, Schouten S, Mary M, Nübel U, Wieland A, Kühl M, Leeuw W, Damsté JSS, Ward DM, Bateson MM, Nu U, Ku M, Leeuw JW, Damste JSS. 2005. Diel variations in carbon metabolism by green nonsulfur-like bacteria in alkaline siliceous hot spring microbial mats from Yellowstone National Park. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3978–3986. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3978-3986.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateson MM, Ward DM. 1988. Photoexcretion and fate of glycolate in a hot spring cyanobacterial mat. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:1738–1743. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.7.1738-1743.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nold SC, Ward DM. 1996. Photosynthate partitioning and fermentation in hot spring microbial mat communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:4598–4607. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4598-4607.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.House CH, Schopf JW, Stetter KO. 2003. Carbon isotopic fractionation by Archaeans and other thermophilic prokaryotes. Organic Geochemistry 34:345–356. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(02)00237-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart RK, Mayali X, Lee JZ, Everroad RC, Hwang M, Bebout BM, Weber PK, Pett-Ridge J, Thelen MP. 2016. Cyanobacterial reuse of extracellular organic carbon in microbial mats. ISME J 10:1240–1251. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blair N, Leu A, Muñoz E, Olsen J, Kwong E, Des Marais D. 1985. Carbon isotopic fractionation in heterotrophic microbial metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol 50:996–1001. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.4.996-1001.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. 1977. Mechanism of carbon isotope fractionation associated with lipid synthesis. Science 197:261–263. doi: 10.1126/science.327543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Nayeck AC, Mohr W, Tang T, Sattin S, Parenteau MN, Jahnke LL, Pearson A. 2022. Absence of canonical trophic levels in a microbial mat. Geobiology 20:726–740. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter EG, Bebout BM, Kelley CA. 2009. Isotopic composition of methane and inferred methanogenic substrates along a salinity gradient in a hypersaline microbial mat system. Astrobiology 9:383–390. doi: 10.1089/ast.2008.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penning H, Conrad R. 2006. Carbon isotope effects associated with mixed-acid fermentation of saccharides by Clostridium papyrosolvens. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 70:2283–2297. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2006.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohr W, Tang T, Sattin SR, Bovee RJ, Pearson A. 2014. Protein stable isotope fingerprinting: multidimensional protein chromatography coupled to stable isotope-ratio mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 86:8514–8520. doi: 10.1021/ac502494b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abelson PH, Hoering TC. 1961. Carbon isotope fractionation in formation of amino acids by photosynthetic organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 47:623–632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.5.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cano M, Holland SC, Artier J, Burnap RL, Ghirardi M, Morgan JA, Yu J. 2018. Glycogen synthesis and metabolite overflow contribute to energy balancing in cyanobacteria. Cell Rep 23:667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bubis JA, Levitsky LI, Ivanov MV, Tarasova IA, Gorshkov MV. 2017. Comparative evaluation of label-free quantification methods for shotgun proteomics. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 31:606–612. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finkel Zv, Follows MJ, Liefer JD, Brown CM, Benner I, Irwin J. 2016. Phylogenetic diversity in the macromolecular composition of microalgae. PLoS One 11:e0155977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biddanda BA, McMillan AC, Long SA, Snider MJ, Weinke AD. 2015. Seeking sunlight: rapid phototactic motility of filamentous mat-forming cyanobacteria optimize photosynthesis and enhance carbon burial in Lake Huron’s submerged sinkholes. Front Microbiol 6:930. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grim SL, Stuart DG, Aron P, Levin NE, Kinsman-Costello LE, Waldbauer JE, Dick GJ. 2023. Seasonal Shifts in community composition and proteome expression in a sulfur-cycling cyanobacterial mat. bioRxiv. 2023.01.30.526236. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Grim S. 2019. Genomic and functional investigations into seasonally-impacted and morphologically-distinct anoxygenic photosynthetic cyanobacterial mats. University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Větrovský T, Baldrian P. 2013. The variability of the 16S rRNA gene in bacterial genomes and its consequences for bacterial community analyses. PLoS One 8:e57923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bulmer M. 1979. Principles of statistics. Courier Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nold SC, Bellecourt MJ, Kendall ST, Ruberg SA, Sanders TG, Klump JV, Biddanda BA. 2013. Underwater sinkhole sediments sequester Lake Huron’s carbon. Biogeochemistry 115:235–250. doi: 10.1007/s10533-013-9830-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schouten S, Hartgers WA, Lòpez JF, Grimalt JO, Sinninghe Damsté JS. 2001. A molecular isotopic study of 13C-enriched organic matter in evaporitic deposits: recognition of CO2-limited ecosystems. Org Geochem 32:277–286. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00177-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Des Marais DJ, Canfield DE. 1994. The carbon isotope biogeochemistry of microbial mats, p 289–298. In Microbial Mats: Structure, Development and Environmental Significance. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prieto-Barajas CM, Valencia-Cantero E, Santoyo G. 2018. Microbial mat ecosystems: structure types, functional diversity, and biotechnological application. Electronic J Biotechnology 31:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbt.2017.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teece MA, Fogel ML. 2007. Stable carbon isotope biogeochemistry of monosaccharides in aquatic organisms and terrestrial plants. Org Geochem 38:458–473. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pereira S, Zille A, Micheletti E, Moradas-Ferreira P, de Philippis R, Tamagnini P. 2009. Complexity of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides: composition, structures, inducing factors and putative genes involved in their biosynthesis and assembly. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33:917–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wieland A, Pape T, Möbius J, Klock JH, Michaelis W. 2008. Carbon pools and isotopic trends in a hypersaline cyanobacterial mat. Geobiology 6:171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2007.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White D. 2000. The physiology and biochemistry of prokaryotes. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Renström‐Kellner E, Bergman B. 1989. Glycolate metabolism in cyanobacteria. III. Nitrogen controls excretion and metabolism of glycolate in Anabaena cylindrica. Physiol Plant 77:46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1989.tb05976.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisenhut M, Ruth W, Haimovich M, Bauwe H, Kaplan A, Hagemann M. 2008. The photorespiratory glycolate metabolism is essential for cyanobacteria and might have been conveyed endosymbiontically to plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:17199–17204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807043105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rico KI, Sheldon ND. 2019. Nutrient and iron cycling in a modern analogue for the redoxcline of a Proterozoic ocean shelf. Chem Geol 511:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warburg O. 1928. Über die Geschwindigkeit der photochemischen Kohlensäurezersetzung in lebenden Zellen. II. Über die Katalytischen Wirkungen der Lebendigen Substanz 341–366. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Busch FA. 2020. Photorespiration in the context of Rubisco biochemistry, CO2 diffusion and metabolism. Plant J 101:919–939. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stal LJ, Moezelaar R. 1997. Fermentation in cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 21:179–211. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(97)00056-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong W, Lee TC, Rommelfanger S, Gjersing E, Cano M, Maness PC, Ghirardi M, Yu J. 2015. Phosphoketolase pathway contributes to carbon metabolism in cyanobacteria. Nature Plants 2:1–8. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chuang DSW, Liao JC. 2021. Role of cyanobacterial phosphoketolase in energy regulation and glucose secretion under dark anaerobic and osmotic stress conditions. Metab Eng 65:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sánchez B, Zúñiga M, González-Candelas F, de Los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Margolles A. 2010. Bacterial and eukaryotic phosphoketolases: phylogeny, distribution and evolution. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 18:37–51. doi: 10.1159/000274310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bothe H, Schmitz O, Yates MG, Newton WE. 2010. Nitrogen fixation and hydrogen metabolism in cyanobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:529–551. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00033-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Chen X, Spengler K, Terberger K, Boehm M, Appel J, Barske T, Timm S, Battchikova N, Hagemann M, Gutekunst K. 2022. Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and low abundant ferredoxins support aerobic photomixotrophic growth in cyanobacteria. Elife 11. doi: 10.7554/eLife.71339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klatt JM, Chennu A, Arbic BK, Biddanda BA, Dick GJ. 2021. Possible link between Earth’s rotation rate and oxygenation. Nat Geosci 14:564–570. doi: 10.1038/s41561-021-00784-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garrity G, Bell JA, Lilburn T. 2005. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology: the proteobacteria; part B: the gammaproteobacteriapesquisa.bvsalud.org. Retrieved 11 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dubinina G, Savvichev A, Orlova M, Gavrish E, Verbarg S, Grabovich M. 2017. Beggiatoa leptomitoformis sp. Nov., the first freshwater member of the genus capable of chemolithoautotrophic growth. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 67:197–204. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharrar AM, Flood BE, Bailey JV, Jones DS, Biddanda BA, Ruberg SA, Marcus DN, Dick GJ. 2017. Novel large sulfur bacteria in the metagenomes of groundwater-fed chemosynthetic microbial mats in the Lake Huron basin. Front Microbiol 8:791. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wood HG, Ragsdale SW, Pezacka E. 1986. The acetyl-CoA pathway of autotrophic growth. FEMS Microbiol Rev 39:345–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1986.tb01865.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spormann AM, Thauer RK. 1988. Anaerobic acetate oxidation to CO2 by Desulfotomaculum acetoxidans. Arch Microbiol 150:374–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00408310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Londry KL, Des Marais DJ. 2003. Stable carbon isotope fractionation by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:2942–2949. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.5.2942-2949.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Londry KL, Jahnke LL, Des Marais DJ. 2004. Stable carbon isotope ratios of lipid biomarkers of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:745–751. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.745-751.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakata S, Hayes JM, McTaggart AR, Evans RA, Leckrone KJ, Togasaki RK. 1997. Carbon isotopic fractionation associated with lipid biosynthesis by a cyanobacterium: relevance for interpretation of biomarker records. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61:5379–5389. doi: 10.1016/s0016-7037(97)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McKee LS, la Rosa SL, Westereng B, Eijsink VG, Pope PB, Larsbrink J. 2021. Polysaccharide degradation by the Bacteroidetes: mechanisms and nomenclature. Environ Microbiol Rep 13:559–581. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Voorhies AA, Eisenlord SD, Marcus DN, Duhaime MB, Biddanda BA, Cavalcoli JD, Dick GJ. 2016. Ecological and genetic interactions between cyanobacteria and viruses in a low-oxygen mat community inferred through metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. Environ Microbiol 18:358–371. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krissansen-Totton J, Buick R, Catling DC. 2015. A statistical analysis of the carbon isotope record from the Archean to phanerozoic and implications for the rise of oxygen. Am J Sci 315:275–316. doi: 10.2475/04.2015.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nelson LL, Ahm ASC, Macdonald FA, Higgins JA, Smith EF. 2021. Fingerprinting local controls on the Neoproterozoic carbon cycle with the isotopic record of Cryogenian carbonates in the Panamint Range, California. Earth Planet Sci Lett 566:116956. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2021.116956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fox CP, Cui X, Whiteside JH, Olsen PE, Summons RE, Grice K. 2020. Molecular and isotopic evidence reveals the end-Triassic carbon isotope excursion is not from massive exogenous light carbon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:30171–30178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917661117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schobben M, van de Schootbrugge B. 2019. Increased stability in carbon isotope records reflects emerging complexity of the biosphere. Front Earth Sci 7:87. doi: 10.3389/feart.2019.00087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blumenberg M, Thiel V, Riegel W, Kah LC, Reitner J. 2012. Biomarkers of black shales formed by microbial mats, Late Mesoproterozoic (1.1 Ga) Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania. Precambrian Res 196–197:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2011.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peng X, Guo Z, House CH, Chen S, Ta K. 2016. SIMS and NanoSIMS analyses of well-preserved microfossils imply oxygen-producing photosynthesis in the Mesoproterozoic anoxic ocean. Chem Geol 441:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schopf JW, Kitajima K, Spicuzza MJ, Kudryavtsev AB, Valley JW. 2018. SIMS analyses of the oldest known assemblage of microfossils document their taxon-correlated carbon isotope compositions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:53–58. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718063115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Osterhout J, Schopf JW, Williford K, McKeegan K, Kudryavtsev AB, Liu M-C. 2021. Carbon isotopes of Proterozoic filamentous microfossils: SIMS analyses of ancient cyanobacteria from two disparate shallow-marine cherts. Geomicrobiol J 38:719–731. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2021.1939813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Des Marais DJ. 1997. Isotopic evolution of the biogeochemical carbon cycle during the Proterozoic Eon. Org Geochem 27:185–193. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00061-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hayes JM. 2001. Fractionation of carbon and hydrogen isotopes in biosynthetic processes. Rev Mineral Geochem 43:225–277. doi: 10.2138/gsrmg.43.1.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Merz E, Dick GJ, de Beer D, Grim S, Hübener T, Littmann S, Olsen K, Stuart D, Lavik G, Marchant HK, Klatt JM. 2021. Nitrate respiration and diel migration patterns of diatoms are linked in sediments underneath a microbial mat. Environ Microbiol 23:1422–1435. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baskaran M, Novell T, Nash K, Ruberg SA, Johengen T, Hawley N, Klump JV, Biddanda BA. 2016. Tracing the seepage of subsurface sinkhole vent waters into Lake Huron using radium and stable isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen. Aquat Geochem 22:349–374. doi: 10.1007/s10498-015-9286-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kinsman-Costello LE, Sheik CS, Sheldon ND, Allen Burton G, Costello DM, Marcus D, Uyl PAD, Dick GJ. 2017. Groundwater shapes sediment biogeochemistry and microbial diversity in a submerged Great Lake sinkhole. Geobiology 15:225–239. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ruberg SA, Kendall ST, Biddanda BA, Black T, Nold SC, Lusardi WR, Green R, Casserley T, Smith E, Sanders TG, Lang GA, Constant SA. 2008. Observations of the Middle Island Sinkhole in Lake Huron - a unique hydrogeologic and glacial creation of 400 million years. Mar Technol Soc j 42:12–21. doi: 10.4031/002533208787157633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sturt HF, Summons RE, Smith K, Elvert M, Hinrichs KU. 2004. Intact polar membrane lipids in prokaryotes and sediments deciphered by high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization multistage mass spectrometry - New biomarkers for biogeochemistry and microbial ecology. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 18:617–628. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pearson A, McNichol AP, Benitez-Nelson BC, Hayes JM, Eglinton TI. 2001. Origins of lipid biomarkers in Santa Monica Basin surface sediment: a case study using compound-specific Δ14C analysis. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 65:3123–3137. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00657-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Perry GJ, Volkman JK, Johns RB, Bavor HJ. 1979. Fatty acids of bacterial origin in contemporary marine sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 43:1715–1725. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(79)90020-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shen VK, Siderius DW, Krekelberg WP, Hatch HW. 2017. NIST Standard Reference Simulation Website, 173rd ed National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg MD. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Close HG, Wakeham SG, Pearson A. 2014. Lipid and13C signatures of submicron and suspended particulate organic matter in the Eastern Tropical North Pacific: implications for the contribution of Bacteria. Deep Sea Res 1 Oceanogr Res Pap 85:15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2013.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang Y, Wen Z, Washburn MP, Florens L. 2010. Refinements to label free proteome quantitation: how to deal with peptides shared by multiple proteins. Anal Chem 82:2272–2281. doi: 10.1021/ac9023999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]