ABSTRACT

Understanding the facilitator of HIV-1 infection and subsequent latency establishment may aid the discovery of potential therapeutic targets. Here, we report the elevation of plasma transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) during acute HIV-1 infection among men who have sex with men (MSM). Using a serum-free in vitro system, we further delineated the role of TGF-β signaling in mediating HIV-1 infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. TGF-β could upregulate both the frequency and expression of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5, thereby augmenting CCR5-tropic viral infection of resting and activated memory CD4+ T cells via Smad3 activation. The production of live HIV-1JR-FL upon infection and reactivation was increased in TGF-β-treated resting memory CD4+ T cells without increasing CD4 expression or inducing T cell activation. The expression of CCR7, a central memory T cell marker that serves as a chemokine receptor to facilitate T cell trafficking into lymphoid organs, was also elevated on TGF-β-treated resting and activated memory CD4+ T cells. Moreover, the expression of CXCR3, a chemokine receptor recently reported to facilitate CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection, was increased on resting and activated memory CD4+ T cells upon TGF-β treatment. These findings were coherent with the observation that ex vivo CCR5 and CXCR3 expression on total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells in combination antiretroviral therapy (cART)-naive and cART-treated patients were higher than in healthy individuals. Overall, the study demonstrated that TGF-β upregulation induced by acute HIV-1 infection might promote latency reservoir establishment by increasing infected resting memory CD4+ T cells and lymphoid organ homing of infected central memory CD4+ T cells. Therefore, TGF-β blockade may serve as a potential supplementary regimen for HIV-1 functional cure by reducing viral latency.

IMPORTANCE Incomplete eradication of HIV-1 latency reservoirs remains the major hurdle in achieving a complete HIV/AIDS cure. Dissecting the facilitator of latency reservoir establishment may aid the discovery of druggable targets for HIV-1 cure. This study showed that the T cell immunomodulatory cytokine TGF-β was upregulated during the acute phase of infection. Using an in vitro serum-free system, we specifically delineated that TGF-β promoted HIV-1 infection of both resting and activated memory CD4+ T cells via the induction of host CCR5 coreceptor. Moreover, TGF-β-upregulated CCR7 or CXCR3 might promote HIV-1 latent infection by facilitating lymphoid homing or IP-10-mediated viral entry and DNA integration, respectively. Infected resting and central memory CD4+ T cells are important latency reservoirs. Increased infection of these cells mediated by TGF-β will promote latency reservoir establishment during early infection. This study, therefore, highlighted the potential use of TGF-β blockade as a supplementary regimen with cART in acute patients to reduce viral latency.

KEYWORDS: activated memory CD4 T cells, CCR5-tropic infection, human immunodeficiency virus, resting memory CD4 T cells, TGF-β

INTRODUCTION

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) remains the most effective long-term treatment regimen for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals. While functional cure is defined as sustained viremia suppression in the absence of cART, sterilizing cure is defined as the complete elimination of replication-competent virus (1). Establishment of the HIV-1 latency reservoir is an early event, and viral latency remains the major hurdle in achieving a functional cure. To date, no optimal cART can eliminate the latent virus with viral rebound observed upon cART cessation. Therefore, understanding the mechanism of latency reservoir establishment may facilitate the discovery of potential therapeutic targets. Different CD4+ T cell subsets contribute to the major source of latency reservoirs. The concept of latency reservoir formation has been modified over the years owing to technical platform advancement, e.g., single-cell transcriptome analysis, and this has been extensively reviewed by others (1, 2). A commonly accepted definition of latency reservoir is an infected cell existing in a long-term resting state in which the replication-competent viral genome persists indefinitely (2). Resting CD4+ T cells harboring provirus were considered the “classic” latency reservoir in the past decades. Interestingly, the formation and maintenance of resting CD4+ T cell latency reservoir via clonal expansion are dynamic, although infected individuals are on optimal cART. Different mechanisms of latency reservoir maintenance have been described, including viral integration in or near genes that are associated with cell growth, homeostatic proliferation, and antigen-driven proliferation (2). More recently, the concept of “active reservoir” has been proposed in which minute populations of infected cells harboring the provirus are transcriptionally active and produce viral RNA or proteins (2). These infected cells express T cell activation markers, suggesting that the latent reservoir is in an activated rather than the “classic” resting state (2–4). Thus, preventing latency reservoir establishment via reducing infection of both activated and resting CD4+ T cell subsets during the acute infection phase is a promising strategy to achieve functional cure.

Studies showed that early cART was effective in reducing the size and diversity of latency reservoirs (5, 6), most likely owing to the reduction of infected cells. Cytokines that suppress T cell function, such as interleukin 10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), are upregulated during HIV-1 infection (7, 8). However, whether the upregulation of these cytokines is the outcome of a normal immune response against viral infection or whether they do mediate HIV-1 infection remains unclear. TGF-β is a T helper 1 (Th1)-inhibitory cytokine (9). It also restricts the expression of the cytotoxicity-related molecule CD107a in CD4+ T cells of HIV-1 patients (10). Interestingly, it was reported that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of HIV-1-infected patients with defective T cell responses produced more TGF-β and that blocking TGF-β in vitro restored T cell function (9, 11). TGF-β level was also inversely correlated with CD4+ T cell count or CD4/CD8 ratio (12). In addition, the number of TGF-β-producing regulatory T (Treg) cells was increased in the mucosa and lymphoid tissues of patients, which was associated with disease progression (13–15). These studies suggest that TGF-β may play a pathological role in HIV-1 infection by suppressing T cell functions. As for HIV-1 latency, it is well established that different memory CD4+ T cell subsets are important latency reservoirs (16–19). Our group previously reported that among these memory CD4+ T cells, TGF-β promoted the reverse differentiation of HIV-1-infected effector memory cells into latent central memory cells by upregulation of the chemokine receptor CCR7 (20). The present study, therefore, further focused on understanding the role of TGF-β in mediating HIV-1 infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. Using a serum-free in vitro system, we aimed to delineate whether TGF-β modulates the expression of CCR5, an HIV-1 coreceptor of the major transmitting strains during acute infection. Whether TGF-β facilitates HIV-1 infection in activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells was also investigated. Moreover, expressions of CCR7 and CXCR3, a central memory T cell marker that facilitates lymph node homing and a chemokine receptor that promotes HIV infection on resting CD4+ T cells, respectively, were evaluated in parallel to delineate the possible role of TGF-β in mediating HIV-1 infection via other mechanisms (21–23).

RESULTS

TGF-β increases the expression of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells via Smad3.

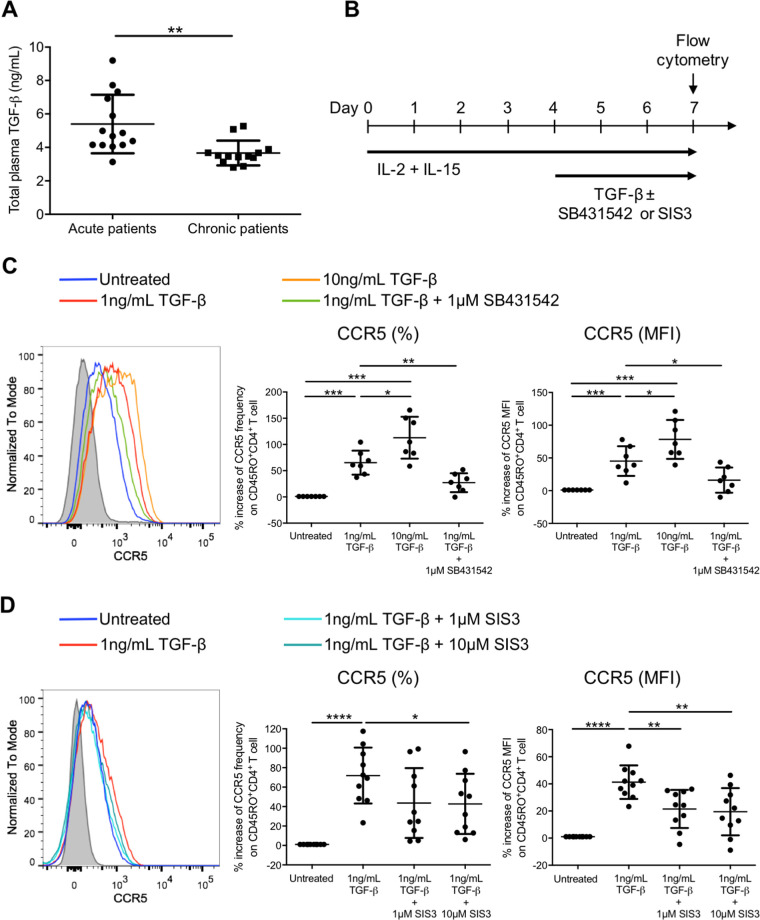

Direct HIV-1 infection on CD4+ T cell during the acute phase contributes to HIV-1 latency reservoir establishment, when a minority of the infected host cells return to their resting states after activation. It is of interest whether any T cell-inhibitory cytokines are elevated during HIV-1 acute infection and whether these cytokines can mediate HIV-1 infection and latency establishment. Therefore, we focused on TGF-β, a cytokine that suppresses T helper 1 (Th1) while promoting Treg cell differentiation (9, 24). Our results showed that the plasma TGF-β level in acute patients was higher than that in chronic patients (5.40 ± 1.75 ng/mL versus 3.66 ± 0.74 ng/mL) (Fig. 1A), suggesting that TGF-β might directly modulate HIV-1 infection in addition to T cell suppression during acute HIV-1 infection. Since memory CD4+ T cells are important HIV-1 latency reservoirs, we hypothesized that TGF-β could modulate HIV-1 coreceptor expression on activated memory CD4+ T cells during the acute infection phase. Using a serum-free system that eliminated the possible influence of the conserved TGF-β present in the fetal calf serum within the culture system, we evaluated whether human TGF-β could increase the expression of CCR5, an important HIV-1 coreceptor for HIV-1 entry into CD4+ T cells (19). Purified memory CD45RO+ CD4+ T cells were first stimulated with the T cell-activating cytokines IL-2 and IL-15 for 4 days, followed by the addition of TGF-β for 3 days in the absence or presence of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542 (25) (Fig. 1B). Memory CD4+ T cells acquired an activated phenotype after IL-2 and IL-15 stimulation as shown by the induction of different T cell activation markers, including CD25, CD69, and HLA-DR, and an increase in cell size and cellular granularity (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These activated memory CD4+ T cells were treated with TGF-β for subsequent experiments.

FIG 1.

TGF-β increases the frequency and expression level of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 on activated memory CD4+ T cells via Smad3. (A) Plasma TGF-β levels in acute and chronic HIV-1 patients were compared. Plasma samples of patients were heat inactivated, and the level of TGF-β in plasma was determined by ELISA. (B) Schematic diagram showing in vitro activation and TGF-β treatment of purified CD45RO+ memory CD4+ T cells. Purified memory CD4+ T cells were activated by IL-2 (10 ng/mL) and IL-15 (20 ng/mL) for 4 days, followed by the addition of TGF-β (1 ng/mL or 10 ng/mL) for 3 days in the absence or presence of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542 (1 μM) or the Smad3 inhibitor SIS3 (1 or 10 μM). The expression of CCR5 was subsequently evaluated using flow cytometry analysis. (C and D) Representative flow cytometry histogram and cumulative dot plots comparing the relative increase in frequency and expression (MFI) of CCR5 on purified activated memory CD4+ T cells compared with the untreated control in the presence of SB431542 (C) or SIS3 (D). For panels A, C, and D, each symbol represents an individual donor. The unpaired Student t test was used for statistical analysis (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001).

The results showed that TGF-β could increase CCR5 frequency by 65.3% ± 23.0% and expression (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) by 45.2% ± 22.6% on activated memory CD4+ T cells after treating with 1 ng/mL TGF-β compared with the untreated control (Fig. 1C). Moreover, the induction of CCR5 frequency and expression had further increased to 112.9% ± 40.0% and 78.4% ± 29.8%, respectively, when the concentration of TGF-β was increased to 10 ng/mL (Fig. 1C). This suggested that CCR5 induction by TGF-β was dose dependent. Abruption of TGF-β signaling via the addition of SB431542 reverted the induction of CCR5 by TGF-β, demonstrating that CCR5 induction was dependent on TGF-β signaling (Fig. 1C). Smad3 is a relatively upstream transcription factor within the TGF-β signaling pathway. It phosphorylates and translocates into the nucleus to mediate transcription of genes responsible for T cell activation and functions (26). We therefore further evaluated whether Smad3 was involved in mediating CCR5 induction using the Smad3-specific phosphorylation inhibitor SIS3. The results showed that SIS3 reverted the induction of CCR5 on activated memory CD4+ T cells by TGF-β, indicating that Smad3 was involved in controlling CCR5 expression (Fig. 1D).

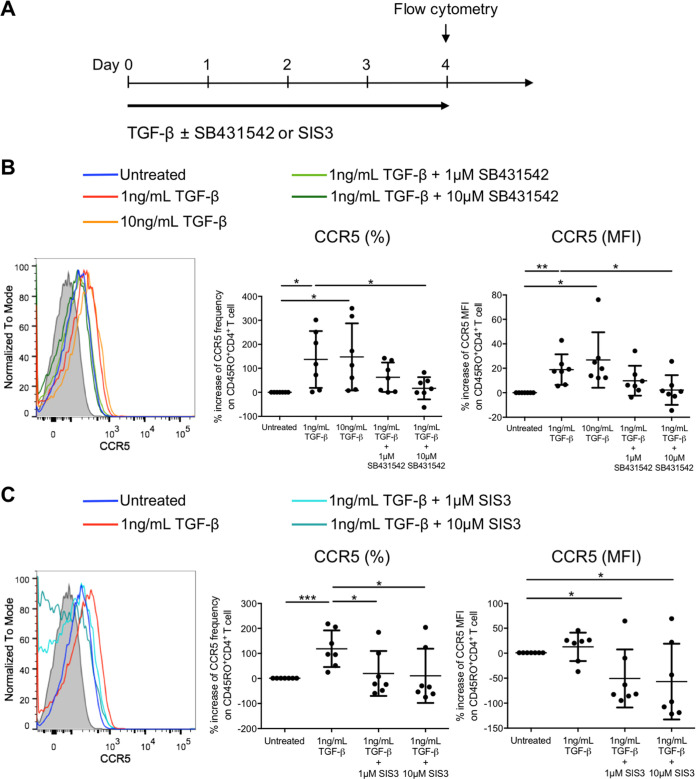

We next investigated whether TGF-β could increase CCR5 expression on resting memory CD4+ T cells, a CD4+ T cell subtype that serves as an important HIV-1 latency reservoir. Purified CD4+ CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− CD45RO+ resting memory CD4+ T cells were treated with TGF-β for 4 days in the absence or presence of SB431542 (Fig. 2A). In line with the observation in activated memory CD4+ T cells, TGF-β also increased CCR5 mean frequency by 136.9% ± 118.4% and the expression (MFI) by 18.9% ± 12.5% on resting memory CD4+ T cells treated with 1 ng/mL of TGF-β (Fig. 2B). However, increasing the TGF-β concentration to 10 ng/mL could not further promote CCR5 induction on resting memory CD4+ T cells. The addition of SB431542 reverted the induction of CCR5, which confirmed that the increase in CCR5 on resting memory CD4+ T cells was TGF-β signaling dependent (Fig. 2B). Similarly, addition of SIS3 reverted the CCR5 induction, indicating that CCR5 induction by TGF-β was Smad3 dependent in resting memory CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2C).

FIG 2.

TGF-β increases the frequency and expression level of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 on resting memory CD4+ T cells via Smad3. (A) Schematic diagram showing in vitro TGF-β treatment (1 or 10 ng/mL) of purified CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− CD45RO+ resting memory CD4+ T cells in the absence or presence of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542 (1 or 10 μM) or the Smad3 inhibitor SIS3 (1 or 10 μM) for 4 days, followed by flow cytometry analysis to evaluate CCR5 expression on resting memory CD4+ T cells after TGF-β treatment. (B and C) Representative flow cytometry histogram and cumulative dot plots comparing the relative increase in frequency and expression (MFI) of CCR5 on purified resting memory CD4+ T cells compared with the untreated control in the presence of SB431542 (B) or SIS3 (C). Each symbol represents an individual donor. The unpaired Student t test was used for statistical analysis (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01).

TGF-β increases CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells.

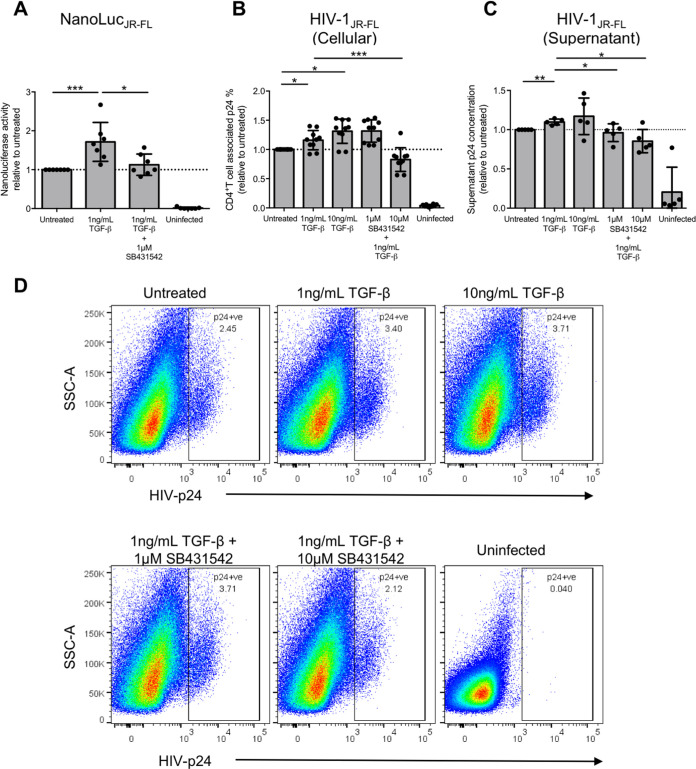

The above results implied that elevated TGF-β during HIV-1 acute infection might increase CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection on both activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells via increasing CCR5 expression. Moreover, infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells would directly contribute to HIV-1 latency reservoir establishment, leading to a viral rebound in the absence of cART upon reactivation. We therefore evaluated whether TGF-β could increase CCR5-tropic infection of purified resting memory CD4+ T cells. We used a NanoLucJR-FL pseudovirus system consisting of the tier 2 envelope JR-FL, with a nanoluciferase reporter in its pNL4-3.Luc.R-E- backbone to infect TGF-β treated resting memory CD4+ T cells as described above. Cells were then reactivated on the next day after infection by T cell receptor stimulation using anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. The results showed that 1 ng/mL of TGF-β could increase CCR5-tropic infection by around 71.5% ± 49.9% relative to the untreated control, and the addition of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542 reverted the increased infection (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

TGF-β increases CCR5-tropic live HIV-1 infection and viral production of resting memory CD4+ T cells. Purified CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− CD45RO+ resting memory CD4+ T cells were treated with TGF-β in the absence or presence of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542, followed by infection of NanoLucJR-FL CCR5-tropic HIV-1 pseudovirus that carried a nanoluciferase reporter in the nef gene of the pseudovirus backbone. The nanoluciferase reading in the supernatant was measured 7 days after infection to evaluate infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells upon TGF-β treatment. (A) Cumulative dot plot showing nanoluciferase activity relative to that of the untreated control. (B) TGF-β treated purified resting memory CD4+ T cells were infected with live HIV-1JR-FL, and T cell-associated p24 was determined by flow cytometry analysis to evaluate HIV-1 infection. The cumulative dot plots show the changes of live HIV-1JR-FL infection on resting memory CD4+ T cells relative to the untreated control. (C) TGF-β-treated purified resting memory CD4+ T cells were infected with live HIV-1JR-FL. The cumulative dot plot shows the increase in HIV-1JR-FL production relative to the untreated control by evaluating the quantity of p24 in the culture supernatant using ELISA after reactivation by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation from 2 independent experiments (n = 5). For panels A to C, each symbol represents an individual donor. The unpaired Student t test was used for statistical analysis (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001). (D) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the gating of T cell-associated p24 on resting memory CD4+ T cells for evaluating live HIV-1JR-FL infection by flow cytometry after TGF-β treatment.

To confirm the phenomena, the experiment was repeated using the CCR5-tropic tier 2 live virus HIV-1JR-FL. The results showed that TGF-β also increased CCR5-tropic live HIV-1 infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells for around 15.9% ± 16.4% as evaluated by HIV-1 p24 frequency on resting memory CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3B and D). In line with the CCR5 induction (Fig. 2B), increasing the TGF-β concentration did not further promote CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection. The addition of 10 μM SB431542 reverted the increase of TGF-β-induced infection to 0.83% ± 0.20% i.e., a level even lower than that of the untreated control. Since activated CD4+ T cells are more susceptible to HIV-1 infection, we further confirmed the activation status of TGF-β-treated resting memory CD4+ T cells by evaluating the expression of different T cell activation markers. The results showed that TGF-β did not induce the expression of CD25, CD69, or HLA-DR on resting memory CD4+ T cells, thereby confirming that the increase of infection was not due to the activation of resting memory CD4+ T cells by TGF-β (Fig. S2). Taken together, our findings show that TGF-β signaling could promote CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection on resting memory CD4+ T cells via the induction of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5.

Since TGF-β could increase CCR5-tropic infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells, we next evaluated whether these TGF-β-treated cells could increase the amount of viral production after infection and reactivation by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation. The p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to quantify the amount of virus produced after reactivation. In two independent experiments (n = 5), the results showed that resting memory CD4+ T cells treated with 1 ng/mL of TGF-β produced more HIV-1JR-FL after infection and reactivation, with the increase of viral production reverted when TGF-β signaling was blocked by SB431542 (Fig. 3C). Together, the results showed that TGF-β not only facilitated HIV-1 latency establishment by promoting the infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells but also increased viral production upon reactivation from its latent state to facilitate HIV-1 progression.

Increased CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection is mediated via Smad3 within the TGF-β signaling pathway.

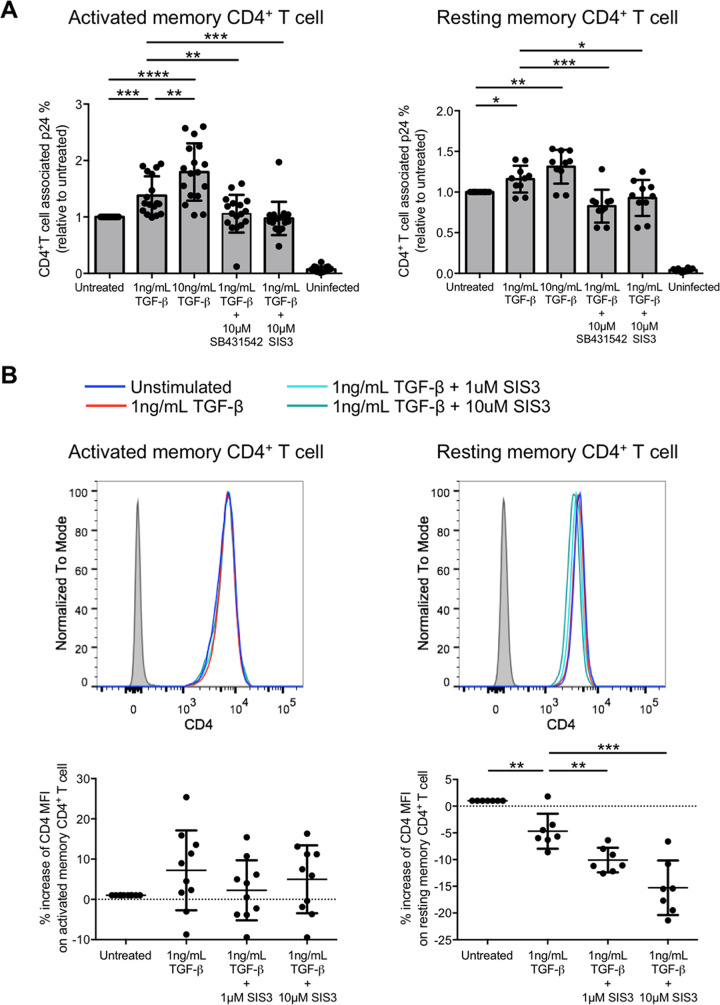

Whether Smad3 was responsible for promoting CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection was also evaluated by live HIV-1JR-FL infection. The results showed that 1 ng/mL of TGF-β could increase the infection of purified CD45RO+ activated memory CD4+ T cells by 37.9% ± 34.2% relative to the untreated control and that increasing the TGF-β concentration to 10 ng/mL further increased the infection to 79.6% ± 50.7%. (Fig. 4A, left; Fig. S3A). The data indicated that the increased infection of activated memory CD4+ T cells was TGF-β dose dependent. The addition of SIS3 to inhibit Smad3 phosphorylation abolished the induction of infection by TGF-β to a level comparable to complete TGF-β signaling abrogation by SB431542. Similarly, inhibiting TGF-β signaling and Smad3 phosphorylation by SIS3 also reverted the TGF-β-induced HIV-1 infection on purified resting memory CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4A, right; Fig. S3B).

FIG 4.

TGF-β increases CCR5-tropic live HIV-1JR-FL infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells via Smad3 phosphorylation. (A) Purified activated CD45RO+ activated memory CD4+ T cells (left) and purified CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− CD45RO+ resting memory CD4+ T cells (right) were treated with TGF-β in the absence or presence of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542 or Smad3 inhibitor SIS3 (10 μM). Cells were then infected with live HIV-1JR-FL and T cell-associated p24 was determined 3 days after infection by flow cytometry. (B) CD4 expression level on purified activated (left) and resting (right) memory CD4+ T cells was evaluated by flow cytometry analysis after TGF-β treatment as mentioned above. The top shows the representative flow cytometry histogram, and the bottom shows cumulative dot plots of relative CD4 expression (MFI) compared with the untreated control. For both panels, each symbol represents an individual donor. The unpaired Student t test was used for statistical analysis (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001).

Since increased infection might also be due to an induction of CD4 that serves as an HIV-1 primary receptor, we evaluated CD4 expression on both resting and activated memory CD4+ T cells upon TGF-β treatment. CD4 expression on activated memory CD4+ T cells remained unchanged upon TGF-β and SIS3 treatment (Fig. 4B, left). Interestingly, CD4 expression on resting memory CD4+ T cells slightly decreased by 4.69% ± 3.27% upon TGF-β treatment. The expression further decreased after Smad3 inhibition with 1 μM SIS3, by 10.1% ± 2.31%, compared to the untreated control (Fig. 4B, right). Suppressed CD4 expression by Smad3 inhibition was SIS3 dose dependent, since increasing the SIS3 concentration to 10 μM further reduced CD4 expression by 15.3% ± 5.11%. Overall, the data suggested that Smad3 was responsible for the increased CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection via the induction of CCR5 on both activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. Moreover, infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells increased even when CD4 expression decreased upon TGF-β treatment. This further demonstrated the importance of CCR5 as a key coreceptor in mediating HIV-1 infection in resting memory CD4+ T cells.

TGF-β upregulates HIV-1 infection-related chemokine receptors CCR7 and CXCR3 on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells.

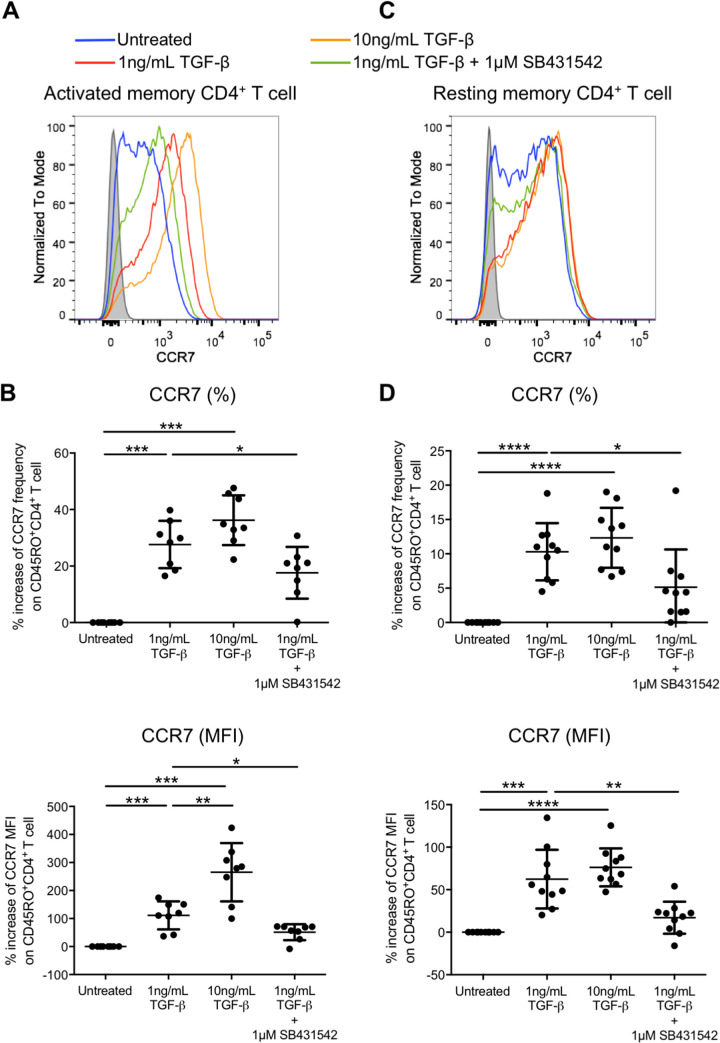

Migration of CD4+ T cells to the secondary lymphoid organ is essential for T cell priming during viral infection. The central memory T cell marker CCR7 is a chemokine receptor that directs T cell migration to secondary lymphoid organs via binding of its ligand CCL19 and CCL21 (22, 23). CCR7 is involved in the progression of HIV-1 infection and dissemination by directing T cells into lymphoid organs, where infected and uninfected cells encounter each other. Central memory CD4+ T cells are also reported as important latency reservoirs (16, 27, 28). We therefore evaluated whether TGF-β could promote CCR7 expression on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. The results showed that 1 ng/mL of TGF-β increased both the frequency and expression (MFI) on activated memory CD4+ T cells by 27.64% ± 8.37% and 111.4% ± 49.9%, respectively, compared with the untreated control (Fig. 5A and B). Moreover, induction of CCR7 expression (MFI) further increased to 265.3% ± 104.1% after the TGF-β concentration was increased to 10 ng/mL. Similarly, 1 ng/mL of TGF-β also promoted CCR7 frequency and expression (MFI) on resting memory CD4+ T cells with an increase of 10.3% ± 4.17% and 62.4% ± 34.6%, respectively. However, increasing TGF-β concentration could not further promote CCR7 expression (Fig. 5C and D). The data suggested that TGF-β could promote the progression of HIV-1 infection by facilitating the trafficking of HIV-1-infected and uninfected cells into lymphoid organs. Thus, increasing their chance of contact might escalate the infection of uninfected cells.

FIG 5.

TGF-β increases the frequency and expression level of the central memory marker CCR7 on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. Purified CD45RO+ activated memory (A and B) or purified CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− CD45RO+ resting memory (C and D) CD4+ T cells were treated with TGF-β in the absence or presence of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542. The expression of CCR7 was subsequently evaluated by flow cytometry analysis. Representative flow cytometry histograms of CCR7 expression on activated (A) and resting (C) memory CD4+ T cells are shown, and the cumulative dot plots show the increase of frequency and expression (MFI) of activated (B) and resting (D) memory CD4+ T cells relative to the untreated control. Each symbol represents an individual donor. The unpaired Student t test was used for statistical analysis (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001).

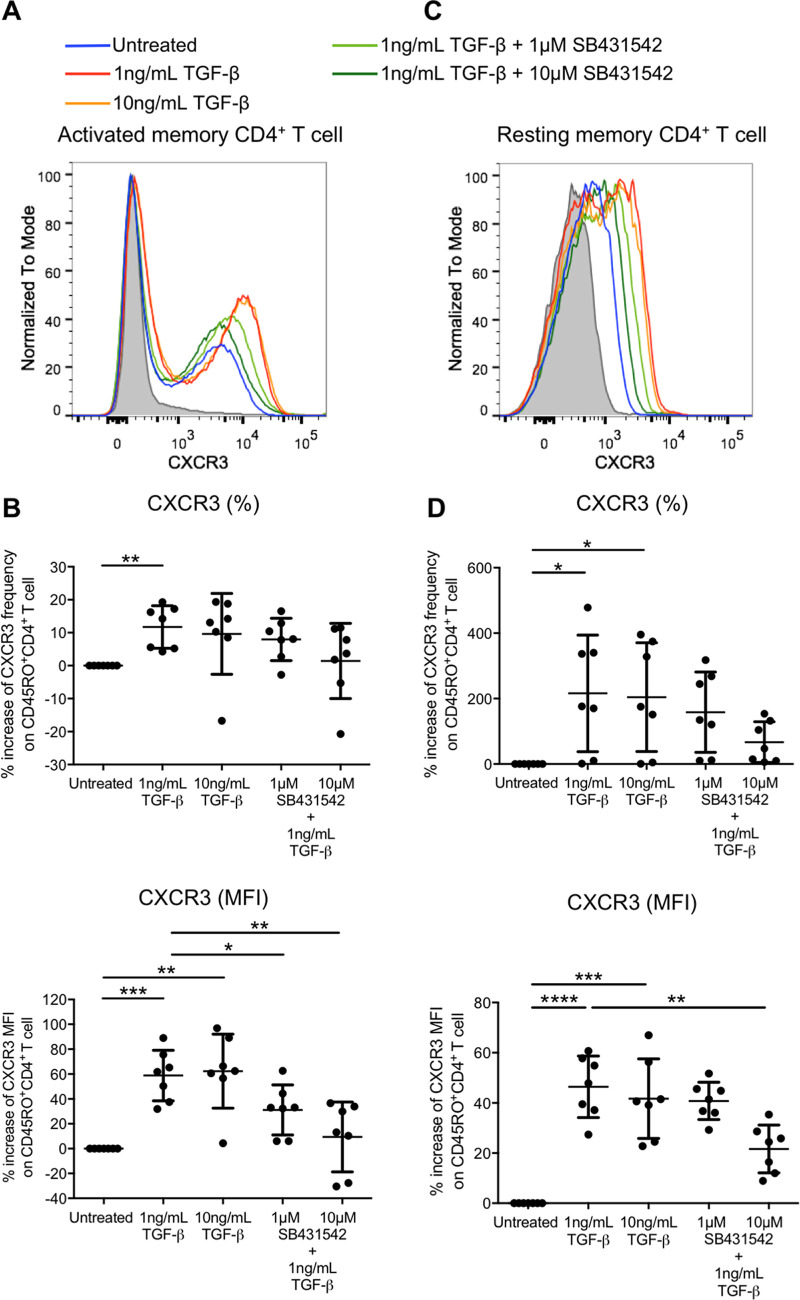

It was recently reported that CXCR3 via its ligand IP-10 promotes latent HIV infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells (21). We therefore evaluated whether TGF-β could increase CXCR3 expression on both activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. The results showed that 1 ng/mL of TGF-β increased CXCR3 expression (MFI) on purified activated CD45RO+ memory CD4+ T cells (58.5% ± 20.4%) (Fig. 6A and B). CXCR3 expression (MFI) on resting memory CD4+ T cells evaluated by gating on CD45RO+ cells in purified resting CD4+ T cells was also increased (46.5% ± 12.3%) (Fig. 6C and D). However, increasing the TGF-β concentration could not further promote CXCR3 expression of both memory cell types. Abruption of TGF-β signaling by SB431542 reverted the increased CXCR3 expression. The frequency of CXCR3 on active (Fig. 6A and B) and resting (Fig. 6C and D) memory CD4+ T cells also increased, by 11.7% ± 6.45% and 216.1% ± 178.3%, respectively, upon treatment with 1 ng/mL of TGF-β. Although the abruption of TGF-β signaling by 10 μM SB431542 had a trend of reducing the induced CXCR3 frequency, the reduction did not reach statistical significance.

FIG 6.

TGF-β increases CXCR3 expression on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. Purified CD45RO+ CD4+ activated memory (A and B) or purified CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− CD4+ cells gated on CD45RO+ resting memory (C and D) T cells were treated with TGF-β in the absence or presence of the TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542. The expression of CXCR3 was subsequently evaluated by flow cytometry analysis. Representative flow cytometry histograms of CXCR3 expression on activated (A) and resting (C) memory CD4+ T cells are shown, and the cumulative dot plots show relative frequency and expression (MFI) of activated (B) and resting (D) memory CD4+ T cells compared to the untreated control. Each symbol represents an individual donor. The unpaired Student t test was used for statistical analysis (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001).

Clinical relevance of CCR5 and CXCR3 expression on total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells in HIV-1 infection.

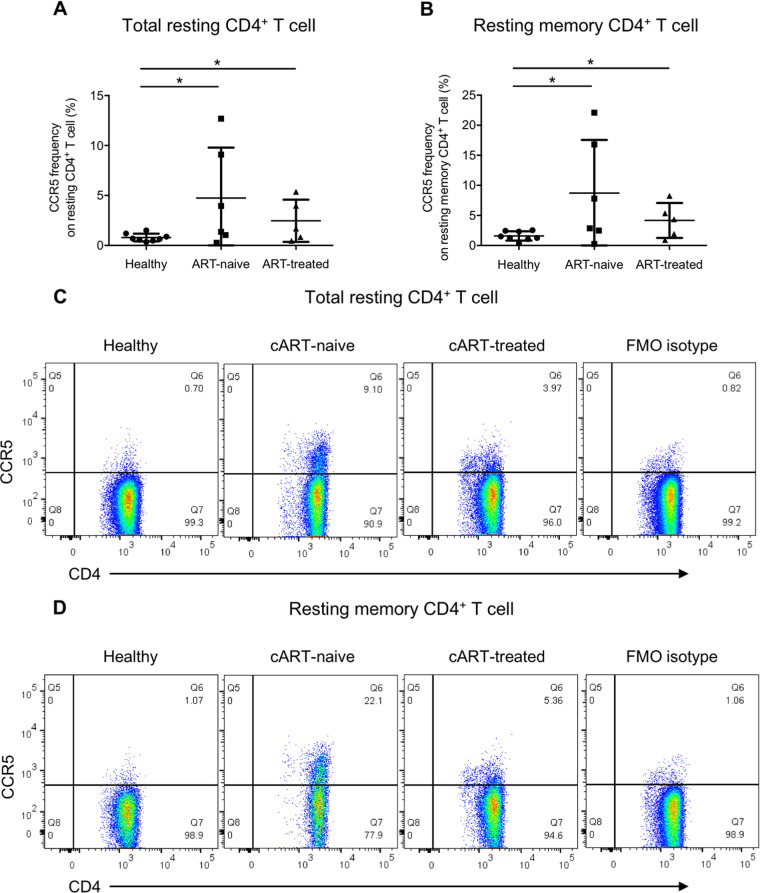

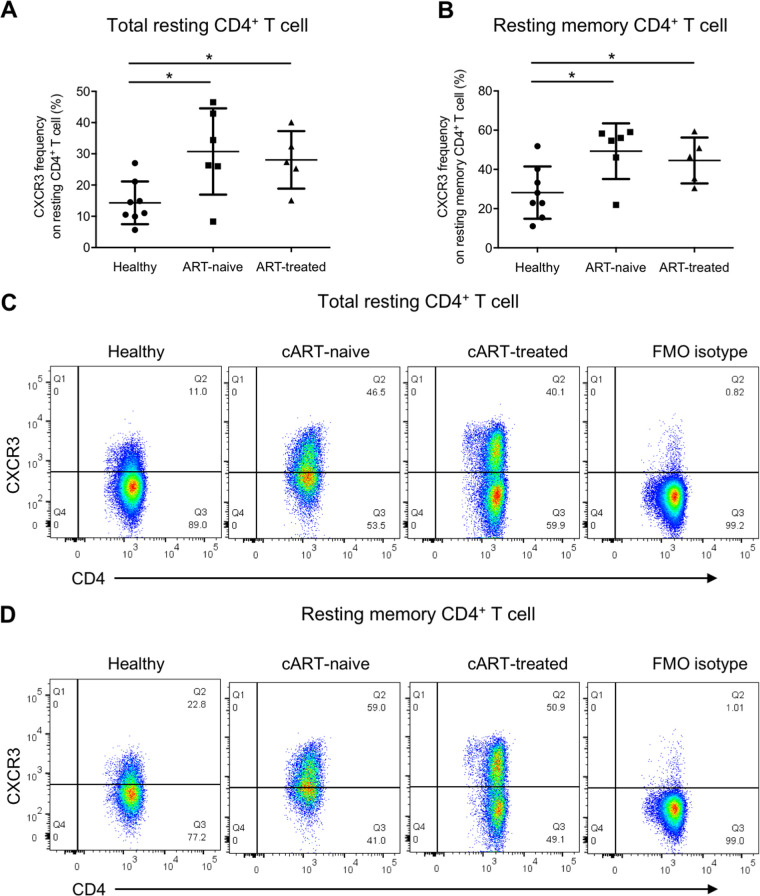

Our in vitro data suggested that increased plasma TGF-β during acute HIV-1 infection could enhance HIV-1 infection in activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells by promoting CCR5 and CXCR3 expressions. To support the above speculation, we further compared the ex vivo frequencies of CCR5- and CXCR3-expressing cells in total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells among ART-naive patients, ART-treated patients and healthy controls. Coherent with the observation from the in vitro TGF-β treatment experiment, both ART-naive and ART-treated HIV-1 patients had a higher frequency of CCR5-expressing total resting CD4+ T cells than healthy controls (0.79 ± 0.39 versus 4.74 ± 5.06 versus 2.47 ± 2.12) (Fig. 7A and C), with a similar observation for CXCR3 (14.3% ± 6.84% versus 30.7% ± 13.8% versus 28.1% ± 9.22%) (Fig. 8A and C). The frequencies of CCR5-expressing resting memory CD4+ T cells in both patient groups were also higher than in healthy controls (1.60 ± 0.77 versus 8.72 ± 8.83 versus 4.17 ± 2.91) (Fig. 7B and D). A similar finding was observed for CXCR3 in which its expressions on resting memory CD4+ T cells in both ART-naive and ART-treated HIV-1 patients were higher than in healthy controls (28.2% ± 13.3% versus 49.3% ± 14.2% versus 44.5% ± 11.7%) (Fig. 8B and D). The data suggested that both total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells in patients were more susceptible to HIV-1 infection, especially during the acute infection phase when the plasma viral load was high, thereby increasing the chance of HIV-1 latency reservoir establishment in infected individuals.

FIG 7.

CCR5 frequency on total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells is elevated in cART-naive and cART-treated HIV-1 patients. Total PBMCs from cART-naive patients, cART-treated patients, and healthy donors were stained for CCR5 with the T cell and T cell activation markers CD3, CD4, CD69, CD25, and HLA-DR and the memory T cell marker CD45RO, followed by flow cytometry analysis. Ex vivo CCR5 frequency on total resting CD4+ T cells was evaluated by gating on CD3+ CD4+ CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− T cells, and that on resting memory CD4+ T cells was evaluated by gating on CD3+ CD4+ CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− CD45RO+ T cells. Cumulative dot plots show the ex vivo CCR5 frequencies on total resting (A) and resting memory (B) CD4+ T cells among cART-naive patients, cART-treated patients, and healthy donors. Representative flow cytometry plots of total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells are also shown in panels C and D, respectively. The FMO isotype control was pooled from all samples for isotype staining. Each symbol represents an individual donor. The unpaired Student t test was used for statistical analysis (*, P ≤ 0.05).

FIG 8.

CXCR3 frequency on total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells is elevated in cART-naive and cART-treated HIV-1 patients. Total PBMCs from cART-naive patients, cART-treated patients, and healthy donors were stained for CXCR3 with the T cell and T cell activation markers CD3, CD4, CD69, CD25, and HLA-DR and the memory T cell marker CD45RO, followed by flow cytometry analysis. Ex vivo CXCR3 frequency on total resting CD4+ T cells was evaluated by gating on CD3+ CD4+ CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− T cells, and that on resting memory CD4+ T cells was evaluated by gating on CD3+ CD4+ CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− CD45RO+ T cells. Cumulative dot plots show ex vivo CXCR3 frequencies on total resting (A) and resting memory (B) CD4+ T cells among cART-naive patients, cART-treated patients, and healthy donors. Representative flow cytometry plots of total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells are also shown in panels C and D, respectively. The FMO isotype control was pooled from all samples for isotype staining. Each symbol represents an individual donor. The unpaired Student t test was used for statistical analysis (*, P ≤ 0.05).

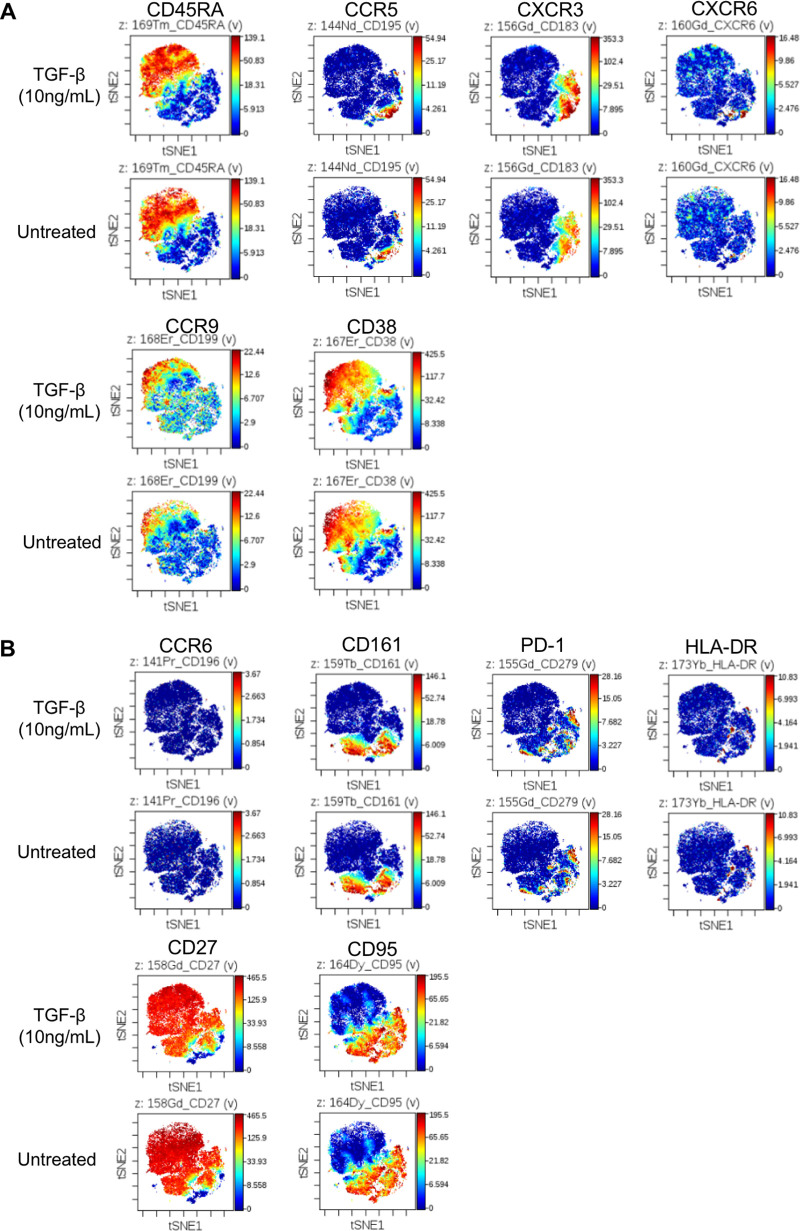

Whether TGF-β can cause any induction of pan-chemokine receptors or CD4+ T cell subtype markers remains an interesting question. To overcome the limitation of increasing detection parameters owing to matrix compensation in flow cytometry, we performed a single experiment using mass cytometry (CyTOF) to evaluate whether there were any expression changes on resting memory CD4+ T cells. Purified CD25− CD69− HLA-DR− resting CD4+ T cells were subjected to CyTOF analysis. To distinguish resting memory CD4+ T cells, the samples were tagged with the naive T cell marker CD45RA, where resting memory CD4+ T cells were identified as the CD45RA− population. The results showed that the expressions of some targets were upregulated (Fig. 9A), while some remained unchanged or downregulated (Fig. 9B) after TGF-β treatment. In line with the data from flow cytometry, resting memory CD4+ T cells expressed higher levels of CCR5 and CXCR3 upon TGF-β treatment (Fig. 9A). On the other hand, TGF-β did not affect the expression of the following: the chemokine receptor CCR6, for which latent virus was found in CXCR6+ CXCR3+ CD4+ T cells (29); the IL-17-producing-cell marker CD161, for which CD161+ CD4+ cells were also reported to harbor latent HIV (30, 31); or the T cell exhaustion marker PD-1 (Fig. 9B). Therefore, our data showed that TGF-β did not induce a pan-chemokine receptor upregulation, thus highlighting its role in increasing HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 in the context of HIV-1 infection on resting memory CD4+ T cells.

FIG 9.

TGF-β does not induce pan-chemokine receptor upregulation on resting memory CD4+ T cells. Total resting CD4+ T cells were either treated with 10 ng/mL or TGF-β or left untreated for 4 days, followed by antibody staining and CyTOF analysis. Resting memory CD4+ T cells were identified as CD45RA− cells on the top left of panel A. Targets with expression upregulation after TGF-β treatment are illustrated in panel A, except the CD45RA marker for distinguishing the naive or memory cells. Targets without expression changes or downregulated are illustrated in panel B. The experiment was conducted once as a preliminary experiment.

DISCUSSION

Although cART can effectively control HIV-1, the persistence of the latent virus in resting CD4+ T cells remains a major hurdle in achieving functional and sterilizing cure upon cART cessation. Understanding the mechanism of HIV-1 latency establishment is therefore crucial in facilitating the discovery of potential therapeutic targets. In this study, we observed an increased level of plasma TGF-β in acute patients, suggesting that TGF-β might have an early role in mediating HIV-1 infection. Using a serum-free in vitro infection system, we delineated that TGF-β promoted the expression of HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells via Smad3, an upstream transcription factor within the TGF-β signaling pathway. TGF-β, therefore, increased subsequent CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells and viral production from resting memory CD4+ T cells after reactivation. TGF-β also increased the expression of CCR7, the central memory T cell marker that is known to direct T cell trafficking into lymphoid organs on both activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, the chemokine receptor CXCR3 was also upregulated by TGF-β in which CXCR3 could facilitate HIV-1 infection on resting CD4+ T cells (21). The findings were coherent with the observation that both CCR5 and CXCR3 frequencies on ex vivo total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells from cART-naive and cART-treated patients were higher than healthy controls. The current study, therefore, unwinds the role of TGF-β in promoting HIV-1 infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells via CCR5 induction. We anticipated that TGF-β-induced CCR7 upregulation might also play a role in facilitating activated and resting memory CD4+ T migration into the lymphoid organs to increase the encountering of infected and uninfected cells, with CXCR3 upregulation promoting HIV-1 infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells during the acute phase.

During the course of acute viral infection and tissue damage, upregulation of Th1- and Th2-suppressive cytokines, including TGF-β, is a natural immune regulatory mechanism to prevent excessive T cell responses. Platelets are one of the major sources of circulating TGF-β (32). The level of TGF-β during acute HIV-1 infection was reported to be elevated in the circulation as early as 1 to 4 days, and the positive correlation between platelet activation and plasma TGF-β suggested that platelets might be a possible source of TGF-β upregulation during HIV-1 infection (8). PBMCs from HIV-1 patients also produce a larger amount of TGF-β upon stimulation, with a higher level of plasma TGF-β detected in more severe disease (11, 12, 33). Interestingly, HIV-1 itself can also promote TGF-β expression in infected individuals. It was reported that the regulatory protein Tat, a transactivator of HIV-1 transcription, directly contributed to TGF-β production (34, 35). Moreover, HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp160 could upregulate TGF-β transcripts through interactions between CD4 and gp160 (36). With the role of TGF-β in promoting the expression of HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 and the subsequent infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells reported herein, we and others have delineated that HIV-1 interferes with its hosts to facilitate infection during the acute infection phase via the TGF-β signaling pathway. HIV-1 CCR5 tropism is clinically more important than CXCR4 tropism during acute mucosal infection. It was reported that latency reservoirs from CD4+ T cells in cART-treated patients were mostly CCR5 tropic, with upregulated CCR5 expression in effector-to-memory transitioning CD4+ T cells to increase CCR5-tropic entry (19). The mechanism of HIV-1 latency establishment remains incompletely understood, although activated memory CD4+ T cells were proposed as important latency reservoirs in addition to resting CD4+ T cells (19). However, rapid clearance of HIV-1 by cART can greatly reduce the persistence of infected CD4+ T cells in lymphoid tissues, and vice versa if cART is started at later stages during acute infection (37). These findings suggest that in the absence of cART, increased infection in CD4+ T cells via TGF-β signaling would potentially contribute to latency establishment. It has long been reported that HIV-1 preferably infects and persists in memory CD4+ T cells, particularly in central, transitional, and effector memory CD4+ T cells, which contribute to latency reservoirs in cART-treated patients (16–18). It is likely that an increase in CCR5-tropic infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells via TGF-β upregulation promotes latency reservoir establishment in the absence of cART during natural sexual transmission.

We herein report that TGF-β reduced the expression of the HIV-1 primary receptor CD4 on resting memory CD4+ T cells, but this reduction did not abrupt the increase in TGF-β-mediated infection via CCR5 induction (Fig. 4B). This finding might highlight the importance of TGF-β and CCR5 in facilitating acute HIV-1 infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells. Unlike infection of activated memory CD4+ T cells, HIV-1 remains latent without producing or displacing any viral protein on resting memory CD4+ T cells. This allows their escape from immune surveillance and leads to latency reservoir maintenance. Therefore, direct HIV-1 infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells promoted by TGF-β has particular importance in the context of latency reservoir clearance and contributes to the hurdles in achieving a functional cure. Using the HIV-1JR-FL live-virus infection model, our data showed that TGF-β not only promoted HIV-1 infection on resting memory CD4+ T cells but also increased the amount of HIV-1 production after reactivation (Fig. 3). Our results suggested that the amount of virus produced by reactivated latent reservoirs would be increased if the size of latency reservoir was increased. The findings highlighted the impact of elevated circulating TGF-β during the acute phase in hampering HIV-1 functional cure via increasing the amount of infected resting memory CD4+ T cells, i.e., latency reservoirs capable of producing HIV-1 after reactivation. We also observed a TGF-β dose-dependent increase of CCR5 and CCR5-tropic infection on activated but not resting memory CD4+ T cells. A study reported that CCR5 mRNA expression of activated memory CD4+ T cells was much higher than its resting counterpart (38). It is possible that CCR5 induction on activated memory CD4+ T cells was more sensitive in response to TGF-β since they were more ready to produce CCR5 protein for surface expression. This may partly explain why CCR5 expression on activated memory CD4+ T cells depended on the exogenous TGF-β concentration while resting memory CD4+ T cells did not. As previously mentioned, a higher level of plasma TGF-β is detected in more severe disease (12, 33). This promotes HIV-1 infection of activated memory CD4+ T cells as the disease progresses. Moreover, a longitudinal study reported that activated memory CD4+ T cells in cART-treated patients that harbored HIV-1 provirus expanded over time, with an identical provirus sequence (3). This confirms that cART is only sufficient in suppressing provirus latency and cannot prevent the maintenance of latency reservoirs when activated memory CD4+ T cells harboring the provirus get expanded. The above suggests that the promotion of CCR5-tropic infection of activated memory CD4+ T cells by TGF-β during acute infection may play a critical role in HIV-1 latency reservoir establishment and expansion. Moreover, our data also showed that ex vivo CCR5 expression levels on total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells were higher in both cART-naive and cART-treated patients (Fig. 7), indicating that these cells may be more susceptible to HIV-1 infection during the acute infection phase when circulating TGF-β is elevated (Fig. 1A) and that this may lead to direct latency reservoir establishment. The contribution of activated CD4+ T cells to HIV-1 persistence during cART was reviewed by others, although these cells do not fulfill the definition of resting CD4+ T cells, which are considered “classic” HIV-1 latency reservoirs (2). TGF-β is also present in seminal plasma (39, 40), which may increase CCR5 expression on T cells residing in the mucosal barrier, thereby promoting HIV-1 infection of different memory CD4+ T cell subsets during HIV-1 sexual transmission. Therefore, our study provided insights for targeting TGF-β to reduce HIV-1 latency reservoir establishment in both activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells, especially during the early stage of infection.

The current study also reported the upregulation of CCR7 expression by TGF-β on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells. The chemokine receptor CCR7 is a central memory T cell marker that is also responsible for the migration of T cells into lymphoid organs (22, 23). Promoting the trafficking of CD4+ T cells into lymphoid organs will promote interactions among infected and uninfected CD4+ T cells. Studies have already reported that productively infected activated CD4+ T cells can transmit HIV-1 to resting CD4+ T cells via physical cell contact without T cell activation, and provirus generated in these cells was more difficult to induce than that generated in cell-free viral infection (41). Therefore, facilitating cell-cell contact between productively infected activated CD4+ T cells and resting memory CD4+ T cells in lymphoid organs via plasma TGF-β during the acute infection phase will increase the difficulty in complete viral eradication. Moreover, different memory CD4+ T cell subsets are more susceptible to HIV-1 infection (16–19). We previously also demonstrated that both productively and latently infected α4β7+ central memory CD4+ T cells could be differentiated from α4β7+ effector memory CD4+ T cells in the presence of TGF-β during HIV-1 infection (20). Interestingly, others also reported that the CCR7 ligand CCL19 could increase CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic HIV-1 infection of resting CD4+ T cells via activation of the downstream transcription factor NF-κB with increased HIV-1 integrase stability (42, 43). Promoting CCR7 expression on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells via elevated plasma TGF-β during acute infection may promote HIV-1 infection of these cells.

CXCR3 is a chemokine receptor highly expressed on different CD4+ T cell subsets. It directs T cell migration into inflammatory sites for antigen-specific T cell responses during infection (44–46). Whether CXCR3 plays a role in mediating HIV-1 infection has been investigated by others. For example, stimulating monocyte-derived macrophages and peripheral blood lymphocytes with the CXCR3 ligand IP-10 before HIV-1 infection promoted viral replication, while blocking CXCR3 on cells reduced the replication in vitro (47). A recent study also reported that IP-10 promoted latent HIV-1 infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells via the LIM domain kinase (LIMK)-Cofilin pathway to facilitate viral entry and viral DNA integration (21). Increased plasma TGF-β during acute infection may therefore promote HIV-1 infection and subsequent latency reservoir establishment in resting memory CD4+ T cells via the induction of CXCR3 expression. Several studies have already reported that CXCR3+ memory CD4+ T cells from blood and lymph node of cART-treated patients harbor replication-competent latent HIV-1 (29, 48). Moreover, plasma IP-10 level was also positively correlated with HIV-1 viral load and the size of latency reservoirs (21). In line with these findings, our study also reported that cART-naive and cART-treated patients had higher frequencies of CXCR3-expressing cells in total resting and resting memory CD4+ T cells (Fig. 8). Others have also reported that total memory CD4+ T cells in the circulation, terminal ileum, and rectum of cART-treated patients expressed a higher level of CXCR3 than those of healthy controls (49). Together with our findings, these studies suggested that CXCR3 could potentiate HIV-1 infection and subsequent latency establishment during the early acute infection phase via TGF-β upregulation. However, whether CXCR3 can facilitate the infection of activated memory or other CD4+ T cell subtypes remains unclear. Therefore, whether HIV-1 infection and latency establishment can be promoted via the TGF-β–CXCR3 axis in other CD4+ T cell subtypes is yet to be addressed.

The current study showed that TGF-β could promote the expression of CCR5, CCR7, and CXCR3. How the induction of these targets contributes to HIV-1 infection and the latency establishment discussed above opens a new avenue in identifying possible therapeutic targets. Our findings together with those of others suggest that TGF-β blockade may serve as a potential supplementary treatment of cART. The advantage of using TGF-β blockade as a potential treatment regimen is the availability of existing drugs that are currently under clinical trials. TGF-β blockade has long been evaluated as a potential treatment regimen for various diseases, and drugs that are currently under development have been extensively reviewed by others (50, 51). Some of these new agents have already undergone phase I and II clinical trials, with minimal side effects. For example, the monoclonal antibody fresolimumab (also known as GC1008) can bind to all three TGF-β isoforms, and the phase I clinical trial confirmed its safety, with no dose-limiting toxicity at a dose of up to 15 mg/kg of body weight and a half-life of 21.7 days (52). Owing to the short half-life often reported for therapeutic engineered antibodies, the application of fresolimumab in chronic cART-treated patients remains uncertain. However, TGF-β blockade during early acute infection may serve as a promising supplementary therapy in addition to cART, in particular, to reduce HIV-1 infection on activated memory CD4+ T cells and the subsequent establishment and expansion of latency reservoirs during acute infection as previously discussed (3). Overall, the current study delineated that TGF-β can potentiate CCR5-tropic infection of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells via upregulating the expression of HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5, as well as the chemokine receptors CCR7 and CXCR3, which may promote infection of these cells via trafficking into lymphoid organs and increase HIV-1 infection of resting CD4+ T cells. These results highlight TGF-β blockade as a new strategy to delay HIV-1 infection in resting memory CD4+ T cells, thereby allowing a possibly increased time window for therapeutic cure using postexposure cART.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient sample collection.

Acute and chronic patients were recruited from the Beijing PRIMO cohort of men who have sex with men (MSM) at a high risk of HIV-1 infection, with written consent and ethical approval from the Beijing Youan Hospital Research Ethics Committee. Participants were screened every 2 months for acute HIV-1 infection at Beijing Youan Hospital. Acute infection was defined as a positive result for the detection of HIV-1 RNA but a negative or indeterminate level of anti-HIV-1 antibodies. Once acute infection was detected, patients were followed at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 and every 3 months thereafter. The CD4+ T cell counts, viral loads, and syphilis status were also determined. Chronic infection was considered to begin 6 months after the diagnosis of acute infection and had been treated for various periods at the time of blood sampling. Samples from cART-naive and cART-treated patients were collected from Hong Kong. The study was reviewed and approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong-New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee. The cART-naive patient blood samples were collected on the patients’ first visit to the clinic, while cART-treated patients were in different treatment periods.

Evaluation of patient plasma TGF-β.

The whole blood of patients was centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min to isolate plasma. Plasma samples were then pretreated and activated with 1 N hydrochloric acid to release the active form of TGF-β. Samples were heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min before conducting ELISA using the human TGF-β1 DuoSet ELISA system (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, a 96-well ELISA plate (Costar) was coated at room temperature with a capture antibody diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight. The plate was then thoroughly washed with wash buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS and blocked with block buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for at least 1 h. Diluted samples were then added to the plate with a 2-h incubation, followed by thorough washing and addition of the detection antibody. The plate was further incubated for 2 h, with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) added after washing. After 20 min of incubation, the signal was visualized by the addition of substrate prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To terminate the reaction, 2 N sulfuric acid was added, and the plate was read at 450 nm for signal detection with 540 nm as the correction wavelength.

Preparation of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells.

Healthy donor buffy coats were obtained from the Red Cross, Hong Kong SAR, China. This was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster. PBMCs were isolated by overlaying a diluted buffy coat on Lymphoprep (Stemcell Technologies) at a 2:1 (vol/vol) ratio, followed by centrifugation at 650 × g for 30 min with no brake. CD4+ T cells were purified from PBMCs by negative selection using RosetteSep human CD4+ T cell enrichment cocktail (Stemcell Technologies). For the preparation of activated memory CD4+ T cells, CD45RO+ memory cells were purified from total CD4+ T cells by positive selection using anti-human CD45RO microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Cells were then stimulated with recombinant human IL-2 (10 ng/mL) and IL-15 (20 ng/mL) (PeproTech) for 4 days in 200 μL of serum-free AIM V medium (Gioco) using a 96-well V-bottom culture plate (Corning). The activation status of activated memory CD4+ T cells was evaluated by the induction of CD25, CD69, and HLA-DR, as well as by the increase in cell size and cellular granularity using flow cytometry analysis. Resting memory CD4+ T cells were purified by negative selection, in which CD25+ CD69+ HLA-DR+ CD4+ T cells were depleted from total CD4+ T cells using anti-human CD25 and HLA-DR microbeads and anti-human CD69 biotinylated antibody plus anti-biotin microbeads (all from Miltenyi Biotech). The purity of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells was at least 90% as evaluated by flow cytometry.

In vitro TGF-β treatment of activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells.

Around 3 × 105 purified memory CD4+ T cells were activated in 200 μL of AIM V medium containing recombinant IL-2 and IL-15 as described above. Cells were treated with 1 or 10 ng/mL of human recombinant TGF-β1 (PeproTech) for 3 days in the presence of human recombinant IL-2 and IL-15. The TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542 (Sigma-Aldrich) and Smad3 phosphorylation inhibitor SIS3 (Sigma-Aldrich) were also added into the system at 1 μM and 10 μM as indicated, in order to delineate the roles of TGF-β and Smad3 during HIV-1 infection. For resting memory CD4+ T cells, 4 × 105 cells were cultured in 200 μL of AIM V medium and treated with TGF-β1 in the presence or absence of SB431542 or SIS3 for 4 days. For both activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells, cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis or HIV-1 infection by pseudovirus or live HIV-1 after TGF-β1 treatment.

Evaluation of CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection and viral production in vitro.

After TGF-β1 treatment in the presence or absence of TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor SB431542 and Smad3 phosphorylation inhibitor SIS3, activated or resting memory CD4+ T cells were subjected to live HIV-1 infection using the CCR5-tropic tier 2 virus HIV-1JR-FL. The concentration of HIV-1JR-FL stock was quantified by p24 ELISA (Sino Biological), and cells were infected by HIV-1JR-FL with 2 ng of p24 per 1 × 105 cells in AIM V medium. Spinoculation was done at 1,200 × g for 90 min at 4°C. Cells were then cultured in the incubator at 37°C, with the virus removed by washing with PBS on the next day. For activated memory CD4+ T cells, cells were cultured in 10 ng/mL of IL-2 after infection, and T cell-associated p24 was evaluated 3 days after infection using flow cytometry analysis. For resting memory CD4+ T cells, cells were reactivated on the next day after infection with 10 μg/mL of anti-human CD3 (clone OKT3) and 5 μg/mL of CD28 (clone CD28.2) antibodies (BioLegend), in the presence of 10 ng/mL of IL-2 and 20 ng/mL of IL-15. T cell-associated p24 was then evaluated 3 days after infection using flow cytometry. The pseudovirus system (referred to here as NanoLucJR-FL) was also used to evaluate CCR5-tropic infection of resting memory CD4+ T cells. It consists of a tier 2 envelope JR-FL and the HIV-1 NL4-3 ΔEnv Vpr luciferase reporter vector (pNL4-3.Luc.R-E-) containing a defective nef, env, and vpr, as well as a nanoluciferase reporter in its pNL4-3.Luc.R-E- backbone (catalog number ARP-3418; NIH AIDS Reagent Program). The culture supernatant was collected 7 days after infection, and the Nano-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega) was used to evaluate nanoluciferase activity. The production of HIV-1JR-FL by resting memory CD4+ T cells after infection and reactivation was determined by p24 ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sino Biological).

Flow cytometry analysis.

For detection of surface molecules on activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells, cells were stained with the respective antibodies in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (2% fetal calf serum in PBS) for 15 min, followed by a thorough washing with FACS buffer. For detection of p24, cells were first stained with surface markers, followed by fixation by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min and cell permeabilization by saponin using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD). Cells were stained for intracellular p24 in 1× Perm/Wash buffer (BD) at 4°C for 1 h. After being washed with 1× Perm/Wash buffer, cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis. The following antibodies (all from BD and BioLegend) were used for staining surface markers: CD3 Pacific blue (clone SK7), CD4 Pacific blue (clone OKT4) and BV510 (clone A161A1), CD45RO fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (clone UCHL1), CCR5 FITC and phycoerythrin (PE)/Cy7 (clone 2D7), CCR7 PE and allophycocyanin (APC) (clone G043H7), CXCR3 BV421 (clone G025H7), CD25 peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCp)/Cy5.5 (clone BC96), HLA-DR PE (clone L243), and CD69 APC (clone FN50). For the intracellular staining of p24, p24 FITC antibody (clone KC57) was used (Beckman Coulter). The Zombie aqua fixable viability dye (BioLegend) was used to distinguish dead cells. The FACS Aria III (BD) was used for flow cytometry analysis, and FlowJo software (TreeStar, BD) was used for data analysis.

Mass cytometry (CyTOF) analysis.

Total resting CD4+ T cells were stained for surface molecules according to the manufacturer’s instructions (FLUIDIGM). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and stained with Cell-ID cisplatin to distinguish viable cells. Surface staining was then performed in Maxpar cell staining buffer for 30 min at room temperature, and cells were washed thoroughly with Maxpar cell staining buffer. The following antibodies were used: CD45RA-169Tm (clone HI100), CXCR3-156Gd (clone G025H7), CXCR6-160Gd (clone K041E5), CCR5-144Nd (clone NP-6G4), CCR6-141Pr (clone G034E3), CCR9-168Er (clone L053E8), CD27-158Gd (clone L128), CD38-167Er (clone HIT2), CD95-164Dy (clone DX2), CD161-159Tb (clone HP-3G10), PD-1-155Gd (clone EH12.2H7), and HLA-DR-173Yb (clone L243). The data acquisition was done with a Helios mass cytometer (FLUIDIGM).

Statistical analysis.

The two-tailed unpaired Student t test was used to determine statistical significance of the data using GraphPad Prism. A P value smaller than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Each experiment was repeated at least 3 times unless otherwise stated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the NIH HIV Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, for providing the following reagents: human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) JR-FL, ARP-395, contributed by Irvin Chen, and HIV-1 NL4-3 ΔEnv Vpr luciferase reporter vector (pNL4-3.Luc.R-E-), ARP-3418, contributed by Nathaniel Landau. We also thank Chee Hoo Yip for proofreading the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund (19180642) from Hong Kong Food and Health Bureau, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administration Region of the People’s Republic of China, the Theme-based Research Scheme (T11-706/18-N) and General Research Fund (17121420) from the Hong Kong Research Grant Council (RGC), as well as The University Development Fund and Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine Matching Fund from the University of Hong Kong to AIDS Institute.

We have read the journal’s policy, and all authors do not have any competing interests or additional financial interests.

Z.C. coordinated the collaborative teams and conceived the study. L.Y.Y. developed the serum-free culture system. L.Y.Y., K.S.L., and T.-Y.L. did most experiments and data analysis; X.L., H.W., and T.Z. provided patient care and sampling in Beijing Youan Hospital; G.C.Y.L., D.P.C.C., B.C.K.W., and S.S.L. provided patient care and sampling in Hong Kong; Y.M., J.W., K.-W.C., T.T.-K.L., C.B.N., D.Z., Y.C.W., Z.T., and L.L. did some experiments or provided technical support. L.Y.Y. and K.S.L. wrote the manuscript; L.Y.Y., Y.M., and Z.C. revised the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Zhiwei Chen, Email: zchenai@hku.hk.

Frank Kirchhoff, Ulm University Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katlama C, Deeks SG, Autran B, Martinez-Picado J, van Lunzen J, Rouzioux C, Miller M, Vella S, Schmitz JE, Ahlers J, Richman DD, Sekaly RP. 2013. Barriers to a cure for HIV: new ways to target and eradicate HIV-1 reservoirs. Lancet 381:2109–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60104-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohn LB, Chomont N, Deeks SG. 2020. The biology of the HIV-1 latent reservoir and implications for cure strategies. Cell Host Microbe 27:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee E, Bacchetti P, Milush J, Shao W, Boritz E, Douek D, Fromentin R, Liegler T, Hoh R, Deeks SG, Hecht FM, Chomont N, Palmer S. 2019. Memory CD4 + T-cells expressing HLA-DR contribute to HIV persistence during prolonged antiretroviral therapy. Front Microbiol 10:2214. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran TA, de Goer de Herve MG, Hendel-Chavez H, Dembele B, Le Nevot E, Abbed K, Pallier C, Goujard C, Gasnault J, Delfraissy JF, Balazuc AM, Taoufik Y. 2008. Resting regulatory CD4 T cells: a site of HIV persistence in patients on long-term effective antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One 3:e3305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leite TF, Delatorre E, Cortes FH, Ferreira ACG, Cardoso SW, Grinsztejn B, de Andrade MM, Veloso VG, Morgado MG, Guimaraes ML. 2019. Reduction of HIV-1 reservoir size and diversity after 1 year of cART among Brazilian individuals starting treatment during early stages of acute infection. Front Microbiol 10:145. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo L, Wang N, Yue Y, Han Y, Lv W, Liu Z, Qiu Z, Lu H, Tang X, Zhang T, Zhao M, He Y, Shenghua H, Wang M, Li Y, Huang S, Li Y, Liu J, Tuofu Z, Routy JP, Li T. 2019. The effects of antiretroviral therapy initiation time on HIV reservoir size in Chinese chronically HIV infected patients: a prospective, multi-site cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 19:257. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3847-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barqasho B, Nowak P, Tjernlund A, Kinloch S, Goh LE, Lampe F, Fisher M, Andersson J, Sonnerborg A, QUEST study group . 2009. Kinetics of plasma cytokines and chemokines during primary HIV-1 infection and after analytical treatment interruption. HIV Med 10:94–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickinson M, Kliszczak AE, Giannoulatou E, Peppa D, Pellegrino P, Williams I, Drakesmith H, Borrow P. 2020. Dynamics of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta superfamily cytokine induction during HIV-1 infection are distinct from other innate cytokines. Front Immunol 11:596841. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.596841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorelik L, Constant S, Flavell RA. 2002. Mechanism of transforming growth factor beta-induced inhibition of T helper type 1 differentiation. J Exp Med 195:1499–1505. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis GM, Wehrens EJ, Labarta-Bajo L, Streeck H, Zuniga EI. 2016. TGF-beta receptor maintains CD4 T helper cell identity during chronic viral infections. J Clin Invest 126:3799–3813. doi: 10.1172/JCI87041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kekow J, Wachsman W, McCutchan JA, Cronin M, Carson DA, Lotz M. 1990. Transforming growth factor beta and noncytopathic mechanisms of immunodeficiency in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:8321–8325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maina EK, Abana CZ, Bukusi EA, Sedegah M, Lartey M, Ampofo WK. 2016. Plasma concentrations of transforming growth factor beta 1 in non-progressive HIV-1 infection correlates with markers of disease progression. Cytokine 81:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsson J, Boasso A, Velilla PA, Zhang R, Vaccari M, Franchini G, Shearer GM, Andersson J, Chougnet C. 2006. HIV-1-driven regulatory T-cell accumulation in lymphoid tissues is associated with disease progression in HIV/AIDS. Blood 108:3808–3817. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson J, Boasso A, Nilsson J, Zhang R, Shire NJ, Lindback S, Shearer GM, Chougnet CA. 2005. The prevalence of regulatory T cells in lymphoid tissue is correlated with viral load in HIV-infected patients. J Immunol 174:3143–3147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epple HJ, Loddenkemper C, Kunkel D, Troger H, Maul J, Moos V, Berg E, Ullrich R, Schulzke JD, Stein H, Duchmann R, Zeitz M, Schneider T. 2006. Mucosal but not peripheral FOXP3+ regulatory T cells are highly increased in untreated HIV infection and normalize after suppressive HAART. Blood 108:3072–3078. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, Trautmann L, Procopio FA, Yassine-Diab B, Boucher G, Boulassel MR, Ghattas G, Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Hill BJ, Douek DC, Routy JP, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP. 2009. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med 15:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nm.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douek DC, Brenchley JM, Betts MR, Ambrozak DR, Hill BJ, Okamoto Y, Casazza JP, Kuruppu J, Kunstman K, Wolinsky S, Grossman Z, Dybul M, Oxenius A, Price DA, Connors M, Koup RA. 2002. HIV preferentially infects HIV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nature 417:95–98. doi: 10.1038/417095a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siliciano JD, Kajdas J, Finzi D, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick JB, Kovacs C, Gange SJ, Siliciano RF. 2003. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat Med 9:727–728. doi: 10.1038/nm880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shan L, Deng K, Gao H, Xing S, Capoferri AA, Durand CM, Rabi SA, Laird GM, Kim M, Hosmane NN, Yang HC, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Li L, Cai W, Ke R, Flavell RA, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. 2017. Transcriptional reprogramming during effector-to-memory transition renders CD4(+) T cells permissive for latent HIV-1 infection. Immunity 47:766–775.e763. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung KW, Wu T, Ho SF, Wong YC, Liu L, Wang H, Chen Z. 2018. α4β7(+) CD4(+) effector/effector memory T cells differentiate into productively and latently infected central memory T Cells by transforming growth factor β1 during HIV-1 infection. J Virol 92:e01510-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01510-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Yin X, Ma M, Ge H, Lang B, Sun H, He S, Fu Y, Sun Y, Yu X, Zhang Z, Cui H, Han X, Xu J, Ding H, Chu Z, Shang H, Wu Y, Jiang Y. 2021. IP-10 promotes latent HIV infection in resting memory CD4(+) T cells via LIMK-cofilin pathway. Front Immunol 12:656663. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.656663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi D, Endo M, Ochi H, Hojo H, Miyasaka M, Hayasaka H. 2017. Regulation of CCR7-dependent cell migration through CCR7 homodimer formation. Sci Rep 7:8536. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bromley SK, Thomas SY, Luster AD. 2005. Chemokine receptor CCR7 guides T cell exit from peripheral tissues and entry into afferent lymphatics. Nat Immunol 6:895–901. doi: 10.1038/ni1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanjabi S, Oh SA, Li MO. 2017. Regulation of the immune response by TGF-beta: from conception to autoimmunity and infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halder SK, Beauchamp RD, Datta PK. 2005. A specific inhibitor of TGF-beta receptor kinase, SB-431542, as a potent antitumor agent for human cancers. Neoplasia 7:509–521. doi: 10.1593/neo.04640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu AD, Wang Y, Lin L, Zhang SS, Wan YY. 2012. Requirements of transcription factor Smad-dependent and -independent TGF-beta signaling to control discrete T-cell functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:905–910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108352109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green DS, Center DM, Cruikshank WW. 2009. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 reprogramming of CD4+ T-cell migration provides a mechanism for lymphadenopathy. J Virol 83:5765–5772. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00130-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayasaka H, Kobayashi D, Yoshimura H, Nakayama EE, Shioda T, Miyasaka M. 2015. The HIV-1 Gp120/CXCR4 axis promotes CCR7 ligand-dependent CD4 T cell migration: CCR7 homo- and CCR7/CXCR4 hetero-oligomer formation as a possible mechanism for up-regulation of functional CCR7. PLoS One 10:e0117454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khoury G, Anderson JL, Fromentin R, Hartogenesis W, Smith MZ, Bacchetti P, Hecht FM, Chomont N, Cameron PU, Deeks SG, Lewin SR. 2016. Persistence of integrated HIV DNA in CXCR3 + CCR6 + memory CD4+ T cells in HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 30:1511–1520. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cosmi L, De Palma R, Santarlasci V, Maggi L, Capone M, Frosali F, Rodolico G, Querci V, Abbate G, Angeli R, Berrino L, Fambrini M, Caproni M, Tonelli F, Lazzeri E, Parronchi P, Liotta F, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Annunziato F. 2008. Human interleukin 17-producing cells originate from a CD161+CD4+ T cell precursor. J Exp Med 205:1903–1916. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Liu Z, Li Q, Hu R, Zhao L, Yang Y, Zhao J, Huang Z, Gao H, Li L, Cai W, Deng K. 2019. CD161(+) CD4(+) T cells harbor clonally expanded replication-competent HIV-1 in antiretroviral therapy-suppressed individuals. mBio 10:e02121-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02121-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karolczak K, Watala C. 2021. Blood platelets as an important but underrated circulating source of TGFβ. Int J Mol Sci 22:4492. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiercińska-Drapalo A, Flisiak R, Jaroszewicz J, Prokopowicz D. 2004. Increased plasma transforming growth factor-beta1 is associated with disease progression in HIV-1-infected patients. Viral Immunol 17:109–113. doi: 10.1089/088282404322875502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinhold D, Wrenger S, Kahne T, Ansorge S. 1999. HIV-1 Tat: immunosuppression via TGF-beta1 induction. Immunol Today 20:384–385. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01497-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zauli G, Davis BR, Re MC, Visani G, Furlini G, La Placa M. 1992. tat protein stimulates production of transforming growth factor-beta 1 by marrow macrophages: a potential mechanism for human immunodeficiency virus-1-induced hematopoietic suppression. Blood 80:3036–3043. doi: 10.1182/blood.V80.12.3036.3036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu R, Oyaizu N, Than S, Kalyanaraman VS, Wang XP, Pahwa S. 1996. HIV-1 gp160 induces transforming growth factor-beta production in human PBMC. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 80:283–289. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leyre L, Kroon E, Vandergeeten C, Sacdalan C, Colby DJ, Buranapraditkun S, Schuetz A, Chomchey N, de Souza M, Bakeman W, Fromentin R, Pinyakorn S, Akapirat S, Trichavaroj R, Chottanapund S, Manasnayakorn S, Rerknimitr R, Wattanaboonyoungcharoen P, Kim JH, Tovanabutra S, Schacker TW, O’Connell R, Valcour VG, Phanuphak P, Robb ML, Michael N, Trautmann L, Phanuphak N, Ananworanich J, Chomont N, RV254/SEARCH010, RV304/SEARCH013, SEARCH011 study groups . 2020. Abundant HIV-infected cells in blood and tissues are rapidly cleared upon ART initiation during acute HIV infection. Sci Transl Med 12:eaav3491. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley JL, Levine BL, Craighead N, Francomano T, Kim D, Carroll RG, June CH. 1998. Naive and memory CD4 T cells differ in their susceptibilities to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection following CD28 costimulation: implications for transmission and pathogenesis. J Virol 72:8273–8280. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.10.8273-8280.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson SA, Ingman WV, O’Leary S, Sharkey DJ, Tremellen KP. 2002. Transforming growth factor beta—a mediator of immune deviation in seminal plasma. J Reprod Immunol 57:109–128. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(02)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loras B, Vetele F, El Malki A, Rollet J, Soufir JC, Benahmed M. 1999. Seminal transforming growth factor-beta in normal and infertile men. Hum Reprod 14:1534–1539. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.6.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agosto LM, Herring MB, Mothes W, Henderson AJ. 2018. HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells facilitate latent infection of resting CD4+ T cells through cell-cell contact. Cell Rep 24:2088–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saleh S, Solomon A, Wightman F, Xhilaga M, Cameron PU, Lewin SR. 2007. CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21 increase permissiveness of resting memory CD4+ T cells to HIV-1 infection: a novel model of HIV-1 latency. Blood 110:4161–4164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saleh S, Lu HK, Evans V, Harisson D, Zhou J, Jaworowski A, Sallmann G, Cheong KY, Mota TM, Tennakoon S, Angelovich TA, Anderson J, Harman A, Cunningham A, Gray L, Churchill M, Mak J, Drummer H, Vatakis DN, Lewin SR, Cameron PU. 2016. HIV integration and the establishment of latency in CCL19-treated resting CD4(+) T cells require activation of NF-kappaB. Retrovirology 13:49. doi: 10.1186/s12977-016-0284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan IA, MacLean JA, Lee FS, Casciotti L, DeHaan E, Schwartzman JD, Luster AD. 2000. IP-10 is critical for effector T cell trafficking and host survival in Toxoplasma gondii infection. Immunity 12:483–494. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qin S, Rottman JB, Myers P, Kassam N, Weinblatt M, Loetscher M, Koch AE, Moser B, Mackay CR. 1998. The chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR5 mark subsets of T cells associated with certain inflammatory reactions. J Clin Invest 101:746–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim CH, Rott L, Kunkel EJ, Genovese MC, Andrew DP, Wu L, Butcher EC. 2001. Rules of chemokine receptor association with T cell polarization in vivo. J Clin Invest 108:1331–1339. doi: 10.1172/JCI13543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lane BR, King SR, Bock PJ, Strieter RM, Coffey MJ, Markovitz DM. 2003. The C-X-C chemokine IP-10 stimulates HIV-1 replication. Virology 307:122–134. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banga R, Procopio FA, Ruggiero A, Noto A, Ohmiti K, Cavassini M, Corpataux JM, Paxton WA, Pollakis G, Perreau M. 2018. Blood CXCR3(+) CD4 T cells are enriched in inducible replication competent HIV in aviremic antiretroviral therapy-treated individuals. Front Immunol 9:144. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Augustin M, Horn C, Ercanoglu MS, Sandaradura de Silva U, Bondet V, Suarez I, Chon SH, Nierhoff D, Knops E, Heger E, Vivaldi C, Schafer H, Oette M, Fatkenheuer G, Klein F, Duffy D, Muller-Trutwin M, Lehmann C. 2022. CXCR3 expression pattern on CD4+ T cells and IP-10 levels with regard to the HIV-1 reservoir in the gut-associated lymphatic tissue. Pathogens 11:483. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11040483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang CY, Chung CL, Hu TH, Chen JJ, Liu PF, Chen CL. 2021. Recent progress in TGF-beta inhibitors for cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother 134:111046. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim BG, Malek E, Choi SH, Ignatz-Hoover JJ, Driscoll JJ. 2021. Novel therapies emerging in oncology to target the TGF-beta pathway. J Hematol Oncol 14:55. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01053-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morris JC, Tan AR, Olencki TE, Shapiro GI, Dezube BJ, Reiss M, Hsu FJ, Berzofsky JA, Lawrence DP. 2014. Phase I study of GC1008 (fresolimumab): a human anti-transforming growth factor-beta (TGFbeta) monoclonal antibody in patients with advanced malignant melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One 9:e90353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S3. Download jvi.00270-23-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.1 MB (1.1MB, pdf)