Abstract

Objective:

This retrospective cohort study aimed to assess incidence and predictors of acne among transgender adolescents receiving testosterone.

Materials and methods:

We analyzed records of patients aged <18 years, assigned female at birth seen at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Pediatric Endocrinology clinic for testosterone initiation between 1/1/2016–1/1/2019, with at least 1-year follow-up documented. Bivariable analyses to determine association of clinical and demographic factors with new acne diagnosis were calculated.

Results:

Of 60 patients, 46 (77%) did not have baseline acne. 25 of those 46 patients developed acne (54%) within 1-year of testosterone initiation. Overall incidence proportion was 70% at 2-years; patients who used progestin prior to or during follow up were more likely to develop acne than non-users (92% vs 33%, p<0.001).

Conclusion:

Transgender adolescents starting testosterone, particularly those taking progestin, should be monitored for acne development, and treated proactively by hormone providers and dermatologists.

Keywords: epidemiology, acne, testosterone, transgender, pediatric dermatology, masculinizing hormone therapy

Introduction

Acne affects 70–87% of adolescents in the general population and causes significant psychosocial distress.(1) Acne is a common side effect of testosterone therapy among transmasculine adults.(2–4) Limited data exists on acne epidemiology among transgender adolescents on testosterone. This retrospective cohort study aimed to assess prevalence, incidence, and predictors of acne among transgender adolescents initiating testosterone.

Material and methods

We analyzed electronic medical records of transmasculine patients seen at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Pediatric Endocrinology clinic for gender-affirming testosterone therapy initiation between 1/1/2016–1/1/2019. This study was approved by the Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta institutional review boards. The study was deemed minimal risk to participants and obtaining informed consent prior to review of existing records was not required. Eligible patients were aged <18 years at testosterone initiation, assigned female at birth, and had at least 1-year follow-up. Baseline acne was ascertained from history or physical examination recorded before testosterone initiation. For patients with baseline acne, documentation of clinical change in acne severity in clinical history or physical examination was noted. Post-testosterone acne was acne noted after testosterone initiation. Period prevalence of any acne (baseline and/or post-testosterone) and incidence proportions of post-testosterone acne among those without baseline acne at 6, 12, 18 and 24-months of follow up were calculated. Patients with and without incident acne at 24-months of follow up were compared by age, BMI, form of testosterone delivery, testosterone dose, anxiety or depression, progestin use, age at menarche, and serum total testosterone at 3-months post-testosterone initiation, using Fisher’s exact, Student’s t, or Mann-Whitney U tests as appropriate, with two-sided p<0.05 considered significant. Analyses were performed on SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp).

Results

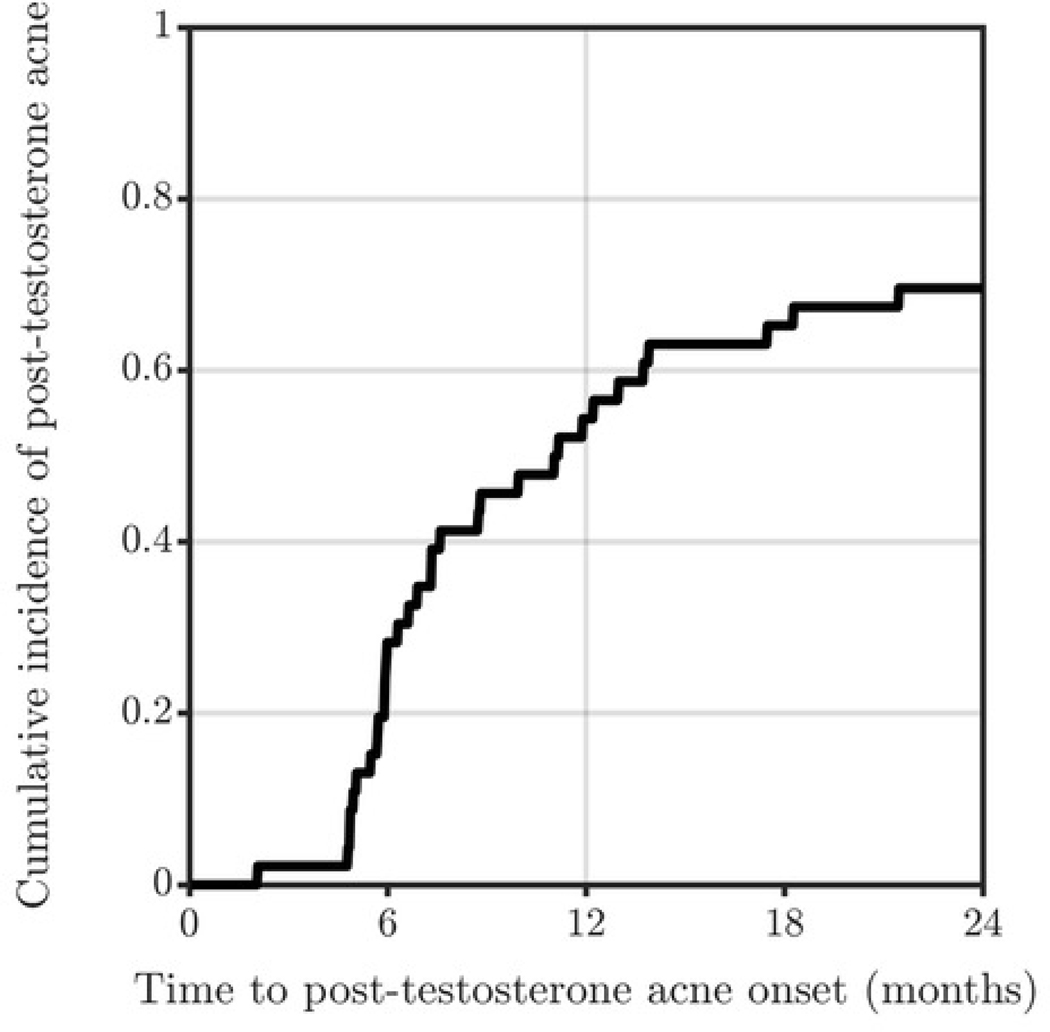

Among 60 eligible patients, the majority were aged 16–17 (45%), non-Hispanic/Latinx White (85%), identified as male (100%), and used intramuscular/subcutaneous testosterone cypionate or enanthate (93%) (Table 1). At baseline, 14 (23%) patients had acne. Among 46 who had no baseline acne, 25 (54%) developed incident acne during the 2-year follow up. Incidence proportion after 6 months of testosterone was 28%, 36% at 7–12 months, 24% at 13–18 months, and 13% at 19–24 months. Overall incidence proportion was 54% at 1-year and 70% at 2-years (Figure 1). All patients with baseline acne had worsening acne after testosterone initiation. No patients with baseline or incident acne were prescribed acne therapies by hormone providers. Five of 14 (36%) patients with baseline acne and 12 of 25 (48%) with incident acne were referred to dermatology. Age, BMI, testosterone dose and mode of delivery, history of anxiety or depression, age at menarche, and serum total testosterone at 3-months post-testosterone initiation were not associated with higher incidence proportion of acne at 2-years. Patients who used progestin prior to or during follow up were more likely to develop acne than non-users (92% vs 33%, p<0.001). Progestin type was not associated with increased incidence of acne.

Table 1.

Baseline and Clinical Characteristics at Testosterone Initiation (n=60)

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 15.5 (15, 16) |

| Age, range | 12–19 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 23.1 (19.6, 29.2) |

| Age at menarche, median (IQR) ( n=35) | 12 (1.25) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White, Hispanic/Latinx | 3 (5) |

| White, non-Hispanic/Latinx | 51 (85) |

| Black, Hispanic/Latinx | 1 (1.7) |

| Black, non-Hispanic/Latinx | 2 (3.3) |

| Undefined or multiracial, Hispanic/Latinx | 1 (1.7) |

| Undefined or multiracial, non-Hispanic/Latinx | 1 (1.7) |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 1 (1.7) |

| Gender Identity, n (%) | |

| Male | 60 (100) |

| Sexual orientation, n (%) | |

| Straight/heterosexual | 14 (23.3) |

| Gay/lesbian/homosexual | 11 (18.3) |

| Bisexual | 6 (10) |

| Other | 3 (5) |

| Not reported | 26 (43.4) |

| Comorbidities at baseline, n (%) | |

| Depression | 26 (43.3) |

| Anxiety | 18 (30) |

| Testosterone type, n (%) | |

| Intramuscular/subcutaneous injection | 56 (93.3) |

| Transdermal | 4 (6.7) |

| Overall dose at maintenance, mg/wk/kg, median (IQR) | 0.91 (0.71, 1.1) |

| Intramuscular/subcutaneous injection | 0.90 (0.71, 1.1) |

| Transdermal | 3.7 (1.1, 6.7) |

| Total serum testosterone 3-months post-testosterone initiation, ng/dL, median (IQR) (n=11) | 159 (105.5, 278) |

| Total serum testosterone 1-year post-testosterone initiation, ng/dL, median (IQR) (n=55) | 193 (138, 299) |

| Use of following medications before and within 1 y post-testosterone therapy, No. (%) | |

| Progestin | 39 (65) |

| Combined oral contraceptives | 1 (1.7) |

| None | 19 (31.7) |

| Progestin type, n (%) | |

| Norethindrone acetate | 29 (48) |

| Norethindrone | 6 (10) |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 6 (10) |

| None | 21 (35) |

| Patients referred to dermatologist, n (%) | |

| Yes | 17 (28.3) |

| No | 43 (71.7) |

| Insurance, n (%) | |

| Private | 48 (80) |

| Public | 7 (11.7) |

| None | 5 (8.3) |

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of acne diagnosis among transgender adolescents without baseline acne (n=46) at 1- and 2-years.

Discussion

Acne is common among transgender adolescents on testosterone. Dihydrotestosterone, a metabolite of testosterone, binds to androgen receptors and stimulates sebaceous glands to increase production of sebum and proinflammatory cytokines to cause acne.(5) Progestins are often prescribed to cease uterine bleeding, but progestins with higher androgenic potentials can bind androgen receptors and exacerbate acne.(6–8) In contrast with results from a prior transgender adult cohort study, progestin use was associated with increased acne incidence in our cohort of transgender adolescents.(2) Progestins received by a majority of our patients, such as norethindrone and medroxyprogesterone, have been previously shown to exacerbate acne development.(9) Newer generations of progestins may have lower androgenic potential.(10)

Despite high incidence of acne, hormone providers in our cohort study did not provide acne care. No patients were prescribed acne therapies by hormone providers, and a minority were referred to dermatology, highlighting a practice gap in acne care among transgender adolescents. Hormone providers may underestimate the impact of acne on mental comorbidities and body image satisfaction. Transgender youths have higher rates of depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts compared to cisgender youths.(4) Appearance of acne may worsen underlying depression and anxiety symptoms and should be treated proactively in transgender persons.(11) Study limitations include retrospective single tertiary center data, lack of data on family history of acne, and lack of validated acne severity outcome measures, particularly in patients with incident acne. Accuracy of baseline or incident acne was limited by endocrine provider documentation. Lack of documentation of over-the-counter acne treatments may also contribute to information bias.

Conclusion

Transgender adolescents initiating testosterone, particularly those taking progestin, should be monitored closely for acne development. While there are no established acne treatment guidelines for transgender adolescents using hormone therapy, recommendations from acne treatment guidelines in cisgender populations are mostly applicable.(12) Mild acne can be managed with topical antibiotics (i.e., clindamycin), topical retinoids (i.e., adapalene, tretinoin), and/or topical antiandrogens (i.e., clastocerone).(13) For moderate to severe acne, oral antibiotics and hormonal therapies (i.e., spironolactone, oral contraceptives) are effective options.(13) Gender-affirming hormone providers should incorporate empirical, guideline-driven acne care as part of comprehensive hormone treatment with dermatology referral for further management.

Highlights

Acne is a common side effect of testosterone therapy in transgender adolescents.

Overall incidence proportion was 70% at 2 years of testosterone initiation.

Of 46 patients without baseline acne, 25 developed incident acne by 1 year.

Progestin-users were more likely to develop acne than non-users.

No patients with baseline or incident acne were prescribed acne therapies.

Clinical Relevance

Transgender adolescents on testosterone commonly develop acne, and rarely get referred to dermatology for treatment. Since acne can have a major impact on mental health, hormone providers should incorporate acne treatment into plans for comprehensive gender-affirming care, particularly for patients on testosterone and progestins.

Funding:

This work is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases [grant numbers L30AR076081, K23AR075888]; and the National Institute on Aging and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [grant numbers R01AG066956 and R21HD076387].

Footnotes

IRB approval status: Reviewed and approved by the Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Institutional Review Boards (IRB0003521).

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Tangpricha is the Editor-in-Chief of Endocrine Practice.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eichenfield LF, Krakowski AC, Piggott C, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric acne. Pediatrics. 2013;131 Suppl 3:S163–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thoreson N, Park JA, Grasso C, et al. Incidence and Factors Associated With Acne Among Transgender Patients Receiving Masculinizing Hormone Therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:290–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao JL, King DS, Modest AM, Dommasch ED. Acne risk in transgender and gender diverse populations: A retrospective, comparative cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, Saewyc EM. Mental Health Disparities Among Canadian Transgender Youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee WJ, Jung HD, Chi SG, et al. Effect of dihydrotestosterone on the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines in cultured sebocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnington A, Dianat S, Kerns J, et al. Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: Contraceptive counseling for transgender and gender diverse people who were female sex assigned at birth. Contraception. 2020;102:70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022;23:S1–S259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz BI, Bear B, Kazak AE. Menstrual Management Choices in Transgender and Gender Diverse Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lortscher D, Admani S, Satur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal Contraceptives and Acne: A Retrospective Analysis of 2147 Patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:670–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louw-du Toit R, Perkins MS, Hapgood JP, Africander D. Comparing the androgenic and estrogenic properties of progestins used in contraception and hormone therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;491:140–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun H, Zhang Q, Getahun D, et al. Moderate-to-Severe Acne and Mental Health Symptoms in Transmasculine Persons Who Have Received Testosterone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:344–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ragmanauskaite L, Kahn B, Ly B, Yeung H. Acne and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, or Transgender Teenager. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945–973.e933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]