Abstract

Assigning stress to the appropriate syllable is consequential for being understood. Despite the importance, second language (L2) learners’ stress assignment is often incorrect, being affected by their first language (L1). Beyond the L1, learners’ lexical stress assignment may depend on analogy with other words in their lexicon. The current study investigates the respective roles of the L1 (English, French) and analogy in L2 German lexical stress assignment. Because English, like German, has variable stress assignment and French does not, participants included English- and French-speaking German L2 learners who assigned stress to German nonsense words in a perceptual preference and a production task. Results suggest a role of the L1, with English-speaking German L2 learners performing more like L1 German speakers. While French-speaking German L2 learners’ performance could not be predicted by other factors, L2 German proficiency and the ability to produce analogous words were predictive of English-speaking German L2 learners’ production performance.

Keywords: analogy, L1 effects, L2 German, lexical stress, perception, production

1. Introduction

Stress assignment distinguishes pairs of English words like ˈimport (a noun) and imˈport (a verb). English speakers often lengthen stressed syllables and reduce the vowels in unstressed syllables to indicate which syllable receives the emphasis in a given word, which, in turn, constrains lexical access for the listener (Cooper et al. 2002). Lexical stress also distinguishes words in other languages including Spanish (e.g., Soto-Faraco et al. 2001), Dutch (Donselaar et al. 2005) and German (e.g., Wiese 2000). For learners of a second language (L2), incorrect stress assignment can present challenges to being understood (Bond and Small 1983; van Heuven 2008), especially when coupled with a foreign accent (Caspers 2010).

Researchers often attribute L2 stress assignment difficulties to a speaker’s first language (L1). That is, speakers of languages that exploit stress to distinguish meaning (e.g., Spanish, English, German) are better able to perceive stress than those whose L1s (e.g., French, Finnish, Hungarian) do not rely on stress for meaning (e.g., Dupoux et al. 1997). L1 differences may carry over to production, with speakers sometimes using stress assignment cues and patterns from their L1s (e.g., Yoon and Heschuk 2011; Zhang et al. 2008). In the current study we investigate whether participants whose L1s differ in the extent to which stress is contrastive, English and French, diverge in their perception and production of L2 German stress. Specifically, we examine stress assignment preferences among Canadian English and Canadian French learners of L2 German and compare them to those of L1 German speakers. Whereas lexical stress assignment in English and German is variable and rule-governed, with stress distinguishing meaning and falling on one of the last three syllables (e.g., Wiese 2000), French words are not distinguished on the basis of stress assignment, and stress always falls on the last syllable (Walker 1984). Acoustically, lexical stress in English and German is realized via a number of possible cues including duration, pitch, and intensity (e.g., Fry 1958). In French, final syllables are longer in duration than other syllables in a word (Walker 1984). We might, therefore, expect that L1 English and French speakers would assign stress differently from one another in their L2 German.

Because stress assignment is a lexical phenomenon, it is quite possible that factors related to the lexicon play a role in an L2 learners’ ability to assign stress. While it may be possible for L2 learners to store and / or assign lexical stress to each word independently, they may rely on similarities across words in the L2. As such, they may assign stress similarly to analogous words within the L2. Participants across a range of L1s and L2s have been shown to rely on analogy in the assignment of lexical stress (e.g., Aske 1990; Bullock and Lord 2003). Because German lexical stress is morphophonologically governed, relying on analogy may be an effective means of assigning lexical stress.

Guion (2005) notes that research into L2 lexical stress assignment falls into three main areas: the role of syllable structure (e.g., heavy syllables may attract stress), the importance of lexical class (e.g., stress may assigned differently to nouns and verbs), and analogical extension on the basis of phonological similarity (i.e., words that rhyme tend to be stressed similarly). Unlike these previous studies, the current research investigates the role of analogical extension on the basis of morphological similarity (i.e., the presence of particular suffixes that govern lexical stress assignment). In this study we use nonsense words as a window into the larger stress assignment system for participants from three L1 backgrounds: English, French, and German. We compare how English-speaking and French-speaking learners of German assign stress to real German words in a perceptual task. By extension, their preferences about where stress should fall in nonsense words – both in a perceptual task and in a production task – provide insights into learners’ stress assignment systems. In doing so, we can also investigate whether learners assign stress systematically, to groups of words that share features (e.g., suffixes), or lexically. If learners assign stress lexically, they will show variability within words containing the same suffix. For example, the following words ending in -ung should be stressed on the penultimate syllable: Faktuˈrierung (‘billing’), Etiketˈtierung (‘labeling’), Fokusˈsierung (‘convergence’), Digitaliˈsierung (‘digitization’). Learners who assign stress to syllables other than the penultimate syllable in any of these words are not making use of analogy and are instead assigning stress to the words lexically. By examining additional factors including German proficiency, age of learning, and the length of residence in a German speaking country, we can probe the role of experience in lexical stress assignment.

2. Literature review

2.1. Perceiving L2 lexical stress

Much of the research into the perception of L2 prosody (i.e., lexical and sentential stress, rhythm, and intonation) has demonstrated that participants’ perception is shaped by the L1 prosodic system. Recent studies have shown that L2 learners differ in their abilities to perceive prosodic cues that are not contrastive in their L1 (e.g., tones in Braun et al. 2014; Braun and Johnson, 2011; So and Best 2014; consonant length in Hayes-Harb and Masuda 2008). Like other prosodic features, lexical stress perception may be shaped by the L1. Research by Archibald (1992, 1993, 1998 demonstrated that native speakers of Polish, Spanish, and Hungarian perceive L2 English stress differently on the basis of the features (e.g., vowel quality, duration) that are relevant to lexical stress assignment in their L1s. Some research has shown relative success among L2 learners when lexical stress is assigned similarly across the L1 and the L2. Cooper et al. (2002) found that Dutch learners of English perceived English stress similarly to native English speakers, as stress is contrastive in Dutch and is signaled via similar acoustic cues.

Some speakers may be unable to perceive lexical stress when it is not contrastive in their L1. This has been referred to as “stress deafness” (Dupoux et al. 1997; Dupoux et al. 2008; Peperkamp and Dupoux, 2002). Participants in these studies have carried out tasks (i.e., AX and ABX tasks) requiring them to determine whether two words are different on the basis of lexical stress assignment. The French listeners in Dupoux et al. (1997) were less accurate than Spanish listeners in their ability to perceive lexical stress in Dutch nonsense words in an ABX task. Similarly, French listeners in Dupoux et al. (2008) were unable to perceive differences in lexical stress assignment in their L2 Spanish, causing the researchers to conclude that native French speakers cannot encode word stress in short-term memory. Speakers of other languages also have difficulty perceiving lexical stress. For example, the Mandarin – but not the Korean – learners of English in Lin et al. (2014) were able to use acoustic cues to lexical stress assignment in a lexical decision task. Like English, Mandarin makes use of acoustic cues (pitch) to distinguish meaning.

It may be that what appears to be an inability to perceive lexical is affected by the task that listeners perform. Tremblay (2009) demonstrated task effects in her study investigating Canadian French speakers’ ability to perceive English lexical stress. Performance varied depending on whether the tokens were spoken by a single speaker vs. multiple speakers. Whereas Dupoux et al. (2008) used tasks that required a relatively high processing load (i.e., multiple voices for stimuli) without investigating participants’ improvement over the course of the study, Tremblay (2009) manipulated processing load by making use of phonetically variable (i.e., three different speakers for each token) and phonetically invariable tokens (i.e., three tokens spoken by one speaker) and tracked participants’ performance over time. The Canadian French listeners were successful in encoding lexical stress in an AXB task in which the tokens did not contain phonetic variability; however, when variability was added, participants responded more slowly and less accurately. Performance improved as the number of trials increased.

2.2. Producing L2 lexical stress

Lexical stress assignment errors are common in production, and a few studies have demonstrated evidence of direct L1 transfer. The single native speaker of French in Yoon and Heshuk (2011) produced three-, four-, and five-syllable L2 English words with a French-like stress pattern (i.e., stress on the final syllable) regardless of the frequency of the word being produced. Nonetheless, other studies have demonstrated a relative lack of L1 effects, such as learners producing stress on a default syllable, regardless of their L1 stress assignment patterns. For example, the L2 learners of Dutch in Caspers and Kepinska (2011) who spoke French, Mandarin, Polish and Hungarian as their L1s, produced stress on the same default syllable when assigning stress in their L2 Dutch. Other studies are less straightforward. In his investigation into French-English bilinguals’ production of lexical stress in English nonsense words, Pater (1997) found little evidence of systematicity. Participants showed stress assignment patterns that were different from those of their L1 and L2. Similarly, the German-speaking English L2 participants in Erdmann (1973) and the Spanish-speaking English L2 learners in Mairs (1989) produced stress in English words in ways that were neither predicted by their L1 (i.e., German or Spanish) nor by their L2 English.

2.3. Modelling L2 stress perception and production

Models including the Stress Typology Model (Altmann 2006) and the Stress Parameter Model (Peperkamp and Dupoux 2002) both the predict a strong influence of the L1 in the assignment of L2 lexical stress. Increasingly, studies have investigated learners’ perception and production of lexical stress assignment together. Chen (2013) and Chung and Jarmulowicz (2017) found relatively high accuracy in both perception and production of English lexical stress among L1 speakers of the tonal languages Mandarin and Cantonese. Both languages, like English, make use of pitch in the assignment of meaning. The Mandarin speakers in Chung and Jarmulowicz (2017) assigned stress to derived English pseudowords in both a perceptual judgment task and a production task. The participants in Chen (2013) perceived and produced real and nonsense English words that were presented as verbs “I’d like to … ” or nouns “I’d like a … ” While the participants achieved high accuracy in the perception and production of lexical stress in real words, they were much less accurate on nonsense words.

Nonetheless, participants’ performance on perceptual tasks does not always align with their performance on production tasks. Altmann (2006) investigated whether speakers from six distinct L1 groups (i.e., Arabic, Chinese, French, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, and Turkish) could perceive and produce English lexical stress. He found that participants who spoke L1s with predictable stress (i.e., Arabic, French, Turkish) had difficulty perceiving – but not producing – lexical stress. Those participants in the study who spoke L1s either without word-level stress (i.e., Chinese, Japanese, Korean) or those with unpredictable stress (Spanish) performed well in perception but not production.

Tremblay (2008) looked at whether native speakers of Quebec French could use lexical stress to identify English words. A perceptual task required participants to make use of cues to lexical stress to determine which truncated word was produced in sentence-final position (e.g., whether they heard ˈmystery or misˈtake when they were presented with the syllable [ˈmɪs]). Participants only heard the first syllable of the word and had to determine, on the basis of acoustic cues, which of the two words had been cut off. Although they were significantly less accurate, the French listeners in this study, like the L1 English listeners, performed better on the task when the first syllable was stressed (i.e., ˈmystery) than when it was unstressed (i.e., misˈtake). The production task in the same study showed that French-speaking participants were more accurate in their production of two- and three-syllable words containing first-syllable stress than those requiring second-syllable stress. Because the participants did not rely on a final-syllable default stress assignment pattern, the author argues that the participants did not transfer their L1 stress assignment patterns to their L2 English.

2.4. The role of analogy in lexical stress assignment

While the studies reviewed above do show some differences along L1 lines, it may be wise to consider the role of additional factors, especially those related to participants’ experience with particular lexical items. Recent research supports the idea that both L1 speakers and L2 learners have difficulty producing metalinguistic rules regarding lexical stress assignment (e.g., Lord 2007; O’Brien 2019; Wrembel 2015). While this does not mean that learners are not relying on rules in assigning stress, it does show that it is difficult to tap into L2 learners’ explicit awareness of the L2 stress assignment system. An alternative to a reliance on the L1 system or rules is that learners make use of analogy (i.e., “a relation between surface forms”, Bullock and Lord, 2003, p. 281) in assigning stress to unknown words. Thus, even if they are unable to produce rules, it may be possible to determine if their system is based on regularities: they should assign stress in the same way to tokens (i.e., both real and nonsense) that are similar (Lord 2007). According to Skousen’s (1989) Analogical Model of Language, speakers’ linguistic behaviours are based on relevant stored exemplars, or the “most similar instances” (Skousen 2002, p. 11). Thus, speakers may use analogy to predict the pronunciation of an unknown form on the basis of a known similar form. Skousen notes that performance is based on individual occurrences in the case of analogy (p. 23). In general, research has demonstrated that analogy can be an effective way to learn to pronounce unknown words (e.g., He et al. 2005; Moustafa 1995; Woore 2007).

In both perceptual and production tasks, a comparison of participants’ lexical stress assignment in real and nonsense words provides insights into their reliance on analogy. If they assign stress in similar ways across words with similar forms (i.e., those that rhyme or that are morphologically similar), it is quite likely that participants rely on analogy. Bullock and Lord (2003) argued that the beginner level learners of L2 Spanish in their study produced lexical stress in nonsense words on the basis of analogical extension. That is to say, they assigned stress to these words analogously to those of similar real words, which further supports Aske’s (1990) findings that Spanish speakers are more likely to rely on analogy (i.e., based on stress assignment probabilities in the lexicon as a whole) than a rule when assigning stress.

Tight (2007) investigated stress assignment preferences of English-speaking Spanish L2 learners when they were provided with nonsense nouns and adjectives in a perceptual task. The nonsense words under investigation do not conform to the default rules of Spanish stress assignment. For example, although words ending in vowels are usually stressed on the penultimate syllable as in parˈlero (‘talkative’), there are exceptions for words ending in particular suffixes. Those ending in -ico/-ica are stressed on the antepenultimate syllable as in ˈmusica (‘music’). The more advanced L2 learners in the study demonstrated a reliance on analogy in that they preferred the pronunciations of the target items that could be predicted on the basis of similarity with real words.

Chen (2013) provided less clear support for reliance on analogy among Cantonese-speaking English L2 learners. In addition to reading words aloud, participants also completed a task that required them to produce real words that were phonologically similar to nonsense words. Chen determined that participants’ production of nonsense words in the carrier phrase were marginally correlated with their performance on the analogy task. When taken together with the finding regarding more accurate performance on real than on nonsense words overall, the author concluded that participants in the study may have relied more on lexical storage than analogy.

In the current study, participants’ use of analogy in L2 nonsense word stress assignment is determined in the following ways:

-

a.

in perception, through participants’ perception preferences for real words with the same suffixes; and

-

b.

in production, through participants’ ability to produce similar real words.

2.5. Individual factors affecting lexical stress assignment

There is a range of individual factors influencing learners’ ability to perceive and produce L2 lexical stress. One is proficiency. Although some research has demonstrated variability in perceiving stress within a given proficiency level (e.g., Tremblay 2008, 2009; Tremblay and Owens 2010) or only insignificant differences between participants’ perceptual abilities on the basis of target language proficiency (e.g., Archibald 1992; Dupoux et al. 2008), other research has shown that those with advanced proficiency may indeed perceive and produce lexical stress most accurately (e.g., Lord 2001, 2007; Maczuga et al. 2017). Ou (2010) found differences in Taiwanese participants’ ability to perceive English lexical stress on the basis of how long they had been learning English, with those learning English for 10 or more years performing differently from those who had been learning English for three or fewer years.

One final factor that may affect learners’ performance is lexical familiarity: participants tend to assign lexical stress more accurately to words they know well than to words with which they are less familiar (e.g., Lord 2007; Maczuga et al. 2017). Researchers who investigate lexical stress assignment have tried to mitigate the role of familiarity by relying on nonsense words. It is assumed that encountering nonsense words is similar to encountering new words and L2 learners may rely on rules or analogy with similar L2 words to assign stress (e.g., Guion 2005; Guion et al. 2003).

2.6. Methodological considerations

Studies investigating lexical stress perception use a range of methods, which may play a role in the outcomes of laboratory experiments. These include, but are not limited to, the context (e.g., individual or paired tokens vs. tokens in a sentential context), the ways in which acoustic cues are manipulated (e.g., micro manipulations of individual cues along a continuum vs. robust acoustic cues occurring in tandem), and the tasks employed (e.g., auditory discrimination vs. tasks requiring lexical encoding). For example, in spite of the evidence provided by Lin et al. (2014) demonstrating that Mandarin speakers are able to encode stress in an auditory lexical decision task with single word tokens, the results of Ou (2010), which presented tokens in a sentential context, are less straightforward. Within a sentential context, cues to lexical stress assignment co-occur with, for example, cues to sentence structure. This may make the task of perceiving lexical stress more difficult. In Ou’s (2010) study, which investigated whether Mandarin speakers could use pitch as a cue to lexical stress in L2 English nonsense words, participants could rely on high pitch to identify stressed syllables when they occurred in statements (i.e., with a falling intonation contour), but they were unable to explicitly identify stressed syllables that appeared in questions (i.e., within a low rising intonation contour). If the primary goal of a study is to investigate the L2 lexical stress system, it may be wise to begin by determining whether L2 learners are able to assign stress in the absence of context. Moreover, if we are ultimately interested in whether learners make use of lexical stress to encode meaning, it is wise to make use of tokens containing robust acoustic cues as well as those whose lexical stress can be determined on the basis of morphophonological information.

3. The current study

3.1. Assigning lexical stress in French, German, and English

Lexical stress assignment in German takes place at the interface of morphology and phonology. By default, stress is assigned to the penultimate syllable (Wiese 2000). This is true of many word types including those ending in schwa. Acoustic cues to German lexical stress include pitch, duration and intensity. Stress assignment in complex words depends on a word’s suffix: some suffixes attract stress, and others do not (Wiese 2000). Thus, although the stress assignment system of German is complex, it is rule-governed and highly predictable. As noted in the introduction, English lexical stress assignment, although different from that of German, makes use of the same set of acoustic cues and is also complex and rule-governed (Fry 1958). Lexical stress is not distinctive in French, and French words are stressed on the final syllable (Walker 1984). By relying on participants from both L1 groups in the current study, it is possible to examine L1 effects.

The current study investigates the role of the L1 and participants’ reliance on analogy in determining how L1 English and French speakers assign stress to nonsense words in their L2 German. Specifically, it seeks to answer the following research questions:

How do French-speaking and English-speaking German L2 learners and L1 German speakers assign stress to complex nonsense German words in a perceptual preference (SPP) task?

How do French-speaking and English-speaking German L2 learners and L1 German speakers assign stress to complex nonsense German words in a production task?

Models including the Stress Typology Model (Altmann 2006) and the Stress Parameter Model (Peperkamp and Dupoux 2002) predict differences between the two groups of L2 learners based on their L1s, with L1 French speakers demonstrating difficulty with stress assignment, as lexical stress is not encoded in French. It may be that participants’ performance can further be predicted on the basis of their ability to assign lexical stress to similar real words. By appealing to Skousen’s (1989) Analogical Model of Language, we may predict that participants’ ability to assign lexical stress to nonsense words is best predicted by their ability to assign lexical stress to similar real words.

4. Method

4.1. Participants

Three groups of participants took part in the current study. The experimental participants from Canada consisted of one group of French-speaking German L2 learners and one group of English-speaking German L2 learners. The third group consisted of L1 German speakers who acted as controls. All participants were recruited from the student populations at their universities, which were in French-speaking Canada, English-speaking western Canada, and northern Germany. All participants were paid for their involvement ($40 or €15). The first group (n = 13) was composed of seven female and six male L1 French speakers from 18 to 30 years old (mean age 23.15), and the second group (n = 14) consisted of l0 female and four male L1 English speakers between the ages of 18 and 27 (mean age 21.71). Thirteen L1 German speakers acted as a control group. There were 12 females and one male, and they ranged from 19 to 26 years old (mean age 22.62).

The L1 speakers of French and English completed a 30-cloze question German language proficiency exam (Goethe Institut 2004). Participants in the French group, who had been learning German for an average of 3.58 years, scored an average of 16.62 on the proficiency test. The L1 English speakers, who had been learning German for an average of 2.93 years, scored an average of 14.5. None of the differences between the two groups of German learners were significant. These include proficiency (t(25) = 1.97, p = 0.06), age at the time of the study (t(25) = 1.15, p = 0.26), age of learning German (t(25) = 1.19, p = 0.90), time spent learning German (t(25) = 1.10, p = 0.28), and time in a German-speaking country (t(25) = 1.45, p = 0.16).

4.2. Tokens

Experimental tokens were three-syllable German nonsense words, which are common in studies investigating L2 stress assignment (e.g., Bullock and Lord 2003; Guion et al. 2003; Lord 2007; Pater 1997; Tight 2007; Tremblay 2009). Using nonsense words guarantees that performance on the task is not due to a token’s frequency or a participant’s familiarity with it. Researchers can therefore investigate issues related to the overall stress assignment system as opposed to factors related to individual lexical items. A total of 32 three-syllable complex nonsense words containing morphological cues to lexical stress assignment (i.e., suffixes) served as tokens in the current study. The eight tokens containing the suffixes -schaft, -heit, -iker and -tum (two per suffix) should be stressed on the first syllable, the eight tokens with the suffixes -er, -ik, -ung and -or (two per suffix) should be stressed on the second syllable, and the eight tokens with the suffixes -ant/-ent, -ie, -ei, and -ion (two per suffix) should be stressed on the final syllable. An additional eight nonsense tokens ending in a suffix containing schwa (-ade, -el, -ette, or -e) and stressed on the second syllable were also used. These are considered the baseline, as words ending in schwa are always stressed on the penultimate syllable, which is the default syllable for stress assignment in German. Before arriving at the final set of nonsense words, the first author created a superset set of written nonsense words that conformed to the requirements of the study (i.e., three syllables, containing the appropriate suffixes). Nine L1 speakers of German were asked to provide goodness ratings for the nonsense words on a scale from 1 (“This is a bad German ‘word.’ I could not imagine ever hearing this ‘word.’”) to 5 (“This is a good German ‘word.’ I could imagine actually hearing this ‘word.’”). The two nonsense words that received the highest ratings for each suffix were chosen as tokens for the current study. The final set of experimental tokens and their goodness ratings are provided in Appendix A. A total of 32 real-word fillers that conformed to the specifications of the nonsense words served as controls.

4.3. Tasks

4.3.1. Stress preference perception task

The first task, a stress preference perception (SPP) task, was based on Guion et al. (2003) and Guion (2005). Its purpose was to determine the lexical stress assignment preferences of French-speaking and English-speaking German L2 learners. Participants indicated their preferences by choosing which stressed syllable they prefer (e.g., three versions of a three-syllable word: one with stress on the first syllable, one with stress on the second syllable and one with stress on the final syllable). Guion (2005) notes that this task places relatively low processing demands on participants. In the current study, the task consisted of 32 experimental nonsense words, 32 real word controls, and 102 filler items. For each trial, as exemplified in (1), the participants were presented with the orthography of a word in the center of the computer screen. There were three circles below the word, each of which corresponded to a potential production of the word they saw. For the experimental and real word tokens, the three possible productions were as follows: one with stress on the first syllable (i.e.,ˈDockenheit), one with stress on the second syllable (i.e., Doˈckenheit), and one with stress on the third syllable (i.e., Dockenˈheit).

(1).

| Dockenheit | |||

| Listen |

|

|

|

| Choose |

|

|

|

The participants were told that they would “see a series of possible German words and decide how they should be pronounced,” which they did by clicking on the rectangle under the correct production. The participants could listen to each of the tokens as often as they wished within a 3,000-ms time window, and the number of times they listened to each of the three tokens was recorded. A correct response required choosing the token with the stress placed on the correct syllable. The number of times participants listened to the choices for a given item can be taken as evidence of their difficulty with their choices. For example, if participants from a given group listen more frequently to words that should be stressed on the third syllable, it may be a sign that they have difficulty distinguishing between stress on that and another syllable.

A female L1 German speaker recorded all of the words used in the experiment. The experimental tokens were acoustically analyzed to ensure that they contained robust cues to lexical stress assignment. A one-way between-groups ANOVA was conducted to ensure that the relevant acoustic cues (i.e., duration of the stressed syllable, mean intensity of the stressed syllable, and mean frequency of the stressed syllable) to lexical stress assignment were indeed present in the intended syllables. We expect, for example, that a word stressed on the first syllable would have a longer first syllable than a second and third syllable and that its mean intensity and mean F0 would be higher than those on the second and third syllables. Overall, the acoustic cues to lexical stress assignment were robust, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Acoustic cues to lexical stress assignment in the experimental tokens.

| stressed syllable duration | stressed syllable mean intensity | stressed syllable mean F0 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d.f. | F | p | d.f. | F | p | d.f. | F | p | |

| Syllable 1 stress | 2 | 13.52 | <0.0001 | 2 | 5.67 | 0.005 | 2 | 5.63 | 0.005 |

| Syllable 2 stress | 2 | 37.07 | <0.0001 | 2 | 11.30 | <0.0001 | 2 | 2.20 | 0.116 |

| Syllable 3 stress | 2 | 9.41 | <0.00001 | 2 | 13.00 | <0.0001 | 2 | 5.78 | 0.004 |

The filler items differed from the experimental and control tokens in that they consisted of two-, three-, and four-syllable real German words. Eighty-four of the words were segmentally modified, such that either vowels or consonants were replaced. The remaining 18 filler items were three-syllable simplex words (e.g., Vagabund, Diplomat) in which the stress was modified as with the real word controls. Simplex words were chosen to balance out the experimental tokens in terms of morphological complexity. The experimental task, which was designed in Experiment Builder, was preceded by three practice trials, so that participants could become accustomed to the timing of the experiment and ask any questions before beginning the task. Trials and the order of the three versions of each token were randomized for each participant.

4.3.2. Nonsense word production task

The second task was a production task whereby participants were required to read a word in the carrier phrase Wenn ich an ________ denke, denke ich an … (“When I think of _______, I think of … ”) and produce as many associated words as possible within 10 seconds. The nonsense words and the analogous words were in the stressed position of a carrier phrase as is common in studies investigating lexical stress assignment (e.g., Chen 2013; Tremblay 2008). The task was based on the word similarity task in Guion et al. (2003) and Chen (2013). Its purpose was to determine stress assignment preferences in production for French-speaking and English-speaking German L2 learners. Moreover, in addition to producing the target items, participants were required to produce any similar German words they could come up with, thereby encouraging them to rely on analogy. Specifically, they were told that “similar” words should have a similar ending and be emphasized in a similar way.

The participants read each sentence aloud, and the audio for each trial was recorded. The same set of nonsense words were chosen for the perceptual and production tasks to enable comparison across the two tasks. In addition to the same 32 three-syllable nonsense words that were used as in the SPP task, participants produced 45 nonsense filler words. These filler nonsense words were all created to resemble real simplex words. Thirty-seven of them contained three syllables, and the remainder were bisyllabic. Participants were presented with the sample recording of the text provided in (2) before proceeding to two practice trials.

(2).

| Wenn ich an Gameneur denke, denke ich an Redakteur, Amateur, Ingenieur, Friseur. |

| When I think of Gameneur, I think of editor, amateur, engineer, hairdresser. |

The target nonsense word, Gameneur, is provided in bold, and the underlined words are examples of real words that have the same suffix and thus could serve as examples for how the target item should be stressed. Participants had the opportunity to ask any questions before beginning the task.

4.4. Procedure

For both tasks, the participants met the research assistant in the laboratory. Instructions were provided by the research assistant in each participant’s L1. Two versions of the experiment were created: one for English and one for French L1 speakers. After they signed the consent form and completed the language background questionnaire, participants completed the experiment as follows: SPP task, proficiency test, production task. Participants could take up to three scheduled breaks during each experiment, and they were encouraged to take a longer break between tasks. Each session typically lasted between one-and-a-half and 2 h.

4.5. Data analysis

Responses from the SPP task were analyzed for correctness and for number of listens. Correctness was determined based on the responses provided by L1 German listeners, as in Lord (2007). That is to say, if at least 12 of the 13 L1 listeners agreed on a given token and if stress was assigned according to German lexical stress assignment rules, it was considered correct. L1 German listeners agreed 100% of the time on 24 of the 32 words overall, and they achieved agreement of 92% (i.e., agreement by 12 of 13 listeners) for six of the remaining target items (Gulator, Hollerei, Kellentum, Lowine, Silument, Tickerei). They did not achieve the 92% threshold for two items (Paffessor, Pakapter). As such, these were removed from analysis, and correctness for a total of 30 target items served as the dependent variable in the analyses of the SPP data. In addition, the total number of times participants listened to each production of an individual nonsense word was also considered in the analyses as evidence of the relative difficulty participants had in assigning stress to a given token.

Production accuracy was determined in a similar way to accuracy on the perceptual task. That is, when 92% of L1 German speakers produced lexical stress on the same syllable and if that production aligned with German stress assignment rules, that pronunciation was considered the correct response. L1 German speaker responses were in complete alignment with the expected production of 26 of the 32 target items, and they reached the 92% threshold for four of the remaining items (Holade, Hollerei, Kassiker, Robistik). There were only two target items for which the productions of at least 12 L1 speakers did not align (Fotation, Tillusion). As such, the total number of target items for the production task was 30. All tokens were independently evaluated for the location of the stressed syllable (first, second or third) by both authors, both L1 speakers of English with advanced to near-native proficiency in German and with proficiency in French. After they completed the initial analysis of the data, responses were compared. Agreement on the location of the stressed syllable was reached on 89.1% of the productions. Those that differed were discussed, and a decision was reached for all but 5% of those words. A total of 1185 target items were analyzed for the production task. The total number of analogous words participants produced was also analyzed as evidence of participants’ reliance on analogy in the production of the nonsense words. Although we also expected to analyze the accuracy of lexical stress assignment in these similar words, this was not possible. Instead of producing analogous words with the appropriate lexical stress assignment, participants tended to produce contrastive lexical stress in their productions, most probably as a way of distinguishing these from the target items themselves.

All data were analyzed using an unbalanced repeated-measures design using a Generalized Estimating Equation (i.e., GEE under Genlin procedures in SPSS v. 25) to determine the extent to which English-speaking and French-speaking German L2 learners were able to accurately assign stress in perception and production. Analyses were also run to determine the respective role of speaker characteristics (i.e., speaker L1, L2 proficiency, age of learning German, and time spent in a German-speaking country) in the accuracy of lexical stress assignment in the perception and production of German nonsense words. GEE analyses are preferred over other analyses in instances in which there are potential correlations among data points. It is likely that a participant’s accuracy on any given token in this study is correlated with their accuracy on any other token. In addition, the model allows for the addition of predictor variables including speaker and lexical factors. The data from this study met the basic assumptions of GEE analyses: normal distribution and correlated and unbalanced outcomes. An alpha level of 0.05 was applied to all analyses.

5. Results

5.1. Perception

First, the extent to which participants correctly assigned stress to real word tokens as opposed to the target nonsense word tokens was determined. A summary of performance by group is provided in Table 2. The number of listens listed in the table corresponds to the total number of times participants clicked on items during a single trial. Because participants were required to listen to each of the three potential productions at least once, the minimum number of listens is always three. A participant who listened to one of the three productions a second time would thus have a listen score of four.

Table 2:

Accuracy of perception and number of listens to real and nonsense words by group.

| Real word correctness (SE) | Real word listens (SE) | Nonsense word correctness (SE) | Nonsense word listens (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 French | 0.60 (0.029) | 3.73 (0.137) | 0.54 (0.029) | 3.79 (0.165) |

| L1 English | 0.70 (0.031) | 3.53 (0.132) | 0.68 (0.037) | 3.52 (0.133) |

| L1 German | 0.99 (0.005) | 3.20 (0.067) | 0.98 (0.005) | 3.18 (0.072) |

Only French-speaking learners performed differently in their perception of primary stress in real and nonsense words, with significantly more nativelike performance in their perception of real words (B = −0.215, SE = 0.0962, χ2(1) = 4.982, p = 0.026). English-speaking learners did not differ in the nativelikeness of their stress assignment preferences for real and nonsense words.

The results of the test of model effects indicate a significant effect of group. In terms of perceptual performance on target items (i.e., the nonsense words), French-speaking learners (B = −4.24, SE = 0.5562, χ2(1) = 58.111, p < 0.001) and English-speaking learners (B = −3.777, SE = 0.563, χ2(1) = 45.063, p < 0.001) differed significantly from L1 German listeners. The results of pairwise comparisons demonstrate that English-speaking learners performed significantly more like L1 German speakers than did French-speaking learners (p = 0.005). Looking at the number of times listeners in each of the three groups listened to tokens overall, we again see an effect of group with French-speaking learners (B = 0.522, SE = 0.1523, χ2(1) = 11.726, p = 0.001) and English-speaking learners (B = 0.329, SE = 0.1477, χ2(1) = 4.952, p = 0.026) listening to the tokens significantly more than L1 listeners of German before making their choices. There were no differences in the number of listens for the experimental groups.

Next, we analyzed participants’ stress preferences for the target items according to the stressed syllable: the first syllable in items ending in -schaft, -heit, -iker and -tum; the second syllable in items with the suffixes -er, -ik, -ung and -or; the final syllable in items ending in -ant, -ent, -ie, -ei, and -ion. Performance on these items was compared to that of tokens ending in a schwa suffix (-ade, -el, -ette, or -e). A summary of performance by group and stressed syllable is provided in Table 3.

Table 3:

Correctness of perception by stressed syllable and group.

| 1st syllable perception EMM (SE) | 2nd syllable perception EMM (SE) | 3rd syllable perception EMM (SE) | schwa perception EMM (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 French | 0.72 (0.058) | 0.40 (0.05) | 0.46 (0.07) | 0.55 (0.067) |

| L1 English | 0.72 (0.06) | 0.58 (0.078) | 0.56 (0.062) | 0.79 (0.059) |

| L1 German | 0.99 (0.009) | 0.99 (0.012) | 0.98 (0.014) | 0.98 (0.011) |

The results of a test of model effects indicate an effect of group and syllable stressed as well as an interaction between group and syllable stress. The effect of group is similar to the overall results, with French- (B = −0.436, SE = 0.0679, χ2(1) = 41.274, p < 0.001) and English-speaking learners’ (B = −0.190, SE = 0.0605, χ2(1) = 9.85, p = 0.002) performance on the perception of primary stress different from that of L1 German speakers. The results of pairwise comparisons indicate that English-speaking learners performed significantly more like L1 German listeners in their perceptual preferences as compared to French-speaking learners (p = 0.004).

The results of pairwise comparisons indicate that participants were, overall, more nativelike in their preferences for tokens stressed on the first syllable than those stressed on the second (p = 0.005) and third syllables (p = 0.003). In addition, participants were more accurate in their perception of tokens ending in schwa as compared to those stressed on the second (p = 0.02) and third syllables (p = 0.02). When compared to their performance in the perception of primary stress in tokens ending in schwa, French-speaking learners did not perform significantly differently based on the syllable being stressed in a given word, although the difference neared significance in the perception of words stressed on the first syllable (B = 0.169, SE = 0.0892, χ2(1) = 3.61, p = 0.057). English-speaking learners were significantly more nativelike in their perceptual preferences for words ending in schwa than those stressed on both the second (B = −0.215, SE = 0.0813, χ2(1) = 6.993, p = 0.008) and third syllables (B = −0.227, SE = 0.0901, χ2(1) = 6.355, p = 0.012). Their perceptual preferences for words stressed on the first syllable did not differ from those ending in schwa in terms of nativelikeness. In addition, English-speaking learners were significantly more nativelike in their perception of tokens stressed on the first than on the third syllable (p = 0.016). A comparison of French- and English-speaking learners in terms of the nativelikeness of their preferences shows significant performance differences for tokens stressed on the second syllable (p = 0.047) and for tokens containing a schwa syllable (p = 0.006), with English-speaking learners showing more nativelike perceptual performance than French-speaking learners.

With regards to the number of times participants listened to words that were stressed on the first, second, third, and schwa syllables, the test of model effects indicates a significant effect of group and an effect nearing significance of stressed syllable. There was no interaction of group and syllable stressed. The mean number of listens by syllable stressed is provided in Table 4.

Table 4:

Mean number of listens by word type.

| 1st syllable listens EMM (SE) | 2nd syllable listens EMM (SE) | 3rd syllable listens EMM (SE) | schwa word listens EMM (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 French | 3.88 (0.187) | 3.84 (0.225) | 3.86 (0.258) | 3.58 (0.106) |

| L1 English | 3.37 (0.125) | 3.64 (0.173) | 3.72 (0.224) | 3.41 (0.104) |

| L1 German | 3.26 (0.111) | 3.17 (0.076) | 3.16 (0.058) | 3.13 (0.071) |

The results of parameter estimates indicate that L1 German listeners listened significantly fewer times overall than both French- (B = 0.445, SE = 0.1278, χ2(1) = 12.12, p < 0.001) and English-speaking learners (B = 0.281, SE = 0.1256, χ2(1) = 4.986, p = 0.026). Participants listened more overall to tokens stressed on the first syllable than those ending in schwa (B = 0.123, SE = 0.0557, χ2(1) = 4.86, p = 0.027). French-speaking learners listened more often to words stressed on the first syllable than did English-speaking learners (p = 0.044) and L1 German listeners (p = 0.012). Both French- (p = 0.014) and English-speaking learners (p = 0.027) listened more often to words stressed on the second syllable than did L1 German listeners. A similar pattern held for words stressed on the third syllable, with French- (p = 0.025) and English-speaking learners (p = 0.033) listening more often than L1 German listeners. The same pattern was demonstrated for words ending in schwa, with French- (p = 0.001) and English-speaking learners (p = 0.05) listening more to these tokens than L1 German listeners.

French-speaking learners’ nativelike performance on target items could be predicted by their performance on analogous real words (B = −0.939, SE = 0.3417, χ2(1) = 7.555, p = 0.006), participants’ age when learning German (B = 0.071, SE = 0.0342, χ2(1) = 4.371, p = 0.037) as well as time spent immersed in a German-speaking environment (B = −0.517, SE = 0.1608, χ2(1) = 0.109, p = 0.001). Given the directionality of the parameter estimates (i.e., a positive estimate for age of learning and a negative estimate for time spent in Germany), older participants and those who had spent less time in a German-speaking environment performed in a more nativelike manner in the perception of stress in nonsense words. In addition, the negative parameter estimate for performance on analogous real words demonstrates that participants with the most nativelike performance on real word tokens did not exhibit the most nativelike performance on analogous nonsense word tokens. For participants in this group, other factors including the total number of listens, their proficiency in German, the time they had been learning German, and their listening motivation did not predict the nativelikeness of their performance on the target items.

Nativelike preferences on nonsense words for English-speaking learners could be predicted by their performance on analogous real words (B = −2.392., SE = 0.5311, χ2(1) = 20.287, p < 0.001) the total number of listens (B = 0.232, SE = 0.1171, χ2(1) = 3.918, p = 0.048) and their German proficiency (B = −0.229, SE = 0.0932, χ2(1) = 6.054, p = 0.014). English-speaking learners who listened to the items more frequently as well as those who were less proficient performed in a more nativelike manner in the stress perception task. As with French-speaking learners, those English-speaking learners whose assignment preferences for real words most aligned with those of L1 German speakers performed less nativelike on the nonsense word tokens. No other factors predicted English-speaking learners’ performance on the SPP task.

5.2. Production

To begin, we determined the extent to which participants correctly assigned stress to nonsense tokens overall. A summary of performance by group is provided in Table 5.

Table 5:

Target item production performance and number of analogous words produced by group.

| Nonsense word production EMM (SE) | Analogous real word production EMM (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| L1 French | 0.70 (0.023) | 1.03 (0.011) |

| L1 English | 0.79 (0.024) | 1.15 (0.086) |

| L1 German | 0.98 (0.006) | 1.14 (0.040) |

The results of the test of parameter estimates indicate a significant effect of group. Both French- (B = −0.281, SE = 0.0242, χ2(1) = 134.909, p < 0.001) and English-speaking learners (B = −0.194, SE = 0.0249, χ2(1) = 60.577, p < 0.001) produced lexical stress assignment significantly differently from L1 speakers of German. The results of pairwise comparisons demonstrate that English-speaking learners performed significantly more like L1 German speakers in the production of primary stress than did French-speaking learners (p = 0.009). If we look at the number of analogous real words produced overall, we again see an effect of group with French-speaking learners producing significantly fewer analogous words that L1 German speakers (B = −0.119, SE = 0.0411, χ2(1) = 8.355, p = 0.004). There were no differences in the number of analogous words produced by English-speaking learners and L1 German speakers. Participants in the two learner groups also did not differ from one another in the number of analogous words they produced.

As a next step we sought to analyze participants’ production accuracy for the target items according to the syllable that was stressed: the first syllable in items ending in -schaft, -heit, -iker and -tum; the second syllable in items with the suffixes -er, -ik, -ung and -or; the final syllable in items ending in -ant/-ent, -ie, -ei, and -ion. Because words ending in schwa are always stressed in the second syllable and are considered the default case, performance on the target items was compared to that of tokens ending in a schwa suffix (-ade, -el, -ette, or -e). A summary of production performance by group and stressed syllable is provided in Table 6.

Table 6:

Correctness of production by stressed syllable and group.

| 1st syllable production EMM (SE) | 2nd syllable production EMM (SE) | 3rd syllable production EMM (SE) | schwa production EMM (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 French | 0.75 (0.052) | 0.68 (0.048) | 0.51 (0.093) | 0.89 (0.039) |

| L1 English | 0.77 (0.04) | 0.69(0.058) | 0.77 (0.066) | 0.95 (0.028) |

| L1 German | 0.99 (0.009) | 0.99 (0.010) | 0.99 (0.012) | 1.00 (0.013) |

The results of a test of model effects indicate an effect of group and syllable stressed as well as an interaction between group and syllable stressed. French-speaking learners differed significantly in their production from L1 German speakers overall (B = −0.108, SE = 0.0414, χ2(1) = 6.808, p = 0.009). The results of pairwise comparisons indicate that English-speaking learners were significantly more nativelike in their production of primary stress than French-speaking learners (p = 0.011). The results of pairwise comparisons indicate that participants were, overall, more nativelike in their production of tokens ending in schwa than those stressed on the first (p = 0.001), second (p < 0.001) and third syllables (p < 0.001).

The results of parameter estimates investigating the interaction of group and stressed syllable indicate a significant interaction. French-speaking learners were significantly more accurate in producing tokens ending in schwa as compared to those stressed on the second syllable (B = −0.203, SE = 0.0561, χ2(1) = 13.085, p < 0.001) and on the third syllable (B = −0.365, SE = 0.0850, χ2(1) = 18.493, p < 0.001). English-speaking learners pronounced the schwa tokens significantly more accurately than tokens stressed on the first (B = −0.174, SE = 0.0486, χ2(1) = 12.871, p < 0.001), second (B = −0.249, SE = 0.0484, χ2(1) = 26.461, p < 0.001), and on the third syllable (B = −0.175, SE = 0.0795, χ2(1) = 4.832, p = 0.028). A comparison of French- and English-speaking learners in terms of the nativelikeness of their production of tokens indicates that English-speaking learners were significantly more nativelike than French-speaking learners in their production of tokens that were stressed on the final syllable (p = 0.027).

In order to investigate the extent to which participants were explicitly relying on analogous forms in their production of the nonsense target words, we investigated the number of analogous words participants produced that were similar to those stressed on the first, second, and third syllables as well as for words that ended in schwa syllables. The number of analogous words produced by syllable stressed is provided in Table 7.

Table 7:

Number of analogous words produced by target word stressed syllable.

| 1st syllable analogous words EMM (SE) | 2nd syllable analogous words EMM (SE) | 3rd syllable analogous words EMM (SE) | schwa word analogous words EMM (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 French | 1.03 (0.019) | 1.00 (0.001) | 1.05 (0.046) | 1.01 (0.014) |

| L1 English | 1.16 (0.098) | 1.16 (0.122) | 1.35 (0.267) | 1.02 (0.033) |

| L1 German | 1.08 (0.037) | 1.17 (0.055) | 1.05 (0.039) | 1.21 (0.069) |

The test of model effects indicates a significant interaction of group and syllable stressed. L1 German speakers produced more analogous words stressed on the second syllable (p = 0.006) and ending in schwa (p = 0.014) than did French-speaking learners. L1 German speakers also produced significantly more analogous words ending in schwa than did English-speaking learners (p = 0.014). The interaction of group by syllable stressed was significant. French-speaking learners produced significantly more analogous real words for target items stressed on the third syllable than they did for words ending in schwa (B = 0.198, SE = 0.0745, χ2(1) = 7.061, p = 0.008). English-speaking learners produced significantly more analogous real words for target items stressed on the first syllable than those ending in schwa (B = 0.271, SE = 0.0983, χ2(1) = 7.611, p = 0.006).

An analysis of predictor variables indicates that French-speaking learners’ production performance could not be predicted by any single variable. This includes number of analogous words produced (B = −0.245, SE = 0.2275, χ2(1) = 1.16, p = 0.282), proficiency in German (B = 0.015, SE = 0.0085, χ2(1) = 3.184, p = 0.074), age of learning German (B = −0.012, SE = 0.0087, χ2(1) = 1.856, p = 0.173), and time spent in a German speaking country (B = 0.012, SE = 0.0467, χ2(1) = 0.071, p = 0.790). English-speaking learners’ performance on the production of primary stress in the target items could be predicted by the number of analogous words they were able to produce (B = 0.026, SE = 0.0095, χ2(1) = 7.391, p = 0.007) and their proficiency (B = 0.033, SE = 0.0168, χ2(1) = 3.861, p = 0.049). Thus, English-speaking learners who were able to produce more analogous words as well as those who were more proficient were more likely to accurately assign lexical stress in the production task.

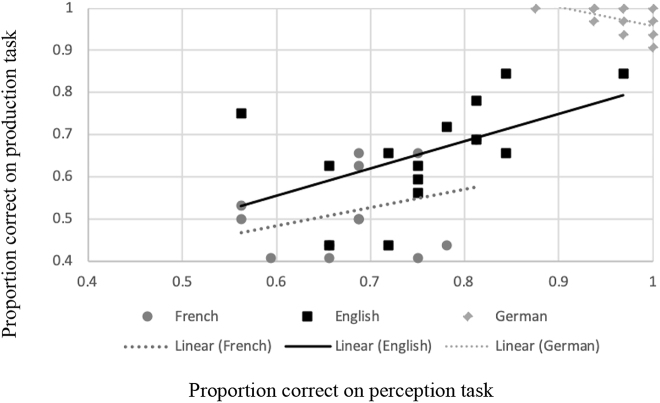

As a final step, to determine the extent to which participants’ perception and production are related, we used participants’ scores on the perceptual task as a predictor of their production performance (as supported by a large body of work, see, for example Escudero 2006; Saito and Kim 2018 for discussion). Performance in the production of primary stress could be predicted by perceptual performance for both French-speaking learners (B = 0.159, SE = 0.0633, χ2(1) = 6.314, p = 0.012) and English-speaking learners (B = 0.247, SE = 0.0535, χ2(1) = 21.253, p < 0.001). That is to say, for both groups of participants, their performance on one task was predictive of their performance on the other. To illustrate, Figure 1 below shows that, in general, as participants’ scores on perception tasks increased, so did their production scores. It also demonstrates higher overall accuracy for English-speaking learners and performance at ceiling for L1 German speakers.

Figure 1:

Participants’ scores on perception and production tasks.

6. Discussion

The results of the current study demonstrate that intermediate proficiency L1 English and French speakers differ significantly from one another and from L1 German speakers in their assignment of lexical stress to nonsense German words in both perception and production. English-speaking learners performed more like L1 German speakers overall. In the perceptual task, English-speaking learners performed in an equally nativelike manner on real and nonsense words, whereas French-speaking learners perceived real words more in a more nativelike manner as compared to nonsense words. French-speaking learners did not differ significantly in their perception of primary stress in nonsense words depending on the syllable being stressed. Nonetheless, their performance approached significance in the perception of primary stress on nonsense words stressed on the first syllable. That is, they were more likely to perceive nonsense words that were stressed on the first syllable similarly to L1 German listeners. In addition, they listened to tokens stressed on the first syllable significantly more often than those stressed on the other syllables. English-speaking learners were significantly more nativelike in their perception of German nonsense words that were stressed on the second syllable and those ending in schwa than nonsense words stressed on the first or third syllables.

The finding that French-speaking learners were less able than English-speaking learners to perceive L2 German lexical stress in a nativelike manner is not surprising on the basis of previous research that has shown that listeners tend to make use of features that are distinctive in their L1 (e.g., Archibald 1992, 1993, 1998). Because lexical stress is not contrastive in French, it has been proposed that L1 French speakers—unlike L1 English speakers—are less able to attend to lexical stress (e.g., Dupoux et al. 1997, 2008). The participants in the current study performed above chance (i.e., 33.3%). Their ability to encode lexical stress may have been affected by the task, in which they heard lexical stress on each of the syllables and were required to determine which assignment was appropriate. Like the participants in Tremblay (2008), L1 French speakers showed a tendency to perceive words stressed on the first syllable more similarly to L1 speakers when compared to words stressed on the other syllables. The processing load may have been reduced enough for participants to perceive differences in lexical stress assignment, along the lines of participants in Tremblay (2009). Nonetheless, in their perception of lexical stress on words stressed on the second and third syllables, French-speaking learners’ performance was at 40 and 46%, respectively. As such, the present findings support previous studies positing that lexical stress assignment poses difficulty for L1 French listeners.

In terms of the production of primary stress, the French-speaking learners were significantly less nativelike in their performance than were English-speaking learners overall. Whereas French-speaking learners produced significantly fewer analogous words than did L1 German speakers, English-speaking learners did not differ from L1 German speakers in terms of number of analogous words produced. When it comes to the accuracy according to syllable stressed, French-speaking learners – like English-speaking learners – were most accurate in their production of the default stress pattern in words ending in schwa. French-speaking learners produced the most analogous words for words stressed on the third syllable. Unlike the French learners of English in Yoon and Heshuk (2011) or the French learners of Dutch in Caspers and Kepinska (2011), who relied on a default strategy of assigning stress to the same syllable in English and Dutch words, respectively, the participants in the current study assigned stress to all of the syllables. If anything, the French-speaking learners in the current study did not make use of a French-like strategy in assigning lexical stress to the final syllable of German words, as their performance on nonsense words with final-syllable stress was significantly less nativelike than that on words ending in schwa.

In terms of differences across participants, French-speaking learners who were older as well as those who had spent less time immersed in a German-speaking location performed better on the perceptual task. For English-speaking learners, those who listened more to the tokens as well as those who were less proficient performed better overall on the perceptual task. Participants in both groups who perceived real words in a most nativelike manner were less likely to do so for nonsense words. While it is not surprising that English-speaking learners who listened more often to the tokens performed better on the perceptual task, the other predictors of perceptual performance are somewhat surprising, especially in light of literature that demonstrates enhanced perceptual performance with increasing proficiency and/or language use (e.g., Tremblay 2008, 2009). The fact that participants’ performance in the perceptual task for real and nonsense words did not align may provide evidence that participants may rely more on lexical storage than on analogy when they make decisions about lexical stress assignment, as proposed by Chen (2013). These somewhat surprising effects may be the sign of a perceptual system that is still very much under development. Although no participant variable predicted French-speaking learners’ performance on the production of primary stress, English-speaking learners’ production performance on the target items was predicted by both the number of analogous words they were able to produce and their proficiency in German. Neither of these predictor variables is surprising, and the effects align well with those of other lexical stress assignment studies (e.g., Lord 2007).

Requiring participants in this study to produce analogous words provided insights into the larger stress assignment system without requiring learners to produce rules or reflect on their productions. The finding that English-speaking learners who produced more analogous words overall were more accurate in their production of the target items aligns well with the predictions of Skousen’s Analogical Model of Language (Skousen 1989). That is, participants who were able to draw more on known similar words were also able to predict how to assign lexical stress to unknown words like the nonsense words in the current study as has been demonstrated for L2 learners from a range of L1 backgrounds (e.g., Aske 1990; Bullock and Lord 2003; Chen 2013; Tight 2007). On the basis of the results of the current study as well as those of O’Brien (2019), who demonstrated that participants were rarely able to produce stress assignment rules, analogy may be a better predictor of English-speaking learners’ production of L2 German lexical stress than are measures of metaphonological awareness including the production of German lexical stress rules or an explicit statement regarding where stress should be assigned in a given word. The finding that the production of analogous words did not predict the production performance of French-speaking learners is somewhat surprising, but when taken together with the finding these participants produced significantly fewer analogous words, this may provide further evidence that the French-speaking learners’ lexical stress assignment is less systematic overall.

That L1 English speakers performed in a more nativelike manner than L1 French speakers is not surprising on the basis of previous studies that have demonstrated that participants with variable L1 lexical stress systems are significantly more likely to acquire an L2 system with variable lexical stress. This finding is also in alignment with predictions made by models including the Stress Typology Model (Altmann 2006) and the Stress Parameter Model (Peperkamp and Dupoux 2002), which predict L1 effects in the acquisition of L2 stress. The French-speaking learners did not directly transfer their L1 patterns to their L2 German system, and they showed variability in their nativelikeness in lexical stress assignment depending on the syllable that was to be stressed in a given word. The findings of the current study are also supported by the Speech Learning Model (Flege 1995), which predicts a close alignment between perception and production. The production accuracy for participants in both groups was significantly predicted by their perceptual accuracy.

It is not surprising that participants’ performance on the perceptual task was strongly associated with their performance on the production task. Nonetheless, the L2 learners in this study demonstrated variability across the two tasks according to their first languages. Because this study made use of decontextualized nonsense words, we cannot say for certain whether performance on these tasks would generalize to the real world. An interesting avenue for subsequent research, especially on L2 German, is the association between lexical stress assignment and derivation. Future studies should investigate the extent to which L2 learners assign lexical stress in derived words in which lexical stress assignment switches syllables as a result of the process of derivation along the lines of Wade-Woolley and Heggie (2015). This will provide important insights into the lexical stress assignment system at the interface of morphology and phonology. Moreover, research methodologies that investigate the role of analogy in pronunciation – and especially stress assignment – should take steps to discourage participants from making use of contrastive stress in their production of analogous words. Encouraging participants to find words that rhyme with target words, for example, may be one way to ensure that participants assign stress appropriately to both target items and analogous words. Ultimately, a better understanding of developing L2 lexical stress systems will enable classroom practitioners to develop and test classroom and computer-mediated tasks that more effectively target this essential component of L2 comprehensibility.

Appendix A.

Nonsense tokens and goodness ratings

| Nonsense Word | Rating |

|---|---|

| Betackung | 4.44 |

| Bohnierung | 4.22 |

| Dalette | 4.44 |

| Detuganz | 3.67 |

| Dockenheit | 4.56 |

| Fotation | 3.89 |

| Gekummel | 4.22 |

| Getakel | 4.33 |

| Gulator | 3.56 |

| Holade | 4.11 |

| Hollerei | 5 |

| Kanerie | 4.11 |

| Kassiker | 4.11 |

| Keitentum | 4.22 |

| Kellentum | 3.78 |

| Kemetik | 3.88 |

| Leborter | 2.33 |

| Lipperschaft | 4.22 |

| Lowine | 3.78 |

| Neiberschaft | 4.11 |

| Paffessor | 3.22 |

| Pakapter | 2.67 |

| Patette | 4.44 |

| Patiker | 3.56 |

| Rauligkeit | 4.67 |

| Robistik | 4.56 |

| Rusine | 4.44 |

| Silument | 3.78 |

| Tackerie | 4.33 |

| Tickerei | 4.89 |

| Tillusion | 3.78 |

| Turade | 4.67 |

Footnotes

Analogy in stress assignment involves relying on similarity in surface forms across words. L2 learners may rely on what they know about how a word with a particular suffix is stressed (e.g., compoˈsition) and apply this stress pattern to new words that they encounter with the same suffix (e.g., dispoˈsition).

It may be the case that participants who rely on analogy are actually making use of a set of lexical stress rules. In the current study we are unable to distinguish between reliance on analogy and reliance on rules.

Bybee’s (2001) Usage-Based Model makes similar predictions.

Lexical familiarity differs from lexical frequency, especially in the case of classroom L2 learners, whose exposure to particular words may differ from that of L1 speakers and of learners who are immersed in the target language.

All participants completed the perceptual task before the production task. As such, the nonsense words were not completely new to them when they completed the production task.

An anonymous reviewer noted that information about the frequency and duration of breaks would be helpful to understand the extent to which participants may have been affected by the tedious nature of the tasks. While we do not have data on the duration of the built-in breaks, participants did take advantage of them. Activities ranged from changing position (i.e., standing up and walking around the lab) to leaving the lab for a short trip to the washroom or water fountain. No participant reported problems with concentration.

When reporting the results of GEE analyses, researchers include the following: EMM (estimated marginal mean from the GEE model), Wald χ2 (a χ2 statistic that provides information about whether or not coefficients are equal to zero, where χ2 = (B/SE)2), B (a parameter estimate), and SE (standard error).

It is possible that the number of analogous words produced by participants was related to their overall vocabulary size, which was not controlled for in the current study. The only related measure is proficiency, and French- and English-speaking German L2 learners did not differ significantly in terms of proficiency.

It may be that the French-speaking German L2 learners in the current study knew fewer German words than the English-speaking German L2 learners; however, since the proficiency levels did not differ, it is unlikely that this is the case.

Contributor Information

Mary Grantham O’Brien, Email: mgobrien@ucalgary.ca.

Ross Sundberg, Email: ross.sundberg@mcgill.ca.

References

- Altmann Heidi. The perception and production of second language stress: A cross-linguistic experimental study . Delaware: University of Delaware; 2006. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- Archibald John. Transfer of L1 parameter settings: Some empirical evidence from Polish metrics. Canadian Journal of Linguistics . 1992;37:301–339. doi: 10.1017/s0008413100019903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald John. The learnability of English metrical parameters by adult Spanish speakers. International Review of Applied Linguistics and Language Teaching . 1993;31(2/3):129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald John. Second language phonology . Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Aske Jon. Disembodied rules versus patterns in the lexicon: Testing the psychological reality of Spanish stress rules. In: Hall Kira, Koenig Jean Pierre, Meacham Michael, Reinman Sondra, Sutton Laurel A., editors. Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society . Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society; 1990. pp. 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bond Zinny S., Small Lary. H. Voicing, vowel, and stress mispronunciations in continuous speech. Perception & Psychophysics . 1983;34(5):470–474. doi: 10.3758/bf03203063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun Bettina, Galts Tobias, Kabak Barış. Lexical encoding of L2 tones: The role of L1 stress, pitch accent and intonation. Second Language Research . 2014;30(3):323–350. doi: 10.1177/0267658313510926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun Bettina, Johnson Elizabeth K. Question or tone 2? How language experience and linguistic function guide attention to pitch. Journal of Phonetics . 2011;39:585–94. doi: 10.1016/j.wocn.2011.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock Barbara E., Lord Gillian. Analogy as a learning tool in second language acquisition: The case of Spanish stress. In: Pérez-Leroux Ana, Roberge Yves., editors. Romance linguistics: Theory and acqsuitision. Selected papers from the 32nd Lingusitic Symposium on Romance Languages . Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins; 2003. pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee Joan. Phonology and language use . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Caspers Joanneke. The influence of erroneous stress position and segmental errors on intelligibility, comprehensibility and foreign accent in Dutch as a second language. Linguistics in the Netherlands . 2010;27:17–29. doi: 10.1075/avt.27.03cas. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers Joanneke, Kepinska Olga. Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences . Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong; 2011. The influence of word-level prosodic structure of the mother tongue on production of word stress in Dutch as a second language; pp. 420–423. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Hsueh Chu. Chinese learners’ acquisition of English word stress and factors affecting stress assignment. Linguistics and Education . 2013;24:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2013.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Wei-Lun, Jarmulowicz Linda. Stress judgment and production in English derivation, and word reading in adult Mandarin-speaking English learners. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research . 2017;46(4):997–1017. doi: 10.1007/s10936-017-9475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Nicole, Cutler Anne, Wales Roger. Constraints of lexical stress on lexical access in English: Evidence from native and non-native listeners. Language and Speech . 2002;45:207–228. doi: 10.1177/00238309020450030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donselaar Wilma van, Koster Mariëtte, Cutler Anne. Exploring the role of lexical stress in lexical recognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology . 2005;58A:251–273. doi: 10.1080/02724980343000927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupoux Emmanuel, Pallier Christophe, Sebastian Núria, Mehler Jacques. A distressing “deafness” in French? Journal of Memory and Language . 1997;36(3):406–421. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1996.2500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dupoux Emmanuel, Sebastián-Gallés Núria, Navarrete Eduardo, Peperkamp Sharon. Persistent stress “deafness”: the case of French learners of Spanish. Cognition . 2008;106:682–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann Peter H. Patterns of stress-transfer in English and German. International Review of Applied Linguistics . 1973;11:299–241. doi: 10.1515/iral.1973.11.1-4.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero Paola. Second-language phonology : The role of perception. In: Pennington M. C., editor. Phonology in context . New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2006. pp. 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Flege James E. Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In: Strange W., editor. Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research . Timonium, MD: York Press; 1995. pp. 233–277. [Google Scholar]

- Fry Dennis B. Experiments in the Perception of Stress. Language and Speech . 1958;1(2):126–152. doi: 10.1177/002383095800100207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goethe Institut Einstufungstest [Placement test] . 2004. [30 October 2006]. http://www.goethe.de/cgi-bin/einstufungstest/einstufungstest.pl

- Guion Susan G. Knowledge of English word stress patterns in early and late Korean-English Bilinguals. Studies in Second Language Acquisition . 2005;27(4):503–533. doi: 10.1017/s0272263105050230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guion Susan G., Clark J. J., Harada Tetsuo, Wayland Ratree P. Factors affecting stress placement for English nonwords include syllabic structure, lexical class, and stress patterns of phonologically similar words. Language and Speech . 2003;46(4):403–427. doi: 10.1177/00238309030460040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Harb Rachel, Masuda Kyoko. Development of the ability to lexically encode novel second language phonemic contrasts. Second Language Research . 2008;24:5–33. doi: 10.1177/0267658307082980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Yeqin, Wang Qiuying, Anderson Richard C. Chinese children’s use of subcharacter information about pronunciation. Journal of Educational Psychology . 2005;97(4):572–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.97.4.572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Candise Y., Wang Min, Isdardi William J., Xu Yi. Stress processing in Mandarin and Korean second language learners of English. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition . 2014;17:316–346. doi: 10.1017/s1366728913000333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lord Gillian. The second language acquisition of Spanish stress: derivational, analogical or lexical? Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University; 2001. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Lord Gillian. The role of the lexicon in learning second language stress patterns. Applied Language Learning . 2007;17(1-2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maczuga Paulina, O’Brien Mary Grantham, Knaus Johannes. Producing lexical stress in second language German. Die Unterrichtspraxis: Teaching German . 2017;50(2):120–135. doi: 10.1111/tger.12037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mairs Jane L. Stress assignment in interlanguage phonology: An analysis of the stress system of Spanish speakers learning English. In: Gass S. M., Schachter J., editors. Linguistic perspectives on second language acquisition . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 260–283. [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa Margaret. Children’s productive recoding. Reading Research Quarterly . 1995;30:464–476. doi: 10.2307/747626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien Mary Grantham. Attending to second language lexical stress: Exploring the roles of metalinguistic awareness and self-assessment. Language Awareness . 2019;28(4):310–328. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2019.1625912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Shan-Chia. Taiwanese EFL Learners’ Perception of English Word Stress. Concentric: Studies in Linguistics . 2010;36(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]