Abstract

Aims

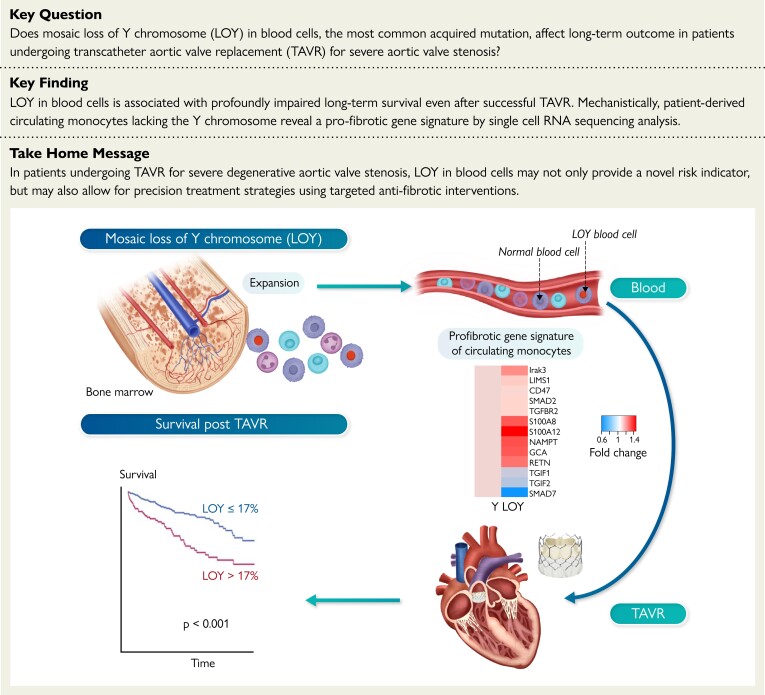

Mosaic loss of Y chromosome (LOY) in blood cells is the most common acquired mutation, increases with age, and is related to cardiovascular disease. Loss of Y chromosome induces cardiac fibrosis in murine experiments mimicking the consequences of aortic valve stenosis, the prototypical age-related disease. Cardiac fibrosis is the major determinant of mortality even after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). It was hypothesized that LOY affects long-term outcome in men undergoing TAVR.

Methods and results

Using digital PCR in DNA of peripheral blood cells, LOY (Y/X ratio) was assessed by targeting a 6 bp sequence difference between AMELX and AMELY genes using TaqMan. The genetic signature of monocytes lacking the Y chromosome was deciphered by scRNAseq. In 362 men with advanced aortic valve stenosis undergoing successful TAVR, LOY ranged from −4% to 83.4%, and was >10% in 48% of patients. Three-year mortality increased with LOY. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed an optimal cut-off of LOY >17% to predict mortality. In multivariate analysis, LOY remained a significant (P < 0.001) independent predictor of death during follow-up. scRNAseq disclosed a pro-fibrotic gene signature with LOY monocytes displaying increased expression of transforming growth factor (TGF) β-associated signaling, while expression of TGFβ-inhibiting pathways was down-regulated.

Conclusion

This is the first study to demonstrate that LOY in blood cells is associated with profoundly impaired long-term survival even after successful TAVR. Mechanistically, the pro-fibrotic gene signature sensitizing the patient-derived circulating LOY monocytes for the TGFβ signaling pathways supports a prominent role of cardiac fibrosis in contributing to the effects of LOY observed in men undergoing TAVR.

Keywords: Aortic valve stenosis, TAVR, Clonal hematopoiesis, Loss of Y chromosome

Structured Graphical Abstract

Structured Graphical Abstract.

Mosaic loss of Y chromosome and mortality post TAVR.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Why Y? The Y chromosome may serve a cardiovascular purpose after all’, by A.M. Small and P. Libby, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad125.

Translational perspective.

Loss of Y chromosome (LOY) in blood cells is associated with increased mortality after successful transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Circulating monocytes with LOY are characterized by a pro-fibrotic gene expression signature sensitizing the cells for the transforming growth factor-β signaling pathways. Thus, the identification of men with increased LOY may not only provide a novel risk indicator but may also allow for precision treatment strategies with a superior response to specific antifibrotic therapies in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis, in whom diffuse cardiac fibrosis is the major determinant of impaired survival following TAVR.

Introduction

Mosaic loss of Y chromosome (LOY) in blood cells, defined as loss of the entire Y chromosome in a mosaic fashion,1 is the most common acquired somatic mutation in human blood cells.2 Loss of Y chromosome increases with age and correlates with clonal expansion of myeloid cells.3,4 In epidemiological studies, LOY has been linked to shorter life expectations in elderly men as well as with a variety of age-associated diseases including cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, macular degeneration, and cardiovascular diseases.1,3,5–7 Most recently, Sano et al.8 experimentally demonstrated that hematopoietic loss of Y chromosome in mice led to cardiac fibrosis during aging, particularly after left ventricular pressure overload due to aortic constriction, which mimics the consequences of aortic valve stenosis. The study by Sano et al.8 for the first time disclosed a causal relationship for LOY with cardiac disease.9

Since degenerative aortic valve stenosis is the prototypical age-related cardiovascular disease10 and diffuse cardiac fibrosis is the major independent determinant of impaired survival even after successful aortic valve replacement,11 we investigated the effects of LOY in blood cells on long-term outcome in male patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Methods

Study cohort

A total of 362 male patients with severe aortic valve stenosis undergoing successful TAVR between February 2017 and August 2021 at the University Hospital of the Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany, were included in the current study. All participants provided written informed consent for the study procedures, including the intervention and genetic testing using blood samples. This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee (protocol number 187/17), and the study complied with the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study procedures

Clinical, echocardiographic, and laboratory data were collected both at baseline and in a prospective up to 3-year follow-up. Baseline risk was estimated using EuroSCORE II. Preprocedural inflammatory parameters [including high-sensitive C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels and white blood cell counts], as well as troponin T and high-sensitive N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) were measured. Long-term (up to 3 years) all-cause mortality was the primary outcome.

Measurement of LOY

Estimation of LOY was performed using a previously validated digital PCR technique.4 In brief, the TaqMan-based method quantifies the relative number of X and Y chromosomes in a DNA sample by targeting a 6 bp sequence difference present between the AMELX and AMELY genes using the same primer pair and, thus, is relatively unbiased with regard to primer properties. DNA was extracted from whole blood of patients obtained at the time of TAVR prior to beginning the procedure.

One hundred and fifty nanograms of DNA was mixed with Probe PCR Master Mix (QIAcuity Probe PCR Kit, #250101, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) containing FastDigest HindIII enzyme (#FD0504, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and TaqMan Primers (#C_990000001_10, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After digestion for 10 min at room temperature, a 26k 24-well Nanoplate (QIAcuity Nanoplate 26k 24-well, #250001, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was filled with the reaction mix and loaded into a QIAcuity One instrument (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR cycling was performed following manufacturer’s instructions: PCR initial heat activation 95°C for 2 min, followed by two-step cycling (40 cycles) of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s. A 6 nt deletion occurs in the X-specific amelogenin gene (B37/hg19 genome locations: chrX:11315039 and chrY:6 737 949–6 737 954). The VIC dye probe detects X-chromosome sequences, and the FAM dye probe includes the 6nt and detects Y-chromosome sequences (Sequence: GTGTTGATTCTTTATCCCAGATG[-/AAGTGG]TTTCTCAAGTGGTCCTGATTTT [VIC/FAM]).

The endpoint fluorescence intensity of the partitions was separately measured for FAM (targeting AMELY) and VIC (targeting AMELX) to determine the presence or absence of the respective targets. Using the QIAcuity One Software Suite (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) the absolute concentration of the targets was calculated based on the number of positive and negative partitions. The ratio of AMELY/AMELX was calculated using absolute concentrations. Extent of LOY was defined as percent of cells with LOY derived from the ratio AMELY/AMELX.

Sequencing for DNMT3A and TET2-mediated clonal hematopoiesis

The presence of somatic DNMT3A or TET2 CHIP-driver mutations with a variant allele frequency (VAF) ≥ 2% was assessed in 345 patients because of the exclusion of 17 patients (3 due to missing data on CHIP-driver mutation status and 14 due to hematological disorders that made CHIP definition inapplicable). NGS was performed by MLLDxGmbH, München, Germany, as previously described.12 In brief, DNA was isolated with the MagNaPure System (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) from mononuclear cells after lysis of erythrocytes. The patients’ libraries were generated with the Nextera Flex for enrichment kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequences for DNMT3A and TET2 enriched with the IDT xGen hybridisation capture of DNA libraries protocol and customised probes (IDT, Coralville, IA). The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with a mean coverage of 2147 × and a minimum coverage of 400×, reaching a sensitivity of 2%. Reads were mapped to the reference genome (UCSC hg19) using Isaac aligner (v2.10.12) and a small somatic variant calling was performed with Pisces (v5.1.3.60). Protein truncating variants were classified as mutation. Non-synonymous changes were included, if they were well annotated (several definite submissions to COSMIC, IRAC or ClinVAR). Other non-protein truncating variants were defined as variants of uncertain significance (VUS).

Single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) analyses

ScRNAseq was performed as previously described.13 In brief, patient-derived blood was centrifuged on density gradient centrifugation (Pancoll human, Density: 1.077 g/mL, #P04-60500, PAN-Biotech GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany), and mononuclear cells were used for droplet scRNAseq using the Chromium Controller with Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3′ GEM, Library and Gel Bead Kit version 3.1 reagent (10 × Genomics, Pleasanton, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were sequenced using paired-end sequencing by GenomeScan (Leiden, Netherlands), and expression data were processed by the Cell Ranger Single Cell Software Suite version 3 (10 × Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) and aligned to the human reference genome GRCh38. Data integration was performed by Seurat version (v4.0.3) (Satija Lab, New York Genome Center, New York City, NY, USA), and FindMarkers function in the Seurat package was used for statistical analysis of differential gene expression. Loss of Y chromosome cells were defined in scRNAseq data as combinatorial lack of expression of all Y chromosome derived genes. Relative changes in transcription of Y harboring and LOY cells were then assessed and data were pooled for the seven male patients analyzed in the present study.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and frequencies (%), and continuous variables as median [interquartile range (IQR)] unless otherwise noted. Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used, as appropriate, for comparison of categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared between groups by the Mann–Whitney test. Best cut-off value for extent of LOY in predicting mortality was calculated using the Youden index14 based on the area under the curve (AUC) from a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. For mortality analysis, LOY data were dichotomized according to the cut-off value to define the groups of patients with high vs. low LOY. Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted and univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to compare mortality. All covariables reaching a P-value <0.1 in univariate analysis as well as previously established predictors of outcome after TAVR were included in multivariate analysis to adjust for potential confounding effects. An additional analysis of mortality was performed after excluding those patients who died within the first 30 days after the procedure, as a way to rule out a potential effect of periprocedural complications. All analyses were performed with SPSS statistical package, version 29.0. P-value for significance was set at 0.05. ScRNAseq analysis was performed by using R (version 4.0.3) and the analysis tool Seurat (v4.0.3). In brief, differential expression of genes was used utilizing the ‘FindMarkers’ function in the Seurat package for focused analyses. Significant comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test followed by Bonferroni correction. Significance was reported if adjusted P < 0.05. Differential transcriptional profiles by LOY status were generated in Seurat with associated gene ontology terms derived from the functional annotation tool Metascape (v3.5) for further analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics and prognostic significance of LOY

The clinical characteristics and laboratory values at baseline prior to TAVR of the patients are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. No differences were observed between patients with high or low LOY value in baseline variables, including inflammatory parameters, except for age as expected (P = 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in patients according to dichotomized Y/X ratio

| Total (n = 362) | LOY ≤17% (n = 255) | LOY >17% (n = 107) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available | |||

| Male sex | 362 | 255 (100.00) | 107 (100.00) |

| Age (years) | 362 | 81 (77–85) | 83 (80–85) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 362 | 26.57 (24.55–29.71) | 25.88 (24.14–28.25) |

| CVD | 362 | 61 (23.92) | 21 (19.63) |

| PAOD | 362 | 37 (14.51) | 18 (16.82) |

| Prior heart surgery | 362 | 39 (15.29) | 12 (11.21) |

| COPD | 361 | 41 (16.08) | 17 (15.89) |

| Diabetes | 362 | 85 (33.33) | 28 (26.17) |

| Hypertension | 362 | 209 (81.96) | 82 (76.64) |

| NYHA class | 362 | ||

| ȃI | 6 (2.35) | 0 (0.00) | |

| ȃII | 52 (20.39) | 21 (19.63) | |

| ȃIII | 179 (70.20) | 79 (73.83) | |

| ȃIV | 18 (7.06) | 7 (6.54) | |

| MI | 362 | 57 (22.35) | 21 (19.63) |

| Stroke | 362 | 33 (12.94) | 10 (9.35) |

| TIA | 362 | 8 (3.14) | 4 (3.74) |

| PCI | 362 | 121 (47.45) | 48 (44.86) |

| CAD | 362 | ||

| ȃ0 | 75 (29.41) | 30 (28.04) | |

| ȃ1 | 66 (25.88) | 25 (23.36) | |

| ȃ2 | 44 (17.25) | 18 (16.82) | |

| ȃ3 | 70 (27.45) | 34 (31.78) | |

| ȃPPM | 362 | 39 (15.29) | 17 (15.89) |

| ȃAF | 362 | 98 (38.43) | 52 (48.60) |

| ȃLVEF (%) | 355 | 55 (40–60) | 55 (40–60) |

| EuroSCORE II | 362 | 3.66 (2.04–6.26) | 3.66 (2.10–6.83) |

| DNMT3A/TET2-CHIP | 345 | 73 (30.3) | 28 (26.9) |

Values are given as n (%), or median (interquartile range).

AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHIP, clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusive disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPM, permanent pacemaker implantation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters in patients according to dichotomized Y/X ratio

| Total 362 | LOY ≤17% (n = 255) | LOY >17% (n = 107) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available | |||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 362 | 59.90 (45.95–74.00) | 58.50 (43.00–75.00) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 362 | 12.60 (10.95–13.90) | 12.40 (10.80–13.76) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 361 | 37.10 (33.10–40.70) | 36.45 (32.83–40.30) |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 312 | 5.40 (3.30–10.30) | 6.10 (3.70–10.85) |

| Leukocytes (/nL) | 361 | 7.01 (5.87–8.42) | 6.94 (5.73–8.19) |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 308 | 1856 (526–4393) | 1708 (809–4865) |

| Troponin (pg/mL) | 303 | 27 (17–49) | 27 (15–44) |

| CK (U/L) | 328 | 81 (55–120) | 72 (52–116) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 329 | 0.28 (0.11–0.76) | 0.22 (0.09–0.84) |

Values are given as median (interquartile range).

CK, creatinine kinase; CRP, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IL-6, Interleukin-6; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide.

Patients had a median age of 81.7 (77.8–84.8) years. The extent of LOY in blood cells ranged from −4% to 83.4% (median 8.8%) and was >10% in 48% of patients.

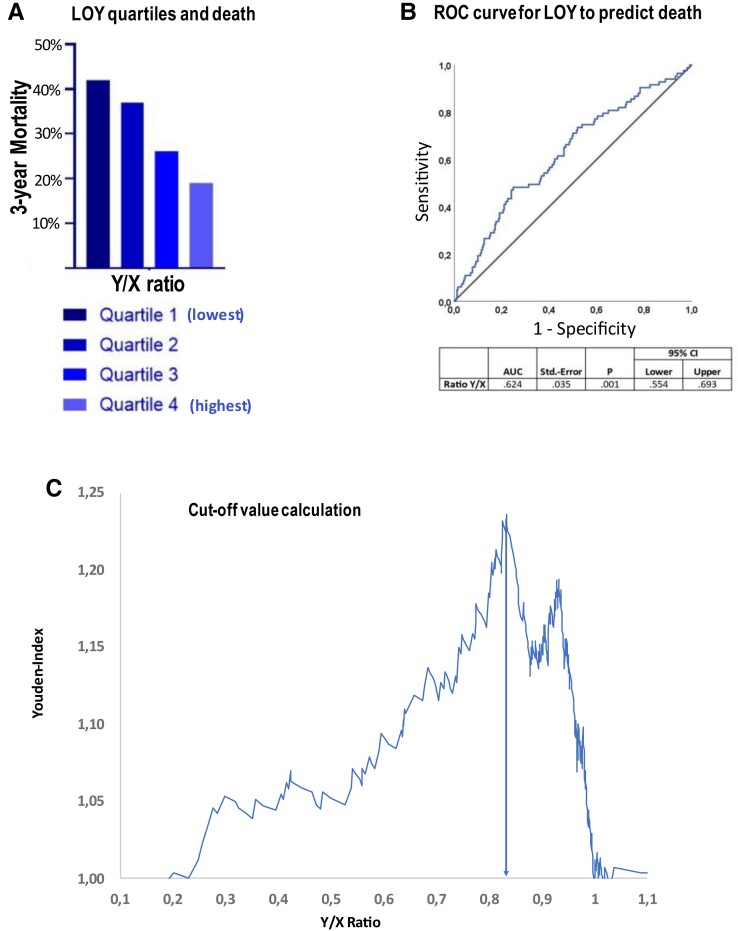

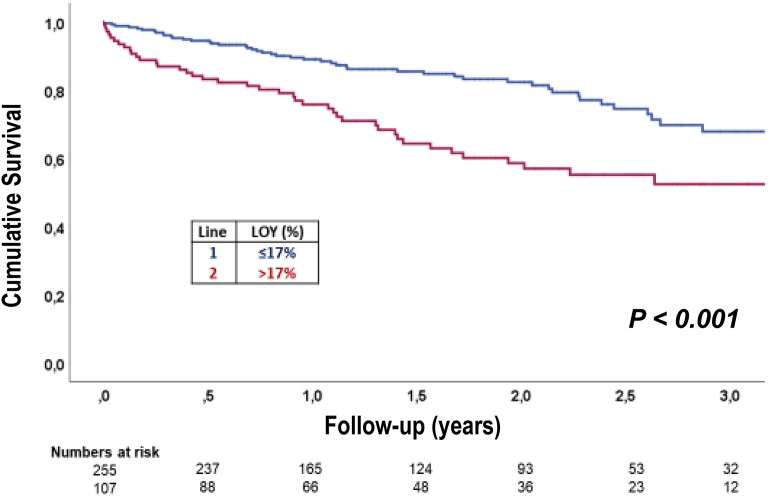

During 3 years of follow-up, 88 patients died. Dividing the extent of LOY into quartiles demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in mortality with increasing extent of LOY (Figure 1A). Using the Youden index derived from the ROC curves relating LOY to mortality revealed a LOY of 17% as the optimal cut-off value to predict mortality during follow-up (Figure 1B). A total of 107 (=29%) patients had LOY in more than 17% of their circulating blood cells. As summarized in Tables 1 and 2, patients harboring > 17% LOY were slightly older but otherwise did not differ with respect to clinical characteristics or laboratory parameters at the time of TAVR. Figure 2 illustrates the Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with LOY > 17% compared with those with 17% or less LOY in blood cells. Patients with LOY exceeding 17% had a significantly (P < 0.001) worse clinical outcome for death with continuously diverging survival curves up to 3 years of follow-up (Figure 2). Results remained significant (P < 0.005) when using a 30-day blanking period (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1).

Figure 1.

(A) Mortality according to LOY quartiles, (B) ROC curve for LOY to predict death, (C) the cut-off value of 17% is derived from the optimal Youden index based on the ROC curve.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves in patients above and below LOY cut-off value.

In order to assess whether the increase in mortality may be confounded by the presence of concomitant risk factors for worse outcome, multivariate analyses were performed including age as well as previously established prognostic factors after TAVR. As summarized in Table 3, LOY > 17% remained an independent predictor with a hazard ratio of 2.2 (1.4–3.4) for mortality after TAVR in addition to the presence of anemia and an elevated EuroSCORE II.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis for long-term all-cause mortality

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| LOY >17% | 2.195. (1.444–3.337) | 0.000 | 2.079 (1.362–3.173) | 0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.042 (1.021–1.063) | 0.000 | 1.022 (0.992–1.050) | 0.151 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.981 (0.971–0.991) | 0.000 | 0.982 (0.973–0.992) | 0.001 |

| NYHA class | 1.974 (1.317–2.959) | 0.001 | 1.656 (1.107–2.478) | 0.014 |

| Anemia | 2.294 (1.059–4.965) | 0.035 | 2.942 (1.804–4.797) | 0.000 |

| Previous PCI | 0.602 (0.358–1.011) | 0.055 | 0.680 (0.404–1.145) | 0.147 |

| CAD | 1.221 (0.989–1.506) | 0.063 | 1.092 (0.914–1.304) | 0.331 |

| Hypertension | 0.639 (0.390–1.049) | 0.076 | 0.612 (0.376–0.998) | 0.049 |

| Age | 1.033 (0.994–1.074) | 0.099 | 1.004 (0.970–1.039) | 0.835 |

| PPM | 1.537 (0.911–2.592) | 0.107 | ||

| AF | 1.369 (0.883–2.122) | 0.160 | ||

| BMI | 0.964 (0.915–1.016) | 0.170 | ||

| COPD | 1.360 (0.824–2.245) | 0.229 | ||

| Previous TIA | 0.530 (0.128–2.189) | 0.380 | ||

| Previous stroke | 1.222 (0.654–2.281) | 0.530 | ||

| CVD | 0.846 (0.498–1.436) | 0.536 | ||

| Platelets (/nL) | 0.999 (0.996–1.002) | 0.536 | ||

| Leukocytes (/n) | 1.018 (0.948–1.094) | 0.617 | ||

| Hematocrit (%) | 0.959 (0.895–1.028) | 0.240 | ||

| PAOD | 0.885 (0.470–1.665) | 0.704 | ||

| Previous MI | 1.086 (0.631–1.869) | 0.765 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.964 (0.611–1.521) | 0.875 | ||

AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusive disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPM, permanent pacemaker implantation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Anemia was defined according to WHO criteria as < 13 g/dL in male patients and < 12 g/dL in female patients. Loss of Y chromosome (Y/X) ratio and anemia were used as dichotomised variables. Age, Euroscore II and laboratory parameters were used as continuous variables. All clinically relevant variables and laboratory parameters were included in univariate analyses, except those already included in EuroSCORE II (i.e. sex, left ventricular ejection fraction) to avoid dual inclusion. For multivariate analysis, those covariables reaching a P-value <0.1 in univariate analyses were included.

Taken together, these data establish LOY as a significant independent predictor of long-term mortality in patients undergoing TAVR for severe aortic valve stenosis.

Association between LOY and clonal hematopoiesis

As previous small studies reported the co-occurrence of LOY in blood cells with clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) and we have shown that the most prevalent CHIP-driver mutations in the DNMT3A and TET2 gene associate with poor outcome post-TAVR,12 we investigated a potential interaction of LOY and CHIP in the present study. CHIP-driver mutations with a variant allele frequency > 2% in the DNMT3A or TET2 gene were observed in 101 of the 345 patients (29%) tested for CHIP in the present cohort. The prevalence of DNMT3A/TET2 CHIP-driver mutations did not differ between patients with LOY > 17% compared with those with LOY of 17% or less (Table 1). Moreover, 3-year mortality rates did not differ between patients harboring both, LOY > 17% as well as DNMT3A/TET2 mutations (mortality 35.8%), compared with patients only showing LOY > 17% without co-occurrence of DNMT3A/TET2 CHIP-driver mutations (mortality 38.8%). However, it should be noted that only 28 patients had co-occurrence of LOY > 17% and DNMT3A/TET2 CHIP-driver mutations with a VAF > 2%. Thus, the co-occurrence of CHIP and LOY does not seem to interfere with the increased mortality observed in patients with an extent of LOY exceeding 17%.

Potential mechanistic insights into increased mortality by LOY

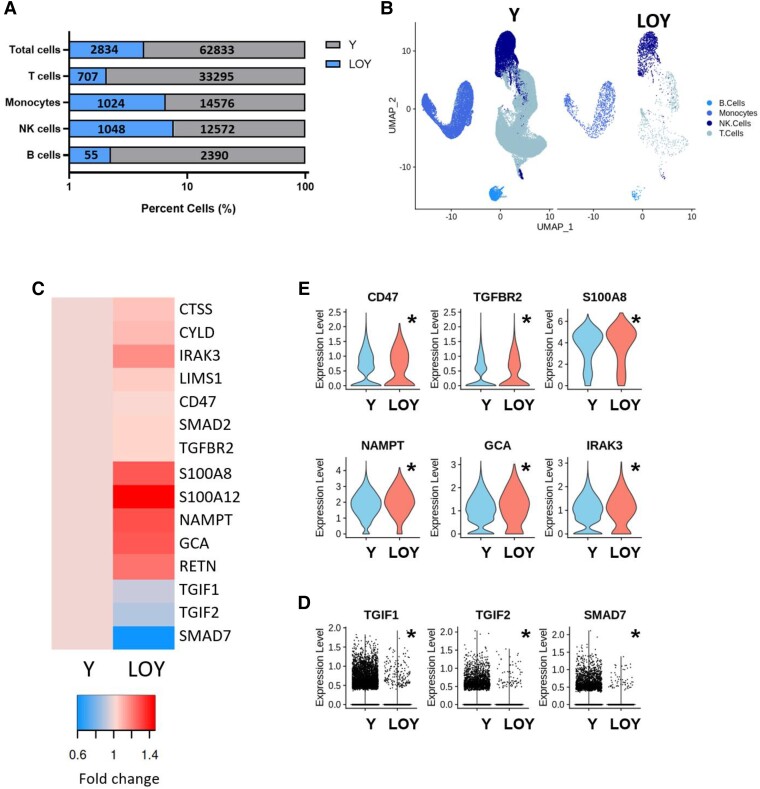

ScRNAseq provides a unique and powerful method to decipher the transcriptional signatures of individual cells in an unbiased manner and is capable to reveal differential gene expression patterns in patient-derived peripheral blood cells lacking the Y chromosome. Therefore, we performed scRNAseq analyses of circulating peripheral monocytic blood cells in seven patients of the present cohort. Cells lacking the Y chromosome were identified by the absence of expression of all genes encoded on the Y chromosome, and their gene signatures were compared with cells expressing Y chromosome-associated genes. As illustrated in Figure 3A and B, cells lacking the expression of Y chromosome-encoded genes were relatively enriched in the monocyte and natural killer (NK) cell cluster. Focusing on significantly regulated genes taken from GO terms implicated in fibrotic signaling, the gene expression heat map shown in Figure 3C demonstrates pronounced pro-fibrotic gene signature in monocytes lacking Y chromosome associated genes. Importantly, as illustrated in Figure 3D, expression of the thymine-guanine-interacting factors 1 and 2 (TGIF1/2), which are potent transcriptional repressors of the transforming growth factor (TGF) β/Smad pathway, as well as of Smad 7 itself, which restrains TGFβ-induced activation, is profoundly down-regulated in LOY cells suggesting sensitizing of these cells to the prototypical pro-fibrotic TGFβ/Smad pathway. Moreover, as illustrated in the violin plots in Figure 3E, expression of the TGFβ receptor 2 as well as the TGFβ-dependent expression of IRAK-3, which drives an alternatively activated profibrotic macrophage phenotype,15 are significantly up-regulated in LOY monocytes further supporting an enhanced sensitization towards pro-fibrotic signaling upon LOY in circulating monocytes.

Figure 3.

Single cell RNA sequencing analysis of LOY cell type distribution and gene signatures in patient-derived monocytes (pooled data from seven patients). (A) Percent of LOY and Y chromosome harboring cells by immune cell class with absolute cell counts labelled within bars. (B) UMAP of monocytes harboring Y chromosome and LOY monocytes. (C) Heatmap of the expression of regulated genes associated with fibrosis and TGFβ signaling within the monocyte population. (D) Expression of down-regulated genes in individual monocytes associated with TGFβ inhibition. (E) Violin plots of expression of up-regulated genes associated with fibrosis and TGFβ signaling within the monocyte population. Significant comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test followed by Bonferroni correction. Significance was reported if adjusted P < 0.05 and indicated with asterisk (*).

Taken together, the sensitization of LOY monocytes towards TGFβ signaling pathways may contribute to an enhanced cardiac fibrosis upon recruitment of the monocytes to the cardiac tissue and, thus, aggravate disease progression in patients with aortic stenosis even after removal of the stenotic valve by TAVR.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the occurrence and prognostic significance of LOY in blood cells in patients with severe degenerative aortic valve stenosis. Our results demonstrate that LOY occurs frequently in this patient population with advanced age and is associated with a significant increase in mortality, even after successful correction of aortic valve stenosis by TAVR. Mechanistically, our scRNAseq analyses reveal a pro-fibrotic gene signature with enhanced TGFβ signaling pathways in patient-derived circulating monocytes lacking the Y chromosome (Structured Graphical Abstract), thus extending very recent experimental observations in humans.

This study advances the finding that LOY may be a biological marker linked to age-dependent chronic diseases. In fact, LOY in at least 10% of peripheral blood cells was present in 48% of this elderly population, which is in line with previous reports in the general population.2–4 Thus, LOY occurs frequently in patients undergoing TAVR. Increasing extent of LOY was associated with increased mortality suggesting a dose-dependent effect. Using an optimal threshold of > 17% of circulating blood cells lacking the Y chromosome documented that LOY is an independent predictor of increased mortality even after successful TAVR. These data considerably extend previous epidemiological studies using large data sets from the UK Biobank showing that LOY not only associates with reduced life expectancy but also with mortality due to hypertensive heart disease and heart failure, when a threshold of 40% of LOY in leukocytes was used.8 Importantly, neither clinical characteristics nor serum biomarkers for inflammation or cardiovascular outcome (troponin, NT-proBNP) were different between patients above or below the cut-off value of LOY. Thus, LOY in blood cells may provide a novel risk indicator for patients undergoing TAVR for severe degenerative aortic valve stenosis.

Mechanistically, very recent experimental data in mice demonstrated that modelling LOY in bone marrow cells was associated with a pro-fibrotic/TGFβ-associated polarization of bone marrow-derived cardiac macrophages lacking the Y chromosome leading to cardiac fibroblast activation, excessive matrix production, and cardiac fibrosis. Enhanced fibrosis was specifically notable in this study following transaortic constriction experimentally mimicking aortic valve stenosis.8 Single cell RNA sequencing analyses of patient-derived circulating blood cells provide a unique method to differentiate the genetic signature of Y chromosome lacking vs. Y chromosome-harboring cells even in an individual patient. Here, for the first time, we document that LOY in circulating monocytes from patients undergoing TAVR is associated with a pro-fibrotic gene signature characterized by sensitizing the cells for the TGFβ signaling pathways. These data not only extend the experimental studies in mice supporting a causal role for LOY in hematopoietic cells for cardiac fibrosis but may also offer a rational explanation for the increased mortality observed in patients with LOY even after successful TAVR. As diffuse cardiac fibrosis is the major determinant of increased mortality after aortic valve replacement11 and circulating monocytes infiltrating the heart and differentiating to macrophages instigate cardiac fibrotic processes via TGFβ,16 recruitment of circulating monocytes primed for activation of pro-fibrotic processes into cardiac tissue may contribute to the observed increased mortality. Both, experimental studies and clinical investigations in sex-mismatched heart transplant patients previously demonstrated that upon hemodynamic stress, such as present in severe aortic valve stenosis, cardiac macrophages are maintained through circulating monocyte recruitment and proliferation and cardiac macrophage abundance is associated with adverse left ventricular remodeling and impaired systolic function.17 Importantly, in view of recent efforts to apply specific antifibrotic therapies in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,18 the identification of men with increased LOY may also provide for precision treatment strategies with a superior response to antifibrotic therapies in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis, where impaired diastolic function due to profound left ventricular hypertrophy frequently persists even after TAVR.

Mosaic LOY shows some similarities to CHIP, which is defined as the accumulation of acquired mutations in genes commonly associated with myeloid neoplasms in the peripheral blood of individuals without hematological malignancy.19 Like LOY, CHIP increases with age and was shown to associate with cardiovascular diseases.20–24 Indeed, some small studies recently reported the co-occurrence of CHIP and LOY,25,26 thereby raising the question whether LOY and CHIP may represent two sides of the same coin.25 Since we previously demonstrated that CHIP also confers a worse prognosis in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR,12 we addressed a potential interaction between CHIP and LOY in the present study. However, at least for the most prevalent CHIP-driver mutations in the DNMT3A and/or TET2 gene, we did neither find an increased prevalence of CHIP in patients with increased LOY nor did the co-occurrence of LOY and CHIP in an individual patient aggravate mortality after TAVR. However, it should be noted that the number of patients simultaneously carrying a DNMT3A/TET2 CHIP-driver mutation and harboring LOY >17% in the present study is rather small, thus precluding firm conclusions regarding potential interactions between CHIP and LOY in cardiovascular disease.

Limitations

The most important limitation of the present study refers to the fact that this clinical study cannot provide a cause-and-effect relationship between the profibrotic gene signature of circulating LOY monocytes and increased mortality of patients harboring LOY > 17%. Unfortunately, the precise cause of death could not be reliably determined in the majority of these elderly patients. Therefore, our present analysis did focus on all-cause mortality rather than cardiovascular mortality. Moreover, establishing a direct association between the extent of LOY in circulating monocytes and diffuse cardiac fibrosis would require either cardiac MRI or myocardial biopsy specimens obtained from the patients undergoing TAVR in order to quantitate the extent of cardiac fibrosis, which was not available to us. Thus, further studies applying cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to quantify the extent of diffuse myocardial fibrosis should be prospectively performed in patients undergoing TAVR to provide further pathophysiological insights into the relation between cardiac fibrosis and LOY in circulating immune cells.

Conclusions

Our data support the hypothesis that LOY in blood cells may be associated with impaired survival even after successful valve replacement by TAVR via enhanced pro-fibrotic activity of circulating monocytes. Future studies will have to validate our findings in larger cohorts and test whether a targeted anti-fibrotic therapy may be a valuable treatment strategy in patients with increased LOY undergoing TAVR for severe aortic valve stenosis.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at European Heart Journal online.

Pre-registered clinical trial number

None supplied.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Frankfurt (protocol number 187/17).

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Silvia Mas-Peiro, Department of Medicine, Cardiology, Goethe University Hospital, Frankfurt, Germany; German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) Partner Site RheinMain, Frankfurt, Germany; Cardiopulmonary Institute, Frankfurt, Germany.

Wesley T Abplanalp, German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) Partner Site RheinMain, Frankfurt, Germany; Cardiopulmonary Institute, Frankfurt, Germany; Institute for Cardiovascular Regeneration, Goethe University Frankfurt, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany.

Tina Rasper, Institute for Cardiovascular Regeneration, Goethe University Frankfurt, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany.

Alexander Berkowitsch, Institute for Cardiovascular Regeneration, Goethe University Frankfurt, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany.

David M Leistner, Department of Medicine, Cardiology, Goethe University Hospital, Frankfurt, Germany.

Stefanie Dimmeler, German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) Partner Site RheinMain, Frankfurt, Germany; Cardiopulmonary Institute, Frankfurt, Germany; Institute for Cardiovascular Regeneration, Goethe University Frankfurt, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany.

Andreas M Zeiher, German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) Partner Site RheinMain, Frankfurt, Germany; Cardiopulmonary Institute, Frankfurt, Germany; Institute for Cardiovascular Regeneration, Goethe University Frankfurt, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany.

Data availability

Data are available on request.

Funding

The study was co-funded by the European Union (ERC-2021-ADG, GAP—101054899, CHIP AVS to A.M.Z). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. S.D. received support by the German Research Foundation (Exc2026-1), Dr. Rolf M. Schwiete Stiftung (Projekt 08/2018), and the project ENABLE funded by the Hessian Ministry for Science and the Arts. S.M.-P. received support by a Cardiopulmonary Institute (CPI) Excellence Cluster Start-up Grant and a Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) Postdoc Start-up Grant.

References

- 1. Forsberg LA, Gisselsson D, Dumanski JP. Mosaicism in health and disease—clones picking up speed. Nat Rev Genet 2017;18:128–142. 10.1038/nrg.2016.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson DJ, Genovese G, Halvardson J, Ulirsch JC, Wright DJ, Terao C, et al. . Genetic predisposition to mosaic Y chromosome loss in blood. Nature 2019;575:652–657. 10.1038/s41586-019-1765-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forsberg LA, Rasi C, Malmqvist N, Davies H, Pasupulati S, Pakalapati G, et al. . Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in peripheral blood is associated with shorter survival and higher risk of cancer. Nat Genet 2014;46:624–628. 10.1038/ng.2966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Danielsson M, Halvardson J, Davies H, Torabi Moghadam B, Mattisson J, Rychlicka-Buniowska E, et al. . Longitudinal changes in the frequency of mosaic chromosome Y loss in peripheral blood cells of aging men varies profoundly between individuals. Eur J Hum Genet 2020;28:349–357. 10.1038/s41431-019-0533-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dumanski JP, Lambert JC, Rasi C, Giedraitis V, Davies H, Grenier-Boley B, et al. . Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in blood is associated with Alzheimer disease. Am J Hum Genet 2016;98:1208–1219. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grassmann F, Kiel C, den Hollander AI, Weeks DE, Lotery A, Cipriani V, et al. . Y chromosome mosaicism is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Eur J Hum Genet 2019;27:36–41. 10.1038/s41431-018-0238-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Loftfield E, Zhou W, Graubard BI, Yeager M, Chanock SJ, Freedman ND, et al. . Predictors of mosaic chromosome Y loss and associations with mortality in the UK biobank. Sci Rep 2018;8:12316. 10.1038/s41598-018-30759-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sano S, Horitani K, Ogawa H, Halvardson J, Chavkin NW, Wang Y, et al. . Hematopoietic loss of Y chromosome leads to cardiac fibrosis and heart failure mortality. Science 2022;377:292–297. 10.1126/science.abn3100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zeiher A, Braun T. Mosaic loss of Y chromosome during aging. Science 2022;377:266–267. 10.1126/science.add0839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonow RO, Greenland P. Population-wide trends in aortic stenosis incidence and outcomes. Circulation 2015;131:969–971. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.014846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Musa TA, Treibel TA, Vassiliou VS, Captur G, Singh A, Chin C, et al. . Myocardial scar and mortality in severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2018;138:1935–1947. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mas-Peiro S, Hoffmann J, Fichtlscherer S, Dorsheimer L, Rieger MA, Dimmeler S, et al. . Clonal haematopoiesis in patients with degenerative aortic valve stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J 2020;41:933–939. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zeiher AM, Abplanalp WT, Mas-Peiro S, Cremer S, John D, Dimmeler S, et al. . Association of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential with inflammatory gene expression in patients with severe degenerative aortic valve stenosis or chronic postischemic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:1170–1175. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fluss R, Faraggi D, Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden Index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J 2005;47:458–472. 10.1002/bimj.200410135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steiger S, Kumar SV, Honarpisheh M, Lorenz G, Günthner R, Romoli S, et al. . Immunomodulatory molecule IRAK-M balances macrophage polarization and determines macrophage responses during renal fibrosis. J Immunol 2017;199:1440–1452. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paulus WJ. Unfolding discoveries in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2020;382:679–682. 10.1056/NEJMcibr1913825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rhee AJ, Lavine KJ. New approaches to target inflammation in heart failure: harnessing insights from studies of immune cell diversity. Annu Rev Physiol 2020;82:1–20. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021119-034412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lewis GA, Dodd S, Clayton D, Bedson E, Eccleson H, Schelbert EB, et al. . Pirfenidone in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med 2021;27:1477–1482. 10.1038/s41591-021-01452-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, Lindsley RC, Sekeres MA, Hasserjian RP, et al. . Perspectives clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2015;126:9–16. 10.1182/blood-2015-03-631747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, Manning A, Grauman PV, Mar BG, et al. . Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2488–2498. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, Gibson CJ, Bick AG, Shvartz E, et al. . Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:111–121. 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dorsheimer L, Assmus B, Rasper T, Ortmann CA, Ecke A, Abou-El-Ardat K, et al. . Association of mutations contributing to clonal hematopoiesis with prognosis in chronic ischemic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:25–33. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Assmus B, Cremer S, Kirschbaum K, Culmann D, Kiefer K, Dorsheimer L, et al. . Clonal haematopoiesis in chronic ischaemic heart failure: prognostic role of clone size for DNMT3A—and TET2 -driver gene mutations. Eur Heart J 2021;42:257–265. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cremer S, Kirschbaum K, Berkowitsch A, John D, Kiefer K, Dorsheimer L, et al. . Multiple somatic mutations for clonal hematopoiesis are associated with increased mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circ Genomic Precis Med 2020;13:E003003. 10.1161/CIRCGEN.120.003003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ljungström V, Mattisson J, Halvardson J, Pandzic T, Davies H, Rychlicka-Buniowska E, et al. . Loss of Y and clonal hematopoiesis in blood-two sides of the same coin? Leukemia 2022;36:889–891. 10.1038/s41375-021-01456-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ouseph MM, Hasserjian RP, Dal Cin P, Lovitch SB, Steensma DP, Nardi V, et al. . Genomic alterations in patients with somatic loss of the Y chromosome as the sole cytogenetic finding in bone marrow cells. Haematologica 2021;106:555–564. 10.3324/haematol.2019.240689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.