Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is a lethal disease notoriously resistant to therapy1,2. This is mediated in part by a complex tumour microenvironment3, low vascularity4, and metabolic aberrations5,6. Although altered metabolism drives tumour progression, the spectrum of metabolites used as nutrients by PDA remains largely unknown. Here we identified uridine as a fuel for PDA in glucose-deprived conditions by assessing how more than 175 metabolites impacted metabolic activity in 21 pancreatic cell lines under nutrient restriction. Uridine utilization strongly correlated with the expression of uridine phosphorylase 1 (UPP1), which we demonstrate liberates uridine-derived ribose to fuel central carbon metabolism and thereby support redox balance, survival and proliferation in glucose-restricted PDA cells. In PDA, UPP1 is regulated by KRAS–MAPK signalling and is augmented by nutrient restriction. Consistently, tumours expressed high UPP1 compared with non-tumoural tissues, and UPP1 expression correlated with poor survival in cohorts of patients with PDA. Uridine is available in the tumour microenvironment, and we demonstrated that uridine-derived ribose is actively catabolized in tumours. Finally, UPP1 deletion restricted the ability of PDA cells to use uridine and blunted tumour growth in immunocompetent mouse models. Our data identify uridine utilization as an important compensatory metabolic process in nutrient-deprived PDA cells, suggesting a novel metabolic axis for PDA therapy.

Subject terms: Cancer metabolism, Pancreatic cancer, Metabolomics

A metabolite screen of pancreatic cells shows that pancreatic cancer cells metabolize uridine-derived ribose via UPP1, supporting redox balance, survival and proliferation.

Main

PDA remains one of the deadliest cancers1,2. The PDA tumour microenvironment (TME) is a major contributor to this lethality, and is characterized by abundant immune cell infiltration, expansion of stromal fibroblasts and the associated deposition of extracellular matrix. This leads to an increase in interstitial fluid pressure and the collapse of arterioles and capillaries3,4,7. These phenomena collectively contribute to low oxygen saturation, therapeutic resistance, metabolic alterations, and heterogeneity within the tumour at the cellular level5,8,9. PDA cells surviving in such nutrient and oxygen deregulated TME exhibit metabolic adaptations that increase their scavenging and catabolic capabilities10–13. In addition, recent studies have defined tumour-extrinsic nutrient sources for PDA, including extracellular matrix, immune, and stromal-derived metabolites14–16. While these studies uncovered discrete nutrient inputs, comprehensive screens with the power to identify many such nutrient drivers and mechanisms have not been performed previously.

Nutrient-deprived PDA consumes uridine

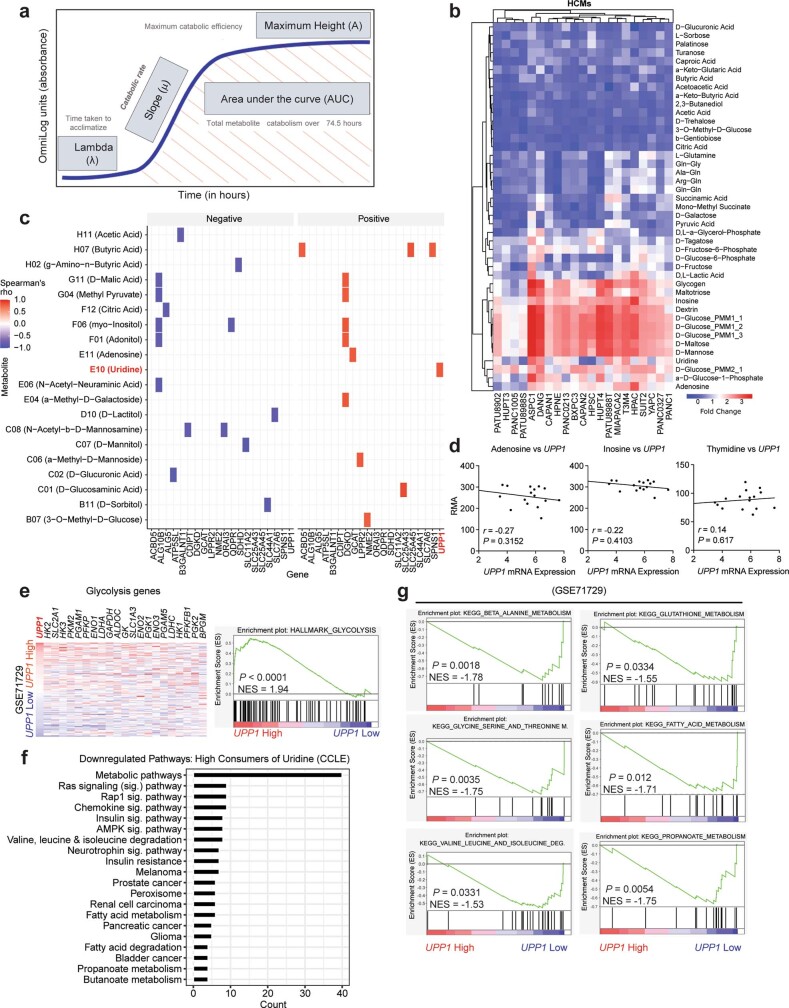

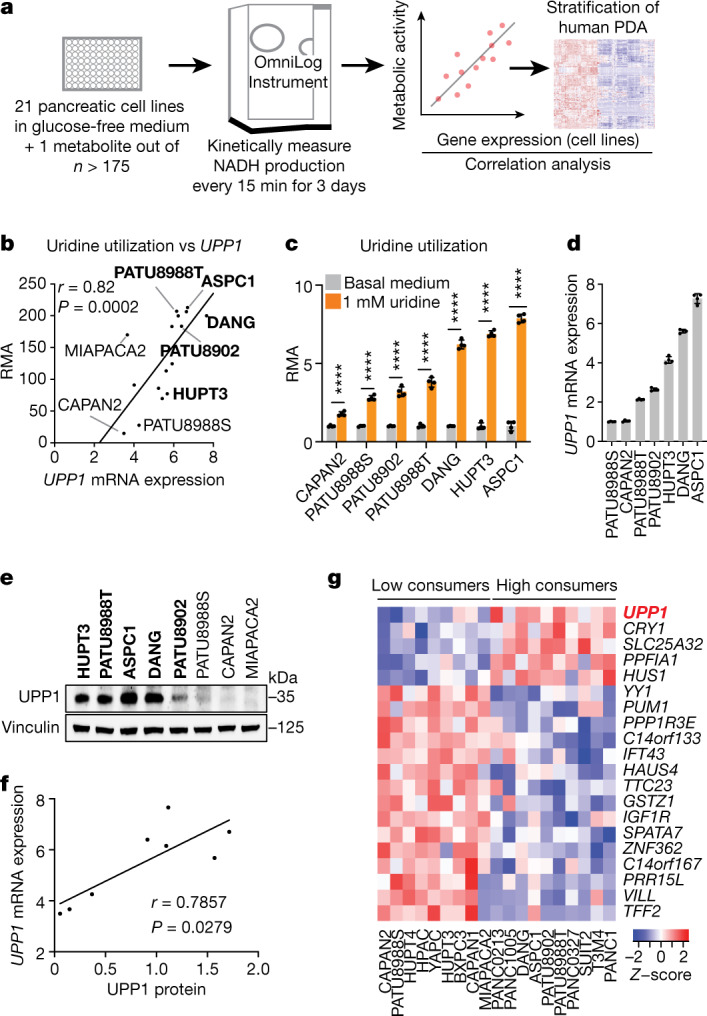

To screen for metabolites that fuel metabolism in nutrient-deprived PDA cells, we applied the Biolog phenotypic screening platform on 19 human PDA cell lines and 2 immortalized, non-malignant pancreas cell lines (human pancreatic stellate cells and human pancreatic nestin-expressing cells) (Fig. 1a). We used the screen to assess cellular ability to capture and metabolize more than 175 nutrients in a 96-well arrayed format under nutrient-limiting conditions (0 mM glucose, 0.3 mM glutamine and 5% dialysed fetal bovine serum (FBS)). The nutrient panel included carbon energy and nitrogen substrates (Supplementary Table 1). Metabolic activity was assessed by monitoring the reduction of a tetrazolium-based dye, a readout of cellular reducing potential, every 15 min for approximately 3 days (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Analyses of nutrient consumption profiles revealed several metabolites that, in the absence of glucose, were utilized at similar levels as the glucose positive control (Extended Data Fig. 1b). For example, adenosine, uridine and several sugars were utilized by most of the cell lines.

Fig. 1. Profiling of metabolite utilization in PDA cells identifies uridine.

a, Scheme of the nutrient metabolism screening assay and the correlation with gene expression in PDA cell lines and tumours. b, Spearman correlation (r) between the normalized relative metabolic activity (RMA) for uridine catabolism in the screening data and UPP1 mRNA expression data from an independent dataset17 (16 PDA cell lines). UPP1-high cell lines are shown in bold. c, The RMA in a subset of PDA cell lines following supplementation with 1 mM uridine for 3 days in glucose-free condition. d, Quantitative PCR (qPCR) validation of UPP1 mRNA expression in a subset of PDA cell lines. e, Immunoblot showing basal UPP1 expression in PDA cell lines. Blots are representative of three technical replicates with similar results. f, Spearman correlation (r) between protein densitometry analysis of the blot in e and UPP1 mRNA expression in the eight PDA cell lines highlighted in e. g, Top 20 genes differentially expressed by the PDA cell lines that were identified as uridine-high consumers/metabolizers compared with uridine-low consumers from the nutrient metabolism screen. Data source: Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE). Data in c,d are mean ± s.d. See Methods ‘Statistics and reproducibility’ section for additional information.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Correlation of nutrient utilization with gene expression identifies uridine and UPP1.

a. Schematic overview of the parameters measured by the Biolog Phenotype Microarray. b. Heatmap showing the high confidence metabolites (HCMs), namely, the metabolites that were utilized above or below the median of negative controls as determined by one-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test. Legend denotes fold change relative to median negative control signal, where red shows high utilization and blue shows low utilization. c. Spearman correlation plot, indicating the genes that showed positive or negative correlation with metabolites’ RMA in the Biolog screen. d. Spearman correlations, r, between UPP1 expression in cell lines (ref. 17) and RMA of nucleosides that were included in the Biolog screen. n = 16 PDA cell lines. e. Heatmap showing the expression of glycolysis genes in human PDA tumours ranked based on UPP1 expression (dataset: GSE71729, UPP1 low, n = 72; high, n = 73). On the right: GSEA plot indicating the enrichment of glycolysis hallmark in the UPP1 high relative to the low tumours. NES, normalized enrichment score. f. Downregulated pathways in PDA cell lines that metabolize uridine at a high level, as revealed by gene ontology (GO) analysis of the differentially expressed genes (P < 0.05). GO analysis was performed with DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp). Analysis was based on the differential genes derived from CCLE data and part of the data shown in Fig. 1g. g. GSEA plots of significantly enriched KEGG pathways in UPP1-high PDA tumours relative to UPP1 low tumours. Plots are part of the data (e) from the analysis of GSE71729 human PDA dataset. Statistics and reproducibility: a, The kinetic measurement evaluated several parameters, including the time taken for cells to adapt to and catabolize a nutrient (lambda), the rate of uptake and catabolism (mu or slope), the total metabolic activity (area under the curve; AUC), and the maximum metabolic activity. The values from the maximum catabolic efficiency (maximum height, A) of the respective metabolites were used to determine relative metabolic activity (RMA).

Uridine consumption correlates with UPP1

To select lead metabolites for investigation, we correlated metabolite utilization patterns to the expression of metabolism-associated genes using a public dataset17,18. From the top metabolite and gene correlation pairs (Extended Data Fig. 1c), we pursued uridine and uridine phosphorylase 1 (UPP1) (r = 0.82, P = 0.0002; Fig. 1b) for the following reasons. First, UPP1 expression correlated positively with the metabolic activity from its known substrate, uridine. Second, our in vitro validation showed that all tested PDA cells utilized uridine, although to varying degrees (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1b), suggesting that it is a broadly used metabolic fuel. Third, contrary to our expectation that nutrients used in the absence of glucose would be carbohydrates, uridine was unusual in that it is a nucleoside. Finally, to our knowledge, UPP1-mediated uridine metabolism is unexplored in the context of PDA.

We further confirmed the correlation of uridine catabolism and UPP1 expression by mRNA and protein analyses (Fig. 1d–f). To determine the specificity of this association, we assessed the correlation of UPP1 expression to other nucleosides in the Biolog screen. Although both inosine and adenosine were readily catabolized, their utilization was not correlated with UPP1 expression. Thymidine was neither actively metabolized nor correlated, when compared with negative controls (Extended Data Fig. 1d). These results indicate that the association between UPP1 expression and uridine catabolism is robust and specific.

Next, we rank-sorted the PDA cell lines into high and low uridine metabolizers on the basis of the Biolog data, and identified more than 700 differentially expressed genes (P < 0.05) between these groups using the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) data19 (Supplementary Table 2). Consistent with our previous correlation analysis in a different dataset (Extended Data Fig. 1c), UPP1 was the top gene in uridine-high consumers/metabolizers in the CCLE dataset (Fig. 1g). Pathway analysis of the upregulated genes in the uridine-high metabolizers (that is, UPP1-high cell lines) showed upregulation of endocytosis and several inflammation and/or immune-related pathways, notably NFκB signalling (Supplementary Table 3). We also observed that UPP1-high tumours exhibit higher expression of glycolysis genes (Extended Data Fig. 1e), indicating a potential link between the UPP1–uridine axis and energy metabolism. By contrast, UPP1-high cell lines and UPP1-high PDA tumours from patients displayed a profound downregulation of other metabolic pathways (Extended Data Fig. 1f,g), notably amino acid, fatty acid and glutathione metabolism.

Uridine-derived ribose fuels metabolism

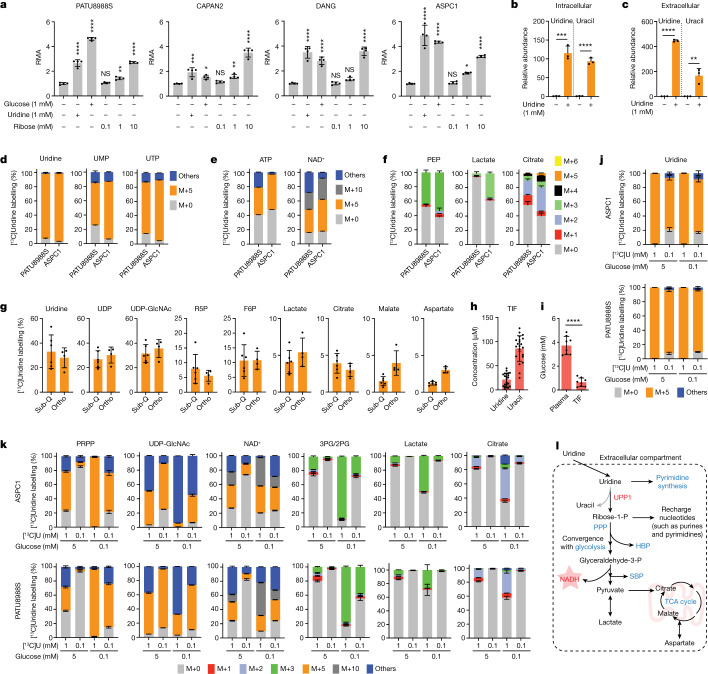

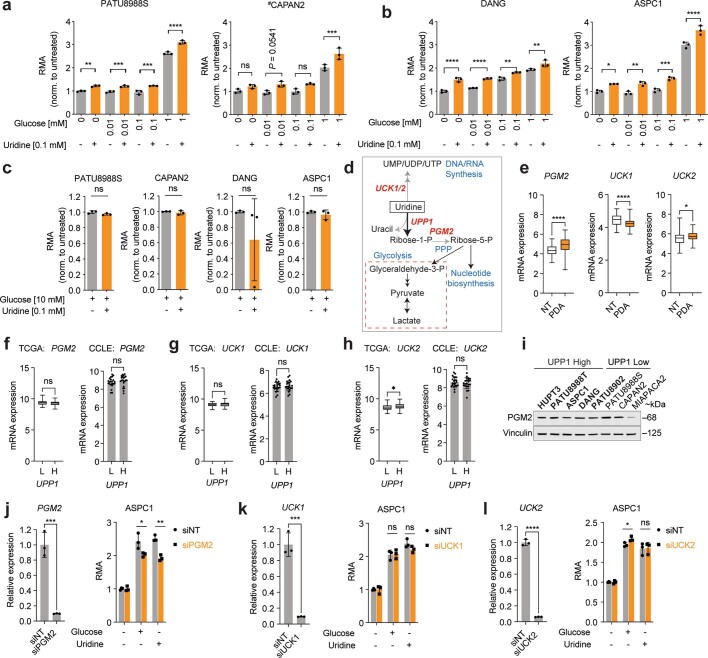

Our screen (Fig. 1a) was performed in glucose-free medium to reveal both metabolites whose use would otherwise be overshadowed by glucose, and the carbon sources that could act in place of glucose. Thus, we next directly assessed the metabolic activity of equimolar glucose and uridine. Across four PDA cell lines, uridine and glucose fuelled metabolism to a similar degree (Fig. 2a). Previous reports have also documented that uridine can substitute for glucose by supporting nucleotide metabolism20–26. However, our screening data illustrate that uridine supplementation increases the cellular reducing potential. Together with the observed connection with UPP1, which catalyses the cleavage of uridine to ribose-1-phosphate and uracil, we hypothesized that the UPP1-liberated ribose is recycled into central carbon metabolism to support cellular reducing potential. To test this hypothesis, we supplemented glucose-deprived cells with ribose, a cell-permeable substitute for ribose 1-phosphate. Indeed, similar to exogenous uridine, ribose supplementation fuelled the reducing potential (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Uridine-derived ribose supports nutrient-restricted PDA.

a, RMA of four PDA cell lines supplemented with glucose, uridine or ribose under nutrient-limiting culture conditions (0 mM glucose, 0.3 mM glutamine and 5% dialysed FBS). b,c, Intracellular and extracellular uridine and uracil after 24 h culture of PATU8988S cells in medium with no glucose and 10% dialysed FBS with or without 1 mM uridine as measured by LC–MS. d–f, Mass isotopologue distribution of carbon derived from [13C5]uridine in uridine, UMP and UTP (d), ATP and NAD+ (e) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), lactate and citrate (f) in the indicated cell lines after 24 h culture with 1 mM uridine. g, Isotope tracing showing [13C5]uridine-derived carbon labelling in subcutaneous (sub-Q) or orthotopically (ortho) implanted KPC 7940b tumours collected 1 h after injecting the mice with 0.2 M [13C5]uridine. F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; R5P, ribose-5-phosphate; UDP-GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine; h, Absolute quantification via metabolomics of uridine and uracil concentration in the TIF of orthotopic PDA tumours from syngeneic mouse KPC cells. i, Absolute quantification via metabolomics of glucose concentration in the pancreatic TIF and plasma of mice orthotopically implanted with KPC 7490b syngeneic tumours. j,k, Mass isotopologue distribution of [13C5]uridine ribose-derived carbon after 24 h culture of ASPC1 and PATU8988S cells in medium supplemented with 1 mM or 0.1 mM uridine and each with 5 mM or 0.1 mM glucose. j, Uridine. k, PRPP, UDP-GlcNAc, NAD+, 3-phosphoglycerate/2-phosphoglycerate (3PG/2PG), lactate and citrate. PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate. l. Schematic depicting the fate of uridine-derived ribose carbon in PDA cells actively catabolizing uridine. Glyceraldehyde-3-P, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; HBP, hexosamine biosynthetic pathway; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; ribose-1-P, ribose-1-phosphate; SBP, serine biosynthesis pathway. See Methods ‘Statistics and reproducibility’ section for additional information.

In our initial screen, glutamine concentration was also intentionally low (0.3 mM), as it is an important anaplerotic substrate that fuels tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and proliferation in PDA27. Uridine potentiated reducing potential with or without glutamine and had a greater effect when glutamine was present (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Together, these data suggest that uridine and glucose similarly fuel central carbon metabolism distinctly from glutamine.

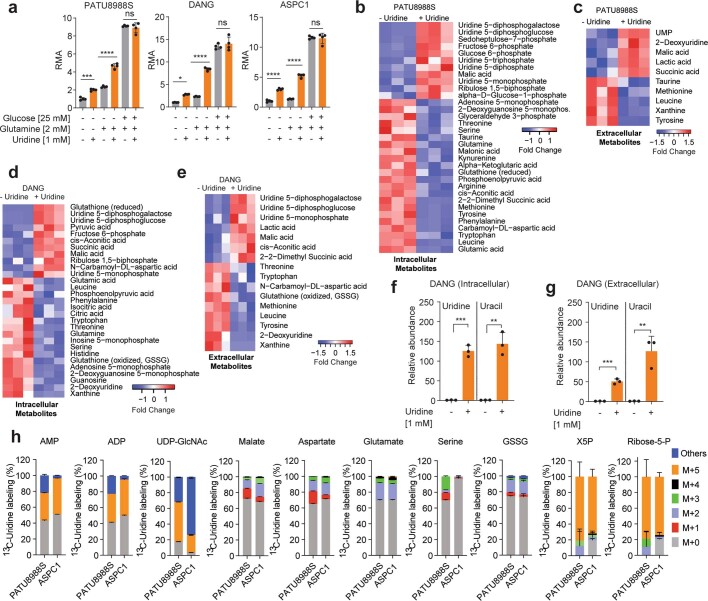

Extended Data Fig. 2. Nutrient-deprived PDA use uridine to support metabolism.

a. Relative RMA upon uridine supplementation with or without glucose and glutamine. n = 4 biologically independent samples per group per cell line. b. Differential changed (P < 0.05) intracellular and c) extracellular metabolites from PATU8988S cells supplemented with 1 mM uridine in glucose-free medium for 24 h, as determined by LC-MS metabolomics. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. d. Differentially changed (P < 0.05) intracellular and e) extracellular metabolites from DANG cells supplemented with 1 mM uridine in glucose-free medium for 24 h, as determined by LC-MS metabolomics. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. f. Intracellular and g) extracellular uridine and uracil from DANG cells supplemented with 1 mM uridine in glucose-free medium for 24 h, as determined by LC-MS. Plots in f-g are from the same experiment as d-e. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. Statistical significance was measured using two-tailed unpaired t-test. Intracellular – comparison between no uridine and 1 mM uridine: *** P = 0.0001 for uridine, ** P = 0.0011 for uracil. Extracellular – comparison between no uridine and 1 mM uridine: *** P = 0.0002 for uridine, ** P = 0.0044 for uracil. h. Mass isotopologue distribution of 13C5-uridine ribose-derived carbon in the displayed metabolites after 24 h culture in a glucose-free medium supplemented with 1 mM uridine. n = 3 biologically independent samples per cell line. Tracing experiments were performed twice in these cells with similar results. Data (a, f, g, h) are shown as mean ± s.d. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; UDP-GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine; X5P, xylulose 5-phosphate. Statistics and Reproducibility: a, n = 4 biologically independent samples per group per cell line. Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. PATU8988S (comparison between cells cultured in (−) glucose/glutamine/uridine and (−) glucose/glutamine/+uridine: *** P = 0.0007, comparison between (−) and (+) uridine in the presence of glutamine and without glucose: **** P < 0.00001, comparison between (−) and (+) uridine in the presence of glutamine and glucose: P = ns (0.8856)). DANG (comparison between cells cultured in (−) glucose/glutamine/uridine and (−) glucose/glutamine/+uridine: * P = 0.0165, comparison between (−) and (+) uridine in the presence of glutamine and without glucose: **** P < 0.0001, comparison between (−) and (+) uridine in the presence of glutamine and glucose: P = ns (0.7971)). ASPC1 (comparison between cells cultured in (−) glucose/glutamine/uridine and (−) glucose/glutamine/+uridine: **** P < 0.0001, comparison between (−) and (+) uridine in the presence of glutamine and without glucose: **** P < 0.00001, comparison between (−) and (+) uridine in the presence of glutamine and glucose: P = ns (0.9968)).

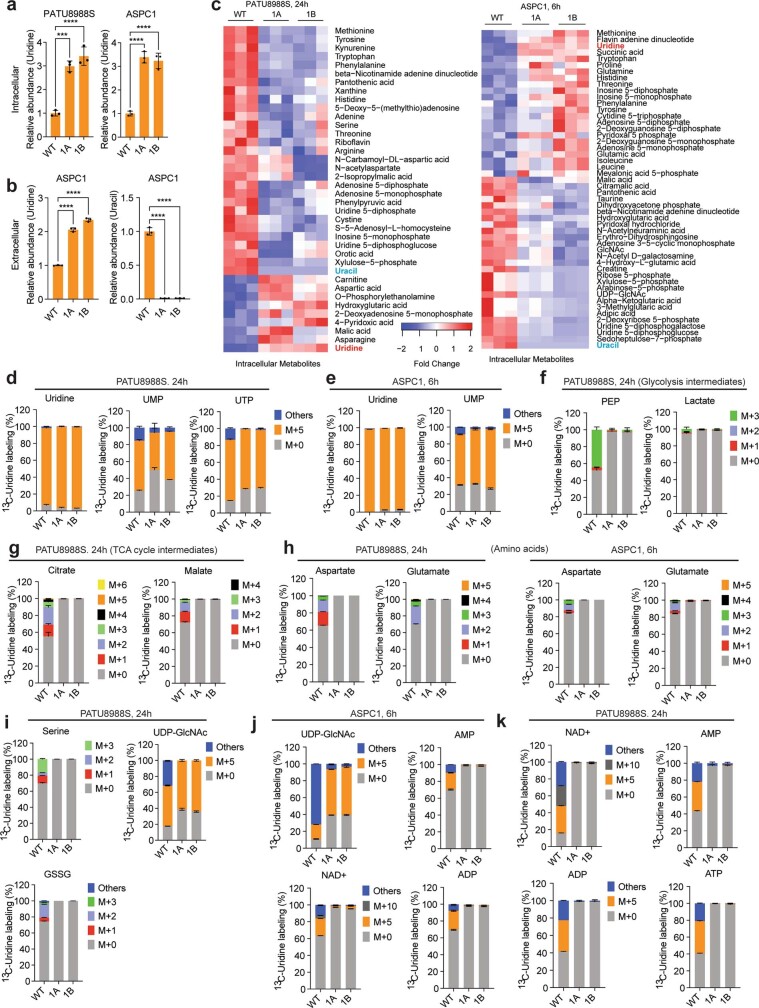

Next, we provided uridine to the UPP1-low PATU8988S and the UPP1-high DANG cell lines under glucose deprivation and applied liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS)-based metabolomics28. In both cell lines, uridine supplementation led to increased levels of glycolytic intermediates and lactate secretion (suggesting glycolytic flux), uridine derivatives (suggesting overflow metabolism), amino acids (indicative of increased anabolism) and TCA cycle intermediates (suggesting more mitochondrial activity) (Extended Data Fig. 2b–e). Moreover, supplementation with uridine led to a marked accumulation of intracellular uridine and over 100-fold increase in uracil content in the medium (Fig. 2b,c and Extended Data Fig. 2f,g), consistent with uridine capture, ribose extraction and uracil release. Notably, the intracellular uracil concentration increased by a similar amount of uridine, reflective of direct conversion of substrate to product (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 2f). Collectively, these profiling efforts support a model in which uridine is catabolized to broadly fuel PDA cell metabolism.

To precisely delineate how uridine is metabolized, we used LC–MS to trace the metabolic fate of isotopically labelled uridine ([13C5]uridine with uniformly labelled ribose carbon)29 in PATU8988S (UPP1-low) and ASPC1 (UPP1-high) cell lines. Both cell lines demonstrated high uridine, UMP and UTP labelling (over 90%), as indicated by M+5 from ribose (Fig. 2d). Other nucleotides, such as ATP, AMP and ADP (all M+5), as well as NAD+ (M+5, M+10) were also labelled (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 2h), demonstrating the use of uridine-derived ribose for ribosylation of the adenine base. Also labelled were glycolytic (PEP, pyruvate and lactate), PPP (X5P and ribose-5-phosphate), hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (UDP-GlcNAc) and TCA cycle intermediates (malate and citrate), as well as non-essential amino acids (aspartate, glutamate and serine) and oxidized glutathione (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 2h).

To determine the relevance of uridine metabolism for pancreatic tumours in vivo, we implanted mouse syngeneic pancreatic cancer cells into the pancreas of immunocompetent hosts to establish tumours. Then, we injected these mice with [13C5]uridine, and collected tumour tissues after 1 h for LC–MS analysis. Indeed, there was a robust uptake of uridine by the tumours, with almost 30% of the uridine pool being labelled. We observed the M+5 label in pyrimidine and purine species (that is, ribose salvage) as well as in glycolytic and TCA cycle intermediates (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 3a). 13C incorporation into the TCA cycle was low in vivo, presumably owing to the short duration of labelling. Nearly identical results to those from orthotopic studies were observed in subcutaneous tumours from immune-competent mice. These results confirm that PDA catabolizes uridine in vivo.

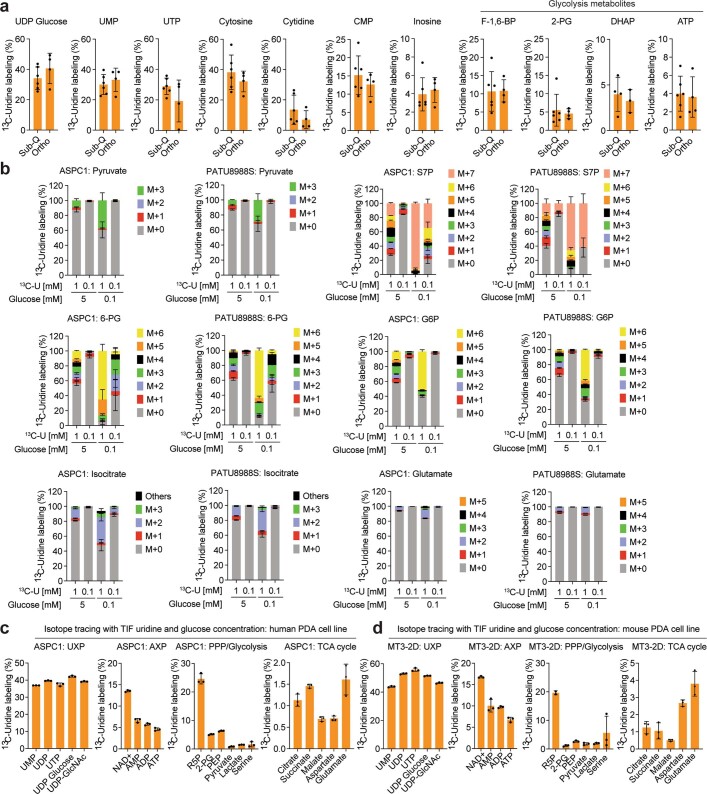

Extended Data Fig. 3. PDA metabolize uridine via central carbon metabolism in vitro and in vivo.

a. Isotope tracing showing 13C5-uridine ribose-derived carbon labelling in subcutaneous (Sub-Q) or orthotopically (Ortho) implanted KPC 7940b tumours collected 1 h after injecting the mice with 200 µL or 50 µL (Sub-Q) 0.2 M 13C5-uridine. Number of samples: Sub-Q = 6 tumours from 3 mice injected on the left and right flanks; Ortho = 4 tumours from 4 mice. Mode of uridine injection is intratumoural for Sub-Q and intraperitoneal for Ortho. b. Mass isotopologue distribution of 13C5-uridine ribose-derived carbon after 24 h culture of ASPC1 and PATU8988S cells in medium supplemented with 1 mM or 0.1 mM uridine, each with 5 mM or 0.1 mM glucose concentration. n = 4 biologically independent samples per group. M – mass; ‘Others’ – indicate M other than M+0 or M+5, where applicable. c–d. Isotope tracing showing metabolite labelling upon supplementation with 13C5-uridine at the TIF uridine and glucose concentrations shown in Fig. 2h,i, after 12 h of culturing c) human PDA cell line ASPC1 and d) murine PDA cell line MT3-2D. The cell lines were cultured in medium supplemented with 25 µM 13C5-uridine and 0.65 mM glucose. n = 3 biologically independent samples per cell line. AXP – AMP, ADP, ATP, and related metabolites; UXP – UMP, UDP, UTP and related metabolites. The experiments (a-d) were performed once. Data (a-d) are shown as mean ± s.d, where applicable. 2-PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; 6-PG, 6-phosphogluconate; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; F1,6-BP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; CMP, cytidine monophosphate; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; S7P, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate; UDP, uridine diphosphate; UMP, uridine monophosphate; UTP, uridine triphosphate; UDP-GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine.

In parallel, we collected tumour interstitial fluid (TIF) from independent orthotopic allograft tumours and quantified bulk uridine and glucose concentrations by LC–MS. Uridine and glucose were present in the low and high micromolar concentration range, respectively (Fig. 2h,i), similar to previous findings30. To determine how physiological concentrations of glucose and uridine affected uridine metabolism, we grew two PDA lines in 5 mM or 0.1 mM glucose and 0.1 mM or 1 mM [13C5]uridine and analysed labelling patterns. First, the labelling of uridine was nearly 100% (Fig. 2j). At the low equimolar concentration (0.1 mM uridine and glucose), uridine carbon contributed to several metabolites in the PPP, PRPP (involved in nucleotide biosynthesis), NAD+, glycolysis, and TCA cycle, exceeding 50% enrichment in some cases(Fig. 2k and Extended Data Fig. 3b). When glucose was 50-fold higher (5 mM), uridine carbon contributed to a much lower level to metabolite labelling, whereas at lower glucose concentrations, uridine carbon dominated, consistent with competition for these two carbon sources into the same pathways. Further isotope tracing using the exact TIF concentrations of uridine and glucose showed that both human (ASPC1) and mouse (MT3-2D) cells incorporate uridine into central carbon metabolism (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). We confirmed these results in four human PDA lines with the tetrazolium assay: uridine supported bioenergetics at physiological (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b) but not at elevated glucose levels (Extended Data Fig. 4c).

Extended Data Fig. 4. Cellular pathways for ribose salvage from uridine.

a–c. Relative metabolic activity (RMA) of PDA cell lines depicting the preferential use of uridine at (a,b) low glucose concentration (0-1 mM) but not at c) the high glucose concentration (10 mM), over a 96 h culture. d. Schematic depicting metabolic pathways for uridine utilization. e. Expression of PGM2, UCK1, and UCK2 in non-tumour (NT) and PDA tissue samples from the GSE71729 dataset. Number of samples: NT = 46, PDA = 145. f–h. Expression of PGM2, UCK1 and UCK2 in TCGA (human PDA tumour) and CCLE (human cell line) data separated into UPP1 low (L) and high (H) subsets. i. Western blot for PGM2 in PDA cell lines. Presented in bold are cells that express high UPP1. These samples are the same batch as the data shown in Fig. 1e and the blot was generated during one of the technical replicates of that western blotting. kDa, unit for molecular weight. j. qPCR for PGM2 in ASPC1 cells transfected with siPGM2 compared to non-targeting (siNT) control. On the right: RMA in PGM2 knockdown cells +/− uridine (1 mM) or glucose (1 mM). k. qPCR for UCK1 in ASPC1 cells transfected with siUCK1 compared to non-targeting (siNT) control. On the right: RMA in UCK1 knockdown cells +/− uridine (1 mM) or glucose (1 mM). l. qPCR for UCK2 in ASPC1 cells transfected with siUCK2 compared to non-targeting (siNT) control. On the right: RMA in UCK2 knockdown cells +/− uridine (1 mM) or glucose (1 mM). Statistics and reproducibility: a–c, n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance for data in a-b was measured using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. PATU8988S (comparison between no glucose and no glucose + uridine [0.1 mM]: **P = 0.0017; 0.01 mM glucose and 0.01 mM glucose + uridine: ***P = 0.0008; 0.1 mM glucose and 0.1 mM glucose + uridine: ***P = 0.0002; 1 mM glucose and 1 mM glucose + uridine: ****P < 0.0001). CAPAN2 (comparison between no glucose and no glucose + uridine: P = ns (0.5673); 0.01 mM glucose and 0.01 mM glucose + uridine: P = ns (0.0541); 0.1 mM glucose and 0.1 mM glucose + uridine: P = ns (0.092); 1 mM glucose and 1 mM glucose + uridine: ***P = 0.0007. #All four group comparisons have significant P: 0.0468, 0.014, 0.0089, 0.0222, respectively, when directly compared using two-tailed unpaired t test). DANG (comparison between no glucose and no glucose + uridine: ****P < 0.0001; 0.01 mM glucose and 0.01 mM glucose + uridine: ****P < 0.0001; 0.1 mM glucose and 0.1 mM glucose + uridine: **P = 0.0051; 1 mM glucose and 1 mM glucose + uridine: **P = 0.0051). ASPC1 (comparison between no glucose and no glucose + uridine: *P = 0.0203; 0.01 mM glucose and 0.01 mM glucose + uridine: **P = 0.0031; 0.1 mM glucose and 0.1 mM glucose + uridine: ***P = 0.0003; 1 mM glucose and 1 mM glucose + uridine: ****P < 0.0001). Statistical significance for data in c was measured using two-tailed unpaired t test and P = ns (0.0852, 0.3509, 0.3021 and 0.3875 for PATU8988S, CAPAN2, DANG and ASPC1, respectively, in the comparison of no uridine vs 0.1 mM uridine groups in the presence of 10 mM glucose). d. Uridine can be channeled into DNA or RNA synthesis by direct phosphorylation from UCK1/2. Uridine can also be catabolized via UPP1 to produce uracil and ribose 1-phosphate. Ribose 1-phosphate is converted to ribose-5-phosphate by PGM2 and fuel pentose phosphate pathway, nucleotide biosynthesis and glycolysis. e. Statistical significance was measured using two-tailed unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. Comparison between NT and PDA: PGM2, ****P < 0.0001; UCK1, ****P < 0.0001; UCK2, *P = 0.018. Box plot statistics – PGM2 (NT: minima = 3.097, maxima = 5.527, median = 4.335, 25th percentile = 3.992, 75th percentile = 4.74; PDA: minima = 2.386, maxima = 6.433, 25th percentile = 4.424, median = 4.961, 75th percentile = 5.457), UCK1 (NT: minima = 3.7, maxima = 5.1, median = 4.5, 25th percentile = 4.2, 75th percentile = 4.7; PDA: minima = 3.6, maxima = 5.1, median = 4.2, 25th percentile = 4, 75th percentile = 4.4), UCK2 (NT: minima = 4.034, maxima = 7.615, median = 5.577, 25th percentile = 5.095, 75th percentile = 5.9; PDA: minima = 4.556, maxima = 6.93, median = 5.727, 25th percentile = 5.458, 75th percentile = 6.059). f-h. Number of samples: TCGA – UPP1 low = 75, high = 75; CCLE – UPP1 low = 22, high = 22. Statistical significance was measured using two-tailed unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. Comparison between L and H groups in TCGA (PGM2: P = ns (0.1226), UCK1: P = ns (0.311); UCK2: *P = 0.0327). In the CCLE L versus H comparison, PGM2, UCK1 and UCK2 have P = ns (0.3486, 0.4645, 0.4381, respectively). TCGA – The Cancer Genome Atlas, CCLE – Cancer Cell Line Encyclopaedia. i. Vinculin is used as a loading control. j. Number of samples: qPCR = 3, RMA = 3 biologically independent samples per group. qPCR – statistical significance was measured using unpaired t test; comparison between siNT and siPGM2: ***P = 0.0007. RMA – statistical significance was measured using multiple unpaired t tests with two-stage two-step method; comparison of siNT and siPGM2 in the presence of 1 mM glucose and no uridine: *P = 0.0452, and **P = 0.0014 in the presence of 1 mM uridine and no glucose. k. Number of samples: qPCR = 3, RMA = 3 biologically independent samples per group. qPCR – statistical significance was measured using two-tailed unpaired t test; comparison between siNT and siUCK1: ***P = 0.0004. RMA – statistical significance was measured using multiple unpaired t tests with two-stage two-step method. Comparison of siNT and siUCK1 knockdown samples in the presence of 1 mM glucose and no uridine: P = ns (0.8652), and P = ns (0.131) in the presence of 1 mM uridine and no glucose. l. Number of samples: qPCR = 3, RMA = 3 biologically independent samples per group. qPCR – statistical significance was measured using unpaired t test; comparison between siNT and siUCK2: ****P < 0.0001. RMA – statistical significance was measured using multiple unpaired t tests with two-stage two-step method; comparison of siNT and siUCK1 knockdown cells in the presence of 1 mM glucose and no uridine: *P = 0.035, and P = ns (0.8653) in the presence of 1 mM uridine and no glucose. Data (a–c, f–h, j–l) are shown as mean ± s.d. The experiments were performed once (a–c, k), and twice (j,l) with similar results.

Our data suggest that uridine yields ribose-1-phosphate via UPP1 to fuel both catabolic and biosynthetic metabolism. Ribose-1-phosphate can be converted to the PPP product ribose-5-phosphate by phosphoglucomutase 2 (PGM2) to enter nucleotide biosynthesis. Alternately, cells can convert uridine to UMP via uridine-cytidine kinase (UCK1/2) in the pyrimidine salvage pathway (Extended Data Fig. 4d). We found that PGM2 and UCK2 are high in PDA and UCK1 is low, but these genes were largely uncorrelated with UPP1 (Extended Data Fig. 4e–h). Being the most upregulated, we tested PGM2 by western blot and found it to be expressed in most PDA cells but uncorrelated with UPP1 (Extended Data Fig. 4i). Inhibition of the three genes using short interfering RNA (siRNA) showed that only PGM2 knockdown suppressed the uridine-mediated rescue of metabolic activity following glucose deprivation (Extended Data Fig. 4j–l). Together, these data support our model in which uridine catabolism converges with central carbon metabolism, and they also reveal that exogenous uridine fuels PDA metabolism in a similar way to glucose, supplying carbon for redox, nucleotide, amino acid and glycosylation metabolite biosynthesis (Fig. 2l).

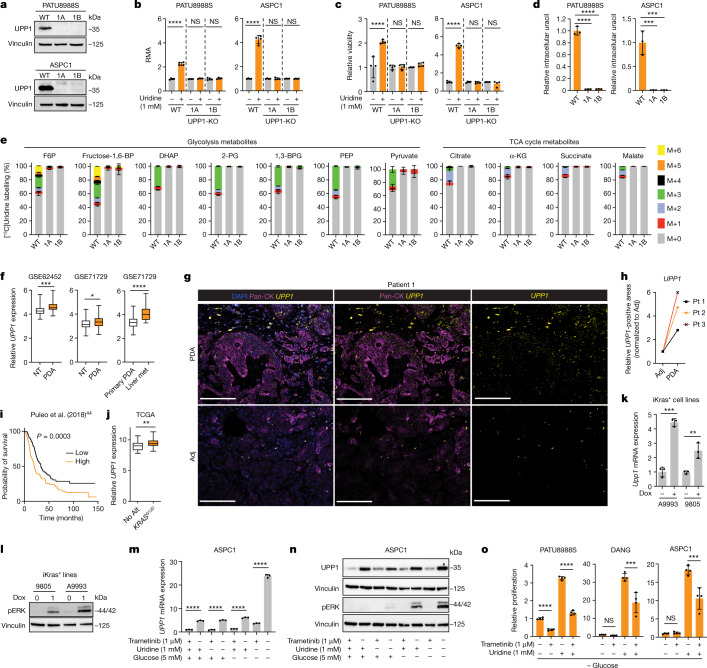

UPP1 provides uridine-derived ribose

To confirm the role of UPP1 in uridine catabolism, we knocked out UPP1 (UPP1-KO) using CRISPR–Cas9 in the PATU8988S (UPP1-low) and ASPC1 (UPP1-high) human PDA cell lines and validated two independent clones per cell line (Fig. 3a). In these knockout lines, the ability of uridine to rescue NADH production in the absence of glucose (Fig. 3b) or cellular bioenergetics, read out by ATP-based viability (Fig. 3c), was abolished. Consistent with the blockade of uridine catabolism, metabolomics showed that UPP1-KO cell lines displayed an increase in intracellular and extracellular uridine (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b) accompanied by a marked drop in intracellular and extracellular uracil (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 5b). Furthermore, UPP1-KO broadly altered the intracellular metabolome of both cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Notebly, ASPC1 cells are highly sensitive to glucose deprivation in combination with UPP1-KO, thus metabolomics in this cell was performed after 6 h when assessing the knockout effect.

Fig. 3. KRAS-driven UPP1 liberates ribose and is increased in PDA.

a, Western blot validation of UPP1-KO in human PDA cell lines. 1A and 1B denote UPP1-KO cells. WT, wild type. b,c, RMA from tetrazolium assay showing uridine-derived reducing potential (b) and CellTiter Glo showing ATP production (c) in UPP1-KO and wild-type PATU8988S and ASPC1 cells cultured with or without 1 mM uridine for 48 h. d, Relative intracellular uracil as determined by LC–MS in wild-type and UPP1-KO human PDA clones cultured with 1 mM uridine for 24 h (PATU8988S) or 6 h (ASPC1). e, Mass isotopologue distribution of 1 mM [13C5]uridine-derived carbon in glycolysis and TCA cycle metabolites in wild-type or UPP1-KO ASPC1 cells after 6 h. α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; 1,3-BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; fructose-1,6-BP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. f, UPP1 mRNA expression in PDA tumours and non-tumoural pancreas tissues in microarray datasets. Liver met, liver metastasis; NT, non-tumour tissue. g,h, RNAscope showing representative UPP1 mRNA expression in tumour and adjacent normal tissue (adj) sections (g) and quantification from three patients (Pt 1–3) with PDA (h). Scale bars, 100 μm. i, Kaplan–Meier overall survival analysis (log-rank test) based on ranked UPP1 expression in the PDA dataset published previously44. j, Comparison of UPP1 mRNA expression in human PDA tumours annotated as KRASG12D or with no alteration (No Alt) in KRAS from the TCGA dataset. k, qPCR data showing Upp1 expression in mouse cell lines (A9993 and 9805) with doxycycline-inducible oncogenic Kras (iKras*). l, Western blot validation of MAPK pathway induction as indicated by phosphorylated ERK (pERK) in the iKras* cell lines. m,n, qPCR for UPP1 mRNA (m) and western blot for pERK and UPP1 (n) in ASPC1 cells cultured with or without 5 mM glucose, 1 mM uridine and 1 μM trametinib for 48 h. o, MTT assay showing relative proliferation of PDA cell lines with 1.25 μM trametinib and 1 mM uridine in the absence of glucose. See Methods ‘Statistics and reproducibility’ section for additional information.

Extended Data Fig. 5. UPP1 mediates the liberation of uridine-derived ribose for central carbon metabolism.

a. Relative intracellular uridine level in the UPP1 knockout PATU8988S cells (after 24 h) and ASPC1 cells (6 h) compared to the wild type supplemented with 1 mM uridine in medium with 10% dialyzed FBS and no glucose. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group per cell line. Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. PATU8988S (intracellular uridine) – comparison between WT and 1A, ***P = 0.0002; comparison between WT and 1B, ****P < 0.0001. ASPC1 (intracellular uridine) – comparison between WT and 1A or 1B, ****P < 0.0001. b. Relative extracellular uridine and uracil in UPP1 knockout ASPC1 cells compared to the wild type supplemented with 1 mM uridine for 6 h in medium with 10% dialyzed FBS and no glucose. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Extracellular uridine: comparison between WT and 1A or 1B, ****P < 0.0001; extracellular uracil: comparison between WT and 1A or 1B, ****P < 0.0001. c. Heatmaps of significantly altered intracellular metabolites (P < 0.05) in PATU8988S cells after 24 h (left) and ASPC1 after 6 h (right), as measured by LC-MS. Data used for the intracellular uridine/uracil plots (a-b) were extracted from this profiling study. d–k. Mass isotopologue distribution of 1 mM 13C5-uridine ribose-derived carbon into the indicated metabolic pathways in wildtype (WT) or UPP1-KO PATU8988S and ASPC1 cells. M – mass; ‘Others’ – indicate M other than M+0 or M+5, where applicable. 1A and 1B denote UPP1-KO sgRNA clones. Data (a–b, d–k) are shown as mean ± s.d. Metabolomics experiments were done once. Statistics and reproducibility: Abbreviations – ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; NAD+ nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle; UDP-GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine; UMP, uridine monophosphate; UTP, uridine triphosphate.

We next used our isotope tracing metabolomics platform to determine the effect of UPP1-KO on uridine catabolism in PATU8988S and ASPC1 cells (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5d–k). The ribose-labelled [13C5]uridine tracing showed similar fractional enrichment of the intracellular uridine pool in the UPP1-KO and control cells (Extended Data Fig. 5d,e), indicative of unchanged, steady-state uridine uptake. By contrast, and consistent with our model, flux of uridine ribose-derived carbon into glycolysis (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5f), TCA cycle-associated metabolites (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5g), non-essential amino acids, oxidized glutathione and UDP-GlcNAc (in glycosylation), was holistically blocked or suppressed (Extended Data Fig. 5h,i). Recycling of uridine-derived ribose was also completely blocked in the UPP1-KO cells, as evidenced by the absence of carbon labelling in NAD+ and the bioenergetic metabolites AMP, ADP and ATP (Extended Data Fig. 5j,k). Together, these results reveal that the UPP1-mediated catabolism of uridine is indispensable for the utilization of uridine to support reducing potential, bioenergetics and cell proliferation, and provide a detailed molecular confirmation that UPP1 directly controls the utilization of uridine-derived ribose in PDA cells.

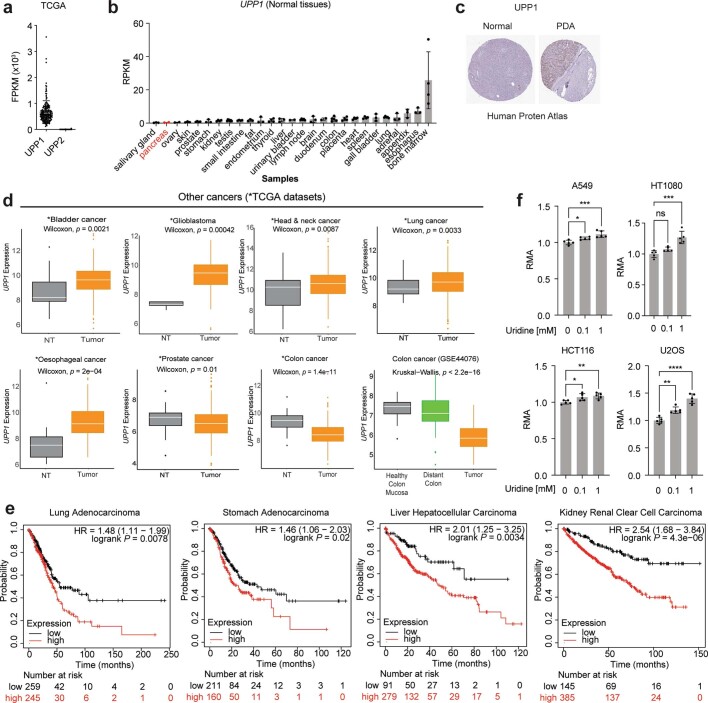

High UPP1 in PDA predicts poor survival

To further assess the relevance of UPP1 in PDA tumours, we next analysed its expression in publicly available human PDA datasets. We found that UPP1 is highly expressed in PDA tumours compared with non-tumoural samples, and also in liver metastasis compared with primary tumours (Fig. 3f). Its paralogue UPP2 is not expressed in this tumour type (Extended Data Fig. 6a), as observed in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data. We also observed from the Human Protein Atlas public database that UPP1 gene expression is extremely low in normal pancreas and UPP1 protein expression is high in PDA (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). Consistently, UPP1 expression is also high in several other non-PDA cancers from TCGA, with colon and prostate cancers being the notable exceptions (Extended Data Fig. 6d). High UPP1 also predicted poor survival outcome in lung, stomach, liver and renal cancers (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Indeed, we tested uridine utilization in several non-PDA cancer cell lines and observed a modest uridine-derived increase in metabolic activity (Extended Data Fig. 6f), supporting the potential relevance of this metabolite in other cancers.

Extended Data Fig. 6. UPP1 expression is elevated in PDA and other cancer types.

a. TCGA RNA seq data showing the expression of UPP1 and its paralog UPP2. FPKM, fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments. b. RNA seq showing UPP1 expression in various normal human tissues (Human Protein Atlas data), as obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) portal. c. Histological data showing UPP1 protein expression in normal pancreatic tissue compared to PDA. d. UPP1 expression in human non-PDA cancers accessed in publicly accessible datasets. e. Kaplan-Meier plot of survival probability (log-rank test) as obtained from KM-plotter (https://kmplot.com/analysis/) using the default parameters. f. Relative Metabolic Activity (RMA), reflecting NADH levels, in human non-PDA cancer cell lines supplemented with uridine (as indicated) in 1 mM glucose medium. n = 5 biologically independent samples per group per cell line. Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. A549 (lung cancer cell line, comparison between no uridine and 0.1 mM uridine, *P = 0.0405 or 1 mM uridine, ***P = 0.0004); HT1080 (fibrosarcoma cell line, comparison between no uridine and 0.1 mM uridine, P = ns (0.1773) or 1 mM uridine, ***P = 0.0001); HCT116 (colon cancer cell line, comparison between no uridine and 0.1 mM uridine, *P = 0.0294 or 1 mM uridine, **P = 0.0081); U2OS (osteosarcoma cell line, comparison between no uridine and 0.1 mM uridine, **P = 0.002 or 1 mM uridine, ****P < 0.0001). Statistics and reproducibility: a, n = 150 samples each. b. Sample size, n: salivary gland = 3, pancreas = 2, ovary = 2, skin = 3, prostate = 4, stomach = 3, kidney = 4, testis = 7, small intestine = 4, fat = 3, endometrium = 3, thyroid = 4, liver = 3, urinary bladder = 2, lymph node = 5, brain = 3, duodenum = 2, colon = 5, placenta = 4, heart = 4, spleen = 4, gall bladder = 3, lung = 5, adrenal = 3, appendix = 3, esophagus = 3, bone marrow = 4. RPKM, reads per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped. UPP1 expression in normal pancreas is extremely low (second lowest of the > 25 tissues compared). c. Data obtained from the Human Protein Atlas (URL for ‘Normal’ - https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000183696-UPP1/tissue/pancreas; PDA – https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000183696-UPP1/pathology/pancreatic+cancer#img). d. Sample size, n: NT = 19, tumour = 408 (bladder cancer, TCGA); NT = 5, tumour = 154 (glioblastoma, TCGA); NT = 44, tumour = 520 (head and neck cancer, TCGA); NT = 59, tumour = 551 (lung cancer, TCGA); NT = 11, tumour = 184 (oesophageal cancer, TCGA); NT = 52, tumour = 497 (prostate cancer, TCGA); NT = 41, tumour = 452 (colon cancer); health colon mucosa = 50, distant colon = 98, tumour = 98 (colon cancer, GSE44076). NT – non-tumour/adjacent normal tissue. Data (a-b, f) shown as mean ± s.d. The experiments were performed three times with similar results. Box plot statistics – TCGA, bladder carcinoma (primary: minima = 5.83, maxima = 13.5, median = 9.77, 25th percentile = 9.015, 75th percentile = 10.47; normal: minima = 6.61, maxima = 12.43, median = 8.35, 26th percentile = 8.03, 75th percentile = 9.59); glioblastoma multiforme (primary: minima = 5.71, maxima = 11.84, median = 9.585, 25th percentile = 8.79, 75th percentile = 10.143; normal: minima = 7.04, maxima = 7.63, median = 7.4, 25th percentile = 7.36, 75th percentile = 7.61); head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (primary: minima = 6.59, maxima = 15.64, median = 10.75, 25th percentile = 9.787, 75th percentile = 11.565; normal: minima = 6.38, maxima = 13.73, median = 10.42, 25th percentile = 8.672, 75th percentile = 11.065); lung adenocarcinoma (primary: minima = 6.45, maxima = 13.44, median = 9.8, 25th percentile = 9.13, 75th percentile = 10.49; normal: minima = 8.3, maxima = 11.39, median = 9.3, 25th percentile = 8.945, 75th percentile = 9.93); esophageal carcinoma (primary: minima = 6.7, maxima = 13.08, median = 9.26, 25th percentile = 8.578, 75th percentile = 10.21; normal: minima = 6.17, maxima = 12.39, median = 7.62, 25th percentile = 6.7, 75th percentile = 8.26); prostate adenocarcinoma (primary: minima = 3.96, maxima = 9.69, median = 6.58, 25th percentile = 5.98, 75th percentile = 7.14; normal: minima = 4.56, maxima = 8.62, median = 6.97, 25th percentile = 6.447, 75th percentile = 7.24); colon cancer (primary: minima = 6.41, maxima = 12.96, median = 8.535, 25th percentile = 8.068, 75th percentile = 9.07; normal: minima = 7.76, maxima = 11.29, median = 9.57, 25th percentile = 9.09, 75th percentile = 9.92). Colon cancer (GSE44076, primary: minima = 4.564, maxima = 7.608, median = 5.917, 25th percentile = 5.487, 75th percentile = 6.405; normal: minima = 4.568, maxima = 9.154, median = 7.18, 25th percentile = 6.781, 75th percentile = 7.824; healthy colon mucosal cells: minima = 5.884, maxima = 8.279, median = 7.529, 25th percentile = 7.153, 75th percentile = 7.74). Statistical significance was tested using two-sided Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis tests.

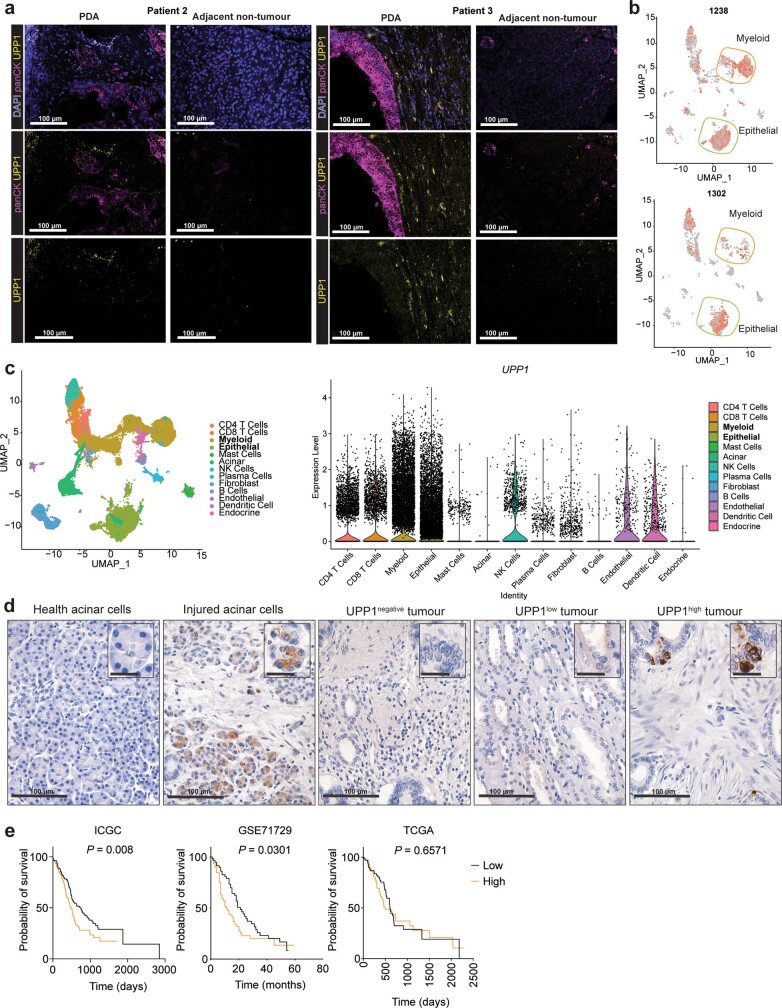

To independently validate UPP1 expression in human PDA, we used patient samples to assay tumoural UPP1 expression by RNAscope (Fig. 3g,h and Extended Data Fig. 7a), the cellular distribution of UPP1 expression by single cell RNA sequencing (Extended Data Fig. 7b,c), and UPP1 expression by immunohistochemistry (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Collectively, these data were consistent with public databases, illustrating UPP1 upregulation in human PDA relative to normal pancreas tissue. In addition, our histological assessment of injured acinar cells indicated that UPP1 is upregulated upon pancreatic injury (Extended Data Fig. 7d), suggesting a potential role in PDA formation. Finally, stratification of tumour datasets also showed that the high expression of UPP1 predicted poor overall survival outcome in three out of the four PDA patient cohorts we analysed (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 7e). Together, these data support a key role for UPP1 in PDA.

Extended Data Fig. 7. UPP1 is expressed in PDA and TME cells and predicts survival outcome.

a. RNAscope images showing UPP1 expression in tumour (PDA) compared to the adjacent non-tumour tissues. Pan-cytokeratin (PanCK) indicates the tumour cells; DAPI, nuclear stain. The images are representative of three 20x acquisitions per tissue slide, and of two independent experiments. Scale bar indicates 100 µm. b. UMAP plot showing the expression of UPP1 at the transcript level, as determined by single cell RNA seq of PDA tissues from two patients (#1238 and 1302). c. Violin plots showing UPP1 expression in various tumour microenvironment cell types, including myeloid and epithelial cells where UPP1 is highest. Right, UMAP plot showing the specific cell compartments expressing UPP1 for all patients’ samples combined (n = 16). Data used in plots b-c are from a previously published dataset55. d. Immunohistochemistry of UPP1 in patient biopsy sections from previously published tissue microarray48. Micrographs are representative from 213 patient samples in the microarray and two independent experiments. Large scale bar indicates 100 µm; scale bar on insets indicates 25 µm. e. Kaplan-Meier plot showing survival probability (log-rank test) based on UPP1 expression in three separate datasets. Each dataset was split into two – UPP1 high and UPP1 low – based on the ranked UPP1 expression value. Sample size: low = 133, high = 134 (ICGC); low = 62, high = 63 (GSE71729), low = 73, high = 73 (TCGA). TME – tumour microenvironment.

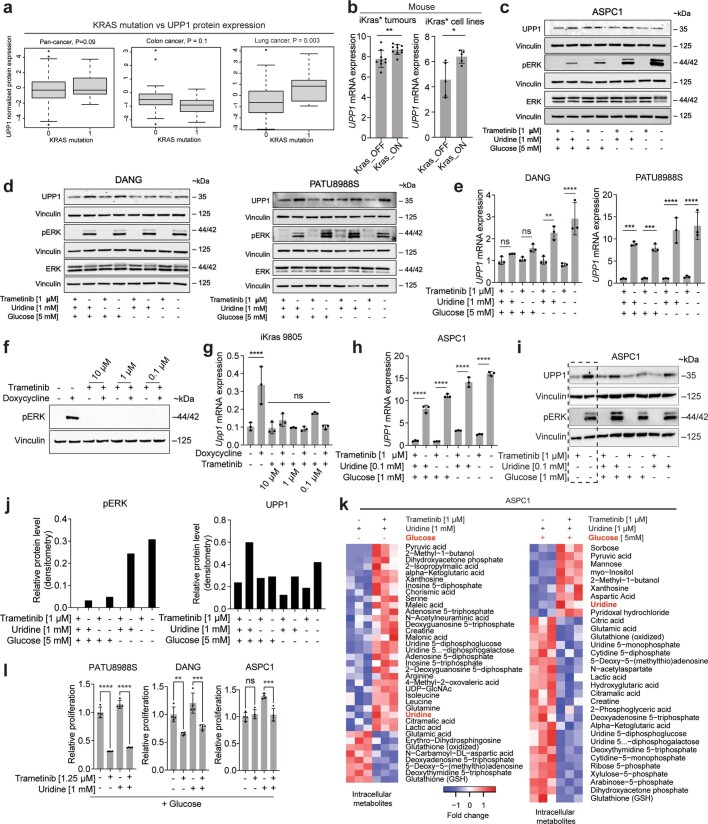

KRAS–MAPK pathway regulates UPP1

KRAS mutations are the signature transforming event observed in the majority of PDAs31. Using data from TCGA, we determined that PDA with the KRASG12D mutation express higher levels of UPP1 than those with no KRAS alteration (Fig. 3j). We also analysed the CCLE protein expression data of KRAS wild-type versus mutant cell lines across cancers and from lung or colorectal cancer. A targeted analysis of PDA lines was not performed because KRAS mutations are observed in all but one line in the CCLE. From the pan-analysis (n = 374), we observed a borderline, non-significant, association between KRAS status and UPP1 expression (P = 0.09) (Extended Data Fig. 8a), but lung cancer cell lines (n = 79) showed a significant association (P = 0.003). Colorectal cancer lines (n = 30) showed no difference or slightly reduced UPP1 in mutant KRAS lines (Extended Data Fig. 8a), consistent with the data in Extended Data Fig. 6d. The colon cancer results may be owing to the timing of KRAS mutation in tumour evolution and differences in its tissue-specific function relative to that of lung and PDA32.

Extended Data Fig. 8. KRAS-MAPK pathway activation and nutrient availability drive UPP1 expression.

a. Normalized UPP1 protein expression in Kras wildtype and mutant cell lines based on CCLE protein data accessed via the DepMap portal. b. Upp1 mRNA expression in iKras* orthotopic tumours and cell lines from dataset GSE32277. c-d. Western blot showing UPP1 expression in human PDA cell lines c) ASPC1 cells and d) DANG and PATU8988S after 24 h culture +/– trametinib [MEK inhibitor], uridine, or glucose. kDa, unit for molecular weight. e. qPCR for UPP1 in human PDA cell lines DANG and PATU8988S treated for 24 h with trametinib (1 µM), uridine (1 mM), or 5 mM glucose. f. Western blot showing pERK upon treatment of murine iKras 9805 cells for 24 h with trametinib or doxycycline (1 µg/mL). g. qPCR for Upp1 in iKras* 9805 mouse PDA cells, 24 h after treatment with trametinib or doxycycline (1 µg/mL). h. qPCR for UPP1 in ASPC1 cells treated for 48 h with trametinib and at 0.1 mM uridine or 1 mM glucose concentrations. i. Western blot for UPP1 and pERK treated for 48 h with trametinib and low glucose [1 mM] and near physiological uridine concentration [0.1 mM]. j. Densitometric quantification of pERK and UPP1 in the ASPC1 blots shown in Fig. 3n. k. Metabolomics profiling showing the spectrum of metabolic changes induced in ASPC1 upon pERK inhibition with trametinib [1 µM], 24 h after culture. l. MTT assay showing relative proliferation of PDA cell lines treated with 1.25 μM trametinib [MEK inhibitor] +/− 1 mM uridine in the presence of glucose [5 mM] at 96 h. Statistics and reproducibility: a, Sample size – wild type 0 and mutation 1: 304 and 69 (pan-cancer), 15 and 15 (colon cancer), 54 and 25 (lung cancer). Box plot statistics – pan-cancer (KRAS = 0: minima = −4.8237, maxima = 4.8004, median = −0.3029, 25th percentile = −1.3212, 75th percentile = 0.7687; minima = −2.1805, maxima = 3.7445, median = −0.3019, 25th percentile = −0.815, 75th percentile = 1.2867), colon (KRAS = 0: minima = −2.3253, maxima = 3.1201, median = -0.5127, 25th percentile = −0.8908, 75th percentile = −0.0958; KRAS = 1: minima = −2.1805, maxima = 0.2672, median = −0.9153, 25th percentile = −1.3926, 75th percentile = −0.5595), lung (KRAS = 0: minima = −2.7979, maxima = 4.0884, median = 0.4201, 25th percentile = -1.305, 75th percentile = 0.6032; KRAS = 1: minima = −0.9357, maxima = 3.7445, median = 0.8446, 25th percentile = −0.4923, 75th percentile = 1.3752). b. Sample size: tumours (Kras_OFF = 9, Kras_ON = 10), cell lines (Kras_OFF = 5, Kras_ON = 5). Statistical significance was measured using two-tailed unpaired t test. Comparison of Kras_OFF to Kras_ON: **P = 0.0088 (tumours) and *P = 0.0244 (cell lines). c-d. pERK is used as a readout for MAPK pathway induction/activity. ERK and Vinculin are used as loading controls. Blots are representative of two biological and technical replicates for ASPC1 and one biological replicate for PATU8988S and DANG with similar results. e. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. Statistical significance was measured with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Comparisons between groups for DANG (from left to right): P = ns (0.9097), P = ns (0.5014), **P = 0.0025 and ****P < 0.0001. Comparisons between groups for PATU8988S (from left to right): ***P = 0.0002, ***P = 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and ****P < 0.0001. f. Vinculin is used as a loading control. g. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. Statistical significance was measured with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Comparison between (–) and (+) doxycycline, ****P < 0.0001. Comparison between (–) doxycycline: vs 10 µM trametinib, P = ns (0.9997); 10 µM trametinib + doxycycline, P = ns (0.8226); 1 µM trametinib, P = ns (0.9997); 1 µM trametinib + doxycycline, P = ns (0.9994); 0.1 µM trametinib, P = ns (0.1904); 0.1 µM trametinib + doxycycline, P = ns (>0.9999). h. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. Statistical significance was measured with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Comparisons between groups (from left to right): ****P < 0.0001, ****P < 0.0001, ****P < 0.0001 and ****P < 0.0001. The experiments (e, g, h) were performed once with similar results on UPP1 displayed by the three cell lines. i. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. This blot was run on the same gel as Fig. 3n hence the first two columns (separated by a box) overlap between the two blots. j. Blots (c,i) are representative of two independent experiments; blot e experiment was done once. k. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. The statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined using limma package version 3.38.3 in R. l. Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 4 biologically independent samples per group. PATU8988S (comparison between cells cultured with and without trametinib in the absence of uridine: ****P < 0.0001, and with uridine supplementation: ****P < 0.0001); DANG (comparison between cells cultured with and without trametinib in the absence of uridine: **P = 0.0055, and with uridine supplementation: ***P = 0.0009); ASPC1 (comparison between cells cultured with and without trametinib in the absence of uridine: P = not significant, and with uridine supplementation: ****P = 0.0006). Data (b, e, g-h, l) shown as mean ± s.d.

To experimentally test the role of mutant KRAS on UPP1 expression, we first queried published microarray data from our doxycycline-inducible KRAS (iKras) mouse model of PDA33,34. Mutant KRAS promoted Upp1 expression in a subcutaneous xenograft model in vivo and iKras PDA cell lines in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Consistently, in vitro validation experiments in two additional, independent iKras cell lines confirmed doxycycline (via KRAS) induction of Upp1 (Fig. 3k,l).

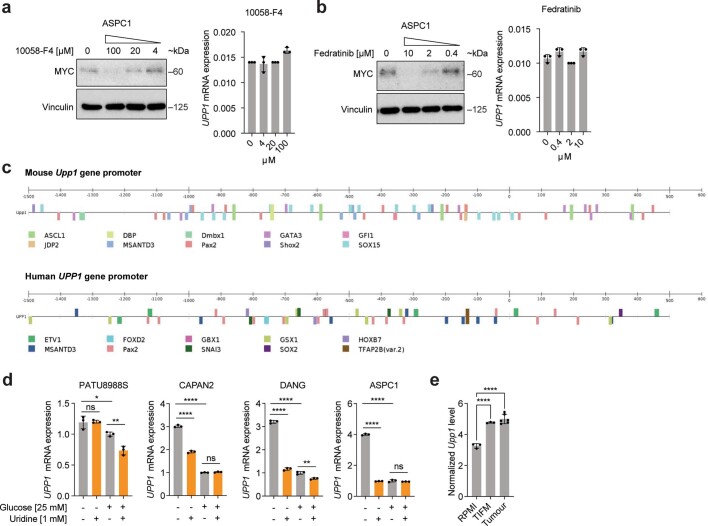

We previously showed that KRAS-mediated regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism in PDA occurs via mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling and MYC-dependent transcription34. In human and mouse cell lines, the pharmacological inhibition of MAPK reduced UPP1 transcript and protein, concurrent with the suppression of pERK (Fig. 3m,n and Extended Data Fig. 8c–j). MAPK inhibition also blocked the catabolism of uridine, as reflected by intracellular uridine accumulation, changes in a spectrum of other metabolites (Extended Data Fig. 8k), and a suppressed uridine-fuelled proliferation (Fig. 3o and Extended Data Fig. 8l). In contrast to the previous KRAS mechanism34, MYC inhibition did not alter UPP1 expression or appear among the transcription factors binding to the UPP1 promoter (Extended Data Fig. 9a–c), suggesting that MYC does not mediate KRAS regulation of UPP1 in PDA.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Regulation of UPP1 expression is independent of c-MYC.

a. Western blot showing Myc inhibition by 10058-F4 in ASPC1 cells after 24 h of culture. On the right: UPP1 mRNA expression determined by qPCR. kDa, unit for molecular weight. b. Western blot of Myc inhibition by Fedratinib in ASPC1 cells after 24 h of culture. On the right: UPP1 mRNA expression determined by qPCR. c. CiiDER analysis of transcription factor binding sites in the promoters of mouse and human UPP1. Myc binding sites were not detected. Details of analysis is in the “Methods” section. d. qPCR showing UPP1 expression upon uridine supplementation with or without basal glucose concentration in culture medium. e. RNA seq data showing the expression of Upp1 in sorted tumour cells and in KPC cells cultured in vitro in regular RPMI culture medium or tumour interstitial fluid medium (TIFM). Sample sizes: Tumour, n = 6, RPMI, n = 3 biologically independent cell samples, TIFM, n = 3 biologically independent cell samples. Normalized by log transformation [log2 (count +1)]. Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Comparison between RPMI and TIFM group, ****P < 0.0001 or tumour group, ****P < 0.0001. Statistics and reproducibility: a, qPCR, n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. b. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. Blots shown (a-b) are representative of two biological and technical replicate analyses with similar results. d. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group per cell line. Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. PATU8988S (comparison between no glucose and no glucose + 1 mM uridine: P = ns (0.994); comparison between cells cultured in glucose-containing medium with and without uridine: **P = 0.005); comparison between no glucose and glucose: *P = 0.0316; CAPAN2 (comparison between no glucose and no glucose + 1 mM uridine: ****P < 0.0001; comparison between cells cultured in glucose-containing medium with and without uridine: P = ns (0.8688); DANG (comparison between no glucose and no glucose + 1 mM uridine: ****P < 0.0001; comparison between cells cultured in glucose-containing medium with and without uridine: *P = 0.0021); ASPC1 (comparison between no glucose and no glucose + 1 mM uridine: ****P < 0.0001; comparison between cells cultured in glucose-containing medium with and without uridine: P = ns (0.5339). Comparison between no glucose and glucose for CAPAN2, DANG and ASPC1: ****P < 0.0001. Data (a,b,d,e) shown as mean ± s.d.

Nutrient availability modulates UPP1

Given that glucose availability influences the use of uridine-derived ribose, we hypothesized that a glucose-depleted microenvironment triggers PDA to upregulate UPP1 as a compensatory response. Indeed, the removal or reduction of glucose in the medium induced a strong increase in UPP1 expression (Fig. 3m–n and Extended Data Figs. 8c–e,h–j and 9d), which was attenuated in uridine-supplemented medium. Consistently, we found that Upp1 was strongly induced in a mouse tumour-derived cell line from the KPC model (p48-cre;LSL-KrasG12D;LSL-Trp53R172H) when cultured with TIF medium30 or implanted as orthotopic allografts, relative to cells cultured in routine medium with high glucose (Extended Data Fig. 9e). Thus, KRAS–MAPK signalling and a nutrient-deprived TME may both be responsible for high UPP1 expression.

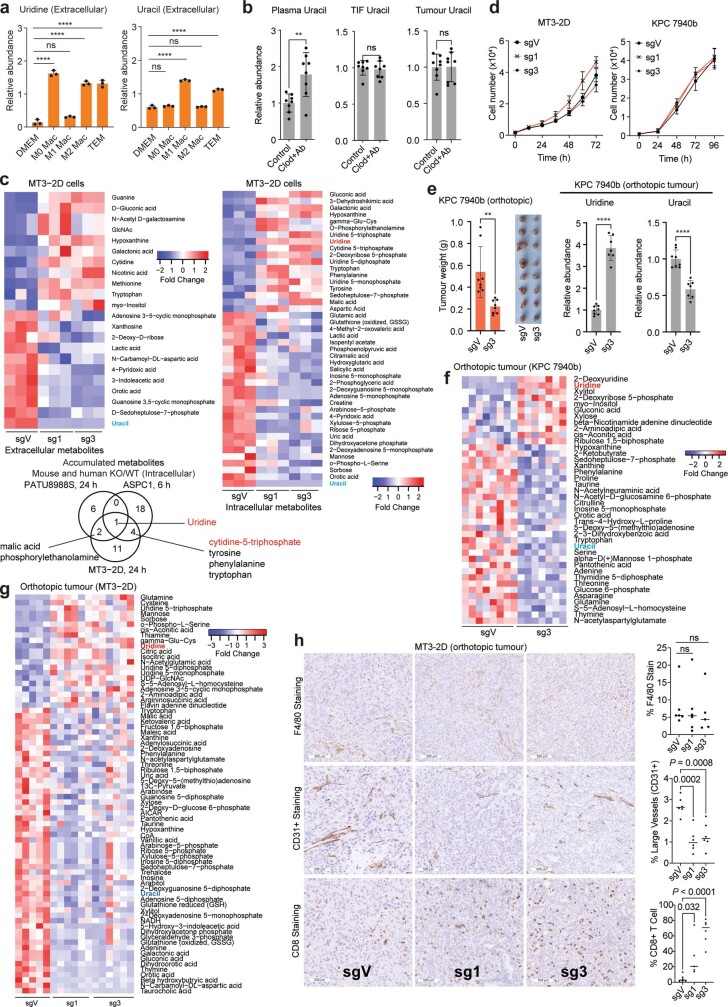

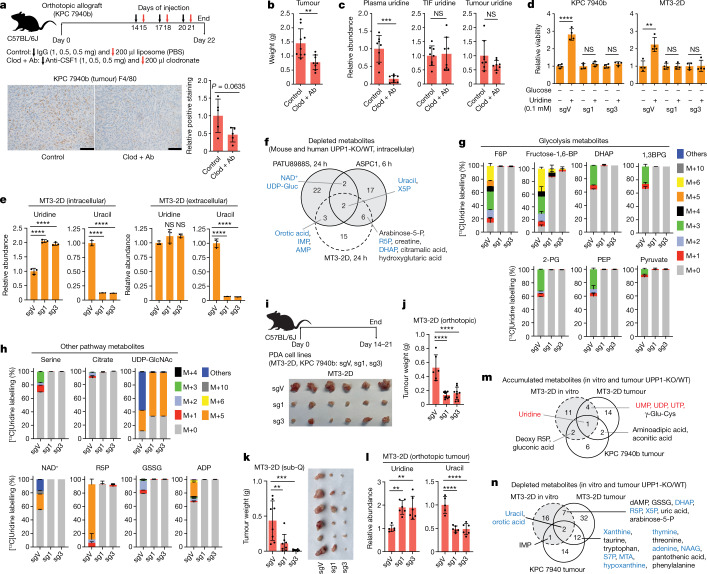

UPP1-KO blunts PDA tumour growth

Uridine concentration is reported to be around twofold higher in TIF than in plasma30. In looking for a cellular source supplying uridine to tumours, we observed from our previously generated dataset14 that macrophages release uridine and uracil in vitro when differentiated and polarized to a tumour-educated fate with PDA-conditioned medium (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Thus, we tested the role of tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) in supplying intratumoural uridine by depleting macrophages from mouse allograft tumours. To this end, we treated mice with a CSF1 antibody and clodronate liposome combination (Fig. 4a), which depletes TAMs and suppressed orthotopic tumour growth35,36 (Fig. 4a,b). We observed a reduction in the plasma uridine level by around eightfold upon macrophage depletion, concomitant with an increased plasma uracil level. However, uridine and uracil levels in the TIF and tumour were not altered (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 10b). This marked effect on plasma uridine levels following macrophage depletion indicates that macrophages may be important mediators of uridine production and/or release.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Knockout of UPP1 suppresses in vivo uridine catabolism and tumour growth.

a. LC-MS analysis of extracellular uridine and uracil in unpolarized bone marrow-derived macrophages (M0; 10 ng/mL M-CSF), those polarized toward an M1 fate (10 ng/mL LPS), an M2 fate (10 ng/mL murine IL-4), or a tumour-educated (TEM) phenotype with 75% PDA conditioned medium and compared to growth medium (DMEM). n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. Data was extracted from a previously published metabolomics14. b. Relative uracil abundance in plasma, tumour interstitial fluid (TIF), and bulk tumour from the experiment described in Fig. 4a, where Clod + Ab indicates the macrophage-depleted group. c. Extracellular (left) and intracellular (right) profiles of significantly changed (P < 0.05) metabolites from sgV and UPP1-KO (sg1, sg3) MT3-2D cells. The cells were cultured in medium with 1 mM uridine and no glucose for 24 h, as determined by metabolomics. d. Proliferation assay of sgVector (sgV) and UPP1-KO (sg1, sg3) MT3-2D and KPC 7940b mouse PDA cell lines cultured over 72 h and 96 h, respectively, in normal growth medium with 10% dialyzed FBS. e. Tumour weight and photograph and bulk tumour uridine and uracil from the orthotopic implantation of sgV and UPP1-KO (sg3) KPC 7940b cell lines into C57BL/6J mice; see Fig. 4i for experimental details. f,g. Tumour metabolomics profile indicating statistically significant (P < 0.05) metabolites from sgV and UPP1-KO f) KPC 7940b and g) MT3-2D-derived tumours. h. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of macrophages (F4/80), large blood vessels (CD31+), and cytotoxic cells (CD8) using tissue sections of MT3-2D orthotopic tumours. Micrographs are representative of 10 fields per image obtained per experiment group. Scale bar 500 µm. On the right is the respective quantification of each IHC stain. Statistics and reproducibility: a, Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Uridine – DMEM: comparison to M0 Mac group ****P < 0.0001; to M1 Mac group P = ns (0.0758); to M2 Mac group ****P < 0.0001; to TEM group ****P < 0.0001. Uracil – DMEM: comparison to M0 Mac P=ns (0.5476); to M1 Mac group ****P < 0.0001; to M2 Mac group P=ns (0.9894); to TEM group ****P < 0.0001. b. Statistical significance was measured using a two-tailed unpaired t-test – Plasma uracil **P = 0.0045 with n = 8 biologically independent replicates in both groups, TIF uracil P = ns (0.6872) with n = 8 biologically independent replicates in both groups– and using Welch’s t-test P=ns (0.9682) with n = 8 biologically independent replicates in both groups. c. n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. Color scale denotes fold change. Below: Venn diagram showing overlapping metabolites that accumulated in both human (PATU8988S and ASPC1) and mouse (MT3-2D) cell lines upon UPP1 knockout. d. MT3-2D, n = 4 and KPC 7940b, n = 3 biologically independent samples per group. e. n = 8 biologically independent samples per group. Statistical significance measured using two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, **P = 0.0059. On the right: bulk tumour uridine and uracil as measured using metabolomics. Sample size: sgV = 8, sg3 = 7. Uridine: ****P < 0.0001. Uracil: ****P < 0.0001. f,g. Sample size: KPC 7940b sgV = 8 and sg3 = 7, MT3-2D sgV = 5 sg1 = 6 and sg3 = 6 biologically independent samples from mice with orthotopic pancreatic tumours. h. Sample size: F4/80 sgV = 7, sg1 = 6, sg3 = 5; CD31 n = 6 per group; CD8+ sgV = 6, sg1 = 5, sg3 = 6, all biologically independent samples per group. Statistical significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Comparison between % F4/80 sgV and sg1 P = ns (>0.9968), and sgV and sg3 P = ns (0.9583). Data (a, b, d, e) shown as mean ± s.d; horizontal bars in h represent mean value.

Fig. 4. UPP1-KO impairs the growth of orthotopic pancreatic tumour allografts.

a, Schematic of macrophage depletion (top) and validation by immunohistochemistry with F4/80 monoclonal antibody (bottom). Scale bars, 100 μm. Clod + Ab denotes anti-mouse CSF1 antibody and clodronate liposome. b, Tumour weight from control and macrophage-depleted mice at end point. c, Relative plasma, TIF and whole-tumour uridine levels in samples from the control and macrophage-depleted groups, measured by LC–MS. d, CellTiter Glo assay indicating relative viability (via ATP) of UPP1-KO (sg1 and sg3) and non-targeting control vector (sgV) mouse PDA cells. e, Relative intracellular and extracellular uridine and uracil levels in the control and UPP1-KO MT3-2D mouse PDA cell lines after 1 mM uridine supplementation, as determined by LC–MS. f, Venn diagram showing metabolites depleted in vitro upon UPP1-KO in the human (PATU8988S and ASPC1) and mouse (MT3-2D) PDA cell lines, determined by LC–MS. Metabolites in blue are those from the glycolysis, nucleotide biosynthesis or pentose phosphate pathways. Arabinose-5-P, arabinose-5-phosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; UDP-Gluc, uridine diphosphate-glucose; X5P, xylulose 5-phosphate. g,h, Stable isotope tracing showing mass isotopologue distribution of 1 mM [13C5]uridine-derived carbon in metabolites from glycolysis (g) and other pathways (h) in the MT3-2D cells after 6 h culture. 1,3BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglcerate; GSSG, oxidized glutathione. i, Top, schematic of tumour studies. Bottom, representative photograph of tumours collected from mice orthotopically implanted with the control vector (sgV) or UPP1-KO (sg1, sg3) MT3-2D cells. j, Tumour weight at end point of C57BL/6J mice orthotopically implanted with the MT3-2D cells. k, Weight and photograph of tumours collected at the end point after subcutaneous implantation of MT3-2D cells into the left and right flanks of C57BL/6J mice. l, Relative tumour uridine and uracil abundance in the orthotopic tumour samples described in i,j, as determined by LC–MS. m,n, Venn diagram showing metabolites commonly accumulated (m) and depleted (n) in UPP1-KO tumours implanted in mice and UPP1-KO cultured cells versus the wild type, as determined by LC–MS. m, Metabolites in red are associated with nucleotide biosynthesis. n, Metabolites in blue are associated with glycolysis, nucleotide biosynthesis or PPP. MTA, 5′-methylthioadenosine; NAAG, N-acetylaspartylglutamic acid; S7P, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate. See Methods ‘Statistics and reproducibility’ section for additional information.

To determine whether UPP1 supports tumour growth in vivo, we generated two independent models of UPP1-KO in the syngeneic mouse pancreatic cancer lines MT3-2D and KPC 7940b. Two single guide RNA (sgRNA) constructs targeting Upp1 (sg1 and sg3) were compared to a vector control (sgV). We confirmed that glucose-deprived mouse UPP1-KO cells were not rescued by uridine in vitro (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, metabolomics profiling confirmed intracellular uridine accumulation and a reduced intracellular and extracellular uracil (Fig. 4e)—consistent with a blocked uridine catabolism. These were accompanied by a change in a spectrum of other metabolites that were also altered in the human UPP1-KO cell lines (Fig. 4f and Extended Data Fig. 10c). Finally, isotope tracing of uridine ribose-derived carbon illustrated conclusively that UPP1-KO in the mouse lines restricted the use of uridine to fuel central carbon metabolism (Fig. 4g,h). This battery of metabolic assays confirmed a successful UPP1-KO in lieu of a mouse UPP1 antibody. Notably, the UPP1-KO cells did not differ from controls in terms of proliferation under optimal culture where glucose is present (Extended Data Fig. 10d).

We orthotopically implanted these two mouse lines and the corresponding UPP1-KO lines into the pancreas of syngeneic hosts and assessed tumour weight at end point (Fig. 4i). In both lines, contrary to the lack of a proliferative defect in vitro, we observed a markedly reduced tumour growth following UPP1-KO (Fig. 4j and Extended Data Fig. 10e). Similar results were also reproduced in an immunocompetent subcutaneous model using the MT3-2D cell lines (Fig. 4k). Metabolomic profiling of the orthotopic tumours revealed an increase in tumoural uridine and a drop in uracil in the UPP1-KO tumours as well as a profound change in the metabolome relative to vector controls (Fig. 4l–n and Extended Data Fig. 10f,g). In addition, compared with in vitro data, we observed the accumulation of a similar collection of metabolites (Fig. 4m) and a strong depletion of uracil, components of PPP, glycolysis and nucleotide metabolism (Fig. 4n).

The marked anti-tumour effect of UPP1-KO prompted us to look for changes in the in vivo microenvironment. Histological analysis of F4/80 staining revealed no differences in macrophage content between UPP1-KO and vector control tumours. However, the UPP1-KO tumours had lower vessel density (CD31) and more anti-tumour T cell infiltration (CD8 T cells) (Extended Data Fig. 10h). Together, our data indicate that UPP1 and uridine are important in PDA growth. The contrast between the in vitro and in vivo growth phenotype further highlights the role of nutrient availability, as well as the potential involvement of the TME and immune cell subsets in influencing the necessity of UPP1 in vivo.

Discussion

The metabolic features of PDA drive disease aggression and therapeutic resistance and present new opportunities for therapy2,6. Despite this, the range of nutrients used by PDA cells is poorly understood. We addressed this problem by applying high-throughput in vitro nutrient screening and found that under glucose-restricted conditions and KRAS–MAPK signalling activation, uridine serves as a nutrient source for PDA cells. This aligns with previous studies, where uridine rescued glucose deprivation-induced stress in astrocytes and neurons20,21,23. Indeed, others have shown that the uridine-mediated rescue is UPP1-dependent and induced by glucose availability, and it was proposed that UPP1 functions in this capacity to support bioenergetics by providing nucleotides20. We show that the uridine ribose ring fuels both energetic and anabolic metabolism in PDA cells. We also found that in addition to KRAS–MAPK, uridine utilization axis is regulated by a yet unknown rheostat sensing the upstream availability of glucose and/or uridine. These are newly identified regulators of UPP1, adding to p53 regulation37. Exploration of these regulatory pathways in PDA and other cancers may hold translational promise.

Nutrients in the TME can be derived from serum or the various cell types that make up the tumour. Although discovery methods involving conditioned medium and metabolomics are high-throughput, they tend not to capture the complex metabolic interactions of the TME. Biolog assays provide an unbiased approach to assess metabolic fuel utilization. Here we used this system to first obtain source-agnostic information about the nutrients utilized by PDA cells, before conducting a targeted analysis of potential sources providing exogenous uridine to tumours. We observed evidence of uridine enrichment in the TIF of mouse pancreatic tumours, tumour consumption of plasma-derived uridine by in vivo isotope tracing, reduction of the plasma uridine pool upon whole-body macrophage depletion, and in vitro micromolar release of uridine from naive macrophages and TAMs. Together, these findings illustrate the complexity of nutrient availability in the TME and suggest a model in which cells inside and outside PDA tumours fuel cancer metabolism with uridine.

There is a growing appreciation for the importance of nucleosides in cancer, including inosine, thymidine and deoxycytidine6,14,38,39. Inosine is consumed in melanomas by both cancer and CD8+ effector T cells40. The upregulation of nucleoside usage under nutrient deprivation40–42, especially in immune and PDA cells, supports the idea that metabolic competition contributes to immunosuppression and tumour progression. Along these lines, we show that UPP1-KO in an orthotopic syngeneic model of PDA severely blunts tumour growth, thus the UPP1–uridine scavenging axis is important for PDA cells. RNA is another important source of uridine for glucose-starved cells and may be relevant for PDA cells, which readily scavenge intracellular (that is, autophagy) and extracellular biomolecules to fuel metabolism5. There are also several non-tumoural cell types that utilize uridine for various purposes20,21,23,43, and this complexity is a promising area for future study. Collectively, our data identify the uridine–UPP1 axis as a driver of compensatory metabolism and support the therapeutic tractability of nucleoside metabolism in solid tumours.

Methods

Cell culture

The PDA cell lines A549, HT1080, HCT116 and U2OS and human pancreatic nestin-expressing cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) or the German Collection of Microorganisms (DSMZ). The human pancreatic stellate cells (hPSC) and mouse PDA cell lines KPC 7940b and MT3-2D were provided under a material transfer agreement by R. Hwang, G. Beatty and D. Tuveson, respectively. iKras cell lines A9993 and iKRAS 9805 were derived as described33. The identity of cell lines was confirmed by STR profiling, and lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma using MycoAlert (Lonza, LT07-318). For routine propagation, unless otherwise indicated, all cell lines were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Gibco, 11965092) supplemented with 10% FBS (Corning, 35-010-CV) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. PBS (Gibco, 10010023) was used for cell washing steps unless otherwise indicated. For treatments, the following inhibitors were used: MYC, fedratinib (MedChemExpress, HY-10409) and 10058-F4 (Cayman Chemical, 15929); MEK1, trametinib (Selleckchem, S2673).

Biolog metabolic assay

In the initial phenotypic screen, the 22 cell lines were grown in 96-well PM-M1 and PM-M2 plates (Biolog, 13101 and 13102). The assay was set up such that one well was used per test metabolite substrate, accompanied by three replicates of positive (glucose) and negative (blank) control wells. The RMA from substrate catabolism in the cells was measured using Biolog Redox Dye Mix MB. In brief, the cell lines were counted, and their viability assessed using Trypan Blue Dye (Invitrogen, T10282). The cells were then washed two times with Biolog Inoculating fluid IF-M1 (Biolog, 72301) to remove residual culture medium. Then, a cell suspension containing 20,000 cells per 50 µl was prepared in Biolog IF-M1 containing 0.3 mM glutamine and 5% dialysed FBS (dFBS) (Hyclone GE Life Sciences, SH30079.01) and plated into PM-M1 and PM-M2 96-well plates at 50 µl per well. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, after which 10 µl Biolog Redox Dye Mix MB (Biolog, 74352) was added to each well. Plates were sealed to prevent the leakage of CO2. The reduction of the dye over time was measured as absorbance (A590-A750) using the OmniLog PM-M instrument (Biolog, 93171) for 74.5 h at 15 min intervals. To account for proliferation or cell number in the Biolog screening assay, CyQUANT was used for normalization.

The data were processed and normalized using the opm package45 version 1.3.77 in the R statistical programming tool. After removing CFPAC1 (atypically high signal across the plate), the maximum metabolic activity per cell line was taken as its main readout for substrate avidity (Extended Data Fig. 1a) and normalized by subtracting the median negative control signal for a given cell line from all other values for that cell line. Heat map visualization of the data was plotted using heatmap2 and ComplexHeatmap packages in R.

Correlation of Biolog metabolites to gene expression of enzymes

High-confidence metabolites from the Biolog screening assay were correlated (Spearman Correlation) to gene expression data for enzymes associated with metabolite usage. Genes with high correlation co-efficient to a given metabolite were chosen for further analysis.

NADH assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 10,000 cells per well directly into the indicated medium conditions. Following the incubation period at 37 °C and 5% CO2 (24, 48 or 72 h), MTT (Thermo Scientific, L1193903) was added directly to the wells containing medium. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 h, after which the medium and MTT reagent were carefully removed. Next, to each well, 50 μl of DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, D2650) was added followed by 5 min incubation at room temperature before measuring absorbance at 570 nm.

CyQUANT proliferation assay

Cells were seeded at 20,000 cells per well for the screening study or 2,000 cells per well for proliferation assays in growth medium in 96-well plates (Corning, 3603). For proliferation assays, the culture medium was removed the next day, followed by a gentle 1× wash with PBS. Treatment medium was then applied, and the cells incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until they reached ~70% confluence. Medium was then carefully aspirated, and the plate with cells attached was moved to −80 °C for at least 24 h to ensure complete cell lysis. To prepare the lysis buffer and DNA dye, CyQUANT Cell Lysis Buffer and CyQUANT GR dye (Invitrogen, C7026) were diluted in water at 1:20 and 1:400, respectively. The frozen cells were then thawed and 100 µl of the lysis buffer was added to each well. Thereafter the plate was covered to prevent light from inactivating the GR dye and was placed on an orbital shaker for 5 min before measurement. Fluorescence from each well, indicating GR dye binding to DNA, was then measured utilizing a SpectraMax M3 Microplate Reader with SoftMax Pro 5.4.2 software at an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm.

ATP-based viability assay

Cells were seeded in quadruplicates at a density of 2,500–5000 cells in 100 μl DMEM per well of the white walled 96-well plates (Corning/Costar, 3917). Next day, the medium was aspirated, each well was washed with 200 μl PBS after which treatment medium was introduced. At the end of the experiment duration (48 or 72 h), relative proliferation was determined with CellTiter-Glo 2.0 Cell Viability Assay Kit (Promega, G9243) and the luminescence quantified using a SpectraMax M3 Microplate Reader.

Live-cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 1,000 cells per well in 100 µl of growth medium and incubated overnight at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After 24 h, medium was changed, and the cells were incubated for a further 72 h during which cell proliferation was determined by live-cell imaging on a BioSpa Cytation.

UPP1 CRISPR–Cas9 knockout

The expression vector pspCas9(BB)-2A-Puro (PX459) used to generate the UPP1 CRISPR–Cas9 constructs was obtained from Addgene (Plasmid 48139). The plasmid was cut using the restriction enzyme BbsI followed by the insertion of human or mouse uridine phosphorylase 1 sgRNA sequences (Supplementary Table 4), as previously described46. The human and mouse sequences were obtained from the Genome-Scale CRISPR Knock-Out (GeCKO) library. For transfection, the human or mouse PDA cells were seeded at 150,000 cells per well in a 6-well plate a day earlier. The cells were transfected with 1 μg of plasmid pSpCas9-UPP1 using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (Invitrogen, L3000001) according to manufacturer’s instruction. After 24 h, the selection of successfully transfected cells was commenced by culturing the cells with 0.3 mg ml−1 puromycin in DMEM. The puromycin-containing medium was replaced every two days until selection was complete, as indicated by the death and detachment of all non-transfected cells. Thereafter, the successfully transfected cell lines were expanded and clonally selected after serial dilution.

siRNA experiments

Approximately 5 × 105 ASPC1 cells were seeded per 6-cm dish for 24 h in the growth medium. On day 2, medium was changed and the respective SMARTpool siRNA-containing medium was added. siRNA transfection was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (ThermoFischer Scientific, 13778075) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the transfection, Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (31985-062) was used and siRNAs were added at a concentration of 20 nM. Cells were transfected for 48 h after which the cells were trypsinized, counted, and plated for MTT assay. The remaining cells were pelleted, and RNA was extracted for qPCR. The siRNAs used were as follows: non-targeting control (D-001810-01-05), SMARTpool ON-TARGETplus Human PGM2 (55276) (L-020785-01-0005), ON-TARGETplus Human UCK1 (83549) (L-004062-00-0005) and ON-TARGETplus Human UCK2 (7371) (L-005077-00-0005).

Reverse transcription with qPCR