Abstract

This review discusses research conducted globally between March 2020 and March 2023 examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent social functioning, including their lifestyle, extracurricular activities, family environment, peer environment, and social skills. Research highlights the widespread impact, with largely negative effects. However, a handful of studies support improved quality of relationships for some young people. Study findings underscore the importance of technology for fostering social communication and connectedness during periods of isolation and quarantine. Most studies specifically examining social skills were cross-sectional and conducted in clinical populations, such as autistic or socially anxious youth. As such, it is critical that ongoing research examines the long-term social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and ways to promote meaningful social connectedness via virtual interactions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Social development, Adolescents, Isolation, Quarantine

Introduction

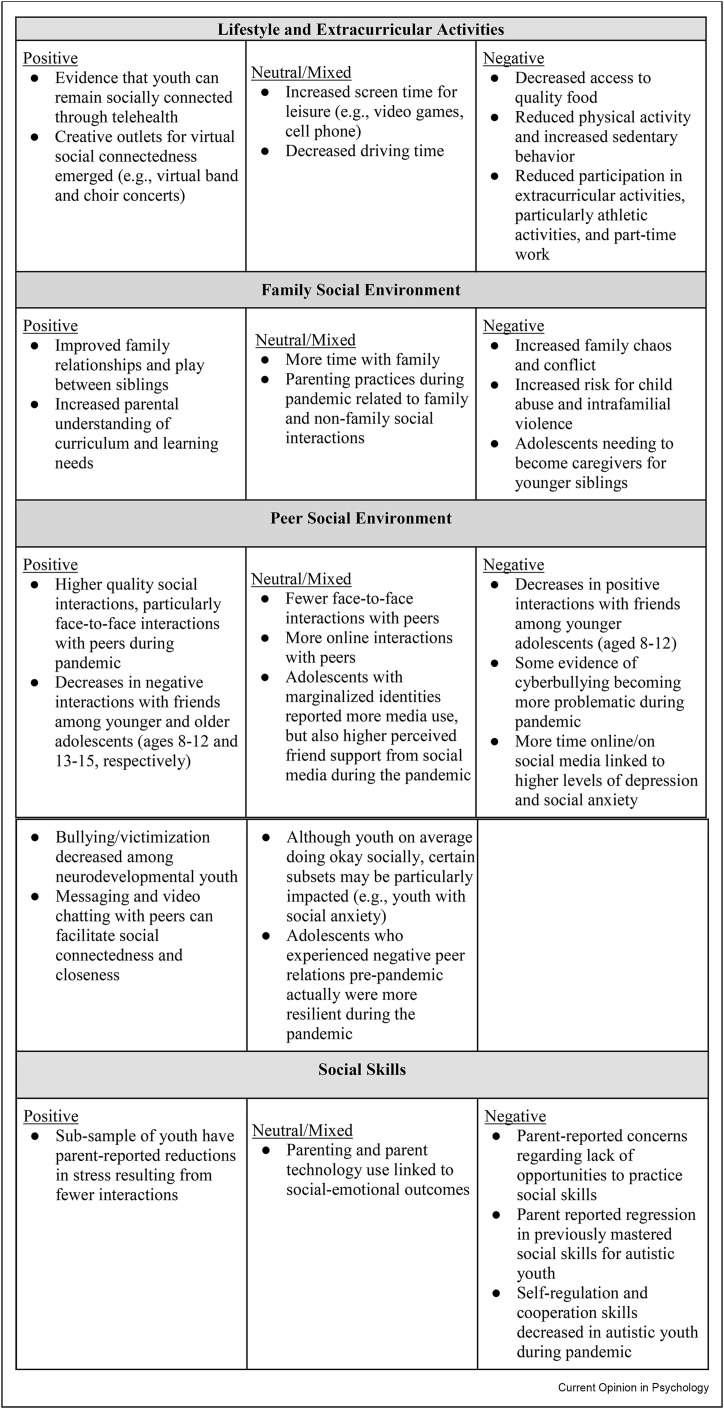

The COVID-19 pandemic, and its associated quarantine and isolation measures, resulted in significant disruptions to in-person social interactions, which has placed adolescents at risk for negative social development outcomes [1]. In fact, it has been suggested that adolescents are more affected than adults by the social impact of the pandemic [2], and one of the most frequently endorsed challenges by parents during the pandemic includes the lack of social interaction for their adolescents [3]. This social impact extends to adolescent well-being. Specifically, research suggests that social isolation and loneliness were associated with increased anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation among youth [4], and that less in-person and digital socialization, more social isolation, and less social support were associated with greater psychopathology during the pandemic, controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms [5]. The current article reviews COVID-19-related research published globally between March 2020 and March 2023 and discusses the impact of the pandemic on the lifestyle, extracurricular activities, family social environment, peer social environment, and social skills of adolescents.1 Results are summarized below and in Figure 1 . We end our review by providing suggestions for how to support adolescents emerging out of the current pandemic and during future periods of quarantine and isolation.

Figure 1.

Summary of benefits and concerns noted in existing research.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on lifestyle and extracurricular activities

The overall lifestyle of adolescents has been drastically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, research suggests they had decreased access to quality food, increased fast food consumption, reduced physical activity, increased sedentary behavior, reduced driving days/miles driven, and increased screen time for leisure [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11], with some evidence that adolescents were more impacted than children [8] and adults [9]. Such lifestyle changes have been linked to adolescent mental health outcomes. For example, excessive media exposure during the COVID-19 pandemic has been linked to anxiety symptoms [12], and low levels of physical activity were associated with higher levels of mood disturbance [10]. However, not all studies found an association between social technology use and adolescent well-being [13,14]. This may be because adolescents more frequently checked social media, used technology before bed, and engaged in problematic internet use, but also were more likely to engage positively with social and use online communication for social support [13], with positive online experiences mitigating feelings of loneliness and stress [14].

Participation in extracurricular activities and part-time work was also significantly reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially the first year of the pandemic [15,16]. Notably, artistic activities such as music were the least impacted extracurricular activities, followed by participation in scout, religious/spiritual, academic (e.g., science), and athletic activities. Collective sports (e.g., soccer, basketball, baseball) were the most impacted, with an almost 90% reduction [15].

Limited research during the COVID-19 pandemic explored the use of virtual interactions to support social connectedness and engagement in extracurricular activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. An example of one such program, a telehealth school-based prevention program for newcomer Latine immigrant youth found that despite moving to a telehealth model, youth reported feeling socially connected to each other through the program [17]. Despite limited research on the topic, there were countless examples of adolescents coming together to conduct virtual choir concerts (see North Allegheny Virtual Choir Baba Yetu, for an example) or band performances (see Woodbury HS Virtual Band - “The Mandalorian”, for an example) when classes were moved virtually in March 2020 in the United States. It is likely that such efforts helped foster social connectedness and improve student well-being during times of isolation and quarantine.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family social environment

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in adolescents spending significantly more time with family members, with such time providing both benefits and concerns. Specifically, increased family time and increased parental understanding of youth learning needs were cited as two of the main benefits of the COVID-19 pandemic by parents [3]. There is also some evidence of improved quality of family relationships and play between siblings, particularly for older adolescents [18, 19∗, 20]. However, research also highlights challenges in this area. Some adolescents became caregivers when parents were unavailable, with such experiences disproportionately affecting low income families and Black and Latine communities [20]. Despite some studies finding improved family relationships, other research suggests that the pandemic has resulted in more negative relationship quality with parents, increased family chaos and conflict, as well as risk for child abuse and exposure to intrafamilial violence and intimate partner violence [2,18,21,22]. Of note, adolescent relationship quality with parents was directly related to their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [18]. Additionally, the pandemic has resulted in decreased parent–child intimacy, sibling intimacy, and sibling disclosure for some young people [22].

Importantly, research has sought to explore factors that may predict risk versus resilience among families during the pandemic. For example, even though family income was not related to change in family organization (e.g., home is calm), families of lower socioeconomic statuses had lower family organization at both timepoints [22]. Additionally, social isolation during the first two weeks of the pandemic was associated with an increase in parents spanking or hitting their children [23]. In contrast, practicing collective hobbies with family members and assisting each other with household chores strengthened family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic [24]. Interestingly, parenting practices during the pandemic related to both family and non-family social interactions [25], highlighting the important role of parents and the family for adolescent social functioning.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on peer relationships

As would be expected, peer relationships were also impacted for many adolescents. In one study, 682 families in the United States from five Midwestern states with two adolescent-aged children (89% girls; Mage = 16 years) reported engaging in fewer in-person/face-to-face interactions with peers and more online interactions [26]. Despite this, they actually reported higher quality of social interactions overall, and more specifically, a higher quality of face-to-face interactions with peers during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic. Authors speculated that this finding may have resulted from adolescents being more selective in the peers that they interacted with (e.g., closer friends, romantic partners), underscoring the importance of high-quality social interactions rather than just the number of socialization opportunities. Interestingly, research suggests that adolescents who experienced negative peer relations pre-pandemic actually were more resilient during the pandemic [35].

However, research is mixed regarding observed peer social dynamics and social impacts during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Gadassi Polack and colleagues [19] found that in a sample of 139 youth ages 8–15 years in the US, younger adolescents experienced significant decreases in negative and positive interactions with friends, whereas older adolescents only experienced significant decreases in negative ones. With regard to bullying, some research found reductions in bullying/victimization among 49 children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders in rural Appalachia (US) ages 6–17 years and 272 adolescents in the Midwestern US aged 10–15 years from a community sample [27,28], whereas other research found that a third of adolescents aged 11–17 years in the US (N = 452; 55% female) indicated that cyberbullying became more problematic during the pandemic [29].

Similarly, findings regarding the role of virtual social interactions were mixed. For example, Canadian adolescents (N = 1054) who reported spending more time virtually with peers reported higher levels of depression [30], and Lebanese adolescents (N = 178) who reported spending more time on social media during the pandemic had more social anxiety symptoms [31]. However, studies examining the specificity of these virtual social interactions have actually uncovered that messaging and video chatting with peers facilitated social connectedness and closeness during social isolation due to COVID-19, whereas social media did not [31,32]. Therefore, it's important for researchers and families to distinguish between types of virtual social interactions. More passive social technologies, like social media, are not necessarily dependent upon strong friendships and therefore, are less likely to be indices of friendships/peer networks.

Certain subsets of youth may have had unique social experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, certain clinical populations, such as youth with social anxiety, were particularly likely to experience loneliness/social isolation, with avoidance behaviors in social anxiety being reinforced by social distancing [33]. Additionally, adolescents with marginalized identities (e.g., gender nonbinary, LGBTQ-identifying, and Latine or Asian adolescents) reported higher perceived friend support from social media during the pandemic [34]. Greater impacts were also evident for youth from lower socioeconomic status families: they were more impacted in terms of increased social anxiety [31] and likelihood to be working and thus exposed to the coronavirus [34].

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social skills

Early in the pandemic, it was speculated that there would be significant social impact for youth [2,36]. Although there is not widespread evidence of such negative impact, research highlights a multitude of factors that contribute to the impact of the pandemic on youth social skills. First, masking may have impacted children's, particularly preschoolers, ability to read emotions and develop social skills (e.g., trust attributions) from facial expressions [37]; however, it appears that this impact was not present for adolescents [38]. At the same time, youth with diagnosed disorders characterized by social-communication deficits, such as neurodevelopmental disorders, may be particularly impacted due to lack of opportunity to practice. For example, in a qualitative study, parents reported concerns regarding lack of opportunities to practice social skills, with regression in previously mastered social skills being reported for autistic children and adolescents aged 3–18 years [39]. In this vein, self-regulation and cooperation skills of autistic children also decreased during the pandemic [40]. However, a small subset of parents of autistic youth indicated that reduced social interactions resulted in less stress for their child [39].

Finally, parents' functioning during the pandemic likely had direct and indirect impacts on children's social functioning during this time. For example, parenting practices and parent technology use have been linked to youth social-emotional functioning during pandemic such that unsupportive parenting practices were linked to worse youth adjustment and more emotion dysregulation [41] and parent use of technology was linked to worse youth social competence [42]. Collectively these findings suggest that social skills were impacted for at least a portion of children and adolescents, and various factors at the child and family level may explain differences during periods of quarantine and social distancing.

Conclusions and recommendations for future times of quarantine and isolation

Social connection and belongingness with close others are of crucial importance for adaptive development [43]. Social interactions are most valuable when they are facilitating personally meaningful interactions with highly valued social supports. For example, a qualitative study with sexual minority adolescents identified that youth engaged primarily in five self-care practices: relationships, routines, body and mind, rest and reset, and tuning out, with relationships (i.e., spending time with others) being identified as the most important form of self-care [46]. Of note, social interactions for today's youth often include virtual interactions [44]. Research during the pandemic suggests that texting and video chatting with peers can facilitate social connectedness and closeness [31]. Such online communication has likely served as a valuable placeholder when face-to-face interactions were restricted, with this possibly being one of the reasons why so many adolescents have remained resilient throughout the pandemic. For example, Dvorsky and colleagues [45] found that coping with the COVID-19 pandemic by using technology (e.g., talking with online community over video games) and/or social engagement (e.g., talking with friends, playing board games with family) buffered against the negative impacts on adolescent well-being. It is unclear whether it is the engagement in interactive social technologies that drives stronger friendship quality and social connections [26] or if it is that youth with a solid social network and social support more generally feel more socially connected and therefore engage in more frequent social technology use. Regardless, current findings from the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that it will be important to emphasize continued efforts to build meaningful social connections proactively and maintain these during future periods of isolation/quarantine, likely by leveraging technology. Schools could consider smaller virtual groups rather than large virtual classrooms, including periods for brief social-emotional learning programming or academic projects that can facilitate social connectedness, shared experiences, and belongingness, as well as providing an opportunity to socialize with new peers.

Additionally, we would argue that beyond peer connectedness, it is critical to focus on facilitating positive family social connections during times of isolation/quarantine, since that is who adolescents are interacting with most. Parents play a key role in facilitating social support, building social functioning, and improving well-being in youth [18,25]. Findings from this review underscore that the role of parents and siblings shifted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and parents in particular had to fulfill multiple roles. It is critical for the field to continue to explore how the quality and changes in parent–child relationships may impact youth's broader social functioning and well-being in the long-term.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Rosanna Breaux has received grant funding from the Society for Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, the Society for a Science of Clinical Psychology, 4-VA, the American Psychological Association, and Virginia Tech. Melissa Dvorsky has received grant funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; K23MH122839). Stephen Becker has received grant funding from the Institute of Education Sciences (IES; U.S. Department of Education; R305A200028), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01MH122415), and the Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation (CCRF), and has received book honoraria from Guilford Press, editorial honoraria as Joint Editor of JCPP Advances, grant review panel honoraria from the IES, and educational seminar speaking fees and CE course royalties from J&K Seminars and from PESI, Inc.

This issue or review comes from Generation COVID: Coming of Age Amid the Pandemic

Edited by Gabriel Velez and Camelia Hostinar.

Footnotes

To be included in the study, the sample had to include at least some youth aged 10–19 years.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Cameron L., Tenenbaum H.R. Lessons from developmental science to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 restrictions on social development. Group Process Intergr Relat. 2021;24:231–236. doi: 10.1177/1368430220984236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unni J.C. Social effects of Covid-19 pandemic on children in India. Indian J Pract Pediatr. 2020;22:102–104. https://www.ijpp.in/Files/2020/ver2/Social-effects-of-COVID-19.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A.K., Breaux R., Sciberras E., et al. A preliminary examination of key strategies, challenges, and benefits of remote learning expressed by parents during the covid-19 pandemic. Sch Psychol. 2022;37:147–159. doi: 10.1037/spq0000465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loades M.E., Chatburn E., Higson-Sweeney N., et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of covid-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodman A.M., Rosen M.L., Kasparek S.W., et al. Social Experiences and youth psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1017/s0954579422001250. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Figueiredo C.S., Sandre P.C., Portugal L.C., et al. Covid-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents' mental health: biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;106 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munasinghe S., Sperandei S., Freebairn L., et al. The impact of physical distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic on health and well-being among Australian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossi L., Behme N., Breuer C. Physical activity of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic—a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scapaticci S., Neri C.R., Marseglia G.L., Staiano A., Chiarelli F., Verduci E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on lifestyle behaviors in children and adolescents: an international overview. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48 doi: 10.1186/s13052-022-01211-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stavrinos D., McManus B., Mrug S., et al. Adolescent driving behavior before and during restrictions related to covid-19. Accid Anal Prev. 2020;144 doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2020.105686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X., Zhu W., Kang S., Qiu L., Lu Z., Sun Y. Association between physical activity and mood states of children and adolescents in social isolation during the COVID-19 epidemic. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17:7666. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panchal U., Salazar de Pablo G., Franco M., et al. The impact of covid-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charmaraman L., Lynch A.D., Richer A.M., Zhai E. Examining early adolescent positive and negative social technology behaviors and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. TMB. 2022;3 doi: 10.1037/tmb0000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marciano L., Ostroumova M., Schulz P.J., Camerini A.-L. Digital Media use and adolescents' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.793868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilari B., Cho E., Li J., Bautista A. Perceptions of parenting, parent-child activities and children's extracurricular activities in times of covid-19. J Child Fam Stud. 2021;31:409–420. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-02171-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jolliff A., Zhao Q., Eickhoff J., Moreno M. Depression, anxiety, and daily activity among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Formative Research. 2021;5 doi: 10.2196/30702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez W., Patel S.G., Contreras S., Baquero-Devis T., Bouche V., Birman D. “We could see our real selves:” the covid-19 syndemic and the transition to telehealth for a school-based prevention program for newcomer Latinx Immigrant Youth. J. Community Psychol. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jcop.22825. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campione-Barr N., Rote W., Killoren S.E., Rose A.J. Adolescent adjustment during Covid-19: the role of close relationships and Covid-19-related stress. J Res Adolesc. 2021;31:608–622. doi: 10.1111/jora.12647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadassi Polack R., Sened H., Aubé S., Zhang A., Joormann J., Kober H. Connections during crisis: adolescents' social dynamics and mental health during COVID-19. Dev Psychol. 2021;57:1633–1647. doi: 10.1037/dev0001211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis F. Schools Week; 2022. How to ease the transition back to school for young carers.https://generations.asaging.org/youth-caregivers-and-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassinat J.R., Whiteman S.D., Serang S., et al. Changes in family chaos and family relationships during the covid-19 pandemic: evidence from a longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 2021;57:1597–1610. doi: 10.1037/dev0001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.J., Ward K.P., Lee J.Y., Rodriguez C.M. Parental social isolation and child maltreatment risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2021;37:813–824. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed D., Buheji M., Merza Fardan S. Re-emphasising the future family role in ‘care economy’ as a result of covid-19 pandemic spillovers. Am J Econ. 2020;10:332–338. doi: 10.5923/j.economics.20201006.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achterhof R., Kirtley O.J., Schneider M., et al. Daily-life social experiences as a potential mediator of the relationship between parenting and psychopathology in adolescence. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.697127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achterhof R., Myin-Germeys I., Bamps E., et al. 2021. Covid-19-related changes in adolescents' daily-life social interactions and psychopathology symptoms. Pre-print published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McFayden T.C., Breaux R., Bertollo J.R., Cummings K., Ollendick T.H. Covid-19 remote learning experiences of youth with neurodevelopmental disorders in rural Appalachia. J. Rural Ment. Health. 2021;45:72–85. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garthe R.C., Kim S., Welsh M., Wegmann K., Klingenberg J. Cyber-victimization and mental health concerns among middle school students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52:840–851. doi: 10.1007/s10964-023-01737-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lessard L.M., Puhl R.M. Adolescent academic worries amid covid-19 and perspectives on pandemic-related changes in teacher and peer relations. Sch Psychol. 2021;36:285–292. doi: 10.1037/spq0000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellis W.E., Dumas T.M., Forbes L.M. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can J Behav Sci. 2020;52:177–187. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itani M.H., Eltannir E., Tinawi H., Daher D., Eltannir A., Moukarzel A.A. Severe social anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19 lockdown. J. Patient Exp. 2021;8 doi: 10.1177/23743735211038386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James K.M., Silk J.S., Scott L.N., et al. Peer connectedness and social technology use during COVID-19 lockdown. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s10802-023-01040-5. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coyle S., Vagos P., Masia C., et al. A qualitative study of social anxiety and impairment amid the COVID-19 pandemic for adolescents and Young Adults in Portugal and the US. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2022:115–131. doi: 10.32457/ejep.v15i2.1952. Published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wray-Lake L., Wilf S., Kwan J.Y., Oosterhoff B. Adolescence during a pandemic: examining us adolescents' time use and family and peer relationships during COVID-19. Youth. 2022;2:80–97. doi: 10.3390/youth2010007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mlawer F., Moore C.C., Hubbard J.A., Meehan Z.M. Pre-pandemic peer relations predict adolescents' internalizing response to covid-19. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021;50:649–657. doi: 10.1007/s10802-021-00882-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freitas C.M., Silva I.V., Cidade N da. Covid-19 as a global disaster: challenges to risk governance and social vulnerability in Brazil. Ambiente Sociedade. 2020;23 doi: 10.1590/1809-4422asoc20200115vu2020l3id. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gori M., Schiatti L., Amadeo M.B. Masking emotions: face masks impair how we read emotions. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruba A.L., Pollak S.D. Children's emotion inferences from masked faces: implications for social interactions during COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stadheim J., Johns A., Mitchell M., Smith C.J., Braden B.B., Matthews N.L. A qualitative examination of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with autism and their parents. Res Dev Disabil. 2022;125 doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris P.O., Hope E., Foulsham T., Mills J.P. Parent-reported social-communication changes in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Int J Dev Disabil. 2021;69:211–225. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2021.1936870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Giunta L., Lunetti C., Fiasconaro I., et al. Covid-19 impact on parental emotion socialization and youth socioemotional adjustment in Italy. J Res Adolesc. 2021;31:657–677. doi: 10.1111/jora.12669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merkaš M., Perić K., Žulec A. Parent distraction with technology and child social competence during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of parental emotional stability. J Fam Commun. 2021;21:186–204. doi: 10.1080/15267431.2021.1931228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baumeister R.F., Leary M.R. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117:497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reid Chassiakos Y (Linda), Radesky J., Christakis D., et al. Children and adolescents and digital media. Pediatrics. 2016;138 doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorsky M.R., Breaux R., Cusick C.N., et al. Coping with covid-19: longitudinal impact of the pandemic on adjustment and links with coping for adolescents with and without ADHD. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021;50:605–619. doi: 10.1007/s10802-021-00857-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Brien R.P., Parra L.A., Cederbaum J.A. “Trying my best”: sexual minority adolescents' self-care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:1053–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.