Abstract

Objective:

Genetic studies of familial central precocious puberty (CPP) have suggested that makorin ring finger protein 3 (MKRN3) is the primary inhibitor of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Obesity in girls can cause early puberty by affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. This study evaluated serum MKRN3 levels of patients with CPP and its relationship with body mass index (BMI).

Methods:

The study included 92 CPP and 86 prepubertal healthy controls (HC) aged 6-10 years. The CPP and HC groups were divided into obese and non-obese subgroups to evaluate whether BMI affects MKRN3. Patients’ presenting complaints, chronological age, height age, bone age, Tanner stage, standard deviation scores for weight, height, and BMI, levels of follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estradiol, and MKRN3, and pelvic ultrasonography findings were recorded.

Results:

Serum MKRN3 levels were lower in the CPP group and lowest in the CPP-obese subgroup. There were significant differences in MKRN3 levels between the CPP-obese and CPP-normal weight (p=0.02), CPP-obese and HC-obese (p<0.001), and CPP-obese and HC-normal weight (p=0.03) groups. MKRN3 and BMI were negatively correlated in all cases (r=-0.326, p<0.001).

Conclusion:

The negative correlation between BMI and MKRN3, and lower MKRN3 levels in CPP-obese patients, suggests that adipose tissue has a role in the onset of puberty. More comprehensive studies are needed to determine the relationship between MKRN3 and adipose tissue.

Keywords: Makorin ring finger protein 3, central precocious puberty, obesity, children

What is already known on this topic?

Puberty is initiated by the complex interaction of stimulatory and suppressive factors. Obesity in girls can cause early puberty by affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Makorin ring finger protein 3 (MKRN3) is the primary inhibitor of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion.

What this study adds?

Serum MKRN3 levels were found to be negatively correlated with levels of follicle stimulating hormone and estradiol, and also body mass index (BMI), uterine length and ovarian volumes. Serum MKRN3 level was lowest in the central precocious puberty (CPP)-obese group. The negative correlation between BMI and MKRN3, and lower MKRN3 levels in CPP-obese patients, suggest that adipose tissue has a role in the onset of puberty.

Introduction

Puberty is a period of rapid growth, marking the transition from sexual immaturity to sexual maturity. It is characterized by the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics, the achievement of reproductive capacity, and psychological changes. Puberty results from complex, co-ordinated, neuroendocrine mechanisms involving the maturation and activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) (1).

Obesity affects all organ systems, especially the neuroendocrine system. The interaction of numerous genes controlling puberty activates the HPG axis and initiates puberty. The epigenetic effects of adipokines secreted from adipose tissue affect the functions of these genes. The ability of adipose tissue to accumulate sex hormones and inter-convert them enzymatically also affects pubertal development (2,3). The relationship between obesity and pubertal timing is thought to be controlled by adipokines, hyperandrogenism, the aromatase effect of adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia (4).

Makorin ring finger protein 3 (MKRN3) is an intronless gene located on chromosome 15q11.2 in the Prader-Willi syndrome critical region that was first identified by Jong et al. (5) in 1999. A 2013 study of families with central precocious puberty (CPP) by Abreu et al. (6) found that the MKRN3 gene has effects on children entering puberty. MKRN3 is also a major inhibitor of GnRH secretion in childhood (6,7). An indirect way to determine the function of MKRN3 in humans is to investigate serum levels in different conditions. Studies have shown that serum MKRN3 levels decrease before puberty (8,9,10,11) and are negatively correlated with gonadotropin levels (9,12,13). Grandone et al. (13) and Li et al. (14) observed a negative correlation between MKRN3 and body mass index (BMI). The present study examined the relationship between obesity and MKRN3 in CPP by comparing serum MKRN3 levels between obese and normal-weight CPP patients.

Methods

Patients and Controls

The study recruited 92 girls with CPP, and 86 age-matched prepubertal girls as healthy controls (HC), from the Pediatric Endocrinology Department from June 2019 to July 2021. To evaluate whether BMI affects MKRN3, the CPP and HC groups were divided into obese and non-obese subgroups. The presence of breast development before the age of 8 years, menarche before the age of 10 years, advanced bone age [a standard deviation (SD) score (SDS) of +2 relative to the chronological age], basal luteinizing hormone (LH) ≥1 mIU/mL or peak LH ≥5 mIU/mL in the GnRH stimulation test, uterine length ≥35 mm, and ovarian volume ≥2 mL on obstetric ultrasonography were used to diagnose CPP in the girls. Obesity was defined as a BMI above the 95th percentile or +2 SDS (15). In our pediatric endocrinology outpatient clinic, we obtain a history, perform a physical examination, examine routine laboratory tests (fasting blood glucose, insulin, thyroid function tests, triglyceride, cholesterol, and ALT) and perform abdominal ultrasonography to differentiate exogenous and endogenous obesity. All examinations of the patients included in this study were normal. In addition, obesity due to Cushing’s syndrome, chronic drug use (for example, corticosteroids), and monogenic obesity syndromes were excluded. The prepubertal stage was defined clinically as the absence of breast budding and pubic hair (Tanner stage 1). Children with tumors, organic or endocrine disease, premature thelarche, or syndromic disease, and those taking medications, were excluded.

The study protocol was in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine, Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (protocol no: 10, date: 25.06.2019). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study and their parents. This study was supported by the Eskisehir Osmangazi University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (project no. TTU-2021-1630).

Evaluation of Growth and Development

All girls underwent physical examination, including weight and height, BMI, and Tanner breast development stage. BMI was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared. Height, weight, and BMI were expressed as SDS using growth reference percentiles for Turkish children and adolescents (16,17).

The left wrist was X-rayed to determine bone age according to the Greulich-Pyle method (18). Gynecological ultrasound was performed to observe the ovarian volume, uterine length, and fundus/cervix ratio, as well as for secondary follicle determination. Pituitary and cranial magnetic resonance imaging were performed in patients diagnosed with CPP younger than six years of age.

Biochemical Analysis

All blood samples were drawn between 8.00 a.m. and 10.00 a.m. from an antecubital vein, clotted, and centrifuged; serum was stored at -80 °C until hormone analyses were performed. For CPP girls, blood samples were withdrawn before GnRH analog treatment was started. The serum LH, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and estradiol (E2) levels were measured by immunochemiluminometric assays using a COBAS 8000 autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The lowest LH and FSH level determined by this method is 0.1 mIU/mL, and the lowest E2 level is 5 pg/mL. Gonadorelin acetate (Ferring, Germany) was used for the GnRH stimulation test, with an injected dose of 2.5 µg/kg (maximum dose=100 µg). LH and FSH were measured before the injection, and 20, 40, 60, and 90 min thereafter (19,20). The serum MKRN3 levels were measured using human MKRN3 ELISA kits (BT Lab, China), with a 0.019 ng/mL detection limit. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were less than 8% and 10%, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (version 21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and values >0.05 were considered normal. For normally distributed continuous variables, the data are expressed as the mean±SD, and for non-normally distributed variables, they are expressed as the median and interquartile range. Independent samples t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were utilized to compare normally distributed continuous variables. The Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests were used to compare non-normally distributed variables. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables. One-way ANOVA and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to determine whether the study data differed between the normal weight and obese groups. To determine which groups were responsible for differences, the least significant difference post hoc test was used when variance was homogeneous; Tamhane’s T2 test was used when the variance was not homogeneous. The relationships of MKRN3 with other biochemical indicators were evaluated using Spearman’s correlation. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

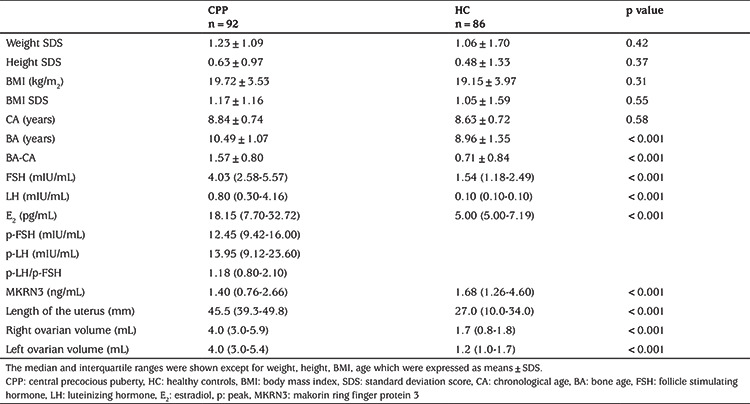

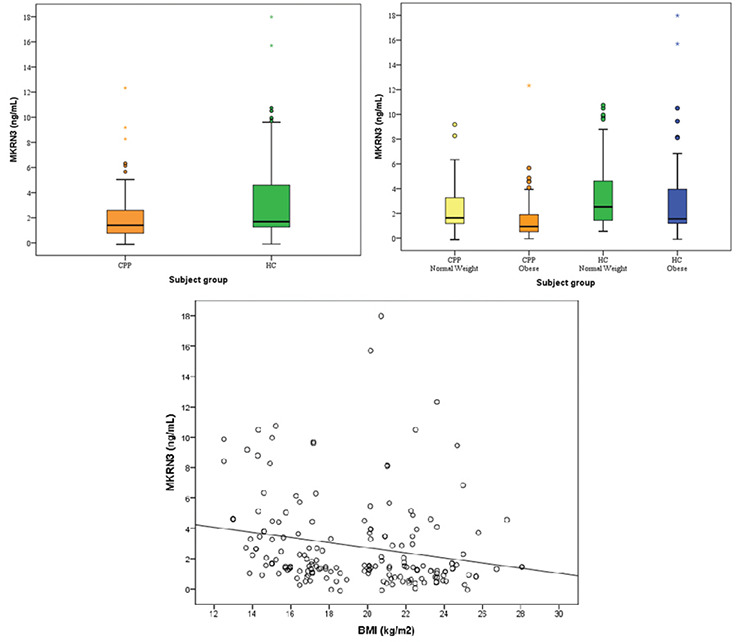

No secondary sex characteristics were detected in the HC girls. All CPP girls had bilateral breast development. Of these girls, 30 (33%), 43 (47%), 18 (29%), and 1 (1%) were Tanner stages II, III, IV and V, respectively. Nineteen CPP patients had progressed to menarche. Table 1 summarizes the girls’ clinical and biochemical characteristics. Bone age was increased in the CPP patients compared with the controls. As expected, CPP girls had higher serum LH, FSH, and E2 levels than the HC group (all p<0.001). The serum MKRN3 levels were lower in the CPP than HC group (p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 1. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of the CPP and HC girls.

Figure 1.

Serum MKRN3 concentrations, and negative correlations between serum MKRN3 levels and BMI in all cases

CPP: central precocious puberty, HC: healthy controls, BMI: body mass index, MKRN3: makorin ring finger protein 3

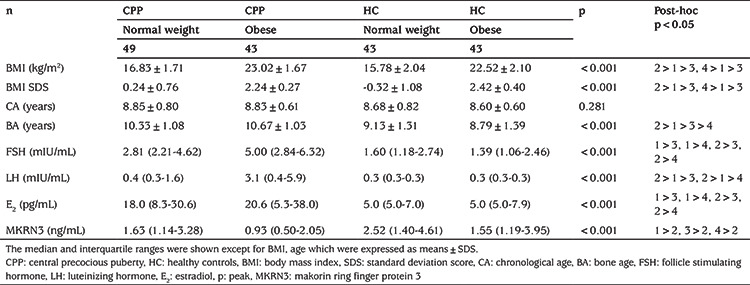

Table 2 shows the clinical and biochemical characteristics of the obese and non-obese subgroups. Although their chronological ages were similar, bone age was increased most in the CPP-obese group. Serum MKRN3 levels were lower in the CPP-obese group compared to the other groups (p<0.001).

Table 2. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of the obese and non-obese groups.

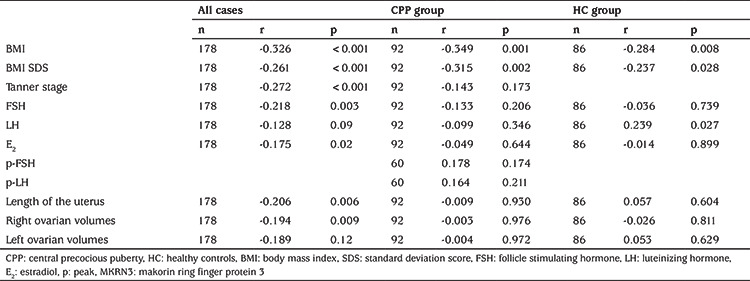

Serum MKRN3 levels were inversely correlated with BMI (Figure 1), Tanner stage, FSH, E2, uterus length, and right and left ovarian volumes, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Correlations between MKRN3 and other biochemical indicators.

Discussion

Puberty is a complex developmental process that leads to sexual maturation and reproductive capacity, resulting in spermatogenesis in boys and ovulation in girls. This arises from a coordinated sequence of events controlled by genetic, neurochemical, metabolic, and environmental factors (21).

In 1970, Frisch and Revelle (22,23) suggested there is a critical body weight controlling pubertal timing and menarche in girls. Many studies have shown that girls with more body fat undergo puberty earlier (4,24,25,26). Several cross-sectional studies have reported significant correlations between obesity and earlier menarche (27,28,29). Wang (30) investigated the relationship between obesity and early sexual development in 1,501 girls and 1,520 boys aged 8-14 years. In girls, they found positive correlations between early sexual development and BMI, obesity, and subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness. The increased risk of early puberty in girls may be related to the recent increase in childhood obesity (31).

The MKRN3 gene, located on chromosome 15 in the Prader-Willi syndrome-associated region (15q11-q13), was found to be mutated in five families with familial precocious puberty (6). These included frameshift, nonsense, and missense mutations (32). MKRN3 is expressed in the hypothalamus and other tissues (33). MKRN3 expression is also high in the hypothalamus of prepubertal mice, rats, and primates; it decreases rapidly before puberty and remains low thereafter (6,34). Thus, MKRN3 is thought to inhibit the pathways leading to the onset of puberty. Abreu et al. (34) reported that MKRN3 is expressed in KISS1 neurons of the mouse hypothalamic arcuate nucleus and that MKRN3 repressed the promoter activity of human KISS1 and TAC3. MKRN3 also has ubiquitinase activity, which is reduced by MKRN3 mutations affecting the RING finger domain; these mutations compromise the ability of MKRN3 to suppress KISS1 and TAC3 promoter activity. Thus, MKRN3 is thought to act at the level of kisspeptin or GnRH neurons.

This study investigated how serum MKRN3 levels change with obesity in girls with CPP. Previous studies revealed that the serum MKRN3 level was significantly lower in girls with CPP than prepubertal girls (11,13,14). We found that median serum MKRN3 levels were 1.40 (0.76-2.66) ng/mL in the CPP group and 1.68 (1.26-4.60) ng/mL in the HC group. The decreased MKRN3 levels in girls with CPP support the association of MKRN3 with the inhibition of GnRH secretion and pubertal initiation, and concur with previous reports of peripubertal changes in serum MKRN3 levels (9,11,12,13,35).

Hagen et al. (9) reported that MKRN3 was negatively correlated with gonadotropin levels in prepubertal girls. Grandone et al. (13) reported that MKRN3 was negatively correlated with gonadotropins and E2 in CPP, normal age prepubertal, and pubertal girls. Ge et al. (12) reported that MKRN3 was negatively correlated with gonadotropin levels in girls with premature thelarche and CPP. The prepubertal decline in MKRN3, and its negative correlation with gonadotropins, support the notion that MKRN3 is a major inhibitor of hypothalamic GnRH secretion during childhood. Inter-individual variation in circulating MKRN3 indicates that there is no standard threshold with respect to when MKRN3 initiates puberty. We found that serum MKRN3 levels were negatively correlated with FSH and E2, and non-significantly correlated with LH. We also found negative correlations between MKRN3 and the uterine length and ovarian volume, also supporting a relationship between MKRN3 decline and the onset of puberty. FSH and LH are hormones produced by the anterior pituitary in response to GnRH from the hypothalamus (36). In men, Leydig cells produce testosterone under the control of LH. However, in women, FSH stimulates granulosa cells in the ovarian follicles to synthesize aromatase, which converts androgens produced by the thecal cells to E2 (37). Our study revealed that, the effect of the peripubertal decline in MKRN3 on FSH is more prominent than its effect on LH.

Grandone et al. (13) and Li et al. (14) found negative correlations between MKRN3 and BMI, while Jeong et al. (11) did not (35). The BMI and BMI SDS of the patient and control groups in these studies were within the normal range. In our study, the MKRN3 level was lowest in the CPP-obese group, and there was a significant difference between the CPP-obese and other subgroups (CPP-normal weight, HC-normal weight, and HC-obese). There was no difference in MKRN3 level among the CPP-normal weight, HC-normal weight, and HC-obese groups. Although the MKRN3 level in the CPP group was lower than in the HC group, the MKRN3 levels of the CPP-normal weight group did not differ from the HC-normal weight and HC-obese groups, which indicates there is a relationship between obesity and MKRN3. In addition, there was no significant difference between the HC-normal weight and HC-obese groups; the median value was higher in the HC-normal weight group. We hypothesize that MKRN3 levels may decrease due to the effects of obesity. Finally, MKRN3 levels do not appear to represent a marker for discriminating precocious puberty between CPP-normal weight and HC-obese groups. This suggests that puberty is not only affected by MKRN3 or obesity and that the mechanisms are complex. There was also a negative correlation between MKRN3 and BMI. The relationship between adiposity and the onset of puberty, as well as between obesity and early menarche, is known (38). The negative correlation with BMI suggests that MKRN3 in girls is modulated by nutritional factors and adipokines, such as leptin.

Leptin is a peptide hormone released from adipose tissue in proportion to its mass. Leptin levels are associated with the energy reserve required for pubertal development, and levels convey this status to the hypothalamus. Leptin acts in the sensitization of hypothalamic GnRH neurons and stimulates GnRH by binding to the leptin receptor and activating kisspeptin (39,40). Leptin permits puberty to progress only if adequate body energy reserves are available (41), although a recent study showed that the peripubertal decrease in MKRN3 expression was independent of the effect of leptin in a leptin-deficient mouse model (42). Therefore, the interactions and relationships between neuroendocrine factors and adipokines at the onset of puberty have not yet been fully elucidated. The negative correlation between BMI and MKRN3, and lower MKRN3 levels in obese patients in early puberty, suggests that another factor modulates the effect of adipose tissue on the onset of puberty. Unfortunately, leptin was not measured in our patients.

Study Limitations

MKRN3 gene analysis was not performed in our study but selective genetic testing should be performed in patients with very low or very high MKRN3 values. Since our study group was divided into obese and non-obese cases, overweight cases were not evaluated separately. Finally, the relationship between leptin and MKRN3 has not been evaluated. In future studies, the limitations of our study can be eliminated by evaluating a larger sample group and investigating MKRN3 levels in patients with overweight and/or morbid obesity. Furthermore, this design would enable the relationship between leptin and MKRN3 to be evaluated.

Conclusion

In conclusion, serum MKRN3 levels were lower in girls with CPP than controls, supporting the finding that MKRN3 levels decrease at the onset of puberty and have a role therein. The negative correlation between BMI and MKRN3, and the lower MKRN3 levels in CPP-obese cases, suggest that another factor modulates the effect of adipose tissue on the onset of puberty. More comprehensive studies are needed to determine the relationship between MKRN3 and adipose tissue.

Footnotes

Ethics

Ethics Committee Approval: The study protocol was in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine, Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (protocol no: 10, date: 25.06.2019).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study and their parents.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship Contributions

Surgical and Medical Practices - Concept - Design - Data Collection or Processing - Analysis or Interpretation - Literature Search - Writing: Sümeyye Emel Eren, Enver Şimşek.

Financial Disclosure: This study was supported by the Eskişehir Osmangazi University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (project no: TTU-2021-1630).

References

- 1.Choi JH, Yoo HW. Control of puberty: genetics, endocrinology, and environment. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:62–68. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32835b7ec7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soliman AT, Yasin M, Kassem A. Leptin in pediatrics: a hormone from adipocyte that wheels several functions in children. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 3):577–587. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.105575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shalitin S, Gat-Yablonski G. Associations of obesity with linear growth and puberty. Horm Res Paediatr. 2022;95:120–136. doi: 10.1159/000516171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W, Liu Q, Deng X, Chen Y, Liu S, Story M. Association between Obesity and Puberty Timing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1266. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jong MT, Gray TA, Ji Y, Glenn CC, Saitoh S, Driscoll DJ, Nicholls RD. A novel imprinted gene, encoding a ring zinc-finger protein, and overlapping antisense transcript in the Prader-Willi syndrome critical region. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:783–793. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abreu AP, Dauber A, Macedo DB, Noel SD, Brito VN, Gill JC, Cukier P, Thompson IR, Navarro VM, Gagliardi PC, Rodrigues T, Kochi C, Longui CA, Beckers D, de Zegher F, Montenegro LR, Mendonca BB, Carroll RS, Hirschhorn JN, Latronico AC, Kaiser UB. Central precocious puberty caused by mutations in the imprinted gene MKRN3. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2467–2475. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macedo DB, Abreu AP, Reis AC, Montenegro LR, Dauber A, Beneduzzi D, Cukier P, Silveira LF, Teles MG, Carroll RS, Junior GG, Filho GG, Gucev Z, Arnhold IJ, de Castro M, Moreira AC, Martinelli CE Jr, Hirschhorn JN, Mendonca BB, Brito VN, Antonini SR, Kaiser UB, Latronico AC. Central precocious puberty that appears to be sporadic caused by paternally inherited mutations in the imprinted gene makorin ring finger 3. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1097–1103. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busch AS, Hagen CP, Almstrup K, Juul A. Circulating MKRN3 levels decline during puberty in healthy boys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:2588–2593. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagen CP, Sørensen K, Mieritz MG, Johannsen TH, Almstrup K, Juul A. Circulating MKRN3 levels decline prior to pubertal onset and through puberty: a longitudinal study of healthy girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1920–1926. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varimo T, Dunkel L, Vaaralahti K, Miettinen PJ, Hero M, Raivio T. Circulating makorin ring finger protein 3 levels decline in boys before the clinical onset of puberty. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174:785–790. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong HR, Lee HJ, Shim YS, Kang MJ, Yang S, Hwang IT. Serum Makorin ring finger protein 3 values for predicting Central precocious puberty in girls. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35:732–736. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2019.1576615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge W, Wang HL, Shao HJ, Liu HW, Xu RY. Evaluation of serum makorin ring finger protein 3 (MKRN3) levels in girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty and premature thelarche. Physiol Res. 2020;69:127–133. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.934222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandone A, Cirillo G, Sasso M, Capristo C, Tornese G, Marzuillo P, Luongo C, Rosaria Umano G, Festa A, Coppola R, Miraglia Del Giudice E, Perrone L. MKRN3 levels in girls with central precocious puberty and correlation with sexual hormone levels: a pilot study. Endocrine. 2018;59:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Chen Y, Liao B, Tang J, Zhong J, Lan D. The role of kisspeptin and MKRN3 in the diagnosis of central precocious puberty in girls. Endocr Connect. 2021;10:1147–1154. doi: 10.1530/EC-21-0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakshman R, Elks CE, Ong KK. Childhood obesity. Circulation. 2012;126:1770–1779. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neyzi O, Furman A, Bundak R, Gunoz H, Darendeliler F, Bas F. Growth references for Turkish children aged 6 to 18 years. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:1635–1641. doi: 10.1080/08035250600652013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bundak R, Furman A, Gunoz H, Darendeliler F, Bas F, Neyzi O. Body mass index references for Turkish children. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:194–198. doi: 10.1080/08035250500334738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist. 2nd ed ed. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press. 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ab Rahim SN, Omar J, Tuan Ismail TS. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test and diagnostic cutoff in precocious puberty: a mini review. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;25:152–155. doi: 10.6065/apem.2040004.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandemir N, Demirbilek H, Özön ZA, Gönç N, Alikaşifoğlu A. GnRH stimulation test in precocious puberty: single sample is adequate for diagnosis and dose adjustment. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;3:12–17. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.v3i1.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maione L, Naulé L, Kaiser UB. Makorin ring finger protein 3 and central precocious puberty. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2020;14:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.coemr.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frisch RE, Revelle R. Height and weight at menarche and a hypothesis of critical body weights and adolescent events. Science. 1970;169:397–399. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3943.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frisch RE, Revelle R. The height and weight of girls and boys at the time of initiation of the adolescent growth spurt in height and weight and the relationship to menarche. Hum Biol. 1971;43:140–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner IV, Sabin MA, Pfäffle RW, Hiemisch A, Sergeyev E, Körner A, Kiess W. Effects of obesity on human sexual development. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:246–254. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenfield RL, Lipton RB, Drum ML. Thelarche, pubarche, and menarche attainment in children with normal and elevated body mass index. Pediatrics. 2009;123:84–88. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biro FM, Kiess W. Contemporary trends in onset and completion of puberty, gain in height and adiposity. Endocr Dev. 2016;29:122–133. doi: 10.1159/000438881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barcellos Gemelli IF, Farias EDS, Souza OF. Age at Menarche and Its Association with Excess Weight and Body Fat Percentage in Girls in the Southwestern Region of the Brazilian Amazon. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bau AM, Ernert A, Schenk L, Wiegand S, Martus P, Grüters A, Krude H. Is there a further acceleration in the age at onset of menarche? A cross-sectional study in 1840 school children focusing on age and bodyweight at the onset of menarche. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:107–113. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wronka I. Association between BMI and age at menarche in girls from different socio-economic groups. Anthropol Anz. 2010;68:43–52. doi: 10.1127/0003-5548/2010/0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y. Is obesity associated with early sexual maturation? A comparison of the association in American boys versus girls. Pediatrics. 2002;110:903–910. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization; 2021. Accessed December 26, 2021. [Internet] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- 32.Valadares LP, Meireles CG, De Toledo IP, Santarem de Oliveira R, Gonçalves de Castro LC, Abreu AP, Carroll RS, Latronico AC, Kaiser UB, Guerra ENS, Lofrano-Porto A. MKRN3 Mutations in Central Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Endocr So. 2019;3:979–995. doi: 10.1210/js.2019-00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Känsäkoski J, Raivio T, Juul A, Tommiska J. A missense mutation in MKRN3 in a Danish girl with central precocious puberty and her brother with early puberty. Pediatr Res. 2015;78:709–711. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abreu AP, Toro CA, Song YB, Navarro VM, Bosch MA, Eren A, Liang JN, Carroll RS, Latronico AC, Rønnekleiv OK, Aylwin CF, Lomniczi A, Ojeda S, Kaiser UB. MKRN3 inhibits the reproductive axis through actions in kisspeptin-expressing neurons. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:4486–4500. doi: 10.1172/JCI136564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeong HR, Yoon JS, Lee HJ, Shim YS, Kang MJ, Hwang IT. Serum level of NPTX1 is independent of serum MKRN3 in central precocious puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2021;34:59–63. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2020-0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamatiades GA, Kaiser UB. Gonadotropin regulation by pulsatile GnRH: Signaling and gene expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;463:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biro FM, Pinney SM, Huang B, Baker ER, Walt Chandler D, Dorn LD. Hormone changes in peripubertal girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3829–3835. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.German A, Shmoish M, Hochberg ZE. Predicting pubertal development by infantile and childhood height, BMI, and adiposity rebound. Pediatr Res. 2015;78:445–450. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu WH, Kimura M, Walczewska A, Karanth S, McCann SM. Role of leptin in hypothalamic-pituitary function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1023–1028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinehr T, Roth CL. Is there a causal relationship between obesity and puberty? Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3:44–54. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tena-Sempere M. Keeping puberty on time: novel signals and mechanisms involved. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2013;105:299–329. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396968-2.00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts SA, Abreu AP, Navarro VM, Liang JN, Maguire CA, Kim HK, Carroll RS, Kaiser UB. The Peripubertal Decline in Makorin Ring Finger Protein 3 Expression is Independent of Leptin Action. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4:bvaa059. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]