Abstract

Introduction

Healthcare environments consist of a variety of different fomites containing infectious agents. From the 2003 outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome to the recent concerns about the Ebola and Zika viruses, interest in the role of healthcare environment fomites in spreading infectious diseases has increased. Because of a high risk of being exposed to infections, the goal of this study was to learn how hospital interior environments impact nurses' perceptions of safety about infectious diseases.

Methods

Semistructured, in-depth interviews were conducted with six nurses at a public hospital.

Results

The following three themes were identified: (1) perceptions of safety from infectious diseases were diverse among the participants; (2) various interior environments in hospital settings can prevent as well as promote the spreading of infectious diseases; and (3) the different perceptions influenced the ways participants developed their contrasting behaviors of treating interior environments to cope with their fears (e.g., how they open doors).

Conclusion

The findings from this study contribute to the existing body of knowledge on designing hospital interior environments to better understand nurses' perception of infectious diseases.

Keywords: hospital, infectious diseases, nurses, perception, safety

BACKGROUND

Even though hospitals are places for healing, they are also places that can spread infections or diseases. According to the Institute of Medicine, healthcare-associated infections (HAI) and medical errors cause more death in the United States than AIDS, breast cancer, or automobile accidents.[1] In 2015, more than one million HAIs were reported in US healthcare facilities, which led to approximately 75,000 patient deaths and billions of dollars in healthcare costs.[2] More specifically, from the late 1990s until recently, a significant decrease in HAI rates was found after implementing different layouts in intensive care units (ICUs).[3–5] Other literature investigated how HAI rates were associated with different room types (i.e., single and multiple bedrooms).[6,7] Additionally, there is growing evidence that contaminated surfaces play a key role in the spread of viral infections.[8–10] These infections can be fatal, and the transmission of infection generally happens through two routes, airborne and direct and/or indirect contact.[8]

This study sought to investigate how, specifically, hospital interior environments (e.g., the different types/designs of door handles, the door operating system, and locations of hand sanitizer) can influence the perception of safety from infectious diseases among nurses. Hospital environments are extremely vulnerable to infectious diseases, particularly ICUs and places with a high volume of people. Most of the research previously published has been conducted by authors in public health or medical fields; there are limited studies from the design field. By adding a design perspective, this study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on healthcare interior environments regarding the spread of infectious diseases.

Some interior environment components, such as doorknobs, elevator buttons, and shared medical equipment, can prevent or promote the spread of infectious diseases. For example, people might feel safer and more secure from the possibility of getting infectious diseases if spaces are divided with doors. However, in order to move from one place to another, people need to open doors. The act of touching doors and holding handles might also affect people's perceptions of cleanliness and infection. People might perceive that the type and design of doors can help spread infections among people.

Contact with soiled, infectious, and harmful substances can increase people's fear of contamination. In order to prevent the spread of contamination, people usually attempt to isolate their hands, for example, by using their feet, elbows, or the back of their body to open doors.[11] However, there is no specific literature about the perceptions of specific interior environments that might relate to feelings of security and safety from infections.

The goal of this study was to learn how hospital interior environments impact nurses' perception of safety and infectious diseases, and specifically how nurses perceive the relationship between interior environments and infectious diseases. The target population for this study was nurses because they spend a significant amount of time in hospital spaces. They are at a high risk of exposure to infections through direct contact with infected patients and perceive the seriousness of infections.

Hospital workers, including nurses, who are concerned about personal safety and/or the safety of their family from getting infectious diseases, have also been continuously studied.[12,13] This study investigates how hospital interior environments impact nurses' perception of safety from infectious diseases. Therefore, the study fills the gap in the body of knowledge in hospital environments from a design and psychology perspective.

The research questions that guided this study were as follows: (1) How do nurses perceive the impact of hospital interior environments on infectious diseases? (2) How do nurses perceive the interior environment components which affect the spread of infectious diseases? (3) How does nurses' behavior reflect their perception of relationships between hospital interior environments and infectious diseases?

To answer the research questions, a phenomenological approach was selected; there are several rationales behind this selection. Phenomenology is one of five different traditions in qualitative research, as well as biography, grounded theory, ethnography, and case study. In phenomenology, answers to research questions are expected to provide a general knowledge of the essence of experiences about a phenomenon.[14] In addition, phenomenology is suitable for this study because participants' experiences regarding medical procedures or infectious diseases can be studied through the ways participants perceive safety in their daily work environment.[15] In terms of a research methodology, phenomenology does not try to develop a theory to explain the world; rather it focuses on finding the common thoughts among respondents to describe the universal essence.[16] Phenomenology is helpful as it allows a rigorous exploration of the lived experience or of a phenomenon.[17] For this study, particularly, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis was applied because it emphasizes meanings formed through people's experiences while they interact with the environment.[17]

Literature Review

Infectious diseases and physical environments

Researchers have studied the physical environments of healthcare facilities extensively for many years.[9,18–20] However, the correlation between physical environment settings in healthcare facilities and the actual rates of infectious diseases has been investigated by only a few studies.[21–23]

According to Ulrich et al.,[9] one of two general routes for transmitting infections to people is airborne. In other words, having good air quality and patients in single- rather than multi-person bedrooms can lower infection rates. The other general route for transmitting infection is direct/indirect contact. As a key interior environment component, one good example of indirect contact is doors. An observational study was conducted to evaluate the association of airflow and door openings with operating room contamination.[22] Two sterile basins were placed inside and outside the laminar airflow during orthopedic surgery and compared for contamination levels. The study found the number of contaminated basin plates was increased by any door opening by almost 70%.[22] Another research project also investigated door opening activities in operating rooms through an observational study.[21] The researchers focused on diverse variables, such as surgery case, time, reason, and the people who affected the number of door openings during operations. However, the study did not further examine how infection rates were affected by opening doors during surgery. In addition to doors, other interior environment components of healthcare settings, such as layout, materials, equipment, and furnishings have been investigated for their associations with the spread of infectious diseases.[24]

There are a variety of different fomites containing infectious agents (i.e., virus, fungi, and bacteria) in healthcare environments.[25] Fomites can be defined as inanimate objects that can carry infectious diseases, such as sharing equipment promoting the spread of architectural fomites.[26] For example, in healthcare environments, viruses have been detected surviving on countertops, cloth gowns.[27] doorknobs, faucets,[28] carpet, curtains, and bed rails.[29]

Even though healthcare workers and patients share the same environment, because the two groups use different components of the environment (e.g., medical equipment, computer keyboards and mice, doorknobs, and individual beds), they might have different perceptions of the environment's influence on the spread of infectious diseases. For example, in terms of environmental components, healthcare workers may mainly use and touch medical equipment and computer keyboard(s) while working, whereas patients may primarily touch and use their personal belongings, furniture in reception areas, and their bed in treatment areas. Therefore, knowing occupants' perception of the environmental components regarding the spread of infectious diseases is critical, because infectious pathogens can survive on those environmental components. In addition, in order to introduce behavioral interventions to prevent the spread of infectious diseases through environmental components, understanding the occupants' perception is informative.

Infectious diseases from psychological perspectives

In terms of psychological perspectives, Vogler and Jorgensen[30] describe space with the following four categories: (1) physiological space, (2) perceptible space, (3) psychological space, and (4) sociological space. That paper emphasizes the reason space has more than one category is that the elements composing space, such as doors and thresholds, do not have a simple role. Doors are one of the key elements in defining space (e.g., private space and public space) and, at the same time, they can give people feelings of security and safety by separating one space from other spaces. Because there is no literature about the relationship between physical environments and perceptions of secure feelings, this study attempts to fill to the gap in previous literature and provide a new perspective.

From the cognitive psychological perspective, fear-acquisition theory explains the three pathways a fear of contamination can generate, including (1) transmission of threatening information, (2) observing frightened reactions in other people, and (3) conditioning processes establishing disgust reactions.[11] People, therefore, develop behaviors to cope with their fear. For example, people who suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) usually establish compulsive cleaning habits, and much clinical literature has focused on those safety behaviors among people with OCD.[31–33] According to fear-acquisition theory, the behaviors to cope with a fear and the degree of the feeling of contamination can differ based on individual differences.

However, after the advent of the theory in 1977, it has not been explored to show the relationship between spatial layout and fear of contamination, whereas it has been applied to studies about relationships between fear of contamination and other influential factors, such as age[34] and neuroscience mechanism.[35] Moreover, the relationship between enclosed space and fear, which refers to claustrophobia, and open space and fear, which refers to agoraphobia, have been investigated.[36] Therefore, as a pioneer study in the application of fear-acquisition theory, this study was designed to investigate potential relationships showing nurses' perception of fear regarding contamination and the ways they cope with that fear in the environment. Nurses are easily exposed to environments containing infectious agents, and they may experience fear of contamination at healthcare facilities while working. In this study, nurses' perception of safety about infectious diseases is investigated. This study further analyzes the ways they cope with the fear of infectious diseases.

METHODS

Sampling

For this study, semistructured, in-depth interviews were conducted with six nurses. The participants were recruited by using a convenience sampling method (Table 1). One hospital staff member, a registered nurse (NS), reached out to eight colleagues verbally to participate; only six nurses volunteered themselves to be part of the study. The only inclusion criterion was that the person was a nurse at the same hospital; there are no other exclusion criteria. All six participants have worked as a nurse for over 15 years in healthcare environments and they currently work at the same hospital, though in different departments. Two nurses work at an outpatient clinic, and four nurses work in an ICU. Having additional professional groups, such as doctors, may provide further opinions on the same topic. However, as an exploratory study, focusing on one profession may be appropriate to gain a better understanding of the topic within the population, considering the small number of participants. In addition, as the six participants were recruited from two different departments, they provide a more diverse view than if all participants were from one department. In phenomenology, Morse[37] suggested at least six participants should be required to take part in a long interview protocol. For this reason, the data from six participants were analyzed for this exploratory study.

Table 1.

Information about interview participants

|

|

Sex |

Profession |

Professional experience |

Department |

| Participant #1 | Female | Nurse | +15 years | Outpatient clinic |

| Participant #2 | Female | Nurse | +15 years | Outpatient clinic |

| Participant #3 | Female | Nurse | +15 years | Intensive care unit |

| Participant #4 | Female | Nurse | +15 years | Intensive care unit |

| Participant #5 | Female | Nurse | +15 years | Intensive care unit |

| Participant #6 | Female | Nurse | +15 years | Intensive care unit |

Setting

The hospital is located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States and is a public county hospital. It consists of five different buildings and all the buildings are connected through tunnels or overhead enclosed footbridges.

Data Collection

The interview started with an introductory question asking demographic information about how long the participant has worked in the healthcare facility. Next, the participants were asked questions about their feelings regarding security and safety from infectious diseases at work, and their thoughts on the infectious diseases at their workplace. Finally, they were asked questions about their thoughts on the impact of hospital interior environments on infectious diseases. They were also asked their opinions about the relationship between fundamental interior environment components, such as doors and infectious diseases, as doors are key components and everyday items in the environment. The interview questions (Table 2) were developed to explore the lived experiences of the participants based on the phenomenology approach. The questions were asked to examine how the participants think about their working environments and infectious diseases and how their experiences are affected by their thoughts. During the interview, no specific probes or prompts were used. However, when answers were unclear or too ambiguous, the interviewer asked them to explain with details (e.g., “Can you explain a little bit more?”). The interviews were audio-recorded and conducted individually in a private space at the hospital. Each interview was approximately 25 minutes long and the entire data collection period was 1 week.

Table 2.

Interview questions

| Number |

Questions |

| Q1 | How long you have worked in this healthcare facility? |

| Q2 | How often do you think about “infectious diseases” while working? |

| Q3.1 | Do you personally feel security and safety from infectious diseases while working? |

| Q3.2 | How do you think that patients feel security and safety from infectious diseases while being taken care of? |

| Q4 | What do you think is the most prevalent or related reasons for transferring infectious diseases in healthcare environment? |

| Q5 | How do you think interior environments at healthcare facilities can promote or prevent infectious diseases? Please tell me your thoughts with examples. |

| Q6 | How do you think about the relationship between fundamental interior environment components, which you can see everywhere here, such as doors, and infectious diseases? |

Data Analysis

The interviews were recorded and transcribed. One of the authors coded the transcribed interviews for the primary and secondary themes in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). To be specific, primary themes were the broader topics (e.g., perception of safety and interior environments), while secondary themes were narrower concepts (e.g., coping behaviors and specific interior elements). If an answer could be categorized into more than one theme, it was coded into each different theme.

Ethics

Data were collected after obtaining institutional review board approval. Before conducting the interviews, the participants were required to sign consent forms to be audio recorded. The participants were informed that no personal information identifying participants would be collected, except for sex, department, and tenure, because the participants' confidentiality was important to allow them to express their thoughts related to the ethical questions (e.g., professional behavior and hand hygiene).

RESULTS

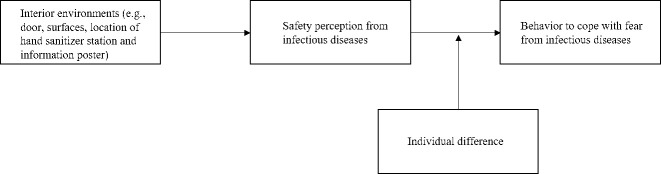

Based on the coded themes, the following three themes (Fig. 1) emerged from the data: (1) perception of safety from infectious diseases was diverse among the participants; (2) various interior environments in hospital settings can prevent, as well as promote the spread of infectious diseases; and (3) the different perceptions influenced the ways participants developed their contrasting behaviors of treating interior environments to cope with their fears, such as how they open doors. Table 3 describes how each participant expressed their thoughts during their interview.

Figure 1.

Three themes from interview with six nurses.

Table 3.

Interview notes per participant

| Interview notes |

Participants |

|||||

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

| Theme I | ||||||

| Familiarity with infectious diseases | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Worry about how infectious diseases can infect the participants | X | X | X | X | ||

| Boldness/part of the practice | X | X | ||||

| Theme II | ||||||

| Location of hand sanitizer stations | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Location of information posters | X | X | ||||

| Implemented interior environmental solution (e.g., negative pressure room and antibacterial surfaces) | X | X | X | |||

| Theme III | ||||||

| Relationship between design and operating systems of doors and infectious diseases | X | X | X | |||

| Never touch the bathroom doors with their bare hands | X | X | X | |||

| Preference for automatic door systems and pushing styles doors | X | X | X | |||

Theme I: Perception of Safety From Infectious Diseases was Diverse Among the Participants

All the participants were very familiar with infectious diseases, and their responses indicated they frequently were concerned about infectious diseases at work. However, the degree of perception of safety varied among the participants. Four of them answered they worry about how infectious diseases can infect themselves. However, Participant One especially showed a bold attitude toward getting infectious diseases in hospital settings even though she reported thinking about infectious diseases frequently. For example, the participant noted, “I guess because I have been doing this for a long time; I just figure that it's going to happen because it's going to happen.”

Participant Two expressed personal worries about contracting infectious diseases because she was not sure about a patient's history, such as whether a patient has tuberculosis. The participant also mentioned that the staff not using gloves or not washing their hands and then using the same equipment, such as computers, can lead to the spread of infectious diseases among people. Participant Two noted, “Not using gloves for certain things and they are using the same computers in the room that you are and using the computers, which are on the desks, so… equipment that has been in the rooms is basically really dirty and I think they are like the biggest bacteria transmitter.”

Participant Three, who showed their anxiety about getting infectious diseases at work, expressed worries about getting sick from co-workers when they come in sick, even though the participant usually feels safe from infectious diseases at work. However, two participants had a different attitude toward infectious diseases compared with the other four participants. For example, Participant Four, one of two participants that expressed little concern about infectious diseases, noted worrying subconsciously about infectious diseases, but she did not believe that she would contract one:

I think infectious diseases are always in the back of my mind. As you know, we always worry about it, so it is pretty much always in the back of our minds. But, it becomes a part of practices you have to do it for years … I just figure that it (getting infectious diseases) is going to happen because it's going to happen. I do not believe that in my life that happens.

Theme II: Various Interior Environments in Hospital Settings Can Prevent, as Well as Promote, the Spreading of Infectious Diseases

All six participants reported that interior environments at hospital facilities can prevent, as well as promote, the spreading of infectious diseases among people. When they were specifically asked what can be done in interior environments at hospital facilities to prevent infectious diseases, the most frequent answers were the location of hand sanitizer stations and posters to encourage people to use the right equipment, such as masks and medical clothes. The participants also commented that the equipment, such as computers and keyboards, were dirty because everyone shared the same equipment.

The participants stated the location of hand sanitizer is critical to encourage people to use them for hand hygiene. This notion of hand sanitizer location promoting good hand hygiene is supported by previous literature.[38] Keeping hand hygiene levels high is one of the top priorities in hospital environments and has numerous benefits (e.g., lower infectious disease rate).[38] Participant Three said the hand sanitizer canisters should be located in the right place so that people are able to reach them easily and easier access to hand sanitizers in and out before going into difference spaces. According to the participants, the guidelines at the hospital require the workers to sanitize their hands both before entering and leaving a new location. Therefore, all participants reported that putting hand sanitizer canisters in the right places for easier access and higher visibility can prevent the spread of infectious diseases from an interior design perspective.

The participants also reported that posters are helpful to provide people with the required and/or encouraged guidelines. They noted appropriate posters could prevent infectious diseases by reminding people of some important information, such as covering their coughs, putting on masks, using hand sanitizer frequently, and wearing the right equipment and clothing.

The participants further mentioned the interior environmental solutions the hospital has already implemented, including the negative pressure room and the antibacterial surface of doors. According to two participants, in the negative pressure room (air exchange room), when the doors open, air is sucked into the hallway and then the air will be changed. When the doors shut, a little component at the top makes the pressure start again by sucking air. Participant Five brought up the doors' antibacterial surface and recollected that the hospital once had the antibacterial surface doors. The participant tried to show examples but discovered all the doors with antibacterial surfaces were gone. Participant Two also mentioned that surfaces, such as furniture, should be easily wiped off to prevent the spread of infectious diseases.

Theme III: Different Perceptions Influenced the Ways and Behaviors of Treating Interior Environments to Cope With Fears

Three participants responded the design and operating systems of doors can greatly affect infectious diseases. Participant Three mentioned the relationship between doors and infectious diseases: “I think that's the place I would not want to see what is actually growing on some of the doors handles. It has probably a high likelihood of the spread!” Two other participants (Participants Two and Six) also mentioned this is why people need to sanitize their hands before and after opening the doors even though people wash their hands when they leave the bathroom. They also mentioned handles are dirty everywhere and people use their hands to open the doors by touching the handles.

Three participants (Participants Two, Three, and Six) said they never touch the bathroom doors with their bare hands. Instead, they use a paper towel to grab the doorknob to open the doors. Participant Two mentioned hitting the elevator button with her neck chain badge holder and not with her finger. The participant has also seen some places where there are tissues and a garbage can so that people use tissues to open the doors and immediately throw them away in the garbage can.

Three participants who never touch door handles indicated their preference for the automatic systems and pushing styles because they do not have to touch the doors with their hands for those types of systems. They do not need to actually turn the latch with their hands, but they can use their body to push and open the door. Participant Six explained they prefer an automatic or pushing system over actually grabbing and turning the knob:

I think everything will have to be hands-free, like you know how to flush, or wash the hands (turning on and off hot and cold water), they have to be automatic, so you don't have to touch them … I like a pushing system because I do that a lot! Not grabbing and turning. I push the doors with my body!

DISCUSSION

Based on the findings from the data analysis, some implications can be drawn from this study. Figure 2 shows how the three themes, which were found based on the interviews from six nurses, are associated with each other.

Figure 2.

Findings from interview with six nurses.

First, the perception of safety from infectious diseases among the six nurses varies from person to person, but they all care about infectious diseases at hospital facilities while they are working. These individual differences were associated with how the participants developed their behaviors and communicated their thoughts about their environment. As a pilot study that applied the fear-acquisition theory, the finding supports the theory that the individual differences affect behaviors to cope with the fear and the degree of the feeling of contamination. Four participants who discussed their anxiety about infectious diseases have habits of not touching the bathroom door but grabbing and opening doors with a paper towel. Three participants preferred to have the automatic and pushing door systems because they do not have to touch those doors with their hands. On the other hand, the participant who believes that infectious diseases will never happen in her life did not mention any preference for door opening systems or design or any special actions she takes in regard to the doors.

The second implication is that participants primarily associated interior environments at hospital facilities with hand sanitizing, easily wiped off surfaces, and posters. The participants reported that appropriate behaviors (e.g., frequent handwashing) can directly decrease the rate of the spread of infectious diseases. Yet, they could not describe how interior environments can directly and/or indirectly influence the spread of infectious diseases or their behaviors until they were asked, even though they fully acknowledged the potential impacts.

When they were asked about interior environments most related to infectious diseases, they came up with the location of hand sanitizers primarily because hand hygiene is undeniably critical. The importance of hand sanitizer locations for hand hygiene is well known in previous literature.[24] As a part of architectural environments, spatial layouts, materials, furnishings, room type and size, and hand hygiene locations have been mainly investigated for their impact on infectious disease rates.[24,39] However, none of the participants indicated that a door handle specifically may have a relationship to infectious diseases unless they were asked about the relationship. In other words, before they were asked about the relationship between doors and infectious diseases, none of them mentioned the relationship. However, after they were asked about the relationship, all of them acknowledge the relationship. Even though all six participants commented on the importance of hand hygiene because workers are required to sanitize their hands before and after entering a new space, only one of them mentioned the surface of doors as antibacterial.

In addition, participants did not come up with the door operating systems until they were asked. However, when they were specifically asked about the relationship between door design or operating systems and infectious diseases, their reactions were “aha” moments, even among three participants who have a habit of opening bathroom doors using a paper towel. Their responses and reactions to the question suggested that they take for granted opening doors, operate doors habitually and naturally, and have never strongly considered doors as a major source of the spread of infectious diseases. Although they were aware of a high potential for the spread of infections, they had not considered this to be a great source of infections until prompted. After participants were asked the specific question about doors and infectious diseases, they expressed their concerns about the different designs of door handles containing lots of infectious disease bacteria and how that bacteria can be spread through touching and/or holding the handles. In addition, the participants shared their personal habits and preferences regarding doors enthusiastically.

Despite some implications from this study, there are several limitations. First, the total number of participants was too small to generalize the findings. Because all participants were recruited by convenience sampling, not by randomization, there were not enough participants to represent the general characteristics of the population for this study. Furthermore, the findings from this study may not be necessarily generalized to other healthcare environments. This is mainly because this study only includes a hospital setting, and each healthcare environment has its own unique culture and characteristics. However, as Morse[37] and Crewell[33] suggested, having at least six participants can be acceptable for conducting an exploratory and a phenomenological study. Future studies can recruit more participants to understand more diverse opinions.

Second, the limited population group, which only consisted of nursing professionals, is not enough to have a holistic understanding of interior environments and infectious diseases. Additional professionals within the facility, such as doctors, and other population groups, such as patients and visitors, may provide a different view as they share the same environment with the recruited population group. Future studies should explore the same topic with different healthcare professionals to understand whether different professionals may have different perceptions.

Third, because the interviews were transcribed, coded, and then analyzed by a single person, there are some limitations. Because the person who coded and analyzed the data is the person who developed the initial conceptual model for this study, the findings might be affected by the assumptions declared at the beginning of this study. The assumptions might have led to the findings, and the validity of the coding and the categories were not able to be tested. If at least one additional reviewer coded the interviews and compared the coded themes to the initial coded themes, validity could be improved.

The last limitation is that participants worked in different departments (i.e., outpatient clinics and intensive care units). This might have affected the different perception of infectious diseases because the participants are exposed to different settings and interior environments. Therefore, the different perceptions of infectious diseases could be developed solely because of their individual difference. However, because the number of recruited participants is low, a comparison between the different settings is not possible. Therefore, future studies can focus on recruiting healthcare professionals in a single department to delve into the participants' perception of a specific environment.

Increasing the number of participants can provide researchers with much broader views about the spectrum of the participants. Recruiting enough participants from different departments can help researchers explore the different perceptions of infectious diseases. Furthermore, having multiple researchers code, analyze, and compare data could improve the validity of the findings.

Conclusions

Although hospitals are places for healing, they sometimes make people sick instead as some people are vulnerable to infectious diseases. Because nurses are a group of people who are often exposed to infectious agents, this study was developed to explore the nurses' perception of safety from infectious diseases in hospital facilities from an interior design perspective. Six participants were recruited for interviews about infectious diseases and their relationship with interior environments, particularly with door handles and door operating systems.

The findings indicated that each individual's perception of infectious diseases can affect their behaviors, such as grabbing bathroom doors with a paper towel, and their thoughts about contracting infectious diseases at work. These behaviors, in fact, reflect the individual differences in the perception of infectious diseases in their workplace. Moreover, their behaviors demonstrate the participants understood that infection can be passed through physical objects in the environment. However, even though they thought the design of door handles and door operating systems (e.g., automatic doors) could significantly impact the rate of the spread of infectious diseases, they did not consider doors as a major source of the spread of infectious diseases. Instead, the participants primarily considered the appropriate locations for hand sanitizers and informational posters about proper clothing and equipment as the interior environmental components, which could prevent the spread of infectious diseases. For future research, increasing the number of participants, additional populations, and having a third viewpoint for coding and analyzing data can minimize the limitations of this research.

Funding Statement

Source of Support: None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Baker A. Crossing the Quality Chasm A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Control CfD, Prevention. HAI data and statistics. Published 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/archive/2015-HAI-data-report.html. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- 3.Goldmann DA, Durbin WA, Freeman J. Nosocomial infections in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Infect Dis . 1981;144:449–459. doi: 10.1093/infdis/144.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulin B, Rouget C, Clément C, et al. Association of private isolation rooms with ventilator-associated Acinetobacter baumanii pneumonia in a surgical intensive-care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 1997;18:499–503. doi: 10.1086/647655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stiller A, Schröder C, Gropmann A, et al. ICU ward design and nosocomial infection rates: a cross-sectional study in Germany. J Hosp Infect . 2017;95:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph A. The impact of the environment on infections in healthcare facilities. Concord, CA: Center for Health Design; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Glind I, de Roode S, Goossensen A. Do patients in hospitals benefit from single rooms? A literature review. Health Policy . 2007;84:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morawska L. Droplet fate in indoor environments, or can we prevent the spread of infection? Indoor Air . 2006;16:335–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urlich R, Zimring C, Quan X, Joseph A, Choudhary R. The role of the physical environment in the hospital of the 21st century a onceinalifetime opportunity. Concord, CA: The Center for Health Design; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker J, Hoffman P, Bennett A, Vos M, Thomas M, Tomlinson N. Hospital and community acquired infection and the built environment–design and testing of infection control rooms. J Hosp Infect . 2007;65:43–49. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(07)60014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rachman S. Fear of contamination. Behav Res Ther . 2004;42:1227–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straus SE, Wilson K, Rambaldini G, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and its impact on professionalism: qualitative study of physicians' behaviour during an emerging healthcare crisis. BMJ . 2004;329:83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38127.444838.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seale H, McLaws M-L, Heywood AE, Ward KF, Lowbridge CP, MacIntyre C. The community's attitude towards swine flu and pandemic influenza. Med J Aust . 2009;191:267–269. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creswell JW. Research Design Qualitative Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis S. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Health promotion practice . 2015;16:473–475. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloomberg LD, Volpe M. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation A Road Map From Beginning to End. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biggerstaff D, Thompson AR. Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): a qualitative methodology of choice in healthcare research. Qual Res Psychol . 2008;5:214–224. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartley JM, Olmsted RN, Haas J. Current views of health care design and construction: Practical implications for safer, cleaner environments. Am J Infect Control . 2010;38:S1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.04.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandrick K. A higher goal. Evidence-based design raises the bar for new construction. Health Facil Manage . 2003;16:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhury H, Mahmood A, Valente M. Advantages and disadvantages of single-versus multiple-occupancy rooms in acute care environments a review and analysis of the literature. Environ Behav . 2005;37:760–786. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch RJ, Englesbe MJ, Sturm L, et al. Measurement of foot traffic in the operating room: implications for infection control. Am J Med Qual . 2009;24:45–52. doi: 10.1177/1062860608326419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EB, Raphael IJ, Maltenfort MG, Honsawek S, Dolan K, Younkins EA. The effect of laminar air flow and door openings on operating room contamination. J Arthroplasty . 2013;28:1482–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wojgani H, Kehsa C, Cloutman-Green E, Gray C, Gant V, Klein N. Hospital door handle design and their contamination with bacteria: a real life observational study. Are we pulling against closed doors? PLoS One. 2012;7:e40171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimring C, Denham ME, Jacob JT, et al. Evidence-based design of healthcare facilities: opportunities for research and practice in infection prevention. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 2013;34:514–516. doi: 10.1086/670220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boone SA, Gerba CP. Significance of fomites in the spread of respiratory and enteric viral disease. Appl Environ Microbiol . 2007;73:1687–1696. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02051-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurst CJ. Microbial and botanical host systems studies in viral ecology. In: Hurst CJ, editor. Defining the Ecology of Viruses. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall CB, Douglas RG, Geiman JM. Possible transmission by fomites of respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis . 1980;141:98–102. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dowell SF, Simmerman JM, Erdman DD, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus on hospital surfaces. Clin Infect Dis . 2004;39:652–657. doi: 10.1086/422652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barker J. The role of viruses in gastrointestinal disease in the home. J Infect . 2001;43:42–4. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2001.0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogler A, Jorgensen J. Windows to the world - doors to space - a reflection on the psychology and anthropology of space architecture. http://www.olats.org/space/13avril/2004/te_jJorgensen.html. Published 2004. Accessed December 18, 2019.

- 31.Cisler JM, Reardon JM, Williams NL, Lohr JM. Anxiety sensitivity and disgust sensitivity interact to predict contamination fears. Pers Individ Dif . 2007;42:935–46. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deacon B, Maack DJ. The effects of safety behaviors on the fear of contamination: an experimental investigation. Behav Res Ther . 2008;46:537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cougle JR, Lee H-J. Pathological and non-pathological features of obsessive-compulsive disorder: revisiting basic assumptions of cognitive models. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord . 2014;3:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zysk E, Shafran R, Williams T. The origins of mental contamination. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord . 2018;17:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lonsdorf TB, Menz MM, Andreatta M, et al. Don't fear ‘fear conditioning': methodological considerations for the design and analysis of studies on human fear acquisition, extinction, and return of fear. Neurosci Biobehav Rev . 2017;77:247–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor S. Anxiety Sensitivity Theory Research and Treatment of the Fear of Anxiety. London, UK: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morse JM. Designing funded qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diegel-Vacek L, Ryan C. Promoting hand hygiene with a lighting prompt. HERD . 2016;10:65–75. doi: 10.1177/1937586716651967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stiller A, Salm F, Bischoff P, Gastmeier P. Relationship between hospital ward design and healthcare-associated infection rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control . 2016;5:51. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0152-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]