1.

In addition to its highly important function as a protective barrier, the skin is a key player in the sense of touch. The latter provides a role that is too often neglected despite its major importance in many aspects, being intimate or social but crucial in the application of cosmetic products or medical procedures. The present review aims at describing the human skin as a connected bio‐electronic tissue, acting as an emitter and receiver in the image of electronic devices such as sophisticated smartphones.

In late 2021, the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine was awarded to D. Julius and A. Patapoutian for their joint successful research on some skin receptor channels that sense heat, pressure, and body position shedding new light on the human sense of touch. 1 , 2 , 3 Indeed, with regard to its very large surface (1.5–2 m2 in adults), skin comprises a vast and dense network of cells and transmitter channels. The human skin can therefore be viewed as a bio‐electronic sensor that covers each µm2 of the skin with such high precision that the image of a tactile screen comes spontaneously to mind. If the sensorial feeling is the primary role of this bio‐electronic skin, conveying centripetal signals (up to the brain), some of this information can be centrifuged, that is, emitted to the environment, being self‐perceived or sent to the “others”. Like the two‐faced Latin God Janus, skin and its neuro‐sensorial organization would then present two faces, acting as both a receiver and a transmitter “antenna”.

The present review, therefore, aims at describing the various skin sensorial facets, appraised at the light of this densely connected neural organization, its dual ability to perform as both a receiver and an emitter, the physics bases of touch, and the challenge of cosmetic products in preserving or maintaining at best its sensorial performance.

Skin is logically first viewed as a body‐protecting tissue, organized in different strata that all act as barriers against external foes or invaders of a different nature (repeated frictions, ultraviolet [UV], microbes, aggressive chemicals, superficial burns, etc.) using different molecular mechanisms of defense. On the second hand, skin can also be seen as a sophisticated electronic/neuronal structure as its neural organization (nerve fibers, corpuscles, and cells) acts, in final, as electron transducers via messenger molecules such as nitric oxide (NO) or peptides of neuronal origin such as Substance P. 4 , 5 , 6

In addition, viewing skin as a biologically designed “electronic” network fits with the embryological origin of some skin cells that derive from the neural crest. Hence, the complex “electronic” organization of the skin grounds on a dense network of fibers differently myelinated (A, C), corpuscles (Pacini, Ruffini, and Meissner), and Merkel cells that all contribute to acting as efficient sensors of different stimuli subjected to epidermal and dermal cells (mechanoreceptors/pressure, heat/cold, roughness/softness, etc.). 7 , 8 These electron‐based signals, of very low voltages and intensities (mV, nA) are transmitted to the brain at speeds ranging from 33 to 75 m/s. 8 , 9 , 10 For example, the pain inflicted by a splinter suddenly inserted in the foot of an adult of 1.8 m reaches the brain within some 30–40 ms. This fast response explains how the painful contact of skin with nettle or the skin immersion in too‐hot water (>45°C) is immediately felt. Hence, when transmitted to the brain cortex, the sense of touch carries two vectors of information, that is, objective (cold/warm and smooth/rough) and hedonistic (pain/pleasure and contentment). 11

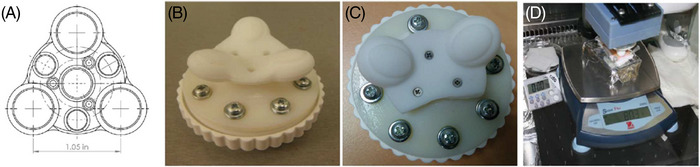

The sense of touch is operational at birth, much before the four other senses. 11 Touch, together with gustatory, requires close contact, inversely to the three others, that is, hearing, olfactory/smell, and vision. From birth to infancy, touch progressively loses its importance with the acquisition of vision and speech. However, during these early times of life, touch owns a complex dimension of important emotional impacts. As stated by Montagu, 11 “Although touch is not per se an emotion, it induces neural, glandular, muscular and mental changes that are close to emotion”. The mental development of human or primate babies appears hampered when their mothers restrain their touch/caresses to their infants. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 In almost all human cultures, caressing a soft baby's skin or an animal comes as a spontaneous expression of care and affection. On such a view, a massage session in adults may own a larger dimension than a sole relaxing or correcting procedure as a possible far remembrance of the early maternal caresses. As individual skin care regimens, touching and massaging are inseparable companions of many cosmetic products (shampooing, skincare, or anti‐aging formulae), from their acquisition to pre‐ and post‐applications. The efficacy of shaving in men or that of a depilatory process on a woman's legs is assessed by an individual/intimate touch. Contact, inseparable from touch, then affords two major assets in the skin/skin relationship: sensing (short term) and massaging (long term), which can be instrumentally modelized. As an example, among others, 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 an instrument was developed, the “Haptic Finger”, that records the skin texture. 19 Applied in vivo to skins of different conditions (atopy, xerosis, psoriasis), the detected values of roughness and hardness were found in good agreement with clinical assessments. With regard to the impact(s) of continuous massaging on the skin, a biophysical approach simulates the effect of a rotating massaging on ex vivo skin explants (see Figure 1), showing how such procedure subtly enhances the synthesis of some dermal components with time according to the frequency (in Hertz) of this massaging instrumental modelling. 20

FIGURE 1.

Home‐made devices designed for mimicking a rotating massage of ex vivo skin explants (part D). From reference 20, courtesy of the authors

Although rather homogeneously distributed along the human body, these “electronic” skin sensors present a higher density (by 4 to 5 times) at the fingertips and lips. 21 Such connected networks, susceptible to slight vary among individuals should naturally lead to different thresholds of sensitivity between subjects. In addition, the differences between passive and dynamic acuity are now better understood. The former, more associated with active touch, (including specific tactile gestures) better discriminate textures. The changes in tactile acuity with age have been recently studied. 22 , 23 Although both studies illustrate the decrease of dynamic tactile acuity with age, associated with the mechanical degradation of the skin's structure, one. 23 suggests that such a drop may be associated with a decreased density of efficient mechanoreceptors (defined as the size of the real contact area with a finger).

It is noteworthy that the same stimulus may lead to variable feelings: what is felt highly painful or pleasant for a given subject may be less felt by another one. It is often believed that the sense of touch in born‐blind subjects is of a higher acuity (their great ability to decipher tiny Braille signs) than sighted persons. However, a study 24 suggests that their acuity does not much differ from that of sighted subjects, implying that the sense of touch can be trained.

Among other senses, touch is an important factor in sensorial studies and is intensely used to describe the surface properties of various industrial products (cosmetics, fabrics, paintings, and glass). In the cosmetic domain, trained panels aim at assessing the sensorial patterns of a product with regard to its physical/rheological properties during its application (sticky, soft, rough, comfortable, slippery, lingering effect, etc.). These sensorial studies are anything but easy for two major reasons. On first‐hand, they require panelists to be selected through various criteria (gender, socio‐economical profile, age, regular users of cosmetic products, visual acuity…) and trained, becoming prone to providing highly reproducible evaluations. On the second hand, their assessments should be further expressed by standardized wordings as the acuity of their sense of touch and their own oral expressions may slightly differ between panelists.

As said above, touch strictly requires physical interaction (contact) of the skin either with itself (skin‐skin contact), with another body, or with an object. Similar to an electronic sensor, the skin's capacity to respond depends on the extent and strength of the contact between two surfaces. This interaction is affected by many different parameters associated with the physical and chemical transformations occurring at the interface. Skin surface roughness, tactile pressure, finger sliding velocity, environmental conditions, temperature, or skin surface compliance are examples of conditions that occur during a touch gesture. All these factors affect the type of mechanical or thermal stimulus transferred (and eventually detected) by the human somatosensory system.

Important efforts have been dedicated to grasping the frictional characteristics of the skin. Adams et al. 25 looked at the mechanical laws that contribute to skin friction and in particular the relative importance of skin's deformation compared with intrinsic surface characteristics as adhesion. Loading pressure during touch efficiently can tune between these two situations. In many cases, for example, low loads are voluntarily chosen when experimenting surface textures on skin (hairy or not). On the contrary, higher loads will mask these features and might instead lead to a somewhat painful feeling, during a massage for example.

Apart from the load, the contact area is a key parameter to define the way the contact happens during a mundane touch gesture on a particular garment. Humans are very sensitive to surface topography and two studies have tried to understand, for example, the effect of textiles on touch. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 The particular surface pattern of linear grooves of the back of the hands (micro‐relief), is a particular human “texture”. The micro‐relief, together with other larger deformations such as wrinkles or folds, changes with age, with an increase in the depth of the lines that conditions the stimuli to be received/felt by the elderly. 26 More striking differences are found among anatomical sites. The finger pad is an example of a regularly organized texture (fingerprints) well‐designed to optimize the generation of vibrations during dynamic touch, as shown by Scheilbert. 27

Physicists studied how friction, during touch, induces vibrations on the skin, using experiments and simulations. Mechanical models to simulate skin have been proposed to better understand this propagation. Many of these models use engineering tools (such as finite elements simulations) or, in other cases, try to incorporate the mechanical characteristics and structure of the skin at the cellular level. Experiments tried first to understand how vibrations distribute and progress in the finger and affect the different mechanoreceptors. In fact, the frequency of the vibration generated by the fingerprints falls within the optimal range of sensitivity of Pacinian afferents that mediate the coding of fine textures. Interestingly, vibration can also propagate far from the original area of contact. Shao et al. 28 described in detail how these vibration patterns can extend all over the hand after touching an object within a few milliseconds after the original contact. This opens many opportunities in robotics or in the medical rehabilitation of hand injuries.

With regard to cosmetics, the introduction of an ingredient in a given formula may affect all above mentioned aspects during a touch gesture as it may act either as a lubricant or, on the contrary, slow or drag the movement. The so‐called “sensorial” evaluation of touch is commonly used to fill the gap between the skin/product physical parameters and perception, onto which skin hydration has a clear influence. 29 Such skin‐brain dialog has been approached by fRMI, showing how some brain areas become activated by a tactile simulation. 30

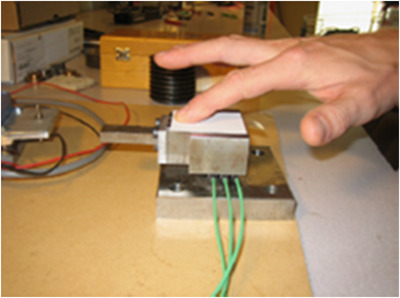

Psycho‐physical methods are on the contrary more oriented to the characterization of perception thresholds and differences. They focus on stimuli‐response phenomena, i.e. when or how much a particular perception is felt or is different from another subject. In general, such approaches provide quantitative data that can be compared to and ideally correlated with, individual physical quantities or combinations thereof. These methods have been applied to assess the roughness of printing papers. 31 (see figure 2) or on the determination of tactile acuity in the elderly. 22

FIGURE 2.

Electronic device used for assessing the surface properties (roughness and softness) of a printing paper. From reference 31, courtesy of the authors

Like smartphones, this “bio‐electronic” skin acts as both a receiver and an emitter. 32

-

i)

As a permanently connected receiver , a healthy skin transmits to the brain cortex a vast amount of various information's through molecular/electronic complex mechanisms that are in many cases still unknown, especially in their translation to and by the brain: why and how a copious warm shower quickly leads to the feeling of better well‐being in almost all of us? By which mechanisms a basic making‐up procedure rapidly increases the amount of IgA in saliva? 33 Even under contactless conditions, this “bio‐electronic” skin seems to respond to external stimuli: the perception of odors (pleasant or not) influences the skin conductance. 34 or stress induces changes in the skin barrier function. 35 Such examples justify the term neuro‐endocrine skin system. 4 , 5 , 6 In the dermatological domain, sensing by finger the relief of some skin surface elements such as dark spots is a crucial decision‐maker: the most feared pigmented skin symptom (melanoma), of inhomogeneous color, presents no relief, inversely to other pigmented elements such as seborrheic keratitis or benign nevi. Of note, the threshold of detection of superficial skin or hair elements by the sense of touch is low, in the micrometer range (2–5 µm). Caucasian women, regular users of shampoos, were shown prone to detecting (under blind conditions) hair surface defects (uplifted scales by 2–5 µm) along their hair shafts and were able to detect the different diameters between “normal” and “fine” hairs, by an average 9 µm measured difference. 36 , 37

Apart from skin‐skin contacts, the interaction of skin with external elements is subtly detected by the neural cutaneous connected network. Commonly experienced examples are many: the close contact between skin and a wool‐based fabric is often a source of the itch. The same holds true with regard to tiny hair debris unavoidably deposited onto the neck by a basic haircut or sand particles still stuck to the skin after beaching. Back to the example of exposure to UV and its subsequent inflammatory process, the contact between sunburned skin with bed sheets is an electronic nociceptive message sent to the brain cortex. From a dermatological aspect, the peeling process uses Alpha Hydroxy Acids at high concentrations (50% to 70%). Although beneficial since leading later to a “rejuvenated” skin, is a source of provisory but uncomfortable feelings during their application (an approx. 15 min contact followed by a copious rinse).

-

ii)

As an emitter , the facial skin permanently sends messages to oneself and to “others”. These messages include a vast category of signals such as fatigue, perceived age, ethnicity, mood, health, or stress. 32 Like SMS, these signals are almost immediately conveyed: some people may flush and blush within a second, in reaction to a provocative event, transmitted by a small molecular messenger (NO). Inversely, a sudden fear rapidly induces paler facial skin that is immediately detected by the other's: “What happens to you? You are so pale!”. Touching the forehead of a subject who complains of fever (Flu and infectious diseases) is a spontaneous primary check performed by every human with rather good reliability. This reflex becomes crucial, lived by all parents, in the case of non‐speaking babies. A skin redness ‐erythema‐ induced by exposing non‐protected skin to a high flux of UVs is rapidly observed in faired‐skin subjects (15–20 min). It comes as a precursor alarm, much before the pain induced by the painful inflammatory reaction (sunburn), felt some 6–8 h post‐exposure. In brief, a salutary intimate message is sent to the brain by the connected skin neural network: “Keep off the sun or things will get worse!”.

As suggested before, the innate threshold of skin sensitivity may vary among individuals of comparable ages. Indeed, a significant part of human subjects (30%–50%) self‐declare complaining from sensitive (reactive) skin, more frequently reported by women than men. This syndrome, free from noticeable clinical signs should not be mixed up with an allergic reaction. 38 As described by dermatologists, the Angry Back Syndrome or Koebner reaction owns, although unfrequent, a true identity. The sensitive skin condition was extensively studied and reviewed by Jourdain et al. 39 A survey made by dermatologists on hundreds of Caucasian women with self‐declared facial sensitive skin recorded 13 major factors spontaneously expressed as most exacerbating their skin sensitive condition. 40 These were, expressed as a percentage: cold (66%), stress (61%), sun (51%), soap (42%), wind (42%), swimming pool water (40%), temperature variations (38%), warm shower/weather (28%), frictions with garments (28%), cosmetics (28%), menses (24%), sweat (23%), and aerial pollution (18%). Such a variety of so different factors (external or physiological) that can admix (a cold wind, stress/sweat, and sun/pollution) summarizes the complexity of the sensitive skin syndrome. As research objectives, attempts to differentiate sensitive from non‐sensitive subjects were carried out, in vivo, by topical applications of either Capsaicin (the spicy ingredient of Chili) at 0.05% or a 10% lactic acid solution onto small skin areas and recorded with time the sensorial feelings (itching, burning, and stinging) of subjects through a 0–5 analogical scale. 39 , 40 , 41 Of note, Capsaicin was the chosen model of D. Julius and A. Patapoutian. Whatsoever, these studies allowed differentiating these two cohorts on both the amplitude of the nociceptive feelings and their decay with time. A decisive study. 42 using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), confirmed that subjects complaining of facial sensitive skin do express a reality. 15 women with self‐declared sensitive skin were compared to 15 self‐women not particularly concerned by such syndrome. After the application (at random) of a 10% lactic acid solution (a mild irritant) on one aisle of the nose or physiological saline water, used as control. Subjects were further submitted to fMRI. Results were of a clear significance: in both cohorts, one brain region became activated by lactic acid, of a larger surface in sensitive subjects, and spread to another brain region that was found very weakly activated in control subjects. In brief, subjects with sensitive/reactive skin present distinct neurophysiological patterns than those of non‐skin‐sensitive subjects. From a practical viewpoint, this study sends a clear message to all researchers in the dermatological and cosmetic domains: “Listen to patients or consumers: they very likely express a physiological reality”.

Cosmetic skin care formulations are destined, by nature, to be closely “connected” to various skin sites under different conditions (large or small areas, leave‐on or rinsed).

Their development necessarily includes sensorial studies that define the quality of the contact when the product is spread onto the skin (i.e. slippery, stickiness, freshness, comfort, oily, etc.). These studies often show gender‐related variability. For example, very oily formulae are rarely tolerated by men, inversely to women.

Along a life span, this complex skin neuro‐cellular network unavoidably affronts various challenging events (aging/photoaging, skin disorders or diseases, cuts, burns/sunburns, etc.). While some may be nociceptive (burns, cuts, psoriasis, eczema, xerosis, skin infection, dandruff..) where itch/pruritus is their common denominator, some others are sensorially silent (aging, acne, vitiligo, melasma etc.). As daily companions, skincare or hair care products become precious allies in alleviating or preventing some challenging assaults. Examples are many and are the objects of a vast literature. They fully respond to the 1976 E.U. definition of cosmetics, where the last sentence “with a view…of protecting or keeping them (the skin and its appendages) in good condition” is a well‐defined objective. In short, protecting both the skin structure and its function by appropriate cosmetic daily care regimens is the ‘raison d’être’ of cosmetic activity. This obviously includes the preservation of the neuro‐physiological domain where every consumer should feel “comfortable” in his/her own skin as some of the previously quoted events may hamper its efficiency. The sore feeling of itchy xerotic/dry skin rapidly vanishes by applying an efficient hydrating cream or lotion. When restored to normal conditions, the neuro‐cellular skin network responds almost immediately. The example of dandruff is another facet of the mission of cosmetic products: the use of shampoos containing anti‐fungal agents (ZPT, selenium disulfide, and piroctone olamine) shows that the scalp itch/pruritus vanishes before that of the abnormal desquamative process.

To summarize, regardless of the precise neuro‐sensorial mechanisms involved in the transmission of pain or contentment, the effects of cosmetic products on a true and crucial sensorial dimension, coupled with their desired adorning/aesthetical impacts. These are indeed faithful companions in respecting and maintaining the so‐important human sense of touch that ensures a constant skin‐brain dialog.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

GSL is working for L'OREAL involved in research activities. DSL, private consultant financed by L'OREAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

A Tribute to D. Julius and A. Patapoutian, Nobel Prize Awards, 2021

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data is available in the references listed in the article

REFERENCES

- 1. Logan DW. Hot to touch: the story of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Dis Model Mech. 2021;14(10):dmm049352. 10.1242/dmm.049352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zimmerman A, Bai L, Ginty DD. The gentle touch receptors of mammalian skin. Science. 2014;346(6212):950‐954. 10.1126/science.1254229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Owens DM, Lumpkin EA. Diversification and specialization of touch receptors in skin. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(6):a01656. 10.1101/cshprspect [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Skobowiat C, et al. Sensing the Environment: regulation of local and global homeostasis by the skin's neuro‐endocrine system. Adv Anat Embryol. Cell Biol. 2012;212:1‐115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Slominski AT, Wortsman J, Paus R, et al. Skin as an endocrine organ: implications for its function. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2008;5:e137‐e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arck PC, Slominski AT, Theoharides TC, et al. Neuroimmunology of stress: skin takes center stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1697‐1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gillespie PG, Walker RG. Molecular basis of mechanosensory transduction. Nature. 2001;413,194‐202, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lumpkin EA, Caterina MJ. Mechanisms of sensory transduction in the skin. Nature. 2007;445:858‐865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lederman SJ, Klatsky RJ. Haptic perception: a tutorial. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2009;71:1439‐1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mc Glone F, Reilly D. The cutaneous sensory system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:148‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Montagu A. Touching: The Human Significance of the Skin. Harpers Collins Publishers; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ostfeld BM, Smith RH, Hiatt M, et al. Maternal behavior toward premature twins: implications for development. Twin Res. 2000;3(4):234‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu C, Liu J, Lin X. Effects of touch on growth and mentality development in normal infants. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2001;81(23):1420‐1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walker CD. Maternal touch and feed as critical regulators of behavioral and stress responses in the offspring. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52(7):638‐650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veijgen NK. Masen MA, Van der Heide E. A novel approach to measuring the frictional behavior of human skin in vivo. Tribol Int. 2012;54:38‐41. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abdouni A, Vargiolu R, Zahouani H. Impact of finger biophysical properties on touch gestures and tactile perception: aging and gender effects. Sci Rep. 2018. 10.1038/s41598-018-30677-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Kuilenburg J, Masen MA, Groenendijk MNW, et al. An experimental study on the relation between surface texture and tactile friction. Tribol Int. 2012;48:15‐21. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gerhardt L‐C, Strassle V, Lenz A, Spencer N, Derler S. Influence of epidermal hydration on the friction of human skin against textiles. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5(28):1317‐1328. 10.1098/rsif.2008.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka M, Leveque JL, Tagami H,, et al. The “Haptic Finger”‐ a new device for monitoring skin condition. Skin Res Technol. 2003;9(2),131‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caberlotto E, Ruiz L, Miller Z, et al. Effects of a skin massaging device on the expression of human dermis proteins and in vivo facial wrinkles. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lederman SJ, Abbott SG. Texture perception: studies of intersensory organization using a discrepancy paradigm and visual versus tactual. J Exp Psychol Hum Perception Perform. 1981;7:902‐915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Skedung L, El Rawadi C, Arvidsson M, et al. Mechanisms of tactile sensory deterioration amongst the elderly. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abdouni A, Vargiolu R, Zahouani H. Impact of finger biophysical properties on touch gestures and tactile perception. Aging and gender effects. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12605. 10.1038/s41598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heller MA. Texture perception in sighted and blind observers. Percep Psychophys. 1989;45:49‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adams MJ, Johnson SA, Lefevre P, et al. Finger pad friction and its role in grip and touch. J R Soc Interface. 2012;10(80):20120467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zahouani H, Djaghloul M, Vargiolu R, et al. Contribution of human skin topography to the characterization of dynamic tension during senescence. Morpho‐mechanical approach. J Phys Conf Ser. 2014;483:012012. doi.org/10.1088. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scheilbert J, Leurent S, Prevost A, et al. The role of fingerprints in the coding of tactile information probed with a biomimetic sensor. Science. 2009;323(5920):1503‐1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shao Y, Hayward V, Visell Y. Spatial patterns of cutaneous vibration during whole‐hand haptic interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(15):4188‐4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gerhardt LC, Strassle V, Lorenz A, et al. Influence of epidermal hydration on the friction of human skin against textiles. J R Soc, Interface. 2008;5(28):1317‐1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Querleux B, Gazano G, Mohen‐Domenech O, Jacquin J, Burnod Y, Gaudion P, Jolivet O, Bittoun J, Benali H. Brain activation in response to a tactile stimulation: functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) versus cognitive analysis. Int J Cosmet Sci.. 1999;21(2):107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skedung L, Danerlöv K, Olofsson U, et al. Tactile perception: finger friction, surface roughness and perceived coarseness. Tribol Int. 2011;44:505‐512. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bernard BA, Saint Leger D, Leclaire J. The multifaceted human facial appearance: beyond skin and hair. J Dermatol Cosmetol. 2018;2(2):138‐145. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kan C, Kimura S. Psycho‐Neuroimmunological Benefits of Cosmetics. Proc 18th IFSCC Meeting. 1994;31:769–784. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bensafi M, Rouby C, Farget V, et al. Autonomic nervous‐system responses to odours: the role of pleasantness and arousal. Chem Senses. 2002;27:703‐709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Altemus M, Rao B, Dhabar FS, et al. Stress‐induced changes in the barrier function in healthy women. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:309‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Galliano A, Kempf JY, Fougere M, et al. Comparing touch sense of naïve and expert panels through treated hair swatches: which associated wordings correlate with hair physical properties? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2017;39:653‐663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bouabache S, Galliano A, Litave P, et al. What is a Caucasian “fine” hair? Comparing instrumental measurements, self‐perceptions and assessments from hair experts. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(6):581‐588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. De Lacharriere O, Jourdain R, Bastien P, et al. Sensitive skin is not a subclinical expression of contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44(2):131‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jourdain R, Maibach HI, Bastien P, et al. Ethnic variations in facial skin neuro‐sensitivity assessed by capsaicin detection methods. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;308(9):325‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Willis CM, Shaw S, de Lacharriere O, et al. Sensitive skin: an epidemiological study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145(2):1258‐263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jourdain R, Bastien P, de Lacharriere O, et al. Detection thresholds of capasaicin: a new test to assess facial skin sensitivity. J Cosmet Sci. 2005;56(3):153‐166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Querleux B, Dauchot K, Jourdain R, et al. Neural basis of sensitive skin: an fMRI study. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14(4):454‐461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available in the references listed in the article