The clinical definition of symptom sequelae of COVID-19 changed over time. Till March 2021, ongoing symptoms for more than four weeks were classified as post-COVID-19 symptoms (PCS),1 later, on October 2021, the WHO working group defines post-COVID-19 condition (PCC)2 as the ongoing symptoms of COVID-19 or newly developed symptoms noted after twelve weeks of initial SARS-CoV-2 infection and these symptoms persist for a minimum of two months, and no other medical diagnosis can explain these symptoms. Several studies have demonstrated the prevalence of PCS as 22.4%, 51%, and 43%, in Bangladeshi,3 Asian4, and Global4 populations respectively. The prevalence of PCC is still in a dilemma because none of the reported symptoms matches WHO criteria.2 A meta-analysis4 of symptoms diagnosed PCC as symptoms persistent after 4 weeks of COVID-19, other Epidemiological studies from Bangladesh,3 India,5 United Kingdom,6 and the United States7 diagnosed PCC with symptoms noted after 12 weeks of COVID-19 but not persistent for a minimum of two months duration. So, there is a research gap in the epidemiology of PCC according to WHO criteria. PCC causes relapsing, remittent episodes of symptoms causing episodic disabilities,4,6 but the interaction between disease and disability induced by PCC is still unclear.

To figure out the real scenario of PCC and to characterize the disease and episodic disabilities induced by PCC, a large-scale population-based household screening of 12,628 retrieved contacts of 12 weeks old COVID-19 cases confirmed by Real-time polymerase chain reaction test (RT-PCR) was conducted between July and December 2021 in Bangladesh. Diagnosis of PCC was performed according to WHO criteria.2 The COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS)8 was used to elucidate the clinical scenario (Supplementary File 1) and the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) was used to determine the disease induced by PCC. Additionally, to determine the spectrum of disability according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), 19 indicators under five ICF domains were assessed through the sub-scales of six structured and validated outcome tools (Supplementary File 2).

The study revealed higher PCS 0.19 [95% CI: 0.19–0.20] (N = 2507) compared to PCC 0.04 [95% CI: 0.041–0.048] (N = 563) in Bangladeshi people. Fifteen symptoms were found as PCS in our study, and thirteen of them were diagnosed as PCC according to WHO clinical case definition.2 Major clinical symptoms associated with PCC (with ICD-10 code) was fatigue (R53. 83) .221, depression (F32.9) .218, cough (R05. 9) .219, pain (R52) .219, weakness (R53) .217, anxiety (F40) .214, insomnia (G47) .211, dyspnea (R06.0) .208, cognitive problems (R41. 84) .201, dizziness (R42) .172, PTSD (F43) .147, and palpitation (R00.2) .147. The population proportion of these PCC is supplied in Supplementary File 3. These symptoms are also evident in previous studies,3, 4, 5, 6, 7 so the ICD-10 codes of these symptoms can be sub-categorized under PCC, which has been coded as “U-09” by the WHO.9

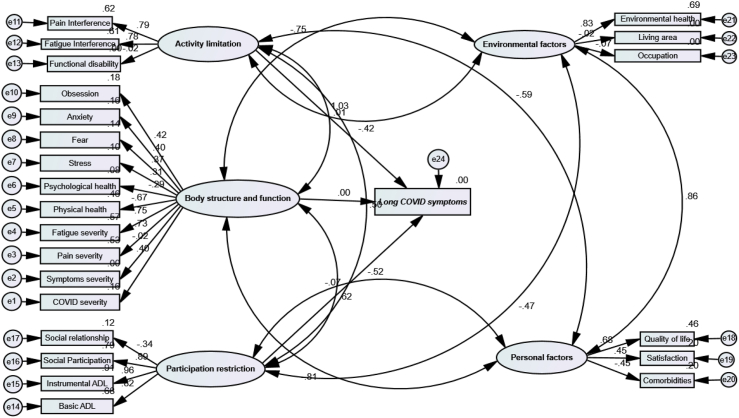

In the ICF lens, functional disability was significant in breathlessness, cough, fatigue, pain, anxiety, depression, and insomnia. People with poor physical health, psychological health, and social participation in WHOQoL- Bref had breathlessness, cough, pain, anxiety, depression, and insomnia. The inter-relationship of Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC), episodic functional disability, and quality of life is supplied in Supplementary File 4. For detailed investigation, structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed to find out the interaction among ICF domains with PCC (Fig. 1). SEM showed a significant association among the domains of the ICF model, which was not observed in earlier studies. The impairments in body structure and function directly affect the activity limitation and participation restriction for a person having PCC or long COVID. With this consequence, the significant impairments in activity limitations and participation restrictions can affect the person's personal and environmental factor domains in ICF.

Fig. 1.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) of interaction among ICF domains with Post-COVID-19 condition (PCC).

This study presented a hypothetical relationship between disease course and episodic disability in PCC. We have identified 13 diseases having ICD-10 codes which can be categorized as PCC under U-09. Though the study is not conclusive and the result might not be generalized because of low ICC values and Deff in sample size calculation, the clinical implication outweighs the limitations. Future systematic reviews or meta-analyses might consider using the cut-off duration ≥12 weeks Post-COVID and individual symptom duration ≥2 months for defining PCC or long COVID. We also highlight the need for future studies on the disease burden of PCC addressing the existing research gap10 on its episodic pattern, longitudinal disease course, and outcome of multidisciplinary rehabilitation.

Contributors

S.K.C., K.M.A.H, R.S, I.K.J.: concept, design, definition of intellectual content, analysis of data, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, manuscript review, final approval, and guarantor. S.K.C., K.M.A.H, R.S, S.A, I.K.J.: literature search, manuscript editing, manuscript review, data acquisition, data analysis, and final approval.

Data sharing statement

Relevant data is available in the paper, the additional request for data should be addressed to the corresponding author (ikjahid_mb@just.edu.bd).

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Tofajjal Hossain Tuhin and Ahamadullah-hil-Galeb for their contribution to preparing the manuscript. We also acknowledge the Directorate General of health services (DGHS) of Bangladesh for the permission support in conducting the household survey.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100234.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Long covid: current definition. Infection. 2021;50(1):285–286. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01696-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization A clinical case definition of post covid-19 condition by a Delphi Consensus, 6 October 2021. 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345824

- 3.Hossain M.A., Hossain K.M., Saunders K., et al. Prevalence of long covid symptoms in Bangladesh: a prospective inception cohort study of covid-19 survivors. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C., Haupert S.R., Zimmermann L., Shi X., Fritsche L.G., Mukherjee B. Global prevalence of post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or long covid: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(9):1593–1607. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayoubkhani D., Bermingham C., Pouwels K.B., et al. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after covid-19 vaccination: community based cohort study. BMJ. 2022:377. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sivan M., Parkin A., Makower S., Greenwood D.C. Post-COVID syndrome symptoms, functional disability, and clinical severity phenotypes in hospitalized and nonhospitalized individuals: a cross-sectional evaluation from a community COVID rehabilitation service. J Med Virol. 2022;94(4):1419–1427. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bull-Otterson L., Baca S., Saydah S., et al. Post–COVID conditions among adult COVID-19 survivors aged 18–64 and≥ 65 years—United States, March 2020–November 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(21):713. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7131a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sivan M., Halpin S., Gee J. Assessing long-term rehabilitation needs in COVID-19 survivors using a telephone screening tool (C19-YRS tool) Adv Clin Neurosci Rehab. 2020;19(4):14–17. doi: 10.47795/nele5960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz J.V., Herridge M., Bertagnolio S., et al. Towards a universal understanding of post COVID-19 condition. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(12):901. doi: 10.2471/BLT.21.286249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Mahoney L.L., Routen A., Gillies C., et al. The prevalence and long-term health effects of long Covid among hospitalised and non-hospitalised populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;55 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.