Abstract

Background

COVID-19 affected testing for HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) worldwide. We aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on community-based voluntary, counselling and testing (CBVCT) services for those infections in the WHO European Region.

Methods

An online survey was distributed between 14 October and 13 November 2020 to testing providers in the WHO European Region. Key questions included: impact on testing volume, reasons for this impact, measures to mitigate, economic effects, areas where guidance or support were needed. A descriptive analysis on data reported by CBVCT services was performed.

Results

In total, 71 CBVCT services from 28 countries completed the survey. From March to May 2020, compared to the same period in 2019, most respondents reported a very major decrease (>50%) in the volume of testing for all the infections, ranging from 68% (Chlamydia) to 81% (HCV), and testing levels were not recovered during post-confinement. Main reasons reported were: site closure during lockdown (69.0%), reduced attendance and fewer appointments scheduled (66.2%), reduced staff (59.7%), and testing only by appointment (56.7%). Measures implemented to mitigate the decreased testing were remote appointments (64.8%), testing by appointment (50.7%), referral to other sites (33.8%), testing campaigns (35.2%) and promotion of self-testing (36.6%). Eighty-two percent of respondents reported a need for guidance/support.

Conclusion

Results suggest that people attending CBVCT services experienced reductions in access to testing compared to before the pandemic. National governmental agencies need to support European CBVCT services to ensure recovery of community counselling and testing.

Introduction

Early diagnosis and linkage to care for HIV, viral hepatitis and sexual transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a key challenge in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) European Region. Significant HIV transmission continues, with 136 000 people living with HIV being diagnosed in 2019. This number increased by 19% in the WHO European Region over the last decade, while declining by 9% among countries in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) over the same period. This difference among the regions is mainly due to the continuous decrease in the West and the overall stabilising trend in the East with some countries reporting annual increases in new HIV diagnoses. Additionally, one in five people living with HIV do not know their status and 53% of new HIV infections are diagnosed late.1 In the EU/EEA in 2017, only 20% of people living with hepatitis B (HBV) and 27% of people living with hepatitis C (HCV) were diagnosed.2 In addition, STIs are increasing in several countries, with 23 million incident cases of four curable STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis) among adults (15–49 years old) in the European Region.3 In 2019, the number of reported STIs increased by 9% for chlamydia, 55% for gonorrhoea, 25% for syphilis and 75% for lymphogranuloma venereum relative to 2015.4 As all these infections share common modes of transmission and social determinants, and their disease burdens overlap among specific populations, an integrated approach to prevention and testing is critical.3,5

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has impacted health systems, disrupting important services for global health priorities such as HIV, and impacting global efforts to end the HIV, viral hepatitis and STI epidemics.6,7 These disruptions were due to several factors, mainly the quarantine measures and transportation lock downs implemented in most of the WHO European Region countries from March to May 20208 which increased the difficulty to access HIV, viral hepatitis and/or STIs services and in some cases meant the closure of specifics services;9 shortages of antiretrovirals because of shutdowns by certain drug manufacturers10 and relocation of healthcare workers providing care to PLWH to care for COVID-1 patients.11

Community-based voluntary counselling and testing (CBVCT) services have shown to contribute to early diagnosis of new HIV cases, especially among key populations.12–15 CBVCT services can reach key populations at higher risk of HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs such as gays, bisexuals and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), sex workers, people who inject drugs and migrants.16,17

CBVCT services were specially affected by the confinement measures established in most of the European countries, with many of them being forced to close during the first confinement period, as they were not considered essential services, and with other many services being suspended.9,18 Considering the important role of CBVCT services for key and vulnerable populations, this suspension of services could have affected access to HIV, viral hepatitis and STI testing and other preventive community-based services for these populations.

A consortium of partners,19 led by the EuroTEST initiative, including regional European and international organisations representing community, health care and public health institutions developed an online survey to assess the impact of COVID-19 on testing services for HIV, viral hepatitis and STI in the WHO European Region. The main objective of the survey was to document the impact of COVID-19 in testing for HIV, HBV, HCV, Chlamydia, syphilis and gonorrhoea, among the different actors of the testing response.20

This study aimed to assess the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on community-based testing for HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs in the WHO European Region from March to August 2020.

Methods

Study setting and participants

The survey was addressed to a wide range of actors involved in the provision of testing services in the 53 countries of the WHO European Region (laboratories, primary care units, secondary level care clinics, community sites and national level public health institutions or ministries of health). For this particular study, the data of CBVCT respondents were analysed.

Online survey

The online survey (Supplementary table S1) was distributed through the consortium members’ respective networks between 14 October and 13 November 2020. Regarding dissemination at a community level, the survey was distributed through several civil society networks (Supplementary table S2) disseminating the link among its members and/or sharing it in their social media.

Although the survey was addressed to different actors involved in the provision of tests, there were specific questions addressed to each type of respondent. Key questions used for this analysis comprised: the profile of respondents (type of centre, number of testing sites and country), which infections the survey response was covering, the quantitative impact on testing volume per each infection [in broad categories of percentage decrease/increase: decreased by >50%, 26–50%, 11–25%; stable (±0–10%); increased by 11–25%, 26–50%, >50%], main reasons for the observed impact and the impact level (Major, Medium, Minor), measures put in place to mitigate this impact, changes or adaptations on other services offered, economic effects, COVID-19 testing integration and areas where guidance or support were needed.

Data referring to the lockdowns in each country was obtained from ECDC.8

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed on data from responding CBVCT services on: the profile of respondents (infections tested for, main key groups/communities that access services, services offered in addition to testing and movement restrictions imposed); change in the number of tests performed during lockdown period and the months after compared to the same period of the previous year; reasons for these changes; measures put in place to mitigate the effect on testing; challenges for linkage to care; new or increased needs reported by the clients; changes or adaptations to the other services offered; economic effects on the organisation/service; COVID-19 testing integration and support needs going forward. Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare EU vs. non-EU countries.

Data analysis was performed using Stata™, version 15.

Results

Characteristics of the participating CBVCT services

A total of 71 CBVCT services providing testing for at least one of these infections, representing 28 different countries in the WHO European Region (19EU/EEA and 9 non-EU/EEA) (Supplementary table S3) responded to the survey. Most respondents defined their CBVCT service as a non-governmental organisation (NGO) or community-based organisation (CBO) (93.0%); three as a coalition of NGOs or an umbrella organisation for NGOs and one as an organisation with several harm reduction centres. A proportion of 38.0% of the NGO/CBO represented more than one testing site. In total, the 71 survey responses represented around 150 testing sites.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the participating CBVCT services. Almost all respondents provided testing for HIV (97.2%). Most of them also provided testing for syphilis (73.2%) and HCV (71.8%), with less reporting testing for HBV (42.3%), Gonorrhoea (32.4%) and Chlamydia (31.0%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participating sites (N = 71)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Type of setting | |

| NGO/CBO | 66 (92.96) |

| Coalition of NGOs/umbrella organisation for NGOs | 3 (4.23) |

| Harm reduction sites | 1 (1.41) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.41) |

| Infections tested for | |

| HIV | 69 (97.18) |

| Hepatitis B | 30 (42.25) |

| Hepatitis C | 51 (71.83) |

| Syphilis | 52 (73.24) |

| Chlamydia | 22 (30.99) |

| Gonorrhoea | 23 (32.39) |

| Population served | |

| Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men | 51 (71.83) |

| People living with HIV | 41 (57.75) |

| Young people | 34 (47.89) |

| General population | 32 (45.07) |

| Transgender people | 30 (42.25) |

| Sex workers | 30 (42.25) |

| People who inject drugs | 30 (42.25) |

| Migrants | 29 (40.85) |

| Other | 3 (4.23) |

| Services offered | |

| Social support | 55 (77.46) |

| Referral/support in linkage to care or confirmatory testing | 55 (77.46) |

| Remote consultations (phone or email) | 49 (69.01) |

| Mental health support | 45 (63.38) |

| Self-testing (offering or referring) | 26 (36.62) |

| Needle and syringe exchange | 23 (32.39) |

| PrEP (initiation, provision or monitoring) | 20 (28.17) |

| Partner notification | 16 (22.54) |

| Home-based sampling | 5 (7.04) |

| Opioid substitution therapy | 4 (5.63) |

| Other | 15 (21.13) |

| Movement restrictions imposed that could affect service access | |

| Yes | 70 (98.59) |

| No | 1 (1.41) |

| Type of lockdown or social restrictionsa | |

| Mandatory ‘stay-at-home’ orders for the general population | 46 (65.71) |

| Recommended/optional ‘stay-at-home’ orders for the general population | 52 (74.29) |

| Optional ‘stay-at-home’ recommendations for risk groups or vulnerable populations | 37 (52.86) |

| Closure of public spaces | 48 (68.57) |

Notes: NGO: non-governmental organisation; CBO: community-based organisation; HIV: Human immunodeficiency syndrome; PrEP: pre-exposition prophylaxis.

Each respondent could indicate more than one reason or new measure, hence the totals per column is higher than the number of respondents.

Most sites (71.8%) serve GBMSM, as the main group, followed by people living with HIV (57.8%). Multiple sites also report serving young people (47.9%), transgender people (42.3%), sex workers (42.3%), people who inject drugs (42.3%), migrants (40.9%) and the general population (45.1%). In addition to testing, the main services offered by responding CBVCT services are social support (77.5%), referral/support in linkage to care or confirmatory testing (77.5%), remote consultations (69.1%) and mental health support (63.4%).

Regarding the lockdown measures imposed by governments, in all participating CBVCT services’ countries but one (98.6%), there were movement restrictions imposed that could affect access to their services, with 46 respondents (65.7%) having mandatory ‘stay-at-home’ orders for the general population in their countries; 52 respondents (74.3%) had recommended/optional ‘stay-at-home’ orders for the general population and 37 (52.9%) had optional ‘stay-at-home’ recommendations for risk groups or vulnerable populations (table 1).

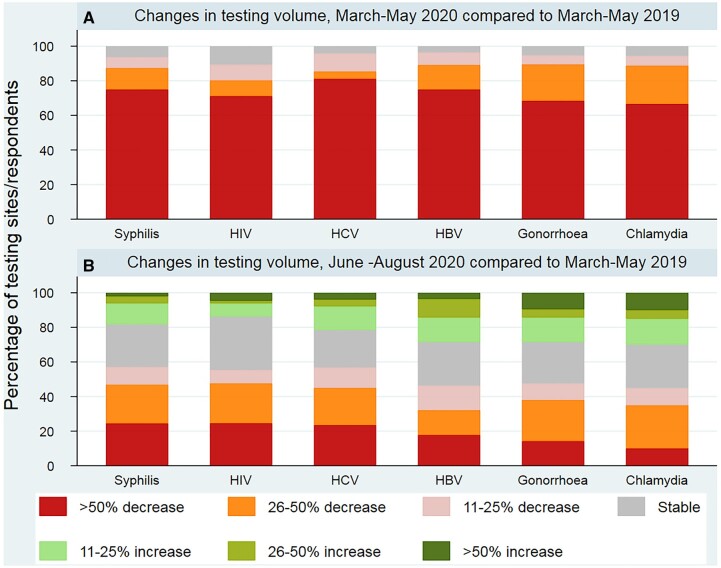

Impact on testing

In the period of the first wave of COVID-19, from March to May 2020, compared to the same 3 months in 2019, there was a considerable decrease in testing (figure 1). Almost all respondents reported a decrease in the volume of testing for all the infections during that period (between 89.4% and a 96.4% depending on the infection), with 68% (for Chlamydia) and 81% (for HCV) reporting a very major decline (more than 50%) compared to the same period in 2019. No differences among EU vs. non-EU countries were found (Supplementary table S4). Most respondents still observed overall testing volume decreases from June to August 2020 compared to 2019, although the degree of disruption was less severe (between 10 and 25% reporting a ≥ 50% decline), and with some sites reporting increases in testing volume (between 13.9 and 30.0% depending on the infection).

Figure 1.

Changes in testing volume for HIV, HBV, HCV and STIs (chlamydia, syphilis and gonorrhoea) by infection and category of change in (A) March–May 2020 and (B) June–August 2020, compared with March–May 2019 in 28 WHO European Region countries (n = 71 respondents)

The most frequently reported reasons for the observed decreases in testing volume were: site closure during lockdown (69.0%), reduced attendance and fewer appointments scheduled (66.2%), reduced staff in site (59.7%) and testing only by appointment (no ‘drop-in’ service) (56.7%) (table 2).

Table 2.

Reasons for observed declines in testing volume and measures implemented and planned to restore testing provision (n = 71)

| Reasons for observed declines in testing volume | Major/Medium | Minor/No decrease | Not applicable/Do not know |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Site(s) closed during lockdown | 49 (69.01) | 12 (17) | 10 (14) |

| Staff re-allocated to support COVID-19 | 13 (19.70) | 20 (30) | 33 (50) |

| Reduced staff in site | 40 (59.70) | 18 (27) | 9 (13) |

| Fewer appointments scheduled/reduced attendance | 45 (66.18) | 15 (22) | 8 (12) |

| Fewer serological samples drawn and sent to the laboratory/fewer referrals to blood draw/testing | 14 (20.90) | 18 (27) | 35 (52) |

| No ‘drop-in’ service (only testing by appointment) | 38 (56.72) | 17 (25) | 12 (18) |

| Fewer referrals to your site | 16 (25.00) | 21 (33) | 27 (42) |

| Changes in financing system | 11 (16.42) | 19 (28) | 37 (55) |

| Stock-out of test kits, tubes, reagents or consumables | 4 (6.06) | 31 (47) | 31 (47) |

| Triaging of patientsa | 18 (26.87) | 23 (34) | 26 (39) |

| Moved to telemedicine/remote consultations | 26 (38.81) | 23 (34) | 18 (27) |

| Other | 7 (21.88) | 4 (13) | 21 (66) |

|

| |||

| Measures implemented and planned to implement to restore testing provision | Measures put in place to restore the provision of tests | If not currently offered, planned measures to introduce | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

|

| |||

| Remote counselling appointments via phone or online | 46 (64.79) | 8 (11) | |

| No ‘drop-in’ service (only testing by appointment) | 36 (50.70) | 2 (3) | |

| Self-testing (offered on-site or referred to other service—online/pharmacy) | 26 (36.62) | 5 (7) | |

| Testing campaigns | 25 (35.21) | 15 (21) | |

| Referral to other sites if testing could not be performed at your facility | 24 (33.80) | 3 (4) | |

| Triaging of patients (stricter criteria for who is being offered testing) | 21 (29.58) | 1 (1) | |

| Funding reallocations | 16 (22.54) | 6 (8) | |

| Expanded outreach testing | 14 (19.72) | 14 (20) | |

| Home sampling | 11 (15.49) | 2 (3) | |

| Staff reinforcements | 9 (12.68) | 11 (15) | |

| Equipment acquisition (purchasing of new testing platforms) | 8 (11.27) | 7 (10) | |

| Other | 3 (4.23) | 1 (1) | |

For each reported reason, respondents were asked to indicate if the impact-level was perceived as major, medium or minor. Each respondent could indicate more than one reason or new measure, hence the totals per column is higher than the number of respondents.

For each reported reason, respondents were asked to indicate if the impact-level was perceived as major, medium or minor.c. Stricter criteria for who is being offered testing.

The respondents reported a range of new measures implemented to mitigate the impact on testing (table 2). Remote appointments were overall the most frequently reported (64.8%), and several sites only tested by appointment (50.7%) or referred the users to other sites to be tested (33.8%). Several sites used testing campaigns (35.2%), with 26 (36.6%) promoting self-testing. From those promoting self-testing, 22 sites were offering HIV self-testing in some way: 17 (23.9%) distributed self-testing kits on-site; 7 (9.9%) provided self-test by referral, but the test had to be purchased elsewhere, and 5 sites (7.0%) distributed self-test kits by post.

Regarding planned measures to restore the provision of testing (if not already implemented), respondents reported performing testing campaigns (21.1%); expanding outreach testing (19.7%) and to have staff reinforcements (15.5%) (table 2).

Twenty-two sites (31.0%) reported problems in ensuring linkage to relevant health care services for people testing positive for HIV, viral hepatitis and/or STIs. The main challenges reported were delays in scheduling consultations (34.0%), difficulties in contacting the specialist care units normally referred to (27.7%), referrals only for emergency situations (23.4%) and closing of specialist care units (23.4%).

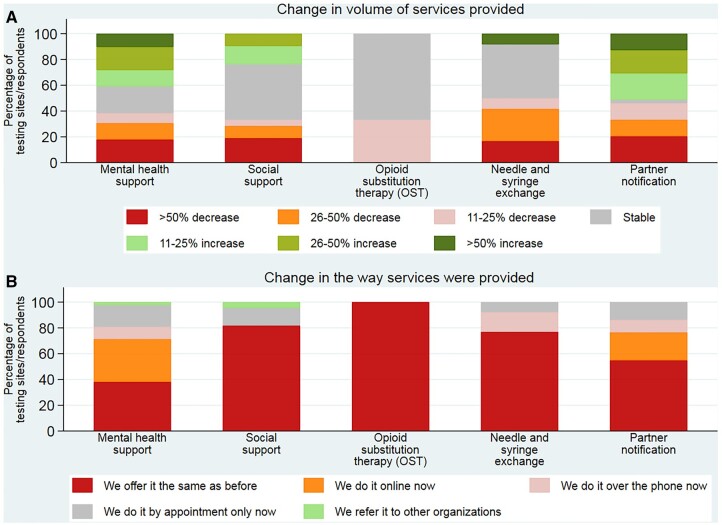

Impact on additional services provided

In 69.0% of the responding sites, clients reported increased needs and/or new needs since the onset of the pandemic. Those needs were mainly social support (56.3%); difficulty accessing health services (53.5%); mental health support (47.9%); financial support (40.9%) and to a lesser extent food insecurity (31.0%); housing support (29.6%); and transportation (16.9%).

In the period of the first wave of COVID-19, from March to May 2020, compared to the same 3 months in 2019, there were changes in the volume of other services provided apart from testing (figure 2). Around 33–50% (7/21–18/39) of sites offering some of those services reported decreases on their provision during the lockdown. In some cases, in particular for mental health and social support services, 41–51% (16/39–20/39) reported an increase. The way the services were provided during the lockdown changed for mental health (33%; 14/42) and social support (22%; 11/51), with more sites offering services online or over the phone, while in some cases these were offered just by appointment (17 and 14%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Changes in (A) the volume of services provided and (B) the way the services were provided in the period 1 March to 31 May 2020, compared with the same period in 2019 in 28 WHO European Region countries (n = 71 respondents)

Budget cuts and support needs

Around 30% of the respondents reported budget cuts due to the COVID-19 pandemic. From those, 19.0% (4/21) reported a cut of 11–25% of their annual budget; 42.9% reported a cut of 11–25%; 23.8% reported a cut of 26–50%; and 1 (4.8%) reported a cut of 50–75%.

Regarding support needs going forward, 82% (58/71) of the CBVCT services reported the need for specific guidance or support in the next waves to reduce the impact of COVID-19 on testing for HIV, viral hepatitis and STI in their settings, mainly increased financial support (72.41%); additional human resources (50%) and regulatory changes (32.76%), as allow lay-provider testing and self-testing, new protocols and regulation to allow testing continuity in CBVCT services during the pandemic and to allow COVID-19 testing in CBVCT services.

Integration of COVID-19 testing in CBVCT services

The questionnaire also included some questions regarding integration of COVID-19 testing in the CBVCT services. There were 5 sites (7.0%) that were already performing COVID-19 testing, and 23 sites (32.4%) were willing to incorporate COVID-19 testing to their services. But there are also 20 sites (28.2%) that do not want to add it to their services; 5 sites (7.0%) had not thought about it and 5 sites (7.0%) do not think it will be possible.

Discussion

This assessment shows that COVID-19 pandemic has had an important impact on community-based testing in the WHO European Region, decreasing the number of people tested for HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs from March to August 2020 across Europe compared with 2019. These findings suggest that key populations attending CBVCT services have had an increased reduction in access to testing and other essential services than before the pandemic.

This is the first European survey measuring the impact of COVID-19 in testing for HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs. The overall data from the survey has been already published,20 showing a general decrease in the volume of testing for those infections in secondary level care clinics, community sites and at national level (public health institutions or ministries of health). This study was focused on analysing in more detail the impact on community-based testing.

Other surveys have been done in CBVCT services, but not based on measuring specifically a reduction in testing. The European AIDS Treatment Group (EATG) performed a rapid assessment of COVID-19 impact on people living with HIV and on communities most affected by HIV,9 aiming to document the perceptions of people living with and affected by HIV regarding the impact of COVID-19 in their health, well-being and access to HIV related prevention, treatment and care. AIDS Foundation East-West (AFEW) international conducted a survey among civil society organisations (CSOs) in Eastern Europe and Central Asia region on how the pandemic and restrictions to stop the spread of COVID-19 have impacted CSOs and the way they are working,18 but not focusing on HIV testing activities. Both studies showed that most HIV and related testing activities from community centres were suspended, though some centres maintained some limited testing activities.

An analysis performed by the UK Health Security Agency (formerly Public Health England) in December 2020 showed that between March and May 2020 there was a reduction in consultations undertaken by health services and specialised HIV services, testing for HIV and STIs in health services, diagnoses of viral hepatitis, HIV and STIs and in HCV treatment initiations.21 Other studies have shown a decrease of STI consultations and/or diagnoses, especially for asymptomatic infections,22,23 but it is difficult to determine if these reductions are real24 or due to decreased testing during the lockdown periods.25,26

Most respondents reported testing less than half the expected number of people during the first wave of COVID-19 across Europe. The main reasons for this decrease in the volume of testing were related to the lockdown, movement and social restrictions imposed by authorities in most countries of the WHO European region,8 leading to the closure of most CBVCT services and to a reduced attendance in sites that continued operating.9,18 CBVCT services implemented several measures in order to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on testing, although these measures were more oriented to be able to offer minimum services.

Remote appointments were adopted by an important percentage of CBVCT services (almost 65%), which helped maintain contact with service users, helping them with doubts and fears, which can be calming in the context of social isolation.27 One other measure implemented by several CBVCT services, that helped maintain a minimum level of testing for HIV, was the promotion of self-testing, in line with the findings of the surveys carried out by EATG and AFEW.9,18 This complementary testing modality had not been implemented widely previously to the pandemic, despite both the fact that in most European countries there is a policy allowing HIV self-testing,28 and WHO recommendations for communities to be engaged in developing and adapting HIV self-testing models,29 and could be scaled up in the future as a complementary testing strategy in public and community-based testing services, in order to increase options for HIV testing, helping those who might be reticent or unable to seek clinic- or community-based testing.30

Despite the reopening of the CBVCT services after the first wave of COVID-19 in several countries, the testing volume did not recover the numbers of the same period of 2019. Although several measures were put in place to restore the provision of testing, again most of the measures were oriented to maintain minimum services [no ‘drop-in’ service (only testing by appointment), triaging of patients (stricter criteria for who is being offered testing)].

Another relevant issue was ensuring linkage to care to relevant health care services for those with a reactive test for HIV, viral hepatitis or STIs, reported by around 30% of respondents. Those problems were mainly due to disruptions in those specialised healthcare services, including in some cases the closure of the services.31

In most of the participating sites, the clients demanded some new or increased needs since the pandemic, including social and mental health support, and in some cases needs related with financial support, food insecurity and housing support. These data show the vulnerability of population groups attending CBVCT services, and the potential impact of the disruption of those services (other than testing) in these population groups, as well as the considerable impact that lockdown measures can have in already marginalised communities.

The budget cuts that occurred during the pandemic, affecting 30% of the participating CBVCT services could disrupt operations of those centres in the coming months and even cause closures in the future for centres with a more delicate economic situation. In the survey performed by AFEW, the loss of funding was identified as the main threat for the future of the services.18

In order to continue offering testing for HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs and reduce the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the participating CBVCT services flagged specific guidance or support from national governmental agencies as necessary, mainly human resources and financial support, as well as some regulatory changes. These included new protocols and regulations on how to operate during the pandemic to avoid the closure of the services and regulatory changes to allow self-testing and lay-provider testing. These regulatory changes had been requested prior to the pandemic by community-based services in some countries where self-testing and/or lay-provider testing was not allowed, since it is known that those testing strategies can increase testing among key populations,29 and remain an important point to improve preparedness for future health emergencies.

Implementation of COVID-19 testing in CBVCT services seems controversial. At the time of the survey, there were already some centre performing COVID-19 testing, and the rest of the participating CBVCT services were divided against and in favour. Those against the implementation of COVID-19 testing in their services were mainly worried about human and financial resources to do it and the fear of losing the focus in their work with key populations. Since this survey home/self-tests for COVID-19 became common practice for many countries in Europe, and possibly attitudes regarding this may have been changed.

This study has some limitations. Although 28 different countries were represented in the sample, in most of them only one CBVCT service participated, limiting the representativeness of the responses. Other limitation of the study is that the decrease in testing volumes were reported as broad categories of change, based on estimates rather than hard data from participating centres. The timing of the survey is also a limitation, as it was distributed at an early point of the pandemic, and since then, the results and the views of the CBVCT services could have changed. A study performed in Brighton (UK) have shown that by June 2021 testing had still not returned to normal across the city.32 A new analysis on new data collected is planned and will allow to check if testing had recovered the numbers of before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

COVID-19 pandemic has substantially impacted the testing activity on HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs in -CBVCT services in the WHO European region, indicating that key populations attending those community-based services have had a reduced access to testing.

CBVCT services had adapted their services and implemented several measures to try to minimise the impact on testing volume and regain the normal level of testing after the first lockdown. However, in most cases, the testing levels had not yet recovered in August 2020.

Self-testing for HIV and other diseases like HCV has shown further promise as an additional testing strategy and its scale up should be accelerated at national level.

To maintain testing levels and avoid an increase of incidence of HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs in key populations, it is important to ensure the operating capacity of CBVCT services in future COVID-19 epidemic waves or in other future epidemics, and thus it is important that national response planning for HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs include guidance for CBVCT services, and accelerates regulatory development to support testing in CBVCT services.

Our findings should inform future COVID 19 waves to come, especially in light of coinciding global events that promote spread of infectious diseases foremost the war in Ukraine and the displacement of millions of people this has caused.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge all the CBVCT services that responded the survey. EuroTEST COVID-19 Impact Assessment Consortium of Partners: Anastasia Pharris, ECDC, Stockholm, Sweden; Andrew Winter, International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections (IUSTI) Europe, Glasgow, UK; Ann K Sullivan, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; Ann-Isabelle von Lingen, European AIDS Treatment Group (EATG), Brussels, Belgium; Annemarie RinderStengaard, Centre of Excellence for Health, Immunity and Infections (CHIP), Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Antons Mozalevskis, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark; Cary James, World Hepatitis Alliance (WHA), London, UK; Casper Rokx, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Cristina Agustí, Centre d’Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les ITS I Sida de Catalunya (CEEISCAT) - Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain; Daria Alexeeva, AFEW International, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Dorthe Raben, Centre of Excellence for Health, Immunity and Infections (CHIP), Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Elena Vovc, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark; Erika Duffell, ECDC, Stockholm, Sweden; Giorgi Kuchukhidze, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark; Jürgen K Rockstroh, Department of Medicine I, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany; Justyna D Kowalska, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland; Kristi Rüütel, National Institute for Health Development, Tallinn, Estonia; Lara Tavoschi, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy; Lauren Combs, Centre of Excellence for Health, Immunity and Infections (CHIP), Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Magnus Unemo, WHO Collaborating Centre for STIs, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden; Maria Buti, European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), Barcelona, Spain; Michael Krone, Aids Action Europe (AAE), Berlin, Germany; Nicole Seguy, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark; Otilia Mardh, ECDC, Stockholm, Sweden; Soudeh Ehsani, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark; Teymur Noori, ECDC, Stockholm, Sweden; Valerie Delpech, Public Health England, London, UK.

Contributor Information

Laura Fernàndez-López, Health Department, Centre of Epidemiological Studies of HIV/AIDS and STI of Catalonia (CEEISCAT), Badalona, Spain; CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

Daniel Simões, Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal; Coalition PLUS, Paris, France.

Jordi Casabona, Health Department, Centre of Epidemiological Studies of HIV/AIDS and STI of Catalonia (CEEISCAT), Badalona, Spain; CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

The EuroTEST COVID-19 Impact Assessment Consortium of Partners:

Anastasia Pharris, Andrew Winter, Ann K Sullivan, Ann-Isabelle von Lingen, Annemarie RinderStengaard, Antons Mozalevskis, Cary James, Casper Rokx, Cristina Agustí, Daria Alexeeva, Dorthe Raben, Erika Duffell, Giorgi Kuchukhidze, Jürgen K Rockstroh, Justyna D Kowalska, Kristi Rüütel, Lara Tavoschi, Lauren Combs, Magnus Unemo, Maria Buti, Michael Krone, Nicole Seguy, Otilia Mardh, Soudeh Ehsani, Teymur Noori, and Valerie Delpech

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points.

COVID-19 pandemic has substantially impacted the testing activity on HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs in community-based testing services in the WHO European region.

People attending community-based voluntary, counselling and testing (CBVCT) services have experienced further reduced access to testing and other essential services than before the pandemic.

Although the adaptations of the services implemented to try to minimise the impact on testing, in most cases the testing levels were not recovered during post-confinement.

In order to ensure provision of COVID-secure testing services in future COVID-19 epidemic waves or in other future epidemics, CBVCT services need support and guidance from national governmental agencies, accompanied by regulatory changes to support testing in CBVCT services.

References

- 1. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control WHO Regional Office for Europe. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe 2020 – 2019 Data [Internet]. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2020. Available at: http://apps.who.int/bookorders (17 December 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.Monitoring the responses to hepatitis B and C epidemics in EU/EEA Member States, 2019 [Internet] .Stockholm: ECDC, 2020. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/hepatitis-B-C-monitoring-responses-hepatitis-B-C-epidemics-EU-EEA-Member-States-2019.pdf (17 December 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organisation. Progress Report on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections 2019. Accountability for the Global Health Sector Strategies, 2016–2021 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019 (WHO/CDS/HIV/19.7). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/324797/WHO-CDS-HIV-19.7-eng.pdf?ua=1 (17 December 2020, date last accessed).

- 4. Geretti AM, Mardh O, De Vries HJC, et al. Sexual transmission of infections across Europe: appraising the present, scoping the future. Sex Transm Infect 2022;98:451–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Public health guidance on HIV, hepatitis B and C testing in the EU/EEA [Internet]. 2018. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/hiv-hep-testing-guidance-web-6-december.pdf (25 May 2021, date last accessed).

- 6. Hogan AB, Jewell BL, Sherrard-Smith E, et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet] 2020;8:e1132–e1141. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32673577/ [CrossRef][10.1016/S2214- 109X(20)30288-6] [InsertedFromOnline]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. COVID-19 and HIV: 1 MOMENT 2 EPIDEMICS 3 OPPORTUNITIES [Internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2020. [cited 17 December 2020]. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20200909_Lessons-HIV-COVID19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8. ECDC. Data on country response measures to COVID-19 [Internet] [cited 18 December 2020]. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/download-data-response-measures-covid-19.

- 9. European AIDS Treatment Group. EATG Rapid Assessment. COVID-19 crisis’ impact on PLHIV and on communities most affected by HIV [Internet]. Brussels: EATG; 2020. [cited 19 January 2019]. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/EATG-Rapid-Assessment-COVID19-1-.pdf.

- 10. World Health Organization. Disruption in HIV, Hepatitis and STI services due to COVID-19 [Internet] [cited 26 October 2022]. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/hiv-hq/disruption-hiv-hepatitis-sti-services-due-to-covid19.pdf?sfvrsn=5f78b742_8.

- 11. Gatechompol S, Avihingsanon A, Putcharoen O, et al. COVID-19 and HIV infection co-pandemics and their impact: a review of the literature. AIDS Res Ther 2021;18:28–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, et al. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, Barnabas R.. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature [Internet] 2015;528:S77–S85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Croxford S, Tavoschi L, Sullivan A, et al. HIV testing strategies outside of health care settings in the European Union (EU)/European Economic Area (EEA): a systematic review to inform European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control guidance. HIV Med 2020;21:142–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV testing Monitoring implementation of the Dublin Declaration on partnership to fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia: 2018 progress report HIV testing [Internet]. Stockholm, 2019. Available at: www.ecdc.europa.eu (1 July 2020, date last accessed).

- 16. Fernàndez-López L, Reyes-Urueña J, Agustí C, et al. ; the COBATEST Network group. The COBATEST network: a platform to perform monitoring and evaluation of HIV community-based testing practices in Europe and conduct operational research. AIDS Care [Internet] 2016;28:32–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fernàndez-López L, Reyes-Urueña J, Agustí C, et al. ; The COBATEST Network Group. The COBATEST network: monitoring and evaluation of HIV community-based practices in Europe, 2014–2016. HIV Med 2018;19:21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. AFEW International. The Impact of COVID-19 on Civil Society Organisations in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Results of a Regional Survey. [Internet].Amsterdam: AFEW International, 2020. Available at: http://afew.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/COVID-impact-survey-report-AFEW-International-2.pdf (19 January 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 19. EuroTEST. Survey assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on testing for HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections in the WHO European Region [Internet]. Copenhagen: EuroTEST. Available at: http://www.eurotest.org/Projects-Collaborations/COVID-19-impact-assessment-on-testing (16 December 2020, date last accessed).

- 20. Simões D, Stengaard AR, Combs L, Raben D; TEC-19 impact assessment consortium of partners. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on testing services for HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections in the WHO European Region, March to August 2020. Eurosurveillance [Internet] 2020;25:2001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Public Health England. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prevention, testing, diagnosis and care for sexually transmitted infections, HIV and viral hepatitis in England [Internet]. 2020. [cited 29 July 2021]. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/943657/Impact_of_COVID-19_Report_2020.pdf.

- 22. Chow EPF, Hocking JS, Ong JJ, et al. Sexually transmitted infection diagnoses and access to a sexual health service before and after the national lockdown for COVID-19 in Melbourne, Australia. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet] 2021;8:ofaa536. [cited 29 July 2021]: Available at: https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/8/1/ofaa536/5952164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cusini M, Benardon S, Vidoni G, et al. Trend of main STIs during COVID-19 pandemic in Milan, Italy. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 97(2):99. [Internet] [cited 29 July 2021]; Available at: https://sti.bmj.com/content/sextrans/early/2020/08/12/sextrans-2020-054608.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hensley KS, Jordans CCE, Van Kampen JJA, et al. Significant impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care in hospitals affecting the first pillar of the HIV care continuum. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2022;74:521–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ogunbodede OT, Zablotska-Manos I, Lewis DA.. Potential and demonstrated impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexually transmissible infections: republication. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2021;16:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crane MA, Popovic A, Stolbach AI, Ghanem KG.. Reporting of sexually transmitted infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sex Transm Infect 2021;97:101–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramdas K, Ahmed F, Darzi A.. Remote shared care delivery: a virtual response to COVID-19. Lancet Digit Heal [Internet] 2020;2:e288–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.HIV self-testing research and policy hub | HIVST.org [Internet]. Available at: https://hivst.fjelltopp.org/policy (16 September 2021, date last accessed).

- 29. World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach [Internet]. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031593 (30 July 2021, date last accessed). [PubMed]

- 30. Hecht J, Sanchez T, Sullivan PS, et al. Increasing access to HIV testing through direct-to-consumer HIV self-test distribution — United States, March 31, 2020–March 30, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1322–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pinto RM, Park S.. COVID-19 pandemic disrupts HIV continuum of care and prevention: implications for research and practice concerning community-based organizations and frontline providers. AIDS Behav [Internet] 2020; 24:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wenlock RD, Shillingford C, Mear J, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on HIV testing in the UK’s first fast-track HIV city. HIV Med [Internet] 2022; 23:790–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.