Abstract

The canine distemper virus (CDV) is responsible for a multisystem infectious disease with high prevalence in dogs and wild carnivores and has vaccination as the main control measure. However, recent studies show an increase in cases including vaccinated dogs in different parts of the world. There are several reasons for vaccine failures, including differences between vaccine strains and wild-type strains. In this study, a phylogenetic analysis of CDV strains from samples of naturally infected, vaccinated, and symptomatic dogs in Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil was performed with partial sequencing of the hemagglutinin (H) gene of CDV. Different sites of amino acid substitutions were found, and one strain had the Y549H mutation, typically present in samples from wild animals. Substitutions in epitopes (residues 367, 376, 379, 381, 386, and 388) that may interfere with the vaccine’s ability to provide adequate protection against infection for CDV were observed. The identified strains were grouped in the South America 1/Europe lineage, with a significant difference from other lineages and vaccine strains. Twelve subgenotypes were characterized, considering a nucleotide identity of at least 98% among the strains. These findings highlight the relevance of canine distemper infection and support the need better monitoring of the circulating strains that contribute to elucidate if there is a need for vaccine update.

Keywords: Viral strain, CDV, Genotyping, Lineages, Nested-PCR

Introduction

Canine distemper virus (CDV) is the etiologic agent of one of the most relevant infectious diseases for domestic dogs and wild carnivores worldwide [1–3]. The CDV genome is composed of a negative single-strand RNA, which encodes for six structural proteins. Of these proteins, hemagglutinin (H) binds the virus to host cell receptors, such as the signaling molecule in lymphocyte activation (SLAM/CD150) and nectin-4. Protein H is associated with the tropism of the virus for different hosts. Its genetic variations can result in modification of virulence, the ability of the virus to infect a greater variety of hosts, and in the evasion of the host’s immune response [4–6].

Phylogenetic and evolutionary analyses of CDV have shown amino acid substitutions along the H gene, mainly at positions 530 and 549 [5]. These positions are found within the binding region of the H gene to the signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM) receptor, and modifications are associated with the emergence of the virus in a non-canid host [5, 7, 8]. Due to its high variability, the H gene is the most suitable for molecular investigations regarding viral polymorphism and it is used as a target for the identification and characterization of CDV [4, 8–12]. There are 17 lineages/genotype according to geographic distribution: North America 1–5 (NA 1–5), South America 1/Europe (SA1/EU), South America 2–4 (SA 2–4), European Wildlife (EU–W), Arctic-like (AL), Rockborn-like (RL), Africa 1 and 2 (AF 1 and 2), and Asia 1–4 (A 1–4) [9, 12–22].

Classic CDV strain vaccines are usually derived from the North America 1 and belong to this genotype, except for the Rockborn vaccine [23, 24]. Although immunization of domestic dogs through vaccination has been intensified in recent years, vaccine failures have been reported worldwide, suggesting the circulation of vaccine-resistant strains [8, 12, 19, 24–26].

Given the clinical importance of distemper for domestic dogs and wild animals, studies that identify and determine the lineage of circulating strains and how mutations in the H gene are directly related to possible vaccine failures, are needed. This study aimed to characterize the strains of CDV circulating among naturally infected domestic dogs and to conduct a comparative phylogenetic analysis between these wild strains and the vaccine strains.

Materials and methods

Animals

This study was approved by the Committee on Ethics and Use of Animals (CEUA – Protocols no. 065/16 and no. 106/18) of the Federal University of Goiás (UFG, Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil). Samples were collected from six dogs positive for distemper with progressive neurological signs at the Veterinary Hospital, School of Veterinary and Animal Science (UFG, Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil).

RNA extraction and complementary DNA synthesis

RNA was extracted from urine and blood samples using Trizol LS Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol with adaptations according to Frisk et al. [27]. After extraction, reverse transcription (RT) reaction was performed by adding 20 μL of the extracted RNA to 30 μL of a reaction mixture containing 1 × of 5 × buffer, 0.002 μg/μL random primers (Invitrogen), 0.4 mM of each dNTP, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5 µL DTT (0.1 M), 20 U/μL RNAsin (Invitrogen), 200 U/μL M-MLV RT (Invitrogen), and DEPC water. The microtubes were transferred to an automatic thermocycler (Swift TM Maxi, Esco) under the following conditions: 40 min at 37 °C, followed by 10 min at 95 °C.

RT-PCR of N and H genes

Primer pairs used for amplification of partial regions of the N and H genes were synthesized as described in previous studies [10, 27, 28]. The NPp1 and NPp2 primers targeting the N gene were used to screen all samples for CDV by RT-PCR with one round of amplification [27]. For the phylogenetic analysis, amplification of the partial region of the H gene was performed. The first amplification was performed with the primer pairs H2F_CDV and H3R_CDV [28] and, in nested PCR, the primers CDVF10 and CDVR10_ND were used [10]. The sequences of the primers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in polymerase chain reaction assays for amplification of canine distemper virus N and H gene fragments

| Primer | Oligonucleotide sequencea | Target | Genomic position | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPp1 | ACA GGA TTG CTG AGG ACC TAT | Gene N | 769–789 | Frisk et al. [27] |

| NPp2 | CAA GAT AAC CAT GTA CGG TGC | Gene N | 1055–1035 | Frisk et al. [27] |

| H2F_CDV | AAT ATG CTR ACY GCT ATC TC | Gene H | 7730–7749 | An et al. [28] |

| H3R_CDV | TCA RGG TTT KGA ACG RTT AC | Gene H | 8883–8902 | An et al. [28] |

| CDVF10 | TAT CAT GAC RGY ART GGT TC | Gene H | 7991–8010 | Hashimoto et al. [10] |

| CDVR10_ND | GGA CTA AAT YYT CRA YAC TGG | Gene H | 8842–8861 | Hashimoto et al. [10] |

aSequences are displayed in the sense 5ʹ–3ʹ

For the CDV screening, the expected fragment size was 287 bp. The RT-PCR was performed according to Frisk et al. [27] with modifications. Briefly, 3 μL of each complementary DNA (cDNA) sample was mixed with 22 μL of a reaction mix composed of 1 × GoTaq mastermix (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), 0.4 μM NPp1, 0.4 μM NPp2, and nuclease-free water for the final volume of 25 μL. The microtubes were placed in the thermocycler T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) under the following conditions: 5 min at 94 °C followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 2 min at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72ºC, finishing with 5 min at 72 °C.

For the detection of the H gene, amplification was performed using RT-PCR to obtain the 1172-bp fragment. Subsequently, nested PCR was performed to obtain a fragment of 870 bp, according to Fischer et al. [11]. The PCR was performed using 5.0 μL of cDNA sample mixed with 20.0 μL of a mixture consisting of 1 × GoTaq mastermix, 0.4 μM H2F, 0.4 µM of H3R, and nuclease-free water for the final volume of 25.0 µL. The microtubes were placed in the thermocycler under the following conditions: 5 min at 94 °C followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, ending with 5 min at 72 °C.

Nested PCR was performed with a final volume of 25.0 μL, with 1.0 μL of the DNA template obtained in the previous PCR and 24.0 μL of the reaction mixture consisting of 1 × GoTaq Master Mix, 0.8 μM of the CDVF10 and CDVR10 primer, and nuclease-free water for the final volume of 25.0 μL. Using the same thermocycler, the conditions were 3 min at 94 °C followed by 30 cycles of 20 s at 94 °C, 40 s at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, ending with 5 min at 72 °C. Nested PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis running on a 1.5% agarose gel (Invitrogen, Foster City, USA) in Tris–borate–EDTA buffer with ethidium bromide (0.1%). Subsequently, the amplified fragments were visualized in an ultraviolet light transilluminator (MS Major Science, CA, USA).

Nucleotide sequencing

The products generated by nested PCR were purified using the ExoSAP-ITTM PCR Product Cleanup reagent (Applied Biosystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and quantified in Nanodrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples with adequate concentration and purity were submitted to sequencing using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in the AB 3500 Genetic Analyzer automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), to read the electropherograms, with the generation of approximately 700 nucleotides each, by ACTGene Análises Moleculares Ltda (Center for Biotechnology, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil).

For phylogenetic characterization, H gene sequences of the CDV strains available in the NCBI Nucleotide Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were selected. All deposited sequences of strains identified in Brazil and specimens belonging to existing strains, including vaccine strains, were compiled. All sequences selected had complete information regarding the year, country of origin, and the host species from which they were isolated. In total, 65 sequences were used to represent the 17 lineages, including the vaccine strains: Snyder Hill (accession number: AF259552), Rockborn-Candur (accession number: GU266280), Onderstepoort (accession number: AF378705), and Lederle (accession number: DQ903854).

A database was set up with the H gene sequences of all CDV strains identified in Brazil and deposited at the NCBI to compose the phylogenetic analysis to obtain subgenotypes in the SA1/EU linage.

For the identification of subgenotypes belonging to the SA1/EU lineage, the strains utilized in this study and strains previously described as belonging to this lineage were used as a database H gene sequence of the CDV, as proposed by Budaszewski et al. [24]. Sequences that did not correspond to the same region of the H gene as the sequences identified in this study were excluded. In total, 49 sequences were used to represent the subgenotypes. Sequences belonging to the same subgenotype show nucleotide identity of at least 98%.

Phylogenetic analysis of the H gene

The electropherograms obtained in the sequencing were analyzed to verify the quality of the bases obtained and had their consensus sequence determined using the results of sense and antisense sequences at the Phred/Phrap interface [29, 30] through the website http://asparagin.cenargen.embrapa.br/phph/ of EMBRAPA (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation). Nucleotide identity was verified with the sequences deposited in GenBank using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

The alignment of the consensus sequences of each sample together with the selected sequences was performed using the ClustalW program implemented in the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis X (MEGA-X) software, version 10.2.20 [31], and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method. The most suitable model for nucleotide substitution was identified by MEGA-X as T92 + G: Tamura parameter-3 with gamma distribution rate heterogeneity, with five rate categories. The robustness of the phylogenetic analysis was evaluated by bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates. The North America 1 strain and vaccine strains were used as the outgroup for rooting the phylogenetic tree. The consensus nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were deposited in the NCBI GenBank under accession numbers MZ758890–MZ758897.

Results

Detection of CDV and sequence analysis of the H gene

Information about the dogs included in the phylogenetic analysis (identification, sex, age, clinical signs, and vaccination status) and the accession number referring to the positive sample for partial amplification of the H gene are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of dogs and samples from naturally infected dogs in the municipality of Goiânia in 2017, 2019, and 2020

| Dog ID | Sex | Age | Clinical signs | Vaccination status | Type of sample | Year of sample collection | Accession number of H gene sequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | F | 6 m | GSI, RS, NS | No | 01B | 2017 | MZ758890 |

| 02 | M | 4y | RS, NS | No | 02B | 2019 | MZ758891 |

| 03 | F | 7y | RS, DS, NS | No | 03B | 2019 | MZ758892 |

| 04 | F | 5 m | RS, DS, NS | Yes | 04B | 2019 | MZ758893 |

| 04 | F | 5 m | RS, DS, NS | Yes | 04U | 2019 | MZ758894 |

| 05 | M | 5y | RS, NS | No | 05U | 2019 | MZ758895 |

| 06 | M | 5y | RS, DS, NS | O | 06B | 2020 | MZ758896 |

| 06 | M | 5y | RS, DS, NS | O | 06U | 2020 | MZ758897 |

S blood, U urine, M male, F female, y years, m months, RS respiratory signs, NS neurological signs, DS dermatological signs, GSI gastrointestinal signs, O outdated, vaccinated as a puppy

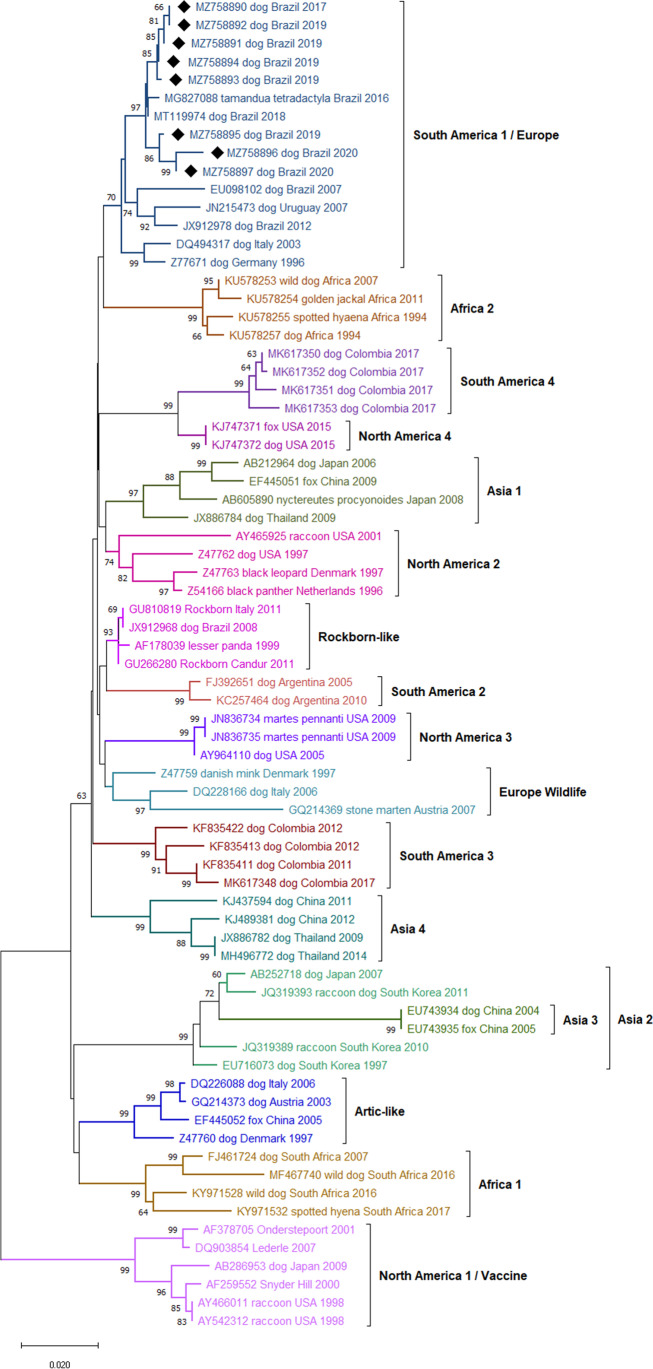

In the phylogenetic tree, all partial nucleotide sequences of the CDV strains identified in this study were grouped with the South America 1/Europe (SA1/EU) genotype (Fig. 1). Data from the distance analysis of paired comparisons between genotypes are presented in Table 3. The paired comparisons showed that the nucleotide divergence between the identified strains and the other variants belonging to the SA1/EU genotype was estimated between 0.14 and 3.89%, showing, therefore, high nucleotide identity. High identity was detected among the Brazilian strains, with values greater than 97.8%. Comparisons between 06U and 06S strains (99.34% nucleotide identity) and between 04S and 04U strains (99.87% nucleotide identity) showed high identity between strains isolated from the same dog.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree containing 73 strains of canine distemper virus (CDV) according to the H gene sequence, inferred by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method using 1000 replicates. The GenBank accession number, the host species from which each isolate was obtained, the country of origin, and the year of isolation are indicated. The numbers indicated in the nodes are bootstrap values > 60 for the genotypes. The samples identified in this study were marked with a black diamond (♦)

Table 3.

Identity matrix analysis between canine distemper virus genotypes’ nucleotide sequences

| SA1/EU | A1 | A2 | NA1/Vac | RL | NA2 | NA3 | AL | EU-W | A3 | SA2 | AF1 | A4 | SA3 | NA4 | AF2 | SA4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA1/EU | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | |

| A1 | 0.050 | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.011 | |

| A2 | 0.074 | 0.085 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.013 | |

| NA1/Vac | 0.094 | 0.111 | 0.113 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 | |

| RL | 0.028 | 0.040 | 0.055 | 0.083 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.009 | |

| NA2 | 0.045 | 0.056 | 0.079 | 0.102 | 0.033 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.009 | |

| NA3 | 0.049 | 0.061 | 0.072 | 0.105 | 0.034 | 0.054 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.011 | |

| AL | 0.053 | 0.066 | 0.069 | 0.101 | 0.043 | 0.062 | 0.067 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.011 | |

| EU-W | 0.051 | 0.063 | 0.075 | 0.105 | 0.034 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.063 | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.010 | |

| A3 | 0.112 | 0.123 | 0.060 | 0.162 | 0.101 | 0.124 | 0.120 | 0.111 | 0.120 | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.017 | |

| SA2 | 0.049 | 0.062 | 0.081 | 0.101 | 0.030 | 0.055 | 0.054 | 0.064 | 0.056 | 0.128 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.011 | |

| AF1 | 0.066 | 0.075 | 0.082 | 0.105 | 0.052 | 0.074 | 0.079 | 0.065 | 0.074 | 0.124 | 0.072 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.011 | |

| A4 | 0.055 | 0.062 | 0.084 | 0.108 | 0.039 | 0.063 | 0.058 | 0.071 | 0.062 | 0.128 | 0.062 | 0.080 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.011 | |

| SA3 | 0.050 | 0.059 | 0.082 | 0.099 | 0.037 | 0.060 | 0.056 | 0.065 | 0.060 | 0.127 | 0.058 | 0.070 | 0.063 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.010 | |

| SA4 | 0.049 | 0.061 | 0.078 | 0.110 | 0.033 | 0.054 | 0.051 | 0.064 | 0.054 | 0.123 | 0.058 | 0.070 | 0.062 | 0.057 | 0.010 | 0.006 | |

| AF2 | 0.052 | 0.071 | 0.088 | 0.113 | 0.039 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.073 | 0.062 | 0.132 | 0.060 | 0.080 | 0.070 | 0.064 | 0.061 | 0.011 | |

| SA4 | 0.063 | 0.079 | 0.098 | 0.119 | 0.054 | 0.069 | 0.077 | 0.086 | 0.075 | 0.139 | 0.076 | 0.090 | 0.080 | 0.075 | 0.031 | 0.083 |

Identity matrix analysis with 73 sequences nucleotide of the H gene of canine distemper virus. The values of the pairwise comparison between the genotypes are presented in italics, standard error estimates are shown above the diagonal in bold, and the variance estimation method was the bootstrap with 1000 replicates. Analyses were conducted using the 3-parameter Tamura nucleotide substitution model and the rate of change was modeled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter = 1). All positions that contained gaps and missing data were removed for each sequence pair. The final dataset consisted of 763 positions. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA-X version 10.2.2 (https://www.megasoftware.net/)

SA1/EU – South America 1/Europe; NA2 – North America 2; AL – Arctic-like; EU-W – Europe Wildlife; SA4 – South America 4; SA3 – South America 3; A4 – Asia 4; AF1 – Africa 1; AF2 – Africa 2; NA4 – North America 4; SA2 – South America 2; RL – Rockborn-like; A1 – Asia 1; A2 – Asia 2; NA3 – North America 3; A3 – Asia 3; NA1/Vac – North America 1/Vaccine

There was an approximately 10% nucleotide divergence between the SA1/EU lineage and the NA1/Vac lineage, which includes most strains in commercial vaccines (Table 3). In the evaluation of the values of paired comparisons between the sequences of the vaccine strains with those isolated in the study, the following data were observed: maximum nucleotide identities of 91.6% with the Lederle, 91.3% with the Onderstepoort, and 90.87% with the Snyder Hill. Some commercial vaccines use in their formulation strains like Rockborn-Candur, grouped in the RL, which maximum nucleotide identity was 97.68% with the isolated strains.

The distance of nucleotide with isolates from countries neighboring Brazil, such as Argentina, Colombia, and Uruguay, showed approximate nucleotide variations of 4.89%, 4.99%, and 6.27% between SA1/EU with SA2, SA3, and SA4, respectively (Table 3). Compared to previous studies in Brazil, the nucleotide identity with the strains MT119974 (accession number), isolated from a dog (Canis lupus familiaris), and MG827088 (accession number), isolated from small anteater (Tamandua tetradactyla), was 98.1% and 99.7%, respectively.

Amino acid analysis of the H protein

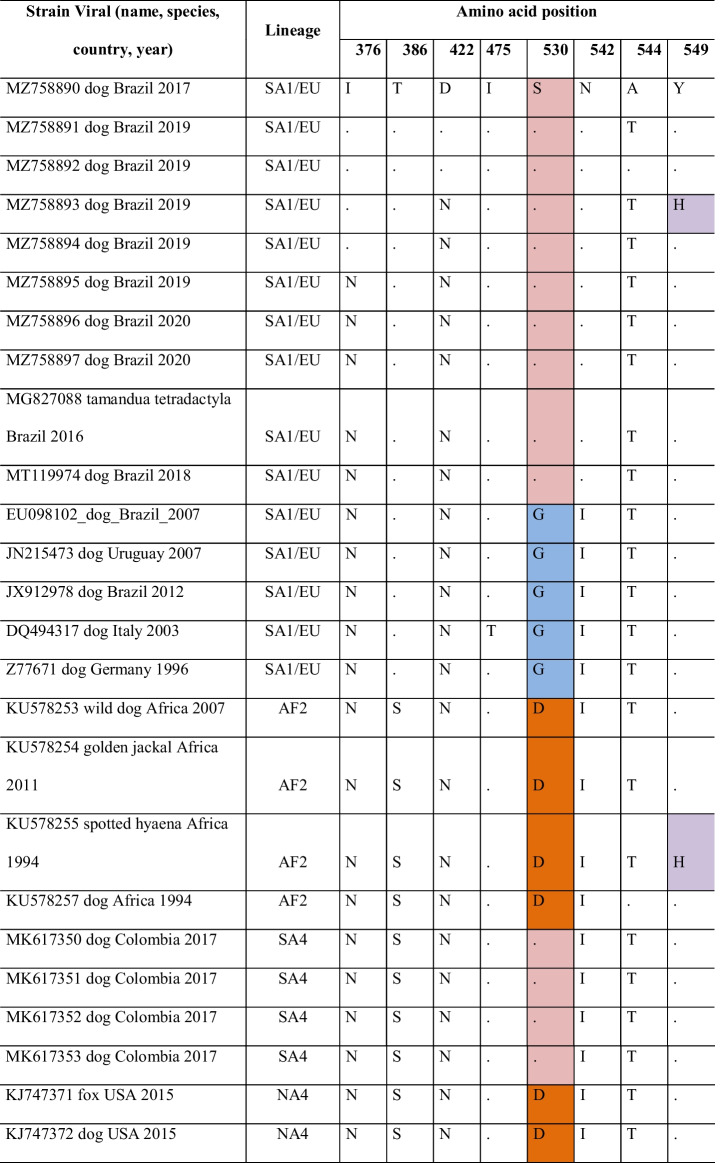

Partial amino acid sequences of the H gene from 73 CDV strains were aligned and analyzed to identify potential occurrences of mutations associated with amino acid changes (Table 4). The complete H gene sequencing of strain EU098102 (accession number) was used as a reference for identifying amino acid positions.

Table 4.

Analysis of the amino acid sequence alignment of gene H of canine distemper virus (CDV)

This analysis involved 73 CDV strains and the dataset consisted of 607 amino acid positions. Positions associated with positive selection among strains were selected. The amino acids at positions 530 and 549 are in the SLAM receptor-binding regions of the host cells; therefore, identical residues received the same staining on identification. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA-X version 10.2.2 (https://www.megasoftware.net/)

SA1/EU – South America 1/Europe; NA2 – North America 2; AL – Arctic-like; EU-W – Europe Wildlife; SA4 – South America 4; SA3 – South America 3; A4 – Asia 4; AF1 – Africa 1; AF2 – Africa 2; NA4 – North America 4; SA2 – South America 2; RL – Rockborn-like; A1 – Asia 1; A2 – Asia 2; NA3 – North America 3; A3 – Asia 3; NA1/Vac – North America 1/Vaccine

Most of the sequences from dogs presented 530S (13/46) and 530D (12/46). The 530S was more commonly identified in dogs of the SA1 and SA4 genotypes, while the 530D had a greater distribution (AF2, NA4, RL, SA2, NA3, EU-W, and A4 genotypes). Among the non-dog hosts were found residues 530D (9/24), 530N (6/24), G (4/24), E (2/24), and R (2/24). In the vaccine strains, residues 530N (Snyder Hill) and 530S (Onderstepoort and Lederle) were identified.

The most common amino acid found at position 549 was Y (59/70), more frequent in dogs (43/70). The substitution for amino acid H (Y549H) was identified in dog (3/11) and non-dog (8/11) sequences. In the vaccine’s strains, 549Y was identified in one (Snyder Hill) and 549H in two (Onderstepoort and Lederle). In this study, we identified one sequenced with the Y549H substitution (12S [GenBank MZ758893]).

Regarding the other positions evaluated, the T386 amino acid residue was identified only in the SA1/EU and SA2 genotypes, while in the other genotypes, the substitution for S386 was found. In position 376, amino acids N, I, S, T, and D were found, and the study strains had I376 (01S [GenBank MZ758890], 6S [GenBank MZ758891], 11S [GenBank MZ758892], 12S [GenBank MZ758893], and 12U [GenBank MZ758894]) and N376 (13U [GenBank MZ758895], 28S [GenBank MZ758896], and 28U [GenBank MZ758897]). There was no association with the host in the substitutions found at positions 376, 422, 475, 542, and 544.

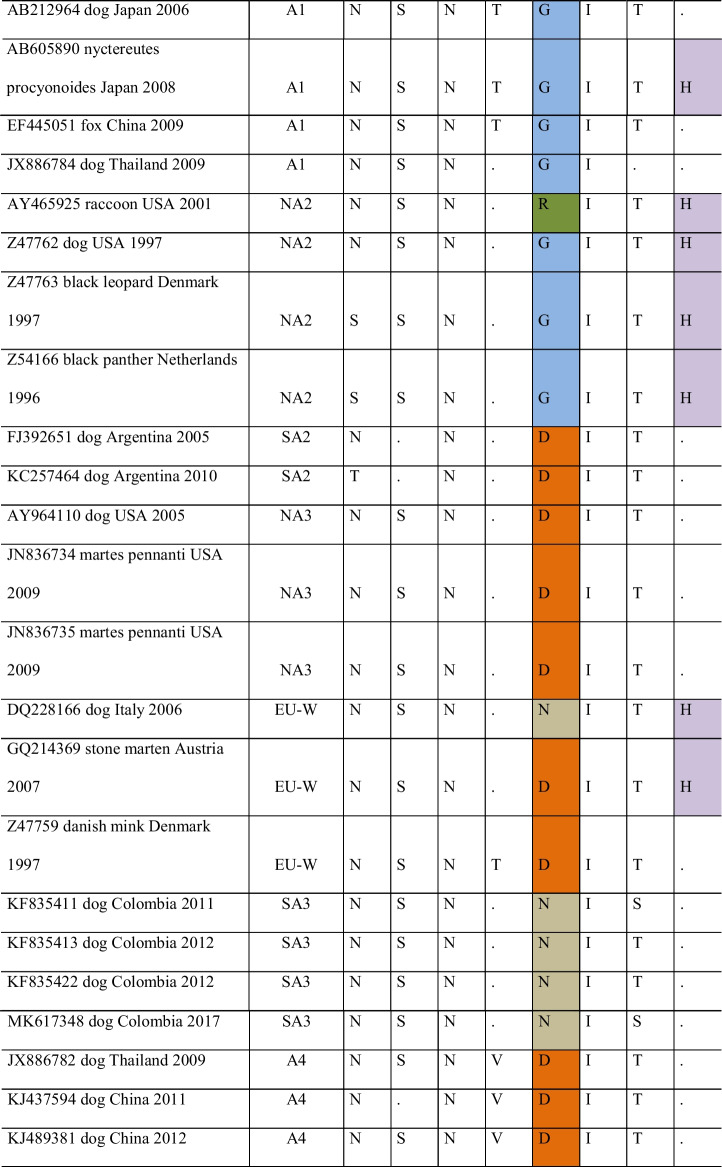

The amino acids at positions 367 and 376 were similar between the NA1 genotypes and the Lederle, Onderstepoort, and Snyder Hill vaccine strains but different from the other genotypes. The Rockborn-Candur strain was more similar to the American genotypes when compared to other vaccine strains (Table 5). The most found residue at position 367 was valine (V), unlike vaccine strains, whose identified residue was alanine (A), except in the Rockborn-Candur (V367). At position 376, the residue most frequent was N, except for the NA1 and vaccines Lederle, Onderstepoort, and Snyder Hill (G376), whereas 01S (GenBank MZ758890), 6S (GenBank MZ758891), 11S (GenBank MZ758892), 12S (GenBank MZ758893), and 12U (GenBank MZ758894) had isoleucine (I) in 376. Substitutions were noted in residues D379 (28S [GenBank MZ758896]) and V381 (28S [GenBank MZ758896] and 28U [GenBank MZ758897]). The identity at the amino acid level between the strains identified in the study and the vaccines Lederle, Onderstepoort, and Snyder Hill was between 87 and 91%, while with Rockborn-Candur, amino acid identity ranged between 95.5% and 97.2%.

Table 5.

Analysis of the alignment of partial amino acid sequences of gene H of strains of American and vaccine genotypes

| Viral strain (name, species, country, year) | Lineage | Amino acid position | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 367 | 376 | 379 | 381 | 386 | 388 | ||

| V | I | E | A | T | P | ||

| AF259552-Snyder Hill 2000 | Vac | A | G | . | . | . | . |

| AF378705 Onderstepoort 2001 | Vac | A | G | . | . | . | . |

| DQ903854 Lederle 2007 | Vac | A | G | . | . | . | . |

| GU266280 Rockborn-Candur 2011 | Vac | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| AY466011 raccoon USA 1998 | NA1 | A | G | . | . | . | . |

| AY542312 raccoon USA 1998 | NA1 | A | G | . | . | . | . |

| AB286953 dog Japan 2009 | NA1 | A | G | . | . | . | . |

| MZ758890 dog Brazil 2017 | SA1 | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MZ758891 dog Brazil 2019 | SA1 | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MZ758892 dog Brazil 2019 | SA1 | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MZ758893 dog Brazil 2019 | SA1 | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MZ758894 dog Brazil 2019 | SA1 | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MZ758895 dog Brazil 2019 | SA1 | . | N | . | . | . | . |

| MZ758896 dog Brazil 2020 | SA1 | . | N | D | V | . | H |

| MZ758897 dog Brazil 2020 | SA1 | . | N | . | V | . | . |

| MG827088 Tamandua tetradactyla Brazil 2016 | SA1 | . | N | . | . | . | . |

| MT119974 dog Brazil 2018 | SA1 | . | N | . | . | . | . |

| EU098102_dog_Brazil_2007 | SA1 | A | N | . | . | . | . |

| JN215473 dog Uruguay 2007 | SA1 | . | N | . | . | . | . |

| JX912978 dog Brazil 2012 | SA1 | . | N | . | . | . | . |

| MK617350 dog Colombia 2017 | SA4 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| MK617351 dog Colombia 2017 | SA4 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| MK617352 dog Colombia 2017 | SA4 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| MK617353 dog Colombia 2017 | SA4 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| KJ747371 fox USA 2015 | NA4 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| KJ747372 dog USA 2015 | NA4 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| AY465925 raccoon USA 2001 | NA2 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| Z47762 dog USA 1997 | NA2 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| Z47763 black leopard Denmark 1997 | NA2 | . | S | . | . | S | . |

| Z54166 black panther Netherlands 1996 | NA2 | . | S | . | . | S | . |

| FJ392651 dog Argentina 2005 | SA2 | . | N | . | . | . | . |

| KC257464 dog Argentina 2010 | SA2 | . | T | . | . | . | . |

| AY964110 dog USA 2005 | NA3 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| JN836734 Martes pennanti USA 2009 | NA3 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| JN836735 Martes pennanti USA 2009 | NA3 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| KF835411 dog Colombia 2011 | SA3 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| KF835413 dog Colombia 2012 | SA3 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| KF835422 dog Colombia 2012 | SA3 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

| MK617348 dog Colombia 2017 | SA3 | . | N | . | . | S | . |

Identical residues are shown with a (.). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA-X version 10.2.2 (https://www.megasoftware.net/)

SA1 – South America 1; NA2 – North America 2; SA4 – South America 4; SA3 – South America 3; NA4 – North America 4; SA2 – South America 2; NA3 – North America 3; NA1 – North America 1; Vac – Vaccine

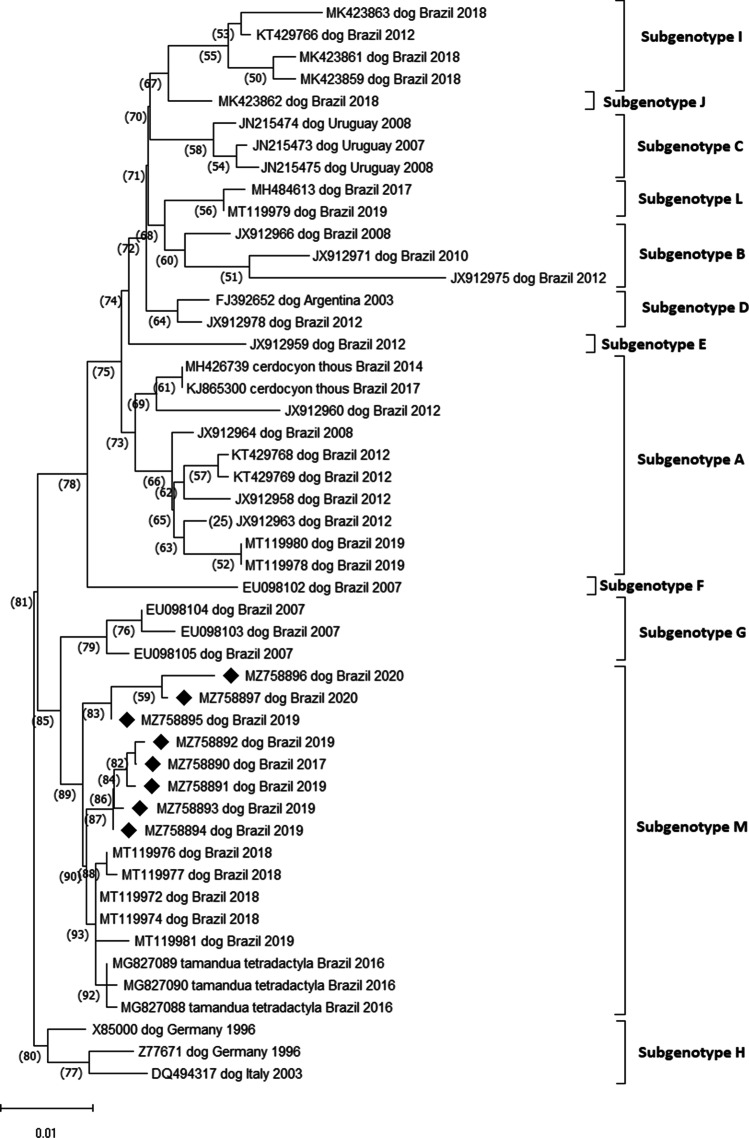

South America 1/Europe subgenotypes

Twelve subgenotypes were identified within the SA1/EU lineage, and within each subgenotype, the nucleotide identity between the strains was greater than 98% (Fig. 2). The sequences 13U, 28S, and 28U (GenBank MZ758895, MZ758896, and MZ758897, respectively) were grouped into different subgenotypes from the sequences: 01S, 6S, 11S, 12S, and 12U (GenBank MZ758890, MZ758891, MZ758892, MZ758893, and MZ758894, respectively) and had nucleotide variation of 2.03–2.17%.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of canine distemper virus (CDV) according to partial sequences of gene H with details of subgenotypes (subgenotypes A–M) of the South America 1/Europe genotype, inferred by the neighbor-joining method (NJ) using 1000 replicates and 3-parameter Tamura nucleotide substitution model. The GenBank accession number, the host species from which each isolate was obtained, the country of origin, and the year of isolation are indicated. The numbers indicated in the nodes are bootstrap values > 60 for the subgenotypes. The strains identified in this study were marked with a black diamond (♦)

The other strains belonging to the SA1/EU genotype selected to compose the phylogenetic analysis for South America were from Uruguay and Argentina. Uruguay strains grouped into a specific subgenotype distinct from the other Brazilian ones (subgenotype B), while the Argentina strain showed nucleotide identity greater than 98% with other Brazilian ones (subgenotype C). Regarding the strains belonging to Europe, three strains were selected, which showed distinction from the other strains and nucleotide divergence between 2.0% and 4.18% with the others.

Discussion

In the present study, eight CDV sequences belonging to the SA1/EU genotype were identified, and through identity matrix analysis, a high variability was observed among the Brazilian strains and the genotype of the vaccines currently in use in Brazil. Multiple substitutions at amino acids 530 and 549, as well as at other positions, were evidenced. The SA1/EU genotype was evaluated separately, and the phylogenetic analysis suggests that there are at least 12 subgenotypes.

The identity matrix of the partial nucleotide sequences of the H gene with the eight identified sequences in our study and the ones retrieved from NCBI showed that Brazilian strains and strains of the SA1/EU genotype have a difference of less than 4% [25, 32]. The highest nucleotide identities were found with the strains MT119974 (99.73%) and MG827088 (99.47%), both identified in the state of Mato Grosso which border the state of Goiás. In addition to the geographic distance, the presence of such genetically similar strains may be related to commercial and tourist relations between the two regions [33, 34]. The other genotypes identified in South America presented nucleotide differences close to 5%, with values of 4.89%, 4.99%, and 6.27% with the genotypes SA2 [17], SA3 [19], and SA4 [12], respectively.

CDV infection was confirmed in a 5-month-old, vaccinated dog and in a 5-year-old dog with overdue vaccine. The phylogenetic analysis and the identity matrix rule out the possibility of a disease caused by the vaccine strain with residual virulence since the strains identified in these dogs (12S [GenBank MZ758893] and 12U [GenBank MZ758894] – puppy dog and 28S [GenBank MZ758896] and 28U [GenBank MZ758897] – adult dog) showed nucleotide differences between 8.3% and 10.3% with the vaccine strains Lederle, Onderstepoort, and Snyder Hill. Vaccine failures may be associated with failure in the primary immune response due to vaccination of immunocompromised dogs and inadequate vaccination. In puppies, maternal antibodies can also contribute to specific immune response failure [35].

The binding regions of the H gene to the nectin-4 and SLAM receptors correspond to amino acid residues 454 to 555 [36]. A series of substitutions at different positions along the partial sequence of the H gene in this study were recognized according to previous studies [5, 8, 11, 19, 36]. The population sampled was composed only of domestic dogs and one strain 12S (GenBank MZ758893) was identified with residue 549H. Although the Y549H substitution is expected in strains adapted to non-canid species [37] and Y549 to be found in domestic dogs [8, 19], polymorphisms with the substitution of the Y residue for the H has been reported in dogs [7, 11]. Studies have shown the exposure of wild species to CDV [38–41], suggesting a continuous transmission of strains circulating between wild canids and other carnivores to domestic dogs and vice versa [11].

Substitutions at residues 530 (G/E to R/D/N) may be related to the emergence of CDV strains capable of infecting non-canid species [5, 37]. In this study, at position 530, no modifications associated with the host species were identified, as observed in previous studies [7, 19] and unlike what was observed by Benetka et al. [37], who identified changes in residues G or E associated with interspecies transmission. The S residue was found in strains of genotypes SA1/EU and SA4 predominantly in dogs [19].

The amino acid residue or region that constitute antigenic determinants of the vaccine strains were conducted as the data related to the main immunodominant epitopes in Morbillivirus [42]. In morbilliviruses [43], the main sites of antigenic neutralization may be located between amino acid residues 364 and 392 of the CDV protein H [42, 44]. The substitutions of at least six amino acids (367, 376, 379, 381, 386, and 388) were found between wild-type and vaccine strains in the Americas. Also, at positions 376 (01S, 6S, 11S, 12S, and 12U [GenBank MZ758890 to MZ758894) and 381 (28S and 28U [GenBank MZ758896 and MZ758897]), different amino acids were found between the sequences of this study, the vaccines, and the other sequences analyzed, suggesting a possible polymorphism. Although these polymorphisms could suggest a vaccine escape, they alone cannot be sufficient for confirmation. According to Anis et al. [45], these substitutions may interfere with the ability of the vaccine to provide adequate protection against infection with these strains. Similar results on the heterogeneity of wild strains and vaccine strains, in domestic dogs and wild animals, have been previously published [22, 36, 46, 47].

In this study, we identified 12 subgenotypes (subgenotypes A–M) while in previous studies eight subgenotypes (A–H) were identified in the SA1/EU genotype [24]. The inclusion of numerous variants analyzed in the present study may have contributed to the identification of four more subgenotypes in the SA1/EU genotype.

Conclusion

Eight wild-type strains were detected among the samples obtained from animals in the Mid-West of Brazil. Although they are distinct strains, the nucleotide difference is less than 4% and, therefore, they belong to the same genotype, SA1/EU. One strain has the substitution at the amino acid Y549H, an evident polymorphism associated with interspecies contact, which may also be associated with the possibility of the emergence of more pathogenic strains.

Many nucleotide mutations and amino acid substitutions were found when wild strains were compared to vaccine strains, which could contribute with the occurrence of vaccine failures. Thus, the characterization of the H gene in samples from different populations of animal species will allow better monitoring of the circulating strains e contribute to elucidate if there is a need for vaccine update.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Graduate Support Program (Programa de Apoio à Pós-Graduação, Brazil; PROAP) and the Coordination Office for Improvement of Higher-Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, CAPES; Brazil) for their assistance in acquiring materials to carry out the research and for granting the researcher a scholarship.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Responsible Editor: Fernando R. Spilki

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Greene CE (2012) Canine distemper. In: Greene CE (ed) Infectious diseases of the dog and cat, 4th edn. Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis, pp 25–41

- 2.Beineke A, Baumgärtner W, Wohlsein P. Cross-species transmission of canine distemper virus-an update. One Health. 2015;1:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Gutierrez M, Ruiz-Saenz J. Diversity of susceptible hosts in canine distemper virus infection: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0702-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Messling V, Zimmer G, Herrler G, Haas L, Cattaneo R. The hemagglutinin of canine distemper virus determines tropism and cytopathogenicity. J Virol Published online. 2001 doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6418-6427.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarthy AJ, Shaw MA, Goodman SJ. Pathogen evolution and disease emergence in carnivores. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274(1629):3165–3174. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ke GM, Ho CH, Chiang MJ, et al. Phylodynamic analysis of the canine distemper virus hemagglutinin gene. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0491-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikolin VM, Wibbelt G, Michler FUF, Wolf P, East ML. Susceptibility of carnivore hosts to strains of canine distemper virus from distinct genetic lineages. Vet Microbiol. 2012;156(1–2):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bi Z, Wang Y, Wang X, Xia X. Phylogenetic analysis of canine distemper virus in domestic dogs in Nanjing. China Arch Virol. 2015;160(2):523–527. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2293-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas L, Martens W, Greiser-Wilke I, et al. Analysis of the haemagglutinin gene of current wild-type canine distemper virus isolates from Germany. Virus Res. 1997;48(2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(97)01449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashimoto M, Une Y, Mochizuki M. Hemagglutinin genotype profiles of canine distemper virus from domestic dogs in Japan. Arch Virol. 2001;146(1):149–155. doi: 10.1007/s007050170198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer CDB, Gräf T, Ikuta N, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of canine distemper virus in South America clade 1 reveals unique molecular signatures of the local epidemic. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;41:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duque-Valencia J, Forero-Muñoz NR, Díaz FJ, Martins E, Barato P, Ruiz-Saenz J. Phylogenetic evidence of the intercontinental circulation of a canine distemper virus lineage in the Americas. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15747. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52345-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blixenkrone-Möller M, Svansson V, Appel M, Krogsrud J, Have P, Örvell C. Antigenic relationships between field isolates of morbilliviruses from different carnivores. Arch Virol. 1992;123(3):279–294. doi: 10.1007/BF01317264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harder TC, Kenter M, Vos H, et al. Canine distemper virus from diseased large felids: biological properties and phylogenetic relationships. J Gen Virol. 1996;77(3):397–405. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-3-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwatsuki K, Tokiyoshi S, Hirayama N, et al. Antigenic differences in the H proteins of canine distemper viruses. Vet Microbiol. 2000;71(3–4):281–286. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao JJ, Yan XJ, Chai XL, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of the haemagglutinin gene of canine distemper virus strains detected from breeding foxes, raccoon dogs and minks in China. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(1–2):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panzera Y, Calderon MG, Sarute N, et al. Evidence of two co-circulating genetic lineages of canine distemper virus in South America. Virus Res. 2012;163(1):401–404. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radtanakatikanon A, Keawcharoen J, Charoenvisal TN, et al. Genotypic lineages and restriction fragment length polymorphism of canine distemper virus isolates in Thailand. Vet Microbiol. 2013;166(1–2):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espinal MA, Díaz FJ, Ruiz-Saenz J. Phylogenetic evidence of a new canine distemper virus lineage among domestic dogs in Colombia. South America Vet Microbiol. 2014;172(1–2):168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riley MC, Wilkes RP. Sequencing of emerging canine distemper virus strain reveals new distinct genetic lineage in the United States associated with disease in wildlife and domestic canine populations. Virol J. 2015;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0445-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolin VM, Olarte-Castillo XA, Osterrieder N, et al. Canine distemper virus in the Serengeti ecosystem: molecular adaptation to different carnivore species. Mol Ecol. 2017;26(7):2111–2130. doi: 10.1111/mec.13902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anis E, Holford AL, Galyon GD, Wilkes RP. Antigenic analysis of genetic variants of canine distemper virus. Vet Microbiol. 2018;219:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martella V, Blixenkrone-Møller M, Elia G, et al. Lights and shades on an historical vaccine canine distemper virus, the Rockborn strain. Vaccine. 2011;29(6):1222–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budaszewski R da F, Pinto LD, Weber MN et al (2014) Genotyping of canine distemper virus strains circulating in Brazil from 2008 to 2012. Virus Res 180:76–83. 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Martella V, Cirone F, Elia G, et al. Heterogeneity within the hemagglutinin genes of canine distemper virus (CDV) strains detected in Italy. Vet Microbiol Published online. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demeter Z, Lakatos B, Palade EA, Kozma T, Forgách P, Rusvai M. Genetic diversity of Hungarian canine distemper virus strains. Vet Microbiol. 2007;122(3–4):258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisk AL, König M, Moritz A, Baumgärtner W. Detection of canine distemper virus nucleoprotein RNA by reverse transcription-PCR using serum, whole blood, and cerebrospinal fluid from dogs with distemper. J Clin Microbiol: Published online; 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.An DJ, Yoon SH, Park JY, No IS, Park BK. Phylogenetic characterization of canine distemper virus isolates from naturally infected dogs and a marten in Korea. Vet Microbiol Published online. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I Accuracy Assess Genome Res. 1998;8(3):175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon D, Desmarais C, Green P. Automated finishing with autofinish. Genome Res. 2001;11(4):614–625. doi: 10.1101/gr.171401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mochizuki M, Hashimoto M, Hagiwara S, Yoshida Y, Ishiguro S. Genotypes of canine distemper virus determined by analysis of the hemagglutinin genes of recent isolates from dogs in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(9):2936–2942. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.9.2936-2942.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panzera Y, Sarute N, Iraola G, Hernandez M, Perez R. Molecular phylogeography of canine distemper virus: geographic origin and global spreading. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;92:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cortez A, Heinemann MB, Junior AAF, da Costa LF, de Souza VAF, Megid J. Genetic characterization of the haemagglutinin gene in canine distemper virus strains from naturally infected dogs in Brazil Caracterização genética do gene da hemaglutinina em vírus da cinomose caninca de cães naturalmente infectados no Brasil. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci. 2017;54(4):445–449. doi: 10.11606/issn.1678-4456.bjvras.2017.133315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Day MJ, Horzinek MC, Schultz RD, Squires RA. WSAVA guidelines for the vaccination of dogs and cats. J Small Anim Pract. 2016;57(1):E1. doi: 10.1111/jsap.2_12431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bae CW, Lee JB, Park SY, et al. Deduced sequences of the membrane fusion and attachment proteins of canine distemper viruses isolated from dogs and wild animals in Korea. Virus Genes. 2013;47(1):56–65. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0916-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benetka V, Leschnik M, Affenzeller N, Möstl K. Phylogenetic analysis of Austrian canine distemper virus strains from clinical samples from dogs and wild carnivores. Veterinary Record. 2011;168(14):377. doi: 10.1136/vr.c6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nava AFD, Cullen L, Jr, Sana DA, et al. First evidence of canine distemper in Brazilian free-ranging felids. EcoHealth. 2008;5(4):513–518. doi: 10.1007/s10393-008-0207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Megid J, de Souza VAF, Teixeira CR, et al. Canine distemper virus in a crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) in Brazil: case report and phylogenetic analyses. J Wildl Dis. 2009;45(2):527–530. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-45.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Hübner OS, Pappen FG, Ruas JL, Vargas GD, Fischer G, Vidor T. Exposure of pampas fox (Pseudalopex gymnocercus) and crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) from the Southern region of Brazil to canine distemper virus (CDV), canine parvovirus (CPV) and canine coronavirus (CCoV) Brazilian Arch Biol Technol. 2010;53(3):593–597. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132010000300012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furtado MM, Hayashi EMK, Allendorf SD, et al. Exposure of free-ranging wild carnivores and domestic dogs to canine distemper virus and parvovirus in the Cerrado of Central Brazil. EcoHealth. 2016;13(3):549–557. doi: 10.1007/s10393-016-1146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugiyama M, Ito N, Minamoto N, Tanaka S. Identification of immunodominant neutralizing epitopes on the hemagglutinin protein of rinderpest virus. J Virol. 2002;76(4):1691–1696. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1691-1696.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Messling V, Oezguen N, Zheng Q, Vongpunsawad S, Braun W, Cattaneo R. Nearby clusters of hemagglutinin residues sustain SLAM-dependent canine distemper virus entry in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Virol. 2005;79(9):5857–5862. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5857-5862.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liebert UG, Flanagan SG, Löffler S, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Rima BK. Antigenic determinants of measles virus hemagglutinin associated with neurovirulence. J Virol. 1994;68(3):1486–1493. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1486-1493.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anis E, Newell TK, Dyer N, Wilkes RP. Phylogenetic analysis of the wild-type strains of canine distemper virus circulating in the United States. Virol J. 2018;15(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12985-018-1027-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pardo IDR, Johnson GC, Kleiboeker SB. Phylogenetic characterization of canine distemper viruses detected in naturally infected dogs in North America. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(10):5009–5017. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5009-5017.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gámiz C, Martella V, Ulloa R, Fajardo R, Quijano-Hernandéz I, Martínez S. Identification of a new genotype of canine distemper virus circulating in America. Vet Res Commun. 2011;35(6):381–390. doi: 10.1007/s11259-011-9486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]