Highlights

-

•

Co-morbid CVD/CRF is associated with higher COVID-19 severity among patients with cancer, particularly those not receiving active cancer therapy.

-

•

This increased risk suggests that patients with cancer and co-morbid CVD/CVRF should be considered for early antiviral and immunomodulator therapy.

-

•

Further studies are needed to assess strategies to improve COVID-19 related outcomes in patients with comorbid cancer and CVD/CRF.

Keywords: COVID-19 outcomes, Cardio-oncology, Cardiovascular disease, Cancer

Abstract

Background

Data regarding outcomes among patients with cancer and co-morbid cardiovascular disease (CVD)/cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) after SARS-CoV-2 infection are limited.

Objectives

To compare Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) related complications among cancer patients with and without co-morbid CVD/CVRF.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of patients with cancer and laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2, reported to the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) registry from 03/17/2020 to 12/31/2021. CVD/CVRF was defined as established CVD or no established CVD, male ≥ 55 or female ≥ 60 years, and one additional CVRF. The primary endpoint was an ordinal COVID-19 severity outcome including need for hospitalization, supplemental oxygen, intensive care unit (ICU), mechanical ventilation, ICU or mechanical ventilation plus vasopressors, and death. Secondary endpoints included incident adverse CV events. Ordinal logistic regression models estimated associations of CVD/CVRF with COVID-19 severity. Effect modification by recent cancer therapy was evaluated.

Results

Among 10,876 SARS-CoV-2 infected patients with cancer (median age 65 [IQR 54–74] years, 53% female, 52% White), 6253 patients (57%) had co-morbid CVD/CVRF. Co-morbid CVD/CVRF was associated with higher COVID-19 severity (adjusted OR: 1.25 [95% CI 1.11–1.40]). Adverse CV events were significantly higher in patients with CVD/CVRF (all p<0.001). CVD/CVRF was associated with worse COVID-19 severity in patients who had not received recent cancer therapy, but not in those undergoing active cancer therapy (OR 1.51 [95% CI 1.31–1.74] vs. OR 1.04 [95% CI 0.90–1.20], pinteraction <0.001).

Conclusions

Co-morbid CVD/CVRF is associated with higher COVID-19 severity among patients with cancer, particularly those not receiving active cancer therapy. While infrequent, COVID-19 related CV complications were higher in patients with comorbid CVD/CVRF. (COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium Registry [CCC19]; NCT04354701).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AC

anticoagulation

- APT

antiplatelet therapy

- AZT

azithromycin

- CCC19

COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- CVRF

cardiovascular risk factors

- HCQ

hydroxychloroquine

- HLD

hyperlipidemia

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2

Introduction

Early experiences in China demonstrated that there was a higher incidence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and adverse outcomes among the elderly, patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) (including hypertension [HTN] and diabetes mellitus [DM]) [1,2], and cancer [3]. Subsequent meta-analyses have confirmed that these conditions are independently associated with disease severity and mortality among patients with COVID-19 [4,5]. However, the impact of co-morbid CVD/CVRF and cancer on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outcomes and CV complications remains unclear.

Large retrospective studies in North America have identified malignancy as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease [6,7]. A meta-analysis of 52 studies, involving 18,650 patients with cancer and COVID-19, estimated a 25.6% mortality in this population [8]. However, small studies examining whether the presence of comorbid CVD worsens outcomes among patients with cancer have had conflicting results [5,6,9]. Some have suggested that recent cancer directed therapy, rather than co-morbid CVD, predicts COVID-19 outcomes among patients with cancer [9]. Therefore, we used the collaborative, large, multi-institutional COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) registry to investigate the association between CVD/CVRF and morbidity and mortality among patients with cancer infected with SARS-CoV-2. We also evaluated this association in patients who had received cancer therapy within 3 months of COVID-19 diagnosis.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a registry-based retrospective cohort study of patients reported to the CCC19 registry between 03/17/2020 and 12/31/2021. The multi-institutional CCC19 registry was created to help bridge the knowledge gap in cancer care caused by the COVID-19 pandemic [10]. Participating sites report data on cases of laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection or presumptive COVID-19 from patients (age ≥ 18 years) with a current or prior history of cancer. Detailed information regarding registry data accrual can be found in the previously published protocol [11]. Data are collected in four primary domains: [1] de-identified demographic and other baseline data, including medical comorbidities that are not related to cancer or COVID-19; [2] clinical data pertaining to COVID-19, including laboratory values, severity of presentation, and treatments received for COVID-19; [3] data pertaining to cancer diagnosis, stage, and current and prior treatment; and [4] follow-up data including outcomes related to COVID-19.

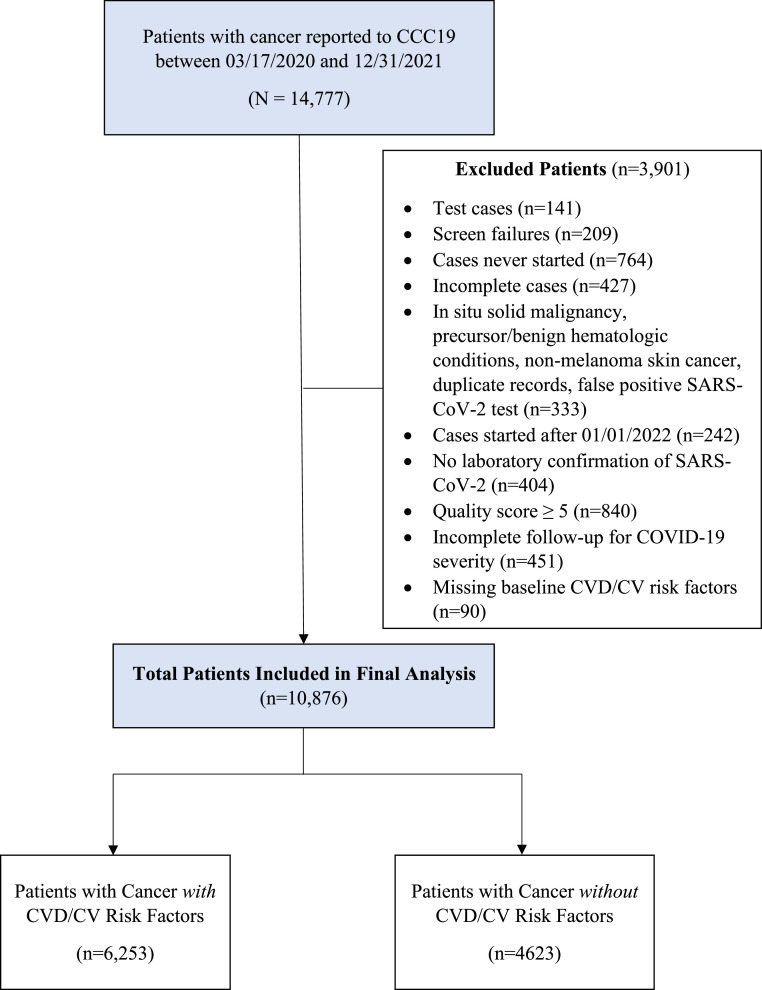

This analysis excluded patients with non-invasive cancers including non-melanoma skin cancer, in situ carcinoma (except bladder carcinoma in situ), or precursor hematologic neoplasms (e.g., monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance). Patients with poor quality data (data quality score ≥ 5) [11] and those with inadequate follow-up within CCC19 to assess the outcomes of interest were also excluded. Because we were interested in assessing the association of pre-existing CVD/CVRF with COVID-19 related outcomes, patients with unknown CVD/CVRF due to missing data were also excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow Diagram. This diagram depicts details of the patients that were included and excluded in this analysis.

CV = cardiovascular, CVD = cardiovascular disease, CVRF = cardiovascular risk factors.

This study was exempt from human research committee review (VUMC IRB 200467) and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04354701).

CVD/CV risk factors

Baseline CVD was defined as the presence of established CVD [coronary artery disease (CAD), peripheral arterial disease (PAD), cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or heart failure (HF)]. Heart failure included both heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. The presence of baseline CVRF was defined as no established CVD and male ≥ 55 years or female ≥ 60 years with one additional risk factor (HTN, DM, hyperlipidemia [HLD], or current tobacco use).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was an ordinal scale of COVID-19 severity: ambulatory, hospitalized without supplemental oxygen, hospitalized with supplemental oxygen, need for intensive care unit (ICU), need for mechanical ventilation, ICU or mechanical ventilation with inotropes/vasopressors, and death.

Secondary outcomes included individual components of the ordinal outcome. Additional secondary outcomes included incident adverse CV events including myocardial infarction (MI), atrial fibrillation (AF), ventricular fibrillation (VF), cardiomyopathy or reduced ejection fraction, symptomatic heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction (HF), cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as counts (%) and continuous variables as median (interquartile range [IQR], respectively. Standard descriptive statistics compared baseline characteristics, anti-COVID-19 treatments, and outcomes between patients with and without pre-existing CVD/CVRF. Ordinal logistic regression models with an offset for (log) follow-up time were used to determine whether pre-existing CVD/CVRF were associated with COVID-19 severity. The model was adjusted for relevant baseline risk factors including age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), cancer type (solid or hematologic), cancer stage (localized or disseminated), cancer status (remission, active responding, active stable or active progressing), different types of active cancer directed therapies (within 3 months of COVID-19 diagnosis), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, period of COVID-19 diagnosis, US census geographical region, and baseline CV medications [12]. Age exhibited a non-linear association and was adjusted for by using a linear spline with a knot at age 40 years. Variables were assessed for collinearity before inclusion in multivariable models. To better understand the interaction between CVD/CVRF and active cancer therapy on COVID-19 severity, we performed a stratified analysis in patients with and without any recent cancer therapy (within 3 months of COVID-19 diagnosis). A secondary analysis was conducted to estimate adjusted associations of individual CV co-morbidities/CVRF with COVID-19 severity. We also compared the incidence of adverse CV events in patients with and without CVD/CVRF using Fisher's exact test. Multiple imputation (20 iterations, missingness rates <20%) using additive regression, bootstrapping, and predictive mean matching was used to impute missing and unknown data for all variables included in the analysis; unknown ECOG status and unknown cancer status were included as ‘unknown’ categories. Results were combined using Rubin's rules and are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All tests were two-sided and a 95% CI that did not cross 1.0 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.2, including the Hmisc and rms extension packages.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

A total of 14,777 adult patients with cancer and SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported to CCC19 between 03/17/2020 and 12/31/2021. The majority of patients reported to the registry originated from the US Northeast and US Midwest. Among the 10,876 patients who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 6253 (57%) had pre-defined co-morbid CVD/CVRF and 4623 (43%) did not (Fig. 1). Patients with cancer and CVD/CVRF were older (median age 71 years vs. 53 years) and predominantly male (55% vs. 36%) compared to patients without CVD/CVRF (Table 1). Majority of patients in both groups were White (56% vs. 47%), with more non-Hispanic Black patients (20% vs. 14%) and fewer Hispanic patients (12% vs. 25%) among those with CVD/CVRF. In both groups, the majority of patients had solid tumors that were localized and in remission. Approximately half of the patients in both groups had not received active cancer directed therapy within 3 months of COVID-19 diagnosis (59% with CVD/CVRF vs. 48% without CVD/CVRF). A smaller proportion of patients with cancer and CVD/CVRF were receiving cytotoxic therapy (16% vs. 26%) and targeted therapy (13% vs. 18%) at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis compared to those without CVD/CVRF.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of COVID-19 patients with cancer stratified by the presence of comorbid CVD/CV risk factors.

| Characteristics | With CVD/CV risk factors | Without CVD/CV risk factors |

|---|---|---|

| N = 6253 | N = 4623 | |

| Demographics | ||

| Age, years [Median (IQR)] | 71 (64–79) | 53 (44–60) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 2815 (45) | 2953 (64) |

| Male | 3435 (55) | 1667 (36) |

| Missing/Unknown | 3 (0) | 3 (0) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3513 (56) | 2181 (47) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1273 (20) | 650 (14) |

| Hispanic | 725 (12) | 1169 (25) |

| Other | 630 (10) | 547 (12) |

| Missing/Unknown | 112 (2%) | 76 (2) |

| BMI, kg/m2 [Median (IQR)] | 28.2 (24.7–32.9) | 28.0 (24.0–33.0) |

| Missing/Unknown | 1437 (23%) | 1000 (22%) |

| Cancer History | ||

| ECOG performance status prior to infection, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 1535 (25) | 1889 (41) |

| 1 | 1678 (27) | 1221 (26) |

| 2+ | 1123 (18) | 408 (9) |

| Unknown/Missing | 1917 (31) | 1105 (24) |

| Tumor Type, n (%) | ||

| Solid | 5171 (83) | 3656 (79) |

| Heme | 1340 (21) | 1081 (23) |

| Cancer Stage, n (%) | ||

| Disseminated | 1725 (28) | 1470 (32) |

| Localized | 3373 (54) | 2441 (53) |

| Missing/Unknown | 1155 (18) | 712 (15) |

| Cancer Status, n (%) | ||

| Remission/NED | 3043 (49) | 2049 (44) |

| Active, responding | 666 (11) | 656 (14) |

| Active, stable | 1093 (17) | 729 (16) |

| Active, progressing | 816 (13) | 708 (15) |

| Unknown/Missing | 635 (10%) | 481 (10) |

| Active Cancer Therapy, n (%) | ||

| None within 3 months of COVID-19 | 3673 (59) | 2229 (48) |

| Cytotoxic Therapy | 1005 (16) | 1197 (26) |

| Targeted Therapy | 793 (13) | 816 (18) |

| Endocrine Therapy | 614 (10) | 515 (11) |

| Immunotherapy | 333 (5) | 236 (5) |

| Local | 557 (9) | 450 (10) |

| Other | 95 (2) | 81 (2) |

| Missing/Unknown | 107 (2) | 60 (1) |

| Cardiac History | ||

| Cardiovascular Comorbidity, n (%) | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 1242 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 290 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 538 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Congestive heart failure | 783 (13) | 0 (0) |

| CV Risk Factors, n (%) | ||

| Smoker | ||

| Current | 455 (7) | 204 (4) |

| Former | 2818 (45) | 1283 (28) |

| Never | 2773 (44) | 3004 (65) |

| Missing/Unknown | 207 (3) | 132 (3) |

| Hypertension | 5061 (81) | 890 (19) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2840 (45) | 376 (8) |

| Diabetes | 2386 (38) | 505 (11) |

| >= 2 CV risk factors | 6004 (96) | 479 (10) |

| Men ≥ 55 years old | 3373 (54) | 701 (15) |

| Women ≥ 60 years old | 2686 (43) | 653 (14) |

| Baseline Cardiac Medications, n (%) | ||

| ACE-I | 1375 (22) | 310 (7) |

| ARB | 1202 (19) | 220 (5) |

| Beta-blocker | 1797 (29) | 297 (6) |

| Statin | 3340 (53) | 506 (11) |

| AC, ASA or APT | 3352 (54) | 876 (19) |

| COVID-19 Diagnosis | ||

| Region, n (%) | ||

| US Northeast | 2132 (34) | 1344 (29) |

| US Midwest | 1908 (31) | 1094 (24) |

| US South | 939 (15) | 733 (16) |

| US West | 878 (14) | 933 (20) |

| Undesignated US | 57 (1) | 40 (1) |

| Non-US | 339 (5) | 479 (10) |

| Date of COVID-19 Diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| January–April 2020 | 694 (11) | 334 (7) |

| May–August 2020 | 2009 (32) | 1527 (33) |

| September–December 2020 | 2351 (38) | 1978 (43) |

| January–April 2021 | 405 (6) | 302 (7) |

| May–August 2021 | 362 (6) | 229 (5) |

| September–December 2021 | 424 (7) | 251 (5) |

| Missing/Unknown | 6 (0) | 1 (0) |

| COVID-19 Treatment, n (%) | ||

| HCQ only | 441 (7) | 140 (3) |

| AZT only | 577 (10) | 289 (7) |

| HCQ and AZT | 433 (7) | 199 (5) |

| Remdesivir | 1009 (17) | 446 (10) |

| Steroids | 1671 (28) | 827 (19) |

| Tocilizumab | 217 (4) | 72 (2) |

| Other | 591 (10) | 317 (7) |

ACE-I = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, AC = anticoagulation, ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker, APT = antiplatelet therapy, ASA = aspirin, AZT = azithromycin, BB = beta blocker, BMI = body mass index, CV = cardiovascular, CVD = cardiovascular disease, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, HCQ = hydroxychloroquine.

Among all patients with cancer, the prevalence of baseline CVD was as follows: 20% CAD, 13% HF, 9% CVA, and 5% PVD (Table 1). HTN was the most prevalent CVRF (55%), followed by HLD (30%), DM (27%), and current tobacco use (6%) (Table 1). Baseline use of cardiac medications, including angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), beta-blockers (BB), statins, anticoagulation (AC) and/or antiplatelet therapy (APT), was more frequent in patients with cancer and CVD/CVRF than in those without CVD/CVRF (Table 1).

CVD/CV risk factors and COVID-19 outcomes among SARS-CoV-2-Infected patients with cancer

Rates of hospitalization and need for supplemental oxygen, ICU care, mechanical ventilation, and vasopressors were higher among patients with cancer and CVD/CVRF compared to those without CVD/CVRF (Table 2), over a median follow-up of 90 (IQR: 30–180) days. Patients with cancer and CVD/CVRF died more frequently (23% vs. 11%) than those patients without CVD/CVRF.

Table 2.

Individual components of the primary ordinal outcome.

| Outcome |

Patients with CVD/CVRF (N = 6253) |

Patients without CVD/CVRF (N = 4623) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (%) | N | n (%) | |

| Hospitalization | 6253 | 4035 (65) | 4623 | 1852 (40) |

| No supplemental O2 | 6175 | 1080 (17) | 4548 | 712 (16) |

| Supplemental O2 | 6175 | 2928 (47) | 4548 | 1124 (25) |

| ICU admission | 6189 | 1191 (19) | 4602 | 470 (10) |

| Need for mechanical ventilation | 6207 | 734 (12) | 4608 | 293 (6) |

| ICU admission, mechanical ventilation and vasopressors* | 763 | 330 (43) | 449 | 133 (30) |

| Death | 6252 | 1413 (23) | 4623 | 527 (11) |

Abbreviations: CVD = cardiovascular disease, CVRF = cardiovascular risk factors, ICU = intensive care unit.

Missing data for vasopressors.

CVD/CV risk factors and COVID-19 severity among SARS-CoV-2-Infected patients with cancer

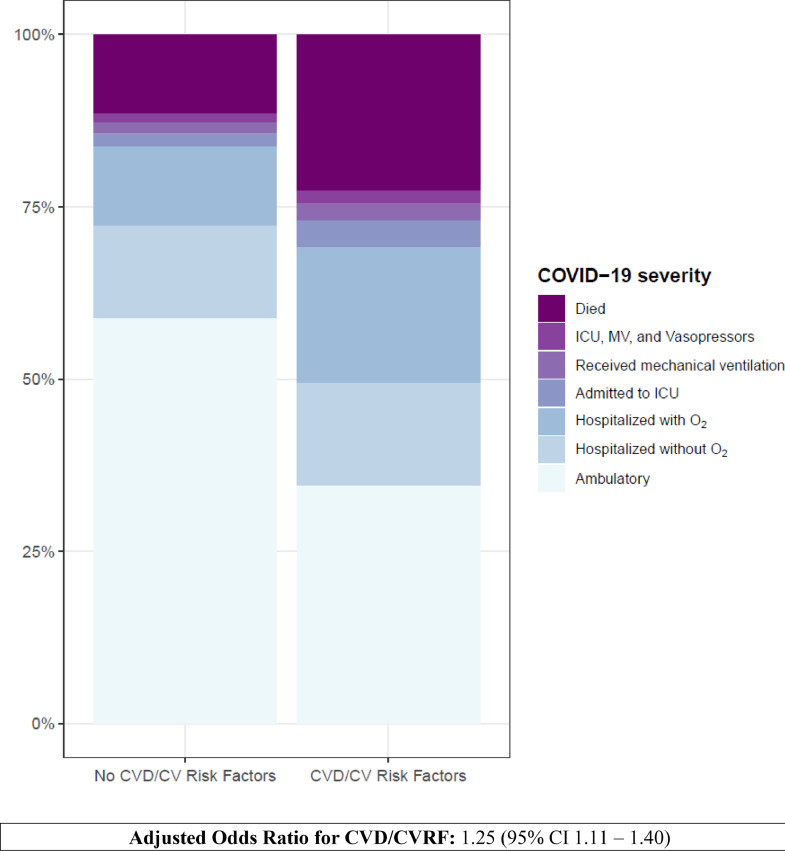

Patients with cancer and CVD/CVRF had significantly higher COVID-19 severity compared to patients without CVD/CVRF (unadjusted OR 3.15 [95% CI: 2.91–3.41] (Table 3) (Fig. 2). This association remained statistically significant after multivariable adjustment (adjusted OR: 1.25 [95% CI: 1.11–1.40] (Table 3). In addition to co-morbid CVD/CRF, age > 40 years, male sex, non-White race, extremes of BMI (< 18.5 and ≥ 35 kg/m2), ECOG score ≥ 1, disseminated cancer, active and progressing cancer, cytotoxic and locoregional cancer therapy, and baseline use of beta-blockers and AC/APT were also associated with higher COVID-19 severity in adjusted analyses (Table 3). Individually, established CVD, HTN, DM, and current or former tobacco use, but not HLD, were associated with higher COVID-19 severity among patients with cancer (Table 4). Among the various forms of established CVD, HF was associated with the highest risk of severe COVID-19 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Predictors of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer.

|

COVID-19 Disease Severity |

||

|---|---|---|

| Predictors | OR | 95% CI |

| Unadjusted | ||

| CV Risk Factors (yes vs. no) | 3.15 | 2.91–3.41 |

| Adjusted | ||

| CV Risk Factors (yes vs. no) | 1.25 | 1.11–1.40 |

| Age | ||

| < 40 years, per decade | 0.89 | 0.75–1.04 |

| > 40 years, per decade | 1.42 | 1.42–1.56 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | Ref. | |

| Male | 1.42 | 1.31–1.54 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref. | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.26 | 1.13–1.41 |

| Hispanic | 1.30 | 1.15–1.47 |

| Other | 1.27 | 1.10–1.46 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| 18–24 | Ref. | |

| < 18.5 | 1.66 | 1.26–2.18 |

| 25–29.9 | 0.77 | 0.69–0.87 |

| 30–34.9 | 0.89 | 0.78–1.01 |

| 35–39.9 | 1.22 | 1.04–1.44 |

| >40 | 1.47 | 1.23–1.77 |

| ECOG Score | ||

| 0 | Ref. | |

| 1 | 1.46 | 1.31–1.63 |

| 2+ | 6.33 | 5.50–7.28 |

| Unknown | 1.66 | 1.49–1.85 |

| Tumor Type | ||

| Multiple | Ref. | |

| Heme | 1.10 | 0.87–1.39 |

| Solid | 0.66 | 0.53–0.82 |

| Cancer Stage | ||

| Localized | Ref | |

| Disseminated | 1.56 | 1.39–1.75 |

| Cancer Status | ||

| Remission/NED | Ref. | |

| Active and responding | 1.01 | 0.87–1.17 |

| Active and stable | 1.02 | 0.89–1.16 |

| Active and progressing | 4.01 | 3.46–4.65 |

| Unknown | 1.46 | 1.25–1.71 |

| Recent cancer therapy (vs. none) | 1.09 | 0.97–1.21 |

| Cancer Therapy (yes vs. no) | ||

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy | 1.30 | 1.15–1.46 |

| Targeted therapy | 0.99 | 0.87–1.13 |

| Immunotherapy | 1.03 | 0.85–1.40 |

| Endocrine therapy | 0.70 | 0.61–0.81 |

| Locoregional therapy | 1.25 | 1.08–1.44 |

| Baseline Cardiac Medications (yes vs. no) | ||

| ACE-I | 0.85 | 0.76–0.95 |

| ARB | 0.87 | 0.77–0.98 |

| BB | 1.24 | 1.11–1.38 |

| Statins | 1.07 | 0.97–1.17 |

| AC, ASA or APT | 1.46 | 1.33–1.60 |

| Region of COVID-19 Diagnosis US Northeast |

||

| Ref. | ||

| Non-US | 0.67 | 0.56–0.80 |

| US Midwest | 0.77 | 0.69–0.86 |

| US South | 0.80 | 0.71–0.91 |

| US West | 0.65 | 0.57–0.74 |

| Date of COVID-19 Diagnosis January–April 2020 |

||

| Ref. | ||

| May–August 2020 | 0.38 | 0.34–0.43 |

| September–December 2020 | 0.23 | 0.21–0.26 |

| January–April 2021 | 0.39 | 0.33–0.45 |

| May–August 2021 | 0.33 | 0.27–0.39 |

| September–December 2021 | 0.71 | 0.56–0.90 |

ACE-I = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, AC = anticoagulation, ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker, APT = antiplatelet therapy, ASA = aspirin, BB = beta blocker, BMI = body mass index, CV = cardiovascular, CVD = cardiovascular disease, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Fig. 2.

Risk of the Primary Ordinal Outcome was Significantly Increased in Patients with Cancer and Comorbid Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)/Cardiovascular Risk Factors. The primary outcome was an ordinal scale of progressive COVID-19 related adverse events starting with ambulatory, hospitalized, hospitalized with supplemental oxygen, need for intensive care unit (ICU), need for mechanical ventilation (MV), ICU or MV with inotropes/vasopressors, and death. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown.

Table 4.

Association of individual baseline CVD/CVRF with COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer.

|

Minimally adjusteda |

Fully adjustedb |

Mutually adjustedc |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| CAD | 1.61 | 1.42–1.82 | 1.35 | 1.18–1.54 | 1.22 | 1.06–1.39 | ||

| PVD | 2.27 | 1.77–2.90 | 1.62 | 1.27–2.07 | 1.40 | 1.09–1.80 | ||

| CVA | 2.15 | 1.79–2.57 | 1.59 | 1.32–1.91 | 1.50 | 1.24–1.81 | ||

| CHF | 2.47 | 2.13–2.86 | 1.86 | 1.59–2.17 | 1.63 | 1.39–1.91 | ||

| HTN | 1.42 | 1.31–1.55 | 1.39 | 1.26–1.53 | 1.36 | 1.23–1.50 | ||

| DM | 1.74 | 1.59–1.89 | 1.60 | 1.45–1.75 | 1.52 | 1.38–1.67 | ||

| HLD | 0.73 | 0.67–0.79 | 0.79 | 0.71–0.87 | 0.74 | 0.67–0.82 | ||

| Current Smoker | 1.34 | 1.13–1.58 | 1.26 | 1.05–1.50 | 1.20 | 1.00–1.43 | ||

| Former Smoker | 1.42 | 1.30–1.54 | 1.35 | 1.23–1.47 | 1.29 | 1.18–1.41 | ||

Minimally adjusted models include age, sex, and one risk factor.

Fully adjusted models include all covariates (age, sex, race, smoking, BMI, ECOG status, tumor type, cancer stage, cancer status, cytotoxic therapy, region, timing of COVID diagnosis, baseline ACE inhibitors, baseline ARBs, baseline beta blockers, baseline statins, baseline anticoagulation, aspirin, or APA) from the primary analysis, and one risk factor.

The mutually adjusted model includes all covariates from the primary analysis plus all seven risk factors

Abbreviations: CAD = coronary artery disease, CHF = congestive heart failure, CVD = cardiovascular disease, CVRF = cardiovascular risk factors, CVA = cerebrovascular accident, DM = diabetes mellitus, HLD = hyperlipidemia, HTN = hypertension, PVD = peripheral vascular disease.

Association of CVD/cv risk factors with COVID-19 severity in patients with cancer and recent cancer therapy

Among patients with cancer, 2473 (40%) with CVD/CVRF and 2334 (50%) without CVD/CVRF received any cancer directed therapy within 3 months of COVID-19 diagnosis. The presence of baseline CVD/CVRF was associated with higher COVID-19 severity in patients without recent exposure to cancer directed therapy, but not in those with recent exposure to cancer therapy (OR 1.51 [95% CI 1.31–1.74] vs. OR 1.04 [95% CI 0.90–1.20], interaction p value <0.001).

CVD/CV risk factors and adverse cardiovascular events among SARS-CoV-2-Infected patients with cancer

The incidence of adverse CV events in our cohort is shown in Table 5. Patients with cancer and CVD or CVRF had a statistically higher incidence of adverse CV events, including VTE, MI, AF, VF, cardiomyopathy, symptomatic HF, and CVA compared to patients without CVD/CVRF (Table 5). The incidence of hypotension, either due to distributive or cardiac causes, was also significantly higher in patients with CVD or CVRF (Table 5). Among the various forms of established CVD, a prior history of HF was associated with the greatest incidence of adverse CV events, namely AF and decompensated HF (Table 6).

Table 5.

Adverse cardiovascular events in COVID-19 patients with cancer.

| CV Event |

No CVD/CVRF |

CVRF |

Established CVD |

P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (%) | N | n (%) | N | n (%) | ||

| VTE | 4593 | 186 (4) | 4017 | 214 (5) | 2170 | 101(5) | 0.0194 |

| MI | 4593 | 18 (0) | 4017 | 59 (1) | 2169 | 69 (3) | <0.001 |

| AF | 4593 | 67 (1) | 4027 | 240 (6) | 2171 | 223 (10) | <0.001 |

| VF | 4593 | 2* (0) | 4016 | 13 (0) | 2168 | 14 (1) | <0.001 |

| CMP | 4593 | 5* (0) | 4017 | 25 (1) | 2168 | 32 (1) | <0.001 |

| HF | 4593 | 27 (1) | 4016 | 78 (2) | 2172 | 188 (9) | <0.001 |

| CVA | 4593 | 22 (0) | 4017 | 35 (1) | 2168 | 43 (2) | <0.001 |

| Hypotension | 4597 | 341 (7) | 4029 | 509 (13) | 2173 | 356 (16) | <0.001 |

Fisher's exact test.

Cells with counts 1–4 are masked to minimize the risk of re-identification.

Abbreviations: AF = atrial fibrillation, CMP = cardiomyopathy, CVD = cardiovascular disease, CVRF = cardiovascular risk factors, HF = symptomatic heart failure, VF = ventricular fibrillation, VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Table 6.

Adverse cardiovascular events based on type of established CVD in COVID-19 patients with cancer.

| Baseline |

Total N |

VTE n (%) |

MI n (%) |

AF n (%) |

VF n (%) |

CMP n (%) |

HF n (%) |

CVA n (%) |

Hypotension n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1242 | 38 (3) | 47 (4) | 121 (10) | 10 (1) | 22 (2) | 78 (6) | 17 (1) | 198 (16) | |

| No | 954 | 63 (7) | 22 (3) | 102 (11) | 4* (0) | 10 (1) | 110 (1) | 26 (23) | 158 (17) | |

| PAD | ||||||||||

| Yes | 290 | 13 (4) | 7 (2) | 28 (10) | 1* (0) | 4* (1) | 15 (5) | 3* (1) | 62 (21) | |

| No | 1906 | 88 (5) | 62 (3) | 195 (10) | 13 (1) | 28 (1) | 173 (9) | 40 (2) | 294 (15) | |

| CVA | ||||||||||

| Yes | 538 | 23 (4) | 13 (2) | 50 (9) | 4* (1) | 5* (1) | 35 (7) | 25 (5) | 99 (18) | |

| No | 1658 | 78 (5) | 56 (3) | 173 (10) | 10 (1) | 27 (2) | 153 (9) | 18 (1) | 257 (16) | |

| HF | ||||||||||

| Yes | 783 | 38 (5) | 27 (3) | 111 (14) | 9 (1) | 14 (2) | 146 (19) | 11 (1) | 140 (18) | |

| No | 1413 | 63 (4) | 42 (3) | 112 (8) | 5* (0) | 18 (1) | 42 (3) | 32 (2) | 216 (15) |

Cells with counts 1–4 are masked to minimize the risk of re-identification.

Abbreviations: AF = atrial fibrillation, CAD = coronary artery disease, CMP = cardiomyopathy, CVA = cerebrovascular accident, CVD = cardiovascular disease, HF = heart failure, MI = myocardial infarction, PAD = peripheral arterial disease, VF = ventricular fibrillation, VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Discussion

In this large multi-institutional analysis from the CCC19 database, our results demonstrate that comorbid CVD/CVRF was associated with higher COVID-19 severity in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients with cancer, even after adjustment for demographic and cancer-related characteristics. This increase in COVID-19 severity was only observed in patients who were not exposed to active cancer therapy within 3 months of COVID-19 diagnosis. Our results also demonstrate that COVID-19 related adverse CV events were significantly higher among patients with cancer and co-morbid CVD/CVRF.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, studies have identified CVD/CVRF and cancer as risk factors for adverse outcomes among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8],13]. However, only a few small studies have assessed the impact of co-morbid cancer and CVD/CVRF on COVID-19 related outcomes. Ours is the largest study (n = 10,876) thus far to evaluate a contemporary (3/17/2020 to 12/31/2021) cohort of cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 and we demonstrate that the presence of comorbid CVD/CVRF is associated with higher COVID-19 severity and mortality. Our results agree with a previous single U.S. health system study of 2476 patients that compared COVID-19 related outcomes among patients with co-morbid cancer and CVD (n = 82) to those with cancer (n = 113) or CVD (n = 332) alone [13]. In this study, co-morbid cancer and CVD were associated with more severe disease (HR 1.86, 95% CI 1.11–3.1, p = 0.02) and higher mortality compared to either cancer (35% vs 17%, p = 0.004) or CVD (35% vs 21%, p = 0.009) alone [13]. Similarly, in the UK registry of 800 patients with active cancer and COVID-19, co-morbid CVD was associated with an increased risk of death (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.47–3.64, p = 0.0019) in unadjusted analyses [7]. In contrast, in the multicenter American Heart Association (AHA) COVID-19 CVD Registry, a history of cancer was associated with higher in-hospital mortality and severe disease complications among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, but the presence of baseline CVD (n = 261) did not influence these outcomes. Our results may have differed from those of the AHA COVID-19 CVD Registry due to our larger sample size and due to differing primary outcomes, including the definitions of severe COVID-19 [9].

To our knowledge, ours is the first study to evaluate individual adverse CV events among COVID-19 patients with cancer. Our results demonstrate a significantly higher incidence of COVID-related VTE, MI, AF, VF, cardiomyopathy, symptomatic HF, and CVA events in patients with comorbid CVD/CVRF and cancer compared to patients with cancer alone. In contrast, the AHA COVID-19 CVD Registry evaluated the incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as a composite of in-hospital stroke, HF, MI, sustained ventricular arrhythmias, or heart block requiring temporary or permanent pacemaker, in COVID-19 patients with and without cancer [9]. They demonstrated that while cancer was associated with a higher incidence of MACE (8.6% vs. 5.5%), there was no significant interaction between cancer and CVD [9]. Again, our results may differ due to the occurrence of fewer MACE events (n = 76) among cancer patients in the AHA COVID-19 CVD Registry or due to the different methods by which the effect of CVD/CVRF on adverse CV events was assessed in the two studies. Regardless, the absolute number of adverse CV events was small in both the AHA and CCC19 registries, likely because only CV events that occurred during hospitalization were captured. In fact, adverse CV events can manifest several days after hospitalization as demonstrated by a recent analysis from the US Department of Veterans Affairs which included 153,760 patients with COVID-19 compared to 5 million controls and showed an increased risk of CV events including pericarditis and myocarditis beyond the first 30 days [14]. Thus, long-term observation of COVID-related CV adverse events in patients with comorbid CVD and cancer is warranted.

Although significant, the low absolute number of CV events in patients with comorbid CVD and cancer, suggests that the observed higher in-hospital morbidity and mortality in patients with concomitant CVD/CVRF and cancer was likely secondary to other complications. Indeed, in a single center study in Italy of 839 COVID-19 infected patients with CVD, although MACE, which was defined as composite CV death and CV adverse events, were higher in patients with CVD than no CVD, the most frequent cause of death was respiratory failure [15].

Our study is also the first to show that a prior history of HF in patients with comorbid CVD and cancer was associated with a relative increase in the incidence of individual COVID-related adverse CV events. Analysis from the AHA COVID-19 CVD registry which assessed the association of a prior history of HF and in-hospital mortality demonstrated a higher in-hospital mortality of 31.6% in comparison to 16.9% in patients without HF [9]. This was especially significant in patients with a reduced ejection fraction rather than in patients with a mid-range or preserved ejection fraction. We also demonstrated increased COVID-19 severity in patients with pre-existing HF. Patients with HF often have overlapping comorbid CVD and CVRF and as ours and previous studies have demonstrated, established CVD, HTN and DM are associated with severe COVID-19. While the exact mechanism has not been fully elucidated, direct myocardial injury via the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, decreased innate immunity, chronic inflammation and underlying endothelial dysfunction [16], all characteristics of HF, have also been linked to increased mortality from COVID-19.

We observed worse outcomes in patients with baseline use of beta-blockers. These findings are similar to those observed by Ganatra et al. [13]. A small randomized clinical trial of intravenous metoprolol in twenty COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome showed decreased lung inflammation and improved oxygenation after 3 days of metoprolol [17]. However, it is also plausible that baseline use of beta-blockers exacerbates hypotension or bronchospasm in patients with COVID-19 leading to adverse outcomes. In fact, in our study, patients with CVD/CVRF who were more likely to be on beta-blockers did have a higher prevalence of hypotension. It is also possible that worse outcomes were observed in patients taking beta-blockers as this represents a sicker patient population with residual confounding despite our best attempts at adjusting for multiple patient factors. Further studies are needed to elucidate the effects of beta-blockers in patients with COVID-19.

In our analysis, baseline use of AC and/or APT was associated with higher COVID-19 severity. It is possible that the use of AC and/or APT identified a cohort that was at higher risk for CV complications and VTE. It is difficult to compare our findings with previous reports as the results of prior studies are conflicting and do not include a large proportion of patients with the dual diagnoses of cancer and CVD. Both small [18,19] and large-scale studies [20] have shown no association as well as better COVID-19 outcomes [21,22] in patients with prior history of AC use. Current guidelines from the National Institutes of Health recommend continuing chronic AC in patients who are hospitalized for COVID-19. With respect to initiating anticoagulation for VTE prophylaxis at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, there are differing consensus recommendations. Further clarity on this topic should be forthcoming when the results of current trials are reported.

The association between active chemotherapy and COVID-19 outcomes is unclear. Prior reports from both the CCC19 [12] and AHA registries [9] have suggested that recent chemotherapy is associated with increased in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients with cancer. However, others have reported no association between active chemotherapy and COVID-19 outcomes [6,7,23]. In our study, we observed a significant interaction between comorbid CVD/CVRF and recent cancer therapy, whereby CVD/CVRF worsened COVID-19 severity only in patients who had not received recent cancer therapy. While speculative, these results suggest that CVD/CVRF may add risk in those cancer patients who are not actively immunocompromised. Similarly, the association of specific types of chemotherapy and COVID-19 severity are conflicting with studies demonstrating no association between cytotoxic chemotherapy [6,23] and worse COVID-19 outcomes while later analyses from the CCC19 database showed higher COVID-19 severity and 30-day mortality [12]. In adjusted models, our results were consistent with Grivas and colleague's report of increased COVID severity with cytotoxic as well as locoregional therapy. It is important to note however that while not detailed in this study, there is significant variability in the regimen of cytotoxic chemotherapy within the CCC19 registry and thus, may be subject to unmeasured confounding.

Study limitations

First, the CCC19 registry is a retrospective voluntary registry of patients with cancer and COVID-19 and has inherent limitations related to selection bias and data entry; the former is mitigated by the large number of participating sites, including community practices and international sites, and the latter is overcome by data quality controls, queries, and imputation of missing data. Second, the current analysis did not account for unmeasured confounders such as renal, pulmonary, and liver disease. Third, while we are unable to fully explain the higher COVID-19 severity observed in patients with cancer and co-morbid CVD/CVRF, we were able to demonstrate an increased incidence of CV events in COVID-19 patients with dual diagnoses of cancer and CVD, but the small numbers of events did not allow for multivariable modeling. Fourth, at the time of analysis, we had incomplete information on COVID-19 vaccination status and specific strain information was not captured and therefore we were unable to include these factors in multivariable models. However, we did adjust for calendar time to account not only for improvements in patient care over time, but also trends in vaccination and variants.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our analysis of the CCC19 registry demonstrates that the presence of co-morbid CVD/CVRF is associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 severity. We observed a significantly higher incidence of adverse CV events in COVID-19 patients with cancer and comorbid CVD/CVRF, which may in part have contributed to higher COVID-19 severity. Furthermore, we observed a significant interaction between CVD/CVRF and recent cancer therapy on COVID-19 severity in patients with cancer. These results suggest that patients with cancer and co-morbid CVD/CVRF should be considered for earlier antiviral and immunomodulator therapy, even if they are not receiving active cancer directed therapy. Considering the increased risk of adverse COVID-19 outcomes, hospital visits in patients with cancer and co-morbid CVD/CVRF should be carefully considered and only performed when necessary, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, the National Institute of Health (NIH) recommends initiation of antiviral and immunomodulator therapy based on COVID-19 disease severity [24], however based on our data, earlier treatment could be considered in this vulnerable high-risk patient population to prevent worse outcomes. Furthermore, certain cardiac medications, such as beta-blockers, AC, and APT, require further safety evaluation in patients with cancer and COVID-19, regardless of CVD/CVRF. Further studies are warranted.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Melissa Y.Y. Moey: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Cassandra Hennessy: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Benjamin French: Project administration, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Jeremy L. Warner: Project administration, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Matthew D. Tucker: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Daniel J. Hausrath: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Dimpy P. Shah: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Jeanne M. DeCara: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Ziad Bakouny: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Chris Labaki: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Toni K. Choueiri: Project administration, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Susan Dent: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Nausheen Akhter: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Roohi Ismail-Khan: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Lisa Tachiki: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. David Slosky: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Tamar S. Polonsky: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Joy A. Awosika: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Audrey Crago: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Trisha Wise-Draper: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Nino Balanchivadze: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Clara Hwang: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Leslie A. Fecher: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Cyndi Gonzalez Gomez: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Brandon Hayes-Lattin: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Michael J. Glover: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Sumit A. Shah: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Dharmesh Gopalakrishnan: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Elizabeth A. Griffiths: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Daniel H. Kwon: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Vadim S. Koshkin: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Sana Mahmood: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Babar Bashir: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Taylor Nonato: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Pedram Razavi: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Rana R. McKay: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Gayathri Nagaraj: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Eric Oligino: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Matthew Puc: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Polina Tregubenko: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Elizabeth M. Wulff-Burchfield: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Zhuoer Xie: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Thorvardur R. Halfdanarson: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Dimitrios Farmakiotis: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Elizabeth J. Klein: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Elizabeth V. Robilotti: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Gregory J. Riely: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Jean-Bernard Durand: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Salim S. Hayek: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Lavanya Kondapalli: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Stephanie Berg: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Timothy E. O'Connor: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Mehmet A. Bilen: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Cecilia Castellano: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Melissa K. Accordino: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Blau Sibel: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Lisa B. Weissmann: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Chinmay Jani: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Daniel B. Flora: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Lawrence Rudski: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Miriam Santos Dutra: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Bouganim Nathaniel: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Erika Ruíz-García: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Diana Vilar-Compte: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Shilpa Gupta: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Alicia Morgans: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. Anju Nohria: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

R.M reports research funding from Bayer, Pfizer, and Tempus; and 18 personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Calithera, 19 Caris, Dendreon, Exelixis, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, Merck & Co, Myovant, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sorrento Therapeutics, Tempus, and Vividion. A.N. reports consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Takeda Oncology and Bantam Pharmaceuticals. B.B. reports research support to institution from Amgen, Bicycle Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ikena Oncology, Kahr Medical, Merck, Syros, Tarveda Therapeutics. Z.B. receives research support from Genentech/imCORE and Bristol Myers Squibb. Personal fees from UpToDate. L.A.F reports clinical trial funding from BMS, EMDserono, Pfizer, Merck, Array, Kartos, Incyte, personal fees from Elsevier, ViaOncology, outside the submitted work. J.L.W. reports research funding from NIH/NCI during the conduct of the work, research funding from AACR, consulting fees from Westat, Roche, Flatiron Health, Melax Tech, other from HemOnc.org LLC (ownership), outside the submitted work. C.H reports stock holdings in Johnson and Johnson; research funding to institution from Merck, Bausch Health, Genentech, Bayer, and AstraZeneca, consultant fees from Tempus, Genzyme, and EMD Sorono, speaking fees from OncLive/MJH Life Sciences, travel fees from Merck, all outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the CCC19 steering committee: Toni K. Choueiri, Narjust Duma, Dimitrios Farmakiotis, Petros Grivas, Gilberto de Lima Lopes Jr, Corrie A. Painter, Solange Peters, Brian I. Rini, Dimpy P. Shah, Michael A. Thompson, and Jeremy L. Warner, for their invaluable guidance of the CCC19.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P30CA016056 involving the use of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center's Hematologic Procurement Shared Resource and grant P30 CA123456. This study was also supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute grant number P30 CA068485 to Vanderbilt University Medical Center. REDCap is developed and supported by Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research grant support (UL1 TR000445 from NCATS / NIH). The funding sources had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Contributor Information

Alicia Morgans, Email: aliciak_morgans@dcfi.harvard.edu.

Anju Nohria, Email: anohria@bwh.harvard.edu.

Appendix

Alphabetical list of participants by institution that contributed at least one record to the analysis.

Bolded = site PI/co-PIs; site co-investigators are listed alphabetically by last name.

-

•

Balazs Halmos, MD; Amit Verma, MBBS; Benjamin A. Gartrell, MD; Sanjay Goel, MBBS; Nitin Ohri, MD; R. Alejandro Sica, MD; Astha Thakkar, MD (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY, USA)

-

•

Keith E. Stockerl-Goldstein, MD; Omar Butt, MD, PhD; Jian Li Campian, MD, PhD; Mark A. Fiala, MSW; Jeffrey P. Henderson, MD, PhD; Ryan S. Monahan, MBA; Alice Y. Zhou, MD, PhD (Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, MO, USA)

-

•

Sigrun Hallmeyer, MD; Pamela Bohachek, RN, CCRC; Daniel Mundt, MD; Sasirekha Pandravada, DO; Mauli Patel, DO; Mitrianna Streckfuss, MPH; Eyob Tadesse, MD; Michael A. Thompson, MD, PhD, FASCO (Aurora Cancer Care, Advocate Aurora Health, Milwaukee, WI, USA)

-

•

Philip E. Lammers, MD, MSCI (Baptist Cancer Center, Memphis, TN, USA)

-

•

Sanjay G. Revankar, MD, FIDSA (The Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, USA)

-

•

Jonathan M. Loree, MD, MS, FRCPC; Irene S. Yu, MD, FRCPC (BC Cancer, Vancouver, BC, Canada)

-

•

Mary Linton B. Peters, MD, MS, FACP; Poorva Bindal, MD; Jaymin M. Patel, MD; Andrew J. Piper-Vallillo, MD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA)

-

•

Dimitrios Farmakiotis, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Pamela C. Egan, MD; Hina Khan, MD; Elizabeth J. Klein, BA; Adam J. Olszewski, MD; Kendra Vieira, BS (Brown University and Lifespan Cancer Institute, Providence, RI, USA)

-

•

Arturo Loaiza-Bonilla, MD, MSEd, FACP (Cancer Treatment Centers of America, AZ/GA/IL/OK/PA, USA)

-

•

Salvatore A. Del Prete, MD; Michael H. Bar, MD, FACP; Anthony P. Gulati, MD; K. M. Steve Lo, MD; Suzanne J. Rose, MS, PhD, CCRC, FACRP; Jamie Stratton, MD; Paul L. Weinstein, MD (Carl & Dorothy Bennett Cancer Center at Stamford Hospital, Stamford, CT, USA)

-

•

Jorge A. Garcia, MD, FACP (Case Comprehensive Cancer Center at Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals, Cleveland, OH, USA)

-

•

Bertrand Routy, MD, PhD (center Hospitalier de l'Universit<e9> de Montr<e9>al, Montreal, QC, Canada)

-

•

Irma Hoyo-Ulloa, MD (Centro M<e9>dico ABC, Ciudad de M<e9>xico, CDMX, Mexico)

-

•

Shilpa Gupta, MD; Nathan A. Pennell, MD, PhD, FASCO; Manmeet S. Ahluwalia, MD, FACP; Scott J. Dawsey, MD; Christopher A. Lemmon, MD; Amanda Nizam, MD; Nima Sharifi, MD (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA)

-

•

Claire Hoppenot, MD; Ang Li, MD, MS (Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA)

-

•

Toni K. Choueiri, MD; Ziad Bakouny, MD, MSc; Jean M. Connors, MD; George D. Demetri, MD, FASCO; Dory A. Freeman, BS; Antonio Giordano, MD, PhD; Chris Labaki, MD; Alicia K. Morgans, MD, MPH; Anju Nohria, MD; Andrew L. Schmidt, MD; Eliezer M. Van Allen, MD; Pier Vitale Nuzzo, MD, PhD; Wenxin (Vincent) Xu, MD; Rebecca L. Zon, MD (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA)

-

•

Susan Halabi, PhD, FASCO, FSCT, FASA; Hannah Dzimitrowicz, MD; Tian Zhang, MD, MHS (Duke Cancer Institute at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA)

-

•

John C. Leighton Jr, MD, FACP (Einstein Healthcare Network, Philadelphia, PA, USA)

-

•

Gary H. Lyman, MD, MPH, FASCO, FRCP; Jerome J. Graber MD, MPH; Petros Grivas, MD, PhD; Jessica E. Hawley, MD; Elizabeth T. Loggers, MD, PhD; Ryan C. Lynch, MD; Elizabeth S. Nakasone, MD, PhD; Michael T. Schweizer, MD; Lisa Tachiki, MD; Shaveta Vinayak, MD, MS; Michael J. Wagner, MD; Albert Yeh, MD (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/University of Washington/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, Seattle, WA, USA)

-

•

Na Tosha N. Gatson, MD, PhD, FAAN; Joseph Vadakara, MD; Yvonne Dansoa, DO; Kristena Yossef, MD; and Mina Makary, MD (Geisinger Health System, PA, USA)

-

•

Sharad Goyal, MD; Minh-Phuong Huynh-Le, MD, MAS (George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA)

-

•

Lori J. Rosenstein, MD (Gundersen Health System, WI, USA)

-

•

Peter Paul Yu, MD, FACP, FASCO; Jessica M. Clement, MD; Ahmad Daher, MD; Mark E. Dailey, MD; Rawad Elias, MD; Asha Jayaraj, MD; Emily Hsu, MD; Alvaro G. Menendez, MD; Oscar K. Serrano, MD, MBA, FACS (Hartford HealthCare Cancer Institute, Hartford, CT, USA)

-

•

Clara Hwang, MD; Shirish M. Gadgeel, MD (Henry Ford Cancer Institute, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA)

-

•

Melissa K. Accordino, MD, MS; Divaya Bhutani, MD; Dawn Hershman, MD, MS, FASCO; Gary K. Schwartz, MD (Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University, New York, NY, USA)

-

•

Daniel Y. Reuben, MD, MS; Mariam Alexander, MD, PhD; Sara Matar, MD; Sarah Mushtaq, MD (Hollings Cancer Center at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA)

-

•

Eric H. Bernicker, MD (Houston Methodist Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA)

-

•

John F. Deeken, MD; Danielle Shafer, DO (Inova Schar Cancer Institute, Fairfax, VA, USA)

-

•

Erika Ruíz-García, MD, MCs; Ana Ramirez, MD; Diana Vilar-Compte, MD, MsC (Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia, Mexico City, Mexico)

-

•

Mark A. Lewis, MD; Terence D. Rhodes, MD, PhD; David M. Gill, MD; Clarke A. Low, MD (Intermountain Health Care, Salt Lake City, UT, USA)

-

•

Sandeep H. Mashru, MD; Abdul-Hai Mansoor, MD (Kaiser Permanente Northwest, OR/WA, USA)

-

•

Brandon Hayes-Lattin, MD, FACP; Aaron M. Cohen, MD, MS; Shannon McWeeney, PhD; Eneida R. Nemecek, MD, MS, MBA; Staci P. Williamson, BS (Knight Cancer Institute at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA)

-

•

Howard A. Zaren, MD, FACS; Stephanie J. Smith, RN, MSN, OCN (Lewis Cancer & Research Pavilion @ St. Joseph's/Candler, Savannah, GA, USA)

-

•

Gayathri Nagaraj, MD; Mojtaba Akhtari, MD; Dan R. Castillo, MD; Eric Lau, DO; Mark E. Reeves, MD, PhD (Loma Linda University Cancer Center, Loma Linda, CA, USA)

-

•

Stephanie Berg, DO; Natalie Knox; Timothy E. O'connor, MD (Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, IL, USA)

-

•

Firas H. Wehbe, MD, PhD; Jessica Altman, MD; Michael Gurley, BA; Mary F. Mulcahy, MD (Lurie Cancer Center at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA)

-

•

Eric B. Durbin, DrPH, MS (Markey Cancer Center at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA)

-

•

Amit A. Kulkarni, MD; Heather H. Nelson, PhD, MPH; Zohar Sachs, MD, PhD (Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA)

-

•

Rachel P. Rosovsky, MD, MPH; Kerry L. Reynolds, MD; Aditya Bardia, MD; Genevieve Boland, MD, PhD, FACS; Justin F. Gainor, MD; Leyre Zubiri, MD, PhD (Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston, MA, USA)

-

•

Thorvardur R. Halfdanarson, MD; Tanios S. Bekaii-Saab, MD, FACP; Aakash Desai, MD, MPH; Irbaz B. Riaz, MD, MS; Surbhi Shah, MD; Zhuoer Xie, MD, MS (Mayo Clinic, AZ/FL/MN, USA)

-

•

Ruben A. Mesa, MD, FACP; Mark Bonnen, MD; Daruka Mahadevan, MD, PhD; Amelie G. Ramirez, DrPH, MPH; Mary Salazar, DNP, MSN, RN, ANP-BC; Dimpy P. Shah, MD, PhD; Pankil K. Shah, MD, MSPH (Mays Cancer Center at UT Health San Antonio MD Anderson Cancer Center, San Antonio, TX, USA)

-

•

Nathaniel Bouganim, MD, FRCP(C); Arielle Elkrief, MD, FRCP(C); Justin Panasci; Donald C. Vinh, MD, FRCP(C) (McGill University Health center, Montreal, QC, Canada)

-

•

Rahul Nanchal, MD; Harpreet Singh, MD (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA)

-

•

Gregory J. Riely, MD, PhD; Elizabeth V. Robilotti MD, MPH; Rimma Belenkaya, MA, MS; John Philip, MS (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA)

-

•

Rulla Tamimi, MS (Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, USA)

-

•

Bryan Faller, MD (Missouri Baptist Medical Center, St. Louis, MO, USA)

-

•

Rana R. McKay, MD; Archana Ajmera, MSN, ANP-BC, AOCNP; Sharon S. Brouha, MD, MPH; Angelo Cabal, BS; Sharon Choi, MD, PhD; Albert Hsiao, MD, PhD; Jun Yang Jiang, MD; Seth Kligerman, MD; Taylor K. Nonato; Erin G. Reid, MD (Moores Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA)

-

•

Lisa B. Weissmann, MD; Chinmay Jani, MD; Carey C. Thomson, MD, FCCP, MPH (Mount Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, MA, USA)

-

•

Jeanna Knoble, MD; Mary Grace Glace, RN; Cameron Rink, PhD, MBA; Karen Stauffer, RN; Rosemary Zacks, RN (Mount Carmel Health System, Columbus, OH, USA)

-

•

Sibel Blau, MD (Northwest Medical Specialties, Tacoma, WA, USA)

-

•

Sachin R. Jhawar, MD; Daniel Addison, MD; James L. Chen, MD; Margaret E. Gatti-Mays, MD; Vidhya Karivedu, MBBS; Joshua D. Palmer, MD; Daniel G. Stover, MD; Sarah Wall, MD; Nicole O. Williams, MD (The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH, USA)

-

•

Monika Joshi, MD, MRCP; Hyma V. Polimera, MD; Lauren D. Pomerantz; Marc A. Rovito, MD, FACP (Penn State Health/Penn State Cancer Institute/St. Joseph Cancer Center, PA, USA)

-

•

Hagen F. Kennecke, MD, MHA, FRCPC (Providence Cancer Institute, Portland, OR, USA)

-

•

Elizabeth A. Griffiths, MD; Amro Elshoury, MBBCh (Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, NY, USA)

-

•

Salma K. Jabbour, MD; Christian F. Misdary, MD; Mansi R. Shah, MD (Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey at Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, New Brunswick, NJ, USA)

-

•

Gerald Batist, MD, FACP, FRCP; Erin Cook, MSN; Miriam Santos Dutra, PhD; Cristiano Ferrario, MD; Wilson H. Miller Jr., MD, PhD (Segal Cancer center, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada)

-

•

Babar Bashir, MD, MS; Christopher McNair, PhD; Sana Z. Mahmood, BA, BS; Vasil Mico, BS; Andrea Verghese Rivera, MD (Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA)

-

•

Sumit A. Shah, MD, MPH; Elwyn C. Cabebe, MD; Michael J. Glover, MD; Alokkumar Jha, PhD; Ali Raza Khaki, MD; Lidia Schapira, MD, FASCO; Julie Tsu-Yu Wu, MD, PhD (Stanford Cancer Institute at Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA)

-

•

Suki Subbiah, MD (Stanley S. Scott Cancer Center at LSU Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA)

-

•

Daniel B. Flora, MD, PharmD; Goetz Kloecker, MD; Barbara B. Logan, MS; Chaitanya Mandapakala, MD (St. Elizabeth Healthcare, Edgewood, KY, USA)

-

•

Gilberto de Lima Lopes Jr., MD, MBA, FAMS, FASCO (Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA)

-

•

Karen Russell, MD, FACP; Karen DeCardenas, RN, BSN; Brittany Stith, RN, BSN, OCN, CCRP (Tallahassee Memorial Healthcare, Tallahassee, FL, USA)

-

•

Natasha C. Edwin, MD; Melissa Smits, APC (ThedaCare Cancer Care, Appleton, WI, USA)

-

•

David D. Chism, MD; Susie Owenby, RN, CCRP (Thompson Cancer Survival Center, Knoxville, TN, USA)

-

•

Deborah B. Doroshow, MD, PhD; Matthew D. Galsky, MD; Michael Wotman, MD (Tisch Cancer Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA)

-

•

Jeffrey Berenberg, MD, MACP (Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, HI, USA)

-

•

Alyson Fazio, APRN-BC; Julie C. Fu, MD; Kathryn E. Huber, MD; Mark H. Sueyoshi, MD (Tufts Medical Center Cancer Center, Boston and Stoneham, MA, USA)

-

•

Jonathan Riess, MD, MS; Kanishka G. Patel, MD (UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California at Davis, CA, USA)

-

•

Vadim S. Koshkin, MD; Hala T. Borno, MD; Daniel H. Kwon, MD; Eric J. Small, MD; Sylvia Zhang, MS (UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California at San Francisco, CA, USA)

-

•

Samuel M. Rubinstein, MD; William A. Wood, MD, MPH; Tessa M. Andermann, MD; Christopher Jensen, MD (UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Chapel Hill, NC, USA)

-

•

Trisha M. Wise-Draper, MD, PhD; Syed A. Ahmad, MD, FACS; Punita Grover, MD; Shuchi Gulati, MD, MS; Jordan Kharofa, MD; Tahir Latif, MBBS, MBA; Michelle Marcum, MS; Hira G. Shaikh; MD; Davendra P. Sohal, MD, MPH (University of Cincinnati Cancer Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA)

-

•

Daniel W. Bowles, MD; Christoper L. Geiger, MD (University of Colorado Cancer Center, Aurora, CO, USA)

-

•

Merry-Jennifer Markham, MD, FACP, FASCO; Atlantis D. Russ, MD, PhD; Haneen Saker, MD (University of Florida Health Cancer Center, Gainesville, FL, USA)

-

•

Jared D. Acoba, MD; Young Soo Rho, MD, CM (University of Hawai'i Cancer Center, Honolulu, HI, USA)

-

•

Lawrence E. Feldman, MD; Kent F. Hoskins, MD; Gerald Gantt Jr., MD; Li C. Liu, PhD; Mahir Khan, MD; Ryan H. Nguyen, DO; Mary Pasquinelli, APN, DNP; Candice Schwartz, MD; Neeta K. Venepalli, MD, MBA (University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System, Chicago, IL, USA)

-

•

Praveen Vikas, MD (University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, Iowa City, IA, USA)

-

•

Elizabeth Wulff-Burchfield, MD; Anup Kasi MD, MPH; Crosby D. Rock, MD (The University of Kansas Cancer Center, Kansas City, KS, USA)

-

•

Christopher R. Friese, PhD, RN, AOCN, FAAN; Leslie A. Fecher, MD (University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center, Ann Arbor, MI, USA)

-

•

Blanche H. Mavromatis, MD; Ragneel R. Bijjula, MD; Qamar U. Zaman, MD (UPMC Western Maryland, Cumberland, MD, USA)

-

•

Jeremy L. Warner, MD, MS, FAMIA, FASCO; Alicia Beeghly-Fadiel, PhD; Alaina J. Brown, MD, MPH; Lawrence Justin Charles, MD; Alex Cheng, PhD; Marta A. Crispens, MD; Sarah Croessmann, PhD; Elizabeth J. Davis, MD; Kyle T. Enriquez, MSc BS; Erin A. Gillaspie, MD, MPH; Daniel Hausrath, MD; Douglas B. Johnson, MD, MSCI; Xuanyi Li, MD; Sanjay Mishra, MS, PhD; Lauren S. Prescott; MD, MPH; Sonya A. Reid, MD, MPH; Brian I. Rini, MD, FACP, FASCO; David A. Slosky, MD; Carmen C. Solorzano, MD, FACS; Matthew D. Tucker, MD; Karen Vega-Luna, MA; Lucy L. Wang, BA (Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA)

-

•

David M. Aboulafia, MD; Brett A. Schroeder, MD (Virginia Mason Cancer Institute, Seattle, WA, USA)

-

•

Matthew Puc, MD; Theresa M. Carducci, MSN, RN, CCRP; Karen J. Goldsmith, BSN, RN; Susan Van Loon, RN, CTR, CCRP (Virtua Health, Marlton, NJ, USA)

-

•

Umit Topaloglu, PhD, FAMIA; Saif I. Alimohamed, MD (Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center, Winston-Salem, NC, USA)

-

•

Joan K. Moore, MSN, RN, OCN, CCRP (WellSpan Health, York, PA, USA)

-

•

Wilhelmina D. Cabalona, MD; Sandra Cyr (Wentworth-Douglass Hospital, Dover, NH, USA)

-

•

Prakash Peddi, MD; Lane R. Rosen, MD; Briana Barrow McCollough, BSc, CCRC (Willis-Knighton Cancer Center, Shreveport, LA, USA)

-

•

Mehmet A. Bilen, MD; Cecilia A. Castellano; Deepak Ravindranathan, MD, MS (Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA)

-

•

Navid Hafez, MD, MPH; Roy Herbst, MD, PhD; Patricia LoRusso, DO, PhD; Maryam B. Lustberg, MD, MPH; Tyler Masters, MS; Catherine Stratton, BA (Yale Cancer Center at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA)

References

- 1.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A.K., Gillies C.L., Singh R., et al. Prevalence of co-morbidities and their association with mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020;22:1915–1924. doi: 10.1111/dom.14124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin T., Li Y., Ying Y., Luo Z. Prevalence of comorbidity in Chinese patients with COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:200. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05915-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuderer N.M., Choueiri T.K., Shah D.P., et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee L.Y., Cazier J.-B., Angelis V., et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1919–1926. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saini K.S., Tagliamento M., Lambertini M., et al. Mortality in patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and pooled analysis of 52 studies. Eur. J. Cancer. 2020;139:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tehrani D., Wang X., Rafique A.M., et al. Impact of cancer and cardiovascular disease on in-hospital outcomes of COVID-19 patients: results from the American heart association COVID-19 cardiovascular disease registry. Res. Sq. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s40959-021-00113-y. rs.3.rs-600795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubinstein S.M., Steinharter J.A., Warner J., Rini B.I., Peters S., Choueiri T.K. The COVID-19 and cancer consortium: a collaborative effort to understand the effects of COVID-19 on patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:738–741. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium Electronic address: jeremy.warner@vumc.org, COVID-19 and cancer consortium. A systematic framework to rapidly obtain data on patients with cancer and COVID-19: CCC19 governance, protocol, and quality assurance. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:761–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grivas P., Khaki A.R., Wise-Draper T.M., et al. Association of clinical factors and recent anticancer therapy with COVID-19 severity among patients with cancer: a report from the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium. Ann. Oncol. 2021;32:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganatra S., Dani S.S., Redd R., et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with a history of cancer and comorbid cardiovascular disease. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie Y., Xu E., Bowe B., Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022;28:583–590. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tessitore E., Carballo D., Poncet A., et al. Mortality and high risk of major adverse events in patients with COVID-19 and history of cardiovascular disease. Open Heart. 2021;8 doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu S.X., Tyagi T., Jain K., et al. Thrombocytopathy and endotheliopathy: crucial contributors to COVID-19 thromboinflammation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021;18:194–209. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-00469-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clemente-Moragón A., Martínez-Milla J., Oliver E., et al. Metoprolol in critically Ill patients with COVID-19. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021;78:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sivaloganathan H., Ladikou E.E., Chevassut T. COVID-19 mortality in patients on anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;190:e192–e195. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrochano M., Acosta-Isaac R., Mojal S., et al. Impact of pre-admission antithrombotic therapy on disease severity and mortality in patients hospitalized for COVID-19. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2022;53(1):96–102. doi: 10.1007/s11239-021-02507-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flam B., Wintzell V., Ludvigsson J.F., Mårtensson J., Pasternak B. Direct oral anticoagulant use and risk of severe COVID-19. J. Intern Med. 2021;289:411–419. doi: 10.1111/joim.13205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivera-Caravaca J.M., Núñez-Gil I.J., Vivas D., et al. Clinical profile and prognosis in patients on oral anticoagulation before admission for COVID-19. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;51:e13436. doi: 10.1111/eci.13436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chocron R., Galand V., Cellier J., et al. Anticoagulation before hospitalization is a potential protective factor for COVID-19: insight from a French multicenter cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021;10 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Várnai C., Palles C., Arnold R., et al. Mortality among adults with cancer undergoing chemotherapy or immunotherapy and infected with COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. 2022. Available at: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/.