Abstract

Background

The incidence of alopecia areata (AA) has increased over the last few decades. Trichoscopy is a noninvasive procedure performed in dermatology clinics and is a helpful tool in determining the correct diagnosis of hair loss presentations.

Objective

Through mapping the researches that have been done to represent the spectrum of trichoscopic findings in AA and to identify the most characteristic patterns.

Methods

Thirty‐nine studies were eligible for the quantitative analysis. Meta‐analysis and subgroup analysis were performed.

Results

Thirty‐nine studies (29 cross‐sectional, five retrospective, two descriptive, one case series, one observational, and one cohort) with a total of 3204 patients were included. About 66.7% of the studies were from Asia, 25.6% from Europe, and 7.7% from Africa. The most characteristic trichoscopic findings of AA were as follows; yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and tapering hairs.

Conclusion

There is no single pathognomonic diagnostic trichoscopic finding in AA rather than a constellation of characteristic findings. The five most characteristic trichoscopic findings in AA are: yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and tapering hairs. Yellow dots and short vellus hairs considered the most sensitive clues for AA, while black dots and tapering hairs are the most specific ones. Furthermore, trichoscopy is a useful tool that allows monitoring of response during the treatment of AA. Treatment responded cases will show an increase in short vellus hairs, but loss of tapering hairs, broken hairs, and black dots, while yellow dots are the least responsive to the treatment.

Keywords: alopecia areata, and tapering hairs, black dots, broken hairs, dermatoscopy, short vellus hairs, trichoscopic pattern, trichoscopy, videodermoscopy, vitamin D deficiency, yellow dots

1. INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is a relatively common cell‐mediated autoimmune nonscarring hair loss disease that targets anagen hair follicles. 1 It can affect any hair‐bearing areas in both adults and children. 2 The estimated prevalence of AA is one in 1000 people. The lifetime risk is 2% in the general population 3 and 0.63% in the pediatric population. 4

According to the extent of hair loss, AA can be divided into three categories: patchy alopecia, which causes partial scalp hair loss; alopecia totalis, which causes whole scalp hair loss; and alopecia universalis, which causes complete scalp and body hair loss. Different clinical types of scalp hair loss may be seen clinically, including patchy, ophiasis (band‐like hair loss in the parieto‐temporo‐occipital area), ophiasis inversus‐sisaipho (band‐like hair loss in the fronto‐parieto‐temporal area), reticulate, and diffuse. 5

The involvement of cosmetically concern regions, such as the scalp, beard, mustache, eyebrows, and eyelashes, can result in psychological distress. 6 The clinical diagnosis of AA is usually straightforward; however, some hair conditions like tinea capitis, trichotillomania, telogen effluvium, androgenetic alopecia, or traction alopecia can be of challenge with confusing clinical features. 7

AA has an unpredictable course, with 80% of patients experiencing spontaneous hair regrowth during the first year; however, relapse can occur at any time during life. 5 Following are the main bad prognosis predictors: severity of hair loss (extensive AA, alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis), 8 ophiasis pattern of hair loss, long duration of the disease, 9 atopy, positive family history, other autoimmune diseases, nail involvement, and the young age at first onset. 10

Trichoscopy is used in patients with scarring or nonscarring hair loss conditions as a quick, noninvasive, and modern method to examine the scalp and hair. In addition, it is a helpful monitoring tool during a therapeutic journey. 11 , 12

It facilitates establishing an accurate diagnosis with increased sensitivity and specificity. The method allows visualizing at high magnification with the advantage of being a noninvasive assessment method of the scalp and hair. 13

In 2004, Lacarrubba et al. 14 published the first description of the trichoscopic characteristics of AA. Since then, research has been published examining the use of trichoscopy in AA diagnosis, evaluation of disease activity, severity, prognosis, and therapyx monitoring. 14

1.1. Objectives

To conduct a systematic review and meta‐analysis mapping trichoscopic findings in patients with AA and to identify the most characteristic patterns. The following research question was formulated: What are the most characteristic trichoscopic patterns in patients with AA?

2. METHODS

2.1. Study registration

The protocol has been defined and registered online in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO), and the registration number is CRD42022326248.

2.2. Study design and search strategy

Our protocol strictly adhered to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses Protocols (PRISMA) guidelines. 15

An intensive review of the published work regarding trichoscopic findings of AA was performed by searching the following bibliographic databases from 2004 to July 2022: Google Scholar, Scopus, EBSCO, and PubMed. The PICOS protocol was used in the preparation of the following search tactics:

P (population): adult OR child OR children;

I (intervention/exposure): trichoscopy, dermatoscopy, dermoscopy, or videodermoscopy;

C (comparison): without trichoscopy OR dermatoscopy OR dermoscopy OR videodermoscopy;

O (outcome): AA OR areata;

S (study design): all possible.

As for the research terms, the Boolean operator (AND, OR) was applied with the MeSH and non‐MeSH terms in the search bar as follows: (AA [MeSH] OR alopecia [MeSH]) AND (trichoscopy [MeSH] OR dermatoscopy [MeSH] OR dermoscopy [MeSH] OR videodermoscopy [MeSH]) AND (adult [MeSH] OR child [MeSH] OR children) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Searching strategies for PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar.

| PubMed | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| #1 | Alopecia areata [MeSH] |

| #2 | Areata [MeSH] |

| #3 | Trichoscopy [MeSH] |

| #4 | Dermatoscopy [MeSH] |

| #5 | Dermoscopy [MeSH] |

| #6 | Videodermoscopy [MeSH] |

| #7 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 |

| #8 | Adult [MeSH] |

| #9 | Child [MeSH] |

| #10 | Children [MeSH] |

| #11 | #8 OR #9 OR #10 |

| Embase | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| #1 | Alopecia areata [MeSH] ti, ab, kw |

| #2 | Areata [MeSH] ti, ab, kw |

| #3 | Trichoscopy [MeSH] |

| #4 | Dermatoscopy [MeSH] ti, ab, kw |

| #5 | Dermoscopy [MeSH] ti, ab, kw |

| #6 | Videodermoscopy [MeSH] ti, ab, kw |

| #7 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 |

| #8 | Adult [MeSH] ti, ab, kw |

| #9 | Child [MeSH] ti, ab, kw |

| #10 | Children [MeSH] ti, ab, kw |

| #11 | #8 OR #9 OR #10 |

| Google Scholar | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| #1 | all in the title: Alopecia areata OR “areata” AND “Trichoscopy” OR “Dermatoscopy” OR “Dermoscopy” OR “Videodermoscopy” AND “adult” OR “Child” OR “Children” |

2.3. Eligibility criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

We included full‐text English language published studies about the trichoscopic findings in AA as cross‐sectional, observational, descriptive, cohort, retrospective, comparative, and case series.

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

We eliminated all animal studies, no matter the study designs, and those studies with no main epidemiologic data describing the numbers of individuals with AA or the prevalence of unimportant follicular trichoscopic findings.

2.3.3. Types of participants

We include patients of both sexes and at any age with AA investigated with any device such as trichoscopy, dermatoscopy, dermoscopy, or videodermoscopy.

2.3.4. Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of interest is to find the most common trichoscopic findings in patients with AA.

Secondary outcome

It includes other common trichoscopic findings in AA and the correlation between various trichoscopic findings in AA.

2.4. Data collection and analysis

2.4.1. Selection of studies

Two independent reviewers (MD, AI) screened titles and abstracts. They checked the full texts of eligible studies considering the above‐mentioned criteria. Duplicates were omitted using EndNote software version 20.2.1. Studies that meet the predetermined inclusion criteria were chosen. Records management was done using EndNote software.

2.5. Data extraction and management

By using The Joanna Briggs Institute Meta‐Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument, we assessed the included references. 16 Two independent reviewers (AA and GA) extracted data from the included studies. The following information was extracted using a predetermined data form: authors, years of publications, country, research design, study population, type of AA, information about trichoscopic findings like yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and tapering hairs. The data were entered directly into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

2.6. Quality assessment

The modified Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS), used to rate the caliber of cross‐sectional or case–control studies, was used to evaluate each study's caliber. The NOS, which has a maximum score of nine stars, was used to evaluate three major domains, including selecting participants, comparing research groups, and determining outcomes of interest in each study. Studies considered excellent quality if their NOS rating was seven stars or above (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

The modified Newcastle‐Ottawa scale rating for included studies: (* or ** means criteria fulfilled/maximum score = 9).

| Studies | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total number of stars |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lacarrubba et al. 2004 14 | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| Ross et al. 2006 48 | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| Inui et al. 2008 20 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Inui et al. 2010 21 | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| Mane et al. 2011 22 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Karadağ Köse & Güleç 2012 23 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Hegde et al. 2013 24 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Peter et al. 2013 25 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Ankad et al. 2014 55 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Bapu et al. 2014 53 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Ekiz et al. 2014 26 | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| El‐Taweel et al. 2014 27 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Nikam & Mehta 2014 47 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Rakowska et al. 2014 46 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Shim et al. 2014 28 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Kibar et al. 2015 29 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Park et al. 2015 30 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Chiramel et al. 2016 31 | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| Guttikonda et al. 2016 32 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Rakowska et al. 2016 49 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Amer et al. 2017 33 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Jha et al. 2017 50 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Khunkhet et al. 2017 54 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Moneib et al. 2017 34 | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| Al‐Refu 2018 13 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Köse 2018 39 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Dias et al. 2018 35 | *** | *** | ** | 8 |

| Mahmoudi et al. 2018 36 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Mani et al. 2018 37 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Bhandary et al. 2019 38 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Waśkiel‐Burnat et al. 2019 51 | *** | *** | ** | 8 |

| Bains and Kaur 2020 40 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Darkase et al. 2020 41 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Fatima et al. 2020 42 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Fukuyama et al. 2020 52 | *** | *** | ** | 8 |

| Govindarajulu et al. 2020 43 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Vyshak et al. 2020 44 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

| Waśkiel‐Burnat et al. 2020 56 | *** | *** | ** | 8 |

| Vijay et al. 2021 45 | **** | *** | ** | 9 |

2.7. Risk of bias (quality) assessment

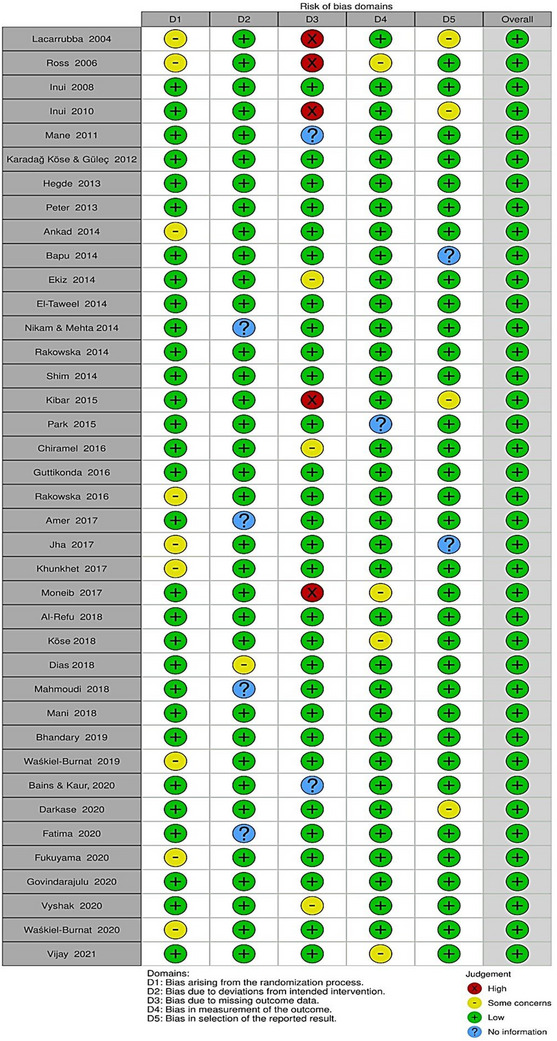

Two review authors (MD and AI) independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias using the approach recommended by Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials. The Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool updates the original risk of bias tool. The tool is divided into five categories that can introduce bias into the outcome: bias resulting from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions; bias due to missing outcome data; bias in the measurement of the outcome; and bias in the selection of the reported result. Each component of the risk of bias tool in the included studies will be classified into "Low" or "High" risk of bias or express "Some concerns." 17 Disagreements will be resolved by discussing them with the review team (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Assessment risk of bias using (RoB 2).

2.8. Statistical analysis

2.8.1. Assessment of heterogeneity

The “meta” package and “metabin” function of the open‐source statistical program “R 4.0.3″” 18 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used to conduct the meta‐analysis and subgroup analysis. Utilizing Cochrane Q and I2, the heterogeneity of the studies included in the meta‐analysis was evaluated. Cochrane Q with p < 0.001 and I 2 > 50% suggested that the included studies were heterogeneous. 19 If there was no substantial heterogeneity between trials, the fixed‐effect model (Mantel–Haenszel technique) was utilized for analysis. The random‐effects model was applied in all other cases. The yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and tapering hairs were calculated using the pooled odd ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

2.8.2. Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Meta‐regression analysis was performed using factors that may affect the prevalence of trichoscopic on AA, such as study sample size, year of publication, study NOS quality score, information about yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and tapering hairs.

2.8.3. Assessment of reporting bias

Egger's test and a funnel plot were used to assess publication bias if sufficient studies were included. A two‐sided p value was considered statistically significant if it was <0.05.

2.8.4. Dealing with missing data

We tried to analyze the available data. If the article data are missing, we try to contact the corresponding authors by email to request missing data (e.g., when an article is identified as an abstract only). If we are unable to collect reliable data, we may evaluate how the article could affect the data that we do have. If something cannot be examined, the study will be excluded.

2.9. Ethics and dissemination

The ethics committee approved the systematic review and meta‐analysis at Shaqra University, Dawadmi Faculty of Medicine (ERC_SU 20220002). The study's findings will be reported according to the PRISMA‐compliant guidelines and submitted to a peer‐reviewed journal for publication.

2.10. Patient and public involvement

This protocol will not involve any patient or the public.

3. RESULTS

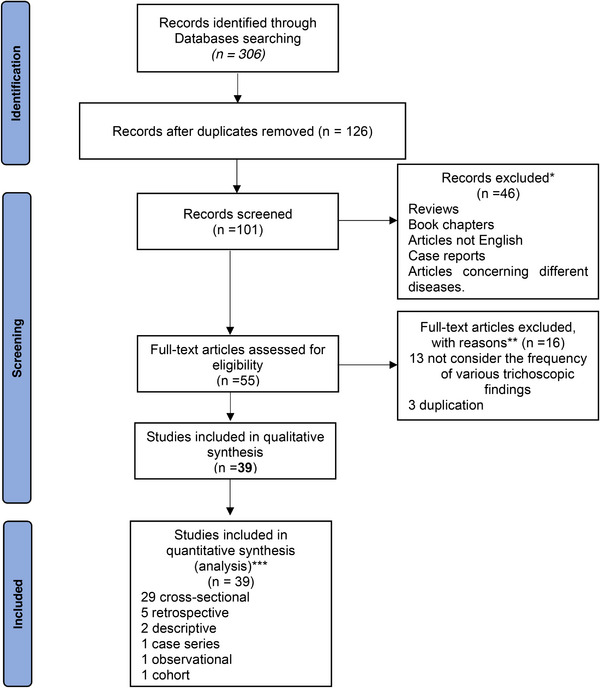

Thirty‐nine studies enrolling 3204 patients with AA were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review and meta‐analysis (Figure 2). The amount of gathered trichoscopic features in our study are as follows: yellow dots (n = 1910), black dots (n = 1638), broken hairs (n = 1297), short vellus hairs (n = 1623), and tapering hairs (n = 1252) (Table 3). As for included study designs, there were 29 cross‐sectional, 13 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 five retrospective 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , two descriptive, 53 , 54 one case series, 55 one observational, 14 and one cohort study. 56 As for the continental distribution of these studies, 10 studies were conducted in Europe 14 , 23 , 26 , 29 , 39 , 46 , 48 , 49 , 51 , 56 ; three studies were conducted in Africa 27 , 33 , 34 ; and 26 studies were conducted in Asia. 13 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 50 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 There were 30 studies conducted on adults, 14 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 while six studies were conducted on children, 13 , 26 , 27 , 33 , 34 , 49 and three studies were conducted on both adults and children. 46 , 50 , 51

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA flow diagram.

TABLE 3.

Most common trichoscopic features in alopecia areata in our study.

| Trichoscopic feature | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Yellow dots | 1910 |

| Black dots | 1638 |

| Broken hairs | 1297 |

| Short vellus hairs | 1623 |

| Tapering hairs | 1252 |

The types of AA and correlations with the most common trichoscopic features are summarized (Tables 4 and 5).

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of included studies in systematic review and meta‐analysis of most common trichoscopic features in alopecia areata.

| No. | References | Year | Continent | Sample size | Patients | Research design | Type of alopecia areata | Yellow dots | Black dots | Broken hairs | Short vellus hairs | Tapering hairs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lacarrubba et al. 14 | 2004 | Europe | 200 | Adult | Observational | Patchy, localized (120), Totalis (49), Universalis (31) | – | – | – | (38) 27.1% | (62) 44.3% |

| 2 | Ross et al. 48 | 2006 | Europe | 58 | Adult | Retrospective | Patchy (39) | (37) 94.9% | – | – | – | – |

| Ophiasis (10) | (9) 90% | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Diffuse (1) | (1) 100% | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Totalis/universalis (8) | (8) 100% | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| 3 | Inui et al. 20 | 2008 | Asia | 300 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy, localized (25) | (15) 60% | (7) 28% | (13) 52% | (21) 84% | (6) 24% |

| Patchy, multiple (115) | (66) 57.4% | (56) 48.7% | (46) 40% | (91) 79.1% | (46) 40% | |||||||

| Diffuse (57) | (34) 59.6% | (23) 40.4% | (22) 38.6% | (45) 78.9% | (16) 28.1% | |||||||

| Ophiasis (15) | (11) 73.4% | (4) 26.7% | (9) 60% | (5) 33.3% | (8) 53.5% | |||||||

| Totalis (51) | (36) 70.6% | (24) 47.1% | (19) 37.3% | (39) 76.5% | (10) 19.6% | |||||||

| Universalis (37) | (29) 78.4% | (19) 51.4% | (14) 37.8% | (17) 45.9% | (9) 24.3% | |||||||

| 4 | Inui et al. 21 | 2010 | Asia | 100 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy, localized (13), Patchy, multiple (52), Diffuse (21), Ophiasis (14) | – | (48) 48% | – | (83) 83% | (33) 33% |

| 5 | Mane et al. 22 | 2011 | Asia | 66 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy, localized (24) | (17) 70.8% | (17) 70.8% | (14) 58.3% | (8) 33.3% | (3) 12% |

| Patchy, multiple (33) | (28) 84.8% | (22) (66.7) | (19) 57.6% | (16) 48.5% | (4) 12.1% | |||||||

| Diffuse (5) | (5) 100% | (2) 40% | (2) 40% | (1) 20% | (1) 20% | |||||||

| Ophiasis (2) | (2) 100% | (2) 100% | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | 0 | |||||||

| Universalis (2) | (2) 100% | (1) 50% | 0 | (1) 50% | 0 | |||||||

| 6 | Karadağ Köse and Güleç 23 | 2012 | Europe | 49 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy, localized and multiple (49) | (41) 83.7% | (31) 63.3% | (28) 57.1% | (23) 46.9% | (21) 42.9% |

| 7 | Hegde et al. 24 | 2013 | Asia | 75 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy, localized (29) | (11) 37.9% | (24) 82.8% | (11) 37.9% | (20) 69% | (5) 17.2% |

| Patchy, multiple (26) | (16) 61.5% | (21) 85.8% | (9) 34.6% | (16) 61.5% | (4) 15.4% | |||||||

| Reticulate (2) | (1) 50% | (1) 100% | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | |||||||

| Diffuse (3) | (3) 100% | (3) 100% | (1) 33.3% | (1) 33.3% | 0 | |||||||

| Ophiasis (9) | (7) 77.8% | (9) 100% | (4) 44.4% | (8) 88.9% | (2) 22.2% | |||||||

| Sisaphio (3) | (2) 66.7% | (3) 100% | (1) 33.3% | (3) 100% | (1) 33.3% | |||||||

| Totalis (1) | (1) 100% | (1) 100% | 0 | (1) 100% | 0 | |||||||

| Universalis (2) | (2) 100% | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | |||||||

| 8 | Peter et al. 25 | 2013 | Asia | 57 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy (localized, multiple) (43) | (18) 42% | (30) 69.8% | (29) 67.4 | (25) 53.5% | (15) 34.9% |

| Diffuse (1) | (1) 100% | (1) 100% | 0 | (1) 100% | 0 | |||||||

| Ophiasis (6) | 0 | (6) 100% | (3) 50% | (4) 66.7% | (1) 16.7% | |||||||

| Totalis, universalis (7) | (5) 71.4% | (6) 85.7 % | (6) 85.7% | (4) 57.1% | (3) 42.8% | |||||||

| 9 | Ankad et al. 55 | 2014 | Asia | 50 | Adult | Case series | Patchy, localized (25), Patchy, multiple (23), Totalis (2) | (25) 50% | (10) 20% | (15) 30% | (5) 10% | (30) 60% |

| 10 | Bapu et al. 53 | 2014 | Asia | 116 | Adult | Descriptive | Patchy, localized (76) | (66) 86.8% | (22) 28.9% | (8) 10.5% | (48) 63.2% | (14) 18.4% |

| Patchy, multiple (26) | (25) 96.2% | (9) 34.6% | (4) 15.4% | (14) 53.8% | (8) 30.8% | |||||||

| Diffuse (3) | (2) 66.7% | (1) 33.3% | 0 | (2) 100% | 0 | |||||||

| Ophiasis (5) | (5) 100% | (2) 40% | (2) 40% | (3) 60% | 0 | |||||||

| Totalis (3) | (3) 100% | (1) 33.3% | 0 | (3) 100% | (1) 33.3% | |||||||

| Universalis (3) | (3) 100% | (1) 33.3% | (1) 33.3% | (1) 33.3% | 0 | |||||||

| 11 | Ekiz et al. 26 | 2014 | Europe | 10 | Child | Cross‐sectional | Patchy (10) | (10) 100% | – | – | (5) 50% | (4) 40% |

| 12 | El‐Taweel et al. 27 | 2014 | Africa | 20 | Child | Cross‐sectional | Patchy (localized, multiple) (20) | (11) 55% | (12) 60% | (8) 40% | (8) 40% | (11) 55% |

| 13 | Nikam and Mehta 47 | 2014 | Asia | 32 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy (32) | (2) 6.25% | (23) 71.9% | (19) 59.3% | (11) 34.4% | (6) 18.8% |

| 14 | Rakowska et al. 46 | 2014 | Europe | 314 | Child Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy (localized, multiple) (314) | (207) 65.9% | (167) 53.2% | (212) 67.5% | (167) 53.2% | (254) 80.9% |

| 15 | Shim et al. 28 | 2014 | Asia | 81 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy, localized (81) | (50) 61.7% | (34) 42% | (2) 2.5% | (39) 48.1% | (32) 39.5% |

| 16 | Kibar et al. 29 | 2015 | Europe | 39 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy, localized (7), Patchy, multiple (21), Sisaipho (4), Totalis (2), Universalis (5) | (27) 69.2% | (26) 66.7% | (22) 56.4% | (20) 51.3% | (24) 61.5% |

| 17 | Park et al. 30 | 2015 | Asia | 167 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Localized AA (117): Patchy (108), Ophiasis (9) | (65) 55.6% | (87) 74.4% | (69) 59% | (70) 59.8% | (48) 41% |

| Diffuse AA (50): Diffuse (20), Incognita (7), Totalis, Universalis (23) | (28) 56% | (43) 86% | (31) 62% | (34) 68% | (21) 42% | |||||||

| 18 | Chiramel et al. 31 | 2016 | Asia | 24 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy (24) | (21) 87.5% | (19) 79.2% | – | (12) 50% | (17) 70.8% |

| 19 | Guttikonda et al. 32 | 2016 | Asia | 50 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy (42), Reticulate (3), Ophiasis (3), Diffuse (2) | (44) 88% | (29) 58% | (28) 56% | (33) 66% | (13) 26% |

| 20 | Rakowska et al. 49 | 2016 | Europe | 102 | Child | Retrospective | Patchy (102) | (37) 36.3% | (43) 42.2% | (5) 4.9% | (20) 19.6% | (37) 36.3% |

| 21 | Amer et al. 33 | 2017 | Africa | 20 | Child | Cross‐sectional | Patchy AA (20) | (12) 60% | (15) 75% | (5) 25% | (8) 40% | (9) 45% |

| 22 | Jha et al. 50 | 2017 | Asia | 72 |

Child Adult |

Retrospective | Patchy, localized (21), Patchy, multiple (29), Ophiasis (5), Sisiapho (3), Totalis (9), Universalis (5) | (57) 79.2% | (51) 70.8% | (31) 43.1% | (32) 44.4% | (23) 31.9% |

| 23 | Khunkhet et al. 54 | 2017 | Asia | 52 | Adult | Descriptive | Patchy AA (52) | (24) 46.2% | (40) 76.9% | (31) 59.6% | (18) 34.6% | (31) 59.6% |

| 24 | Moneib et al. 34 | 2017 | Africa | 34 | Child | Cross‐sectional | Patchy, localized and multiple (30), Totalis (3), Universalis (1) | (31) 91.2% | (20) 58.8% | – | (32) 94.1% | (15) 44.1% |

| 25 | Al‐Refu 13 | 2018 | Asia | 38 | Child | Cross‐sectional | Patchy AA (38) | (26) 68.4% | (24) 63.2% | (21) 55.3% | (12) 31.6% | (17) 44.7% |

| 26 | Köse 39 | 2018 | Europe | 38 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Beard: Patchy, localized (13), Patchy, multiple (22), Total beard (3) | (10) 26.3% | (7) 18.4% | (13) 34.2% | (20) 52.6% | (8) 21.1% |

| 27 | Dias et al. 35 | 2018 | Asia | 67 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | S1 (43), S2 (7), S3 (6), S4 (3), S5 (8) | (58) 86.6% | (46) 68.7% | (40) 59.7% | (33) 49.3% | (17) 25.4% |

| 28 | Mahmoudi et al. 36 | 2018 | Asia | 126 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy localized (14) | (6) 42.9% | (9) 64.3% | (2) 14.3% | (10) 71.4% | (4)28.6% |

| Patchy multiple (29) | (21) 72.4% | (10) 34.5% | (4) 13.8 | (21) 72.4% | (14) 48.3% | |||||||

| Ophiasis (6) | (6) 100% | (4) 66.7% | (2) 33.3% | (4) 66.7% | (6) 100% | |||||||

| Totalis (16) | (12) 75% | (4) 25% | (2) 12.5% | (12) 100% | (10) 62.5% | |||||||

| Universalis (61) | (59) 96.7% | (35) 57.4% | (2) 3.3% | (30) 49.2% | (5) 8.2% | |||||||

| 29 | Mani et al. 37 | 2018 | Asia | 21 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy localized (4) | (1) 25% | (3) 75% | (3) 75% | (3) 75% | (2) 50% |

| Patchy multiple (12) | (6) 50% | (11) 91.7% | (9) 75% | (10) 83.3% | (8) 66.7% | |||||||

| Ophiasis (1) | 0 | 0 | (1) 100% | (1) 100% | 0 | |||||||

| Sisiapho (1) | (1) 100% | (1) 100% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Totalis (2) | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | (1) 50% | 0 | |||||||

| Universalis (1) | (1) 100% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| 30 | Bhandary et al. 38 | 2019 | Asia | 46 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Beard: Patchy localized (17), Patchy multiple (29) | (13) 28.2% | (18) 39.1% | (9) 19.6% | (18) 39.1% | (14) 30.4% |

| 31 | Waśkiel‐Burnat et al. 51 | 2019 | Europe | 100 |

Child Adult |

Retrospective | Children: S1 (19), S2 (7), S3 (5), S4 (4), S5 (14) | (26) 52% | (20) 40% | (27) 54% | (35) 70% | (22) 44% |

| Adult: S1 (19), S2 (7), S3 (5), S4 (4), S5 (14) | (48) 96% | (26) 52% | (27) 54% | (37) 74% | (24) 48% | |||||||

| 32 | Bains and Kaur 40 | 2020 | Asia | 52 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy localized (9) | (2) 22.2% | (7) 77.8% | (7) 77.8 % | (4) 44.4% | (4) 44.4% |

| Patchy multiple (28) | (17) 60.7% | (25) 89.3% | (24) 85.7% | (15) 53.6% | (6) 21.4% | |||||||

| Ophiasis (5) | (3) 60% | (5) 100% | (3) 60% | (4) 80% | (3) 60% | |||||||

| Totalis (4) | (4) 100% | (3) 75% | (1) 25% | (3) 75% | 0 | |||||||

| Universalis (6) | (6) 100% | (3) 50% | (1) 16.7% | (4) 66.7% | (1) 16.7% | |||||||

| 33 | Darkase et al. 41 | 2020 | Asia | 100 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy localized or multiple (100) | (59) 59% | (75) 75% | (46) 46% | (49) 49% | (26) 26% |

| 34 | Fatima et al. 42 | 2020 | Asia | 50 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Circumscripta/ localized (49), Totalis (1) | (42) 84% | (37) 74% | (18) 36% | (24) 48% | (6) 12% |

| 35 | Fukuyama et al. 52 | 2020 | Asia | 58 | Adult | Retrospective | sADTA (18) | (8) 44.4% | (12) 66.7% | (11) 61.1% | (18) 100% | (4) 22.2% |

| RP‐AA (40) | (16) 40% | (31) 77.5 % | (32) 80% | (4) 10% | (10) 25% | |||||||

| 36 | Govindarajulu et al. 43 | 2020 | Asia | 35 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy (35) | (21) 60% | (31) 88.6% | (33) 94.3% | (13) 37.1% | (28) 80% |

| 37 | Vyshak et al. 44 | 2020 | Asia | 60 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy localized (27), Patchy multiple (23), Ophiasis (4), Diffuse (1), Universalis (5) | (30) 50% | (38) 63.3% | (8) 13.3% | (27) 45% | (21) 35% |

| 38 | Waśkiel‐Burnat et al. 56 | 2020 | Europe | 65 | Adult | Cohort | S1 (31), S2 (9), S3 (13), S4 (12), S5 (0) | (55) 84.6% | (40) 61.5% | (50) 76.9% | (52) 80% | (42) 64.6% |

| 39 | Vijay et al. 45 | 2021 | Asia | 260 | Adult | Cross‐sectional | Patchy localized (135), Patchy multiple (70), Diffuse (25), Ophiasis (12), Totalis (10), Universalis (8) | (189) 72.7% | (95) 36.5% | (154) 59.2% | (160) 61.5% | (100) 38.5% |

S ADTA: self‐healing acute diffuse and total alopecia.

PR‐AA: rapidly‐progressive subtype of AA.

TABLE 5.

Most common trichoscopic features in alopecia areata and their correlations.

| Trichoscopic feature | Clinical appearance | Pathology | Associated diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow dots | Round or polycyclic yellow to yellow‐pink dots | Dilated infundibula plugged with sebum and keratin remnants |

|

| Black dots | Black dots inside follicular openings | Broken hairs shaft |

|

| Tapering hairs | Tapered hairs with dark ends | Telogen hairs with a broken tip |

|

| Broken hairs | Fragments of pigmented hair shafts | Fracture of dystrophic hair shafts or rapid regrowth of hairs |

|

| Short vellus hairs | Regrowing short white hair | Thin, nonpigmented hairs may demonstrate early disease remission |

|

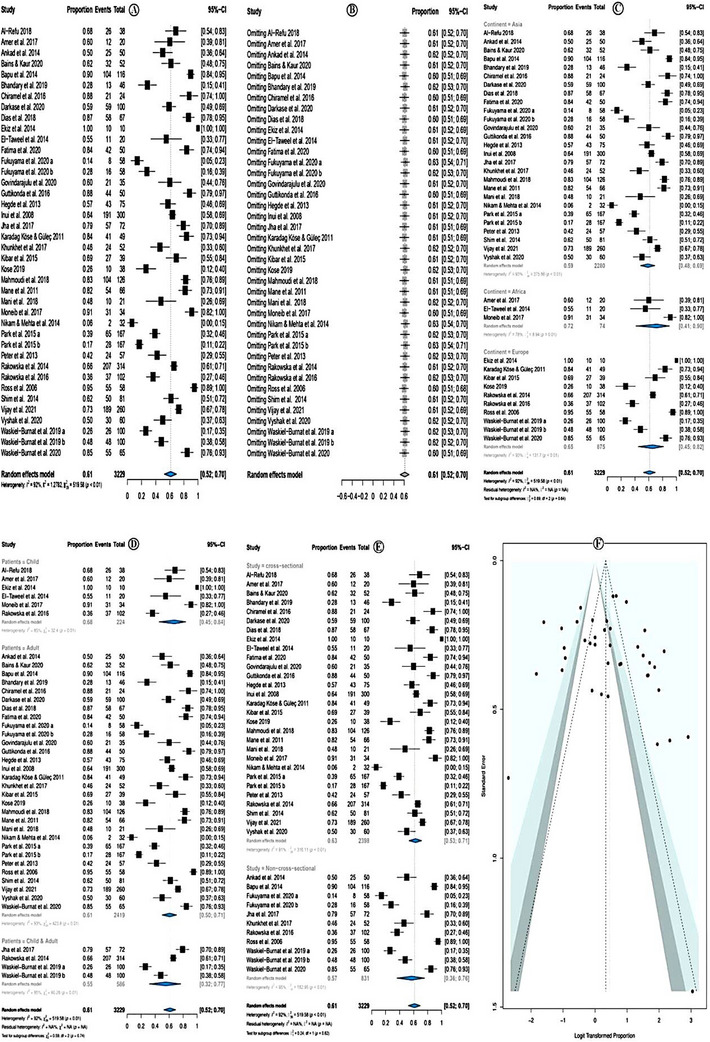

4. PREVALENCE OF YELLOW DOTS

The overall pooled prevalence of yellow dots was 61.0% (95% CI = 52.0−70.0%; p < 0.01) (Figure 3A). The random effect model was used due to high heterogeneity (I 2 = 92.0%). Sensitivity analysis revealed that none of the studies significantly affected the overall estimate. Therefore, none of the studies was deleted (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of yellow dots.

In subgroup analysis according to the study continent, the highest yellow dots prevalence was among African studies (prevalence = 72.0%; 95% CI = 41.0–90.0 %; p = 0.01), followed by European countries, and the least in Asian studies. However, the subgroup differences were insignificant (p = 0.64) (Figure 3C). Subgroup analysis according to the study patients' category showed that the prevalence of yellow dots was higher in studies that investigated children only (prevalence = 68%; 95% CI = 45–84%, p < 0.01) followed by studies that investigated both children and adults and the least in studies that investigated adults only (Figure 3D).

Subgroup analysis according to the study design category showed that the prevalence of yellow dots was higher in cross‐sectional studies (prevalence = 63%; 95% CI = 53–71%, p < 0.01) followed by non‐cross‐sectional studies (Figure 3E). The meta‐regression model showed no significant association with the following assessed variables: year of publication, quality of the studies, location of the studies, sample size, and types of studies (Table 6). There was no evidence of publication bias either in the forest plot (Figure 3F) or in Egger test (p = 0.529).

TABLE 6.

Meta‐regression analysis of the most common trichoscopic finding factors in alopecia areata.

| Yellow dots | Black dots | Broken hairs | Short vellus hairs | Tapering hairs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Coefficient (95.0 % CI) | p | Coefficient (95.0 % CI) | p | Coefficient (95.0 % CI) | p | Coefficient (95.0 % CI) | p | Coefficient (95.0 % CI) | p |

| Year of publication | −0.1056 | 0.0599 | 0.0692 | 0.1174 | 0.0232 | 0.7338 | −0.0142 | 0.6904 | −0.0118 | 0.7486 |

| Study quality score | 0.3002 | 0.1996 | 0.0706 | 0.7020 | 0.1488 | 0.5549 | 0.0373 | 0.8212 | 0.0961 | 0.5516 |

| Study continent | ||||||||||

| •Asia | 0.1072 | 0.8941 | 0.3246 | 0.6122 | 0.7899 | 0.4291 | −0.3710 | 0.5179 | −0.4154 | 0.4570 |

| •Europe | 0.3517 | 0.7006 | −0.5598 | 0.4479 | 0.8302 | 0.4542 | −0.4672 | 0.4830 | −0.0920 | 0.8863 |

| Study sample size | −0.0028 | 0.4618 | −0.0060 | 0.0216* | −0.0033 | 0.3600 | 0.0014 | 0.4974 | −0.0028 | 0.2148 |

| Study design | ||||||||||

| • Non‐cross‐sectional | −0.2701 | 0.5490 | −0.8093 | 0.0267* | −0.4733 | 0.3327 | −0.9618 | 0.0019** | −0.0923 | 0.7693 |

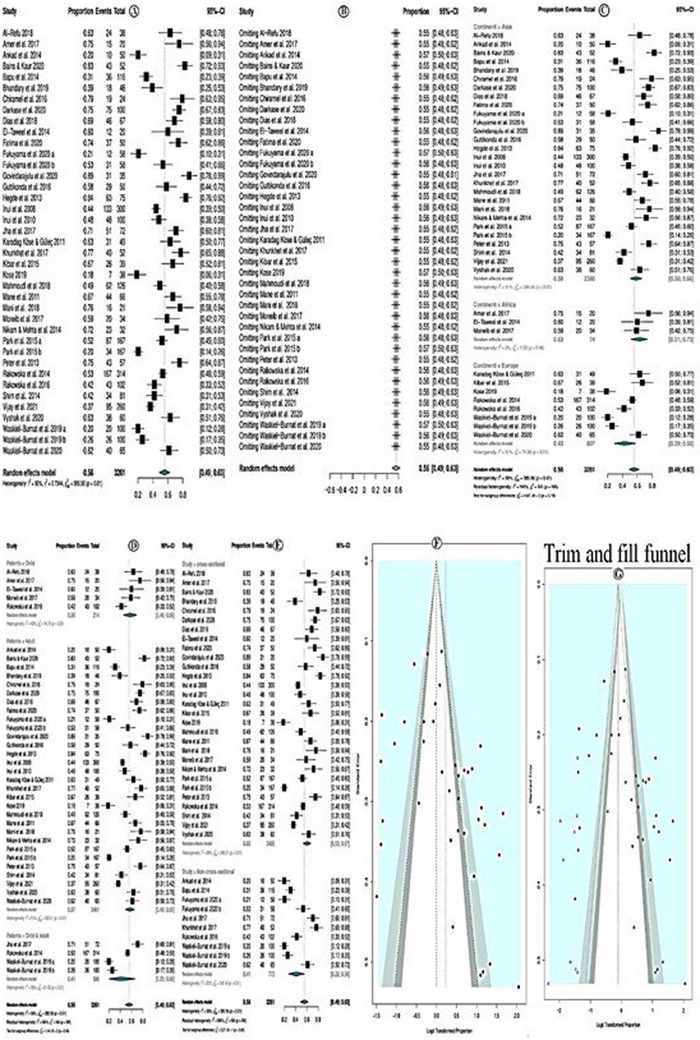

5. PREVALENCE OF BLACK DOTS

The overall pooled prevalence of black dots was 56.0% (95% CI = 49.0−63.0%; p < 0.01) (Figure 4A). The random effect model was used due to high heterogeneity (I 2 = 90.0%). According to the sensitivity analysis, none of the studies had a significant individual effect on the overall estimate; therefore, no study was deleted (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Prevalence of black dots.

In subgroup analysis according to study continent, the highest black dots prevalence was among studies conducted in Africa (prevalence = 63.0%; 95% CI = 51.0–73.0 %; p = 0.46), followed by Asian countries, and the least is in European studies. Yet, the subgroup differences were not significant (p = 0.10; Figure 4C). Subgroup analysis according to the study patients' category showed that the prevalence of black dots was higher in studies that investigated children only (prevalence = 58%; 95% CI = 46–69%, p = 0.03) followed by studies that investigated both children and adults and the least was in studies that investigated adults only (Figure 4D). Subgroup analysis, according to the study design, showed that the prevalence of black dots was higher in cross‐sectional studies (prevalence = 60%; 95% CI = 53−67%, p < 0.01) followed by non‐cross‐sectional studies (Figure 4E). The meta‐regression model showed that study sample size (coefficient = −0.006; p = 0.021) and non‐cross‐sectional study design (coefficient = −0.809; p = 0.026) were only associated with the prevalence of black dots. While other assessed variables, year of publication, quality of the studies, and locations of the studies were not (Table 6). The funnel plot showed an asymmetry pattern that indicates publication bias (Figure 4F). Egger test p = 0.015 further confirms this; trim and fill methods were applied, and more than nine new studies were added to correct the funnel plot asymmetry (Figure 4G). The new estimated prevalence was 47.4% (95% CI 39.7–55.1%); I 2 = 91.6%.

6. PREVALENCE OF BROKEN HAIRS

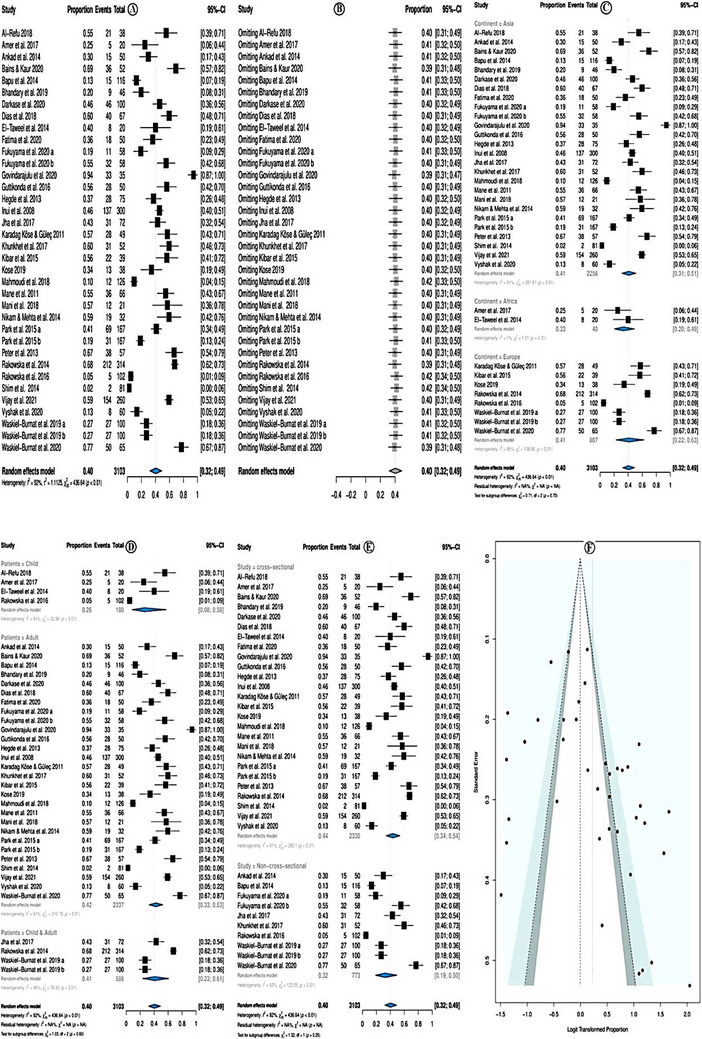

The overall pooled prevalence of broken hairs was 40.0% (95% CI = 32.0−49.0%; p < 0.01) (Figure 5A). The random effect model was used due to high heterogeneity (I 2 = 92.0%). Sensitivity analysis revealed that none of the studies significantly affected the overall estimate. Therefore, none of the studies was deleted (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Prevalence of broken hairs.

In subgroup analysis according to study continent, the broken hairs prevalence was higher among studies conducted in Asia (prevalence = 41.0%; 95% CI = 31.0 – 51.0 %; p < 0.01), followed by European countries, and the least in African studies. Yet, the subgroup differences were not significant (p = 0.70; Figure 5C). Subgroup analysis according to the study patients' category showed that the prevalence of broken hairs was higher in studies that investigated adults only (prevalence = 42%; 95% CI = 33–53%, p < 0.01) followed by studies that investigated both children and adults and the least studied that investigated children only, (Figure 5D). Subgroup analysis according to the study category showed that the prevalence of broken hairs was higher in cross‐sectional studies (prevalence = 44%; 95% CI = 34–54%, p < 0.01) followed by non‐cross‐sectional studies (Figure 5E). The meta‐regression model showed no significant association with the assessed variables: year of publication, quality of the studies, location of the studies, sample size, and types of studies (Table 6). There was no evidence of publication bias either in the forest plot (Figure 5F) or in Egger test p = 0.056.

7. PREVALENCE OF SHORT VELLUS HAIRS

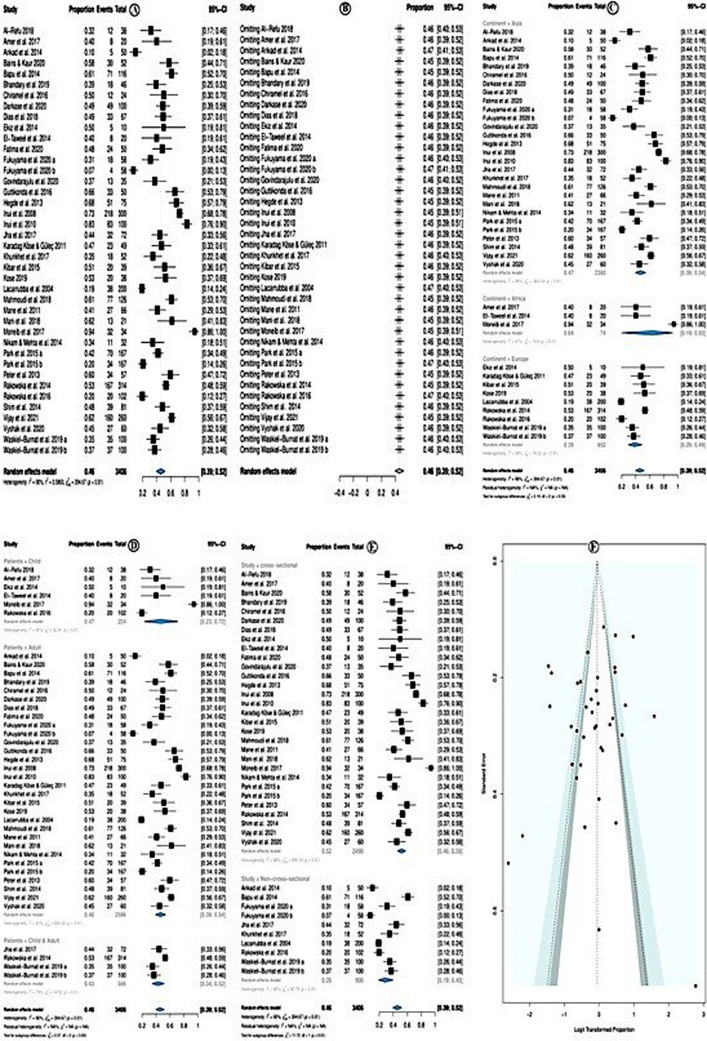

The overall pooled prevalence of short vellus hairs was 46.0% (95% CI = 39.0−52.0%; p < 0.01) (Figure 6A). The random effect model was used due to high heterogeneity (I 2 = 90.0%). Sensitivity analysis revealed that none of the studies significantly affected the overall estimate. Therefore, none of the studies were deleted (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Prevalence of short vellus hairs.

In subgroup analysis according to study continent, the short vellus hairs prevalence was higher among studies conducted in Africa (prevalence = 74.0%; 95% CI = 19.0−93.0 %; p < 0.01), this is followed by Asian countries and the least among European studies. Yet, the subgroup differences were not significant (p = 0.33; Figure 6C). Subgroup analysis according to the study patients' category showed that the prevalence of short vellus hairs was higher in studies investigated children only (prevalence = 47%; 95% CI = 23–72%, p < 0.01), followed by studies investigated in adults only. At the same time, the least studied investigated adults and children only (Figure 6D). Subgroup analysis, according to the study design, showed that the prevalence of short vellus hairs was higher in cross‐sectional studies (prevalence = 52%; 95% CI = 46–58%, p < 0.01) followed by non‐cross‐sectional studies (Figure 6E). The meta‐regression model showed that only the cross‐sectional design significantly decreased the prevalence of the short vellus hairs (coefficient = −0.961; p = 0.0019), while other assessed variables: year of publication, the quality of the studies, location of the studies, and sample size all showed no significant association (Table 6). There was no evidence of publication bias, neither in the forest plot (Figure 6F) nor in Egger test p = 0.353.

8. PREVALENCE OF TAPERING HAIRS

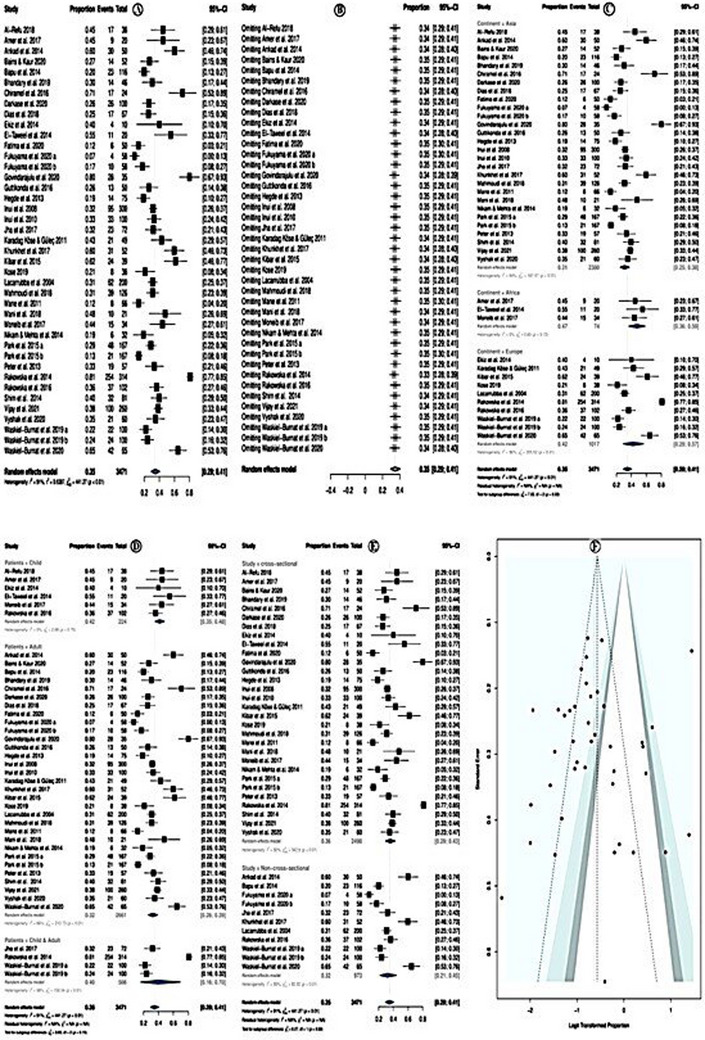

The overall pooled prevalence of tapering hairs was 35.0% (95% CI = 29.0−41.0%; p < 0.01) (Figure 7A). The random effect model was used due to high heterogeneity (I 2 = 91.0%). Sensitivity analysis revealed that none of the studies significantly affected the overall estimate. Therefore, none of the studies were deleted (Figure 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Prevalence of tapering hairs.

In a subgroup analysis according to study continent, the tapering hairs prevalence was higher among studies conducted in Africa (prevalence = 47.0%; 95% CI = 36.0−59.0%; p = 0.72), followed by European countries, and the least in Asian studies. Yet, the subgroup differences were not significant (p = 0.03; Figure 7C). Subgroup analysis according to the study patients' category showed that the prevalence of tapering hairs was higher in studies investigated children only (prevalence = 42%; 95% CI = 35–48%; p = 0.70) followed by studies investigated in adults only and the least in studies investigated in both adults and children only, (Figure 7D). Subgroup analysis, according to the study designs, showed that the prevalence of tapering hairs was higher in cross‐sectional studies (prevalence = 36%; 95% CI = 29–43%, p < 0.01) followed by non‐cross‐sectional studies (Figure 7E). The meta‐regression model showed no significant association with the assessed variables: year of publication, the quality of the studies, location of the studies, sample size, and types of studies (Table 6). There was no evidence of publication bias, neither in the forest plot (Figure 7F) nor in Egger test p = 0.375.

9. TRICHOSCOPIC SIGNS AND PATTERNS

Classification of trichoscopic structures according to location helps dermatologists familiarize themselves with signs and patterns of hair and scalp disorders. In this regard, trichoscopic features can be grouped as follows57:

follicular;

peri‐ and interfollicular;

vascular;

hair shaft.

In AA, the most common trichoscopic features are regularly distributed yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and tapering hairs. The disease activity, severity, and duration can all affect the trichoscopic findings. In recent years, many researchers have investigated these variations. 58

10. MOST COMMON TRICHOSCOPIC FINDINGS IN AA

10.1. | Yellow dots

Yellow dots are the most common trichoscopic feature in AA initially proposed by Ross et al. 48 and are also considered the most sensitive trichoscopic feature of AA. Yellow dots correspond to follicular infundibula filled with sebum and/or keratotic material and are better visualized with polarized light. 48

Yellow dots are present as round or polycyclic yellow to yellow‐pink dots devoid of hair or contain miniaturized, cadaverized, or dystrophic hair. The degenerating follicular keratinocytes probably constitute the yellow dot bulk. 59 Yellow dots likely represent the distention of the affected follicular infundibulum with keratinous material and sebum, “degreasing” an affected area with acetone results in diminished dot size. 48 Yellow dots are characterized by an abundant amount and regular distribution. 20

Fitzpatrick skin type III and IV of Asian population is thought to have the lower incidence of yellow dots. However, in a study by Mane et al. 22 on an Indian population, skin Fitzpatrick type V showed a higher incidence of yellow dots. While findings of the study done by Peter et al. 25 on an Indian population with Fitzpatrick type V showed that the detection of yellow dots was challenging as they merged with the color of the scalp. The differences in frequency are postulated to be due to different skin phototypes. Another possible reason may be shampooing habits among the European, Asian, and Latin American populations. Also, different devices have been used, like handheld dermoscopy, videodermoscopy, or trichoscopy. 7

Yellow dots are sparsely seen in children with AA; it is hypothesized that yellow dots are not present because of the underdevelopment of sebaceous glands before puberty. 59 However, Bapu et al. 53 reported a high prevalence of yellow dots in dermoscopy among dark‐skinned patients with AA up to 15 years of age. It might be attributed to a regional custom of rubbing oil on scalp lesions that resemble yellow dots. 53 Tosti and Duque‐Estrada 60 both reported on this.

It is also important to note that yellow dots in youngsters tended to be more egg‐yolk in hue. On the other hand, adults were likelier to notice the yellow‐brown hues of the yellow dots. The composition of age‐related sebum may have an impact on the hue of the yellow dots. Yellow dots in adults are related to keratotic material and sebum, whereas they are associated with keratotic material in youngsters. 61

Yellow dots represent a good indicator of AA and positively correlate to the disease activity and severity, which is intern classified from S1 to S5 B2 according to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation guidelines. Also, yellow dots and/or short vellus hairs enhance the sensitivity of the diagnosis of AA. Even while yellow dots are thought to be the most sensitive, other hair diseases such as androgenetic alopecia, alopecia incognito, dissecting cellulitis, and trichotillomania can also have the same finding. Therefore, they are not a reliable diagnostic indicator for AA. However, in these cases, the number of yellow dots is limited, while in AA, numerous yellow dots were detected. 20

In combination with short vellus hairs, yellow dots provide sensitive clues for diagnosing AA, especially universalis and diffuse types, but not for monitoring disease activity. 20 This strong correlation between yellow dots and universalis type seems to be sense, given that yellow dots and scalp severity are connected. On the other hand, the connection between short vellus hairs and alopecia universalis is debatable at first look because short vellus hairs often signify hair regeneration. The considerable link between short vellus hairs and cases of alopecia universalis that have undergone therapy, however, leads one to believe that this correlation may be the result of treatment use. 36

According to Waśkiel‐Burnat et al., 51 the most prevalent and sensitive trichoscopic findings in children with AA were unfilled follicular holes. Additionally, compared with adults, they were found in youngsters far more frequently. This could be because empty follicular openings (those devoid of sebum and/or keratotic material) are more commonly seen because yellow dots are less likely to be seen. 51

10.2. | Black dots

Black dots, also called cadaverized hairs, are defined as hair in which the upper part of the hair root remains adherent to the hair‐follicle ostium due to a broken hairs shaft at the scalp skin surface level, giving the macroscopic appearance of a macrocomedo. 48

Black dots have never been used to diagnose AA in white populations. This difference may be attributed not only to hair color but also to cuticle resistance. Black dots are remnants of exclamation mark hair or broken pigmented hair seen in trichoscopy. Also, black dots correlated positively with the severity and activity of AA and are considered a specific diagnostic marker of AA. 20

Black dots appear in all patients with acute AA and can also be seen in acute dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. This has been explained by the presence of an acute inflammatory process that might cause their development. Furthermore, black dots were consistently seen in patients with hypotrichosis simplex, a chronic disease with genetic background. 62

Inui et al. 20 reported that black dots, yellow dots, and short vellus hairs are all useful severity markers of AA. Although black dots were a characteristic marker for AA, this finding was also seen in some cases of trichotillomania, tinea capitis, and dissecting cellulitis. 59

Ross et al. 48 considered both black dots and tapering hairs as strong characteristics, so‐called ‘stigma’ signs of AA. On the contrary, Kowalska‐Oledzka et al. 25 do not support the presence of black dots as a specific AA feature.

10.3. | Broken hair

There are two different ways in which AA can form broken hairs. One option is a transverse fracture of terminal hair shafts caused by the inflammatory process. In certain situations, monilethrix‐like hairs (Pohl‐Pinkus constriction) or trichorrhexis nodosa may appear before hair breaking. The other option is that the hair shafts that once made up the black patches are rapidly growing again after being partially damaged. In contrast to trichotillomania, which causes every broken hair to be in a different length, AA often causes hair to break at the same level above the skin surface. 58

Broken hairs were numerous in AA and, to a lesser extent, in tinea capitis and trichotillomania. 47

Broken hairs represent a specific diagnostic marker of AA and are a clinical marker of disease activity and severity. 20

10.4. | Short vellus hairs

Short vellus hairs result from hair regrowth either spontaneously or due to treatment. The nonscarring feature of AA can be demonstrated by the ability of the trichoscope to identify short vellus hairs, even if they are invisible to the naked eye. Trichoscopy can identify the short, pigmented vellus hairs; however, white vellus hairs are more recognizable. Short vellus hairs are adversely correlated with the severity or activity of the AA. Patients may be motivated to continue their therapy by this discovery from follow‐up visits. Asian patients pigmented complexion makes vellus hairs easier to see. 20

Following treatment, including steroid pulse therapy, short vellus hairs can return, even if the regained hairs are hardly visible to the naked eye. 63 When the documented initial regrowth occurs and during the treatment, it may or may not be clinically recognizable as brand‐new, thin, and unpigmented hairs inside the patch. These vellus hairs, as well as the turning of vellus hairs into terminal hairs, which appears as an increase in the thickness and color of the proximal hair shaft, are both indicative of the remission stage and hence of the effectiveness of treatment. 64

Lacarrubba et al. described two patterns of hair regrowth in some patients with chronic AA: the first was homogenous and indicated early disease remission (upright vellus hair); the second was sparse, thin, and twisted vellus hair (pigtail hair regrowth), which were typically lost after a few weeks. 14

Dias et al. 35 found a correlation between short vellus hairs and lower SALT scores (Severity of Alopecia Tool). However, they did not find any significant association between the other trichoscopic features of AA and SALT score. 35

10.5. | Tapering hairs

Tapering hairs correspond clinically to exclamation mark hair, which could be observed with the naked eye, resulting from a truncated hair cycle consisting of premature telogen and dystrophic anagen characterized by a broader diameter in the distal shaft and thinner diameter in the proximal shaft. Because the damaged hairs often do not have an exclamation mark form, the term tapering hairs is preferable over exclamation mark hairs. It happens due to the hair shafts shortening toward the follicles, which are easier to see with trichoscopy than with the naked eye. 20

These patterns mark the presence of the lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate affecting the hair bulb, resulting in the reduction (no cessation) of mitotic activity, thus producing a thinner hair shaft and hence fractured and short. Short‐term repetition of this inflammatory process results in Pohl‐Pinkus constrictions (zones of reduced hair thickness within the hair shaft). 65

These indicate an active disease process and are more commonly seen in the lesion's periphery. 20 Tapering hairs are observed in most active AA cases; however, they are not specific to AA as they may be seen in trichotillomania. 66

Yellow dots and short vellus hairs were the most sensitive indicators in an investigation of 300 AA patients by Inui et al. 20 In contrast, black dots, tapering hairs, and broken hairs were the most specific signs for diagnosis. 20 Other studies found a positive correlation between tapering hairs and disease severity. 20 , 29

11. OTHER COMMON TRICHOSCOPIC FINDINGS IN AA

11.1. Coudability hairs

Coudability hairs are normal‐looking hairs that can be made to kink easily when bent or pushed inward follicles in the perilesional hair‐bearing scalp described by Shuster. 67

Coudability hairs look very similar to tapering hairs; the proximal hair shaft is narrowing, but they are not broken at their distal end. 68 Although coudability hairs are visible to the naked eye, trichoscopy makes it much easier to identify them, giving clinicians a strong tool to track the progression of AA. 21

The analysis done by Inui et al. 21 defined the coudability score based on the number of coudability hairs; (score 1) = 1–3 coudability hairs; (score 2) = 4–9 coudability hairs; (score 3) = ≥ 10 coudability hairs. They found that the coudability score correlated positively with the disease activity but not with the severity of AA. Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the score and hair‐pull tests, short illness duration, black spots, and tapering hairs, but a negative correlation with short vellus hairs. The therapeutic importance of coudability hairs as a relevant trichoscopic characteristic of AA should thus be recognized. 21

Inui et al. 21 also discovered a substantial correlation between coudability and tapering hairs. A shared pathomechanism of coudability and tapering hairs is reflected by the early transition from anagen to catagen, which causes hair shaft constriction at the follicles. According to the morphology, a few black dots may also be the remains of coudability hairs. They can come first before black dots and tapering hairs because coudability is more likely to emerge in seemingly unbroken hairs of average length. 21

Other studies found that the coudability score correlates with AA disease activity. 44 , 47 , 55 In comparison, other studies found that the coudability score did not correlate with the disease activity of AA. 29 , 53 Bains and Kaur 40 found that the coudability score correlates with AA disease severity.

11.2. Honeycomb pigmentation

A grid and holes characterize a pigment network known as honeycomb pigmentation. The holes in the epidermis represent the dermal papillae's dermal papilla tips, and the grid symbolizes the hyperchromic melanocytes in rete ridges. 69 Honeycomb pigment comprises contiguous brown rings seen in sun‐exposed areas of thinning or complete hair loss and in the sun‐exposed scalp with type IV skin. 48

Due to prolonged sun exposure to bald areas, this pattern is typically seen in advanced androgenic alopecia and the normal scalp. 66

The appearance of this pattern in alopecia totalis can be explained based on excessive sunlight exposure resulting from total baldness of the scalp in alopecia totalis. 55

Given that it is mostly present in alopecia diseases that might be permanent or slowly progressing, the honeycomb pigment seems to be a sign of chronic illness. 48

11.3. White dots

Small hypopigmented spots that resemble white dots can be seen. They are positioned consistently and serve as eccrine duct apertures. These should not be confused with the white specks in lichen planopilaris sparing interfollicular epidermis that reflect damaged follicles replaced by fibrous tracks. 69 The coalescence of white dots results in areas appearing like cotton wool patterns. 55 White dots are always associated with honeycomb pigmentation. 48

de Moura et al. 70 observed the regular distribution of white dots among hair follicles and empty follicular units in AA patients with dark skin phototypes. Even though the research's participants had a dark complexion, Kibar et al. 29 observed intersecting white dots in a nested pattern that was not seen in the de Moura et al. 70 investigation. They were known as clustered white dots because the traditional, erratic white dots were stacked with pinpoint white dots, 29 similar to cumulus clouds. 71

Kibar et al. 29 found that white dots were related to severe AA, with honeycomb pigmentation seen in AA and alopecia totalis/alopecia universalis and sisaipho. Its concordance with disease severity and honeycomb pigmentation forced us to consider that long‐standing AA has a much greater scarring process than we had previously known. That cumulative sun damage makes these dots more visible with honeycomb pigmentation. 29

11.4. Tapered hairs

Long exclamation mark hairs with a narrower proximal end are best described as tapered hairs; the distal end is not visible during a trichoscopy. 7 They develop from inflammatory injury to hair follicles in the late anagen phase and have little mitotic activity. 65 , 72

The inflammatory process reduces mitotic activity (no cessation); hair follicles can still produce a thin hair shaft if this inflammatory process is repeated in short periods. 65 They occur at the early stages of AA and precede the emergence of black dots and tapering hairs. 21

Like tapering hairs, tapered hairs are considered pathognomonic for AA. 21 , 23 , 30 However, they are also observed in patients with trichotillomania, 46 , 54 malnutrition, and chronic intoxication. 68

11.5. Pigtail hairs (circle hairs)

Pigtail hairs, also known as circle hairs, are short, regrowing, regularly coiled hairs with tapered ends that resemble a pig's tail. 68 They indicate hair regrowth after successful treatment or spontaneous disease remission. 14

Waśkiel‐Burnat et al. 51 hypothesized that the higher incidence of pigtail hairs in children might be associated with more extensive hair regrowth and more common spontaneous remissions.

Waśkiel‐Burnat et al. 56 consider pigtail hairs have a role in the therapeutic monitoring of AA; thus, pigtail hairs are considered a positive predictive factor for hair regrowth in AA.

Pigtail hairs have also been seen in trichotillomania, tinea capitis, chemotherapy‐induced alopecia, and triangular temporal alopecia. 73 Additionally, there are solitary pigtail hairs at the cicatricial alopecia's hair‐bearing edge. 58

11.6. Zigzag hairs

Angulated hair is a novel term that defines broken hairs, independent of the location of the fracture, generating an acute angle along the hair shaft. A small percentage of people with AA exhibit zigzag or corkscrew hairs, which are hairs with repeatedly acute angles. 54

In addition to AA and trichorrhexis nodosa, other hair diseases with a localized weakening of the hair shaft can also exhibit zigzag hairs; however, these have often been associated with tinea capitis. 58

About one‐fourth of AA patients exhibited strongly angled hairs, according to Khunkhet et al. 54 However, almost all of these hairs had just one sharp angle towards the proximal end and did not have the usual zigzag look (more than one sharp angle). To avoid miscommunication, they used “checkmark hair” (only one sharp angle) for this trichoscopic appearance. They hypothesize that these angulated hairs share a common causative mechanism; weakening the hair shaft caused by peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate. Also, angulated hairs were reported to be the most specific feature for differentiation between AA and trichotillomania. 54

Rudnicka et al. 58 first noted the trichoscopic finding that resembles checkmark hair in AA and referred to it as trichoclasis, a transverse fracture across the hair shaft with an unbroken cuticle. Similar to this, Karadağ Köse and Güleç 23 also noted angled hairs and termed trichorrhexis nodosa.

11.7. Tulip hairs

Tulip hairs vary from exclamation mark hairs in that they contain light‐colored hair shafts with just a dark distal end and are only somewhat thinned at the proximal end. The dark distal end correlates to a region of heightened pigmentation that has the appearance of tulip‐shaped leaves. 58

According to Rudnicka et al., 58 the area of oblique hair rupture correlates to this darker part of the hair shaft. These sparse hairs are seen in trichotillomania and AA.

11.8. Upright regrowing hairs

New, healthy, regrowing hairs with a tapering distal end and a straight‐up orientation are known as upright regrowing hairs. They must be distinguished from short vellus hairs. 68 Rakowska et al. 73 hypothesized that the higher frequency of upright regrowing hairs observed in children might result from more extensive hair regrowth.

Upright regrowing hairs were observed in AA and acute telogen effluvium, trichotillomania, tinea capitis, and temporal triangular alopecia. 7

11.9. Pohl‐Pinkus constrictions

Zones of less dense hair are referred to as “Pohl‐Pinkus constrictions” inside the hair shaft. These constrictions happen when an internal or external cause abruptly and repeatedly suppresses a follicle's metabolic and mitotic activity. Because they resemble real monilethrix, hairs with numerous Pohl‐Pinkus constrictions should be distinguished. 68 People with active hair loss are more likely to get Pohl‐Pinkus constrictions. 7

Pohl‐Pinkus constrictions were observed in AA but also in chemotherapy‐induced alopecia, cicatricial alopecia, following severe general infections, after major blood loss, severe blood loss, nutrient deficiencies, and localized hereditary hypotrichosis. 7

12. OTHER TRICHOSCOPIC FINDINGS IN AA

Here, we review other occasionally reported trichoscopic findings in AA.

12.1. Follicular features

In the pediatric age group, it was described by studies were done by Park et al., 30 Waśkiel‐Burnat et al., 51 and Vyshak et al. 44 that empty follicles were the most common and sensitive trichoscopic findings in AA.

12.2. Perifollicular features

Perifollicular erythema was reported by Shim et al., 28 while Park et al. 30 also added the findings of perifollicular pustules/vesicles, perifollicular scales, and peripilar sign in AA.

12.3. Interfollicular features

Arborizing red lines, which are the papillary loops and the underlying vascular plexus, were described in several studies; however, they can also be seen on the normal scalp, particularly in the temporal and occipital areas. 23 , 29 , 30 , 39 , 43 , 44 , 48

Ross et al. 48 and Park et al. 30 displayed a simple red loop that can also be found on a normal scalp, especially in the temporal and occipital regions, representing the papillary loops and the underlying vascular plexus. Also, Shim et al. 28 and Kibar et al. 29 demonstrated atypical red vessels in AA patients.

Additionally, Karadağ Köse and Güleç, 23 Park et al., 30 and Köse 39 showed red dots, which are erythematous, polycyclic, concentric structures regularly distributed in and around the follicular ostia. They also showed how probable imitations of black dots, called filthy dots, were reported on the scalps of healthy youngsters. They are little, black dust particles of varying sizes that vanish after washing. 23 , 30 , 39

In contrast, Nikam and Mehta 47 showed red dots in polarized mode. Kibar et al. 29 represented brown dots as yellow dots, which became brown in color.

Bains and Kaur, 40 Park et al., 30 and Köse 39 reported perifollicular scaling, while Nikam and Mehta 47 revealed this finding in polarized mode. Karadağ Köse and Güleç 23 and Park et al. 30 reported crust formation in AA. Also, Park et al. 30 illustrated the flakes scale, while Nikam and Mehta 47 showed the flakes scale in polarized mode.

Some studies have prescribed telangiectasia as an interfollicular pattern for AA. 30 , 40 , 41

12.4. Hair shaft features

Several studies have described trichoptilosis (split ends) in AA, a longitudinal splitting of the hair shaft into two or more fibrils, a common finding in patients with long hairs. 30 , 33 , 45 , 46 , 54

Regardless of the number of fracture sites, Khunkhet et al. 54 and Fawzy et al. 74 demonstrated angulated hairs in AA as a unique word referring to the broken hairs generating acute angles along the hair shaft.

Rakowska et al. 46 , 49 and Khunkhet et al. 54 demonstrated the v‐sign in AA in which two hairs emerge from one follicular opening that breaks at an equal level. Also, they reported partial coiling of the distal part of fractured hairs results in a hook‐like appearance. 46 , 49 , 54

Researchers also describe many other patterns, and others have not because they are rare and have no significance. These patterns appear more in other diseases, such as trichotillomania, tinea capitis, traction alopecia, telogen effluvium, androgenic alopecia, and other diseases.

13. CORRELATION BETWEEN VARIOUS TRICHOSCOPIC FINDINGS IN AA

13.1. Trichoscopic findings as an indicator of the activity of AA

Disease activity was defined by the global estimation of scalp hairs and evaluated for each patient. 20 Disease activity was determined based on the patient's personal history of disease development and the objective assessment of the hair pull test at the edges of each patch. 32 As given by Inui et al., 20 disease activity is classified as remitting, stable, or progressive as follows: progressive AA, an increase in total hair loss of more than 5%; stable AA, a change in total hair loss of less than 5%; remitting AA, a decrease in total hair loss of more than 5% over the month before presentation. They reported that black dots, broken hairs, tapering hairs, and short vellus hairs indicate disease activity in AA. 20 In comparison, Kibar et al. 29 reported tapering hairs as a marker of disease activity in AA. In addition, Vijay et al. 45 reported that yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs positively correlate with disease activity in AA.

Other studies reported that black dots and broken hairs indicate disease activity in AA. 13 , 44 , 50 While in other studies reported that black dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs indicate disease activity in AA. 32 , 55 On the other hand, No correlation was found between various trichoscopic findings and disease activity in other studies. 22 , 36 , 53

13.2. Trichoscopic findings as severity markers of AA

The severity of AA is assessed by SALT and graded according to the guidelines of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation as follows: S0, no hair loss; S1, less than 25% hair loss; S2, 26−50% hair loss; S3, 51−75% hair loss; S4, 76−99% hair loss; and S5, 100% hair loss (alopecia totalis). While the body hair loss score is as follows: B0, no body hair loss; B1, some body hair loss; B2, 100% body hair loss; S5B2 (alopecia universalis). 75 The rank test used the Spearman rank‐order correlation coefficient to assess if the dermoscopic results were statistically associated with the AA degree. Therefore, severity markers determined by trichoscopy may be useful in predicting disease course. 20 The severity of hair loss is considered an important prognostic factor. 8

Inui et al. 20 reported that black and yellow dots correlated positively with the severity of AA. Similarly, Ganjoo and Thappa 76 reported that yellow dots, black dots, and broken hairs correlate positively with the severity of AA. Also, Ankad et al. 55 reported that black dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs correlated positively with the severity of AA. Bains and Kaur 40 reported that yellow dots and broken hairs correlated positively with the severity of AA. Mahmoudi et al. 36 consider yellow dots correlated positively with the severity of AA. Darkase et al. 41 reported that black dots and broken hairs correlated positively with the severity of AA. Vijay et al. 45 reported that broken hairs and tapering hairs correlated positively with the severity of AA.

Other studies considered black dots to be correlated positively with the severity of AA. 27 , 29 In contrast, other studies did not correlate various trichoscopic findings and disease severity. 22 , 25 , 32 , 35 , 53

13.3. Trichoscopic findings as sensitive diagnostic markers of AA

Initially, it was proposed by Ross et al. 48 that yellow dots are considered to be the most sensitive dermoscopic feature of AA. This was supported by Inui et al. 20 findings, who reported that yellow dots and short vellus hairs provided sensitive clues to diagnose AA. Consecutively, other additional studies reported the same.. 23 , 32 , 35 , 47 , 50 , 53

Fawzy et al. 74 reported that black dots were the most accurate diagnostic indicators for AA; this may be because dark‐skinned people (Egyptian, Turkish, and Indian) have the highest incidence of black dots, and their study was restricted to Egyptian patients. 74

El‐Taweel et al. 27 discovered that tapering hairs were a more sensitive and diagnostic trichoscopic feature of AA when associated with yellow dots and short vellus hairs. In contrast, black dots, according to Amer et al., 33 are the most frequent trichoscopic finding and can be utilized as a sensitive feature of AA if combined with other distinct features like yellow dots, tapering hairs, or short vellus hairs.

Al‐Refu 13 reported that microexclamation marks were frequently observed near the edge of the lesion in cases with active AA. It was said to be more sensitive and diagnostic when linked with yellow spots, black dots, or short vellus hairs.

In contrast, Khunkhet et al. 54 found no correlation between various trichoscopic findings as sensitive diagnostic markers of AA.

13.4. Trichoscopic findings as specific diagnostic markers of AA

Other causes of alopecia including tinea capitis, trichotillomania, androgenetic alopecia (male or female), telogen effluvium, frontal fibrosing alopecia, lichen planopilaris, folliculitis decalvans were examined to measure the specificity of the trichoscopic findings characteristic of AA. 20

Ross et al. 48 considered black dots and tapering hairs strongly characteristic, so‐called "stigma" signs of AA. Similarly, Inui et al. 20 reported that black dots, tapering hairs, and broken hairs were the most specific diagnostic markers of AA.

According to Tosti and Duque‐Estrada, 60 yellow dots are specific for AA in 95% of Europeans and 60% of Asians and differ depending on skin type. Bapu et al. 53 also found yellow dots to be specific dermoscopic markers for AA. Also, El‐Taweel et al. 27 show that yellow dots, tapering hairs, and short vellus hairs are diagnostic for AA. Karadağ Köse and Güleç 23 found that tapering hairs are a specific diagnostic feature for AA. Interestingly, Kowalska‐Oledzka et al. 62 showed that black dots were not specific for AA. Furthermore, Kiber et al. 29 found that the other trichoscopic findings, coudability hairs, black dotted pigmentation, and cumulus‐like clustered white dots were specific markers for AA in addition to previous findings. In the same context, Park et al. 30 found that proximal tapering and exclamation mark hair are considered the most specific diagnostic features of AA in the differential diagnosis of diffuse alopecia.

Chiramel et al. 31 found that black dots, tapering hairs, and broken hairs were the most specific diagnostic markers of AA. Amer et al. 33 reported that yellow dots, tapering hairs, and short vellus hairs are all specific to AA.

Al‐Refu 13 found that yellow dots, tapering hairs, and short vellus hairs are specific to AA. Govindarajulu et al. 43 found that the most specific markers for AA were black dots, tapering hairs, and broken hairs.

Vyshak et al. 44 suggested that microexclamation marks are a specific marker of an active state of AA.

13.5. Trichoscopic findings as monitoring treatment efficacy of AA

Trichoscopy has an important role in monitoring the response to treatment in AA. As observed by Ganzetti et al., 77 there was a statistically significant reduction of AA hallmarks, tapering hairs, black dots, yellow dots, and broken hairs, while there was an increase in the number of short vellus hairs with new vessels in patients treated with diphenylcyclopropenone.

Ganjoo and Thappa 76 mentioned that short vellus hairs increased in alopecic patients treated with intralesional steroid injections. Furthermore, they also noted a loss of tapering hairs, broken hairs, and black dots in patients who responded to the treatment. Contrariwise, yellow dots were the least responsive to the treatment. This finding can be used to encourage patients to continue treatment. Moreover, trichoscopy can identify areas showing early atrophy and/or telangiectasia in the treated patients with intralesional steroid injection; subsequently, reinjections in the same site can be avoided. 76

Hegde et al. 24 noted an increased incidence of short vellus hairs in patients who had received some form of treatment (75%) versus untreated patients (51.6%).

Furthermore, Kibar et al. 29 found that five out of six patients who had local ultraviolet A phototherapy with methoxypsoralen gel and minoxidil 5% spray solution showed a change in the proximal region of their hair follicle, which seemed to be covered with a whitish‐grey veil without scaling. The authors interpreted this as a local side effect of these topical preparations on the scalp, specifically epidermal proliferative and augmentative side effects. 29

El Taieb et al. 78 noted an increased number of short vellus hairs in patients of AA treated with a 5% minoxidil solution. Moreover, short vellus hairs were reduced in patients treated with platelet‐rich plasma, while more fully pigmented hair was increased. They added that these two treatment methods were more effective than the placebo. 78

On the other side, a study conducted by Jha et al., 50 where patients were treated with intralesional steroids, found an increase in the number of terminal hairs and short vellus hairs; this is in addition to the finding of peripilar sign. However, Elmaadawi et al. 79 mention a decrease in the number of short vellus hairs (75%; 17 out of 20) in treated patients with stem cell therapy compared with untreated patients (85%, 18/20), as well as the appearance of regrowing hair (95%, 19 out of 20). Mahmoudi et al. 36 reported that yellow dots significantly increased in patients who received diphenylcyclopropenone.

Waśkiel‐Burnat et al. 56 identified the following therapeutic outcomes at a 2‐month follow‐up of patients with patchy AA, two positive predictive markers (upright regrowing hairs, and pigtail hairs) and four negative predictive markers (black dots, broken hairs, tapering hairs, and tapered hairs). Additionally, they noted no statistically significant difference in the frequency of short vellus hairs between responders and nonresponders at follow‐up. Thus, short vellus hairs may not be a predictive factor for the therapeutic outcome in patchy AA. 56

Fawzy et al. 74 showed a decreased number of broken hairs, tapering hairs, and tapered hairs in both groups treated with intralesional corticosteroids or platelet‐rich plasma. In addition, black dots were the most sensitive to treatment, while yellow dots and vellus hairs did not show a significant change in the evaluation of treatment in either group. Also, they found that upright regrowing hairs were slightly better detected with intralesional corticosteroids than with platelet‐rich plasma. In contrast, pigtail hairs were better seen with platelet‐rich plasma than with intralesional corticosteroids. 74

14. DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta‐analysis were conducted to systematize current knowledge about the clinical usefulness of trichoscopic features in AA. This analysis revealed the five most characteristic trichoscopic features in AA: yellow dots (61%), black dots (56%), broken hairs (40%), short vellus hairs (46%), and tapering hairs (35%).

Yellow dots, short vellus hairs, and broken hairs have the highest calculated positive predictive value (100, 100, and 94.3%, respectively). Thus, their presence is highly indicative of AA. According to these observations, trichoscopy may help establish the primary diagnosis of AA to start the therapy. Moreover, it may be helpful to perform screening in high‐risk populations.

Yellow dots and short vellus hairs provide the most sensitive clues to AA, while black dots and tapering hairs were strong specific diagnostic markers of AA. The present review confirmed that trichoscopy is a valuable method in differentiating between AA and other scalp diseases, which is essential for deciding different therapeutic approaches.

The literature has also described the role of trichoscopy in monitoring the therapy of AA. 24 , 29 , 36 , 50 , 56 , 74 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 The trichoscopic clue of treatment efficacy is represented in an increase in short vellus hairs and loss of tapering hairs, broken hairs, and black dots in patients who responded to the treatment, while yellow dots were the least responsive to the treatment. Finally, the current study analyzed trichoscopic features that may help monitor AA treatment.

Through a trichoscopy, invasive diagnostic procedures like scalp biopsies might not be necessary. However, a trichoscopy‐guided biopsy may be done in dubious instances. 80

Other trichoscopic features: coudability hairs, honeycomb pigmentation, white dots, tapered hairs, pigtail hairs (circle hairs), zigzag hairs, tulip hairs, upright regrowing hairs, Pohl‐Pinkus constrictions, empty follicles, red dots, dirty dots, brown dots, perifollicular scaling, monilethrix, angulated hairs, v‐sign were all observed in AA. These characteristics were uncommon from the overall analysis of all currently existing data. Consequently, it was excluded from the quantitative study. Future differential diagnoses for hair loss may consider some of these characteristics. 81

This systematic review and meta‐analysis also collected information on trichoscopic findings of AA in places other than the scalp: including beard, mustache, eyebrows, eyelashes, and limbs. Trichoscopic findings such as yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and tapering hairs were slightly less similar to findings noted in scalp AA. This observation could be related to a shorter hair cycle in locations other than the scalp. Only a small portion of anagen follicles in AA experience an inflammatory process due to the short anagen period. As a result, during a trichoscopic inspection, these distinguishing characteristics may not always be evident. 38 , 39 , 82

15. CONCLUSION

The five most characteristic trichoscopic findings in AA are: yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and tapering hairs. The diagnosis is not based on single trichoscopic finding rather than a constellation of characteristic findings. Yellow dots and short vellus hairs considered the most sensitive clues for AA, while black dots and tapering hairs are the most specific ones. Furthermore, Trichoscopy is a useful tool that allows monitoring of response during the treatment of AA. In patients who responded to the treatment, there are an increase in short vellus hairs, but loss of tapering hairs, broken hairs, and black dots, while yellow dots are the least responsive to the treatment. Thus, and with skillful hands, trichoscopy provides the characteristic feature of AA that is sufficient to establish the diagnosis with further monitoring of treatment response.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

FUNDING

This study received funding from the Ethical Research Committee of Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia (protocol code IFP2021‐058, Feb. 24, 2022).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through project number IFP2021‐058.

Al‐Dhubaibi MS, Alsenaid A, Alhetheli G, Abd Elneam AI. Trichoscopy pattern in alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29:1–27. 10.1111/srt.13378

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fukuyama M, Ito T, Ohyama M. Alopecia areata: current understanding of the pathophysiology and update on therapeutic approaches, featuring the Japanese Dermatological Association guidelines. J Dermatol. 2022;49(1):19‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hordinsky M, Junqueira AL. Alopecia areata update. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015;34(2):72‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: Disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caldwell CC, Saikaly SK, Dellavalle RP, Solomon JA. Prevalence of pediatric alopecia areata among 572,617 dermatology patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(5):980‐981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alkhalifah A. Alopecia areata update. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(1):93‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hunt N, McHALE S. Reported experiences of persons with alopecia areata. J Loss Trauma. 2004;10(1):33‐50. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Waśkiel A, Rakowska A, Sikora M, Olszewska M, Rudnicka L. Trichoscopy of alopecia areata: an update. J Dermatol. 2018;45(6):692‐700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tosti A, Bellavista S, Iorizzo M. Alopecia areata: a long term follow‐up study of 191 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):438‐441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lew BL, Shin MK, Sim WY. Acute diffuse and total alopecia: a new subtype of alopecia areata with a favorable prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(1):85‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]