Abstract

Improving yield is one of the most important targets of sesame breeding. Identifying quantitative trait loci (QTLs) of yield-related traits is a prerequisite for marker-assisted selection (MAS) and QTL/gene cloning. In this study, a BC1 population was developed and genotyped with the specific-locus amplified fragment (SLAF) sequencing technology, and a high-density genetic map was constructed. The map consisted of 13 linkage groups, contained 3528 SLAF markers, and covered a total of 1312.52 cM genetic distance, with an average distance of 0.37 cM between adjacent markers. Based on the map, 46 significant QTLs were identified for seven yield-related traits across three environments. These QTLs distributed on 11 linkage groups, each explaining 2.34–71.41% of the phenotypic variation. Of the QTLs, 23 were stable QTLs that were detected in more than one environment, and 20 were major QTLs that explained more than 10% of the corresponding phenotypic variation in at least one environment. Favorable alleles of 38 QTLs originated from the locally adapted variety, Yuzhi 4; the exotic germplasm line, BS, contributed favorable alleles to only 8 QTLs. The results should provide useful information for future molecular breeding and functional gene cloning.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11032-021-01236-x.

Keywords: Sesamum indicum L., Genetic map, QTL, Yield-related traits

Introduction

Sesame, one of the oldest domesticated oilseed crops, is mainly cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (Bedigian and Harlan 1986; Ashri 2007). Sesame seed is regarded as “the queen of oil seeds” and one of the best health foods because of the high quality of its oil and its nutritive value (Ashri 1998; Namiki 2007). However, sesame production and expansion are hindered by low yield, seed shattering, and great demand for manual labor. There is an urgent need to develop new cultivars with high yield potential, resistance, or tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses and enhanced agronomic traits adapted to mechanized harvesting (Mei et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2019).

Improving yield is one of the most important targets of sesame breeding, while it is a time-consuming and low efficient process, because it involves multiple complex and environmentally sensitive components (Slafer 2003; Wu et al. 2014; Gadri et al. 2020). Integrating conventional breeding methods with molecular approaches has proven to be an efficient way of enhancing yield (Xu and Crouch 2008; Jannink et al. 2010; Guo et al. 2019). Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for agronomically important traits are prerequisites for marker-assisted selection (MAS), and a large number of QTLs have been identified in major crops through linkage mapping and/or association mapping strategies (Morrell et al. 2012; Würschum 2012). Because sesame is an orphan or neglected crop, genetic dissection of traits has long been hindered by the lack of molecular markers and genomic information (Wei et al. 2009; Dossa 2016). With the release of two physical maps of sesame (Zhang et al. 2013a; Wang et al. 2014), the past 7 years have witnessed extensive progress in genetic and genomic studies in this crop. Several studies have been successfully performed to identify QTLs/genes for breeding objective traits (Zhang et al. 2013b; Zhao et al. 2013; Wei et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2015b; Zhang et al. 2016; Mei et al. 2017b; Wang et al. 2017a; Zhang et al. 2018; Wei et al. 2019; He et al. 2019; Dossa et al. 2019; Miao et al. 2020), including yield-related traits (Wu et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2018; Du et al. 2019). However, compared with model plants and major crops, the identification of QTLs in sesame is still limited. Therefore, more effort should be put into QTL mapping to meet the requirements of molecular breeding.

In this study, we developed a BC1 population from a cross between a locally adapted elite cultivar (Yuzhi 4) and an exotic germplasm line (BS) and genotyped it using the SLAF sequencing method to construct a high-density genetic linkage map and detect QTLs for yield-related traits across multiple environments. The findings should provide useful information for future molecular breeding programs and functional gene cloning studies in sesame.

Materials and methods

Mapping population and marker identification

Previously, we developed a BC1 population from a cross between a locally adapted variety Yuzhi 4 and an exotic germplasm line BS, genotyped 150 BC1 plants with specific-locus amplified fragment sequencing (SLAF-seq), and constructed a high-density genetic map with 9378 SLAF markers developed by clustering of sequence similarity (Mei et al. 2017). In this study, the BC1 plants were self-pollinated to develop 150 BC1F2 families for trait evaluation instead of the BC1 individuals in multiple field trials. To facilitate comparison of marker and QTL information across studies, the SLAF markers were identified with a reference genome. Briefly, the sesame genome assembly Zhongzhi No. 13 version 1.0 (Wang et al. 2014) was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/11560?genome_assembly_id=49670) database. We aligned the pair-end reads from the 150 BC1 plants and their parents with the reference genome using the BWA software (Li and Durbin 2009). Sequences mapped to the same genomic position were defined as one SLAF marker, and alleles of each SLAF locus were identified according to parental reads. SLAF markers with two to four alleles were identified as polymorphic and assorted into eight segregation patterns (i.e., ab × cd, ef × eg, hk × hk, lm × ll, nn × np, aa × bb, ab × cc, and cc × ab), and those markers with the aa × bb pattern were used for further linkage analyses (Sun et al. 2013).

Phenotype data collection and analyses

The field trials were performed in three environments in the summer of 2018: Pingyu Experimental Station (N32° 59′, E114° 42′; hereafter “Pingyu”) of Henan Sesame Research Center, Experimental Station of Nanyang Academy of Agricultural Sciences (N32° 54′, E112° 24′; hereafter “Nanyang”), and Experimental Station of Luohe Academy of Agricultural Sciences (N33° 37′, E113° 58′; hereafter “Luohe”). A randomized complete block design with two replications was used at all locations. Each plot included a single 3.5 m row with a 17-cm plant-to-plant distance and a 40-cm row-to-row distance. Sowing was from late May to early June at different locations. Ten uniform plants from the middle of each row were tagged for trait measurement. Seven agronomic and yield-related traits—plant height (PH; cm), height of the first capsule (FCH; cm), number of capsules per plant (CN), number of seeds per capsule (SN), 1000-seed weight (SW; g), seed yield per plant (SY; g), and aboveground biomass yield per plant (BY; g)—were measured at maturity and after harvesting. SN was the mean value of the number of seeds from 30 capsules, and SW was the mean weight of three independent samples of 1000 seeds. Other traits were mean values from 10 plants. The harvest index (HI; %) was calculated as the ratio of SY to BY.

Statistical analyses of all phenotypic data across the three environments were performed with SAS 8.0. Analyses of variance of all phenotypic data were performed based on the trait means of each family across the three environments with PROC GLM:

and the broad-sense heritability (h2) was estimated for each trait according to the following formula:

where , , , , and are variances of phenotype, genotype, environment, genotype by environment interaction, and stochastic error, respectively; e is the number of environments; and r is the number of replicates in each environment.

Genetic map construction and QTL mapping

The genetic map was constructed with JoinMap 3.0 (Van Ooijen 2006). Markers with excessively distorted segregation ratios (χ2 test, P < 0.01) were excluded. Because the number of pseudo-molecules of Zhongzhi No. 13 genome version 1.0 is 16, which is three more than the number of chromosomes in sesame (n = 13), we determined the LGs using a minimum limit of detection (LOD) value of 5.0 and a maximum recombination of 45%. The regression mapping algorithm was used, with a LOD threshold of 3.0, to determine the order of markers on each LG. A ripple was performed after the addition of each locus, with goodness-of-fit jump threshold for removal loci = 5.0 and third round = Yes. The Kosambi mapping function was used to translate recombination frequencies into map distances.

QTL mapping was performed using IciMapping 4.1 (Meng et al. 2015) with the inclusive composite interval mapping additive model (Li et al. 2007), and the significant LOD threshold was determined with 1000 permutations (P = 0.05). The QTL nomenclature was adopted from the method developed in rice (McCouch et al. 1997). QTLs that were consistently identified in at least two environments with similar genomic positions (within 5 cM) and same additive effect directions were considered stable QTLs and assigned the same name. QTLs that explained more than 10% of phenotypic variation (PV) in at least one environment were considered major QTLs. The linkage map and QTLs were visualized graphically with MapChart 2.3 (Voorrips 2002).

Results

SLAF markers identified with the reference genome

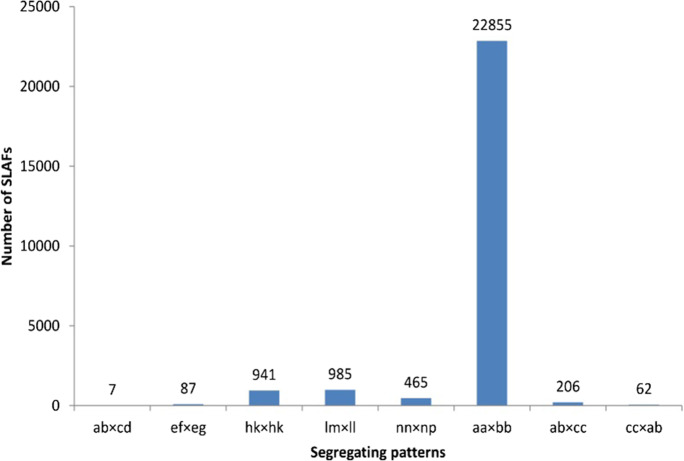

We mapped the 355.78 M 100 bp pair-end reads onto 16 pseudo-molecules and 16,444 unanchored scaffolds of Zhongzhi No. 13 genome version 1.0 (Wang et al. 2014) using BWA (Li and Durbin 2009), and 88.05% of the reads were mapped exactly to unique genome regions. A total of 254,068 SLAFs were identified after the filtering of low-depth SLAF tags, 28,731 of which were polymorphic, for a rate of polymorphism of 11.31% (data not shown). According to the encoding rules of the segregation patterns, 25,608 polymorphic SLAFs were successfully encoded, 22,855 of which were the aa × bb type (Fig. 1). To improve the accuracy of the genotype, we took three more stringent steps to filter the markers: SLAFs with a depth of less than tenfold in each parent were discarded, SLAFs with a depth of less than fivefold in each of the 150 BC1 plants were defined as missing, and SLAFs with more than 10% missing data were excluded. Ultimately, 3548 high-quality SLAFs met these criteria and were used in subsequent analyses. Out of the 3528 genetically mapped SLAF markers, 3199 and 329 were identified on the 16 pseudo-molecules and 113 unanchored scaffolds of Zhongzhi No. 13 genome version 1.0, respectively (Supplementary Data S1).

Fig. 1.

Number of SLAF markers in each segregation pattern. The x-axis indicates eight segregation patterns grouped by genotype encoding rule and the y-axis represents number of SLAF markers

Genetic map constructed with SLAF markers

A high-density linkage map with 3528 SLAF markers was constructed (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Data S1). The map contained 13 LGs and covered a genetic distance of 1312.52 cM in total, with an average distance of 0.37 cM between adjacent markers. The number of markers per LG ranged from 167 (LG11) to 469 (LG05), with an average of 271.4. The genetic length of each LG ranged from 64.74 cM (LG10) to 148.06 cM (LG07), with an average of 100.96 cM. The SLAF markers did not distribute evenly on each LG, and there were eight large gaps of more than 10 cM on seven LGs (i.e., LG01, LG02, LG03, LG04, LG07, LG12, and LG13).

Table 1.

Summary of the 13 linkage groups on the genetic map

| Linkage group | Number of markers | Length (cM) | Average distance (cM) | Largest gap (cM) | Number of gaps (≥ 10 cM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG01 | 374 | 104.44 | 0.28 | 12.30 | 1 |

| LG02 | 292 | 95.31 | 0.33 | 10.69 | 2 |

| LG03 | 388 | 123.69 | 0.32 | 16.65 | 1 |

| LG04 | 170 | 83.60 | 0.49 | 11.10 | 1 |

| LG05 | 469 | 121.32 | 0.26 | 5.84 | 0 |

| LG06 | 307 | 117.74 | 0.38 | 7.76 | 0 |

| LG07 | 299 | 148.06 | 0.50 | 12.24 | 1 |

| LG08 | 244 | 81.79 | 0.34 | 7.47 | 0 |

| LG09 | 240 | 104.63 | 0.44 | 7.60 | 0 |

| LG10 | 200 | 64.74 | 0.33 | 9.70 | 0 |

| LG11 | 167 | 64.88 | 0.39 | 5.18 | 0 |

| LG12 | 170 | 94.37 | 0.56 | 11.27 | 1 |

| LG13 | 208 | 107.96 | 0.52 | 10.15 | 1 |

| Total | 3528 | 1312.52 | 0.37 | 16.65 | 8 |

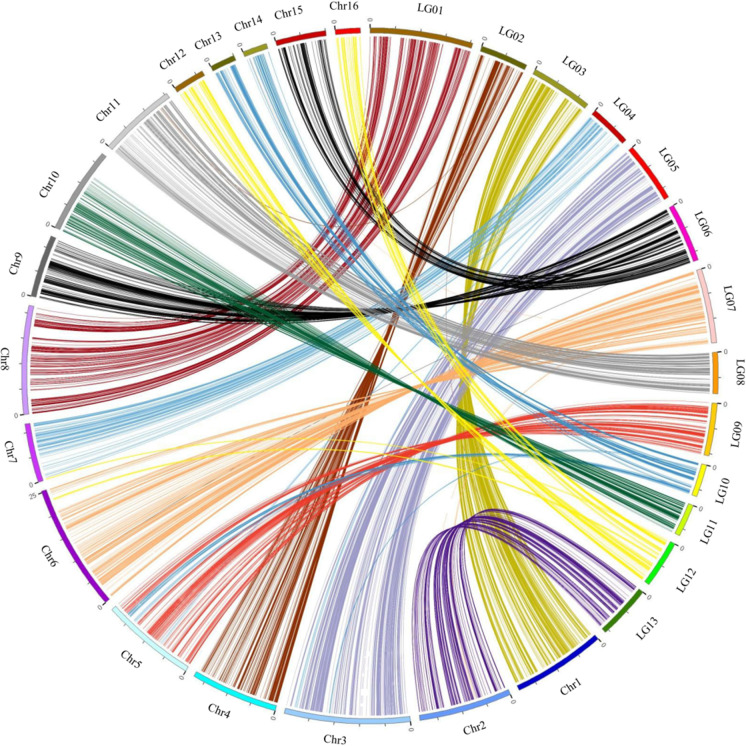

Since the number of pseudo-molecules of Zhongzhi No. 13 genome version 1.0 is 16, which is three more than the number of chromosomes in sesame (n = 13). The genetic and physical positions of the 3199 SLAF markers mapped to pseudo-molecules were plotted with Circos (Krzywinski et al. 2009), and the relationship between the 13 LGs of the current genetic map and the 16 pseudo-chromosomes (Chr.1–Chr.16) of the reference genome was determined (Fig. 2). The pseudo-chromosomes Chr.1, Chr.2, Chr.3, Chr.4, Chr.5, Chr.6, Chr.7, Chr.8, Chr.10, and Chr.11 matched with LG03, LG13, LG05, LG02, LG09, LG07, LG04, LG01, LG11, and LG08, respectively. Chr.9 and Chr.15 were linked and matched with LG06, Chr.12, and Chr.16 jointly corresponded to LG12, as well as Chr.13 and Chr.14 to LG10. Most markers from each pseudo-chromosome were grouped into the corresponding LG. However, there were still 68 markers (1, 4, 5, 42, 9, 4, 2, and 1 from Chr.1, Chr.2, Chr.3, Chr.5, Chr.6, Chr.7, Chr.11, and Chr.14, respectively) that were grouped into different LGs. Take Chr.5, for example, on which 257 SLAF markers were identified, and 215 of them were grouped into LG09, while 37 and five markers were grouped into LG10 and LG 04, respectively. The result was consistent with almost all properties of an improved Zhongzhi No. 13 genome version 2.0 reported by Wang et al. (2016).

Fig. 2.

Relationships of 13 LGs of the genetic map and 16 pseudo-chromosomes of Zhongzhi No. 13 genome version 1.0

Phenotype variation and correlations between yield-related traits

Seven yield-related traits of the 150 BC1F2 families were measured in three different locations, and descriptive statistics are shown in Table 2. The traits showed substantial variation and followed normal or near-normal distributions. Analyses of variance for the seven traits across the three different environments were performed, and highly significant differences (P < 0.01) were observed in both the 150 genotypes and three environments (data not shown). The broad-sense heritability (h2) of the seven traits varied greatly, with a range of 40.71 to 81.03%. FCH and HI had relatively high heritability; SY, SW, and CN had moderate heritability; and SN and PH had low heritability (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and broad-sense heritability (h2) for seven yield-related traits

| Trait | Environment | Mean | SD | Range | CV (%) | Excess Kurtosis | Skewness | h2(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SY (g) | Nanyang | 3.99 | 1.73 | 1.56–8.63 | 43.41 | − 0.15 | 0.55 | 70.83 |

| Luohe | 2.08 | 1.46 | 1.08–8.27 | 70.17 | 1.96 | 1.26 | ||

| Pingyu | 2.95 | 1.38 | 1.18–7.98 | 46.93 | 0.48 | 0.78 | ||

| Mean | 3.01 | 1.39 | 1.32–7.96 | 46.3 | 0.37 | 0.75 | ||

| CN | Nanyang | 43.31 | 12.08 | 13.00–82.73 | 27.88 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 66.35 |

| Luohe | 32.1 | 15.06 | 12.03–88.45 | 46.91 | 0.9 | 0.76 | ||

| Pingyu | 40.75 | 11.42 | 17.29–72.18 | 28.04 | 0 | 0.51 | ||

| Mean | 38.72 | 11.68 | 15.69–72.83 | 30.17 | 0.1 | 0.58 | ||

| SN | Nanyang | 54.93 | 8.38 | 32.71–75.32 | 15.25 | − 0.17 | − 0.1 | 47.78 |

| Luohe | 59.92 | 9.25 | 27.71–80.23 | 15.43 | 0.42 | − 0.44 | ||

| Pingyu | 57.65 | 7.08 | 37.61–75.63 | 12.27 | − 0.22 | − 0.13 | ||

| Mean | 57.5 | 7.03 | 37.66–75.34 | 12.23 | − 0.26 | − 0.1 | ||

| SW (g) | Nanyang | 2.39 | 0.27 | 1.78–3.07 | 11.22 | − 0.41 | − 0.07 | 69.23 |

| Luohe | 2.37 | 0.26 | 1.54–3.03 | 11.19 | − 0.12 | − 0.35 | ||

| Pingyu | 2.31 | 0.2 | 1.87–2.83 | 8.58 | − 0.25 | 0.19 | ||

| Mean | 2.36 | 0.21 | 1.90–2.96 | 9.01 | − 0.22 | 0.05 | ||

| PH (cm) | Nanyang | 185.07 | 8.68 | 142.65–205.35 | 4.69 | 3.36 | − 0.72 | 40.71 |

| Luohe | 124.45 | 14.94 | 91.98–154.10 | 12 | − 0.6 | − 0.06 | ||

| Pingyu | 171.69 | 7.61 | 141.55–188.43 | 4.43 | 0.94 | − 0.35 | ||

| Mean | 160.41 | 8.27 | 130.08–179.52 | 5.16 | 0.71 | − 0.38 | ||

| FCH (cm) | Nanyang | 123.38 | 13.08 | 85.50–149.48 | 10.6 | − 0.35 | − 0.26 | 81.03 |

| Luohe | 62.89 | 16.66 | 35.08–105.24 | 26.49 | − 0.82 | 0.27 | ||

| Pingyu | 95.18 | 14.15 | 63.09–123.67 | 14.87 | − 0.98 | − 0.06 | ||

| Mean | 93.82 | 13.86 | 61.22–123.00 | 14.78 | − 0.9 | − 0.03 | ||

| HI (%) | Nanyang | 9.46 | 3.88 | 2.39–19.21 | 40.99 | − 0.77 | 0.27 | 80.63 |

| Luohe | 8.18 | 4.83 | 1.49–22.80 | 59.08 | − 0.15 | 0.69 | ||

| Pingyu | 9.1 | 3.84 | 1.94–18.62 | 42.18 | − 0.83 | 0.33 | ||

| Mean | 8.91 | 3.92 | 1.66–19.48 | 44.03 | − 0.75 | 0.4 |

SY seed yield per plant; CN number of capsules per plant; SN number of seeds per capsule; SW 1000-seed weight; PH plant height; FCH height of first capsule; HI harvest index; SD standard deviation; CV coefficient of variation; h2 broad-sense heritability

Phenotypic correlation analyses were performed based on mean values of the seven yield-related traits across the three environments, and the results showed that SY was highly correlated with the other six traits. The strongest positive correlation (r = 0.9341) was observed between SY and HI, whereas a strong significant negative correlation (r = − 0.7110) was found between SY and FCH. There were strong significant positive correlations between HI and CN and between SN and SW, and a significant negative correlation between HI and FCH was also observed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations between yield-related traits

| Trait | SY | CN | SN | SW | PH | FCH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 0.8988** | |||||

| SN | 0.4600** | 0.2635** | ||||

| SW | 0.6321** | 0.4441** | 0.5128** | |||

| PH | 0.2175** | 0.1742* | 0.3691** | 0.3616** | ||

| FCH | − 0.7110** | − 0.6811** | − 0.1912* | − 0.3777** | 0.3183** | |

| HI | 0.9341** | 0.8296** | 0.4883** | 0.5801** | 0.104 | − 0.7935** |

SY seed yield per plant; CN number of capsules per plant; SN number of seeds per capsule; SW 1000-seed weight; PH plant height; FCH height of first capsule; HI harvest index. ** and * indicate significance at 0.01 and 0.05 levels, respectively

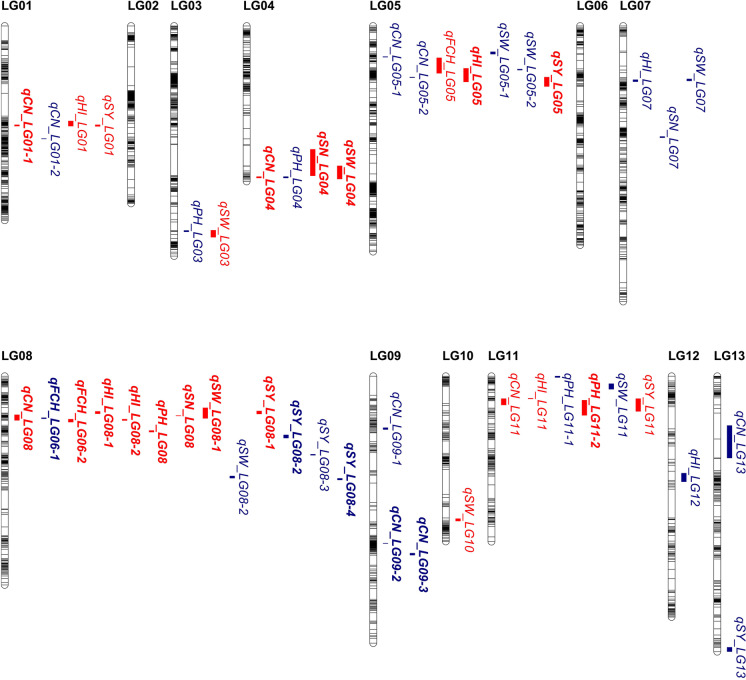

QTLs for yield-related traits

In total, 46 significant QTLs were identified for the seven yield-related traits in the BC1 population across the three environments (Table 4 and Fig. 3), with a range of 3–11 QTLs for each trait. These QTLs were distributed on 11 LGs, each explaining 2.34–71.41% of the PV with LOD scores ranging from 3.27 to 103.81 in different environments. Of the QTLs, 23 were stable QTLs that were detected in more than one environment, and 20 were major QTLs that explained more than 10% of the corresponding PV in at least one environment. The distribution of these QTLs over the genome was not uniform, five LGs (LG01, LG04, LG05, LG08, and LG11) together contained more than 73.9% of the QTLs (Table 4 and Fig. 3). The Yuzhi 4 alleles of 37 QTLs and the BS alleles of 9 QTLs contributed to increasing the target trait value (Table 4). Detailed results for the QTLs identified are described in the following sections.

Table 4.

QTLs for yield-related traits detected in three different environments

| Trait | QTL | LG | Environment | Position | Marker interval | LOD | PVE(%) | Additive effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SY | qSY_LG01 | LG01 | Pingyu | 53.50 | Marker495689-Marker635028 | 5.01 | 3.42 | 0.57 |

| Luohe | 53.70 | Marker635028-Marker558741 | 3.99 | 8.62 | 0.86 | |||

| qSY_LG05 | LG05 | Nanyang | 27.70 | Marker708382-Marker698598 | 4.25 | 6.06 | 0.85 | |

| Pingyu | 29.50 | Marker915637-Marker792853 | 11.35 | 8.29 | 0.87 | |||

| Luohe | 30.30 | Marker792853-Marker947685 | 7.29 | 12.67 | 1.03 | |||

| qSY_LG08-1 | LG08 | Nanyang | 14.40 | Marker1759630-Marker1772459 | 23.15 | 43.02 | 2.26 | |

| Pingyu | 14.50 | Marker1772459-Marker1784297 | 33.36 | 35.56 | 1.81 | |||

| qSY_LG08-2 | LG08 | Luohe | 23.30 | Marker1781727-Marker1814500 | 12.88 | 24.85 | 1.44 | |

| qSY_LG08-3 | LG08 | Pingyu | 30.70 | Marker1779182-Marker1750405 | 8.57 | 6.17 | -0.75 | |

| qSY_LG08-4 | LG08 | Pingyu | 40.50 | Marker1725315-Marker1858600 | 15.43 | 12.10 | 1.06 | |

| qSY_LG11 | LG11 | Pingyu | 9.10 | Marker2842364-Marker2883431 | 9.28 | 6.56 | 0.78 | |

| Luohe | 9.70 | Marker2866120-Marker2776733 | 3.98 | 6.58 | 0.74 | |||

| Nanyang | 13.40 | Marker2761314-Marker2742143 | 4.73 | 6.56 | 0.88 | |||

| qSY_LG13 | LG13 | Pingyu | 107.90 | Marker1416044-Marker1493415 | 3.64 | 2.34 | 0.47 | |

| CN | qCN_LG01-1 | LG01 | Nanyang | 53.40 | Marker495689-Marker635028 | 5.36 | 6.44 | 6.48 |

| Luohe | 53.60 | Marker495689-Marker635028 | 8.24 | 12.14 | 10.44 | |||

| qCN_LG01-2 | LG01 | Pingyu | 60.60 | Marker382587-Marker3183322 | 5.32 | 3.23 | 4.94 | |

| qCN_LG04 | LG04 | Pingyu | 81.00 | Marker3242165-Marker1073502 | 7.80 | 4.82 | 6.09 | |

| Nanyang | 81.30 | Marker1073502-Marker3118271 | 9.45 | 12.15 | 8.93 | |||

| qCN_LG05-1 | LG05 | Pingyu | 16.70 | Marker799619-Marker912202 | 11.50 | 7.69 | 7.62 | |

| qCN_LG05-2 | LG05 | Nanyang | 27.70 | Marker708382-Marker698598 | 7.55 | 9.64 | 7.84 | |

| qCN_LG08 | LG08 | Nanyang | 15.30 | Marker1747755-Marker2158734 | 15.03 | 21.20 | 11.63 | |

| Luohe | 16.90 | Marker1846037-Marker1771424 | 16.07 | 27.15 | 15.39 | |||

| Pingyu | 17.00 | Marker1771424-Marker1753249 | 22.27 | 17.66 | 11.51 | |||

| qCN_LG09-1 | LG09 | Nanyang | 20.60 | Marker2983686-Marker2964091 | 3.52 | 4.19 | 5.23 | |

| qCN_LG09-2 | LG09 | Pingyu | 65.50 | Marker3151281-Marker2986783 | 24.97 | 21.87 | 12.84 | |

| qCN_LG09-3 | LG09 | Pingyu | 69.80 | Marker1624580-Marker3161742 | 17.26 | 12.87 | -9.82 | |

| qCN_LG11 | LG11 | Pingyu | 9.10 | Marker2842364-Marker2883431 | 8.43 | 5.29 | 6.30 | |

| Luohe | 9.70 | Marker2866120-Marker2776733 | 5.61 | 7.90 | 8.30 | |||

| qCN_LG13 | LG13 | Pingyu | 24.60 | Marker1433326-Marker1550818 | 3.79 | 2.21 | 4.09 | |

| SN | qSN_LG04 | LG04 | Pingyu | 75.20 | Marker3193355-Marker3297566 | 5.71 | 12.35 | − 5.12 |

| Nanyang | 80.00 | Marker3011685-Marker2161667 | 7.04 | 15.23 | − 7.35 | |||

| qSN_LG07 | LG07 | Luohe | 59.70 | Marker2447918-Marker2617824 | 3.27 | 8.93 | 5.11 | |

| qSN_LG08 | LG08 | Luohe | 15.50 | Marker2158734-Marker1733709 | 5.80 | 16.34 | 6.88 | |

| Pingyu | 15.50 | Marker2158734-Marker1733709 | 6.63 | 14.60 | 5.55 | |||

| SW | qSW_LG03 | LG03 | Nanyang | 110.50 | Marker34055-Marker126534 | 4.03 | 5.58 | 0.13 |

| Pingyu | 111.70 | Marker126534-Marker93889 | 4.24 | 5.20 | 0.09 | |||

| qSW_LG04 | LG04 | Pingyu | 77.10 | Marker3261588-Marker3081220 | 7.12 | 9.26 | − 0.12 | |

| Nanyang | 81.70 | Marker3118271-Marker226541 | 9.04 | 13.59 | − 0.21 | |||

| qSW_LG05-1 | LG05 | Nanyang | 14.70 | Marker853243-Marker698688 | 5.03 | 7.08 | 0.15 | |

| qSW_LG05-2 | LG05 | Pingyu | 23.50 | Marker763750-Marker953444 | 5.57 | 6.99 | 0.10 | |

| qSW_LG07 | LG07 | Luohe | 29.10 | Marker2483488-Marker2622427 | 3.44 | 7.91 | 0.14 | |

| qSW_LG08-1 | LG08 | Nanyang | 13.70 | Marker1759630-Marker1772459 | 14.41 | 24.04 | 0.27 | |

| Pingyu | 16.30 | Marker1809428-Marker1740534 | 18.61 | 28.44 | 0.21 | |||

| qSW_LG08-2 | LG08 | Luohe | 39.40 | Marker1821608-Marker1824772 | 4.41 | 9.94 | 0.15 | |

| qSW_LG10 | LG10 | Nanyang | 56.40 | Marker3029360-Marker1100923 | 4.75 | 6.65 | 0.14 | |

| Pingyu | 56.40 | Marker3029360-Marker1100923 | 5.58 | 6.89 | 0.10 | |||

| qSW_LG11 | LG11 | Pingyu | 3.40 | Marker1294916-Marker2734898 | 3.85 | 4.62 | 0.08 | |

| PH | qPH_LG03 | LG03 | Pingyu | 110.50 | Marker34055-Marker126534 | 5.10 | 9.44 | 4.65 |

| qPH_LG04 | LG04 | Pingyu | 81.00 | Marker3242165-Marker1073502 | 5.19 | 9.59 | − 4.74 | |

| qPH_LG08 | LG08 | Pingyu | 21.40 | Marker1875857-Marker1771208 | 3.43 | 6.25 | − 3.78 | |

| Nanyang | 21.70 | Marker1817114-Marker1784105 | 5.07 | 11.23 | − 6.07 | |||

| qPH_LG11-1 | LG11 | Nanyang | 0.00 | Marker1299674-Marker1295768 | 4.57 | 9.99 | 5.73 | |

| qPH_LG11-2 | LG11 | Luohe | 10.70 | Marker2866120-Marker2776733 | 4.51 | 12.80 | 10.65 | |

| Pingyu | 14.90 | Marker2781143-Marker2879404 | 8.86 | 17.44 | 6.31 | |||

| FCH | qFCH_LG05 | LG05 | Luohe | 17.60 | Marker691883-Marker903633 | 5.58 | 6.53 | − 8.53 |

| Pingyu | 20.40 | Marker830672-Marker860323 | 8.75 | 7.09 | − 7.33 | |||

| Nanyang | 25.30 | Marker705113-Marker910164 | 3.43 | 0.19 | − 5.79 | |||

| qFCH_LG08-1 | LG08 | Nanyang | 16.40 | Marker1740534-Marker1819127 | 88.15 | 23.83 | 64.75 | |

| qFCH_LG08-2 | LG08 | Luohe | 17.00 | Marker1771424-Marker1753249 | 32.30 | 59.15 | − 25.67 | |

| Pingyu | 17.10 | Marker1771424-Marker1753249 | 47.14 | 71.41 | − 23.29 | |||

| Nanyang | 17.40 | Marker1753249-Marker1796920 | 103.81 | 39.71 | − 83.62 | |||

| HI | qHI_LG01 | LG01 | Pingyu | 51.20 | Marker501333-Marker469296 | 3.61 | 4.34 | 1.28 |

| Luohe | 53.60 | Marker495689-Marker635028 | 5.74 | 5.71 | 2.44 | |||

| qHI_LG05 | LG05 | Luohe | 23.10 | Marker910387-Marker763750 | 9.62 | 10.28 | 3.21 | |

| Nanyang | 27.70 | Marker708382-Marker698598 | 6.22 | 6.49 | 1.95 | |||

| Pingyu | 29.50 | Marker915637-Marker792853 | 9.72 | 10.69 | 2.00 | |||

| qHI_LG07 | LG07 | Pingyu | 29.50 | Marker2622427-Marker2446965 | 5.40 | 5.56 | 1.44 | |

| qHI_LG08-1 | LG08 | Pingyu | 14.40 | Marker1759630-Marker1772459 | 17.34 | 21.65 | 2.85 | |

| Nanyang | 14.50 | Marker1772459-Marker1784297 | 36.28 | 59.19 | 5.89 | |||

| qHI_LG08-2 | LG08 | Luohe | 16.90 | Marker1846037-Marker1771424 | 29.88 | 44.45 | 6.69 | |

| Pingyu | 17.10 | Marker1771424-Marker1753249 | 24.12 | 33.89 | 3.57 | |||

| qHI_LG11 | LG11 | Nanyang | 8.70 | Marker2728217-Marker2910618 | 3.69 | 3.49 | 1.43 | |

| Pingyu | 8.70 | Marker2728217-Marker2910618 | 4.84 | 4.97 | 1.36 | |||

| qHI_LG12 | LG12 | Nanyang | 40.80 | Marker2096957-Marker2480553 | 3.70 | 3.47 | − 1.43 |

SY seed yield per plant; CN number of capsules per plant; SN number of seeds per capsule; SW 1000-seed weight; PH plant height; FCH height of first capsule; HI harvest index

Fig. 3.

Genomic distribution of QTLs for sesame yield-related traits. The black bar on each LG column indicates a SLAF marker. QTLs identified in more than one environment are shown in red, and those detected in only one environment are shown in blue. Major QTLs (with PVE ≥ 10% in at least one environment) are shown in bold

Seed yield per plant

Eight QTLs for SY were identified on LG01, LG05, LG08, LG11, and LG13, each explaining 2.34–43.02% of the PV, with LOD scores ranging from 3.64 to 33.36. Of which, four, three, and seven QTLs were detected in Luohe, Nanyang, and Pingyu, respectively. The total PV explained by all QTLs in the three environments were 52.72%, 55.64%, and 74.44%, respectively, with an average of 60.93%. Two QTLs, qSY_LG05 and qSY_LG11, were simultaneously identified in all three environments; two other QTLs, qSY_LG01 and qSY_LG08-1, were detected in two environments; and another four QTLs were detected in only one environment. The major QTL, qSY_LG08-1, explained 43.02% and 35.56% of the PV in Nanyang and Pingyu, respectively. The additive effects for almost all QTLs were positive, which indicates that Yuzhi 4 alleles of all QTLs but qSY_LG08-3 contributed to increasing SY (Table 4).

Number of capsules per plant

Eleven QTLs for CN were detected. They were distributed on LG01, LG04, LG05, LG08, LG09, LG11, and LG13; explained 2.21%–27.15% of the PV; and had LOD scores of 3.52–24.97. Of which, three, five and nine QTLs could be detected in Luohe, Nanyang, and Pingyu, respectively. The total PV explained by all QTLs in the three environments were 47.19%, 53.62%, and 75.64%, respectively, with an average of 58.82%. The major QTL, qCN_LG08, was detected in all three environments, accounting for 21.20%, 27.15%, and 17.66% of the PV in Nanyang, Luohe, and Pingyu, respectively. Three minor QTLs, qCN_LG01-1, qCN_LG04, and qCN_LG11, were detected in two environments; another seven QTLs were identified in only one environment. Yuzhi 4 alleles of all QTLs but qCN_LG09-3 contributed to increasing CN (Table 4).

Number of seeds per capsule

Three QTLs for SN were identified on LG04, LG07, and LG08, each explaining 8.93%–16.34% of the PV, with LOD scores ranging from 3.27 to 7.04. Of which, two, one and two QTLs were detected in Luohe, Nanyang, and Pingyu, respectively. The total PV explained by all QTLs in the three environments were 25.27%, 15.23%, and 26.95%, respectively, with an average of 22.48%. A major QTL, qSN_LG04, was identified in Nanyang and Pingyu, accounting for 15.23% and 12.35% of the PV, respectively. The other major QTL, qSN_LG08, was identified in Luohe and Pingyu, accounting for 16.34% and 14.60% of the PV, respectively. The minor QTL, qSN_LG07, was detected in only one environment. Yuzhi 4 alleles of qSN_LG07 and qSN_LG08 contributed to increasing SN, while Yuzhi 4 alleles of qSN_LG04 led to decreased SN (Table 4).

Seed weight

Nine QTLs for 1000-seed weight were identified on LG03, LG04, LG05, LG07, LG08, LG10, and LG11, each explaining 4.62%–28.44% of the PV, with LOD scores ranging from 3.44 to 18.61. Of which, two, five, and six QTLs were detected in Luohe, Nanyang, and Pingyu, respectively. The total PV explained by all QTLs in the three environments were 17.85%, 56.94%, and 61.4%, respectively, with an average of 45.40%. Four QTLs, qSW_LG03, qSW_LG04, qSW_LG08-1, and qSW_LG10, were identified in two environments; another seven QTLs were identified in only one environment. The major QTL, qCN_LG08-1, was detected in Nanyang and Pingyu, accounting for 24.04% and 28.44% of the PV, respectively. Yuzhi 4 alleles of all QTLs but qSW_LG04 contributed to increasing SW (Table 4).

Plant height

Five QTLs for PH were identified on LG03, LG04, LG08, and LG11, each explaining 6.25%–17.44% of the PV, with LOD scores ranging from 3.43 to 8.86. Of which, one, two and four QTLs were detected in Luohe, Nanyang, and Pingyu, respectively. The total PV explained by all QTLs in the three environments were 12.80%, 21.22%, and 42.72%, respectively, with an average of 25.58%. Two QTLs, qPH_LG08 and qPH_LG11-2, could be identified in two environments; the other three QTLs were only identified in one environment. Yuzhi 4 alleles of qPH_LG03, qPH_LG11-1, and qPH_LG11-2 contributed to increasing PH, where those of qPH_LG04 and qPH_LG08 led to decreased PH (Table 4).

Height of the first capsule

Three QTLs for FCH were identified on LG05 and LG08. Of which, two, three, and two QTLs were detected in Luohe, Nanyang, and Pingyu, respectively. The total PV explained by all QTLs in the three environments were 65.68%, 63.73%, and 78.50%, respectively, with an average of 69.30%. One major QTL, qFCH_LG08-2, was simultaneously identified in Nanyang, Luohe, and Pingyu and explained 39.71%, 59.15%, and 71.41% of the PV, respectively. It is interesting that the other major QTL, qFCH_LG08-1, was also detected at 16.4 cM on LG08 in Nanyang, which explained 23.83% of the PV. In addition, a minor stable QTL, qFCH_LG05, was identified in all three environments. Yuzhi 4 alleles of qFCH_LG05 and qFCH_LG08-2 contributed to decreasing FCH, whereas those of qFCH_LG08-1 increased FCH (Table 4).

Harvest index

Seven QTLs for HI were identified on LG01, LG05, LG07, LG08, LG11, and LG12, each explaining 3.47–59.19% of the PV, with LOD scores ranging from 3.61 to 36.28. Of which, three, four, and six QTLs were detected in Luohe, Nanyang, and Pingyu, respectively. The total PV explained by all QTLs in the three environments were 60.44%, 72.64%, and 81.10%, respectively, with an average of 71.39%. The qHI_LG05 was simultaneously identified in all three environments; four QTLs, qHI_LG01, qHI_LG08-1, qHI_LG08-2, and qHI_LG11, were detected in two environments; and another two QTLs were identified in only one environment. Yuzhi 4 alleles of all QTLs but qHI_LG12 contributed to increasing HI (Table 4).

Discussion

QTLs for yield-related traits identified in sesame

The yield is a very complex trait in crops, as it is the result of the actions and interactions of many different traits. In theory, sesame seed yield, at the single plant level, is determined by three direct components: capsules per plant, seeds per capsule, and seed weight. Some indirect factors, including plant height, height of the first capsule, and other traits, are also strongly associated with the seed yield of sesame (Delgodo and Yermanos 1975; Biabani and Pakniyat 2008; Emamgholizadeh et al. 2015). To reveal the genetic architecture of seed yield, individual yield-related components should be fully explored. In this study, we identified a total of 46 QTLs for seven yield-related traits distributed on 11 LGs, all LGs except for LG02 and LG06. The distribution of these QTLs over the genome was not uniform. Five LGs (LG01, LG04, LG05, LG08, and LG11) together contained more than 73.9% of the QTLs, and the three most heavily populated LGs (LG08, LG05, and LG11) possessed 13, 7, and 6 QTLs, respectively (Table 4 and Fig. 3). In addition, we found five genome regions each densely populated with at least four QTLs; for example, a region of 12.5–40.5 cM on LG08 contained 13 QTLs. Breeders should focus their efforts on the genome regions that contain the most QTLs for yield potential; this might also partially explain the fact that significant correlations are often observed among most yield-related traits (Table 3). Given that pleiotropy and close linkage are the two major reasons for trait correlation and QTL co-location (Chen and Lübberstedt 2010), additional studies (e.g., fine mapping) are needed to determine whether pleiotropy or tight linkages between loci lead to QTL clusters.

The averaged total PV explained by all QTLs for SY, CN, SN, SW, PH, FCH, and HI were 60.93%, 58.82%, 22.48%, 45.40%, 25.58%, 69.30%, and 71.39%, respectively; and the broad-sense heritability for them estimated from ANOVA were 70.83%, 66.35%, 47.78%, 69.23%, 40.71%, 81.03%, and 80.63%, respectively. The total PVE for each trait was lower than the corresponding broad-sense heritability, which indicates that besides minor additive QTLs that cannot be detected, there are still QTLs for genotype by environment interaction should be noticed. As yield-related traits have complex genetic bases and are prone to influences from the environment, QTLs are more useful if they are independent of the environment and/or genetic background. In this study, 23 of the 46 QTLs identified were detected in more than one environment and thus were considered stable QTLs that could be used for marker-assisted breeding. In addition, the availability of data on collinearity between the current genetic map and Zhongzhi No. 13 genome assembly allowed us to compare the QTLs detected in the present study with those identified in previous studies. Wu et al. (2014) detected 13 and 17 QTLs for seven yield-related traits by the multiple-interval mapping and the mixed linear composite interval mapping, respectively. Wang et al. (2016) identified 10 QTLs for plant height and 8 QTLs for the height of the first capsule. Unfortunately, only one consensus QTL for FCH was identified among the three studies, that is, qFCH_LG05 in our research had the same genomic position as qFCH_301 reported by Wang et al. (2016). Zhou et al. (2018) performed genome-wide association studies using 705 diverse lines and found 646 loci significantly associated with 39 seed yield-related traits (p < 10–7). When we aligned the QTL intervals detected in this study onto the Zhongzhi No. 13 reference genome, significantly associated loci identified in Zhou et al.’s study (2018) were found to locate in at least 3 QTL regions (qSY_LG05, qFCH_LG05, qSW_LG04). These QTLs should be less affected by the environment and genetic background, and should be more suitable for MAS in breeding programs.

Favorable alleles in locally adapted and exotic germplasm resources

Because several founder parents were used repeatedly in Chinese sesame breeding programs in the past decades, the genetic bases of released varieties became extremely narrow, and yield enhancement plateaued (Liu et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2017). Novel variations in germplasm, especially in exotic ones, should be fully exploited and introduced into breeding programs to broaden the genetic bases of modern cultivars (Burt et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2017b). In this study, a segregating population derived from the cross between the locally adapted cultivar Yuzhi 4 and the exotic germplasm line BS was used to map QTLs for yield-related traits. Yuzhi 4 is an elite variety of sesame developed in 1980s that has been widely grown in most sesame-growing regions in China over the past three decades, because of its overall agronomic performance, especially its yield and stability. In addition, it is one of the most important core parents in Chinese sesame breeding programs, from which more than one-third of the cultivars released in the Yellow River and Huaihe River regions are derived (Liu et al. 2015a, b). BS is an anonymous cultivar introduced from Bangladesh, with multiple basal branches, a small seed size, high lignan content, and a late flowering time compared to Yuzhi 4 (Mei et al. 2017). In this study, the Yuzhi 4 alleles of 37 QTLs and the BS alleles of 9 QTLs were identified as contributing to increases in the corresponding traits (Table 4). Given that the allele that decreases FCH is defined as favorable, since FCH is negatively associated with SY, the favorable alleles of 38 QTLs originated from the locally adapted cultivar Yuzhi 4. The favorable alleles of eight QTLs for PH, SN, and SW were contributed by BS. This means that alleles present in phenotypically inferior exotic germplasm have the potential to increase yield and that introducing alleles from BS at these eight QTLs should further improve the SN and SW of Yuzhi 4.

It should be noted that we found nine large-effect QTLs in the region of 13.7–23.0 cM on LG08, each explaining 14.60–71.41% of the corresponding PV in different environments. This is unlikely the case in traditional QTL mapping studies, especially for complex traits such as yield-related traits. There are at least two possible explanations for these large-effect QTLs. The population might have been developed from a cross between a locally adapted elite variety and an exotic landrace, or the phenotype traits might have been evaluated in middle-latitude areas in which plants were exposed to unfavorable light and heat conditions. That might have artificially exacerbated the effects of the QTLs. More effort is needed to validate the obtained QTLs using linkage mapping and/or association mapping in additional genetic backgrounds and environments.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed a high-density genetic map with 3528 SLAF markers. Based on this map, 46 QTLs for seven yield-related traits were identified on 11 LGs, and favorable alleles were analyzed in both parents. The results should provide useful information for MAS and functional gene cloning in sesame.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Detailed information on 3,528 mapped SLAF markers (TXT 2.27 MB)

Detailed information on the genetic map (XLXS 158 KB)

Author contribution

Y.Z. and Q.M. designed the study. H.M. and Y.L. developed populations and performed data analyses. H.M. wrote and Y.L. revised the manuscript. C.C., C.H., F.X., L.Z, Z.D., K.W., and X.J. took part in some of the field and/or library work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-14–1-01), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31301359), the Key Project of Science and Technology of Henan Province (201300110600), the Key R & D and Promotion Projects of Henan Province (202102110026), and the Science-Technology Foundation for Outstanding Young Scientists of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2018YQ27, 2020YQ26).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hongxian Mei and Yanyang Liu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yongzhan Zheng, Email: sesame168@163.com.

Qingrong Ma, Email: zzmqr@163.com.

References

- Ashri A. Sesame breeding. In: Janick J, editor. Plant breeding reviews. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 179–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ashri A (2007) Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) In: Singh RJ (ed) Genetic resources, chromosome engineering and crops improvement: oilseed crops, Vol. 4. CRC, Boca Raton, pp 231–289

- Bedigian D, Harlan JR. Evidence for cultivation of sesame in the ancient world. Econ Bot. 1986;40:137–154. doi: 10.1007/BF02859136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biabani AR, Pakniyat H. Evaluation of seed yield-related characters in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) using factor and path analysis. Pakistan J Biol Sci. 2008;11:1157–1160. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2008.1157.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt AJ, Grainger CM, Smid MP, Shelp BJ, Lee EA. Allele mining of exotic maize germplasm to enhance macular carotenoids. Crop Sci. 2011;51:991–1004. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2010.06.0335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Lübberstedt T. Molecular basis of trait correlations. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgodo M, Yermanos DM. Yield components of sesame (Sesamum Indicum L.) under different population densities. Econ Bot. 1975;29:69–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02861256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dossa K. A physical map of important QTLs, functional markers and genes available for sesame breeding programs. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2016;22:613–619. doi: 10.1007/s12298-016-0385-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossa K, Li D, Zhou R, Yu J, Wang L, Zhang Y, You J, Liu A, Mmadi MA, Fonceka D, Diouf D, Cissé N, Wei X, Zhang X. The genetic basis of drought tolerance in the high oil crop Sesamum indicum. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17:1788–1803. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Zhang H, Wei L, Li C, Duan Y, Wang H (2019) A high-density genetic map constructed using specific length amplified fragment (SLAF) sequencing and QTL mapping of seed-related traits in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). BMC Plant Biol 19:588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emamgholizadeh S, Parsaeian M, Baradaran M. Seed yield prediction of sesame using artificial neural network. Eur J Agron. 2015;68:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2015.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gadri Y, Williams LE, Peleg Z (2020) Tradeoffs between yield components promote crop stability in sesame. Plant Sci. 295:110105 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Guo T, Yu H, Qiu J, Li J, Han B, Lin H. Advances in rice genetics and breeding by molecular design in China. Sci Sin Vitae. 2019;49:1185–1212. [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Xu F, Min MH, Chu SH, Kim KW, Park YJ. Genome-wide association study of vitamin E using genotyping by sequencing in sesame (Sesamum indicum) Genes Genomics. 2019;41:1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s13258-019-00837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannink JL, Lorenz AJ, Iwata H. Genomic selection in plant breeding: from theory to practice. Brief Funct Genomics. 2010;9:166–177. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elq001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ye G, Wang J. A modified algorithm for the improvement of composite interval mapping. Genetics. 2007;175:361–374. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.066811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wu K, Yang M, Zuo Y, Zhao Y. DNA fingerprinting of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) varieties (lines) from recent national regional trials in China. Acta Agron Sin. 2012;38:596–605. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2012.00596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Zhou F, Zhao Y. Pedigree analysis of sesame cultivars released in China. Chin J Oil Crop Sci. 2015;37:411–426. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Zhou X, Wu K, Yang M, Zhao Y (2015b) Inheritance and molecular mapping of a novel dominant genic male-sterile gene in Sesamum indicum L. Mol Breed 35:9

- McCouch SR, Cho YG, Yano PE, Blinstrub M, Morishima H, Kinoshita T. Report on QTL nomenclature. Rice Genet Newslet. 1997;14:11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mei H, Liu Y, Du Z, Wu K, Cui C, Jiang X, Zhang H, Zheng Y (2017) High-density genetic map construction and gene mapping of basal branching habit and flowers per leaf axil in sesame. Front Plant Sci 8:636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Meng L, Li H, Zhang L, Wang J. QTL IciMapping: integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in bi-parental populations. Crop J. 2015;3:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2015.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Li C, Duan Y, Wei L, Ju M, Zhang H. Identification of a Sidwf1 gene controlling short internode length trait in the sesame dwarf mutant dw607. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s00122-019-03441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell PL, Buckler ES, Ross-Ibarra J. Crop genomics: advances and applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrg3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namiki M. Nutraceutical functions of sesame: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2007;47:651–673. doi: 10.1080/10408390600919114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slafer GA. Genetic basis of yield as viewed from a crop physiologist’s perspective. Ann Appl Biol. 2003;142:117–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2003.tb00237.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Liu D, Zhang X, Li W, Liu H, Hong W (2013) SLAF-seq: an efficient method of large-scale de novo SNP discovery and genotyping using high-throughput sequencing. PLoS One 8:e58700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Van Ooijen J (2006) JoinMap 3: Software for the calculation of genetic linkage maps in experimental populations. Kyazma BV, Wageningen

- Voorrips RE. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J Hered. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Hu S, Gardner C, Lübberstedt T. Emerging avenues for utilization of exotic germplasm. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:624–637. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Xia Q, Zhang Y, Zhu X, Zhu X, Li D, Ni X, Gao Y, Xiang H, Wei X, Yu J, Quan Z, Zhang X (2016) Updated sesame genome assembly and fine mapping of plant height and seed coat color QTLs using a new high-density genetic map. BMC Genomics 17:3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Yu S, Tong C, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Song C, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Hua W, Li D, Li D, Li F, Yu J, Xu C, Han X, Huang S, Tai S, Wang J, Xu X, Li Y, Liu S, Varshney RK, Wang J, Zhang X (2014) Genome sequencing of the high oil crop sesame provides insight into oil biosynthesis. Genome Biol 15:R39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Zhang Y, Zhu X, Zhu X, Li D, Zhang X, Gao Y, Xiao G, Wei X, Zhang X (2017b) Development of an SSR-based genetic map in sesame and identification of quantitative trait loci associated with charcoal rot resistance. Sci Rep 7:8349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wei L, Li C, Duan Y, Qu W, Wang H, Miao H, Zhang H (2019) A SNP mutation of SiCRC regulates seed number per capsule and capsule length of cs1 mutant in sesame. Int J Mol Sci 20(16):4056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wei L, Zhang H, Zheng Y, Miao H, Zhang T, Guo W (2009) A genetic linkage map construction for sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Genes Genomics 31:199–208

- Wei X, Liu K, Zhang Y, Feng Q, Wang L, Zhao Y, Li D, Zhao Q, Zhu X, Zhu X, Li W, Fan D, Gao Y, Lu Y, Zhang X, Tang X, Zhou C, Zhu C, Liu L, Zhong R, Tian Q, Wen Z, Weng Q, Han B, Huang X, Zhang X (2015) Genetic discovery for oil production and quality in sesame. Nat Commun 6:8609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wu K, Liu H, Yang M, Tao Y, Ma H, Wu W, Zuo Y, Zhao Y (2014) High-density genetic map construction and QTLs analysis of grain yield-related traits in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) based on RAD-Seq technology. BMC Plant Biol 14:274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Würschum T (2012) Mapping QTL for agronomic traits in breeding populations. Theor Appl Genet 125: 201-210 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu Y, Crouch J (2008) Marker-assisted selection in plant breeding: from publications to practice. Crop Sci 48:391–407

- Zhang H, Miao H, Li C, Wei L, Duan Y, Ma Q, Kong J, Xu F, Chang S (2016) Ultra-dense SNP genetic map construction and identification of SiDt gene controlling the determinate growth habit in Sesamum indicum L. Sci Rep 6:31556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, Miao H, Ju M. Potential for adaption to climate change through genomic breeding in sesame. In: Kole C, editor. Genomic designing of climate-smart oilseed crops. New York: Springer; 2019. pp. 371–440. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Miao H, Wang L, Qu L, Liu H, Wang Q, Yue M (2013a) Genome sequencing of the important oilseed crop Sesamum indicum L. Genome Biol 14:401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, Miao H, Wei L, Li C, Zhao R, Wang C (2013b) Genetic analysis and QTL mapping of seed coat color in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). PLoS One 8:e63898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang T, Wang B, Du Z, Mei H, Liu Y, Zheng Y. Review and prospect of sesame breeding achievements in Henan province. J Henan Agri Sci. 2017;46:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Miao H, Wei L, Li C, Duan Y, Xu F, Qu W, Zhao R, Ju M, Chang S (2018) Identification of a SiCL1 gene controlling leaf curling and capsule indehiscence in sesame via cross-population association mapping and genomic variants screening. BMC Plant Biol 18:296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhao Y, Yang M, Wu K, Liu H, Wu J, Liu K (2013) Characterization and genetic mapping of a novel recessive genic male sterile gene in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Mol Breed 32:901–908

- Zhou R, Dossa K, Li D, Yu J, You J, Wei X, Zhang X (2018) Genome-wide association studies of 39 seed yield-related traits in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Int J Mol Sci 19:2794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed information on 3,528 mapped SLAF markers (TXT 2.27 MB)

Detailed information on the genetic map (XLXS 158 KB)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Not applicable.