Highlights

-

•

Small vessel disease occurs in AD and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA).

-

•

Occipital predominant white matter hyperintensities are 1.2 times more likely in severe CAA.

-

•

Enlarged perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale are present in AD patients regardless of CAA severity.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, White matter hyperintensities, Enlarged perivascular spaces

Abstract

Background and purpose

Cerebral small vessel disease biomarkers including white matter hyperintensities (WMH), lacunes, and enlarged perivascular spaces (ePVS) are under investigation to identify those specific to cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). In subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), we assessed characteristic features and amounts of WMH, lacunes, and ePVS in four CAA categories (no, mild, moderate and severe CAA) and correlated these with Clinical Dementia Rating sum of boxes (CDRsb) score, ApoE genotype, and neuropathological changes at autopsy.

Methods

The study included patients with a clinical diagnosis of dementia due to AD and neuropathological confirmation of AD and CAA in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database. The WMH, lacunes, and ePVS were evaluated using semi-quantitative scales. Statistical analyses compared the WMH, lacunes, and ePVS values in the four CAA groups with vascular risk factors and AD severity treated as covariates, and to correlate the imaging features with CDRsb score, ApoE genotype, and neuropathological findings.

Results

The study consisted of 232 patients, of which 222 patients had FLAIR data available and 105 patients had T2-MRI. Occipital predominant WMH were significantly associated with the presence of CAA (p = 0.007). Among the CAA groups, occipital predominant WMH was associated with severe CAA (β = 1.22, p = 0.0001) compared with no CAA. Occipital predominant WMH were not associated with the CDRsb score performed at baseline (p = 0.68) or at follow-up 2–4 years after the MRI (p = 0.92). There was no significant difference in high grade ePVS in the basal ganglia (p = 0.63) and centrum semiovale (p = 0.95) among the four CAA groups. The WMH and ePVS on imaging did not correlate with the number of ApoE ε4 alleles but the WMH (periventricular and deep) correlated with the presence of infarcts, lacunes and microinfarcts on neuropathology.

Conclusion

Among patients with AD, occipital predominant WMH is more likely to be found in patients with severe CAA than in those without CAA. The high-grade ePVS in centrum semiovale were common in all AD patients regardless of CAA severity.

1. Introduction

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a cerebral small vessel disease characterized by preferential deposition of amyloid-β in the cortical and leptomeningeal blood vessels (Greenberg et al., 2020). The cerebral small vessel disease biomarkers, including white matter hyperintensities (WMH), lacunes, and enlarged perivascular spaces (ePVS), are explored to determine if their characteristic features are associated with CAA and possibly advance the diagnostic criteria for sporadic CAA (Charidimou et al., 2021, Charidimou et al., 2022, Charidimou et al., 2016, Charidimou et al., 2017, Charidimou et al., 2019, Pasi et al., 2017, Reijmer et al., 2016).

Although CAA is known to commonly present with lobar ICH, in one study, among CAA patients without symptomatic hemorrhage, transient focal neurological episodes were associated with higher WMH volumes (Boulouis et al., 2017). Thus, CAA could manifest as a distinct phenotype with cerebral small vessel disease with or without hemorrhagic features. Understanding the clinical spectrum of CAA in correlation with the imaging and neuropathological data might allow for CAA diagnosis at an earlier stage of the disease process, thereby potentially altering management and allowing for earlier interventions in this patient population.

Previous studies that compared patients with and without CAA have reported ePVS in centrum semiovale (CSO-ePVS) and lobar lacunes to be associated with CAA (Charidimou et al., 2017, Pasi et al., 2017). However, higher prevalence of CSO-ePVS has been reported in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and non-CAA related intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) (Kim et al., 2021, Tsai et al., 2021). WMH noted in AD is shown to be partly mediated by CAA pathology (Graff-Radford et al., 2019). Moreover, the presence of WMH predominantly around the occipital horn of the lateral ventricle has been associated with CAA (Zhu et al., 2012); and the WMH volume has been correlated with amyloid burden in CAA (Gurol et al., 2013). Because CAA is known to co-occur with AD pathology (Brenowitz et al., 2015, Greenberg et al., 2020, Greenberg and Vonsattel, 1997) it is essential to understand if the higher prevalence of CSO-ePVS is due to CAA pathology or from co-occurring AD pathology. The characteristic features of WMH contributed by CAA among patients with AD also needs to be evaluated.

In this study, we examined patients with a clinical diagnosis of dementia due to AD and neuropathological confirmation of AD with or without CAA in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database. We compared AD brains stratified by CAA severity on neuropathology, for characteristic features and amount of WMH and lacunes on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging (FLAIR), and ePVS on T2-weighted MRI (T2-MRI), while adjusting for vascular risk factors. We also examined the correlation of relevant imaging features with the Clinical Dementia Rating sum of boxes (CDRsb) score, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype, and neuropathological changes at autopsy.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source, standard protocol approvals, and patient consents

The study dataset was obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) after submission of a signed data use agreement (National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, 2021). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida. All contributing Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers (ADRCs) were required to obtain informed consent from their participants and to maintain their own separate IRB review and approval from their institution prior to submitting data to NACC.

2.2. Study population

Our study analyzed data from sixteen ADRCs from visits conducted between September 2005 to September 2020. Patients were included in the study if (1) a clinical diagnosis of AD was present as the primary cause of their cognitive impairment (variable NACCALZP in NACC dataset) (NACC RDD, 2015); (2) cognitive status at clinic visit was determined to be ‘Dementia’ (variable NACCUDSD); (3) AD was confirmed by neuropathology (autopsy); and (4) FLAIR and or T2-MRI were available to evaluate WMH, lacunes, and ePVS.

The diagnosis and severity of AD was recorded (variable ‘NPADNC’) using the National Institute of Aging – Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathologic Change (ADNC) ABC criteria (Besser et al., 2018, Hyman et al., 2012, NACC NP, 2014). The ABC score includes the Amyloid β plaque score, the neurofibrillary tangle stage derived from Braak, and the neuritic plaque score modified from CERAD (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease) (Hyman et al., 2012). AD was categorized as low ADNC, intermediate ADNC, and high ADNC based on the extent of neuropathological changes per the ABC criteria. Patients were excluded if they had an autopsy performed but did not have NIA-AA ADNC ABC score assessed, did not have AD, or had missing data; or if the NIA-AA ADNC ABC score was not available (prior to 2014 these data were not collected). Patients were also excluded if they did not have a FLAIR or T2-MRI available.

The semi-quantitative assessment of overall neocortical amyloid angiopathy reported in the NACC neuropathology dataset (variable NACCAMY) was based on guidelines adapted from prior studies (Olichney et al., 2000, Vonsattel et al., 1991) with additional reference to global CAA according to the following scale. Mild CAA was defined as scattered positivity in parenchymal and/or leptomeningeal vessels, possibly in only one brain area. Intense positivity in many parenchymal and leptomeningeal vessels was labelled as moderate CAA, while widespread (more than one brain area) intense positivity in parenchymal and leptomeningeal vessels was categorized as severe CAA (NACC NP, 2014).

Patients with each CAA pathologic score was considered as a distinct group. Thus, the study population with AD was categorized into four groups based on neuropathological grading for CAA – none (absent), mild, moderate, and severe.

2.3. Study data

The study data included: (1) demographics; (2) medical comorbidities; (3) CDRsb score obtained using the CDR® Dementia Staging Instrument; (4) genetic data including ApoE genotype and the number of ApoE ε4 alleles (NACC GD, 2021); and (5) neuropathological data including NIA-AA ADNC ABC score, presence of infarcts and lacunes, microinfarcts, hemorrhages and microbleeds.

The primary imaging outcomes evaluated were: (1) severity and topographical location of WMH; (2) presence of lobar or deep lacunes; and (3) severity of ePVS significantly different among the four CAA groups. The association of WMH, lacunes, and ePVS with the CDRsb score, ApoE genotype and the neuropathological changes were secondary outcomes.

2.4. Imaging protocol

MR images were obtained from 1.5 T or 3 T scanners. The FLAIR scan (n = 222) was obtained from 1.5 T MRI scanner in 110 patients and 3 T scanner in 112 patients. The T2-MRI scan (n = 105) was obtained from 1.5 T MRI scanner in 60 patients and 3 T scanner in 45 patients. Typical parameters for FLAIR were repetition time (TR) / echo time (TE) = 4550–11002/72–496, 1–5 mm thickness and 0–6 mm gap; and for T2-MRI, TR/TE = 414–6820/11–128 and 1–5 mm thickness and 1–7 mm gap.

2.5. Imaging assessment

Two investigators evaluated all FLAIR and T2-MRIs. The two raters viewed each image together and graded the WMH, lacunes, and ePVS based on consensus. If there was a disagreement in the score to be assigned, the reference articles (in section 2.5.1 and 2.5.2 below) and images for the scoring criteria were reviewed together and vetted to arrive at a score agreeable to both raters. The two investigators had a training session with a sample of 20 scans and then a testing session with a different sample of 15 scans for assessment of WMH multi-spot pattern and ePVS with Dr. Elif Gokcal, Research Fellow at J. Philip Kistler Stroke Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital. In the testing session, the weighted kappa (κ) for inter-rater reliability was very good for scoring WMH multi-spot pattern (κ = 1.00), CSO-ePVS (κ = 0.74), high-grade CSO-ePVS (κ = 1.00), BG-ePVS (κ = 0.79) and high-grade BG-eVPS (κ = 0.82). These investigators were blinded to all clinical and neuropathology data including the CAA group when the images were reviewed.

2.5.1. FLAIR assessment

White matter hyperintensities: WMH were evaluated on FLAIR sequence using the semi-quantitative Fazekas rating scale (Supplemental Fig. 1) (Kapeller et al., 2003). Deep WMH (D-WMH) on FLAIR were graded on a scale of 0–3: 0 – no lesion, 1 – punctate foci, 2 – beginning confluence of lesions, and 3 – large confluent areas (Fazekas et al., 1987, Kapeller et al., 2003). Periventricular WMH (PV-WMH) were graded on a 0–3 scale: 0 – no lesion, 1 – caps or pencil-thin lining, 2 – smooth halo, and 3 – irregular periventricular hyperintensities extending into deep white matter (Fazekas et al., 1987, Kapeller et al., 2003). A score of 2 or 3 for PV-WMH and D-WMH was considered clinically significant (Gouw et al., 2011). The total Fazekas score was the sum of scores for D-WMH and PV-WMH.

Frontal-Occipital Gradient WMH: Using a visual rating scale, WMH were evaluated in the periventricular (≤5mm from ventricle), juxtacortical (≤5mm from the cortex), and deep (between juxtacortical and ventricular region) areas separately in the frontal lobe around the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle and in the occipital lobe around the occipital horn of the lateral ventricle (Supplemental Fig. 1) (Zhu et al., 2012). PV-WMH were graded as: 0 – absent, 1 – caps or pencil-thin periventricular lining, and 2 – smooth halo or thick lining. Deep and juxtacortical WMH were graded as: 0 – absent, 1 – punctate or nodular foci, and 2 – confluent areas (Zhu et al., 2012). The frontal and occipital predominant WMH scores (range 0–6) were calculated by adding the scores for periventricular, deep, and juxtacortical areas. The frontal-occipital (FO) gradient, calculated as the WMH score in the frontal lobe minus that in the occipital lobe, gives the difference in the severity of WMH. The FO gradient ranges from −6 to 6. A score > 0 implies frontal dominance, and < 0 implies occipital dominance. Obvious frontal dominant WMH was defined as an FO gradient of ≥ 2 and obvious occipital dominant WMH as a FO gradient ≤ -2 (Zhu et al., 2012).

WMH multi-spot pattern: It refers to the presence of > 10 circular or oval spots of WMH in the subcortical white matter on FLAIR (Charidimou et al., 2016).

Lacune of presumed vascular origin: It was defined according to the Standards for Reporting Vascular Changes on Neuroimaging (STRIVE) definition as a round or ovoid, fluid-filled cavity measuring 3–15 mm in diameter (Wardlaw et al., 2013). They are hypointense on FLAIR with a surrounding rim of hyperintensity, and hypointense on T1-weighted image. The hyperintense rim on FLAIR may not always be present. It suggests previous acute small subcortical infarct or hemorrhage in the territory of a perforating arteriole (Wardlaw et al., 2013). Based on the location of the lacune, it was classified as deep (for lesions in BG, internal capsule, external capsule, thalamus, brainstem or deep cerebellar regions) or lobar (for lesions in subcortical regions including CSO, frontal, parietal, insular, temporal or occipital lobes) (Pasi et al., 2017). Lesions <3 mm in diameter were regarded as most likely ePVS and were not considered as lacunes (Wardlaw et al., 2013).

2.5.1.1. T2-weighted MRI assessment

CSO-ePVS and BG-ePVS: ePVS was defined based on the STRIVE definition as a fluid filled space that follows the typical course of a vessel as it goes through gray and white matter (Wardlaw et al., 2013). They have a signal intensity similar to CSF in all sequences. They are differentiated from lacunes based on size (<3 mm in diameter), and the spaces do not have a hyperintense rim around the fluid-filled space on T2-MRI or FLAIR unless they traverse an area of WMH (Wardlaw et al., 2013). ePVS were evaluated on axial T2-MRI in the BG and CSO using a 4-point visual rating scale: 0 = no ePVS, 1= ≤10 ePVS, 2 = 11–20 ePVS, 3 = 21–40 ePVS and 4 = >40 ePVS (Supplemental Fig. 2) (Potter et al., 2015; EPVS, 2023). High grade ePVS was defined as ePVS score > 2 (Charidimou et al., 2017). The slice and the hemisphere with the highest number of ePVS was chosen after reviewing all the relevant slices in CSO and BG. If there were confluent WMH, then ePVS was rated on the non-involved white matter region. In the presence of confluent WMH, an estimation was made of the closest ePVS rating category (Charidimou et al., 2017).

2.6. Covariates

Six covariates were included for multivariable regression and partial Spearman correlation analyses: age (at the time of MRI), sex, AD severity (ADNC ABC score), and traditional risk factors for small vessel disease such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. AD severity was added as a covariate as it was significantly different between the four CAA groups with the severe CAA group having more patients with high ADNC.

2.7. Statistical methods

Baseline demographic and clinical data were compared among the four CAA groups. Categorical data were reported as percentages and analyzed by Chi-square test. Continuous variables were reported as mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile range and analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA).

To evaluate the small vessel disease imaging features in CAA, ordinal variables including PV-WMH, D-WMH, total Fazekas score, frontal predominant WMH, occipital predominant WMH, FO gradient, CSO-ePVS and BG-ePVS were compared by non-parametric one-way ANOVA - Kruskal-Wallis Test; categorical variables including obvious frontal dominant WMH, obvious occipital dominant WMH, WMH multi-spot pattern, lacunes, and high grade ePVS (score 3 or 4) were compared with Chi-square test.

Linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate for the differences in the occipital predominant WMH among the four CAA groups with six predetermined covariates. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple group comparisons.

The progression of CDRsb scores were assessed in three-year blocks. The CDRsb score performed in the same year (±1 year) as the MRI was considered the baseline CDRsb score. Follow-up CDRsb scores were assessed 2–4 years after the MRI. More than one CDRsb score within each three-year block due to multiple clinic visits were averaged within that 3-year block. Linear regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association of occipital predominant WMH with the CDRsb score (at baseline and at 2–4 years after the MRI).

Partial Spearman correlation, adjusting for covariates, was performed to test the association of WMH and ePVS with the number of ApoE ε4 alleles. Patients were excluded from analyses if they had missing data for the number of ApoE ε4 alleles (n = 13 and 7 missing for correlation with WMH on FLAIR, and ePVS on T2-MRI, respectively), and the neuropathological data (n = 3 missing for assessment of WMH and lacunes on FLAIR). All patients had neuropathological data for correlation with ePVS on T2-MRI. Associations between pertinent imaging features and the neuropathological data were examined by chi-squared tests.

To evaluate the effect of MRI scanner strength, secondary analysis of WMH, lacunes and ePVS were performed separately for patients scanned with 1.5 T and 3 T scanner. Because prior studies defined clinical diagnosis of CAA in those with moderate and severe CAA pathology and mild degree of CAA may not have significant imaging manifestations, we also analyzed data comparing combined none-mild CAA vs moderate-severe CAA pathology.

The analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

2.8. Data availability

The study dataset was obtained from NACC and is publicly available (https://naccdata.org/). All of the data analyzed for this study are reported in this manuscript.

3. Results

A total of 404 patients with a primary diagnosis of AD at their last clinic visit, had at least one MRI during the study period, and an autopsy performed at death, were screened for the study. One hundred and forty-six patients were excluded for neuropathological reasons (such as lack of ADNC ABC score, not assessed for AD or CAA), and 26 patients were excluded for lack of FLAIR or T2-MRI (Fig. 1). The final study population consisted of 232 patients: 222 patients had FLAIR and 105 patients had T2-MRI. Among these ninety-five patients had FLAIR and T2-MRI, 127 had only FLAIR, and 10 had only T2-MRI.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patients eligible for the study.

3.1. Baseline characteristics

3.1.1. FLAIR cohort

Compared to patients without CAA, those with severe CAA were younger at the time of MRI (81 ± 9 vs 75 ± 9 years, p = 0.007), at time of last clinic visit (83 ± 9 vs 76 ± 10 years, p = 0.002), and at death (86 ± 9 vs 80 ± 10 years, p = 0.006) (Table 1). There were no significant differences in sex, race, ethnicity, or medical history among the four CAA groups. Patients with severe CAA had a higher CDRsb score compared to patients without CAA (p = 0.03). The presence of 2 copies of ApoE ε4 alleles were positively correlated with an increase in the severity of CAA – 0, 5, 20 and 26% among patients with no, mild, moderate, and severe CAA, respectively (Table 1). The number of patients with severe AD on neuropathology (high ADNC) increased in conjunction with the increase in severity of CAA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

|

All patients with FLAIR (N = 222) |

P value |

All patients with T2-MRI (N = 105) |

P value |

Patients with FLAIR and T2 (N = 95) |

P value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No CAA N = 40 |

Mild CAA N = 61 |

Moderate CAA N = 74 |

Severe CAA N = 47 |

No CAA N = 24 |

Mild CAA N-24 |

Moderate CAA N = 33 |

Severe CAA N = 24 |

No CAA N = 22 |

Mild CAA N-22 |

Moderate CAA N = 30 |

Severe CAA N = 21 |

||||

| Demographics | |||||||||||||||

| Age at latest MRI, years, mean (SD) | 81 (9) | 77 (9) | 77 (9) | 75 (9) | 0.007* | 79 (9) | 75 (10) | 76 (10) | 76 (8) | 0.34 | 78 (9) | 75 (10) | 77 (10) | 76 (8) | 0.67 |

| Age at last clinic visit, years, mean (SD) | 83 (9) | 79 (9) | 79 (9) | 76 (10) | 0.002* | 82 (8) | 78 (11) | 79 (10) | 78 (7) | 0.19 | 81 (8) | 78 (11) | 79 (10) | 78 (7) | 0.47 |

| Age at death, years, mean (SD) | 86 (9) | 82 (9) | 83 (9) | 80 (10) | 0.006* | 84 (9) | 81 (11) | 82 (10) | 80 (7) | 0.21 | 84 (9) | 81 (11) | 83 (10) | 80 (7) | 0.41 |

| Time from MRI to death, years, mean (SD) | 5 (3) | 5 (2) | 6 (3) | 5 (3) | 0.64 | 5 (2) | 6 (3) | 6 (2) | 4 (3) | 0.28 | 5 (2) | 5 (3) | 6 (2) | 4 (3) | 0.10 |

| Female, n (%) | 18 (45) | 28 (46) | 35 (47) | 18 (38) | 0.80 | 6 (25) | 8 (33) | 17 (52) | 6 (25) | 0.11 | 6 (27) | 8 (36) | 14 (47) | 5 (24) | 0.31 |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||||||||||

| White | 38 (95) | 56 (92) | 71 (96) | 44 (94) | 0.79 | 24 (100) | 23 (96) | 33 (100) | 24 (100) | 0.33 | 22 (100) | 21 (95) | 30 (100) | 21 (100) | 0.34 |

| Black | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 2 (3) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Asian | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Hispanic, n (%) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 5 (7) | 3 (6) | 0.07 | 4 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 2 (8) | 0.18 | 4 (18) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | 2 (10) | 0.18 |

| Education > 12 years, n (%) | 28 (70) | 41 (70) | 60 (81) | 36 (77) | 0.39 | 20 (83) | 15 (63) | 30 (91) | 21 (88) | 0.04* | 18 (82) | 14 (64) | 27 (90) | 18 (86) | 0.10 |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 25 (63) | 42 (69) | 45 (61) | 22 (47) | 0.14 | 14 (58) | 15 (63) | 17 (52) | 10 (42) | 0.49 | 14 (64) | 15 (68) | 15 (50) | 7 (33) | 0.09 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (18) | 6 (10) | 7 (9) | 1 (2) | 0.11 | 3 (13) | 1 (4) | 3 (9) | 1 (4) | 0.63 | 3 (14) | 1 (5) | 3 (10) | 1 (5) | 0.64 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 26 (65) | 37 (61) | 45 (61) | 31 (66) | 0.91 | 19 (79) | 11 (46) | 20 (61) | 17 (71) | 0.09 | 18 (82) | 11 (50) | 19 (63) | 14 (67) | 0.17 |

| Smoked > 100 cigarettes in life | 18 (45) | 27 (44) | 34 (46) | 25 (53) | 0.80 | 11 (46) | 11 (46) | 13 (39) | 12 (50) | 0.88 | 10 (45) | 11 (50) | 12 (40) | 12 (57) | 0.67 |

| Heart attack / cardiac arrest | 2 (5) | 5 (8) | 11 (15) | 3 (6) | 0.25 | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 5 (15) | 1 (4) | 0.39 | 2 (9) | 1 (5) | 5 (17) | 1 (5) | 0.39 |

| Stroke | 3 (8) | 7 (11) | 5 (7) | 2 (4) | 0.55 | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.70 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.71 |

| CDRsb score, mean ± SD | |||||||||||||||

| At baseline, 0 ± 1 year after MRI† | 5.6 (4.3) | 6.3 (4.3) | 6.1 (5.0) | 7.4 (5.4) | 0.03* | 6.3 (4.2) | 6.8 (4.3) | 6.9 (4.8) | 8.0 (5.3) | 0.08 | 6.9 (4.0) | 7.3 (4.2) | 6.9 (4.8) | 7.9 (5.1) | 0.46 |

| At follow-up, 2–4 years after MRI†† | 9.8 (5.1) | 9.9 (5.2) | 9.0 (5.3) | 9.1 (5.7) | 0.23 | 10 (5.1) | 9.7 (4.7) | 10.1 (5.0) | 9.5 (4.7) | 0.75 | 11.2 (4.7) | 10.7 (4.9) | 11.1 (4.8) | 10.2 (4.8) | 0.52 |

| Genetic data | |||||||||||||||

| ApoE Genotype, n (%) | |||||||||||||||

| ε3, ε3 | 26 (65) | 22 (36) | 12 (16) | 16 (34) | <0.0001* | 14 (58) | 9 (38) | 2 (6) | 9 (38) | 0.0006* | 14 (64) | 8 (36) | 2 (7) | 9 (43) | 0.0005* |

| ε3, ε4 | 11 (28) | 29 (48) | 32 (43) | 18 (38) | 7 (29) | 12 (50) | 13 (39) | 6 (25) | 6 (27) | 12 (55) | 12 (40) | 5 (24) | |||

| ε3, ε2 | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| ε4, ε4 | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 15 (20) | 12 (26) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 9 (27) | 8 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 8 (27) | 6 (29) | |||

| ε4, ε2 | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 6 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 4 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (13) | 0 (0) | |||

| Missing | 1 (3) | 4 (7) | 7 (9) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 4 (12) | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 4 (13) | 1 (5) | |||

| Number of ApoE ε4 alleles, n (%) | |||||||||||||||

| No copy of ε4 allele | 28 (70) | 23 (38) | 14 (19) | 16 (34) | <0.0001* | 16 (67) | 9 (38) | 3 (9) | 9 (38) | 0.0002* | 15 (68) | 8 (36) | 2 (7) | 9 (43) | 0.0004* |

| 1 copy of ε4 allele | 11 (28) | 31 (51) | 38 (51) | 18 (38) | 7 (29) | 13 (54) | 17 (52) | 6 (25) | 6 (27) | 12 (55) | 16 (53) | 5 (24) | |||

| 2 copies of ε4 allele | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 15 (20) | 12 (26) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 9 (27) | 8 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 8 (27) | 6 (29) | |||

| Missing | 1 (3) | 4 (7) | 7 (9) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 4 (12) | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 4 (13) | 1 (5) | |||

| Neuropathological data | |||||||||||||||

| NIA-AA ADNC ABC score, n (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Low ADNC | 4 (10) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 0.02* | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.057 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.17 |

| Intermediate ADNC | 11 (28) | 10 (16) | 11 (15) | 2 (4) | 9 (38) | 4 (17) | 6 (18) | 1 (4) | 7 (32) | 3 (14) | 6 (20) | 1 (5) | |||

| High ADNC | 25 (63) | 49 (80) | 61 (82) | 44 (94) | 15 (62) | 19 (79) | 27 (82) | 23 (96) | 15 (68) | 18 (82) | 24 (80) | 20 (95) | |||

| Infarcts and lacunes, n (%) | 4 (10) | 14 (24)‡ | 7 (9) | 5 (11)¶ | 0.07 | 2 (8) | 6 (25) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.04 | 2 (9) | 6 (27) | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.04 |

| Microinfarcts, n (%) | 14 (35) | 19 (32)‡ | 12 (16) | 9 (20) ¶ | 0.06 | 6 (25) | 5 (21) | 6 (18) | 4 (17) | 0.89 | 6 (27) | 5 (23) | 5 (17) | 4 (19) | 0.81 |

| Hemorrhages and microbleeds, n (%) | 3 (8) | 5 (8) ‡ | 11 (15) | 8 (17) ¶ | 0.36 | 3 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 3 (13) | 0.29 | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | 2 (10) | 0.54 |

†n = 38, 58, 69 and 46 in FLAIR group; n = 22,23,29 and 22 in T2-MRI group; and n = 20, 21, 26 and 20 in FLAIR and T2 group for no, mild, moderate and severe CAA respectively for assessment of CDRsb scores.

††n = 33, 47, 54 and 31 in FLAIR group; n = 23,21, 31 and 18 in T2-MRI group; and n = 21, 19, 28 and 15 in FLAIR and T2 group for no, mild, moderate and severe CAA respectively for assessment of CDRsb scores.

‡n = 59 in mild CAA group and ¶n = 46 in severe CAA groups for assessment of neuropathology data.

*Indicates significant p values < 0.05.

ADNC = Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathologic Change; NIA-AA = National Institute of Aging – Alzheimer’s Association; CDRsb = Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes; SD = Standard Deviation.

3.1.2. T2W-MRI cohort

There were no significant differences in the demographics, medical history, and the CDRsb scores among the four CAA groups, with the exception of education > 12 years, which was lower in patients with mild CAA group (p = 0.04). Similar to the FLAIR cohort, patients with severe CAA were more likely to have 2 copies of ApoE ε4 alleles (p = 0.0002). There were no significant differences in AD severity by neuropathology among the four CAA groups. Patients who had both FLAIR and T2W-MRI scans (n = 95) had characteristics comparable to all T2W-MRI patients except that education > 12 years was not significant.

3.2. Assessment of WMH, lacunes and ePVS

There were no significant differences in PV-WMH, D-WMH, or total Fazekas score among the four CAA groups (Table 2). Patients with severe CAA were more likely to have higher occipital predominant WMH (p = 0.007), lower FO gradient score (p = 0.009), and less obvious frontal dominant WMH (p = 0.02, Table 2). Patients with FLAIR and T2W-MRI scans had comparable results except for the obvious frontal dominant WMH that showed only a trend and was not significant (p = 0.08). Secondary analysis stratified by MRI scanner strength (1.5 T and 3 T) showed similar results of higher occipital predominant WMH (1.5 T p = 0.046, 3 T p = 0.049) and lower FO gradient score (1.5 T p = 0.04, 3 T p = 0.03) among patients with severe CAA (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Small vessel disease characteristics in AD stratified by none, mild, moderate and severe CAA groups.

|

All patients with FLAIR (N = 222) |

P value |

All patients with T2-MRI (N = 105) |

P value |

Patients with FLAIR and T2 (N = 95) |

P value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No CAA N = 40 |

Mild CAA N = 61 |

Moderate CAA N = 74 |

Severe CAA N = 47 |

No CAA N = 24 |

Mild CAA N-24 |

Moderate CAA N = 33 |

Severe CAA N = 24 |

No CAA N = 22 |

Mild CAA N-22 |

Moderate CAA N = 30 |

Severe CAA N = 21 |

||||

| Fazekas score | |||||||||||||||

| Periventricular WMH (score 0–3), mean (SD) |

1.6 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.9) | 0.11 | – | – | – | – | – | 1.6 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.9) | 0.11 |

| Deep WMH (score 0–3),mean (SD) |

1.5 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.7 (1.0) | 0.15 | – | – | – | – | – | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.9) | 0.32 |

| Total Fazekas score (0–6),mean (SD) |

3.1 (1.6) | 3.5 (1.5) | 3.0 (1.5) | 3.7 (1.8) | 0.17 | – | – | – | – | – | 3.0 (1.5) | 3.8 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.8) | 0.19 |

| Frontal-Occipital Gradient | |||||||||||||||

| Frontal Predominant WMH (score 0–6), mean (SD) |

3.0 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.5) | 0.93 | – | – | – | – | – | 3.0 (1.5) |

3.0 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.7) | 3.3 (1.5) | 0.94 |

| Occipital Predominant WMH (score 0–6), mean (SD) |

2.0 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.6) | 0.007* | – | – | – | – | – | 2.0 (1.2) |

2.8 (1.5) | 2.4 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.5) | 0.017* |

| Frontal-Occipital Gradient Score(-6 to 6), mean (SD) |

1.0 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.3) | 0.9 (1.2) | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.009* | – | – | – | – | – | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.2 (1.3) | 0.7 (1.3) | −0.1 (1.2) | 0.01* |

| Obvious Frontal Dominant WMH (FO gradient ≥ 2), n (%) |

14 (35) | 22 (36) | 24 (32) | 5 (11) | 0.02* | – | – | – | – | – | 8 (36) | 5 (23) | 9 (30) | 1 (5) | 0.08 |

| Obvious Occipital Dominant WMH (FO gradient ≤ -2), n (%) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) | 5 (7) | 4 (9) | 0.50 | – | – | – | – | – | 0 (0) | 2 (9) | 2 (7) | 2 (10) | 0.54 |

| WMH Multi-spot pattern, n (%) | 19 (48) | 32 (52) | 30 (41) | 24 (51) | 0.52 | – | – | – | – | – | 10 (45) | 10 (45) | 14 (47) | 13 (62) | 0.64 |

| Lacunes | |||||||||||||||

| Lobar lacunes, n (%) | 5 (13) | 12 (20) | 9 (12) | 12 (26) | 0.21 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 (9) | 5 (23) | 6 (20) | 7 (33) | 0.28 |

| Deep lacunes, n (%) | 7 (18) | 7 (11) | 12 (16) | 10 (21) | 0.58 | – | – | – | – | – | 4 (18) | 2 (9) | 4 (13) | 5 (24) | 0.57 |

| Enlarged Perivascular Spaces (ePVS) | |||||||||||||||

| Centrum semiovale ePVS (score 0–4), mean (SD) |

– | – | – | – | – | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.6 (1.0) | 0.90 | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.9) | 0.51 |

| Basal ganglia ePVS, (score 0–4), mean (SD) |

– | – | – | – | – | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.6) | 0.90 | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.6) | 0.78 |

| High grade centrum semiovale ePVS, n (%) | – | – | – | – | – | 13 (54) | 15 (63) | 19 (58) | 14 (58) | 0.95 | 11 (50) | 14 (64) | 17 (57) | 14 (67) | 0.68 |

| High grade basal ganglia ePVS,n (%) |

– | – | – | – | – | 4 (17) | 4 (17) | 7 (21) | 2 (8) | 0.63 | 3 (14) | 4 (18) | 7 (23) | 2 (10) | 0.59 |

WMH = White matter hyperintensities; FO = Frontal-Occipital; *P value < 0.05; SD = Standard Deviation; High grade ePVS = ePVS score 3 and 4.

On linear regression with covariates adjusted, occipital predominant WMH was associated significantly with CAA (p = 0.0005). When examined within the CAA groups, occipital predominant WMH was significantly higher in patients with severe CAA (β = 1.22, p = 0.0001) but not in moderate (p = 0.26) or mild CAA (p = 0.09) compared with no CAA (Supplemental Table 2). We also observed that the occipital predominant WMH on imaging was not significantly influenced by AD severity defined by neuropathology in the adjusted regression analysis (Supplemental Table 2).

There were no significant differences in the WMH multi-spot pattern, lacunes, CSO-ePVS, and BG-ePVS among the four CAA groups (Table 2). Secondary analysis of data with two CAA groups — none-mild CAA vs moderate-severe CAA —did not show the significance for occipital predominant WMH and FO gradient score (Supplemental Table 3) although it was significant in primary analysis with four CAA groups. The WMH multispot pattern, lacunes and ePVS remained non-significant.

3.3. Imaging - clinical correlation

With linear regression adjusted for covariates, occipital predominant WMH was not significantly associated with the mean CDRsb score at baseline (mean = 6.3, β = 0.006, p = 0.68) or follow-up 2–4 years after the MRI (mean = 9.4, β = 0.001, p = 0.92). FO gradient, however, was significantly associated with the mean CDRsb score at baseline (β = 0.03; p = 0.02) and at follow-up 2–4 years after the MRI (β = 0.04; p = 0.003).

3.4. Association of WMH, lacunes, and ePVS with ApoE genotype

With partial Spearman correlation adjusted for covariates, the total Fazekas score, FO gradient, occipital predominant WMH, and ePVS in the CSO and BG did not significantly correlate with the number of ApoE ε4 alleles across all CAA groups (Supplemental Table 4).

3.5. Imaging – neuropathological correlation

Presence of infarcts and lacunes on neuropathology were significantly associated with more PV-WMH (p = 0.02), D-WMH (p = 0.004) and BG-ePVS (p = 0.002) on imaging. Microinfarcts on neuropathology were associated with more PV-WMH (p = 0.004), D-WMH (p = 0.002) and lobar lacunes (p = 0.0002) on imaging (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6). Hemorrhages and microbleeds on neuropathology were not significantly associated with WMH, lacunes or ePVS (Fig. 4, Supplemental Table 5 and 6).

4. Discussion

We investigated whether a characteristic small vessel disease biomarker was associated with CAA among patients with AD. Our study showed that (1) occipital predominant WMH is on average 1.2 times higher in patients with severe CAA than those without CAA; (2) the CDRsb score was not significantly associated with the occipital predominant WMH; and (3) there were no differences among the CSO-ePVS between CAA groups.

Prior studies have shown that the WMH noted in AD is partly mediated by CAA pathology (Graff-Radford et al., 2019, Lee et al., 2018) and that WMH volume is associated with the amyloid burden in CAA (Gurol et al., 2013). In a prior study, patients with lobar intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) clinically diagnosed as possible or probable CAA based on the Boston criteria (Greenberg and Charidimou, 2018) were more likely to have obvious occipital dominant WMH compared with healthy controls (13.7% vs 5.7%, p = 0.03) (Zhu et al., 2012). In our study, we investigated whether there was a relationship between the severity of CAA on neuropathology and the WMH on MRI among patients with AD. We found that as the severity of CAA increased, so too was there an increase in the occipital predominant WMH, a lower FO gradient, and less obvious frontal dominant WMH, on MRIs performed about 5 years prior to death. The MRI scanner strength (1.5 T and 3 T) did not influence the significant results for higher occipital predominant WMH and a lower FO gradient score. We did not find a difference in obvious occipital dominant WMH. The finding of significant occipital dominant WMH noted in a prior study is likely due to severe CAA with symptomatic lobar hemorrhage in that study population (Zhu et al., 2012). Seventeen patients in our study who had FLAIR scans had a history of stroke, but it is unclear how many of these patients had ICH. Therefore, our study cohort was likely comprised of predominantly non-hemorrhage patients. It is likely possible that there is a gradual transition from obvious frontal dominant WMH to occipital predominant WMH as AD patients shift from having no CAA to severe CAA. This transition feature in WMH could potentially be an early non-hemorrhagic imaging biomarker of severe CAA among patients with AD.

Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), a complication of anti-amyloid β antibody therapy for AD, is more likely to occur in presence of ApoE ε4 genotype and pretreatment microbleeds suggestive of CAA (Cogswell et al., 2022). The edema form of ARIA (ARIA-E) commonly affects the occipital lobes followed by parietal lobes and then frontal and temporal lobes (Cogswell et al., 2022, Sperling et al., 2011). In the absence of lobar microbleeds as a risk factor for ARIA, weather the presence of occipital predominant WMH (associated with severe CAA) predisposes to ARIA-E with anti-amyloid antibody therapies needs further investigation.

The recently published Boston criteria version 2.0 includes WMH multi-spot pattern and CSO-ePVS as non-hemorrhagic imaging features specific to CAA (Charidimou et al., 2022). We did not find a significant difference for these imaging features when evaluated among four independent CAA groups and combined none-mild vs moderate-severe CAA groups. Potential reasons for non-significant results for WMH multi-spot pattern include the following. About two-third patients in our study had high resolution FLAIR with 1–3 mm thickness that may have shown more lesions than the conventional 4–5 mm thick FLAIR images. All of our study patients had AD pathology. Also we analyzed the last MRI that was performed prior to death and 80% of our cohort had severe AD (high ADNC) at autopsy. These factors might have also accounted for slightly higher prevalence of WMH multi-spot pattern in our study (range 41–52%) compared to lower prevalence among patients with CAA in prior studies (range 29.8 to 44%) (Charidimou et al., 2022, Charidimou et al., 2016).

Because 48% of the patients with AD also have CAA pathology (Brenowitz et al., 2015, Greenberg et al., 2020, Greenberg and Vonsattel, 1997, Jakel et al., 2022), it is crucial to understand if the CSO-ePVS noted in prior CAA studies were due to CAA pathology, AD pathology, combination of both or other etiologies. Prior studies have reported association of high-grade CSO-ePVS with (1) CAA-related ICH (Charidimou et al., 2017), (2) sporadic neuropathology confirmed CAA with lobar hemorrhage on MRI (Charidimou et al., 2022, Charidimou et al., 2014, Martinez-Ramirez et al., 2018), (3) Dutch type-hereditary CAA mutation carriers (Martinez-Ramirez et al., 2018), and (4) higher amyloid burden on Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging (Charidimou et al., 2015, Tsai et al., 2021). Further, the degree of ePVS in the juxtacortical areas on post-mortem 7 T MRI was associated with the severity of CAA on neuropathology (van Veluw et al., 2016). However, an Asian cohort study, reported CSO-ePVS to be highly prevalent in both CAA-related ICH and non-CAA ICH and it is was associated with higher amyloid burden (Tsai et al., 2021).

High degree of white matter ePVS has been associated with lobar cerebral microbleeds among cognitively impaired patients (MCI and AD) (Martinez-Ramirez et al., 2013). Studies that have evaluated the association of CSO-ePVS with clinically diagnosed AD have yielded conflicting results (Banerjee et al., 2017, Gertje et al., 2021, Kim et al., 2021). The severity of CSO-ePVS was associated with a clinical diagnosis of AD (n = 110) (Banerjee et al., 2017) and amyloid burden on PET imaging in AD (n = 144) (Kim et al., 2021). However, there was no difference in the CSO-ePVS in a smaller study of 39 AD patients with matched 78 controls (Gertje et al., 2021). These studies suggest that the CSO-ePVS are observed in CAA patients without AD (such as Dutch-type hereditary CAA), and CAA with AD. Our study was limited by lack of ‘CAA alone without AD’ group but we found that CSO-ePVS was present in AD without CAA that was not different than other CAA groups. It is likely possible that the high grade CSO-ePVS is mediated by CAA pathology and probably other factors such as AD pathology or APOE that is not yet fully understood and needs to be further studied.

We found higher prevalence of CSO-ePVS (54–63%) compared to other studies that reported about 44–48% (Charidimou et al., 2022, Charidimou et al., 2017, Tsai et al., 2021) and it was not associated with CAA unlike prior studies. High grade CSO-ePVS has been found to be independently associated with older age and predict higher risk of diagnostic conversion from mild cognitive impairment to AD (Na et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2022). It is likely possible that the CSO-ePVS increases with increase in severity of AD. These factors could have contributed to the higher prevalence of CSO ePVS observed on last MRI performed prior to death in our cohort of older AD patients with 80% high grade ADNC pathology. The CSO-ePVS remained non-significant when the data was analyzed with none-mild vs moderate-severe CAA groups. The reason for this lack of significance is not unknown but the higher prevalence of CSO-ePVS with likely ceiling effect could have obscured any difference among the CAA groups. To study this further, we plan to evaluate earlier MRI scans with longitudinal follow-up until last MRI before death across the CAA groups.

WMH volume is well known to be associated with cognitive decline (Alber et al., 2019, Prins and Scheltens, 2015). Similarly, we found that the total WMH burden measured as a gradient between frontal and occipital lobe (FO gradient) was significantly associated with cognitive impairment at baseline and at follow-up 2–4 years after the MRI. However, a specific pattern of WMH predominantly involving the occipital lobe was not associated with cognitive decline.

An association of ApoE ε4 genotype with higher WMH volume has been reported (Lyall et al., 2020, Rojas et al., 2018, Sudre et al., 2017). However, in our study, the total Fazekas score and the frontal occipital gradient were not associated with ApoE ε4 alleles when adjusted for covariates. Only 30 patients (13%) in our study population had two copies of the ApoE ε4 allele and nearly one third of patients did not have an ApoE ε4 allele. These factors may have contributed to the lack of association between WMH and ApoE ε4 genotype.

Imaging assessment of WMH and ePVS in patients with pathological confirmation of AD +/-CAA is a major strength of our study; it showed good correlation of WMH and BG-ePVS on imaging with infarcts, lacunes, and microinfarcts on neuropathology. These correlations with neuropathology strengthen our neuroimaging assessment of WMH and ePVS. The study cohort included predominantly patients with high ADNC on neuropathological assessment, thus, AD severity was included as a covariate in the multivariate analysis to avoid confounding. We also observed that the occipital predominant WMH was not statistically different among the three AD groups.

Our study limitations include the lack of a cohort of CAA without AD, which would have helped to determine whether the WMH and ePVS was due to AD pathology, CAA pathology, or both. The study had fewer patients with T2-MRI data available (compared to FLAIR), although they were evenly distributed among the CAA groups. The visualization and rating of WMH, lacunes and ePVS might have been affected by the differences in FLAIR and T2-MRI sequence acquisition parameters used at 16 ADRCs. The WMH, lacunes, and ePVS were evaluated by a vascular neurologist and a neuroradiologist, using a semiquantitative scale, and their conclusions were based on consensus. Further studies with automated quantitative assessment of WMH and ePVS are needed to confirm our findings. T2*-weighted images were not available to assess for hemorrhagic features of CAA (cerebral microbleeds, cortical superficial siderosis, convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage and lobar intracerebral hemorrhage) based on Boston Criteria and correlate with the CAA neuropathological grading.

5. Conclusion

Among patients with AD, occipital predominant WMH is more likely to be found in patients with severe CAA than in those without CAA. The CSO-ePVS are common in all patients with AD regardless of the severity of CAA.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nandakumar Nagaraja: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Steven DeKosky: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Ranjan Duara: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Lan Kong: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Wei-en Wang: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. David Vaillancourt: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Mehmet Albayram: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U24 AG072122. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG066546 (PI Sudha Seshadri, MD), P20 AG068024 (PI Erik Roberson, MD, PhD), P20 AG068053 (PI Marwan Sabbagh, MD), P20 AG068077 (PI Gary Rosenberg, MD), P20 AG068082 (PI Angela Jefferson, PhD), P30 AG072958 (PI Heather Whitson, MD), P30 AG072959 (PI James Leverenz, MD).

The authors would like to thank Dr. Steven Greenberg, Professor of Neurology and Dr. Elif Gokcal, Research Fellow at J. Philip Kistler Stroke Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital for assistance with harmonizing our scoring for WMH multi-spot pattern and ePVS.

Funding

This work was supported by the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center National Institutes of Health Grant (P30AG066506); and McJunkin Family Foundation Alzheimer’s Disease Fund.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2023.103437.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

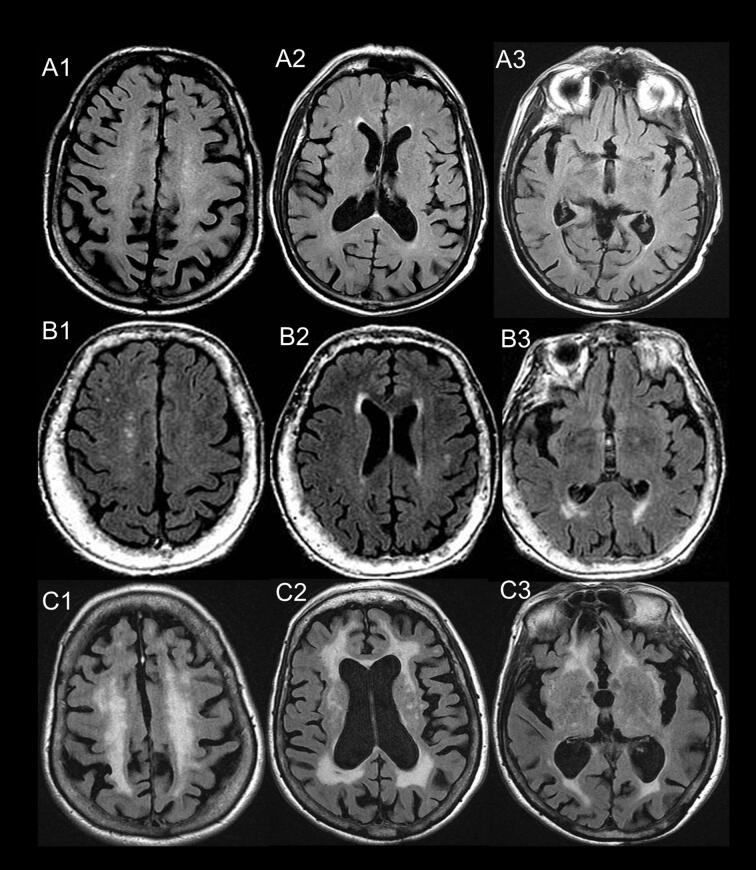

Supplementary figure 1.

Fazekas and frontal-occipital gradient assessment. Scoring of three subjects (A, B, and C) based on review of multiple slices. Fazekas score: D-WMH / PV-WMH: 1/1 (A1/A2), 1/2 (B1/B2) and 3/3 (C1/C2). Frontal-occipital gradient: (1) Frontal horn of lateral ventricle: A2=1/1/0; B2=2/1/0; and C2=2/2/2 for PV-WMH / D-WMH / Juxtacortical WMH, respectively. (2) Occipital horn of lateral ventricle: A3=1/0/0, B3=2/2/1, and C3=2/2/1 for PV-WMH / D-WMH / Juxtacortical WMH respectively. Patient B has occipital predominant WMH.

Supplementary figure 2.

Enlarged perivascular spaces. (A) centrum semiovale, grade 4: >40 ePVS; and (B) basal ganglia, grade 3: 21-40 ePVS.

Data availability

The dataset was obtained from NACC that is publicly available

References

- Alber J., Alladi S., Bae H.J., Barton D.A., Beckett L.A., Bell J.M., Berman S.E., Biessels G.J., Black S.E., Bos I., Bowman G.L., Brai E., Brickman A.M., Callahan B.L., Corriveau R.A., Fossati S., Gottesman R.F., Gustafson D.R., Hachinski V., Hayden K.M., Helman A.M., Hughes T.M., Isaacs J.D., Jefferson A.L., Johnson S.C., Kapasi A., Kern S., Kwon J.C., Kukolja J., Lee A., Lockhart S.N., Murray A., Osborn K.E., Power M.C., Price B.R., Rhodius-Meester H.F.M., Rondeau J.A., Rosen A.C., Rosene D.L., Schneider J.A., Scholtzova H., Shaaban C.E., Silva N., Snyder H.M., Swardfager W., Troen A.M., van Veluw S.J., Vemuri P., Wallin A., Wellington C., Wilcock D.M., Xie S.X., Hainsworth A.H. White matter hyperintensities in vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID): Knowledge gaps and opportunities. Alzheimers Dement. (N Y) 2019;5:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee G., Kim H.J., Fox Z., Jager H.R., Wilson D., Charidimou A., Na H.K., Na D.L., Seo S.W., Werring D.J. MRI-visible perivascular space location is associated with Alzheimer's disease independently of amyloid burden. Brain. 2017;140:1107–1116. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser L.M., Kukull W.A., Teylan M.A., Bigio E.H., Cairns N.J., Kofler J.K., Montine T.J., Schneider J.A., Nelson P.T. The revised national Alzheimer's coordinating center's neuropathology form-available data and new analyses. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2018;77:717–726. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nly049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulouis G., Charidimou A., Jessel M.J., Xiong L., Roongpiboonsopit D., Fotiadis P., Pasi M., Ayres A., Merrill M.E., Schwab K.M., Rosand J., Gurol M.E., Greenberg S.M., Viswanathan A. Small vessel disease burden in cerebral amyloid angiopathy without symptomatic hemorrhage. Neurology. 2017;88:878–884. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz W.D., Nelson P.T., Besser L.M., Heller K.B., Kukull W.A. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its co-occurrence with Alzheimer's disease and other cerebrovascular neuropathologic changes. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:2702–2708. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A., Jaunmuktane Z., Baron J.C., Burnell M., Varlet P., Peeters A., Xuereb J., Jager R., Brandner S., Werring D.J. White matter perivascular spaces: an MRI marker in pathology-proven cerebral amyloid angiopathy? Neurology. 2014;82:57–62. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000438225.02729.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A., Hong Y.T., Jager H.R., Fox Z., Aigbirhio F.I., Fryer T.D., Menon D.K., Warburton E.A., Werring D.J., Baron J.C. White matter perivascular spaces on magnetic resonance imaging: marker of cerebrovascular amyloid burden? Stroke. 2015;46:1707–1709. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A., Boulouis G., Haley K., Auriel E., van Etten E.S., Fotiadis P., Reijmer Y., Ayres A., Vashkevich A., Dipucchio Z.Y., Schwab K.M., Martinez-Ramirez S., Rosand J., Viswanathan A., Greenberg S.M., Gurol M.E. White matter hyperintensity patterns in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive arteriopathy. Neurology. 2016;86:505–511. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A., Boulouis G., Pasi M., Auriel E., van Etten E.S., Haley K., Ayres A., Schwab K.M., Martinez-Ramirez S., Goldstein J.N., Rosand J., Viswanathan A., Greenberg S.M., Gurol M.E. MRI-visible perivascular spaces in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive arteriopathy. Neurology. 2017;88:1157–1164. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A., Frosch M.P., Salman R.-S., Baron J.-C., Cordonnier C., Hernandez-Guillamon M., Linn J., Raposo N., Rodrigues M., Romero J.R., Schneider J.A., Schreiber S., Smith E.E., van Buchem M.A., Viswanathan A., Wollenweber F.A., Werring D.J., Greenberg S.M. Advancing diagnostic criteria for sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy: Study protocol for a multicenter MRI-pathology validation of Boston criteria v2.0. Int. J. Stroke. 2019;14(9):956–971. doi: 10.1177/1747493019855888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A., Boulouis G., Frosch M., Baron J., Pasi M., van Buchem M., Gurol E., Viswanathan A., Al-Shahi Salman R., Smith E.E., Werring D.J., Greenberg S.A. The Boston criteria V2.0 for cerebral amyloid angiopathy: Updated criteria and multicenter MRI-neuropathology validation. Stroke. 2021;52:A36. doi: 10.1161/str.52.suppl_1.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A., Boulouis G., Frosch M.P., Baron J.C., Pasi M., Albucher J.F., Banerjee G., Barbato C., Bonneville F., Brandner S., Calviere L., Caparros F., Casolla B., Cordonnier C., Delisle M.B., Deramecourt V., Dichgans M., Gokcal E., Herms J., Hernandez-Guillamon M., Jager H.R., Jaunmuktane Z., Linn J., Martinez-Ramirez S., Martinez-Saez E., Mawrin C., Montaner J., Moulin S., Olivot J.M., Piazza F., Puy L., Raposo N., Rodrigues M.A., Roeber S., Romero J.R., Samarasekera N., Schneider J.A., Schreiber S., Schreiber F., Schwall C., Smith C., Szalardy L., Varlet P., Viguier A., Wardlaw J.M., Warren A., Wollenweber F.A., Zedde M., van Buchem M.A., Gurol M.E., Viswanathan A., Al-Shahi Salman R., Smith E.E., Werring D.J., Greenberg S.M. The Boston criteria version 2.0 for cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a multicentre, retrospective, MRI-neuropathology diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:714–725. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00208-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell P.M., Barakos J.A., Barkhof F., Benzinger T.S., Jack C.R., Poussaint T.Y., Raji C.A., Ramanan V.K., Whitlow C.T. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with emerging Alzheimer disease therapeutics: detection and reporting recommendations for clinical practice. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2022;43(9):E19–E35. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enlarged perivascular spaces (EPVS): a visual rating scale and user guide. https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/imports/fileManager/epvs-rating-scale-user-guide.pdf. (accessed April 24, 2023).

- Fazekas F., Chawluk J.B., Alavi A., Hurtig H.I., Zimmerman R.A. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–356. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertje E.C., van Westen D., Panizo C., Mattsson-Carlgren N., Hansson O. Association of enlarged perivascular spaces and measures of small vessel and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2021;96:e193–e202. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouw A.A., Seewann A., van der Flier W.M., Barkhof F., Rozemuller A.M., Scheltens P., Geurts J.J. Heterogeneity of small vessel disease: a systematic review of MRI and histopathology correlations. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2011;82:126–135. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.204685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff-Radford, J., Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M., Knopman, D.S., Schwarz, C.G., Brown, R.D., Rabinstein, A.A., Gunter, J.L., Senjem, M.L., Przybelski, S.A., Lesnick, T., Ward, C., Mielke, M.M., Lowe, V.J., Petersen, R.C., Kremers, W.K., Kantarci, K., Jack, C.R., Vemuri, P., 2019. White matter hyperintensities: relationship to amyloid and tau burden. Brain 142, 2483-2491.10.1093/brain/awz162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greenberg S.M., Charidimou A. Diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: evolution of the boston criteria. Stroke. 2018;49:491–497. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg S.M., Vonsattel J.P. Diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Sensitivity and specificity of cortical biopsy. Stroke. 1997;28:1418–1422. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.7.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg S.M., Bacskai B.J., Hernandez-Guillamon M., Pruzin J., Sperling R., van Veluw S.J. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer disease - one peptide, two pathways. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020;16:30–42. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0281-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurol M.E., Viswanathan A., Gidicsin C., Hedden T., Martinez-Ramirez S., Dumas A., Vashkevich A., Ayres A.M., Auriel E., van Etten E., Becker A., Carmasin J., Schwab K., Rosand J., Johnson K.A., Greenberg S.M. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy burden associated with leukoaraiosis: a positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann. Neurol. 2013;73:529–536. doi: 10.1002/ana.23830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman B.T., Phelps C.H., Beach T.G., Bigio E.H., Cairns N.J., Carrillo M.C., Dickson D.W., Duyckaerts C., Frosch M.P., Masliah E., Mirra S.S., Nelson P.T., Schneider J.A., Thal D.R., Thies B., Trojanowski J.Q., Vinters H.V., Montine T.J. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakel L., De Kort A.M., Klijn C.J.M., Schreuder F., Verbeek M.M. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18:10–28. doi: 10.1002/alz.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapeller P., Barber R., Vermeulen R.J., Ader H., Scheltens P., Freidl W., Almkvist O., Moretti M., del Ser T., Vaghfeldt P., Enzinger C., Barkhof F., Inzitari D., Erkinjunti T., Schmidt R., Fazekas F., Force E.T., European Task Force of Age Related White Matter Visual rating of age-related white matter changes on magnetic resonance imaging: scale comparison, interrater agreement, and correlations with quantitative measurements. Stroke. 2003;34:441–445. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000049766.26453.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Cho H., Park M., Kim J.W., Ahn S.J., Lyoo C.H., Suh S.H., Ryu Y.H. MRI-visible perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale are associated with brain amyloid deposition in patients with alzheimer disease-related cognitive impairment. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021;42:1231–1238. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Zimmerman M.E., Narkhede A., Nasrabady S.E., Tosto G., Meier I.B., Benzinger T.L.S., Marcus D.S., Fagan A.M., Fox N.C., Cairns N.J., Holtzman D.M., Buckles V., Ghetti B., McDade E., Martins R.N., Saykin A.J., Masters C.L., Ringman J.M., Frster S., Schofield P.R., Sperling R.A., Johnson K.A., Chhatwal J.P., Salloway S., Correia S., Jack C.R., Jr., Weiner M., Bateman R.J., Morris J.C., Mayeux R., Brickman A.M., Alzheimer D.I. White matter hyperintensities and the mediating role of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in dominantly-inherited Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyall D.M., Cox S.R., Lyall L.M., Celis-Morales C., Cullen B., Mackay D.F., Ward J., Strawbridge R.J., McIntosh A.M., Sattar N., Smith D.J., Cavanagh J., Deary I.J., Pell J.P. Association between APOE e4 and white matter hyperintensity volume, but not total brain volume or white matter integrity. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14:1468–1476. doi: 10.1007/s11682-019-00069-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ramirez S., Pontes-Neto O.M., Dumas A.P., Auriel E., Halpin A., Quimby M., Gurol M.E., Greenberg S.M., Viswanathan A. Topography of dilated perivascular spaces in subjects from a memory clinic cohort. Neurology. 2013;80:1551–1556. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828f1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ramirez S., van Rooden S., Charidimou A., van Opstal A.M., Wermer M., Gurol M.E., Terwindt G., van der Grond J., Greenberg S.M., van Buchem M., Viswanathan A. Perivascular spaces volume in sporadic and hereditary (dutch-type) cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2018;49:1913–1919. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na H.K., Kim H.-K., Lee H.S., Park M., Lee J.H., Ryu Y.H., Cho H., Lyoo C.H. Role of enlarged perivascular space in the temporal lobe in cerebral amyloidosis. Ann. Neurol. 2023;93(5):965–978. doi: 10.1002/ana.26601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. https://naccdata.org/. (accessed March 6, 2021).

- NACC GD : National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. Researcher’s Data Dictionary — Genetic Data. https://files.alz.washington.edu/documentation/rdd-genetic-data.pdf. (accessed March 28, 2021).

- NACC NP: NP Data Form Version 10, January 2014. https://naccdata.org/data-collection/forms-documentation/np-10. (accessed March 28, 2021).

- NACC RDD: National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. Researcher's Data Dictionary Uniform Data Set Version 3.0, March 2015. https://files.alz.washington.edu/documentation/uds3-rdd.pdf. (accessed March 28, 2021).

- Olichney J.M., Hansen L.A., Hofstetter C.R., Lee J.H., Katzman R., Thal L.J. Association between severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cerebrovascular lesions in Alzheimer disease is not a spurious one attributable to apolipoprotein E4. Arch. Neurol. 2000;57:869–874. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasi M., Boulouis G., Fotiadis P., Auriel E., Charidimou A., Haley K., Ayres A., Schwab K.M., Goldstein J.N., Rosand J., Viswanathan A., Pantoni L., Greenberg S.M., Gurol M.E. Distribution of lacunes in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive small vessel disease. Neurology. 2017;88:2162–2168. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter G.M., Chappell F.M., Morris Z., Wardlaw J.M. Cerebral perivascular spaces visible on magnetic resonance imaging: development of a qualitative rating scale and its observer reliability. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2015;39:224–231. doi: 10.1159/000375153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins N.D., Scheltens P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: an update. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11:157–165. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijmer Y.D., van Veluw S.J., Greenberg S.M. Ischemic brain injury in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:40–54. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas S., Brugulat-Serrat A., Bargallo N., Minguillon C., Tucholka A., Falcon C., Carvalho A., Moran S., Esteller M., Gramunt N., Fauria K., Cami J., Molinuevo J.L., Gispert J.D. Higher prevalence of cerebral white matter hyperintensities in homozygous APOE-varepsilon4 allele carriers aged 45–75: Results from the ALFA study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:250–261. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17707397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R.A., Jack C.R., Jr., Black S.E., Frosch M.P., Greenberg S.M., Hyman B.T., Scheltens P., Carrillo M.C., Thies W., Bednar M.M., Black R.S., Brashear H.R., Grundman M., Siemers E.R., Feldman H.H., Schindler R.J. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer's Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:367–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudre C.H., Cardoso M.J., Frost C., Barnes J., Barkhof F., Fox N., Ourselin S., Neuroimaging A.D.I. APOE epsilon4 status is associated with white matter hyperintensities volume accumulation rate independent of AD diagnosis. Neurobiol. Aging. 2017;53:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H.H., Pasi M., Tsai L.K., Huang C.C., Chen Y.F., Lee B.C., Yen R.F., Gurol M.E., Jeng J.S. Centrum semiovale perivascular space and amyloid deposition in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2021;52:2356–2362. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veluw S.J., Biessels G.J., Bouvy W.H., Spliet W.G., Zwanenburg J.J., Luijten P.R., Macklin E.A., Rozemuller A.J., Gurol M.E., Greenberg S.M., Viswanathan A., Martinez-Ramirez S. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy severity is linked to dilation of juxtacortical perivascular spaces. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:576–580. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15620434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonsattel J.P., Myers R.H., Hedley-Whyte E.T., Ropper A.H., Bird E.D., Richardson E.P., Jr. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy without and with cerebral hemorrhages: a comparative histological study. Ann. Neurol. 1991;30:637–649. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.L., Zou Q.Q., Sun Z., Wei X.E., Li P.Y., Wu X., Li Y.H., Neuroimaging A.D.I. Associations of MRI-visible perivascular spaces with longitudinal cognitive decline across the Alzheimer's disease spectrum. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022;14:185. doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-01136-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlaw J.M., Smith E.E., Biessels G.J., Cordonnier C., Fazekas F., Frayne R., Lindley R.I., O'Brien J.T., Barkhof F., Benavente O.R., Black S.E., Brayne C., Breteler M., Chabriat H., Decarli C., de Leeuw F.E., Doubal F., Duering M., Fox N.C., Greenberg S., Hachinski V., Kilimann I., Mok V., Oostenbrugge R., Pantoni L., Speck O., Stephan B.C., Teipel S., Viswanathan A., Werring D., Chen C., Smith C., van Buchem M., Norrving B., Gorelick P.B., Dichgans M., nEuroimaging S.T.f.R.V.c.o. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:822–838. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.C., Chabriat H., Godin O., Dufouil C., Rosand J., Greenberg S.M., Smith E.E., Tzourio C., Viswanathan A. Distribution of white matter hyperintensity in cerebral hemorrhage and healthy aging. J. Neurol. 2012;259:530–536. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6218-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The study dataset was obtained from NACC and is publicly available (https://naccdata.org/). All of the data analyzed for this study are reported in this manuscript.

The dataset was obtained from NACC that is publicly available