Abstract

Advances in cancer immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors, have dramatically improved the prognosis for patients with metastatic melanoma and other previously incurable cancers. However, patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) generally do not respond to these therapies. PDAC is exceptionally difficult to treat because of its often late stage at diagnosis, modest mutation burden, and notoriously complex and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). Simultaneously interrogating features of cancer, immune, and other cellular components of the PDAC TME is therefore crucial for identifying biomarkers of immunotherapeutic resistance and response. Notably, single-cell and multiomics technologies, along with the analytical tools for interpreting corresponding data, are facilitating discoveries of the systems-level cellular and molecular interactions contributing to the overall resistance of PDAC to immunotherapy. Thus, in this review, we will explore how multiomics and single-cell analyses provide the unprecedented opportunity to identify biomarkers of resistance and response to successfully sensitize PDAC to immunotherapy.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is notoriously lethal with a rising incidence and stagnant 5-year survival rate of 11%1,2. Reliable screening for PDAC is limited, and most patients are diagnosed with advanced disease3. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are showing promising results in a variety of cancers4, PDAC remains nonresponsive except for 1–2% of patients with mismatch-repair deficiency (MMRd) that respond to anti-PD1 monotherapy5. Even this measurable overall response rate, however, is notably less than for other MMRd tumor types6. Dual agent ICIs, including combinations targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA4, are also ineffective in PDAC7. Compared to ICI-responsive cancers, PDAC has a modest mutational burden (50–70 neoantigens per tumor)8 and a highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment consisting of abundant Tregs, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)9. These features distinguish PDAC as non-immunogenic and illustrate how anti-tumor T cells are largely unavailable for elicitation by ICIs in this disease.

Researchers have therefore posited that effective immunotherapy in PDAC will be combinatorial, not only releasing T cells from exhaustion but also inducing them to target cancer cells within a complex immunosuppressive TME9,10. Although many immunotherapies to induce T cells and modify the TME are currently available, the precise combination to effectively treat and cure PDAC remains elusive. Selecting the optimal combination therapeutic strategy requires knowledge of precise composition of the immunosuppressive mechanisms in each patient’s tumor. To enable this, innovative methods for collecting, analyzing, and integrating single-cell and multiomics data are enabling holistic and quantitative evaluations of immunotherapy-induced molecular changes to the PDAC TME. The mechanistic insights obtained from these technologies have extraordinary potential to transform PDAC into an immunotherapy-responsive disease. In this review we will therefore discuss how multiomics technologies and computational approaches for the analysis of T cells and other TME components can support the development of rationally designed combination treatment strategies to convert PDAC into a disease treatable with immunotherapy.

T cells as immunotherapeutic targets in PDAC

Although infiltrating T cells are found in most pancreatic tumors, their densities vary widely between patients and are generally sparse11–13. This paucity of T cells corresponds to limited anti-tumor T cell responses, and PDAC is therefore described as “immunologically cold”. However, immunogenic mutations and cytotoxic anti-tumor T cell responses are found in long-term PDAC survivors14. This suggests that T cell immunity is not only relevant but essential for tumor cell clearance and is hindered by both a highly immunosuppressive TME and a relatively modest mutation burden8 that limits the number of tumor antigens available for recognition by effector T cells. Furthermore, T cell killing after anti-PD1 monotherapy is effective in a rare subset of mismatch repair deficient PDAC tumors5. Thus these data reflect the importance of T cells for anti-tumor immunity in PDAC and rationalize investigations into therapies to induce and enhance these responses.

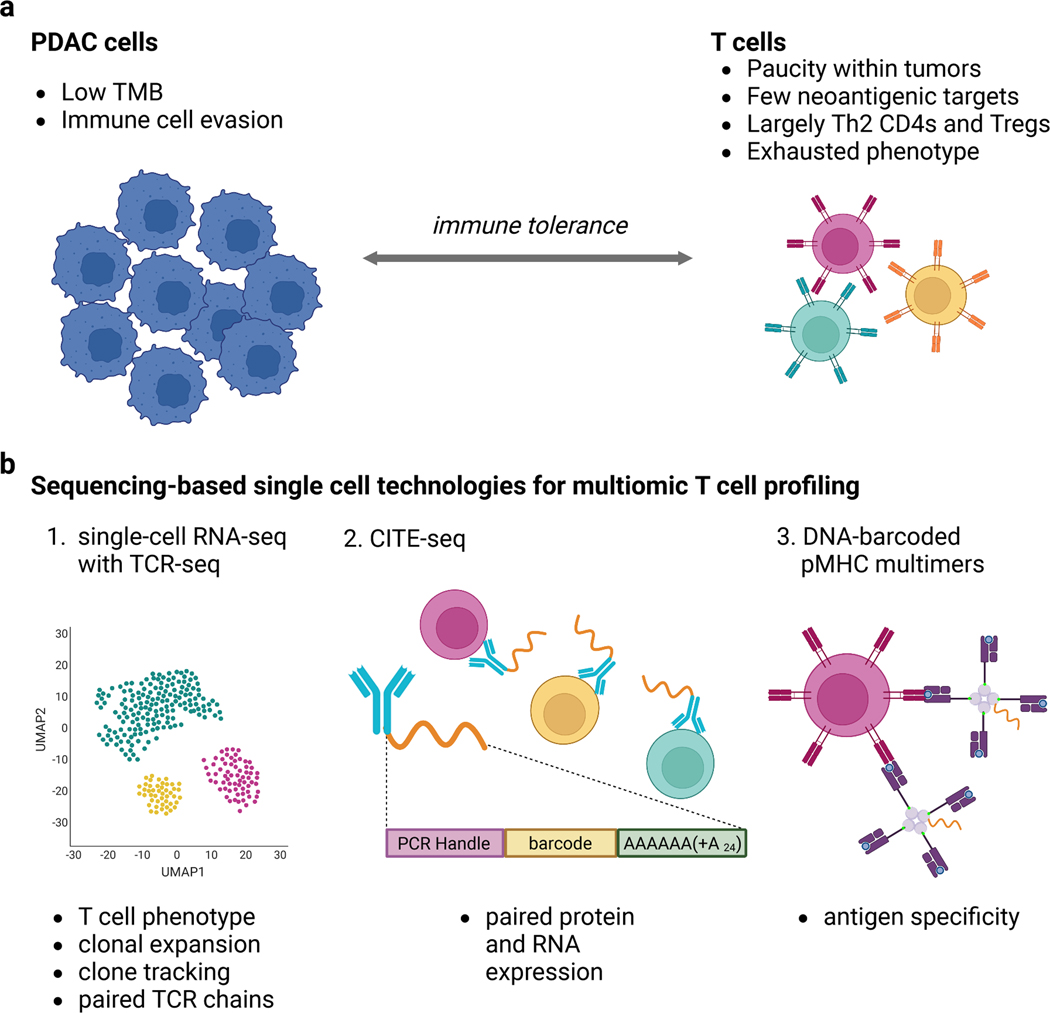

It next becomes crucial to understand the baseline landscape of tumor-infiltrating T cells in PDAC. These T cells are largely CD4+ and skew toward the Th2 lineage15,16, which is known to promote immune tolerance of the tumor17. Tregs are also commonly detected within tumors and further contribute to overall immune evasion16,18. Notably, Treg abundance increases as PDAC progresses, both intratumorally and in the periphery, and directly correlates with worse outcomes19,20. This heterogeneity and abundance of CD4+ tumor infiltrating T cells is contrasted by the relative scarcity of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Figure 1a). Other relevant features of T cell immunity in PDAC have been reviewed in depth elsewhere21. Overall, the conversion of this largely tumor-promoting T cell population toward tumor killing is a primary goal of PDAC immunotherapy.

Figure 1: Multiomic profiling of T cells in PDAC can identify mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance.

a. T cells in PDAC are generally sparse, exhausted, and have few neo-antigenic targets for effective tumor cell killing. b. Single-cell technologies can simultaneously reveal T cell phenotypes, clonal dynamics over time and across tissues, and antigen specificity.

Systems biology approaches and multiomics technologies enable the discovery of targets that can enhance the quality and function of T cells in pancreatic cancer (Table 1). For example, concurrent single-cell transcriptional (scRNA-seq) and T cell receptor (TCR) sequencing provides the opportunity to relate T cell phenotypes to functional response and identify clones that traffic between the tumor and periphery during treatment response. In these technologies, the transcriptional profiles from scRNA-seq data enable clustering for cell type identification. The matched TCR sequences for each cell can be further correlated with the neoantigenic landscape of PDAC via genomic sequencing of tumors. This approach was recently used to demonstrate that expansion of T cell clones corresponds to more highly immunoedited tumors from patients with PDAC22. Relating the number and quality of neoantigens in an individual tumor to T cell clonality may also enable prediction of immunogenic epitopes targeted by anti-tumor T cells. B cells, although their role in human PDAC remains controversial, can also be assessed via scRNA-seq with matched B cell receptor (BCR)-seq. Notably, the pairing of chains enabled by scRNA-seq is exceptionally important for cloning full TCRs and BCRs of interest for functional assays as well as for clinical applications23. Specialized software has been developed to streamline analysis of these repertoire datasets, including scirpy24 as an extension of the python-based single-cell analysis tool scanpy25 and scRepertoire26 as an R package that integrates with the popular Seurat27–29 suite. Immunarch30, another R-based repertoire analysis package, is also compatible with single cell data.

Table 1:

Multiomics approaches for T cell and TME profiling in PDAC

| Technology | Data output | Computational analytical tools |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq with matched TCR-seq (10X Genomics, SMART-seq76,127) | • Phenotype via transcriptome • Paired α/β TCR sequence |

RNA*

• Seurat27–29 • monocle128–130 • Cumulus131 • scanpy25 TCR • scRepertoire26 • immunarch30 • scirpy24 • Immcantation portal132,133 |

| CITE-seq31,32 | • Phenotype via transcriptome and DNA-barcoded surface antibodies • Compatible with multiplexing (i.e. TCR-seq, other 10X Genomics feature barcodes) |

• Seurat27–29 • CITE-seq-Count134 • Cumulus131 |

| DNA-barcoded pMHC multimers (10X Genomics feature-barcode technology, tetTCR-seq35,135) | • Phenotype via transcriptome and DNA-barcoded surface antibodies • Compatible with multiplexing (i.e. TCR-seq, other 10X Genomics feature barcodes) |

• Seurat27–29 • Cumulus131 |

| Spatial transcriptomics (Slide-seq83, 10X Genomics Visium and Xenium In Situ, Nanostring DSP85 and CosMx, MERFISH136) | • Spatially resolved phenotype via RNA expression • α/β TCR sequences54,137 |

• Seurat27–29 • Cumulus131 • Giotto138 • squidpy139 • spatialExperiment140 • spatialLIBD141 • spatialDE142 |

DSP: Digital Spatial Profiling, sDAS: spatial Data Analysis Service

For up-to-date single-cell analytical tools: https://www.scrna-tools.org143 Please note that this table is not exhaustive, but rather emphasizes a subset of the many technologies and software available.

A challenge with cellular phenotyping from scRNA-seq technologies is that the functional similarity between T cell subtypes and low detection of transcripts in a phenomenon called drop out can limit separation of common T cell subtypes, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. To address this limitation, a technique called CITE-seq31,32 that integrates surface protein expression with scRNA-seq in the same cells has recently been commercialized. This approach uses DNA-barcoded antibodies to target proteins of interest, where each protein’s antibody is associated with a unique barcode for sequencing-based identification and quantification. These antibodies can also be used for cell hashing33 in which each sample is stained with a uniquely barcoded antibody targeting ubiquitously expressed cell surface proteins, commonly β2M and CD298 for human cells. In this way, each sample is associated with a unique barcode, enabling multiplexing of several samples into a single sequencing run. Subsequent computational deconvolution of reads based on barcode sequence allows for mapping sequencing data back to original samples. To date, these methods are largely limited to extracellular proteins, but advances enabling detection of intracellular proteins are rapidly developing34.

Other recent single-cell advances include DNA-barcoded major histocompatibility complex (MHC) multimers, including tetTCR-seq35,36 and 10X Genomics’ feature barcode technology. This approach reveals T cell antigen specificity to known peptide-MHC complexes. A similar approach can be used to determine B cell specificity using barcoded antigens of interest, without the need for MHC. Although tremendously useful for known antigens, unbiased and high throughput methods for discovering T cell antigen specificity linked to receptor sequence remain an active area of research37. Importantly, these DNA barcoded molecules are compatible with scRNA-seq workflows, thereby enabling simultaneous detection of transcriptome, TCR and BCR sequence, cell surface protein expression, and antigen specificity of individual cells. Crucially, application of some or all these technologies can reveal fundamental aspects of T cells during response versus resistance to immunotherapy in PDAC (Figure 1b).

While single-cell technologies characterize the functional state and antigen specificity of T cells, of equal importance to phenotype is the localization of T cells within pancreatic tumors. It has been shown that improved overall survival in PDAC correlates with proximity of CD8+ T cells to cancer cells13. Strikingly, this association was not observed when applied to either total T cells or CD4+ T cells, indicating that physical interactions between tumor cells and CD8+ T cells is required for anti-tumor immunity in PDAC. Furthermore CD8+ T cells are generally excluded from regions containing cancerous cells in PDAC50, suggesting that these tumors employ various mechanisms to prevent cytotoxic CD8+ T cell trafficking and killing. Other studies demonstrate that enrichment of CD8+ T cells near cancerous pancreatic cells correlates with improved survival in patients13. Nonetheless, a recent study has shown that T cell killing can induce malignant epithelial cells to express markers of myeloid cells to prevent subsequent T cell attack in mouse models of PDAC51. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that factors beyond cancer and T cell interactions account for the general lack of T cell immunity in PDAC. Spatial molecular technologies with single-cell resolution, such as spatial transcriptomics52 and proteomics53, are providing new opportunities to characterize these cellular relationships. Moreover, emerging extensions of these techniques enable high dimensional molecular characterization to allow for further evaluation of the phenotypic and functional changes in these cells resulting from their co-localization54–57.

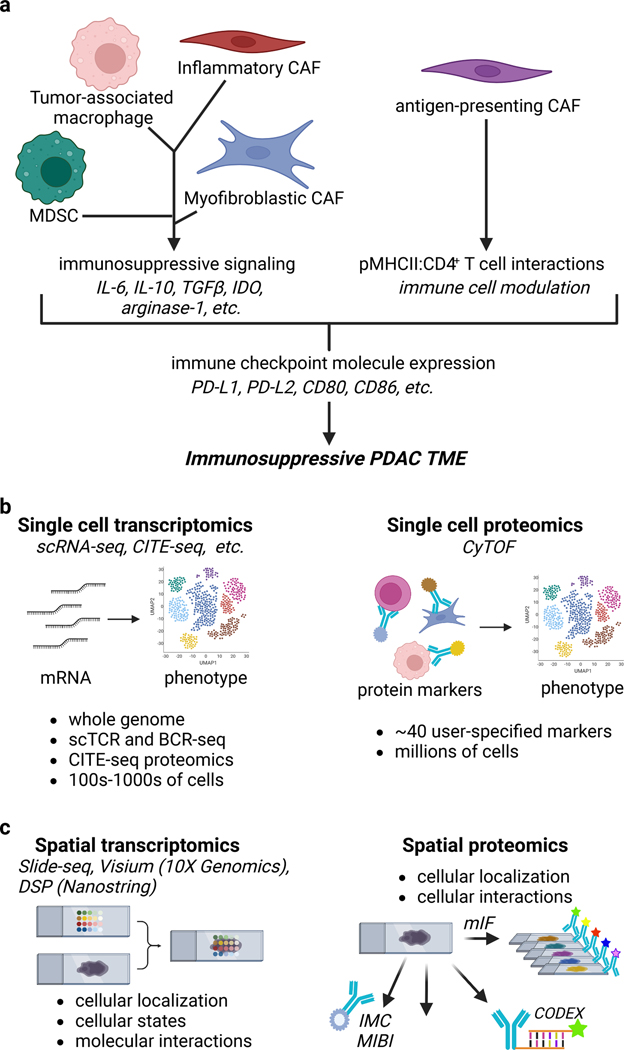

PDAC has an immunosuppressive TME

T cells are but one of the many cell types within the pancreatic cancer TME. Notably, their B cell counterparts are largely tumor-promoting in murine models of PDAC58–60. However, their precise role in human disease remains ill-defined, as was recently reviewed elsewhere61. Additionally, the stroma of PDAC is dense and contributes tremendously to its immunosuppressive characteristics62.63 Stromal cells secrete many immunosuppressive signaling molecules, including various interleukins (IL6, IL10), transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), among others9,10. Expression of immune checkpoint molecules by stromal cells further promotes T cell evasion via inactivation and exhaustion. Cancer cells employ these same mechanisms to avoid CD8+ T cell killing. However, just as T cells exhibit vast functional diversity, so do other stromal cells, including cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), and myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)9. For example, single-cell studies have demonstrated the existence of heterogeneous populations of CAFs64,65, including myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs), inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), and a population of MHC class II expressing CAFs also called antigen presenting CAFs (apCAFs)66,67. The precise role of these various CAF phenotypes and other cellular components of the PDAC TME remain unknown and are an active area of research. Indeed, application of multiomics and systems immunology approaches will be essential for integrating these complex cellular relationships within the TME to identify therapeutic targets for sensitizing PDAC to immunotherapy (Figure 2a).

Figure 2: Profiling cellular components of the PDAC TME through multiomics.

a. Specific cells within the PDAC TME, including myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophages, and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFS) contribute to immunosuppression via signaling molecules and immune checkpoint expression. b. Single cell technologies can reveal novel cellular phenotypes and interactions responsible for immunotherapeutic response and resistance in PDAC. c. Spatial technologies are rapidly advancing and have the potential to enhance our understanding of molecular interactions responsible for therapeutic outcomes in patients with PDAC. More examples of relevant technologies can be found in Table 1.

PDAC is known to progress from precancerous pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanINs) that accumulate mutations over time68. Genomics studies of PDAC show that it is not a somatic genetic disease with many mutations across the genome, but rather represents a cancer largely driven by mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes including KRAS, TP53, SMAD4, and CDKN2A69. This not only contributes to its immunologically “cold” phenotype by limiting the number of immune accessible neoantigens, but also to immunosuppression within the TME by promoting inflammation and tumorigenesis. Mutant KRAS, for example, occurs in more than 90% of PDACs and was long thought to promote carcinogenesis by inducing sustained proliferation via downstream signaling pathways69. While this is undoubtedly important, KRAS signaling also generates pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that directly mold the TME70,71. These molecules, many downstream of NF-κB, directly contribute to a pro-tumorigenic and immunosuppressive TME72,73, and are thus critical to consider when examining immunotherapy response in PDAC.

Multiomics technologies enable systems-wide evaluation of the PDAC TME

Interactions between cells within the PDAC TME have been shown to mediate immunotherapeutic response and resistance74. Therefore, to elicit anti-tumor T cell responses, we need an integrated understanding of not only immune and cancer cells but also a systems level characterization of the impact of cells in the TME on immunosuppression. Many single cell technologies, including suspension and spatial molecular technologies, can fully resolve the cellular phenotypes in the TME and are invaluable for revealing mechanisms of immune evasion. Although the opportunity to multiplex sequencing-based experiments is vast, the number of cells that can be assessed at one time is limited. For example, droplet-based approaches like 10X Genomics scRNA-seq75 workflow yield approximately 5,000–10,000 cells per sample, while plate-based protocols like SmartSeq76 generally sequence hundreds of cells per experiment. Sampling is thus a crucial consideration when analyzing scRNA-seq data, as rare cell populations may be poorly represented or even entirely missing.

In cases where protein marker expression across many cells or examination of rare cell populations within the TME is desirable, mass cytometry (CyTOF)77 may be preferred to the previously described sequencing assays. CyTOF makes use of antibodies conjugated to heavy metal ion tags rather than fluorophores used in traditional flow cytometry. This enables detection of many more proteins than flow-based assays while maintaining the capacity to phenotype millions of cells. There is therefore a tradeoff in these technologies between molecular and cellular resolution. Whereas scRNA-seq technologies provide measurements of thousands of molecules simultaneously, CyTOF provides more limited profiling of tens of proteins. However, the prior selection of antibody panels is critical to delineate TME cell composition with CyTOF whereas scRNA-seq technologies enable unbiased profiling of immune cell state and function. Still, CyTOF samples more cells than scRNA-seq, enabling enhanced characterization of rare cell subtypes without the need for cellular sorting in complementary scRNA-seq profiling studies (Figure 2b). These suspension-based profiling techniques are being supplemented by rapid advances to spatial molecular profiling, spanning from digital pathology techniques for proteomics78–81 to spatially resolved transcriptomics characterization82,83 (Figure 2c). These techniques are further expanding to include spatially resolved multiomics54,56,84,85 and CRISPR-based genetic screens57. Altogether, these new spatial molecular technologies provide greater ability to monitor and quantify cellular co-localization and interactions between diverse cell types in the TME that moderate immune response. As these spatial technologies develop, they are extending from two-dimensional characterization of slides to three dimensional analyses of tumore and TME architecture with techniques including CODA63.

Metastases are common upon PDAC diagnosis

In evaluating mechanisms of therapeutic resistance in PDAC, it is important to emphasize the high prevalence of metastatic disease upon diagnosis. Differences in the cellular composition between metastatic sites have tremendous implications for treating disease. For example, a recent study in PDAC mouse models used CyTOF, immunohistochemistry, and RNA-seq to demonstrate that the lung metastatic environment has marked immune activation and infiltration while the liver is more immunosuppressive86. Another study harnessing scRNA-seq to examine metastases in patients with PDAC suggests that both the TME and cancer cell states vary widely between sites87. The authors report on two varied mesenchymal cellular states that they deem fibroblast-like or pericyte-like based on associated gene expression. Notably, liver metastases were highly associated with the pericyte-like state and primary tumors with the more fibroblast-like mesenchymal state. Furthermore, using bulk RNA-seq defined PDAC cellular subtypes, the authors denote three major cancer cell states from their scRNA-seq data: scBasal, scClassical, and their newly discovered IC state that represents a combination of the two. Using these definitions, it was found that scClassical and IC tumors had greater diversity in their TME than the more homogeneous scBasal types, with most of this diversity contributed by non-malignant cells. Together, the cellular and molecular heterogeneity indicated by these studies highlight that immunotherapeutic regimens in PDAC will need to target site-specific mechanisms of resistance.

Another recent study using spatial multiomics identifies sub-tumor microenvironments (subTMEs) in both primary PDAC and its metastases88. subTMEs are defined as spatially distinct TME phenotypes that co-occur within the same sample and exhibit distinct gene and protein expression profiles. Notably, abundant subTMEs represent a more diverse TME that is associated with poor survival for patients with PDAC. It is critical to characterize this heterogeneity as it further complicates the selection of combination therapies for treatment of patients with abundant subTMEs. Altogether, these and other emerging studies reveal how multiomic approaches and their corresponding analysis tools enable a molecular understanding of immunotherapeutic resistance across cell types and sites necessary for discovering effective combination immunotherapy strategies for PDAC.

Cellular atlases are invaluable for identifying therapeutic targets in PDAC

Cellular reference atlases constructed using single-cell and spatial molecular technologies can provide a baseline of the immunological state of cancer and importantly serve as a reference against which to evaluate therapeutic perturbations. Several atlases for PDAC are available89–94, including two with novel findings regarding myeloid cells in PDAC. The first was constructed by combining proteomics data from CyTOF and multiplexed immunofluorescence with transcriptomics from scRNA-seq90. Notably, the authors found an inverse correlation between the percentage of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and myeloid cells by proteomics, supporting the notion that these myeloid cells are key drivers of immunosuppression in PDAC15,95. Additionally, tumor-infiltrating exhausted and memory CD8+ T cells and NK cells showed enhanced expression of the immune checkpoint molecule TIGIT by both scRNA-seq and proteomics. Notably, the authors were able to predict interactions96,97 between T cells, NK cells, and myeloid cells, including expression of the TIGIT ligand PVR in macrophages. Another PDAC atlas was constructed using chromogen-based multiplexed immunohistochemistry imaging of lymphoid and myeloid lineage cells from 135 different PDAC specimens92. Analysis of this atlas revealed tremendous immune heterogeneity within individual PDAC samples and found that the CD8+ T cell to CD68+ monocyte/macrophage ratio was higher in tumor regions from long-term survivors, again suggesting the presence of an immunosuppressive myeloid population in PDAC. Taken together, these myeloid-related findings indicate that these cells may be attractive targets for combination immunotherapy in PDAC. They also more generally demonstrate the hypothesis-generating capacity of PDAC atlases as well as their discovery potential via analysis using novel computational tools.

While in silico characterization in human tissue leads to robust characterization of the PDAC TME, translating the novel targets they discover requires further mechanistic validation in preclinical models. Therefore, a recent large-scale scRNA-seq atlas was collated from six different studies representing 61 treatment-naïve PDAC and 16 non-malignant pancreas samples94 with the goal of improving in vitro studies of CAF-cancer interactions. This study demonstrates that a machine learning approach called transfer learning98 can relate gene expression changes in tumor cells resulting from CAF interactions in human tumors to co-cultures of patient-derived organoids and CAFs. In the case of CAFs, cross-species analyses have also demonstrated the ability to use scRNA-seq datasets to reveal preserved CAF function between mouse models of PDAC and human tumors67,86. These findings, based on converging computational and experimental approaches, demonstrate the value of cellular atlases in elucidating the underlying biology of PDAC that can be further extended to mechanistic validation in preclinical models. Comparison of data from preclinical and clinical trial samples treated with combination immunotherapy to these and future atlases offers an exciting opportunity to define treatment-induced biological changes versus normal heterogeneity within pancreatic tumors.

Computational methods are essential for interpretation of high-dimensional multiomics data

Inferring biological signal from the high-dimensional data obtained from single cell technologies requires complementary computational techniques for analysis (Table 1). The realm of analytical pipelines for analysis are changing as rapidly as the available technologies themselves. This requires evaluation of state-of-the-art data analysis and preprocessing techniques for accurate interpretation of the molecular state of the TME. Careful experimental design to minimize batch effects, account for sample size limitations, and balance costs is just as important as defining an analytical and statistical analysis plan for the data produced. This active area of research has been reviewed elsewhere99. Often, selecting both the appropriate experimental technique and analysis tools for interpretation is best achieved through careful consultation between translational and computational researchers working as part of a multidisciplinary team. Overall, converging biological, technological, and computational expertise through team science will facilitate and hasten the accurate discovery of new therapeutic targets for PDAC.

Combination immunotherapy in PDAC

Understanding current immunotherapeutic successes and shortcomings is essential for improving outcomes for patients with PDAC. As previously discussed, ICIs in PDAC are largely ineffective. It is hypothesized that anti-tumor T cells must first be elicited for successful ICI therapy9,21,100. Induction or enrichment of anti-tumor T cells may be achieved by a variety of methods, including vaccination101 and T cell engineering for adoptive cell therapy (ACT)102. Notably, none of these strategies alone has proven effective for the treatment of PDAC, although recently a single patient with PDAC demonstrated regression of metastases at six months after receiving autologous T cells engineered to target mutant KRAS G12D23. This lack of efficacy in PDAC therapy is largely because of other underexplored mechanisms of immunosuppression in the TME. Our current knowledge of contributing molecular pathways and corresponding therapeutic targets in PDAC has been reviewed in depth elsewhere9. However, it is important to establish the role of multiomics technologies and analytical tools in discerning important mechanisms of resistance to immunotherapy in PDAC from both preclinical and clinical studies. We are now uniquely poised to make advances in both precision medicine and effective combination therapies to improve outcomes for patients with PDAC.

Overcoming limitations of preclinical models of combination immunotherapy in PDAC

Preclinical models of combination immunotherapy in PDAC are the gold standard for informing clinical trial design. As an example, MDSCs are known to contribute to the immunosuppressive TME of PDAC, and strategies to reprogram these cells may make tumors vulnerable to ICIs103,104. To this end, Christmas et al. found that the addition of the histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat (ENT) to anti-PD1, anti-CTLA4, or both, significantly improved tumor-free survival in a Panc02 mouse model of metastatic pancreatic cancer105. More specifically, this study found that addition of ENT enhanced the migration of MDSCs into tumors and converted them to a non-functional phenotype largely by blocking expression of the immunosuppressive molecule arginase-1. Notably, a phase 2 clinical trial examining the combination of ENT and nivolumab in unresectable or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma or PDAC (NCT03250273) demonstrated progression free survival at 6 months for a modest 3/30 PDAC patients enrolled in the study.

A second set of preclinical studies examined the combination of chemotherapy and CD40 agonism as a type of in vivo vaccination strategy to elicit anti-tumor T cell responses106,107. In brief, the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy induce tumor cell death, thereby releasing tumor antigens for immune recognition. As CD40 is expressed on antigen presenting cells (APCs), its agonism has been shown to improve vaccination response108 and may also enhance tumor antigen presentation after chemotherapy109. Indeed, in a spontaneous KPC mouse model of PDAC, the combination of the chemotherapeutic agents - gemcitabine and nab-paxlitaxel with anti-CD40 and anti-PD1 improved overall survival as compared to controls106. It was further shown that this anti-tumor effect was T cell mediated and required cross-presentation of tumor antigens by DCs107. This has led to a clinical trial examining sotigalimab (CD40 agonistic antibody) and chemotherapy with or without nivolumab in PDAC (NCT03214250). Although this trial initially showed overall tolerability and indicated some clinical activity110, the primary endpoint of one-year overall survival was not met for the triple therapy111.

Notable across these examples is how consistently discoveries in mice fail to translate to human disease112,113. Advances in cross-species analysis, however, are shifting this paradigm. As an example, transfer learning enables comparison of disparate datasets, including those of varied types and even across species. One study using the transfer learning tool projectR114 demonstrated a conserved NK cell signature between mouse and humans in anti-CTLA-4 responsive tumors115. More recently, this same analysis method enabled the further relation of PDAC-CAF cell interactions between human tumors and co-culture systems in PDAC as described above94. Another group examined the transcriptional fidelity of cancer models using SingleCellNet116 and found that genetically engineered mouse models are generally more like natural tumors than patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), cell lines, and tumoroids, although in some cases both PDXs and tumoroids recapitulated natural tumors well117.

Yet another study demonstrated the feasibility of statistically humanizing mutant KRAS signaling pathways quantified from mice to determine novel downstream modulation of effector molecules in humans by this potent oncogene118. Whereas these analysis methods all focus on directly relating human tumors to preclinical models for translational research, newer computational approaches to characterize where these phenotypes fail to transfer119 are essential to understand the differences in therapeutic response observed in patients. Crucially, rigorous multiomics, analytic, and transfer learning approaches can better inform investigators about pathways with potential for therapeutic targeting in humans from preclinical models. This will dramatically improve and expedite the initiation of evidence-based clinical trials with rational combination therapies for PDAC.

Multiomic analyses of neoadjuvant clinical trial specimens are essential for elucidating mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance in PDAC

Although preclinical studies are important tools for informing clinical trial design, improved patient outcomes are the ultimate objective. Carefully designed neoadjuvant studies are therefore necessary to facilitate human tissue profiling for assessment of treatment responses over time, across sites, and between treatment modalities directly from patients. For example, although the previously discussed trial of sotigalimab and chemotherapy with or without nivolumab in PDAC (NCT03214250) did not reach its primary endpoint with the triple therapy, the investigators collected serial biospecimens from each patient for further multiomics studies111. This enables interrogation of the mechanisms of response and resistance to therapy. Indeed, the authors performed CyTOF, high parameter flow cytometry, and serum proteomics from peripheral blood samples to define biomarkers of response. Notably, in the triple therapy arm, shorter survival correlated with an increased population of activated CD38+CD4+ and CD38+CD8+ T cells, suggesting that this therapy may induce terminal T cell exhaustion and thus account for its lack of efficacy. Importantly, this multiomics approach revealed a potential mechanism of resistance to therapy, which can be used to inform future preclinical and clinical studies. Another recent study profiled frozen PDAC specimens from 43 patients with or without neodjuvant therapy using single-nuclei(sn)-RNA-seq120. The authors found 14 distinct malignant cell transcriptional programs, including a newly identified neural-like progenitor (NRP) program. Crucially, the NRP program was associated with shorter time to disease progression as assessed from bulk RNA-seq of untreated primary PDAC extracted from reference bulk RNA-seq datasets from TCGA121 and PanCuRx/ICGC122,123. Further integration of this signature with whole transcriptome digital spatial profiling revealed that the NRP expression profile was enriched in malignant regions from patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy (CRT) as compared to untreated controls. Additional analysis of spatially linked receptor-ligand interactions enriched in CRT as compared to untreated samples revealed several signaling pathways that may contribute to resistance to therapy, including CXCL12-CXCR4 between epithelial and immune cells. This finding fits with previous studies investigating CXCR4 inhibition, which prevents interaction with its ligand CXCL12 on the tumor cell surface thereby enabling secretion of other migratory cytokines to promote immune cell trafficking to tumors124. An additional analysis using bulk RNA-seq of sorted tumor infiltrating lymphocytes from a neoadjuvant PDAC immunotherapy clinical trial demonstrated that anti-PD1 therapy alters intratumoral chemokine and cytokine signaling, leading to CD4+ T cell activation, myeloid cell trafficking, neutrophil degranulation, and alterations within the extracellular matrix that were hypothesized to reduce trafficking and activation of CD8+ cells74. Pre-treatment CD8+ T cell abundance, however, is associated with overall survival in this study, suggesting the need to target alternative and complementary pathways that enhance effector T cell function in PDAC. In each of these cases, a multiomics approach to analyzing human tissue from neoadjuvant trials revealed potential molecular mechanisms of resistance to therapy, underscoring the significance of this approach in successfully treating PDAC.

These translational studies demonstrate the importance of combination immunotherapy for improving outcomes in patients with PDAC and the utility of multiomics and single-cell methods described in this review. Given the complexity of cellular interactions and immunosuppressive mechanisms within the PDAC TME, a systems-wide evaluation across cell types is necessary for determining mechanisms of response and resistance to therapy. Each data type, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and their spatially resolved counterparts, have the capacity to reveal distinct biological features induced by immunotherapy in PDAC. Indeed, we finally have the technology available to begin integrating these findings across data types and model systems. Rather than examining a handful of pathways, we propose that PDAC researchers multiplex therapeutic strategies and analyses to enable faster and more efficacious precision immunotherapy combinations for future PDAC clinical trials. We anticipate that this approach will allow PDAC to transition from its designation as “immunologically cold” to immunologically malleable and treatable, using multiomics-guided precision immunotherapies tailored to individual patients.

Conclusions

High throughput multiomics profiling and computational advances are shifting the way we examine therapeutic outcomes for patients with PDAC. These approaches have tremendous potential to provide a systems-wide view of the dynamic and complex interactions occurring within the immunosuppressive PDAC TME. Emerging computational methods, including transfer learning to relate pathways inferred in one dataset to another, provide the opportunity for in silico validation. It is important to note that in silico validation requires test data that is new and independent of the training data to ensure robustness of the features learned. In contrast, applying multiple statistical models to the same data set does not serve as in silico validation. This would be the equivalent of analyzing the same sample by flow cytometry twice; this is not a biological replicate, but rather a technical replicate. When applied properly to new data, in silico validation enables direct hypothesis testing in patients throughout tumor progression125 and with therapeutic interventions126. Furthermore, transfer learning enables cross-species analysis and empowers rigorous preclinical mechanistic studies115,118. Most notably this type of analysis can delineate species-specific biological differences in immunotherapy response and resistance that are likely to fail in translation to clinic. Extension of these approaches to samples from clinical trials is ongoing and will be essential for dissecting the complex immunosuppressive factors contributing to therapeutic resistance directly from patients with PDAC.

While neoadjuvant studies enable direct characterization of pathways associated with therapeutic response in human tissue, they are limited to PDAC patients who can undergo surgical resection of their tumors and represent a single timepoint. Therefore, it is also critical to examine non-invasive samples, like those from peripheral blood, as well as primary and metastatic tumors to identify relevant biomarkers and enable tracking of therapeutic response over time in patients. As technologies and analytic tools progress and our arsenal of biomarkers of response versus resistance improves, we will have the potential to track response to therapy in real time for individual patients. The heterogeneity of these responses and their mechanistic underpinnings will enable a precision medicine approach by which we can shift therapies as the tumor and immune response evolves. Overall, this review highlights that the appropriate execution of multiomics techniques and their associated computational tools will profoundly empower effective and predictive immunotherapy in PDAC.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eric Christenson and Dimitri Sidiropoulos for their valuable feedback on this manuscript. Figures were created with BioRender.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Lustgarten Foundation (EMJ), Johns Hopkins University Discovery Award (EJF), and NIH/NCI (U01CA253403 to EJF; P01CA247886 to EMJ).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

E.M.J is a paid consultant for Adaptive Biotech, Achilles, DragonFly, Candel Therapeutics, Genocea, and Roche. She receives funding from Lustgarten Foundation and Bristol Myer Squibb. She is the Chief Medical Advisor for Lustgarten and SAB advisor to the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy (PICI) and for the C3 Cancer Institute. She is a founding member of Abmeta. E.J.F is on the SAB for Resistance Biology, Consultant for Mestag Therapeutics and Merck.

References

- 1.Park W, Chawla A. amp; O’Reilly EM Pancreatic Cancer: A Review. JAMA 326, 851–862 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE & Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA. Cancer J. Clin 72, 7–33 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD & Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 69, 7–34 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldman AD, Fritz JM & Lenardo MJ A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 651–668 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS, Wong F, Azad NS, Rucki AA, Laheru D, Donehower R, Zaheer A, Fisher GA, Crocenzi TS, Lee JJ, Greten TF, Duffy AG, Ciombor KK, Eyring AD, Lam BH, Joe A, Kang SP, Holdhoff M, Danilova L, Cope L, Meyer C, Zhou S, Goldberg RM, Armstrong DK, Bever KM, Fader AN, Taube J, Housseau F, Spetzler D, Xiao N, Pardoll DM, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Eshleman JR, Vogelstein B, Anders RA & Diaz LA Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357, 409–413 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maio M, Ascierto PA, Manzyuk L, Motola-Kuba D, Penel N, Cassier PA, Bariani GM, De Jesus Acosta A, Doi T, Longo F, Miller WH, Oh D-Y, Gottfried M, Xu L, Jin F, Norwood K. & Marabelle A. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient cancers: updated analysis from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 33, 929–938 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabacaoglu D, Ciecielski KJ, Ruess DA & Algül H. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Current Limitations and Future Options. Front. Immunol. 9, 1878 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A. & Jaffee EM Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2500–2501 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho WJ, Jaffee EM & Zheng L. The tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer — clinical challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 527–540 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balachandran VP, Beatty GL & Dougan SK Broadening the Impact of Immunotherapy to Pancreatic Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities. Gastroenterology 156, 2056–2072 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmrich J, Weber I, Nausch M, Sparmann G, Koch K, Seyfarth M, Löhr M. & Liebe S. Immunohistochemical characterization of the pancreatic cellular infiltrate in normal pancreas, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Digestion 59, 192–198 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R, Shimada K, Iwasaki M, Kosuge T, Kanai Y. & Hiraoka N. Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 108, 914–923 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carstens JL, Correa de Sampaio P, Yang D, Barua S, Wang H, Rao A, Allison JP, LeBleu VS & Kalluri R. Spatial computation of intratumoral T cells correlates with survival of patients with pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 8, 15095 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balachandran VP, Łuksza M, Zhao JN, Makarov V, Moral JA, Remark R, Herbst B, Askan G, Bhanot U, Senbabaoglu Y, Wells DK, Cary CIO, Grbovic-Huezo O, Attiyeh M, Medina B, Zhang J, Loo J, Saglimbeni J, Abu-Akeel M, Zappasodi R, Riaz N, Smoragiewicz M, Kelley ZL, Basturk O, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Prince of Wales Hospital, Royal North Shore Hospital, University of Glasgow, St Vincent’s Hospital, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, University of Melbourne, Centre for Cancer Research, University of Queensland, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, Bankstown Hospital, Liverpool Hospital, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, Westmead Hospital, Fremantle Hospital, St John of God Healthcare, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Flinders Medical Centre, Envoi Pathology, Princess Alexandria Hospital, Austin Hospital, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes, ARC-Net Centre for Applied Research on Cancer, Gönen M, Levine AJ, Allen PJ, Fearon DT, Merad M, Gnjatic S, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Wolchok JD, DeMatteo RP, Chan TA, Greenbaum BD, Merghoub T. & Leach SD Identification of unique neoantigen qualities in long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer. Nature 551, 512–516 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark CE, Hingorani SR, Mick R, Combs C, Tuveson DA & Vonderheide RH Dynamics of the Immune Reaction to Pancreatic Cancer from Inception to Invasion. Cancer Res. 67, 9518–9527 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R, Shimada K, Iwasaki M, Kosuge T, Kanai Y. & Hiraoka N. Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 108, 914–923 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foucher ED, Ghigo C, Chouaib S, Galon J, Iovanna J. & Olive D. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Strong Imbalance of Good and Bad Immunological Cops in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 9, 1044 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang J-E, Hajdu CH, Liot C, Miller G, Dustin ML & Bar-Sagi D. Crosstalk between Regulatory T Cells and Tumor-Associated Dendritic Cells Negates Anti-tumor Immunity in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Rep. 20, 558–571 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liyanage UK, Moore TT, Joo H-G, Tanaka Y, Herrmann V, Doherty G, Drebin JA, Strasberg SM, Eberlein TJ, Goedegebuure PS & Linehan DC Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 169, 2756–2761 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C, Cheng H, Luo G, Lu Y, Jin K, Guo M, Ni Q. & Yu X. Circulating regulatory T cell subsets predict overall survival of patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 51, 686–694 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajina R. & Weiner LM T-Cell Immunity in Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 49, 1014–1023 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Łuksza M, Sethna ZM, Rojas LA, Lihm J, Bravi B, Elhanati Y, Soares K, Amisaki M, Dobrin A, Hoyos D, Guasp P, Zebboudj A, Yu R, Chandra AK, Waters T, Odgerel Z, Leung J, Kappagantula R, Makohon-Moore A, Johns A, Gill A, Gigoux M, Wolchok J, Merghoub T, Sadelain M, Patterson E, Monasson R, Mora T, Walczak AM, Cocco S, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Greenbaum BD & Balachandran VP Neoantigen quality predicts immunoediting in survivors of pancreatic cancer. Nature 606, 389–395 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leidner R, Sanjuan Silva N, Huang H, Sprott D, Zheng C, Shih Y-P, Leung A, Payne R, Sutcliffe K, Cramer J, Rosenberg SA, Fox BA, Urba WJ & Tran E. Neoantigen T-Cell Receptor Gene Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2112–2119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sturm G, Szabo T, Fotakis G, Haider M, Rieder D, Trajanoski Z. & Finotello F. Scirpy: a Scanpy extension for analyzing single-cell T-cell receptor-sequencing data. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 36, 4817–4818 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf FA, Angerer P. & Theis FJ SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 19, 15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borcherding N, Bormann NL & Kraus G. scRepertoire: An R-based toolkit for single-cell immune receptor analysis. F1000Research 9, 47 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF & Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495–502 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E. & Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, Mauck WM, Zheng S, Butler A, Lee MJ, Wilk AJ, Darby C, Zager M, Hoffman P, Stoeckius M, Papalexi E, Mimitou EP, Jain J, Srivastava A, Stuart T, Fleming LM, Yeung B, Rogers AJ, McElrath JM, Blish CA, Gottardo R, Smibert P. & Satija R. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573–3587.e29 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Team I. Immunarch: An R Package for Painless Analysis of Large-Scale Immune Repertoire Data. (2019) doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3383240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoeckius M, Hafemeister C, Stephenson W, Houck-Loomis B, Chattopadhyay PK, Swerdlow H, Satija R. & Smibert P. Simultaneous epitope and transcriptome measurement in single cells. Nat. Methods 14, 865–868 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson VM, Zhang KX, Kumar N, Wong J, Li L, Wilson DC, Moore R, McClanahan TK, Sadekova S. & Klappenbach JA Multiplexed quantification of proteins and transcripts in single cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 936–939 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoeckius M, Zheng S, Houck-Loomis B, Hao S, Yeung BZ, Mauck WM, Smibert P. & Satija R. Cell Hashing with barcoded antibodies enables multiplexing and doublet detection for single cell genomics. Genome Biol. 19, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katzenelenbogen Y, Sheban F, Yalin A, Yofe I, Svetlichnyy D, Jaitin DA, Bornstein C, Moshe A, Keren-Shaul H, Cohen M, Wang S-Y, Li B, David E, Salame T-M, Weiner A. & Amit I. Coupled scRNA-Seq and Intracellular Protein Activity Reveal an Immunosuppressive Role of TREM2 in Cancer. Cell 182, 872–885.e19 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang S-Q, Ma K-Y, Schonnesen AA, Zhang M, He C, Sun E, Williams CM, Jia W. & Jiang N. High-throughput determination of the antigen specificities of T cell receptors in single cells. Nat. Biotechnol. (2018) doi: 10.1038/nbt.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma K-Y, Schonnesen AA, He C, Xia AY, Sun E, Chen E, Sebastian KR, Balderas R, Kulkarni-Date M. & Jiang N. High-Throughput and High-Dimensional Single Cell Analysis of Antigen-Specific CD8+ T cells. bioRxiv 2021.03.04.433914 (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.03.04.433914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joglekar AV & Li G. T cell antigen discovery. Nat. Methods 18, 873–880 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adamson B, Norman TM, Jost M, Cho MY, Nuñez JK, Chen Y, Villalta JE, Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Hein MY, Pak RA, Gray AN, Gross CA, Dixit A, Parnas O, Regev A. & Weissman JS A Multiplexed Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Platform Enables Systematic Dissection of the Unfolded Protein Response. Cell 167, 1867–1882.e21 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixit A, Parnas O, Li B, Chen J, Fulco CP, Jerby-Arnon L, Marjanovic ND, Dionne D, Burks T, Raychowdhury R, Adamson B, Norman TM, Lander ES, Weissman JS, Friedman N. & Regev A. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 167, 1853–1866.e17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaitin DA, Weiner A, Yofe I, Lara-Astiaso D, Keren-Shaul H, David E, Salame TM, Tanay A, Oudenaarden A. van & Amit, I. Dissecting Immune Circuits by Linking CRISPR-Pooled Screens with Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Cell 167, 1883–1896.e15 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie S, Duan J, Li B, Zhou P. & Hon GC Multiplexed Engineering and Analysis of Combinatorial Enhancer Activity in Single Cells. Mol. Cell 66, 285–299.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill AJ, McFaline-Figueroa JL, Starita LM, Gasperini MJ, Matreyek KA, Packer J, Jackson D, Shendure J. & Trapnell C. On the design of CRISPR-based single-cell molecular screens. Nat. Methods 15, 271–274 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Litzenburger UM, Ruff D, Gonzales ML, Snyder MP, Chang HY & Greenleaf WJ Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals principles of regulatory variation. Nature 523, 486–490 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rotem A, Ram O, Shoresh N, Sperling RA, Goren A, Weitz DA & Bernstein BE Single-cell ChIP-seq reveals cell subpopulations defined by chromatin state. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1165–1172 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grosselin K, Durand A, Marsolier J, Poitou A, Marangoni E, Nemati F, Dahmani A, Lameiras S, Reyal F, Frenoy O, Pousse Y, Reichen M, Woolfe A, Brenan C, Griffiths AD, Vallot C. & Gérard A. High-throughput single-cell ChIP-seq identifies heterogeneity of chromatin states in breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 51, 1060–1066 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bartosovic M, Kabbe M. & Castelo-Branco G. Single-cell CUT&Tag profiles histone modifications and transcription factors in complex tissues. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 825–835 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu SJ, Furlan SN, Mihalas AB, Kaya-Okur HS, Feroze AH, Emerson SN, Zheng Y, Carson K, Cimino PJ, Keene CD, Sarthy JF, Gottardo R, Ahmad K, Henikoff S. & Patel AP Single-cell CUT&Tag analysis of chromatin modifications in differentiation and tumor progression. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 819–824 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma S, Zhang B, LaFave LM, Earl AS, Chiang Z, Hu Y, Ding J, Brack A, Kartha VK, Tay T, Law T, Lareau C, Hsu Y-C, Regev A. & Buenrostro JD Chromatin Potential Identified by Shared Single-Cell Profiling of RNA and Chromatin. Cell 183, 1103–1116.e20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lake BB, Chen S, Sos BC, Fan J, Kaeser GE, Yung YC, Duong TE, Gao D, Chun J, Kharchenko PV & Zhang K. Integrative single-cell analysis of transcriptional and epigenetic states in the human adult brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 70–80 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J, Byrne KT, Yan F, Yamazoe T, Chen Z, Baslan T, Richman LP, Lin JH, Sun YH, Rech AJ, Balli D, Hay CA, Sela Y, Merrell AJ, Liudahl SM, Gordon N, Norgard RJ, Yuan S, Yu S, Chao T, Ye S, Eisinger-Mathason TSK, Faryabi RB, Tobias JW, Lowe SW, Coussens LM, Wherry EJ, Vonderheide RH & Stanger BZ Tumor Cell-Intrinsic Factors Underlie Heterogeneity of Immune Cell Infiltration and Response to Immunotherapy. Immunity 49, 178–193.e7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ajina R, Malchiodi ZX, Fitzgerald AA, Zuo A, Wang S, Moussa M, Cooper CJ, Shen Y, Johnson QR, Parks JM, Smith JC, Catalfamo M, Fertig EJ, Jablonski SA & Weiner LM Antitumor T-cell Immunity Contributes to Pancreatic Cancer Immune Resistance. Cancer Immunol. Res. 9, 386–400 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rao A, Barkley D, França GS & Yanai I. Exploring tissue architecture using spatial transcriptomics. Nature 596, 211–220 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lundberg E. & Borner GHH Spatial proteomics: a powerful discovery tool for cell biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 285–302 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hudson WH & Sudmeier LJ Localization of T cell clonotypes using spatial transcriptomics. 2021.08.03.454999 Preprint at 10.1101/2021.08.03.454999 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deng Y, Bartosovic M, Ma S, Zhang D, Kukanja P, Xiao Y, Su G, Liu Y, Qin X, Rosoklija GB, Dwork AJ, Mann JJ, Xu ML, Halene S, Craft JE, Leong KW, Boldrini M, Castelo-Branco G. & Fan R. Spatial profiling of chromatin accessibility in mouse and human tissues. Nature (2022) doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deng Y, Bartosovic M, Kukanja P, Zhang D, Liu Y, Su G, Enninful A, Bai Z, Castelo-Branco G. & Fan R. Spatial-CUT&Tag: Spatially resolved chromatin modification profiling at the cellular level. Science 375, 681–686 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dhainaut M, Rose SA, Akturk G, Wroblewska A, Nielsen SR, Park ES, Buckup M, Roudko V, Pia L, Sweeney R, Berichel JL, Wilk CM, Bektesevic A, Lee BH, Bhardwaj N, Rahman AH, Baccarini A, Gnjatic S, Pe’er D, Merad M. & Brown BD Spatial CRISPR genomics identifies regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 185, 1223–1239.e20 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee KE, Spata M, Bayne LJ, Buza EL, Durham AC, Allman D, Vonderheide RH & Simon MC Hif1a Deletion Reveals Pro-Neoplastic Function of B Cells in Pancreatic Neoplasia. Cancer Discov. 6, 256–269 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gunderson AJ, Kaneda MM, Tsujikawa T, Nguyen AV, Affara NI, Ruffell B, Gorjestani S, Liudahl SM, Truitt M, Olson P, Kim G, Hanahan D, Tempero MA, Sheppard B, Irving B, Chang BY, Varner JA & Coussens LM Bruton Tyrosine Kinase-Dependent Immune Cell Cross-talk Drives Pancreas Cancer. Cancer Discov. 6, 270–285 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Das S, Handler JS, Hajdu CH, Coffre M, Koralov SB & Bar-Sagi D. IL35-Producing B Cells Promote the Development of Pancreatic Neoplasia. Cancer Discov. 6, 247–255 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delvecchio FR, Goulart MR, Fincham REA, Bombadieri M. & Kocher HM B cells in pancreatic cancer stroma. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 1088–1101 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Connor AA & Gallinger S. Pancreatic cancer evolution and heterogeneity: integrating omics and clinical data. Nat. Rev. Cancer 22, 131–142 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiemen AL, Braxton AM, Grahn MP, Han KS, Babu JM, Reichel R, Jiang AC, Kim B, Hsu J, Amoa F, Reddy S, Hong S-M, Cornish TC, Thompson ED, Huang P, Wood LD, Hruban RH, Wirtz D. & Wu P-H CODA: quantitative 3D reconstruction of large tissues at cellular resolution. Nat. Methods 19, 1490–1499 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mizutani Y, Kobayashi H, Iida T, Asai N, Masamune A, Hara A, Esaki N, Ushida K, Mii S, Shiraki Y, Ando K, Weng L, Ishihara S, Ponik SM, Conklin MW, Haga H, Nagasaka A, Miyata T, Matsuyama M, Kobayashi T, Fujii T, Yamada S, Yamaguchi J, Wang T, Woods SL, Worthley D, Shimamura T, Fujishiro M, Hirooka Y, Enomoto A. & Takahashi M. Meflin-Positive Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Inhibit Pancreatic Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 79, 5367–5381 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Helms E, Onate MK & Sherman MH Fibroblast Heterogeneity in the Pancreatic Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 10, 648–656 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Öhlund D, Handly-Santana A, Biffi G, Elyada E, Almeida AS, Ponz-Sarvise M, Corbo V, Oni TE, Hearn SA, Lee EJ, Chio IIC, Hwang C-I, Tiriac H, Baker LA, Engle DD, Feig C, Kultti A, Egeblad M, Fearon DT, Crawford JM, Clevers H, Park Y. & Tuveson DA Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Med. 214, 579–596 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elyada E, Bolisetty M, Laise P, Flynn WF, Courtois ET, Burkhart RA, Teinor JA, Belleau P, Biffi G, Lucito MS, Sivajothi S, Armstrong TD, Engle DD, Yu KH, Hao Y, Wolfgang CL, Park Y, Preall J, Jaffee EM, Califano A, Robson P. & Tuveson DA Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Reveals Antigen-Presenting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 9, 1102–1123 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wood LD, Canto MI, Jaffee EM & Simeone DM Pancreatic Cancer: Pathogenesis, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Gastroenterology 163, 386–402.e1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1605–1617 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dias Carvalho P, Guimarães CF, Cardoso AP, Mendonça S, Costa ÂM, Oliveira MJ & Velho S. KRAS Oncogenic Signaling Extends beyond Cancer Cells to Orchestrate the Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 78, 7–14 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ischenko I, D’Amico S, Rao M, Li J, Hayman MJ, Powers S, Petrenko O. & Reich NC KRAS drives immune evasion in a genetic model of pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 12, 1482 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ling J, Kang Y, Zhao R, Xia Q, Lee D-F, Chang Z, Li J, Peng B, Fleming JB, Wang H, Liu J, Lemischka IR, Hung M-C & Chiao PJ KrasG12D-induced IKK2/β/NF-κB activation by IL-1α and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 21, 105–120 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamarsheh S, Groß O, Brummer T. & Zeiser R. Immune modulatory effects of oncogenic KRAS in cancer. Nat. Commun. 11, 5439 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li K, Tandurella JA, Gai J, Zhu Q, Lim SJ, Thomas DL, Xia T, Mo G, Mitchell JT, Montagne J, Lyman M, Danilova LV, Zimmerman JW, Kinny-Köster B, Zhang T, Chen L, Blair AB, Heumann T, Parkinson R, Durham JN, Narang AK, Anders RA, Wolfgang CL, Laheru DA, He J, Osipov A, Thompson ED, Wang H, Fertig EJ, Jaffee EM & Zheng L. Multi-omic analyses of changes in the tumor microenvironment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma following neoadjuvant treatment with anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Cell S1535–6108(22)00492–5 (2022) doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng GXY, Terry JM, Belgrader P, Ryvkin P, Bent ZW, Wilson R, Ziraldo SB, Wheeler TD, McDermott GP, Zhu J, Gregory MT, Shuga J, Montesclaros L, Underwood JG, Masquelier DA, Nishimura SY, Schnall-Levin M, Wyatt PW, Hindson CM, Bharadwaj R, Wong A, Ness KD, Beppu LW, Deeg HJ, McFarland C, Loeb KR, Valente WJ, Ericson NG, Stevens EA, Radich JP, Mikkelsen TS, Hindson BJ & Bielas JH Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat. Commun. 8, 14049 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ramsköld D, Luo S, Wang Y-C, Li R, Deng Q, Faridani OR, Daniels GA, Khrebtukova I, Loring JF, Laurent LC, Schroth GP & Sandberg R. Full-length mRNA-Seq from single-cell levels of RNA and individual circulating tumor cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 777–782 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amir ED, Krutzik PO, Finck R, Bruggner RV, Melamed R, Trejo A, Ornatsky OI, Balderas RS, Plevritis SK, Sachs K, Pe’er D, Tanner SD & Nolan GP Single-Cell Mass Cytometry of Differential Immune and Drug Responses Across a Human Hematopoietic Continuum. Science 332, 687–696 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gerdes MJ, Sevinsky CJ, Sood A, Adak S, Bello MO, Bordwell A, Can A, Corwin A, Dinn S, Filkins RJ, Hollman D, Kamath V, Kaanumalle S, Kenny K, Larsen M, Lazare M, Li Q, Lowes C, McCulloch CC, McDonough E, Montalto MC, Pang Z, Rittscher J, Santamaria-Pang A, Sarachan BD, Seel ML, Seppo A, Shaikh K, Sui Y, Zhang J. & Ginty F. Highly multiplexed single-cell analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cancer tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 11982–11987 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giesen C, Wang HAO, Schapiro D, Zivanovic N, Jacobs A, Hattendorf B, Schüffler PJ, Grolimund D, Buhmann JM, Brandt S, Varga Z, Wild PJ, Günther D. & Bodenmiller B. Highly multiplexed imaging of tumor tissues with subcellular resolution by mass cytometry. Nat. Methods 11, 417–422 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Angelo M, Bendall SC, Finck R, Hale MB, Hitzman C, Borowsky AD, Levenson RM, Lowe JB, Liu SD, Zhao S, Natkunam Y. & Nolan GP Multiplexed ion beam imaging of human breast tumors. Nat. Med. 20, 436–442 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goltsev Y, Samusik N, Kennedy-Darling J, Bhate S, Hale M, Vazquez G, Black S. & Nolan GP Deep Profiling of Mouse Splenic Architecture with CODEX Multiplexed Imaging. Cell 174, 968–981.e15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ståhl PL, Salmén F, Vickovic S, Lundmark A, Navarro JF, Magnusson J, Giacomello S, Asp M, Westholm JO, Huss M, Mollbrink A, Linnarsson S, Codeluppi S, Borg Å, Pontén F, Costea PI, Sahlén P, Mulder J, Bergmann O, Lundeberg J. & Frisén J. Visualization and analysis of gene expression in tissue sections by spatial transcriptomics. Science 353, 78–82 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodriques SG, Stickels RR, Goeva A, Martin CA, Murray E, Vanderburg CR, Welch J, Chen LM, Chen F. & Macosko EZ Slide-seq: A scalable technology for measuring genome-wide expression at high spatial resolution. Science 363, 1463–1467 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu Y, Yang M, Deng Y, Su G, Enninful A, Guo CC, Tebaldi T, Zhang D, Kim D, Bai Z, Norris E, Pan A, Li J, Xiao Y, Halene S. & Fan R. High-Spatial-Resolution Multi-Omics Sequencing via Deterministic Barcoding in Tissue. Cell 183, 1665–1681.e18 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Merritt CR, Ong GT, Church SE, Barker K, Danaher P, Geiss G, Hoang M, Jung J, Liang Y, McKay-Fleisch J, Nguyen K, Norgaard Z, Sorg K, Sprague I, Warren C, Warren S, Webster PJ, Zhou Z, Zollinger DR, Dunaway DL, Mills GB & Beechem JM Multiplex digital spatial profiling of proteins and RNA in fixed tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 586–599 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ho WJ, Erbe R, Danilova L, Phyo Z, Bigelow E, Stein-O’Brien G, Thomas DL, Charmsaz S, Gross N, Woolman S, Cruz K, Munday RM, Zaidi N, Armstrong TD, Sztein MB, Yarchoan M, Thompson ED, Jaffee EM & Fertig EJ Multi-omic profiling of lung and liver tumor microenvironments of metastatic pancreatic cancer reveals site-specific immune regulatory pathways. Genome Biol. 22, 154 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Raghavan S, Winter PS, Navia AW, Williams HL, DenAdel A, Lowder KE, Galvez-Reyes J, Kalekar RL, Mulugeta N, Kapner KS, Raghavan MS, Borah AA, Liu N, Väyrynen SA, Costa AD, Ng RWS, Wang J, Hill EK, Ragon DY, Brais LK, Jaeger AM, Spurr LF, Li YY, Cherniack AD, Booker MA, Cohen EF, Tolstorukov MY, Wakiro I, Rotem A, Johnson BE, McFarland JM, Sicinska ET, Jacks TE, Sullivan RJ, Shapiro GI, Clancy TE, Perez K, Rubinson DA, Ng K, Cleary JM, Crawford L, Manalis SR, Nowak JA, Wolpin BM, Hahn WC, Aguirre AJ & Shalek AK Microenvironment drives cell state, plasticity, and drug response in pancreatic cancer. Cell 184, 6119–6137.e26 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grünwald BT, Devisme A, Andrieux G, Vyas F, Aliar K, McCloskey CW, Macklin A, Jang GH, Denroche R, Romero JM, Bavi P, Bronsert P, Notta F, O’Kane G, Wilson J, Knox J, Tamblyn L, Udaskin M, Radulovich N, Fischer SE, Boerries M, Gallinger S, Kislinger T. & Khokha R. Spatially confined sub-tumor microenvironments in pancreatic cancer. Cell 184, 5577–5592.e18 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peng J, Sun B-F, Chen C-Y, Zhou J-Y, Chen Y-S, Chen H, Liu L, Huang D, Jiang J, Cui G-S, Yang Y, Wang W, Guo D, Dai M, Guo J, Zhang T, Liao Q, Liu Y, Zhao Y-L, Han D-L, Zhao Y, Yang Y-G & Wu W. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intra-tumoral heterogeneity and malignant progression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Res. 29, 725–738 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Steele NG, Carpenter ES, Kemp SB, Sirihorachai VR, The S, Delrosario L, Lazarus J, Amir ED, Gunchick V, Espinoza C, Bell S, Harris L, Lima F, Irizarry-Negron V, Paglia D, Macchia J, Chu AKY, Schofield H, Wamsteker E-J, Kwon R, Schulman A, Prabhu A, Law R, Sondhi A, Yu J, Patel A, Donahue K, Nathan H, Cho C, Anderson MA, Sahai V, Lyssiotis CA, Zou W, Allen BL, Rao A, Crawford HC, Bednar F, Frankel TL & Pasca di Magliano M. Multimodal mapping of the tumor and peripheral blood immune landscape in human pancreatic cancer. Nat. Cancer 1, 1097–1112 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lin W, Noel P, Borazanci EH, Lee J, Amini A, Han IW, Heo JS, Jameson GS, Fraser C, Steinbach M, Woo Y, Fong Y, Cridebring D, Von Hoff DD, Park JO & Han H. Single-cell transcriptome analysis of tumor and stromal compartments of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma primary tumors and metastatic lesions. Genome Med. 12, 80 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liudahl SM, Betts CB, Sivagnanam S, Morales-Oyarvide V, da Silva A, Yuan C, Hwang S, Grossblatt-Wait A, Leis KR, Larson W, Lavoie MB, Robinson P, Dias Costa A, Väyrynen SA, Clancy TE, Rubinson DA, Link J, Keith D, Horton W, Tempero MA, Vonderheide RH, Jaffee EM, Sheppard B, Goecks J, Sears RC, Park BS, Mori M, Nowak JA, Wolpin BM & Coussens LM Leukocyte Heterogeneity in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Phenotypic and Spatial Features Associated with Clinical Outcome. Cancer Discov. 11, 2014–2031 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chijimatsu R, Kobayashi S, Takeda Y, Kitakaze M, Tatekawa S, Arao Y, Nakayama M, Tachibana N, Saito T, Ennishi D, Tomida S, Sasaki K, Yamada D, Tomimaru Y, Takahashi H, Okuzaki D, Motooka D, Ohshiro T, Taniguchi M, Suzuki Y, Ogawa K, Mori M, Doki Y, Eguchi H. & Ishii H. Establishment of a reference single-cell RNA sequencing dataset for human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. iScience 25, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kinny-Köster B, Guinn S, Tandurella JA, Mitchell JT, Sidiropoulos DN, Loth M, Lyman MR, Pucsek AB, Seppälä TT, Cherry C, Suri R, Zlomke H, He J, Wolfgang CL, Yu J, Zheng L, Ryan DP, Ting DT, Kimmelman A, Gupta A, Danilova L, Elisseef J, Wood LD, Stein-O’Brien G, Kagohara LT, Burkhart RA, Jaffee EM, Fertig EJ & Zimmerman JW Inflammatory Signaling and Fibroblast-Cancer Cell Interactions Transfer from a Harmonized Human Single-cell RNA Sequencing Atlas of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma to Organoid Co-Culture. 2022.07.14.500096 Preprint at 10.1101/2022.07.14.500096 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsujikawa T, Kumar S, Borkar RN, Azimi V, Thibault G, Chang YH, Balter A, Kawashima R, Choe G, Sauer D, Rassi EE, Clayburgh DR, Kulesz-Martin MF, Lutz ER, Zheng L, Jaffee EM, Leyshock P, Margolin AA, Mori M, Gray JW, Flint PW & Coussens LM Quantitative Multiplex Immunohistochemistry Reveals Myeloid-Inflamed Tumor-Immune Complexity Associated with Poor Prognosis. Cell Rep. 19, 203–217 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ramilowski JA, Goldberg T, Harshbarger J, Kloppmann E, Lizio M, Satagopam VP, Itoh M, Kawaji H, Carninci P, Rost B. & Forrest ARR A draft network of ligand–receptor-mediated multicellular signalling in human. Nat. Commun. 6, 7866 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cohen M, Giladi A, Gorki A-D, Solodkin DG, Zada M, Hladik A, Miklosi A, Salame T-M, Halpern KB, David E, Itzkovitz S, Harkany T, Knapp S. & Amit I. Lung Single-Cell Signaling Interaction Map Reveals Basophil Role in Macrophage Imprinting. Cell 175, 1031–1044.e18 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stein-O’Brien GL, Clark BS, Sherman T, Zibetti C, Hu Q, Sealfon R, Liu S, Qian J, Colantuoni C, Blackshaw S, Goff LA & Fertig EJ Decomposing Cell Identity for Transfer Learning across Cellular Measurements, Platforms, Tissues, and Species. Cell Syst. 8, 395–411.e8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Davis-Marcisak EF, Desphande A, Stein-O’Brien GL, Ho WJ, Laheru D, Jaffee EM, Fertig EJ & Kagohara LT From bench to bedside: single-cell analysis for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 39, 1062–1080 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Popovic A, Jaffee EM & Zaidi N. Emerging strategies for combination checkpoint modulators in cancer immunotherapy. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 3209–3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Saxena M, van der Burg SH, Melief CJM & Bhardwaj N. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21, 360–378 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yeo D, Giardina C, Saxena P. & Rasko JEJ The next wave of cellular immunotherapies in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 24, 561–576 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. & Fenselau C. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Immune-Suppressive Cells That Impair Antitumor Immunity and Are Sculpted by Their Environment. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 200, 422–431 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Siret C, Collignon A, Silvy F, Robert S, Cheyrol T, André P, Rigot V, Iovanna J, van de Pavert S, Lombardo D, Mas E. & Martirosyan A. Deciphering the Crosstalk Between Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Regulatory T Cells in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol. 10, 3070 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Christmas BJ, Rafie CI, Hopkins AC, Scott BA, Ma HS, Cruz KA, Woolman S, Armstrong TD, Connolly RM, Azad NA, Jaffee EM & Roussos Torres ET Entinostat Converts Immune-Resistant Breast and Pancreatic Cancers into Checkpoint-Responsive Tumors by Reprogramming Tumor-Infiltrating MDSCs. Cancer Immunol. Res. 6, 1561–1577 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.R W, Kt B, Ra E, Pm O, Ar M, Dl B, C C, Bz S, Ee F, Ej W. & Rh V. Induction of T-cell Immunity Overcomes Complete Resistance to PD-1 and CTLA-4 Blockade and Improves Survival in Pancreatic Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 3, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Byrne KT & Vonderheide RH CD40 Stimulation Obviates Innate Sensors and Drives T Cell Immunity in Cancer. Cell Rep. 15, 2719–2732 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bullock TNJ CD40 stimulation as a molecular adjuvant for cancer vaccines and other immunotherapies. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 19, 14–22 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vonderheide RH CD40 Agonist Antibodies in Cancer Immunotherapy. Annu. Rev. Med. 71, 47–58 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.O’Hara MH, O’Reilly EM, Varadhachary G, Wolff RA, Wainberg ZA, Ko AH, Fisher G, Rahma O, Lyman JP, Cabanski CR, Mick R, Gherardini PF, Kitch LJ, Xu J, Samuel T, Karakunnel J, Fairchild J, Bucktrout S, LaVallee TM, Selinsky C, Till JE, Carpenter EL, Alanio C, Byrne KT, Chen RO, Trifan OC, Dugan U, Horak C, Hubbard-Lucey VM, Wherry EJ, Ibrahim R. & Vonderheide RH CD40 agonistic monoclonal antibody APX005M (sotigalimab) and chemotherapy, with or without nivolumab, for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 22, 118–131 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Padrón LJ, Maurer DM, O’Hara MH, O’Reilly EM, Wolff RA, Wainberg ZA, Ko AH, Fisher G, Rahma O, Lyman JP, Cabanski CR, Yu JX, Pfeiffer SM, Spasic M, Xu J, Gherardini PF, Karakunnel J, Mick R, Alanio C, Byrne KT, Hollmann TJ, Moore JS, Jones DD, Tognetti M, Chen RO, Yang X, Salvador L, Wherry EJ, Dugan U, O’Donnell-Tormey J, Butterfield LH, Hubbard-Lucey VM, Ibrahim R, Fairchild J, Bucktrout S, LaVallee TM & Vonderheide RH Sotigalimab and/or nivolumab with chemotherapy in first-line metastatic pancreatic cancer: clinical and immunologic analyses from the randomized phase 2 PRINCE trial. Nat. Med. 28, 1167–1177 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Steinman RM & Mellman I. Immunotherapy: Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered No More. Science 305, 197–200 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Medetgul-Ernar K. & Davis MM Standing on the shoulders of mice. Immunity 55, 1343–1353 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sharma G, Colantuoni C, Goff LA, Fertig EJ & Stein-O’Brien G. projectR: an R/Bioconductor package for transfer learning via PCA, NMF, correlation and clustering. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 36, 3592–3593 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Davis-Marcisak EF, Fitzgerald AA, Kessler MD, Danilova L, Jaffee EM, Zaidi N, Weiner LM & Fertig EJ Transfer learning between preclinical models and human tumors identifies a conserved NK cell activation signature in anti-CTLA-4 responsive tumors. Genome Med. 13, 129 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tan Y. & Cahan P. SingleCellNet: A Computational Tool to Classify Single Cell RNA-Seq Data Across Platforms and Across Species. Cell Syst. 9, 207–213.e2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Peng D, Gleyzer R, Tai W-H, Kumar P, Bian Q, Isaacs B, da Rocha EL, Cai S, DiNapoli K, Huang FW & Cahan P. Evaluating the transcriptional fidelity of cancer models. Genome Med. 13, 73 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brubaker DK, Paulo JA, Sheth S, Poulin EJ, Popow O, Joughin BA, Strasser SD, Starchenko A, Gygi SP, Lauffenburger DA & Haigis KM Proteogenomic Network Analysis of Context-Specific KRAS Signaling in Mouse-to-Human Cross-Species Translation. Cell Syst. 9, 258–270.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Baraban A, Clark BS, Slosberg J, Fertig EJ, Goff LA & Stein-O’Brien G. Identifying Gene-wise Differences in Latent Space Projections Across Cell Types and Species in Single Cell Data using scProject. 2021.08.25.457650 Preprint at 10.1101/2021.08.25.457650 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]