Abstract

Objective

Quality of life (QoL) in breast cancer patients is still an important topic. Despite numerous quantitative scales, qualitative studies can help to in-depth understand the QoL of breast cancer patients. The purpose of this systematic review was to integrate qualitative studies on the QoL of women with breast cancer.

Methods

A literature search was performed in electronic databases including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from January 1, 2010 until June 28, 2022 to find out qualitative studies assessing breast cancer patient’s QoL. Two authors independently evaluated methodological quality according to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist. Data were extracted and reported by themes for cancer-free women and patients with metastatic cancer separately.

Results

In all, 1565 citations were retrieved. After removing 1387 duplicate and irrelevant papers, the full texts of 27 articles were reviewed and finally, 9 were eligible for evaluation. In quality checking of the citations, all articles gained the required quality score. After examining and merging similar topics, nine major themes were extracted. Physical, spiritual, and psychological aspects of QoL were the common issues in cancer-free women (before and after the COVID-19 pandemic) and patients with metastatic cancer. Perception of cancer and social life were the other main concerns in cancer-free women, whereas, in metastatic patients’ overall survival and planning for the future and their children’s life was the focus of interest. Women with metastatic disease showed more vulnerability in coping compared to cancer-free women.

Conclusion

This review provides an opportunity to have a closer look into the several domains of QoL in women with breast cancer. In-depth information provided by this review might help to develop interventions for patients and their families to support women to cope much better with their life challenges.

Keywords: qualitative study, breast cancer, quality of life

Introduction

Breast cancer is a challenging phenomenon with physical, emotional, and practical impacts, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases annually and a 7% mortality rate. 1 The incidence rates are 1 in 4 in all cancer cases and 1 in 6 cancer deaths, ranking first for incidence in both transitioned and transitioning countries. 1 Recently with the advances in treatment and healthcare services, the number of breast cancer survivors is developing, and the mortality rate is decreasing. Therefore, there is a growing trend to better understand and manage the sequels of cancer and its treatment including both emotional and physical needs among survivors. 2

Breast cancer patients’ quality of life (QoL) is severely reduced with the cancer symptoms and side effects of the therapies. Indeed, physical and psychosocial functioning, family life, couple relations, and working ability affect the QoL in this population. 3 While there has been a growth in the literature to identify the needs of breast cancer survivors or affected cases with various stages, evidence-based, effective, and adaptable interventions for care are scarce. 4 Thus, many interventions are complex and require an in-depth understanding of the single experiences of these specific populations. Indeed, the majority of the literature is quantitative in nature by validated tools to measure the QoL. 5

Qualitative researches are a valuable approach to the psychosocial and contextual assessment of chronic conditions such as cancer, that explores the participants’ lived experiences. 6 There is also a quantitative approach to measure QoL, such as 36 items short form survey (SF-36). 7 Quantitative QoL studies mostly have similar designs and report calculated scores that could be combined in a meta-analysis, providing high-quality evidence. On the other hand, qualitative studies are harder to combine and the reliability of their conclusions is limited, but these studies include important details that could be missed in a qualitative study. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis authors included studies reporting QoL scores by different questionaries and combined their findings. they reported a significant relationship between age and QoL scores among BC patients 8 and a new comprehensive summary of qualitative research among breast cancer patients is missing. A valuable article up to 2010 collected and reported qualitative articles concerning the QoL in breast cancer patients. 9 Therefore, this study aimed to review and integrate the qualitative studies for understanding the QoL in breast cancer with the view to improve our understanding of the impact of breast cancer on the patient and survivor’s life to create new strategies to support them.

Methods

This current systematic review was designed to integrate and present the main concerns that affect the QoL in patients with active breast cancer and cancer-free women (after treatment) in the recent 12 years. The primary objective of this study was to answer these questions:

(1) What aspects of the life of quality most strongly affected women with breast cancer?

(2) What is the difference between QoL concerns in disease-free patients and those with a metastatic diagnosis?

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were all original articles from 1st January 2010 to June 28, 2022 that qualitatively evaluated the QoL in women with breast cancer. The criteria for women were being over 18 years old with current breast cancer in any stage or cancer-free women (after treatment). The cancer-free women were in remission and not under current treatment. The review articles, opinion pieces or guidelines, conference abstracts, non-peer-reviewed papers, case reports or series, unpublished reports, and articles in which the date and location of the study were not specified were excluded. The studies on other cancer types were not eligible too. The mixed-method studies or those with quantitative methods were excluded either. The articles with English abstracts with full text in other languages were also excluded.

Information Sources

The initial search was undertaken in three main databases including MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search was updated twice once in July and once in September 2022.

Search Strategy

For the search strategy, combinations of the following keywords based on the medical subject heading (MeSH) were used. The initial searched terms were “breast cancer”, “QoL”, “qualitative study” and “woman”. Keywords and their combinations that were used for the search strategy are listed in Supplement 1. The mentioned time limits were also applied in all databases.

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed for eligibility by two authors and non-relevant or duplicate studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. In cases of disagreement, the problem was resolved by discussion. After the initial screening, the full texts were reviewed by another author.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the articles was evaluated by the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist. 10 A criterion of six out of ten points was established as the minimum score to qualify a study for extraction. This level was chosen because it was considered high enough to establish a level of methodological rigor.

Data Collection

Two authors extracted the required information from selected studies. In cases of disagreement, the problem was resolved by discussion between them.

Data Extraction

The qualitative data were extracted from the articles by a standardized data extraction tool from Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI-QARI) which is specific for the qualitative studies. The data extracted included specific details about the population including active cancer or cancer-free women, phenomena of interest, country, study methods, and outcomes of significance.

Data Synthesis

The qualitative data were extracted, summarized, and reported as themes for cancer-free women and patients with metastatic cancer separately.

Results

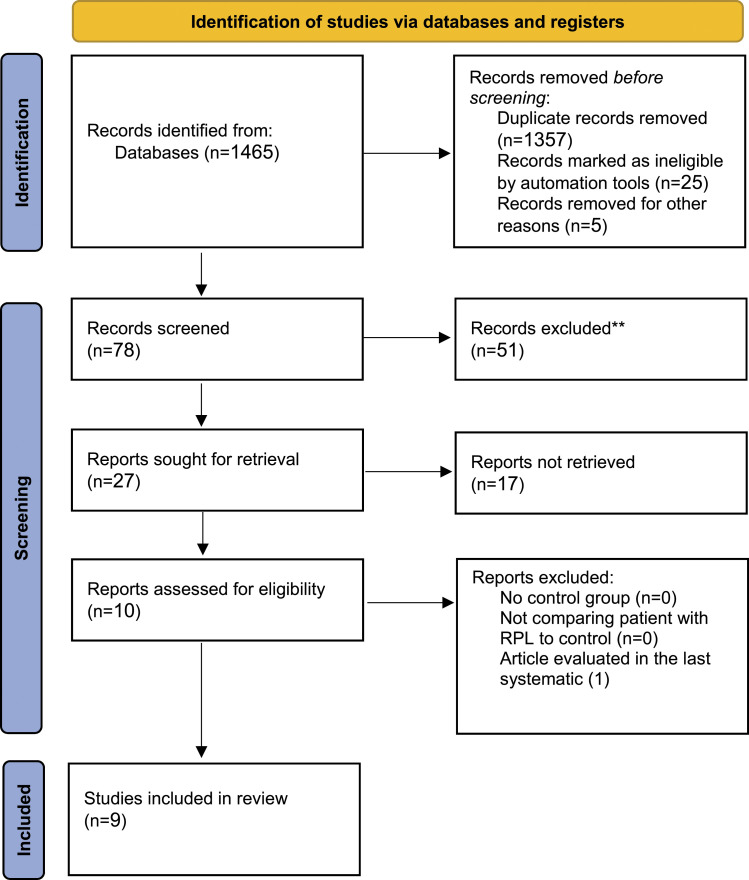

The database search led to finding 1465 articles. Detailed screening of titles and abstracts for potential eligibility was performed, 1357 were duplicated, and the irrelevant papers were removed. According to inclusion and exclusion criteria, the full texts of 27 articles were reviewed and 19 articles were subsequently excluded and finally, 9 full papers11–20 were retrieved for detailed examination. In further assessment, one article 12 was omitted because it was evaluated in the last systematic review by Devi et al. 9 (Figure 1). The characteristics of each article are detailed in Table 1. The papers were divided into 2 categories according to the affected women.

(1) Articles related to the QoL of breast cancer-free women (5 articles).

(2) Articles related to the QoL of metastatic breast cancer patients (4 articles).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the recruiting studies according to PRISMA.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Reporting QoL of Breast Cancer Survivors.

| Authors | Year | Country | Data collection methods | Phenomena of Interest | Population | Main Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lopez-Class 1 | 2011 | USA | Interview and focused group | Secrecy/shame about a breast cancer diagnosis, feelings of isolation, importance of family support challenges with developing social relationships | Breast cancer survivors |

Adherence to certain cultural values and face unique issues as immigrants, doctor-patient communicationn. Efforts to improve immigrant breast cancer survivors |

| Jassim 2 | 2014 | Bahrain | Interview transcripts | Meaning of cancer and quality of life, spirituality and beliefs about causes of breast cancer, coping mechanisms, impact of illness and change in relationships. | Breast cancer survivors |

The use of traditional clothing to hide hair

and body changes; the important role played by the family

and husband in treatment decisions and concerns regarding

satisfying the sexual needs of the husband, which were

related to a fear of losing The husband to a second wife. Evil eye, stress and God’s punishment were believed to be fundamental causes of the disease. The emotional shock of the initial diagnosis, concerns about whether to reveal the diagnosis and a desire to live a normal life were consistent with previous studies. |

| Jassim 2 | 2014 | Bahrain | Interview transcripts | Meaning of cancer and quality of life, spirituality and beliefs about causes of breast cancer, coping mechanisms, impact of illness and change in relationships. | Breast cancer survivors | The use of traditional clothing to hide hair

and body changes; the important role played by the family

and husband in treatment decisions And concerns regarding satisfying the sexual needs of the husband, which were related to a fear of losing the husband to a second wife. Evil eye, stress and God’s punishment were believed to be fundamental causes of the disease. The emotional shock of the initial diagnosis, concerns about whether to reveal the diagnosis and a desire to live a normal life were consistent with previous studies. |

| Radina 3 | 2019 | USA | Interviewed in person or over the phone | Psychological and/or affectional closeness, family communication, and social support. | Breast cancer survivors | Positive perceptions prior to diagnosis also reported positive perceptions after diagnosis. |

| Nolan 4 | 2019 | USA | Semi-structured interviews. | Managing spiritual, physical, psychological social, and 5 seeking survivorship knowledge. | Breast cancer survivors | Implementing targeted survivorship interventions, accounting for cultural contexts (e.g. high spirituality) |

1Lopez-Class, M., et al., Quality of life among immigrant Latina breast cancer survivors: realities of culture and enhancing cancer care. J Cancer Educ, 2011. 26(4): p. 724-33.

2Jassim, G.A. and D.L. Whitford, Understanding the experiences and quality of life issues of Bahraini women with breast cancer. Soc Sci Med, 2014. 107: p. 189-95.

3Elise Radina, M., et al., Elucidating emotional closeness within the Theory of Health-Related Family Quality of Life: evidence from breast cancer survivors. BMC Res Notes, 2019. 12(1): p. 312.

4Nolan, T.S., et al., Life after breast cancer: ‘Being’ a young African American survivor. Ethn Health, 2019: p. 1-28.

After examining and merging similar topics, nine major themes were extracted and were reported separately in breast cancer-free women and metastatic breast cancer patients (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Studies Reporting QoL of Breast Cancer Survivors.

| Authors | Year | Country | Data collection methods | Phenomena of Interest | Population | Main Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McClelland 1 | 2015 | USA | Semi-structured interviews | sexual quality of life | Metastatic breast cancer | (1) Unexpected embodied loss and mourning; (2) silences; (3) desires for others’ expertise, and (4) worries about normalcy. Findings across these themes highlighted how patients’ psychosexual needs included both pressing instrumental needs as well as desires for support from oncological medical providers concerning the subjective experience of breast cancer. |

| Lee Mortensen 2 | 2018 | Denmark | Focus group interviews | physical and psychosocial functioning | Metastatic breast cancer | a shift in expectations from quantity to quality of life and a perpetual adaptation of their QoL standards. |

| Ginter 3 | 2020 | USA | Semi-structured interviews | Facing off-time diagnoses, strategizing disclosure, relying on mindfulness and spirituality, contemplating the future, and differentiating surviving fom truly living. | Metastatic breast cancer | The notion of short-term or long-term decisionmaking is clouded by a metastatic prognosis. |

1McClelland, S.I., “I wish I’d known”: patients' suggestions for supporting sexual quality of life after diagnosis with metastatic breast cancer. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 2015.

2Lee Mortensen, G., et al., Quality of life and care needs in women with estrogen positive metastatic breast cancer: a qualitative study. Acta Oncol, 2018. 57(1): p. 146-151.

3Ginter, A.C., “The day you lose your hope is the day you start to die”: Quality of life measured by young women with metastatic breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol, 2020. 38(4): p. 418-434.

Table 3.

The Extracted Themes of Each Article.

| Survivors | Metastatic |

|---|---|

| Radina 2019 USA emotional

closeness Communication family |

Ginter 2020 USA Coping Life stage After life End life plan Future Mindfulness Positive energy |

| Gassim 2014

Bahrain Perception Talk with other cancer women Other’s role Sexuality Recurrent of cancer Spirituality Other’s reaction Physical issues Cause of cancer |

Lee mortensen 2018

Denmark Shocking Coping Their children future Cognitive problem |

| Lopez 2011 USA Worry about treatment Spirituality Loneliness Fatalism Husband and family relationship Communication with caregiver |

Mc celled 2015 USA sexuality |

| Nolan 2019

USA Spirituality Hope Life goal Future Physical issues Sociality sexuality |

The Major Themes of the Quality of Life in Breast Cancer-free Women

Perception of Cancer

In reviewed studies, the perception of breast cancer before diagnosis among patients was associated with death and fear, although they accepted breast cancer as a chronic and long-lasting illness after diagnosis. Fear of recurrence was also a big and challenging issue in these women.13,15 The Asian women’s perception of cancer was equal to stress and sadness in their lives, some of them also assumed they were being envied by others (the evil eye), and some others considered cancer a punishment from God. 13 Survivors also experienced distress about their capability to return to normal life. 17

Physical Effects

Included studies reported that total mastectomy or local resections of breast masses disrupt body image and lead to low self-esteem. Indeed, chemotherapy and radiotherapy cause hair loss and arm pain which are associated with enormous limitations in daily activities. 13 . Patients had to deal with these problems and should figure out ways to adjust to them.17,19

Psychological and Spiritual Effects

Some women described adequate and satisfying emotional closeness both before and after diagnosis. However, others spoke negatively about the psychological closeness. 18 Anxiety and depression were reported in 20-30% of the patients.13,15 In addition, one of the most common feelings that were mentioned in all studies was fear. Patients were afraid of the recurrence of cancer or cancer becoming metastatic. In addition, cancer-free women were worried about their daughters experiencing their disease.12,13,15,17 Another feeling was guilt. Some patients blamed themselves. They were questioning why God spared them. Patients also felt guilty to be survived. 17

One of the things that happened to these people is the pandemics’ fear of COVID-19 infection. 19

“I never leave the house, except for the hospital. I always keep my gloves, mask, and distance while out. I disinfect myself. But here we are stuck in the houses. I never went out because I am chronically ill. I guess that thought made me collapse.”

The Family Role, Social Effects, and Interpersonal Relations

Several women felt lonely and were less likely to socialize. On the other hand, some others mentioned that after the diagnosis, the support they received was improved. 15 Emotional support of the families was a major factor in the QoL of these women. 12 During the process of treatment, patients might not be able to continue their duties as mothers and wives. 19 How families reacted to this disease was very important. The women mentioned that they were seeking sympathy and being pitied; they wanted to be understood and treated like healthy people. 12 Family’s physical presences were also very important and helping patients with their daily chores and assisting them to cope easier with cancer. 18 It was important of having their children around. 17 Most patients reported that they received satisfying support and a positive role from their husbands, which was accompanying in appointments and helping them out with housework. 13 Nevertheless, sometimes the women could not be supported very effectively. The cultural values and beliefs must be considered in this issue. 15 On the contrary, some of the women described a tension that made their husbands collapse. Cancer in others is with a fear of losing their husband or divorce. 13

First, I think that a husband plays the main role in understanding that a patient cannot do many things, so he should work with his wife and make some changes in his life. I scolded my husband, arguing that you are the only person who should understand my problems, but you are the only person who does not understand! 21

Sexual life difficulties were also discussed and many patients talked about this issue. Loss of libido, impaired body image, and vaginal dryness were the reasons for sexual life problems. Some women noticed that they were obligated to engage in sexual activities by their husbands15,17 and mentioned sexual concerns were like an elephant in the bedroom. The women with a positive vision of sexuality had more supportive husbands as compared to those with negative views. 17

Breast cancer also influenced children in the family. It was a big challenge for them and some patients even decide to hide their condition from them. It was mentioned that some children faced problems in school during the process of their mother’s illness. 15

Healthcare providers had a great role in managing breast cancer patients. They are also a source of information. Knowledge about BC helps women to cope with breast cancer. In the study of Lorenz et al., patients noticed as Latino immigrants they faced lingual barriers to contact their healthcare providers, which caused some serious problems such as changes in the treatment process. 15 In the study by Radina et al. 18 most of the patients talked positively about the effect of healthcare support, but they also mentioned that when doctors include their families counseling was more helpful.

Talking with another breast cancer patient was good. Therefore others felt uncomfortable communicating with other patients, as many tended to cancer-free women exaggerate their experience causing unnecessary stress to the newly diagnosed cases. 13

Social stigmatization was the main problem in this section. Patients felt like they were losing their social identity and being labeled as cancer patients which made them feel killed and debilitated to the extent that they did not want anyone but their family knew about that. 13 Other women tend to hide their emotional feelings about their illness from their relatives and, children. 15

“I hated the way people were looking at me. They made me feel miserable and pathetic. They would say: “We feel sorry for you, you don’t deserve it”. I can hear the sorrow and grief in their voices.”

“There’s always the doubt and fear of the disease, but I don’t tell them either.”

Patients did not want to be identified as sick and weak. They needed to be treated like a healthy person and annoying sympathies make patients frustrated.12,13 Patients knew that they need to make adjustments in their social lives but they wanted to be the person making this adjustment.

Working is a stress reliever. It also helps patients to reestablish their social identity. Patients wanted to be identified by their careers and not their diseases. However, financial hit due to healthcare bills puts pressure on patients and their families. Some women had gotten days off and even lost their jobs, which increases the pressure on them.

The COVID-19 pandemic may lead to more limited social interaction. Indeed, having a family member with COVID-19 or social distancing at home may affect their social QoL. 19

Coping and Adjustment

Patients employ different strategies to deal with their challenges. Spirituality and religiosity were two main subjects that were mentioned in most studies. Relation with God helped patients to gain comfort and accept the disease. 15 Relationship with God is introduced as a source of strength in dealing with a cancer diagnosis.13,15 Muslims find blessing God, praying, and reading the Holy Quran a helpful instrument. They believed God has full control over their disease. Headcover served a dual role: both a religious role and to hide baldness in this population. 13

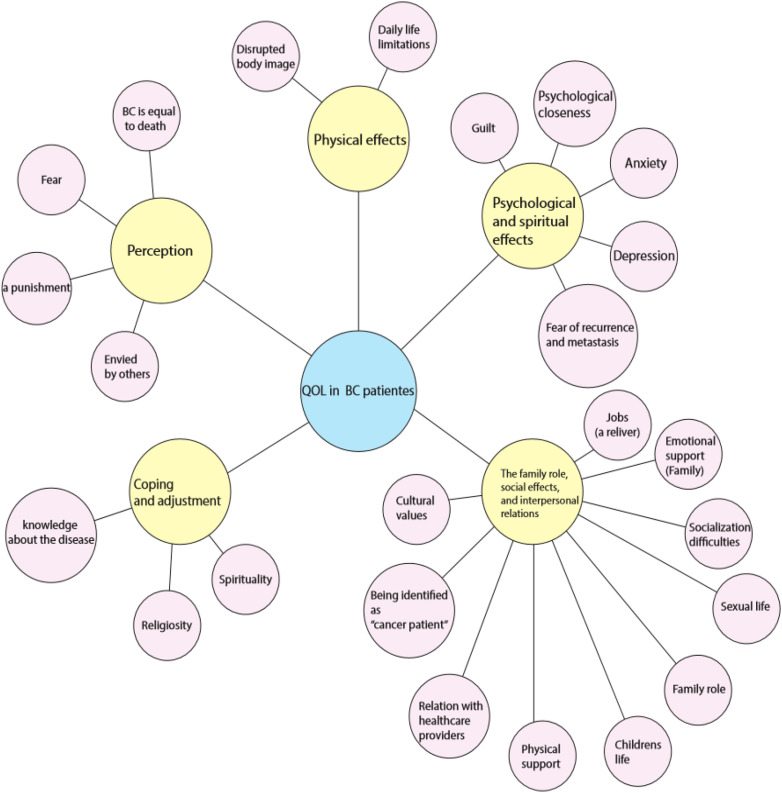

Another subject that helped patients to cope with breast cancer was knowledge about the disease. Seeking knowledge helped patients to answer their questions and throw light on their path of treatment. 17 Some patients mentioned activities such as making rugs, painting, etc. helping them to free their minds. Self-reliance help cancer-free women to identify themselves as a strong and capable person, even in the face of illness. 15 Cancer-free women said the transition from patient to a survivor was difficult that left them with unanswered questions about how their new lives would unfold. Some women regularly attended counseling sessions. These coping strategies strengthened their resolve to continue to move forward in life and survivorship. 17 Figure 2 summarizes the factors associated with QoL of breast cancer-free women.

Figure 2.

Factors associated with the quality of life of breast cancer survivors Abbreviation: QoL: Quality of life, BC: Breast cancer.

The Major Themes of the Quality of Life in Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients

Overall Survival

The main item in women with metastatic breast cancer is overall survival. Also, they believe that improved QoL is important that may vary by age, duration of illness, and treatment modalities. 20

Physical Effects

Physical QoL and activity was severely diminished by symptoms such as severe pain, nausea, gastrointestinal discomfort, flu-like symptoms, cardiovascular dysfunction, edema, stomatitis, neuropathies, muscles and joints stiffness, dyspnea, dizziness, sleep problems, hair loss and menopausal symptoms. 14 Many participants described cognitive problems with memory and concentration but none felt this significantly reduced their QoL. 14 In addition, the patients mentioned their partners needed more information about the sexual changes that patients were experiencing. The couples were in a position of being “in the dark” which was challenging for them. 16

Shocking

All participants described the combined shock of being young and diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. Patients mentioned it was too soon for them and it was shocking for them to think about death at a young age. Other patients experienced the recurrence of their cancer more dangerously and they liked losing their hope for a peaceful long life. 11 Women who had previously been diagnosed with an earlier stage of breast cancer were concerned about how they would be perceived as metastatic patients now. 11

“The reaction is kind of a little soberer, whereas the first time I was diagnosed it was like, it was just instant panic."

Children Live and Plan for Future

“My first thoughts were, I hope I live long enough to see my nephew being born and to watch him grow up.”

Planning for future life was not easy which affected their QoL. 11 Although distressing, many found that they needed to get things sorted. Making arrangements for the funeral enabled a feeling of control and focus. 14 Many women also explained the need to live in the present. Some participants with recurrent metastatic cancer described a shift in their spiritual needs from their first diagnosis to their second diagnosis. 11

Children’s welfare was the main concern for these women, especially new mothers. 14 Some patients wrote letters for special future occasions of their children. 14

Discussion

Over the last decade, many instruments have been developed to assess the QoLin breast cancer patients. 22 Otherwise, qualitative studies have been identified as an important and appropriate way to answer the research questions focused on discovering the complicated phenomenon likewise the QoL domains. 23 Measuring the QoL in patients with cancers is suboptimal 24 as it may be directly influenced by cancer and its treatment.

Breast cancer is like a journey on a winding road. During this condition, some factors work as motivators and lots of others make patients suffer. In this study, we examined the QoL in cancer-free women and patients with active metastatic disease. In cancer-free women, physical, sexual, and emotional issues as well as the family role were important, whereas, in the patients with metastatic breast cancer, future life, end-life plan, and their children besides physical and mental issues were the main concerns. Coping strategies were evident in both populations and were more prominent in the metastatic group.

One of the strengths of this study was the geographical distribution of the studies that covered the Europa, Asia, and American regions. Due to ethnic and racial differences, this scope can identify more aspects of patient’s QoL aspects and express differences in concerns of these women. For example, the role of God, religious activities, and spirituality were much more prominent in Asian Muslim women. 13 Feeling fear, 25 guilty 26 and worries about themselves and their close ones 12 were bold in all. Although the panic of recurrence of the disease was a common concern in cancer-free women.13,15

Patients experienced physical symptoms due to the nature of the disease and as side effects of the treatment modalities. The results of the present study revealed that most of the women frequently cited physical problems as creating some degree of interference with their normal life. Therefore, physical support could be helpful because the patients worry about their physical duties and treatment difficulties. 17 Their sexual life also would change due to impaired body image, loss of libido, and hormonal changes.13,16,17

The family and children could be great support and motivation to move forward. In most cases, closeness after diagnosis in a positive way was reported. Otherwise, in some families, the husbands were not emotionally supportive. Most women were worried about what would happen to their children if they die.15,18 The social life of these patients was endangered. Social stigmata force them to identify themselves as “cancer patients” and society starts reacting inappropriately. Some patients lost their jobs, and some others could not do their work properly. 17 Working places and communities could help them to save the social role. Now without jobs, patients started to feel like they are losing their identity as a member of society. 22

Diagnosis of breast cancer tends to challenge individuals to reflect. Mindfulness and positive energy may help the patients to cope with difficulties. 11 Religion and spirituality potentially mediated the QoL by enhancing a patient’s well-being In a similar study, Devi et al. 9 found religion and spirituality to help patients cope with cancer in lots of aspects. Knowledge was a key factor, in a study by Rustøen 27 et al. they concluded that lack of information causes fear and anxiety in patients. This statement was also mentioned in a study by Mokhatri Hesari et al. 22 that reviewed review articles about health-related QoL in breast cancer patients. They concluded that some interventions such as physical activity and psychological support improved QoL.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a concern among cancer patients about the vulnerability of corona infection. This pandemic seems to effects the physical, psychological, and social aspects of the QoL of cancer survivors which need to be considered in future studies. 19

Finally, we can say that listening to BC patients and encouraging them to talk more, by removing barriers such as language barriers and stigmata, is the most beneficial action that could be taken to improve their QoL. Better understanding and sympathy among family members and caregivers could provide more functional support systems for them. All patients should have easy access to knowledge about their condition. As mentioned previously knowledge is a key factor in coping with breast cancer.

Limitation

We searched three main databases and therefore we did not identify potential studies that were published in other databases due to the language barrier, we just evaluated the English studies. Another limitation of the review was the paucity of qualitative studies focusing solely on the impact on QoL from the perspective of women diagnosed with or treated for breast cancer. Although it must be noted that this study does not include quantitative analysis and this could exaggerate or underestimate some findings.

Conclusion

This review provides insight into the several domains of QoL in women with breast cancer either cancer-free women or patients with metastatic disease. In-depth information provided by this review might help to develop interventions for patients and their families to support women to cope much better with their life challenges.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the personnel of the Vali-e-Asr Reproductive Health Research Center for their kind support.

Appendix.

Abbreviations

- QoL

quality of life

- COREQ

consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research

- JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

- Mesh

medical subject heading

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: Z.H. and B.HR: Design of the work,. M.G: Drafting the manuscript, A.M: Manuscript editing, Interpretation of data, O.KG: Manuscript editing.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Ethical committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved this study by reference number: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1400.073.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used during the current study all are included in the manuscript.

ORCID iD

Marjan Ghaemi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2306-7112

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson A, Addington-Hall J, Amir Z, Foster C, Stark D, Armes J, et al. Knowledge, ignorance and priorities for research in key areas of cancer survivorship: Findings from a scoping review. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(suppl 1):S82-S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krigel S, Myers J, Befort C, Krebill H, Klemp J. ‘Cancer changes everything!’ Exploring the lived experiences of women with metastatic breast cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20(7):334-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng HS, Vitry A, Koczwara B, Roder D, McBride ML. Patterns of comorbidities in women with breast cancer: A Canadian population-based study. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(9):931-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: A bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473-483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javan Biparva A, Raoofi S, Rafiei S, Pashazadeh Kan F, Kazerooni M, Bagheribayati F, et al. Global quality of life in breast cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022; bmjspcare-2022-003642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devi KM, Hegney DG. Quality of life in women during and after treatment for breast cancer: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2011;9(58):2533-2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginter AC. “The day you lose your hope is the day you start to die”: Quality of life measured by young women with metastatic breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(4):418-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harandy TF, Ghofranipour F, Montazeri A, Anoosheh M, Bazargan M, Mohammadi E, et al. Muslim breast cancer survivor spirituality: Coping strategy or health seeking behavior hindrance? Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(1):88-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jassim GA, Whitford DL. Understanding the experiences and quality of life issues of Bahraini women with breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2014;107:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Mortensen G, Madsen IB, Krogsgaard R, Ejlertsen B. Quality of life and care needs in women with estrogen positive metastatic breast cancer: A qualitative study. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(1):146-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Class M, Perret-Gentil M, Kreling B, Caicedo L, Mandelblatt J, Graves KD. Quality of life among immigrant Latina breast cancer survivors: Realities of culture and enhancing cancer care. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(4):724-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClelland SI. I wish i'd known”: Patients’ suggestions for supporting sexual quality of life after diagnosis with metastatic breast cancer. Sex Relatio Ther. 2015;31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nolan TS, Ivankova N, Carson TL, Spaulding AM, Dunovan S, Davies S, et al. Life after breast cancer: ‘Being’ a young African American survivor. Ethn Health. 2019;27:1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elise Radina M, Deer BL, Herriman RA, Jagpal A, Dodd MM, Kawamura KL, et al. Elucidating emotional closeness within the theory of health-related family quality of life: Evidence from breast cancer survivors. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seven M, Bagcivan G, Pasalak SI, Oz G, Aydin Y, Selcukbiricik F. Experiences of breast cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(11):6481-6493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mertz S, Benjamin C, Girvalaki C, Cardone A, Gono P, May SG, et al. Progression-free survival and quality of life in metastatic breast cancer: The patient perspective. Breast. 2022;65:84-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harandy TF, Ghofranipour F, Montazeri A, Anoosheh M, Mohammadi E, Ahmadi F, et al. Health-related quality of life in iranian breast cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Appl Res Qual Life. 2010;5:121-132. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mokhtari-Hessari P, Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: Review of reviews from 2008 to 2018. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirali E, Yarandi F, Ghaemi M, Montazeri A. Quality of life in patients with gynecological cancers: A web-based study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(7):1969-1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, latina and caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho Oncol. 2004;13(6):408-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrell BR, Grant MM, Funk B, Otis-Green S, Garcia N. Quality of life in breast cancer survivors as identified by focus groups. Psycho Oncol. 1997;6(1):13-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rustoen T, Begnum S. Quality of life in women with breast cancer: A review of the literature and implications for nursing practice. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23(6):416-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]