Abstract

Herein, we disclose an interrupted deaminative Ni-catalyzed chain-walking strategy that forges sp3–sp3 architectures at remote, yet previously unfunctionalized, methylene sp3 C–H sites enabled by the presence of native amides. This protocol is characterized by its mild conditions and wide scope, including challenging substrate combinations. Site-selectivity can be dictated by a judicious choice of the ligand, thus offering an opportunity to enable sp3–sp3 bond formations that are otherwise inaccessible in conventional chain-walking events.

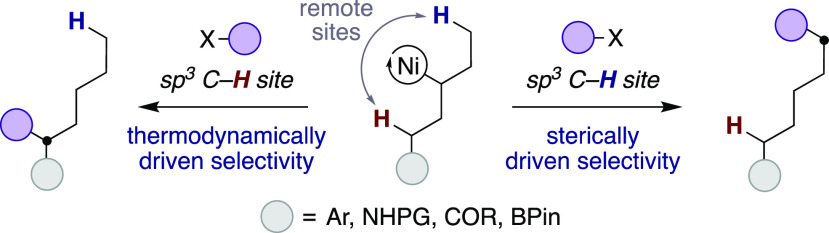

The ability to selectively functionalize sp3 C–H bonds has received considerable attention in medicinal chemistry programs.1,2 Their popularity arises from the observation that drugs possessing a higher content of sp3-hybridized carbons are oftentimes more selective and deliver higher success in clinical trials.3 Recently, Ni-catalyzed chain-walking of unactivated olefins has gained momentum as a powerful, yet practical, alternative to commonly adopted sp3 C–H functionalization strategies,1 allowing to promote innovative bond disconnections for forging sp3 architectures from simple, yet abundant, precursors.4 Despite the advances realized, site-selectivity in Ni-catalyzed chain-walking reactions is predominantly dictated by a subtle interplay between electronic and steric effects. Indeed, bond formation typically takes place adjacent to a stabilizing group on thermodynamic grounds,5 whereas functionalization at distal, primary sp3 C–H bonds is kinetically preferred (Scheme 1).6

Scheme 1. Canonical Ni-Catalyzed Chain-Walking Events.

Recent elegant disclosures have illustrated the viability for targeting other sp3 C–H sites within the alkyl side chain with strongly chelating bidentate 8-aminoquinoline,7 thioethers,8 protected amines,9 or transient directing groups via ketimine formation10 by utilizing alkyl/aryl halides or electrophilic nitrogen sources (Scheme 2, top). Driven by the prevalence of alkyl amines in a myriad of biologically relevant molecules and preclinical candidates,11 we wondered whether we could establish “a la carte” site-selective interrupted Ni-catalyzed deaminative12 chain-walking for forging sp3–sp3 linkages at the always elusive methylene sp3 C–H bonds with predictable and tunable selectivity by using weakly coordinating native amides (Scheme 2, bottom).13 The choice of the latter is not arbitrary, as these ubiquitous motifs possess an electron-rich carbonyl fragment suitable for metal chelation without the need for decorating the amide backbone with strongly chelating quinoline or pyridine backbones, hence setting the basis for applying these techniques to advanced synthetic intermediates.14 As part of our interest in the field,15 we report herein the successful realization of this goal. The protocol is distinguished by its mild conditions, broad scope, and exquisite site-selectivity, thus offering new opportunities in chain-walking and an unrecognized opportunity to enable formation of unactivated sp3–sp3 bonds in deaminative cross-couplings at methylene sp3 C–H sites.16 The protocol is inherently modular, allowing to establish regiodivergent scenarios for incorporating sp3–sp3 architectures at different methylene sp3 C–H sites by judicious choice of the ligand backbone.

Scheme 2. Interrupted Ni-Catalyzed Chain-Walking Events.

We began our studies by evaluating the Ni-catalyzed interrupted deaminative chain-walking reaction of 1a with 2a, readily accessible in large amounts from the corresponding tert-butyl 4-aminopiperidine-1-carboxylate in a single step (Table 1). After judicious screening of the reaction parameters,17 we found that a combination of NiI2 (5 mol %), L1 (10 mol %), (EtO)3SiH, and Na2HPO4 in DMA at 40 °C afforded the best results, giving rise to 3a in 81% isolated yield with exquisite β-selectivity (>150:1). As anticipated, the nature of the ligand was critical for success, with pyrox ligands providing better results than 2,2′-bipyridine congeners (entry 1 vs entry 6). Low β-selectivity was obtained with L3 and L4 lacking substituents adjacent to the nitrogen atom at either the pyridine or oxazoline motif (entries 3 and 4), whereas a selectivity switch was observed when utilizing nonsubstituted analogues, thus showing the subtleties of our reaction.18 In addition, nickel sources, silanes, or solvents other than NiI2, (EtO)3SiH, or DMA led to lower yields of 3a (entries 7–9). Similarly, conducting the reaction at room temperature led to significantly lower reactivity (entry 10). As expected, control experiments indicated that all of the reaction parameters were critical for success (entry 11).

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditionsa.

Conditions: 1a (0.12 mmol), 2a (0.10 mmol), NiI2 (5 mol %), L1 (10 mol %), (EtO)3SiH (0.20 mmol), Na2HPO4 (0.20 mmol), DMA (0.10 M) at 40 °C for 15 h.

GC yields using dodecane as internal standard.

Isolated yield.

As shown in Table 2, our interrupted chain-walking sp3–sp3 bond formation turned out to be widely applicable regardless of the substitution pattern at the amide backbone. Indeed, excellent yields and exclusive β-selectivities were observed for a series of amides derived from acyclic amines (3a–3c), anilines (3d), piperidine (3e), piperazine (3f), morpholine (3g), and pyrrolidine (3h). Even secondary amides exhibiting acidic N–H bonds delivered 3j and 3l in good yields and exquisite β-selectivity. Notably, excellent regiocontrol was obtained with Weinreb amides with just 1 mol % NiI2 (3m), thus leaving ample room for further manipulation by using the amide backbone as a masked carbonyl fragment.17,19 These results contribute to the perception that our protocol does not operate under substrate control and that L1 dictates the β-selectivity pattern. Note, however, that azetidine 3i and primary amides (3k) led to slightly lower regioselectivities, probably due to a poor orbital overlap in the former and an ineffective coordination mode in the latter.20 Next, we turned our attention to study the influence of the olefin on both reactivity and selectivity. Importantly, our interrupted β-selective deaminative chain-walking event could be applied across a wide number of substrates with exclusive β-selectivity. It is worth noting that long-range chain-walking events are within reach with exclusive β-selectivity, albeit in slightly lower yields (3a vs 3n–q). More importantly was the observation that both E- and Z-internal olefins could participate equally well in our β-selective sp3–sp3 bond-forming reaction (3n–3y), even by utilizing advanced reaction intermediates (3z). Notably, 1,1-disubstituted olefins or even trisubstituted olefins could be employed as substrates with similar ease (3s, 3t). Equally interesting was the ability to extend this technique to cyclic amides, obtaining the targeted cis β-alkylated 3u and 3w. Interestingly, 3-cyclohexenamide only delivered γ-selective 3v—unambiguously characterized by X-ray diffraction—in 51% yield. At present, we tentatively ascribe these results with an enhanced chelation of the nickel catalyst to the amide backbone through syn-pentane interactions in the well-defined chair conformation of cyclohexane rings.17,21 Although one might argue that the presence of a pending, coordinating ester or an arene on the alkyl side chain might compromise site-selectivity,5a,6b this was not the case, and 3x and 3y were both obtained in good yields, thus highlighting the strong chelation exerted by the native amide backbone.13 The successful preparation of 3aa–3ak with pyridinium salts arising from aliphatic or cyclic secondary amines showcases the generality of our β-alkylation beyond 2a. While the utilization of pyridinium salts derived from benzyl amines led to the targeted products 3aj and 3ak, the coupling of the corresponding primary alkyl congeners was better suited with alkyl iodides, delivering 3al–3ar in good yields as exclusive β-isomers, even when utilizing capsaicin as substrate (3at vs 3z). As expected, 3u and 3as were both obtained with exquisite regioselectivity en route to the corresponding β- or γ-alkylated products, thus illustrating the intriguing site-selectivity observed depending on the size of the pre-existing ring.

Table 2. Scope of the Ni-Catalyzed Deaminative Interrupted Chain-Walking β-Alkylation of Native Amidesa.

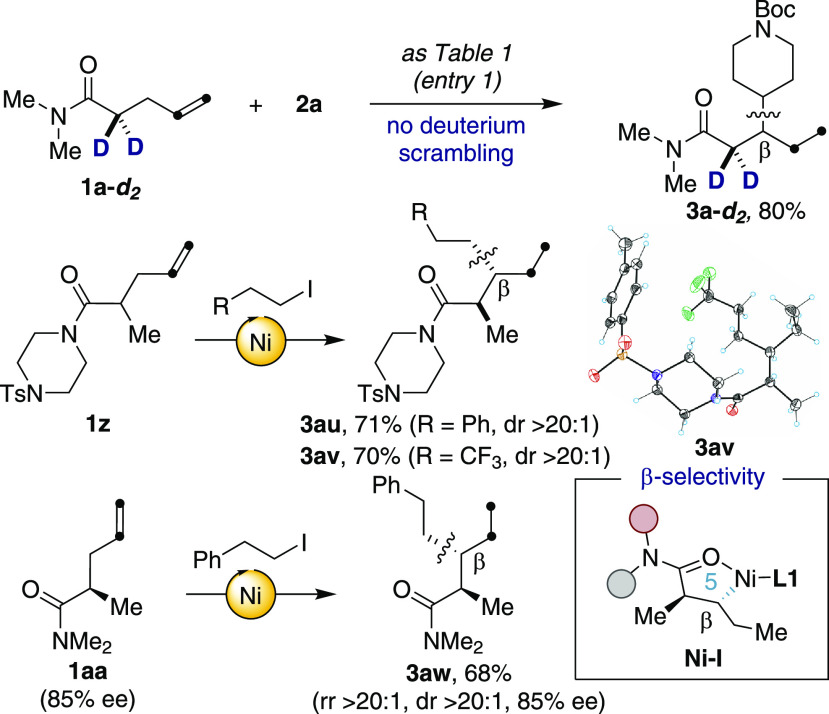

Taking into consideration the exclusive β-selectivity observed in Table 2, we wondered whether our interrupted chain-walking deamination proceeded via five-membered nickelacycles or acrylamides formed upon olefin isomerization prior to sp3–sp3 bond formation. To this end, the reaction of 1a and 2a was monitored by both 1H NMR spectroscopy and GC analysis.17 Under the limits of detection, not even traces of acrylamide were detected in the crude mixtures. In addition, no deuterium incorporation was observed at the β-position when utilizing 1a-d2 as substrate, thus arguing against acrylamides as reaction intermediates (Scheme 3). However, it was not particularly straightforward to rigorously distinguish whether sp3–sp3 bond formation occurred via reductive elimination of in situ generated nickelacycles or Giese-type addition of alkyl radical intermediates to α,β-unsaturated amides. High diastereoselectivity for the reaction of 1z was anticipated in the former; on the contrary, statistical mixtures of diastereoisomers in 3au–3av would indicate a radical-type pathway. As shown in Scheme 3, high yields and dr > 20:1 were obtained for both products, with an anti-stereochemistry unequivocally confirmed by X-ray diffraction of 3av. In line with this observation, the reaction of enantioenriched 1aa resulted in 3aw with an excellent selectivity profile and, more importantly, with preservation of the chiral integrity at the α-position. Taken together, these findings advocate the notion that the formation of Ni–I precedes sp3–sp3 bond formation.

Scheme 3. Preliminary Mechanistic Experiments.

Conditions for 1z and 1aa: amide (0.30 mmol), alkyl iodide (0.45 mmol), NiI2 (10 mol %), L1 (20 mol %), (EtO)3SiH (0.60 mmol), Na2HPO4 (0.60 mmol), DMA (0.10 M) at 50 °C for 15 h.

Encouraged by the results of Table 2, we wondered whether the nature of the ligand might dictate the site-selectivity of our interrupted Ni-catalyzed deaminative chain-walking event. As shown in Scheme 4, regiodivergency could be accomplished in the reaction of 1a and 2a by a judicious choice of the ligand. Specifically, a Ni/L1 regime delivered 3a with exclusive β-selectivity (>150:1) and high TON (68). Notably, the utilization of L7 or L8 gave rise to 4a and 5a with γ- and δ-selectivity, respectively.22 These results should be interpreted against the challenge that is addressed, offering a gateway to develop “a la carte” site-selective deaminative sp3–sp3 bond formations by controlling the motion at which Ni catalysts promote chain-walking reactions. Gratifyingly, our chain-walking scenario based on the Ni/L7 couple could be extended to internal olefins with either primary or secondary alkyl electrophiles (4b, 4c). In addition, the successful preparation of 4d from capsaicin stands as a testament to the impact that this technique might have in the context of late-stage diversification of advanced intermediates.

Scheme 4. Regiodivergent β/γ/δ sp3–sp3 Bond Formations.

Conditions for 4a–d: amide (0.36 mmol), pyridinium salt or alkyl iodide (0.30 mmol), NiBr2·diglyme (5 mol %), L7 (10 mol %), (EtO)3SiH (0.60 mmol), Na2HPO4 (0.72 mmol), DMA (0.10 M) at rt for 15 h.

In summary, we report the successful utilization of native amides for forging sp3–sp3 architectures via interrupted site-selective deaminative nickel chain-walking catalysis at methylene sp3 C–H sites. This method is characterized by its mild conditions, excellent site-selectivity, and wide scope, including challenging substrate combinations and advanced intermediates. A judicious choice of the ligand backbone allows the effective discrimination among different methylene sp3 C–H sites, offering an opportunity to promote regiodivergent strategies when forging sp3 architectures. Further studies into the mechanism and extension to related transformations are currently ongoing.

Acknowledgments

We thank ICIQ, FEDER/MCI PID2021-123801NB-I00, and European Research Council (ERC) under European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement 883756) for financial support. H.W. thanks the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for a predoctoral fellowship.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c12915.

Experimental procedures and spectral and crystallographic data (PDF)

Author Contributions

J.R. and H.W. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- For selected reviews on sp3 C–H functionalization, see:; a Huang Z.; Lim H. N.; Mo F.; Young M. C.; Dong G. Transition Metal-Catalyzed Ketone-Directed or Mediated C–H Functionalization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 7764–7786. 10.1039/C5CS00272A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Davies H. M. L.; Morton D. Recent Advances in C–H Functionalization. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 343–350. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gensch T.; Hopkinson M. N.; Glorius F.; Wencel-Delord J. Mild Metal-Catalyzed C–H Activation: Examples and Concepts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2900–2936. 10.1039/C6CS00075D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d He J.; Wasa M.; Chan K. S. L.; Shao Q.; Yu J.-Q. Palladium-Catalyzed Transformations of Alkyl C–H Bonds. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8754–8786. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Rej S.; Das A.; Chatani N. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 431, 213683. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Holmberg-Douglas N.; Nicewicz D. A. Photoredox-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1925–2016. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For C–H functionalization strategies in medicinal chemistry, see:; a Cernak T.; Dykstra K. D.; Tyagarajan S.; Vachal P.; Krska S. W. The Medicinal Chemist’s Toolbox for Late Stage Functionalization of Drug-like Molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 546–576. 10.1039/C5CS00628G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Moir M.; Danon J. J.; Reekie T. A.; Kassiou M. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2019, 14, 1137–1149. 10.1080/17460441.2019.1653850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Guillemard L.; Kaplaneris N.; Ackermann L.; Johansson M. J. Late-Stage C–H Functionalization Offers New Opportunities in Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 522–545. 10.1038/s41570-021-00300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Jana R.; Begam H. M.; Dinda E. The Emergence of the C–H Functionalization Strategy in Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10842–10866. 10.1039/D1CC04083A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lovering F.; Bikker J.; Humblet C. Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756. 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lovering F. Escape from Flatland 2: Complexity and Promiscuity. Med. Chem. Commun. 2013, 4, 515–519. 10.1039/c2md20347b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews on chain-walking reactions, see:; a Vasseur A.; Bruffaerts J.; Marek I. Remote Functionalization through Alkene Isomerization. Nat. Chem. 2016, 11, 209–219. 10.1038/nchem.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sommer H.; Juliá-Hernández F.; Martin R.; Marek I. Walking Metals for Remote Functionalization. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 153–165. 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Janssen-Müller D.; Sahoo B.; Sun S.-Z.; Martin R. Tackling Remote Sp3 C–H Functionalization via Ni-Catalyzed “Chain-Walking” Reactions. Isr. J. Chem. 2020, 60, 195–206. 10.1002/ijch.201900072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Li Y.; Wu D.; Cheng H.-G.; Yin G. Difunctionalization of Alkenes Involving Metal Migration. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7990–8003. 10.1002/anie.201913382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Ghosh S.; Patel S.; Chatterjee I. Chain-Walking Reactions of Transition Metals for Remote C–H Bond Functionalization of Olefinic Substrates. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 11110–11130. 10.1039/D1CC04370F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wang Y.; He Y.; Zhu S. NiH-Catalyzed Functionalization of Remote and Proximal Olefins: New Reactions and Innovative Strategies. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 3519–3536. 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected references:; a He Y.; Cai Y.; Zhu S. Mild and Regioselective Benzylic C–H Functionalization: Ni- Catalyzed Reductive Arylation of Remote and Proximal Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1061–1064. 10.1021/jacs.6b11962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xiao J.; He Y.; Ye F.; Zhu S. Remote sp3 C–H Amination of Alkenes with Nitroarenes. Chem. 2018, 4, 1645–1657. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c He J.; Song P.; Xu X.; Zhu S.; Wang Y. Migratory Reductive Acylation between Alkyl Halides or Alkenes and Alkyl Carboxylic Acids by Nickel Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 3253–3259. 10.1021/acscatal.9b00521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Zhang Y.; Han B.; Zhu S. Rapid Access to Highly Functionalized Alkyl Boronates by NiH-Highly Functionalized Alkyl Boronates by NiH-Catalyzed Remote Hydroarylation of Boron-Containing Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13860–13864. 10.1002/anie.201907185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kapat A.; Sperger T.; Guven S.; Schoenebeck F. E-Olefins through intramolecular radical relocation. Science 2019, 363, 391–396. 10.1126/science.aav1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Zhang Y.; He J.; Song P.; Wang Y.; Zhu S. Ligand-Enabled NiH-Catalyzed Migratory Hydroamination: Chain Walking as a Strategy for Regiodivergent/Regioconvergent Remote sp3 C–H Amination. CCS Chem. 2021, 2, 2259–2268. 10.31635/ccschem.020.202000490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Gao J. G.; Jiao M.; Ni J.; Yu R.; Cheng G.-J.; Fang X. Nickel-Catalyzed Migratory Hydrocyanation of Internal Alkenes: Unexpected Diastereomeric-Ligand-Controlled Regiodivergence. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 1883–1890. 10.1002/anie.202011231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Guven S.; Kundu G.; Wessels A.; Ward J. S.; Rissanen K.; Schoenebeck F. Selective Synthesis of Z-Silyl Enol Ethers via Ni-Catalyzed Remote Functionalization of Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 8375–8380. 10.1021/jacs.1c01797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Ding C.; Ren Y.; Sun C.; Long J.; Yin G. Regio- and Stereoselective Alkylboration of Endocyclic Olefins Enabled by Nickel Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20027–20034. 10.1021/jacs.1c09214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Zheng S.; Wang W.; Yuan W. Remote and Proximal Hydroaminoalkylation of Alkenes Enabled by Photoredox/Nickel Dual Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17776–17782. 10.1021/jacs.2c08039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected references:; a Buslov I.; Becouse J.; Mazza S.; Montandon-Clerc M.; Hu X. Chemoselective Alkene Hydrosilylation Catalyzed by Nickel Pincer Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14523–14526. 10.1002/anie.201507829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Juliá-Hernández F.; Moragas T.; Cornella J.; Martin R. Remote Carboxylation of Halogenated Aliphatic Hydrocarbons with Carbon Dioxide. Nature 2017, 545, 84–88. 10.1038/nature22316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhou F.; Zhu J.; Zhang Y.; Zhu S. NiH-Catalyzed Reductive Relay Hydroalkylation: A Strategy for the Remote C(sp3)–H Alkylation of Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4058–4062. 10.1002/anie.201712731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sun S.-Z.; Börjesson M.; Martin-Montero R.; Martin R. Site-Selective Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of α-Haloboranes with Unactivated Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12765–12769. 10.1021/jacs.8b09425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Sun S.-Z.; Romano C.; Martin R. Site-Selective Catalytic Deaminative Alkylation of Unactivated Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 16197–16201. 10.1021/jacs.9b07489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Tortajada A.; Menezes Correia J. T.; Serrano E.; Monleón A.; Tampieri A.; Day C. S.; Juliá-Hernández F.; Martin R. Ligand-Controlled Regiodivergent Catalytic Amidation of Unactivated Secondary Alkyl Bromides. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 10223–10227. 10.1021/acscatal.1c02913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Chen X.; Rao W.; Yang T.; Koh M. J. Alkyl Halides as Both Hydride and Alkyl Sources in Catalytic Regioselective Reductive Olefin Hydroalkylation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5857–5865. 10.1038/s41467-020-19717-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lee C.; Seo H.; Jeon J.; Hong S. γ-Selective C(sp3)–H Amination via Controlled Migratory Hydroamination. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5657–5665. 10.1038/s41467-021-25696-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang X.-X.; Xu Y.-T.; Zhang Z.-L.; Lu X.; Fu Y. NiH-Catalysed Proximal-Selective Hydroalkylation of Unactivated Alkenes and the Ligand Effects on Regioselectivity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1890–1899. 10.1038/s41467-022-29554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du B.; Ouyang Y.; Chen Q.; Yu W.-Y. Thioether-Directed NiH-Catalyzed Remote γ-C(sp3)–H Hydroamidation of Alkenes by 1,4,2-Dioxazol-5-Ones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14962–14968. 10.1021/jacs.1c05834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li W.; Boon J. K.; Zhao Y. Nickel-Catalyzed Difunctionalization of Allyl Moieties using Organoboronic Acids and Halides with Divergent Regioselectivities. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 600–607. 10.1039/C7SC03149A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Qian D.; Hu X. Ligand-Controlled Regiodivergent Hydroalkylation of Pyrrolines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18519–18523. 10.1002/anie.201912629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang J.-W.; Liu D.-G.; Chang Z.; Li Z.; Fu Y.; Lu X. Nickel-Catalyzed Switchable Site-Selective Alkene Hydroalkylation by Temperature Regulation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202205537 10.1002/anie.202205537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhao L.; Zhu Y.; Liu M.; Xie L.; Liang J.; Shi H.; Meng X.; Chen Z.; Han J.; Wang C. Ligand-Controlled NiH-Catalyzed Regiodivergent Chain-Walking Hydroalkylation of Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202204716 10.1002/anie.202204716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yang P.-F.; Shu W. Orthogonal Access to α-/β-Branched/Linear Aliphatic Amines by Catalyst-Tuned Regiodivergent Hydroalkylations. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202208018 10.1002/anie.202208018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basnet P.; Dhungana R. K.; Thapa S.; Shrestha B.; KC S.; Sears M. J.; Giri R. Ni-Catalyzed Regioselective β,δ-Diarylation of Unactivated Olefins in Ketimines via Ligand-Enabled Contraction of Transient Nickellacycles: Rapid Access to Remotely Diarylated Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7782–7786. 10.1021/jacs.8b03163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Roughley S. D.; Jordan A. M. The Medicinal Chemist’s Toolbox: An Analysis of Reactions Used in the Pursuit of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3451–3479. 10.1021/jm200187y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vitaku E.; Smith D. T.; Njardarson J. T. Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274. 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Blakemore D. C.; Castro L.; Churcher I.; Rees D. C.; Thomas A. W.; Wilson D. M.; Wood A. Organic Synthesis Provides Opportunities to Transform Drug Discovery. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 383–394. 10.1038/s41557-018-0021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews on deaminative cross-coupling reactions, see:; a Kong D.; Moon P. J.; Lundgren R. J. Radical Coupling from Alkyl Amines. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 473–476. 10.1038/s41929-019-0292-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Correia J. T. M.; Fernandes V. A.; Matsuo B. T.; Delgado J. A. C.; de Souza W. C.; Paixão M. W. Photoinduced Deaminative Strategies: Katritzky Salts as Alkyl Radical Precursors. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 503–514. 10.1039/C9CC08348K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rössler S. L.; Jelier B. J.; Magnier E.; Dagousset G.; Carreira E. M.; Togni A. Pyridinium Salts as Redox-Active Functional Group Transfer Reagents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9264–9280. 10.1002/anie.201911660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gao Y.; Jiang S.; Mao N.-D.; Xiang H.; Duan J.-L.; Ye X.-Y.; Wang L.-W.; Ye Y.; Xie T. Recent Progress in Fragmentation of Katritzky Salts Enabling Formation of C–C, C–B, and C–S Bonds. Top. Curr. Chem. 2022, 380, 25. 10.1007/s41061-022-00381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an excellent review on the utilization of weakly coordinating directing groups:Engle K. M.; Mei T.-S.; Wasa M.; Yu J.-Q. Weak Coordination as a Powerful Means for Developing Broadly Useful C–H Functionalization Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 788–802. 10.1021/ar200185g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For the utilization of native amides as weakly coordinating groups in sp3 C–H functionalizations catalyzed by Pd, W, or Rh catalysts, see:; a Park H.; Li Y.; Yu J.-Q. Utilizing Carbonyl Coordination of Native Amides for Palladium-Catalyzed C(sp3)–H Olefination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 11424–11428. 10.1002/anie.201906075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xue Y.; Park H. S.; Jiang C.; Yu J.-Q. Palladium-Catalyzed β-C(sp3)–H Nitrooxylation of Ketones and Amides Using Practical Oxidants. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 14188–14193. 10.1021/acscatal.1c04188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Jankins T. C.; Martin-Montero R.; Cooper P.; Martin R.; Engle K. M. Low-Valent Tungsten Catalysis Enables Site-Selective Isomerization–Hydroboration of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14981–14986. 10.1021/jacs.1c07162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wakikawa T.; Sekine D.; Murata Y.; Bunno Y.; Kojima M.; Nagashima Y.; Tanaka K.; Yoshino T.; Matsunaga S. Native Amide-Directed C(sp3)–H Amidation Enabled by Electron-Deficient RhIII Catalyst and Electron-Deficient 2-Pyridone Ligand. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202213659 10.1002/anie.202213659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gaydou M.; Moragas T.; Juliá-Hernández F.; Martin R. Site-Selective Catalytic Carboxylation of Unsaturated Hydrocarbons with CO2 and Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12161–12164. 10.1021/jacs.7b07637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sahoo B.; Bellotti P.; Juliá-Hernández F.; Meng Q. Y.; Crespi S.; König B.; Martin R. Site-Selective, Remote sp3 C-H Carboxylation Enabled by the Merger of Photoredox and Nickel Catalysis. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 9001–9005. 10.1002/chem.201902095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sun S. Z.; Talavera L.; Spiess P.; Day C.; Martin R. sp3 Bis-Organometallic Reagents via Catalysic 1,1-Difunctionalization of Unactivated Olefins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11740–11744. 10.1002/anie.202100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yue W. J.; Martin R. Ni-Catalyzed Site-Selective Hydrofluoroalkylation of Terminal and Internal Olefins. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 12132–12137. 10.1021/acscatal.2c04412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Refs (6b, 6d−6f), and (14c).

- For deaminative cross-couplings that forge sp3–sp3 linkages via functional group interconversion of well-defined alkyl halides or alkyl organometallic reagents at the initial sp3 C–X(M) site, see:; a Plunkett S.; Basch C. H.; Santana S. O.; Watson M. P. Harnessing Alkylpyridinium Salts as Electrophiles in Deaminative Alkyl–Alkyl Cross-Couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2257–2262. 10.1021/jacs.9b00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ni S.; Li C.; Han J.; Mao Y.; Pan Y. Ni-catalyzed deamination cross-electrophile coupling of Katritzky salts with halides via C-N bond activation. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, 9516. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw9516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ref (6e).; d Bercher O. P.; Plunkett S.; Mortimer T. E.; Watson M. P. Deaminative Reductive Methylation of Alkylpyridinium Salts. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 7059–7063. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yang T.; Wei Y.; Koh M. J. Photoinduced Nickel-Catalyzed Deaminative Cross-Electrophile Coupling for C(sp2)–C(sp3) and C(sp3)–C(sp3) Bond Formation. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6519–6525. 10.1021/acscatal.1c01416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For details, see the Supporting Information.

- While L2 possessed a chiral center, no asymmetric induction was observed in 3a.

- Nahm S.; Weinreb S. M. N-Methoxy-N-Methylamides as Effective Acylating Agents. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 3815–3818. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)91316-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For a study of different carbonyl fragments in this interrupted nickel-catalyzed chain-walking reaction, see ref (17).

- Hoffmann R. W.; Stahl M.; Schopfer U.; Frenking G. Conformation Design of Hydrocarbon Backbones: A Modular Approach. Chem. – Eur. J. 1998, 4, 559–566. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- We hypothesize that the less sterically encumbered ligand L7 provides more degrees of freedom and ample room for amide chelation, hence stabilizing nickelacycle Ni-III en route to γ-alkylation. The reactivity of a Ni/L8 might be interpreted on the basis of a classical anti-Markovnikov hydrometalation of a nickel hydride across the terminal olefin prior to sp3–sp3 bond formation.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.