Abstract

Cancer tissues generally have molecular oxygen and serum component deficiencies because of poor vascularization. Recently, we revealed that ICAM1 is strongly activated through lipophagy in ovarian clear cell carcinoma (CCC) cells in response to starvation of long‐chain fatty acids and oxygen and confers resistance to apoptosis caused by these harsh conditions. CD69 is a glycoprotein that is synthesized in immune cells and is associated with their activation through cellular signaling pathways. However, the expression and function of CD69 in nonhematological cells is unclear. Here, we report that CD69 is induced in CCC cells as in ICAM1. Mass spectrometry analysis of phosphorylated peptides followed by pathway analysis revealed that CD69 augments CCC cell binding to fibronectin (FN) in association with the phosphorylation of multiple cellular signaling molecules including the focal adhesion pathway. Furthermore, CD69 synthesized in CCC cells could facilitate cell survival because the CD69–FN axis can induce epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Experiments with surgically removed tumor samples revealed that CD69 is predominantly expressed in CCC tumor cells compared with other histological subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer. Overall, our data suggest that cancer cell‐derived CD69 can contribute to CCC progression through FN.

Keywords: CD69, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, hypoxia, lipid metabolism, tumor microenvironment

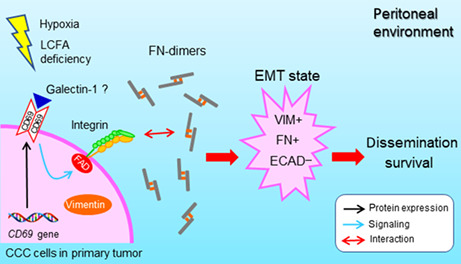

We provided a novel concept that CD69 is strongly expressed in epithelial, nonhematological ovarian clear cell carcinoma (CCC) cells. CD69 protein induced in response to fatty acid and oxygen starvation is responsible for fibronectin‐driven epithelial–mesenchymal transition, potentially contributing to the poor prognosis of CCC patients.

Abbreviations

- ARNT

arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator

- CCC

cell surface E‐cadherin

- ECAD

E‐cadherin

- >EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- EOC

epithelial ovarian cancer

- FAD

focal adhesion

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FN

fibronectin

- HIF

hypoxia‐inducible factor

- HP‐Alb

high‐purity albumin

- ICAM‐1

intercellular adhesion molecule‐1

- LCFA

long‐chain fatty acid

- MS

mass spectrometry

- >MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- NF‐κB

nuclear factor‐κB

- NS

nonspecific

- NT

nontumorous

- SSH

serum starvation and hypoxia

- SSN

serum starvation and normoxia

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TGF‐β1

transforming growth factor‐β1

- TMA

tissue microarray

- VIM

vimentin

1. INTRODUCTION

Many solid tumor regions are exposed to low oxygen (O2) tension because of poor vascular density and aberrant vascular structure compared with normal tissues. 1 The induction of hypoxia‐inducible transcription factors followed by the activation of their target genes is a critical mechanism for the response and adaptation to severe O2 deficiency. 2 In addition to limited O2 supply, blood components such as hormones, growth factors, and nutrients become less available to cancer cells under these hypoxic conditions. Thus, cancer cells must adapt to both O2 and plasma factor insufficiencies for tumor progression.

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecological malignancy worldwide. 3 , 4 Epithelial ovarian cancer is classified into multiple histological subtypes. 4 Clear cell carcinoma is common in some Asian and European countries, including Japan, and has a poor survival rate compared with other histological subtypes. 5 The biology of EOC including CCC has been revealed but is not fully understood. 5

Recent studies reported that an insufficient plasma lipid supply in the cooperation of hypoxia is lethal and that multiple cellular adaptation mechanisms have roles in cancer progression. 6 , 7 , 8 We have also shown that ICAM1, which encodes ICAM‐1 protein, is strongly activated by Sp1–HIF‐2α interactions in CCC cells that are exposed to SSH. 9 , 10 We revealed that LCFAs and O2 deficiencies followed by lipophagy‐driven degradation of lipid droplets causes stabilization of NF‐κB binding to induce synergistic ICAM1 expression. 10 ICAM‐1 contributes to cell survival under SSH and tumor growth. 9

We showed that multiple genes such as KLF6, 9 JUN, 9 and FVII 11 are also synergistically activated in CCC cells with O2 depletion in response to LCFA (KLF6 and JUN) 9 and cholesterol (FVII) 11 insufficiency. Our cDNA microarray analysis further identified CD69 as one such gene. CD69 is a type II C‐lectin that is synthesized in limited immune cells and plays roles in the immune response as a homodimer. 12 , 13 , 14 However, there have been no reports of the expression of CD69 in nonhematological cells, including leukemia cells. Thus, in this study, we aimed to determine the role of CCC cell‐derived CD69 to better comprehend the biology of ovarian cancer.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cells and culture conditions

See Data S1.

2.2. Small interfering RNA transfection

Experiments were carried out as previously described. 9 , 10 , 11

2.3. Reagents

See Data S1.

2.4. cDNA microarray analysis

We analyzed cDNA microarray data obtained in our previous studies. 9

2.5. Establishment of cell lines stably introduced with shRNAs

For silencing of CD69 mRNA expression, we used the SureSilencing shRNA plasmid kit (Qiagen Sciences) designed to specifically knock down human CD69 gene expression. Transfection of CD69 shRNA expression vectors and its negative control shRNA vector was undertaken using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life Technologies). Independent cell lines stably expressing shRNAs were selected using G418 as a selection reagent.

2.6. Real‐time RT‐PCR

CD69 and 18S ribosomal RNA transcript levels were determined as previously described. 9 See Data S1 for primers and probes used.

2.7. Western blot analysis

Western blotting was carried out as previously described. 9 See Data S1 for primary Abs used. Other Abs were previously described. 10

2.8. Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Experiments were carried out as previously described. 9 , 10 , 11

2.9. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated by MTS assay using the CellTiter96 kit (Promega) and Countess automated cell counter (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.10. Transwell assays

The motility of cancer cells was analyzed by Transwell assay using 24‐well Boyden chambers. 15 Briefly, for migration assays, cells suspended in serum‐free medium were added to the upper chamber. The lower chamber was filled with 600 μL serum‐free medium containing FN (10 μg/mL). After 48 h of incubation, cells on the lower side of the membrane were fixed and stained with Giemsa. The numbers of cells on a single membrane were counted in eight randomly chosen fields using a light microscope (×10).

2.11. Fibronectin coating of culture dish and cell adhesion assay

Culture plates were covered with human FN (10 μg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Plates were then washed twice with PBS. The culture plate was then treated with 100 μL 1 mg/mL BSA/PBS at 37°C for 1 h and then washed with PBS. Cultured cells were dissociated using Accutase (12679‐54; Nacalai Tesque). Cells treated with Ab or control IgG were seeded into the FN‐coated wells and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Cells that had adhered to the bottom of the well were counted by MTS assays. Anti‐β1‐integrin Ab (P5D2, ab24963) was purchased from Abcam.

2.12. Proteomic identification of phosphorylated proteins

Phosphorylation of proteins at serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues in OVSAYO cells was determined by proteomic analysis. 16 , 17 Briefly, OVSAYO cell lines transfected with nonspecific or CD69‐targeted shRNA were cultured under SSH conditions for 48 h. Cells were lysed and protein extracts were prepared. Peptides were purified and subjected to shotgun LC‐MS/MS analysis. Data were quantified by label‐free protein relative quantitation analysis using Progenesis LC‐MS software (Nonlinear Dynamics).

2.13. Flow cytometry

Cells (106) were dissociated using Accutase and washed once with PBS. For detection of cell surface ECAD, cells were suspended in PBS with 3% BSA and incubated with anti‐ECAD Ab (20874‐1‐AP; Proteintech) (2 μg/mL) and control IgG (I8104; Sigma) (2 μg/mL) for 2 h. Cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with Alexa488‐conjugated secondary Ab (A‐11008; Molecular Probes) for 1 h. Cells were washed once with PBS, and then resuspended in 1 mL PBS for flow cytometry using the BD FACSAria II (BD Bioscience). For CD69, experiments were carried out with slight modifications using anti‐CD69 Ab (ab51862; Abcam). For β1‐integrin (CD29), phycoerythrin‐conjugated Ab (#555443; BD Pharmingen) and control IgG (#555749; BD Pharmingen) were used.

2.14. Immunofluorescence

For immunocytochemistry of ECAD and VIM, cells (5 × 104) were seeded into 4‐well chamber polystyrene vessels (#354114; Corning) and then cultured under the indicated conditions. Following experiments were carried out as previously described. 10

2.15. Immunohistochemistry

Routinely processed formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded specimens were prepared from 130 EOC patients for a TMA (Table S1) and for 77 whole‐slide sections of CCC (Table S2) at Kanagawa Cancer Center Hospital. 10 Immunohistochemistry was undertaken 9 using anti‐CD69 (#373798; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti‐FN (A0245; Dako) Abs. Immunoreactivity was visualized as previously described. 10

2.16. Scoring of IHC and survival analysis

Acquisition of IHC images and scoring of CD69 and FN expression was carried out as previously described. 10 Alternatively, evaluation of CD69 staining scoring in whole‐slide sections was carried out using the H‐score method. 18 Kaplan–Meier analysis and multivariable analysis with the Cox regression method was undertaken as previously described. 10

2.17. Animal experiments

OVISE (5 × 106) cells expressing NS‐shRNA or CD69‐shRNA were injected into the peritoneal cavity of female NOD‐SCID mice (n = 6, per group) (Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc.). After 2 months, the mice were killed. Blood was collected into a one‐tenth volume of 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer directly from the heart under general anesthesia with isoflurane. Plasma was prepared from the blood supernatant after centrifugation (3000 g for 10 min.). Orthotopic inoculation of cancer cells (3 × 104 cells/injection) into mouse ovaries was carried out as previously published 19 with slight modifications.

2.18. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay for albumin

Albumin levels in mice plasma were determined using the mouse albumin ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratory Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.19. Statistical analysis

Two datasets were compared using t‐tests and the Mann–Whitney U‐test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis of the comprehensive phosphopeptide analysis was undertaken as previously described. 16 , 17

3. RESULTS

3.1. Synergistic CD69 expression in CCC cells in response to simultaneous deprivation of O2 and LCFAs

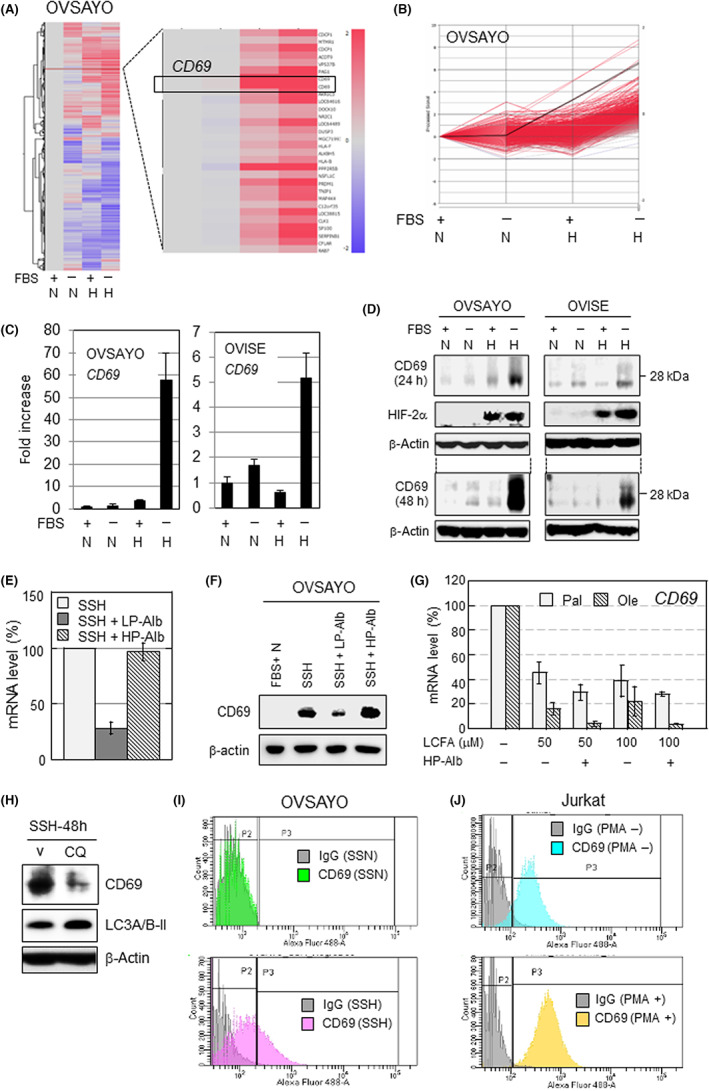

We examined our reported cDNA microarray data 9 and found that CD69 was robustly expressed in the OVSAYO cells upon exposure to SSH (Figure 1A,B). Real‐time RT‐PCR analysis revealed that CD69 mRNA levels in OVSAYO and OVISE cells exposed to SSH were synergistically increased compared with cells cultured under other conditions (Figure 1C). Western blot analysis revealed induction of CD69 in response to SSH at 24 and 48 h in CCC cells, along with similar induction of a hypoxia marker HIF‐2α (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1.

CD69 is synergistically activated in ovarian clear cell carcinoma cells cultured under serum starvation and hypoxia (SSH). (A) Heatmap representation of the cDNA microarray analysis. N and H indicate normoxia and hypoxia (1%O2) for 16 h, respectively. (B) Line graph representation of the transcript levels in (A). Black line, CD69 expression; red line, gene synergistically activated (688 total measurements) when cells were exposed to SSH (FBS‐H). (C) Real‐time RT‐PCR analysis. N and H indicate normoxia and hypoxia (1%O2) for 24 h, respectively. Data are the mean of independent replicates (n = 3) ± SD. (D) Western blot analysis of CD69 expression. (E) CD69 mRNA levels in OVSAYO cells cultured under SSH for 16 h. Data are the mean (n = 2) ± SD. (F) Western blotting of cells cultured as indicated. (G) Expression levels in OVSAYO cells. Data shown are the mean (n = 2) ± SD. (H) Effect of chloroquine (CQ) on CD69 expression in OVSAYO cells under SSH for 48 h. Increased LC3A/B‐II level is a marker of lipophagy inhibition. 10 (I) Histograms of flow cytometry (FCM) analysis of cell surface CD69 in OVSAYO cells cultured under the indicated conditions for 39 h. (J) Histograms of FCM analysis of CD69 expressed in Jurkat cells cultured with and without PMA (10 ng/mL) for 18 h. HIF‐2α, hypoxia‐inducible factor‐2α; HP‐Alb, high‐purity albumin; LCFA, long‐chain fatty acid; LP‐Alb, low‐purity albumin; Ole, oleic acid; Pal, palmitic acid; SSN, serum starvation and normoxia; V, vehicle

We further analyzed CD69 expression in four additional CCC cell lines (Figure S1). Two of the four lines examined showed constitutive (OVMANA) or constitutive but slightly hypoxia‐driven (JHOC‐7) induction of CD69. We decided to primarily use OVSAYO and OVISE cell lines in further investigations because we focused on SSH‐driven CD69 expression in this study.

We previously found that LCFA insufficiency causes robust expression of ICAM1 in CCC cells under hypoxia. 9 Therefore, we next examined whether the same trend can be seen in CD69 expression. Real‐time RT‐PCR showed that the SSH‐driven CD69 expression in OVSAYO cells was canceled by the addition of low‐purity albumin, which includes LCFAs (Figure 1E). In contrast, HP‐Alb failed to cancel it. The same trend was observed in protein expression (Figure 1F). We next tested whether LCFAs can suppress the induction of CD69 expression, as in ICAM1. 9 OVSAYO cells were cultured under SSH for 16 h in the presence or absence of LCFAs. The RT‐PCR analysis revealed that CD69 expression was repressed, and that the suppression was highest with coculture with HP‐Alb (Figure 1G), as in the case of ICAM1. 9 This downregulation was higher in the presence of the unsaturated LCFA oleic acid compared with the saturated palmitic acid, presumably because oleic acid is a primary source of lipid droplets. 8 Furthermore, we found that SSH‐driven CD69 expression was canceled by chloroquine treatment (lipophagy inhibition), as in the case of ICAM1 expression 10 (Figure 1H).

We tested whether transcription factors involved in SSH‐driven ICAM1 expression are also responsible for CD69 expression. Unlike ICAM1, 9 , 10 CD69 expression was primarily dependent on HIF‐1α (Figure S2A). This synergistic gene expression was also dependent on NF‐κB and Sp1, but not on ARNT, as in the case of the ICAM1 gene 9 (Figure S2A,B). Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay showed that HIF‐1α and Sp1, but not HIF‐2α, bind to the same GC‐rich site within the CD69 promoter region 20 (Figure S2C,D). Control experiments showed that both HIF‐1α and ARNT bind to the vascular endothelial growth factor gene hypoxia response element, although HIF‐2α binding was very low (Figure S2D). As expected, we found that NF‐κB (RelA subunit) binds to known consensus motifs 20 (Figure S2C,D). Flow cytometry revealed that CD69 was not detected in OVSAYO cells cultured under SSN (Figure 1I). As expected, we found that CD69 is increased on the surface of OVSAYO cells in response to SSH (Figure 1I), as in the case of positive control experiments with PMA‐treated human T cell leukemia (Jurkat) cells (Figure 1J). Thus, these data indicate that expression of CD69 can be strongly induced and expressed on the cell surface in CCC cells in response to SSH‐driven lipophagy.

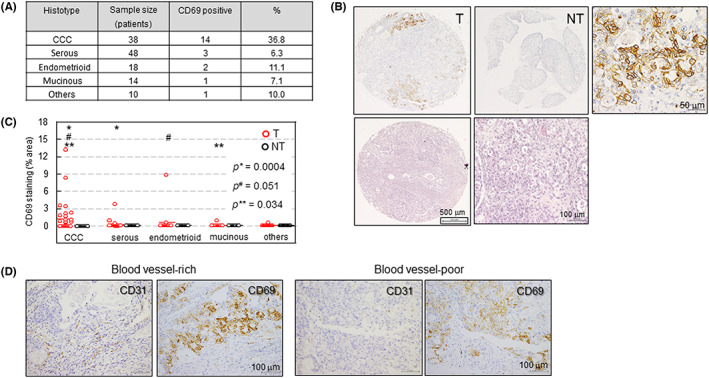

3.2. CD69 is predominantly expressed in CCC tissue

We next examined whether CD69 is expressed in EOC tissues (Table S1). Immunohistochemistry was undertaken using a TMA composed of 130 surgically removed EOC tissues (Figure 2A) and their NT counterparts including ovarian tubal tissue. We identified positive CD69 expression in approximately 36.8% (14/38) tumor (not immune) cells of CCC tissues, although other histological subtypes showed low expression (Figure 2A,B). No CD69 expression was observed in NT samples (Figure 2B). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissues with a typical CCC appearance is shown in Figure 2B. Quantitative analysis revealed that the proportion of CD69‐positive areas was significantly higher in tumor cells of CCC tissues compared with that in other histological subtypes (Figure 2C). We found that CD69 expression was predominant within blood vessel‐poor hypoxic areas (Figure 2D) because 29 out of 35 (83%) CD69‐positive CCC specimens showed this expression pattern (see Figure S3 for additional cases). However, CD69 expression within blood vessel‐rich areas was also possible (17%) (Figures 2D and S3), consistent with its constitutive expression in some cell lines (Figure S1). We excluded CD69 staining of potential tumor‐infiltrated cells sporadically existing in tumor tissues (Figure S4), which were CD3+ T lymphocytes 21 , 22 (Figure S4).

FIGURE 2.

Expression of CD69 in surgically removed epithelial ovarian cancer tissues. (A) CD69‐positive expression in 128 surgically removed samples. Immunohistochemistry for CD69 was carried out. (B) Representative CD69 staining of an ovarian clear cell carcinoma (CCC) sample (upper). T and NT indicate tumor and non‐tumor, respectively. The right panel shows an enlarged portion of the T section. H&E staining of CCC tissue (lower, left) and its magnified version (right). (C) Quantitative analysis of CD69 expression. CD69‐positive areas were quantified using ImageJ software. Percentage of CD69‐positive versus total tissue area was plotted. P values of datasets designated with the same symbol were calculated (Mann–Whitney U‐test). (D) Relationship between CD69 expression in tumor cells and tissue vessel density. CD31 is a blood vessel marker

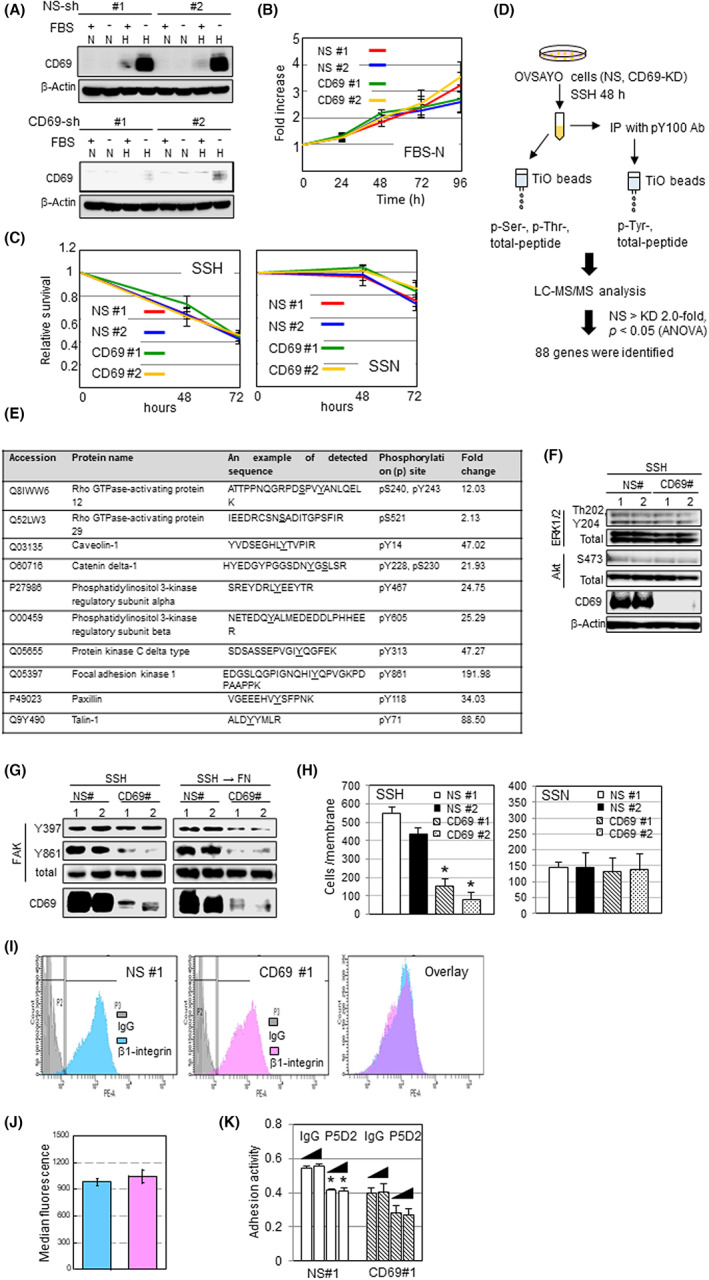

3.3. CD69 does not contribute to the viability of CCC cells under SSH conditions

To understand the role of CD69, we prepared OVSAYO and OVISE cell lines that stably express either NS‐ or CD69‐shRNAs. Western blotting showed that CD69 was robustly induced only in NS‐shRNA cells in response to SSH (Figures 3A and S5A). We found that CD69‐shRNA cells proliferated similarly under normoxia with FBS compared with the control NS‐shRNA cells (Figures 3B and S5B). Time course MTS assays revealed that the viability of CCC cells under SSH was not affected by CD69 knockdown at least within the tested time period (Figures 3C and S5C). The same results were obtained in experiments under SSN (Figures 3C and S5C), in which CD69 was not induced. Thus, CD69 does not affect cell proliferation under SSH.

FIGURE 3.

CD69 activates cellular signaling pathways but does not influence OVSAYO cell proliferation in vitro. (A) Western blot analysis of CD69 expression in shRNA transfected OVSAYO cells cultured for 48 h. (B) MTS proliferation assays. Data shown are the mean (n = 3) ± SEM. (C) MTS assays of cells cultured under indicated conditions. Data shown are the mean (n = 3) ± SEM. (D) Scheme of mass spectrometry analysis. (E) Ten examples of proteins with enhanced phosphorylation levels. Modified amino acid residues are underlined. (F) Phosphorylation of indicated proteins in cells cultured for 48 h. (G) Phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) in cells cultured for 48 h. (H) Fibronectin (FN)‐driven motility of OVSAYO cells cultured for 48 h. Data shown are the mean (n = 4) ± SE. *p < 0.05 compared with nonspecific (NS)#1 and NS#2. (I) Histograms of flow cytometry analysis of cell surface β1‐integrin in cells cultured for 48 h. (J) Quantitative comparison of results shown in I. Data are the mean (n = 3) ± SD. (K) Adhesiveness of cells cultured under serum starvation and hypoxia (SSH) in FN‐coated plates was examined in the presence of 5 μg/mL and 10 μg/mL IgG or P5D2 Ab. Data shown are the mean (n = 4) ± SE. *p < 0.05 vs. NS#1. H, hypoxia; IP, immunoprecipitation; KD, knockdown; LC‐MS/MS, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; N, normoxia; SSN, serum starvation and normoxia

3.4. CD69 affects intracellular signaling in OVSAYO cells

CD69 is involved in the activation of signaling proteins in human immune cells, such as ERK, 22 , 23 AKT, 21 JAK3, 24 and STAT5. 24 However, whether CD69 can cause cellular signaling in CCC cells is unclear. Thus, we next undertook a proteomic analysis to identify phosphorylated proteins in response to CD69 induction using OVSAYO cells. Nonspecific‐ and CD69‐shRNA cells were cultured under SSH for 48 h. The phosphorylation levels of peptides extracted from cells at serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues were comprehensively analyzed. Shotgun LC‐MS/MS analysis 16 , 17 revealed that 88 proteins were phosphorylated in response to CD69 expression (Figure 3D). We found that proteins, including FAK, talin, and catenin δ1, were phosphorylated at multiple residues in NS‐shRNA cells compared with CD69‐silenced cells (Figure 3D,E [see Table S3 for details]). We did not find increased phosphorylation of signaling proteins such as ERK, AKT, JAK3, or STAT5. Furthermore, we confirmed by western blotting that ERK and AKT phosphorylation in control cells was not changed in CD69‐silenced cells (Figure 3F). Pathway analysis of the identified proteins with altered phosphorylation using the Kyoto Encyclopedia Genes and Genomes and DAVID bioinformatic database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) revealed that multiple cellular signaling pathways are potentially activated in OVSAYO cells in association with CD69 expression (Table S4). We focused on the FAD pathway because this pathway ranks highest (13 genes/total 88 genes) (Table S4).

Focal adhesion kinase is a component of FAD and associates with integrins on the cell surface.25,26 Integrin activation, followed by phosphorylation of FAK at multiple tyrosine sites, 25 , 26 can enhance the motility and invasiveness of cancer cells through FN, 27 , 28 a component of the ECM. Thus, we undertook western blot analysis to determine whether FAK is phosphorylated in response to SSH‐mediated CD69 induction in OVSAYO cells. Activation of FAK in response to cell surface ligand–integrin interaction is initiated by autophosphorylation of Tyr397, which allows FAK to be further phosphorylated at Tyr576 and Tyr861 sites, resulting in full kinase activity. 27 , 28 Western blot analysis showed that the phosphorylation at Tyr861 in control OVSAYO cells cultured under SSH was diminished by CD69 knockdown (Figure 3G, left panels), consistent with LC‐MS/MS data. However, phosphorylation at Tyr397 was not affected by CD69 knockdown. In contrast, the phosphorylation at both Tyr397 and Tyr861 residues in response to ligand (FN) treatment of OVSAYO cells cultured under the same conditions 27 was blocked in CD69‐silenced cells (Figure 3G, right panels labeled with SSH → FN), suggesting that CD69 is required for the observed FN‐dependent FAK (Tyr397) phosphorylation under SSH.

We further examined CD69‐dependent phosphorylation of proteins that associate with the formation of FAD 29 , 30 , 31 by western blotting. We found that phosphorylation of talin and catenin δ1 was dependent on CD69 in OVSAYO cells (Figure S6), consistent with the results of LC‐MS/MS. Notably, the S425 residue of talin was phosphorylated in response to CD69 expression, although this phosphorylation was not detected by mass spectroscopy (Figure 3E). Collectively, data revealed a solid linkage between self‐production of CD69 and phosphorylation of signaling molecules associated with FAD formation in CCC cells.

3.5. CD69 enhances CCC cell binding to FN under SSH

Fibronectin is abundant in the peritoneal environment. Indeed, cancer‐associated mesothelial and stromal tissues can secrete FN. 32 , 33 Thus, using Transwell assays, we examined whether CCC cell migration to FN occurs in a CD69‐dependent manner. OVSAYO cells stably expressing NS‐shRNA exposed to SSH showed considerable migration to FN (Figure 3H). However, this motility was significantly diminished in cells without CD69 expression (Figure 3H). Motility was unaffected in both NS‐ and CD69‐shRNA cells under SSN (Figure 3H), in which CD69 was not induced.

β1‐integrin functions as a heterodimeric complex with various integrin α‐subunits such as α5‐integrin and is a primary ligand for FN, collagens, and laminin. 25 , 34 We next examined whether CCC cell–FN binding can be influenced by cell surface β1‐integrin. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the cell surface expression of β1‐integrin was independent of CD69 expression and did not differ between control and CD69‐silenced cells cultured under SSH (Figure 3I,J). Cell adhesion assays showed that adhesiveness was higher for control OVSAYO cells compared with CD69‐silenced cells (Figure 3K). This was true for OVISE cells (Figure S5D). The increased adhesion activity was fully diminished by anti‐integrin Ab treatment to the level of CD69‐silenced cells treated with negative control IgG (Figure 3K). Thus, CD69‐dependent adhesiveness to FN is likely mediated through β1‐integrin rather than through direct CD69–FN interactions. CD69‐independent adhesion ability was also diminished by this Ab treatment because the basal adhesion activity of cells also depends on β1‐integrin (Figure 3K).

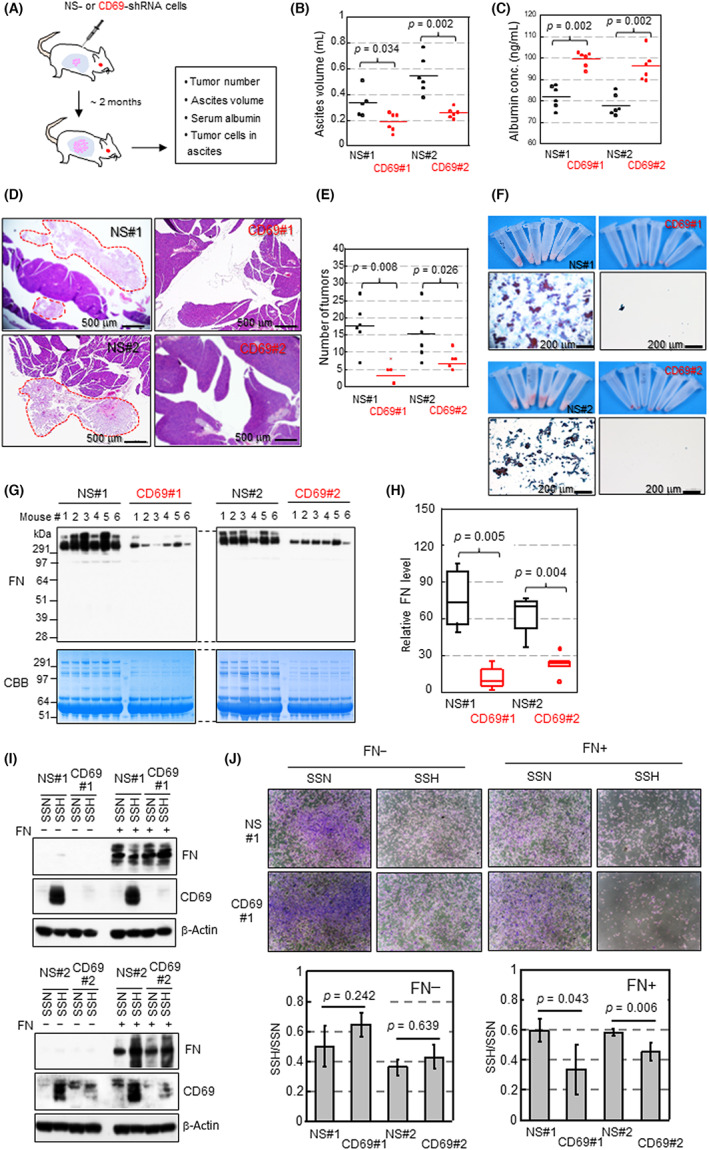

3.6. CD69 expression is crucial for survival of OVISE cells in the peritoneal cavity

To determine whether self‐production of CD69 could function in the survival of CCC cells in vivo, we undertook xenograft tumor experiments. We used OVISE cells for this purpose because of the favorable tumorigenicity of this cell type in immune‐deficient mice. Cells stably expressing shRNA were injected into the peritoneal cavity of female NOD‐SCID mice to establish a model of clinical peritoneal dissemination of EOC (Figure 4A). Animal weight, ascites generation, plasma albumin level (a cachexia marker), 35 and viability of cancer cells was assessed approximately 2 months after cancer cell inoculation. The volume of ascites prepared from control mice was larger than that of CD69sh mice (Figure 4B). The ELISA assays revealed that plasma albumin levels in control mice were significantly lower than those in CD69sh mice (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

CD69 facilitates xenograft OVISE tumor progression. (A) Schematic representation of animal experiments using six mice per group. Pink, cancer cells; light blue, peritoneal cavity. (B) Comparison of ascites. (C) Serum albumin levels (1:250,000 dilution) assessed by ELISA. (D) H&E staining of pancreas in mice. Cancer cells are surrounded with red dotted red lines. (E) Number of tumors associated with pancreas and spleen counted by microscopic examination of H&E‐stained tissues. (F) Appearance of cell pellets and cytopathological analysis of ascites samples. (G) Western blot analysis of fibronectin (FN) in ascites supernatants. Samples (20 μg protein) were loaded per lane. (H) Densitometrical quantitation of protein levels in (G). Statistical values in B, C, E, and H were calculated by the Mann–Whitney U‐test. (I) Western blot analysis of cells cultured for 48 h. (J) Cell viability assay. Cells were stained with crystal violet and quantified by ImageJ software. Data are the mean (n = 4) ± SD. Statistical values were calculated by t‐test. CBB, Coomassie brilliant blue; NS, nonspecific; SSH, serum starvation and hypoxia; SSN, serum starvation and normoxia

Microscopic analyses revealed that tumor nodules were primarily found in the retroperitoneal space around the pancreas (Figure 4D), spleen, and adipose tissues (data not shown) of control mice. The number of tumor nodules was higher for the control tumor than for the CD69‐silenced tumor (Figure 4E). Ascites prepared from control mice but not from CD69sh mice contained a number of cancer cells, as revealed by the amount of cell pellets (Figure 4F) and cytopathological analyses (Figure 4F). Western blot analysis showed that FN levels in the supernatants of ascites in control mice were significantly higher than those prepared from CD69sh mice (Figure 4G,H).

3.7. Fibronectin confers a survival advantage to SSH‐cultured cells in a CD69‐dependent manner

We further tested the effect of CD69 expression on the proliferation of tumor cells orthotopically injected into ovarian bursa. As in cases of intraperitoneal xenograft, tumorigenicity was higher for control cells than CD69‐silenced cells (Figure S7A), although tumor formation was impaired (Figure S7B) because the number of cells inoculated was limited 36 compared with the peritoneal tumor model. Immunohistochemistry showed that, unlike CD69 and HIF‐1α, orthotopic tumors were FN‐positive throughout the tumor region (Figure S7C,D).

We next tested whether the viability of OVISE cells under SSH could be enhanced by FN treatment. OVISE cells were seeded onto FN‐coated and noncoated dishes, and then the viability of cells cultured under SSN and SSH for 72 h was compared. Western blotting using whole‐cell lysate showed that CD69 was similarly expressed in response to SSH in the presence and absence of FN (Figure 4I). We found that cell viability was higher for control cells than CD69‐silenced cells cultured on FN‐coated dishes, although no difference was detected for cells cultured without FN (Figure 4J). Thus, FN likely confers a survival advantage to cells in a CD69‐dependent manner.

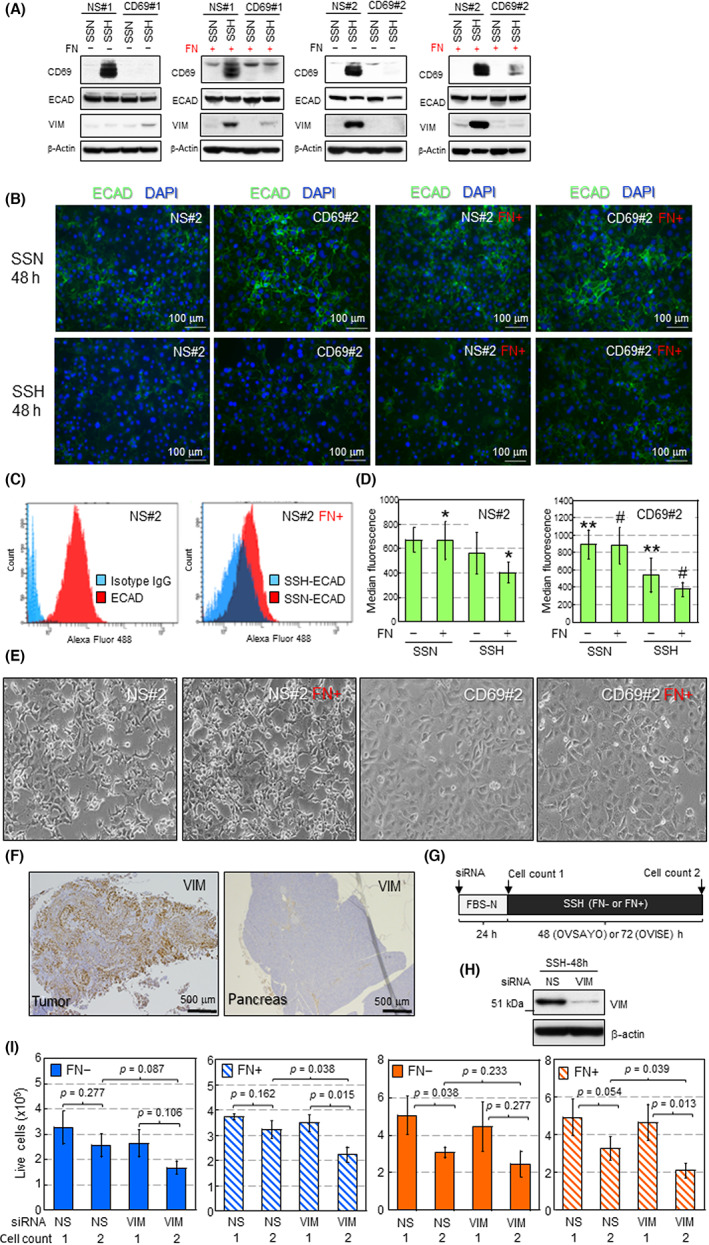

3.8. CD69 causes EMT in an FN‐dependent manner

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition is a critical malignant phenotype with reduced cell–cell tight junctions 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 and is often associated with tumor cell‐derived FN. 37 Although the examined CCC cells did not produce FN by themselves (Figure 4I), tumor cells were exposed to an FN‐rich environment in vivo (Figures 4G,H and S7D). Furthermore, our phosphopeptide analysis showed that tight junction proteins occludin 40 and ZO‐2 40 were modified in response to CD69 expression (Table S3). Thus, we next interrogated the possibility of whether the CD69‐external FN axis causes EMT in CCC cells. Western blotting showed that SSH‐cultured control (NS#1) cells expressed VIM, a critical mesenchymal marker, in FN‐coated dishes (Figure 5A). Vimentin was also induced in NS#2 cells. However, this was independent of FN‐coating (Figure 5A), suggesting clonal diversity regarding VIM expression because parental OVISE cells can express VIM without FN treatment (data not shown). Vimentin was not induced in either CD69‐silenced cells (Figure 5A). E‐cadherin, a critical marker of the epithelial phenotype in EMT, was reduced with VIM induction. 36 , 37 , 38 CD69‐dependent reduction of ECAD expression was not necessarily evident by western blotting (Figure 5A). The ECAD reduction was clearer in both control and CD69‐silenced cells under immunofluorescence staining with permeabilized cells (Figures 5B and S8). The same trend was observed for VIM and ECAD expression in OVSAYO cells (Figure S9A), in which CD69 expression was partially suppressed.

FIGURE 5.

CD69–fibronectin (FN) interaction causes epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). (A) Western blot analysis of EMT markers in the indicated cells. (B) Immunofluorescent staining of E‐cadherin (ECAD) in the indicated cells and culture conditions. (C) Flow cytometry of cell surface ECAD (csECAD) expressed in nonspecific (NS)#2 cells. (D) Comparison of csECAD levels in the indicated cells. Data are the mean (n = 5) ± SD. *p = 0.024, **p = 0.026, # p = 0.006. Statistical values for two datasets labeled with same symbols were calculated by t‐test. (E) Morphology of the indicated cells cultured under serum starvation and hypoxia (SSH) for 72 h. (F) Immunohistochemistry of vimentin (VIM) expression in xenograft tumor and normal pancreatic tissues shown in Figure 4D. (G) Scheme of cell viability assay. (H) Western blotting of VIM in OVISE cells. (I) Cell viability assay. Blue, OVISE; orange, OVSAYO. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 3 [OVISE], n = 4 [OVSAYO]). Statistical values were calculated by t‐test. SSN, serum starvation and normoxia

Recently, it was suggested that csECAD is decreased by disturbance of its relocalization rather than transcriptional repression to cause EMT. 38 Thus, we further tested whether csECAD was decreased in SSH‐cultured cells. Flow cytometry with unpermeabilized cells and an Ab recognizing the extracellular domain of ECAD revealed that csECAD levels decreased under SSH compared with SSN (Figures 5C,D and S8). Fibronectin coating facilitated the reduction of csECAD in control cells (Figure 5D). This effect was not observed in CD69‐silenced cells (Figure 5D). Unlike CD69‐silenced cells, NS‐shRNA cells caused actual morphological changes with mesenchymal reduced cell–cell contact (Figures 5E and S8). Immunohistochemistry of OVISE tumor tissue grafted in mice showed that, unlike adjacent normal pancreatic tissue, VIM was highly expressed in tumor cells (Figure 5F). Conversely, IHC also showed that, unlike adjacent normal pancreatic cells, csECAD was not obviously identified in tumor cells (Figure S10).

Accumulating evidence has shown that VIM plays roles in EMT‐driven survival of various cancer cell types under stress conditions. 39 , 41 Thus, we tested whether this occurs in CD69‐driven EMT. Control OVISE and OVSAYO cells were treated with siRNA to silence VIM expression (Figures 5G,H and S9B) and then further cultured under SSH on FN‐coated and FN noncoated dishes. We found that the viability of CCC cells cultured on FN‐coated dishes under SSH (cell count 2) was significantly decreased compared with the initial cell viability (cell count 1) by VIM knockdown (Figure 5I). Collectively, these data suggest that CD69 can confer EMT phenotypes through FN.

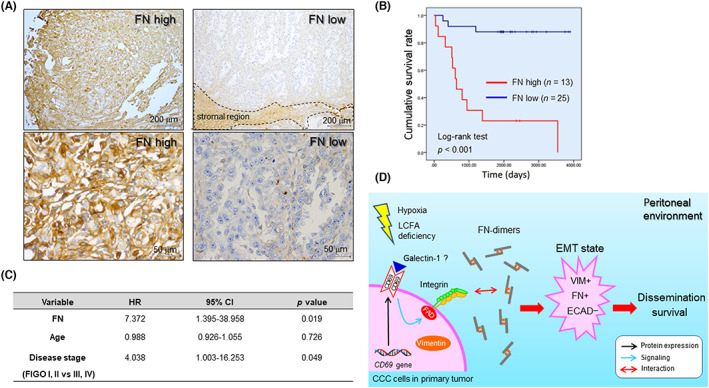

3.9. Fibronectin associated with cancer cells is a prognostic factor of CCC

Fibronectin expressed in tumor stroma and cancer cells is associated with malignancy 42 , 43 , 44 and is correlated with the poor prognosis of ovarian serous carcinoma patients. 44 Furthermore, the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org) showed that the FN transcript level in the TCGA cohort is significantly associated with the poor prognosis of many cancer types including lung, stomach, renal, and ovarian serous carcinoma. Furthermore, the Human Protein Atlas showed that CD69 transcript levels correlated with both good (breast cancer, ovarian serous carcinoma) and poor (renal cancer, pancreatic cancer) prognosis in multiple cancer types. However, the effect of CD69 and FN on the prognosis of CCC patients has not been reported. Thus, we next examined relationship between cancer cell‐derived CD69, FN associated with cancer cells, and the prognosis of CCC patients. We first examined by IHC whether CD69 was correlated with the prognosis of CCC patients using a TMA (Figure S11A) and whole‐tissue sections (Figure S11B, Table S2), but did not find an association between them. We next undertook IHC for FN (Figure 6A). Scoring expression levels followed by Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that FN levels were strongly correlated with the poor prognosis of CCC (Figure 6B). Multivariable analysis showed that FN is a prognostic factor, with a risk ratio of 7.372, which is greater than that of the disease stage (Figure 6C). Collectively, the level of cancerous FN dictates the prognosis of CCC patients.

FIGURE 6.

Tumor cell fibronectin (FN) is correlated with the poor prognosis of ovarian clear cell carcinoma (CCC) patients. (A) Typical staining pattern of FN in CCC tumor cells. (B) Kaplan–Meier analysis of the relationship between overall survival rate and FN level in CCC patients. (C) Multivariable analysis of overall survival rate. (D) Model of the CD69–FN axis‐driven phenotypes of CCC cells in peritoneal environments. CI, confidence interval; ECAD, E‐cadherin; EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; HR, hazard ratio; LCFA, long‐chain fatty acid; VIM, vimentin

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we provided a novel concept that CD69 is strongly expressed in epithelial, nonhematological CCC cells, as in ICAM1. 10 Induced CD69 protein is responsible for FN‐driven EMT, potentially contributing to the poor prognosis of CCC patients. This differs from the function of ICAM‐1, which enables CCC cells to become more resistant to SSH‐driven apoptosis. 9 , 10

Conformational changes of β1‐integrin likely increased the association of CCC cells with FN because components of the FAK complex that closely associate with integrin activation are phosphorylated in relation to CD69 induction. The present study revealed that multiple signaling molecules other than ERK and AKT are phosphorylated in response to CD69 expression. However, the question arises as to how cell surface CD69 can be activated without a ligand supply from blood plasma. Epithelial ovarian cancer cells might autonomously synthesize functional ligands for CD69 (Figure 6D), as supported by a study reporting that galectin‐1 can be a functional ligand for CD69, resulting in T cell differentiation. 45 Indeed, we detected galectin‐1 expression in CCC cells (Figure S11C). Ligand‐independent signaling could also be possible, as in epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. 46

The major form of EOC metastasis is peritoneal dissemination. Previous studies reported that FN levels are high in ovarian tumor stroma and ascites because cancer cells can promote the secretion of FN from NT cells in peritoneal environments. 32 , 33 Indeed, we showed that FN is abundant in the ascites and tumor cells of mice inoculated with CD69‐expressing cells. Given that ascites FN levels were consistent with tumor burden in the peritoneal cavity, CCC cells may induce FN production from mesothelial cells through cytokines. 33 , 37 However, our comprehensive analysis and ELISA (data not shown) did not detect CD69‐driven phosphorylation of SMAD or secretion of TGF‐β1, respectively. Thus, the canonical TGF‐β1–phospho‐SMAD axis 33 , 37 is not involved in CD69–FN interaction‐driven EMT.

This study first determined that tumor FN but not CD69 in CCC clinical specimens is significantly correlated with the poor prognosis of patients, although the sample size was limited. Given that FN facilitates tumor progression through multiple molecular mechanisms across many cancer types, 42 , 43 aggressiveness and prognosis might primarily depend on FN rather than tumor cell‐derived CD69, as shown in this study. However, the relative importance of CD69 could vary between CCC cases given our OVISE tumor model.

In the present study, we could not fully exclude the possibility that CD69 detected in clinical CCC specimens was partly derived from immune cells. CD69 is known to play roles in antitumor immunity, 47 , 48 and indeed, CD69 expression in the TCGA cohort is significantly associated with better prognosis in many cancer types, including ovarian serous carcinoma. In contrast, CD69 expressed in T cells can cause protumoral effects, and therefore can be potentially targeted for cancer immunotherapy. 14 Thus, co‐existence of anti‐ and protumor CD69 together with tumor FN level might explain the lack of association between CD69 expression and prognosis in the current CCC patient cohort. In this case, tumor‐FN rather than tumor‐CD69 might be a better therapeutic target of CCC with blocking Abs 33 and Ab–drug conjugate targeting extra domains of FN. 42 , 43

In summary, our data provide evidence as to how cancer cell‐derived CD69 is expressed and functions in CCC progression. However, it is currently unclear whether this is possible in other cancer types. Further studies of CD69 synthesized in epithelial tumor cells in a larger patient cohort and multiple cancer types could lead to the generation of widely applicable diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to T.K. (grant no. 25830097), and to S.K. and Y.M. (grant nos. JP16H06277 and JP22H04923).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol by an institutional review board: Approved by institutional review board at Kanagawa Cancer Center Research Institute (No. 177).

Informed consent: Written consent was obtained from all patients.

Registry and registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: Animal experiments were approved by institutional review board at Kanagawa Cancer Center Research Institute.

Supporting information

Data S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Nikki March, PhD, from Edanz for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Koizume S, Kanayama T, Kimura Y, et al. Cancer cell‐derived CD69 induced under lipid and oxygen starvation promotes ovarian cancer progression through fibronectin. Cancer Sci. 2023;114:2485‐2498. doi: 10.1111/cas.15774

Contributor Information

Shiro Koizume, Email: skoizume@gancen.asahi.yokohama.jp.

Yohei Miyagi, Email: miyagi@gancen.asahi.yokohama.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bertout JA, Patel SA, Simon MC. The impact of O2 availability on human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:967‐975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumor growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:9‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. del Carmen MG, Birrer M, Schorge JO. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:481‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sung P‐L, Chang Y‐H, Chao K‐C, Chuang C‐M. Global distribution pattern of histological subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer: a database analysis and systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:147‐154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bast RC Jr, Hennessy B, Mills GB. The biology of ovarian cancer: new opportunities for translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:415‐428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Young RM, Ackerman D, Quinn ZL, et al. Dysregulated mTORC1 renders cells critically dependent on desaturated lipids for survival under tumor‐like stress. Gens Dev. 2013;27:1115‐1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lewis CA, Brault C, Peck B, et al. SREBP maintains lipid biosynthesis and viability of cancer cells under lipid‐oxygen‐derived conditions and defines a gene signature associated with poor survival in glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogene. 2015;34:5128‐5140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ackerman D, Tumanov S, Qiu B, et al. Triglyceride promote lipid homeostasis during hypoxic stress by balancing fatty acid saturation. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2596‐2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koizume S, Ito S, Nakamura Y, et al. Lipid starvation and hypoxia synergistically activates ICAM1 and multiple genes in an Sp1 dependent manner to promote the growth of ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koizume S, Takahashi T, Nakamura Y, et al. Lipophagy‐ICAM‐1 pathway associated with fatty acid and oxygen deficiencies is involved in poor prognosis of ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2022;127:462‐473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koizume S, Takahashi T, Yoshihara M, et al. Cholesterol starvation and hypoxia activate the FVII gene via the SREBP1‐GILZ pathway in ovarian cancer cells to produce procoagulant microvesicles. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119:1058‐1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ziegler SF. Molecular characterization of the early activation antigen CD69: a type II membrane glycoprotein related to a family of natural killer cell activation antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1643‐1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin P, Sánchez‐Madrid F. CD69: an unexpected regulator of Th17 cell‐driven inflammatory responses. Sci Signal. 2011;4:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koyama‐Nasu R, Wang Y, Hasegawa I, Endo Y, Nakayama T, Kimura MY. The cellular and molecular basis of CD69 function in anti‐tumor immunity. Int Immunol. 2022;34:555‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koizume S, Jin M‐S, Miyagi E, et al. Activation of cancer cell migration and invasion by ectopic synthesis of coagulation factor VII. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9453‐9460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Okayama A, Miyagi Y, Oshita F, et al. Identification of tyrosine‐phosphorylated proteins upregulated during epitherial–mesenchymal transition induced with TGF‐β. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:4127‐4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okayama A, Kimura Y, Miyagi Y, et al. Relationship between phosphorylation of sperm‐specific antigen and prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. J Proteomics. 2016;139:60‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ota Y, Koizume S, Nakamura Y, et al. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor‐2 is specifically expressed in ovarian clear cell carcinoma tissues in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and extracellular matrix. Oncol Rep. 2021;45:1023‐1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koya Y, Kajiyama H, Liu W, Senga T, Kikkawa F. Murine experimental model of original tumor development and peritoneal metastasis via orthotopic inoculation with ovarian carcinoma cells. J Vis Exp. 2016;118:e54353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. López‐Cabrera M, Muñoz E, Blázquez MV, Ursa MA, Santis AG, Sánchez‐Madrid F. Transcriptional regulation of the gene encoding the human C‐type lectin leukocyte receptor AIM/CD69 and functional characterization of its tumor necrosis factor‐α‐responsive elements. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21545‐21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Swan DJ, Kirby JA, Ali S. Post‐transplant immunosuppression: regulation of the efflux of allospecific effector T cell from lymphoid tissues. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim G, Jang MS, Son YM, et al. Curcumin inhibits CD4+ T cell activation, but augments CD69 expression and TGF‐β1‐mediated generation of regulatory T cells at late phase. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zingoni A, Palmieri G, Morrone S, et al. CD69‐triggered ERK activation and functions are negatively regulated by CD94/NKG2‐a inhibitory receptor. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:644‐651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martín P, Gómez M, Lamana A, et al. CD69 association with Jak3/Stat5 proteins regulates Th17 cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4877‐4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zeng ZZ, Jia Y, Hahn NJ, Markwart SM, Rockwood KF, Livant DL. Role of focal adhesion kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3′‐kinase in integrin fibronectin receptor‐mediated, matrix metalloproteinase‐1‐dependent invasion by metastatic prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8091‐8099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mitra AK, Sawada K, Tiwari P, Mui K, Gwin K, Lengyel E. Ligand‐independent activation of c‐met by fibronectin and a5b1‐integrin regulates ovarian cancer invasion and metastasis. Oncogene. 2011;30:1566‐1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhao J, Guan J‐L. Signal transduction by focal adhesion kinase in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:35‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jin J‐K, Tien P‐C, Cheng C‐J, et al. Talin 1 phosphorylation activates β1 integrins: a novel mechanism to promote prostate cancer bone metastasis. Oncogene. 2015;34:1811‐1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Balzac F, Avolio M, Degani S, et al. E‐cadherin endocytosis regulates the activity of Rap1: traffic light GTPase at the crossroads between cadherin and integrin function. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4765‐4783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greco C, Bralet M‐P, Ailane N, et al. E‐cadherin/p120‐catenin and tetraspanin Co‐029 cooperate for cell motility control in human colon carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7674‐7683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kasiazek K, Mikula‐Pietrasik J, Korybalska K, Dworacki G, Jorres A, Witowski J. Senescent peritoneal mesothelial cells promote ovarian cancer cell adhesion. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1230‐1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kenny HA, Chiang C‐Y, White EA, et al. Mesothelial cells promote early ovarian cancer metastasis through fibronectin secretion. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4614‐4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Du J, Chen X, Liang X, et al. Integrin activation and internalization on soft ECM a mechanism of induction of stem cell differentiation by ECM elasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9466‐9471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koizume S, Miyagi Y. Potential coagulation factor‐driven pro‐inflammatory responses in ovarian cancer tissues associated with insufficient O2 and plasma supply. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Srivastava AK, Banerjee A, Cui T, et al. Inhibition of miR‐328–3p impairs cancer stem cell function and prevents metastasis in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:2314‐2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gomes AP, Ilter D, Low V, et al. Age‐induced accumulation of methylmalonic acid promotes tumour progression. Nature. 2020;585:283‐287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aiello NM, Maddipati R, Norgard RJ, et al. EMT subtype influences epithelial plasticity and mode of cell migration. Dev Cell. 2018;45:681‐695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tomihara H, Carbone F, Perelli L, et al. Loss of ARID1A promotes epithelial‐mesenchymal transition and sensitizes pancreatic tumors to proteotoxic stress. Cancer Res. 2021;81:332‐343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kyuno D, Takasawa A, Kikuchi S, Takemasa I, Osanai M, Kojima T. Role of tight junctions in the epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition of cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2021;1863:18503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chakraborty S, Kumar A, Faheem MM, et al. Vimentin activation in early apoptotic cancer cells errands survival pathways during DNA damage inducer CPT treatment in colon carcinoma model. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rick JW, Chandra A, Ore CD, Nguyen AT, Yagnik G, Aghi MK. Fibronectin in malignancy: cancer‐specific alterations, protumoral effects, and therapeutic implications. Semin Oncol. 2019;46:284‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lin TC, Yang C‐H, Li‐H C, Chang W‐T, Lin Y‐R, Cheng H‐C. Fibronectin in cancer: friend or foe. Cells. 2020;9:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kujawa KA, Zembala‐Nożyńska E, Cortez AJ, Kujawa T, Kupryjanczyk J, Lisowska KM. Fibronectin and periostin as prognostic markers in ovarian cancer. Cells. 2020;9:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. de la Fuente H, Cruz‐Adalia A, del Hoyo GM, et al. The leukocyte activation receptor CD69 controls T cell differentiation through its interaction with galectin‐1. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:2479‐2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guo G, Bryan KG, Wohlfeld B, Hatanpaa KJ, Zhao D, Habib AA. Ligand‐independent EGFR signaling. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3436‐3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lan B, Zhang J, Lu D, Li W. Generation of cancer‐specific CD8+ CD69+ cells inhibits colon cancer. Immunobiology. 2016;221:1‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sekar D, Hahn C, Brüne B, Roberts E, Weigert A. Apoptotic tumor cells induce IL‐27 release from human DCs to activate Treg cells that express CD69 and attenuate cytotoxicity. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1585‐1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.