ABSTRACT

Background:

Weight gain associated with atypical antipsychotic medications need to be well managed. We set out: 1. To test the effect of acetazolamide on weight gain associated with antipsychotics 2. To assess improvement in psychotic symptoms using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale score on patients receiving acetazolamide

Methods and Materials:

This open-label study conducted after institutional ethical clearance from December 2018 to August 2020 included 34 drug-naive patients or patients on antipsychotic risperidone or olanzapine for less than one month. They were divided into two groups of 17 each as a case group (treatment as usual + acetazolamide) and a control group (treatment as usual) who were followed up for eight weeks. The patient’s physical characteristics were recorded at baseline and during follow-ups. The Brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS) and clinical global impression (CGI) scores were compared for the cases and controls.

Results:

The study showed non-significant reduction in the weight (–0.57 ± 1.06 kg), body mass index (BMI) (–0.23 ± 0.76 kg/m2) and abdominal circumference (–0.47 ± 1.37 cm) in the patients receiving oral acetazolamide at the end of two months as compared to controls where there was significant increase in the weight (+2.62 ± 1.09 kg), BMI (+1.03 ± 0.44 kg/m2) and abdominal circumference (+2.21 ± 1.33 cm, P = 0.001). Similarly, the BPRS and CGI scores were significantly reduced in both arms, with satisfaction rates better among the cases compared to controls.

Conclusion:

There was a non-significant reduction in the weight, body mass index, abdominal circumference, and brief psychiatric rating scale scores in patients treated with acetazolamide.

Ethics committee protocol number: - 2018/244

CTRI India registration number: CTRI/2019/05/018884

Keywords: Acetazolamide, antipsychotic, olanzapine, risperidone, schizophrenia, weight

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric disorder having positive, negative, affective, and cognitive symptoms. It is a disease that may require long-term antipsychotic treatment. Given the poor adherence associated with weight gain and obesity, clinicians need to monitor weight during the course of antipsychotic treatment and consider switching agents when excessive weight gain occurs.[1] The bodyweight and metabolic risk profile of patients receiving atypical antipsychotic medications need to be effectively managed with a weight control program like physical activity and diet, which is difficult in an illness like schizophrenia.[2]

Acetazolamide is a sulfa-like moiety that is a potent non-specific inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase enzymes.[3] The mechanism of action of acetazolamide is similar to topiramate or zonisamide, which are known to cause weight loss.[3] Acetazolamide came into clinical usage in 1952 and has been used for more than seven decades. It is a safe, effective, very economically priced generic drug that is on the WHO (World Health Organisation) list of essential drugs. Acetazolamide is available both in the oral and intravenous forms, which can be useful in an illness like schizophrenia.[4] Acetazolamide is indicated for centrencephalic epilepsies, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, secondary glaucoma, and preoperatively in acute angle-closure glaucoma where delay of surgery is desired to lower intraocular pressure.[4] It has a beneficial effect on psychogenic polydipsia.[5] Common side effects of acetazolamide include headache, tingling, dizziness, diuresis, tiredness, confusion, anorexia, and weight loss. One of the common adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs is weight gain and metabolic side effects.[6]

In a recent bioinformatics study done to identify drugs that can be repurposed for use in schizophrenia, it was observed that the protein target network of acetazolamide was closely related to various neuropsychiatric disorders. Acetazolamide has high inhibitory activity against human CA2 (hCA II), the ubiquitous cytosolic enzyme (inhibition constant, Ki = 12nM), and human CA7 (Ki = 2.5nM), the brain-specific form of the enzyme. This is one of the drugs which have the potential to be repurposed for use in schizophrenia.[7]

In a recently published study, acetazolamide was combined with sodium valproate in persons with bipolar disorder, which helped in reducing weight gain.[8] Most antipsychotics cause weight gain. This study is the first attempt to see if the addition of acetazolamide can prevent weight gain or reduce weight in persons taking antipsychotics like risperidone or olanzapine. Acetazolamide has shown some evidence as an antipsychotic, so it is a good candidate as a weight loss agent to be combined with a first-line antipsychotic in schizophrenia.[9] We decided to study the effect of acetazolamide on weight gain associated with antipsychotic drugs and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores on patients receiving the acetazolamide

METHODS AND MATERIALS

It is an open-labeled randomized study conducted at a tertiary care teaching hospital after obtaining institutional ethical clearance from December 2018 to August 2020. Ethical approval was obtained for Protocol number - 2018/244 from Institutional ethics committee -1, which is recognized by Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review (SIDCER) - Forum for Ethical Review Committees in the Asian and Western Pacific Region (FERCAP) and registered with the office of Drug Controller General of India. As this is the first study for an unapproved indication, a routine audit was done by the institutional ethical committee during the study period on 13/Aug/2020 and the study was cleared. This study was registered under the Clinical Trials Registry India (CTRI), with reference number CTRI/2019/05/018884. The study drug was provided by the researchers, and no financial/other incentives were provided for participation in the study.

A total of 39 patients diagnosed using International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) criteria with either schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder or psychosis not otherwise specified were screened, out of which 34 patients who were drug-naive or treated with risperidone/olanzapine for less than one month were included in the study after obtaining written informed consent. Patients were divided into two groups of 17 each by lottery method as case group (treatment as usual + acetazolamide) and control group (treatment as usual). The control group was on risperidone or olanzapine, depending on the treating clinician’s choice, which was treatment as usual group. The doses of their antipsychotics in both groups were decided by the treating clinician. Weight neutral drugs like trihexyphenydyl or lorazepam were allowed in both groups as needed. Detailed clinical examination and routine laboratory investigations were done to rule out medical problems prior to recruitment. Persons already on acetazolamide for any other reason, a pre-existing medical condition in which acetazolamide is contraindicated, pregnancy, lactating mothers, and persons with sub-normal intelligence were excluded from the study.

The study group received treatment as usual + Tab Acetazolamide. Acetazolamide was started at 125 mg BD per day initially gradually hiked to the maximum tolerable dose of 500 mg per day (the maximum recommended dose of acetazolamide is 2000 mg per day). Patient’s height in centimeters, and weight in kilograms were measured using the same digital scale, body mass index; abdominal girths in centimeters at the level of umbilicus were measured at 0, 2, 4, and at the end of 8 weeks follow-up. A separate adverse effect monitoring sheet was used to monitor side effects at the baseline and during each follow-up visit.

Medication adherence was monitored by family members as all the participants were accompanied by at least one family member.

Assessment Tools: Demographic and clinical details were collected using a specially designed proforma for both cases and controls, which included age, gender, educational status, socio-economic status, duration of illness, duration of current medication, nicotine use, and co-morbid medical illness. The Brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS) and Clinical global impression (CGI) scores were also compared between the cases and controls.

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale is an 18-item rating scale developed by John E Overall and Gorham D R (1962). The scale provides a description of major symptom characteristics and also helps in assessing treatment changes in psychiatric patients.[10]

Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale: The Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S) is a 7-point scale developed by William Guy (1976) that requires the clinician to rate the severity of the patient’s illness at the time of assessment, relative to the clinician’s past experience with patients who have the same diagnosis.[11]

Clinical Global Impression Improvement Scale: The Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale (CGI-I) is a 7 point scale developed by William Guy (1976) that requires the clinician to assess how much the patient’s illness has improved or worsened relative to a baseline state from the beginning of the intervention.[11]

The sample size was calculated by using G-power (version 3.1.9.2) software with the level of significance α = 5%, power 1- β = 80%. A sample size of 34 was needed with 17 cases and 17 controls.

All the patient data was entered in an Excel sheet, and statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 21 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA), operating on windows 10.

Data availability statement: The data generated during the study is available from the first author on reasonable request.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic details of all the study participants. Among the participants, 13 (38.23%) were males, and 21 (61.76) were females; 21 (61.76%) patients belonged to the Hindu religion and 13 (38.23%) to the Muslim religion. The majority of them resided in rural areas (24; 70.58%) and belonged to a low socio-economic status (27; 79.41%). Out of 34 patients included in the study, 30 (88.23%) were vegetarians, and four (11.64%) were omnivores.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic data of cases and controls

| Cases | Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Count | % | Count | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 6 | 35.3% | 7 | 41.2% |

| Female | 11 | 64.7% | 10 | 58.8% |

| Education | ||||

| Illiterate | 1 | 5.9% | 3 | 17.6% |

| Primary | 6 | 35.3% | 5 | 29.4% |

| High school | 6 | 35.3% | 5 | 29.4% |

| Higher secondary | 3 | 17.6% | 3 | 17.6% |

| Graduate | 1 | 5.9% | 1 | 5.9% |

| Post graduate | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | 12 | 70.6% | 9 | 52.9% |

| Christian | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Muslim | 5 | 29.4% | 8 | 47.1% |

| Place | ||||

| Urban | 2 | 11.8% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Semi urban | 4 | 23.5% | 4 | 23.5% |

| Rural | 11 | 64.7% | 13 | 76.5% |

| Socio-economic status | ||||

| Low | 13 | 76.5% | 14 | 82.4% |

| Middle | 4 | 23.5% | 3 | 17.6% |

| High | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Diet | ||||

| Omnivore | 14 | 82.4% | 16 | 94.1% |

| Vegetarian | 3 | 17.6% | 1 | 5.9% |

The nicotine use in patients among the two groups showed that only nine patients were using nicotine, in which the cases had three patients and the control group had six patients.

Among 34 participants, 11 were drug-naïve, and 23 were on medication with risperidone/Olanzapine for less than one month Table 2 shows the use of current medication in the patients, in which 24 were on risperidone and ten were on olanzapine.

Table 2.

Showing the distribution of current medication among the patients

| Cases | Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Count | % | Count | % | |

| Current Medication | ||||

| Risperidone | 12 | 70.6% | 12 | 70.6% |

| Olanzapine | 5 | 29.4% | 5 | 29.4% |

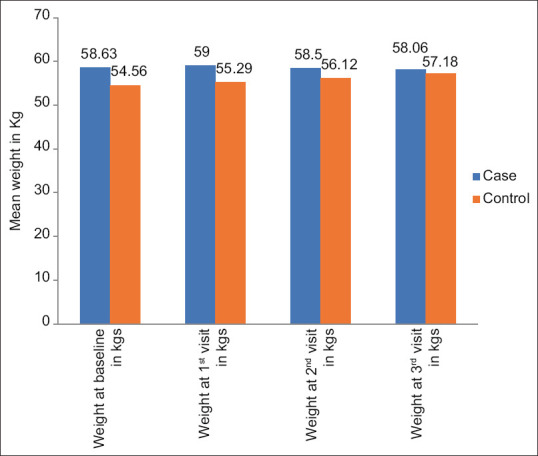

Table 3 shows the comparison of mean weight of patients between the cases and controls. Table 4 shows the comparison of the mean weight of patients at various visits within the group. There was a significant increase in the weight of the patients among the controls at follow-up compared to the baseline. However, the weight in the cases did not show any significant difference, but overall there was a reduction in the weight in cases compared to the controls. In the control group, there was a significant increase in the weight (+2.62 kg), and in the cases, there was a non-significant reduction in the weight (–0.57 kg) [Figure 1]. Also, as the acetazolamide dose increased to 250 mg/day from the second follow-up, there was a tendency to lose weight.

Table 3.

Comparison of the mean weight of patients at various visits between the groups using student t-test

| Cases | Controls | t | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Weight at baseline in kgs | 58.63 | 10.52 | 54.56 | 12.42 | 1.031 | 0.310 |

| Weight at 1st visit in kgs | 59.00 | 10.80 | 55.29 | 12.19 | 0.938 | 0.355 |

| Weight at 2nd visit in kgs | 58.50 | 10.97 | 56.12 | 12.33 | 0.595 | 0.556 |

| Weight at 3rd visit in kgs | 58.06 | 10.89 | 57.18 | 12.18 | 0.223 | 0.825 |

P<0.05 is statistically significant, and P<0.001 is statistically highly significant

Figure 1.

Comparison of the mean weight of patients at various visits between the groups

Table 4.

Comparison of the mean weight of patients at various visits within the groups using paired t-test

| Weight | Baseline visit Mean±SD | 1st visit Mean±SD | t (P) a*b | 2nd visit Mean±SD | t (P) a*c | 3rd visit Mean±SD | t (P) a*d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 58.62±10.52 | 59.0±10.80 | –1.718 (0.105) | 58.50±10.97 | 0.346 (0.734) | 58.05±10.89 | 1.197 (0.249) |

| Controls | 54.55±12.41 | 55.29±12.18 | –4.564 0.001** | 56.11±12.33 | –6.765 (0.001**) | 57.17±12.17 | –9.836 (0.001**) |

P<0.05 is statistically significant, and P<0.001 is statistically highly significant

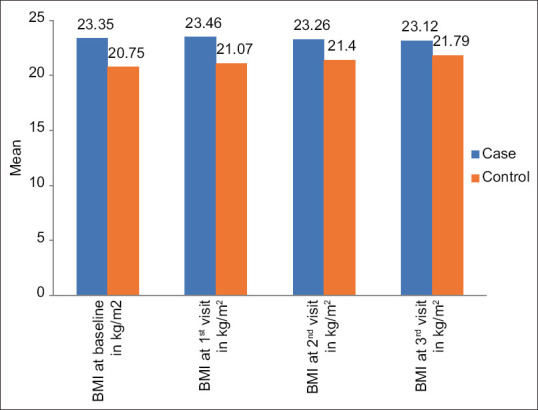

Table 5, on comparing the mean Body Mass Index of patients at various visits within the group, shows that there was a significant increase in the Body Mass Index of the patients in the control group at follow-up compared to the baseline. However, the Body Mass Index in cases did not show any significant difference, but overall there was a reduction in the Body Mass Index in the cases compared to the controls. In the control group, there was a significant increase in the BMI (+1.03 kg/m2), and in the cases, there was a non-significant reduction in the BMI (–0.23 kg/m2).

Table 5.

Comparison of the mean BMI of patients at various visits within the groups using paired t-test

| BMI | Baseline visit Mean±SD | 1st visit Mean±SD | t (P) df=16 a*b | 2nd visit Mean±SD | t (P) df=16 a*c | 3rd visit Mean±SD | t (P) df=16 a*d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 23.34±2.43 | 23.46±2.54 | –1.661 (0.116) | 23.26±2.51 | 0.572 (0.575) | 23.11±2.48 | 1.236 (0.234) |

| Controls | 20.75±4.1 | 21.07±4.02 | –3.816 (0.001**) | 21.40±4.02 | –6.719 (0.001**) | 21.78±3.98 | –9.638 (0.001**) |

P<0.05 is statistically significant, and P<0.001 is statistically highly significant

Table 6 and Figure 2 show the mean difference in the BMI between the cases and controls. The BMI was significantly higher among the patients in cases compared to controls at the baseline and the 1st visit of follow-up. However, at the 2nd and 3rd visits, the difference in BMI was not statistically significant. A trend of increase in BMI was noted in the controls compared to the cases at various visits.

Table 6.

Comparison of the mean BMI of patients at various visits between the groups using student t-test

| Cases | Control | t (df=32) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| BMI at baseline in kg/m2 | 23.35 | 2.44 | 20.75 | 4.16 | 2.21 | 0.034* |

| BMI at 1st visit in kg/m2 | 23.46 | 2.55 | 21.07 | 4.03 | 2.071 | 0.047* |

| BMI at 2nd visit in kg/m2 | 23.26 | 2.52 | 21.40 | 4.03 | 1.619 | 0.115 |

| BMI at 3rd visit in kg/m2 | 23.12 | 2.49 | 21.79 | 3.98 | 1.167 | 0.252 |

P<0.05 is statistically significant, and P<0.001 is statistically highly significant

Figure 2.

Comparison of the mean BMI of patients at various visits between the groups

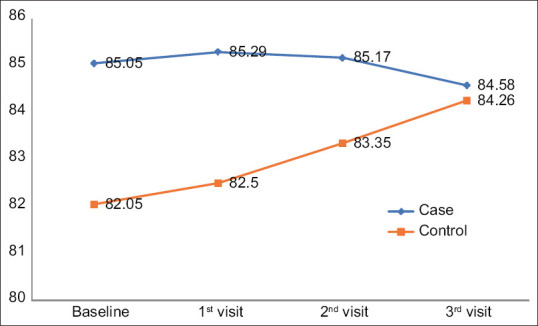

Table 7 and Figure 3 show the comparison of the mean abdominal circumference of patients at various visits within the groups. It shows that there was a significant increase in the abdominal circumference of the patients in the controls at follow-up compared to the baseline. However, the abdominal circumference in cases did not show any significant difference, but overall there was a reduction in the abdominal circumference in the cases compared to the controls. In the control group, there was a significant increase in the abdominal circumference (+2.21 cms), and in the cases, there was a non-significant reduction in the abdominal circumference (–0.47 cms).

Table 7.

Comparison of the mean Abdominal circumference of patients at various visits within the groups using paired t-test

| Abdominal circumference | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | t (P) df=16 a*b | Mean±SD | t (P) df=16 a*c | Mean±SD | t (P) df=16 a*d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Baseline visit (a) | 1st visit (b) | 2nd visit (c) | 3rd visit (d) | ||||

| Cases | 85.05±9.32 | 85.29±9.4 | –1.515 (0.149) | 85.17±9.30 | –0.523 (0.608) | 84.58±9.21 | 1.411 (0.177) |

| Controls | 82.05±12.72 | 82.50±12.34 | –2.667 (0.017*) | 83.35±12.75 | –5.913 (0.001**) | 84.26±13.08 | –6.811 (0.001**) |

P<0.05 is statistically significant, and P<0.001 is statistically highly significant

Figure 3.

Comparison of the mean abdominal circumference of patients at various visits between the groups

On comparing the mean change in BMI within the case group, BMI reduction at the last visit among cases with a baseline of more than 25 kg/m2 was found to be greater (–1.71 kg/m2) compared to the cases with a baseline BMI less than 25 kg/m2 (–1.25 kg/m2); however, this was not statistically significant [Table 8].

Table 8.

Showing the BMI changes in cases from baseline

| BMI at baseline | Mean change at last visit±SE | Median | Mann-Whitney U-Test (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 25 kg/m2 | –1.25±0.79 | –1.94 | 35.00 (0.725) |

| > 25 kg/m2 | –1.71±1.04 | –1.52 |

*P<0.05 is statistically significant, Mann-Whitney U-Test.

Table 9 shows the comparison of the mean of BPRS scores at the first and last visits within cases and compared to the controls, which shows there was a significant improvement in the BPRS scores among both cases and controls.

Table 9.

Comparison of mean of BPRS at first and last visit within the groups by paired t-test

| BPRS score | First visit Mean±SD | Last visit Mean±SD | t (df=16) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 47.47±13.09 | 33.64±8.88 | 8.028 | 0.001** |

| Controls | 53.05±17.37 | 39.05±13.32 | 6.918 | 0.001** |

P<0.05 is statistically significant, and P<0.001 is statistically highly significant

Table 10 shows a comparison of mean CGI at the first and last visits within the group and compared to the control group. There was a significant improvement in the CGI scores both among cases and controls.

Table 10.

Comparison of mean of CGI at first and last visit within the groups by paired t-test

| CGI | First visit Mean ± SD | Last visit Mean ± SD | t (df=16) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 4.76 ± 0.90 | 2.11 ± 0.48 | 12.66 | 0.001** |

| Controls | 5.23 ± 0.75 | 2.23 ± 0.43 | 14.28 | 0.001** |

P<0.05 is statistically significant, and P<0.001 is statistically highly significant

Adverse effects seen in the first week were tingling sensations, nausea, and headache. Further, in the 2nd week, patients reported stomach ache, tiredness, and loss of appetite. At the 4th week, patients reported the presence of tiredness, light-headedness, headache, and loss of appetite. By the 8th week of follow-up, the majority of symptoms patients presented were loss of appetite, followed by headache, nausea and tiredness, and light-headedness. None of the patients discontinued medications due to adverse effects, and all 34 completed the study.

Table 11 compares the various pharmacological treatments used to manage weight gain associated with antipsychotic drugs in patients including this study.

Table 11.

List of various pharmacological treatments used to manage weight gain associated with antipsychotic drugs

| Authors | Design | Duration (weeks) | Group | Age (yrs) | Antipsychotic used | Weight changes (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deberdt et al.[12]; (2005) | Double blind placebo controlled | 16 | Amantadine 100-300 mg Placebo | 40±12 41±12 | Olanzapine | –0.19+1.28 |

| Graham et al.[13]; (2005) | Double blind placebo controlled | 12 | Amantadine 300 mg/day Placebo | Adult | Olanzapine | –0.36+3.95 |

| Baptista et al.[14]; (2007) | Double blind placebo controlled | 12 | Metformin 850-2550 mg/day Placebo | 44.3 44.6 | Olanzapine | –1.4 0.18 |

| Baptista et al.[15]; (2008) | Double blind placebo controlled | 12 | Metformin 850-2550 mg/day + sibutramine Placebo | 45.5 49.3 | Olanzapine | –2.8 –1.4 |

| Klein et al.[16]; (2006) | Double blind placebo controlled | 16 | Metformin 250-850 mg/day Placebo | 12.9 13.3 | Olanzapine, Risperidone | –0.13+4.01 |

| Atmaca et al.[17]; (2003) | Double blind placebo controlled | 8 | Nizatidine 150 mg bd Placebo | 27.1 28.7 | Olanzapine | –4.5+2.3 |

| Chengappa et al.[18]; (2007) | Double blind placebo controlled | 8 | Topiramate 300 mg/day placebo | 42.6 42.8 | Valproate | –1.49+2.72 |

| Our study | Open-labeled randomized controlled | 8 | Acetazolamide | 37.76 45.29 | Risperidone and Olanzapine | –0.57+2.62 |

DISCUSSION

In patients with schizophrenia or psychosis, several factors contribute to weight gain. The main contributors are a sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy food habits, genetic susceptibility, and antipsychotic medications. Antipsychotic associated weight gain is a major concern in the treatment of psychosis patients[19]

A longitudinal observational analysis interviewing 63 first episode patients aged between 14and 35 years found that a change in self-identity resulted due to weight gain.[19] Poor satisfaction and distress were significantly associated with weight gain, whereas cognitive side effects and sexual dysfunction were particularly more common in females.[19] In the Weiden et al.[20] report, the primary mediator of non-compliance was found to be subjective anxiety over weight gain. It was also found that patients who were obese were 13 times more likely to discontinue medication because of weight gain than non-obese patients.

For medication associated with weight gain and obesity, physicians should track weight during antipsychotic therapy and recommend switching agents if there is a significant weight gain.[1] In patients receiving atypical antipsychotic medications, body weight and metabolic risk profile need to be effectively managed with a weight control program, including physical activity, which is challenging in diseases such as schizophrenia.[2]

The pharmacological interventions shown to be effective in reducing the weight in patients on antipsychotic treatment are metformin,[21] orlistat,[22] sibutramine,[22] topiramate,[23] zonisamide,[24] amantadine,[13] aripiprazole,[25] famotidine,[26] rosiglitazone,[19] dextroamphetamine,[19] fluvoxamine.[19] This study was conducted to assess the effect of acetazolamide on patients taking antipsychotic medications associated with weight gain.

A total of 34 patients were included in the present study who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were segregated into cases N = 17 and controls N = 17 patients. The mean age of all the patients was 41.52 years, with 13 males and 21 females (with a female preponderance). There was no significant mean age difference between the groups (P = 0.07).

Since the risk of weight gain in the first year of treatment tends to be the greatest, we included drug-naive patients who are off antipsychotics for at least one year. If on antipsychotic drugs, they should be for less than four weeks on either risperidone or olanzapine.

In the control group, there was a significant increase in the weight (+2.62 kg), BMI (+1.03 kg/m2), and abdominal circumference (+2.21 cms); and in the cases, there was a non-significant reduction in weight (–0.57 kg), BMI (–0.23 kg/m2), and abdominal circumference (–0.47 cms) at the end of eight weeks. Similar findings were observed in a previous study[27]

Within the case group, BMI reduction at the last visit among patients with a baseline of more than 25 kg/m2 is greater (–1.71 kg/m2) than in the cases with a baseline BMI of less than 25 kg/m2 (–1.25 kg/m2); however, this was not statistically significant. This indicates that the effect of acetazolamide on weight could be more in people with higher BMI.

The BPRS score and CGI score were not significantly different between the groups; however, on paired t-test analysis within the groups, there was a significant reduction of both the scores in cases and controls. At the last visit of the study, BPRS scores among the cases (33.64 ± 8.88) were lower than the controls (39.05 ± 13.32) (non-significant); similarly, the mean CGI was lower in the cases (2.11 ± 0.48) compared to controls (2.23 ± 0.43). There was a significant reduction in BPRS scores in cases by 29.13% and 26.39% in the controls; similarly, the CGI scores reduced by 55.67% among the cases and 57.36% among the controls. These findings are in line with studies done by Inoue H et al.[28] and Sacks W et al.[29] This shows that acetazolamide does not increase the psychotic symptoms and may help in reducing them.

Acetazolamide was given at a lower dose in this study compared to the maximum dose of 2000 mg to minimize side effects, drops outs, and ethical issues, as it is the first study done for this indication.

Further studies can look at a larger sample size with a longer study duration to assess the potential benefits of acetazolamide on weight. Acetazolamide has not increased psychosis hence has an added advantage of being used in patients with psychosis.

Common adverse effects of acetazolamide are nausea, tiredness, tingling, paresthesia, dizziness, diuresis, weakness, altered taste, and anorexia. One of the important adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs is weight gain and metabolic syndrome.[6,9] The adverse effects were assessed at the first week, 2nd week, 4th week, and 8th week of treatment. The common adverse effects encountered in the present study were headache, gastritis nausea, light-headedness, tiredness, and loss of appetite. Adverse effects were minimally observed with acetazolamide as it has a high safety margin, as reported by Inoue et al.[28]

This is the first clinical study, according to the investigators looking at acetazolamide as a weight loss agent along with an antipsychotic drug in an illness like schizophrenia. The strengths of this study are an adequate sample size, participation of drug-naive patients, use of validated standard questionnaires, and no dropouts during follow-up.

The limitations of this study are its open-label nature and short study duration of eight weeks looking for weight changes. A longer duration of study would have helped in extensively analyzing the effects of acetazolamide on weight. Acetazolamide was given at a lower dose in this study compared to the maximum dose of 2000 mg to minimize side effects, drop outs and due to ethical issues as it is the first study done for this indication. The dose of the antipsychotic drugs was decided by the treating clinician in both groups. Family history, diet, and exercises were not controlled in both groups.

Further studies can look at a larger sample size with a longer study duration to assess the potential benefits of acetazolamide on weight. Acetazolamide has not increased psychosis hence has the potential to be a more suitable candidate for this purpose.

CONCLUSION

There was a non-significant reduction in the weight, body mass index, abdominal circumference, and brief psychiatric rating scale scores in patients treated with acetazolamide. Further randomized long-term studies with higher dosages are needed for acetazolamide to be considered as a candidate for the prevention of weight gain with antipsychotics.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Vishwajit L Nimgaonkar is the Principal Investigator of a study titled – ”A randomized controlled trial of Acetazolamide for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia” funded by the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help received from all staff members of the Department of Psychiatry at Yenepoya Medical College, Mangalore.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ganguli R. Weight gain associated with antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psy. 1999;60:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poulin M-J, Chaput J-P, Simard V, Vincent P, Bernier J, Gauthier Y, et al. Management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain:Prospective naturalistic study of the effectiveness of a supervised exercise programme. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:980–9. doi: 10.1080/00048670701689428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneiderhan ME, Marvin R. Is acetazolamide similar to topiramate for reversal of antipsychotic-induced weight gain?Am J Ther. 2007;14:581–4. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31813e65b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parasrampuria J. Acetazolamide. Brittain HG, editor. Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients. Academic Press. 1993:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takagi S, Watanabe Y, Imaoka T, Sakata M, Watanabe M. Treatment of psychogenic polydipsia with acetazolamide:A report of 5 cases. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34:5–7. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e318205070b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maayan L, Correll CU. Management of antipsychotic-related weight gain. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:1175–200. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karunakaran KB, Chaparala S, Ganapathiraju MK. Potentially repurposable drugs for schizophrenia identified from its interactome. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48307-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panicker MJ, Kakunje A, Nimgaonkar VL, Deshpande S, Bhatia T, Sathyanath S. A pilot open label study of oral acetazolamide for sodium valproate associated weight gain in bipolar affective disorder. Arch Mental Health. 2021 doi:10.4103/amh.amh_61_21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kakunje A, Prabhu A, Priya Es S, Karkal R, Pookoth RK, Pd R. Acetazolamide for antipsychotic-associated weight gain in Schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;38:652–3. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale:Applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4:28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deberdt W, Winokur A, Cavazzoni PA, Trzaskoma QN, Carlson CD, Bymaster FP, et al. Amantadine for weight gain associated with olanzapine treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham KA, Gu H, Lieberman JA, Harp JB, Perkins DO. Double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of amantadine for weight loss in subjects who gained weight with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1744–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baptista T, Rangel N, Fernández V, Carrizo E, El Fakih Y, Uzcátegui E, et al. Metformin as an adjunctive treatment to control body weight and metabolic dysfunction during olanzapine administration:A multicentric, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baptista T, Uzcátegui E, Rangel N, El Fakih Y, Galeazzi T, Beaulieu S, et al. Metformin plus sibutramine for olanzapine-associated weight gain and metabolic dysfunction in schizophrenia:A 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2008;159:250–3. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein DJ, Cottingham EM, Sorter M, Barton BA, Morrison JA. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of metformin treatment of weight gain associated with initiation of atypical antipsychotic therapy in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2072–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Tezcan E, Ustundag B. Nizatidine treatment and its relationship with leptin levels in patients with olanzapine-induced weight gain. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:457–61. doi: 10.1002/hup.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy Chengappa K, Kupfer DJ, Parepally H, John V, Basu R, Buttenfield J, et al. A placebo-controlled, random-assignment, parallel-group pilot study of adjunctive topiramate for patients with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:609–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dayabandara M, Hanwella R, Ratnatunga S, Seneviratne S, Suraweera C, de Silva VA. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain:Management strategies and impact on treatment adherence. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2231–41. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S113099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiden PJ, Mackell JA, McDonnell DD. Obesity as a risk factor for antipsychotic noncompliance. Schizophr Res. 2004;66:51–7. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Silva VA, Dayabandara M, Wijesundara H, Henegama T, Gunewardena H, Suraweera C, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain in a South Asian population with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder:A double blind, randomized, placebo controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:1255–61. doi: 10.1177/0269881115613519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverstone T, Goodall E. Centrally acting anorectic drugs:A clinical perspective. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55:211S–4S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.1.211s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conley RR, Mahmoud R. A randomized double-blind study of risperidone and olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:765–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen ML, Pirzada MH, Shapiro MA. Zonisamide for weight loss in adolescents. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2013;18:311–4. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-18.4.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleischhacker WW, Heikkinen ME, Olié JP, Landsberg W, Dewaele P, McQuade RD, et al. Effects of adjunctive treatment with aripiprazole on body weight and clinical efficacy in schizophrenia patients treated with clozapine:A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:1115–25. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Assunção SS, Ruschel SI, Rosa LD, Campos JA, Alves MJ, Bracco OL, et al. Weight gain management in patients with schizophrenia during treatment with olanzapine in association with nizatidine. Braz J Psychiatry. 2006;28:270–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharan S, Dupuis A, Hébert D, Levin AV. The effect of oral acetazolamide on weight gain in children. Can J Ophthalmol. 2010;45:41–5. doi: 10.3129/i09-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue H, Hazama H, Hamazoe K, Ichikawa M, Omura F, Fukuma E, et al. Antipsychotic and prophylactic effects of acetazolamide (Diamox) on atypical psychosis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1984;38:425–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1984.tb00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacks W, Esser AH, Feitel B, Abbott K. Acetazolamide and thiamine:An ancillary therapy for chronic mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:279–88. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]