ABSTRACT

Background:

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has radically transformed workplaces, bearing an adverse impact on the mental health of employees.

Aim:

The current study attempts to gain an understanding of the mental health of employees while working from home (WFH) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Setting and Design:

The research followed a mixed-methods design and was conducted across two phases, with participants divided into two subgroups – the WFH subgroup (currently engaging in WFH) and the not working from home (NWFH) subgroup (unable to engage in vocational tasks due to the pandemic).

Materials and Methods:

The first phase employed quantitative standardized measures of workplace well-being, work and social adjustment, and quality of mental health across 187 participants. The second phase involved in-depth interviews of 31 participants selected from the previous phase, to understand the factors impacting mental health.

Results:

Strong correlations were recorded between the mental health of an individual and work-related constructs such as workplace well-being and work and social adjustment. The study revealed that participants rated themselves as being significantly more stressed and less productive during the pandemic. Thematic analysis identified the stressors (factors that negatively impact mental health) and enhancers (factors that enhance mental health). Fourteen stressors and 12 enhancers were identified for the WFH group, while five stressors and three enhancers were identified for the NWFH group.

Conclusions:

The results of the study indicate a significant relationship between the mental health of employees and work-related experiences through the pandemic. Further research on the stressors and enhancers identified through the study can pave the way for effective interventions to promote employee mental health.

Keywords: COVID-19, effective WFH practices, facilitators, remote workforce, stressors, work from home

In the light of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the workplace has been drastically altered, with organizations adopting diverse measures to assure the continuity of business. The foundation of most of these measures stands on the practice of “working from home” (WFH). Although WFH has been well established such that various roles across industries can be performed in such a set-up,[1] COVID-19 has forced various industries across the world to switch to remote working in a short period with limited access to resources. This urgent shift is bridled with challenges to both the organization and the employees. When these wide-ranging changes occur suddenly, without adequate time to prepare oneself mentally or materially, the potential sources for stressors are vast and can be presumed to have an impact on the employee’s functioning at work. On the contrary, certain aspects of WFH have proven to be beneficial, as highlighted in previous non-COVID era studies. WFH comes with greater flexibility at work and related self-reported productivity, and increased job satisfaction, saving energy, time, and costs, all of which are viewed positively by employees.[2]

The current study attempts to explore the state of mental health of employees engaged in WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic. It explores the correlation between workplace well-being, work and social adjustment, and scores on Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The relationship between age and scores on PHQ-9 too is discussed. The correlation between perceived productivity, perceived stress, and scores on PHQ-9, work and social adjustment, and workplace well-being is explored. The study explores these levels between WFH and not working from home (NWFH) groups. Further, the levels of perceived stress and productivity before and after the pandemic are compared. The study also seeks to delineate the role of organizational involvement in the given scenario. In order to better understand the employees who are engaged in WFH, their experiences have been contrasted with those who are unable to engage in their job tasks during the COVID-19 pandemic, referred to as individuals who are NWFH. The study also attempts to understand the stressors and enhancers impacting employees who are WFH through in-depth personal interviews. The phenomenon of WFH has also been looked at through the lens of well-being at the workplace, social adjustment, and mental well-being, across industrial, hierarchical, and gender boundaries. The study further attempts to understand trends across industrial sectors, hierarchical positions within an organization, and also between genders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research design

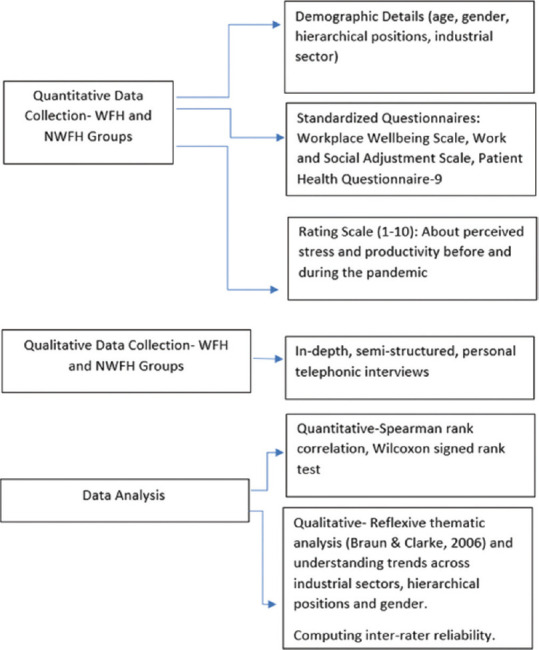

This research followed a mixed-method design involving two phases. The first was the quantitative phase that involved the administration of standardized questionnaires, demographic information forms, and survey forms to participants. The second phase was qualitative and involved in-depth, semi-structured personal interviews. The conceptual framework of the research design is elaborated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study design

Sample

The first phase of the study collected 187 responses of 109 males and 78 females, using purposive and snowball sampling. Participants’ age ranged from 20 to 77 years. The second phase of the study included 31 participants – with nine females and 22 males. Sampling was done using the theoretical sampling method.

Data collection and analysis

The first phase involved the administration of a questionnaire via an online form including a combination of standardized scales and a self-developed, non-standardized survey form. The standardized scales used were the Workplace Well-being Scale,[3] Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS),[4] and PHQ-9.[5] The survey form collected demographic information as well as data on the perceived levels of productivity and stress before and during the pandemic, on a sliding scale of 10. The quantitative data were subjected to correlational analysis, as well as comparison of means. Shapiro–Wilk test of normality was used to understand data distribution. To understand how the levels of workplace well-being, work satisfaction, organizational respect for the employees, work and social adjustment, and levels of mental well-being are related to each other, Spearman’s rank order correlation was used. IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 was used for analysis.

The second phase involved data collection through in-depth, semi-structured personal interviews with different interview schedules for WFH and NWFH samples. The interview questions designed were reviewed by experts, and mock interviews were conducted for training the interviewers. Personal telephonic interviews were conducted and audio recorded. These were transcribed and subjected to manual thematic analysis through reflexive method of Braun and Clarke’s[6] model. The researchers familiarized themselves with the data, generated initial codes, searched for themes, reviewed them, and finally defined and named the themes.[6] Three raters calculated the concordance values to establish inter-rater reliability. A comparative analysis was conducted based on four factors – WSAS and PHQ-9 scores to understand potential work-related determinants of these scores.

Ethical considerations

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Institutional Review Board at CHRIST (deemed to be university), Bangalore. Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

RESULTS

The following section details the key quantitative and qualitative results of the study.

Quantitative analysis

The data was not normally distributed, leading to the selection of non-parametric tests. The results showed strong positive correlations between all the measures. The only exception for a lack of correlation is the relation between the measures of organizational respect and work and social adjustment. Similar trends were observed in the WFH and NWFH samples. It is to be noted that the WSAS and the PHQ-9, which were used to measure work and social adjustment and mental health, respectively, were scored negatively (i.e., a higher score indicated lower adjustment and poorer mental health), leading to negative signs in the correlations, although the correlations themselves remained positive [Table 1].

Table 1.

Results of Spearman’s rank order correlation for the full sample

| Variables | Workplace well-being | Work satisfaction | Organizational respect | Work and social adjustment | Mental health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace well-being | - | - | - | - | - |

| Work satisfaction | 0.981* | - | - | - | - |

| Organizational respect | 0.963* | 0.900* | - | - | - |

| Work and social adjustment | −0.167* | −0.178* | −0.139 | - | - |

| Mental health | −0.277* | −0.297* | −0.239* | 0.424* | - |

*Indicates a correlation that is significant at the 0.01 level

The variable of mental health was also found to have a positive correlation with the participants’ age at −0.264 (at the 0.01 level). A similar trend was also found for the WFH and NWFH samples.

The participants were asked to rate their perceived levels of stress and productivity before and during the pandemic on a sliding scale of 1 through 10, as a part of the survey form. In the WFH sample, the levels of productivity and stress during the pandemic were found to strongly correlate with the levels of workplace well-being, work satisfaction, organizational respect, work and social adjustment, as well as mental health. With regard to the levels of stress, as the levels of stress decrease, the workplace well-being, work satisfaction, and organizational respect for the employee increase and the levels of work and social adjustment and quality of mental health decrease. Meanwhile, as the levels of workplace well-being, work satisfaction, and organizational respect for the employee increase, so do the levels of productivity, and the levels of work and social adjustment and quality of mental health decrease [Table 2].

Table 2.

Results of Spearman’s rank order correlation for levels of stress and productivity for the full sample

| Variables | Workplace well-being | Work satisfaction | Organizational respect | Work and social adjustment | Mental health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels of productivity during the pandemic | 0.458* | 0.460* | 0.415* | −0.280* | −0.236* |

| Levels of stress during the pandemic | −0.262* | −0.280* | −0.227* | 0.223* | 0.366* |

*Indicates a correlation that is significant at the 0.01 level

It was also found that the mean levels of productivity and stress before and during the pandemic differed significantly as per the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test. The levels of productivity were significantly higher before the pandemic, while the levels of stress were significantly greater during the pandemic [Table 3].

Table 3.

Results of Wilcoxon signed-ranks test for the levels of stress and productivity before/during pandemic

| Measure | Test statistic | Standardized test statistic | Mean before the pandemic | Mean during the pandemic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | ||||

| Levels of productivity | 2709.000 | −3.051 | 7.27 | 7.11 |

| Levels of stress | 6086.000 | 5.516 | 4.75 | 5.73 |

| WFH sample | ||||

| Levels of productivity | 1989.000 | −2.004 | 7.77 | 7.38 |

| Levels of stress | 3923.000 | 5.384 | 4.87 | 5.83 |

| NWFH sample | ||||

| Levels of productivity | 55.000 | −2.731 | 7.48 | 5.77 |

| Levels of stress | 229.000 | 1.372 | 4.12 | 5.25 |

NWFH=not working from home, WFH=working from home

Qualitative analysis

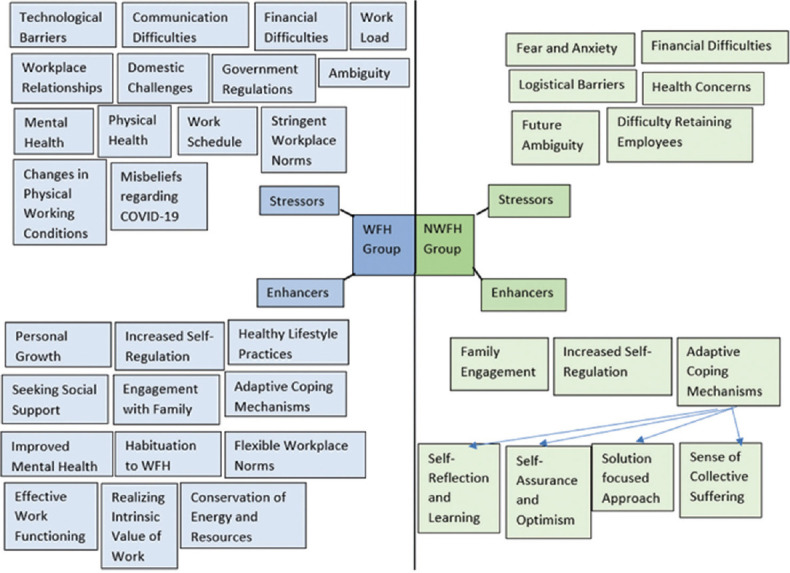

Qualitative thematic analysis was conducted, which resulted in domains focusing on the work-related factors affecting mental health and stress, separately for the WFH and NWFH samples. For the WFH sample, a total of 46 subthemes were identified under the domain of “stressors” and were grouped into 42 themes. Under the domain of “enhancers,” a total of 42 subthemes were obtained and grouped under 12 themes. The level of concordance for the subthemes derived from the WFH sample was found to be 0.907 (167/184), indicative of a high level of inter-rater reliability. For the NWFH sample, five themes were identified under stressors and three themes were identified under enhancers. The level of concordance was found to be 0.89 (26/29), again indicating a high degree of inter-rater reliability. A comparison across the participants from the WFH and NWFH groups was conducted based on the levels of “work and social adjustment” and “quality of mental health” [Figure 2 and Table 4].

Figure 2.

Thematic network

Table 4.

Work-related factors impacting mental health: Themes obtained through qualitative analysis

| Stressors | Enhancers |

|---|---|

| WFH sample | |

| Technological barriers | Personal growth |

| Communication | Effective work functioning |

| Workplace relationships | Realization of intrinsic value of work |

| Ambiguity | Increased self-regulation |

| Financial difficulties | Flexibility of workplace norms |

| Adverse impact on mental health | Healthy lifestyle practices |

| Physical health | Seeking social support |

| Work schedule | Engagement with family |

| Workload | Conservation of energy and resources |

| Change in physical working conditions | Improved mental health |

| Domestic challenges | Adaptive coping mechanisms |

| Governmental regulations | Habituation to WFH |

| Stringent workplace norms | |

| Misbeliefs regarding COVID-19 | |

| NWFH sample | |

| Fear and anxiety due to ambiguity about future | Engagement with family |

| Difficulty retaining employees | Increased self-regulation |

| Financial difficulties | Adaptive coping mechanisms |

| Inability to engage in work tasks due to logistical barriers | |

| Health concerns while returning to work |

COVID-19=coronavirus disease 2019, NWFH=not working from home, WFH=working from home

The geographically dispersed participants in the WFH group faced extensive issues in communication – literature[7] suggests that this may be due to the dearth in understanding non-verbal contextual cues. This not only impeded their ability to work, but also negatively impacted their workplace relations; a comment by a participant on the change – ”No informal conversation. It’s just about work” captures the qualitative shift in the nature of relations. This impediment led to a perception of greater workload and productivity as participants reported requiring more time and efforts to complete tasks – ”Working has become a time-consuming process.” This was further exacerbated by the irregular work schedule and blatant disregard for the personal time by their co-workers and employees, leading to decreased personal time and work–life imbalance, which research suggests as precursors for greater stress and fatigue.[8] As Williams et al.[9] show, stable scheduling predicts productivity, which may, in turn, decrease the stress levels.

The aforementioned factors along with technological and domestic challenges, limited resources, and ambiguity surrounding the pandemic cumulatively lead to a negative impact on mental health. This is in alignment with the concerns about pitfalls in productivity in the WFH scenario during COVID[10] due to lack of everyday engagement. The experience of emotional toil is evident with the participants reporting feeling “angry,” “depressed,” “irritated,” “disconnected,” and “stressed,” accompanied by feelings of loneliness and isolation – ”There’s no one around me.” Most participants also reported ill effects on their physical health due to sedentary lifestyles.

Lower levels of work and social adjustment were noted for the participants who reported difficulties in communication, feelings of helplessness, increased workload, and perception of disregard for personal time. In terms of quality of mental health, lower scores were found among those who expressed an inability to communicate because of barriers in completion of tasks, lack of clarity of instructions, and difficulty in highlighting individual efforts in the WFH scenario.

The work-related factors which reduced stress, leading to a positive impact on mental health, included devoting time to personal and professional growth through learning, enhancing relevant skills, and engaging in self-reflection and introspection, leading to positive experiences, which cause “increased self-awareness,” as noted by a participant. Participants who practiced greater self-regulation by asserting time boundaries, self-management, and self-motivation, further aided by organizational support through norms based on employee-centered work flexibility reported feeling highly productive and maintaining work–life balance – ”I get independence, space, work on my own time,” in concurrence with the literature on employee-centered work norms.[11] Deriving intrinsic value from their professional lives further fostered this sense of work satisfaction. Focusing on intrinsic meaning and the need for transcendental goals has been shown to lead to such results.[12] Participants who employed adaptive coping strategies such as a solution-focused approach to the problems presented by the pandemic experienced better mental health and positive emotional states – ”How you respond at the end of the day is your individual strength.” Such optimism and resilience have been shown to positively impact mental health, as seen in a survey on China-based executives.[13] Smooth communication, the ability to adapt workplace norms around virtual interactions, and building wider professional networks were found to enhance the quality of mental health, as they may have helped gain a sense of clarity, which has been shown to predict better work functioning.[14] Building this support system and further engaging with the personal and professional social networks including family, friends, and colleagues nurtured a sense of “facing the collective struggle,” which was perceived as a strength by the participants.

It was noted that participants who sought optimistic outlooks as well as those who had better experiences at work had higher levels of adjustment. Further, components such as seeking social support and the perception of relief from social engagements were prevalent among participants who had a higher quality of mental health.

In the NWFH group, participants relayed qualitatively different issues surrounding fears regarding financial and job security due to the economic crisis, health concerns, and employee retainment, which have been shown[15] to lower efficiency. These factors were common to participants with lower levels of work and social adjustment, especially in the aspects of “ability to work” and “home management.” Although the participants faced qualitatively different challenges from the WFH group, parallels can be drawn regarding the various healthy practices adopted to deal with personal challenges – engaging in self-reflection and learning, self-regulation through personal discipline and coping strategies with an optimistic and resilient outlook, and a solution-focused orientation to problem-solving.

When it came to levels of work and social adjustment and the quality of mental health, similar trends were noted as their counterparts in the previous group – participants who showed self-discipline and self-reflection had higher levels of adjustment and better quality of mental health.

DISCUSSION

The current study attempted to understand the state of mental health of the workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. The quantitative findings suggested that there were strong correlations between the mental health of an individual (as indicated by the scores on the PHQ-9) and work-related constructs such as workplace well-being as well as work and social adjustment.

Times of uncertainty in the workplace have been repeatedly shown to bear an adverse impact on the physical and mental health of employees.[16] This relationship has also been true inversely – with greater psychological capital protecting from negative work experiences.[17] This was found to be true in light of the qualitative findings which suggested that individuals who reported being optimistic and hopeful did have higher levels of adjustment of mental health, while the contrary was true for those who were anxious about the ambiguities of the future.

With regard to an individual’s age and their quality of mental health, select literature[18] on minority populations has reported that the quality of mental health does increase with age, as the current findings suggest. Some studies have also found similar relations between age and constructs closely related to mental health, such as dispositional optimism[18] and resilience.[19] However, there are also contradictory reports which suggest that constructs like quality of life decreases[20] and anxiety increases[21] with age. Hence, further study is warranted to understand the mediating and moderating factors at play in the relationship between mental health and chronological age.

The study also revealed that participants rated themselves as being significantly more stressed and less productive during the pandemic. The qualitative findings lend insight into the causes for the stress and its impact on mental health, identifying various factors and consequences of stress, which happen to vary for individuals who engage in WFH and those who do not. Further, certain aspects that may act as protective factors in mitigating stress and retaining a positive state of mental health were also identified and found to be similar for the two groups.

The study reveals deep insights into the state of mental health of individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby paving the way for creation of effective interventions to promote mental health.

Limitations

The sample of the study was limited in size, and the sampling technique used was non-random. Equal representation of gender, managerial roles, or sectors was not found. Equal representation of those WFH and NWFH was not found either.

Future directions

While the current study is an exploratory effort in understanding the phenomenon, further quantitative and qualitative studies are needed to gain a more detailed understanding. Targeted interventions for gender, industries, and hierarchical positions need to be devised, in order to enhance the facilitators and overcome the influence of the stressors. The devised interventions must further be evaluated.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The project would not be possible without the consistent dedication of many individuals who formed the very backbone of the project. The research project owes a lot to the research operations team, which aided collection of data for the study. The team was coordinated by Ms. Phibu Jose at CHRIST Consulting. The team included Sathwik Agarwal, Aditya Pratap Verma, Mansha Mannanul Haque, and Mohit Taneja, who facilitated the process of quantitative data collection. The team also included Mariaet Wilson, Archana Thomas, and Leah Arun, who facilitated the collection of qualitative data. A note of thanks must also be put on record for Vandhana Nandakumar and Divya Verma, who transcribed the qualitative data that was collected.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roy S. Will work from home be the new normal for India?Economic Times. 2020. [[Last acessed on 2020 Jun 30]]. Available from:https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/sme-sector/will-work-from-home-be-the-new-normal-for-india/articleshow/75592738.cms?from=mdr .

- 2.Abrams Z. The future of remote work. [[Last accessed on 2022 Aug 05]];Monitor on Psychology. 2019 50 Available from:http://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/10/cover-remote-work.html . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker GB, Hyett MP. Measurement of well-being in the workplace. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:394–7. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31821cd3b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mundt J, Marks IM, Shear MK, Griest JM. The work and social adjustment scale:A simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:551–5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramton C. The Mutual Knowledge Problem and Its Consequences for Dispersed Collaboration. Organization Science. 2001;12:346–71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golden L. The effects of working time on productivity and firm performance:A research synthesis paper. Ilo.org. 2012. [[Last accessed 2020 Sep 29]]. Available from:http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@travail/documents/publication/wcms_1√7.pdf .

- 9.Williams JC, Lambert SJ, Kesavan S. Stable scheduling increases productivity and sales:The stable scheduling study. Chapel Hill, NC: Kenan-Flagler Business School; 2018. [[Last accessed on 2020 Sep 29]]. Available from:https://worklifelaw.org/publications/Stable-Scheduling-Study-Report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorlick A. The productivity pitfalls of working from home in the age of COVID-19. Stanford News. 2020. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 04].]. Available from:https://news.stanford.edu/2020/03/30/productivity-pitfalls-working-home-age-covid-19/

- 11.Van der Meulen D. Does remote working really work? RSM Discov Manag Knowl. 2017;29:20–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey C, Madden A. What Makes Work Meaningful —Or Meaningless. MIT Sloan Management Review. 2016. [[Last accessed on 2020 Sep 29].]. Available fr om:https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/what-makes-work-meaningful-or-meaningless/

- 13.Pan L, Yang B, Yu T, Zhang H. Re-energizing through the epidemic:Stories from China. McKinsey &Company. 2020. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 07]]. Available from:https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/asia-pacific/re-energizing-through-the-epidemic-stories-from-china .

- 14.Darling A, Dannels D. Practicing engineers talk about the importance of talk:A report on the role of oral communication in the workplace. Commun Educ. 2003;52:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frith B, Lochmann M. How HR can help employees with financial troubles. Hrmagazine.co.uk. 2016. [[Last accessed on 2020 Sep 29]]. Available from:https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/article-details/how-hr-can-help-employees-with-financial-troubles .

- 16.Pollard TM. Changes in mental well-being, blood pressure and total cholesterol levels during workplace reorganization:The impact of uncertainty. Work Stress. 2001;15:14–28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spence Laschinger H, Fida R. New nurses burnout and workplace wellbeing:The influence of authentic leadership and psychological capital. Burn Res. 2014;1:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredriksen-Goldsen K, Kim H, Shiu C, Goldsen J, Emlet C. Successful aging among LGBT older adults:Physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. Gerontologist. 2014;55:154–68. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeste D, Savla G, Thompson W, Vahia I, Glorioso D, Martin A, et al. Association between older age and more successful aging:Critical role of resilience and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:188–96. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampogna F, Chren M, Melchi C, Pasquini P, Tabolli S, Abeni D. Age, gender, quality of life and psychological distress in patients hospitalized with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:325–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Himmelfarb S, Murrell S. The prevalence and correlates of anxiety symptoms in older adults. J Psychol. 1984;116:159–67. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1984.9923632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]