ABSTRACT

Background:

High prevalence (more than 80%) rates of tobacco smoking have been found both in, opioid-dependent subjects and among opioid-dependent subjects on opioid substitution treatment (OST) with buprenorphine or methadone.

Aim:

We aimed to explore the efficacy of combined nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and individual counseling (IC) when compared to NRT alone in subjects on OST with buprenorphine.

Methods:

This study was carried out in a tertiary medical care center. It was an open-label randomized clinical trial. A total of 57 buprenorphine maintained smokers were recruited and randomized into two groups. They were assigned nicotine gum for 4 weeks plus either (1) a baseline IC session, and a second IC session after 1 week, or (2) simple advice to quit. In the first group, 31 subjects received NRT with IC and in the second group, 26 subjects received NRT plus simple advice to quit. The primary outcomes of this study were seven days point prevalence abstinence, biochemically confirmed by carbon monoxide (CO) breath analyzer, and reduction in smoking (mean no. of cigarettes or bidis/day). The smoking behavior during the 4 weeks follow-up period was assessed by the timeline follow-back (TLFB) method and confirmed by the CO breath analyzer.

Results:

The group of subjects who received NRT with IC showed higher rates of smoking cessation at the end of treatment (51%) as compared to the NRT and simple advice group where smoking cessation rates were around 8% (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

A multi-component approach (pharmacotherapy and counseling) enhances treatment outcomes and enhances rates of abstinence from smoking.

Keywords: Buprenorphine maintenance, individual counseling, nicotine replacement therapy, smoking cessation

Smoking kills nearly 6 million people worldwide each year.[1] If current trends continue, tobacco-related deaths will increase to more than 8 million a year by 2030 and 80% of those deaths will occur in developing countries like India.[2] Thus, the promotion of smoking cessation will need to be a priority for policymakers in developing countries. The cigarette smoking rate among the general adult population in the US is 14% and in India is 10.7% (99.5 million).[3,4] The problem of smoking is about 4–10 times more in substance use disorder treatment settings where rates of tobacco use are in the range of 85–100%.[5-8]

About 0.70% of the Indian population (approximately 7.7 million individuals) are estimated to need help with their opioid use problems.[9] High rates of tobacco smoking have been documented both in, opioid-dependent patients and among opioid-dependent patients on opioid substitution therapy (OST) with buprenorphine or methadone where the prevalence of tobacco smoking is reported to be in the range of 73%–94%.[10-14] Additionally, 40–50% of these patients are heavy smokers, i.e., about 20 cigarettes per day.[15] Studies in patients on OST with methadone found that 70%–80% of patients were either somewhat or very interested in quitting and 68%–75% of patients had tried to quit at least once in their lives.[15-17] Ten-year mortality rate of opioid-dependent smokers is four-fold greater than that of opioid-dependent non-smokers.[18-20]

Evidence-based approaches to treat smoking cessation involve the provision of both medications and counseling, which have both been proved effective. First-line pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation is nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (gum, patch, lozenge, inhaler, and spray), bupropion, and varenicline. Combining medications with counseling provides the best chance for establishing long-term smoking abstinence.[21]

Various studies have been done on the effectiveness of smoking cessation intervention in opioid-dependent patients on agonist maintenance treatment worldwide. The overall effectiveness of various treatment modalities in this special population was ranging from 0% to 31% at the end of treatment and 0% to 11% on long-term follow-up, with the combined treatment approach showing higher rates of smoking cessation.[14,22]

Given the significant rates of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality in long-term opioid users, finding effective interventions in stabilized maintenance patients is essential.

Hence, we conducted this study to explore the efficacy of combined NRT and counseling when compared to NRT alone in patients on OST with buprenorphine. There are no previous Indian studies to date that test the efficacy of smoking cessation intervention in this population.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Setting, participants, and study design

This open-label randomized clinical trial was conducted in the outpatient department of a tertiary medical care center in North India. The sample was collected from August 2014 to July 2015. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. To recruit the study subjects, opioid-dependent subjects registered at the center were approached and recruited according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The informed consent for participation in the study was taken.

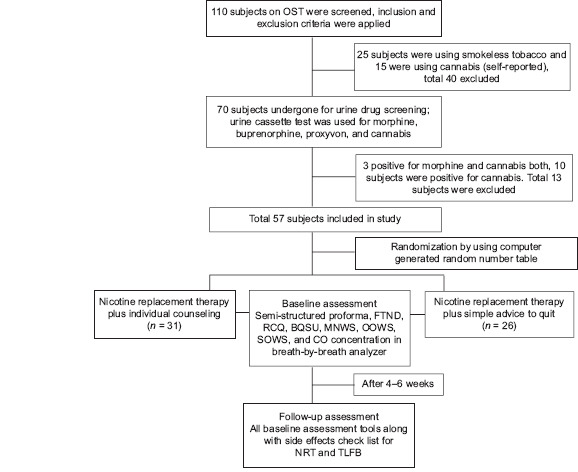

A total of 110 opioid-dependent subjects on OST with buprenorphine were screened. Finally, a total of 57 male subjects were randomized into two groups using a computerized random numbers table. The first group comprised those subjects who received NRT plus individual counseling sessions (NRT+IC) (n = 31) and the second group comprised those subjects who received NRT plus simple advice to quit smoking (NRT+SA) (n = 26). The pill count technique was used to ensure compliance with NRT [Flow Chart 1].

Flow Chart 1.

Summary of the study methodology

Inclusion criteria

Male subjects, age range 18–60 years, opioid-dependent subjects maintained on buprenorphine/buprenorphine-naloxone combination for ≥12 weeks, following up regularly with more than 80% attendance in a month as ascertained by pharmacy dispensing records, smoking ≥10 cigarettes/day for the past year, meeting International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 criteria for nicotine dependence, currently (last 3 months) not on any tobacco cessation therapy, and those who provided informed consent were included in this study.

Exclusion criteria

Those patients who were current (last 1 month) users of smokeless tobacco, having dependence on drugs other than opioids and nicotine, with co-morbid psychiatric illness, accelerated hypertension, post-myocardial infarction period (2 weeks), cardiac arrhythmia, unstable angina, hypersensitivity to NRT, and subjects refusing informed consent were excluded from the study.

Assessment

The assessments of recruited subjects were done at two time points, first at baseline and second 4 weeks after the baseline interventions.

Baseline assessment

The following instruments were used in the baseline assessment:

Semi-structured proforma: This comprised of socio-demographic details like subject’s name, age, gender, religion, occupation, monthly income, marital status, education, contact address and phone number, drug use history, registration in agonist maintenance treatment, details of treatment received, and tobacco use characteristics like type of smoking, age of onset of smoking, bidis/cigarettes use per day, etc.

Fagerstrom Test For Nicotine Dependence (FTND) for smokers

Readiness to change questionnaire (RCQ)

Brief Questionnaire on Smoking Urges (BQSU)

Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS)

Objective and subjective opioid withdrawal scale (OOWS and SOWS).

Biochemical tests used in this study at baseline

Carbon monoxide (CO) breath analyzer.

Urine cassette test for morphine, buprenorphine, proxyvon, and cannabis.

A follow-up assessment was done after 4 weeks of interventions. Besides the instruments used at baseline, two more instruments were used (1) a side effect checklist for NRT and (2) timeline follow-back (TLFB).

Intervention provided in the study

The screening of subjects was done by various investigators while randomization and intervention were provided by only one investigator.

NRT

NRT was provided in the form of nicotine gums (2 mg) to all the participants (n = 57) based on a standard dosing schedule. NRT in the form of gum was chosen as the gum was supplied free of cost to the center. Dosing schedule: For patients who were smoking 1–24 cigarettes/bidis, they should be given up to 16 pieces/day of 2 mg of nicotine gum for 4 weeks, and for those who were smoking more than 24 cigarettes/bidis, the dose should be double. Nicotine gum was dispensed on a weekly basis, a pill count technique was used to ensure compliance, and TLFB was used.

Individual counseling (IC)[21]

The NRT+IC (n = 31) group was provided with 60 min of IC in two sessions by the primary investigator who was initially trained for the same, under the consultant psychologist of the same center where the study was conducted.

The first session was given at baseline assessment. The duration of the first session was 20 min during which the main focus was on motivation enhancement, discussed under the following points with the patient:

Exploring beliefs related to tobacco use.

Willingness to quit.

Exploring and providing basic information related to the harms of tobacco use and the benefits of quitting.

The second session has been given after 1 week. The duration of this session was 40 min and the major focus was on skills training and relapse prevention, which were discussed under the following points with the patient:

Eliciting problems and barriers to quit

Alternatives to overcome problems and barriers to quit

Managing craving and withdrawal

High-risk situations

Coping skills

Managing lapse.

Simple advice to quit tobacco (SA)[21]

NRT+SA (n = 26) group was given simple advice (less than 3 min) to quit tobacco. It was provided in the form of verbal instruction to stop smoking with added information about the harmful effect of smoking. It was less than 3 min. It was provided only one time at the time of baseline assessment.

Outcome measures

Seven days point prevalence abstinence, biochemically confirmed by CO breath analyzer (<10 ppm), and reduction in smoking (mean no. of cigarettes or bidis/day) were used as outcome parameters in this study.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics percentages and measures of central tendency were calculated and data were assessed for normal distribution. The qualitative analysis between the groups was done using Chi-square tests. The quantitative analysis between the groups was done by using the independent sample “t” test. The quantitative analysis within the group was done by using paired samples “t” test P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. An intention-to-treat approach was used, with missing individuals presumed to have continued or resumed smoking. The data analysis was done using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 20 version statistical software suite developed by IBM corporation New York, USA and was released in 2011.[23]

RESULTS

Baseline parameters

All the recruited subjects in both groups were male, most subjects were Hindu, mean age of 42 years [42.1 (9.5) in NRT+IC group and 42.5 (10) in NRT+SA group], married, educated till middle standard (up to 8th grade), and currently employed [Table 1]. The mean age of initiation of tobacco use in both groups suggested early age of onset of tobacco use: 14 (1) years in NRT+IC group and 14.6 (1.5) years in NRT+SA group. In the NRT+IC group, 2 (6.5%) subjects were smoking cigarettes and 29 (93.5%) were smoking bidis while in the NRT+SA group, 1 (3.8%) subject was smoking a cigarette and 25 (96.2%) subjects were smoking bidi. Most of the subjects were chronic smokers [28 (10) years in NRT+IC group and 28 (9.5) years in NRT+SA group] with a high habit size of tobacco use and FTND scores [8.7 (1.2) in NRT+IC group and 9.2 (0.1) in NRT+SA group] suggestive of very high severity of nicotine dependence. Both the groups were comparable at baseline on socio-demographic and tobacco use parameters except for the numbers of bidi/cigarettes used per day and the subjects in NRT+SA group were using a significantly higher number of bidi/cigarette per day with a mean of 39 (20.5) than the subjects in NRT+IC group 28.6 (12). The mean dose of buprenorphine [12 (3) mg in NRT+IC group and 13 (2) mg in NRT+SA group] and the duration of buprenorphine treatment [38 (32) months in NRT+IC group and 2 (38) months in NRT+SA group] were similar across two groups.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population

| Socio-demographic parameter | NRT + IC (N=31) (%) | NRT + SA (N=26) (%) | Total (%) | Chi square | Df | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religion | ||||||

| Hindu | 23 (74.2) | 20 (76.9) | 43 (75.4) | 0.05 | 1 | 0.81 |

| Other religion | 8 (25.8) | 6 (23.1) | 14 (24.6) | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married | 6 (19.4) | 5 (19.2) | 11 (19.3) | 0 | 1 | 0.99 |

| Married | 25 (80.6) | 21 (80.8) | 46 (80.7) | |||

| Type of family | ||||||

| Joint family | 13 (41.9) | 11 (42.3) | 24 (42.1) | 0.001 | 1 | 0.97 |

| Other | 18 (58.1) | 15 (57.7) | 33 (57.9) | |||

| Educational status | ||||||

| Up to middle | 22 (71) | 15 (57.7) | 37 (64.9) | 1.09 | 1 | 0.30 |

| Above | 9 (29) | 11 (42.3) | 20 (35.1) | |||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Full time employment | 21 (67.7) | 22 (84.6) | 43 (75.4) | 2.17 | 1 | 1.40 |

| Others | 10 (32.3) | 4 (15.4) | 14 (24.6) |

Subjects in both groups were comparable in FTND, MNWS, OOWS, SOWS scores, and concentration of CO in exhaled air [Table 2]. The required mean dose of nicotine gum in the subjects of the first group was 15.94 (3.5) mg while in the second group was 18.62 (1.9) mg (P = 0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline clinical parameters between the two groups (Independent sample t-test)

| Clinical parameter | Group | Mean (SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total duration of tobacco use | NRT+IC | 27.96 (10) | 0.18 |

| NRT+SA | 27.88 (9.5) | ||

| No. of bidi/cigarette per day | NRT+IC (N=31) | 28.58 (12.1) | 0.03 |

| NRT+SA (N=26) | 38.81 (20.5) | ||

| FTND | NRT+IC (N=31) | 8.71 (1.2) | 0.08 |

| NRT+SA (N=26) | 9.23 (0.1) | ||

| BQSU | NRT+IC (N=31) | 61.00 (10.9) | 0.04 |

| NRT+SA (N=26) | 65.81 (5.9) | ||

| MNWS | NRT+IC (N=31) | 14.39 (3.7) | 0.24 |

| NRT+SA (N=26) | 15.62 (4.1) | ||

| OOWS | NRT+IC (N=31) | 0 | |

| NRT+SA (N=26) | 0 | ||

| SOWS | NRT+IC (N=31) | 0.97 (1.0) | 0.12 |

| NRT+SA (N=26) | 1.38 (1.0) | ||

| CO (ppm) | NRT+IC (N=31) | 23.32 (5.5) | 0.35 |

| NRT+SA (N=26) | 24.73 (5.7) |

Follow-up results

The post-intervention follow-up assessment was done 4 weeks after the baseline assessment. Subjects in both groups were compliant with NRT as ascertained by pill counts. 70% of subjects in NRT+IC and 80% in NRT+SA group were available for follow-up assessment. The rate of attrition was not significantly different between groups. In NRT+IC group, nine were lost to follow-up, and one subject reported side effects due to the use of nicotine gum in the form of nausea, vomiting, and hiccoughs and he withdrew from the study. The rest of the eight subjects could not be traced. In NRT+SA group, five subjects were lost to follow-up and could not be traced.

The mean dose of nicotine gum in the subjects of NRT+IC group was 16 (3.5) mg while in NRT+SA group was 18.6 (1.9) mg. The difference in the mean dose of NRT in both groups was statistically significant (P = 0.001).

The large and statistically significant within-group reductions in smoking from baseline to follow-up in the subjects of both groups were demonstrated with corresponding reductions in CO in expired air. This reduction was not significantly different between the two groups [mean reduction in no. of bidi/cigarette smoked per day in NRT+IC group was 20.2 (17.2) while in NRT+SA group was 26 (19.7)] suggesting that provision of NRT to both groups greatly assisted in smoking reduction. There was a significant decrease in measures of nicotine dependence on various scales like FTND, BQSU, and MNWS (from baseline to follow-up) in within-group analysis. This reduction was not significantly different between the two groups. However, at the end of treatment, in NRT+IC group significantly higher (51%) rates of complete abstinence from smoking were demonstrated as compared to NRT+SA group (8%). This abstinence was biochemically confirmed by CO levels in expired air [Tables 3 and 4].

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical parameters at follow-up between the two groups

| Mean (SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of bidi/cigarettes per day | ||

| NRT+IC | 8.35 (11.7) | 0.21 |

| NRT+SA | 12.77 (14.9) | |

| FTND | ||

| NRT+IC | 3.16 (3.9) | 0.14 |

| NRT+SA | 4.46 (2.8) | |

| BQSU | ||

| NRT+IC | 29.61 (23.3) | 0.08 |

| NRT+SA | 38.65 (14.6) | |

| MNWS | ||

| NRT+IC | 6.06 (6.3) | 0.15 |

| NRT+SA | 8.19 (4.9) | |

| OOWS | ||

| NRT+IC | 0 | |

| NRT+SA | 0 | |

| SOWS | ||

| NRT+IC | 0.90 (1.0) | 0.12 |

| NRT+SA | 1.31 (1.0) | |

| CO (ppm) | ||

| NRT+IC | 11.10 (8.5) | 0.04 |

| NRT+SA | 15.15 (5.5) |

Independent sample “t” test

Table 4.

Changes (Baseline-follow-up) in clinical parameters within-group and comparison of changes between the two groups

| Group | Mean (SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Derived bidi/cigarettes | NRT+IC | 20.22 (17.2) | 0.24 |

| NRT+SA | 26.04 (19.7) | ||

| Derived FTND | NRT+IC | 5.55 (4.0) | 0.40 |

| NRT+SA | 4.77 (2.8) | ||

| Derived BQSU | NRT+IC | 31.39 (23.7) | 0.43 |

| NRT+SA | 27.15 (15.9) | ||

| Derived MNWS | NRT+IC | 8.32 (6.7) | 0.58 |

| NRT+SA | 7.42 (5.2) | ||

| Derived OOWS | NRT+IC | 0 | - |

| NRT+SA | 0 | ||

| Derived SOWS | NRT+IC | 0.06 (0.3) | 0.89 |

| NRT+SA | 0.07 (0.4) | ||

| Derived CO | NRT+IC | 12.23 (9.1) | 0.19 |

| NRT+SA | 9.58 (5.6) |

Independent sample “t” test

DISCUSSION

Opioid-dependent smokers who are on OST are uniquely positioned to receive smoking cessation interventions due to their continued close contact with treatment providers.

The mean age of onset of smoking in NRT+IC group was 14 (1.1) years and in NRT+SA group was 14.6 (1.5) years. This finding is similar to other previous studies where the mean age of onset of smoking tobacco was 16.3 (5.1) and 14.1 (2.9).[24,25] This is in variance with the findings of smoking in the general population, where the mean age of onset of smoking was 20.5 (20) years and 17.9 years, which shows a later age of onset of tobacco smoking.[4,26] Earlier age of onset leads to severe patterns of dependence and progression to other drugs of abuse as in the population under study.[27,28]

At baseline, in NRT+IC group, the mean number of bidi/cigarette used per day was 28.6 (12.1) and in NRT+SA group was 38.8 (20.5) which is very high when compared to estimates in the general population, giving a national average of 11.6 bidi/cigarette per day and a mean of 14 (11.5) bidi/cigarette per day in another study.[4,26] The higher number of smoking bidi/cigarettes in this population is in concordance with previous studies where participants reported an average of smoking 19–27 cigarettes/day.[24,25,29,30] Corresponding to the higher quantity of bidi/cigarette use, most of the subjects had severe nicotine dependence on the FTND scale. This is in concordance with findings in the previous studies where subjects also had severe nicotine dependency on the FTND scale.[24,25,29-31] Higher rates of tobacco use are known in opioid-dependent patients due to a complex interaction between nicotine and the endogenous opioid system, with opioids increasing tobacco smoking and smoking enhancing the pleasurable effects of opioids.[20,32]

Overall, about 75% of subjects were adherent to treatment and were available for follow-up. These findings are in concordance with the previous studies in which the follow-up rate was about 77% at the end of treatment.[24,30] Attrition due to side effects was minimal as only one subject reported significant side effects of nicotine gum (nausea, vomiting, and hiccoughs) as the reason for stopping the medication and dropping out.

Intervention for smoking cessation in both groups was provided by NRT in the form of nicotine gum. In the NRT+IC group, IC of 60 min duration was provided in two sessions in addition to NRT. The required mean dose of nicotine gum in subjects of NRT+IC group was 16 (3.5) mg while in NRT+SA group was 18.6 (1.9) mg. The difference in the required mean dose of NRT in both groups was statistically significant (P = 0.001). Hence, subjects in NRT+SA group required higher dose of nicotine gum, which corresponds to the fact that they had a statistically higher quantity of bidi/cigarette use as compared to NRT+IC group. Subjects in both groups were compliant with NRT as ascertained by pill counts. The primary outcome measure in this study was seven days point prevalence of smoking abstinence.

The group of subjects who received NRT and IC showed higher rates of smoking cessation at end of treatment (51%) as compared to the NRT and simple advice group where smoking cessation rates were around 8%. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001). This shows that NRT plus IC was significantly more effective in smoking cessation as compared to NRT with simple advice in the population under study. Previous studies in this population have shown lower rates of abstinence when compared to our study. Overall, smoking cessation rates in this special population, at the end of treatment ranged from 0% to 27%.[24,29,30,33,34] Thus the population in this study achieved more robust abstinence rates (51%) on NRT plus individual counseling. There may be various reasons for this. This study population was stabilized on OST and regular follow-up (more than 80% attendance) for a considerably long duration of more than 3 years. In NRT+IC group, the mean duration of OST was 38.5 (32.7) months, and in NRT+SA group, it was 41.8 (38.2) months. Further, the score on OOWS was zero in the subjects of both the groups and the score on SOWS was 1 (1) and 1.3 (1) in the NRT+IC and NRT+SA groups, respectively. This shows that no significant opioid withdrawal signs and symptoms were present in these subjects, which may have interfered with smoking cessation outcomes. Additionally, the recruited population has no associated psychiatric co-morbidities but previous studies have also included those subjects who have or had a history of psychiatric co-morbidities like major depression, anxiety disorder, ADHD, or schizophrenia.[29,30] Studies found that those smokers who have psychiatric co-morbidities in substance use treatment programs have lesser smoking cessation rates than those who do not have co-morbid psychiatric disorders.[35,36] This may explain the higher smoking cessation rate in this current study as compared to lower smoking cessation rates in previous studies in this population.

Some of the substantial intergroup difference in the rates of abstinence may be attributed to the fact that the self-reported number of bidi/cigarette used per day in NRT+IC group differed significantly at baseline and was lesser [28.6 (12.1)] than NRT+SA group where bidi/cigarette use was higher [38.8 (20.5)]. Also, the score on BQSU was significantly lesser in NRT+IC group 61 (11) than in NRT+SA group 65.8 (6). This suggests that the amount of smoking and smoking urges played a role in smoking abstinence resulting in greater abstinence in NRT+IC group than in NRT+SA group. This is in line with the findings of previous studies, where a lesser amount of smoking and lower smoking urges are associated with more likelihood of smoking abstinence.[29-31]

Large and statistically significant reductions in smoking in the subjects of both the groups, who completed their follow-up, were demonstrated in this study. The subjective report of reduction in smoking was biochemically confirmed by the significant reduction in CO levels in both groups from baseline. These findings confirm to previous studies where smoking cessation interventions were associated with a significant reduction (but not to abstinence criteria) in the average number of cigarettes smoked per day and expired CO from baseline.[10,24,29] Similar to our study, most studies did not report statistically significant differences in reduction in smoking between groups. These findings imply that NRT and simple advice were successful in reducing the number of bidi/cigarettes smoked in both groups of our study but the provision of IC greatly assisted in achieving total abstinence from smoking.

Strength and limitation

The major strength of this study is obtaining longitudinal data and carrying out analysis for assessing, the rate of smoking cessation and reduction in smoking in the tertiary clinical setting. The present study could not identify potential predictors for complete abstinence as the sample size is small and regression analysis would have led to imprecise estimates of parameters (regression co-efficient and standard error). No blinding was done in this study.

CONCLUSION

In this study, significant reductions in smoking were demonstrated with NRT in both groups. The provision of IC greatly enhanced the outcomes and statistically significant difference in point prevalence abstinence rates from smoking in NRT+IC group as compared to NRT+SA group. These findings were biochemically confirmed by breath CO monitoring. This was the first trial of smoking cessation in this population in India and the results are very encouraging and suggest that the provision of NRT is useful in this population. A multi-component approach (pharmacotherapy and behavior counseling) enhanced treatment outcomes and rates of abstinence from smoking.

Future directions

Further studies are needed to determine whether gains in smoking reduction and abstinence extend beyond the end of treatment. Future studies should be done on a larger scale with robust methodologies incorporating a larger sample size and follow-up for a longer time period. In addition to NRT, the efficacy of other first-line treatments for smoking cessation like bupropion and varenicline in addition to behavioral counseling should also be explored in this population. After adequate efficacy studies, an upscale of this intervention may be planned for OST programs in India.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was given by the “Institute ethics committee for post graduate research, All India Institute Of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India” (Ref no. IESC/T-266/21/21.06.2014).

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Special mention must be given to pharmacy staff, laboratory staff, and nursing staff of NDDTC, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, who made sure that the environment of center was peaceful and conducive to work on. A special thanks to Mr. Satpal for his constant support in assessment of laboratory parameters.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2009: Implementing smoke-free environments. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011: Warning about the Dangers of Tobacco. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2017. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1225–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global adult Tobacco Survey India (GATS-India) – 2016-17 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lien L, Bolstad I, Bramness JG. Smoking among inpatients in treatment for substance use disorders:Prevalence and effect on mental health and quality of life. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu H, Wang F, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J, Zhang H. Alcohol and nicotine codependence-associated DNA methylation changes in promoter regions of addiction-related genes. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41816. doi: 10.1038/srep41816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders:Findings from the National Epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:162–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClure EA, Acquavita SP, Dunn KE, Stoller KB, Stitzer ML. Characterizing smoking, cessation services, and quit interest across outpatient substance abuse treatment modalities. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of social justice and empowerment government of India, magnitude of substance use in India, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ainscough TS, Brose LS, Strang J, McNeill A. Contingency management for tobacco smoking during opioid addiction treatment:A randomised pilot study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017467. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pajusco B, Chiamulera C, Quaglio G, Moro L, Casari R, Amen G, et al. Tobacco addiction and smoking status in heroin addicts under methadone vs. buprenorphine therapy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:932–42. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagano A, Gubner N, Le T, Guydish J. Cigarette smoking and quit attempts among Latinos in substance use disorder treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44:660–7. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1417417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahvi S, Richter K, Li X, Modali L, Arnsten J. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting in methadone maintenance patients. Addict Behav. 2006;31:2127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zirakzadeh A, Shuman C, Stauter E, Hays JT, Ebbert JO. Cigarette smoking in methadone maintained patients:An up-to-date review. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2013;6:77–84. doi: 10.2174/1874473711306010009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hser YI, Saxon AJ, Huang D, Hasson A, Thomas C, Hillhouse M, et al. Treatment retention among patients randomized to buprenorphine/naloxone compared to methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. 2014;109:79–87. doi: 10.1111/add.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cookson C, Strang J, Ratschen E, Sutherland G, Finch E, McNeill A. Smoking and its treatment in addiction services:Clients'and staff behaviour and attitudes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandal P, Jain R, Jhanjee S, Sreenivas V. Psychological barriers to tobacco cessation in Indian buprenorphine-naloxone maintained patients:A pilot study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:299. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.162944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veldhuizen S, Callaghan RC. Cause-specific mortality among people previously hospitalized with opioid-related conditions:A retrospective cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:620–4. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shadel WG, Stein MD, Anderson BJ, Herman DS, Bishop S, Lassor JA, et al. Correlates of motivation to quit smoking in methadone-maintained smokers enrolled in a smoking cessation trial. Addict Behav. 2005;30:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richter KP, Hamilton AK, Hall S, Catley D, Cox LS, Grobe J. Patterns of smoking and methadone dose in drug treatment patients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:144–53. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB. Treating tobacco use and dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. USDHHS. PHS. 2008;101:3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akerman SC, Brunette MF, Green AI, Goodman DJ, Blunt HB, Heil SH. Treating tobacco use disorder in pregnant women in medication-assisted treatment for an opioid use disorder:A systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;52:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein MD, Weinstock MC, Herman DS, Anderson BJ, Anthony JL, Niaura R. A smoking cessation intervention for the methadone maintained. Addiction. 2006;101:599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunn KE, Sigmon SC, Thomas CS, Heil SH, Higgins ST. Voucher based contingent reinforcement of smoking abstinence among methadone maintained patients:A pilot study. J Appl Behav Anal. 2008;41:527–38. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jindal SK, Aggarwal AN, Chaudhry K, Chhabra SK, D'Souza GA, Gupta D, et al. Tobacco smoking in India:Prevalence, quit-rates and respiratory morbidity. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Quintero C, de los Cobos JP, Hasin DS, Okuda M, Wang S, Grant BF, et al. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine:Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:120–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behrendt S, Wittchen HU, Höfler M, Lieb R, Beesdo K. Transitions from first substance use to substance use disorders in adolescence:Is early onset associated with a rapid escalation?Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid MS, Fallon B, Sonne S, Flammino F, Nunes EV, Jiang H, et al. Smoking cessation treatment in community-based substance abuse rehabilitation programs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;35:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooperman NA, Lu SE, Richter KP, Bernstein SL, Williams JM. Pilot study of a tailored smoking cessation intervention for individuals in treatment for opioid dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20:1152–6. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein MD, Anderson BJ, Niaura R. Smoking cessation patterns in methadone-maintained smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:421–8. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Custodio L, Malone S, Bardo MT, Turner JR. Nicotine and opioid co-dependence:Findings from bench research to clinical trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;134:104507. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richter KP, McCool RM, Catley D, Hall M, Ahluwalia JS. Dual pharmacotherapy and motivational interviewing for tobacco dependence among drug treatment patients. J Addict Dis. 2005;24:79–90. doi: 10.1300/j069v24n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okoli CT, Khara M, Procyshyn RM, Johnson JL, Barr AM, Greaves L. Smoking cessation interventions among individuals in methadone maintenance:A brief review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalman D, Morissette SB, George TP. Co-morbidity of smoking in patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2005;14:106–23. doi: 10.1080/10550490590924728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonne SC, Nunes EV, Jiang H, Tyson C, Rotrosen J, Reid MS. The relationship between depression and smoking cessation outcomes in treatment seeking substance abusers. Am J Addict. 2010;19:111–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]