Abstract

Aims:

To compare brief advice (BA), motivational interviewing (MI), rate reduction (RR), and combined MI and RR (MI + RR) to promote smoking cessation in smokers not ready to quit.

Design:

Randomized controlled trial with four parallel groups of smoking cessation intervention. Participants were randomly assigned 1:2:2:2 to receive one of the following interventions: BA (n = 128), MI (n = 258), RR (n = 257), and MI + RR (n = 260).

Setting:

The United States. All participant contact occurred over the telephone to be consistent with the typical quit line format.

Participants:

A total of 903 adult smokers. Participants had a mean age of 49 (SD = 13.3) years and were 28.9% male and 63.3% Caucasian.

Interventions:

The BA group received advice similar to typical smoking cessation quit lines. The MI group received advice using basic MI principles to elicit language that indicates behavioral change. The RR group received behavioral skills training and nicotine gum. The MI + RR group combined elements of MI and RR conditions. All interventions were six sessions.

Measurements:

The primary outcome measure was self-reported point prevalence at 12 months. The secondary outcome was self-reported prolonged abstinence at 12 months.

Findings:

Intention to treat (ITT) point prevalence at 12 months indicated that BA (10.9%) had significantly lower point prevalence rates than RR (27.2%, OR = 3.17, 1.69–5.94), and MI + RR (26.9%, OR = 3.16, 1.68–5.93). BA did not have a significantly lower point prevalence rate than MI (15.5%, OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 0.81–3.02).

Conclusions:

This randomized controlled trial provided evidence that rate reduction, which offers structured behavioral skills and nicotine gum, either alone or combined with motivational interviewing, is the most effective form of cessation intervention for smokers not ready to quit.

Keywords: Brief advice, motivational interviewing, nicotine gum, rate reduction, smokers not ready to quit, smoking cessation

INTRODUCTION

Despite significant reductions in smoking prevalence in the United States (US), cigarette smoking remains the single most important preventable cause of morbidity, mortality, and excess health care costs in the United States, causing ~480 000 premature deaths annually accounting for 33% of cancer deaths and costing $300 billion annually in medical and productivity costs [1]. The Surgeon General’s Smoking Cessation Report from 2020 indicates that all individuals benefit from quitting smoking, regardless of the length of time smoked, but that nicotine addiction is chronic and relapsing, making any quit attempt challenging to enact and maintain [2].

Smoking cessation programs are efficacious across a wide variety of settings (e.g. clinics, worksites, and the military) [3], populations (e.g. low income, minorities) [4, 5], and platforms (e.g. internet, quit lines, and media-based programs) [1, 3, 5, 6]. However, all these approaches have been tested with the 10% to 30% of smokers who are ready to make a serious quit attempt in the next 30 days [1, 3, 5, 6]. Although the majority of smokers want to quit smoking in the future [7], close to 90% indicate that they are not ready to make quit attempts in the next 30 days [8]. This leaves doubt about the effectiveness of existing smoking cessation programs for the majority of smokers not ready to quit (SNRTQ).

The current clinical practice guidelines for SNRTQ recommend motivational interviewing (MI) to encourage these smokers to consider quitting [9, 10]. Results from a Cochrane review demonstrated that MI was more effective for smoking cessation than brief advice (BA) or usual care (effect size = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.16–1.36), but this did not focus on SNRTQ [11]. If SNRTQ are ambivalent about change, it is clear that the strategies of MI are tailor made for this population. Another promising strategy for SNRTQ is rate reduction (RR), a skills-based cognitive behavioral and pharmacologic treatment that encourages deliberate reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked per day, typically with the use of nicotine replacement therapy. RR has considerable support as a smoking cessation treatment among those ready to quit [12], and may provide considerable structure to a SNRTQ population. Given the absence of preparation for a quit attempt in SNRTQ, it is likely that the structure of RR would be necessary for these individuals to engage in a quit attempt. Finally, given evidence that combined MI and skills based intervention show superior effects to either intervention alone [13], and given the likely necessity of a more intense intervention among SNRTQ, it is likely a combination of MI and RR would be advantageous in a population of smokers not yet ready to make a change.

Klemperer et al. [14] examined behavioral interventions in n = 560 smokers who were not ready to quit. This trial compared brief motivational, reduction, or usual care intervention groups in a four session, telephonically delivered, randomized design with point prevalence at 6 months as the primary outcome [14]. Results indicated that at 6 months (n = 355, 37% attrition), the conditions were not significantly different in terms of point prevalence abstinence rate (11% for motivational, 8% for reduction, and 5% for usual care). The 12-month follow up evidenced significant differences in point prevalence between groups, with the brief motivational group demonstrating significantly more abstinence than usual care (10% vs 4%, respectively), although this 12-month follow up had only 49% retention [14].

SNRTQ are an understudied population who may be amenable to engage in smoking cessation, although previous work clearly indicates attrition concern for this unmotivated population [14]. The goal of the current trial was to compare two potentially effective interventions in a population of SNRTQ: MI [9, 10] and RR [12]. This study sought to engage SNRTQ over the telephone to encourage participation [1, 3, 5, 6], enhance treatment engagement through incentives, and compare individual interventions with additive treatment by combining the elements of MI and RR in a combined treatment condition [15].

The Planning a Change Easily (PACE) study was comparative effectiveness trial of (i) BA, a standard of care condition in a time- and intensity-controlled format; (ii) MI, an interviewing style directed at developing motivation for change [13, 16, 17]; (iii) RR, an evidence-based skills-based intervention that included the provision of nicotine gum [18]; and (iv) a combination of MI and RR interventions (MI + RR) [15]. This design was essential to the evaluation of the independent and additive effects of MI and RR on abstinence rates. Based on a recent meta-analysis [19], the sample of this clinical trial (n = 903) was larger than the majority of clinical trials of cessation in SNRTQ, which range in size between n = 11 and n = 1728, allowing for sufficient power to compare different intervention modalities in the same trial. The primary outcome was point prevalence, and the secondary outcome was prolonged abstinence (duration of quit) at 12-month follow up.

Hypotheses

Based on previous research, it was hypothesized that RR or MI would have better point prevalence abstinence rates at 12 months compared to BA [20–23]. It was also hypothesized that when treatment components were combined (MI + RR), superior cessation over and above MI or RR alone would occur [13].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

This was a randomized controlled trial of MI, RR, and MI + RR interventions with BA serving as the control group. The University of Tennessee Health Science Center Institutional Review Board provided approval to conduct this study, and the trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT02905656).

Participants

Participants were 903 adults in the United States who smoked at least an average of five conventional tobacco cigarettes a day for the past year, were interested in quitting smoking someday, but not in the next 30 days, had access to a telephone, and understood the consent process in English.

Exclusion criteria included having a known contraindication, allergy, or hypersensitivity to nicotine gum; use of other behavioral or pharmacologic tobacco cessation programs in the past 30 days; current pregnancy or lactation, or plans to become pregnant in the next 12 months; a medical history of unstable angina, myocardial infarction within the past 3 months, cardiac dysrhythmia other than medication-controlled atrial fibrillation or paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, or medically uncontrolled or untreated hypertension, conditions that are contraindicated for the use of nicotine gum.

Procedure

All procedures took place over the telephone. Research staff were located at an academic medical setting in the southeastern United States. Recruitment included paper flyers and advertisements on Facebook. Potential participants called the study line or emailed the study team expressing interest. Participants were called and administered a screening visit over the telephone and completed the informed consent process electronically or via mailed paper form, depending on preference.

Randomization

Each consented participant was randomized to treatment group using a computerized block design with fixed blocks of seven randomly generated sequences. Participants were randomized (1:2:2:2 to BA [n = 128], MI [n = 258], RR [n = 257], and MI + RR [n = 260], respectively) to the four treatment groups by a concealed coding sheet of these sequences developed by the study statistician, and available only to the study interventionists once randomization was conducted. Specifically, the randomization group was concealed via black highlighting on an excel data sheet until the study interventionist removed it to identify the group assignment. Uneven randomization of participants to groups, with fewer participants randomized to BA than other conditions was enacted given the relative preponderance of research using BA [20], and the hypothesis that all other conditions would be superior in effectiveness as compared to low-intensity BA. Once the assignment was revealed, the study interventionist informed the participant of their group assignment and scheduled their six intervention sessions.

Retention included a t-shirt with the study name and acronym provided at enrollment, incentives for attended sessions ($20 Amazon gift card for each of six possible sessions, totaling $120), and another t-shirt mailed before the 12-month follow up.

Measures

Demographics

At baseline, participants reported on their age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, and educational achievement.

Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence

The Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) was collected at baseline to examine potential differences in nicotine dependence in groups before intervention [24].

Primary outcome: point prevalence

Seven-day point prevalence (i.e. 7 days without a cigarette, “not even a puff”) [25], was assessed through self-report via telephone interview at the 12-month follow up.

Secondary outcome: prolonged abstinence

Prolonged abstinence was assessed through self-report via telephone interview for a period of up to 12 months. Multiple assessments were conducted to reduce recall bias by the participant (assessments of quit date occurred at 2, 4, 6, and 12 months with a 2-week grace period around the cessation date) [25].

Intervention groups

Each intervention group (i.e. BA, MI, RR, and RR + MI) received three treatment sessions within the first 6 weeks of participation, followed by three booster sessions at 2, 4, and 6 months post randomization. Participants in all groups received the same amount of intervention time (~30 minutes per session). Toward the end of each session, interventionists asked participants if they were ready to set a quit date and specified that setting a quit date was not required. If participants reported abstinence at any phone call, the interventionists provided the same information as planned on each arm, but focused their efforts on relapse prevention.

BA group

The BA group served as the “usual care” group, with procedures similar to typical smoking cessation quit lines. Participants randomized to this condition received psychoeducation citing health consequences of smoking based on information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [10]. Booster sessions reviewed material. At any session, participants were provided with the phone number of the national tobacco quit line (1–800-QUITNOW) if they requested additional cessation resources. Despite serving as the comparator group, the BA group received the same duration of intervention as the other groups (~30 minutes per session for six sessions).

MI group

Basic MI principles were used for each call in the MI arm with the intention of eliciting language that indicates behavioral change using open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries. In these sessions, the counselor focused the discussion using the “5Rs” (relevance, risks, rewards, roadblocks, and repetition) to increase the participants’ motivation for change and eventual odds of cessation. If the participant wished to quit at any point during the sessions, the interventionist assisted in creating a participant-centered cessation plan, but no specific skills were provided in this condition. The booster sessions were a continuation of previous discussions.

RR

The RR intervention included behavioral skills to encourage reduction in smoking rate (e.g. breaking brand loyalty, self-monitoring of smoking, and disrupting automatic triggers). In addition, interventionists addressed appropriate use of 4 mg nicotine gum, provided at no cost to participants to address acute cravings. Nicotine gum was mailed to the participant starting at baseline and every 2 weeks at the participant’s request, ending at 26 weeks post baseline. Side effects were monitored by the study physician (C.W). No serious side effects observed were deemed related to the nicotine gum. At each RR session, participants were encouraged to reduce their smoking rates by 25% before the next session. The booster sessions assessed skill practice and reviewed appropriate use of nicotine gum.

MI + RR

MI + RR combined elements of MI and RR conditions. Participants in MI + RR received nicotine gum in the same way as participants in RR condition. Each session began with a discussion of motivation and confidence to change, followed by information on RR skills. Skills content was the same as in the RR condition but in an abbreviated format to ensure equal session length across groups. The booster sessions were a continuation of previous discussions and review of RR skills.

Interventionist training and treatment fidelity

Interventionists were required to have at least a master’s degree in a counseling-related field and were trained to ensure proper intervention delivery. Each interventionist was trained to deliver all the treatment arms to ensure that effectiveness in a particular group was not because of a particular interventionist’s characteristics. All interventionists met standard proficiency level before working with participants. Audio from all study sessions was recorded, and 10% of sessions were reviewed (463 sessions reviewed total) by four reviewers. All tapes were scored for content coverage (%). Treatment fidelity is reported in the Results. Interventionists received weekly clinical supervision from doctoral-level supervisors for feedback and further training when needed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS/STATv14.1. Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and proportions were generated overall and for intervention arms. Comparisons of baseline characteristics for those with complete versus missing outcome were carried out with the analysis of variance (ANOVA) or χ2 test.

The primary method of data analysis was an intention to treat (ITT) analysis of all 903 randomized participants. Those with missing data were conservatively assumed not abstinent (i.e. missing not at random). The secondary method of data analysis was an ITT with the assumption of missing at random using multiple imputations. The intervention condition BA was used as a comparative condition in all analyses given that it is the “standard of care.” To test the intervention effects compared to BA, a logistic regression model was applied, adjusting for demographics and baseline FTCD score. Twenty-Five imputations of the missing outcome values at the follow up with the FCS discriminant regression model were performed, that included demographic and baseline FTCD score. This was performed with SAS PROC MI under missing at random (MAR) assumption. Each imputed dataset was analyzed using the same logistic regression model as described above, and combined the parameter estimates and their standard errors with SAS PROC MIANYLIZE, to produce valid statistical inferences. All of the associations were considered significant at the α level of 0.05.

Power analysis

All power and sample size calculations were done with PASS12 [26] a priori. Power analyses were conducted for ITT and based on the primary outcome, point prevalence.

Power calculations were based on several studies that compare BA versus RR, MI, and MI + RR, which includes a meta-analysis that reports odds in the range of 2–2.6 for the mentioned treatments [12, 15, 20, 27]. Based on this research, RR and MI were expected to at least double the odds of the outcome compared to BA, and MI + RR to have an even larger, additive effect. Based on previous research, a 9% point prevalence rate in the BA group was assumed [12, 15, 20, 27]. Power calculations showed that group sample sizes of 240 in any of the active intervention arms and 120 in the control arm achieved 80% power to detect a difference in point prevalence abstinence rate of 10% or more. The proportion in RR, MI, and MI + RR was assumed to be 9% under the null hypothesis (no difference) and 19% under the alternative hypothesis, which is equivalent to an OR of 2.4. Earlier research showed the effects sizes comparing control to monotherapy (RR or MI alone) that were much larger than a doubling of effect size [15]. All of the effects potentially larger than 19% (perhaps additive effect of MI and RR) had power in excess of 80%, allowing the claim of those differences significant if they are truly observed. Test statistic used was a 2-sided χ2 test. The assumed significance level for all tests was 0.05.

RESULTS

CONSORT

Of 1185 individuals screened for the study, 147 were ineligible because of exclusions (see Fig. 1). Reasons for ineligibility included: not able to understand consent or speak English (n = 5), had not smoked 5 or more cigarettes per day for last 12 months (n = 20), never planning on quitting smoking (n = 18), planning to quit in the next 30 days (n = 38), not willing to use nicotine gum (n = 33), unstable heart condition (angina, cardiac dysrhythmia, or hypertension) (n = 25), and pregnancy (n = 8). Another 135 participants screened declined to participate in the study.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram

A total of 903 individuals were eligible and randomized. All of these 903 individuals were included in the ITT model.

Baseline

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The proportion of those with missing outcome data at the 12-month follow up (n = 148) was not significantly different between arms. Participants attended an average of 4.88 out of a possible six intervention sessions (81% adherence). Treatment adherence was significantly higher in BA than in RR (5.25 vs 4.71, t = 3.06, d.f. = 899, P = 0.010) and in BA than in MI + RR (5.25 vs 4.73, t = 3.14, d.f. = 899, P = 0.014). Treatment fidelity scores demonstrated significant differences on content completion scores (P = 0.0422), with the RR group demonstrating a lower average percent content coverage than the BA group (97.59 vs 99.25, respectively), although percent content coverage was high in both groups. For the MI and MI + RR groups, MI global scores were not significantly different, but the MI group demonstrated lower MI adherence than the MI + RR group (P = 0.0468; 98.63 vs 99.24, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Overall (N = 903) | BA (n = 128) | MI (n = 258) | RR (n = 257) | MI + RR (n = 260) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 49(13.3) | 47.9(13.6) | 50.3(12.5) | 48.3(13.2) | 49.1(13.8) |

| Gender, male | 28.9% | 27.3% | 29.5% | 31.1% | 26.9% |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian | 63.3% | 60.2% | 63.2% | 59.9% | 68.5% |

| African American | 32.0% | 34.4% | 32.2% | 35% | 27.7% |

| Other | 4.7% | 5.5% | 4.7% | 31% | 3.9% |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | 3.7% | 3.9% | 4.7% | 3.5% | 2.7% |

| Married/partnered | 24.4% | 28.1% | 24.0% | 26.4% | 24.6% |

| Education | |||||

| <HS | 14.8% | 20.5% | 16.3% | 13.2% | 11.9% |

| HS/GED | 36% | 35.4% | 33.3% | 38.9% | 36.2% |

| Some college | 38.7% | 34.7% | 39.9% | 38.5% | 39.6% |

| College or more | 10.5% | 9.5% | 10.5% | 9.3% | 12.3% |

| Baseline FTCD score | 5.8(2.1) | 5.5(2.1) | 6(1.9) | 5.6(2.1) | 5.9(2.3) |

| Treatment adherence average | 4.88 | 5.25 | 5.03 | 4.71 | 4.73 |

| Treatment adherence percent | 81.3 | 87.5 | 83.8 | 78.5 | 78.8 |

| Missing outcome data | 16.4 | 12.5 | 16.3 | 18.3 | 16.5 |

| Fidelity | Overall (N = 463 scored) | BA (n = 59) | MI (n = 146) | RR (n = 123) | MI + RR (n = 135) |

| Fidelity: content coverage | 98.30 | 99.25 | 98.78 | 97.59 | 98.01 |

| Fidelity: MI adherent | 98.93 | n/a | 98.63 | n/a | 99.24 |

| Fidelity: MI global score | 3.92 | n/a | 3.97 | n/a | 3.87 |

Note: Mean (SD) or %.

Abbreviations: BA, brief advice (comparison); FTCD, Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence; GED, graduate equivalency degree; HS, high school; MI, motivational interviewing; RR, rate reduction; RR + MI, motivational interviewing + rate reduction. Fidelity for MI adherence and MI global scores was not conducted on groups that did not use MI.

Comparison of characteristics by missing outcome status (Table 2 demonstrated a pattern that suggested MAR). However, loss at follow up was associated with male gender (P = 0.0025).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of characteristics by missing outcome status at the follow-up

| Complete (n = 755) | Missing (n = 148) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 49.3(13.1) | 47.7(13.8) | 0.1923 |

| Male | 26.9% | 39.2% | 0.0025 |

| Race | 0.4678 | ||

| Caucasian | 63.1% | 64.9% | |

| African American | 31.9% | 32.4% | |

| Other | 5% | 2.7% | |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | 3.4% | 4.7% | 0.4458 |

| Married/partnered | 25.7% | 17.6% | 0.0352 |

| Education | 0.8757 | ||

| <HS | 14.3% | 16.9% | |

| HS/GED | 36.1% | 35.8% | |

| Some college | 39% | 37.2% | |

| College or more | 10.6% | 10.1% | |

| Baseline FTCD score | 5.8(2.2) | 5.7(2) | 0.644 |

Note: Mean (SD) or %.

Abbreviations: FTCD, Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence; GED, graduate equivalency degree; HS, high school.

Treatment fidelity

Reliability was scored by two reviewers for 5% of the intervention sessions, and agreement was excellent among reviewers (κ = 92.5%). For the MI and MI + RR groups, MI adherence (%) and MI global score (range of 1 low to 5 high, with 3 being acceptable) were evaluated. Coverage of intervention content was very high overall (98.30% covered). For those in the MI and MI + RR groups, MI adherence was excellent (98.63% and 99.24%, respectively) and MI global scores were in the proficient (>3.5) range (3.97 and 3.87, respectively).

Nicotine gum use

Nicotine gum use is provided in Supporting information Table S1. Across groups, nicotine gum use in session 1 was lower than in sessions 2 to 5 because of the arrival of nicotine gum in the mail. Nicotine gum use between groups was significantly different, with lower use in the MI + RR groups in sessions 2–5 (F = 408.98, P = 0.031).

ITT analyses unadjusted

Table 3 shows the unadjusted estimates of abstinence by treatment arm.

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted estimates (% and 95% CI) of abstinence, overall and by arm, chi-square test with brief advice as the reference group

| Overall (N = 903) | BA (n = 128) | MI (n = 258) | RR (n = 257) | MI + RR (n = 260) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome, point prevalence abstinence | ||||||

| ITT MNAR | 21.5% (18.8, 24.2) | 10.9% (5.5, 16.3) | 15.5% (11.1, 19.9) | 27.2% (21.8, 32.7) | 26.9% (21.5, 32.3) | <0.0001 |

| ITT MAR | 26.1% (25.5, 26.7) | 12.8% (11.7, 13.9) | 18.6% (17.7, 19.6) | 33.9% (32.8, 35.1) | 32.3% (31.2, 33.4) | <0.0001 |

| Secondary outcome, prolonged abstinence | ||||||

| ITT MNAR | 18.8% (16.3, 21.4) | 9.4% (4.3, 14.4) | 13.9% (9.7, 18.2) | 24.1% (18.9, 29.4) | 23.1% (17.9, 28.2) | 0.0002 |

| ITT MAR | 22.8% (22.3, 23.4) | 11.2% (10.1, 12.3) | 16.9% (16.0, 17.8) | 29.9% (28.8, 31.0) | 27.5% (26.4, 28.6) | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: BA, brief advice (comparison); ITT MAR, intention to treat missing at random; ITT MNAR, intention to treat missing not at random; MI, motivational interviewing; RR, rate reduction; RR + MI, motivational interviewing + rate reduction.

Primary outcome: Point prevalence

ITT missing not at random (MNAR) assumption analyses of point prevalence at 12 months indicated that BA (10.9%) had the lowest point prevalence rates, followed by MI (15.5%), MI + RR (26.9%), and RR (27.2%). ITT MAR assumption analyses of point prevalence were similar with slightly higher point prevalence rates (12.8%, 18.6%, 32.3%, and 33.9% for BA, MI, MI + RR, and RR, respectively).

Secondary outcome: prolonged abstinence

ITT MNAR assumption analyses of prolonged abstinence at 12 months indicated that BA (9.4%) had the lowest point prevalence rates, followed by MI (13.9%), MI + RR (23.1%), and RR (24.1%). ITT MAR assumption analyses of prolonged abstinence were similar with slightly higher point prevalence rates (11.2%, 16.9%, 27.5%, and 29.9% for BA, MI, MI + RR, and RR, respectively).

ITT analyses adjusted (multiple imputations)

Table 4 presents the adjusted ORs for the primary and secondary outcomes comparing all other interventions to BA while controlling for all baseline measures. Results were remarkably similar for point prevalence and prolonged abstinence outcomes. Multivariable analysis confirmed univariate observations. RR and MI + RR intervention arms were associated with 2.5- to 3.5-fold increase in odds of abstinence compared to BA.

TABLE 4.

Adjusted ORs comparing interventions to BA

| MI vs BA | RR vs BA | MI + RR vs BA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aORa | 95%CI | P value | aOR | 95% CI | P value | aOR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Primary outcome point, prevalence abstinence | |||||||||

| ITT MNAR | 1.56 | 0.81, 3.02 | 0.1847 | 3.17* | 1.69*, 5.94* | 0.0003* | 3.16* | 1.68*, 5.93* | 0.0003* |

| ITT MAR | 1.68 | 0.86, 3.27 | 0.1298 | 3.75* | 1.98*, 7.12* | <0.0001* | 3.55* | 1.87*, 6.75* | 0.0001* |

| Secondary outcome, prolonged abstinence | |||||||||

| ITT MNAR | 1.56 | 0.77, 3.13 | 0.2143 | 3.09* | 1.59*, 6.02* | 0.0009* | 2.89* | 1.48*, 5.63* | 0.0019* |

| ITT MAR | 1.63 | 0.79, 3.36 | 0.1889 | 3.46* | 1.76*, 6.83* | 0.0004* | 3.04* | 1.53*, 6.04* | 0.0016* |

Abbreviations: BA, brief advice (comparison); ITT MAR, intention to treat missing at random; ITT MNAR, intention to treat missing not at random; MI, motivational interviewing; RR, rate reduction; RR + MI, motivational interviewing + rate reduction.

aOR, adjusted for age, gender, race, ethnicity, education and baseline FTCD score.

Significant P values.

MI by itself was not significantly different from BA, and MI added to RR did not augment cessation rates above and beyond RR. This indicates that the RR component of intervention by itself produces largest abstinence effects.

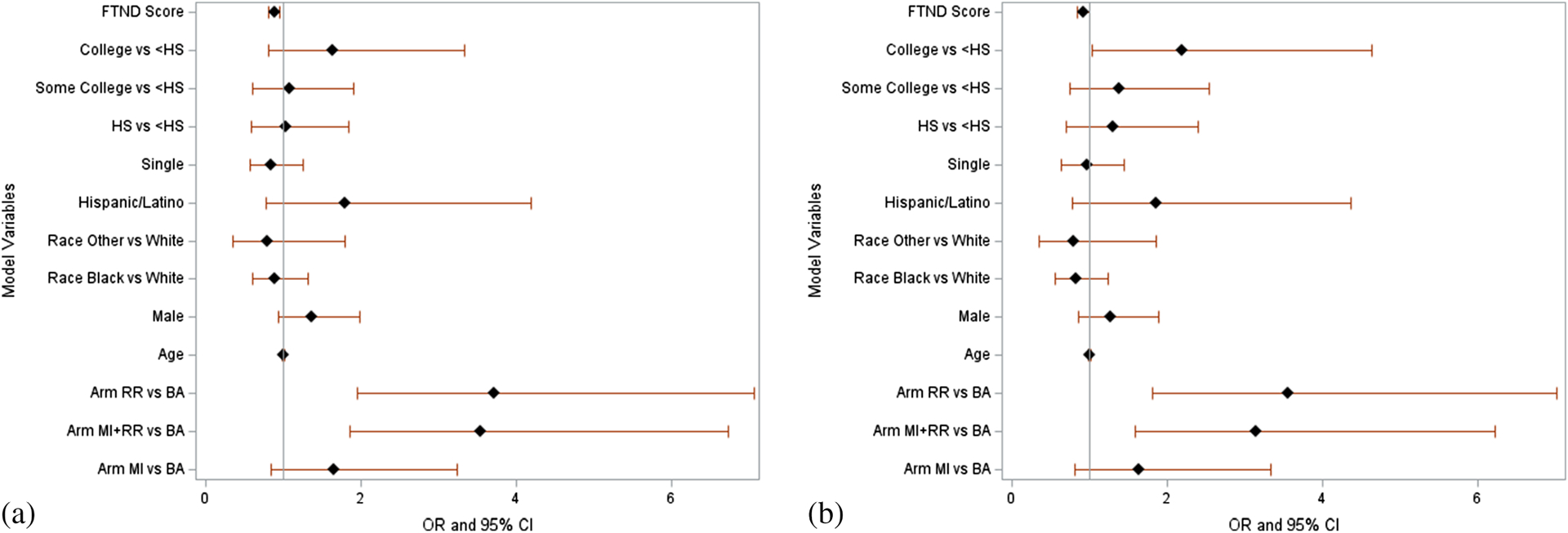

Figure 2 provides forest plots of multivariable logistic regression models for point prevalence (primary outcome) and prolonged abstinence (secondary outcome) for ITT analyses.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plots of ORs and 95% CIs from multivariable logistic regression models for point prevalence abstinence and prolonged abstinence, intention to treat analyses. (a) Point prevalence outcome intention to treat. (b) Prolonged abstinence outcome intention to treat. FTCD = Fagerstrom’s Test for Cigarette Dependence

DISCUSSION

PACE was a telephone-based, randomized controlled trial in the United States designed to compare the effectiveness of four cessation interventions exclusively in SNRTQ. The four intervention conditions were based on standard of care (i.e. BA) and evidence-based behavioral and pharmacological programs that have been effective in smoking reduction and cessation (i.e. MI, RR) [9, 10, 12, 14]. In addition, based on evidence that combined intervention can result in additive changes [15], a combined intervention condition was included (RR + MI). Interventions were executed in a rigorous manner, with extremely high content coverage fidelity rates across conditions (all >97%), and exceptional MI adherence and global scores in MI conditions, indicating strong methodology in a large and diverse sample. Advancing recent work in this area [14], retention for the 12-month outcome was 83.6%. Across all of our treatment groups, 12-month quit rates were slightly higher than those reported in previous studies [14], including BA (10.9% vs 5%), RR (27.2% vs 8%), and MI (15.5% vs 8%). Prior work did not include a combined intervention condition that can be used as a comparator.

Results indicated that although all conditions showed nontrivial abstinence rates at 12 months, only those conditions that included both behavioral and pharmacological strategies demonstrated significant improvement over BA. Similar to meta-analytic results [19], these findings suggest that the most effective strategy for SNRTQ appears to include a skills-based cognitive behavioral intervention that offers nicotine gum. Although a cognitive-behavioral intervention is considerably more intensive than BA [19, 20], requiring more training for those providing treatment, the near tripling of abstinence rates at 12 months appears to indicate that such training may be extremely useful to providers. Second, this trial suggests that MI, either alone or in addition to RR, did not result in a significantly enhanced treatment effect over BA, although analyses suggested a 50% to 60% increase in the odds of abstinence.

There are several possible reasons for the effectiveness of RR groups for SNRTQ. This skills-based intervention included nicotine gum, which may be necessary for some smokers who have strong cravings following reductions in nicotine. It is possible that nicotine gum accounted for some of the success in the RR (vs MI alone) groups. In addition, RR conditions provided considerable structure for a cessation attempt to individuals with quitting ambivalence, a feature not included in the BA or MI conditions. Such direction and problem-solving may be needed when individuals have not given quitting sufficient consideration. Regardless, RR implementation requires minimal training, and nicotine gum is over-the-counter, thereby lending important information to the disseminability of this intervention.

Surprisingly, the use of MI did not appear to significantly improve abstinence in this sample of SNRTQ, either alone or in combination with behavioral and pharmacological treatment. There are some potential reasons for this finding. First, it is possible that MI skills do promote motivation to change, but motivation alone is insufficient to markedly change an outcome of a complex cessation attempt, whereas skills and pharmacological treatment provide considerable structure to an individual who has not yet explored cessation methods. Second, it is possible that MI worked to promote cessation attempts, but these attempts did not result in abstinence. Examining quit attempts would elucidate possible ways that MI encourages change in SNRTQ. Finally, the preponderance of MI support comes from smokers ready to quit [9, 10], not SNRTQ, suggesting that MI is theoretically appropriate, but not as effective at producing long-term change in this population.

It is important to note that adherence to treatment was very high in this study, as was retention, perhaps as a result of the regular incentives provided, which even when not tied to a quit, can encourage attempts [28]. Although incentives for treatment are not likely in typical treatment practice, this study shows that a cost of $120 (or $20 per session) was associated with impressive treatment adherence rates in a population of smokers hesitant to make changes. Future exploration of incentive-based treatment retention should include a no-incentive condition to explore whether these gift cards significantly changed adherence.

It is also critical to note that although participants are classified as SNRTQ, this definition varies according to study and population. In this work, the inclusion of participants “willing to quit someday, but not in the next 30 days” implies that participants were willing, but not preparing to make a quit attempt. Studies of treatment resistant individuals (smokers never willing to quit) will likely observe much lower cessation rates. The dearth in research among those not ready to quit produces some variability in definition of this population, leading to issues in comparison across studies [20].

Limitations of this design include the absence of biochemical verification of abstinence at 12-month follow up because of lack of feasibility of this methodology. Honesty in self-report was encouraged throughout the study by indicating that incentives were provided regardless of quit status, and 12-month assessments were completed by an experienced research assistant who was blind to treatment condition and had no previous interaction with participants. All of these conditions have been found to increase accuracy on self-reported smoking status [29], and self-reported smoking in health survey samples has been found to be accurate against biochemical verification with a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 92.8% [30]. Further, if a quit was indicated, the interventionist further assessed quit date as an additional measure of response fidelity to identify any obvious falsification of results. Nonetheless, it is possible that demand characteristics may have led some to falsify their quit status, possibly in part because of perceived relation to incentives, or that participants accidentally disclosed group status to the blinded research assistant. However, these effects were unlikely to be differential across treatment groups.

Other limitations of this work included the uneven attrition of male participants for 12-month outcomes, and the preponderance of women in the study. It is well-known that women are more likely to participate in research [31], and males are more likely to drop out in research [32], however, it is not possible to know whether this increased attrition among males was a result of an unwillingness to report on outcomes because of failed abstinence. Analyses assuming non-abstinence were conducted for those with missing data at 12 months, but this is a coarse estimate of this possibility. Future research would do well to bolster retention efforts for males at long-term outcomes assessments. Further, there may have been some contamination between treatment groups given that interventionists were trained to deliver all four interventions, although extensive supervision and weekly recording review with interventionists was constructed to minimize this effect. Finally, this study was designed to examine existing forms of treatment for smoking cessation, but these methods are not consistent in their inclusion of nicotine gum. Because only RR groups included nicotine gum, we could not tease out effects of nicotine gum independent of the type of counseling. Future work may include more groups, or allow participants to self-select into nicotine gum use.

The PACE study was a comparative effectiveness trial of four active smoking cessation interventions for SNRTQ. The findings that interventions that included rate reduction skills significantly increased abstinence suggest that behavioral skills to reduce smoking supported by nicotine gum is an effective way to achieve long-term abstinence in this population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the staff in charge of managing discrete aspects of the study and providing participants with materials and interventions: Cyril Patra, Beverly Word, Robin Hardin, Susan Dalton, Janet Elam, Filoteia Popescu, John Boatner, Andrea Warren, and Dana Guerrero. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1R01CA193245-01A1). The National Institutes of Health had no involvement in the study design, collection, and analysis of data, interpretation of results, or writing of this report.

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: 1R01CA193245-01A1

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

All authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02905656.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Consequences of Smoking, Surgeon General fact sheet Atlanta. GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/tobacco/consequences-smoking-factsheet/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cahill K, Lancaster T. Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:1–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carson KV, Brinn MP, Peters M, Veale A, Esterman AJ, Smith BJ. Interventions for smoking cessation in indigenous populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas JS, Linder JA, Park ER, Gonzalez I, Rigotti NA, Klinger EV, et al. Proactive tobacco cessation outreach to smokers of low socioeconomic status: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(2):218–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matkin W, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Hartmann-Boyce J. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;5:1–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000–2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velicer WF, Fava JL, Prochaska JO, Abrams DB, Emmons KM, Pierce JP. Distribution of smokers by stage in three representative samples. Prev Med. 1995;24(4):401–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. 2008.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindson N, Thompson TP, Ferrey A, Lambert JD, Aveyard P. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:1–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ. Does smoking reduction increase future cessation and decrease disease risk? A qualitative review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(6):739–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai DT, Cahill K, Qin Y, Tang JL. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klemperer EM, Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Callas PW, Fingar JR. Motivational, reduction and usual care interventions for smokers who are not ready to quit: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2017; 112(1):146–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter MJ, Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Callas PW. Both smoking reduction with nicotine replacement therapy and motivational advice increase future cessation among smokers unmotivated to quit. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(3):371–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis MF, Shapiro D, Windsor R, Whalen P, Rhode R, Miller HS, et al. Motivational interviewing versus prescriptive advice for smokers who are not ready to quit. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(1): 129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catley D, Goggin K, Harris KJ, Richter KP, Williams K, Patten C, et al. A randomized trial of motivational interviewing: Cessation induction among smokers with low desire to quit. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(5): 573–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasgow RE, Gaglio B, Estabrooks PA, Marcus AC, Ritzwoller DP, Smith TL, et al. Long-term results of a smoking reduction program. Med Care. 2009;115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali A, Kaplan CM, Derefinko KJ, Klesges RC. Smoking cessation for smokers not ready to quit: Meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):253–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asfar T, Ebbert JO, Klesges RC, Relyea GE. Do smoking reduction interventions promote cessation in smokers not ready to quit? Addict Behav. 2011;36(7):764–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan SS, Leung DY, Abdullah AS, Wong VT, Hedley AJ, Lam TH. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking reduction plus nicotine replacement therapy intervention for smokers not willing to quit smoking. Addiction. 2011;106(6):1155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindson-Hawley N, Hartmann-Boyce J, Fanshawe TR, Begh R, Farley A, Lancaster T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:1–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:Cd005231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagerström K Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom test for cigarette dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):75–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piper ME, Bullen C, Krishnan-Sarin S, Rigotti NA, Steinberg ML, Streck JM, et al. Defining and measuring abstinence in clinical trials of smoking cessation interventions: An updated review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;22(7):1098–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hintze J. PSASS 12. NCSS, LLC: Kaysville, Utah; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ, Naud S. Do point prevalence and prolonged abstinence measures produce similar results in smoking cessation studies? A systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2010;12(7):756–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Notley C, Gentry S, Livingstone-Banks J, Bauld L, Perera R, Hartmann-Boyce J. Incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7(7):CD004307–CD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: A review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(7):1086–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryant J, Bonevski B, Paul C, Lecathelinais C. Assessing smoking status in disadvantaged populations: Is computer administered self report an accurate and acceptable measure? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(53):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labots G, Jones A, de Visser SJ, Rissmann R, Burggraaf J. Gender differences in clinical registration trials: Is there a real problem? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(4):700–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiers S, Oral E, Fontham ET, Peters ES, Mohler JL, Bensen JT, et al. Modelling attrition and nonparticipation in a longitudinal study of prostate cancer. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.