Abstract

As middle and high school students consume and create their own pornography or use it as a form of violence perpetration known as image-based sexual abuse, school staff struggle to find appropriate responses to these issues. As pornography use becomes more prevalent, and discourse on sexual violence more public, pornography education could become a tool for preventing sexual violence and promoting sexual health. In response, we explored the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of PopPorn, a 4-module pornography and IBSA professional development training program in a sample of staff who work for Midwestern public schools (i.e., schools providing free public education funded by tax dollars and maintained by local government). Results indicate that the majority of staff perceive student pornography use and IBSA perpetration to be critical problems that negatively impact school climate. Results also indicate that the PopPorn brief intervention increases staff knowledge of and efficacy in addressing pornography and IBSA-related problems and reduces harmful sexual double standard attitudes that have been linked to victim blaming in instances of sexual violence. This promising program adds to a growing number of media and pornography literacy interventions aimed at improving sexual violence prevention and response.

Keywords: pornography, school-based sex education, sexual harassment, sexting, media literacy

Introduction

As online pornography has become more widely available, it is unsurprising that adolescents are consuming pornography at higher rates today than in the past. Studies show that the average age of first exposure to pornography ranges from 11-17 years old (Herbenick et al., 2020; Peter & Valkenburg, 2016), which suggests that pornography education should occur in secondary schools (Crabee & Flood, 2021). In addition, there is growing evidence suggesting that adolescents who are at a higher risk for perpetrating sexual aggression and dating violence (Rostad et al., 2019; Wright et al., 2021) and engaging in condomless sex (Wright et al., 2018) regularly use pornography and view it as more realistic than adolescents who are at lower risk of perpetrating sexual violence. Moreover, the depiction of sexualized content on social media platforms such as Instagram and streaming platforms such as Netflix has become commonplace and is a significant player in youth socialization (Ward, 2016). This increase in sexualized media exposure is also occurring in a cultural context of the #MeToo reckoning, where a precipice was reached in terms of celebrity sex crimes and sexual harassment in the workplace, garnering new public discourse (Maas et al., 2018; PettyJohn et al., 2019). In response, school-based sexual health educators are attempting to determine how to educate adolescents on sexual violence, pornography, and sexualized popular culture.

Comprehensive sexuality education is becoming a more commonly recognized approach to prevent sexual violence. Indeed, research shows that sexual health promotion and violence prevention share many of the same antecedents and are implemented in a similar fashion in high schools and universities (Maas & Waterman, 2021). Schneider and Hirsh (2020) suggest that sequential, comprehensive sexuality education in the K-12 school system has potential to prevent the emergence of risk factors associated with SV perpetration by starting prevention early on in the life course. College students have identified pornography education as a common factor in sexual health promotion and violence prevention, with the timing of such education in secondary school (Goldstein, 2020). Despite consensus on the ubiquity of our sexualized culture and the need for education to navigate it, the feasibility of implementing developmentally appropriate pornography education in public schools remains highly contested among the public and prevention scientists.

Current Sexual Media Literacy Programming

Perhaps most troubling is that the adolescents who need the education to grapple with the sexual nature of popular culture or easy access to pornography likely know more about these phenomena than the adults hired to educate them. Consequently, when issues related to online pornography and social media arise at school, many of the staff who the adolescents could turn to are ignorant or naïve about the nature of these issues, let alone how to address them. Thus, there has been a call to provide school-based pornography education as school settings are a common one for pornography’s impact and a practical one for delivering high-quality content (Crabbe & Flood, 2021). In addition, warm, knowledgeable, and responsive staff can positively impact school environments by serving as a safe and consistent source for students to turn to if they are experiencing bullying, sexual harassment, or even sexual assault (Gruber & Fineran, 2016; Low et al., 2014). Given that many of the current staff in secondary schools did not have access to pornography via mobile devices and did not experience pressure to engage with peers around the clock on social media, it is unreasonable to expect staff to address these issues without adequate training.

Sexualized media literacy and even pornography-specific media literacy have been the most recent and appropriate response to the increase in adolescents’ access to pornography (Dawson et al., 2020; Scull et al., 2019). Pornography literacy is a derivative of media literacy. Media literacy efforts aim to increase consumer knowledge about the purpose of the media itself (e.g., profit, persuasion) and increasing skills for identifying messages within the medium (Jeong et al., 2012). Some emerging media literacy programs focus on educating parents to discuss sexuality and media with their children. For example, The Media Aware Parent program is a parent-based sexual media literacy program that does not appear to directly address pornography but has been shown to increase media literacy skills among parents and improve the quality of conversations with their children about sexual health (Scull et al., 2019), but not necessarily online sexual experiences. To understand what teens want to learn from a youth-focused pornography literacy class, one group of researchers employed a participatory action study with teens that generated eight core concepts that pornography literacy training should include: reducing shame of pornography engagement, discussing sexual consent, body and genital image, the realities of sex, pleasure and orgasm, physical safety and sex, the role of pornography as an educator, and the sexualization of LGBTQ+ people (Dawson et al., 2020). One of the few documented and evaluated pornography literacy courses for youth, “The Truth About Pornography” is a 5-session pornography literacy program. This promising program has been shown to increase pornography-related knowledge and change some potentially harmful and erroneous attitudes toward pornography (Rothman et al., 2018). However, it is unclear to what extent these programs address self-produced and distributed pornography or pornography on “tube-sites” or other platforms such as Snapchat that defy many of the theoretical principles of media literacy.

Sexualized Media and Sexual Violence

Given that ethically produced pornography is kept behind paywalls (Scott, 2016), pornography that teens have the easiest access to is the free content that is featured on pornography tube-sites. PornHub, for example, is a pornography tube-site where users can view pornography for fee or upload their own pornographic videos. At PornHub’s inception, many assumed it was primarily “amateur content” or homemade and consensual content (Ruberg, 2016); however, the website was recently found to have had millions of suspected videos of abuse and coercion (Cox, 2020). A recent study confirmed this when researchers found that 1 out of 8 titles of pornography videos on PornHub described sexual violence (Vera-Gray et al., 2021). Indeed, an increasing amount of nonconsensual pornography is being distributed through various online platforms that pornography literacy programming must address. For example, how can you teach teens that what they see online is unrealistic when those showcased were not paid and viewers like them uploaded the content? Indeed, as technology facilitates the ease of uploading and sharing videos, more amateur footage from webcams and smartphones is circulated than professionally produced and distributed content from adult film companies.

When these amateur nude images and sexual footage clips are shared without consent, it is considered Image-based Sexual Abuse (IBSA). IBSA is a relatively new umbrella term for various aggressive or abusive acts. One uses an image or video to harass, stalk, or humiliate the person depicted (DeKeseredy & Schwartz, 2016). Such images and videos are often shared widely (albeit without consent) by users of pornography tube-sites (Ruvalcaba & Eaton, 2019) or even secretly among location-based curated social media accounts and listserves known as “slutpages” (Henry & Flynn, 2019; Maas et al., 2021). However, the most common form of IBSA in secondary schools is nonconsensual sexting, where the act of sexting itself is coerced or the images are sent with consent but then nonconsensually distributed throughout the school (Madigan et al., 2018). Emerging research is showing that nonconsensual sexting perpetration is a marker of other risk factors and bullying perpetration (Valido et al., 2020). Whereas IBSA victimization is associated with depression, anxiety, and even suicidality (Bates, 2017; Ruvalcaba & Eaton, 2019). Therefore, pornography literacy efforts need to integrate with IBSA prevention efforts, expanding on the skill of determining what is realistic to expect in terms of bodies or sex acts, identifying what is legal/ethical, and understanding what normalizes sexual coercion.

Although pornography does showcase sexual violence and people perpetrate violence with pornography (IBSA), the association between pornography viewing and offline violence perpetration and victimization is inconsistent. For example, male adolescents exposed to violent pornography are more likely to be higher in sexual aggression (Wright et al., 2021) and are 2-3 times more likely to perpetrate sexual violence in romantic relationships (Rostad et al., 2019). For female college students, pornography use has been identified as a correlate of sexual violence victimization (de Heer et al., 2020). In contrast, in a representative sample of US adults, pornography users held more egalitarian views about women than those who did not use pornography (Kohut et al., 2016). These are some of the conflicting findings that make it difficult to cite pornography as an undisputed cause of violence perpetration or victimization. However, we can consider the possible effects of sexualized media through the lens of Sexual Scripting Theory (Simon & Gagnon, 2003). According to this theory, individuals learn how to engage in sexual behavior through observing messages (or sexual scripts) perpetuated within the media content we consume (Herbenick et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2018). Free, mainstream, heteronormative internet pornography that is the easiest for adolescents to access tends to portray sexual scripts of sexual aggression, degradation of women, and lack of sexual consent (Klaasen & Peter, 2015; Uhl et al., 2018; Vera-Gray et al., 2021). Thus, when adolescents consume pornography with these particular sexual scripts, they may unintentionally use such scripts to guide their own sexual expectations and decision making (Luder at al., 2011). As such, it is critical to include pornography in school-based sexual education and violence prevention and train staff on this new process of sexual socialization. If public school staff have some foundational knowledge of this phenomenon, they should be better able to respond to sexual violence, including IBSA, whether the perpetrator was inspired by pornography or not.

Student and Staff Training for Pornography and Image-based Sexual Abuse

Public school staff are under-prepared to address online sexual misconduct like watching pornography or perpetrating IBSA on school-supplied devices. Students have described negative experiences reporting in-person sexual harassment to public school staff, which ultimately deters them from help-seeking. For example, a survey conducted by Know Your IX, demonstrated that students experienced significant educational, financial, safety, and health issues after reporting sexual harassment (Nesbitt et al., 2021). When adolescents in the United Kingdom reported sexual harassment to teachers, they belittled students’ experiences and told them to “get used to it.” Students further described other forms of trivializing sexual harassment as teachers disclosed their own experiences of sexual harassment in school as a “rite of passage” (Jamal et al., 2015). Therefore, how staff comment on and respond to online or offline sexual harassment signals survivors what they can expect and signals to perpetrators that their organization (e.g., school) will likely support or defend them, creating less of a deterrent to them perpetrating.

Female-bodied adolescents (including trans, cisgender, and nonbinary) are most likely to be victims of IBSA (Van Ouytsel et al., 2021; Walker & Sleath, 2017), requiring instrumental and emotional support from school staff grounded in the knowledge of gender discrimination. Empowerment Theory posits that individuals can only act as healthy and efficacious as the systems are in which they navigate (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995). Therefore, improving the systems that surround youth (e.g., school staff) can have positive impact on the students’ themselves. Indeed, literature on the assessment and improvement of “school climate for sexual violence” or the norms, behaviors, and feelings around sexual assault prevention and response within a particular school suggests that there are multiple levels that need to be intervened upon in order to truly improve a school’s climate and reduce instances of sexual violence perpetration (Moylan et al., 2021). Thus, reducing gender stereotypes among school staff that promote blaming a victim for sexual violence perpetrated against them online or offline would be an important aspect of any staff training on IBSA, popular culture, or pornography.

Sexual media literacy programs for youth are a critical component of sexual health promotion and sexual violence prevention (Maas & Waterman, 2021). Still, adults working with youth also need such training if they are to understand how youth may be impacted by the media they consume and produce and how they can respond appropriately to IBSA. Similar to barriers to comprehensive sexual health education (Kramer, 2019; Stanger-Hall & Hall, 2011), there are barriers to getting pornography literacy approved for school-based curriculums. These include lengthy board approval processes, fears about parent backlash, and state-level policies that separate violence prevention and sex education (Kramer, 2019). Further, the existing programs can be cumbersome in terms of needed sessions (e.g., 10 hours over five sessions). To address these gaps in school-based sexual media literacy programming, we created a program less susceptible to previously mentioned barriers in that it is brief (yet comprehensive) and directed towards educating secondary school staff (as opposed to students), thus board approval is not needed. The PopPorn program is intended for staff professional development and is delivered with instructions for adapting the content for high school students.

The PopPorn Program

The PopPorn program is informed by Empowerment Theory (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995) and the logic of Media Literacy (Jeong et al., 2012). Taken together, the program is theoretically rooted in the intention to empower individuals within “helping systems” to develop their strengths and competencies to enact social change in public schools through understanding the media that youth consume and how these media impact attitudes and behavior. Before it was developed into a brief intervention, the PopPorn program began as a 1-hour lecture style talk that was given over 43 times to audiences across the US. Before this evaluation, the PopPorn program was implemented 13 times with informal written feedback provided by over 100 public school professionals. Each time we received feedback, we incorporated it to improve the content and delivery. Although this brief intervention focuses on staff education and attitudinal improvement, it is taught in such a way that participants learn how to implement aspects of the program for high school students. In other words, PopPorn can be adapted for adolescent learners, as teachers who complete the program can use the information they have gained to then educate their secondary school students in ways that can be incorporated into existing programing on bullying, internet safety, and media literacy; or health educators can adapt and implement modules that are approved by their district sexuality education advisory board. The PopPorn program (see Table 1) is a brief intervention built to accommodate most professional development contexts and constraints. The program is delivered in one 4-hour session (during a professional development day) in the form of 4 modules: (1) The New Sexual Environment; (2) Gendered Sexual Culture; (3) Teens’ Online Interactions; and (4) Sexual Violence and the Internet.

Table 1.

PopPorn Program Module Descriptions and Intended Learning Objectives.

| Modules | Themes | Objectives |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| The New Sexual Environment | -Time spent on internet-connected devices -Changes in sexualized advertising in traditional media -Instagram models -Pornography on social media -History of pornography -Internet pornography on tube-sites -Ethical, feminist, and Queer pornography -Hashtag activism to produce social movements to end sexual violence (e.g., #MeToo) |

-Participants will be able to describe the differences in pornography and erotica -Participants will be able to identify selfie-editing apps -Participants will be able to name which social media platforms allow pornography and which platforms intentionally censor it -Participants will consider how pornography is different for adolescents today, compared to their youth -Participants will understand how pornography is distributed on tube-sites -Participants will learn about the differences in ethically produced pornography and why it is not accessible to youth |

|

| ||

| Gendered Sexual Culture | -Disney movies -Popular romantic fiction -Sexual objectification of girls and women -Sexual aggression norms for men -The Sexual Double Standard and heteronormativity |

-Participants will learn how power imbalances are romanticized in popular romantic fiction, but are characteristic of abuse in real life -Participants will be able to define sexual objectification, the sexual double standard, and heteronormativity |

|

| ||

| Teens’ Online Sexual Experiences | -Sexual health websites -Sexting: consensual and nonconsensual -Impact and correlates of pornography use among adolescents -Pornography use and the brain: neuro myths and realities of pornography and sexual arousal |

-Participants will be able to determine the differences in consensual and nonconsensual sexting. -Participants will be able to recall terminology that explains why teen brains are more flexible and sensitive to neurostimulation. |

|

| ||

| Sexual Violence and the Internet | -Sexual violence in memes - “revenge” pornography and image-based sexual abuse -Child sexual abuse material disguised as amateur pornography -School sexual misconduct policies and their response to image-based sexual abuse -Engaging parents in educating children about pornography and technology-facilitated abuse -Engaging students in bystander intervention strategies to reduce online sexual harassment and abuse |

-Participants will be able to discern between causality and correlation in regard to pornography’s impact on sexual violence perpetration and victimization |

Module 1:

The New Sexual Environment gives an overview of current pop culture trends in sexuality and the history of pornography in the US. As most secondary school staff did not grow up with social media or internet access to pornography, it is important to first educate them on what we are referring to when we reference celebrity culture, sexualized media on Instagram, or pornography tube-sites. We start with a distinguishing definition of pornography vs. erotica. We also describe ethically produced pornography, pornography that represents queer sexualities, and other forms of niche pornography (e.g., “OnlyFans”) that have deviated from the more typical heteronormative pornography that evolved prior to the internet (Scott, 2016). This module aims to increase staff awareness of the influence that celebrities have over youth; the kinds of sex acts that are common on tube-sites compared to pornography that was distributed via VHS or DVD in the 80s and 90s; and how ethically produced pornography is typically behind a paywall precluding adolescents from easy viewing.

Module 2:

Gendered Sexual Culture describes the gender differences in how teens are socialized to feel and behave in romantic and sexual experiences. The Sexual Double Standard (Bordini & Sperb, 2013) is present in most sexualized and romantic media and often perpetuates the idea that girls need to be passive and boys need to be aggressive, setting the stage for coercion or violence to occur while masked as romance. This heteronormative ideal is so pervasive, that it can occur in same-sex or queer relationships as well. This module aims to challenge participants’ sexual double standard beliefs and build skills to identify this harmful social norm in romantic fiction, social media, and pornography.

Module 3:

Teens’ Online Interactions provides a review of the research on adolescents’ use of social media, digital sexual expression, and sexual communication in online spaces. Then, consensual sexting dynamics are explained. This module aims to reduce victim-blaming attitudes for sexts disseminated through a school and emphasizes the positive aspects that synchronization of texting can bring to discussing condom use and STIs.

Module 4:

Sexual Violence and the Internet provides an overview of the role of media in violence perpetration and victimization. This module also discusses what IBSA is and how it is perpetrated on secondary and higher education campuses, and how schools, teachers, and parents should respond to IBSA. This module aims to provide strategies to prevent IBSA through policy implementation and respond to IBSA in a way that centers on the victim’s needs.

The Present Study

For this exploratory study, we employed a repeated-measures, pre-test/post-test design to (1) identify staff perceptions of the degree to which pornography and IBSA impact student life and (2) determine the feasibility of providing an evidence-based brief intervention for public school staff. Our analysis plan was intended to generate parameter estimates that could inform power calculations for future randomized controlled trials of this intervention. The present study advances the current literature on sexuality education and sexual violence prevention by (a) identifying gaps in school staffs’ understanding of the sexualized online context their students often navigate and (b) assessing the efficacy of a brief program that educates staff on topics related to sexualized media. PopPorn adds to the growing number of sexual media literacy education programs, but to our knowledge is the first to equip secondary school staff working directly with teens with the tools they need to understand online sexual experiences, educate students, and prevent online sexual violence.

Our primary research questions were:

Do public school staff perceive online sexual experiences (e.g., pornography and IBSA) as problematic for student life?

Do changes in pornography and IBSA knowledge, efficacy in addressing pornography and IBSA-related issues, or sexual double standard attitudes occur after participation in the PopPorn program?

We hypothesized:

H1: Participants would perceive IBSA as negatively impacting school climate but would not perceive pornography use as negatively impacting school climate.

H2: Participants’ knowledge of popular culture and pornography would improve after PopPorn participation.

H3: Participants’ efficacy for discussing sexting, pornography, and online sexual harassment with youth would increase after PopPorn participation.

H4: Participants’ sexual double standard attitudes toward youth would decrease after PopPorn participation.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

We recruited participants from three different professional development training summits across Michigan that featured the PopPorn intervention as part of their summits. These training summits were for administrators, teachers, school counselors, social workers, reproductive health coordinators, and health educators. The research protocols were approved by the first author’s Institutional Review Board. Participants received no compensation for their participation. All participants (N = 79) were over 18 years old and were employed in the Michigan public school system. The mean age of participants was 43.97 (SD = 10.20) years old. The majority of the participants were White, with 87.7% indicating they were Caucasian, 2.7% Black or African American, 1.4% multi-racial, 1.4% Native American or Alaskan American, and 1.4% identifying as Asian or Asian American. The majority of the participants identified as women (n = 59), 15 identified as men, 1 participant identified as nonbinary, and 4 participants did not report their gender identity. Participants’ occupations comprised 35.6% teachers, 34.2% school counselors, 11% health educators, 5.5% administrators, 4.1% nurses, 2.7% social workers, 1.4% student assistance professionals, and 2.7% general staff.

Measures

The pre-test survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete and consisted of questions that evaluated knowledge about common online sexual experiences for youth, perceptions of how these experiences impact student life where they work, efficacy discussing these experiences with adolescents, and general attitudes about adolescent sexual experiences. The pre-test was administered online up to 7 days prior to the training. The post-test survey took approximately 8 minutes to complete and included all the same questions as the pre-test except for the perceptions of the impact on student life. The post-test was administered in-person after the training or online for up to 24 hours. Participants were instructed to construct a unique ID comprised of their initials as well as their month and day of birth to allow researchers to match pre-test and post-test data. During the training, participants were given cards to comment on during and after the intervention. At the end of the post-test, participants could also comment on anything they thought the research team should know.

Knowledge of Online Sexual Experiences Among Youth

As seen in Table 2, 17 questions assessed participants’ knowledge of the current research and trends in online sexual experiences among youth including which social media platforms contain sexually explicit content, how sexually explicit material is distributed through online platforms, how sex with minors is depicted on tube-sites, the difference between pornography addiction and problematic use of pornography, gender differences in pornography use, sexual health behaviors and pornography use, the violence depicted in pornography, initial age of pornography use, minors and pornography use, and online sexual harassment.

Table 2.

Pornography and IBSA Knowledge Before and After Participation in the PopPorn Program.

| Item | Proportion Correct (Pre-test) | Proportion Correct (Post-test) | Chi-Square test |

|---|---|---|---|

| There is pornographic content on Twitter (T) | 78.6% | 87.2% | χ2 = 7.25* |

| There is pornographic content on Facebook (F) | 25.7% | 87.2% | χ2 = 11.70*** |

| There is pornographic content on Instagram (T) | 84.3% | 92.3% | χ2 = 7.62* |

| There is pornographic content on Snapchat (T) | 100.0% | 100.0% | - |

| Internet pornography is organized and distributed just like YouTube, no age verification or payment required. (T) | 93.0% | 97.4% | χ2 = 17.97* |

| It is legal to show an 18-year-old depicted as a minor having sex with an adult today, but it was illegal in the 90s to do so. (T) | 33.8% | 79.5% | χ2 = 7.82* |

| Pornography causes people to perpetrate sexual violence (F) | 43.7% | 76.9% | χ2 = 2.84 |

| Pornography has been shown to cause attitudes that normalize sexual violence in experimental research. (T) | 95.8% | 100.0% | - |

| People who perpetrate sexual violence are typically heavy porn users. (T) | 56.3% | 81.6% | χ2 = 7.78** |

| Someone can become dependent on pornography for arousal or orgasm if they use too much of it. (T) | 95.8% | 97.4% | - |

| Girls watch nearly as much porn as boys these days. (T) | 62.0% | 82.1% | χ2 = 0.03 |

| Pornography use in adolescence is linked with less condom use and an earlier age at first sexual intercourse. (T) | 83.1% | 94.9% | χ2 = 9.06* |

| What percentage of scenes in popular pornography videos show physical aggression (slapping, choking, hitting, forced, gagging, spanking)? (88%) | 22.5% | 64.1% | χ2 = 7.09* |

| Studies range in findings, but most suggest that the age at first exposure to pornography online is: (11-13) | 36.6% | 46.6% | χ2 = 0.41 |

| If a minor (under 18) sends a nude photo of themselves, they could be charged with production of child pornography. (T) | 85.7% | 86.1% | - |

| If a minor (under 18) receives a nude photo of a minor, they could be charged with possession of child pornography. (T) | 88.7% | 85.6% | - |

| If a student is sexually harassing another student online and the school does not address it, this could be considered a violation of Title IX. (T) | 87.3% | 97.4% | χ2 = 8.48 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01,

p < .001, - = no parameter estimated.

N = 21-79. Chi-square tests were performed with McNemar tests to control for the inter-dependency of pre and post data.

Efficacy of Addressing Online Sexual Experiences

As seen in Table 3, 12 questions assessed participants’ confidence, fear, and embarrassment when talking to teens about pornography, sexting and online sexual harassment.

Table 3.

Change in Efficacy of Addressing Pornography, Sexting, and Sexual Harassment with Students.

| Pretest | Posttest | 95% CI for Mean Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Item | M | SD | M | SD | r | t | df | |

| Fear of Trouble |

||||||||

| I am afraid that I will face trouble if I discuss internet pornography issues with a teen | 55.47 | 33.02 | 46.33 | 32.93 | −2.51, 20.78 | .54 | 1.60 | 23 |

| I am afraid that I will face trouble if I discuss sexting issues with a teen | 50.66 | 31.40 | 35.13 | 32.26 | 4.72, 26.78 | .68 | 2.97** | 23 |

| I am afraid that I will face trouble if I could discuss online sexual harassment with a teen | 50.81 | 31.38 | 31.62 | 28.90 | 7.20, 31.65 | .61 | 3.32** | 20 |

| Mean of all Fear of Trouble items | 58.70 | 22.83 | 45.25 | 26.54 | 4.20, 22.71 | .70 | 3.03* | 19 |

|

| ||||||||

| Fear of Parents |

||||||||

| I am afraid that parents will be angry if I were to discuss internet pornography issues with a teen | 69.94 | 26.90 | 58.23 | 31.22 | −18.55, 1.58 | .43 | 2.09* | 30 |

| I am afraid that parents will be angry if I were to discuss sexting issues with a teen | 53.07 | 30.02 | 40.89 | 33.30 | −3.31, 27.69 | .24 | 1.62 | 26 |

| I am afraid that parents will be angry if I were to discuss online sexual harassment with a teen | 49.90 | 30.47 | 39.42 | 33.45 | −.38, 21.30 | .65 | 1.98 | 25 |

| Mean of all Fear of Parents items | 58.10 | 25.74 | 45.65 | 25.74 | 3.11, 21.76 | .60 | 2.75** | 25 |

|

| ||||||||

| Embarrassment |

||||||||

| I would be too embarrassed to discuss internet pornography with a teen | 39.35 | 28.34 | 26.45 | 19.88 | −1.40, 27.19 | .23 | 1.89 | 19 |

| I would be too embarrassed to discuss sexting issues with a teen | 75.11 | 23.36 | 78.33 | 21.47 | −16.15, 9.71 | .33 | −0.53 | 17 |

| I would be too embarrassed to discuss online sexual harassment with a teen | 23.90 | 23.48 | 18.18 | 18.36 | − 4.42, 15.83 | .58 | 1.19 | 16 |

| Mean of all Embarrassment items | 30.80 | 22.10 | 21.91 | 17.20 | −1.80, 19.54 | .51 | 1.77 | 15 |

|

| ||||||||

| Confidence |

||||||||

| I feel confident that I could discuss internet pornography issues with a teen | 67.12 | 25.84 | 77.97 | 18.13 | −19.54, −2.16 | .40 | −2.54* | 33 |

| I feel confident that I could discuss sexting issues with a teen | 78.69 | 21.25 | 84.54 | 14.53 | −.11.55, −.16 | .63 | −2.09* | 34 |

| I feel confident that I could discuss online sexual harassment with a teen | 86.33 | 15.72 | 88.15 | 12.150 | −7.62, 3.98 | .33 | −0.64 | 32 |

| Mean of all Confidence items | 79.60 | 15.04 | 84.42 | 11.46 | −10.08, .42 | .42 | −1.90 | 31 |

|

| ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Pornography Efficacy | 48.43 | 21.48 | 58.20 | 22.45 | −17.40, −2.10 | .61 | −2.62* | 26 |

| Sexting Efficacy | 58.33 | 19.80 | 70.50 | 21.04 | −20.34, −4.00 | .60 | −3.08** | 21 |

| Sexual Harassment | 59.33 | 23.84 | 71.33 | 23.60 | −22.64, −1.36 | .62 | −2.40* | 16 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01.

N = 21-79

Sexual Double Standard Attitudes Toward Youth

We assessed sexual double standard beliefs with the Scale for the Assessment of Sexual Standards Among Youth (SASSY), a 12-item subscale that evaluates one’s beliefs about gender roles among youth sexual behavior (Emmerink et al., 2017). Example items include “Once a boy is sexually aroused, a girl cannot really refuse sex anymore”; “It is more important for a girl to keep her virginity until marriage than it is for a boy”; “Sometimes a boy should apply some pressure to a girl to get what he wants sexually”. Participants responded using a Likert-type scale with values that ranged from 0 to 4. This measure had acceptable reliability in the current sample (α = .80). We also added items (see Table 4) relevant to the intervention content that included attitudes toward sexting, sexual harassment, acceptance of LGBTQ+ students, “IBSA victim-blaming”, sexual initiation, and sexual activity.

Table 4-.

Descritive statistics and t-test difference scores for changes in sexual double standard attitudes for offline and online behavior

| Pretest | Posttest | 95% CI for Mean Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Item | M | SD | M | SD | r | t | df | |

| Sexual Double Standard Among Youth |

11.10 | 7.14 | 7.83 | 5.17 | 1.53, 4.70 | .83 | 3.94* | 20 |

| Boys have more social power and influence in a school than girls do | 61.84 | 25.99 | 71.50 | 27.55 | −17.58, −1.73 | .66 | −2.49* | 31 |

| No student should send a nude photo of themselves if they do not want it circulated through school | 84.06 | 14.60 | 76.75 | 31.62 | −11.55, −.17 | .74 | −2.09* | 34 |

| If someone forwards a nude photo of another student, that should be considered sexual harassment | 8.73 | 14.27 | 10.02 | 10.81 | 1.03, 6.76 | .25 | 2.78.* | 36 |

| If a girl sends a boy a nude photo and he coerces her into sex, she is partially to blame | 17.05 | 28.45 | 2.09 | 4.66 | .07, 4.10 | −.22 | 2.15* | 22 |

| If a girl is posting provocative images on her social media account, she is asking for trouble | 26.18 | 31.44 | 9.96 | 20.40 | 1.14, 18.78 | .25 | 2.34* | 22 |

Note.

p < .05.

N = 21-79

Results

Staff Perceptions of Online Sexual Experiences and Their Impact on Student Life

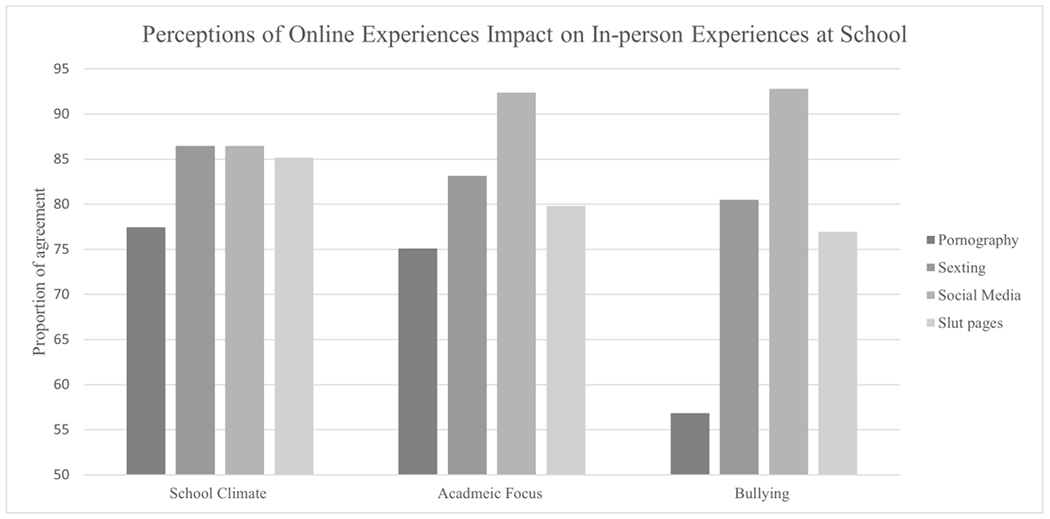

Participants indicated that online sexual experiences impact student life. For example, participants agreed that pornography at school and sexting negatively impact school climate, academic focus, and bullying sometimes (see Figure 1). They also perceived social media and slutpages to negatively impact school climate, academic focus, and bullying most of the time. Participants agreed that parents should receive school information on sexting, social media, pornography, slut pages, sexual harassment, and sexual consent (see Figure 2). They also agreed that students should receive age-appropriate information on these subjects but felt less sure about pornography and least sure about slutpages. These results provide partial support for Hypothesis 1.

Figure 1.

Staff Perceptions of the Degree to Which Students’ Online Sexual Experiences Negatively Impact In-person School Experiences.

Note. N = 67-79

Figure 2.

Staff Perceptions of the Need for Schools to Require Online Sexual Misconduct Education for Students and Parents.

Note. N = 66-79

Change in Knowledge of Popular Culture and Pornography

We hypothesized that participants’ knowledge of popular culture and pornography would improve after completing the PopPorn brief intervention (H2). Chi-square tests were used to assess changes in each item (see Table 2). A paired-samples t-test was conducted for overall knowledge to assess whether participant knowledge changed significantly after receiving the training. Overall knowledge of online sexual experience improved from the pre-test, (M = .69, SD = .09), to the post-test, (M = .86, SD = .09) after participants completed the training, t(32) = −5.03, p < .01), indicating Hypothesis 2 was supported. Specifically, participants responded correctly to 69% of questions at the pre-test, whereas, at the post-test participants correctly answered 86% of the questions. Specifically, participants learned that “barely legal” pornography, or depicting an adult as a minor having sex was illegal in the 90s, whereas in 2002 it became legal. They also learned that 88% of popular pornography scenes contain acts of physical aggression.

Change in Efficacy Addressing Online Sexual Experiences with Students

Hypothesis 3 stated participants’ overall efficacy and confidence in discussing online sexual behavior with students would increase, whereas their fear and embarrassment of teaching this material with students would decrease after completing the training. Participants answered 12 questions pertaining to their level of comfort discussing online sexual experiences with students. A paired-samples t-test analysis on overall efficacy showed improvement from the pre-test (M = 57.69 SD = 11.43), to the post-test (M = 70.13, SD = 14.43), indicating a significant change in overall efficacy, t(12) = −4.14, p < .001, providing support for Hypothesis 3. Specifically, efficacy in discussing pornography, t(26) = −2.62, p < .02, sexting, t(21) = −3.08, p < .01; and sexual harassment, t(16) = −2.40, p = .02) all increased after the intervention.

Although participants’ overall confidence discussing online sexual experiences with students did not significantly differ from pre-test to post-test t(31) = −1.88, p > .08, confidence discussing pornography t(33) = −2.54, p < .02 and sexting t(34) = −2.09, p < .03 with teens did increase after the intervention. Fear of facing trouble at work t(19) = 3.03, p < .02 and with parents t(25) = 2.75, p < .01 for discussing online sexual experiences with students also decreased after the intervention. However, perceived embarrassment while discussing online sexual experiences with teens did not change, t(15) = 1.77, p > .07.

Change in Sexual Double Standard Attitudes Toward Youth

Hypothesis 4 stated that participants would be less likely to uphold the sexual double standard after receiving the training. A paired-samples t-test revealed a significant decrease in the sexual double standard from pre-test (M = 10.30, SD = 7.14) to post-test, (M = 8.21, SD = 6.17), t(17) = 5.64, p < .001. Additional attitude items that addressed gendered power dynamics and victim blaming for sext dissemination also improved after participating in the PopPorn program (see Table 4).

Discussion

Sexual media literacy is a growing area of inquiry. With adolescents more easily accessing pornography on mobile devices at home or at school and turning to pornography as a means of learning about sex (Rothman et al., 2021), pornography literacy has emerged in response. Although media literacy efforts commonly focus on educating youth and parents, public school staff work on the front lines of adolescent social life where sexual harassment and IBSA frequently occur. Thus, education of school staff in media literacy and talking to students about sexualized, pornographic media is crucial to improving school climate and student experiences. The current study adds important information to the literature on the feasibility of training public school staff on the impact of pornography on adolescent sexual development and the realities of IBSA among students. Our study shows the promise of the PopPorn program for providing this training, as staff that completed the program demonstrated increased knowledge of and efficacy in addressing students’ pornography use and perpetration of IBSA and a reduction in harmful sexual double standard attitudes.

Generally speaking, public school staff overwhelmingly agreed that pornography and IBSA education are needed. They reported that incorporating aspects of popular culture seemed like an easier way to broach conversations with youth. Their perceptions were that pornography use at school and sexting were predominately used for negative interactions like bullying and harassment. Thus, educating public school staff on responding to these issues is a critical piece of school-based violence prevention. Consistent with Empowerment Theory (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995), PopPorn explores environmental factors that contribute to social issues (e.g., sexual violence) instead of blaming victims and describes the positive impact that can happen in a school where staff share a sense of responsibility for supporting victims over defending perpetrators.

Our evidence indicates that participants’ knowledge of pornography overall did indeed increase after participation in the PopPorn intervention. Notably, participants understood that girls are almost just as likely to see pornography as boys are, a trend that has changed since the advent of internet pornography. This is important in addressing harmful attitudes that girls are not as sexual as boys. Participants also learned about the Ashcroft vs. Free Speech Coalition case from 2002 which essentially made “barely legal” porn legal. Before this ruling, the common forms of “teen” porn, or pornography showcasing actors over 18 pretending to be under 18 was not legal and considered a form of child pornography. One participant stated, “understanding that ruling helped me to see how much porn has changed since I was a teen.”

We found a significant decline in sexual double standard beliefs after the intervention. Prior work suggests that these beliefs are difficult to change (Iyer & Aggleton, 2013); therefore, it would be important to determine if these changes are sustained over time. Findings also show that program participants’ attitudes towards pornography were changed following the PopPorn program. Although fewer participants thought that pornography causes sexual violence in the post-test than in the pre-test, this change was not statistically significant. However, participants did understand that those who perpetrate sexual violence tend to be heavy pornography users. Therefore, the curriculum should include an “important takeaway messages” section at the end that explicitly re-states that pornography does not cause violence, but that the association is reciprocal. It should also re-state that people with a greater proclivity toward violence will be more susceptible to harmful sexual violence scripts in pornography (Wright et al., 2021) and for adolescents who perceive it to be more realistic will be more vulnerable to its effects than those who perceive pornography as unrealistic (Wright et al., 2018; Peter & Valkenburg, 2016).

We believe that it is important to emphasize that adolescent sexual behavior is developmentally normative, making some pornography use and sexting normative as well. For example, masturbation is a safe sexual practice, and for many LGBTQ youth, pornography may be the only medium in which their sexuality is positively depicted (Litsou et al., 2020). Chiefly, the PopPorn program emphasizes that (1) pornography use is complicated and its impact is highly dependent on many individual-level factors and (2) the consensual sending of a nude image to a romantic partner is an expression of intimacy and trust, and therefore not problematic. Only when that nude is nonconsensually shared with others that problems ensue. As more research suggests some positive impact or at least not an increase in sexual risk-taking for those who engage in online sexual activities (Luder et al., 2011), incorporating pornography and IBSA education into student curricula is the next important step for fostering media literacy skills and sexual health among youth. Given that harmful sexual double standard attitudes are notoriously difficult to change, more consistent integration of gender equality concepts (particularly surrounding student sexual behavior) could also create a supportive staff that students will disclose violence experiences to.

Limitations

Given that this was a pilot study aimed to determine (1) the perceived need for pornography education, (2) the feasibility of incorporating it into staff professional development, and (3) preliminary efficacy of the PopPorn brief intervention, our results indicate an established need and a promising program. However, this study has limitations that future research should improve upon. One participant stated, “I appreciated that this curriculum could be covered in some sort of sexual violence forum [as opposed to going through strict sex education board approvals].” However, given the small sample size and no control group, a randomized control trial with a larger sample and control group is warranted to test for true efficacy. Therefore, our next step is to conduct a longitudinal RCT to determine causal and longer-term impact. We would like to have a team of media literacy experts and sexuality educators evaluate the modules before the next stage of efficacy and effectiveness training to increase validity and relevance. There were also limited evaluation questions given the pilot nature of this exploratory study. However, in Module 4, policy development is discussed, therefore future evaluations of this program should include an intention for policy implementation as IBSA of any kind should be considered a violation of Title IX and not be tolerated in public schools.

Strengths of the PopPorn Program

The PopPorn program is brief (4 hours) compared with other programs (up to 10 hours), making it easy to add to existing professional development summits. It is written in such a way that it can be modified for adolescents, providing a unique opportunity for relevant staff (e.g., health educators, reproductive health coordinators) to add to existing sexual health curricula. For example, one participant stated, “we need more information like this for our health educators.” The addition of the popular culture lens to the program content is intended to mitigate the taboos of discussing pornography or resistance to pornography literacy programs for youth. By connecting pornography, film, television, advertising, and social media, many examples beyond pornography are given for staff to incorporate into violence prevention strategies for youth. Lastly, by incorporating popular culture and pornography, administrators seemed to be more open to including this training and advertising it widely, as opposed to a pornography(only) literacy program.

Conclusion

Staff, students, and sex educators agree that online pornography and social media are permeating aspects of youth sexual development, requiring some form of education (Crabbe & Flood, 2021; Dawson et al., 2019). The PopPorn program uses engaging content to help public school staff discuss and respond appropriately to sexual violence perpetrated in both online and offline spaces. These findings can be added to a growing number of promising programs to improve pornography (and other sexual media) literacy skills to support adolescents in their development of healthy sexual attitudes and behaviors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Molly Countermine and Amelia Lawless, the Sacramento State Peer Health Educators, the East Lansing Sexuality Education Advisory Board, the Michigan Organization on Adolescent Sexual Health, Kayln Coppedge, and Lydia Rutkowski for their roles in the development and evaluation of this curriculum.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [M.K.M], upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors would like to declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Human Subjects Research Ethics Board Approval

The Michigan State University IRB approved this study on March 1, 2019 (STUDY00002252).

References

- Bates S (2017). Revenge porn and mental health: A qualitative analysis of the mental health effects of revenge porn on female survivors. Feminist Criminology, 12, 22–42. 10.1177/1557085116654565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bordini GS, & Sperb T (2013). Sexual Double Standard: A review of the literature. Sexuality & Culture, 17, 686–704. 10.1007/s12119-012-9163-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox K (2020). Millions of videos purged from Pornhub amid crackdown on user content. Ars Technica. [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe M, & Flood M (2021). School-based education to address pornography’s influence on young people: A proposed practice framework. 10.1080/15546128.2020.1856744, 16(1), 1–37. 10.1080/15546128.2020.1856744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson K, Nic Gabhainn S, & MacNeela P (2020). Toward a model of porn literacy: Core concepts, rationales, and approaches. Journal of Sex Research, 57, 1–15. 10.1080/00224499.2018.1556238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Heer B, Prior S, & Fejervary J (2020). Women’s pornography consumption, alcohol use, and sexual victimization. Violence Against Women. 10.1177/1077801220945035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerink PMJ, van den Eijnden RJJM, ter Bogt TFM, & Vanwesenbeeck I (2017). A scale for the assessment of sexual standards among youth: Psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior 2017 46:6, 46(6), 1699–1709. 10.1007/S10508-017-1001-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A (2020). Beyond porn literacy: Drawing on young people’s pornography narratives to expand sex education pedagogies. Sex Education, 20, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, & Fineran S (2016). Sexual harassment, bullying, and school outcomes for high school girls and boys. Violence Against Women, 22, 112–133. 10.1177/1077801215599079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry N, & Flynn A (2019). Image-based sexual abuse: Online distribution channels and illicit communities of support. Violence Against Women, 25(16), 1932–1955. 10.1177/1077801219863881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbenick D, Fu TC, Wright P, Paul B, Gradus R, Bauer J, & Jones R (2020). Diverse sexual behaviors and pornography use: Findings from a nationally representative probability survey of americans aged 18 to 60 years. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(4), 623–633. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer P, & Aggleton P (2013). ‘Sex education should be taught, fine…but we make sure they control themselves’: Teachers’ beliefs and attitudes towards young people’s sexual and reproductive health in a Ugandan secondary school. 10.1080/14681811.2012.677184, 13(1), 40–53. 10.1080/14681811.2012.677184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal F, Bonell C, Harden A, & Lorenc T (2015). The social ecology of girls’ bullying practices: Exploratory research in two London schools. Sociology of Health & Illness, 37(5), 731–744. 10.1111/1467-9566.12231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SH, Cho H, & Hwang Y (2012). Media literacy interventions: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Communication, 62, 454–472. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01643.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen MJE, & Peter J (2015). Gender (in)equality in internet pornography: A content analysis of popular pornographic internet videos. Journal of Sex Research, 52(7), 721–735. 10.1080/00224499.2014.976781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohut T, Baer JL, & Watts B (2016). Is pornography really about “making hate to women”? Pornography users hold more gender egalitarian attitudes than nonusers in a representative american sample. Journal of Sex Research, 53(1), 1–11. 10.1080/00224499.2015.1023427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer AS (2019). Framing the debate: The status of US sex education policy and the dual narratives of abstinence-only versus comprehensive sex education policy. 10.1080/15546128.2019.1600447, 14(4), 490–513. 10.1080/15546128.2019.1600447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Litsou K, Byron P, McKee A, & Ingham R (2020). Learning from pornography: Results of a mixed methods systematic review. Sex Education, 1–17. 10.1080/14681811.2020.1786362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low S, Van Ryzin MJ, Brown EC, Smith BH, & Haggerty KP (2014). Engagement matters: Lessons from assessing classroom implementation of steps to respect: A bullying prevention program over a one-year period. Prevention Science, 15(2), 165–176. 10.1007/s11121-012-0359-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luder MT, Pittet I, Berchtold A, Akré C, Michaud P-A, & Surís J-C (2011). Associations between online pornography and sexual behavior among adolescents: Myth or reality? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 1027–1035. 10.1007/s10508-010-9714-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas MK, Cary KM, Clancy EM, Klettke B, McCauley HL, & Temple JR (2021). Slutpage use among U.S. college students: The secret and social platforms of Image-Based Sexual Abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 1, 3. 10.1007/s10508-021-01920-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas MK, McCauley HL, Bonomi AE, & Leija SG (2018). “I was grabbed by my pussy and Its #NotOkay”: A twitter backlash against Donald Trump’s degrading commentary. Violence Against Women, 24(14), 1739–1750. 10.1177/1077801217743340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas MK & Waterman EA (2021). New perspectives on the integration of sexual health promotion and sexual violence prevention during emerging adulthood. In Morgan EM, & Van Dulmen MH (Eds.) Sexuality in Emerging Adulthood. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Ly A, Rash CL, Van Ouytsel J, & Temple JR (2018). Prevalence of multiple forms of sexting behavior among youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(4), 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moylan CA, Javorka M, Maas MK, Meier E, & McCauley HL (2021). Campus sexual assault climate: Toward an expanded definition and improved assessment. Psychology of violence. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt S, Sage C, Ghura S, & O’Brian J (2021). The cost of reporting: Perpetrator retaliation, institutional betrayal, and student survivor pushout. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DD, & Zimmerman MA (1995). Empowerment theory, research, and application. American Journal of Community Psychology 1995 23:5, 23(5), 569–579. 10.1007/BF02506982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter J, & Valkenburg PM (2016). Adolescents and pornography: A review of 20 years of research. Journal of Sex Research, 53, 509–531. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1143441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PettyJohn ME, Muzzey FK, Maas MK, & McCauley HL (2019). # HowIWillChange: Engaging men and boys in the# MeToo movement. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 20, 612–622. [Google Scholar]

- Rostad WL, Gittins-Stone D, Huntington C, Rizzo CJ, Pearlman D, & Orchowski L (2019). The association between exposure to violent pornography and teen dating violence in grade 10 high school students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48, 2137–2147. 10.1007/s10508-019-1435-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Adhia A, Christensen TT, Paruk J, Alder J, & Daley N (2018). A pornography literacy class for youth: Results of a feasibility and efficacy pilot study. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 13(1), 1–17. 10.1080/15546128.2018.1437100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Beckmeyer JJ, Herbenick D, Fu TC, Dodge B, & Fortenberry JD (2021). The prevalence of using pornography for information about how to have sex: Findings from a nationally representative survey of US adolescents and young adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50, 629–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruberg B (2016). Doing it for free: Digital labour and the fantasy of amateur online pornography. Porn Studies, 3, 147–159. 10.1080/23268743.2016.1184477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvalcaba Y, & Eaton AA (2019). Nonconsensual pornography among US adults: A sexual scripts framework on victimization, perpetration, and health correlates for women and men. Psychology of Violence, 10(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, & Hirsch JS (2020). Comprehensive sexuality education as a primary prevention strategy for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21, 439–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KL (2016). Performing labour: Ethical spectatorship and the communication of labour conditions in pornography. Porn Studies, 3, 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Scull T, Malik C, Keefe E, & Schoemann A (2019). Evaluating the short-term impact of Media Aware Parent, a web-based program for parents with the goal of adolescent sexual health promotion. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1686–1706. 10.1007/s10964-019-01077-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon W, & Gagnon JH (2003). Sexual scripts: Origins, influences and changes. In Qualitative Sociology (Vol. 26, Issue 4, pp. 491–497). 10.1023/B:QUAS.0000005053.99846.e5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger-Hall KF, & Hall DW (2011). Abstinence-only education and teen pregnancy rates: Why we need comprehensive sex education in the U.S. PLoS ONE, 6(10). 10.1371/journal.pone.0024658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl CA, Rhyner KJ, Terrance CA, & Lugo NR (2018). An examination of nonconsensual pornography websites. Feminism and Psychology, 28(1), 50–68. 10.1177/0959353517720225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valido A, Espelage DL, Hong JS, Rivas-Koehl M, & Robinson LE (2020). Social-ecological examination of non-consensual sexting perpetration among US adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ouytsel J, Walrave M, De Marez L, Vanhaelewyn B, & Ponnet K (2021). Sexting, pressured sexting and image-based sexual abuse among a weighted-sample of heterosexual and LGB-youth. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106630. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Gray F, Mcglynn C, Kureshi I, & Butterby K (2021). Sexual violence as a sexual script in mainstream online pornography. The British Journal of Criminology, 1–18. 10.1093/bjc/azab035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K, & Sleath E (2017). A systematic review of the current knowledge regarding revenge pornography and non-consensual sharing of sexually explicit media. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 36, 9–24. 10.1016/j.avb.2017.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM (2016). Media and sexualization: State of empirical research, 1995–2015. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1142496, 53(4–5), 560–577. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1142496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PJ, Paul B, & Herbenick D (2021). Preliminary insights from a U.S. probability sample on adolescents’ pornography exposure, media psychology, and sexual aggression. Journal of Health Communication, 1–8. 10.1080/10810730.2021.1887980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PJ, Sun C, & Steffen N (2018). Pornography consumption, perceptions of pornography as sexual information, and condom use. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44, 800–805. 10.1080/0092623X.2018.1462278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]