Abstract

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants has significantly reduced the efficacy of some approved vaccines. A fourth dose of NVX-CoV2373 (5 µg SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike [rS] protein + 50 µg Matrix-M™ adjuvant; Novavax, Gaithersburg, MD) was evaluated to determine induction of cross-reactive antibodies to variants of concern. A phase II randomized study (NCT04368988) recruited participants in Australia and the United States to assess a primary series of NVX-CoV2373 followed by two booster doses (third and fourth doses at 6-month intervals) in adults 18–84 years of age. The primary series was administered when the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain was prevalent and the third and fourth doses while the Alpha and Delta variants were prevalent in AUS and US. Local/systemic reactogenicity was assessed the day of vaccination and for 6 days thereafter. Unsolicited adverse events (AEs) were reported. Immunogenicity was measured before, and 14 days after, fourth dose administration, using anti-spike serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) and neutralization assays against ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain and Omicron sublineages. Among 1283 enrolled participants, 258 were randomized to receive the two-dose primary series, of whom 104 received a third dose, and 45 received a fourth dose of NVX-CoV2373. The incidence of local/systemic reactogenicity events increased after the first three doses of NVX-CoV2373 and leveled off after dose 4. Unsolicited AEs were reported in 9 % of participants after dose 4 (none of which were severe or serious). Anti-rS IgG levels and neutralization antibody titers increased following booster doses to a level approximately four-fold higher than that observed after the primary series, with a progressively narrowed gap in response between the ancestral strain and Omicron BA.5. A fourth dose of NVX-CoV2373 enhanced immunogenicity for ancestral and variant SARS-CoV-2 strains without increasing reactogenicity, indicating that updates to the vaccine composition may not be currently warranted.

Keywords: Booster, COVID-19, Vaccine immunogenicity, Vaccine safety, SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, NVX-CoV2373

1. Introduction

The emergence and rapid propagation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants, in particular the Omicron sublineages, which have mutations that increase viral transmissibility and enhance the viruses' ability to evade vaccine immunity [1], [2], can significantly reduce the efficacy of approved vaccines. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recommended the development of variant-specific vaccines for the 2022–2023 winter [3], although some have countered that any additional protection provided by the Omicron-specific vaccines may be minimal [4], [5].

The degree to which immunity induced by SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain-based vaccines is effective against the Omicron sublineages depends, partly, on the extent that the vaccine is able to induce broadly cross-reactive antibodies. The NVX-CoV2373 vaccine may be able to preferentially induce these antibodies because of its composition. The vaccine consists of full-length, pre-fusion recombinant spike (S) protein trimers with epitopes conserved across variants. In addition, the vaccine is co-formulated with a saponin-based Matrix-M™ adjuvant (Novavax, Gaithersburg, MD). Similar saponin-based adjuvants have demonstrated the ability to enhance antibody avidity, affinity maturation, and epitope spreading, which may drive recognition of conserved, more immunologically cryptic but broadly neutralizing epitopes [6]. For example, the ISCOMATRIX adjuvant promotes epitope spreading and antibody affinity maturation of a pandemic influenza A (H7N9) virus-like particle vaccine which correlates with virus neutralization in humans [6]. In the context of seasonal influenza, a hemagglutinin (HA) nanoparticle Matrix-M−adjuvanted vaccine was shown to induce polyclonal antibodies in humans that mimic broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies that recognize two conserved regions of the head domain, namely the receptor binding site and the vestigial esterase subdomain. The findings raised the potential for an adjuvanted HA subunit vaccine to induce broadly protective immunity [7]. Clinical and ferret studies using a recombinant full-length HA in a nanoparticle with Matrix-M adjuvant, confirmed that the H3N2 component of the vaccine-induced broadly cross-reacting antibodies against the past, current, and forward-drifted H3N2 strains covering multiple years [8], [9]. Humans are universally primed to influenza, and as this is gradually also becoming the case for SARS-CoV-2, we speculated that repetitive boosting with an ancestral recombinant spike (rS) nanoparticle vaccine with Matrix-M adjuvant, might similarly induce broadly neutralizing antibodies that recognize the drift variants.

In two phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of healthy adult participants who received two doses of NVX-CoV2373, vaccine efficacy of 89.7 % (95 % confidence interval [CI]: 80.2 to 94.6) and 90.4 % (95 % CI: 82.9 to 94.6) was established in the United Kingdom (N = 15,139) and the United States and Mexico (N = 29,582), respectively [10], [11]; however, it should be noted that these studies were conducted prior to the emergence of the Omicron variant. Recently, however, as waning immunity both over time and with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants has been noted with authorized and approved coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines, the safety and immunogenicity of booster doses of NVX-CoV2373 were evaluated.

As part of an ongoing phase II, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of NVX-CoV2373 conducted in Australia and the United States, two doses of NVX-CoV2373 were administered 21 days apart [12], followed initially by a single booster dose after approximately 6 months [13]. Administration of a single booster dose resulted in an incremental increase in the frequency of reactogenicity events along with significantly enhanced immunogenicity, including an approximate 33.7-fold increase from pre-booster levels in anti-S serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) against the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain. In a comparison with SARS-CoV-2 variants, markedly higher anti-rS IgG activity, neutralization titers, and hACE2 receptor inhibition were noted against several variants, including Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 sublineages [13]. In a continuation of this study, a second booster dose of NVX-CoV2373 was administered after another 6 months. The safety and immunogenicity after the fourth dose of NVX-CoV2373 are reported herein.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

As part of an ongoing phase II, randomized, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled study of NVX-CoV2373 (methods previously reported [13]), a subset of healthy adult participants received a two-dose primary series followed by third and fourth doses of NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax, Inc.) administered at 6-month intervals. All active booster vaccinations were administered at the same dose level as the primary vaccination series (0.5 ml containing 5 µg SARS-CoV-2 rS with 50 µg Matrix-M adjuvant; lot numbers PAR 28003 and PAR 28004) via intramuscular injection with a 23- or 25-gauge needle in the deltoid muscle. Only participants who received four doses of NVX-CoV2373 are included in this analysis.

2.2. Safety assessments

Participants utilized an electronic diary to record solicited local and systemic reactogenicity on the day of vaccination and for an additional 6 days thereafter. Unsolicited adverse events (AEs) were reported through 28 days after vaccination. Serious AEs (SAEs), medically attended AEs (MAAEs) attributed to vaccine, and AEs of special interest were reported through the end of the study [14].

2.3. Immunogenicity assessments

Blood samples for immunogenicity analysis were collected prior to each vaccination and after each vaccination on days 0, 35, 189, 217, 357, and 371. Immune response was assessed for ancestral, BA.1, and BA.4/5 variants, as previously described, before and after each dose of NVX-CoV2373 via serum neutralizing antibodies using validated pseudovirus neutralization assays [15]; via a validated anti-rS IgG assay (assessing ancestral, BA.1, and BA.5) [16]; and via a validated SARS-CoV-2 hACE2 receptor binding inhibition assay (with ancestral strain SARS-CoV-2 spike protein as the assay substrate) [13].

Only participants who were SARS-CoV-2 negative prior to NVX-CoV2373 administration, who received all vaccine doses per-protocol, who did not have a positive anti-nucleocapsid protein result on or after day 371, and who had no significant protocol deviations that impacted immunogenicity response at the corresponding study visit (e.g., receipt of vaccine for COVID-19 or other prohibited medication, receipt of incorrect treatment) were included in the analysis. For this analysis, unblinding was not considered a protocol deviation that impacted immune response.

The trial protocol was approved by the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) and Advarra Central Institutional Review Board (Columbia, Maryland, USA) and is registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04368988). This study was performed in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Safety oversight for the study was provided by an independent safety monitoring committee.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

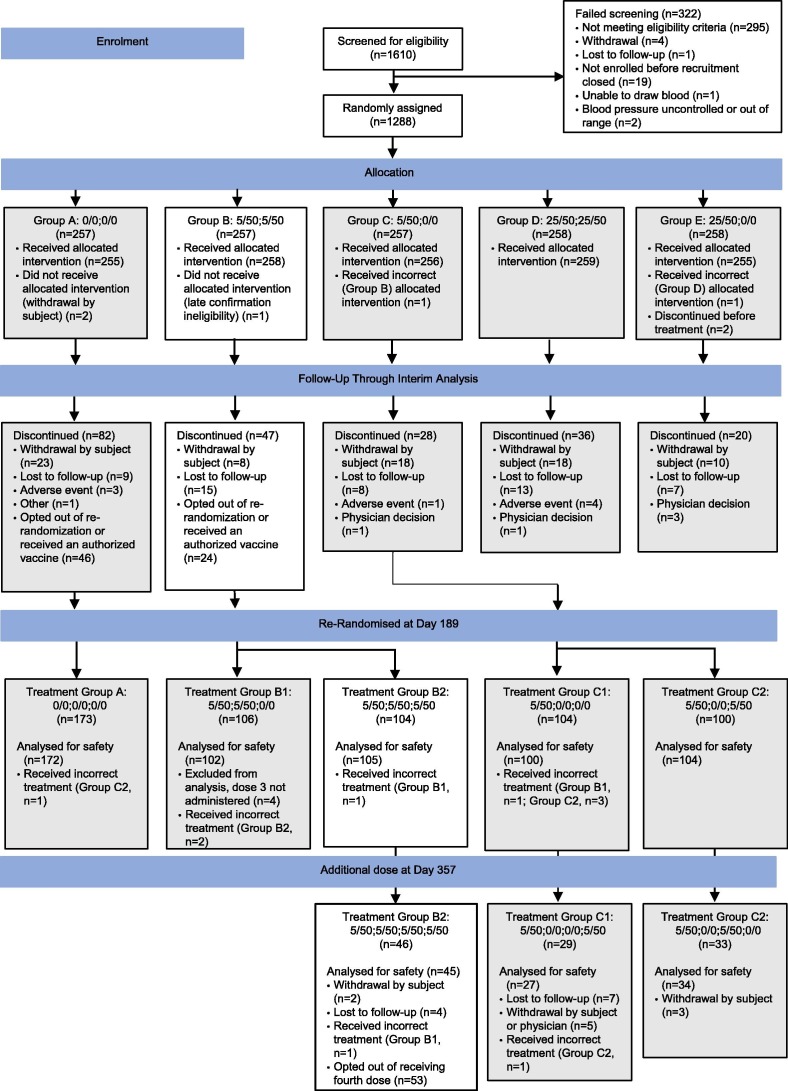

Of 1610 participants screened from 24 August 2020 to 25 September 2020, 1288 were randomly selected and 1283 received at least one dose of study vaccine. Of the 258 participants who were randomly assigned to receive two doses of NVX-CoV2373 (5 μg SARS-CoV-2 rS + 50 μg Matrix-M), 207 received both doses and were then re-randomized to receive a dose of placebo (n = 102) or a third dose of NVX-CoV2373 (n = 105) after 6 months. Of the participants who received three doses of NVX-CoV2373 and chose to continue in the study, 45 received a fourth dose of NVX-CoV2373 6 months after the third dose (Fig. 1 ). A subset of participants who received four doses and who met the immunogenicity analysis criteria (n = 34) were included in the immunogenicity analysis.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Diagram. White boxes demonstrate the flow of participants included in this analysis, including those who received one, two, three, or four doses of 5 µg SARS-CoV-2 rS + 50 µg Matrix-M™ (Novavax, Gaithersburg, MD) adjuvant (5/50) on day 0, day 21, day 189, and day 357, respectively. Gray boxes include participant groups not covered in this analysis. 0/0: 0 µg SARS-CoV-2 rS + 0 µg Matrix-M adjuvant; 5/50: 5 µg SARS-CoV-2 rS + 50 µg Matrix-M adjuvant; 25/50: 25 µg SARS-CoV-2 rS + 50 µg Matrix-M adjuvant.

The demographic characteristics of participants were similar when compared by number of doses received (Table 1 ). For the fourth dose, the mean age of 55 years was slightly higher than the mean age of 52 years after the primary series and after dose 3. This is reflected in the age group distribution, where 56% were ≥ 60 to ≤ 84 years of age compared with 46 % for the primary series and dose 3. Most participants were White (89 %) with a negative baseline SARS-CoV-2 serostatus (98%).

Table 1.

Demographics characteristics for participants who received up to four doses of NVX-CoV2373 (safety analysis seta).

|

n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter |

Primary series (Doses 1 &2) n = 258 |

Dose 3 n = 105 |

Dose 4 n = 45 |

| Age – years, mean (SD) | 51.3 (17.5) | 51.7 (17.1) | 55.3 (15.4) |

| 18–59, No. (%) | 140 (54) | 57 (54) | 20 (44) |

| 60–84, No. (%) | 118 (46) | 48 (46) | 25 (56) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 119 (46) | 58 (55) | 18 (40) |

| Female | 139 (54) | 47 (45) | 27 (60) |

| Race or ethnic group, No. (%) | |||

| White | 226 (87) | 93 (89) | 40 (89) |

| Black or African American | 7 (3) | 3 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Asian | 18 (7) | 7 (7) | 3 (7) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Multiracial | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Not reported/missing | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.10 (4.12) | 27.43 (4.04) | 28.37 (4.47) |

| Baseline SARS-CoV-2 seropositive, No. (%) | 5 (2) | 3 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Country of participants, No. (%) | |||

| Australia | 134 (52) | 57 (54) | 23 (51) |

| United States | 124 (48) | 48 (46) | 22 (49) |

SD, standard deviation.

Participants in the safety analysis set are counted according to the treatment received to accommodate for treatment errors.

3.2. Safety

3.2.1. Reactogenicity

Reporting of solicited local and systemic reactogenicity events of any grade generally increased after each of the first three doses of NVX-CoV2373 and leveled off or decreased after the fourth dose (Fig. 2 ). Grade 3 or higher (grade 3+) reactogenicity events generally followed a similar pattern. Following the fourth dose, 73 % (n = 30) of participants reported any solicited local reactions (tenderness, pain, swelling, erythema) of any grade and 19 % (n = 8) reported for grade 3+ events compared with 83 % (n = 80) for any grade and 13 % (n = 13) for grade 3+, following the third dose. Only erythema was reported more frequently after the fourth dose, with 20 % (n = 8) for any grade and 15 % (n = 6) for grade 3+ compared with 10 % (n = 10) for any grade and 1 % (n = 1) for grade 3+ after the third dose. Following the fourth dose, local reactions were short-lived (median duration: pain, 2 days; tenderness and erythema, 3 days; swelling, 4 days).

Fig. 2.

Solicited (A) local and (B) systemic reactogenicity events for participants who received NVX-CoV2373, by dose number and severity.

Solicited systemic reactions showed a similar pattern with reporting rates for any event (fatigue, headache, muscle pain, malaise, joint pain, nausea/vomiting, and fever) of 68 % (n = 28) for any grade (17 % [n = 7] grade 3+) after the fourth dose compared with 77 % (n = 75) for any grade (15 % [n = 15] grade 3+) after the third dose. Notably, the incidence of fever remained low after the fourth dose at 10 % with no grade 3+ events reported. Following the fourth dose, solicited systemic reactions were also transient in nature (median duration: fever and headache, 1 day; fatigue, malaise, joint pain, nausea/vomiting, and muscle pain, 2 days).

3.2.2. Unsolicited AEs

After the fourth dose, unsolicited treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) occurred in 4/45 participants (9 %), none of which were severe or serious (Table 2 ). The most common unsolicited TEAEs were injection site pain, injection site erythema, injection site pruritus, and pruritus, all of which occurred in one participant each. There were no SAEs, MAAEs, or potentially immune-mediated medical conditions (PIMMCs) after the fourth dose.

Table 2.

Overall summary of unsolicited TEAEs for participants who received up to four doses of NVX-CoV2373 (safety analysis seta).

|

No. (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter |

Dose 1 n = 258 |

Dose 2 n = 255 |

Dose 3 n = 105 |

Dose 4 n = 45 |

| Any unsolicited TEAE | 31 (12) | 76 (30) | 14 (13) | 4 (9) |

| Treatment-related | 0 | 6 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (9) |

| Severe | 2 (1) | 8 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Leading to vaccination discontinuation | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

| Leading to study discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Any serious TEAEs | 0 | 8 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-related | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-emergent MAAEs | 11 (4) | 49 (19) | 7 (7) | 0 |

| Treatment-related | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| PIMMC | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-related | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AESIs relevant to COVID-19 | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

NVX-CoV2373 = 5 µg SARS-CoV-2 rS + 50 µg Matrix-M adjuvant on day 0, day 21, day 189, and day 357.

AESI, adverse event of special interest; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; MAAE, medically attended adverse event; PIMMC, potentially immune-mediated medical condition; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Participants in the safety analysis set are counted according to the treatment received to accommodate for treatment errors.

3.2.3. Immunogenicity

After an initial decline following primary vaccination, a third dose of NVX-CoV2373 increased anti-rS IgG levels for the ancestral strain to a level approximately four-fold higher than that observed after the primary series (Fig. 3 a). Compared with the decline after the primary series, a more gradual decrease in levels occurred after the third dose, with anti-rS IgG levels increasing again after the fourth dose to levels similar to those seen after the third dose. The immune response to Omicron BA.1 and BA.5 demonstrated a similar pattern, with a progressive narrowing of the gap between the magnitude of response to the ancestral strain compared with the Omicron variants as the number of doses increased (Fig. 3 a).

Fig. 3.

Immunogenicity of NVX-CoV2373 against ancestral and variant strains of SARS-CoV-2, by dose (n = 34). (Panel A) Anti-rS IgG levels by dose for the ancestral (n = 34) and BA.1 (n = 31) and BA.5 (n = 34) variants. Data were not available for the BA.1 variant for 3 of 34 participants. Dotted line represents approximate correlates of protection levels as derived for the ancestral strain [22]. (Panel B) Neutralizing (ID50) antibody titers by dose for the ancestral, BA.1, and BA.4/BA.5 variants (n = 34 for all strains). Dotted line represents approximate correlates of protection titers as derived for the ancestral strain [22]. CoP, correlate of protection; CI, confidence interval; GMT, geometric mean titer; ID50, 50 % inhibitory dose; IgG, immunoglobulin; rS, recombinant spike; VE, vaccine efficacy.

Neutralization titers followed a similar pattern to anti-rS IgG levels. A third dose of NVX-CoV2373 increased SARS-CoV-2 neutralization titers for the ancestral strain to a level approximately 4.7-fold higher than that observed after the primary series, and titers after the fourth dose were similar to those seen after the third dose (Fig. 3 b). The immune response to Omicron BA.1 and BA.4/BA.5 variants demonstrated a similar pattern in neutralization titers.

A validated functional hACE2 receptor binding inhibition assay was used to compare hACE2 binding inhibition titers after each dose of NVX-CoV2373 (Fig. 4 ). Serum hACE2 inhibition titers increased 13.4-fold from baseline after the primary series (day 35). From just before the third dose to day 217, hACE2 inhibition titers increased 43.8-fold. At day 371, inhibition titers increased 34.2-fold over day 189.

Fig. 4.

hACE2 inhibition after 4 doses of NVX-CoV2373 (n = 34). Ancestral strain SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein was used as the assay susbtrate. GMFR for various comparisons are depicted above the bars. CI, confidence interval; GMFR, geometric mean fold rise; LLOQ, lower limit of quantitation.

4. Discussion

In this report, we describe the first available safety and immunogenicity data after a fourth dose of NVX-CoV2373, which was gathered from an ongoing phase II, randomized, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled study. With an increasing number of doses of NVX-CoV2373, there appears to be enhanced cross-reactive immunogenicity without any notable increases in either solicited local or systemic reactogenicity or in unsolicited TEAEs.

The incidence of both unsolicited local and systemic reactogenicity leveled off after the fourth dose of NVX-CoV2373 compared with the increases reported after each of the first three doses. Grade 3+ events remained steady compared with the third dose, except for erythema, which demonstrated an increase in the frequency of grade 3+ events out of the total number of events (15 % after the fourth dose, n = 6). The total incidence of unsolicited TEAEs remained consistent after each dose, with no reports of MAAEs, PIMMCs, or SAEs after the fourth dose. Reactogenicity reported in the present study was similar to that reported for the fourth dose of either BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273, with pain and fatigue the most reported solicited local and systemic reactogenicity events, respectively [17].

As expected, prior to boosting with a fourth dose at day 357, anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody titers (50 % inhibitory dose [ID50]) to the ancestral strain had gradually decreased after the first booster (third dose) on day 189, from 7992 (1165 IU50/mL) at day 217 to 2036 (297 IU50/mL) at day 357. Notably, the decrease in neutralizing antibody titers was more gradual than that seen after the primary series, and titers to the ancestral strain during this period remained similar to or higher than the titers reported in the pivotal phase III efficacy studies that were associated with ∼ 90 % efficacy [10], [11], [18]. After the fourth dose of NVX-CoV2373, neutralizing antibody titers (ID50) to the ancestral strain increased to 4367 (637 IU50/mL) by day 371. While this titer was somewhat lower than that seen after the third booster dose, antibody titers were only assessed 14 days after the fourth booster as compared with 28 days after the third dose, and it is possible that further increases would have been seen over the next 2 weeks. Consistent with other approved vaccines [19], lower antibody levels were noted for the BA.1 and BA.4/5 variants in comparison with the ancestral strain after the primary series but were markedly increased after the subsequent booster doses. In addition, as can be seen from both Fig. 3A and Fig. 3B, the magnitude of difference between the BA.1 or BA.4/5 variants and the ancestral strain diminished with each booster dose. The diminishing distance between ancestral and variant strains was recently demonstrated for this dataset using antigenic cartography [20].

Based on a recent publication that determined correlates of protection for the NVX-CoV2373 vaccine based on study data collected prior to the emergence of the Omicron variant [18], the antibody titers for the ancestral strain after the first booster remained well above the level associated with 92.8 % efficacy (neutralizing antibody titer of 1000 IU50/mL) for the full 6-months prior to the second booster dose administration. If these correlates were to be applied to the BA.1 and BA.5 Omicron variants, they would suggest that efficacy of at least 81.7% (pseudoneutralization titer of 100 IU50/mL) might be maintained for these variants during this same time frame. Although clinical trial data would give the most accurate assessment of the protective effect of the vaccine against emerging variants, the rapid evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus requires the reliance on correlative data, which serve as a benchmark by which to evaluate immune responses to new variants.

A similar immunogenicity pattern as the neutralization titers was seen with anti-S IgG levels. The anti-S IgG antibodies were similar to values reported for mRNA vaccines [19]. After conversion to similar units, we observed anti-S IgG geometric mean titer levels of 1896, 9629, and 7258 BAU/ml after doses 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Regev-Yochay et al noted IgG levels after vaccination with BNT162b2 of 950 BAU/ml 4 weeks after dose 2, 2102 BAU/ml 4 weeks after dose 3, and 2975 BAU/ml 2 weeks after dose 4. A fourth dose of mRNA-1273 resulted in IgG levels of 3502 BAU/ml 2 weeks after dose 4. These data support the use of NVX-CoV2373 and other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines as repeat boosters to restore immunogenicity against SARS-CoV-2.

Our study was subject to certain limitations. As these results are from an ongoing phase II study conducted with a limited sample size, the clinical efficacy of the booster dose was not evaluated, and assumptions concerning the efficacy of the booster doses for the ancestral strain and the Omicron variants are based on the derived correlates for the vaccine. Further, clinical correlates of protection may vary between emerging variants, particularly the immune evasive Omicron variant sublineages. This study also only evaluated serum antibody components of protection, and although these components correlate well with protection against infection [21], other components of immunity (e.g., T cells and memory B cells) that likely contribute to prevention of infection and of severe outcomes were not assessed in our study. Because this study occurred during an ongoing pandemic, a number of initially randomly assigned participants voluntarily discontinued the study between the primary series and the booster doses to receive already approved vaccines. As such, less than 50 % of the original study population received the fourth dose, which could introduce population bias. Future studies assessing the efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 after booster doses will be conducted as part of agreed post-marketing commitments with regulatory authorities (e.g., FDA and European Medicines Agency).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, despite the call for variant-specific vaccines, an increase in number of vaccine booster doses with NVX-CoV2373 enhances immunogenicity for the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain and its variants without a notable increase in reactogenicity. Therefore, these data suggest that further boosting with the ancestral sequence used in NVX-CoV2373 should retain meaningful utility in preventing variant virus-associated illness.

Funding

This work was supported by Novavax, Inc. and initially by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI®).

Data sharing

The trial protocol was a part of the peer-review process and will be included with the published manuscript; more information is available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04368988.

Authors’ contributions

RMM, KA, JSP, NP, GMG, and FD were involved in the study design, data collection and interpretation. SG and GC performed the statistical analyses. All authors reviewed, commented on, and approved this manuscript prior to submission for publication. The authors were not precluded from accessing data in the study, and they accept responsibility to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: All authors are contract or full-time employees of Novavax and as such receive a salary for their work.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the study participants who volunteered for this study. The authors would like to thank Lou Fries for his contributions to the development of the manuscript, and Andreana Robertson for biostatistical support of the study. Medical writing support was provided by Kelly Cameron, PhD, CMPP, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio company, supported by Novavax, Inc.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS-CoV-2 variant classifications and definitions; 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-classifications.html#anchor_1632154493691.

- 2.Willett B.J., Grove J., MacLean O.A., Wilkie C., De Lorenzo G., Furnon W., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7(8):1161–1179. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marks P. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA recommends inclusion of omicron BA.4/5 component for COVID-19 vaccine booster doses; 2022. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-recommends-inclusion-omicron-ba45-component-covid-19-vaccine-booster.

- 4.Flemming A. Are variant-specific vaccines warranted? Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(5):275. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00722-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore JP, Offit PA. FDA: Don't rush a move to change the Covid-19 vaccine composition; June 29, 2022. Available from: https://www.statnews.com/2022/06/29/fda-dont-rush-to-change-covid-19-vaccine-composition/.

- 6.Chung K.Y., Coyle E.M., Jani D., King L.R., Bhardwaj R., Fries L., et al. ISCOMATRIX adjuvant promotes epitope spreading and antibody affinity maturation of influenza A H7N9 virus like particle vaccine that correlate with virus neutralization in humans. Vaccine. 2015;33(32):3953–3962. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Portnoff A.D., Patel N., Massare M.J., Zhou H., Tian J.-H., Zhou B., et al. Influenza hemagglutinin nanoparticle vaccine elicits broadly neutralizing antibodies against structurally distinct domains of H3N2 HA. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8(1):99. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinde V., Fries L., Wu Y., Agrawal S., Cho I., Thomas D.N., et al. Improved titers against influenza drift variants with a nanoparticle vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2346–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1803554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith G., Liu Y., Flyer D., Massare M.J., Zhou B., Patel N., et al. Novel hemagglutinin nanoparticle influenza vaccine with Matrix-M adjuvant induces hemagglutination inhibition, neutralizing, and protective responses in ferrets against homologous and drifted A(H3N2) subtypes. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5366–5372. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunkle L.M., Kotloff K.L., Gay C.L., Anez G., Adelglass J.M., Barrat Hernandez A.Q., et al. Efficacy and safety of NVX-CoV2373 in adults in the United States and Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):531–543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heath P.T., Galiza E.P., Baxter D.N., Boffito M., Browne D., Burns F., et al. Safety and efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(13):1172–1183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Formica N., Mallory R., Albert G., Robinson M., Plested J.S., Cho I., et al. Different dose regimens of a SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein vaccine (NVX-CoV2373) in younger and older adults: A phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2021;18(10):e1003769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallory R.M., Formica N., Pfeiffer S., Wilkinson B., Marcheschi A., Albert G., et al. Safety and immunogenicity following a homologous booster dose of a SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein vaccine (NVX-CoV2373): a secondary analysis of a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(11):1565–1576. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00420-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: toxicity grading scale for healthy adult and adolescent volunteers enrolled in preventive vaccine clinical trials; September 2007. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/73679/download.

- 15.Huang Y., Borisov O., Kee J.J., Carpp L.N., Wrin T., Cai S., et al. Calibration of two validated SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assays for COVID-19 vaccine evaluation. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):23921. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03154-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madhi S.A., Moodley D., Hanley S., Archary M., Hoosain Z., Lalloo U., et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle vaccine in people living with and without HIV-1 infection: a randomised, controlled, phase 2A/2B trial. Lancet HIV. 2022;9(5):e309–e322. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munro A.P.S., Feng S., Janani L., Cornelius V., Aley P.K., Babbage G., et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines given as fourth-dose boosters following two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 or BNT162b2 and a third dose of BNT162b2 (COV-BOOST): a multicentre, blinded, phase 2, randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(8):1131–1141. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fong Y., Huang Y., Benkeser D., Carpp L.N., Anez G., Woo W., et al. Immune correlates analysis of the PREVENT-19 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):331. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35768-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regev-Yochay G., Gonen T., Gilboa M., Mandelboim M., Indenbaum V., Amit S., et al. Efficacy of a fourth dose of Covid-19 mRNA vaccine against omicron. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(14):1377–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2202542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alves K., Plested J.S., Galbiati S., Chau G., Cloney-Clark S., Zhu M., et al. Immunogenicity of a fourth homologous dose of NVX-CoV2373. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(9):857–859. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2215509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khoury D.S., Schlub T.E., Cromer D., Steain M., Fong Y., Gilbert P.B., et al. Correlates of protection, thresholds of protection, and immunobridging among persons with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29(2):381–388. doi: 10.3201/eid2902.221422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fong Y, McDermott AB, Benkeser D, Roels S, Stieh DJ, Vandebosch A, et al. Immune correlates analysis of a single Ad26.COV2.S dose in the ENSEMBLE COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. medRxiv; 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.