Abstract

Background

MDNA55 is an interleukin 4 receptor (IL4R)-targeting toxin in development for recurrent GBM, a universally fatal disease. IL4R is overexpressed in GBM as well as cells of the tumor microenvironment. High expression of IL4R is associated with poor clinical outcomes.

Methods

MDNA55-05 is an open-label, single-arm phase IIb study of MDNA55 in recurrent GBM (rGBM) patients with an aggressive form of GBM (de novo GBM, IDH wild-type, and nonresectable at recurrence) on their 1st or 2nd recurrence. MDNA55 was administered intratumorally as a single dose treatment (dose range of 18 to 240 ug) using convection-enhanced delivery (CED) with up to 4 stereo-tactically placed catheters. It was co-infused with a contrast agent (Gd-DTPA, Magnevist®) to assess distribution in and around the tumor margins. The flow rate of each catheter did not exceed 10μL/min to ensure that the infusion duration did not exceed 48 h. The primary endpoint was mOS, with secondary endpoints determining the effects of IL4R status on mOS and PFS.

Results

MDNA55 showed an acceptable safety profile at doses up to 240 μg. In all evaluable patients (n = 44) mOS was 11.64 months (80% one-sided CI 8.62, 15.02) and OS-12 was 46%. A subgroup (n = 32) consisting of IL4R High and IL4R Low patients treated with high-dose MDNA55 (>180 ug) showed the best benefit with mOS of 15 months, OS-12 of 55%. Based on mRANO criteria, tumor control was observed in 81% (26/32), including those patients who exhibited pseudo-progression (15/26).

Conclusions

MDNA55 demonstrated tumor control and promising survival and may benefit rGBM patients when treated at high-dose irrespective of IL4R expression level.

Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov NCT02858895.

Keywords: Convection Enhanced Delivery (CED), IL4R, immunotherapy, MDNA55, recurrent glioblastoma, treatment outcome

Key Points.

A single treatment with MDNA55 increased mOS by up to 50% and 12-month PFS by almost 100% compared to approved therapies“

Advanced CED (with planning software) for accurate catheter placement, and real-time imaging to visualize drug distribution.

Importance of the Study.

Despite considerable efforts over the past 4 decades, outcomes for glioblastoma patients continue to be poor with no standard of care available for rGBM. Approved therapies have shown median survival of only 6–9 months, a 1-year survival rate of 0%–10%, and 12-month PFS rate of 2%–10%. In addition, treatment of rGBM is constrained by the blood-brain barrier, its aggressive and infiltrative nature, and presence of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. These challenges are exacerbated in patients with primary de novo GBM, tumors not conducive to resection upon relapse, and contain wild-type IDH genes. Evaluation of MDNA55 in this poor prognostic group demonstrated a meaningful benefit after a single treatment resulting in ~50% increase in median survival and almost 100% increase in 12-month PFS when compared to approved therapies. MDNA55 presents a promising treatment option for rGBM patients who otherwise rapidly succumb to this disease.

Recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM) is a condition with bleak outlook as treatment options are very limited with no universally held standard of care.1,2 Resection is not widely adopted nor regarded as effective since most patients (~70%–75%) are not candidates for repeat gross total resection at recurrence, resulting in a large unmet need for this patient population.3,4 In addition, rGBM treatment is constrained by the blood-brain barrier (BBB), its aggressive and infiltrative nature, and the presence of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. These challenges are exacerbated in some patients, including those with the initial diagnosis of primary de novo GBM,5 tumors that are not conducive to gross total resection upon relapse,1 and presence of wild-type isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) gene.6

FDA-approved treatment options resulting in prolongation of life have not emerged over the last 25 years. Median overall survival (mOS) following recurrence is 6 to 9 months and 12-month progression-free survival (PFS) rate is 2%–10%.7–12 The most recently approved agent bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agent, showed a modest improvement in PFS with the maintenance of the quality of life. However, neither single agent nor combination trials have led to improved survival.8,11,13–16 Recently, a phase III trial of nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) compared to bevacizumab also failed to show survival benefit.17

MDNA55 is an immunotoxin that targets cells expressing the Interleukin-4 receptor (IL4R) in GBM and certain cells of the tumor microenvironment. High IL4R expression is associated with poor outcomes in GBM18,19 and recent studies have shown that IL4R expression is maintained at the same or higher level upon recurrence.20 IL4R over-expression has been demonstrated in approximately 75% of cancer biopsies and autopsy samples from adult and pediatric GBM,21 and in tumor-infiltrating macrophages and MDSCs.22,23 Higher levels of IL4R expression inhibit T-cell proliferation in an IL4R-dependent manner.22

MDNA55 consists of an engineered circularly permuted Interleukin-4 (cpIL4) fused to a truncated and tailored sequence of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A (PE) via 5 amino acid linker.24 Once bound to IL4R, the MDNA55 complex is endocytosed, followed by cleavage and activation by furin-like proteases found in high concentrations in the endosome of cancer cells.25,26 The catalytic domain of PE is then released into the cytosol where it induces cell death via ADP-ribosylation of Elongation Factor-2 (EF-2) and apoptosis through caspase activation.27 Cells that do not express the IL4R target do not bind MDNA55 and are not subject to PE-mediated effects.28,29

MDNA55 was investigated as a single agent in a phase IIb trial in patients with recurrent de novo GBM using Convection-Enhanced Delivery (CED) to overcome the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB). CED is a minimally invasive procedure similar to routine biopsy that minimizes systemic exposure, while the image-guided technique enhances the exposure of active drugs throughout the target region. Earlier studies of MDNA5530 utilized 1st generation (ie, non-optimized) CED where MDNA55 was delivered using large uniform diameter ventricular catheters without the use of planning software for surgical catheter placement. The current study employs 2nd generation CED technology consisting of planning software for accurate catheter placement, real-time image-guided CED with a surrogate tracer to visualize drug distribution and use of small diameter stepped designed catheters intended to minimize drug leakage and back-flow.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a single-arm, non-randomized, open-label, multicenter study designed to test the hypothesis that mOS (primary objective) is improved to a clinically significant degree with MDNA55 administered via CED, as compared to currently available treatments for rGBM. Further details on the study design are presented in section A of Supplementary Methods.

Study Population

Eligible patients included male and female patients ≥18 years of age with histologically confirmed primary (de novo) GBM that had recurred or progressed (first or second recurrence, per standard RANO criteria) after treatment(s) including surgery and radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy (according to local practice; Stupp protocol) and following discontinuation of any previous standard or investigational lines of therapy. Patients must have had a life expectancy > 12 weeks, Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥ 70, tumor with a contrast-enhancing diameter of ≥ 1cm × ≥1cm (minimum) to 4cm (maximum) in any direction, by pre-interventional MRI within 14 days of planned treatment and had no features that made the tumor a poor target for CED (eg, significant liquefaction or geometric features or location known to cause the failure of CED due to impact on drug distribution). Patients had to have adequate bone marrow, liver, and kidney functions. Patients on steroids had to be on a stable or decreasing dose for at least 5 days prior to screening imaging. Patients with known mutations in either the IDH1 or IDH2 gene or a history of allergy to gadolinium contrast agent were excluded. Prior investigational or anti-VEGF therapies were permitted following suitable washout.

MDNA55 Dosing and Administration

Patients underwent stereotactic surgery for placement of 1 to 4 infusion catheters followed by an intra- and peritumoral infusion of MDNA55 via CED. One subject underwent catheter placement but did not receive MDNA55 treatment. Patients received a single treatment at concentrations ranging from 1.5 to 9.0µg/mL and volumes of up to 66mL with a pre-determined total dose ranging from 18 to 240µg, which is less than or equal to the established MTD of 240µg.30 The flow rate of each catheter did not exceed 10μL/min and was established to ensure that the infusion duration did not exceed 48 h. Details on the selection of dose for each subject are presented in section B of Supplementary Methods.

All sites were required to use the Brainlab iPlan® Flow planning software (version 3.0.6), Brainlab stepped-designed catheters, and VarioGuideTM frameless image-guided stereotactic system to generate a pretreatment plan for placement of catheters according to specified placement guidelines (see section C of Supplementary Methods). Co-infusion of a contrast agent (gadolinium diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid [Gd DTPA], Magnevist®) was applied to assess infusate distribution as well as to determine suitability of the iPlan software, Varioguide, Brainlab catheter, and catheter placement guidelines to deliver MDNA55.

Study Assessments

Post-treatment follow-up assessment of safety was performed 14 (±3) days after treatment. Thereafter, safety and efficacy assessments were performed at 30, 60, 90, and 120 (±7) days after treatment and approximately every 8 weeks thereafter until 360 days of active follow-up was completed.

For pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis, samples were collected at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h post infusion, and on Day 14; plasma concentration was measured using an MSD® ligand-binding method. To assess anti-drug antibodies (ADA) titers and the presence of neutralizing antibody (NAb), serum samples were collected at screening (baseline) and at Days 14, 30, 120, 240/270, and 360 or at early termination. ADA titers were measured using an MSD® immunoassay and NAbs were determined using a cell-based radioactive assay utilizing Daudi B-lymphoblast cell line (ATCC-CCL-213).

Patients who completed Day 360 assessment without the progressive disease (PD) or discontinued early without PD continued to be followed for disease status until progression, where possible. After progression (on study or during post-study follow-up), patients continued to be followed where possible, for survival until death (or termination of data collection by the Sponsor or withdrawal of consent by the subject).

The expected duration of study participation for each subject was up to 12.5 months, including up to 14 days of screening, up to 3 days planning period, and a 12-month follow-up period relative to the day of catheter placement/start of infusion (designated as Day 0).

Response Assessment

All patients had MR images acquired at baseline and at follow-up visits according to the international standardized brain tumor imaging protocol in Ellingson et al. (2015) including T2-weighted, T2-weighted FLAIR, diffusion-weighted images, and parameter matched, 1–1.5 mm isotropic 3D T1-weighted scans before and following injection of Gd-DTPA. Advanced imaging such as perfusion MRI and Treatment Response Assessment Maps (TRAMs) were also acquired for some patients.

Since an extended duration of pseudo-progression (PsP) was observed in the phase I study,31,32 assessment of response in the current study was performed using the modified RANO (mRANO) criteria33 as it allowed for continuation of study following initial evidence of radiographic progression to confirm either true progression or PsP (see section F of Supplementary Methods).

IL4 Receptor Expression Analysis

Retrospective analysis of IL4R expression using archival tumor tissue from initial GBM diagnosis and/or tumor tissue sample collected at recurrence was conducted using a validated immunohistochemistry-based assay at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) compliant reference laboratory. H-score determination method is explained in section E of Supplementary Methods.

A positivity cutoff of H-score > 60 was determined to provide the most predictive value for IL4R status in relation to efficacy endpoints. Applying this cutoff, 2 subpopulations were identified: IL4R High = H-score > 60; IL4R Low = H-score ≤ 60.

Statistical Analysis

Assessment of safety was based on all patients (safety population; N = 47). Evaluation of survival-related efficacy endpoints (OS and effect of IL4R status on OS) was based on the Intent to Treat Population (ITT; N = 47) and also on those who received any amount of MDNA55 and had no major protocol violations (Per Protocol Population, PP; N = 44). Determination of response-related secondary efficacy endpoints is based on modified intent to treat population (mITT; N = 41) comprising of patients with adequate imaging (at least 1 post-treatment scan) and clinical information. Further details on the study endpoints are presented in section D of Supplementary Methods. All statistical evaluations were performed using SAS® Version 9.3 or above (SAS® Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Patient Characteristics and Disposition

A total of 47 patients were enrolled in the study in the period between March 23, 2017 to September 12, 2019 at 8 active clinical sites in the United States and 1 site in Poland. As of the study censor date (October 31, 2019), 11 patients were alive and continued to be followed for survival.

Baseline disease characteristics are summarized in Table 1 for the various analysis populations. Among the ITT population, median age was 56 years (range: 34 to 78); 30 patients (63.8%) were male and 17 (36.2%) were female. Median time between initial diagnosis and the start of treatment was 12.72 months (range: 5.15 to 44.23 months); the overall mean maximal tumor diameter at baseline was 30.8mm. All 47 (100.0%) patients underwent prior surgery at initial diagnosis and were not suitable for tumor resection at relapse (ie, first or second relapse). All but 1 subject (98%) received prior temozolomide treatment and all but 1 subject (98%) received prior radiotherapy. Thirteen (27.7%) patients had relapsed following failure on an alternate investigational therapy prior to enrollment. Approximately half (49.0% of patients) had a KPS score of ≤ 80. Thirty-seven (78.7%) patients had 1 relapse and 10 (21.3%) patients had 2 relapses at the time of enrollment. MGMT gene promoter methylation, being a strong indicator for better prognosis in GBM, was observed only in 18 (38.3%) patients. Overall, 24 (51.1%) patients had unmethylated MGMT status. Five (10.6%) patients had no MGMT data available. With respect to IL4R expression, 23 patients had an H-score > 60 (ie, High expression) and 19 had an H-score ≤ 60 (ie, Low expression) with 5 unknowns due to lack of tumor tissues.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics for MDNA55-05 Analysis Populations

| Baseline Characteristics | ITT Population (N = 47) | PP Population (N = 44) | mITT Population (N = 41) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male, n (%) | 30 (64%) | 27 (61%) | 25 (61%) |

| Female, n (%) | 17 (36%) | 17 (39%) | 16 (39%) |

| Age | |||

| Median (Range) | 56 (34–78) | 55 (34–77) | 55 (34–77) |

| Mean (StDev) | 57 (± 11.8) | 56 (± 11.8) | 56 (± 11.7) |

| KPS, n (%) | |||

| 70 and 80 | 23 (49%) | 22 (50%) | 19 (46%) |

| and 100 | 24 (51%) | 22 (50%) | 22 (54%) |

| IDH status | |||

| Wild type | 38 (81%) | 37 (84%) | 35 (85%) |

| Mutated | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unknown | 9 (19%) | 7 (16%) | 6 (15%) |

| MGMT status | |||

| Pos (methylated) | 18 (38%) | 17 (39%) | 15 (37%) |

| Neg (unmethylated) | 24 (51%) | 23 (52%) | 22 (54%) |

| Unknown | 5 (11%) | 4 (9%) | 4 (10%) |

| IL4 receptor status | |||

| High (H-score > 60), n (%) | 23 (49%) | 21 (48%) | 21 (51%) |

| Low (H-score ≤ 60), n (%) | 19 (40%) | 19 (43%) | 16 (39%) |

| Unknown | 5 (11%) | 4 (9%) | 4 (10%) |

| Max tumor dimension, mm | |||

| Median (Range) | 29.6 (7.8 – 58.5) | 29.6 (7.8 – 58.5) | 29.7 (12.0 – 8.5) |

| Mean (St Dev) | 30.8 (± 11.08) | 30.1 (± 10.8) | 31.0 (± 10.5) |

| Tumor location | |||

| Parietal | 15 (32%) | 15 (34%) | 14 (34%) |

| Frontal | 14 (30%) | 12 (27%) | 11 (27%) |

| Temporal | 10 (21%) | 9 (21%) | 9 (22%) |

| Other | 8 (17%) | 8 (18%) | 7 (17%) |

| Extent of tumor resection at diagnosis | |||

| Total resection | 39 (83%) | 36 (82%) | 33 (80%) |

| Partial resection | 8 (17%) | 8 (18%) | 8 (20%) |

| Time to 1st relapse, months | |||

| Median (Range) | 10.9 (2.6 – 36.4) | 11.3 (4.7 – 36.4) | 11.1 (4.7 – 36.4) |

| Mean (St Dev) | 13.0 (± 7.7) | 13.1 (± 7.5) | 13.3 (± 7.5) |

| Number of prior relapses, n (%): | |||

| 1 | 37 (79%) | 35 (80%) | 33 (80%) |

| 2 | 10 (21%) | 9 (20%) | 8 (20%) |

| Steroid use at baseline | |||

| None | 27 (57%) | 27 (61%) | 25 (61%) |

| ≤ 4 mg/day | 14 (30%) | 14 (32%) | 14 (34%) |

| > 4mg/day | 5 (11%) | 3 (7%) | 2 (5%) |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prior treatment, n (%) | |||

| Surgery | 47 (100%) | 44 (100%) | 41 (100%) |

| Temozolomide | 46 (98%) | 43 (98%) | 40 (98%) |

| Radiation | 46 (98%) | 43 (98%) | 40 (98%) |

| Exp Therapy | 13 (28%) | 12 (27%) | 11 (27%) |

Abbreviations: ITT = intent to treat, PP = per protocol, mITT = modified intent to treat, N = sample size, KPS = Karnofsky performance status, IDH = isocitrate dehydrogenase, MGMT = O6-methylguanine-methyltransferase, IL4R = interleukin 4 receptor.

MDNA55 Dosing

Volume and concentration were adjusted to optimize delivery to the tumor based on infusate distribution and tolerability data obtained in real-time from previous patients in this study under ongoing guidance by the Safety Review Committee. During the course of the study, 4 drug concentrations (1.5, 3.0, 6.0, and 9.0 µg/mL) were employed with the volume of administration adjusted according to tumor size. Median volume of infusion was 30 mL (range: 12 to 66 mL) for a median duration of 26.57 h (range: 15.46 to 57.21 h) at an adjusted median flow rate of 1.095 mL/h (0.58 to 2.83 mL/h). Median total dose infused was 180 µg (range: 18.0 to 240.3 µg). Median number of catheters was 2 (range: 1–4 catheters). Nearly all patients received 100% of the planned total dose and infusion volume (median: 100% [range: 88.33% to 100.42%]).

MDNA55 Distribution and Tumor Coverage

A semi-automatic segmentation feature of iPlan Flow was used for volumetric assessment. The volume of Gd-DTPA distribution was analyzed based on pre-and post-CED 3D T1-weighted MRI using a customized subtraction algorithm. Based on the tumor volume assessment, Gd-DTPA distribution inside the tumor was considered as coverage. Overall median tumor coverage achieved was 52.66% (range: 0 to 97.8%); median tumor coverage including a 1 cm peritumoral margin was 55.14% (range: 5.4% to 95.2%), and median tumor coverage including a 2 cm peritumoral margin was 37.22% (range: 2.2% to 82.9%). Median Volume of distribution (Vd)/Volume of infusion (Vi) ratio was 1.35 (range: 0.1 to 4.8).

Safety

The most common Adverse Events (AEs) in the total subject population were seizure (N = 20, 42.6%), fatigue (N = 19, 40.4%), headache (N = 18, 38.3%), and muscular weakness (N = 15, 31.9%) (Table G1 in section G of Supplementary Methods). Of the 47 patients, 32 (68.1%) had AEs considered by the investigator to be at least possibly related to the study drug and/or infusion procedure (Table G2 in section G of Supplementary Methods). Overall, the incidence of AEs between the dose groups was similar and there was no apparent dose-dependent effect. Most frequent possibly related/related AEs were seizure (N = 10, 21.3%), fatigue (N = 9, 19.1%), headache (N = 8, 17.0%), and pyramidal tract syndrome (N = 8; 17.0%). Eighteen of 47 patients (38.3%) had a history of seizures prior to enrollment.

AEs were also evaluated based on volume of infusion and total dose administered. In both cases, the incidence of AEs between groups above and below the median was comparable with no clear effect of volume of infusion or total dose administered.

Eight (8) patients experienced Grade 5 AEs, six (6) of which were unrelated to study drug or/ infusion procedure (Table G3 in section G of Supplementary Methods). One subject experienced an AE of a cerebral hemorrhage after completing infusion and immediately after removal of the catheters and died 14 days post-treatment. This AE was thought to be related to the catheter removal procedure and was therefore considered to be possibly related to the study drug or the CED procedure. However, the underlying nature of the disease or infectious complications is alternate consideration for this causality.

PK and ADA

Similar to previous MDNA55 trials, pharmacokinetic results were well below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) at all time points, suggesting that intact MDNA55 did not enter the systemic circulation at measurable levels following intracranial infusion.

Nineteen of 47 patients (40.4%) were confirmed positive for ADA during the study (2 were positive at screening, indicating they were potentially exposed to pseudomonas infection) and all 19 patients had positive samples post-treatment. Sixteen patients tested positive for neutralizing antibodies (Nabs) where the inhibition of MDNA55 cytotoxic activity ranged between 6.2% to 101.3%. However, these effects observed in plasma may not be representative of effects within the tumor beyond the blood-brain barrier with no clear implications for repeated dosing.

Efficacy

Overall survival.

With a single treatment of MDNA55, the mOS in the ITT population was 10.2 months (one-sided 80% CI: 8.39, 12.75) and in the PP population, the mOS was 11.64 months (one-sided 80% CI: 8.62, 15.02). As the lower limit of the CI did not include 8.0 months in both ITT (primary analysis) and PP Populations (supportive analysis), the null hypothesis was rejected using a single-sample one-sided log-rank test at a one-sided 10% significance level and therefore the primary endpoint was met. Overall survival at 12 months was 43% (95% CI: 29%–57%) in the ITT population and 46% (95% CI: 31%–60%) in the PP population.

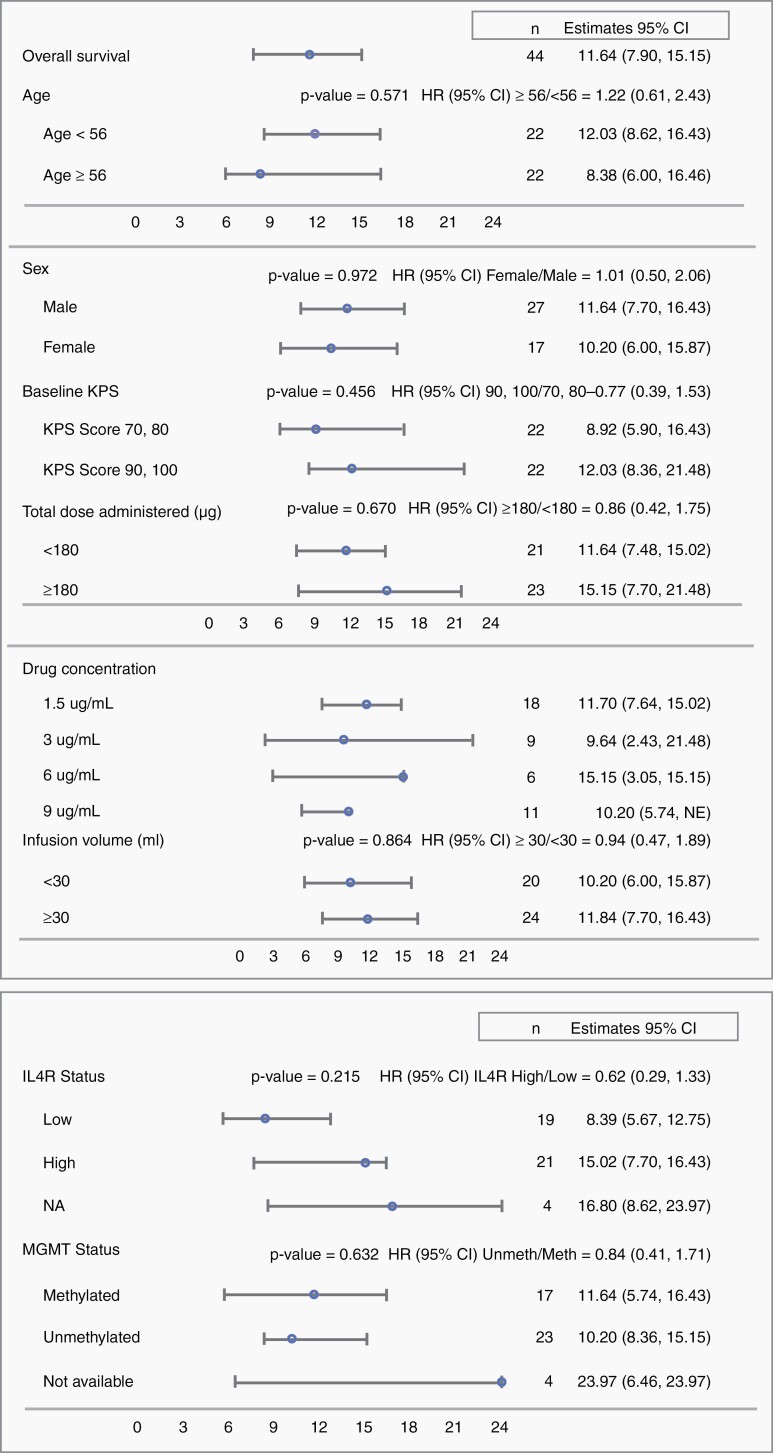

Exploratory subgroup analyses were conducted on survival in the PP population for various prognostic and treatment parameters. Results are presented in a Forest Plot (Figure 1). Patients with unmethylated MGMT promoters treated with MDNA55 showed a similar survival outcome compared with those with methylated MGMT promoters (mOS was 10.20 vs. 11.64 months; P = .632. OS-12 was 46% vs. 41%, respectively). There was also no significant difference in survival based on the total dose of MDNA55 administered (either above or below the median dose of 180 µg) or the volume infused (above or below the median infusion volume of 30 mL).

Figure 1.

Forest plot for median overall survival based on various prognostic and treatment parameters (PP Population).Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard’s ratio, IL4R = interleukin 4 receptor, N = sample size, KPS = Karnofsky performance status, IDH = isocitrate dehydrogenase, MGMT = O6-methylguanine-methyltransferase, IL4R = interleukin 4 receptor.

Dose-effect relationship of MDNA55 dose by IL4R status

OS based on IL4R expression of the primary tumor was evaluated as a secondary endpoint in the study. IL4R High patients showed an mOS of 15.02 months and IL4R Low patients showed an mOS of 8.4 months, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .215) (Figure 1). OS-12 was 57% versus 33%, respectively.

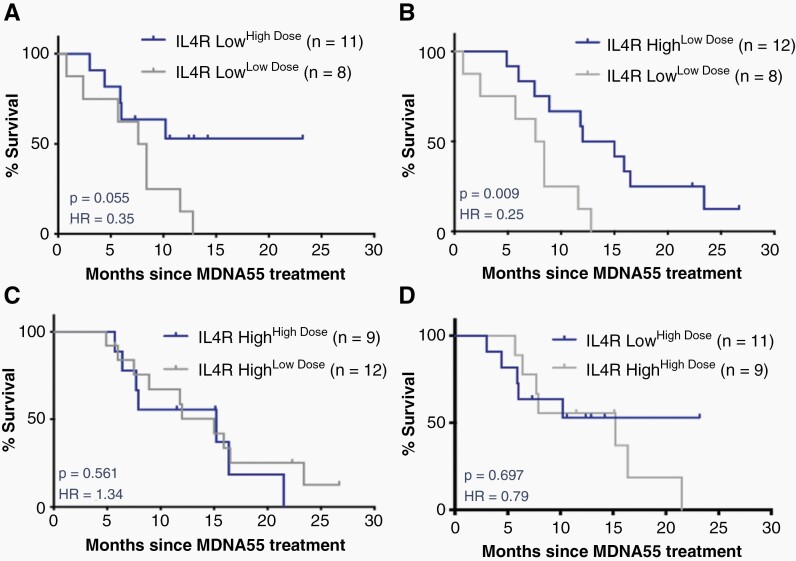

Further analysis of OS evaluating the relationship between MDNA55 dose and IL4R status identified a subpopulation in the IL4R Low group that demonstrated increased survival—those receiving high doses (≥180µg) of MDNA55 (designated as the IL4R LowHD population). These patients demonstrated an OS-12 of 53% (Table 2 and Figure 2) despite not reaching the mOS at the time of study censor. This was roughly equivalent to the IL4R High group receiving any dose (OS-12 of 56% and 58%). In contrast, patients in the IL4R Low group receiving low doses (<180µg; designated as the IL4R LowLD population) demonstrated an mOS of 8.0 months, no different from the literature-derived null assumption of OS for the study. Combination of the IL4R High group (receiving any dose) and the IL4R LowHD groups yielded an mOS of 15.0 months and OS-12 of 55% (Table 2 and Figure 2). These data suggest that MDNA55 treatment may benefit rGBM patients if administered at a high dose irrespective of IL4R expression level.

Table 2.

Comparison of Overall Survival by IL4R Group and MDNA55 Dose

| IL4R Groups and MDNA55 Dose |

N | Median OS (95% CI) | OS-12 |

P-value HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL4R low HD | 11 | NR (4.39, NR) | 53% | .055 0.35 (0.11, 1.07) |

| IL4R low LD | 8 | 8.00 (0.82, 11.64) | 13% | |

| IL4R high LD | 12 | 13.52 (6.00, 23.38) | 58% | .009 0.25 (0.08, 0.76) |

| IL4R low LD | 8 | 8.00 (0.82, 11.64) | 13% | |

| IL4R high LD | 12 | 13.52 (6.00, 23.38) | 58% | .561 1.34 (0.49, 3.65) |

| IL4R high HD | 9 | 15.15 (5.74, NR) | 56% | |

| IL4R low HD | 11 | NR (4.39, NR) | 53% | .697 0.79 (0.25, 2.54) |

| IL4R high HD | 9 | 15.15 (5.74, NR) | 56% | |

| IL4R high + IL4R Low HD | 32 | 15.02 (7.70, 16.43) | 55% | .005 0.30 (0.13, 0.73) |

| IL4R low LD | 8 | 8.00 (0.82, 11.64) | 13% |

Abbreviations: OS = overall survival, CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard’s ratio, IL4R = interleukin 4 receptor, LD = Low Dose, HD = High Dose, N = sample size, NR = not reached, OS-12 = overall survival at 12 months.

Figure 2.

Survival curves depicting the dose-effect relationship between MDNA55 dose and IL4R status. (A) IL4R Low group treated with high and low-dose MDNA55. (B) IL4R low and high groups treated with low-dose MDNA55. (C) IL4R high group treated with high and low-dose MDNA55. (D) IL4R low and high groups treated with high-dose MDNA55.

Tumor Control and Progression-Free Survival

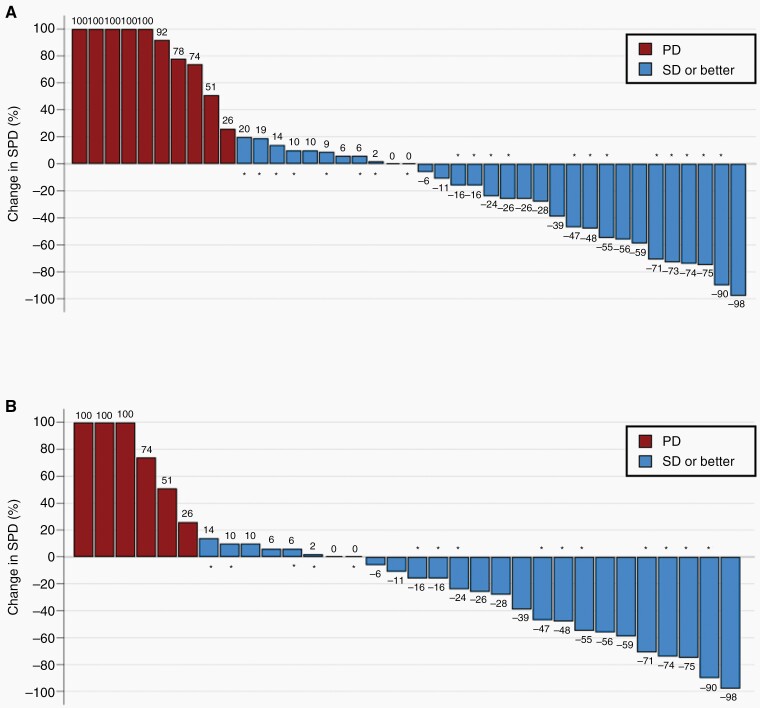

In total, 1 of 41 evaluable patients had an objective response (ORR = 2.4%), which continued to shrink for more than 358 days until study closure. Twenty of the 41 (48.8%) evaluable patients exhibited PsP on follow-up imaging. Tumor shrinkage or stabilization relative to pretreatment baseline using mRANO criteria was observed in 31 of 41 patients (Figure 3A), with 1 patient exhibiting evidence of a durable CR following initial radiographic changes consistent with PsP, resulting in a total Tumor Control Rate (TCR) of 75.6%. In the population comprised of IL4R High + IL4R LowHD patients (Figure 3B), the TCR was 81%. PFS based on radiologic-only assessment using mRANO criteria demonstrated a median PFS of 3.61 months (95% CI: 2.62, 7.70). PFS-6 was 33%, PFS-9 was 27%, and PFS-12 was 27%.

Figure 3.

Waterfall Plot of Best Tumor Response Assessed by Modified RANO (mRANO). Bars represent best response in % change in Sum of Product Diameters (SPD) on the basis of contrast-enhanced MRI compared to pretreatment baseline. Shown are the best tumor response in (A) all evaluable subjects, and (B) Subjects in the IL4R High + IL4R LowHigh Dose sub-population. Asterisks represent subjects that experienced initial pseudo-progression on the first radiographic time point.

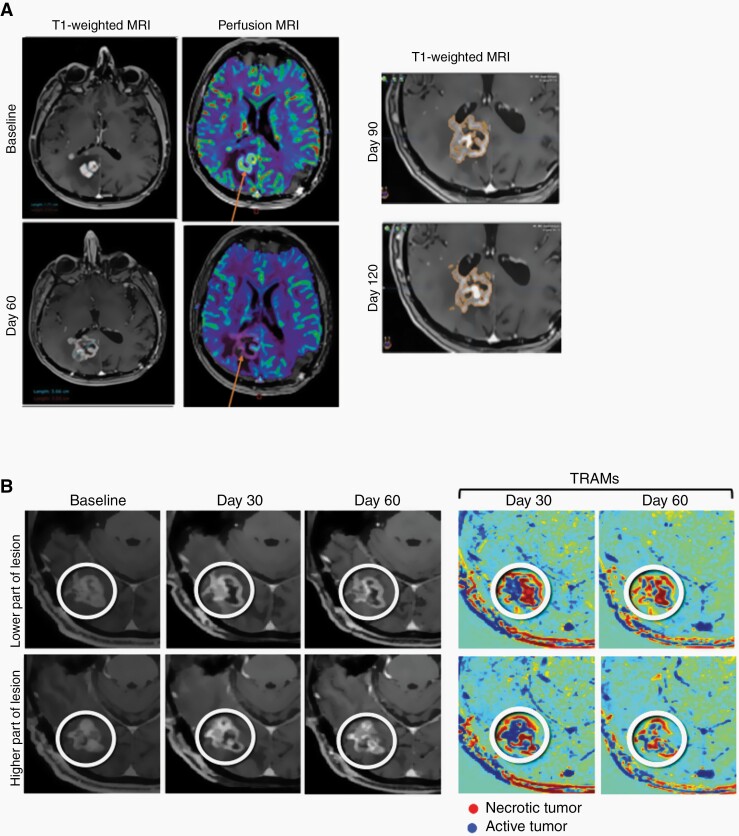

Case studies shown in Figure 4 provide examples of delayed onset response observed after pseudo-progression and confirmed by advanced imaging techniques (perfusion MRI or TRAMs). Figure 4A shows a subject with an increase in contrast enhancement in T1-weighted MRI at Day 60 which was suggestive of progression, however, decrease blood uptake by perfusion MRI suggests decreased active tumor and occurrence of pseudo-progression. Figure 4B shows a subject with increased contrast enhancement at Days 30 and 60, however, TRAMs revealed improvement occurring in the lesion area, showing mostly red (necrotic) regions at Day 60.

Figure 4.

Delayed Onset Response After Pseudo-Progression. (A) An increase in contrast enhancement in T1-weighted MRI at Day 60 is suggestive of progression, however, decrease blood uptake by perfusion MRI (arrows) indicates decreased active tumor and suggests pseudo-progression. Follow-up T1-weighted MRI at 90 and 120 days confirm pseudo-progression. (B) TRAMs show improvement occurring between Day 30 and Day 60 in the lesion area, showing mostly red (necrotic) regions at Day 60.

Discussion

Currently, treatment options following the recurrence of primary GBM are very limited and not effective. MDNA55 is a rationally designed targeted therapy with the potential to extend the survival of patients with rGBM. The treatment strategy of this study consisted of intra-tumoral and peritumoral administration of MDNA55 by-passing the BBB using an advanced CED delivery technique thereby targeting the bulk tumor in situ. Data from the MDNA55-05 study showed that a single administration of MDNA55 resulted in mOS of up to 15 months and OS-12 of 55% in a population where median survival with approved therapies remained at 6–9 months and 1-year survival rate is less than 35%.7–12

Though MDNA55 showed promising survival over approved therapies, the single-arm (non-randomized) study design and small number of patients are limiting factors. Recognizing these limitations of the study and challenges associated with the use of historical controls from published data as a comparator, the survival results of this study were also assessed relative to a well-balanced propensity-matched external control arm (ECA). The analysis concluded that the survival benefit observed in the study was attributed to MDNA55.34–36 We have included the ECA principally to draw attention to this approach for study design given we have recently been approved by the FDA to use this in a registration trial. We believe that this is a significant opportunity for the neuro-oncology community. However, we recognize that these analyses were not part of the prespecified statistical analysis plan and therefore should be interpreted with some caution.

The mOS benefit of MDNA55 treatment is encouraging, particularly in a population that is known to have a poor prognosis. Moreover, unmethylated MGMT gene promoter, 1 predictive factor of poor prognosis in rGBM, was observed in more than 50% of the MDNA55 study population. Overall survival of this group was similar to that of patients with methylated MGMT promoters, suggesting no association between MGMT gene methylation and MDNA55 activity and a potential benefit to this group which comprises nearly 40% to 50% of the GBM population.37

Overall, the safety profile in this study was consistent with previous MDNA55 studies and no new safety findings were observed. Drug-related AEs were primarily neurological or an exacerbation of preexisting neurological conditions related to the primary disease of GBM. The CED procedure was well tolerated with only 2 patients having to discontinue infusion due to AEs related to procedure. One subject experienced an AE of cerebral hemorrhage shortly after completion of infusion and immediately after removal of the catheters and died 14 days later. This AE was thought to be related to catheter removal and was therefore considered to be possibly related to the study drug or CED procedure. However, the underlying nature of the disease or infectious complications is alternate consideration for this causality.

Patients treated with MDNA55 developed anti-drug antibodies, including neutralizing antibodies. These data suggested that there was low systemic exposure of MDNA55 that was sufficient to elicit an immune response. However, ovalbumin injection into the brain or CSF of rats has resulted in immunogenicity related to events occurring with the CNS38 rather than a result of systemic exposure. This suggests that systemic exposure to MDNA55 may not be necessary to generate an immune response and anti-drug antibody generation.

Standard RANO criteria are the currently accepted benchmark for response assessment in rGBM, however, it was determined not to be the most appropriate tool for determining the therapeutic benefit of MDNA55 due to the high incidence of pseudo-progression (48.8%) following treatment. This confounded the interpretation by standard RANO of objective responses for estimating PFS, as pseudo-progression in these patients could falsely suggest early failure despite a trend toward longer survival.39 The mRANO criteria allow for the continuation of therapy during initial evidence of radiographic progression to distinguish between true tumor growth from possible PsP.40 It also allows for use of the initial radiological scan documenting PsP-related “progression” as a new reference baseline, to objectively define and document the degree of possible PsP events. In this study, tumor control was observed in a number of patients, particularly after a transient increase in the size of the area of enhancement on imaging at the earlier time points.

The engineering of MDNA55 to target the IL4R on tumor cells suggests that patients with high IL4R expression would benefit most from MDNA55 treatment due to the increased probability of toxin exposure. In the MDNA55-05 study, it was observed that the effect of IL4R expression on overall survival could be differentiated when the drug dose was low in contrast to when the drug dose was high. Though the IL4R subgroup analysis was not a pre-specified hypothesis and not statistically powered, this observation is consistent with preclinical studies showing that tumors expressing low levels of the IL4R do respond well to higher doses of MDNA55.41 These subgroup results are to be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and will be validated in the pivotal trial. Conversely, the apparent lower level of the biological effect of MDNA55 at low doses may be attributed to a requirement for higher IL4R expression when drug exposure is low. In patients with high IL4R expression, MDNA55 dose did not have much effect. This could be because once a threshold number of IL4Rs on the target tumor cell bind to MDNA55 and deliver the toxic payload causing cell death, any further increase in dose does not have any incremental effect on the fate of tumor cells.42

CED is a minimally invasive procedure, similar to a biopsy, that improves drug delivery by utilizing bulk flow, or fluid convection, established as a result of a pressure rather than a concentration gradient.43 As such, it offers markedly improved distribution of infused therapeutics within the CNS compared to direct injection or via drug-eluting polymers, both of which depend on diffusion for parenchymal distribution. Additionally, CED obviates the challenges of agents crossing the BBB while minimizing systemic exposure and toxicity.43–45 In previous studies of MDNA55, it was not possible to assess the distribution in real-time which resulted in leakage and poor tumor coverage. This current study employs state-of-the-art CED techniques with planning software for accurate catheter placement, and real-time image guidance with a surrogate tracer to visualize drug distribution46,47 resulting in much better drug distribution (~2X the % tumor coverage) compared to earlier studies using 1st generation CED technique.48,49

In conclusion, MDNA55 treatment showed promising survival compared to currently approved therapies and exhibited an acceptable risk-benefit profile in a population expected to have a poor prognosis. Single treatment with MDNA55 increased mOS by up to 50% and 12-month PFS by almost 100% when compared to approved therapies. Combining targeted treatment and advanced drug delivery techniques employed in this study provides opportunities to potentially deliver substantive benefit in patients with rGBM and to explore the efficacy of MDNA55 in a pivotal trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and families, and the study teams involved in the study, for making this trial possible. We would also like to dedicate this manuscript to Dr. Dina Randazzo, Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery and Neurology at Duke University, and a key contributor to the MDNA55-05 study. Dr. Randazzo was a respected and admired neuro-oncologist whose life’s work was aimed at understanding and treating GBM. She was adored by her patients and has touched so many people with her dedication and passion for finding a cure for cancer.

Contributor Information

John H Sampson, Duke University Medical Center, Department of Neurosurgery, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Achal Singh Achrol, Loma Linda University Medical Center, Department of Neurosurgery, Loma Linda, California, USA.

Manish K Aghi, University of California San Francisco, Department of Neurological Surgery, San Francisco, California, USA.

Krystof Bankiewicz, Ohio State University College of Medicine, Department of Neurological Surgery, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Martin Bexon, Medicenna BioPharma Inc, Houston, Texas, USA.

Steven Brem, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Department of Neurosurgery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Andrew Brenner, University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Chandtip Chandhasin, Medicenna BioPharma Inc, Houston, Texas, USA.

Sajeel Chowdhary, Boca Raton Regional Hospital, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.

Melissa Coello, Medicenna BioPharma Inc, Houston, Texas, USA.

Benjamin M Ellingson, University of California, Los Angeles, Brain Tumor Imaging Laboratory (BTIL), California, USA.

John R Floyd, University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Seunggu Han, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Santosh Kesari, Pacific Neurosciences Institute, Santa Monica, California, USA.

Yael Mardor, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel .

Fahar Merchant, Medicenna Therapeutics Inc, Toronto, Canada .

Nina Merchant, Medicenna Therapeutics Inc, Toronto, Canada .

Dina Randazzo, Duke University Medical Center, Department of Neurosurgery, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Michael Vogelbaum, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Department of Neuro-Oncology, Tampa, Florida, USA.

Frank Vrionis, Boca Raton Regional Hospital, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.

Eva Wembacher-Schroeder, Brainlab AG, Munich, Germany.

Miroslaw Zabek, Mazovian Brodnowski Hospital, Warsaw, Poland.

Nicholas Butowski, University of California San Francisco, Department of Neurological Surgery, San Francisco, California, USA.

Funding

This study was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant DP150031 and Medicenna Therapeutics Corp. Medicenna BioPharma Inc. and Medicenna Therapeutics Inc. are wholly owned subsidiaries of Medicenna Therapeutics Corp.

Conflict of interest statement. John Sampson: Director and paid consultant for Medicenna; Paid advisor for Creosalus, Alcyone Therapeutics, Immunomic Therapeutics, and Shorla Pharma. Achal Singh Achrol: None. Manish K. Aghi: None. Krystof Bankiewicz: Paid consultant for Medicenna. Martin Bexon: Employed by Medicenna. Steven Brem: Advisor for Novocure, Northwest Biotherapeutics, and Tocagen. Andrew Brenner: None. Chandtip Chandhasin: Employed by Medicenna. Sajeel Chowdhary: None. Melissa Coello: Employed by Medicenna. Benjamin Ellingson: Paid advisor for Medicenna; Paid advisor for MedQIA, Neosoma, Agios, Siemens, Janssen, Imaging Endpoints, Kazia, VBL, Oncoceutics, Boston Biomedical Inc (BBI), and ImmunoGenesis. Grant funding received from Siemens, Agios, and Janssen. John R. Floyd: None. Seunggu Han: None. Santosh Kesari: Paid advisor and grant funding received from Medicenna. Yael Mardor: None. Fahar Merchant: Employed by Medicenna. Nina Merchant: Employed by Medicenna. Dina Randazzo: None. Michael Vogelbaum: Honoraria from Tocagen and Celgene. Indirect equity and royalty rights from Infuseon Therapeutics. Frank Vrionis: None. Eva Wembacher-Schroeder: None. Miroslaw Zabek: None. Nicholas Butowski: Paid consultant for Medicenna. Advisor for Hoffman La-Roche; Nativis; Bristol Meyers Squibb; VBL, Pulse Therapeutics, Lynx Group, Boston Bio. Paid Consultant for Nativis; Hoffman La-Roche; DelMar, QED, Karyopharm. Grant funding received from: Beigene, BMX, Deciphera, DeNovo, Epicentrix, Oncoceutics, Stellar Orbus, Istari, Kiyatec, Amgen, Tocagen.

References

- 1. van Linde ME, Brahm CG, de Witt Hamer PC, et al. Treatment outcome of patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: a retrospective multicenter analysis. J Neurooncol. 2017;135(1):183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weller M, Le Rhun E, Preusser M, et al. How we treat glioblastoma. [abstract] ESMO Open. 2019;4(Suppl 2):e000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mooney J, Bernstock JD, Ilyas A, et al. Current approaches and challenges in the molecular therapeutic targeting of glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2019;129:90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weller M, Cloughesy T, Perry JR, Wick W. Standards of care for treatment of recurrent glioblastoma--are we there yet? Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(1):4–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mineo JF, Bordron A, Baroncini M, et al. Prognosis factors of survival time in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: a multivariate analysis of 340 patients. Acta Neurochir. 2007;149(3):245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brada M, Hoang-Xuan K, Rampling R, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme at first relapse. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(2):259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4733–4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(5):740–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stupp R, Wong ET, Kanner AA, et al. NovoTTF-100A versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: a randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(14):2192–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, et al. Lomustine and Bevacizumab in Progressive Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1954–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. GLIADEL® WAFER (carmustine implant), for Intracranial Use US Prescribing Information Eisai Inc; 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/020637s029lbl.pdf. Accessed Nov 3, 2019.

- 13. Cohen MH, Shen YL, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA drug approval summary: bevacizumab (Avastin) as treatment of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Oncologist. 2009;14(11):1131–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Avastin® (bevacizumab) US Prescribing Information; Genentech, Inc; 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/125085s317lbl.pdf. Accessed Nov 3, 2019.

- 15. Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):709–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reardon DA, Brandes AA, Omuro A, et al. Effect of nivolumab vs bevacizumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: the CheckMate 143 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1003–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. D’Alessandro G, Monaco L, Catacuzzeno L, et al. Radiation increases functional KCa3.1 expression and invasiveness in glioblastoma. Cancers. 2019;11(3):279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Han J, Puri RK. Analysis of the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) database identifies an inverse relationship between interleukin-13 receptor α1 and α2 gene expression and poor prognosis and drug resistance in subjects with glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2018;136(3):463–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Randazzo D, Achrol A, Aghi M, et al. MDNA55, a locally administered IL4-guided toxin as a targeted treatment for recurrent glioblastoma. [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_Suppl) :2039. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joshi BH, Leland P, Asher A, et al. In situ expression of interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptors in human brain tumors and cytotoxicity of a recombinant IL-4 cytotoxin in primary glioblastoma cell cultures. Cancer Res. 2001;61(22):8058–8061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kohanbash G, McKaveney K, Sakaki M, et al. GM-CSF promotes the immunosuppressive activity of glioma-infiltrating myeloid cells through interleukin-4 receptor-α. Cancer Res. 2013;73(21):6413–6423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kamran N, Kadiyala P, Saxena M, et al. Immunosuppressive myeloid cells’ blockade in the glioma microenvironment enhances the efficacy of immune-stimulatory gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2017;25(1):232–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kreitman RJ, Puri RK, Pastan I. A circularly permuted recombinant interleukin 4 toxin with increased activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(15):6889–6893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chiron MF, Fryling CM, FitzGerald D. Furin-mediated cleavage of Pseudomonas exotoxin-derived chimeric toxins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(50):31707–31711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shapira A, Benhar I. Toxin-based therapeutic approaches. Toxins. 2010;2(11):2519–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wedekind JE, Trame CB, Dorywalska M, et al. Refined crystallographic structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A and its implications for the molecular mechanism of toxicity. J Mol Biol. 2001;314(4):823–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kawakami K, Kawakami M, Leland P, et al. Internalization property of interleukin-4 receptor alpha chain increases cytotoxic effect of interleukin-4 receptor-targeted cytotoxin in cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(1):258–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Puri S, Joshi BH, Sarkar C, et al. Expression and structure of interleukin 4 receptors in primary meningeal tumors. Cancer. 2005;103(10):2132–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weber F, Asher A, Bucholz R, et al. Safety, tolerability, and tumor response of IL4-Pseudomonas exotoxin (NBI-3001) in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. J Neurooncol. 2003;64(1-2):125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Floeth FW, Wittsack HJ, Engelbrecht V, Weber F. Comparative follow-up of enhancement phenomena with MRI and Proton MR Spectroscopic Imaging after intralesional immunotherapy in glioblastoma--Report of two exceptional cases. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2002;63(01):23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rainov NG, Heidecke V. Long term survival in a patient with recurrent malignant glioma treated with intratumoral infusion of an IL4-targeted toxin (NBI-3001). J Neurooncol. 2004;66(1/2):197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ellingson BM, Wen PY, Cloughesy TF. Modified criteria for radiographic response assessment in glioblastoma clinical trials. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(2):307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Davi R, Majumdar A, Bexon M, et al. CLRM-09. Incorporating external control arm in MDNA55 recurrent glioblastoma registration trial. Neurooncol Adv. 2021;3(Suppl 4):iv3. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Majumdar A, Davi R, Bexon M, et al. Building an external control arm for development of a new molecular entity: an application in a recurrent glioblastoma trial for MDNA55. Stat Biosci. 202214(2):285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rahman R, Ventz S, McDunn J, et al. Leveraging external data in the design and analysis of clinical trials in neuro-oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(10):e456–e465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wick W, Weller M, van den Bent M, et al. MGMT testing--the challenges for biomarker-based glioma treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(7):372–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gordon LB, Knopf PM, Cserr HF. Ovalbumin is more immunogenic when introduced into brain or cerebrospinal fluid than into extracerebral sites. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;40(1):81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ellingson BM, Sampson J, Achrol AS, et al. Modified RANO, immunotherapy RANO, and standard RANO response to convection-enhanced delivery of IL4R-targeted immunotoxin MDNA55 in recurrent glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(14):3916–3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ellingson BM, Chung C, Pope WB, Boxerman JL, Kaufmann TJ. Pseudoprogression, radionecrosis, inflammation or true tumor progression? challenges associated with glioblastoma response assessment in an evolving therapeutic landscape. J Neurooncol. 2017;134(3):495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shimamura T, Royal RE, Kioi M, et al. Interleukin-4 cytotoxin therapy synergizes with gemcitabine in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67(20):9903–9912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hassan R, Alewine C, Pastan I. New life for immunotoxin cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(5):1055–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yin D, Valles FE, Fiandaca MS, et al. Optimal region of the putamen for image-guided convection-enhanced delivery of therapeutics in human and non-human primates. Neuroimage. 2011;54(Suppl 1):S196–S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fiandaca MS, Forsayeth JR, Dickinson PJ, Bankiewicz KS. Image-guided convection-enhanced delivery platform in the treatment of neurological diseases. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(1):123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Healy AT, Vogelbaum MA. Convection-enhanced drug delivery for gliomas. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6(Suppl 1):S59–S67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jahangiri A, Chin AT, Flanigan PM, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery in glioblastoma: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. J Neurosurg. 2017;126(1):191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mehta AM, Sonabend AM, Bruce JN. Convection-enhanced delivery. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(2):358–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Butowski N. Convection-enhanced delivery (CED) of MDNA55 in adults with recurrent glioblastoma. Presentation at the Society for CNS Interstitial Delivery of Therapeutics. Society for CNS Interstitial Delivery of Therapeutics (SCIDOT). 2019 November Conference; Pheonix, Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proceeding of the 24th Annual Scientific Meeting and Education Day of the Society for Neuro-Oncology (November 22–24, 2019, Phoenix, Arizona), Published in Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(Suppl_6):vi8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.