Abstract

Objective

We evaluated how contemporary data on infrapopliteal vessel preparation have been reported to identify knowledge gaps and opportunities for future research.

Methods

A literature search was performed on Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar to identify clinical research studies reporting on the outcomes of vessel preparation in below-the-knee lesions between 2006 and 2021. Studies were excluded if they were case reports or case series with a sample size of <10.

Results

A total of 15 studies comprising 5450 patients were included in this review, with vessel preparation performed in 2179 cases (40%). Of the 15 studies, 2 were randomized controlled trials, 6 were prospective cohort studies, and 7 were retrospective studies. Only 2 of the 15 studies evaluated intravascular lithotripsy devices, and 6 were noncomparative studies. The mean diameter stenosis treated was 86.7% ± 12.6%, and the lesion length was 71.7 ± 55.3 mm. Large heterogeneity was found in the choice and definitions of end points and lesion characterization. Procedural success ranged between 84% and 90%, and bailout stenting was performed in 0.8% to 15% of cases. Of the five studies comparing procedural success of atherectomy with or without balloon angioplasty to balloon angioplasty alone, only one was in favor of the former (99% vs 90%; P < .001). The remaining studies did not show any statistically significant differences. Similarly, atherectomy had a significantly superior limb salvage rate in only one of seven studies (91% vs 73%; P = .036). In contrast, the seven studies evaluating target lesion revascularization reported conflicting outcomes, with two in favor of atherectomy, two against atherectomy, and three reporting similar outcomes between atherectomy and balloon angioplasty alone. None of the studies evaluating intravascular lithotripsy was comparative.

Conclusions

The current body of evidence on vessel preparation in tibial arteries is largely based on observational studies with a large amount of heterogeneity and a number of inconsistencies. Further clinical and experimental studies with more robust study designs are warranted to investigate the comparative efficacy and safety of vessel preparation in calcified tibial arteries.

Keywords: Atherectomy, Below-the-knee lesions, Infrapopliteal artery disease, Intravascular lithotripsy, Vessel calcification, Vessel preparation, Tibial arteries

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is increasing in prevalence and is a morbid condition with high mortality affecting >200 million people worldwide,1 of whom 8.5 million are estimated to be in the United States alone.2 The most advanced form of this disease—critical limb threatening ischemia (CLTI)—has an estimated prevalence of 0.5% to 2.3% in the general population in Western countries.1 CLTI is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, partly due to its frequent association with coronary and cerebrovascular disease3 but also due to the anatomic complexity and severity of the underlying arterial lesions. CLTI patients are known to present with longer lesions and significant multilevel and distal disease patterns compared with those with claudication.4 The current “percutaneous-first” approach in the revascularization of patients with PAD has led to an exponential increase in the number of endovascular procedures performed to treat these arterial lesions, resulting in major progress in device technology over the decades. Despite this progress, the rate of limb loss resulting from failed percutaneous interventions (PVIs) in CLTI patients has remained high. The BASIL (bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg) trial showed that 20% of all PVIs had immediate technical failures and required subsequent procedures,5 and these failures have been acknowledged to be associated with poor outcomes in terms of major limb amputations even after patients have been offered secondary bypass interventions.6 Although procedural success rates have increased substantially since the report of the BASIL trial in 2005, clinical success rates, including limb salvage and freedom from amputation, have not significantly improved,7 and an estimated 22% of CLTI patients will require a major amputation or die within just 1 year.4 These outcomes have been further corroborated by the recent BEST-CLI (surgery vs endovascular therapy for chronic limb-threatening ischemia) trial, which reported a major amputation rate of 15% for patients receiving endovascular therapy.8

Calcium is considered to play a major role in PVI failure, given that calcified lesions are usually difficult to cross with a wire and generally require very high balloon inflation pressures, which can lead to intimal disruption and vessel wall damage.9 This is particularly challenging in infrapopliteal vessels where calcifications are common, especially in patients with diabetes and end-stage renal disease. It is estimated that 70% of tibial vessels will require reinterventions to maintain or restore patency within 12 months of balloon angioplasty,7 and these outcomes are no better, even with stenting.10 The quest for a solution to reduce vessel calcification and improve the outcomes of lower extremity PVIs has resulted in the development of various atherectomy and, more recently, intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) devices. The concept of “vessel preparation” with these devices is to modify and debulk hard calcified plaques and, thus, make the vessel wall more compliant and amenable to balloon inflation. Despite the controversies surrounding the safety and efficacy of atherectomy devices, an exponential growth has occurred in their use in recent years, with some investigators reporting promising procedural outcomes. However, evidence is lacking to support the use of these calcium-modifying devices vs plain balloon angioplasty alone to improve long-term outcomes,11, 12, 13 and some investigators have even suggested that atherectomy is associated with worse outcomes compared with plain balloon angioplasty.14 These controversies justify the need to critically investigate such techniques and devices. Thus far, studies evaluating atherectomy and IVL in the lower extremity have mostly focused on femoropopliteal lesions. As such, little is known about their role for below-the-knee (BTK) lesions. Because of the poor performance of stents in the tibial vessels, BTK lesions might be the most in need of these techniques, if proved efficacious. Thus, our review aims to survey the literature to evaluate how contemporary data on infrapopliteal atherectomy and IVL have been reported and identify knowledge gaps and opportunities for future research.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews) guidelines.15 Institutional review board approval was not required. Two key research questions were developed for this review:

-

1.

Are the methods used in contemporary studies of atherectomy and IVL in tibial lesions adequate for making recommendations for clinical practice?

-

2.

What are the gray areas in the literature on the topic of atherectomy and IVL for infrapopliteal arterial disease that require further investigation?

Literature search strategy

An extensive literature search was performed on PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases for relevant reports on atherectomy and IVL using the search queries below:

-

•PubMed

-

◦Atherectomy: ("atherectomy"[All Fields]) AND (("infrapopliteal lesions"[All Fields]) OR ((below-the-knee lesions) OR ((“BTK” lesions) NOT (Bruton))))

-

◦IVL: ((shockwave) OR ("intravascular lithotripsy"[All Fields])) AND ((("btk lesions"[All Fields]) OR ("below the knee lesions"[All Fields])) OR ("infrapopliteal"[All Fields]))

-

◦

-

•Web of Science

-

◦Atherectomy: TI = (atherectomy AND infrapopliteal) or TI = (atherectomy AND tibial) OR TI = (atherectomy AND below-the-knee)

-

◦IVL: TI = (intravascular lithotripsy AND infrapopliteal) or TI = (intravascular lithotripsy AND tibial) OR TI = (intravascular lithotripsy AND below-the-knee)

-

◦

-

•Google Scholar

-

◦Atherectomy: allintitle: "atherectomy" infrapopliteal OR tibial OR "below the knee"

-

◦IVL: allintitle: "Intravascular lithotripsy" infrapopliteal OR tibial OR "below the knee"

-

◦

After duplicate reports were removed, the articles were screened by title to eliminate irrelevant studies. Next, the abstracts of the remaining articles were screened with application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria to further select eligible reports for full-text review. The last date of the search was December 31, 2021.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they were original research conducted on human subjects, with accessible full text and specifically focused on infrapopliteal lesions. For the purpose of the present review, “infrapopliteal” was defined as the distal popliteal artery (P3) segment and below. Studies that reported on treatment of both femoropopliteal and BTK lesions were included only if their design permitted a subgroup analysis of the latter. Studies were excluded if they were case reports or case series with a sample size <10 or had not provided enough information to evaluate at least the periprocedural outcomes or the full-text report was not available in either English or French. To reflect modern clinical practice, the included studies were limited to those reported during the previous 15 years (ie, 2006-2021).

Data extraction and analysis

The data extracted include author details and publication date, study design, sample size, preprocedural imaging modalities, and the methods of lesion characterization and calcium scoring. In addition, the choice and definition of end points, procedural characteristics, and acute and longitudinal outcomes were analyzed. These were tabulated using an Excel (Microsoft Corp) spreadsheet for analysis. For each variable, the number of studies reporting valid data was specified, with continuous variables presented as the mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as percentages. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software, release 17 (StataCorp).

Results

Characteristics of selected studies

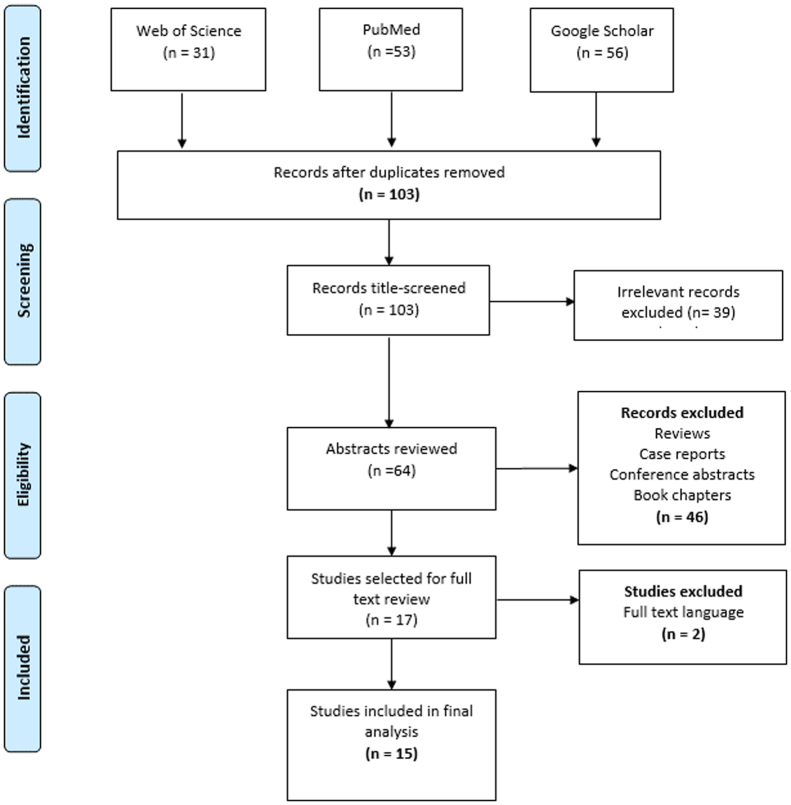

The literature search identified 140 reports, of which 15 fulfilled all eligibility criteria for inclusion in the present analysis16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 (Fig 1). The total number of patients enrolled in all 15 studies was 5450, and the number of patients treated with atherectomy and IVL devices was 2179 (40%). Only two studies evaluated IVL devices, both of which were noncomparative prospective studies.25,29 Of the 13 studies evaluating atherectomy devices, 3 were noncomparative,16,17,22 6 compared atherectomy and plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) without vessel preparation,18,19,21,24,26,27 one compared atherectomy to both POBA and stenting,20 2 compared atherectomy plus drug-coated balloon angioplasty to drug-coated balloon angioplasty only, and 1 compared atherectomy in infrapopliteal lesions vs femoropopliteal lesions23 (Table I). Of the 13 atherectomy studies, 2 were randomized controlled trials,19,28 4 were prospective cohort studies,16,17,22,23 and 7 were retrospective studies.18,20,21,24,26,27,30 Directional atherectomy devices were used in 6 of the 13 studies, orbital atherectomy in 5, and laser atherectomy in 3, with 1 study not specifying the type of atherectomy device used.24 The different devices evaluated in each of the studies are presented in Table II.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram showing selection of studies of vessel preparation in infrapopliteal arteries.

Table I.

Characteristics of selected studies

| Investigator | Study design | Eligibility criteria | Sample size (limbs) | Comparative | Compared groups | ATH/IVL, No. | Claudication, % | FP segment, % | Standalone ATH/IVL, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeller et al,16 2007 | Prospective | RC 2-5; ≥70% stenosis; no concentric calcification | 36 | No | NA | 36 | 47 | 0 | 62 |

| Safian et al,17 2009 | Prospective | RC 1-5; ≥50% stenosis; lesion length ≤100 | 124 | No | NA | 124 | 64 | 72 | 58 |

| Tan et al,18 2011 | Retrospective | Infrapopliteal intervention | 35 | Yes | ATH vs POBA | 20 | 23 | 0 | 83 |

| Shammas et al,19 2012 | RCT | RC 4-6; RVD ≥1.5 mm; stenosis ≥50%; no subintimal crossing | 50 | Yes | ATH vs POBA | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reynolds et al,20 2013 | Retrospective | Age ≥65 years, tibial intervention | 2080 | Yes | ATH vs POBA vs stenting | 573 | NS | NS | 0 |

| Todd et al,21 2013 | Retrospective | Tibial intervention | 418 | Yes | ATH vs POBA | 79 | 0 | 57 | 14 |

| Rastan et al,22 2015 | Prospective | RC 1-6; ≥50% stenosis; no severe calcification | 145 | No | NA | 145 | 52 | 0 | NS |

| Lee et al,23 2016 | Prospective | RC 4-6 | 1109 | Yes | BTK vs ATK | 523 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Khalili et al,24 2018 | Retrospective | No concomitant FP disease | 430 | Yes | ATH vs POBA | 223 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Brodmann et al,25 2018 | Prospective | >50% Stenosis; lesion length <150 mm; RC 1-5; successful passage of guidewire | 20 | No | NA | 20 | 20 | 0 | 86 |

| Zia et al,26 2019 | Retrospective | RC 4-6 | 342 | Yes | ATH vs POBA | 159 | 0 | 42 | 0 |

| Kokkinidis et al,27 2021 | Retrospective | RC 4-6 | 313 | Yes | ATH vs POBA | 76 | 0 | 80 | NS |

| Rastan et al,28 2021 | RCT | Age ≥50 years; RC 3-5; >70% stenosis; lesion length 60-250 mm; no acute thrombosis | 80 | Yes | ATH + DCB vs DCB | 40 | 29 | 0 | 0 |

| Adams et al,29 2021 | Prospective | RC 2-6; moderate to severe calcification | 101 | No | NA | 101 | 31 | NS | 77 |

| Yang et al,30 2021 | Retrospective | RC 4-6; diabetic foot | 79 | Yes | ATH + DCB vs DCB | 35 | 0 | NS | 0 |

ATH, Atherectomy; ATK, above-the-knee; BTK, above-the-knee; DCB, drug-coated balloon; FP, femoropopliteal; IVL, intravascular lithotripsy; NA, not applicable; NS, not specified; POBA, plain old balloon angioplasty; RC, Rutherford classification; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RVD, reference vessel diameter.

Table II.

Type of vessel preparation and devices used in infrapopliteal lesions in selected studies

| Investigator | Directional atherectomy | Orbital atherectomy | Laser atherectomy | IVL | Devicea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeller et al16 | Yes | – | – | – | SilverHawk |

| Safian et al17 | Yes | – | – | Diamondback 360 | |

| Tan et al18 | Yes | – | – | – | SilverHawk |

| Shammas et al19 | – | Yes | – | – | Diamondback 360 |

| Reynolds et al20 | NS | NS | NS | – | NS |

| Todd et al21 | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Excimer; Diamondback 360; SilverHawk |

| Rastan et al22 | Yes | – | – | – | SilverHawk |

| Lee et al23 | – | Yes | – | – | Diamondback 360; Predator 360°; Stealth 360 |

| Khalili et al24 | NS | NS | NS | – | NS |

| Brodmann et al25 | – | – | – | Yes | Shockwave |

| Zia et al26 | Yes | – | – | – | Diamondback 360; SilverHawk; TurboHawk; HawkOne |

| Kokkinidis et al27 | – | – | Yes | – | NS |

| Rastan et al28 | Yes | – | – | – | SilverHawk; TurboHawk; Lutonix |

| Adams et al29 | – | – | – | Yes | Shockwave |

| Yang et al30 | – | – | Yes | – | Excimer |

IVL, Intravascular lithotripsy; NS, not specified.

SilverHawk, TurboHawk, and HawkOne: Medtronic; Diamondback 360 and Predator 360°: Cardiovascular Systems Inc; Stealth 360: OrbusNeich; Lutonix: Lutonix Inc.

Patient population and characteristics

The study population included solely patients with CLTI in seven studies, with 4391 patients, of whom 1470 (33%) had received vessel preparation. The proportion of CLTI patients in the remaining studies varied between 23% and 82%, with an average of 62%, and two studies reported a CLTI subpopulation of <50%.17,22 In addition, five studies excluded Rutherford category 6 patients.16,17,24,25,28 Other relevant exclusion criteria included the presence of concentric calcification in the study by Zeller et al,16 the presence of severe calcification in a study by Rastan et al,22 <70% diameter stenosis, lesion length <60 mm, and the presence of acute thrombosis in one study.28 Shammas et al19 specified the exclusion of patients with a subintimal lesion crossing, and eight studies excluded patients with concomitant femoropopliteal disease.16,18,19,22, 23, 24, 25,28 In contrast, four studies had included the latter.17,18,26,28 Rastan et al28 enrolled only patients aged ≥50 years in their study, and Reynolds et al20 included only patients aged ≥65 years. Finally, Yang et al30 included only patients with a diabetic foot in their cohort study. The pooled mean preoperative ankle brachial index for the included patients, recorded in 4 of the 15 studies, was 0.53 ± 0.08, with no significant differences between the atherectomy and POBA groups across the studies.

Anatomic characteristics and operative details

Of the preprocedural imaging modalities, digital subtraction angiography was reported in 9 of 15 studies, of which 2 reported duplex ultrasound in addition to digital subtraction angiography.27,28 Brodmann et al25 required computed tomography angiography or plain radiography to confirm the evidence of calcification. Zia et al26 used other noninvasive imaging modalities in their study but did not give further specifications regarding the type of imaging, and 4 of 15 studies did not specify the imaging modalities used.18,20,21,24 None of the studies reported the use of magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative lesion characterization, and only two studies specified the use of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) for intraoperative lesion characterization.17,28 Independent angiographic core laboratory assessment of the lesions and angiographic outcomes was used in 5 of the 15 studies.22,24,25,28,29 Both of the two studies evaluating IVL used core laboratory adjudication.25,29 Of the 15 studies, 5 had not specified the degree of calcification, 3 had specified the degree of calcification in their cohort but had not defined the scoring system used,14,24,27 and 3 had used a core laboratory-specific scoring system.24,25,28 In contrast, Lee et al23 graded calcifications as follows: minimal, <25%; mild, 25% to 50%; moderate, 50% to 75%; and severe, >75% of the circumference. Adams et al29 and Rastan et al22 used the PARC (Peripheral Arterial Research Consortium) and DEFINITIVE (Determination of EFfectiveness of the SilverHawk PerIpheral Plaque ExcisioN System (SIlverHawk Device) for the Treatment of Infrainguinal VEssels/Lower Extremities) Ca++ calcium scoring system, respectively.31 In addition, Lee et al23 identified 9 of 692 patients with infrapopliteal fibrotic plaques (1.3%) and 1 of 692 patients with soft plaques (0.1%) in their study. The proportion of patients with moderate to severe calcification ranged between 9% and 79% (median, 40%) across the studies. Also, the proportion of chronic total occlusion was reported in 10 of the 15 studies and ranged between 12% and 77% (median, 42%), with no study showing a significant difference between the atherectomy and POBA groups. The pooled mean diameter stenosis—recorded in 8 of 15 studies—was 86.7% ± 12.6%, with a pooled mean lesion length of 71.7 ± 55.3 mm (reported in 12 of 15 studies). The reference vessel diameter was specified in 6 of the 15 studies, with a pooled mean of 2.9 ± 0.2 mm. A total of 3 of the 15 studies used the TASC II (Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus Document on Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease) classification to define the anatomic complexity of the lesions, with TASC C and D lesions present in 5.9%, 23%, and 82% of the vessel preparation subgroups, respectively. Kokkinidis et al27 reported a significantly higher proportion of TASC C and D lesions in the laser atherectomy group than in the POBA group (82% vs 45%; P < .0001). Treatment of concomitant femoropopliteal disease was performed in 57% to 80% of the patients in four studies.17,21,26,27 Atherectomy was performed as a stand-alone procedure without adjunctive balloon angioplasty in 14% to 83% of the patient population in 4 of 13 studies.16, 17, 18,21 Of the remaining nine studies, three did not specify whether all procedures were performed with adjunctive balloon angioplasty.22,23,27

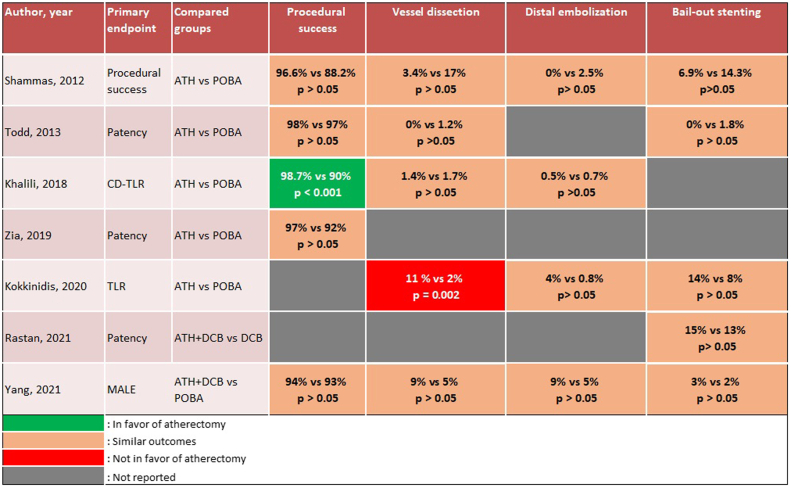

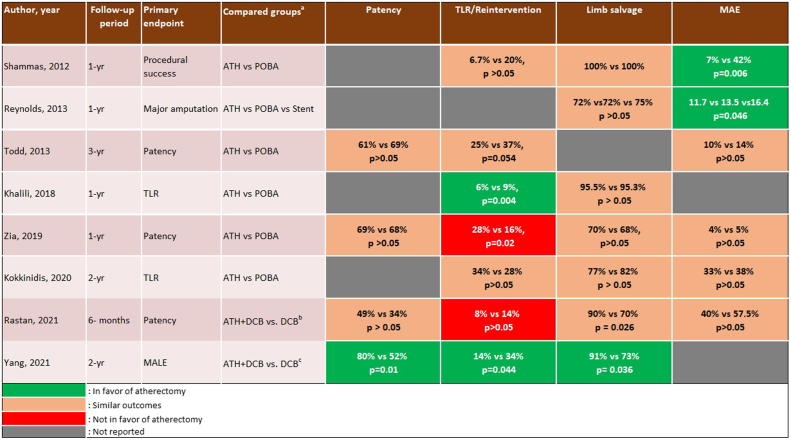

Report of outcomes

The primary end point was primary patency in 5 of 15 studies,16,21,22,26,28 major amputation in 2 studies,20,30 target lesion revascularization in 2 studies,24,27 and acute procedural success in 4 studies.17,19,23,28 However, 2 of the 15 studies did not specify the primary end point.18,29 Three studies reported only acute and/or 30-day outcomes,23,25,29 including the two IVL studies.25,29 The follow-up period for the remaining 12 studies ranged between 6 months and 3 years, with a mean follow-up of 16 ± 8 months (Table III). Procedural success was reported in 11 of 15 studies and was defined as ≤30% residual stenosis without major complications in 9 of 11 studies. Brodmann et al25 used a threshold of ≤50% residual stenosis, and Adams et al29 did not specify the definition used. The acute and longitudinal outcomes of vessel preparation in infrapopliteal arteries are reported in Table III. Procedural success ranged between 84% and 99% in 12 of the 15 studies, and the reported rate of vessel dissection and distal embolization ranged between 0% and 10.5% and 0% and 15%, respectively. In addition, bailout stenting was used in 0.8% to 15% of cases across 13 of 15 studies. Five studies reported 1-year primary patency of 45% to 84%, with a mean of 65.2%. Yang et al30 reported 2-year primary patency of 85% with laser atherectomy. The comparative outcomes of atherectomy with or without balloon angioplasty vs balloon angioplasty alone are illustrated in Figs 2 and 3. Of the five studies comparing procedural success between groups, only one was in favor of atherectomy with or without balloon angioplasty (99% vs 90%; P < .001), and one of the five studies found a significantly higher rate of target vessel dissection in the atherectomy group (11% vs 2%; P = .002).27 The remaining studies did not show any statistically significant differences in terms of procedural success or acute complications (Fig 2). Similarly, atherectomy had a significantly superior limb salvage rate in only one of the seven studies (91% vs 73%; P = .036).30 In contrast, the seven studies evaluating target lesion revascularization reported conflicting outcomes, with two in favor of atherectomy,24,30 two against atherectomy,26,28 and three reporting similar outcomes between atherectomy and balloon angioplasty alone19,21,27 (Fig 3). None of the studies evaluating IVL were comparative.

Table III.

Reported outcomes of infrapopliteal vessel preparation using atherectomy or intravascular lithotripsy between 2007 and 2021

| Investigator | Follow-up, months | Acute outcomes, % |

Longitudinal outcomes,a % |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural success | Vessel dissection | Distal embolization | Bailout stenting | Primary patency | Freedom from major amputation | Reintervention | ||

| Zeller et al,16 2007 | 24 | 97.0 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 67.0 | – | 24.0 |

| Safian et al,17 2009 | 6 | 90.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 4.0 | – | 100.0b | 5.6b |

| Tan et al,18 2011 | 6 | 93.1 | 0.0 | 15.0 | 6.9 | 60.0b | 88.0b | – |

| Shammas et al,19 2012 | 12 | 96.6 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 6.9 | – | 100.0 | 6.7 |

| Reynolds et al,20 2013 | 12 | – | – | – | – | – | 72.0 | – |

| Todd et al,21 2013 | 36 | 97.5 | 0.0 | – | 0.0 | 61.0 | – | 25.0 |

| Rastan et al,22 2015 | 12 | 69.6 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 84.0 | 97.8 | 8.8 |

| Lee et al,23 2016 | NA | 84.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.6 | – | – | – |

| Khalili et al,24 2018 | 12 | 98.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 2.2 | – | 95.5 | 6.0 |

| Brodmann et al,25 2018 | 1 | 95.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 | – | NA | – |

| Zia et al,26 2019 | 12 | 96.9 | – | – | – | 69.0 | 70.0 | 28.0 |

| Kokkinidis et al,27 2021 | 24 | – | 10.5 | 4.0 | 14.5 | – | 77.0 | 34.0 |

| Rastan et al,28 2021 | 12 | – | – | – | 15.0 | 45.0 | 97.0 | 30.0 |

| Adams et al,29 2021 | NA | 84.2 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 10.9 | – | – | – |

| Yang et al,30 2021 | 24 | 94.3 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 2.9 | 85.0c | 91.4c | 14.3c |

NA, Not applicable.

One-year outcomes reported, unless otherwise specified.

Only 6-month outcomes reported.

Only 2-year outcomes reported.

Fig 2.

Reported acute outcomes of atherectomy (ATH) with or without balloon angioplasty vs balloon angioplasty alone in infrapopliteal lesions. CD-TLR, Clinically driven target lesion revascularization; DCB, drug-coated balloon; MAE, major adverse event; MALE, major adverse limb events; POBA, plain old balloon angioplasty; TLR, target lesion revascularization.

Fig 3.

Longitudinal outcomes of atherectomy (ATH) with or without balloon angioplasty vs balloon angioplasty alone in infrapopliteal lesions reported in the literature. DCB, Drug-coated balloon; MAE, major adverse event; MALE, major adverse limb events; POBA, plain old balloon angioplasty; TLR, target lesion revascularization. aOne-year outcomes reported unless otherwise specified; bonly 6-month outcomes reported; conly 2-year outcomes reported.

Discussion

In the present review, we surveyed contemporary literature on vessel preparation in tibial arteries and found 15 studies directly addressing the topic, of which only 2 were randomized controlled trials, with the remaining studies largely retrospective, although comparative for most. Although most of the 15 studies reported favorable technical outcomes, they failed to show the superiority of vessel preparation compared with balloon angioplasty alone in terms of vessel dissection, primary patency, target lesion revascularization, and freedom from major amputation. This finding is consistent with that of a previous meta-analysis of four studies, which did not find a statistically significant difference between atherectomy and balloon angioplasty alone in infrapopliteal lesions.32 Furthermore, Pitoulias and Pitoulias33 were unable to prove the superiority of atherectomy over angioplasty in their recent systematic review of six studies. Similarly, Nugteren et al34 reported no significant benefit from the routine use of calcium-modifying devices vs balloon angioplasty alone in their meta-analysis of 11 studies and 1685 patients. All these studies, however, mainly reviewed atherectomy devices with no mention of the relatively more recent IVL. Our scoping review further expands the list of studies evaluating atherectomy and includes two studies that assessed IVL for BTK lesions. The role of these calcium-modifying devices continues to be a controversial issue among vascular specialists, despite the continuous increase in their use. The inability to reconcile the theoretical benefits of calcium debulking with the actual observed clinical outcomes in infrapopliteal arterial disease might partly stem from the inherent limitations of these largely observational and retrospective study designs conducted thus far, as was suggested by Katsanos et al.35 However, we also believe that perioperative lesion characterization and patient selection play an important role in achieving optimal results with these devices. Given that each vessel preparation device has been designed to treat specific types of lesions and has their own advantages and disadvantages, using them for the wrong type of lesions might not yield optimal results.35 In the present review, we found large heterogeneity in the report of lesion characteristics, and the degree and distribution of calcification were not clearly defined in many studies. Although some studies excluded concentric calcification and very complex lesions, others treated chronic total occlusion in as high as 77% of the population. In addition, some investigators reported the use of different types of atherectomy devices without giving much information about the selection criteria for each device. Furthermore, it is not clear what proportion of chronic total occlusions were crossed subintimally, and uniformity was lacking in the choice and definition of end points. This broad heterogeneity and the possibility that some of the devices had been used under suboptimal conditions might partly explain the inconsistencies in the outcomes across studies. Regarding perioperative planning, the role of imaging is crucial in selecting the right type of lesions for the right type of procedure. However, in the present review, we found a lack of uniformity in the imaging modalities and interpretation across the studies, and only 5 of 15 studies used an independent angiographic core laboratory assessment of the lesions and technical outcomes. Radiographic angiography is currently the “gold standard” imaging modality for infrapopliteal lesions, and most available calcium scores have been derived from angiographic criteria; however, it is technically a “lumenography-only” technique and does not allow for accurate assessment of lesion composition or calcium severity and distribution.36 Although scarcely reported in the studies reviewed, IVUS, however, offers virtual histologic findings and can accurately identify concentric calcification and is now routinely used by many interventionalists.36 Nonetheless, this very important intraoperative imaging technique is limited by its “side-looking” nature and the relative difficulty of navigating the IVUS catheter through high-grade lesions. Furthermore, IVUS does not allow for planning procedures in advance, and, often, the choice of device and treatment strategy at the procedure is limited to that available in stock, regardless of intraoperative lesion characterization. In our experience, IVUS use in infrapopliteal vessels can also be limited by the added intraprocedural time required. Magnetic resonance imaging using ultrashort echo time sequences can potentially address these shortcomings by providing a safer and more accurate modality for lesion characterization and merits further exploration in future investigations.37,38

Perspectives for future research

A need clearly exists for further high-quality investigations to guide practice. This need is urgent given the current trend toward overuse and possibly inappropriate use of these devices, which could be harming patients with increased adverse events14 and harming the healthcare system as a whole owing to its substantial economic impact.39 In addition, ex vivo experimental studies in human models will be instrumental in elucidating the mechanistic performance of vessel preparation devices in tibial arteries and their effects on the vessel wall. Although such studies have been previously performed in animal models, experiments targeting calcified human tibial arteries in this regard are heavily lacking in the literature.40 In line with the Society for Vascular Society reporting standards, future studies should include more specific details on lesion characteristics, such lesion length, eccentricity of calcifications, calcium scoring, device-specific data, and the use of embolic protection, and should specify whether atherectomy and IVL were performed as standalone or adjunct procedures.41 We also recommend that studies focus as much as possible on isolated infrapopliteal lesions and otherwise specify whether multilevel disease was concurrently treated. This will ensure fair comparisons and a better assessment of outcomes. One other area that should be the focus of future clinical studies is head-to-head comparisons of the different vessel preparation devices in tibial arteries. To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet investigated this. The results of such studies will be potentially useful in determining the right device for the right lesion. Finally, the mid-term outcomes of IVL in infrapopliteal arterial disease are unknown and warrant further investigation.

Study limitations

One major limitation with this study is the search strategy used, which could have led to some studies being missed. However, given that the search was performed using three major search engines with subject-specific keywords, we believe the number of missed studies—if any—to not significantly affect the results presented. Second, although efforts were made to limit inclusion to CLTI, some of the studies also reported infrapopliteal interventions for patients with claudication, which is not in line with the Society for Vascular Surgery's appropriate use criteria.42 This, therefore, questions the relevance of such studies to modern practice and warrants caution when interpreting the results from our review. Finally, because our study was a scoping review and not intended to be a meta-analysis, as such, robust conclusions on the effectiveness of atherectomy and IVL in treating BTK lesions cannot be derived from the data presented alone.

Conclusions

The current body of evidence on vessel preparation in tibial arteries is largely based on observational studies with a large amount of heterogeneity and inconsistencies regarding patient selection, treatment indications, lesion characterization, choice of end points, and the report of outcomes. Further comparative clinical trials with more robust designs are urgently warranted to elucidate the role of vessel preparation in complex infrapopliteal lesions and to guide recommendations on treatment strategies for these lesions.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: BB, KS, ABL, TLR

Analysis and interpretation: BB

Data collection: BB, KS

Writing the article: BB, TLR

Critical revision of the article: BB, KS, ABL, TLR

Final approval of the article: BB, KS, ABL, TLR

Statistical analysis: Not applicable

Obtained funding: Not applicable

Overall responsibility: TLR

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: A.B.L. is a consultant for Avail, Boston Scientific, and W.L. Gore & Associates and received an institutional research grant from Siemens Inc. B.B., K.S., and T.L.R. have no conflicts of interest.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the Journal policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fowkes F.G.R., Rudan D., Rudan I., et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virani S.S., Alonso A., Aparicio H.J., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update. Circulation. 2021;143:e254–e743. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampson U.K.A., Fowkes F.G.R., McDermott M.M., et al. Global and regional burden of death and disability from peripheral artery disease: 21 world regions, 1990 to 2010. Glob Heart. 2014;9:145–158.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conte M.S., Bradbury A.W., Kolh P., et al. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019;58:S1–S109.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradbury A.W., Adam D.J., Bell J., et al. Bypass versus Angioplasty in Severe Ischaemia of the Leg (BASIL) trial: analysis of amputation free and overall survival by treatment received. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:18S–31S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan B.W., De Martino R.R., Stone D.H., et al. Prior failed ipsilateral percutaneous endovascular intervention in patients with critical limb ischemia predicts poor outcome after lower extremity bypass. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:730–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.03.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez N., McEnaney R., Marone L.K., et al. Predictors of failure and success of tibial interventions for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farber A., Menard M.T., Conte M.S., et al. Surgery or endovascular therapy for chronic limb-threatening ischemia. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2305–2316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocha-Singh K.J., Zeller T., Jaff M.R. Peripheral arterial calcification: prevalence, mechanism, detection, and clinical implications. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83:E212–E220. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu C.C.T., Kwan G.N., Singh D., Rophael J.A., Anthony C., van Driel M.L. Angioplasty versus stenting for infrapopliteal arterial lesions in chronic limb-threatening ischaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD009195. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009195.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambler G.K., Radwan R., Hayes P.D., Twine C.P. Atherectomy for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD006680. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006680.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z., Huang Q., Pu H., et al. Atherectomy combined with balloon angioplasty versus balloon angioplasty alone for de Novo femoropopliteal arterial diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021;62:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamantopoulos A., Katsanos K. Atherectomy of the femoropopliteal artery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2014;55:655–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramkumar N., Martinez-Camblor P., Columbo J.A., Osborne N.H., Goodney P.P., O’Malley A.J. Adverse events after atherectomy: analyzing long-term outcomes of endovascular lower extremity revascularization techniques. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012081. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeller T., Sixt S., Schwarzwälder U., et al. Two-year results after directional atherectomy of infrapopliteal arteries with the SilverHawk device. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14:232–240. doi: 10.1177/152660280701400216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safian R.D., Niazi K., Runyon J.P., et al. Orbital atherectomy for infrapopliteal disease: device concept and outcome data for the OASIS trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;73:406–412. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan T.W., Semaan E., Nasr W., et al. Endovascular revascularization of symptomatic infrapopliteal arteriosclerotic occlusive disease: comparison of atherectomy and angioplasty. Int J Angiol. 2011;20:19–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shammas N.W., Lam R., Mustapha J., et al. Comparison of orbital atherectomy plus balloon angioplasty vs. balloon angioplasty alone in patients with critical limb ischemia: results of the CALCIUM 360 randomized pilot trial. J Endovasc Ther. 2012;19:480–488. doi: 10.1583/JEVT-12-3815MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds S., Galiñanes E.L., Dombrovskiy V.Y., Vogel T.R. Longitudinal outcomes after tibioperoneal angioplasty alone compared to tibial stenting and atherectomy for critical limb ischemia. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2013;47:507–512. doi: 10.1177/1538574413495467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Todd K.E., Ahanchi S.S., Maurer C.A., Kim J.H., Chipman C.R., Panneton J.M. Atherectomy offers no benefits over balloon angioplasty in tibial interventions for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rastan A., McKinsey J.F., Garcia L.A., et al. One-year outcomes following directional atherectomy of infrapopliteal artery lesions: subgroup results of the prospective, Multicenter DEFINITIVE LE trial. J Endovasc Ther. 2015;22:839–846. doi: 10.1177/1526602815608610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee M.S., Mustapha J., Beasley R., Chopra P., Das T., Adams G.L. Impact of lesion location on procedural and acute angiographic outcomes in patients with critical limb ischemia treated for peripheral artery disease with orbital atherectomy: a CONFIRM registries subanalysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;87:440–445. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khalili H., Jeon-Slaughter H., Armstrong E.J., et al. Atherectomy in below-the-knee endovascular interventions: one-year outcomes from the XLPAD registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:488–493. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brodmann M., Holden A., Zeller T. Safety and feasibility of intravascular lithotripsy for treatment of below-the-knee arterial stenoses. J Endovasc Ther. 2018;25:499–503. doi: 10.1177/1526602818783989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zia S., Juneja A., Shams S., et al. Contemporary outcomes of infrapopliteal atherectomy with angioplasty versus balloon angioplasty alone for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71:2056–2064. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.08.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kokkinidis D.G., Giannopoulos S., Jawaid O., Cantu D., Singh G.D., Armstrong E.J. Laser atherectomy for infrapopliteal lesions in patients with critical limb ischemia. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;23:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rastan A., Brodmann M., Böhme T., et al. Atherectomy and drug-coated balloon angioplasty for the treatment of long infrapopliteal lesions: a randomized controlled trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14 doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.010280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams G., Soukas P.A., Mehrle A., Bertolet B., Armstrong E.J. Intravascular lithotripsy for treatment of calcified infrapopliteal lesions: results from the disrupt PAD III observational study. J Endovasc Ther. 2022;29:76–83. doi: 10.1177/15266028211032953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang S., Li S., Hou L., He J. Excimer laser atherectomy combined with drug-coated balloon versus drug-eluting balloon angioplasty for the treatment of infrapopliteal arterial revascularization in ischemic diabetic foot: 24-month outcomes. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;37:1531–1537. doi: 10.1007/s10103-021-03393-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yin D., Maehara A., Shimshak T.M., et al. Intravascular ultrasound validation of contemporary angiographic scores evaluating the severity of calcification in peripheral arteries. J Endovasc Ther. 2017;24:478–487. doi: 10.1177/1526602817708796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdullah O., Omran J., Enezate T., et al. Percutaneous angioplasty versus atherectomy for treatment of symptomatic infra-popliteal arterial disease. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2018;19:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitoulias A.G., Pitoulias G.A. The role of atherectomy in BTK lesions: A systematic review. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2022;63:20–24. doi: 10.23736/S0021-9509.21.12113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nugteren M.J., Welling R.H.A., Bakker O.J., Ünlü Ç., Hazenberg C.E.V.B. Vessel preparation in infrapopliteal arterial disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endovasc Ther. 2022 doi: 10.1177/15266028221120752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katsanos K., Spiliopoulos S., Reppas L., Karnabatidis D. Debulking atherectomy in the peripheral arteries: is there a role and what is the evidence? Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:964–977. doi: 10.1007/s00270-017-1649-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mintz G.S. Intravascular imaging of coronary calcification and its clinical implications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:461–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roy T.L., Chen H.J., Dueck A.D., Wright G.A. Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of lesions relate to the difficulty of peripheral arterial endovascular procedures. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67:1844–1854.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan E.J., Zhang S., Tirukonda P., Chong L.R. React – a novel flow-independent non-gated non-contrast MR angiography technique using magnetization-prepared 3D non-balanced dual-echo dixon method: preliminary clinical experience. Eur J Radiol Open. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/j.ejro.2020.100238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hicks C.W., Holscher C.M., Wang P., et al. Use of atherectomy during index peripheral vascular interventions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:678–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeno F., Braden G.A., Kaneda H., et al. Mechanism of luminal gain with plaque excision in atherosclerotic coronary and peripheral arteries: assessment by histology and intravascular ultrasound. J Interv Cardiol. 2007;20:107–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2007.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoner M.C., Calligaro K.D., Chaer R.A., et al. Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for endovascular treatment of chronic lower extremity peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64:e1–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.03.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woo K., Siracuse J.J., Klingbeil K., et al. Society for Vascular Surgery appropriate use criteria for management of intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2022;76:3–22.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2022.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]