Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

We examined the frequency and categories of end-of-life care transitions among assisted living community decedents and their associations with state staffing and training regulations.

DESIGN:

Cohort-Study.

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS:

Medicare beneficiaries who resided in assisted livings and had validated death dates in 2018-2019. (N=113,662)

METHODS:

We used Medicare claims and assessment data for a cohort of assisted living decedents. Generalized linear models were employed to examine the associations between state staffing and training requirements and end-of-life care transitions. The frequency of end-of-life care transitions was the outcome of interest. State staffing and training regulations were the key covariates. We controlled for individual, assisted living, and area-level characteristics.

RESULTS:

End-of-life care transitions were observed among 34.89% of our study sample in the last 30 days before death, and among 17.25% in the last 7 days. Higher frequency of care transitions in the last 7 days of life was associated with higher regulatory specificity of licensed (IRR=1.08; P=0.002) and direct care worker staffing (IRR=1.22; P<0.0001). Greater regulatory specificity of direct care worker training (IRR=0.75; P<0.0001) was associated with fewer transitions. Similar associations were found for direct care worker staffing (IRR=1.15; P<0.0001) and training (IRR=0.79; P<0.001) and transitions within 30-days of death.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS:

There were significant variations in the number of care transitions across states. The frequency of end-of-life care transitions among assisted living decedents during the last 7 or 30 days of life was associated with state regulatory specificity for staffing and staff training. State governments and assisted living administrators may wish to set more explicit guidelines for assisted living staffing and training to help improve end-of-life quality of care.

Keywords: Assisted living, end-of-life, staffing, state regulations, transition

Short Summary:

The specificity of state-level staffing regulations is associated with EOL transitions among ALC Medicare decedents. Policymakers may wish to set more explicit guidelines on staffing to help improve EOL quality of care.

INTRODUCTION

There are an estimated 31,400 assisted living communities (ALCs) with nearly 1 million licensed residential beds in the US.1 Most ALC residents are older,2 have multiple chronic conditions,3 cognitive impairment,3 and physical limitations,3 and often need medical services.2–4 For many ALC residents, this is likely their last home.5

In addition to room and board, ALCs offer services that are largely personal and supportive in nature.2 Not all ALCs have licensed staff, and relatively few offer any medical services.2 Although in recent years the ALC model has been evolving to accommodate some of their residents’ medical care needs, only a few communities provide some on-site medical care. Personal and supportive care in ALC is provided by the direct care workers (DCWs), i.e., mainly personal care aids and certified nurse assistants (CNAs). Most DCWs are largely untrained in providing care at the end-of-life (EOL).6,7

In other long-term care settings such as nursing homes (NHs), EOL care transitions occurring in the last month of life have been frequent, affecting at least a quarter of the decedents, and are considered markers for poor EOL care quality.8–10 In this setting, care transitions occurring very close to death, involving repeated hospitalizations, and for specific diagnoses, have been termed as “burdensome”, because they interrupt established care processes,8 increase unmet needs,8 and are thought to be disturbing for individuals and family members, without improving quality.8,11,12

Very little is currently known about the nature or frequency of EOL transitions among ALC decedents. One study found significant state variations in EOL trajectories among ALC residents.13 Geographic variations in EOL transitions in ALCs have also been documented, with state-to-state variations ranging from 8.9% in Wyoming to 30.9% in North Dakota.14 Another study echoed this finding by suggesting that in states with greater ALC regulatory specificity, residents experience fewer hospitalizations.15 A study on place of death in ALCs showed an association between state-level ALC regulatory stringency and the likelihood of dying in ALCs versus in an institutional care setting such as a hospital or nursing home.5 Another study documented an association between deaths in ALC and state hospice regulations.16 Yet, to date, variations in EOL care transitions in ALCs and their possible association with relevant state regulations have not been examined.

Motivated by these gaps in the literature, our study objectives were to examine: 1) the frequency and type of care transitions occurring among ALC decedents; and 2) the association between the specificity of state-level staffing and training regulations and the frequency of these transitions, while controlling for resident, ALC, and market-level factors. Although we hypothesized that greater specificity in these state regulations may affect EOL care transitions among ALC decedents, we did not posit the direction of these associations.

METHODS

Data Sources

We used multiple sources of data. First, we identified a cohort of Medicare beneficiaries who in calendar year (CY) 2018-2019 were known to reside in ALCs located across the US. 17–18 The information on ALC residents’ Medicaid enrollment, Medicare Advantage (MA) plan enrollment, demographic characteristics, chronic conditions, and validated dates of death was obtained from the 2018-2019 Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary Files (MBSF). We also used CY2018-2019 Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files and the Minimum Dataset 3.0 (MDS) to identify transfers (including those for MA plan enrollees) between ALCs and other care settings. Decedent’s hospice enrollment status was retrieved from hospice claims. Area Health Resource Files (AHRF) were used to obtain market-level information.19 Hospital care intensity index was acquired from the 2018 Dartmouth Atlas Project.20 Information on state ALC staffing and training regulations was derived from a previously obtained state regulatory dataset.17

Analytical Sample

We identified 113,662 Medicare beneficiaries who resided in ALCs and had validated death dates in 2018-2019. We excluded residents who died in the first 2 months of 2018, because for them we did not have 2017 hospice claims to identify hospice use or inpatient hospice admissions that preceded death (N=5,082). Decedents younger than 55 years of age (N=496),5 and those with missing information on variables of interests (N=3,038) were also excluded. In order to account only for care transitions that occurred while a decedent resident was in their ALC and received services from ALC staff, we excluded all those who died elsewhere (N=46,437). The final analytical sample included 11,448 ALCs and 58,609 Medicare decedents who died in ALCs.

Outcome Variable

Our outcome variables were the number of EOL care transitions during the last 7 days and the last 30 days before death. The focus on 7- and 30-days prior to death is somewhat arbitrary, and other studies focused on as few as 3 and as long as 90 days.10,14,21 We chose 7 days to examine transitions when death was imminent and perhaps more easily predictable, and 30 days when prognosticating imminent death was more difficult. We defined a transition as any transfer from ALC to another setting, including hospital, nursing home, inpatient hospice, or a transfer to another ALC. A return to the original ALC of residence from any of these care settings was also counted as a transfer. Prior research on EOL care, particularly in nursing homes, focused on “burdensome” transitions.8 We chose to use a simpler operational definition for this study, as specified above, by only looking at the number or frequency of transitions that occurred at EOL. This is mainly because very little is currently known about any EOL care transitions in this setting. Furthermore, unlike nursing homes, ALC are not healthcare providers and may not be able to cope with patients at the EOL thus transferring them to other settings. At the same time, any transitions that happen when death is imminent are likely to be disturbing or upsetting to patients and their families.

Key Independent Variables

State ALC regulatory specificity for licensed and DCW staffing, and DCW training, were the key variables of interests. Regulatory specificity reflects the level of detail contained in the state regulations. 5,17 For example, some states have no minimum staffing requirements, others require staff to be on site 24/7 but do not mandate staff type or specific numbers, yet others may specify staff numbers or mandate the staff ratio to be in proportion to the residents. Using the 2019 state regulatory databases, and following prior practice, 5,17 we dichotomized state regulations as nonspecific (e.g., when regulation about staffing levels was absent or nonspecific) versus specific (e.g., when regulation specified the number of staff or required staff to be proportional to residents) (supplemental Table S1).

Other Covariates

To control for individual-level characteristics that could be correlated with EOL care transitions, we included the following resident-level covariates: age at death, gender (male/female), race (categorized as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other (e.g., Asians, Pacific Islanders), enrollment in MA plans, Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (dual-eligible), length of ALC residence (months), and hospice enrollment in the last 7 and 30 days of life.

Following a prior study, and to control for ALC resource availability and practices that may impact EOL quality of care,5 we constructed several ALC-level characteristics: median resident age, bed size (dichotomized at median as below or above 82 beds), proportion of dual-eligible residents, proportion of residents with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), and proportion of residents with mental illness (i.e., bipolar disorder, personality disorders, and schizophrenia).

To control for area-level health resource availability, which may impact patient transfers or care quality,5 we included area-level factors such as: metropolitan status based on the ALC 5-digit zip codes; and county-level number of hospitals, nursing homes, and ALC beds per 1,000 persons aged 75 years. To account for variations in regional practices that may influence EOL care provision,21,22 we also included the hospital care intensity index by hospital referral region.20

Statistical Analyses

We calculated the summary statistics for the variables of interest, reported by whether an EOL transition occurred during the last 7 days and 30 days before death. Student’s t-tests and Chi-square tests were employed to test for the differences between the two groups.

We employed separate generalized linear regression models to examine the association between the state regulatory specificity and the number of EOL transitions in the last 7 days and 30 days of life, controlling for all other covariates. To adjust for the zero-truncation nature of the count data and the overdispersion of variance that violates the assumption of Poisson distribution, we adopted negative binomial regressions with log-link functions.22 We also adjusted for the hierarchical nature of the data by including ALC-level random effects.

Sensitivity Analysis

Because our primary analyses included ALC Medicare Advantage enrollees, for whom the MBSF may not provide accurate information on chronic conditions, we did not include individual-level chronic conditions as risk factors in the main analysis. To examine if this exclusion made a difference, we repeated the analyses with only the fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries for whom chronic conditions are available in the MBSF. Since ED visits that do not result in a hospital admission are available for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in Medicare outpatient claims, we also included emergency department (ED) visits as part of the EOL transitions count to see if the exclusion of ED visits in the original measure impacted the results (supplemental Table S2).

All analysis were performed using statistical software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC) and Stata 16.0 (StataCorp LLC; College Station, TX). Plots were generated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria). This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

In Table 1, we depicted the characteristics of ALC decedents who had at least one EOL transitions during the last 7 or 30 days of life. In the last 30 days of life, 34.89% (N=20,450) of ALC decedents had at least one EOL transitions, and 17.25% (N=10,111) had an EOL transition during the last 7 days before death. The mean and standard deviations for the number of transitions in the last 7 and 30 days of life are 1.4 ± 0.6 and 1.8 ± 1.0, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient-, Assisted Living Communities (ALC)-, and Area-Level Characteristics by whether an EOL Transition was Identified During the Last 7/30 Days Before Death, CY2018-2019.

| Variables | At Least 1 Transition During 7 Days Before Death (N=10,111, 17.25%) | At Least 1 Transition During 30 Days Before Death (N=20,450, 34.89%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or % | |||

| Outcome Variables | |||

| Transitions in last 7 days | 1.4 ± 0.6 | NA | NA |

| Transitions in last 30 days | NA | 1.8 ± 1.0 | NA |

| Patient-Level Characteristics | |||

| Age | 87.0 ± 8.3 | 87.2 ± 8.1 | 0.003 |

| Race, % | 0.035 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 93.8 | 93.4 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.6 | 2.9 | |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 3.6 | 3.7 | |

| Female, % | 60.8 | 61.0 | 0.567 |

| Medicare Advantage, % | 30.8 | 32.1 | <0.0001 |

| Dual-Eligible, % | 19.0 | 16.4 | <0.0001 |

| Length of ALC Stay (Months) | 33.9 ± 28.0 | 32.7 ± 27.8 | <0.0001 |

| Hospice Enrollment (30 Days Before Death), % | 3.5 | 6.4 | <0.0001 |

| Hospice Enrollment (7 Days Before Death), % | 8.7 | 35.5 | <0.0001 |

| ALC-Level Characteristics | |||

| Median Resident Age | 85.6 ± 5.6 | 85.7 ± 5.5 | 0.001 |

| Bed Size, % | 0.090 | ||

| ⩽82 Beds | 44.0 | 43.4 | |

| >82 Beds | 56.0 | 56.6 | |

| Dual-Eligible Residents, % | 21.8 ± 29.7 | 20.2 ± 28.6 | <0.0001 |

| Residents with ADRD, % | 55.7 ± 15.7 | 54.6 ± 15.9 | <0.0001 |

| Residents with Mental Conditions, % | 20.2 ± 16.0 | 19.3 ± 15.6 | <0.0001 |

| Area-Level Characteristics | |||

| Metropolitan Status, % | 91.1 | 90.6 | 0.006 |

| County Hospital Beds Per 1,000 Persons Aged 75+ | 51.3 ± 31.8 | 51.8 ± 32.0 | 0.029 |

| County Nursing Home Beds Per 1,000 Persons Aged 75+ | 1.5 ± 6.0 | 1.6 ± 6.7 | 0.054 |

| County ALC Beds Per 1,000 Persons Aged 75+ | 88.4 ± 60.5 | 92.7 ± 64.6 | <0.0001 |

| Hospital Care Intensity Index | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 |

| State Staffing Requirements | |||

| Licensed Staffing, % | 0.001 | ||

| -Not Specifically Required | 74.9 | 75.5 | |

| -Specific Requirements | 25.1 | 24.5 | |

| DCW Staffing, % | <0.0001 | ||

| -Not Specifically Required | 17.3 | 18.7 | |

| -Specific Requirements | 82.7 | 81.3 | |

| DCW Training, % | <0.0001 | ||

| -Not Specifically Required | 33.9 | 29.4 | |

| -Specific Requirements | 66.1 | 70.6 | |

Note:

Abbreviations: EOL, End-of-Life; ALC, Assisted Living Community; ADRD, Alzheimer Diseases and Related Dementias; DCW, Direct Care Workers.

Compared with those who had transitions in the last 30 days of life, ALC decedents with EOL transitions in the last 7 days of life tended to be younger (87.0 vs. 87.2; P=0.003), less likely to be enrolled in the MA plans (30.8% vs. 32.1%; P<0.0001), more likely to be duals (19.0% vs. 16.4%; P<0.0001), and less likely to have hospice enrollment during the last 7 days of life (8.7% vs. 35.5%; P<0.0001). Decedents with 7-day transitions tended to live in ALCs with more residents with ADRD (55.7% vs. 54.6%; P<0.0001) and more residents with mental conditions (20.2% vs. 19.3%; P<0.0001). They live in ALC located in metropolitan counties (91.1% vs. 90.6; P=0.006) and with fewer county-level ALC beds (88.4 vs. 92.7; P<0.0001).

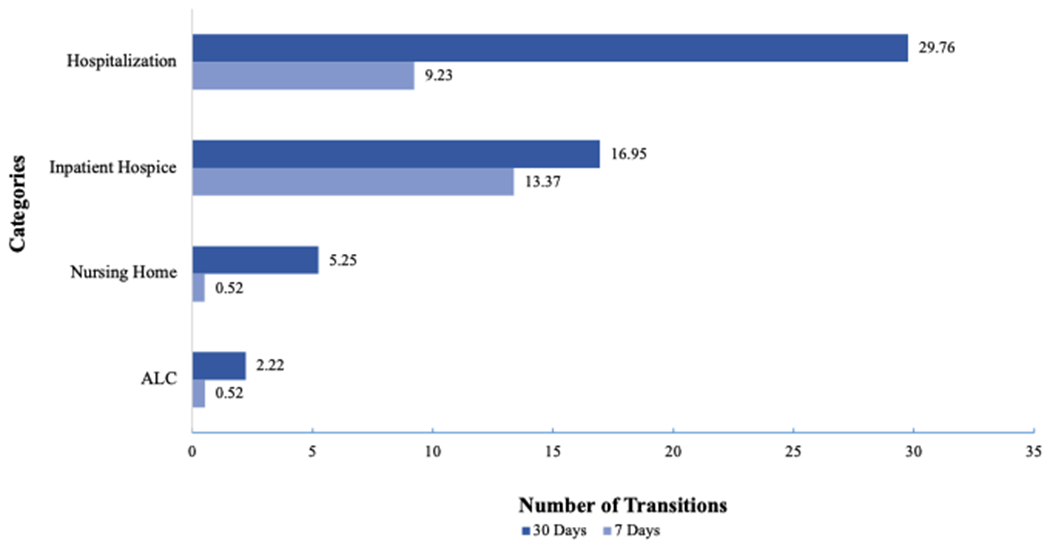

Hospitalizations were the most frequent transitions in the last 30 days of life (29.76 per 100 ALC decedents), as depicted in Figure 1. Next most frequent were inpatient hospice transfers (16.95), followed by NH transfers (5.25), and transfers to another ALC (2.22). However, for transitions in the last 7 days, transfers to inpatient hospice were more frequent (13.37) followed by transfers to hospitals (9.23), NHs (0.52), or ALCs (0.52).

Figure 1. Graphic illustration of the average number of EOL transitions occurred among every 100 assisted living community (ALC) Medicare decedents in each transition category, CY2018-2019.

Each bar represents the number of transitions per 100 ALC Medicare decedents for that category. Transitions happened in 7/30 days are reported separately. Source: Authors’ analysis of Medicare claims data. Abbreviations: ALC, assisted living communities.

State-level variations in the average number of EOL transitions per 100 ALC decedents during the last 7 and 30 days of life are depicted in the supplemental Figures S1 and S2, respectively. The pattern of variations in EOL transitions across states is consistent for these two outcomes.

Multivariable Analyses

Controlling for all other factors, decedents with fewer EOL transitions in the last 7 days of life were more likely to be younger (Incidence Risk Ratio, IRR=1.00; P=0.011), non-Hispanic Black (IRR=0.76; P<0.0001) or other race (IRR=0.74; P<0.0001), MA plan enrollees (IRR=0.81; P<0.0001), and with a shorter length of ALC stay (IRR=0.99; P<0.0001) (Table 2). Dual-eligible status was associated with higher frequency of EOL transitions in the last 7 days (IRR=1.34, P<0.0001), but hospice enrollees had significantly fewer transitions in the last 7 days (IRR=0.05; P<0.0001). Decedents from ALCs with a higher proportion of older residents or diagnosed with ADRD had more 7-day EOL transitions (IRR=1.01; P<0.0001 and IRR=1.06; P<0.0001, respectively).

Table 2.

Regression Analyses of the Number of End-of-Life (EOL) Transitions among Assisted Living Community (ALC) Medicare Decedents, CY2018-2019.

| Variables | EOL Transitions During 7 Days Before Death | EOL Transitions During 30 Days Before Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 95% CI | P-Value | IRR | 95% CI | P-Value | ||

| Patient-Level Characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.01) | 0.011 | 0.99 | (0.99. 0.99) | <0.0001 | |

| Female Gender | 1.08 | (1.04, 1.12) | <0.0001 | 1.02 | (0.99, 1.05) | 0.076 | |

| Medicare Advantage | 0.81 | (0.78, 0.85) | <0.0001 | 0.82 | (0.80, 0.84) | <0.0001 | |

| Race | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.76 | (0.67, 0.86) | <0.0001 | 0.94 | (0.88, 1.02) | 0.141 | |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 0.74 | (0.67, 0.82) | <0.0001 | 0.83 | (0.78, 0.89) | <0.0001 | |

| Dual-Eligible | 1.34 | (1.25, 1.43) | <0.0001 | 1.19 | (1.14, 1.25) | <0.0001 | |

| Length of ALC Stay (Months) | 0.99 | (0.99, 0.99) | <0.0001 | 0.99 | (0.99, 0.99) | <0.0001 | |

| Hospice Enrollment4 | 0.05 | (0.05, 0.06) | <0.0001 | 0.09 | (0.08, 0.09) | <0.0001 | |

| ALC-Level Characteristics | |||||||

| Median Resident Age | 1.01 | (1.00, 1.02) | <0.0001 | 1.01 | (1.00, 1.01) | <0.0001 | |

| Bed Size (>82 Beds) | 0.97 | (0.93, 1.01) | 0.119 | 0.99 | (0.96, 1.02) | 0.622 | |

| Proportion of Dually Eligible Residents2 | 0.99 | (0.98, 1.00) | 0.061 | 0.99 | (0.98, 1.00) | 0.187 | |

| Proportion of Residents with ADRD2 | 1.06 | (1.04, 1.08) | <0.0001 | 1.04 | (1.03, 1.05) | <0.0001 | |

| Proportion of Residents with Mental Conditions2 | 1.00 | (0.98, 1.02) | 0.91 | 0.99 | (0.98, 1.01) | 0.656 | |

| Area-Level Characteristics | |||||||

| Metropolitan Status | 1.15 | (1.06, 1.23) | <0.0001 | 1.11 | (1.05, 1.17) | <0.0001 | |

| Hospital Beds Per 1,000 Persons Aged 75+ | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.00) | 0.54 | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.00) | 0.030 | |

| Nursing Home Beds Per 1,000 Persons Aged 75+ | 0.99 | (0.99, 1.00) | 0.062 | 0.99 | (0.99, 1.00) | 0.349 | |

| ALC Beds Per 1,000 Persons Aged 75+ | 0.99 | (0.99, 0.99) | <0.0001 | 0.99 | (0.99, 0.99) | <0.0001 | |

| Hospital Care Intensity Index | 1.34 | (1.24, 1.46) | <0.0001 | 1.33 | (1.26, 1.41) | <0.0001 | |

| State Staffing Requirements | |||||||

| Licensed Staffing | |||||||

| Not Specifically Required | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Specific Requirements | 1.08 | (1.03, 1.13) | 0.002 | 1.03 | (0.99, 1.06) | 0.136 | |

| DCW Staffing | |||||||

| Not Specifically Required | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Specific Requirements | 1.22 | (1.15, 1.28) | <0.0001 | 1.15 | (1.11, 1.19) | <0.0001 | |

| DCW Training | |||||||

| Not Specifically Required | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Specifically Required | 0.75 | (0.72, 0.78) | <0.0001 | 0.79 | (0.76, 0.81) | <0.0001 | |

Note:

Abbreviations: EOL, End-of-Life; ALC, Assisted Living Community; ADRD, Alzheimer Diseases and Related Dementias; DCW, Direct Care Workers; IRR, Incidence Risk Ratios.

Reported on a scale of every 10% increase.

Both models were controlled for ALC-level random effects. Negative binomial models were constructed to account for the overdispersion of variances in the outcome variable.

For 7-day outcomes, hospice coverage during the last 7 days of life was used; For 30-day outcomes, hospice coverage during the last 30 days of life was used.

Likelihood ratio test of the overdispersion parameter on 7-day transitions: χ2=254.98, P<0.0001; On 30-day transitions: χ2=309.24, P<0.0001; Overdispersion in the outcome variable were identified in both models and negative binomial regression is warranted.

Higher frequency of 7-day transitions was associated with greater specificity of state AL regulations for licensed (IRR=1.08; P=0.002) and DCW staffing (IRR= 1.22; P<0.0001). However, in states with greater specificity in DCW training, decedents had 25% fewer EOL transitions (IRR=0.75; P<0.0001). Results from EOL transitions during the 30 days before death were, overall, similar to findings from the 7-day time window, albeit licensed staffing was not statistically significant (IRR=1.03; P=0.136).

The results of the sensitivity analysis, based only on the Medicare FFS ALC decedents, were reported in supplemental Table S2. Inclusion of individual-level chronic conditions as control variables, and of ED visits as part of the outcome variable, did not measurably alter the associations between state regulatory specificity and EOL care transitions, as presented above.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined patterns of EOL care transitions among Medicare beneficiaries who died in ALCs, and their associations with state staffing and training regulations. As expected, individuals enrolled in hospice care had significantly fewer EOL care transitions. Although not quite of the same magnitude, we found a similar association for enrollees of the MA plans. Higher transition risk was present among the dually eligible residents. Consistent with prior studies in other care settings,23,24 hospitalization was the most frequent EOL transition in the last 30 days of life. The surprising finding was the relatively high number of transfers to inpatient hospice (compared to other care transitions) occurring within both the last 7 and 30 days of life. Over 80% of ALC residents who died at home (i.e., in ALC) are known to have been enrolled in hospice.5 This makes the relatively frequent transfers to inpatient hospice in this population both surprising and concerning.

Furthermore, we found significant state-level variations in the frequency of EOL transitions for both 7- and 30-day periods preceding death. This is also consistent with prior literature, 14 but our study is the first to attribute these variations to regulatory specificity. Decedents from ALCs located in states with more specific DCW training regulation had fewer EOL transitions in both 7- or 30- day periods, compared with states with lower specificity. However, in states with greater regulatory specificity for licensed and DCW staff requirements, decedents experienced higher frequency of EOL transitions during the last 7 days of life. States with higher ALC regulatory staffing specificity tend to require ALCs to be staffed in proportion to the residents they serve. These findings make intuitive sense. On one hand, when ALCs have licensed staff or even simply more DCW staff, they have greater opportunity to identify increasing care needs of residents whose health status declines, thus precipitating care transitions to higher care settings.25 On the other hand, when DCWs are required to have more training, they may be better equipped to identify residents with higher care needs earlier and arrange for the care to be provided within the ALC, thus preventing potentially avoidable transitions.26

Our finding that more specific staffing requirements were associated with fewer EOL transitions echoes similar results from studies that examined care transitions and hospitalizations in long term care settings.27–30 Proper training and licensing requirement for staff have also been found to be associated with a number of quality outcomes in ALCs.15,27,31 Specifically, one study found that increased regulatory specificity for DCWs was associated with a 4% decrease in the monthly risk for hospitalization among ALC residents, and an increase in regulatory specificity for licensed practical nurses was associated with a 2.5% increase in hospitalization.27 Another study showed ALC decedents with explicit state-level registered nurse staffing requirements had significantly less continuous home care use.15 Our study adds to the current knowledge by showing that more explicit staffing requirements were associated with the frequency of EOL transitions among ALC decedents, albeit directions may vary for specific policy items.

Several implications can be drawn from this study. On February 28th, 2022, President Biden announced plans to establish minimum staffing requirements in nursing homes as a way to improve safety and quality of care.32 Our results suggest that similar efforts may also be needed for ALC settings to achieve better performance at EOL. Since ALCs are largely regulated by states, state government officials and law makers may want to revisit their ALC staffing licensing and training regulations to set more specific requirements in these domains for quality improvement. Moreover, our study highlights the importance of ALC staffing and training in EOL quality of care. Although ALCs usually do not have medical staff on site,2 proper staff training among the DCWs may be beneficial in identifying residents’ needs and improving EOL care quality.

Our study has several limitations. First, because we had no access to Medicare Advantage encounter data, we could not include emergency room visits in the count of EOL transitions in the main analysis. Second, omitted variable bias may be a concern. Specifically, since the information on ALCs and their residents is largely absent from public datasets, we were not able to account for several potentially important factors, e.g., functional status of ALC residents. Our inclusion of personal-level chronic conditions in the sensitivity test and the aggregation of ALC-level variables from individual data may help minimize this concern to some extent.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

In conclusion, our study found that the frequency of EOL transitions among ALC Medicare decedents was associated with state staffing and training requirements. Specific requirements on DCW training may help decrease the number of transitions in the immediate period prior to death, while more explicit licensed staffing and DCW staffing regulations may increase transition frequency. Government officials and ALC administrators may consider setting more explicit guidelines for ALC staffing and training to help improve EOL quality of care.

Supplementary Material

Funding Sources:

This study was funded by grants from the AHRQ (R01HS026893) and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation, Another Look 2020.

Footnotes

Previous Presentations: A version of the study findings was presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, on June 6th, 2022, in Washington, D.C.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States, 2017–2018.; 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03-047.pdf [PubMed]

- 2.Zimmerman S, Carder P, Schwartz L, et al. The Imperative to Reimagine Assisted Living. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022; 23(2):225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman S, Guo W, Mao Y, Li Y, Temkin-Greener H. Health Care Needs in Assisted Living: Survey Data May Underestimate Chronic Conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(2):471–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Mao Y, McGarry B, Temkin-Greener H. Post-acute care transitions and outcomes among medicare beneficiaries in assisted living communities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 70(5):1429–1441. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temkin-Greener H, Guo W, Hua Y, et al. End-Of-Life Care In Assisted Living Communities: Race And Ethnicity, Dual Enrollment Status, And State Regulations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(5):654–662. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon S, Fortner J, Travis SS. Barriers, challenges, and opportunities related to the provision of hospice care in assisted-living communities. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2002;19(3):187–192. doi: 10.1177/104990910201900310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohlman WL, Dassel K, Supiano KP, Caserta M. End-of-Life Education and Discussions With Assisted Living Certified Nursing Assistants. J Gerontol Nurs. 2018;44(6):41–48. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20180327-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-Life Transitions among Nursing Home Residents with Cognitive Issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1100347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lage DE, DuMontier C, Lee Y, et al. Potentially burdensome end-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with poor-prognosis cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1322–1329. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SC, Lima JC, Intrator O, Martin E, Bull J, Hanson LC. Palliative Care Consultations in Nursing Homes and Reductions in Acute Care Use and Potentially Burdensome End-of-Life Transitions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2280–2287. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, et al. Churning: the association between health care transitions and feeding tube insertion for nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):359–362. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palan Lopez R, Mitchell SL, Givens JL. Preventing Burdensome Transitions of Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia: It’s More than Advance Directives. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(11):1205–1209. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas KS, Belanger E, Zhang W, Carder P. State Variability in Assisted Living Residents’ End-of-Life Care Trajectories. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(3):415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XJ, Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Dosa D, Thomas KS, Bélanger E. State Variation in Potentially Burdensome Transitions Among Assisted Living Residents at the End of Life. JAMA Intern Med. JAMA Intern Med. 2022. Feb 1;182(2):229–231. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belanger E, Teno JM, Wang XJ, et al. State Regulations and Hospice Utilization in Assisted Living During the Last Month of Life. J Am Med Dir Assoc. Published online December 28, 2021:S1525-8610(21)01065-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belanger E, Rosendaal N, Wang XJ, et al. Association Between State Regulations Supportive of Third-party Services and Likelihood of Assisted Living Residents in the US Dying in Place. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(10):e223432. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temkin-Greener H, Mao Y, Ladwig S, Cai X, Zimmerman S, Li Y. Variability and Potential Determinants of Assisted Living State Regulatory Stringency. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2021, 22(8):1714–1719e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.10.014. Epub 2020 Nov 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Temkin-Greener H, Mao Y, Li Y, McGarry B. Using Medicare Enrollment Data to Identify Beneficiaries in Assisted Living. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023, 24(3):277–283. PMCID: PMC9391528. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.01.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Area Health Resources Files. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf

- 20.Dartmouth Atlas Project. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.dartmouthatlas.org/

- 21.Miller SC, Lima JC, Intrator O, Martin E, Bull J, Hanson LC. Specialty Palliative Care Consultations for Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(1):9–16.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinde J, Demétrio CGB. Overdispersion: Models and estimation. Comput Stat Data Anal. 1998;27(2):151–170. doi: 10.1016/S0167-9473(98)00007-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teno JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, et al. Site of Death, Place of Care, and Health Care Transitions Among US Medicare Beneficiaries, 2000-2015. JAMA. 2018;320(3):264–271. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, et al. Transitions Between Healthcare Settings Among Hospice Enrollees at the End of Life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):314–322. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stearns SC, Park J, Zimmerman S, Gruber-Baldini AL, Konrad TR, Sloane PD. Determinants and effects of nurse staffing intensity and skill mix in residential care/assisted living settings. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(5):662–671. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cartwright JC, Miller L, Volpin M. Hospice in assisted living: promoting good quality care at end of life. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(4):508–516. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas KS, Cornell PY, Zhang W, et al. The Relationship Between States’ Staffing Regulations And Hospitalizations Of Assisted Living Residents. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(9):1377–1385. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Temkin-Greener H, Yan D, Wang S, Cai S. Racial disparity in end-of-life hospitalizations among nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(7):1877–1886. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orth J, Li Y, Simning A, Zimmerman S, Temkin-Greener H. End-of-Life Care among Nursing Home Residents with Dementia Varies by Nursing Home and Market Characteristics. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(2):320–328.doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xing J, Mukamel DB, Temkin-Greener H. Hospitalizations of nursing home residents in the last year of life: nursing home characteristics and variation in potentially avoidable hospitalizations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):1900–1908. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beeber AS, Zimmerman S, Reed D, et al. Licensed nurse staffing and health service availability in residential care and assisted living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):805–811. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.FACT SHEET: Protecting Seniors by Improving Safety and Quality of Care in the Nation’s Nursing Homes. The White House. Published February 28, 2022. Accessed March 26, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/02/28/fact-sheet-protecting-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities-by-improving-safety-and-quality-of-care-in-the-nations-nursing-homes/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.