Abstract

Two major problems for the vapor injection heat pump systems with the flash tank are the high discharge temperature and the lack of flash tank design theoretical basis, which would limit its wide application in extreme operating conditions. One possible way to overcome these problems is to effectively control the two-phase injection in the flash tank by optimizing its structure. The use of the proposed novel flash tank in the quasi-two-stage vapor injection cycle represents an economic and controllable solution. This research experimentally analyzes the influences of flash tank structure and volume on the system heating performance under different compressor frequencies and injection pressures at the ambient temperature of −10 °C. The comparative analysis is done finding that the novel flash tank could maximumly improve the system Coefficient of Performance (COPh) by 6.4% in this test, compared with the traditional type A flash tank cycle. In the meanwhile, a bad design of novel flash tank size could represent a loss of COPh improvement between 5.73% and 13.5%. Due to the particular structure, the implementation of the novel flash tank also allows the injection mass flow ratio can keep a linear relationship with the injection pressure. Moreover, the refrigerant liquid can be regularly injected into the compression chamber to control discharge temperature under 100 °C. From all the analysis, guidelines for optimizing the control strategy and the flash tank design are put forward, which can be used to perfect the real thermodynamic model of the flash tank rather than the ideal two-phase separation model.

Keywords: Refrigerant injection, Novel flash tank, Heat pump, Heating capacity, Energy equipment

1. Introduction

The air-source heat pumps (ASHP) have been proved to be an energy-efficient way to utilize low-grade renewable energy [1] in cold regions. However, the drastic decrease in the heating performance of the ASHP in winter would limit its wide application due to the high discharge temperature and reduced volumetric heating capacity.

To keep the heat pump working efficiently and steadily, lots of studies, such as internal heat exchangers [2], mixed refrigerants [3,4], vapor injection [5], multi-energy coupled heat pumps [6,7], two-stage compression [8], inverter frequency technology [9] and so on, have been conducted to improve the ASHP heating performance at low ambient temperatures. In the past decades, the research results show that the vapor injection (VI) technology represents an economical and effective solution to control the discharge temperature and improve the COPh in extreme conditions [10]. The VI technology has been applied to air-conditioning equipment since 1979 [11]. Later, deeper research taking into account the system construction is done finding that injecting the medium-pressure refrigerant vapor into the intermediate compression process allows some energy saving and isentropic efficiency improvement by achieving two-stage compression or quasi-two-stage compression [12,13]. The flash tank or economizer (sub-cooler) was the necessary additional component for the typical vapor injection configuration to obtain injecting vapor [5]. To study the effects of vapor injection with different features, the improvement of heating performances is investigated comprehensively through numerical simulation [[14], [15], [16]] and experiment [10,12,[17], [18], [19]].

Due to the refrigerant injection, experiments with different schemes and different working fluids confirm that the vapor injection has an excellent cooling effect on the compressor discharge temperature [20] and there exists a significant improvement [[21], [22], [23]] in the vapor injection system heating capacity and COPh compared with the conventional single-stage vapor compression (CSVC) cycle at low ambient temperature. Moreover, the researchers also analyzed and studied the effect of main control factors, such as the optimal injection pressure and injection ratio of the sub-cooler vapor injection cycle (SCVIC) [24], and concluded that the optimal parameter value changes with the ambient temperature. Nevertheless, Ma and Zhao (2008) [25]experimentally verified that the flash tank vapor injection cycle (FTVIC) is better than the SCVIC [26], and could gain about 10.5% and 4.3% profit from the heating capacity and COPh, respectively, than those of the SCVIC under the same operating condition. Feng et al. (2009) [27] explored and found that vapor injection technology combined with a 15% R-600a mass ratio of mixed refrigerant can effectively improve the system heating capacity by 20%, increase the COPh by 15%, and reduce the exhaust temperature by up to 40 °C at the ambient temperature of −15 °C and the supply water temperature of 55 °C. Xu et al. (2013) [12] studied refrigerant injection effects in R-32 and R-410A systems with flash tank and concluded that R-32 is an excellent alternative to replace R-410A in terms of performance. However, the discharge temperature of the R-32 system would be relatively high at extreme conditions [28].

To speed up the analysis, numerical simulation is a practical and economical method to analyze the cycle heating performance [29,30] and predict the best design parameters of the research object under specific working conditions before experimental research [31]. However, necessary simplification and assumptions are still needed to build the component model, compared with the real processes. Qiao et al. (2015) [32] establish a transient model of the FTVIC by assuming the ideal gas-liquid separation without heat transfer in the flash tank, and found the opening of the upstream electronic expansion valve (EEV) has a more significant impact on the system performance and the liquid level in the flash tank [33]. Redón et al. (2014) [34]also build the flash tank model of two-stage compression with the ideal two-phase separation process. Lee et al. (2013) [17] proposed a saturation cycle model with flash tank by two-phase refrigerant injection, which could produce more benefits for the cycle with higher pressure ratio [13]. A part of liquid refrigerant is assumed to mix with the separated vapor to meet the injection mass flow rate in the saturation cycle model.

Previous research works mostly focused on the cycle heating performance variations with different compressors, injection components [35], and parameters of the compressor injection hole [15]. However, the design and control strategy of the flash tank are also the key factors [5] that determine the heat pump's heating performance. For the isothermal separation process in flash tank working with pure fluid, the degree of superheating cannot be obtained to be used as the feedback signal. Therefore, Qiao et al. (2015) [32] and Xu et al. (2011) [36] add electric heating equipment to the vapor injection pipeline so that the injection vapor is heated to achieve the degree of superheating (4-6k). The same control signal was also created by a hybrid economizer [37]. Moreover, Minh et al. (2006) [38] control the upstream electronic expansion valve with the liquid level of the flash tank.

The studies mentioned above indicated that the working efficiency of the flash tank could seriously affect the stability of system heating performance. Currently, there is little theoretical basis to support the design concept of flash tanks. The existing research mainly focused on improving system heating performance with different structures. However, Redón et al. (2014) [34] thermodynamic analyzed the influence of design parameters on two-stage vapor injection heat pump performance and found that a flawed system design of the FTVIC, such as the bad selection of compressor volumes, could cause a loss of COPh improvement between 6% and 10%. This research also concluded that there exists an optimum displacement ratio for the two-stage vapor injection cycle at the specific working condition. It means that the heating performance variation is related to the injection mass flow ratio, which is determined by the flash tank. For the distinct density difference between fluid and vapor, the bad control of liquid and vapor stream in flash tank might cause a significantly changing in the injection mass flow ratio due to some liquid fluid flowing to the injection pipe unpredictably. Moreover, Xu et al. (2011) [5] pointed out that the design of the flash tank was crucial to achieving high separation efficiency for the reliable system operation, and the flash tank needed to be well-sized depending on the capacity of the air conditioning/heat pump system. Although some optimized structures of the flash tank have been proposed, the two-phase separation models of flash tanks in the thermodynamic analysis are still mostly assumed as an ideal process in the above mention literature. Nevertheless, few experimental researchers have analyzed the influence of flash tank size on the system heating performance. In this study, a new structure of flash tank with different volumes was proposed, and the effects of flash tank volume and structure on the heating performance of the FTVIC were investigated. The experimental results could provide some theoretical basis for the design concept and the real model building of flash tank.

2. Design of flash tank

The novel flash tank (as shown in Fig. 1) is equipped with a spiral tube and uses the coupling effect of gravity and centrifugal force to strengthen the two-phase separation. There exists a conical surface to connect the vapor outlet pipe at the top of the spiral tube. To force two-phase fluid to achieve centrifugal movement, the gap between the spiral tube and the flash tank shell is smaller than 0.5 mm. When the two-phase refrigerant flows into the chamber located at the top of the flash tank, it will be distributed into four mixed fluids by the narrow spiral flow channels. As leaving the outside surface of the spiral tube, the mixed refrigerant would flow along the inner wall at the spiral angle. Due to the distinct density difference between fluid and vapor, the forced two-phase flow is separated at the bottom of the flash tank. Moreover, the vapor must flow downward along the spiral tube outside surface first and then float up to the vapor outlet along the spiral tube inner surface. The spiral channels inside the spiral tube still have effects on the two-phase separation by avoiding intense boiling. The vapor would keep centrifugal movement in the S-type form, which can slow down excessive fluctuation of liquid level. Therefore, the liquid level of flash tank and injection mass flow rate can be effectively controlled by two-phase injection. Meanwhile, when the liquid level of the flash tank is above the spiral tube bottom, the vapor will accumulate in the outside space of the spiral tube to force liquid injected into the compressor until the liquid level is lower than the spiral tube bottom once again or the pressure difference between two-phase inlet and vapor outlet is large enough to overcome the resistance of liquid height difference in the spiral tube. Once the vapor is discharged into the inner of the spiral tube, the liquid level in the spiral tube will be decreased and the liquid will also be again accumulated to rise the liquid level. Therefore, for the novel flash tank, the liquid injection is intermittent. Unlike the newly designed flash tank, the traditional flash tank (as shown in Fig. 2) does not have spiral flow channels. Only the gravity was used to complete the separation of the two-phase refrigerant for the traditional flash tank. According to the theory of boiling in a confined space, a part of liquid refrigerant may mix with the injection vapor in the traditional flash tank, especially at high injection pressure and high mass flow rate. On the contrast, heavy boiling in traditional flash tank would also prevent the injection mass flow rate from further increasing at high injection pressure, due to the fact that the separated vapor would always occupy the upper space of the flash tank. Therefore, based on the above analysis, the structures and sizes of flash tank effect on the system heating performance are studied in this paper. The specifications of flash tanks are illustrated in Table .1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the novel flash tank.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the traditional flash tank.

Table 1.

Specification of flash tanks.

| Type | Structure | Specifications |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outer diameter φ/mm | Length h1/mm | h2 /mm |

h3 /mm |

Number of spiral channels | Depth of spiral channel/mm | Width of spiral channel/mm | Helical angle α/° | Volume/cm³ | ||

| A | traditional | 50.00 | 150 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 245 |

| B | newly designed | 38.32 | 170 | 25 | 50 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 17.66 | 185 |

| C | newly designed | 28.76 | 175 | 25 | 50 | 4 | 5 | 3.5 | 17.66 | 88 |

3. Experimental setup and test procedure

3.1. Experimental setup

An experimental setup (as shown in Fig. 3) of air-air vapor injection heat pump with flash tank was built. This test unit adopts a DC variable-frequency single-cylinder vapor injection rotor compressor with a theoretical displacement of 10.8 cm³/rev−1. The tests in this paper are carried out in the national certified standard enthalpy difference laboratory. The thermomechanical analysis can be found in Fig. 4. The condensing liquid refrigerant from condenser will be measured by the mass flowmeter1 before flowing through the EEV1. Then the medium-pressure two-phase fluid produced by the upstream throttling process is separated into liquid and vapor refrigerant in flash tank. The mass flow rate of the separated liquid is measured by the mass flowmeter2 equipped on the pipe between the EEV2 and the liquid outlet of flash tank. After the second throttling process, the working fluid evaporates to the superheated vapor by absorbing the source energy in evaporator. For the quasi-two-stage compression, the low temperature injected vapor from flash tank will mix with the superheated vapor from evaporator in the compression chamber, which also effectively decreases the discharge temperature. Moreover, the upper-stage EEV1 and low-stage EEV2 are independently controlled by separate special controllers. The EEV1 mainly controls the injection pressure (Pinj); while in contrast, the EEV2 is equipped to keep the superheating degree of the compressor suction vapor automatically. To provide a stable condition for testing, the indoor and outdoor heat exchangers were installed separately in two closed environment chambers to measure the heat performance at the constant ambient temperature. The FTVIC could be changed to the CSVC system by closing the ball valve initialed on the injection pipe. Table .2 shows the specifications of the main components.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup.

Fig. 4.

Pressure-enthalpy diagram.

Table 2.

Specification of system components.

| Components | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Compressor | Type: inverter-driven rotary compressor; Displacement volume: 10.8 cm³•rev−1; The circle radius of cylinder: 21.5 mm; The rotor radius:17.05 mm; The length of the cylinder:20 mm; The diameter of injection hole:4 mm |

| Condenser (indoor heat exchanger) | Type: fin/tube heat exchanger (aluminum/copper), L-shaped; Tube outer diameter: Ø6.14 × 0.57 mm; Fin thickness: 0.1 mm; Fin spacing: 1.2 mm; Number of rows: 2; Number of tubes: 34; Dimension:700 × 360 × 26 mm |

| Evaporator (outdoor heat exchanger) | Type: L-shaped fin/tube heat exchanger (aluminum/copper); Tube outer diameter: Ø9.52 × 0.7 mm; Fin thickness: 0.1 mm; Fin spacing: 1.1 mm; Number of rows: 2; Number of tubes: 40; Dimension:880 × 510 × 45 mm |

| Electrical expansion valve | Type: electronic expansion valve Control resolution: 0–500 Steps |

3.2. Test condition

The FTVIC heating performance without frosting is studied in this paper. The working fluid is R-410A, which is the main currently used alternative refrigerant for heat pumps in China. The evaporator superheating degree is controlled by the EEV2 in the range of 3–5 K at all testing conditions. Moreover, the opening of the EEV1 is also adjusted to obtain the desired injection pressure. To compare the effects of different size flash tanks on the system heating performance, the amount of refrigerant charge is fixed at 1380 g. It is determined by debugging the CSVC system with the condenser subcooling degree of 4 K at the compressor frequency of 60 Hz, the ambient temperature of 7°Cand the indoor environment temperature of 20 °C, which is also the rated condition. The CSVC system could achieve a higher COPh compared with the FTVIC [18,39] at the rated condition. Table .3 shows the test condition during the experiments. The comparison tests of heating performance between the CSVC system and the FTVIC were comprehensively investigated at the ambient temperature of −10 °C by changing injection pressure and working frequency f. Considering that the suggested long-term working range of compressor frequency is between 10 and 110 Hz, the rated compressor frequency is set as the average value of 60 Hz. For deep research on the variation of the liquid level in the flash tank, the FTVIC with type B flash tank is also experimental studied by changing the ambient temperature from 7 °C to −15 °C.

Table 3.

Experiment conditions.

| Operating mode | Indoor |

Outdoor |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDB/°C | TWB/°C | TDB/°C | TWB/°C | ||

| heating | 20 | 15 | −10 | – | |

| Refrigerant type | R-410A | ||||

| Refrigerant charge | 1380 g | ||||

| Compressor frequency f in experiments | 60~100 Hz | ||||

| Injection pressure | 550~1500 kPa | ||||

| Superheating degree of the suction vapor | 3–5 K | ||||

3.3. Data analysis method

The FTVIC heating capacity, COPh, injection mass flow rate, injection mass flow ratio, and injection pressure ratio are calculated from Eqs. (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6). The compressor power W was measured by a power meter with an uncertainty of 0.5%FS. The total mass flow rate in condenser and mass flow rate in evaporator are all measured by the Coriolis mass flowmeters with the uncertainty of 0.1%FS. The refrigerant-side temperatures and pressures are recorded by the T type thermocouples and the ceramic membrane pressure transducers. The refrigerant flow rate in evaporator and condenser are also calculated and verified by energy balance. To obtain the air-side heating capacity, the enthalpy difference and air flow rate are calculated by measuring the dry-bulb and wet-bulb temperature at the inlet and outlet of the special air flue, and measuring the pressure difference in nozzle with a certain diameter. All the dry-bulb and wet-bulb temperatures are measured by the PT100 temperature sensor with an uncertainty of ±0.15 °C. Considering the extra power consumption from fans and electronic controllers, and the isentropic efficiency and mechanical efficiency of the compressor, the energy balance analysis is performed by Eqs. (7), (8).

Heating capacity

| (1) |

Coefficient of performance

| (2) |

Injection mass flow rate

| (3) |

The injection mass flow ratio

| (4) |

The injection pressure ratio

| (5) |

Air mass flow rate in the indoor environment

| (6) |

Energy balance in condenser

| (7) |

Energy balance in refrigerant-side

| (8) |

The uncertainty in the calculated quantity can be determined as the below equation.

| (9) |

The thermocouple, pressure transducer, temperature sensor, etc., were calibrated and installed in the experimental setup. Table .4 shows the measurement uncertainties of the main measured values and calculated values. Test data's accuracy is analyzed using the error propagation theory, including systematic and random errors. To reduce random errors, when the system state parameters on the air side and the refrigerant side remain stable for about 10 min, five measured values under the set conditions will be collected at an interval of 3 min. Moreover, the uncertainty of calculated value can be calculated from equation (9), where U represents the uncertainty of the variable. From the error analysis, the maximum uncertainty of the main parameters is about ±4.1%. The uncertainty of energy output in condenser and energy transfer through the reverse Carnot cycle are all within ±5% (as shown in Fig. 5(a) and Fig. 5(b)). The results indicated that the accuracy of test results could meet scientific research's needs.

Table 4.

Instrumentation and propagated uncertainties.

| No. | Instrument | Type | Range | Uncertainty | Obtaining Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thermocouple | T | −200-350 °C | ±0.5 °C | Measured value |

| 2 | Pressure transducer | Ceramic membrane | 0–4000 kPa | ±0.2% FS | Measured value |

| 3 | Pressure transducer | Ceramic membrane | 0–6000 kPa | ±0.2% FS | Measured value |

| 4 | Temperature sensor | platinum thermistor | −50-300 °C | ±0.15 °C | Measured value |

| 5 | pressure difference transducer | Diaphragm | 0–6 bar | ±0.075% FS | Measured value |

| 6 | power meter | – | 0–5 kW | ±0.5% FS | Measured value |

| 7 | Mass flowmeter1 | Coriolis mass Flowmeter FTM-1600 |

0–600 kg/h | ±0.1%FS | Measured value |

| 8 | Mass flowmeter2 | Coriolis mass Flowmeter FTM-1600 |

0–240 kg/h | ±0.1%FS | Measured value |

| 9 | Refrigerant-side heating capacity | – | – | ±1.54% | Calculated value |

| 10 | COPh | – | – | ±4.1% | Calculated value |

| 11 | Air-side heating capacity | – | – | ±3.03% | Calculated value |

Fig. 5.

(a) Energy balance in the condenser. (b) Energy balance in refrigerant-side.

4. Results and discussion

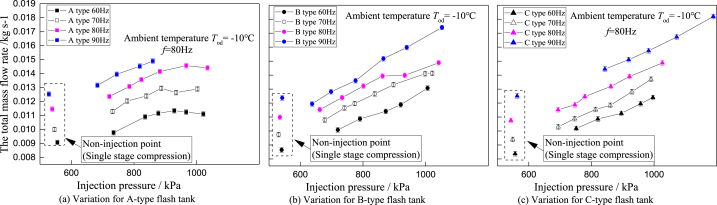

Fig. 6 shows the influence of the injection pressure on the heating capacity. For all the tested systems, the heating capacity increase firstly and then slightly decrease with the increase of injection pressure. This tendency is mainly owed to the rapid decrease in the superheating degree of discharge vapor and the subcooling degree at the condenser outlet. Although the total mass flow rate is improved for the novel flash tank cycle (the curve slope is shown in Fig. 14), its increasing ratio is still lower than the reduction ratio of the enthalpy difference between the refrigerant inlet and outlet of condenser (the slope as shown in Fig. 12 and Fig. 13). It also can be obtained that the heating capacity of type A flash tank cycle decreases faster than those of the novel flash tank systems at high injection pressure due to the strong bubble disturbance and the limited two-phase injection. On another hand, more deep explanations are the change in the system's total refrigerant mass flow rate (as shown in Fig. 14) and low heat exchange efficiency in the condenser affected by the high discharge vapor superheat degree (as shown in Fig. 12). Compared with the type A flash tank cycle, the novel type B and type C flash tank could improve the heating capacity by 5.47% and 2.42%, respectively at the compressor frequency of 70 Hz and the injection pressure of 1000 kPa.This also proves that the novel flash tank structure has a wide range to maintain a higher heating capacity with the purpose of controlling the discharge temperature.

Fig. 6.

Variation of heating capacity with injection pressure.

Fig. 14.

Variation of total mass flow rate with injection pressure at Tod = −10 °C.

Fig. 12.

Variation of discharge vapor superheating degree at Tod = -10 °C.

Fig. 13.

Variation of the subcooling degree with injection pressure at Tod = -10 °C.

The power consumption of the FTVIC presents a linear increasing trend with the injection pressure (as shown in Fig. 7). For the fixed ambient temperature, the density of the suction vapor at the inlet of the compressor will slightly be changed with the injection pressure. This also means that the refrigerant mass flow rate in evaporator is almost being kept at a certain value by ignoring the change in the volume efficiency. Therefore, the only reason to improve the total mass flow rate is the variation of injection mass flow rate. For the novel flash tank cycle, the improvement of total mass flow rate is higher than that of the type A flash tank cycle at high injection pressure due to the effective two-phase injecting or high intermittent liquid injection frequency. The power consumption of compressing the injection refrigerant to condenser pressure would significantly contribute to the total power consumption improvement with the injection pressure. The FTVIC could achieve an optimal COPh value at the optimized injection pressure (as shown in Fig. 8). When working at low injection pressure, the high heat exchange efficiency of evaporator absorbs more heating to improve the cycle COPh due to the low dryness of two-phase fluid at the evaporator inlet. While for the high injection pressure, the improvement of the heating capacity mainly comes from the increase of the power consumption, which will cause the reduction of the COPh. By experimental analysis, the system optimum injection pressure for the studied novel applications is between 770 kPa and 900 kPa, and increases with the compressor frequency. The heating performance comparison at optimum injection pressure under different compressor frequencies is shown in Fig. 9. Compared with the type A flash tank cycle, the type B flash tank could improve the system COPh by 6.4% at f = 60 Hz and 1.8% at f = 90 Hz when working at the optimum injection pressure. Considering the effect of the novel flash tank size, the COPh of the type B flash tank cycle is increased by 5.73% at compressor frequency of 60 Hz and 13.5% at compressor frequency of 90 Hz, relative to those of the type C flash tank cycle. Although the system COPh will decrease with the compressor frequency and the injection pressure (higher than the optimum injection pressure), the cycle heating capacity could be kept unchanged with the injection pressure as controlling the discharge temperature without shutting off the heat pump caused by the protection of high discharge temperature. This result also confirms that there exists a potential control logic optimization for the FTVIC with the novel flash tank.

Fig. 7.

Variation of power consumption W with injection pressure.

Fig. 8.

Variation of system COPh with injection pressure.

Fig. 9.

Cycle heating performance comparison at the optimum injection pressure.

Fig. 10 shows the variation of discharge pressure P1 with injection pressure. The system discharge pressure P1 decreases and then slightly increases with the rising of injection pressure. There are three reasons to explain this tendency from the aspects of heat exchange efficiency, heat transfer temperature difference, and conservation of mass. Firstly, with the rapid discharge vapor superheating degree and condenser subcooling degree decreasing, the improvement of the heat exchange efficiency automatically causes the decrease in the heat transfer temperature difference as well as the discharge pressure for the fixed condenser area. Secondly, the cooling effect in the compressor chamber improves with the injection ratio, which also affects the discharge pressure. According to the Clapeyron equation, the discharge pressure keeps a directly proportional correlation with the ratio between discharge temperature and the mixed chamber temperature for the volumetric compressor. Meanwhile, the discharge pressure should be kept above a certain value to transfer energy from refrigerant to indoor environment. The enhanced cooling effect would lead to a decrease in discharge pressure. The last reason for it is the conservation of mass in the flash tank. Although the total mass flow rate keeps increasing with injection pressure, the injection fluid will be changed from vapor to two-phase refrigerant, which causes a significant decrease in the system subcooling degree and discharge superheating degree. Therefore, the rapid two-phase injecting will also result in the increase of the injection mass flow ratio. In the compression process, the injected liquid will isothermally expand to vapor with the volume increasing by 20–40 times, which also causes the discharge pressure to increase. To keep the conservation of mass in flash tank, more condensing liquid with high subcooling degree will be produced by further improving the discharge pressure to meet the increase in the injection mass flow rate since the mass flow rate in evaporator approximately considering unchanged at the fixed compressor frequency.

Fig. 10.

Variation of system discharge pressure P1 with injection pressure.

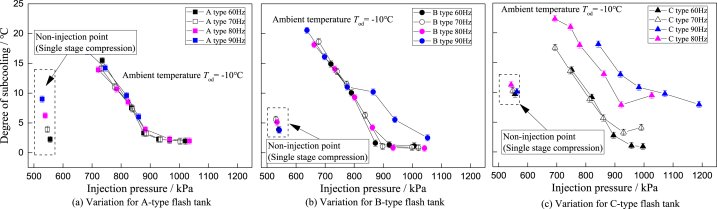

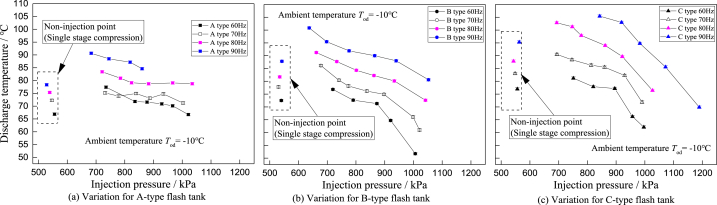

The variations of discharge temperature and discharge vapor superheating degree are shown in Fig. 11 and Fig. 12, respectively, and have a similar decline tendency with the injection pressure. As the injection pressure is high enough, the two-phase injection strengthens the cooling effect in the compressor mix chamber and also cools down the discharge temperature significantly. By the comparison of the discharge vapor superheating degree and the injection mass flow ratio (as shown in Fig. 15), it is more effective to control the two-phase separation and the two-phase injection for the novel flash tank. Although the type A flash tank also completes the process of vapor injection or two-phase injection, there still exists limited liquid flowing to the injection pipe due to the heavy boiling disturbing. Therefore, the discharge temperature of type A flash tank system could only be cooled down quite slowly and the system may suffer from the insuperable high discharge temperature in extreme conditions. For the newly designed flash tank structure, the type c flash tank system presents a quick discharge temperature declination at high injection pressure, which is caused by pumping more liquid into injection hole as the total mass flow rate increases in the limited volume, compared with type B flash tank cycle. This also proves that the vapor injection could change into two-phase injection flexibly by properly designing the size of the novel structure.

Fig. 11.

Variation of discharge temperature Tdis with injection pressure at Tod = −10 °C.

Fig. 15.

Variation of injection mass flow ratio Rm with injection pressure at Tod = -10 °C.

As shown in Fig. 13, the system subcooling degree presents a linear decline with the injection pressure and the decline rate gradually decreases at quite a high injection pressure. This is caused by the improvement of heat exchange efficiency and latent heat in condenser due to the decrease of discharge pressure and discharge superheating degree. This means that the increase of two-phase heat exchange area will result in a reduction of the liquid refrigerant heat exchange area in the fixed condenser. Therefore, the system subcooling degree decreases with the injection pressure and is determined by the opening of EEV1. For the type C flash tank with the smallest volume, the cycle subcooling degree is relatively high due to the high discharge pressure and high injection ratio, compared with the type A and Type B flash tank cycles. As rising the compressor frequency, the system subcooling degree almost keeps the same as that at low compressor frequency for the cycles equipped with the type A and type B flash tank. To explain this variation, we consider that the flash tank is not only the component for two-phase separation but it is also playing the role of refrigerant storage (the liquid level fluctuation is shown in Fig. 16). By the comparison between the type B and type C flash tank cycle, the variation of system subcooling degree is more like to keep the conservation of mass in flash tank. When the injection mass flow rate is larger than that of the vapor produced by the EEV1 throttling process, the liquid level of the flash tank will be increased and the liquid content of the two-phase injection increases. The increase in the liquid content of the two-phase injection would cause a further increase in the discharge pressure and the subcooling degree.

Fig. 16.

Variation trend of liquid level with injection pressure and evaporator temperature.

To study the effects of the newly designed flash tank structure, the variation of total mass flow rate with injection pressure is shown in Fig. 14. Compared with the decreased tendency of the improvement of the type A flash tank cycle total mass flow rate, the total mass flow rate of the novel flash tank cycles presents a linear growth with the injection pressure. For the heavy boiling disturbing in the type A flash tank and large size, the limited liquid will be pumped to the injection hole to strengthen the cooling effect in the compressor mix chamber. While for the novel flash tank, the liquid can be forced to flow to the injection pipe with the separated vapor at the high injection pressure as the liquid level is high enough. Therefore, the newly designed flash tank is more suitable for controlling the injection mass flow rates of heat pumps, especially for improving the heating performance under extreme conditions. Due to the small size, intermittent liquid injection frequency for the type C flash tank will be higher than that of Type B flash tank. Therefore, the increase in the liquid content of injected two-phase refrigerant causes the increase in injection mass flow ratio (as shown in Fig. 15) and the decrease in the discharge vapor superheating degree.

Fig. 15 shows the variation of injection mass flow ratio Rm with injection pressure at different frequencies. The injection mass flow ratio increases slowly as the injection pressure is under 780 kPa due to the low pressure difference at the injection hole. With the further rising of injection pressure, the injection mass flow ratio presents a linear increasing tendency. For the type A flash tank, the heavy boiling makes the injection mass flow ratio unable to increase effectively. Even if the injection pressure is high enough, the injection mass flow ratio is still lower than 0.25 and presents no potential to further increase. However, it is possible for the proposed novel structure flash tank to keep the injection mass flow ratio increasing with the injection pressure steadily by two-phase injection at the high injection pressure. Meanwhile, the volume of the novel also affects the process of two-phase injection and separation. The type C flash tank cycle could drive more liquid to the injection pipe than the type B flash tank at high injection pressure, which makes the injection mass flow ratio increasing much faster. The above results also prove that the novel flash tank structure could be well designed to control the discharge vapor temperature.

Through the experimental study of the liquid refrigerant accumulation in the novel flash tank under variable working conditions, the variation trend of liquid level in flash tank with injection pressure and evaporator temperature is preliminarily obtained and is shown in Fig. 16. From Fig. 16(a), it can be seen that the liquid refrigerant accumulation in the flash tank is little at low injection pressure. With the opening of EEV1, the liquid phase refrigerant accumulation gradually increases. Therefore, the dryness at the flash tank's two-phase inlet decreases with the liquid level rising in the flash tank. Moreover, under the same injection pressure, the further expansion of the working temperature difference will also increase the liquid-phase refrigerant accumulation in the flash tank (as shown in Fig. 16(b)).

Due to the liquid level fluctuation in flash tank with the working condition, it is important to set the rated condition for designing the cycle components, as well as the flash tank. In this study, a flash tank design method is developed and experimentally verified. The design model is described as Eqs. (10), (11), (12), (13), (14), (15) by considering the separation space, settling velocity, and liquid resident time in flash tank. By comparing with the best matched novel B type flash tank size, it can be seen that the error of the calculated results from the developed model is less than 5.71% (as shown in Table 5). The calculated values are close to the actual parameters, which also proves that the proposed method is effective for estimating the flash tank size before experiments.

Table 5.

Designed errors of the proposed flash tank model.

| Parameters | Designed size in experiment | Calculated by the proposed model | Errors % |

|---|---|---|---|

| inner diameter/mm | 36.6 | 35.2 | 3.97% |

| Total height/mm | 170 | 180 | −5.56% |

| Volume/ml | 185 | 175 | 5.71% |

| Rated condition in design | Indoor temperature | DB 20 °C | WB 15 °C |

| outdoor temperature | DB 7 °C | WB 6 °C | |

| Parameters setting in design | a | 1.2 | |

| b | 0.25 | ||

| t | 9 s (0.15 min) | ||

Settling velocity to keep liquid drop at balance

| (10) |

where ρliq and ρvap represent the density of the liquid and vapor in flash tank. The constant a is large than 1.0 and will be changed with the designed conditions.

Maximum volume flow rate in flash tank

| (11) |

Minimum diameter of flash tank

| (12) |

where b is a constant and must be lower than 1.0.

Liquid level fluctuation range

| (13) |

where t is the liquid resident time in flash tank.

Total height of flash tank

| (14) |

Estimate volume of flash tank

| (15) |

To optimizing the control strategy, the variation of optimum injection pressure with compressor frequency is shown in Fig. 17. For the novel type B flash tank, the optimum injection pressure increases with the compressor frequency in the range of 770–900 kPa. To predict the optimum injection pressure, the coefficient d is added to the mean pressure equation(sqrt (P1*P6)). Compared with the test value, the error of simulated value is within ±5% (as shown in Fig. 18). To confirm the correction, it is suggested that more research should be conducted to verify this function since the 5% error would cause about a 2% decrease in COPh. The optimum injection pressure can be calculated from Eq. (16).

| (16) |

Fig. 17.

The variation of the optimum injection pressure.

Fig. 18.

The coefficient d at different conditions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a comparative analysis of the FTVIC heating performance with different flash tanks is performed from the variations of heating capacity, COPh, subcooling degree, discharge pressure, discharge temperature, injection mass flow ratio, and so on. In addition, a novel flash tank with a spiral flow channel is proposed to control the two-phase separation and two-phase injection. The experiment setup is tested and verified by changing the injection pressure under the ambient temperature of −10 °C. The following conclusions can be drawn from the study:

-

●

The injection mass flow ratio could keep a nearly linear relationship with the injection pressure, which provides a potential way to maintain the discharge temperature of novel flash tank cycle below 100 °C by pumping more liquid refrigerant to the injection pipe.

-

●

Considering the maximum COPh, there exists an optimum injection pressure for the studied applications, which varies in the range of 770–900 kPa. As the injection pressure is higher than the optimum value, the cycle heating capacity could be kept at the maximum value. Therefore, the novel flash tank cycle could sacrifice efficiency to control the discharge temperature, avoiding shutting off the heat pump caused by the protection of high discharge temperature.

-

●

When the FTVIC works at the optimum injection pressure, the type B flash tank could improve the system COPh by 6.4% at f = 60 Hz and 1.8% at f = 90 Hz, compared with the type A flash tank cycle. Considering the effect of the novel flash tank size, the COPh of the type B flash tank is increased by 5.73% at compressor frequency of 60 Hz and 13.5% at compressor frequency of 90 Hz, relative to that of the type C flash tank cycle.

-

●

The size of the novel flash tank and the length of spiral tube should be designed to adapt to the nominal operating condition without injecting more liquid refrigerant into the compressor from the vapor outlet of the flash tank. A design method for the novel flash tank is proposed and verified by the best matched novel B-type flash tank size. We consider that the flash tank is not only the component for two-phase separation but it is also playing the role of refrigerant storage. By deep analysis of the liquid level fluctuation and the two-phase injection, it is suggested the design volume of flash tank should be increased with the deviation from the rated operating condition. Moreover, we put forward that enlarging the length of spiral tube may decrease the start injection pressure of two-phase injection.

Although the FTVIC with a novel flash tank is a solution to achieve high COPh or high heating capacity, it is still difficult to accurately design the flash tank's geometry based on the results obtained in the present study, especially for the spiral tube design. It is necessary to further explore the influence of the flash tank size and the geometric parameters of spiral tube on the system performance.

Author contribution statement

Jinfei Sun: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Jianxiang Guo: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Longbin He: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Shengjun Hou, Zhengchang Yu: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors contributed to the paper's conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Jinfei Sun, Jianxiang Guo, Longbin He, Shengjun Hou, and Zhengchang Yu. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jinfei Sun, and all authors commented on the revised version of the manuscript.

No conflict of interest exists in the submission of this revised manuscript, and all authors approve the final manuscript for publication. I would like to declare on behalf of my co-authors that the work described was original research that has not been published previously and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. All the authors listed have approved the revised manuscript that is enclosed.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China(Grant No. ZR2020ME169) and The Open Project of Qingdao University of Technology (Grant No. C2019-125). This paper is revised in the time of abroad visiting and sponsored by the China Scholarship Council.

Contributor Information

Jinfei Sun, Email: Jinfei0632@163.com.

Jianxiang Guo, Email: jianxiangguo@163.com.

Longbin He, Email: helongbin1998@163.com.

Shengjun Hou, Email: superhou10@163.com.

Zhengchang Yu, Email: yzc17852020959@163.com.

Nomenclature

- COP

coefficient of performance

- CSVC

conventional single-stage vapor compression

- EEV

electronic expansion valve

- f

compressor frequency

- FTVIC

flash tank vapor injection cycle

- h

specific enthalpy(J.kg−1)

mass flow rate(kg.s−1)

- P

pressure(kPa)

- Dft

Diameter of flash tank (m)

- Hfr

Liquid level fluctuation range

- Hto

Total flash tank height

- VFvapmax

Maximum volume flow rate(m³/h)

- Q

capacity(W)

- Rm

injection mass flow ratio

- Rp

injection pressure ratio

- VI

vapor injection

- SCVIC

sub-cooler vapor injection cycle

- EES

Engineering Equation Solver

- W

power consumption(W)

- ASHP

air-source heat pump

- T

temperature(K)

- C

discharge coefficient

- Aa

nozzle area (m2)

- pv

differential static pressure through nozzle (Pa)

- pn

static pressure before nozzle (Pa)

- U

uncertainty of the variable

- Vn

specific volume of air at the dry and wet bulb temperature at the nozzle inlet and at standard atmosphere (m³/kg)

- dn

moisture content at the nozzle (kg/kg)

- Wfan

power consumption of fans (W)

- Wec

power consumption of controllers (W)

- ηi

isentropic efficiency

- ηm

mechanical efficiency

Air flow rate (per kg dry air.s-1)

- σ

uncertainty (%)

- t

Resident time (min)

- Vft

Designed volume of flash tank (m³)

- vt

Settling velocity(m/s)

- ρ

Density (kg/m³)

Subscripts

- air

air side

- DB

dry bulb temperature

- dis

discharge

- h

Heating

- inj

injection

- in

air inlet

- m

mass

- od

out door

- out

air outlet

- s

suction

- to

total

- WB

wet bulb temperature

- eva

evaporator

References

- 1.Huang F., Zheng J., Baleynaud J.M., Lu J. Heat recovery potentials and technologies in industrial zones. J. Energy Inst. 2017;90:951–961. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sánta R. Investigations of the performance of a heat pump with internal heat exchanger. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022;147:8499–8508. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang L. Energy and exergy performance comparison of different HFC/R1234yf mixtures in vapor-compression cycles. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020;140:2447–2459. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohanraj M., Abraham J.D.A.P. Environment friendly refrigerant options for automobile air conditioners: a review. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022;147:47–72. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu X., Hwang Y., Radermacher R. Refrigerant injection for heat pumping/air conditioning systems: literature review and challenges discussions. Int. J. Refrig. 2011;34:402–415. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emmi G., Zarrella A., Carli M. A heat pump coupled with photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collectors: a case study of a multi-source energy system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017;151:386–399. [Google Scholar]

- 7.James A., Mohanraj M., Srinivas M., Jayaraj S. Thermal analysis of heat pump systems using photovoltaic-thermal collectors: a review. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021;144:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang S., Wang S., Yu Y., Ma Z., Wang J. Further analysis of the influence of interstage configurations on two-stage vapor compression heat pump systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021;184 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song-Bo L.I., Liu X.Y., Fan S.H. The associated research of inverter compressor frequency and heat pump air condition parameters. Build. Energy Environ. 2014;33:36–38. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X., Hwang Y., Radermacher R. Two-stage heat pump system with vapor-injected scroll compressor using R410A as a refrigerant. Int. J. Refrig. 2009;32:1442–1451. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umezu K., Suma S. Heat pump room air-conditioner using variable capacity compressor. Build. Eng. 1984;90:335–349. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu X., Hwang Y., Radermacher R. Performance comparison of R410A and R32 in vapor injection cycles. Int. J. Refrig. 2013;36:892–903. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H., Hwang Y., Radermacher R., Chun H.H. Performance investigation of multi-stage saturation cycle with natural working fluids and low GWP working fluids. Int. J. Refrig. 2015;51:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tello-Oquendo F.M., Navarro-Peris E., Gonzálvez-Maciá J. Comparison of the performance of a vapor-injection scroll compressor and a two-stage scroll compressor working with high pressure ratios. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019;160 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung J., Jeon Y., Cho W., Kim Y. Effects of injection-port angle and internal heat exchanger length in vapor injection heat pumps for electric vehicles. Energy. 2020;193 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu H., Lin K., Huang H., Xiong B., Zhang B., Xing Z. Research on effects of vapor injection on twin-screw compressor performance. Int. J. Refrig. 2020;118:483–490. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H., Hwang Y., Radermacher R., Chun H.H. Potential benefits of saturation cycle with two-phase refrigerant injection. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013;56:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun J., Zhu D., Yin Y., Li X. Experimental investigation of the heating performance of refrigerant injection heat pump with a single-cylinder inverter-driven rotary compressor. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018;133:1579–1588. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei W., Ni L., Xu L.b., Yang Y., Yao Y. Application characteristics of variable refrigerant flow heat pump system with vapor injection in severe cold region. Energy Build. 2022;211 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joppolo C.M., Molinaroli L., Vecchi G., Bianchi C., Magni F., Winandy E. Performance assessment of an air-to-water R-407C heat pump with vapour injection scroll compressor. Build. Eng. 2010;116:310–317. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baek C., Lee E., Kang H., Kim Y. Proceedings of International Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning Conference at Purdue. 2008. Experimental study on the heating performance of a CO2 heat pump with gas injection. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baek C., Heo J., Jung J., Cho H., Kim Y. Performance characteristics of a two-stage CO2 heat pump water heater adopting a sub-cooler vapor injection cycle at various operating conditions. Energy. 2014;77:570–578. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heo J., Jeong M.W., Kim Y. Effects of flash tank vapor injection on the heating performance of an inverter-driven heat pump for cold regions. Int. J. Refrig. 2010;33:848–855. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heo J., Kang H., Kim Y. Optimum cycle control of a two-stage injection heat pump with a double expansion sub-cooler. Int. J. Refrig. 2012;35:58–67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma G.Y., Zhao H.X. Experimental study of a heat pump system with flash-tank coupled with scroll compressor. Energy Build. 2008;40:697–701. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heo J., Jeong M.W., Baek C., Kim Y. Comparison of the heating performance of air-source heat pumps using various types of refrigerant injection. Int. J. Refrig. 2011;34:444–453. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng C., Kai W., Wang S., Xing Z., Shu P. Investigation of the heat pump water heater using economizer vapor injection system and mixture of R22/R600a. Int. J. Refrig. 2009;32:509–514. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu X., Hwang Y., Radermacher R., Pham H.M. The International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference. Purdue; 2012. Performance measurement of R32 in vapor injection heat pump system. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Róbert S., Garbai L., Fürstner I. Numerical investigation of the heat pump system. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017;130:1133–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anand S., Tyagi S.K. Exergy analysis and experimental study of a vapor compression refrigeration cycle. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012;110:961–971. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi J.W., Lee G., Kim M.S. Numerical study on the steady state and transient performance of a multi-type heat pump system. Int. J. Refrig. 2011;34:429–443. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiao H., Aute V., Radermacher R. Transient modeling of a flash tank vapor injection heat pump system - Part I: model development. Int. J. Refrig. 2015;49:169–182. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiao H., Xu X., Aute V., Radermacher R. Transient modeling of a flash tank vapor injection heat pump system – Part II: simulation results and experimental validation. Int. J. Refrig. 2015;49:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redón A., Navarro-Peris E., Pitarch M., Gonzálvez-Macia J., Corberán J.M. Analysis and optimization of subcritical two-stage vapor injection heat pump systems. Appl. Energy. 2014;124:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tello-Oquendo F.M., Navarro-Peris E., Barceló-Ruescas F., Gonzálvez-Maciá J. Semi-empirical model of scroll compressors and its extension to describe vapor-injection compressors. Model description and experimental validation. Int. J. Refrig. 2019;106:308–326. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu X., Hwang Y., Radermacher R. Transient and steady-state experimental investigation of flash tank vapor injection heat pump cycle control strategy. Int. J. Refrig. 2011;34:1922–1933. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang B., Shi W., Han L., Li X. Optimization of refrigeration system with gas-injected scroll compressor. Int. J. Refrig. 2009;32:1544–1554. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minh N.Q., Hewitt N.J., Eames P.C. International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference. Purdue; 2006. Improved vapour compression refrigeration cycles: literature review and their application to heat pumps. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan G., Jia Q., Bai T. Experimental investigation on vapor injection heat pump with a newly designed twin rotary variable speed compressor for cold regions. Int. J. Refrig. 2016;62:232–241. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.