Key Points

Question

What were the initial implementation challenges and solutions for a Medicaid accountable care organization participating in the Massachusetts Flexible Services program to address food and housing insecurity?

Findings

In this mixed-methods qualitative evaluation, implementation challenges included administrative burden, COVID-19 factors that influenced screening for social needs, data tracking and sharing, and coordinating with community organizations. Adaptive solutions included administrative funding for hiring enrollment staff, bidirectional communication with community partners, new strategies to identify eligible patients, and raising clinician awareness of the Massachusetts Flexible Services program.

Meaning

Future state and health systems’ programs to address health-related social needs may benefit from minimizing administrative burden, providing funding for enrollment staff and evaluation, and developing effective information-sharing platforms.

Abstract

Importance

Health systems are increasingly addressing health-related social needs. The Massachusetts Flexible Services program (Flex) is a 3-year pilot program to address food insecurity and housing insecurity by connecting Medicaid accountable care organization (ACO) enrollees to community resources.

Objective

To understand barriers and facilitators of Flex implementation in 1 Medicaid ACO during the first 17 months of the program.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This mixed-methods qualitative evaluation study from March 2020 to July 2021 used the Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance/Practical, Robust Implementation, and Sustainability Model (RE-AIM/PRISM) framework. Two Mass General Brigham (MGB) hospitals and affiliated community health centers were included in the analysis. Quantitative data included all MGB Medicaid ACO enrollees. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 15 members of ACO staff and 17 Flex enrollees.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Reach was assessed by the proportion of ACO enrollees who completed annual social needs screening (eg, food insecurity and housing insecurity) and the proportion and demographics of Flex enrollees. Qualitative interviews examined other RE-AIM/PRISM constructs (eg, implementation challenges, facilitators, and perceived effectiveness).

Results

Of 67 098 Medicaid ACO enrollees from March 2020 to July 2021 (mean [SD] age, 28.8 [18.7] years), 38 442 (57.3%) completed at least 1 social needs screening; 10 730 (16.0%) screened positive for food insecurity, and 7401 (11.0%) screened positive for housing insecurity. There were 658 (1.6%) adults (mean [SD] age, 46.6 [11.8] years) and 173 (0.7%) children (<21 years; mean [SD] age, 10.1 [5.5]) enrolled in Flex; of these 831 people, 613 (73.8%) were female, 444 (53.4%) were Hispanic/Latinx, and 172 (20.7%) were Black. Most Flex enrollees (584 [88.8%] adults; 143 [82.7%] children) received the intended nutrition or housing services. Implementation challenges identified by staff interviewed included administrative burden, coordination with community organizations, data-sharing and information-sharing, and COVID-19 factors (eg, reduced clinical visits). Implementation facilitators included administrative funding for enrollment staff, bidirectional communication with community partners, adaptive strategies to identify eligible patients, and raising clinician awareness of Flex. In Flex enrollee interviews, those receiving nutrition services reported increased healthy eating and food security; they also reported higher program satisfaction than Flex enrollees receiving housing services. Enrollees who received nutrition services that allowed for selecting food based on preferences reported higher satisfaction than those not able to select food.

Conclusions and Relevance

This mixed-methods qualitative evaluation study found that to improve implementation, Medicaid and health system programs that address social needs may benefit from providing funding for administrative costs, developing bidirectional data-sharing platforms, and tailoring support to patient preferences.

This qualitative study sought to understand the barriers and facilitators of Massachusetts Medicaid’s Flexible Services Program implementation in a Medicaid accountable care organization during the first 17 months from March 2020 to July 2021.

Introduction

Health-related social needs (HRSNs) are associated with high health care utilization and costs1,2 and poor health outcomes.2,3,4,5,6 States and health care systems are increasingly recognizing the importance of addressing unmet HRSNs and implementing interventions to address these needs.7,8 Evaluating the effectiveness of HRSN interventions has been limited by a lack of implementation data, including details on program delivery designs and adaptations made to tailor programs to the needs of defined populations.9,10,11

A focus on value-based care and the proliferation of alternative payment models has further fueled the implementation of systematic interventions to address HRSNs.12,13 As of July 2021, 12 state Medicaid programs were using accountable care organizations (ACOs).14 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) encourages these ACOs to address HRSNs systematically through universal screening and referral, and partnerships with community-based organizations that specialize in social resource provision.15,16 Some states, including Massachusetts,17,18 have received Medicaid Section 1115 waivers to support health system linkages with community-based social services organizations to provide resources to members with identified HRSN.19 While CMS requires states to conduct and report evaluations of their waiver programs, these typically do not include evaluation of program implementation, which is critical for understanding why programs might succeed or fail and for informing future policy decisions and implementation efforts.10,20,21,22

In January 2020, Massachusetts Medicaid (MassHealth) launched a 3-year pilot of the Flexible Services program (Flex).23 The program provided $149 million statewide to ACOs to partner with social services organizations to provide nutrition and housing-related services to enrollees with food or housing insecurity and substantial health needs. Flex was not designed as an entitlement benefit or covered service for all eligible ACO enrollees; instead, it was meant to supplement existing benefit programs by providing a limited amount of additional funding to each ACO. While other ACO programs and funding supported screening and referral for social needs, the Flex program’s unique contribution was direct payment for social needs services (eg, food boxes or meals to support individuals with food insecurity). The objective of this qualitative study was to use mixed methods to conduct an implementation evaluation of the first 1.5 years of Flex (March 2020 to July 2021) in a single MassHealth ACO, guided by the Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance/Practical, Robust Implementation, and Sustainability Model (RE-AIM/PRISM).24

Methods

This mixed-methods qualitative evaluation study was conducted in 2 large hospitals and 5 community health centers in the Mass General Brigham (MGB) Medicaid ACO in Boston, MA from March 2020 to July 2021. The mixed-methods approach used quantitative health system data to assess HRSN screening and Flex enrollment and qualitative interviews with health system staff and Flex enrollees to understand implementation challenges and successes. This evaluation was conducted as part of a longitudinal quasi-experimental study (LiveWell/ViveBien) designed to assess the association of Flex with the health and health care utilization of MGB community health center patients. The research team was not involved in the design or implementation of Flex. Study procedures were approved by the MGB institutional review board on August 27, 2019. All participants provided verbal informed consent for participation and the use of the content of their interviews (eg, quotations) in research reports and publications. This study adheres to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)25 reporting guideline.

Flexible Services Program

Two categories of services are funded through Flex: nutrition support (food vouchers, food boxes, medically tailored meals) and housing support (assistance with affordable housing applications, utility bills). The ACOs were encouraged, but not required, to partner with local social service organizations (SSOs) and establish financial contracts to compensate SSOs for service delivery.26 MassHealth provided examples for structuring payment contracts with SSOs (eg, fee for service, prospective lump sum, bundle) but did not provide templates, requirements, or formal support for these contracts. While some ACOs provided Flex services internally (eg, hospital-based food pantries), the majority of services were delivered by SSOs.26 Flex enrollment was designed to occur at the individual level, but more than 1 individual in a household could be enrolled. Eligibility criteria were: (1) enrollment in a MassHealth ACO, (2) food or housing insecurity identified by screening or clinical encounter, and (3) complex physical or behavioral health need (eg, obesity, uncontrolled diabetes, uncontrolled depression), high emergency department use (ie, at least 2 visits in 6 months or at least 4 visits in 1 year), or high-risk pregnancy. During the period of this evaluation, MGB planned for approximately 1900 enrollments into Flex SSOs that served the hospitals and community health centers in this study. A detailed description of Flex is included in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

In anticipation of the 2020 start of Flex, Medicaid ACOs were required to begin annual HRSN screening in 2018. The MGB system began systematic screening in March 2018 using electronic tablet–delivered surveys in primary care practices. Screening was prompted in the electronic health record (EHR) for all ACO members at the time of a clinical visit every 12 months. Screeners were either self-administered by patients or administered by health center staff. Screening data were recorded in a specific, structured EHR module. Food insecurity was assessed with the validated 2-item US Department of Agriculture (USDA) screener.27 Housing insecurity was assessed using 3 items developed from prior literature.28,29

Implementation Measures

The RE-AIM/PRISM framework was used to evaluate Flex implementation from the perspective of the Medicaid ACO.24 Table 1 summarizes the application of the framework in the current study, including definitions, data sources, and measures for RE-AIM/PRISM constructs. Quantitative data was used to measure reach and qualitative data to assess implementation, adoption, perceptions of effectiveness, and the PRISM constructs of internal and external context.

Table 1. Application of RE-AIM/PRISM for a Mixed-Methods Implementation Evaluation of the MassHealth Flexible Services Program in the Mass General Brigham Accountable Care Organization.

| RE-AIM/PRISM outcomes | Glasgow et al,24 2019 definition | Data source | Study Measure (March 2020-July 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | The “number, proportion, and representativeness of individuals” who participated in the program. | EHR |

|

| Effectiveness | “The impact of [the program] on important outcomes.” | Patient interviews, staff interviews |

|

| Adoption | “Reasons for adoption or non-adoption” of program components. | Staff interviews |

|

| Implementation | “Fidelity to the various elements of [the program's] protocol, including consistency of delivery as intended” and “adaptations made.” | Patient interviews, staff interviews, EHR |

|

| Maintenance | “The extent to which…a program or policy becomes institutionalized.” | Staff interviews, EHR |

|

| Internal context | Internal environment (eg, organizational structure, characteristics, capacity; patient characteristics) | Patient interviews, hospital staff interviews |

|

| External context | External environment (eg, policies, guidelines, external events) | MGB staff interviews |

|

Abbreviations: ACO, accountable care organization; EHR, electronic health record; MassHealth, Massachusetts Medicaid; MGB, Mass General Brigham; RE-AIM/PRISM, Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance/Practical, Robust Implementation, and Sustainability Model.

Patients were aligned to 2 large hospitals in the MGB Medicaid ACO and their affiliated community health centers.

Reach of Flex was assessed using 3 metrics. First, completion of the annual health system-based screener for food and housing insecurity (numerator) using EHR data was examined among adult and pediatric Medicaid ACO patients (denominator) from March 2020 to July 2021. The second reach metric was the number and proportion of Medicaid ACO patients enrolled in Flex during this time and the demographic characteristics (age, sex, and self-reported race and ethnicity) of Flex enrollees compared with the overall ACO population. The third metric was the health conditions of Flex enrollees documented by staff in an EHR Flex enrollment form as eligibility criteria.

Implementation, adoption, perceptions of effectiveness, and internal and external contextual factors based on RE-AIM/PRISM were assessed using qualitative interviews with key implementation personnel in the health system and adult Flex enrollees. Given the early stage of the Flex pilot, maintenance was not assessed. Staff was invited to participate in interviews using purposive sampling based on their Flex responsibilities; this included ACO staff involved in the design and roll-out of Flex (eg, individuals employed centrally by the ACO), as well as hospital and community health center staff who implemented Flex (eg, Flex program managers and enrollment staff). Staff was invited for interviews by a PhD-level investigator (J.L.M.), who explained her role as a researcher and had no formal working relationship with interviewees. A semistructured qualitative interview guide elicited the staff’s role in Flex and descriptions of implementation barriers and facilitators, including internal and external contextual factors (eFigure in Supplement 1). Staff did not receive remuneration. To protect participants, job roles were described using broad definitions (ie, ACO staff, hospital staff), and interview results that could potentially identify individuals, including specific quotations, were excluded.

Flex enrollees who participated in qualitative interviews were LiveWell/ViveBien study participants who enrolled in Flex before July 2021. Participants were invited using purposive sampling based on sex, language (English, Spanish), health center affiliation, and receipt of food resources vs housing resources. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish. The semistructured interview guide for Flex enrollees targeted aspects of program implementation (eg, barriers, facilitators, satisfaction) and perceived effectiveness (eg, changes in food or housing insecurity or health behaviors) (eFigure in the Supplement). Enrollees received $25 for participation.

Quantitative Data and Statistical Analyses

Screening for food and housing insecurity was recorded in the EHR. Any screening completed between March 2018 and July 2021 was included. To determine Flex enrollment outcomes (eg, whether a patient received services, declined, or was unreachable), a combination of data sources was used, including the following: (1) formal enrollment forms in the EHR, (2) enrollment and service provision data entered in an electronic data sharing platform that the ACO adapted for bidirectional ACO-SSO communication, and (3) quarterly enrollment reports maintained by ACO project management staff, which included information from SSO-specific Flex tracking and reporting documents. Demographic characteristics (age, sex, and self-reported race and ethnicity) for ACO and Flex enrollees were obtained from the EHR and summarized using Stata statistical software, version 16.0 (StataCorp).

Qualitative Interviews and Thematic Analysis

All qualitative interviews were conducted via phone or video platform, audio-recorded, and transcribed. Qualitative data were coded and analyzed using Dedoose software, version 9.0.54 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC), and the framework method thematic analysis approach.30 The research team identified themes based on content in the interview guides (eFigure in Supplement 1). Two trained bilingual research assistants independently coded all transcripts. Discrepancies were resolved as needed with input from a PhD-level researcher (J.L.M.). Saturation was determined when novel themes no longer emerged. Themes and results were reviewed with the research team and select interviewees to ensure accuracy and face validity.

Results

Annual Screening for Food and Housing Insecurity

Of the 67 098 Medicaid ACO patients in the sample from March 2020 to July 2021, 38 442 (57.3%) completed at least 1 screening for food insecurity and housing insecurity between 2018 and 2021; 10 730 (16.0% of all ACO enrollees) screened positive for food insecurity; and 7401 (11.0% of all ACO enrollees) screened positive for housing insecurity at least once (Table 2). These rates were similar for adults and children. The rates of screening and food and housing insecurity were higher among Flex enrollees: 573 (87.1%) adults and 158 (91.3%) children completed at least 1 screener; 61.6% of adults and 49.1% of children screened positive for food insecurity, and 35.6% of adults and 26.0% of children screened positive for housing insecurity.

Table 2. Completion of Annual Screening for Food and Housing Insecurity by Adult and Pediatric Medicaid Accountable Care Organization Enrollees.

| Characteristic | Medicaid ACO enrolleesa (March 2018-July 2021) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Adults (≥21 y) | Adults enrolled in Flexb | Children (<21 y) | Children enrolled in Flexb | |

| No. | 67 098 | 40 616 | 658 | 26 482 | 173 |

| At least 1 SDOH screener complete, No. (%)c | 38 442 (57.3) | 21 575 (53.1) | 573 (87.1) | 16 867 (63.7) | 158 (91.3) |

| Ever screened positive for food or housing insecurity, No. (%) | 14 059 (21.0) | 8674 (21.4) | 449 (68.2) | 5385 (20.3) | 95 (54.9) |

| Ever screened positive for food insecurity, No. (%) | 10 730 (16.0) | 6762 (16.6) | 405 (61.6) | 3968 (15.0) | 85 (49.1) |

| Ever screened positive for housing insecurity, No. (%) | 7401 (11.0) | 4734 (11.7) | 234 (35.6) | 2667 (10.1) | 45 (26.0) |

Abbreviations: ACO, accountable care organization; Flex, Flexible Services program; SDOH, social determinants of health.

Medicaid ACO enrollees were patients enrolled in the Mass General Brigham (MGB) ACO who were aligned to 2 of the largest hospitals in the health system and their affiliated community health centers.

Eligibility criteria for Flex included (1) enrollment in MGB Medicaid ACO; (2) food or housing insecurity identified by screening or clinical encounter; and (3) a complex health condition (eg, uncontrolled diabetes, depression).

Screening was completed during primary care health visits or through contact with patients’ primary care clinicians from March 2018 (beginning of annual social needs screening for Medicaid ACO patients) through July 2021 (end of the current analysis). These results reflect screening that was documented in a designated social needs screening module of the electronic health record (EHR). Assessment of social needs may have also occurred via informal conversations between patients and clinicians or other health center staff and documented in the EHR in nonsystematic ways; those assessments are not reflected here.

Enrollment and Receipt of Flexible Services

A total of 658 (1.6%) adult patients (mean [SD] age, 46.6 [11.8] years) and 173 (0.7%) pediatric patients (<21 years; mean [SD] age, 10.1 [5.5]) were enrolled in Flex between March 2020 and July 2021 (Table 3). Of these 831 people, 613 (73.8%) were female participants, 444 (53.4%) were Hispanic/Latinx participants, and 172 (20.7%) were Black participants. Obesity was the condition most frequently documented by staff to fulfill Flex enrollment criteria (428 [65.1%] adults, 103 [59.5%] children) followed by uncontrolled depression (142 [21.6%] adults) and developmental disorders (31 [17.9%] children) (eTable in Supplement 1).

Table 3. Demographic Characteristics of Medicaid Accountable Care Organization Enrollees and Flexible Services Program Enrollees.

| Characteristic | Medicaid ACO enrolleesa (March 2020-July 2021) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Adults (≥21 y) | Adults enrolled in Flexb | Children (<21 y) | Children enrolled in Flexb | |

| No. | 67 098 | 40 616 | 658 | 26 482 | 173 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 28.8 (18.7) | 41.2 (13.0) | 46.6 (11.8) | 9.9 (5.9) | 10.1 (5.5) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Female | 38 809 (57.8) | 25 696 (63.3) | 539 (81.9) | 13 113 (49.5) | 74 (42.8) |

| Male | 28 289 (42.2) | 14 920 (36.7) | 119 (18.1) | 13 369 (50.5) | 99 (57.2) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 24 461 (36.5) | 12 503 (30.8) | 360 (54.7) | 11 958 (45.2) | 84 (48.6) |

| Non-Hispanic | 34 021 (50.7) | 24 334 (59.9) | 284 (43.2) | 9687 (36.6) | 69 (39.9) |

| Unknown | 8616 (12.8) | 3779 (9.3) | 14 (2.1) | 4837 (18.3) | 20 (11.6) |

| Racec | |||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 148 (0.2) | 107 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 41 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 2925 (4.4) | 1983 (4.8) | 6 (0.9) | 942 (3.6) | 4 (2.3) |

| Black | 10 608 (15.8) | 7424 (18.3) | 143 (21.7) | 3180 (12.0) | 29 (16.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 57 (0.1) | 39 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 18 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| White | 25 077 (37.4) | 17 983 (44.3) | 169 (25.7) | 7094 (26.8) | 44 (25.4) |

| Otherd | 17 247 (25.7) | 8444 (20.8) | 210 (31.9) | 8803 (33.2) | 70 (40.5) |

| Multiracial | 1564 (2.3) | 803 (2) | 8 (1.2) | 761 (2.87) | 6 (3.5) |

| Unknown | 9476 (14.1) | 3833 (9.4) | 120 (18.2) | 5643 (21.3) | 20 (11.6) |

Abbreviations: ACO, accountable care organization; Flex, Flexible Services program.

Patients enrolled in the Mass General Brigham (MGB) ACO who were aligned to 2 of the largest hospitals in the health system and their affiliated community health centers.

Eligibility criteria for Flex enrollment included (1) enrollment in MGB Medicaid ACO; (2) food or housing insecurity identified by screening or clinical encounter; and (3) a complex health condition (eg, uncontrolled diabetes, depression).

Race was self-reported in the electronic health record data. All categories from the electronic health record are included in the table.

Enrollees self-identified as “other” race; 82% of enrollees in this category reported Hispanic ethnicity.

Of 658 adults enrolled in Flex, 584 (88.8%) received services, 14 (2.1%) declined services after enrollment, and 60 (9.1%) were unreachable or had no documented service outcome. Of those who received services, 505 (76.7%) received nutrition support, 87 (13.2%) received housing support, and 21 (3.2%) received both. Of 173 pediatric Flex enrollees, 143 (82.7%) received services, 6 (3.5%) declined services after enrollment, and 24 (13.9%) were unreachable or had no documented service outcome. Of those who received services, 114 (65.9%) received nutrition support, 35 (20.2%) received housing support, and 6 (3.5%) received both.

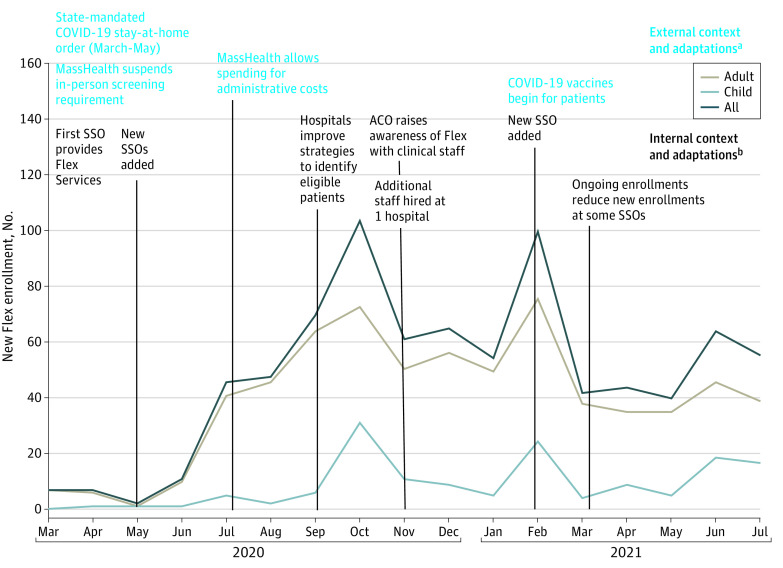

The Figure displays the number of new Flex enrollees each month between March 2020 and July 2021. Events that occurred within the health system (eg, staffing changes in the ACO) and external to the health system (eg, COVID-19 pandemic, MassHealth policies) are superimposed on the Figure to demonstrate how they may have influenced enrollment. Flex roll-out in March 2020 coincided with the state-mandated COVID-19 lockdown; this external contextual factor contributed to lower enrollment from March 2020 to May 2020. External program adaptations included MassHealth’s enactment of 2 policy modifications. First, in early 2020, MassHealth removed the in-person screening requirement to enroll patients into Flex. Second, in June 2020, MassHealth allowed ACOs to use Flex funding for administrative costs, such as salaries for enrollment staff. Internal program adaptations that coincided with increased enrollment included: execution of additional SSO contracts, development of hospital-specific strategies to identify eligible patients and improve administrative workflow, an ACO-led campaign to increase clinicians’ awareness of Flex and assist with local problem-solving for screening and enrollment, and hiring additional enrollment staff (Figure).

Figure. Monthly Flexible Services Program Enrollments of Medicaid Accountable Care Organization (ACO) Patients Aligned to 2 Large Hospitals.

This mixed-methods qualitative study occurred in a Massachusetts ACO from March 2020 to July 2021 during the first 17 months of program implementation. The labels on this line graph show the factors that may have influenced the pace of enrollments. Abbreviations: Flex, Flexible Services program; MassHealth, Massachusetts Medicaid; SSO, social service organization.

aExternal environmental factors (eg, policies, guidelines, external events) and implementation adaptations that influenced new enrollments into Flex.

bInternal environmental factors (eg, organizational structure, characteristics, capacity) and implementation adaptations that influenced new enrollments into Flex.

Implementation Barriers, Facilitators, and Adaptive Solutions

Table 4 presents Flex implementation challenges and adaptive solutions as reported by health system staff (n = 15) and Flex enrollees (n = 17). Staff reported challenges in the administration of Flex that included complex eligibility requirements, time-intensive enrollment paperwork, and burden associated with identifying appropriate patients (eg, screening, EHR review) and providing follow-up support (eg, communicating with SSOs, tracking outcomes). In addition to screening positive for food or housing insecurity, ACO enrollees had to meet health criteria to be eligible for Flex; these criteria included both having certain health diagnoses and needing improvement or control within that condition (eg, having uncontrolled type 2 diabetes vs simply having type 2 diabetes). The complexity of verifying these eligibility criteria created a substantial burden for enrollment staff. The 2 hospital entities differed in their abilities to accommodate the Flex administrative burden, highlighting the importance of preexisting staff availability as an internal contextual factor. One hospital entity redeployed existing social work and case management staff for Flex enrollment early in 2020, but the other lacked staffing flexibility and benefited from the MassHealth policy change allowing Flex funding to cover administrative costs. The ACO staff described developing new methods for automating and systematizing Flex-related workflows as the program was rolled out. Staff reported that adaptations to reduce the administrative burden took approximately 1 year.

Table 4. Staff-Reported and Patient-Reported Barriers, Facilitators, and Adaptive Solutions in the First 17 Monthsa of Implementation of the Flexible Services Program in the Mass General Brigham Accountable Care Organization.

| Implementation components | Barriers and challenges | Facilitators and adaptive solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Flex administration |

|

|

| Flex enrollment procedures |

|

|

| Health system partnerships with SSOs |

|

|

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|

|

| Patient experiences with nutrition services |

|

|

| Patient experiences with housing services |

|

|

Abbreviations: ACO, accountable care organization; BMI, body mass index; Flex, Flexible Services program; GI, gastrointestinal; MassHealth, Massachusetts Medicaid; SSO, social service organization.

The first 17 months included March 2020 to July 2021.

ACO staff included staff employed centrally by the ACO (eg, Flex managers).

Hospital staff included staff employed at individual hospitals and community health centers (eg, hospital-specific Flex managers and enrollment staff).

Partnering and information-sharing with SSOs were additional complex challenges. Staff described challenges with SSOs’ financial contracts and payment models, cross-sector differences in communication style and expectations for services, and problems accessing follow-up information for referred patients. While hospitals were responsible for establishing payment contracts with SSOs, ACO staff reported difficulty estimating the volume of referrals that an SSO would receive and noted that some SSOs struggled to provide services due to pandemic-related staffing and supply challenges. Further, staff described that SSO payment contracts often involved fee-for-service invoicing which hospitals completed weeks or months after service delivery, contributing to operational and budgetary strain for SSOs.

Staff emphasized the need for improved bidirectional information sharing to communicate with SSOs and track outcomes. While a pre-existing resource platform was adapted in the first year to serve as an ACO-SSO communication and tracking platform, use of this platform added to the documentation burden for both staff and SSOs. Flex services provided internally (eg, hospital-based food pantry) were not documented in the platform. Staff described other limitations of the platform, such as overwritten historical data and cumbersome user experience. The limitations and documentation burden of the data-sharing platform were additional internal contextual factors that contributed to information-sharing challenges.

Staff noted that the COVID-19 pandemic was an external contextual factor that contributed to slow initial Flex enrollment in part because HRSN screening required in-person office visits, which declined significantly in March 2020. State and local program adaptations were critical to respond to this challenge; MassHealth discontinued the in-person screening requirement, and hospitals pushed questionnaires to patients through the EHR while also initiating new systems to identify eligible patients (eg, reports based on health eligibility criteria).

Interviews of Flex enrollees highlighted barriers to program effectiveness as well as early signals of positive health outcomes. In general, Flex enrollees reported that Flex enrollment and connecting with SSOs was feasible. Enrollees reported barriers to using nutrition services that included poor access (eg, lack of transportation), poor fit with dietary preferences, and suboptimal quality of food (eg, produce near expiration). Conversely, enrollees reported that nutrition supports improved or resolved their food insecurity, helped them make healthy dietary changes, and improved their motivation or capacity for self-management of health conditions. Enrollees who were older or had more complex health conditions expressed satisfaction with medically tailored meals or preset food boxes, whereas younger patients and patients with dependent children preferred to choose their own food. Flex enrollees with dependent children often reported that the nutrition support improved their children’s dietary intake and health as well as their own.

Enrollees receiving housing support reported overall lower satisfaction. Housing support received by interview participants included assistance with affordable housing applications and short-term assistance with utility bills. Enrollees described that, while helpful, these supports did not resolve their housing insecurity, and they had little or no change in their health or health behaviors as a result of housing support received.

Discussion

This mixed-methods qualitative evaluation study evaluated the MassHealth Flexible Services program in 1 Medicaid ACO and identified factors that influenced its reach, adoption, implementation, and perceived effectiveness. While external contextual factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic, slowed the initial reach and implementation, program modifications during the first year improved the reach and implementation of Flex. This study characterized the who, what, and why of Flex modifications enacted by MassHealth and the ACO, which are critical implementation data that may inform future HRSN programs.31

Flex’s reach within the first 17 months was modest, largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic and initial administrative barriers. The number of Flex enrollments was slightly less than half of the ACO’s projection for the study period. However, the program enrolled a diverse and representative sample of the ACO population, including a high proportion of Hispanic/Latinx and Black patients. Approximately 1 in 5 Flex enrollees were children, highlighting that programs targeting individuals with HRSN and health needs benefit children as well as adults. Although Flex was designed to serve individuals, the qualitative findings suggest there were also benefits at the household level. More than 80% of enrolled patients received the intended food or housing support services. In comparison, a study of an intervention requiring patients with HRSN to contact a community resource helpline on their own (vs being referred through a health system pipeline) demonstrated only 36% received services.32 With obesity as the most prevalent qualifying health condition, Flex has the opportunity to influence critical risk factors in people with high cancer and cardiometabolic disease risk.33,34 In qualitative interviews, Flex enrollment was reported to be feasible, and those receiving nutrition services largely reported increased food security—a potential early signal of program effectiveness.

The study findings underscore the challenges of implementing systematic HRSN screening. In this well-resourced Medicaid ACO, only 57% of ACO enrollees completed a screening between 2018 and 2021. Even among Flex enrollees, screening rates were not 100%, indicating that HRSN were also assessed in informal ways (eg, conversations with clinicians or enrollment staff). While systematic screening efforts are required by an increasing number of state Medicaid agencies,35 challenges are well documented, including resource constraints36,37 and time burden for patients and staff.37,38

Two persistent challenges for Flex implementation—administrative burden and limited data-sharing infrastructure—yield important recommendations for future HRSN interventions, including the Flex program, which was extended through December 2027 as part of Massachusetts’ recent 1115 waiver renewal. To address the administrative burden of cross-sector initiatives, Medicaid agencies could offer administrative funding to health systems and community partners at the start of enrollment, as well as structured support for cross-sector partnerships, such as providing contract templates and best practice recommendations. Increased investment in technological assistance and infrastructure to support data sharing and outcomes reporting is critical. A recent national survey of state Medicaid agencies found that few states with active Medicaid HRSN screening or intervention protocols had systems to link data between Medicaid, health systems, and community partners.36 Data sharing between clinical and community partners and increased administrative burden were also substantial implementation challenges in the 2017-2022 Accountable Health Communities initiative to address social needs of Medicare recipients.39 As has been the case with health information exchange,40 coordination across competing platforms and incompatible systems present challenges that are compounded by the need for connections between the highly regulated health sector and the less-regulated social services sector. Investment in standardized data management technologies, designed with the needs of community and health system users in mind, could decrease these challenges and facilitate more rigorous evaluation of HRSN interventions.

Limitations

First, the evaluation focused on 1 ACO in a well-resourced urban health system. Results may not be representative of all Massachusetts’ ACOs, and findings should be considered alongside others’ Flex experiences. While a statewide evaluation of Massachusetts’s 1115 waiver programs is planned,41 the current study provides an early assessment of the associations between HRSN screening, Flex program enrollment, and patient experiences that can inform ongoing efforts to implement and sustain Flex and similar programs. Second, this study included perspectives of stakeholders inside the ACO (ie, staff, patients), but not outside entities (eg, MassHealth, SSOs). Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic and public health emergency measures during the study period influenced HRSN in myriad ways; while illness and reduced wages may have increased HRSN for some individuals, cash payments and evictions moratoriums may have reduced HRSN for others. Therefore, early Flex experiences may not be representative of program implementation when no public health emergency is in place.

Conclusions

The early implementation challenges of MassHealth’s Flexible Services program identified in this mixed-methods qualitative evaluation study, including program administration, cross-sector partnerships, and information sharing and data sharing, are similar to other Medicaid HRSN programs.21,36,42 For optimal reach, adoption, and implementation in diverse low-income populations, states, and health systems should provide funding to address administrative burdens, design effective data-sharing platforms, tailor support programs to patient preferences, and assess implementation outcomes during program delivery.

eMethods. The MassHealth Flexible Services Program

eTable. Health conditions documented by health center staff as eligibility criteria for enrollment into the Flexible Services program for patients aligned to 2 large hospitals in the Mass General Brigham Accountable Care Organization from March 2020 to July 2021.

eFigure. Semi-structured interview scripts for qualitative interviews with health system staff and Flexible Services program enrollees

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Berkowitz SA, Meigs JB, DeWalt D, et al. Material need insecurities, control of diabetes mellitus, and use of health care resources: results of the Measuring Economic Insecurity in Diabetes study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):257-265. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stahre M, VanEenwyk J, Siegel P, Njai R. Housing insecurity and the association with health outcomes and unhealthy behaviors, Washington state, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E109. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Njai RS, Greenlund KJ, Chapman DP, Croft JB. Relationships between housing and food insecurity, frequent mental distress, and insufficient sleep among adults in 12 US states, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E37. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morales ME, Berkowitz SA. The relationship between food insecurity, dietary patterns, and obesity. Curr Nutr Rep. 2016;5(1):54-60. doi: 10.1007/s13668-016-0153-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304-310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vercammen KA, Moran AJ, McClain AC, Thorndike AN, Fulay AP, Rimm EB. Food security and 10-year cardiovascular disease risk among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):689-697. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE. A systematic review of interventions on patients’ social and economic needs. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(5):719-729. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horwitz LI, Chang C, Arcilla HN, Knickman JR. Quantifying health systems’ investment in social determinants of health, by sector, 2017-19. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(2):192-198. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan AF, Chen Z, Wang Y, et al. Effectiveness of social needs screening and interventions in clinical settings on utilization, cost, and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):454-475. doi: 10.1089/heq.2022.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fichtenberg C, Delva J, Minyard K, Gottlieb LM. Health and human services integration: generating sustained health and equity improvements. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(4):567-573. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baicker K, McConnell M. Tying innovation to evaluation and accountability in programs to address intersecting health and social needs. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(10):e224323. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ash AS, Mick EO, Ellis RP, Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Clark MA. Social determinants of health in managed care payment formulas. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1424-1430. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottlieb L, Ackerman S, Wing H, Manchanda R. Understanding Medicaid managed care investments in members’ social determinants of health. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20(4):302-308. doi: 10.1089/pop.2016.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinton E, Stolyar L, Guth M, Nardone M. State delivery system and payment strategies aimed at improving outcomes and lowering costs in Medicaid. January 12, 2022. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-delivery-system-and-payment-strategies-aimed-at-improving-outcomes-and-lowering-costs-in-medicaid/

- 15.Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable Health Communities--Addressing Social Needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machledt D. Addressing the Social Determinants of Health Through Medicaid Managed Care. The Commonwealth Fund; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gershon R, Grenier M, Siefert RW. The MassHealth Waiver 2016–2022: delivering reform. January 5, 2017. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.bluecrossmafoundation.org/publication/masshealth-waiver-2016-2022-delivering-reform

- 18.Mass.gov . 1115 MassHealth Demonstration (“Waiver”). Accessed August 12, 2022. https://www.mass.gov/service-details/1115-masshealth-demonstration-waiver

- 19.Byhoff E, Freund KM, Garg A. Accelerating the implementation of social determinants of health interventions in internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):223-225. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4230-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Government Accountability Office (GAO) . Medicaid Demonstrations: Evaluations Yielded Limited Results, Underscoring Need for Changes to Federal Policies and Procedures. GAO; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (MACPAC) . Improving the Quality and Timeliness of Demonstration Evaluations. MACPAC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh A, Abazeed A, Chambers DA. Policy implementation science to advance population health: the potential for learning health policy systems. Front Public Health. 2021;9:681602. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.681602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mass.gov . MassHealth Accountable Care Organization Flexible Services. October 2019. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.mass.gov/doc/flexible-services-program-summary/download

- 24.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. 2019;7:64. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245-1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velasquez D, Figueroa JF. ACO and social service organization partnerships: payment, challenges, and perspectives. NEJM Catalyst. January 2022. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0319

- 27.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e26-e32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montgomery AE, Fargo JD, Kane V, Culhane DP. Development and validation of an instrument to assess imminent risk of homelessness among veterans. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(5):428-436. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71-77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyum S, Kreuter MW, McQueen A, Thompson T, Greer R. Getting help from 2-1-1: a statewide study of referral outcomes. J Soc Serv Res. 2016;42(3):402-411. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2015.1109576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625-1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, Echko M, et al. ; US Burden of Disease Collaborators . The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1444-1472. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Marchis EH, Brown E, Aceves B, et al. State of the science on social screening in healthcare settings. June 27, 2022. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.unitedforyouth.org/resources/state-of-the-science-on-social-screening-in-healthcare-settings

- 36.Chisolm DJ, Brook DL, Applegate MS, Kelleher KJ. Social determinants of health priorities of state Medicaid programs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3977-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kostelanetz S, Pettapiece-Phillips M, Weems J, et al. Health care professionals’ perspectives on universal screening of social determinants of health: a mixed-methods study. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25(3):367-374. doi: 10.1089/pop.2021.0176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browne J, Mccurley JL, Fung V, Levy DE, Clark CR, Thorndike AN. Addressing social determinants of health identified by systematic screening in a Medicaid accountable care organization: a qualitative study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:2150132721993651. doi: 10.1177/2150132721993651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Cross-sector data sharing to address health-related social needs: lessons learned from the Accountable Health Communities Model. 2022. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/cross-sector-data-sharing-to-address-health-related-social-needs-lessons-learned

- 40.Hochman M, Garber J, Robinson E. Health Information Exchange After 10 Years: Time For A More Assertive, National Approach. Health Affairs. August 14, 2019. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.healthaffairs.org/action/oidcStart?redirectUri=%2Fdo%2F10.1377%2Fforefront.20190807.475758

- 41.Goff SL, Gurewich D, Alcusky M, Kachoria AG, Nicholson J, Himmelstein J. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of value-based care models in new Medicaid accountable care organizations in Massachusetts: a study protocol. Front Public Health. 2021;9:645665. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.645665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray GF, Rodriguez HP, Lewis VA. Upstream with a small paddle: how ACOs are working against the current to meet patients’ social needs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(2):199-206. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. The MassHealth Flexible Services Program

eTable. Health conditions documented by health center staff as eligibility criteria for enrollment into the Flexible Services program for patients aligned to 2 large hospitals in the Mass General Brigham Accountable Care Organization from March 2020 to July 2021.

eFigure. Semi-structured interview scripts for qualitative interviews with health system staff and Flexible Services program enrollees

Data Sharing Statement