Abstract

Objectives:

Examine differences in perceptions of tap water (TW) and bottled water (BW) safety and TW taste and their associations with plain water (PW) and sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) intake.

Design:

Quantitative, cross-sectional study.

Setting:

United States.

Subjects:

4,041 U.S. adults (≥18 years) in the 2018 SummerStyles survey data.

Measures:

Outcomes were intake of TW, BW, PW (tap and bottled water), and SSB. Exposures were perceptions of TW and BW safety and TW taste (disagree, neutral, or agree). Covariates included sociodemographics.

Analysis:

We used chi-square analysis to examine sociodemographic differences in perceptions and multivariable logistic regressions to estimate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for consuming TW ≤ 1 cup/day, BW > 1 cup/day, PW ≤ 3 cups/day, and SSB ≥ 1 time/day by water perceptions.

Results:

One in 7 (15.1%) of adults did not think their home TW was safe to drink, 39.0% thought BW was safer than TW, and 25.9% did not think their local TW tasted good. Adults who did not think local TW was safe to drink had higher odds of drinking TW ≤ 1 cup/day (AOR = 3.12) and BW >1 cup/day (AOR = 2.69). Adults who thought BW was safer than TW had higher odds of drinking TW ≤1 cup/day (AOR = 2.38), BW > 1 cup/day (AOR = 5.80), and SSB ≥ 1 time/day (AOR = 1.39). Adults who did not think TW tasted good had higher odds of drinking TW ≤ 1 cup/day (AOR = 4.39) and BW > 1 cup/day (AOR = 2.91).

Conclusions:

Negative perceptions of TW safety and taste and a belief BW is safer than TW were common and associated with low TW intake. Perceiving BW is safer than TW increased the likelihood of daily SSB intake. These findings can guide programs and services to support water quality to improve perceptions of TW safety and taste, which might increase TW intake and decrease SSB intake.

Keywords: water perception, plain water, tap water, bottled water, sugar-sweetened beverages, characteristics, sociodemographic

Purpose

Drinking healthy beverages such as plain water in place of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) is one strategy to improve diet quality and prevent chronic diseases.1–3 SSB include beverages such as regular soda, fruit-flavored drinks (not 100% fruit juice), sports drinks, energy drinks, flavored water, sweetened coffee/tea beverages, and other beverages with added sugars.4 In the United States, SSB are the largest single source of added sugars in the diet of adults,4,5 and frequent intake of SSB is related to adverse health outcomes including obesity,6–8 type 2 diabetes,7,9,10 cardiovascular disease,11,12 dental caries,13,14 and asthma.15–17 Drinking plain water such as tap water, bottled water, and unflavored sparkling water without added sugars can improve diet quality and help avert chronic diseases1,3 when consumed in place of SSB.2 While the majority of the U.S. population receives drinking water from a public water system, systems which are among the safest in the world,18 broad inequity and water injustice issues limit access to clean water in the United States,19 and occasions of health violations in drinking water might occur locally.20 Organizations and individuals may prefer tap water for environmental reasons and affordability.21,22 According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), during 2011-2018, 46.3% of U.S. adults aged ≥20 years did not drink tap water, and 37.5% drank bottled water on a given day.23 Non-Hispanic (NH) Black and Hispanic adults had significantly higher prevalence of not drinking tap water but drinking bottled water than NH White adults.23 Additionally, another study reported that U.S. youth and young adults who did not drink water consumed more SSB than did water consumers.24

Negative perceptions of drinking water safety are common, and the lack of confidence in drinking water safety25,26 is important to consider when designing interventions to increase water intake and decrease SSB intake in populations. In 2010, 67.9% of U.S. adults agreed their local tap water was safe to drink, 36.2% did not think bottled water was safer than tap, and distrust of tap water safety was related to lower plain water intake and higher SSB intake among U.S. Hispanic adults.25 A study conducted in 2015 among U.S. Hispanic adults reported that 39.6% thought that their tap water at home was safe to drink, 11.9% did not think that bottled water was safer than tap water, and 68.8% agreed that they would buy less bottled water if they knew their local tap water was safe.26 Highly publicized water system failure like the Flint, Michigan, drinking water crisis (hereafter, “Flint water crisis”) in 201427 may reduce the public’s trust in their own local water supply. This may be borne out by NHANES data showing that the prevalence of not consuming tap water was 13% (prevalence ratio = 1.13) greater during 2017-2018 (post-Flint water crisis) than during 2013-2014 among U.S. adults, and that the prevalence of consuming bottled water was also greater during 2017-2018 than 2013-2014.23 Although a previous study examined the relationship between perceptions of tap and bottled water safety and plain water and SSB intake among U.S. adults using a 2010 HealthStyles Survey,25 it is not clear how perceptions of drinking water safety have changed following the surge of reporting on the Flint water crisis and with increasing drinking water quality violations in some U.S. areas.20 In this study, we examined the prevalence of perceptions of tap and bottled water safety and tap water taste and their associations with consuming tap water, bottled water, total plain water, and SSB among U.S. adults in the period following the Flint water crisis.

Methods

Design

This cross-sectional study uses data from the 2018 SummerStyles survey, an online panel survey sample of U.S. adults aged 18 years and older led by Porter Novelli Public Services.28 The survey collects data on a range of health-related attitudes, knowledge, behaviors, and conditions related to vital public health matters. The SummerStyles survey draws participants from KnowledgePanel®, a large-scale online panel that is representative of the non-institutionalized U.S. population. The KnowledgePanel® keeps approximately 55,000 panelists and is continually refilled. KnowledgePanel® members are randomly recruited by mail using probability-based sampling methods by address. If needed, a laptop or tablet and Internet access are offered to households. Informed written consent was obtained during the panel recruitment process. The current analysis was exempt from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) institutional review board approval because personal identifiers were not included in the data provided to the CDC.

Sample

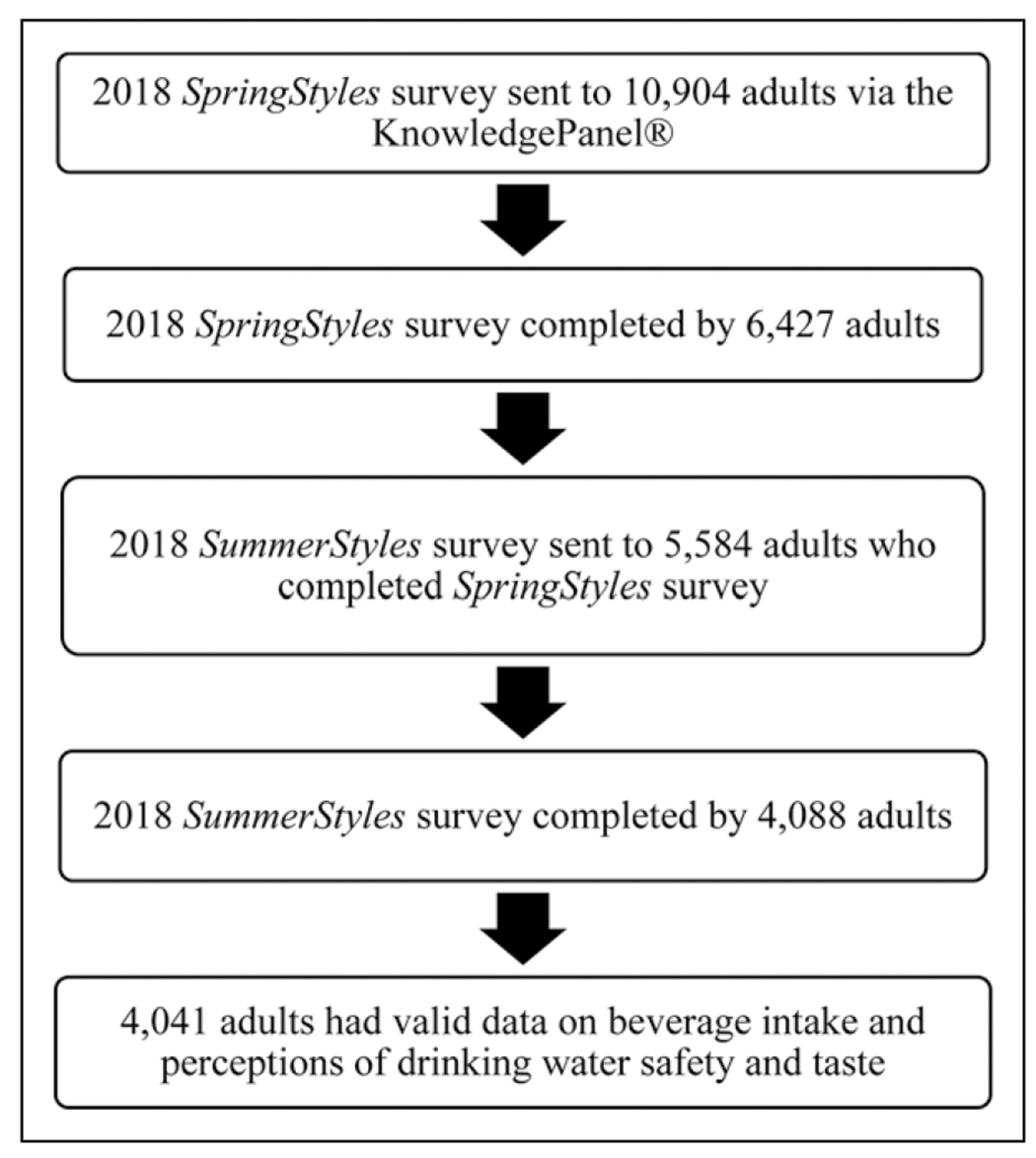

As shown in Figure 1, the SummerStyles survey was sent to 5,584 adults who had answered the SpringStyles survey during June-July 2018. The SpringStyles survey, an initial wave, was disseminated to a random sample of 10,904 panelists (aged ≥18 years), and 6427 adults finished the survey in March–April 2018 with a response rate of 58.9%. Overall, 4088 adults completed the SummerStyles survey with a response rate of 73.2%. Individuals who finished the survey got 5,000 cash-equivalent reward points, which are valued at approximately $5. The data were weighted to match Current Population Survey proportions using 8 factors: age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, household income, household size, census region, and metropolitan status. Of the 4,088 participants who completed the 2018 Summer-Styles survey, 47 adults (1.2%) were omitted from the present analysis due to missing data on outcome variables (ie, intake of tap water, bottled water, plain water, and SSB) or key exposure variables (ie, perceptions of tap water safety, bottled water safety, and tap water taste), leaving an analytic sample of 4,041 adults.

Figure 1.

Analytic sample flow chart among U.S. adults aged ≥18 years participating in the SummerStyles Survey, 2018.

Measures

The outcome variables were consumption of tap water (≤1 or >1 cup/day), bottled water (≤1 or >1 cup/day), total plain water (≤3 or >3 cups/day), and SSB (<1 or ≥1 time/day). Tap water intake (whether filtered or not) was determined by asking respondents, “On average, about how many cups of tap water do you drink each day? (8 oz. of water is equal to one cup.).” Bottled water intake was assessed by asking, “On average, about how many cups of bottled water do you drink each day? (8 oz. of water is equal to one cup. One standard 16 oz. bottle of water equals 2 cups.).” For each question, response selections were none, 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6-7 or ≥8 cups. To compute total plain water intake, we summed the responses from tap water intake and bottled water intake. To calculate daily water intake, we used the midpoint of a category when there was a range. Based on previous studies, to enable comparisons25,29 and distribution observed in the current study, we dichotomized tap water and bottled water intake into ≤1 or >1 cup/day and total plain water intake into ≤3 or >3 cups/day.

Frequency of SSB intake was determined by “During the past 7 days, how many times did you drink sodas, fruit drinks, sports or energy drinks, and other sugar-sweetened drinks? Do not include 100% fruit juice, diet drinks, or artificially sweetened low-calorie drinks.” Response options were none, 1-6 times/week, 1 time/day, 2 times/day, or ≥3 times/day. Based on previous studies,25,30 we dichotomized SSB intake into <1 or ≥1 time/day.

The key exposure variables were perceptions of tap water safety, bottled water safety, and tap water taste determined by the following 3 questions: (1) “My local tap water at home is safe to drink,” (2) “Bottled water is safer than tap water,” and (3) “My local water tastes good.” There were 5 response choices: Strongly disagree, Somewhat disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Some-what agree, and Strongly agree. For the analyses, we combined Strongly disagree and Somewhat disagree into Disagree and Strongly agree and Somewhat agree into Agree. Thus, we categorized water perceptions into 3 groups: Disagree, Neither (Neutral), and Agree.

We included sociodemographic characteristics, weight status, census region, and home ownership status as covariates. Sociodemographic characteristics were age (18-24, 25-44, 45-64, or ≥65 years), sex, race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Other/Multi-Race), education level (≤high school graduate, some college, college graduate), annual household income (<$35,000, $35,000–$74,999, $75,000–$99,999, or ≥$100,000), and marital status (married/domestic partnership or not married). We categorized widowed, divorced, separated, and never married as not married. Using self-reported weight and height data, we calculated body mass index (BMI), and we categorized weight status as underweight/healthy weight (BMI <25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2), or obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).31 Census region of residence was categorized into Northeast, Midwest, South, or West.32 Home ownership status was categorized as owned (ie, owned by respondent or someone in their household) or rented (rented for cash or occupied without payment of cash rent). The only variable with missing data was weight status (1.9% [n = 76)]). We omitted these observations when the weight status variable was used in any given test or model.

Analysis

In unadjusted analyses, we used χ2 tests to examine the bivariate associations of perceptions of tap and bottled water safety and tap water taste with sociodemographic characteristics as well as with intake of tap water, bottled water, total plain water, and SSB (significant at P < .05). We estimated separate multivariable logistic regression models for each outcome to calculate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the odds of low tap water intake (≤1 vs >1 cup/day), daily bottled water intake (>1 vs ≤1 cup/day), low total plain water intake (≤3 vs >3 cups/day), and daily SSB intake (≥1 vs <1 time/day). Perceptions of tap water safety, bottled water safety, and tap water taste were each analyzed in a separate model adjusted for other covariates. We tested for interactions between race/ethnicity and perceptions of tap and bottled water safety and tap water taste (Type 3 Analysis of Effects F-Test significant at P < .05) because previous studies reported racial/ethnic disparities in perceptions of tap and bottled water safety and how these perceptions are associated with consumption of SSB, especially among Hispanic populations.25,26 Of those 4041 adults with plain water intake, SSB intake, and water perception data, the logistic regression models included 3,965 adults with complete data on weight status. Data analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and used survey procedures to account for the sample design.

Results

Overall, 37% of respondents were 55 years old or over, 52% were women, and 64% were NH White adults. About 32% were college graduates, 34% had annual household income of $100,000 or more, and 62% were married or had domestic partnership. About 33% had obesity, 38% lived in the South, and 71% reported owning their house.

Water Perceptions by Sociodemographic Characteristics

Overall, in 2018, 15% of adults did not think that their home tap water was safe to drink; 39% thought that bottled water was safer than tap water; and 26% did not think that their local tap water tasted good (Table 1). Based on unadjusted analyses, perceptions of tap and bottled water safety and tap water taste differed significantly by age, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, census region, and home ownership (χ2 tests, P < .05). For instance, negative perceptions of tap water safety and taste and perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water were more prevalent among younger adults, adults of Hispanic or NH Black race/ethnicity, adults with lower education or income, adults who were not married, those living in the West, and renters (Table 1). Negative perceptions of tap water safety and taste were more prevalent among women, while perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water was more prevalent among adults with obesity (χ2 tests, P < .05). Negative perceptions of tap and bottled water safety and perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water were also related to each other (χ2 tests, P < .05). For example, 27% of adults who perceived bottled water is safer than tap water did not think that their local tap water was safe compared to 9% among adults who did not think bottled water was safer than tap water. About 40% of adults who perceived bottled water is safer than tap water did not think that their local tap water tasted good compared to 18% among those who did not think that bottled water was safer than tap water (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Tap Water and Bottled Water Safety Perceptions According to Characteristics of U.S. Adult Survey Respondents Aged ≥18 years Participating in the SummerStyles Survey, 2018.

| Tap Water Perception “My Local Tap Water at Home is Safe to Drink” |

Bottled Water Perception “Bottled Water is Safer than Tap water” |

Tap water Taste Perception “My Local Tap Water Tastes Good” |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All %a | Disagree %a | Neutral %a | Agree %a | P valueb | Disagree %a | Neutral %a | Agree %a | P valueb | Disagree %a | Neutral %a | Agree %a | P valueb |

| Total (N = 4041)c | 100 | 15.1 | 20.4 | 64.5 | 21.8 | 39.2 | 39.0 | 25.9 | 23.2 | 50.9 | |||

| Age (years) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| 18-34 | 29.6 | 17.4 | 25.3 | 57.3 | 17.7 | 37.9 | 44.4 | 29.5 | 29.0 | 41.6 | |||

| 35-54 | 33.5 | 17.4 | 20.5 | 62.1 | 22.4 | 38.1 | 39.5 | 27.6 | 22.1 | 50.3 | |||

| ≥55 | 36.9 | 11.3 | 16.3 | 72.4 | 24.5 | 41.2 | 34.3 | 21.4 | 19.6 | 59.0 | |||

| Sex | .03 | .96 | .0003 | ||||||||||

| Male | 48.2 | 13.3 | 20.3 | 66.4 | 21.6 | 39.2 | 39.3 | 22.4 | 24.6 | 53.0 | |||

| Female | 51.8 | 16.9 | 20.5 | 62.7 | 21.9 | 39.2 | 38.8 | 29.0 | 22.0 | 49.0 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| NH White | 64.2 | 12.5 | 16.9 | 70.6 | 25.1 | 40.2 | 34.7 | 23.6 | 18.9 | 57.5 | |||

| NH Black | 11.9 | 17.5 | 30.6 | 51.9 | 12.6 | 37.3 | 50.1 | 29.1 | 33.1 | 37.8 | |||

| Hispanic | 15.7 | 22.4 | 23.6 | 54.1 | 15.3 | 35.5 | 49.2 | 31.5 | 27.2 | 41.2 | |||

| NH Otherd | 8.2 | 18.4 | 26.8 | 54.8 | 21.1 | 41.2 | 37.7 | 28.3 | 34.9 | 36.8 | |||

| Education level | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| <High school | 11.1 | 20.7 | 34.1 | 45.2 | 13.7 | 42.4 | 43.9 | 30.9 | 28.4 | 40.7 | |||

| High school | 29.1 | 17.4 | 23.2 | 59.4 | 18.6 | 39.1 | 42.3 | 29.2 | 24.5 | 46.3 | |||

| Some college | 28.3 | 14.7 | 20.2 | 65.1 | 18.4 | 41.1 | 40.4 | 27.0 | 23.1 | 49.9 | |||

| College graduate | 31.5 | 11.5 | 13.2 | 75.3 | 30.5 | 36.4 | 33.1 | 20.0 | 20.3 | 59.7 | |||

| Annual household income | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| ≤$35,000 | 23.0 | 20.6 | 26.7 | 52.7 | 17.3 | 36.4 | 46.3 | 31.9 | 26.8 | 41.3 | |||

| $35,000–$74,999 | 29.0 | 15.0 | 24.6 | 60.4 | 19.8 | 39.5 | 40.7 | 29.2 | 24.0 | 46.8 | |||

| $75,000–$99,999 | 14.6 | 17.4 | 13.4 | 69.2 | 22.4 | 38.2 | 39.4 | 25.8 | 20.8 | 53.5 | |||

| ≥$100,000 | 33.5 | 10.5 | 15.5 | 74.0 | 26.2 | 41.3 | 32.5 | 18.8 | 21.1 | 60.0 | |||

| Marital status | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0001 | ||||||||||

| Married/domestic partnership | 62.1 | 14.2 | 17.5 | 68.3 | 24.5 | 38.5 | 36.9 | 25.0 | 21.1 | 54.0 | |||

| Not married | 37.9 | 16.7 | 25.1 | 58.2 | 17.2 | 40.3 | 42.5 | 27.3 | 26.7 | 45.9 | |||

| Weight statuse (n = 3965) | .09 | .04 | .14 | ||||||||||

| Underweight/healthy weight | 33.7 | 13.9 | 20.0 | 66.4 | 22.9 | 40.4 | 36.7 | 24.6 | 23.1 | 52.3 | |||

| Overweight | 32.9 | 13.6 | 20.0 | 66.4 | 23.2 | 39.4 | 37.4 | 24.0 | 23.0 | 53.0 | |||

| Obesity | 33.4 | 17.5 | 20.8 | 61.6 | 19.7 | 37.6 | 42.7 | 28.5 | 23.1 | 48.3 | |||

| Census regions of residence | .001 | .01 | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 17.9 | 13.9 | 22.8 | 63.3 | 21.7 | 39.0 | 39.2 | 21.6 | 25.7 | 52.7 | |||

| Midwest | 20.9 | 11.7 | 16.8 | 71.5 | 24.9 | 42.4 | 32.8 | 19.6 | 21.7 | 58.8 | |||

| South | 37.8 | 15.6 | 22.2 | 62.2 | 19.9 | 38.5 | 41.6 | 26.7 | 24.2 | 49.1 | |||

| West | 23.4 | 18.4 | 18.9 | 62.7 | 22.1 | 37.6 | 40.3 | 33.4 | 21.1 | 45.5 | |||

| Home ownership status | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| Rent | 29.5 | 21.5 | 26.9 | 51.6 | 16.6 | 37.0 | 46.4 | 33.9 | 28.5 | 37.5 | |||

| Owned | 70.5 | 12.5 | 17.6 | 69.9 | 23.9 | 40.1 | 35.9 | 22.5 | 21.0 | 56.5 | |||

| My local tap water at home is safe to drink | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||||||||||

| Disagree | — | — | — | 12.6 | 18.2 | 69.1 | 82.3 | 12.6 | 5.2 | ||||

| Neutral | — | — | — | 8.4 | 53.1 | 38.6 | 28.4 | 58.4 | 13.3 | ||||

| Agree | — | — | — | 28.1 | 39.7 | 32.1 | 11.8 | 14.6 | 73.6 | ||||

| Bottled water is safer than tap water | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||||||||||

| Disagree | 8.8 | 7.9 | 83.4 | — | — | — | 17.7 | 12.4 | 70.0 | ||||

| Neutral | 7.0 | 27.6 | 65.4 | — | — | — | 15.9 | 29.6 | 54.5 | ||||

| Agree | 26.8 | 20.1 | 53.1 | — | — | — | 40.4 | 22.9 | 36.7 | ||||

| My local tap water tastes good | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||||||||||

| Disagree | 48.2 | 22.4 | 29.5 | 14.9 | 24.1 | 61.0 | — | — | — | ||||

| Neutral | 8.2 | 51.3 | 40.6 | 11.6 | 49.9 | 38.5 | — | — | — | ||||

| Agree | 1.5 | 5.3 | 93.2 | 29.9 | 42.0 | 28.1 | — | — | — | ||||

Abbreviation: NH: non-Hispanic.

Weighted percentage may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

χ2 tests were used for each variable to examine differences across categories.

Unweighted sample size.

Includes other race and multi-races.

Weight status was based on calculated body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2): underweight/healthy weight, BMI <25; overweight, BMI 25-<30; obesity, BMI ≥30.

Association of Perception of Local Tap Water Safety With Intake of Plain Water and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage

Overall, 23% of adults reported drinking ≤1 cup/day of tap water, 52% drank >1 cup/day of bottled water, 22% drank a total of ≤3 cups/day of plain water, and 25% drank ≥1 time/day of SSB (Table 2). Negative perception of local tap water safety was associated with intake of tap water, bottled water, and SSB (χ2 tests, P < .05), but not with total plain water intake for adults overall and most racial/ethnic groups. About 38% of adults who did not think that their local tap water was safe to drink consumed ≤1 cup/day of tap water compared to 16% among those who thought the tap water was safe to drink. About 70% of adults who did not think that their local tap water was safe to drink consumed bottled water >1 cup/day compared to 43% among those who agreed. Approximately 28% of adults who did not think that their local tap water was safe to drink consumed SSB ≥1 time/day compared to 23% among those who agreed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of Tap Water Safety, Bottled Water Safety, and Tap Water Taste Perception With Daily Intake of Tap Water, Bottled Water, Total Plain Water, and Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Among U.S. Adults Aged ≥18 years Participating in the SummerStyles Survey, 2018.

| Beverage Intake, Weighted %a |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tap Water |

Bottled Water |

Total Plain Waterb |

SSBc |

|||||||||

| Perceptions | ≤1 cup/day | >1 cup/day | P valued | ≤1 cup/day | >1 cup/day | P valued | ≤3 cup/day | > cup/day | P valued | <1 Time/day | ≥1 Time/day | P valued |

| Total (N = 4041)e | 23.2 | 76.8 | 47.6 | 52.4 | 21.5 | 78.5 | 75.4 | 24.6 | ||||

| Local tap water perception “My local tap water at home is safe to drink” | ||||||||||||

| All Adults | <.0001 | <.0001 | .72 | .01 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 38.3 | 61.7 | 30.3 | 69.7 | 20.0 | 80.0 | 72.2 | 27.8 | ||||

| Neutral | 34.4 | 65.6 | 31.4 | 68.6 | 22.0 | 78.0 | 71.6 | 28.4 | ||||

| Agree | 16.0 | 84.0 | 56.8 | 43.2 | 21.7 | 78.3 | 77.3 | 22.7 | ||||

| NH White | <.0001 | <.0001 | .87 | .0003 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 42.1 | 57.9 | 34.2 | 65.8 | 23.3 | 76.7 | 74.2 | 25.8 | ||||

| Neutral | 34.8 | 65.2 | 37.3 | 62.7 | 25.0 | 75.0 | 68.8 | 31.2 | ||||

| Agree | 16.7 | 83.3 | 61.1 | 38.9 | 24.0 | 76.0 | 78.8 | 21.2 | ||||

| NH Black | <.0001 | .01 | .48 | .97 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 32.7 | 67.3 | 21.1 | 78.9 | 13.8 | 86.2 | 67.7 | 32.3 | ||||

| Neutral | 42.8 | 57.2 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 19.5 | 80.5 | 69.5 | 30.5 | ||||

| Agree | 16.5 | 83.5 | 33.6 | 66.4 | 14.0 | 86.0 | 68.4 | 31.6 | ||||

| Hispanic | <.0001 | .001 | .77 | .76 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 41.3 | 58.7 | 25.0 | 75.0 | 17.3 | 82.7 | 68.2 | 31.8 | ||||

| Neutral | 35.1 | 64.9 | 25.3 | 74.7 | 19.6 | 80.4 | 71.5 | 28.5 | ||||

| Agree | 15.0 | 85.0 | 46.2 | 53.8 | 15.9 | 84.1 | 73.4 | 26.6 | ||||

| NH Otherf | .32 | .0002 | .80 | .28 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 18.2 | 81.7 | 34.5 | 65.5 | 17.2 | 82.8 | 77.3 | 22.7 | ||||

| Neutral | 17.5 | 82.5 | 36.7 | 63.3 | 14.9 | 85.1 | 89.2 | 10.8 | ||||

| Agree | 10.7 | 89.3 | 64.6 | 35.4 | 19.1 | 80.9 | 82.2 | 17.8 | ||||

| Bottled water perception “bottled water is safer than tap water” | ||||||||||||

| All Adults | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 14.9 | 85.1 | 73.1 | 26.9 | 27.1 | 72.9 | 79.3 | 20.7 | ||||

| Neutral | 19.6 | 80.4 | 51.8 | 48.2 | 23.1 | 76.9 | 78.4 | 21.6 | ||||

| Agree | 31.3 | 68.7 | 29.1 | 70.9 | 16.6 | 83.4 | 70.3 | 29.7 | ||||

| NH White | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0004 | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 15.3 | 84.7 | 77.1 | 22.9 | 28.4 | 71.6 | 81.7 | 18.3 | ||||

| Neutral | 18.2 | 81.8 | 56.7 | 43.3 | 25.2 | 74.8 | 78.1 | 21.9 | ||||

| Agree | 34.0 | 66.0 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 19.7 | 80.3 | 71.0 | 29.0 | ||||

| NH Black | .73 | <.0001 | .004 | .60 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 22.1 | 77.9 | 50.1 | 49.9 | 24.2 | 75.8 | 66.6 | 33.4 | ||||

| Neutral | 27.6 | 72.4 | 30.2 | 69.8 | 22.2 | 77.8 | 72.1 | 27.9 | ||||

| Agree | 28.6 | 71.4 | 17.3 | 82.6 | 8.6 | 91.4 | 66.5 | 33.5 | ||||

| Hispanic | .03 | .0003 | .43 | .07 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 11.5 | 88.5 | 55.1 | 44.9 | 21.7 | 78.3 | 72.4 | 27.6 | ||||

| Neutral | 26.2 | 73.8 | 43.4 | 56.6 | 18.5 | 81.5 | 79.3 | 20.7 | ||||

| Agree | 29.6 | 70.4 | 25.8 | 74.2 | 14.6 | 85.4 | 66.1 | 33.9 | ||||

| NH Otherf | .05 | <.0001 | .33 | .37 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 8.9 | 91.9 | 81.2 | 18.8 | 25.1 | 74.9 | 77.1 | 22.9 | ||||

| Neutral | 9.7 | 90.3 | 56.3 | 43.7 | 16.3 | 83.7 | 86.7 | 13.3 | ||||

| Agree | 21.2 | 78.8 | 29.9 | 70.1 | 14.9 | 85.1 | 82.7 | 17.3 | ||||

| Tap water taste perception “My local water tastes good” | ||||||||||||

| All Adults | <.0001 | <.0001 | .57 | .001 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 38.4 | 61.6 | 31.7 | 68.3 | 21.1 | 78.9 | 72.1 | 27.9 | ||||

| Neutral | 30.0 | 70.0 | 38.6 | 61.4 | 22.9 | 77.1 | 72.6 | 27.4 | ||||

| Agree | 12.3 | 87.7 | 59.7 | 40.3 | 21.0 | 79.0 | 78.4 | 21.6 | ||||

| NH White | <.0001 | <.0001 | .36 | .001 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 40.1 | 59.9 | 36.9 | 63.1 | 25.2 | 74.8 | 73.5 | 26.5 | ||||

| Neutral | 32.4 | 67.6 | 43.9 | 56.1 | 26.1 | 73.9 | 71.8 | 28.2 | ||||

| Agree | 12.8 | 87.2 | 63.8 | 36.2 | 23.1 | 76.9 | 79.4 | 20.6 | ||||

| NH Black | <.0001 | .01 | .05 | .39 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 39.4 | 60.6 | 17.7 | 82.3 | 17.0 | 83.0 | 65.4 | 34.6 | ||||

| Neutral | 37.4 | 62.6 | 23.0 | 77.0 | 21.5 | 78.5 | 66.0 | 34.0 | ||||

| Agree | 9.4 | 90.6 | 35.7 | 64.2 | 9.5 | 90.5 | 73.4 | 26.6 | ||||

| Hispanic | <.0001 | .004 | .67 | .89 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 43.4 | 56.6 | 26.8 | 73.2 | 18.9 | 81.1 | 72.3 | 27.7 | ||||

| Neutral | 23.9 | 76.1 | 31.6 | 68.4 | 14.1 | 85.9 | 69.7 | 30.3 | ||||

| Agree | 13.2 | 86.8 | 47.3 | 52.7 | 17.6 | 82.4 | 72.7 | 27.3 | ||||

| NH Otherf | .15 | <.0001 | .002 | .01 | ||||||||

| Disagree | 14.8 | 85.2 | 28.9 | 71.1 | 4.8 | 95.2 | 71.9 | 28.1 | ||||

| Neutral | 18.9 | 81.1 | 48.2 | 51.8 | 24.7 | 75.3 | 89.4 | 10.6 | ||||

| Agree | 8.4 | 91.6 | 72.3 | 27.7 | 20.8 | 79.2 | 86.0 | 14.0 | ||||

Abbreviations: NH: non-Hispanic, SSB: sugar-sweetened beverages.

Weighted percentage may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Total plain water intake includes tap water and bottled water intake.

Included sodas, fruit drinks, sports or energy drinks, and other sugar-sweetened drinks (excluding 100% fruit juice, diet drinks, or artificially sweetened low-calorie drinks).

χ2 tests were used for each variable to examine differences across categories.

Unweighted sample size.

Includes other race and multi-races.

Based on multivariable logistic regression, adults who did not think or were neutral that their local tap water was safe to drink had significantly higher odds of drinking ≤1 cup/day (AOR range: 2.65-3.12) of tap water and >1 cup/day (AOR range: 2.53-2.69) of bottled water than those who agreed. After adjusting for covariates, tap water safety perception was not associated with intake of low total plain water and daily SSB (Table 3). There was no significant interaction observed between tap water safety and intake of tap water, bottled water, total water and SSB by race/ethnicity.

Table 3.

Associations of Perceptions of Tap Water Safety, Bottled Water Safety, and Tap Water Taste With Low Intake of Tap Water, and Total Plain Water and Daily Consumption of Bottled Water and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake Among U.S. Adults Aged ≥18 years (n = 3965) Participating in the SummerStyles Survey, 2018.

| Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceptions | Tap water ≤1 cup/day | Bottled water >1 cup/day | Total Plain waterb ≤3 cup/day | SSBc ≥1 Time/day |

| Local tap water perception “My local tap water at home is safe to drink”d | ||||

| All adults | ||||

| Disagree | 3.12 (2.44, 3.97) e | 2.69 (2.12, 3.42) e | .96 (.74, 1.27) | 1.12 (.86, 1.46) |

| Neutral | 2.65 (2.12, 3.31) e | 2.53 (2.04, 3.12) e | 1.08 (.86, 1.37) | 1.13 (.90, 1.43) |

| Agree | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Bottled water perception “bottled water is safer than tap water”d | ||||

| All adults | ||||

| Disagree | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Neutral | 1.33 (1.03, 1.72) e | 2.37 (1.93, 2.92) e | .81 (.66, 1.00) | .97 (.76, 1.22) |

| Agree | 2.38 (1.86, 3.05) e | 5.80 (4.67, 7.20) e | .55 (.44, .69) e | 1.39 (1.11, 1.75) e |

| Tap water taste perception “My local water tastes good”f | ||||

| All adults | ||||

| Disagree | 4.39 (3.54, 5.45) e | 2.91 (2.39, 3.53) e | 1.09 (.87, 1.36) | 1.23 (.99, 1.53) |

| Neutral | 3.18 (2.54, 3.99) e | 2.09 (1.72, 2.54) e | 1.28 (1.02, 1.59) | 1.20 (.96, 1.51) |

| Agree | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| P value for interaction by race/ethnicity | P = .12 | P = .54 | P = .001 | P = .25 |

| NH White | ||||

| Disagree | 1.13 (.89, 1.44) | |||

| Neutral | 1.23 (.95, 1.58) | |||

| Agree | Reference | |||

| NH Black | ||||

| Disagree | 1.92 (.82, 4.50) | |||

| Neutral | 2.80 (1.29, 6.05) e | |||

| Agree | Reference | |||

| Hispanic | ||||

| Disagree | 1.14 (.59, 2.23) | |||

| Neutral | .68 (.32, 1.45) | |||

| Agree | Reference | |||

| NH Otherg | ||||

| Disagree | .21 (.08, .55) e | |||

| Neutral | 1.43 (.63, 3.23) | |||

| Agree | Reference | |||

Abbreviations: NH: non-Hispanic, SSB: sugar-sweetened beverages.

For each perception variable, separate models were fitted for each outcome and controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, household income, marital status, weight status, census region, and home ownership status. Each outcome variable (ie, beverage intake) was dichotomized.

Total plain water intake includes tap water and bottled water intake.

Included sodas, fruit drinks, sports or energy drinks, and other sugar-sweetened drinks (excluding 100% fruit juice, diet drinks, or artificially sweetened low-calorie drinks).

No significant interaction by race/ethnicity (P ≥ .05).

Significant findings are bolded based on the 95% confidence intervals (ie, the confidence interval does not include 1).

Significant interaction by race/ethnicity at P < .05 between tap water taste perception and total water intake.

Includes other race and multi-races.

Association of Perception of Bottled Water Safety With Intake of Plain Water and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage

Perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water was associated with all other beverage intakes both overall and for some racial/ethnic groups (Table 2; χ2 tests, P < .05). About 31% of adults who perceived bottled water is safer than tap water consumed ≤1 cup/day of tap water compared to 15% of those who did not. About 71% of adults who perceived bottled water is safer than tap water consumed >1 cup/day of bottled water compared to 27% of those who did not. About 17% of adults who perceived bottled water is safer than tap water consumed ≤3 cups/day of total plain water compared to 27% of those who did not. About 30% of adults who perceived bottled water is safer than tap water consumed SSB ≥1 time/day compared to 21% of those who did not (Table 2).

Based on multivariable logistic regression, adults who agreed or had neutral perceptions that bottled water was safer than tap water had significantly higher odds of drinking ≤1 cup/day (AOR range: 1.33-2.38) of tap water and >1 cup/day (AOR range: 2.37-5.80) of bottled water. Adults who perceived bottled water is safer than tap water had significantly lower odds of drinking ≤3 cups/day (AOR = .55) of total plain water and had higher odds of drinking SSB ≥1 time/day (AOR = 1.39) (Table 3). No significant racial/ethnic interactions between bottled water safety and beverage intake were found.

Association of Perception of Local Tap Water Taste With Intake of Plain Water and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage

Negative perception of local tap water taste was associated with intake of tap water, bottled water, and SSB (χ2 tests, P < .05), but not with total plain water intake overall and not for some racial/ethnic groups. About 38% of adults who did not think that their local tap water tasted good consumed ≤1 cup/day of tap water compared to 12% among those who agreed. About 68% of adults who did not think their local tap water tasted good consumed >1 cup/day of bottled water compared to 40% of those who agreed. About 28% of adults who did not think that their local tap water tasted good consumed SSB ≥1 time/day compared to 22% of those who agreed (Table 2).

Participants who did not agree that their local water tasted good had significantly higher odds of drinking ≤1 cup/day (AOR range: 3.18-4.39) of tap water and >1 cup/day (AOR range: 2.09-2.91) of bottled water than those who agreed. We observed a significant interaction by race/ethnicity in the association of tap water taste with total water intake. The odds of drinking ≤3 cups/day of total plain water were significantly higher among NH Black adults who had neutral perception of tap water taste (AOR = 2.80) compared to NH Black adults who thought their local water tasted good. The odds of drinking ≤3 cups/day of total plain water were lower (AOR = .21) among adults of NH Other backgrounds who did not think that their tap water tasted good compared to those who thought their local water tasted good. Perception of tap water taste was not related to SSB intake after controlling for covariates (Table 3).

Discussion

In the current study, in 2018 (post-Flint water crisis), 1 in 7 adults (15%) did not think their tap water at home was safe to drink, 2 in 5 adults (39%) thought bottled water was safer than tap water, and 1 in 4 adults (26%) did not think their local tap water tasted good. We also found that negative perceptions of the safety and taste of tap water and preferences for bottled water were more prevalent among younger adults, NH Black and Hispanic adults, those with lower education or income, those who were not married, those residing in the West, and renters. A previous study examined associations between perceptions of tap and bottled water safety and their relationship with plain water and SSB intake among U.S. adults (N = 4184) in the 2010 HealthStyles Survey.25 While the percentage of U.S. adults who did not think their local tap water was safe to drink in 2018 (15%) was similar to the 2010 study (13%), the prevalence of perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water was much higher (ie, in 2018, 39% thought bottled water was safer than tap water compared to 26% in 2010).25 Somewhat similar to the current study, the 2010 study found mistrust of tap water safety and perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water were significantly more predominant among younger adults, NH Black adults, adults with lower income or education, and those who resided the West South Central region.25 In a separate study conducted among U.S. Hispanic adults (N = 1,000) in 2015, distrust of tap water safety was more widespread among Hispanic adults with lower education and household income, but perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water did not differ by sociodemographic characteristics.26 In the present study, the highest proportions of negative perceptions of tap water safety (ie, 22% disagreed) and taste (ie, 32% disagreed) were among Hispanic adults, whereas the highest proportion of perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water (ie, 50% agreed) was among NH Black adults. In the 2010 study, NH Black adults had the highest proportion of distrusting tap water (ie, 20% disagreed) and perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water (ie, 40% agreed).25 In the 2015 study, 34% of Hispanic adults did not think that their tap water at home was safe to drink, 65% agreed that bottled water was safer than tap water, and 69% agreed that they would buy less bottled water if they knew their local tap water was safe.26 The discrepancies in study findings could be due to differences in survey year (ie, 2010, 2015, and 2018) and study populations (eg, Hispanic adults only vs all adults)25,26 that might be influenced by country of origin, poor housing and living in communities with disproportionately unsafe drinking water, and/or in housing with older plumbing.

Unlike the 2010 study, we collected tap water intake and bottled water intake separately to understand how perceptions of tap water safety and preferences for bottled water would affect tap water intake, bottled water intake, and total plain water intake. Consistent with previous studies,25,33 we observed that adults who had negative perceptions of tap water safety had higher odds of consuming less tap water but more bottled water. Participants who thought bottled water is safer than tap water had higher odds of consuming less tap water but more bottled water and SSB. Participants who did not think that their tap water tasted good had significantly higher odds of low tap water intake and high bottled water intake, but their perception of tap water taste was not related to daily SSB intake.

In the 2010 study, Hispanic adults who did not think that their tap water was safe to drink had 2 times higher odds of drinking plain water ≤1 time/day or SSB ≥1 time/day compared with those who agreed or were neutral in the 2010 study.25 Tap water taste was not examined in that study. In the same study, perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water was significantly related to lower odds of daily SSB intake among NH Black adults (AOR = .6) and higher odds of daily SSB intake among NH Other adults (AOR = 2.0).25 These findings are important because to shift dietary patterns from SSB to drinking water actual and perceived water safety and quality will likely need to be considered. Upward trends in water quality issues20 and nationwide news coverage of drinking water contamination (eg, Flint water crisis)27 might influence upward trends in bottled water sales34 and distrust in public water systems.

In our study, 1 in 4 adults reported drinking tap water ≤1 cup/day, 1 in 2 consumed bottled water >1 cup/day, 1 in 5 consumed total plain water ≤3 cups/day, and 1 in 4 consumed SSB ≥1 time/day. According to NHANES 2011-2018 data, 46.3% of adults did not drink tap water, and 37.5% drank bottled water on a given day.23 In NHANES 2011-2018 data, the prevalence of not drinking tap water was significantly higher among NH Black adults, Hispanic and Other/Multi-Race adults, younger adults, those born outside the United States, and adults with lower income or education.23 During 2011-2018, the prevalence of drinking bottled water was significantly higher among non-White racial/ethnic groups, younger adults, adults born outside the United States, women, and adults with lower education, but the prevalence was lower among lower income adults compared with their counterparts.23 Additionally, other studies showed that non-Hispanic Black adults, adults with lower education or income, and adults who were not married drank less plain water35 and more SSB30,36–38 than their counterparts. As certain subgroups drink less tap water but more bottled water and SSB, tailored intervention efforts may be needed to improve perception of tap water safety and to diminish disparities in the consumption of plain water and SSB among U.S. adult populations. Plain water can be tap water and bottled water. Drinking plain water instead of SSB can reduce the risk of the adverse health consequences related to frequent SSB intake.1–3 Addressing distrust of tap water safety is important, because tap water can provide health benefits such as reductions in dental caries where community water is fluoridated.39 Drinking tap water instead of bottled water benefits environmental health and promotes sustainability. Drinking tap water instead of bottled water is more affordable, which is particularly important for the health of families with lower incomes.21,22,40

The strengths of the current study include the large sample size and the use of separate survey items for tap water intake and bottled water intake. This study has 4 limitations. First, the cross-sectional study design does not allow for determination of causality. Second, self-reported data might be subject to bias including recall or social desirability bias. Third, although the data were weighted to be similar to the Current Population Survey proportions, these findings from a sample of participants in the online panel might not be generalizable to the entire population of U.S. adults. Finally, SSB intake was measured in frequency, not volume of intake, so we cannot estimate the quantity of SSB consumed.

In conclusion, in 2018 about 1 in 7 adults did not think that their tap water at home was safe to drink, 2 in 5 adults thought bottled water was safer than tap water, and 1 in 4 adults did not think their local tap water tasted good. Negative perceptions of tap water safety and taste and perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water were more prevalent among younger adults, adults of Hispanic or NH Black race/ethnicity, adults with lower education or income, adults who were not married, those residing in the West, and renters. Negative perceptions of tap water safety and taste and perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water were associated with low tap water intake and higher daily bottled water intake. Additionally, perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water was related to higher daily SSB intake. These findings can guide programs and services to support water quality to improve perceptions of tap water safety and taste, which might increase tap water intake and decrease SSB intake.

SO WHAT?

What is already known on this topic?

Consumption of plain water instead of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) can improve diet quality and help avert chronic diseases. Limited information is available on perceptions of tap water and bottled water safety among U.S. adults after a surge of reporting on the Flint, Michigan, drinking water crisis.

What does this article add?

Overall, 1 in 7 (15.1%) of adults did not think their home tap water was safe to drink, 39.0% thought bottled water was safer than tap water, and 25.9% did not think their local tap water tasted good. Negative perceptions of tap water safety and taste and perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water were more prevalent among younger adults, adults of Hispanic or NH Black race/ethnicity, adults with lower education or income, adults who were not married, those residing in the West, and renters. Negative perceptions of tap water safety and taste and perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water were related to low tap water intake and daily bottled water intake. Additionally, perceiving bottled water is safer than tap water was related to higher daily SSB intake.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Our findings on negative perceptions of drinking water can guide programs and services to support water quality to improve perceptions of tap water safety and taste, which might increase tap water intake and decrease SSB intake.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

IRB Statement

The current analysis was exempt from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) institutional review board approval because personal identifiers were not included in the data provided to the CDC.

References

- 1.Popkin B, D’Anci K, Rosenberg I. Water, hydration, and health. Nutr Rev. 2010;68(8):439–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernández-Cordero S, Barquera S, Rodríguez-Ramírez S, et al. Substituting water for sugar-sweetened beverages reduces circulating triglycerides and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in obese but not in overweight Mexican women in a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr. 2014;144(11):1742–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An R, McCaffrey J. Plain water consumption in relation to energy intake and diet quality among US adults, 2005-2012. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29(5):624–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Agriculture U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition; 2020. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman SA, Clemens JC, Friday JE, LaComb RP, Paudel D, Shimizu M, Added sugars in adults’ diet: what we eat in America, NHANES 2015-2016. Food Surveys Research Group. Dietary Data Brief No 24; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):274–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik VS, Hu FB. Sweeteners and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: The role of sugar-sweetened beverages. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luger M, Lafontan M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Winzer E, Yumuk V, Farpour-Lambert N. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review from 2013 to 2015 and a comparison with previous studies. Obes Facts. 2017; 10(6):674–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33(11):2477–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Koning L, Malik VS, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverage consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(6): 1321–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Koning L, Malik VS, Kellogg MD, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sweetened beverage consumption, incident coronary heart disease, and biomarkers of risk in men. Circulation. 2012; 125(14):1735–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang C, Huang J, Tian Y, Yang X, Gu D. Sugar sweetened beverages consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Atherosclerosis. Feb 15. 2014;234(1):11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernabe E, Vehkalahti MM, Sheiham A, Aromaa A, Suominen AL. Sugar-sweetened beverages and dental caries in adults: A 4-year prospective study. J Dent. 2014;42(8):952–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valenzuela MJ, Waterhouse B, Aggarwal VR, Bloor K, Doran T. Effect of sugar-sweetened beverages on oral health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2020; 31(1):122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S, Akinbami LJ, McGuire LC, Blanck HM. Association of sugar-sweetened beverage intake frequency and asthma among U.S. adults, 2013. Prev Med. 2016;91:58–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie L, Atem F, Gelfand A, Delclos G, Messiah SE. Association between asthma and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in the United States pediatric population. J Asthma. 2021;10:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park S, Blanck HM, Sherry B, Jones SE, Pan L. Regular-soda intake independent of weight status is associated with asthma among US high school students. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1): 106–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. How does your water system work? https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-10/documents/epa-ogwdw-publicwatersystems-final508.pdf.

- 19.Mueller JT, Gasteyer S. The widespread and unjust drinking water and clean water crisis in the United States. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allaire M, Wu H, Lall U. National trends in drinking water quality violations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(9): 2078–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villanueva CM, Garfí M, Milá C, Olmos S, Ferrer I, Tonne C. Health and environmental impacts of drinking water choices in Barcelona, Spain: A modelling study. Sci Total Environ. 2021; 15795:148884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ballantine PW, Ozanne LK, Bayfield R. Why buy free? Exploring perceptions of bottled water consumption and its environmental consequences. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):757. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosinger AY, Patel AI, Weaks F. Examining recent trends in the racial disparity gap in tap water consumption: NHANES 2011-2018. Publ Health Nutr. 2021;25(2):207–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosinger AY, Bethancourt H, Francis LA. Association of caloric intake from sugar-sweetened beverages with water intake among US children and young adults in the 2011-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA Pediatr. 2019; 173(6):602–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onufrak SJ, Park S, Sharkey JR, Sherry B. The relationship of perceptions of tap water safety with intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and plain water among US adults. Publ Health Nutr. 2014;17(1):179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park S, Onufrak S, Patel A, Sharkey JR, Blanck HM. Perceptions of drinking water safety and their associations with plain water intake among US Hispanic adults. J Water Health. 2019;17(4):587–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanna-Attisha M, LaChance J, Sadler RC, Champney Schnepp A. Elevated blood lead levels in children associated with the Flint drinking water crisis: A spatial analysis of risk and public health response. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):283–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porter N. Consumer Styles & Youth Styles. Porter Novelli Styles. https://styles.porternovelli.com/consumer-youthstyles/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S, Onufrak S, Cradock A, et al. Correlates of infrequent plain water intake among US high school students: National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2017. Am J Health Promot. 2020; 34(5):549–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imoisili O, Park S, Lundeen EA, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage intake among adults, by residence in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties in 12 states and the District of Columbia, 2017. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Heart Lungs, Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. The Evidence Report. NIH Publication No. 98-4083. National Institutes of Health; 1998. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Census Bureau. Census regions and divisions of the United States. http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

- 33.Hu Z, Morton LW, Mahler RL. Bottled water: United States consumers and their perceptions of water quality. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(2):565–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodwan JG. Bottled Water 2020: Continued Upward Movement. U.S. and international developments and statistics; 2021. https://bottledwater.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2020BWstats_BMC_pub2021BWR.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosinger AY, Herrick KA, Wutich AY, Yoder JS, Ogden CL. Disparities in plain, tap and bottled water consumption among US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2014. Publ Health Nutr. 2018;21(8): 1455–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosinger AY, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among U.S. adults, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2017(270):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lundeen EA, Park S, Pan L, Blanck HM. Daily intake of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults in 9 states, by state and sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics. Prev Chron Dis. 2016;15:E154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park S, Lundeen EA, Pan L, Blanck HM. Impact of knowledge of health conditions on sugar-sweetened beverage intake varies among US adults. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(6): 1402–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Preventing dental caries: Community water fluoridation. 2013. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/dental-caries-cavities-community-water-fluoridation

- 40.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Emerging Technologies to Advance Research and Decisions on the Environmental Health Effects of Microplastics: Proceedings of a Workshop—In Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020. 10.17226/25862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]